Abstract

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is the most common hereditary subcortical vascular dementia. It is caused by mutations in NOTCH3 gene, which encodes a large transmembrane receptor Notch3. The key pathological finding is the accumulation of granular osmiophilic material (GOM), which contains extracellular domains of Notch3, on degenerating vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). GOM has been considered specifically diagnostic for CADASIL, but the reports on the sensitivity of detecting GOM in patients’ skin biopsy have been contradictory. To solve this contradiction, we performed a retrospective investigation of 131 Finnish, Swedish and French CADASIL patients, who had been adequately examined for both NOTCH3 mutation and presence of GOM. The patients were examined according to the diagnostic practice in each country. NOTCH3 mutations were assessed by restriction enzyme analysis of specific mutations or by sequence analysis. Presence of GOM was examined by electron microscopy (EM) in skin biopsies. Biopsies of 26 mutation-negative relatives from CADASIL families served as the controls. GOM was detected in all 131 mutation positive patients. Altogether our patients had 34 different pathogenic mutations which included three novel point mutations (p.Cys67Ser, p.Cys251Tyr and p.Tyr1069Cys) and a novel duplication (p.Glu434_Leu436dup). The detection of GOM by EM in skin biopsies was a highly reliable diagnostic method: in this cohort the congruence between NOTCH3 mutations and presence of GOM was 100%. However, due to the retrospective nature of this study, exact figure for sensitivity cannot be determined, but it would require a prospective study to exclude possible selection bias. The identification of a pathogenic NOTCH3 mutation is an indisputable evidence for CADASIL, but demonstration of GOM provides a cost-effective guide for estimating how far one should proceed with the extensive search for a new or an uncommon mutations among the presently known over 170 different NOTCH3 gene defects. The diagnostic skin biopsy should include the border zone between deep dermis and upper subcutis, where small arterial vessels of correct size are located. Detection of GOM requires technically adequate biopsies and distinction of true GOM from fallacious deposits. If GOM is not found in the first vessel or biopsy, other vessels or additional biopsies should be examined.

Keywords: CADASIL, GOM, skin biopsy, NOTCH3, genetic testing

Introduction

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), the most common hereditary vascular dementia, is characterized by migraineous headache with aura, recurrent ischaemic attacks, cognitive decline and psychiatric symptoms as the four main features. It is caused by mutations in NOTCH3 gene encoding a transmembrane receptor Notch3 (Joutel et al., 1996). Virtually all pathogenic mutations lead to an odd number of cysteine residues in one of the 34 epidermal growth factor (EGF) like repeats in the extracellular domain of Notch3 (N3ECD). The mutations result in a degeneration of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC), in which NOTCH3 is predominantly expressed in adult humans (Joutel et al., 2000a). The main pathological findings are accumulation of N3ECD on degenerating VSMCs as well as fibrosis and thickening of arterial walls, (Ruchoux et al., 1995; Miao et al., 2004). In electron microscopy (EM), the pathognomonic feature of CADASIL is accumulation of granular osmiophilic material (GOM) in indentations of the VSMCs or in the extracellular space in close vicinity to VSMCs (Baudrimont et al., 1993; Ruchoux et al., 1995). The exact composition of GOM has not been elaborated, but a recent immunogold EM study suggested N3ECD to be a component of GOM (Ishiko et al., 2006).

CADASIL is suspected in patients with the typical clinical features and white matter alterations in brain T2-weighted MRI (O'Sullivan et al., 2001). The definite verification of the diagnosis can be done by identifying a pathogenic mutation in the NOTCH3 gene. In CADASIL, at least 170 different mutations in 20 different exons have been reported (Supplementary Table 1). Comprehensive analysis of all these exons is time consuming and costly. Thus, most diagnostic laboratories screen only the exons that according to the previous reports harbour majority of the mutations (Joutel et al., 1997; Escary et al., 2000; Kalimo et al., 2002; Opherk et al., 2004; Dotti et al., 2005).

