Abstract

A high frequency of nonhomologous recombination has hampered gene targeting approaches in the model apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. To address whether the nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway could be disrupted in this obligate intracellular parasite, putative KU proteins were identified and a predicted KU80 gene was deleted. The efficiency of gene targeting via double-crossover homologous recombination at several genetic loci was found to be greater than 97% of the total transformants in KU80 knockouts. Gene replacement efficiency was markedly increased (300- to 400-fold) in KU80 knockouts compared to wild-type strains. Target DNA flanks of only ∼500 bp were found to be sufficient for efficient gene replacements in KU80 knockouts. KU80 knockouts stably retained a normal growth rate in vitro and the high virulence phenotype of type I strains but exhibited an increased sensitivity to double-strand DNA breaks induced by treatment with phleomycin or γ-irradiation. Collectively, these results revealed that a significant KU-dependent NHEJ DNA repair pathway is present in Toxoplasma gondii. Integration essentially occurs only at the homologous targeted sites in the KU80 knockout background, making this genetic background an efficient host for gene targeting to speed postgenome functional analysis and genetic dissection of parasite biology.

Toxoplasma gondii is a widespread obligate intracellular protozoan pathogen of virtually all warm-blooded animals and commonly infects humans worldwide. Due to a significant menu of established experimental approaches, T. gondii has become a model for the study of closely related disease-causing parasites (Plasmodium, Theileria, and Cryptosporidium species) belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa (32) and a model for the study of intracellular pathogens (33). Unfortunately, a high frequency of nonhomologous recombination arising from a previously undetermined double-strand break (DSB) DNA repair pathway(s) has hampered gene targeting approaches in this model.

DSB repair in most eukaryotes occurs primarily via two different recombination pathways (27). The homologous recombination pathways repair a DSB using mechanisms that recognize highly homologous DNA sequences, while the nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway does not rely on DNA sequence homology. Instead, NHEJ involves direct ligation of the ends of broken DNA strands. KU70 and KU80 proteins form a heterodimer that tightly binds the DNA ends at the DSB, an early and essential step of NHEJ (49, 50). In addition to KU70 and KU80 proteins, NHEJ is mediated by the DNA ligase IV-Xrcc4 complex and the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit or other functionally equivalent protein complexes (49).

Many eukaryotes preferentially use the NHEJ pathway to repair a DSB, and exogenous targeting DNA can be integrated anywhere into the genome independent of DNA sequence homology (27). The NHEJ pathway also appears to be preferentially used by Toxoplasma gondii based on the high rates of nonhomologous recombination and low gene targeting frequencies observed experimentally (7, 15, 26, 45). It is interesting that in contrast to the prevalence of the NHEJ pathway in eukaryotes, no functional NHEJ pathway has previously been reported in any protozoan parasite. Kinetoplastids, including Trypanosoma and Leishmania species, naturally exhibit extremely efficient homologous recombination of exogenous DNA (5, 12). While kinetoplastids possess the KU70 and KU80 components of the NHEJ pathway, recent evidence suggests that the NHEJ pathway is functionally absent (1, 24), although KU proteins do participate in telomere maintenance in Trypanosoma brucei (4, 30). Plasmodium species lack identifiable genes encoding key components of the NHEJ pathway and also exhibit a high frequency of homologous recombination (21, 51).

While most fungal organisms exhibit a low or modest gene targeting frequency, homologous recombination dominates at essentially a 100% frequency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (22), making this budding yeast a significant model organism. Recent studies have reported that much higher frequencies of gene targeting are observed in mutants of Aspergillus niger (39), Cryptococcus neoformans (25), Kluyveromyces lactis (35), Neurospora crassa (29, 41), and other fungal organisms that have been engineered to be deficient in NHEJ. NHEJ-deficient fungal strains have greatly accelerated the development of genome-wide knockouts (3, 11).

It was previously unknown whether a high frequency of nonhomologous recombination in T. gondii was due to KU-dependent NHEJ or arose from other potential mechanisms of DSB repair. In this report KU80 is found to be an essential component of a functional NHEJ pathway. KU80 knockouts now allow the efficient targeting of gene replacements, gene knockouts, and gene “knock-ins” in Toxoplasma gondii.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primers.

All oligonucleotide primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Plasmid constructs.

Plasmids were based on pCR4-TOPO (Invitrogen), except for plasmid pC4HX1-1, which was based on a pET41 vector (20).

Plasmid pmin31-X2-4(-) was constructed from plasmid pminCAT/HX (6, 7), in which the CAT gene was replaced with the coding region for cytosine deaminase (CD) (14) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Plasmid pΔKU80HXFCD was constructed by fusing, in order, a ∼5.2-kb 5′ KU80 target DNA flank from plasmid pAN442, the HXGPRT cassette (forward orientation) obtained from plasmid pmin31-X2-4(-), a 4.8-kb 3′ KU80 target flank from plasmid pPN111, and a downstream CD-negative selectable marker (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The 5′ and 3′ KU80 target flanks in plasmid pΔKU80HXFCD surround a ∼4-kb deletion of the KU80 gene (2 kb 5′ untranslated region [UTR], exon 1, intron 1, and exon 2).

Plasmid pΔKU80B was based on plasmid pΔKU80HXFCD, in which the HXGPRT marker and part of the 5′ and 3′ target flanks were deleted by digestion with BamHI. Plasmid pΔKU80B contains 3.3-kb (5′) and 2.4-kb (3′) KU80 target flanks that surround an ∼8-kb deletion of the KU80 gene (5′ UTR and all coding exons).

Plasmid pΔKU80TKFCD was based on plasmid pΔKU80HXFCD, in which NheI was used to further delete the KU80 target flanks to 1.4 kb (5′) and 0.9 kb (3′) and join (forward orientation) the DHFRTKTS marker obtained from pDHFRTKTS (13).

