Abstract

Objective To determine whether fluoroscopic guidance improves outcomes of injections for greater trochanteric pain syndrome.

Design Multicentre double blind randomised controlled study.

Setting Three academic and military treatment facilities in the United States and Germany.

Participants 65 patients with a clinical diagnosis of greater trochanteric pain syndrome.

Interventions Injections of corticosteroid and local anaesthetic into the trochanteric bursa, using fluoroscopy (n=32) or landmarks (that is, “blind” injections; n=33) for guidance.

Main outcome measures Primary outcome measures: 0-10 numerical rating scale pain scores at rest and with activity at one month (positive categorical outcome predefined as ≥50% pain reduction either at rest or with activity, coupled with positive global perceived effect). Secondary outcome measures included Oswestry disability scores, SF-36 scores, reduction in drug use, and patients’ satisfaction.

Results No differences in outcomes occurred favouring either the fluoroscopy or blind treatment groups. One month after injection the average pain scores were 2.7 at rest and 5.0 with activity in the fluoroscopy group compared with 2.2 and 4.0 in the blind injection group. Three months after the injection, 15 (47%) patients in the blind group and 13 (41%) in the fluoroscopy group continued to have a positive outcome.

Conclusion Although using fluoroscopic guidance dramatically increases treatment costs for greater trochanteric pain syndrome, it does not necessarily improve outcomes.

Trial registration Clinical trials NCT00480675

Introduction

Rapid advancements in elucidating the mechanisms of disease, preventive and diagnostic capabilities, and therapeutic interventions have not necessarily been reflected in better treatment outcomes. Nowhere is this incongruity more evident than in the management of pain. Although the field of pain management has seen a dramatic surge in recognition, research interest, resource allocation, and treatment options, the rates of pain related disability continue to soar.1 2 This disparity has led some experts to question the relations between scientific advancements, expenditures, and quality of health care.3 4

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome, also known as trochanteric bursitis, is a common medical condition with a lifetime prevalence exceeding 20%; it occurs more frequently in women, older people, and people with low back pain.5 6 7 8 9 Corticosteroid injections can provide considerable relief in most patients who fail to respond to conservative treatment.6 10 11 12 13 One epidemiological study in a primary care setting found that patients who received a corticosteroid injection had a 2.7-fold greater chance of long term recovery compared with patients who had not had an injection.14

Despite the prevalence of greater trochanteric pain syndrome, only a few studies evaluating the efficacy of corticosteroid injections have been published, none of which was controlled or used fluoroscopy or other imaging techniques (such as ultrasonography). The average success rate in these studies ranged between 50% and 70%, with follow-up ranging between two weeks and two years.8 10 11 15 16 Because many studies have shown that fluoroscopic guidance is necessary to ensure correct placement of the needle during many interventional pain treatments,17 18 19 20 21 22 an observational study sought to determine the accuracy of “blind” trochanteric bursa injections.23 Intra-bursal spread of contrast occurred in only 45% of landmark guided trochanteric bursa injections, and the authors concluded that fluoroscopic guidance is necessary to ensure placement of the needle within the bursa. However, this study did not assess outcomes.

In order to determine whether fluoroscopy should be routinely used during trochanteric bursa corticosteroid injections, we did a multicentre, randomised controlled study comparing fluoroscopically guided and blind procedures. This question is relevant for two reasons. Firstly, greater trochanteric pain syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, but recent studies have shown that only a small percentage of patients who meet inclusion criteria for greater trochanteric pain syndrome have radiological evidence of bursal inflammation.24 25 Extra-bursal hip injections might therefore be as effective as, or even superior to, intra-bursal trochanteric injections. Secondly, giving any injection under radiographic guidance usually requires pain management services. This adds to the cost of treatment, and the delays inherent in obtaining subspecialty care can impair outcomes of treatment.26 27 28

Methods

The trial took place between January 2007 and March 2008 at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, and Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, a US military treatment facility operating in Landstuhl, Germany. A two tailed power analysis determined that a sample size of 64 had 90% power to detect a 1.5 point difference in the 0-10 numerical rating scale pain scores between groups at a significance level (α) of 0.05.

All procedures took place in a pain clinic in an ambulatory care setting; superficial anaesthesia was used. Inclusion criteria included pain of more than three months’ duration, spontaneous pain in the lateral aspect of the hip, tenderness overlying the greater trochanter, and one of the following three minor diagnostic criteria: increased pain with extremes of rotation, abduction, or adduction; pain with forced hip abduction; and pseudoradicular pain extending down the lateral aspect of the thigh. Exclusion criteria included age under 18 years, trochanteric bursa injection within the previous nine months, coagulopathy, allergy to contrast dye, and unstable medical or psychiatric condition that might preclude an optimal treatment response.

