Abstract

Natural killer T (NKT) cells comprise a novel T-lymphocyte subset that can influence a wide variety of immune responses through their ability to secrete large amounts of a variety of cytokines. Although variation in NKT-cell number and function has been extensively studied in autoimmune disease-prone mice, in which it has been linked to disease susceptibility, relatively little is known of the natural variation of NKT-cell number and function among normal inbred mouse strains. Here, we demonstrate strain-dependent variation in the susceptibility of C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice to NKT-mediated airway hyperreactivity, which correlated with significant increases in serum interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 elicited by the synthetic glycosphingolipid α-galactosylceramide. Examination of NKT-cell function revealed a significantly greater frequency of cytokine-producing NKT cells in C57BL/6J versus BALB/cJ mice as well as significant differences in the kinetics of NKT-cell cytokine production. Extension of this analysis to a panel of inbred mouse strains indicated that variability in NKT-cell cytokine production was widespread. Similarly, an examination of NKT-cell frequency revealed a significantly greater number of liver NKT cells in the C57BL/6J mice versus BALB/cJ mouse livers. Again, examination of a panel of inbred mouse strains revealed that liver NKT-cell numbers were quite variable, spanning over a 100-fold range. Taken together, these results demonstrate the presence of widespread natural variation in NKT-cell number and function among common inbred mouse strains, which may have implications for the examination of the influence of NKT cells in immune responses and disease pathogenesis among different genetic backgrounds.

Keywords: asthma, liver, mouse, NKT cells

Introduction

Natural killer T (NKT) cells comprise a unique T-cell subset that can influence a wide variety of immune responses and that have been implicated in autoimmunity, inflammation, tumour immunology, allergy and asthma, and infectious disease.1 Classical semi-invariant NKT cells are characterized by their unusual T-cell receptor (TCR), which consists of an invariant TCR α chain (Vα14Jα18 in the mouse) paired with a restricted set of TCR β chains (Vβ8.2, Vβ7 and Vβ2 in the mouse).1 Unlike conventional αβ T cells that recognize peptides presented by class I or class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, NKT cells recognize glycolipids presented by the MHC class I-like CD1d molecule.2 Stimulation of NKT cells occurs via both exogenously acquired, as well as endogenously produced, glycolipids.2–5 The most widely characterized model CD1d ligand is the marine sponge glycosphingolipid α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer), which induces the rapid stimulation of the entire semi-invariant NKT-cell subset.2 While αGalCer is not known to exist in vertebrates, it does bear a striking resemblance to recently described bacterial cell wall glycolipids that activate NKT cells in a CD1d-dependent manner,6–8 and remains a useful tool with which to identify and study NKT cells.

Rapid production by NKT cells of a wide variety of cytokines elicits the downstream activation of both innate and adaptive immune cell subsets such as NK cells, dendritic cells, and B cells.9–13 Upon activation, NKT cells produce both T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokines [e.g. interferon-γ (IFN-γ) tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)] as well as Th2 cytokines [e.g. interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-10 and IL-13].14 Accordingly, they have been observed to play roles in both proinflammatory15,16 as well as tolerogenic17 immune responses. These characteristics suggest that NKT cells could play a pivotal early role in shaping developing immune responses.

Altered NKT-cell number and function has been linked to autoimmunity.18 NOD/Lt mice, which spontaneously develop symptoms of type I diabetes, exhibit low numbers of NKT cells as well as a deficiency in NKT-cell IL-4 production.19–24 Similarly, depressed and elevated NKT-cell numbers have been observed in certain strains susceptible to experimental autoimmune encephalitis25,26 and systemic lupus erythematosus,27–29 respectively, suggesting a general link between the variation in NKT-cell number and the regulation of autoimmunity. However, despite the mounting evidence suggesting that NKT cells play critical roles in a variety of diseases with well-described variable strain-dependent pathologies, and despite reports suggesting that NKT-cell function is variable in normal strains of mice,30–32 there has been little direct characterization of NKT-cell function and number among common inbred strains of mice.

We have previously observed strain-dependent variation in the susceptibility of C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice to NKT-cell-mediated pregnancy loss.30 In this study, we confirm this strain-dependent variation using a separate model of NKT-mediated disease, αGalCer-induced airway hyperreactivity (AHR). Direct examination of NKT-cell number and function in these and other common strains of mice revealed the presence of widespread variation in liver NKT-cell numbers, as well as widespread variation in the kinetics and magnitude of the NKT-cell cytokine production in vivo. Variation in NKT-cell number and function, therefore, is widespread among many common inbred strains. Given the wide variety of immune responses that are affected by NKT cells, these findings may have implications for the examination of the influence of NKT cells in immune responses and disease pathogenesis among different genetic backgrounds.

Materials and methods

Mice and treatments

C57BL/6J, BALB/cJ, BALB/cByJ, CByB6/J, 129S1/SvImJ, A/HeJ, A/J, AKR, C3H/HeJ, DBA/2J, LG/J, NZB/BlnJ, NZW/LaCJ, FVB/NJ, BUB/BnJ and SM/J mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and were housed for at least 1 week in the specific pathogen-free barrier facility at the University of Vermont before use in experiments. CD1d−/− mice, backcrossed to C57BL/6 for more than 10 generations, were a gift from Mark Exley (Beth Israel Deaconess, Boston, MA) and were maintained in our facility. Jα18−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background were a gift from Masaru Taniguchi (Riken Institute, Yokohama City, Japan) and were maintained in our facility. Mice were given free access to food and water and maintained on a 12 hr/12 hr light/dark cycle. All procedures involving animals were approved by the University of Vermont Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

The αGalCer (Axxora Pharmaceuticals, San Diego, CA) was prepared by resuspension in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 0·5% Tween-20, followed by dilution in sterile PBS, pH 7·4. αGalCer (100 ng/g) or vehicle (PBS, 0·05% Tween-20) was administered by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection in a 100 μl volume.