Plasmid pΔUPNC was constructed by PCR to join a 1.1-kb UPRT 5′ target and a 0.67-kb 3′ UPRT target flank that surrounded a deletion of the UPRT coding region. The 5′ and 3′ UPRT target flanks in plasmid pΔUPNC surround a ∼4.4-kb deletion of the UPRT gene that deletes 0.9 kb of 5′ UTR and the first six exons of UPRT.

Plasmid pΔUPT-HXB was constructed from plasmid pΔUPNC by inserting the HXGPRT marker in the forward orientation between the 5′ and 3′ UPRT target flanks. Plasmid pΔUPT-HXS was identical, except the 3′ UPRT target flank was 0.54 kb.

Plasmid pC4HX1-1 was constructed from plasmid pC4 (20), which contains the coding CPSII cDNA under the control of authentic CPSII 5′ and 3′ UTR, by adding the 1.95-kb HXGPRT marker in the forward orientation downstream of the CPSII 3′ UTR.

Plasmids of the pHXH-series were constructed by PCR (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and products were cloned into pCR4-TOPO. Plasmids pHXH-0, pHXH-50, pHXH-120, pHXH-230, pHXH-450, pHXH-620, and pHXH-910 contained the 1.5-kb HXGPRT SalI fragment (containing the last 89 codons of HXGPRT plus 3′ UTR) surrounded by 0, ∼50-bp flanks, ∼120-bp flanks, ∼230-bp flanks, ∼450-bp flanks, ∼620-bp flanks, and ∼910-bp target DNA flanks, respectively. All pHXH series plasmids were oriented in the forward orientation relative to a unique PmeI site in pCR4-TOPO.

Strains and culture conditions.

The parental strains of Toxoplasma gondii used in this study were RH (46) and RHΔhxgprt (6). A list of strains used in this study is shown in Table 1. Parasites were maintained by serial passage in diploid human foreskin fibroblasts at 36°C (15).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Parent | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RH | RH(ERP) | Wild type | 44, 46 |

| RHΔhxgprt | RH | Δhxgprt | 6 |

| RHΔku80::HXGPRT | RHΔhxgprt | Δku80::HXGPRT | This study |

| RHΔhxgprtΔku80::DHFRTKTS | RHΔku80::HXGPRT | ΔhxgprtΔku80::DHFRTKTS | This study |

| RHΔku80Δhxgprt | RHΔku80::HXGPRT | Δku80Δhxgprt | This study |

| RHΔku80 | RHΔku80Δhxgprt | Δku80 | This study |

| RHΔku80Δuprt::HXGPRT | RHΔku80Δhxgprt | Δku80Δuprt::HXGPRT | This study |

| RHΔku80ΔuprtΔhxgprt | RHΔku80Δuprt::HXGPRT | Δku80ΔuprtΔhxgprt | This study |

| RHΔku80ΔcpsII::CPSIIcDNAHXGPRT | RHΔku80Δhxgprt | Δku80ΔcpsII::CPSIIcDNAHXGPRT | This study |

Genomic DNA isolation and PCR.

Genomic DNA purifications used the DNA Blood minikit (Qiagen). PCR products were amplified using a mixture (1:1) of Taq DNA polymerase and Expand long template PCR reagent (Roche). Real-time PCR used various concentrations of parasite DNA (1, 10, 100, 1,000, and 10,000 pg) amplified (in triplicate) with either the T. gondii B1 gene primer pairs B1F and B1R at 10 pM of each primer per reaction mixture (34) or using a primer pair specific to KU80 (primers Ku80RTF and Ku80RTR). Amplification was performed by real-time fluorogenic PCR (Cepheid Smart Cycler) using one lyophilized SMartMix bead (SMartMix HM; Cepheid) per mixture. Each reaction mixture contained 1:20,000 SYBR Green I (Cambrex Bioscience). Parasite genome equivalents were determined by extrapolation from a standard curve using RHΔhxgprt DNA.

Transformation of Toxoplasma gondii and knockout verification strategy.

Electroporations (using a model BTX600 electroporator) were performed in 0.4 ml electroporation buffer containing 1.33 × 107 freshly isolated tachyzoites and 15 μg of DNA (10, 31). In gene replacement experiments the targeting plasmid was linearized 5′ of the 5′ target DNA flank. Following selection of parasite clones, the genotype of clones was determined by PCR to measure (i) loss of the deleted coding region of the targeted gene, (ii) correct targeted 5′ integration, (iii) correct targeted 3′ integration, and (iv) the presence of a target DNA flank. DNA sequence analysis and real-time PCR were also used for verification of knockouts.

KU80 knockouts.

Strain RHΔku80::HXGPRT was constructed from RHΔhxgprt by integration of the HXGPRT marker using plasmid pΔKU80HXFCD. Following transfection of tachyzoites with plasmid pΔKU80HXFCD, parasites were selected in mycophenolic acid (MPA; 25 μg/ml) and xanthine (50 μg/ml) (6). Negative selection experiments used flucytosine (5FC; 50 μM) (14). Parasite clones were isolated by limiting dilution (15). Verification of disruption of the KU80 locus with the HXGPRT marker was performed by PCR with five sets of primers: PCR 1 used D801F and D801R, PCR 2 used EX801F and EX801R, PCR 3 used HXDF1 and HXDR2, PCR 4 used 80RTF and 80RTR, and PCR 5 used CDXF1 and CDXR2. The spontaneous reversion frequency of strain RHΔku80::HXGPRT was measured in 6-thioxanthine (6TX; 200 μg/ml) (43). Strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt was constructed by targeted deletion of the HXGPRT marker using plasmid pΔKU80B and 6TX selection. Verification of removal of the HXGPRT marker from the KU80 locus was performed by PCR with four sets of primers: PCR 2 used EX801F and EX801R, PCR 3 used HXDF1 and HXDR2, PCR 6 used EX80F2 and EX80R2, and PCR 7 used 80F15 and 80RCX3.