Randomisation and treatment

A physician not involved in randomisation enrolled and treated all participants. Participants were randomised in a 1:1 ratio to receive either fluoroscopically guided or landmark guided (that is, “blind”) trochanteric bursa injections. A research nurse not involved in patient care randomised participants in blocks of four via pre-sealed envelopes at Johns Hopkins and the two military institutions, which we considered as a single entity. Patients were placed in the lateral position with the affected side up, after which the most tender area was marked over the anticipated site of the bursa. A “sham” cross table antero-posterior image of the femur was taken to facilitate blinding. Using only landmarks to guide needle insertion, the physician inserted a 22 gauge 3.5 inch spinal needle into the suspected bursa. The physician then injected 0.5 ml of contrast and took a true antero-posterior image to determine whether the contrast was within one of the subgluteus maximus or subgluteus medius trochanteric bursas. In those patients randomised to the “blind injection” group, the physician injected a 4 ml solution containing 60 mg of depo-methylprednisolone and 2.5 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine regardless of whether the contrast entered the bursa. For patients in the fluoroscopy group, the same solution was injected only if the image revealed intra-bursal spread. If the injection was extra-bursal, the physician then readjusted the needle and repeated the process until intra-bursal spread of contrast was confirmed, at which point the injectate was administered. At the conclusion of the procedure, the patient was asked which group they thought they were allocated to.

Outcome measures and follow-up

A physician unaware of the patient’s study group assignment obtained all outcome data during scheduled follow-up visits. Between the procedure and first follow-up, we permitted no contact between any patient and investigator. All patients were seen in the treating clinic one month after the procedure. If a patient had a positive global perceived effect and significant (≥50%) pain relief obviating the need for further treatment, he or she was re-evaluated three months post-treatment. Patients who did not have adequate pain relief one month after the procedure were unblinded and left the study to receive alternative medical care. The rationale for this decision was based on pilot data showing that only 7% of patients who failed to experience relief one month after a trochanteric bursa injection had a positive outcome 8-12 weeks post-procedure with no intervening treatment. Patients who continued to receive satisfactory pain relief were unblinded after their final three month follow-up. The two main questions we sought to answer were whether fluoroscopically guided trochanteric bursa injections were superior to “blinded” injections and whether intra-bursal injections were better than extra-bursal injections.

The primary outcome measures were pain scores on a 0-10 numerical rating scale at rest and with activity one month post-injection, which reflected the average pain the patient experienced over the preceding week. Secondary outcome measures were the SF-36, Oswestry disability index, reduction in drug use (predefined as a 20% reduction in opioid use or complete cessation of a non-opioid analgesic),29 global perceived effect, and a composite “successful outcome.” The SF-36 is a well validated instrument used to measure the effects of medical conditions on eight health related domains believed to be universally important, which are not specific to age, treatment, or disease.30 The Oswestry disability index is a well validated instrumented designed to assess functional limitations secondary to leg or back pain.31 In general, scores on this index of 0-20 indicate minimal disability, 21-40 indicates moderate disability, and 41-60 indicates severe disability. We defined a positive global perceived effect as a positive response to all three of “My pain has improved/worsened/stayed the same since my last visit,” “The treatment I received improved/did not improve my ability to perform daily activities,” and “I am satisfied/not satisfied with the treatment I received and would recommend it to others.”

We designated the composite binary variable “successful outcome” before the start of the study as a reduction of at least 50% in numerical rating scale pain score either at rest or with activity and a positive global perceived effect obviating the need for further interventions. In addition to outcome measures, other variables analysed were age, sex, whether the injectate was intra-bursal or extra-bursal, duration of pain, opioid usage, adequacy of blinding, accuracy of injection, and obesity (body mass index ≥30).