Already before the underlying gene defect was discovered, GOM was detected by EM in skin biopsies from CADASIL patients (Ruchoux et al., 1994). So far GOM has not been described in any other disease entity. However, the reports on the sensitivity of detecting GOM in skin biopsy of patients with genetically verified CADASIL have been contradictory. Two earlier studies on a smaller number of patients (Ebke et al., 1997; one family with eight patients, mutation not specified; Mayer et al., 1999; three families, 14 patients, mutations not specified) suggested 100% sensitivity and specificity, whereas two more recent papers have reported a low sensitivity: Markus et al. (2002) reported a sensitivity of only 44.4% (eight out of 18), while Razvi et al. (2003) suspected that the sensitivity might be even lower, although they did not give an exact number. To solve this contradiction, we performed a retrospective investigation of a combined patient material from Finland, Sweden and France comprising 131 patients, from whom both the genetic analysis and EM examination of skin biopsy were available. Skin biopsies from 26 mutation negative members of genetically proven CADASIL families served as control. We showed that electron microscopic demonstration of GOM in skin biopsy is a highly reliable and practical method to screen for or even specifically diagnose CADASIL. Furthermore, the intensive search for mutations based on confidence in the diagnostic specificity of GOM resulted in discovery of four novel, previously unreported mutations, among them the first duplication of three codons.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The subjects comprise of 131 patients in whom both the analysis of NOTCH3 gene and EM examination of skin biopsy had been adequately performed (38 from Finland, 13 from Sweden and 80 from France) as well as 26 control subjects (mutation negative members of the patients’ families: four from Finland, two from Sweden and 20 from France). Genetic analyses and biopsy examinations were, in general, performed without knowledge of the other test result. However, these analyses were part of the true clinical practice with the aim to establish the patient's diagnosis with all possible diagnostic methods, thus in several cases the detection of GOM in skin biopsy led to extended genetic analyses. Only a single subject, in whose biopsy no representative vessels of correct size were identified, was excluded from the study. Subjects have been clinically examined at different hospitals in Finland, Sweden or France as well as in different international hospitals from which blood and biopsy samples have been sent to France for diagnostic CADASIL analyses.

Molecular genetics

In Finland and Sweden, the diagnostic genetic analyses were originally limited to restriction enzyme analysis of two previously found mutations in Finland (p.Arg133Cys and p.Arg182Cys) and in negative cases complemented by sequence analysis of exons 3 and 4. Because the skin biopsy had shown presence of GOM in nine Finnish and Swedish suspected CADASIL patients without mutation being detected, an extended genetic analysis for NOTCH3 was established. For the detection of CADASIL type NOTCH3, mutation exons 2–24 of gene were amplified with specific primers and subsequently amplicons were sequenced using an automated sequencing system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Blood samples from hospitals in France and other countries were sent to Laboratoire de Cytogénétique, Hôpital Lariboisière, Paris, France and analysed as a commercial diagnostic service.

Electron microscopy

In Finland and Sweden, skin biopsies were requested from as many CADASIL suspected patients as possible, especially from those with a strong suspicion of CADASIL and negative result in limited genetic tests mentioned above. The skin biopsies were taken at the hospitals, where the CADASIL patients or their relatives were examined. Either full thickness punch biopsies or small incision biopsies were taken (usually from the upper arm) and fixed in phosphate buffered 3–4% glutaraldehyde, in which solution the biopsies were sent in Finland to the Laboratory of Electron Microscopy of the University of Turku or Helsinki, in Sweden to the Laboratory of Electron Microscopy at the Department of Pathology, University of Uppsala. In France the biopsies fixed in either Carson or Trump liquids or as above were sent to the Laboratories of Electron Microscopy at Hôpital Roger Salengro, University of Lille or Hôpital Bretonneau, University of Tours, France. The samples were postfixed in buffered osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in ascending grades of ethanol and embedded in Epon. Semithin sections were cut and stained with toluidine blue for selecting arteries of appropriate size (usually in the borderzone between dermis and subcutis) for thin sectioning. Thin sections were double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and then examined in transmission electron microscopes at the EM laboratories mentioned above. The Finnish and Swedish skin biopsies were analysed by two Finnish (S.T. and H.K.) electron microscopists and in France by a French (MMR) electron microscopist.

