Abstract

To identify common variants influencing body mass index (BMI), we analyzed genome-wide association data from 16,876 individuals of European descent. After previously reported variants in FTO, the strongest association signal (rs17782313, P = 2.9 × 10−6) mapped 188 kb downstream of MC4R (melanocortin-4 receptor), mutations of which are the leading cause of monogenic severe childhood-onset obesity. We confirmed the BMI association in 60,352 adults (per-allele effect = 0.05 Z-score units; P = 2.8 × 10−15) and 5,988 children aged 7–11 (0.13 Z-score units; P = 1.5 × 10−8). In case-control analyses (n = 10,583), the odds for severe childhood obesity reached 1.30 (P = 8.0 × 10−11). Furthermore, we observed overtransmission of the risk allele to obese offspring in 660 families (P (pedigree disequilibrium test average; PDT-avg) = 2.4 × 10−4). The SNP location and patterns of phenotypic associations are consistent with effects mediated through altered MC4R function. Our findings establish that common variants near MC4R influence fat mass, weight and obesity risk at the population level and reinforce the need for large-scale data integration to identify variants influencing continuous biomedical traits.

Although BMI is highly heritable, progress in identifying specific variants involved in regulating weight has largely been confined to rare mutations causing severe, early-onset monogenic forms of obesity1-6. Recently, the FTO gene was identified as the first locus harboring common variants with an unequivocal impact on obesity predisposition and fat mass at the population level7-9. To increase power to detect additional common variants associated with these traits, and to improve our understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible, we carried out a large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data available for 16,876 individuals phenotyped for adult BMI.

Meta-analysis, under an additive model, of data from four European population-based studies (n = 11,012) and three disease-case series (n = 5,864), all genotyped genotyped on the Affymetrix GeneChip 500K array (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note online), demonstrated that FTO variants had the strongest association with BMI (for example, rs1121980: beta = 0.060 (95% CI = 0.039–0.082) Z-score units (that is, log10-transformed BMI, standardized by gender and age, per-allele); P = 3.6 × 10−8) (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note online). Among the nine remaining signals with P < 10−5 (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 online), we focused our initial attention on a cluster of associated SNPs on chromosome 18q21 for which the most significant association resides at rs17782313 (P = 2.9 × 10−6).

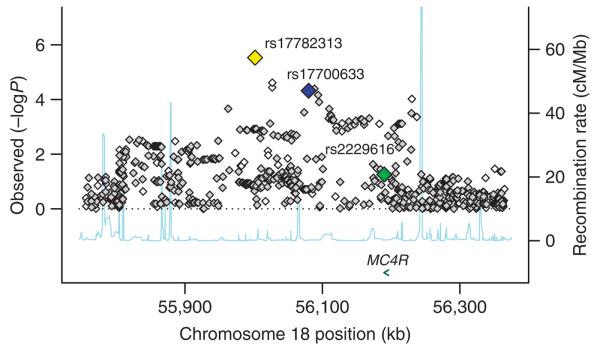

This region seemed to contain at least two independent association signals (rs17782313 and rs17700633: minor allele frequencies 24% and 30% respectively; Supplementary Table 3 online) with low pair-wise linkage disequilibrium (LD; r2 = 0.08, D′ = 0.33 in CEU HapMap) mapping 109–188 kb from the coding sequence of MC4R (Fig. 1). MC4R represents a compelling biological candidate, as rare coding mutations in the gene are the leading cause of monogenic obesity in humans10.

Figure 1.

Regional plot of chromosome 18q21 (55,700–56,400 kb), showing the association signals for obesity for the meta-analysis of all 16,876 samples with genome-wide association scans. On the x axis is chromosomal position in kilobases (as NCBI build 35 coordinates), and on the y axis is the P value for association (expressed as −log10 P value). The imputed data signals are shown in gray diamonds and the directly genotyped signals in white. Estimated recombination rates (taken from HapMap) are plotted (light blue) to reflect the local LD structure around the associated SNP. Gene annotations were taken from the University of California Santa Cruz genome browser. The yellow diamond corresponds to the directly genotyped SNP in this region, which shows the strongest association with obesity (rs17782313, P = 2.9 × 10−6), the lower blue diamond represents the result from rs17700633 (P = 4.8 × 10−5, directly genotyped), and the green diamond represents the result from rs2229616 (or V103I, P = 0.056, imputed). LD structure across the interval, as calculated by D′, and r2 measures are shown in Supplementary Figure 5a.