We used Stata MP 10.1 for statistical analyses. We present normally distributed data as means and standard deviations. We assessed statistical significance by using t tests for continuous, normally distributed variables; the Wilcoxon sign rank test for non-normally distributed, paired data; and Pearson’s χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. We considered a P value <0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

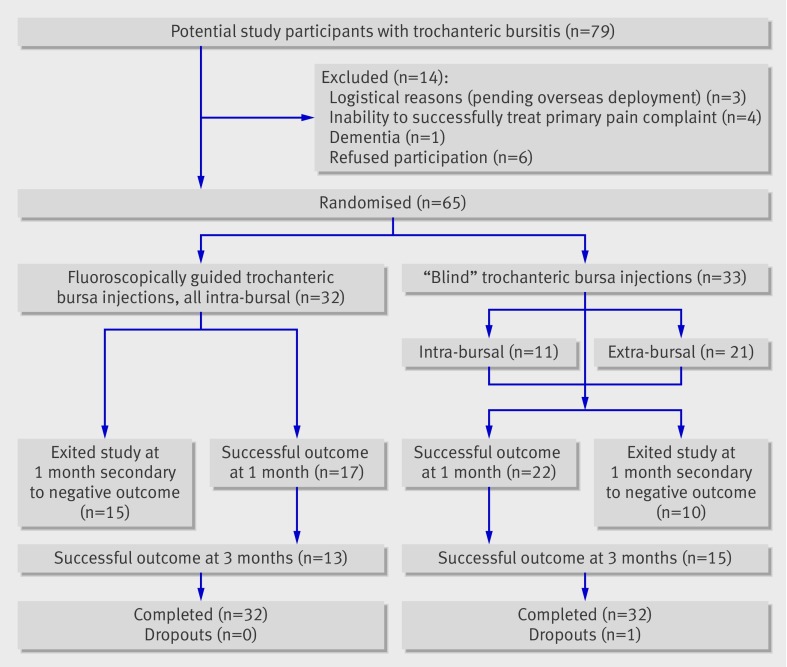

The figure shows the flow of participants through the study. Tables 1 and 2 show demographic data for participants in each study centre and by method of injection. Overall, neither baseline differences between study centres nor those between injection method groups were statistically significant, indicating that randomisation was successful. Most patients were women, in their mid-50s, not obese, and not using opioid analgesics, although patients at Landstuhl Regional Medical Center were substantially younger than those at the other sites, which reflects the nature of the beneficiaries of the US Department of Defense treated there. Patients randomised to receive a blind injection reported a mean duration of pain of 4.4 years, whereas those allocated to receive fluoroscopically guided injections had had pain for an average of 3.3 years. Average pain intensity at rest was moderate, but it increased to severe with activity. Baseline ability to function was severely limited in the blind injection group and moderately limited in the fluoroscopic group, although the between group differences were small.

Flow of participants through study

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by study centre. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Johns Hopkins (n=36) | Walter Reed (n=20) | Landstuhl (n=9) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD, range) age (years) | 57.9 (12.6, 30-85) | 59.1 (11.9, 34-79) | 35.4 (10.5, 21-53) | <0.0001 |

| Female sex | 32 (89) | 19 (95) | 5 (56) | 0.02 |

| Obesity | 8 (22) | 8 (40) | 1 (11) | 0.21 |

| Mean (SD, range) duration of pain (years) | 4.1 (4.2, 0.1-16) | 3.1 (2.4, 0.1-7.5) | 4.8 (3.5, 0.3-10) | 0.49 |

| Opioid use | 15 (42) | 5 (25) | 2 (22) | 0.41 |

| Mean (SD, range) Oswestry disability index score | 43.3 (13.1, 18-67) | 36.8 (14.9, 14-62) | 37.2 (12.5, 20-54) | 0.18 |

| Mean (SD, range) pain intensity at rest* | 5.5 (5.0, 1-10) | 4.2 (2.4, 1-9) | 3.6 (1.2, 2-6) | 0.06 |

| Mean (SD, range) pain intensity with activity* | 8.0 (1.9, 3-10) | 7.1 (2.3, 2-10) | 6.4 (1.4, 3.5-8) | 0.07 |

| Success: | (n=35) | (n=20) | (n=9) | 0.49 |

| None | 11 (31) | 11 (55) | 3 (33) | |

| At 1 month only | 7 (20) | 3 (15) | 1 (11) | |

| At 3 months | 17 (49) | 6 (30) | 5 (56) |

*Numerical rating pain scale.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by injection method. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Blind (n=33) | Fluoroscopically guided (n=32) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD, range) age (years) | 56.1 (15.5, 21.0-85.0) | 54.3 (13.3, 30.0-76.0) | 0.62 |

| Female sex | 28 (85) | 28 (88) | 1.0 |

| Obesity | 8 (24) | 9 (28) | 0.72 |

| Mean (SD, range) duration of pain (years) | 4.4 (3.9, 0.1-16.0) | 3.3 (3.4, 0.2-13.0) | 0.23 |