Results

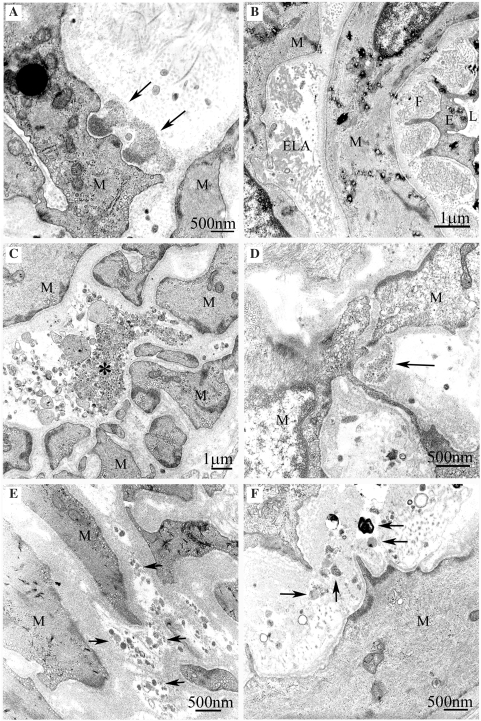

Altogether, GOM was detected in skin biopsies from all 131 patients, who in the genetic analyses were determined to carry a pathogenic NOTCH3 mutation for CADASIL (Table 1). GOM was present above all in arterial vessels, whereas the veins and capillaries were either GOM negative or seldom GOM positive (Figs 1 and 2). In most GOM positive cases, GOM was detected in the first biopsy but in a few cases a repeated biopsy was needed. During the diagnostic activity, we examined many suspected cases in whose biopsies we detected, instead of GOM, cellular debris between the VSMCs with structure that might lead unfamiliar electron microscopists astray. These cases were also negative in genetic tests (limited to the common mutations). Some common deposits of fallacious appearance are shown in Fig. 3.

Table 1.

The spectrum of NOTCH3 mutations in combined CADASIL patient cohort from Finland, Sweden and France

| Amino acid change | Nucleotide change in coding sequence | Exon | Finnish (F) French (Fr) Swedish (S) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | p.Cys49Tyr | c.146G>A | 2 | Fr |