Association analysis of imputed genotype data11, based on 16,876 samples from the seven populations, for untyped HapMap SNPs across the region (55.7–56.4 Mb NCBI build 35) showed that rs17782313 has the strongest association overall and that there were no other (imputed or directly genotyped) SNPs with markedly stronger association than either rs17782313 or rs17700633 (Fig. 1). Analyses of LD relationships, as well as haplotypic and conditional analyses, established that these associations were not secondary to previously reported associations with the V103I and I251L coding variants, of which the (rare) minor alleles are weakly protective for obesity at the population level12-14 (Supplementary Note). Several lines of evidence indicated that our association was unlikely to reflect latent population substructure (Supplementary Note). Consequently, we focused follow-up efforts on these two SNPs, seeking evidence for replication in 60,352 samples with measures of adult BMI.

First, we genotyped both SNPs in ten adult population-based studies (combined n = 40,717) and three disease-case series (n = 3,757) (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note) of individuals all of European descent. Across all 44,474 individuals, rs17782313 was strongly associated with BMI (combined per-allele effect = 0.049 (95% CI = 0.033–0.065) Z-score units, P = 1.3 × 10−9; Supplementary Fig. 4a online), with less marked evidence for replication at rs17700633 (0.025 (0.011–0.040) Z-score units, P = 0.0007; Supplementary Fig. 4b).

Second, we obtained additional genotypes from six population-based studies (n = 13,240) and two disease-case series (n = 2,638), all individuals of European origin undergoing genome-wide association analysis within the Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits (GIANT) Consortium (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note). In these 15,878 individuals, rs17782313 was again associated with BMI (combined per-allele effect = 0.035 (0.006–0.063) Z-score units, P = 0.02; Supplementary Fig. 4c), with comparable effect size and evidence for replication at rs17700633 (0.041 (0.015–0.067) Z-score units, P = 0.002; Supplementary Fig. 4d).

Combining data across all 77,228 genotyped adults, we found that each copy of the rs17782313 C allele was associated with a difference in BMI of 0.049 (0.037–0.061) Z-score units (P = 2.8 × 10−15; Fig. 2 and Table 1), equivalent to ~0.22 kg m−2. Evidence for association at rs17700633 was weaker (0.033 (0.022–0.045) Z-score units or ~0.15 kg m−2; P = 4.6 × 10−9) (Supplementary Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 4 online). Although initial assessment based on LD patterns from the HapMap had suggested that the effect at rs17700633 was independent of that at rs17782313, conditional analysis conducted on our data show that the effect of the former is substantially attenuated and no longer reaches a strong degree of statistical significance (P = 0.002 for rs17700633 after conditioning on rs17782313; Supplementary Fig. 4f,g and Supplementary Note). We did not find any evidence for a significant difference in effect size (P = 0.11) between men (0.058 (0.041–0.076) Z-score units) and women (0.039 (0.022–0.055)) at rs17782313 (Supplementary Fig. 4h,i).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis plot showing the rs17782313[C] per-allele effect size on BMI in 77,228 adults, expressed in log10BMI sex-specific Z-score units.

Table 1. Association between rs17782313 and BMI in populations with genome-wide association data andin replication populations.

| MAF (%) | T/T | C/T | C/C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| n | Mean BMIa (95% CI) |