| Opioid use | 12 (36) | 10 (31) | 0.66 |

| Mean (SD, range) Oswestry disability index score | 42.2 (12.6, 16.0-64.0) | 38.6 (14.9, 14.0-67.0) | 0.30 |

| Mean (SD, range) pain intensity at rest* | 4.6 (2.6, 1.0-10.0) | 5.1 (2.6, 1.0-10.0) | 0.43 |

| Mean (SD, range) pain intensity with activity* | 7.2 (2.0, 2.0-10.0) | 7.8 (2.2, 2.0-10.0) | 0.32 |

| Treatment centre: | 0.24 | ||

| Johns Hopkins Medical Center | 17 (52) | 19 (59) | |

| Walter Reed Army Medical Center | 9 (27) | 11 (34) | |

| Landstuhl Regional Medical Center | 7 (21) | 2 (6) |

*Numerical rating pain scale.

In the fluoroscopy group, 12 of 32 injections entered the bursa on the first attempt compared with 12 of 33 in the landmark guided treatment group, for an overall accuracy rate of 37%. In the overall cohort, 39 (61%) of the 64 patients experienced a positive categorical outcome (≥50% pain relief and satisfaction with the results) at one month and therefore remained in the study for their three month follow-up. At three months, 28 (44%) participants continued to report substantial relief coupled with a positive global perceived effect; we found no significant differences between treatment groups.

Table 3 shows scores for each of the SF-36 scales stratified by injection method. The only statistically significant difference was in the mental health scale at the one month follow-up; patients who received a blind injection reported slightly better scores. Other differences tended to be in favour of the blind injection group, with the exception of emotional roles at baseline, physical roles and bodily pain at one month, and physical functioning at three months.

Table 3.

SF-36 scale scores by injection method. Values are mean (SD, range) unless stated otherwise

| Scale | Baseline | Month 1 | Month 3 | 1998 US norms* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blind (n=33) | Fluoroscopically guided (n=32) | P value | Blind (n=32) | Fluoroscopically guided (n=30) | P value | Blind (n=20) | Fluoroscopically guided (n=15) | P value | ||||

| Physical functioning | 36.1 (24.5, 0.0-95.0) | 33.1 (22.7, 5.0-75.0) | 0.62 | 43.6 (21.8, 5.0-95.0) | 45.2 (29.9, 5.0-95.0) | 0.81 | 44.5 (22.0, 5.0-90.0) | 45.7 (26.7, 5.0-90.0) | 0.89 | 83.0 | ||

| Physical roles | 25.0 (38.5, 0.0-100.0) | 18.8 (29.1, 0.0-100.0) | 0.46 | 37.5 (42.1, 0.0-100.0) | 38.3 (43.9, 0.0-100.0) | 0.94 | 35.0 (39.2, 0.0-100.0) | 28.3 (37.6, 0.0-100.0) | 0.61 | 77.9 | ||

| Bodily pain | 40.5 (16.8, 10.0-77.5) | 35.7 (20.0, 0.0-77.5) | 0.31 | 55.5 (19.3, 10.0-90.0) | 58.3 (21.5, 32.5-100.0) | 0.58 | 48.3 (19.0, 10.0-90.0) | 48.5 (22.7, 22.5-90.0) | 0.97 | 70.2 | ||

| General health | 63.8 (13.3, 35.0-92.0) | 55.3 (22.4, 15.0-97.0) | 0.07 | 67.3 (17.1, 30.0-92.0) | 58.1 (25.0, 20.0-100.0) | 0.10 | 65.6 (18.6, 20.0-97.0) | 59.7 (19.6, 25.0-87.0) | 0.37 | 70.1 | ||

| Vitality | 40.6 (20.9, 10.0-80.0) | 39.1 (18.7, 0.0-75.0) | 0.75 | 50.9 (18.5, 0.0-80.0) | 44.7 (25.3, 5.0-85.0) | 0.27 | 49.8 (20.0, 20.0-80.0) | 41.0 (19.0, 5.0-80.0) | 0.20 | 57.0 | ||

| Social functioning | 61.7 (22.1, 25.0-100.0) | 52.3 (26.6, 0.0-100.0) | 0.13 | 69.9 (21.7, 25.0-100.0) | 64.2 (26.2, 12.5-100.0) | 0.35 | 66.9 (27.3, 25.0-100.0) | 62.5 (23.1, 25.0-100.0) | 0.61 | 83.6 | ||