| 2 | p.Cys67Sera | c.199T>A | 3 | S |

| 3 | p.Thr71Cys | c.213G>T | 3 | Fr |

| 4 | p.Arg90Cys | c.268C>T | 3 | Fr/S |

| 5 | p.Arg110Cys | c.328C>T | 3 | Fr |

| 6 | p.Arg133Cys | c.397C>T | 4 | F/Fr/S |

| 7 | p.Cys134Trp | c.402C>G | 4 | Fr |

| 8 | p.Arg141Cys | c.421C>T | 4 | Fr |

| 9 | p.Arg169Cys | c.505C>T | 4 | Fr |

| 10 | p.Gly171Cys | c.511G>T | 4 | Fr |

| 11 | p.Cys174Arg | c.520T>C | 4 | S |

| 12 | p.Arg182Cys | c.544C>T | 4 | Fr/S |

| 13 | p.Cys185Arg | c.553T>C | 4 | Fr |

| 14 | p.Cys185Gly | c.553T>G | 4 | Fr |

| 15 | p.Cys206Tyr | c.617G>A | 4 | S |

| 16 | p.Cys212Ser | c.634T>A | 4 | Fr |

| 17 | p.Cys222Gly | c.664T>G | 4 | Fr |

| 18 | p.Cys224Tyr | c.671G>A | 4 | Fr |

| 19 | p.Cys251Tyra | c.752G>A | 5 | S |

| 20 | p.Tyr258Cys | c.773A>G | 5 | Fr |

| 21 | p.Arg332Cys | c.994C>T | 6 | S |

| 22 | p.Cys428Ser | c.1283G>C | 8 | Fr |

| 23 | p.Glu434_Leu436dupa | c.1300_1308dup | 8 | F |

| 24 | p.Gly528Cys | c.1660G>T | 10 | F |

| 25 | p.Cys542Tyr | c.1625G>A | 11 | Fr |

| 26 | p.Arg558Cys | c.1672C>T | 11 | Fr/S |

| 27 | p.Arg578Cys | c.1732C>T | 11 | Fr |

| 28 | p.Arg728Cys | c.2182C>T | 14 | Fr |

| 29 | p.Arg985Cys | c.2953C>T | 18 | Fr |

| 30 | p.Arg1006Cys | c.3016C>T | 19 | Fr |

| 31 | p.Arg1031Cys | c.3091C>T | 19 | Fr |

| 32 | p.Tyr1069Cysa | c.3206A>G | 20 | F |

| 33 | p.Arg1231Cys | c.3691C>T | 22 | Fr |

| 34 | p.Cys1261Arg | c.3782T>C | 23 | Fr |

a Mutation previously unpublished.

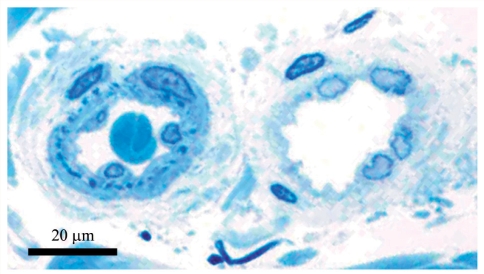

Figure 1.

A small arteriole (left) and venule (right) in the lower dermis of the skin biopsy from a Finnish CADASIL patient with p.Arg133Cys mutation. Note the somewhat thicker wall and lamina elastica interna (dark blue spots beneath the endothelium) in the arteriole. Toluidine blue-stained semithin epon section.

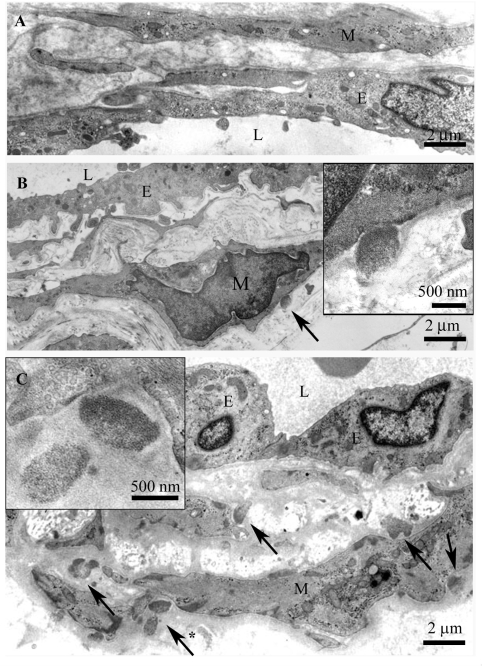

Figure 2.

(A) The same vein as in Fig. 1 with no GOM. (B) A vein from deep dermis with one definite GOM deposit (arrow) shown at a higher magnification in the inset. (C) The arteriole in Fig. 1 with several GOM deposits (five shown with arrows), one marked with asterisk is shown at a higher magnification in the inset. Note the characteristic pinocytotic vesicles at the VSMC plasma membrane beneath the GOM. L = lumen, E = endothelium, M = vascular smooth muscle cell.

Figure 3.

Fallacious deposits which may lead the electron microscopist astray. (A) True GOM with a somewhat exceptional mushroom-like form (arrows). Note the characteristic finely granular structure of GOM. (B) Fragments of elastica interna (ELA) and granular fibrillin network (F) in the widened subendothelial space. (C) Granular debris of unknown origin (asterisk). (D) Similar granular material as in C (arrow) with a misleading localization in a cove of VSMCs. (E and F) Small clumps of cell debris of different composition (arrows), possibly from degenerated cells. L = lumen, E = endothelium, M = vascular smooth muscle cell.