Mean BMIa (95% CI) |

Mean BMIa (95% CI) |

P b | ||

| GWA population-based studies | ||||||

| EPIC-Obesity study | 2,416 | 24 | 26.0 (25.9–26.2) |

26.3 (26.1–26.5) |

26.5 (26.0–27.1) |

0.029 |

| CoLaus | 5,631 | 24 | 25.4 (25.3–25.6) |

25.6 (25.4–25.8) |

25.8 (25.3–26.3) |

0.016 |

| British 1958 Birth Cohort | 1,479 | 23 | 26.9 (26.6–27.2) |

27.2 (26.8–27.6) |

28.0 (26.8–29.2) |

0.017 |

| WTCCC/UK Blood Services 1 | 1,456 | 24 | 25.7 (25.5–26.0) |

26.1 (25.7–26.4) |

26.3 (25.4–27.1) |

0.08 |

| Replication population-based studies | ||||||

| EPIC-Norfolk | 15,834 | 23 | 26.0 (25.9–26.0) |

26.1 (26.0–26.2) |

26.3 (26.1–26.5) |

0.0006 |

| MRC-Ely | 1,696 | 25 | 26.8 (26.6–27.1) |

26.9 (26.7–27.3) |

26.6 (25.8–27.4) |

0.95 |

| Northern Finnish Birth Cohort of 1966 | 4,830 | 18 | 24.3 (24.2–24.5) |

24.5 (24.3–24.7) |

24.9 (24.2–25.5) |

0.034 |

| Oxford Biobank | 1,165 | 24 | 25.6 (25.3–25.9) |

26.0 (25.6–26.4) |

26.7 (25.7–27.7) |

0.018 |

| UK Blood Services 2 | 1,562 | 24 | 25.9 (25.6–26.1) |

25.9 (25.6–26.2) |

26.4 (25.6–27.3) |

0.34 |

| ALSPAC Mothers | 6,264 | 24 | 22.7 (22.6–22.8) |

22.7 (22.6–22.9) |

22.9 (22.6–23.3) |

0.19 |

| Hertfordshire study | 2,842 | 24 | 26.9 (26.7–27.1) |

27.3 (27.1–27.5) |

27.2 (26.6–27.8) |

0.03 |

| SardiNIA | 1,412 | 12 | 24.5 (24.2–24.9) |

24.7 (24.1–25.3) |

23.4 (21.7–25.2) |

0.11 |

| KORA | 1,642 | 26 | 26.9 (26.6–27.1) |

27.2 (26.9–27.5) |

27.6 (26.9–28.3) |

0.02 |

| NHS | 2,265 | 24 | 24.6 (24.4–24.8) |

25.1 (24.8–25.4) |

24.1 (23.5–24.8) |

0.24 |

| PLCO | 2,238 | 24 | 27.2 (27.0–27.4) |

27.2 (27.0–27.5) |

28.0 (27.3–28.7) |

0.11 |

| Dundee controls 1 | 1,913 | 22 | 26.2 (26.0–26.5) |

26.4 (26.1–26.7) |

27.0 (26.1–27.9) |

0.11 |

| Dundee controls 2 | 1,501 | 22 | 26.5 (26.2–26.8) |

26.8 (26.4–27.2) |

26.5 (25.6–27.5) |

0.35 |

| EFSOCH | 1,639 | 23 | 24.6 (24.3–24.8) |

25.3 (24.9–25.6) |

25.9 (25.0–26.8) |

0.00004 |

| DGI controls | 1,503 | 22 | 26.3 (26.1–26.6) |

26.6 (26.3–26.9) |

26.3 (25.5–27.2) |

0.35 |

| FUSION controls | 1,291 | 19 | 26.8 (26.5–27.0) |

26.8 (26.4–27.2) |

26.4 (25.5–27.3) |

0.58 |

| Meta-analyses of population-based studies (I2 = 2.5%, P for heterogeneity = 0.43) | 1.6 × 10−15 | |||||

| GWA case series | ||||||

| WTCCC/T2D cases | 1,923 | 26 | 30.6 (30.3–31.0) |

30.7 (30.3–31.1) |

30.8 (29.9–31.8) |

0.69 |

| WTCCC/CAD cases | 1,974 | 25 | 27.3 (27.1–27.6) |

27.2 (26.9–27.5) |

27.7 (27.0–28.5) |

0.76 |

| WTCCC/HT cases | 1,947 | 23 | 27.0 (26.8–27.2) |

27.6 (27.3–27.9) |

27.5 (26.8–28.3) |

0.004 |

| Replication case series | ||||||

| Dundee cases 1 | 1,909 | 24 | 30.9 (30.6–31.3) |

30.9 (30.5–31.3) |

31.7 (30.6–32.8) |

0.68 |

| Dundee cases 2 | 1,067 | 24 | 31.0 (30.6–31.5) |

31.5 (30.9–32.1) |

31.3 (29.9–32.7) |

0.29 |

| YT2D–OXGN cases | 617 | 25 | 31.4 (30.7–32.1) |

31.7 (30.9–32.5) |

31.4 (29.3–33.6) |

0.71 |

| DGI cases | 1,543 | 23 | 28.3 (28.0–28.6) |

28.0 (27.7–28.4) |

28.0 (27.1–29.0) |

0.26 |

| FUSION cases | 1,094 | 18 | 29.8 (29.4–30.1) |

30.1 (29.6–30.6) |

29.0 (27.4–30.7) |

0.86 |

| Meta-analyses of case series (I2 = 20%, P for heterogeneity = 0.27) | 0.11 | |||||

| Meta-analyses of all studies (I2 = 15%, P for heterogeneity = 0.24) | 2.8 × 10−15 | |||||

BMI is presented as geometric means and log-inverse 95% confidence intervals.

P values represent significance of the additive model (per-allele effect) with standardized log10-transformed BMI, adjusted for age.

The C allele at rs17782313 was positively associated with adult height (per-allele effect = 0.030 (0.018–0.042) Z-score units; P = 8.7 × 10−7; equivalent to ~0.21 cm) (Supplementary Fig. 4j). Consequently, the association with weight was even stronger than that with BMI (per-allele effect for rs17782313[C] = 0.059 (0.047–0.071) Z-score units, P = 2.8 × 10−21; equivalent to ~760 g), indicating that rs17782313 influences overall adult size (Supplementary Fig. 4k). Across the 77,228 adult samples, rs17782313 was associated with an ~8% per-allele increase in the odds of being overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg m−2; ORoverweight = 1.08 (1.05–1.11), P = 1.6 × 10−9) and ~12% of being obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg m−2; ORobesity = 1.12 (1.08–1.16), P = 5.2 × 10−9) (Supplementary Fig. 4l,m). In a separate obesity case-control study of 2,766 French adults (Supplementary Table 1), there was a 31% per-allele increase in the odds of being morbidly obese (BMI ≥ 40 kg m−2; ORmorbid-obesity = 1.31 (1.15–1.49), P = 5.6 × 10−5).

