ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To ascertain the short-term intentions of Canadian clinically active family physicians (CAFPs) to change their practice locations.

DESIGN

Secondary analysis of the 2004 National Physician Survey (NPS) data.

SETTING

Canada.

PARTICIPANTS

All Canadian CAFPs who responded to the 2004 NPS survey.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Physicians’ self-reported intentions to move their practice locations to other provinces or other countries. Variables included age, sex, marital status, having children, professional satisfaction, practice region (British Columbia, Alberta, the Prairies [Saskatchewan and Manitoba], Ontario, Quebec, or the Atlantic Provinces) and work setting (urban, small town, rural, etc). Logistic and regression tree analyses were used to find predictors of intention to move out of province.

RESULTS

The 2004 NPS was completed by 21 296 physicians, 11 041 of whom were family physicians. Of these, 8537 satisfied our study inclusion criteria. A total of 3.6% of those CAFPs planned to relocate their practices to other provinces and 3.0% planned to relocate to other countries within the next 2 years (from the time of the survey). Practising in the Prairies and, to a lesser extent, in the Atlantic Provinces were the most powerful predictors of planned interprovincial migration. Dissatisfaction with professional life was the most powerful predictor of planning migration abroad as well as being a predictor of planned interprovincial migration. Other common and statistically significant predictors of interprovincial migration and migration abroad were age, sex, and marital status.

CONCLUSION

Patients in the Prairie and Atlantic regions are at greater risk of having their family physicians migrate to other provinces than those in British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec are. As interprovincial migration profiles differ according to region of practice, they could be used by provincial health human resource planners to understand and predict the movement of health care workers out of their respective provinces.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Déterminer les intentions des médecins de famille canadiens en pratique active (MFPA) de changer à court terme leur lieu de pratique.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Seconde analyse des données du Sondage national des médecins (SNM) 2004.

CONTEXTE

Canada.

PARTICIPANTS

Tous les MFPA canadiens qui ont répondu au SNM 2004.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES À L’ÉTUDE

Déclarations des médecins sur leurs intentions d’aller pratiquer dans d’autres provinces ou pays. Les variables comprenaient l’âge, le sexe, l’état civil, le fait d’avoir des enfants, la satisfaction professionnelle, la région de pratique (Colombie-Britannique, Alberta, Prairies [Saskatchewan et Manitoba], Ontario, Québec ou Maritimes) et le contexte de travail (urbain, petite municipalité, rural, etc.). On a utilisé des analyses de régression logistique par arbre de décision pour cerner les indicateurs d’intention de quitter la province.

RÉSULTATS

Un total de 21 296 médecins ont répondu au SNM 2004, dont 11 041 médecins de famille. Parmi ces derniers, 8537 répondaient à nos critères d’inclusion. Au total, 3,6 % des MFPA envisageaient d’aller pratiquer dans une autre province et 3,0 % dans un autre pays, au cours des 2 ans suivant l’enquête. Les indicateurs les plus convaincants de l’intention de changer de province étaient le fait de pratiquer dans les Prairies et, à un moindre degré, dans les Maritimes. L’insatisfaction sur le plan professionnel était le plus fort indicateur de la volonté de déménager à l’étranger. Les autres indicateurs fréquents et statistiquement significatifs du désir de déménager dans une autre province ou un autre pays incluaient l’âge, le sexe et l’état civil.

CONCLUSION

Les patients des Prairies et des Maritimes sont plus susceptibles que ceux de la Colombie-Britannique, de l’Ontario et du Québec de voir leur médecin de famille migrer dans une autre province. Le profil des migrations inter-provinciales varie selon les régions de pratique, et les planificateurs des ressources humaines en santé devraient en tenir compte pour comprendre et prédire les migrations des travailleurs de la santé hors de leurs provinces respectives.