Cell isolation

Splenocytes and thymocytes were obtained by gently pressing the tissue through a 70 μm-mesh screen, followed by red blood cell lysis using Gey’s solution. For intrahepatic lymphocyte (IHL) isolation, mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane and then perfused with 20 cm3 PBS, pH 7·4. For perfusion, PBS was administered using a 22-gauge needle inserted into the left ventricle, after which a small incision was made in the right atrium. Perfused livers were removed, weighed, and gently pressed through a 70-μm sieve, followed by resuspension and washing in PBS/2% fetal calf serum (FCS). The IHLs were prepared by centrifugation through a 33·8% Percoll (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ)/PBS gradient at 900 g for 12 min at 23°, after which they were washed in PBS/2% FCS. Red blood cells were lysed using Gey’s solution.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained at 4° in PBS/2% FCS containing 0·1% sodium azide. Fc block (anti-FcγIII/II receptor; BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) was used in all samples to block non-specific binding. Directly conjugated antibodies used in these experiments were anti-TCR-β (H57-597), anti-CD45 (30-F11), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2), anti-TNF-α (MP6-XT3) and anti-IL-4 (11B11) all from BD Pharmingen. Phycoerythrin-conjugated CD1dIg (BD Pharmingen) loaded with αGalCer was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Similar results were obtained using αGalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer (data not shown). For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were isolated from liver or spleen as described above and stained with surface markers. After washing in staining buffer, cells were fixed and permeabilized using fixation/permeabilization buffer (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by staining with Alexa647-conjugated anti-cytokine monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) or isotype control mAb. The data were collected on a BD LSR II (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA) flow cytometer and analysed using flowjo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Calculation of liver NKT-cell yield was made using CD45-gated IHL yields that were first normalized by calculating total cell yield/g liver.

Ex vivo analysis of cytokine production

Splenocytes were prepared from mice 2 hr after injection with αGalCer. After red blood cell lysis, 5 × 105 splenocytes were cultured in 1 ml RPMI-1640, 10% FCS, supplemented with sodium pyruvate, l-glutamine, non-essential amino acids and 2-mercaptoethanol for 4 hr at 37°, in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Supernatants were harvested and tested for cytokines by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Pharmingen).

Serum analysis

Serum was prepared from blood collected via cardiac puncture at various times after i.p. administration of αGalCer or vehicle control. Serum samples were frozen at −20° until cytokine measurements were performed using cytometric bead arrays (BD Pharmingen) and Bioplex (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Pulmonary function assessment to measure airway hyperresponsiveness

Twenty hours after injection with αGalCer or vehicle, mice were anaesthetized and lung function was assessed as described previously.33 Briefly, the trachea was cannulated and the mouse was connected to a volume-cycled ventilator (flexiVent; SCIREQ, Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada). Data from regular ventilation were collected to establish the baseline values for each animal. Pressure, flow and volume were used to calculate the peak responses for airway resistance (RN) after challenge with inhaled doses of saline or aerosolized methacholine (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in saline. Data are reported as ΔR (change in resistance compared to baseline).

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

Twenty hours after i.p. αGalCer injection, the lungs were flushed with 0·9% NaCl solution containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell counts were obtained using the Advia 120 Hematology System (Bayer HealthCare, Morristown, NJ). Differentials were obtained by centrifuging 2 × 104 cells onto a slide, followed by staining with the Hema3 Kit (Biochemical Sciences, Inc., Swedesboro, NJ) and scoring at least 500 cells per sample.

Histology

Lungs were collected from killed mice, inflated with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and fixed overnight at 4°. Tissues were then dehydrated in 70% ethanol, paraffin-embedded, and stained with haematoxylin & eosin (H&E) and/or periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), according to standard procedures.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

RNA was isolated by mechanically homogenizing tissue in Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Genomic DNA was digested and RNA was further purified using the PrepEase Kit (USB, Cleveland, OH). The cDNA was synthesized from 1·5 μg of RNA using random hexamer primers, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Vα14 (5′-CCACCCTGCTGGATGACACT-3′) and Jα18 (5′-CAAAATGCAGCCTCCCTAAGG-3′) specific primers were used together with a FAM/BHQ-labelled probe that spanned the Vα14/Jα18 junction (5′-ACATCTGTGTGGTGGGCGATAGAGGTTCA-3′). The amplification of the primer/probe set was validated before use to allow for use of the comparative CT method. 18S ribosomal RNA expression was used as an endogenous control (AOD; PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was run on an ABI7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). ΔCT was calculated by subtracting the average endogenous control CT from the average target CT value. Relative expression levels were determined using the formula 2(−ΔΔCT), in which ΔΔCT equals the ΔCT of an arbitrarily designated calibrator subtracted from the ΔCT obtained for the remaining samples.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post-test or Student’s t-test was used where appropriate. To test for significant differences between methacholine dose–response curves, non-linear regression analysis followed by the extra sum of squares F-test was used. In all cases, results were considered significant when P < 0·05.

Results

Strain-dependent variation in αGalCer-induced serum cytokines

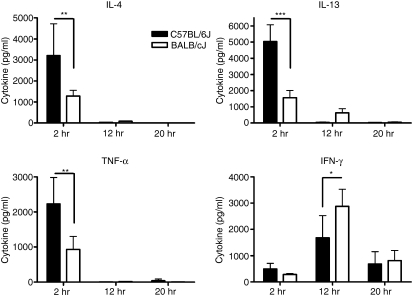

We have previously reported strain-dependent variations in αGalCer-induced serum cytokine production in a mouse model of pregnancy loss.30 To confirm that these differences did not reflect hormonal influences caused by the pregnancy, we assessed the serum cytokine production kinetics induced by αGalCer in normal age-matched C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ female mice (Fig. 1). In both strains, levels of serum TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-13 increased rapidly and were highest 2 hr after αGalCer administration. Similar to our previous observations in pregnant mice, significantly higher amounts of serum TNF-α (2231 ± 336 versus 932 ± 166 pg/ml), IL-4 (3206 ± 678 versus 1284 ± 121 pg/ml) and IL-13 (5033 ± 463 versus 1554 ± 204 pg/ml) were observed in the serum from C57BL/6J mice versus that from BALB/cJ mice 2 hr after αGalCer administration. In contrast to these three cytokines, serum IFN-γ levels rose more slowly, reaching their highest levels approximately 12 hr after αGalCer administration. Early after αGalCer administration, IFN-γ levels were slightly higher in C57BL/6J versus BALB/cJ serum (499 ± 94 versus 287 ± 17 pg/ml, respectively). Interestingly, by 12 hr, the point at which the majority of serum IFN-γ is produced by NK cells34 (data not shown), BALB/cJ levels were actually higher than in C57BL/6J mice (2881 ± 289 versus 1680 ± 377). These data confirmed, therefore, that systemic cytokine production resulting from NKT-cell activation is significantly different between these two inbred strains.

Figure 1.