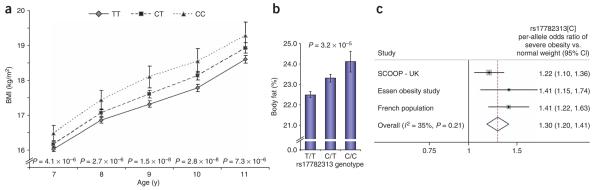

To understand the effect of rs17782313 on regulation of weight in early life, we first examined 5,988 children from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (Supplementary Table 1). There was no association with birth weight or weight up to 42 months (Supplementary Table 5 online). However, in children aged 7–11 y, each additional copy of rs17782313[C] was associated with a BMI difference of between 0.10 and 0.13 Z-score units (P < 7.3 × 10−6) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5), twice that observed in adults (P = 0.001). In these children, the association with BMI was mediated exclusively through an effect on weight, with no detectable effect on height (Supplementary Table 5). Body composition data for 5,281 9-year-old children showed that genotype-associated differences in weight and BMI reflected disproportionate effects on fat mass (per-allele effect of rs17782313[C] on percentage body fat = 0.10 (0.05–0.14) Z-score units, P = 3.0 × 10−5; Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 3.

Effects of rs17782313 on regulation of weight in early life. (a) Longitudinal data for BMI at age 7–11 for children in the ALSPAC study by rs17782313 genotypes. Mean values represented as geometric means and back-transformed 95% confidence intervals. P values represent significance of the additive model (per-allele effect) of log10-transformed data, adjusted for sex. (b) Association between rs17782313 and body fat percentage in 9-year-old children from the ALSPAC study. Mean values represented as geometric means and back-transformed 95% confidence intervals. P values represent significance of the additive model (per-allele effect) of log10-transformed data, adjusted for sex. (c) Meta-analysis plot showing the rs17782313[C] per-allele effect size on risk of severe obesity in childhood and adolescence in 10,583 children from three studies.

These findings were confirmed in three case-control studies of children and adolescents with severe early-onset obesity (Supplementary Note, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). In each, rs17782313 was associated with a significant increase in the risk of extreme obesity: the combined estimate of the OR was 1.30 (1.20–1.41; P = 8.0 × 10−11; Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1). In 660 nuclear families, ascertained through children or adolescents with extreme obesity (BMI > 95th percentile), there was a significant overtransmission of the C allele to the obese offspring (56% transmission rate, PDT-avg = 2.42 × 10−4), providing further evidence that the association does not reflect population stratification (Supplementary Note, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

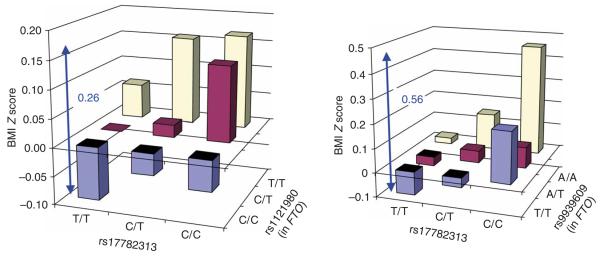

Common variants near MC4R and FTO seem to have additive effects on BMI (Fig. 4). When comparing individuals with no risk alleles at either locus (19% of the population) with those homozygous at both (1%), the point estimate of the BMI difference amounts to 0.26 Z-score units (or ~1.17 kg m−2) in adults and 0.56 Z-score units in children.

Figure 4.

Association between the combined rs17782313 and FTO genotypes and BMI in adults (EPIC-Norfolk, n = 15,622) and children (ALSPAC age 7 years, n = 5,779). BMI is expressed in log10BMI Z-score units adjusted for age (in adults) and sex. Both SNPs have a significant additive effect on BMI in adults (rs17782313, P = 4.0 × 10−4; rs1121980, P = 2.0 × 10−14) and in children (rs17782313, P = 8.0 × 10−6; rs9939609, P = 7.6 × 10−5).