Accessibility of health care is one of the 5 principles of the Canada Health Act.1 The past decade has seen considerable changes in the number of physicians practising in Canada, the geographic variation of their practices, and the manner in which they deliver care. Many factors have compounded these issues, such as demographic changes in the population and the medical profession, considerable restructuring of the health care system, and reform in the delivery of primary care.2

Although the physician-to-population ratio at the national level has stabilized, an unequal distribution of physicians per capita still exists across the provinces.3 Even during the time of perceived physician oversupply at the national level, several provinces suffered acute shortages.2,4 Benarroch and Grant attribute this unbalanced distribution of physicians to 2 unique features of the Canadian health care system: 1) despite Canada’s publicly funded universal health insurance plan, the country continues to rely upon private provision of physician care on a fee-for-service basis; 2) although the federal government dictates minimum levels of service and contributes to funding via federal-provincial revenue transfers, the delivery of health care services is a provincial responsibility.3 Accordingly, migration of physicians among provinces is not only more substantial numerically, compared with international migration, but also poses a difficulty when regulating the level and cost of health care services at the provincial level.3

Basu and Rajbhandary published a study using micro-data collected from all active physicians in the Canadian provinces between 1974 and 2002 in order to identify key factors contributing to interprovincial migration.4 The study compared the migration patterns of general practitioners with those of other specialists and analyzed the changing patterns of migration over time. It also analyzed the effect of language as a determinant of migration for predominantly French-speaking physicians outside the province of Quebec.

Benarroch and Grant specifically studied the interprovincial migration of general practitioners and specialists between 1976 and 1992 using aggregate data. These authors found that, to some extent, the Atlantic Provinces, the Prairies, and Quebec served as training grounds for physicians who later established their practices in Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia.3 As well, interprovincial migration of physicians is also strongly proportionate to the number of foreign-trained physicians. Baerlocher also examined the hypothesis that Canada’s continued reliance on foreign-trained physicians is related to interprovincial migration; he found that between 1987 and 2003 the provinces that suffered the greatest “loss” of physicians on account of interprovincial migration relied most heavily on foreign-trained physicians.5 In a similar study, Dauphinee found that between 1999 and 2003, 3 of Canada’s largest and richest provinces—Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia—benefitted the most from physician migration from the rest of Canada.6 Interestingly, the 3 provinces with net physician losses—Newfoundland, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan—also disproportionately recruited physicians from outside Canada, presumably to offset the internal losses of their own graduates to other Canadian provinces. In this context, understanding the migration of physicians across provinces and the under-lying factors contributing to these moves would help policy makers at the provincial level, as well as at the national level, improve the distribution of physicians across provinces and Territories.3,4 To our knowledge, there are no studies published on the short-term intentions of primary care physicians to change their practice locations or the reasons why they plan to migrate.

The main objective of this study was to describe the changes in practice locations planned by clinically active family physicians (CAFPs) within the 2 years following the study (2004 to 2006). Other objectives included finding individual, professional, and contextual factors associated with planning a change of practice location, as well as profiling different subpopulations of family physicians according to the likelihood of planned migration over the 2-year period.

METHODS

Study design and data source

Data from a cross-sectional survey—the 2004 National Physician survey (NPS)—was used to complete this descriptive study. The NPS is a self-reported survey, which was sent using a combination of paper and electronic questionnaires to all 62 000 licensed physicians practising in Canada (both family physicians and other specialists) in 2004. The NPS mailing and e-mail lists were generated from the Canadian Medical Association Masterfile, a database of all physicians in Canada holding medical licences. The questionnaires were distributed using a modified Dillman approach and were completed between February and June 2004. Additional methodologic details about the NPS have been described in detail elsewhere.7 The response rate for family physicians was 36% (n = 11 041).

Population studied

The cohort included all CAFPs practising in Canada who responded to the 2004 NPS. We excluded those whose main practice settings were administrative offices, research units, diagnostic clinics, or other non–clinical care settings. Also excluded were those physicians practising in the Yukon, Nunavut, or the Northwest Territories owing to insufficient numbers for performing regression analyses. Those with data missing for the main or secondary variables were also removed from the population studied.

Variables studied

The main variables of interest for this study were planned interprovincial migration and planned migration abroad by CAFPs within the following 2 years. Other variables included age, sex, marital status, having children or dependents, province of work (British Columbia, Alberta, the Prairies [Saskatchewan and Manitoba], Ontario, Quebec, or the Atlantic Provinces), professional dissatisfaction (with respect to professional life, relationship with hospital, relationships with colleagues, ability to find locum tenens coverage, etc), and work setting (inner city, urban, or suburban; small town; rural, isolated, or remote; and mixed or other).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses as well as logistic and regression tree analyses were used. A significance level of 0.05 was set. The RTree program was used for the regression tree analyses8–11 and SAS version 9.1.3 was used for all other statistical analyses.