Serum cytokine production in αGalCer-treated C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice. Eight-week-old female C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice were given αGalCer (100 ng/g) or vehicle only (0·05% Tween-20) intraperitoneally. Serum from blood collected at various times after injection was assayed for cytokines. Each time-point represents the mean ± SD of five mice, *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001. The data are representative of three separate experiments.

Effect of genetic background on susceptibility to NKT-mediated AHR

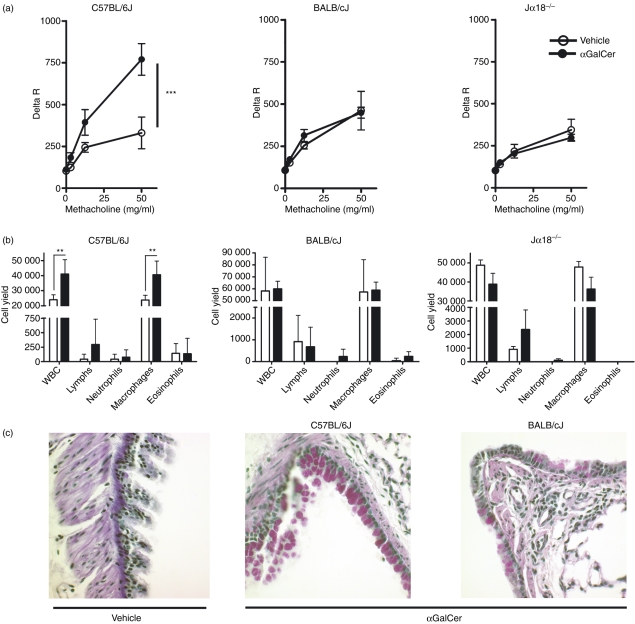

We next asked whether the observed difference in αGalCer-induced serum cytokine production predicted different physiological outcomes. NKT cells have been previously demonstrated to play a role in allergen-induced asthma in mice.35,36 In addition, direct stimulation of NKT cells with αGalCer results in AHR, a cardinal feature of asthma, in an IL-4- and IL-13-dependent manner.37 As our results demonstrated significantly higher IL-4 and IL-13 production in C57BL/6J mice than in BALB/cJ mice, we hypothesized that C57BL/6J mice would be more susceptible to αGalCer-induced AHR than BALB/cJ mice. Therefore, αGalCer was administered to age-matched and sex-matched C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice followed 20 hr later by an assessment of pulmonary function and lung pathology. As predicted, a dramatic increase in AHR was observed in C57BL/6J mice upon αGalCer treatment. However, in striking contrast, no AHR was observed in αGalCer-treated BALB/cJ mice (Fig. 2a). The αGalCer-induced AHR was NKT-cell-dependent because no AHR was observed in Jα18−/− mice crossed onto a C57BL/6J background (Fig. 2a), nor was it observed in CD1d−/− mice (data not shown). Analysis of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid revealed that, concomitant with the increased AHR observed in C57BL/6J mice, there was an increase in the numbers of leucocytes, the majority of which were macrophages (Fig. 2b). In contrast, no increases in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cells were observed in the BALB/cJ mice, Jα18−/− (Fig. 2b), or CD1d−/− mice (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Genetic background controls susceptibility to natural killer T (NKT) cell-mediated airway hyperreactivity (AHR). Eight-week-old female mice were injected with αGalCer (100 ng/g) or vehicle control intraperitoneally followed by assessment of lung function and pathology 20 hr later. (a) AHR in C57BL/6J but not BALB/cJ mice. Mice administered either αGalCer (closed circles) or vehicle control (open circles) were tested for hyperresponsiveness to methacholine. Data represent the mean ± SEM from five to nine mice per group, ***P = 0·0001. (b) Differential cell counts from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Analysis of BAL cell differentials revealed an increased number of leucocytes, primarily macrophages from C57BL/6J mice treated with αGalCer versus vehicle. No increases were observed in αGalCer-treated BALB/cJ or Jα18−/− mice. Data represent the mean ± SD from five to nine mice per group. (c) Increased periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining in lungs of αGalCer-treated C57BL/6J mice. Sections of lungs from αGalCer-treated or vehicle-treated C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice were harvested 20 hr after treatment, fixed, and PAS-stained. Data are representative of multiple sections from two C57BL/6J and two BALB/cJ mice for each treatment.

Lungs from the vehicle-treated mice and the αGalCer-treated mice were also examined histologically. Neither C57BL/6J nor BALB/cJ mice showed any overt signs of inflammation in the large airways or in the parenchyma of H&E-stained sections (data not shown). However, PAS staining revealed elevated mucus production in the C57BL/6J mouse lungs versus the lungs of the BALB/cJ mice (Fig. 2c). Both the number of PAS+ cells as well as the intensity of staining were higher in C57BL/6J mouse lung, and staining was restricted primarily to the large airways. Taken together, these data suggested that the genetic background dictated susceptibility/resistance to αGalCer-induced AHR and mucus metaplasia, two of the cardinal features of asthma, and that susceptibility was correlated with increased serum cytokine levels following activation of NKT cells.