Having observed convincing BMI and obesity associations in both adults and children, we next sought refinement of the association signal through meta-analyses of genotyped and imputed data and analysis of LD patterns (Supplementary Fig. 5a online) across 1 Mb of flanking sequence (including the coding region of MC4R itself). In contrast to the original analysis of all seven studies (Fig. 1), the meta-analysis restricted to the four population-based studies (Supplementary Fig. 5b) identified three SNPs (rs12955983, rs718475, rs9956279) that had association signals of comparable or stronger magnitude to rs17700633 and rs17782313. When we extended this meta-analysis to include data on all 32,301 individuals with available regional data (Supplementary Fig. 5c), only rs718475 and rs9956279 showed more significant association results compared to rs17700633 and rs17782313. However, direct genotyping of these SNPs, as well as conditional analysis, showed that these estimates of association were inflated and indicated that rs17782313 remains the most significantly associated variant for which imputed or typed data are currently available (Supplementary Note). Our findings cannot be explained by previously reported associations at rare variants such as V103I and I251L, which have only modest allelic association with rs17782313 (r2 = 0.001; D′ = 0.48 and r2 = 0.001; D′ = 0.49, respectively; Supplementary Note). Comprehensive resequencing and fine mapping will be required to unambiguously identify the causal variants, although these probably lie within a 190-kb recombination interval between the coding sequences of PMAIP1 and MC4R (Supplementary Fig. 5a). PMAIP1, encoding the protein Noxa, is a putative HIF1A (hypoxia-inducible factor, alpha)-regulated proapoptotic gene15 and a relatively unlikely candidate for a role in weight regulation. In contrast, humans with rare functional mutations in MC4R sequence are known to develop severe early-onset obesity16, and analogous phenotypes are seen in murine models of Mc4r disruption17. This strong biological candidacy points to disruption of the transcriptional control of MC4R as the likely functional mechanism, even though the associated variants lie 109–188 kb downstream of the MC4R coding sequence. Low or absent MC4R expression in available expression QTL datasets (derived from lymphocytes18-20 and cerebral cortex21) precluded efforts to obtain evidence for cis-transcriptional phenotypes associated with rs17782313 or other nearby SNPs. There was no evidence for cis effects between any of the SNPs within this interval and expression of PMAIP1 in lymphocytes (refs. 18-20 and E.T.D., unpublished data) or cerebral cortex21.

In the absence of direct functional evidence relating these variants to MC4R expression, we asked whether they recapitulated phenotypic patterns characteristic of rare, severe coding mutations in MC4R. These include early-onset obesity, increases in lean mass and bone mineral density and enhanced linear growth16. The rs17782313-related associations with adult height clearly indicate an impact on linear growth and are consistent with the phenotype seen in rare, severe coding mutations in MC4R. Furthermore, the disproportionate BMI effect size in children (as compared to adults) is also consistent with the early-onset obesity characteristic of rare MC4R mutations. Neither such effect was observed for variants at FTO8. Children carrying the C allele at rs17782313 had modest increases in lean and bone mass, although these were similar to those observed for variants at FTO (Fig. 3, Supplementary Note and Supplementary Table 6 online).

These findings have implications for ongoing efforts to identify variants influencing common continuous traits such as weight and BMI. First, as with variants in FTO, common variants near MC4R make only a modest contribution to overall variance (~0.14% for adult BMI, and ~0.26% for fat mass at age 9). Of the other eight signals emerging from our meta-analysis of 16,876 individuals, there was clear evidence of replication of the SNP within FTO in additional (n > 34,000) samples, whereas SNPs rs10498767 (chromosome 6; replication P = 0.009; meta-analysis P = 2.3 × 10−5) and rs748192 (chromosome 3; replication P = 0.05; meta-analysis P = 2.9 × 10−5) showed some nominal evidence of replication; these signals, in particular, will benefit from further replication studies to establish their contribution to obesity-related phenotypes (Supplementary Table 7 online). Second, our finding provides a powerful example of overlap in the genetic determinants of monogenic and multifactorial forms of the same condition. Third, as with recent findings in diseases such as prostate cancer22 and type 2 diabetes23-26, our study suggests that variants mapping tens or hundreds of kilobases from adjacent coding sequence can have convincing phenotypic effects, presumably via remote effects on expression or translation. Finally, primary identification of these signals involved analysis of genome-wide association data from over 16,000 individuals, with further confirmation and initial characterization of the locus using over 90,000 samples. Although more substantial influences on weight and BMI may have been overlooked as a result of the incomplete coverage offered by contemporary genotyping arrays, especially for structural and low frequency variants, this study illustrates the scale of the endeavor that will be required for detection of additional variants influencing traits such as these.