RESULTS

The 2004 NPS was completed by 21 296 physicians, 11 041 of whom were family physicians. Of these, 9253 (83.8%) satisfied the inclusion criteria. A total of 680 CAFPs (7.3%) were removed from the analyses because of data missing from covariables, namely age, sex, marital status, children or dependents, work setting, and province of practice. After exclusion of physicians practising in Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, and the Yukon (n = 36), 8537 CAFPs were retained. The average age of CAFPs was 47.4 years (SD 10.4), 61.4% were men, and 86.8% were married or living with partners.

A total of 6203 (72.7%) CAFPs who responded planned to make at least one change in their practices within the next 2 years (Table 1). When looking specifically at whether or not CAFPs planned to change practice locations, we observed that 1123 (13.2%) planned to relocate. Among them, 253 (3.0% of all participants) planned to move their practices to other countries, and 305 (3.6%) planned to relocate to other provinces or Territories within Canada. Other planned changes included reducing weekly work hours (reported by one-quarter of CAFPs), reducing scope of practice, and reducing on-call hours (reported by almost 15% of CAFPs).

Table 1.

Self-reported practice changes planned by CAFPs between 2004 and 2006: N = 8537.

| DESCRIPTION* | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Changes in practice location | |

| • Relocate practice within the same province or Territory | 629 (7.4) |

| • Relocate practice to another province or Territory in Canada | 305 (3.6) |

| • Leave Canada to practise in another country | 253 (3.0) |

| • Move from a rural or remote practice setting to an urban or suburban setting | 241 (2.8) |

| • Move from an urban or suburban practice setting to a rural or remote setting | 91 (1.1) |

| Reducing clinical workload or practice | |

| • Reduce weekly work hours (excluding on-call hours) | 2221 (26.0) |

| • Reduce on-call hours | 1262 (14.8) |

| • Reduce scope of practice | 1199 (14.0) |

| • Increase teaching, research, or administrative responsibilities | 1017 (11.9) |

| • Take a temporary leave of absence | 681 (8.0) |

| • Retire | 393 (4.6) |

| • Specialize in an area of medical practice | 351 (4.1) |

| • Leave active practice | 111 (1.3) |

| Increasing clinical workload or practice | |

| • Expand scope of practice | 431 (5.0) |

| • Reduce teaching, research, or administrative responsibilities | 404 (4.7) |

| • Increase weekly work hours (excluding on-call) | 374 (4.4) |

| • Increase on-call hours | 216 (2.5) |

| Other changes | |

| • Change mode of remuneration | 643 (7.5) |

| • Become part of a practice network | 634 (7.4) |

| • Change to a multidisciplinary practice model | 277 (3.2) |

| • Change from solo to group practice | 249 (2.9) |

| • Retrain within the medical field | 201 (2.4) |

| • Relocate to Canada from another country | 23 (0.3) |

| • Other changes | 200 (2.4) |

CAFPs—clinically active family physicians.

Categories are not exclusive.