Genetic regulation of intracellular cytokine production by NKT cells

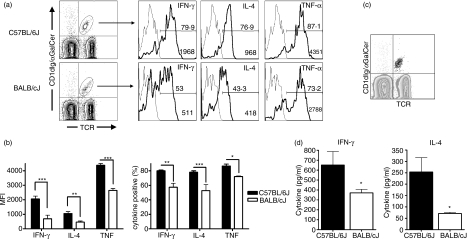

Variability in serum cytokine production after NKT-cell activation could result from variable cytokine production by NKT cells, variability in NKT-cell number, or a combination of these factors. To test the former possibility, intracellular cytokine staining was used to assess NKT-cell cytokine production of IFN-γ, IL-4 and TNF-α after αGalCer administration. Analyses were performed on freshly isolated NKT cells ex vivo, in the absence of brefeldin A or monensin. Examination 2 hr after αGalCer administration revealed that although NKT cells from both strains were positive for IFN-γ, IL-4 and TNF-α, there was a striking difference in the level of cytokine production between the two strains (Fig. 3a). While approximately 80–90% of the spleen NKT cells were producing all three cytokines in C57BL/6J mice, only approximately 50–60% of BALB/cJ spleen NKT cells were cytokine-positive (Fig. 3b). Because αGalCer-induced cytokine production at the 2-hr time-point was due exclusively to NKT cells (Fig. 3c), these data translated into an overall higher percentage of IFN-γ-, IL-4- and TNF-α-secreting cells among C57BL/6J splenocytes 2 hr after αGalCer administration (data not shown). No variability in the production of IFN-γ, IL-4 and TNF-α was observed among the CD4+ or CD4−CD8− subsets (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Strain-dependent variation in natural killer T (NKT) cell intracellular cytokine production. Eight-week-old female mice were administered αGalCer (100 ng/g) intraperitoneally. Two hours after injection, intracellular staining was used to analyse cytokine production in splenic NKT cells. (a) Intracellular cytokine expression in C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ spleen NKT cells. Splenocytes were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-T-cell receptor monoclonal antibody (mAb), phycoerythrin αGalCer-loaded CD1dIg, and Alexa647 anti-cytokine or isotype control mAbs. Histograms depict the intracellular cytokine staining of NKT cells with isotype control mAb (grey lines) or with anti-cytokine mAb (black lines). The percentage of cytokine-positive cells is indicated above the gate. The median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the NKT-gated population is depicted in the lower right corner. (b) Cumulative cytokine expression data in C57BL/6J versus BALB/cJ spleen. Data are presented as the mean MFI ± SD of the NKT-gated populations as well as the mean percent cytokine-positive NKT cells (± SD), n = 3 mice. Data are representative of five separate experiments. (c) Backgate analysis of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-producing cells after αGalCer administration reveals that NKT cells are the exclusive producers of this cytokine 2 hr after αGalCer injection. The grey contour plot depicts TCR+αGalCer-CD1dIg+ splenocytes over which is overlaid all TNF-α-producing cells (large black dots). (d) Ex vivo cytokine production by splenocytes from αGalCer-treated C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice. Splenocytes from αGalCer-treated mice were placed in short-term culture, without any additional stimulation, after which cytokines were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), n = 2 mice per strain. Data are representative of two separate experiments, *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

To confirm the intracellular cytokine staining, we conducted a separate set of experiments in which splenocytes isolated 2 hr after the administration of αGalCer i.p. were placed in culture for 4 hr, after which cytokine levels were measured by ELISA (Fig. 3c). Importantly, no additional stimulation was used during culture, which allowed the comparison ex vivo of αGalCer-induced NKT-cell cytokine production between the two strains. These data confirmed the significantly higher cytokine production by NKT cells from C57BL/6J mice compared to BALB/cJ mice after in vivo stimulation with αGalCer.

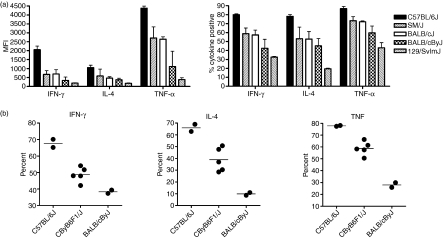

Widespread variability in NKT-cell cytokine production among different genetic backgrounds

To investigate the extent to which genetic background affects cytokine production by NKT cells, we examined NKT-cell cytokine production in a number of common inbred mouse strains 2 hr after i.p. administration of αGalCer. Interestingly, we found a wide distribution of NKT-cell cytokine production after αGalCer administration (Fig. 4a). Of the five strains analysed, C57BL/6J mice exhibited the highest levels of cytokine production upon αGalCer stimulation. Two strains, BALB/cByJ and 129/SvImJ, exhibited only limited production of cytokines upon αGalCer stimulation, while SM/J mice, like BALB/cJ, exhibited an intermediate level among the strains in the panel. To assess the inheritance pattern of the cytokine production phenotype, BALB/cByJ, C57BL/6J and CByB6/J F1 mice were treated with αGalCer and analysed 2 hr after injection. Comparison of the parental strains with the F1 progeny revealed that the NKT-cell cytokine production phenotype was neither completely dominant nor recessive as the F1 mice exhibited intermediate levels of cytokine production after αGalCer administration (Fig. 4b). These data suggested that there is widespread variability in NKT-cell cytokine production among different genetic backgrounds and that the level of NKT-cell cytokine production after αGalCer stimulation is subject to genetic control.

Figure 4.

Variation of natural killer T (NKT) cell cytokine production among different genetic backgrounds. Intracellular cytokine staining was performed on different strains of mice 2 hr after αGalCer administration using the methods described in Fig. 3. (a) Strain-dependent variation in the NKT-cell cytokine production among five different strains of mice. Cumulative cytokine expression of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-4 (IL-4) are shown. Data are presented as the mean ± SD median fluorescence intensity of the NKT-gated populations as well as the mean ± SD per cent cytokine-positive NKT cells, n = 3 mice. Significant variation among strains was observed, P < 0·0001. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (b) Inheritance pattern of NKT-cell cytokine expression. Eight-week-old female C57BL/6J, BALB/cByJ, and CByB6/J F1 mice were given αGalCer (100 ng/g) intraperitoneally. Two hours after injection, intracellular staining was used to analyse cytokine production in the spleen. Each data point represents one mouse.

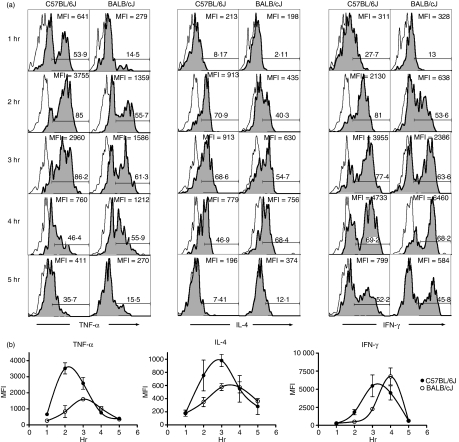

A comparison of the kinetics of intracellular cytokine production between two of the strains revealed several unexpected findings regarding the kinetics of NKT-cell cytokine production. αGalCer was administered to C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice, followed by assessment of intracellular TNF-α, IL-4 and IFN-γ production by NKT cells at various time-points after injection (Fig. 5a). First, we observed in both strains that the production of cytokines occurred in a sequential manner (Fig. 5b), such that peak production of each of the three cytokines occurred approximately 30 min apart (e.g. C57BL/6J: peak TNF-α, 2·4 hr; peak IL-4, 2·9 hr; peak IFN-γ, 3·3 hr). Second, we observed that there was indeed strain-dependent variation in the kinetics of the NKT-cell cytokine production. For each cytokine, peak production in BALB/cJ mice was delayed approximately 30 min with respect to peak production in C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Strain-dependent variation in the kinetics of intracellular cytokine production. Intracellular cytokine staining was used to assess cytokine production by natural killer T (NKT) cells at various times after αGalCer administration. (a) Representative histograms of NKT-gated splenocytes stained with isotype control monoclonal antibody (mAb; open histogram) or anti-cytokine mAb (shaded histogram) at various times after injection. The percentage of cytokine-positive NKT cells is depicted above the gate as is the MFI of the NKT-gated 2population. (b) Comparison of intracellular cytokine production kinetics between strains. The MFIs of NKT-cell intracellular tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) were plotted against time. Data represent the mean MFI ± SD of two to four mice per time-point and are representative of two independent experiments.