Determination of gene replacement frequencies and statistical analysis.

PFU assays were used to determine absolute numbers of PFU that developed under different selection conditions, and then a formula was applied to calculate the gene replacement frequency (GRF) at the targeted locus. Four replicate PFU flasks were prepared for each titration point and each selection condition. A Student t test analysis was used to calculate the standard error of the mean.

Gene replacement at the KU80 locus.

Strain RHΔhxgprtΔku80::DHFRTKTS was constructed from strain RHΔku80::HXGPRT by integration of the DHFRTKTS marker using plasmid pΔKU80TKFCD. Following transfection of tachyzoites with plasmid pΔKU80TKFCD, parasite clones were selected in pyrimethamine (PYR; 1 μM). Verification of replacement of the HXGPRT marker in the KU80 locus with the DHFRTKTS marker was performed by PCR with six sets of primers: PCR 1 used HXDF1 and HXDR2, PCR 2 used EX80F2 and EX80R2, PCR 3 used EX80F3 and EX80R3, PCR 4 used TKXF1 and TKXR2, PCR 5 used CDXF1 and CDXR2, and PCR 6 used 80FCX3 and 80RCX3. PFU assays were performed at 15 days after transfection to determine the GRF based on the fraction of parasites with dual resistance to PYR (1 μM) and 6TX compared to parasites with resistance only to PYR.

Gene replacement at the UPRT locus.

Strain RHΔku80Δuprt::HXGPRT was constructed from RHΔku80Δhxgprt by targeted integration of the HXGPRT marker using plasmid pΔUPT-HXS or pΔUPT-HXB. Following transfection with plasmid pΔUPT-HXS or plasmid pΔUPT-HXB, parasites were selected in MPA and then cloned. Verification of disruption of the UPRT locus was performed by PCR with four sets of primers: PCR 1 used DUPRF1 and DUPRR1, PCR 2 used UPNF1 and UPNXR1, PCR 3 used 3′DHFRCXF and 3′CXPMUPR15′, and PCR 4 used 5′UPNCXF and 5′DHFRCXR. PFU assays were performed at various times after transfection to determine the GRF based on the fraction of parasites that had dual resistance to MPA and 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (FUDR; 5 μM) compared to the fraction of parasites that were resistant only to MPA. Strain RHΔku80ΔuprtΔhxgprt was constructed by targeted deletion of the HXGPRT marker using plasmid pΔUPNC. Following transfection with plasmid pΔUPNC, parasites were continuously selected in 6TX. Validation PCRs used primer pairs 3′DHFRCXF with 3′CXPMUPR1 and CLUPF1 with 3′CXPMUPR1.

Gene replacement at the CPSII locus.

Strain RHΔku80ΔcpsII::CPSIIcDNAHXGPRT was constructed from RHΔku80Δhxgprt by integration of the HXGPRT marker using plasmid pC4HX1-1. Verification of deletion of the endogenous CPSII locus and replacement with a functional CPSII cDNA was performed by PCR with four sets of primers: PCR 1 used CPSDF1 and CPSDR1, PCR 2 used CPSEXF1 and CPSEXR1, PCR 3 used CPSCXF1 and CPSCXR1, and PCR 4 used 3′DHFRCXF and CPSCXR2.

Chromosomal repair of Δhxgprt.

Strain RHΔku80 was constructed from RHΔku80Δhxgprt by repair of the Δhxgprt chromosomal locus using pHXH plasmids with various lengths of homologous DNA that flanked a 1.5-kb SalI fragment which had been deleted in the Δhxgprt background (6). Verification of chromosomal repair of HXGPRT was performed by PCR with primers HXF1200 and HXDR2. The frequency of chromosomal repair events at the HXGPRT locus was determined in PFU assays in a single 150-cm2 flask of human foreskin fibroblast cells with MPA selection following transfection. Each pHXH series plasmid was transfected in five independent repair experiments, and the mean PFU was determined. The percent maximal homologous recombination at the HXGPRT locus was then calculated based on comparison to results from the pHXH-910 plasmid, which carried the longest target DNA flanks. The fraction of tachyzoites surviving transfection was measured in each transfection experiment in a PFU assay. Plasmid pHXH-620 was used to determine the percent maximal homologous recombination as a function of DNA concentration or conformation.

Parasite growth rate.

Tachyzoite growth rate was determined by scoring 50 randomly selected vacuoles as previously described (15).

Sensitivity to chemical mutagens and phleomycin.

Sensitivity to N-nitroso-N-ethylurea (ENU; Sigma) was determined by treatment of replicating intracellular parasites using previously described methods (44). Etoposide (Sigma) sensitivity was determined by continuous treatment of infected monolayers in PFU assays as previously described (47). Sensitivity to the antibiotic phleomycin (Sigma) was determined on extracellular parasites as previously described (38), except PFU assays were used rather than uracil incorporation to measure viability. Parasite viability experiments with ENU, etoposide, and phleomycin were performed twice.

Sensitivity to γ-irradiation.

Sensitivity to γ-irradiation was determined by treatment of tachyzoites with various doses of ionizing radiation that were generated in a 2,000-Ci JL Shepard cesium (Cs137 gamma) irradiator. PFU assays were used to determine the surviving fraction of treated parasites relative to untreated controls. Parasite survival experiments involving γ-irradiation were performed twice.

Virulence assays.

Adult 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Labs and mice were maintained in Tecniplast Seal Safe mouse cages on vent racks at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (Lebanon, NH) mouse facility. All mice were cared for and handled according to the Animal Care and Use Program of Dartmouth College using National Institutes of Health-approved institutional animal care and use committee guidelines. Groups of four mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.2 ml (200 tachyzoites) and mice were then monitored daily for degree of illness and survival. Virulence assays were performed twice.

RESULTS

Generation of T. gondii strains RHΔku80::HXGPRT and RHΔku80Δhxgprt.