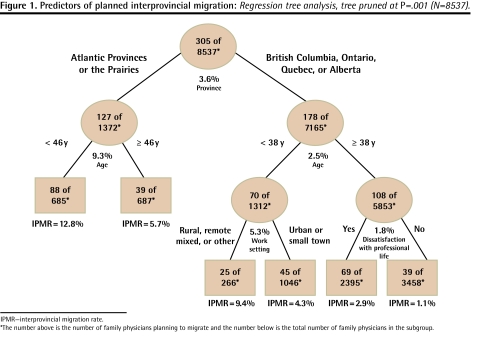

We discovered that CAFPs planning external migration (interprovincial migration or migration abroad) tended to be younger, and a higher proportion were male and single (Table 2). The following variables were positively and significantly associated with the probability of planned interprovincial migration in the next 2 years: younger age (P < .0001); male sex (P < .0001); being single, divorced, separated, or widowed (P = .0003); dissatisfaction regarding professional life (P < .0001); dissatisfaction regarding relationships with colleagues (P = .0158) and relationships with hospitals (P = .0367); rural, isolated, remote (P < .0001), or small-town clientele (P = .0075); and practising in the Prairies (P < .0001), the Atlantic Provinces (P < .0001), and (to a lesser extent) Ontario (P < .0049) and Alberta (P < .0282) compared with British Columbia (Table 3). The regression tree analysis (Figure 1) further identified which CAFPs were more inclined to plan interprovincial migration in the next 2 years: we found that 12.8% of CAFPs who were living in the Atlantic Provinces or the Prairies and who were younger than 46 years of age planned to migrate versus 5.7% of those older than 46 years; 9.4% of those 38 years of age and younger practising in British Columbia, Quebec, Ontario, or Alberta planned to migrate if they practised in a rural or mixed area compared with older physicians who do not express dissatisfaction in their professional lives (1.1%). Intermediate risk profiles are detailed in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Comparison of respondent CAFPs who planned to relocate their practices out-of-province* and those who did not, by secondary variables studied: N = 8537.

| COVARIABLE | CAFPs NOT PLANNING OUT-OF-PROVINCE MIGRATION | CAFPs PLANNING OUT-OF-PROVINCE MIGRATION* |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y (SD)† | 47.7 (10.4) | 42.9 (9.1) |

| Sex, n (%)† | ||

| • Men | 4891 (60.9) | 3145 (39.1) |

| • Women | 353 (70.5) | 148 (29.5) |

| Marital status, n (%)† | ||

| • Married or living with partner | 7007 (87.2) | 1029 (12.8) |

| • Single, separated, divorced, or widowed | 401 (80.0) | 100 (20.0) |

| Children or dependents, n (%)‡ | ||

| • Yes | 5297 (65.9) | 2739 (34.1) |

| • No | 319 (63.7) | 182 (36.3) |

| Total, n (%) | 8036 (94.1) | 501 (5.9) |

CAFPs—clinically active family physicians.

Including interprovincial migration (3.6%) and migration abroad (3.0%), which are not mutually exclusive.

P < .0001.

P < .3045.

Table 3. Predictors of planned interprovincial migration.

Logistic regression model (N = 8537).

| COVARIABLES | ODDS RATIO | 95% CI | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.944 | 0.932–0.956 | < .0001 |

| Male sex | 1.761 | 1.353–2.291 | < .0001 |

| Single, divorced, or widowed | 1.804 | 1.311–2.481 | .0003 |

| Without children or dependents | 1.209 | 0.930–1.572 | .1566 |

| Dissatisfaction | |||

| • With professional life | 1.676 | 1.299–2.162 | < .0001 |

| • With relationships with colleagues | 1.509 | 1.081–2.108 | .0158 |

| • With relationship with hospital | 1.384 | 1.020–1.879 | .0367 |

| • With ability to find locum tenens coverage | 1.088 | 0.848–1.396 | .5087 |

| Work setting | |||

| • Inner city, urban, or suburban (REF) | - | - | - |

| • Rural, isolated, or remote | 2.169 | 1.607–2.929 | < .0001 |

| • Small town | 1.507 | 1.115–2.035 | .0075 |

| • Mixed or other | 0.833 | 0.380–1.826 | .6473 |

| Province | |||

| • British Columbia (REF) | - | - | - |

| • Prairies | 8.519 | 4.960–14.633< .0001 | |

| • Atlantic Provinces | 4.944 | 2.865–8.530 | < .0001 |

| • Ontario | 2.087 | 1.250–3.487 | .0049 |

| • Alberta | 1.995 | 1.076–3.698 | .0282 |

| • Quebec | 1.532 | 0.860–2.730 | .1474 |

CI—confidence interval, REF—reference category.

Figure 1. Predictors of planned interprovincial migration.

Regression tree analysis, tree pruned at P=.001 (N=8537).