Finally, these analyses revealed that, at the peak of their respective responses, there was a significantly greater frequency of TNF-α-producing and IL-4-producing NKT cells in C57BL/6J versus BALB/cJ mice after αGalCer administration (Fig. 5a,b). Thus, for TNF-α and IL-4, there was a clear difference between strains in both the overall cytokine production as well as the kinetics of cytokine production. In contrast, while the frequency of IFN-γ-producing NKT cells was initially higher in C57BL/6J than in BALB/cJ mice (2-hr and 3-hr timepoints), the frequency of IFN-γ-secreting NKT cells at the peak response was actually slightly higher in BALB/cJ mice (Fig. 5b). The intracellular cytokine staining was therefore in agreement with the serum cytokine data (Fig. 1). Taken together, these data indicated the presence of widespread strain-dependent variation in both the magnitude and the kinetics of cytokine production by NKT cells in response to αGalCer.

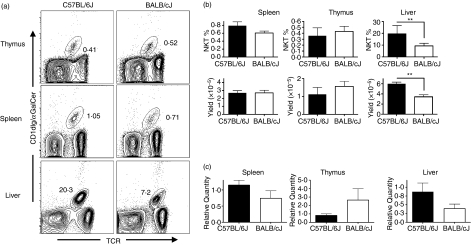

Widespread variation in liver NKT-cell numbers

Variation in NKT-cell numbers in certain autoimmune-prone strains of mice is well-documented.18 Therefore, in addition to variation in NKT-cell function, it was also possible that variation in NKT-cell frequency contributed to different amounts of serum cytokine elicited after αGalCer stimulation and so to enhanced susceptibility to αGalCer-induced AHR. To address this question, we compared the frequencies of C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ NKT cells in different organs using flow cytometry (Fig. 6a). Comparison of the frequencies and numbers of NKT cells in the thymus and spleen revealed no significant differences between the two strains (Fig. 6b). In contrast, significant differences were observed between the frequencies of NKT cells in the liver between the two strains. In C57BL/6J mice, 21% of the intrahepatic liver mononuclear cells were NKT cells compared to an average frequency of 10% in the BALB/cJ liver, which translated into a twofold difference in the number of liver NKT cells (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

Strain-dependent variation in liver natural killer T (NKT)-cell frequency. Thymus, spleen and liver cell preparations from 8-week-old female C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice were stained with phycoerythrin-Cy5 anti-CD45, fluorescein iosthiocyanate (FITC) anti-T-cell receptor (TCR), and phycoerythrin αGalCer-loaded CD1dIg. (a) Representative contour plots of NKT-cell percentages in the different organs. Data depicted are the CD45-gated subset. (b) NKT-cell percentages and yields from each organ. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, **P < 0·01, n = 3 to n = 5 mice per organ. (c) Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of invariant NKT TCR transcripts. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on cDNAs using primers and probes specific for the NKT invariant TCR-α chain. RNA levels were normalized to 18S RNA endogenous control. Amounts of normalized TCR-α transcripts is expressed as the relative quantity compared to that of C57BL/6J mice.

To confirm the calculated NKT-cell yields, we designed a quantitative reverse transcription (RT) PCR primer/probe set that would allow us to use the expression of invariant TCR-α chain as a surrogate marker for relative numbers of NKT cells. Total RNA was isolated from thymus, spleen and liver of C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice, followed by cDNA synthesis and quantitative PCR. 18S RNA gene expression was used as an endogenous control. Comparison of NKT TCR-α transcripts between C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice in the three organs revealed a pattern of expression that recapitulated the previously determined yields (Fig. 6c).

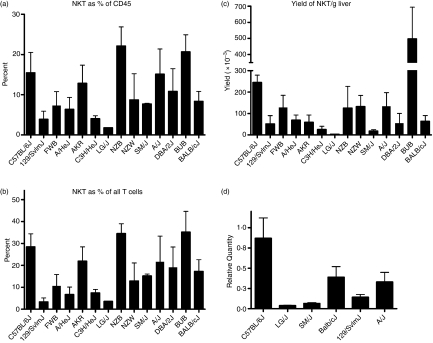

To assess the extent to which NKT-cell numbers vary among strains, we screened a panel of 14 strains of inbred mice for variation in their liver NKT-cell frequencies. While the percentage of T cells as a proportion of CD45+ leucocytes was relatively stable among all the strains (62 ± 8·8%), the percentage of liver NKT cells was highly variable (Fig. 7a). The mean percentage of IHL NKT cells among the strains was 10·8 ± 1·9%, ranging from a low of 1·8 ± 0·02% in LG/J mice to a high of 22·1 ± 2·4% in NZB/BlnJ mice. Similarly, the fraction of NKT cells that comprised the total IHL T-cell population varied (Fig. 7b), with strains such as LG/J and 129/SvImJ (3·6 ± 0·16% and 3·3 ± 1·9%, respectively), possessing only a fraction of the NKT cells found in strains such as BUB/BnJ (35·1 ± 4·2%) and NZB/BlnJ (34·5 ± 4·6%). Variability in NKT-cell percentage led, in turn, to significant variability in the number of NKT cells among the different strains (Fig. 7c). Here, a striking 140-fold range was observed among the different strains, from a low of 0·35× 105 ± 0·01 × 105 (LG/J) to 4·97 × 105 ± 0·98 × 105 (BUB/BnJ). Variability in the liver compartment was confirmed using quantitative RT-PCR to assess the relative TCR invariant α-chain transcript level in livers from selected strains (Fig. 7d). Taken together, these data suggested the presence of significant variability in the number of NKT cells in the liver IHL compartment among different genetic backgrounds.

Figure 7.