| Emotional roles | 52.5 (42.5, 0.0-100.0) | 54.2 (44.6, 0.0-100.0) | 0.88 | 69.8 (37.3, 0.0-100.0) | 56.7 (45.6, 0.0-100.0) | 0.22 | 71.7 (34.7, 0.0-100.0) | 53.3 (39.4, 0.0-100.0) | 0.16 | 83.1 | ||

| Mental health | 70.9 (16.6, 32.0-96.0) | 68.0 (19.3, 24.0-100.0) | 0.52 | 76.0 (15.2, 48.0-100.0) | 65.5 (20.8, 24.0-92.0) | 0.03 | 73.6 (16.2, 40.0-96.0) | 65.3 (23.4, 20.0-92.0) | 0.25 | 75.2 | ||

*SF-36 normative data for US general population in 1998. Available at www.sf-36.org/cgi-bin/nbscalc/nbs2.cgi?PF=100&RP=100&BP=100&GH=100&VT=100&SF=100&RE=100&MH=100&CC=us2.

When examined by success at three months, the clinical and demographic characteristics of the study participants were similar (table 4). Despite the lack of statistical significance, an unsuccessful treatment at three months was more common among men, obese people, patients with shorter duration of pain, and those with greater disability on the Oswestry disability index.

Table 4.

Clinical and demographic characteristics stratified by success at three months (n=64). Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Not successful (n=36) | Successful (n=28) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD, range) age (years) | 55.9 (14.4, 22-79) | 54.6 (14.8, 21-85) | 0.74 |

| Female sex | 30 (83) | 25 (89) | 0.72 |

| Obesity | 11 (31) | 6 (21) | 0.57 |

| Mean (SD, range) duration of pain (years) | 2.7 (2.4, 0.1-9.0) | 5.4 (4.5, 0.3-16.0) | 0.40 |

| Opioid use | 12 (33) | 9 (32) | 0.92 |

| Mean (SD, range) Oswestry disability index (pre-procedure) | 42.8 (12.6, 14-67) | 36.6 (14.3, 14-60) | 0.46 |

| Mean (SD, range) baseline pain intensity at rest* | 4.8 (2.6, 1-10) | 4.7 (2.6, 1-10) | 0.26 |

| Mean (SD, range) baseline pain intensity with activity* | 7.5 (1.8, 3-10) | 7.5 (2.4, 2-10) | 0.46 |

*Numerical rating pain scale.

We examined outcomes by injection method, number of injections (data not shown), and whether the injection was intra-bursal or extra-bursal (tables 5 and 6). For the primary outcome measure, numerical rating scale score at one month, the mean hip pain score at rest declined from 5.1 to 2.7 (P=0.0001) in the fluoroscopically guided injection group and from 4.6 to 2.2 (P=0.0001) in the blind injection group. With respect to activity related pain intensity, scores in the fluoroscopy group fell from 7.8 to 5.0 (P<0.0001) at one month, which was comparable to the improvement found in the blind injection group (decrease from 7.2 to 4.0; P<0.0001). Other differences between the injection method groups also failed to reach statistical significance, apart from a greater decrease in disability among patients who received blind injections. However, we noted trends for greater improvement in pain at rest at three months in the fluoroscopy group and a positive global perceived effect in the blind injection group.

Table 5.

Outcomes stratified by injection method. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome | Blind | Fluoroscopically guided | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall success: | (n=32) | (n=32) | 0.38 |

| None | 10 (31) | 15 (47) | |

| At 1 month only | 7 (22) | 4 (13) | |

| At 3 months | 15 (47) | 13 (41) | |

| Mean (SD, range) pain intensity* at 1 month: | (n=32) | (n=32) | |

| Rest | 2.2 (2.4, 0-10) | 2.7 (2.5, 0-9) | 0.41 |

| Activity | 4.0 (2.6, 0-10) | 5.0 (2.9, 0-10) | 0.16 |

| Mean (SD, range) pain intensity* at 3 months: | (n=22) | (n=16) | |

| Rest | 2.6 (2.5, 0-7.5) | 1.9 (1.7, 0-6) | 0.34 |

| Activity | 4.8 (2.6, 0-10.0) | 4.7 (2.8, 0-10) | 0.90 |

| Mean (SD, range) Oswestry disability index at 1 month† | 32.1 (15.2, 0-60) | 32.3 (17.4, 0-66) | 0.96 |

| Mean (SD, range) Oswestry disability index at 3 months† | 31.7 (15.1, 6-64) | 33.6 (13.6, 14-60) | 0.69 |

| Positive global perceived effect at 3 months‡: | (n=32) | (n=32) | 0.80 |

| No | 15 (47) | 16 (50) | |

| Yes | 17 (53) | 16 (50) | |

| Reduction in drug use at 3 months: | (n=19) | (n=15) | 0.60 |

| No | 11 (58) | 10 (67) | |

| Yes | 8 (42) | 5 (33) |

*Numerical rating pain scale.