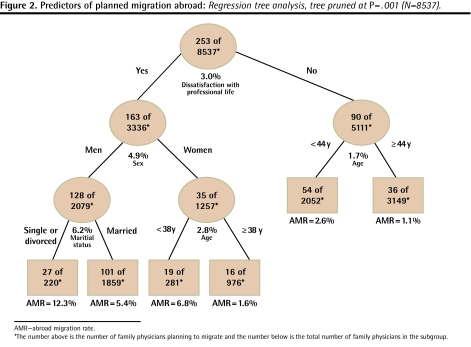

Variables associated with increased likelihood of migration abroad were similar to those for interprovincial migration, with the exception of geographic variables: the work setting was not associated with the risk of migration abroad, and the provinces that showed increased risk of physicians migrating abroad were the Prairies and Ontario (Table 4). The regression tree analysis (Figure 2) showed that the CAFPs who were most likely to migrate abroad were single, divorced, or widowed men dissatisfied with their professional lives. Very few CAFPs who were not dissatisfied with their professional lives planned to migrate abroad.

Table 4.

Predictors of planned migration abroad: Logistic regression model (N = 8537).

| COVARIABLES | ODDS RATIO | 95% CI | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.956 | 0.943–0.970 | < .0001 |

| Male sex | 2.207 | 1.644–2.963 | < .0001 |

| Single, divorced, or widowed | 1.790 | 1.272–2.519 | .0008 |

| Without children or dependents | 1.113 | 0.838–1.479 | .4601 |

| Dissatisfaction | |||

| • With professional life | 2.336 | 1.763–3.095 | < .0001 |

| • With relationships with colleagues | 1.282 | 0.913–1.798 | .1511 |

| • With relationship with hospital | 1.574 | 1.164–2.129 | .0032 |

| • With ability to find locum tenens coverage | 1.287 | 0.981–1.689 | .0683 |

| Work setting | |||

| • Inner city, urban, or suburban (REF) | - | - | - |

| • Rural, isolated, or remote | 1.032 | 0.708–1.505 | .8697 |

| • Small town | 0.916 | 0.651–1.289 | .6151 |

| • Mixed or other | 1.536 | 0.813–2.904 | .1865 |

| Region | |||

| • Alberta (REF) | - | - | - |

| • Prairies | 2.211 | 1.189–4.113 | .0122 |

| • Ontario | 1.703 | 1.021–2.838 | .0412 |

| • British Columbia | 1.575 | 0.886–2.798 | .1216 |

| • Quebec | 1.337 | 0.751–2.379 | .3236 |

| • Atlantic Provinces | 1.045 | 0.523–2.084 | .9017 |

CI—confidence interval, REF—reference category.

Figure 2. Predictors of planned migration abroad.

Regression tree analysis, tree pruned at P=.001 (N=8537).

DISCUSSION

In general, few CAFPs planned to relocate their practices to other provinces (3.6%) or other countries (3.0%) in the 2 years following the study. Moreover, these rates were higher than the actual migration rates observed between 2004 and 2006, as published by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).12,13 In these publications, the annual interprovincial migration rate was reported to be 1.2%, suggesting an estimated biannual rate of 2.4%, and only 0.5% of family physicians moved abroad. The differences between planned migration as reported by the NPS and actual migration as reported by CIHI can be explained by the fact that those CAFPs who considered migration might not all have been ready to implement such a major change in their professional and personal lives. This has been observed with other behavioural changes studies using the Stages of Change model, in which a substantial proportion of the population in the pre-action period (the contemplation and preparation stages) does not follow through with the action being considered.14 Another explanation for the discrepancy could be a gap between the estimated time by which the CAFPs planned to migrate and the time in which migration effectively occurred.

Among the Canadian CAFPs in our study, age and practising in the Prairies, and to a lesser extent practising in the Atlantic Provinces, were the most powerful predictors of planned interprovincial migration. These results are consistent with previous studies.4 Benarroch and Grant found that these regions experienced the highest rates of physician departures and a net loss of CAFPs on account of interprovincial migration between 1976 and 1992.3 Similar results were found in a later study by Baerlocher, who examined net changes in the provincial ratio of physicians-to-patients between 1987 and 2003.5 The other statistically significant predictors of planned interprovincial migration discovered in this study—sex (male), marital status (single, divorced, or widowed), dissatisfaction (with professional life, relationships with hospitals, relationships with colleagues), and work setting (rural, isolated, or remote)—are also consistent with the literature.4,15 Using regression tree analysis to account for any interaction between variables, we ended up with high- and low-risk profiles of CAFPs’ intentions to migrate to other provinces. Another benefit of the regression tree is its ability to estimate a threshold for continuous variables, such as age. The profiles generated by regression tree analysis were different according to regions of practice, and could be used by provincial health human resource planners to better understand and predict the movement of health care workers out of their respective provinces.