Representative skin biopsies were negative for GOM in the 26 subjects, who were also negative for the NOTCH3 mutation that was detected in their relatives. Therefore, these subjects were identified as definite negative cases for CADASIL.

In Finland and Sweden, GOM was detected in 51 patients, from 28 families with verified NOTCH3 mutations. In these families 12 different NOTCH3 mutations were identified, among these three point mutations (p.Cys67Ser, p.Cys251Tyr and p.Tyr1069Cys) and one duplication (p.Glu434_Leu436dup, producing an unpaired cysteine in the affected EGF repeat) were novel, previously unpublished (Table 1). In one Finnish patient, repeated skin biopsies were positive for GOM, although no mutation was found in screening of the NOTCH3 exons 2–24. Repeated genetic analysis with another set of primers revealed a heterozygous c.1582GT (p.Gly528Cys) mutation.

In France GOM was detected (by MMR) in all 80 NOTCH3 mutation positive patients—not only from France but also from different parts of the world. Among the patients whose DNA samples were analysed in France 26 different NOTCH3 mutations were identified (Table 1).

Discussion

In our patients’ detection of GOM from skin biopsy was a highly reliable method for the diagnostic workup of suspected CADASIL patients. GOM was detected in the skin biopsy of all 131 patients, in whom the NOTCH3 mutation had been identified and a representative skin biopsy was available. Thus the congruence was 100%. This study was performed retrospectively and therefore to exclude possible selection bias a prospective study would be required to get an exact figure for sensitivity, which we estimate to be well over 90%. The genetic analysis and EM detection of GOM were primarily made simultaneously and blinded to each other. Since the analysis has been made as a part of the diagnostic work, the EM analysis has been used to support the restricted genetic testing. In some cases, the GOM positive EM analysis prompted us to screen the NOTCH3 exons 2–24. During the examinations of suspected patients in some cases, no representative vessels were detected. A repeated biopsy was requested and if the biopsy was still non-representative the case was excluded from this study. Most often the parallel genetic analysis (limited as mentioned above) of these patients proved negative. Since our resources did not allow full sequencing of exons 2–24 in all suspected patients, CADASIL diagnosis could not be excluded in these patients with absolute certainty. In only one NOTCH3 mutation positive patient, we did not find representative vessels in the only available biopsy, and thus, the presence of GOM could not be determined. Based on the inclusion criteria this patient had to be excluded from this cohort.

When using EM analysis of skin biopsy as a diagnostic method in suspected CADASIL cases, special attention should be paid to the quality and analysis of the skin biopsy. The vessels in which the GOM is best detectable are generally medium sized or small arterioles (usually outer diameter 20–40 µm) in deep dermis or upper subcutis, but in a few cases GOM has been detected also in veins. In toluidine blue semi-thin sections the detection of lamina elastica interna as dark blue dots (Fig. 1) is a good marker of representative arterioles. Technical factors in the processing of the samples may also influence the result. Since GOM is osmiophilic, each laboratory should adjust the osmium tetroxide treatment such that GOM becomes sufficiently well contrasted. Furthermore, if GOM is not found in the first vessel investigated, other vessels or even repeat biopsies should be examined. Just like in any laboratory work, first negative result might be due to an unrepresentative sample or improper sample handling. Besides, one should examine rather an artery (with multiple layers of VSMCs and inner elastic lamina) than a vein or a capillary, since according to our experience veins and capillaries are not always GOM positive (Fig. 2). Of course, a prerequisite is that one recognizes GOM correctly and distinguishes it from fallacious deposits (Fig. 3).