To look for potential components of the NHEJ pathway in T. gondii the ToxoDB genome database (http://www.toxodb.org/toxo/; release 3.0) was scanned for potential KU70 and KU80 proteins. BLASTp analysis of the KU70 (mus51) and KU80 (mus52) proteins of Neurospora crassa identified T. gondii homologs encoded by genes at loci 50.m03211 and 583.m05492, respectively (alignments are shown in Fig. S1 and Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

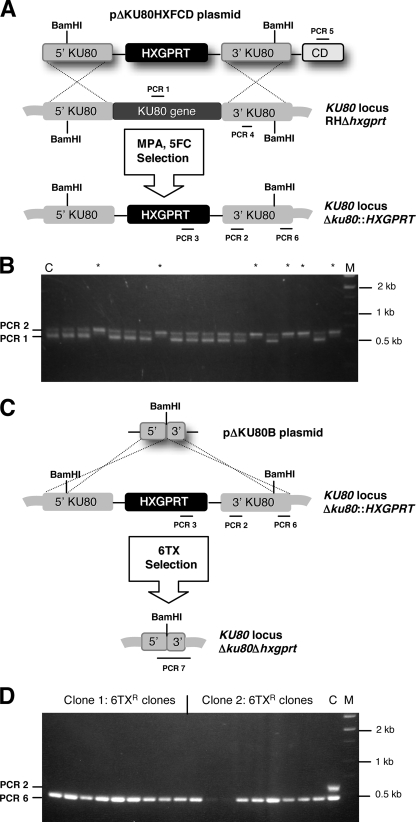

Circular or linearized plasmid pΔKU80HXFCD was transfected into strain RHΔhxgprt and parasites were selected in MPA (Fig. 1A). Transfection with circular plasmids produced no KU80 knockouts (0/36 [data not shown]), while transfections with linearized plasmids produced 11/36 clones that showed a correct PCR 2 product but no detectable PCR 1 product that corresponded to the deleted region and identified KU80-disrupted clones (Fig. 1B). Real-time PCR analysis (PCR 4) of KU80 gene copy number indicated that ∼82% of the KU80-disrupted clones contained a single copy of the KU80 3′ target DNA (Fig. 1A and B). In KU80-disrupted clones, PCR 3 was positive (presence of HXGPRT marker) and PCR 5 was negative (absence of the CD marker) (data not shown). These results suggested that the HXGPRT marker was inserted into a correctly disrupted KU80 locus (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Construction of T. gondii strains in which KU80 is disrupted. (A) Strategy for disrupting the KU80 gene via integration of the HXGPRT marker into strain RHΔhxgprt. Targeting plasmid pΔKUHXFCD targets a ∼4-kb deletion of the KU80 gene (see Materials and Methods). Parasites were selected by positive selection in MPA plus xanthine or by negative selection against the downstream cytosine deaminase (CD) marker in MPA plus xanthine plus flucytosine. Approximate locations of PCR products using primer pairs to verify genotype are depicted (not to scale). The parental strain RHΔhxgprt was positive for PCR 1 (538-bp product) and PCR 2 (639-bp product). A targeted KU80 knockout was positive for the PCR 2 product and was negative for the PCR 1 product. (B) A representative panel of 18 MPA-resistant clones obtained after transfection of plasmid pΔKU80HXFCD and selection in MPA. Clones marked with a * show a pattern consistent with targeted deletion of a region of the KU80 gene (see text). (C) Cleanup of the KU80 locus. The HXGPRT marker was removed from the KU80 locus using the strategy depicted with negative selection in 6TX after transfection of strain RHΔku80::HXGPRT with plasmid pΔKU80B. Approximate locations of PCR products using primer pairs to verify genotype are depicted (not to scale). The parental strain RHΔku80::HXGPRT was positive for PCR 2 (639-bp product) and PCR 6 (373-bp product) and a plasmid pΔKU80B-retargeted KU80 knockout was positive for PCR 6 and was negative for PCR 2. (D) 6TX-resistant clones uniformly had the genotype Δku80 Δhxgprt.

A downstream CD marker on plasmid pΔKU80HXFCD was tested in a negative selection strategy using 5FC to enrich for the desired KU80 knockouts (Fig. 1A). Transfected parasites were initially selected in MPA for 10 days, then were cloned in MPA plus 5FC to counterselect against the downstream CD gene (Fig. 1A). We observed that six of six analyzed clones were KU80 knockouts (data not shown).

To recover the HXGPRT marker from the KU80 locus, clones of strain RHΔku80::HXGPRT were transfected with plasmid pΔKU80B (Fig. 1C) and nine 6TX-resistant clones were obtained from each transfection. Each 6TX-resistant clone had the genotype Δku80Δhxgprt (Fig. 1D), based on the presence of correct product from PCR 6 and the absence of any product from PCR 2 (Fig. 1C and D). PCR 3 also revealed the expected loss of the HXGPRT marker, and PCR 7 produced a correct product (∼2.9 kb) showing targeted integration of the 3′ target DNA flank (data not shown).

Growth, virulence, and sensitivity of T. gondii strains RHΔhxgprt, RHΔku80::HXGPRT, and RHΔku80Δhxgprt to DNA damaging agents.

Disruption of KU70 or KU80 typically induces an increased sensitivity to DNA damaging agents, particularly to agents that cause double-strand DNA breaks (25, 35, 39). Tachyzoite growth rate, sensitivity to ENU, and sensitivity to etoposide were unchanged between strains RHΔku80::HXGPRT and RHΔku80Δhxgprt compared to RHΔhxgprt or RH (data not shown). The higher virulence of type I strains was also retained in the KU80 knockout mutants (Fig. 2A). In contrast, phleomycin treatments of 5 μg/ml or 50 μg/ml reduced parental RHΔhxgprt viability to 56% (±16%) and 2.1% (0.9%), reduced strain RHΔku80::HXGPRT viability to 19% (±8%) and 0.19% (±0.05%), and reduced strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt viability to 14% (±3%) and 0.23% (±0.02%), respectively (Fig. 2B). KU80 knockouts were 2.9- to 4.0-fold more sensitive to 5 μg/ml and 9- to 11-fold more sensitive to 50 μg/ml phleomycin treatment than the parental strains. Sensitivity to γ-irradiation was also significantly increased in KU80 knockouts. At a dose of 35 Gy, the percent parasite viability of strain RHΔhxgprt was 5.4% (±1.1%), viability of strain RHΔku80::HXGPRT was 0.013% (±0.005%), and viability of strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt was 0.010% (±0.003%) (Fig. 2C). KU80 knockouts were between 415- and 540-fold more sensitive to γ-irradiation (35-Gy dose) than the parental strains.