Surprisingly, unlike with the logistic regression models, sex was a not a statistically significant determinant in the regression tree models for planned migration, except in the subpopulation of CAFPs planning to move abroad who were dissatisfied with their professional lives. Dissatisfaction with professional life was the most important predictor of planned international migration, with 3 times the increased likelihood (Figure 2). In the prediction model for interprovincial migration, on the other hand, dissatisfaction was only marginal and was significant only for older CAFPs in some provinces (Figure 1). The complementary use of logistic and tree modeling analyses in this study might provide important information regarding the installation and maintenance of CAFPs in specific areas, particularly remote or rural locations.16,17

Among other changes planned by CAFPs, it is interesting to note that a much higher proportion of CAFPs planned to reduce their clinical practices compared with those who intended to increase them. The results of this survey confirm the worrying trend found by Pong and Pitblado,1 which must be addressed in order for rural or underserved populations in Canada to access health care.

Our study has some limitations. First, a response rate of 36% might raise concerns; however, the NPS was a census study with 11 041 family physician respondents. A follow-up comparison study concluded that there was high overall correlation (r = 0.98) between survey respondents and total population demographic characteristics, as well as between NPS respondents and nonrespondents (r = 0.94).18 We acknowledge that self-reported short-term intentions of CAFPs to change practices might not reflect real future changes. Further, to our knowledge, no published study has ever reported results on the correlation between intention to change and actual change with respect to physicians’ practices. In the future, the NPS might be able to provide information on this topic.

Conclusion

Only a few CAFPs planned to relocate their practices to other provinces (3.6%) or other countries (3.0%) in the 2 years following the study. Among Canadian CAFPS who participated in the study, younger age and practising in the Prairies and the Atlantic provinces were the most important predictors of planned interprovincial migration. Dissatisfaction with professional life was the most important predictor of planned migration abroad. These results can be used by provincial health human resource planners to better understand and predict the movement of health care workers out of their respective provinces.

Acknowledgment

This project was funded in part by the Geomatics for Informed Decisions Network (GEOIDE). Dr Vanasse was also supported by the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Sherbrooke, the Clinical Research Centre at Sherbrooke University Hospital, and the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Of the 8537 study respondents, 6203 clinically active family physicians (CAFPs) indicated that they intended to change their practices within 2 years. Of those planning practice changes, 1123 (13.2%) planned specifically to relocate—252 (3.0% of total study participants) planned to move to another country and 305 (3.6%) planned to move to another province or Territory within Canada.

Predictors of planned migration included age, sex, and marital status; specifically, young, male CAFPs who were single were more likely to be planning out-of-province relocation. Dissatisfaction with professional life and professional relationships and isolated, remote, or small-town clientele also predicted intention to relocate. Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and the Atlantic Provinces were most at risk of losing CAFPs to other provinces and Territories in Canada.

As delivery of health care is a provincial responsibility, comprehensive interprovincial migration profiles for each province could help health human resource planners to understand and predict the movement of health care workers and plan for optimal physician distribution across the country.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Sur les 8537 répondants, 6203 médecins de famille en pratique active (MFPA) déclaraient avoir l’intention de modifier leur pratique avant 2 ans. Parmi ceux-ci, 1123 (13,2 %) projetaient spécifiquement de déménager—252 (3,0 % de tous les participants) vers un autre pays, et 305 (3,6 %) vers un autre territoire ou province du Canada.

Les indicateurs de l’intention de déménager incluaient l’âge, le sexe et l’état civil; plus spécifiquement, les MFPA masculins, jeunes et célibataires étaient plus susceptibles d’envisager de quitter leur province. L’insatisfaction en rapport avec la pratique et les relations professionnelles, la pratique en régions isolées ou éloignées ou dans des petites municipalités étaient aussi des indicateurs de l’intention de déménager. La Saskatchewan, le Manitoba et les Provinces Maritimes étaient les plus susceptibles de perdre des MFPA à la faveur des autres provinces ou Territoires canadiens.