†Lower Oswestry disability index indicates better functioning.

‡Failed treatment at one month carried over as negative global perceived effect at three months.

Table 6.

Outcomes stratified by injection location. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome | Intra-bursal (all fluoroscopically guided injections plus blind injections into bursa) | Extra-bursal (blind injections not in bursa) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall success: | (n=43) | (n=20) | 0.72 |

| None | 18 (42) | 6 (30) | |

| At 1 month only | 7 (16) | 4 (20) | |

| At 3 months | 18 (42) | 10 (50) | |

| Mean (SD, range) pain intensity* at 1 month: | (n=43) | (n=20) | |

| Rest | 2.6 (2.4, 0-9) | 2.2 (2.6, 0-10) | 0.54 |

| Activity | 4.7 (2.9, 0-10) | 4.3 (2.6, 0-10) | 0.62 |

| Mean (SD, range) pain intensity* at 3 months: | (n=24) | (n=14) | |

| Rest | 2.0 (1.8, 0-6) | 2.8 (2.8, 0-7.5) | 0.32 |

| Activity | 4.6 (2.8, 0-10) | 4.9 (2.6, 1-10) | 0.82 |

| Mean (SD, range) Oswestry disability index at 1 month† | 29.7 (17.4, 0-66, n=43) | 37.8 (12.4, 18-60, n=20) | 0.07 |

| Mean (SD, range) Oswestry disability index at 3 months† | 31.2 (13.0, 9-60, n=24) | 34.8 (16.6, 6-64) | 0.46 |

| Positive global perceived effect at 3 months:‡ | (n=43) | (n=20) | 0.78 |

| No | 21 (49) | 9 (45) | |

| Yes | 22 (51) | 11 (55) | |

| Drug reduction at 3 months: | (n=22) | (n=12) | 0.14 |

| No | 16 (73) | 5 (42) | |

| Yes | 6 (27) | 7 (58) |

*Numerical rating pain scale.

†Lower Oswestry disability index indicates better functioning.

‡Failed treatment at one month carried over as negative global perceived effect at three months.

When stratified by the number of injections—one injection (all blind injections plus intra-bursal on first attempt in fluoroscopy group) versus more than one injection (two or more attempts for intra-bursal spread in fluoroscopy group)—the outcomes for single and multiple injection groups were essentially comparable. Although the decrease in mean Oswestry disability index score was significantly greater in the single injection group (P=0.003), we found a greater improvement in the multiple injection group for the SF-36 general health subscale (P=0.02).

When examined by location of injection, no significant differences existed between the intra-bursal and extra-bursal groups. However, we noted trends for greater improvement in pain at rest at three months and the SF-36 general health category for intra-bursal injections, and for drug reduction and the SF-36 vitality index for extra-bursal spread of contrast.

At the time of discharge, blinding was assessed by an independent evaluator who asked patients which group they believed they were allocated to. Among the 56 patients who could give an answer, 23 guessed correctly, indicating adequacy of blinding. No complications were noted in any patient.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study suggests that the use of fluoroscopy does not improve outcomes in patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome who receive corticosteroid injections. This is consistent with our secondary finding showing comparable success rates for intra-bursal and extra-bursal injections. The results from this pilot study should not be surprising considering that most patients clinically diagnosed as having greater trochanteric pain syndrome have no radiological evidence of bursal inflammation.24 25 Even among patients with actual “trochanteric bursitis,” many develop secondary pathology in adjacent tissues.5 In these patients, using radiographic guidance to direct the needle into the bursa in patients with an extra-bursal pain generator might be counterproductive. However, subgroup analysis did not reveal any significant differences in outcomes in fluoroscopy patients who needed more than one needle placement before injection (45% success rate at three months) and patients in whom only one injection attempt was made (44% success rate).