FIG. 2.

Phenotypes of KU80 knockout strains. (A) Virulence of strains was determined by intraperitoneal infection of C57BL/6 mice with 200 tachyzoites. Results of a representative experiment (of two experiments) in which groups of four mice were infected with freshly isolated tachyzoites from strain RHΔhxgprt (triangles), strain RHΔku80::HXGPRT (circles), or strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt (squares). (B) Sensitivity of extracellular tachyzoites to phleomycin. Strains RHΔhxgprt (triangles), RHΔku80::HXGPRT (circles), or RHΔku80Δhxgprt (squares) were treated with phleomycin (two replicate experiments; see text), and survival was determined relative to untreated controls. Results of a representative experiment are shown. (C) Sensitivity of extracellular tachyzoites to γ-irradiation. Strains RHΔhxgprt (triangles), RHΔku80::HXGPRT (circles), and RHΔku80Δhxgprt (squares) were treated with γ-irradiation (two replicate experiments; see text), and survival was determined relative to untreated controls. Results of a representative experiment are shown.

GRF at the KU80 locus.

A simple PFU assay strategy was devised to measure the percentage of gene replacement events at the disrupted KU80 locus. This strategy (see Materials and Methods) targeted the replacement of the HXGPRT gene (inserted at the KU80 locus in strain RHΔku80::HXGPRT) with the trifunctional DHFRTKTS gene. Using target DNA flanks of only 1.3 and 0.9 kb carried on targeting plasmid pΔKU80TKFCD, the efficiency of gene replacement at the KU80 locus was 97.1% (±2.3%) (data not shown).

GRF at the uracil phosphoribosyltransferase locus.

To measure gene replacement efficiency in KU80 knockouts compared to parental strains, we targeted the disruption of the UPRT locus. Loss of uracil phosphoribosyltransferase (UPRT) function in any genetic background results in resistance to FUDR (7, 9, 42). A fixed 5′ target DNA flank of 1.3 kb and either a 0.54-kb (plasmid pΔUPT-HXS [not shown]) or a 0.67-kb (plasmid pΔUPT-HXB) 3′ target DNA flank were used in the UPRT disruption assay (Fig. 3A). The frequency of gene replacement (UPRT knockout) was determined at different time points after transfection by plating equal numbers of parasites in either MPA or MPA plus FUDR selection (Fig. 3B). The frequency of gene replacement at the UPRT locus in strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt was 99.8% (±0.6%) when assayed at 20 days posttransfection (Table 2). Similar results were observed using plasmid pΔUPT-HXS (data not shown). The comparative gene replacement percent efficiency in the parental strain RHΔhxgprt was 0.30% (±0.04%). The relative efficiency of gene replacement was enhanced by 300- to 400-fold at the UPRT locus in strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt compared to the efficiency measured in the parental strain RHΔhxgprt.

FIG. 3.

Targeted gene replacement at the uracil phosphoribosyltransferase (UPRT) locus. (A) Strategy for disruption of UPRT by a double-crossover homologous recombination event in strain RHΔhxgprt or RHΔku80Δhxgprt by using a fixed 5′ target flank of 1.3 kb and a 3′ target DNA flank of 0.67 kb on plasmid pΔUPT-HXB. The PCR strategy for genotype verification is depicted using primer pairs to assay for products from the PCR (not to scale). (B) PFU assays were performed at various times after transfection to determine the GRF based on the fraction of parasites that had dual resistance to MPA and FUDR (5 μM) compared to the fraction of parasites that were resistant to MPA (Table 2). (C) Genotype verification of clones selected for MPA resistance after transfection with the pΔUPT-HXB plasmid. For parental strain RHΔhxgprt, PCR 1 was positive (304-bp product; lane b), PCR 2 was positive (460-bp product; lane C), and PCR 3 was negative (840-bp product; lane a). For MPA-resistant clones isolated after transfection with plasmid pΔUPT-HXB, PCR 1 was negative, PCR 2 was positive, and PCR 3 was positive. Control lane (c) contained no template and the PCR 1 and PCR 2 primers. Twelve of 12 MPA-resistant clones revealed targeted gene replacement at the UPRT locus.

TABLE 2.

GRFs at the UPRT locus

| Strain | Plasmid | Day assayed | % Gene replacement at UPRT locus

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | |||

| RHΔhxgprt | pΔUPT-HXB | 10 | 0.26 | 0.20 |

| RHΔhxgprt | pΔUPT-HXB | 14 | 0.31 | 0.29 |

| RHΔhxgprt | pΔUPT-HXB | 20 | 0.33 | 0.26 |

| RHΔku80Δhxgprt | pΔUPT-HXB | 10 | 82.8 | 90.0 |

| RHΔku80Δhxgprt | pΔUPT-HXB | 14 | 97.1 | 96.3 |

| RHΔku80Δhxgprt | pΔUPT-HXB | 20 | 99.2 | 100.4 |

The nonreverting genotype Δku80 Δuprt::HXGPRT was confirmed in several MPA-resistant clones (Fig. 3C). A cleanup vector, pΔUPNC, containing 5′ and 3′ UPRT target DNA flanks but no HXGPRT marker, was then used to target the removal of the integrated HXGPRT marker from the UPRT locus in a clone of strain RHΔku80Δuprt::HXGPRT to generate strain RHΔku80ΔuprtΔhxgprt (data not shown).