Les soins de santé étant du ressort des provinces, il serait utile d’établir les profils des migrations inter-provinciales pour chaque province afin d’aider les planificateurs des ressources humaines en santé à comprendre et prévoir les déplacements des travailleurs de la santé, et à planifier une meilleure distribution des médecins dans l’ensemble du pays.

Footnotes

Contributors

Drs Vanasse, Courteau, and Orzanco and Ms Scott contributed to concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

*Full text is available in English at www.cfp.ca.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Pong R, Pitblado R. Geographic distribution of physicians in Canada: beyond how many and where. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institutes for Health Information; 2006. [Accessed 2009 Feb 10]. Available from: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=PG_529_E&cw_topic=529&cw_rel=AR_1346_E. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Task Force Two. A physician human resource strategy for Canada. Final report. Ottawa, ON: Task Force Two; 2006; [Accessed 2009 Feb 10]. Available from: www.caper.ca/docs/articles_interest/pdf_TF2%20Strategic%20Report%20-%20ENG%20FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benarroch M, Grant H. The interprovincial migration of Canadian physicians: does income matter? [Accessed 2009 Feb 10];Appl Econ. 2004 36(20):2335–45. Available from: http://ideas.repec.org/a/taf/applec/v36y2004i20p2335-2345.html.

- 4.Basu K, Rajbhandary S. Interprovincial migration of physicians in Canada: what are the determinants? Health Policy. 2006;76(2):186–93. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baerlocher MO. The importance of foreign-trained physicians to Canada. Clin Invest Med. 2006;29(3):151–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dauphinee WD. The circle game: understanding physician migration patterns within Canada. Acad Med. 2006;81(12 Suppl):S49–54. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000243341.55954.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.College of Family Physicians of Canada, Canadian Medical Association, Royal College and Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. National physician survey. 2004 methodologies. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2006. [Accessed 2009 Feb 10]. Available from: www.nationalphysiciansurvey.ca/nps/2004_Survey/methods/methodologies-2004-e.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H, Springer B. New York, NY: Springer; 1999. Recursive partitioning in the health sciences. . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, Tsai CP, Yu CY, Bonney G. Tree-based linkage and association analyses of asthma. Genet Epidemiol. 2001;21(Suppl 1):S317–22. doi: 10.1002/gepi.2001.21.s1.s317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Bracken MB. Tree-based risk factor analysis of preterm delivery and small-for-gestational-age birth. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141(1):70–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang HP, Holford T, Bracken MB. A tree-based method in prospective studies. Stat Med. 1996;15(1):37–49. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960115)15:1<37::AID-SIM144>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Supply, distribution and migration of Canadian physicians, 2005. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2006. [Accessed 2009 Feb 10]. Available from: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=PG_587_E&cw_topic=587&cw_rel=AR_14_E. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Supply, distribution and migration of Canadian physicians, 2006. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2007. [Accessed 2009 Feb 10]. Available from: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=PG_870_E&cw_topic=870&cw_rel=AR_14_E. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. In: Hersen M, Eisler RM, Miller PM, editors. Progress in behavior modification. Vol. 28. New York, NY: Wadsworth Publishing; 1992. pp. 184–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H. Physician migration in non-metropolitan counties of the United States from 1987 to 1990. Chapel Hill, NC: Department of Health Policy and Administration, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bilodeau H, Leduc N. Inventory of the main factors determining the attraction, installation and retention of physicians in remote areas [in French] Cah Sociol Demogr Med. 2003;43(3):485–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilodeau H, Leduc N, Schendel NV. Analyse des facteurs d’attraction, d’installation et du maintien de la pratique médicale dans les régions éloignées du Québec. Rapport abrégé. Montreal, QC: Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire en santé; 2006. [Accessed 2009 Feb 10]. Available from: www.gris.umontreal.ca/rapportpdf/R06-03.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2004 National Physician Survey response rates and comparability of physician demographic distributions with those of the physician population. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2005. [Accessed 2009 Feb 10]. Available from: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=bl_npsmay2005_e. [Google Scholar]