Variation in liver natural killer T (NKT) -cell frequency among different genetic backgrounds. Intrahepatic lymphocytes (IHLs) purified from a panel of 14 strains of mice, were stained and analysed by flow cytometry. NKT-cell frequencies are reported as (a) percentage of CD45+ cells, (b) percentage of TCR+ cells, and (c) yield/g liver. Data are the mean ± SD of three to five mice per strain. Significant variation was observed in both the frequency as well as the number of NKT cells, P < 0·001. (d) Widespread variability in NKT TCR-α transcript levels. Relative levels of invariant VA14 NKT TCR-α chain transcripts, used as surrogate markers of NKT-cell numbers in different organs, were assessed in the spleen, liver, and thymus from selected strains of mice by quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

Discussion

NKT cells have been implicated in a number of diseases, including autoimmune disease, infectious disease, allergen-induced asthma and atherosclerosis.1 While the exact role of NKT cells in disease susceptibility and pathogenesis is unclear in most cases, it is clear that their ability to rapidly secrete large amounts of a wide variety of cytokines is an important component of their potent activity. Variability in NKT-cell number and function might be expected, therefore, to have a dramatic impact on disease pathogenesis mediated by NKT cells, directly or indirectly, through their effects on other leucocyte subsets. Indeed, the observations made here provide an explanation for the susceptibility and resistance of C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice, respectively, to cerebral malaria which was demonstrated to be NKT-dependent,32 and are consistent with strain-dependent differences in susceptibility to encephalomyocarditis virus.16,38

Despite the variety of diseases in which NKT cells have been implicated, and in which there are known strain-dependent effects on disease susceptibility, the examination of strain-dependent variation in NKT-cell function has been largely confined to autoimmune-prone strains of mice. Our finding that C57BL/6J mice were more susceptible than BALB/cJ mice to NKT-mediated AHR corroborated a similar strain-dependent susceptibility in a model of ΝΚΤ-mediated pregnancy loss,30 as well as a model of αGalCer-induced liver injury,31 which we confirmed (data not shown). NKT-mediated AHR does differ from these two models, in which TNF-α plays a critical role in disease pathogenesis, because it is dependent on IL-4 and IL-13.35–37 However, because serum IL-4 and IL-13, as well as TNF-α, are significantly higher in C57BL/6J mice after αGalCer administration, our findings are consistent with previous reports demonstrating that administration of IL-13 systemically is sufficient to induce AHR.39,40 These observations differ from those of Meyer et al. who did not observe AHR after systemic administration of αGalCer, and who were able to demonstrate AHR in BALB/cByJ mice as well as C57BL/6J mice after intranasal administration of αGalCer.37 Their inability to observe AHR after systemic administration of αGalCer could be the result of differing routes of injection (i.p. versus intravenous), or the more sensitive techniques used here to assess pulmonary function. Similarly, an intranasal route of administration is predicted to preferentially stimulate the lung NKT-cell population, which may be present at similar frequencies in C57BL/6J and BALB/cByJ mice. While the data presented here clearly demonstrate that systemic activation of NKT cells with a potent agonist such as αGalCer is sufficient to induce AHR, additional studies will be needed to determine whether more physiological ligands such as bacterial glycosphingolipids mediate similar effects. Importantly, these data demonstrate that activation of NKT cells results in different physiological outcomes depending on the strain.

To date, investigation into links between genetic control of NKT-cell number and function and disease pathogenesis has focused on a few autoimmune-prone strains of mice. Numerous studies have confirmed the deficiency in NKT-cell number and IL-4 production in the diabetogenic NOD/Lt strain.19,21,41–43 However, while some studies have observed a link between these deficiencies and disease progression,20,24,44–47 others have not.48,49 In sharp contrast with the NOD/diabetes model, disease progression in lupus-prone NZB/W mice is correlated with elevated NKT-cell frequencies and increased NKT-cell IFN-γ production.27,50 In view of the strain-to-strain variability among ‘normal’ inbred strains of mice reported here, it is clear that deficiencies in NKT-cell number and function are not confined to autoimmune-prone strains of mice. Rather, NOD/LtJ appears to be at the lower end of a broad distribution of NKT-cell frequencies.

Variation in NKT-cell numbers appeared to be especially high in the liver, where, for reasons that are still unknown, NKT cells comprise an especially high proportion of T cells in C57BL/6J mice. Liver NKT-cell yields among strains were found to span a 140-fold range, a level of variation similar to what has been observed in the human population, in which variation in peripheral blood NKT-cell frequency has been observed to span a 100-fold range.51 Therefore, while it is generally accepted that human liver NKT cell frequencies are low, our data raise the possibility that elevated liver NKT-cell frequencies may exist in some human populations. Our data demonstrating differences between C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ liver NKT-cell frequencies differ from a previous report comparing these strains.21 Although the reason for this discrepancy is unclear, it may stem from the fact that these two strains exhibited a comparatively small difference in liver NKT numbers (approximately twofold) relative to other strains used in our study. The data reported here are supported by the large variation in liver NKT-cell numbers observed through analysis of 14 inbred strains, as well as the consistent differences in αGalCer-induced serum cytokine production and NKT-mediated disease susceptibility between C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ strains.

In addition to variability in NKT-cell numbers, variability in the NKT intracellular cytokine production appeared to be a common, heritable trait. In all strains analysed, intracellular production by NKT cells of TNF-α, IL-4 and IFN-γ was variable at the 2 hr time-point, which was consistent with the serum cytokine levels detected at this time. Interestingly, analysis of the kinetics of NKT-cell cytokine production revealed that while peak production of TNF-α and IL-4 was significantly higher in the C57BL/6J NKT cells versus BALB/cJ, peak production of IFN-γ was similar between the two strains. This was in fact consistent with the initially puzzling observation of slightly greater serum IFN-γ in BALB/cJ mice at the 12-hr time-point. Serum IFN-γ at this time after αGalCer administration has been demonstrated to be largely linked to NK cells.34 As NKT-derived IFN-γ has been demonstrated to be critical in the induction of IFN-γ production by NK cells,9,52 one might predict that similar amounts of IFN-γ production by NKT cells would lead to similar production of IFN-γ by NK cells. The reason for this disparity between the NKT IL-4 and IFN-γ production between strains is unknown, but may reflect the different requirements for optimal production of these cytokines by NKT cells.13,53 Also unknown is the reason for the distinct delay in the kinetics of peak cytokine production between C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice, which has been confirmed in other strains (data not shown). We speculate that the slower activation kinetics and lower frequency of cytokine-producing cells suggest a genetically controlled difference in the transport and/or processing of the αGalCer. Variation in the serum levels of apolipoprotein E, for example, which has recently been demonstrated to play a critical role in the transport and uptake of αGalCer,54 might be expected to affect the kinetics of NKT-cell activation. Other possibilities are differences in the relevant antigen-presenting cells which could affect the NKT-cell response,55 or polymorphisms in Slamf1 and Slamf6, members of the SLAM family of immunoreceptors, which were recently demonstrated to be critical in NKT-cell lineage commitment.56,57