Our confidence in the EM analysis prompted us to extend our search for mutations to sequencing the exons 2–24 in the nine patients in whom the limited mutation analyses had been negative. The detection of four novel mutations demonstrated that even though over 170 different NOTCH3 mutations are known, the presence of six cysteines in each of the translated 34 EGF repeats which may be replaced by another amino acid in addition to the replacement of other amino acids by cysteine, makes detection of hundreds of novel mutations still possible. This multitude is further widened by possibility of deletions (Dichgans et al., 2000, 2002; Opherk et al., 2004) and splice site mutations (Joutel et al., 2000b).

In one Finnish patient with GOM positive skin biopsy the NOTCH3 mutation was not detected until the analysis was performed with another set of primers (at Hôpital Lariboisière, the most experienced diagnostic CADASIL laboratory). This experience further emphasizes the value of skin biopsy examination as a guide for more comprehensive genetic analyses.

What would be the most efficient strategy to confirm the clinical suspicion of CADASIL? This strongly depends on the patient's family history and the mutational background in the population to which the suspected patient belongs. In families with a known mutation, the method of choice is, of course, to test directly for that mutation. If there are known founder or major mutations in the population, the diagnostic workup is best to begin by first searching for those mutations. In populations with no known founder or other determined mutations, screening of mutational hot spot region of the NOTCH3 gene should be the first genetic method to search for CADASIL. Of the all reported pathogenic NOTCH3 mutations 62% locate in exons 3, 4, 5 and 8. Furthermore, to obtain 80% coverage, additional investigation of exons 2, 6, 11 and 18 is required (Supplementary Table 1). At the latest after these analyses electron microscopy for GOM is highly recommended. Similar approach has been suggested by Peters et al. (2005). Mutation screening covering the whole region coding for EGF repeats (exons 2–24) is not realistic for all patients and for most laboratories.

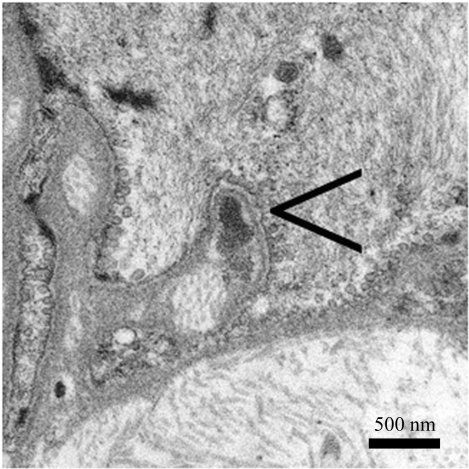

In cases with at least a fair amount of accumulated N3ECD the immunostaining has been found reliable (Joutel et al., 2001). However, if only a small amount of the N3ECD has accumulated, e.g. at the early stage of the disease, ultrastructural resolution and characteristic appearance of GOM most likely make the EM analysis more reliable: we have detected GOM even in patients below the age of 20 years (Fig. 4). Besides, non-specific staining is an inherent caveat of immunohistochemistry (Lesnik Oberstein et al., 2003), which may be problematic just in cases with small amounts of N3ECD. Moreover, EM examination provides also information about other pathological changes in the arterial wall, such as those due to hypertension, ageing and possibly even other hereditary arteriopathies (Ruchoux et al., 2000, 2002; Brulin et al., 2002). The absence of GOM in members of the Swedish family with multi-infarct dementia, previously thought to be the first published pedigree with CADASIL (Sourander and Walinder, 1977) was an important piece of evidence in addition to the negative genetic analyses in the demonstration that the family suffers from another hereditary vascular dementia (Low et al., 2007). On the other hand, the team of one of the authors (A.J.) has just identified another cerebral small vessels disease caused by a novel type of pathogenic mutation in the exon 25 of NOTCH3 outside the domain with EGF like repeats (Fouillade et al., 2008). This mutation, p.Leu1515Pro, causes increased canonical NOTCH3 signaling in a ligand-independent fashion, possibly due to destabilization of the Notch3 heterodimer. Remarkably, in this single patient reported there is no deposition of N3ECD and GOM on VSMCs.

Figure 4.

A small GOM deposit is in a deep indentation on a VSMC in a dermal arteriole from a 19-year-old CADASIL patient with p.Arg133Cys mutation. Note the pinocytotic vesicles.