Our results suggest that referral to a pain specialist with fluoroscopic capability is not warranted in most patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome who present to a primary care doctor, physiatrist, or surgeon, all of whom often encounter this condition. The delay in treatment entailed by referral to a subspecialty may even be detrimental, as previous interventional studies have found an inverse relation between duration of pain and likelihood of success.26 27 28 Patients who fail “blind” trochanteric bursa injections and those with radiological evidence of bursal inflammation, however, may benefit from referral to a pain treatment centre, as this study (37% accuracy rate) and a previous one found that injections guided by landmarks alone are unlikely to diffuse into the bursa.23 On the basis of current third party reimbursement codes for the 10 most recent procedures done at Johns Hopkins, the cost for a subspecialty consultation and subsequent procedure using fluoroscopy (including facility fees) is $1216 (£843; €897), compared with $188 if the procedure is done during an office visit.

An examination of the relative strengths and weaknesses of this study is needed to put the results in context. Firstly, this is the only controlled study that has evaluated trochanteric bursa injections. The absence of controlled studies is somewhat surprising, considering that a recent audit found that the number of procedures billed to Medicare, the largest health insurance supplier in the United States, under the current procedural terminology code pertaining to “major joint or bursa injection,” which includes trochanteric bursa injections, far exceeds that of any other pain management intervention.32 Secondly, our outcomes are less positive than several others reported for trochanteric bursa injections.10 11 However, all previous studies evaluating trochanteric bursa injections were unblinded and uncontrolled, which tends to accentuate expectation bias. Nevertheless, larger, placebo controlled studies are needed to better ascertain the efficacy of trochanteric bursa corticosteroid injections.

Another concern about this study stems from the fact that only 39 of the 65 participants had outcome data recorded at three months. This was justified on the basis of ethical concerns stemming from pilot data showing that less than 10% of patients with “negative” outcomes at one month would experience a “positive” outcome three months post-injection with no intervening treatment. However, not carrying over one month treatment failures limits the long term conclusions on efficacy and differences between treatment groups that can be reached from these results.

The implications of this study may also extend beyond the sphere of “hip pathology,” as they suggest that more sophisticated and expensive treatments do not necessarily translate into higher quality care or better outcomes. As an example, we need only examine the historical record of treatment for back pain, where rapidly evolving technological advances have not resulted in parallel declines in prevalence or in disability claims.33

Conclusions

Fluoroscopically guided trochanteric bursa injections were not associated with superior outcomes to injections guided by landmarks alone in patients who presented with clinical greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Referral to a pain treatment centre should be reserved for patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome who fail landmark guided injections and conservative treatment. Because a single study of this size is not sufficient to change practice, further studies are needed both to confirm the efficacy of trochanteric bursa injections in greater trochanteric pain syndrome and to determine which patients may benefit from each approach.

What is already known on this topic

Trochanteric bursa injections have been shown to reduce pain and disability for patients with clinical bursitis

Although no standard exists for giving bursa injections, a recent study found that only a minority of non-fluoroscopically guided injections end up in the bursa

What this study adds

Referring patients for fluoroscopically guided injections, which increases treatment costs by more than 600%, does not necessarily improve outcomes

Contributors: SPC conceived and designed the study. SPC, JM, AG, and NW wrote the protocols for the participating institutions. SAS analysed the data. SPC and SAS drafted the manuscript. SPC, LF, KW, MC, CN, and NW recruited and enrolled patients and gave injections. CK and JM randomised participants and assisted with follow-up. All authors edited the final version of the manuscript. SPC is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded in part by a congressional grant from the John P Murtha Neuroscience and Pain Institute, Johnstown, PA; the US Army; and the Army Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Initiative, Washington, DC. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Internal review boards at Johns Hopkins and Walter Reed Army Medical Center gave approval for the study. Landstuhl Regional Medical Center fell under the jurisdiction of Walter Reed Army Medical Center. All patients gave informed consent.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b1088

References

- 1.Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA. Issues in health care: interventional pain management at the crossroads. Pain Physician 2007;10:261-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strine TW, Hootman JM, Chapman DP, Okoro CA, Balluz L. Health-related quality of life, health risk behaviors, and disability among adults with pain-related activity difficulty. Am J Public Health 2005;95:2042-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. World health report 2000: health systems—improving performance. Geneva: WHO, 2000.