METHODS

Genome-wide association samples

Five of the seven genome-wide scan studies were part of the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (WTCCC) and have been described previously26: the type 2 diabetes (WTCCC-T2D, n = 1,924), hypertension (WTCCC-HT, n = 1,952) and coronary artery disease (WTCCC-CAD, n = 1,988) case samples, and the UK Blood Service (WTCCC-UKBS, n = 1,485) and British 1958 Birth Cohort (WTCCC-BC58, n = 1,479) controls. The EPIC Obesity study comprises a representative sample (n = 2,566) nested within the EPIC-Norfolk Study27, a population-based cohort study of 25,663 men and women of European descent aged 39–79 y recruited in Norfolk, UK between 1993 and 1997. Of these, 2,415 were included in the analyses. The CoLaus study28 is a cross-sectional study of a random sample of 6,188 extensively phenotyped European men and women, aged 35–75 y, living in Lausanne, Switzerland, of whom 5,633 were included in the analyses. Height and weight were measured using standard anthropometric techniques in all studies, except for WTCCC-CAD and WTCCC-UKBS, for which height and weight were self reported. Basic descriptive characteristics for all genome-wide association studies are presented in Supplementary Table 1. All participants gave written informed consent, and project protocols were approved by the appropriate research ethics committees (Supplementary Note).

Genome-wide SNP genotyping and quality control

All seven genome-wide association (GWA) studies were genotyped using Affymetrix GeneChip 500K array set. Genotypes were called using the CHIAMO genotype calling software26 for all studies, apart from the EPIC-Obesity and CoLauS studies, for which the BRLMM algorithm was used. Here, we report 359,062 SNPs that passed quality control in all four population-based studies (EPIC-Obesity, British 1958 Birth Cohort, CoLaus and UK Blood Services) and 344,883 SNPs that passed quality control in all seven (four population-based plus three case-series studies, WTCCC-HT, WTCCC-T2D and WTCCC-CAD). Each study had applied genotyping quality control criteria and done tests for population stratification: correction for population substructure was done by principal components in the CoLaus cohort (Supplementary Note). Each study had excluded individuals with evidence of non-European ancestry on the basis of genome-wide association data (for example, through multidimensional scaling)26. The genomic inflation factor (λ) of each GWA study ranged from 1.009 to 1.024, indicating that the extent of residual population substructure is modest (Supplementary Fig. 3). In addition, none of the markers recently shown to be informative for geographical origin in the UK26 associated with BMI (all P > 0.01). Additional details are available in Supplementary Note.

Replication genotyping

Initial replication of rs17782313 and rs17700633 was done in 13 collections (n = 44,474) for which DNA was available for genotyping (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note). We also sought replication in 18,878 individuals from eight additional samples for which rs17782313 and rs17700633 genotypes were available as part of ongoing GWA studies (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note). Further, we genotyped rs17782313 in samples from a French adult obesity case-control study (n = 2,766), from the Essen Obesity Family study (n = 2,280) and in three samples informative for childhood or adolescent BMI (n = 9,654). Genotypes for a fourth study of childhood BMI (Essen Obesity Study, n = 929) were available from their genome-wide association data. In total, 59,174 individuals were directly genotyped, and 16,807 individuals provided genotypes from their respective GWA scans (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note). Of the former, 37,819 samples were genotyped using TaqMan SNP genotyping assay (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and 21,355 were genotyped by KBiosciences using a fluorescence-based competitive allele-specific PCR (KASPar). Duplicates were assayed with >99% concordance rates. Of the nine samples providing genotypes from genome-wide association data, five (SardiNIA, KORA, DGI T2D cases, DGI controls and Essen Obesity Study) were genotyped on the Affymetrix GeneChip 500K, and four were genotyped on the HumanHap300 (FUSION T2D cases, FUSION controls and PLCO), HumanHap240 (also PLCO) or HumanHap550 (NHS) Illumina arrays. As rs17782313 and rs17700633 were not present on the Illumina platforms, unobserved genotypes were imputed with high accuracy (predicted r2 ≥ 0.89) using MACH. Of the SardiNIA population, 1,412 individuals were genotyped for the Affymetrix GeneChip 500K; the remaining individuals were genotyped with the Affymetrix Mapping 100K array, and these marker data were used to impute genotypes at SNPs in the ‘500K’ set for the remaining 2,893 individuals not typed with this technology9,29. Residual relatedness in the SardiNIA and FUSION samples was dealt with statistically (see below). Overall call rates across studies averaged 98.1%, and there were no departures from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P > 0.01 in each study) (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Note). Informed consent and ethical approval was obtained for all studies. Additional details are available in Supplementary Note.