Gene replacement at the carbamoyl phosphate synthetase II (CPSII) locus.

Our previous work revealed a very low (∼0.2%) frequency of gene targeting at the essential CPSII locus (15). Gene replacement efficiency at the CPSII locus was examined in strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt using a direct replacement knock-in strategy (Fig. 4A). Target flanks of 1.5 kb 5′ and 0.8 kb 3′ that surrounded the CPSII cDNA minigene and an HXGPRT marker (plasmid pC4HX1-1) were used to delete the endogenous CPSII gene and replace it with a functional CPSII cDNA (CPSIIcDNA) (20). Each MPA-resistant clone failed to produce any PCR 1 product specific to intron 27 of the endogenous CPSII locus and using primers positioned within exons 21 and exon 23 (PCR 2) produced a PCR product that corresponded to targeting cDNA rather than originating from the endogenous CPSII locus (Fig. 4A and B). These results indicated that gene replacement had uniformly occurred at the CPSII locus in strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt. Sequencing of correctly sized PCR 3 and PCR 4 products (data not shown) verified the genotype of this strain as Δku80ΔcpsII::CPSIIcDNAHXGPRT (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

FIG. 4.

Targeted gene replacement at the carbamoyl phosphate synthetase II (CPSII) locus. (A) Strategy for deletion of ∼24 kb of the endogenous CPSII locus by using a functional CPSII cDNA minigene and a downstream HXGPRT marker flanked by a 1.5-kb 5′ target and a 0.8-kb 3′ target. The 37 exons (shaded rectangles) and 36 introns (white rectangles) of the endogenous CPSII locus are shown (not to scale). PCR primer pairs (PCRs 1 to 4; see Materials and Methods) were used to amplify PCR products to verify genotype (not to scale). In strains RHΔhxgprt and RHΔku80Δhxgprt the expected PCR product size from PCR 1 was 382 bp and from PCR 2* was 1,084 bp. If targeted replacement occurred at the CPSII locus, the expected PCR 2 product would be 363 bp, and no product was produced from PCR 1 because the targeting plasmid CPSII cDNA does not contain the PCR 1 primer sites located in intron 27 (see panel A above). (B) Twelve of 12 MPA-resistant clones revealed targeted gene replacement occurred at the CPSII locus in strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt. To more clearly visualize PCR products those from PCR 1 were resolved for ∼45 min using the markers in lane M1, and then the same agarose gel was reloaded with PCR products from PCR 2 and using markers in lane M2 for the control. Control lane C shows the products from PCR 1 (382-bp product) and PCR 2* (1,084-bp product) using parental RHΔku80Δhxgprt template DNA (endogenous CPSII locus).

Parameters affecting the efficiency of gene targeting in KU80 knockouts.

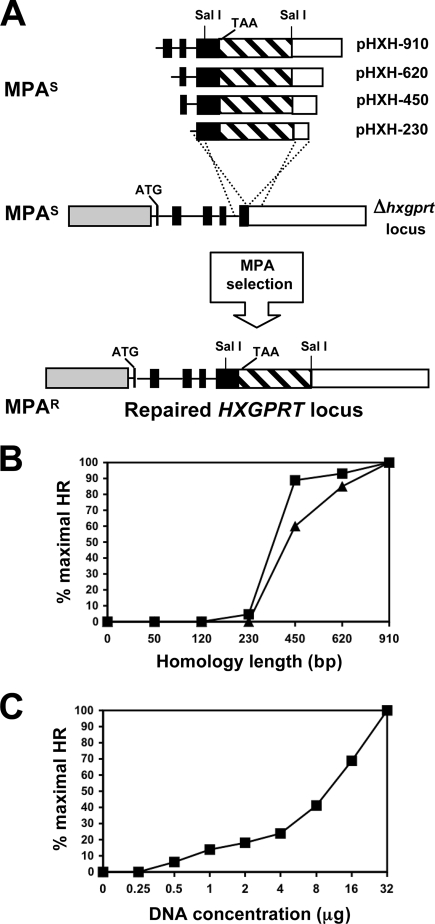

In fungal strains deficient for NHEJ the overall gene targeting efficiency is increased due to a marked reduction in the frequency of nonhomologous recombination, rather than to any significant increase in the efficiency of homologous recombination (25, 35, 39, 41). To verify that loss of nonhomologous recombination is the explanation behind increased gene targeting efficiency in KU80 knockouts versus the alternative mechanism, that homologous recombination efficiency is increased, we devised a novel strategy to specifically and quantitatively measure homologous recombination (only double-crossover events) in Δhxgprt genetic backgrounds of both the Δku80 and the parental strain. As shown in Fig. 5A, this strategy targets the repair of a disrupted Δhxgprt locus. The output of each targeted repair event is a single MPA-resistant PFU (see Materials and Methods). No PFU can arise from any nonhomologous recombination event (even if they occur), because each targeting plasmid carries only a fragment of the HXGPRT gene that cannot confer MPA resistance in the Δhxgprt background. Double-crossover homologous recombination mediated by targeting DNA flank lengths of 0, 50, 120, 230, 450, 620, and 910 bp was examined. At each target DNA flank length (except 230 bp) the efficiency of gene replacement via double-crossover homologous recombination at the HXGPRT locus was similar (within twofold on a per parasite basis [data not shown]) between strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt and the parental strain, RHΔhxgprt (Fig. 5B). These results, along with data shown in Fig. 2, 3, and 4 and Table 2, reveal that the increased gene targeting efficiency in KU80 knockouts arises from the loss of a major nonhomologous recombination pathway rather than from any significant increase in the efficiency of homologous recombination.

FIG. 5.