- 4.Weinstein JN. Threats to scientific advancement in clinical practice. Spine 2007;32(11 suppl):S58-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segal NA, Felson DT, Torner JC, Zhu Y, Curtis JR, Niu J, et al. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: epidemiology and associated factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88:988-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swezey RL. Pseudo-radiculopathy in subacute trochanteric bursitis of the subgluteus maximus bursa. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1976;57:387-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collee G, Dijkmans BA, Vandenbroucke JP, Rozing PM, Cats A. A clinical epidemiological study in low back pain: description of two clinical syndromes. Br J Rheumatol 1990;29:354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tortolani PJ, Carbone JJ, Quartararo LG. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome in patients referred to orthopedic spine specialists. Spine J 2002;2:251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson TP. Trochanteric bursitis: diagnostic criteria and clinical significance. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1958;39:617-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ege Rasmussen KJ, Fano N. Trochanteric bursitis: treatment by corticosteroid injection. Scand J Rheumatol 1985;14:417-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shbeeb MI, O’Duffy D, Michet CJ Jr, O’Fallon WM, Matteson EL. Evaluation of glucocorticosteroid injection for the treatment of trochanteric bursitis. J Rheumatol 1996;23:2104-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon EJ. Trochanteric bursitis and tendinitis. Clin Orthop 1961;20:193-202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krout RM, Anderson TP. Trochanteric bursitis: management. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1959;40:8-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lievense A, Bierma-Zienstra S, Schouten A, Bohnen A, Verhaar J, Koes B. Prognosis of trochanteric pain in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:199-204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker P, Kannangara S, Bruce WJ, Michael D, Van der Wall H. Lateral hip pain: does imaging predict response to localized injection? Clin Orthop Rel Res 2007;457:144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raman D, Haslock I. Trochanteric bursitis—a frequent cause of ‘hip’ pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1982;41:602-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fredman B, Ben Nun M, Zohar E, Iraqi G, Shapiro M, Gepstein R, et al. Epidural steroids for treating ‘failed back surgery syndrome’: is fluoroscopy really necessary? Anesth Analg 1999;88:367-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White AH, Derby R, Wynne G. Epidural injections for the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Spine 1980;5:78-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stojanovic MP, Vu TN, Caneris O, Slezak J, Cohen SP, Sang CN. The role of fluoroscopy in cervical epidural steroid injections: an analysis of contrast dispersal patterns. Spine 2002;27:509-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renfrew DL, Moore TE, Kathol MH, el-Khoury GY, Lemke JH, Walker CW. Correct placement of epidural steroid injections: fluoroscopic guidance and contrast administration. Am J Neuroradiol 1991;12:1003-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg JM, Quint TJ, de Rosayro AM. Computerized tomographic localization of clinically-guided sacroiliac joint injections. Clin J Pain 2000;16:18-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fishman SM, Caneris OA, Bandman TB, Audette JF, Borsook D. Injection of the piriformis muscle by fluoroscopic and electromyographic guidance. Reg Anesth Pain Med 1998;23:554-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen SP, Narvaez J, Stojanovic MP, Lebovits A. Corticosteroid injections for trochanteric bursitis: is fluoroscopy necessary? A pilot study. Br J Anaesth 2005;94:100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kingzett-Taylor A, Tirman PF, Feller J, McGann W, Prieto V, Wischer T, et al. Tendinosis and tears of gluteus medius and minimus muscles as a cause of hip pain: MR imaging findings. Am J Roentgenol 1999;173:1123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bird PA, Oakley SP, Shnier R, Kirkham BW. Prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging and physical examination findings in patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2138-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez RS, Zuurmond WW, Bezemer PD, Kuik DJ, van Loenen AC, de Lange JJ, et al. The treatment of complex regional pain syndrome type I with free radical scavengers: a randomized controlled study. Pain 2003;102:297-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benzon HT. Epidural steroid injections for low back pain and lumbosacral radiculopathy. Pain 1986;24:277-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen SP, Hurley RW, Christo PJ, Winkley J, Mohiuddin MM, Stojanovic MP. Clinical predictors of success and failure for lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. Clin J Pain 2007;23:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen SP, Wenzell D, Hurley RW, Kurihara C, Buckenmaier CC 3rd, Griffith S, et al. Intradiscal etanercept as a treatment for discogenic low back pain and sciatica: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response pilot study. Anesthesiology 2007;107:99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McHorney CA, Ware Jr JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): II, psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care 1993;31:247-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fairbank JCT, Couper J, Davies JB, O’Brien JP. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy 1980;66:271-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manchikanti L. The growth of interventional pain management in the new millennium: a critical analysis of utilization in the Medicare population. Pain Physician 2004;7:465-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pengel LH, Herbert RD, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. Acute low back pain: systematic review of its prognosis. BMJ 2003;327:323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]