Genome-wide association analyses and meta-analyses

BMI was log10-transformed and standardized to Z scores before analyses. EPIC-Obesity, British BC58 and CoLaus calculated sex- and age-specific Z scores, and WTCCC-UKBS, WTCCC-T2D, WTCCC-HT and WTCCC-CAD used sex-specific Z scores, adjusting for age in the analyses. Each GWA study performed linear regression (additive model) to test for association between each SNP and BMI Z score using PLINK (WTCCC-T2D, WTCCC-UKBS, WTCCC-CAD, CoLauS), SAS/Genetics 9.1 (EPIC-Obesity Study), STATA 8.1 (British 1958 BC) or R (WTCCC-HT). Subsequently, summary statistics of the SNP-BMI associations of each GWA study were combined in meta-analyses using the inverse variance–weighted method with a fixed-effects model30. Meta-analyses were done by combining the four population-based studies (EPIC-Obesity, British 1958 BC, CoLaus and WTCCC/UKBS) as well as all seven GWA studies. Variants that showed marked evidence of heterogeneity (P < 0.10) across the studies were not considered for replication. Meta-analyses were done with SAS 9.1. The overall results of the meta-analysis were visualized using PLINK (Supplementary Fig. 2), and the top hits from our scan and the replication data are presented in Supplementary Table 2. Additional details are available Supplementary Note.

Replication in adult population-based studies and case series and meta-analyses

Replication analyses were also based on sex-specific log10BMI Z scores, using linear regression (additive model) while adjusting for age (and other appropriate covariates such as ‘center’). Analyses were also done with BMI log10-transformed (but not standardized) for presentation of geometric means and 95% CIs (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 4). For relevant analyses, height was standardized to sex-specific Z scores, whereas weight was log10-transformed before standardizing. Again, association was tested using linear regression assuming an additive model, adjusted for age and other appropriate covariates. Case-control analyses (for obesity and over-weight) within population-based samples were done by comparing overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg m−2) and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg m−2) to normal-weight (BMI < 25 kg m−2) individuals. Logistic regression was used to test for association between genotype and overweight/obesity, adjusted for age and sex. Similar methods were used to test for association with case status in the French adult obesity case-control study. All analyses were also done for men and women separately. In samples featuring appreciable numbers of individuals with significant degrees of relatedness (SardiNIA, FUSION), residual kinship was accounted for using a score test as previously described29. Analyses were done in Stata/s.e.m. 9.2 for Windows, PLINK, SPSS 14.1 software and SAS/Genetics 9.1. The summary statistics (beta (or OR) and s.e.m. (or 95% CI)) for each of the separate studies were combined in meta-analyses using the inverse variance–weighted method assuming a fixed-effects model, conducted in SAS 9.1. To provide approximate effect-size estimates expressed in BMI units (kg m−2), we translated from the Z-score unit differences using the s.d. of raw BMI (a mean s.d. of 4.5 kg m−2 in the population-based cohorts). This method was also applied to provide approximate effect size estimates for reporting height (mean s.d. of 7 cm) and weight (mean s.d. of 13.4 kg) data. Conditional analyses were done to investigate the dependencies between the BMI effects at rs17782313 and rs17700633: we tested for association between rs17700633 and BMI (sex-specific log10-transformed), while adjusting for age and rs17782313 (and vice versa). Summary statistics were, as before, meta-analyzed using the inverse variance–weighted method with Stata 9.2.

Analyses in childhood studies

The population-based ALSPAC study was used to test for association between rs17782313 and measures of anthropometry and body composition. Weight and height during the first 42 months of life were expressed as SDS relative to British 1990 scales. Birth weight was standardized by sex and gestational age. BMI and weight between age 7 and 11, as well as body fat percentage, DXA fat mass, DXA lean mass and DXA bone mass at age 9 were log10-transformed, whereas height remained untransformed before calculation of sex-specific Z scores. Linear regression (additive model) was used to test for association between rs17782313 genotypes and these anthropometric measures. Analyses were done in Stata/s.e.m. 9.2 for Windows. In the three childhood or adolescent case-control series, we used logistic regression to test for association with severe obesity. Although the three studies used slightly different definitions of severe obesity (3 s.d. above population mean and age of onset < 10 y in SCOOP-UK, BMI > 95th percentile in the Essen Obesity study, and BMI ≥ 97th percentile in the French Childhood Obesity study), there was no detectable heterogeneity between the estimates derived, and the summary statistics (ORs and 95% CIs) of each study were combined in meta-analyses as described above. In a separate set of 660 nuclear families of the Essen Obesity Family study, we used a pedigree transmission disequilibrium test (PDT average) to test for overtransmission of the rs17782313 C allele to the obese offspring. In addition, we determined genotype relative risks (GRR), which are robust against deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Additional consortium authors are as follows:

The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial: Kevin B Jacobs, Stephen J Chanock & Richard B Hayes

KORA: Claudia Lamina, Christian Gieger, Thomas Illig, Thomas Meitinger & H-Erich Wichmann

Nurses' Health Study: Peter Kraft, Susan E Hankinson, David J Hunter & Frank B Hu