KU80 knockouts efficiently target gene replacements due to a deficiency in nonhomologous recombination. (A) Strategy for targeted repair of the Δhxgprt locus using different lengths of flanking target DNA that surround a 1.5-kb SalI fragment that is deleted in the Δhxgprt background (see text). (Top) Targeting plasmids with 230-, 450-, 620-, and 910-bp target DNA flanks are shown. Plasmids with 120-bp, 50-bp, or 0-bp targeting DNA flanks are not shown. All pHXH targeting plasmids are MPA sensitive (MPAs). The termination codon (TAA) of the HXGPRT gene is shown. (Middle) The structure of the Δhxgprt locus for MPAs strains RHΔhxgprt and RHΔku80Δhxgprt is shown. The gene structure is depicted by exons (dark rectangles), introns (lines), a 5′ UTR (gray rectangle), 3′ UTR (rectangular box with diagonal lines), and a far downstream 3′ UTR (open rectangle). The disrupted locus contains an intact 5′ UTR, intact exon 1 (ATG start is shown) to exon 4, and the deletion in exon 5 and the 3′ UTR contained in the missing 1.5-kb SalI fragment. A hypothetical double-crossover homologous recombination gene targeting event is shown by the dotted lines linking the targeting pHXH plasmids. (Bottom) MPA-resistant (MPAr) parasites can only arise by the double-crossover homologous recombination gene targeting event shown. (B) The percent maximal homologous recombination was determined in strain RHΔhxgprt (triangles) and strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt (squares) (see Materials and Methods). (C) The percent maximal homologous recombination was determined as a function of targeting DNA concentration.

The minimal target DNA flank length for gene replacement at the HXGPRT locus was determined (Fig. 5B). No gene replacement events were detected in strain RHΔhxgprt when we used 230-bp target DNA flanks. While strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt exhibited a detectable frequency of gene replacement using 230-bp target DNA flanks, the overall efficiency was reduced by 22-fold compared to target DNA flanks of 450 bp or more (Fig. 5B). No gene replacement events were detected using target DNA flanks of 120 bp or less in any strain.

The efficiency of gene replacement at the HXGPRT locus was dependent on targeting DNA concentration (Fig. 5C). No gene replacement events were detected at the HXGPRT locus using circular targeting DNA in strain RHΔhxgprt. In contrast, a detectable frequency was observed in strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt, although the efficiency of gene replacement was reduced by 20-fold compared to linearized targeting DNA.

DISCUSSION

A nonreverting gene knockout at the KU80 locus functionally disrupts the NHEJ DSB DNA repair pathway in T. gondii. Due to disruption of nonhomologous recombination mediated by the NHEJ pathway, KU80 knockouts exhibit a markedly higher gene replacement efficiency compared to wild-type strains. Our results suggest that disruption of KU80 leads to a nearly complete disruption of all nonhomologous recombination-mediated DSB DNA repair pathways in T. gondii. To our knowledge, this is the first report that clearly demonstrates the existence of a functional and significant KU-dependent NHEJ pathway in a protozoan parasite.

Readily identifiable KU genes are notably absent in Plasmodium species (http://plasmodb.org/plasmo; release 5). KU proteins are present but they do not participate in NHEJ in other protozoans such as Leishmania and Trypanosoma species (1, 24). It is puzzling that while NHEJ is prevalent in eukaryotes, a functional NHEJ pathway has not been previously described in protozoa. We speculate that acquisition and retention of a functional NHEJ DSB DNA repair pathway in T. gondii may correlate with the presence of extracellular developmental stages that occur in the oocyst. The oocyst stage must maintain viability through development and maintenance of sporocysts and sporozoites under harsh environmental conditions in soil and water for a long period of time prior to their successful transmission to intermediate hosts via oral ingestion.

The mechanisms of NHEJ had not been previously dissected in T. gondii. Our results show KU80 to be an essential component of the NHEJ mechanism in T. gondii. The Toxoplasma gondii genome (http://beta.toxodb.org/toxo5.0/) also reveals genes encoding putative DNA ligase IV (TGGT1_073840) and DNA-dependent protein kinase (57.m01765) components of eukaryotic NHEJ. Similar to other described proteins from parasites in the phylum Apicomplexa (16, 19), the predicted KU70 and KU80 proteins are markedly enlarged compared to other species of known KU proteins. Before initiating our studies at the KU80 gene, we targeted knockouts directed at both the KU70 gene and the DNA ligase IV gene, and these knockout attempts were not successful in strain RHΔhxgprt. Subsequent attempts to disrupt KU70 and the DNA ligase IV gene in the RHΔku80Δhxgprt background were also unsuccessful. Our negative results at these two loci suggest that these genes encode essential functions, or that their loci are refractory to gene targeting (data not shown).

KU80 knockouts retain a normal tachyzoite growth rate as well as high virulence typical of type I strains in murine infection. KU80 knockouts are highly stable in culture and have shown no fluctuation in growth rate, virulence, or the enhanced gene targeting phenotype after continuous passage for more than 1,600 generations. KU80 knockouts do exhibit an increased sensitivity to double-strand DNA breaks induced by phleomycin or γ-irradiation. No other major cellular or developmental defects have been noted so far in most fungal organisms disrupted in NHEJ (25, 35, 39, 41).

We find circular DNA to be a particularly poor substrate for double-crossover homologous recombination necessary for gene replacement in T. gondii. This conclusion is also supported by previous evidence (8). We find that DNA target flanks of 120 bp or less do not produce detectable gene replacements at the HXGPRT locus. Using targeting strategies directed at the UPRT, CPSII, KU80, and HXGPRT loci, we showed that efficient gene targeting now occurs in KU80 knockouts using target DNA flanks of ∼500 bp or greater.

Recently, downstream markers such as UPRT, HXGPRT, or YFP have been used to enrich selected populations for desired double gene replacement events (23, 36, 37). Our results validate the use of the CD marker outside of the targeting cassette as another potent strategy to enrich for desired gene replacements in negative selection.