This study demonstrates the presence of significant, widespread variation in both NKT-cell number and function among a number of inbred mouse strains. As the role of NKT cells in various disease models becomes clearer and as more physiological CD1d ligands are identified, it will be possible to better explore the impact of NKT-cell function in disease pathogenesis. In addition, because of their ability to influence the function of other leucocyte subsets, there is a strong possibility that variable NKT-cell function may result in altered function of downstream leucocyte populations such as dendritic cells, B cells and NK cells, which could have a significant impact on the quality of the immune response in these strains of mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Colette Charland at the UVM Flow cytometry facility, and Tim Hunter and Mary Lou Shane at the Vermont Cancer Center DNA Analysis Facility for their help in quantitative PCR measurements. We also thank Alan Chant and Cory Teuscher for helpful discussion and Daniel Barkhuff for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01AI067897 and P20RR021905 (J.E.B.) and by P20RR15557 (M.E.P.).

References

- 1.Kronenberg M. Toward an understanding of NKT cell biology: progress and paradoxes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:877–900. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–9. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brigl M, Bry L, Kent SC, Gumperz JE, Brenner MB. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1230–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanic AK, De Silva AD, Park JJ, et al. Defective presentation of the CD1d1-restricted natural Vα14Jα18 NKT lymphocyte antigen caused by beta-d-glucosylceramide synthase deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1849–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0430327100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paget C, Mallevaey T, Speak AO, et al. Activation of invariant NKT cells by toll-like receptor 9-stimulated dendritic cells requires type I interferon and charged glycosphingolipids. Immunity. 2007;27:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinjo Y, Wu D, Kim G, et al. Recognition of bacterial glycosphingolipids by natural killer T cells. Nature. 2005;434:520–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattner J, Debord KL, Ismail N, et al. Exogenous and endogenous glycolipid antigens activate NKT cells during microbial infections. Nature. 2005;434:525–9. doi: 10.1038/nature03408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sriram V, Du W, Gervay-Hague J, Brutkiewicz RR. Cell wall glycosphingolipids of Sphingomonas paucimobilis are CD1d-specific ligands for NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1692–701. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carnaud C, Lee D, Donnars O, Park SH, Beavis A, Koezuka Y, Bendelac A. Cutting edge: cross-talk between cells of the innate immune system: NKT cells rapidly activate NK cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:4647–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eberl G, MacDonald HR. Selective induction of NK cell proliferation and cytotoxicity by activated NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:985–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(200004)30:4<985::AID-IMMU985>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galli G, Nuti S, Tavarini S, Galli-Stampino L, De Lalla C, Casorati G, Dellabona P, Abrignani S. Innate immune responses support adaptive immunity: NKT cells induce B cell activation. Vaccine. 2003;21(Suppl. 2):S48–54. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitamura H, Ohta A, Sekimoto M, et al. α-Galactosylceramide induces early B-cell activation through IL-4 production by NKT cells. Cell Immunol. 2000;199:37–42. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitamura H, Iwakabe K, Yahata T, et al. The natural killer T (NKT) cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide demonstrates its immunopotentiating effect by inducing interleukin (IL)- 12 production by dendritic cells and IL-12 receptor expression on NKT cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1121–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshimoto T, Paul WE. CD4pos, NK1.1pos T cells promptly produce interleukin 4 in response to in vivo challenge with anti-CD3. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1285–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smyth MJ, Crowe NY, Pellicci DG, Kyparissoudis K, Kelly JM, Takeda K, Yagita H, Godfrey DI. Sequential production of interferon-gamma by NK1.1(+) T cells and natural killer cells is essential for the antimetastatic effect of alpha-galactosylceramide. Blood. 2002;99:1259–66. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Exley MA, Bigley NJ, Cheng O, et al. Innate immune response to encephalomyocarditis virus infection mediated by CD1d. Immunology. 2003;110:519–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2003.01779.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein-Streilein J, Sonoda KH, Faunce D, Zhang-Hoover J. Regulation of adaptive immune responses by innate cells expressing NK markers and antigen-transporting macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:488–94. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan MA, Fletcher J, Baxter AG. Genetic control of NKT cell numbers. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:276–84. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baxter AG, Kinder SJ, Hammond KJ, Scollay R, Godfrey DI. Association between alphabetaTCR+CD4–CD8– T-cell deficiency and IDDM in NOD/Lt mice. Diabetes. 1997;46:572–82. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.4.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammond KJ, Poulton LD, Palmisano LJ, Silveira PA, Godfrey DI, Baxter AG. alpha/beta-T cell receptor (TCR)+CD4–CD8– (NKT) thymocytes prevent insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in nonobese diabetic (NOD)/Lt mice by the influence of interleukin (IL)-4 and/or IL-10. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1047–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammond KJ, Pellicci DG, Poulton LD, Naidenko OV, Scalzo AA, Baxter AG, Godfrey DI. CD1d-restricted NKT cells: an interstrain comparison. J Immunol. 2001;167:1164–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong S, Wilson MT, Serizawa I, et al. The natural killer T-cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide prevents autoimmune diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2001;7:1052–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naumov YN, Bahjat KS, Gausling R, et al. Activation of CD1d-restricted T cells protects NOD mice from developing diabetes by regulating dendritic cell subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;13:13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251531798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi FD, Flodstrom M, Balasa B, Kim SH, Van Gunst K, Strominger JL, Wilson SB, Sarvetnick N. Germ line deletion of the CD1 locus exacerbates diabetes in the NOD mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6777–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121169698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh AK, Wilson MT, Hong S, et al. Natural killer T cell activation protects mice against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1801–11. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyamoto K, Miyake S, Yamamura T. A synthetic glycolipid prevents autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing TH2 bias of natural killer T cells. Nature. 2001;413:531–4. doi: 10.1038/35097097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forestier C, Molano A, Im JS, et al. Expansion and hyperactivity of CD1d-restricted NKT cells during the progression of systemic lupus erythematosus in (New Zealand Black × New Zealand White)F1 mice. J Immunol. 