In conclusion, the strategy of the CADASIL workup should be based on logical evaluation of clinical findings, family history as well as on both genetic and morphological methods available. Demonstration of a known pathogenic mutation provides indisputable evidence for the disease and gives a practical tool to clarify genetic counselling in the family. In those cases, in which the mutation is not easy to identify or genetic analysis is not available, skin biopsy is easy to perform and in experienced hands EM is a highly reliable method. Neither is it time consuming nor excessively expensive. Importantly, it is invaluable in guiding, how far one should proceed with the genetic analyses.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Funding

In Finland: from Academy of Finland, Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, EVO research funds of Helsinki and Turku University Hospitals and Turku City Hospital. In Sweden: from Swedish Research Council and ALF grants from Uppsala University Hospital and Huddinge University Hospital. In France: National Institutes of Health (R01 NS054122) and GIS-ANR Maladies Rares. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by University of Uppsala Grant, Department of Genetics and Pathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Department of Genetics and Pathology in University of Uppsala for their valuable contribution in the detection of the novel mutation p.Cys67Ser and the DNA diagnostic laboratory at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Genetics in University of Turku for the detection of the novel duplication mutation p.Glu434_Leu436dup. For their skilful ultrastructural techniques, we thank in Finland Virpi Myllys in Turku and Svetlana Zueva in Helsinki; in Sweden Madeleine Jarild in Uppsala; in France Sylvie Limol and Nathalie Goethink in Lille and Fabienne Arcanger in Tours. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by University of Uppsala Grant, Department of Genetics and Pathology.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CADASIL

cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EM

electron microscopy

- GOM

granular osmiophilic material

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cells

References

- Baudrimont M, Dubas F, Joutel A, Tournier-Lasserve E, Bousser MG. Autosomal dominant leukoencephalopathy and subcortical ischemic stroke. A clinicopathological study. Stroke. 1993;24:122–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brulin P, Godfraind C, Leteurtre E, Ruchoux MM. Morphometric analysis of ultrastructural vascular changes in CADASIL: analysis of 50 skin biopsy specimens and pathogenic implications. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2002;104:241–8. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0530-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichgans M. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy: phenotypic and mutational spectrum. J Neurol Sci. 2002;203–4:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichgans M, Ludwig H, Muller-Hocker J, Messerschmidt A, Gasser T. Small in-frame deletions and missense mutations in CADASIL: 3D models predict misfolding of Notch3 EGF-like repeat domains. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:280–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotti MT, Federico A, Mazzei R, Bianchi S, Scali O, Conforti FL, et al. The spectrum of Notch3 mutations in 28 Italian CADASIL families. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:736–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.048207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebke M, Dichgans M, Bergmann M, Voelter HU, Rieger P, Gasser T, et al. CADASIL: skin biopsy allows diagnosis in early stages. Acta Neurol Scand. 1997;95:351–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1997.tb00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escary JL, Cecillon M, Maciazek J, Lathrop M, Tournier-Lasserve E, Joutel A. Evaluation of DHPLC analysis in mutational scanning of Notch3, a gene with a high G-C content. Hum Mutat. 2000;16:518–26. doi: 10.1002/1098-1004(200012)16:6<518::AID-HUMU9>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouillade C, Chabriat H, Riant F, Mine M, Arnoud M, Magy L, et al. Activating NOTCH3 mutation in a patient with small-vessel-disease of the brain. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:452. doi: 10.1002/humu.9527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiko A, Shimizu A, Nagata E, Takahashi K, Tabira T, Suzuki N. Notch3 ectodomain is a major component of granular osmiophilic material (GOM) in CADASIL. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2006;112:333–9. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutel A, Andreux F, Gaulis S, Domenga V, Cecillon M, Battail N, et al. The ectodomain of the Notch3 receptor accumulates within the cerebrovasculature of CADASIL patients. J Clin Invest. 2000a;105:597–605. doi: 10.1172/JCI8047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutel A, Chabriat H, Vahedi K, Domenga V, Vayssiere C, Ruchoux MM, et al. Splice site mutation causing a seven amino acid Notch3 in-frame deletion in CADASIL. Neurology. 2000b;54:1874–5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.9.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutel A, Corpechot C, Ducros A, Vahedi K, Chabriat H, Mouton P, et al. Notch3 mutations in CADASIL, a hereditary adult-onset condition causing stroke and dementia. Nature. 1996;383:707–10. doi: 10.1038/383707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutel A, Favrole P, Labauge P, Chabriat H, Lescoat C, Andreux F, et al. Skin biopsy immunostaining with a Notch3 monoclonal antibody for CADASIL diagnosis. Lancet. 2001;358:2049–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutel A, Vahedi K, Corpechot C, Troesch A, Chabriat H, Vayssiere C, et al. Strong clustering and stereotyped nature of Notch3 mutations in CADASIL patients. Lancet. 1997;350:1511–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalimo H, Ruchoux MM, Viitanen M, Kalaria RN. CADASIL: a common form of hereditary arteriopathy causing brain infarcts and dementia. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:371–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesnik Oberstein SA, van Duinen SG, van den Boom R, Maat-Schieman ML, van Buchem MA, van Houwelingen HC, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic NOTCH3 immunostaining in CADASIL. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2003;106:107–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0701-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low WC, Junna M, Borjesson-Hanson A, Morris CM, Moss TH, Stevens DL, et al. Hereditary multi-infarct dementia of the Swedish type is a novel disorder different from NOTCH3 causing CADASIL. Brain. 2007;130:357–67. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HS, Martin RJ, Simpson MA, Dong YB, Ali N, Crosby AH, et al. Diagnostic strategies in CADASIL. Neurology. 2002;59:1134–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.8.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M, Straube A, Bruening R, Uttner I, Pongratz D, Gasser T, et al. Muscle and skin biopsies are a sensitive diagnostic tool in the diagnosis of CADASIL. J Neurol. 1999;246:526–32. doi: 10.1007/s004150050398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Q, Paloneva T, Tuominen S, Poyhonen M, Tuisku S, Viitanen M, et al. Fibrosis and stenosis of the long penetrating cerebral arteries: the cause of the white matter pathology in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Brain Pathol. 2004;14:358–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan M, Jarosz JM, Martin RJ, Deasy N, Powell JF, Markus HS. MRI hyperintensities of the temporal lobe and external capsule in patients with CADASIL. Neurology. 2001;56:628–34. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.5.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opherk C, Peters N, Herzog J, Luedtke R, Dichgans M. Long-term prognosis and causes of death in CADASIL: a retrospective study in 411 patients. Brain. 2004;127:2533–9. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters N, Opherk C, Bergmann T, Castro M, Herzog J, Dichgans M. Spectrum of mutations in biopsy-proven CADASIL: implications for diagnostic strategies. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1091–4. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.7.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razvi SS, Davidson R, Bone I, Muir KW. Diagnostic strategies in CADASIL. Neurology. 2003;60:2019–20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.12.2019. author reply 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchoux MM, Brulin P, Brillault J, Dehouck MP, Cecchelli R, Bataillard M. Lessons from CADASIL. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;977:224–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchoux MM, Brulin P, Leteurtre E, Maurage CA. Skin biopsy value and leukoaraiosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;903:285–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchoux MM, Chabriat H, Bousser MG, Baudrimont M, Tournier-Lasserve E. Presence of ultrastructural arterial lesions in muscle and skin vessels of patients with CADASIL. Stroke. 1994;25:2291–2. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.11.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchoux MM, Guerouaou D, Vandenhaute B, Pruvo JP, Vermersch P, Leys D. Systemic vascular smooth muscle cell impairment in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1995;89:500–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00571504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourander P, Walinder J. Hereditary multi-infarct dementia. Morphological and clinical studies of a new disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1977;39:247–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00691704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.