Diabetes Genetics Initiative: Helen N Lyon, Benjamin F Voight, Martin Ridderstrale & Leif Groop

The SardiNIA Study: Paul Scheet, Serena Sanna, Goncalo R Abecasis, Giuseppe Albai, Ramaiah Nagaraja & David Schlessinger

FUSION: Anne U Jackson, Jaakko Tuomilehto, Francis S Collins, Michael Boehnke & Karen L Mohlke

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge support of the UK Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, Diabetes UK, Cancer Research United Kingdom, BDA Research, UK National Health Service Research and Development, the European Commission, the Academy of Finland, the British Heart Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, GlaxoSmithKline and the German National Genome Research Net. Personal support was provided by NIDDK (E.K.S., H.N.L., J.N.H., F.S.C.), the Wellcome Trust (A.T.H., E.Z.), Diabetes UK (R.M.F.), the Throne-Holst Foundation (C.M.L.), the Vandervell Foundation (M.N.W.), American Diabetes Association (C.J.W.), Unilever Corporate Research (S.L.) and the British Heart foundation (N.J.S).

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare competing financial interests: details accompany the full-text HTML version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/naturegenetics/.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/ reprintsandpermissions

Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.

References

- 1.Jackson RS, et al. Obesity and impaired prohormone processing associated with mutations in the human prohormone convertase 1 gene. Nat. Genet. 1997;16:303–306. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montague CT, et al. Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature. 1997;387:903–908. doi: 10.1038/43185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clement K, et al. A mutation in the human leptin receptor gene causes obesity and pituitary dysfunction. Nature. 1998;392:398–401. doi: 10.1038/32911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krude H, et al. Severe early-onset obesity, adrenal insufficiency and red hair pigmentation caused by POMC mutations in humans. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:155–157. doi: 10.1038/509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaisse C, Clement K, Guy-Grand B, Froguel P. A frameshift mutation in human MC4R is associated with a dominant form of obesity. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:113–114. doi: 10.1038/2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeo GSH, et al. A frameshift mutation in MC4R associated with dominantly inherited human obesity. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:111–112. doi: 10.1038/2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frayling TM, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316:889–894. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dina C, et al. Variation in FTO contributes to childhood obesity and severe adult obesity. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:724–726. doi: 10.1038/ng2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scuteri A, et al. Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farooqi IS, et al. Dominant and recessive inheritance of morbid obesity associated with melanocortin 4 receptor deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:271–279. doi: 10.1172/JCI9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young EH, et al. The V103I polymorphism of the MC4R gene and obesity: population based studies and meta-analysis of 29,563 individuals. Int. J. Obes. 2007;31:1437–1441. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stutzmann F, et al. Non-synonymous polymorphisms in melanocortin-4 receptor protect against obesity: the two facets of a Janus obesity gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:1837–1844. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geller F, et al. Melanocortin 4 receptor gene variant I103 is negatively associated with obesity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74:572–581. doi: 10.1086/382490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JY, Ahn HJ, Ryu JH, Suk K, Park JH. BH3-only protein Noxa is a mediator of hypoxic cell death induced by hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:113–124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farooqi IS, et al. Clinical spectrum of obesity and mutations in the melanocortin 4 receptor gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1085–1095. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huszar D, et al. Targeted disruption of the melanocortin-4 receptor results in obesity in mice. Cell. 1997;88:131–141. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon AL, et al. A genome-wide association study of global gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1202–1207. doi: 10.1038/ng2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stranger BE, et al. Population genomics of human gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1217–1224. doi: 10.1038/ng2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goring HHH, et al. Discovery of expression QTLs using large-scale transcriptional profiling in human lymphocytes. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1208–1216. doi: 10.1038/ng2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers AJ, et al. A survey of genetic human cortical gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1494–1499. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gudmundsson J, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a second prostate cancer susceptibility variant at 8q24. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:631–637. doi: 10.1038/ng1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeggini E, et al. Replication of genome-wide association signals in UK samples reveals risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Science. 2007;316:1336–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.1142364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott LJ, et al. A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science. 2007;316:1341–1345. doi: 10.1126/science.1142382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diabetes Genetics Initiative of Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Lund University and Novartis Institutes of BioMedical Research et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science. 2007;316:1331–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.1142358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Day NE, et al. EPIC-Norfolk: study design and characteristics of the cohort. European Prospective Investigation of Cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 1999;80:95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vollenweider P, et al. Health examination survey of the Lausanne population: first results of the CoLaus study. Rev. Med. Suisse. 2006;2:2528–2530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen WM, Abecasis G. Family-based association tests for genomewide association scans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:913–926. doi: 10.1086/521580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutton A, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F. Methods for Meta-Analysis in Medical Research. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.