2005;175:763–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh AK, Yang JQ, Parekh VV, Wei J, Wang CR, Joyce S, Singh RR, Van Kaer L. The natural killer T cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide prevents or promotes pristane-induced lupus in mice. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1143–54. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kojo S, Adachi Y, Keino H, Taniguchi M, Sumida T. Dysfunction of T cell receptor AV24AJ18 +, BV11 + double-negative regulatory natural killer T cells in autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1127–38. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1127::AID-ANR194>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyson JE, Nagarkatti N, Nizam L, Exley MA, Strominger JL. Gestation stage-dependent mechanisms of invariant natural killer T cell-mediated pregnancy loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4580–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511025103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biburger M, Tiegs G. Alpha-galactosylceramide-induced liver injury in mice is mediated by TNF-alpha but independent of Kupffer cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:1540–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansen DS, Siomos MA, Buckingham L, Scalzo AA, Schofield L. Regulation of murine cerebral malaria pathogenesis by CD1d-restricted NKT cells and the natural killer complex. Immunity. 2003;18:391–402. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paveglio SA, Allard J, Mayette J, Whittaker LA, Juncadella I, Anguita J, Poynter ME. The tick salivary protein, Salp15, inhibits the development of experimental asthma. J Immunol. 2007;178:7064–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuda JL, Gapin L, Baron JL, Sidobre S, Stetson DB, Mohrs M, Locksley RM, Kronenberg M. Mouse V alpha 14i natural killer T cells are resistant to cytokine polarization in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8395–400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332805100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akbari O, Stock P, Meyer E, et al. Essential role of NKT cells producing IL-4 and IL-13 in the development of allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity. Nat Med. 2003;9:582–8. doi: 10.1038/nm851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lisbonne M, Diem S, de Castro Keller A, et al. Cutting edge: invariant V alpha 14 NKT cells are required for allergen-induced airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in an experimental asthma model. J Immunol. 2003;171:1637–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer EH, Goya S, Akbari O, et al. Glycolipid activation of invariant T cell receptor+ NK T cells is sufficient to induce airway hyperreactivity independent of conventional CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2782–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510282103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Exley MA, Bigley NJ, Cheng O, et al. CD1d-reactive T-cell activation leads to amelioration of disease caused by diabetogenic encephalomyocarditis virus. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:713–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, Donaldson DD. Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science. 1998;282:2258–61. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grunig G, Warnock M, Wakil AE, et al. Requirement for IL-13 independently of IL-4 in experimental asthma. Science. 1998;282:2261–3. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Godfrey DI, Kinder SJ, Silvera P, Baxter AG. Flow cytometric study of T cell development in NOD mice reveals a deficiency in alphabetaTCR+CDR–CD8– thymocytes. J Autoimmun. 1997;10:279–85. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1997.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Y, Bao M, Yoon JW. Intrinsic defects in the T-cell lineage results in natural killer T-cell deficiency and the development of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Diabetes. 2001;50:2691–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poulton LD, Smyth MJ, Hawke CG, Silveira P, Shepherd D, Naidenko OV, Godfrey DI, Baxter AG. Cytometric and functional analyses of NK and NKT cell deficiencies in NOD mice. Int Immunol. 2001;13:887–96. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.7.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Esteban LM, Tsoutsman T, Jordan MA, et al. Genetic control of NKT cell numbers maps to major diabetes and lupus loci. J Immunol. 2003;171:2873–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Falcone M, Facciotti F, Ghidoli N, et al. Up-regulation of CD1d expression restores the immunoregulatory function of NKT cells and prevents autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2004;172:5908–16. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.5908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson SB, Kent SC, Horton HF, Hill AA, Bollyky PL, Hafler DA, Strominger JL, Byrne MC. Multiple differences in gene expression in regulatory Valpha 24Jalpha Q T cells from identical twins discordant for type I diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7411–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120161297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen YG, Driver JP, Silveira PA, Serreze DV. Subcongenic analysis of genetic basis for impaired development of invariant NKT cells in NOD mice. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:705–12. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsuki N, Stanic AK, Embers ME, Van Kaer L, Morel L, Joyce S. Genetic dissection of V alpha 14J alpha 18 natural T cell number and function in autoimmune-prone mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:5429–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rocha-Campos AC, Melki R, Zhu R, Deruytter N, Damotte D, Dy M, Herbelin A, Garchon HJ. Genetic and functional analysis of the Nkt1 locus using congenic NOD mice: improved Valpha14-NKT cell performance but failure to protect against type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55:1163–70. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeng D, Liu Y, Sidobre S, Kronenberg M, Strober S. Activation of natural killer T cells in NZB/W mice induces Th1-type immune responses exacerbating lupus. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1211–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI17165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee PT, Putnam A, Benlagha K, Teyton L, Gottlieb PA, Bendelac A. Testing the NKT cell hypothesis of human IDDM pathogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:793–800. doi: 10.1172/JCI15832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wesley JD, Robbins SH, Sidobre S, Kronenberg M, Terrizzi S, Brossay L. Cutting edge: IFN-gamma signaling to macrophages is required for optimal Valpha14i NK T/NK cell cross-talk. J Immunol. 2005;174:3864–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.3864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayakawa Y, Takeda K, Yagita H, Van Kaer L, Saiki I, Okumura K. Differential regulation of Th1 and Th2 functions of NKT cells by CD28 and CD40 costimulatory pathways. J Immunol. 2001;166:6012–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.6012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van den Elzen P, Garg S, Leon L, et al. Apolipoprotein-mediated pathways of lipid antigen presentation. Nature. 2005;437:906–10. doi: 10.1038/nature04001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bezbradica JS, Stanic AK, Matsuki N, et al. Distinct roles of dendritic cells and B cells in Vα14Jα18 natural T cell activation in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;174:4696–705. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Griewank K, Borowski C, Rietdijk S, et al. Homotypic interactions mediated by slamf1 and slamf6 receptors control NKT cell lineage development. Immunity. 2007;27:751–62. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jordan MA, Fletcher JM, Pellicci D, Baxter AG. Slamf1, the NKT cell control gene Nkt1. J Immunol. 2007;178:1618–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]