The HXGPRT selectable marker was precisely “cleaned” from two loci (Δku80::HXGPRT and Δuprt::HXGPRT) in two of the four sequential gene replacement steps used to develop the triple mutant strain RHΔku80ΔuprtΔhxgprt (Table 1). Strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt provides an excellent genetic background for the efficient development of multiply manipulated strains using only the HXGPRT selectable marker.

Our results at the CPSII locus validate an efficient approach to complement a null phenotype (15) by direct gene replacement (of at least 24 kb) in strain RHΔku80Δhxgprt. This experiment illustrates that the RHΔku80Δhxgprt strain now enables more detailed studies on complementation and deciphering gene function(s) by directly targeting endogenous gene loci. This same knock-in double-crossover strategy can be used in the RHΔku80Δhxgprt strain to directly and efficiently tag a protein (c-myc, HA, YFP/GFP/RFP, etc.) or to rapidly place a gene under regulatable protein (28) or transcriptional (48) expression.

Parasites from the phylum Apicomplexa, including Plasmodium, Cryptosporidium, Babesia, Theileria, and other related species (Eimeria and Neospora) possess many genes that share significant homology with T. gondii genes. A significant fraction of these genes are also selectively unique to the Apicomplexa, and these genes are often designated as a “hypothetical protein” (www.EuPathDB.org). Consequently, any gene knockout developed in the Δku80 Δhxgprt genetic background that reveals a biological phenotype can be used in complementation studies to replace the inserted HXGPRT marker (6TX negative selection) with the coding region of the complementing gene to clearly demonstrate a biological function for that “hypothetical” gene across the Apicomplexa.

Our results demonstrate that the KU80 knockout genetic background is a valuable tool for higher-throughput development of nonreverting gene knockouts and gene replacements necessary for postgenome functional analysis of T. gondii. Our laboratory developed the Δku80 Δhxgprt genetic background to enable a global genetic dissection of the Toxoplasma gondii “nutriome,” the collection of pathways and mechanisms controlling the acquisition of essential nutrients fueling obligate intracellular parasitism (2, 15, 17, 18, 20, 40). Fundamental questions remain to be answered as to how this clever obligate intracellular parasite has learned to successfully adapt to a large menu of host cells and hosts. The ability to now efficiently target gene replacements in the Δku80 background is an important advancement for this model organism. Accelerated genetic dissection of protozoan parasite biology will more quickly lead to new treatments for significant parasitic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Leah M. Rommereim (Dartmouth) for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Nicholas C. Callahan for construction of several pHXH plasmids used in this study. The work of the developers of the Toxoplasma gondii Genome Resource at www.ToxoDB.org is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was partially supported by the NIH (AI073142, AI075931, and AI41930). This work was supported by the use of facilities that were provided from the Irradiation Shared Resource of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Norris Cotton Cancer Center. ToxoDB, PlasmoDB, and EuPathDB are part of the NIH NIAID-funded Bioinformatics Resource Center.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 February 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burton, P., D. J. McBride, J. M. Wilkes, J. D. Barry, and R. McCulloch. 2007. Ku heterodimer-independent end joining in Trypanosoma brucei cell extracts relies upon sequence microhomology. Eukaryot. Cell 61773-1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaudhary, K., B. A. Fox, and D. J. Bzik. 2007. Toxoplasma gondii: the model apicomplexan parasite: perspectives and methods. Elsevier, London, United Kingdom.

- 3.Colot, H. V., G. Park, G. E. Turner, C. Ringelberg, C. M. Crew, L. Litvinkova, R. L. Weiss, K. A. Borkovich, and J. C. Dunlap. 2006. A high-throughput gene knockout procedure for Neurospora reveals functions for multiple transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10310352-10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conway, C., R. McCulloch, M. L. Ginger, N. P. Robinson, A. Browitt, and J. D. Barry. 2002. Ku is important for telomere maintenance, but not for differential expression of telomeric VSG genes, in African trypanosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 27721269-21277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz, A., and S. M. Beverley. 1990. Gene replacement in parasitic protozoa. Nature 348171-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donald, R. G., D. Carter, B. Ullman, and D. S. Roos. 1996. Insertional tagging, cloning, and expression of the Toxoplasma gondii hypoxanthine-xanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase gene. Use as a selectable marker for stable transformation. J. Biol. Chem. 27114010-14019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donald, R. G., and D. S. Roos. 1998. Gene knock-outs and allelic replacements in Toxoplasma gondii: HXGPRT as a selectable marker for hit-and-run mutagenesis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 91295-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donald, R. G., and D. S. Roos. 1994. Homologous recombination and gene replacement at the dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase locus in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 63243-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donald, R. G., and D. S. Roos. 1995. Insertional mutagenesis and marker rescue in a protozoan parasite: cloning of the uracil phosphoribosyltransferase locus from Toxoplasma gondii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 925749-5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donald, R. G., and D. S. Roos. 1993. Stable molecular transformation of Toxoplasma gondii: a selectable dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase marker based on drug-resistance mutations in malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9011703-11707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunlap, J. C., K. A. Borkovich, M. R. Henn, G. E. Turner, M. S. Sachs, N. L. Glass, K. McCluskey, M. Plamann, J. E. Galagan, B. W. Birren, R. L. Weiss, J. P. Townsend, J. J. Loros, M. A. Nelson, R. Lambreghts, H. V. Colot, G. Park, P. Collopy, C. Ringelberg, C. Crew, L. Litvinkova, D. DeCaprio, H. M. Hood, S. Curilla, M. Shi, M. Crawford, M. Koerhsen, P. Montgomery, L. Larson, M. Pearson, T. Kasuga, C. Tian, M. Basturkmen, L. Altamirano, and J. Xu. 2007. Enabling a community to dissect an organism: overview of the Neurospora functional genomics project. Adv. Genet. 5749-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eid, J., and B. Sollner-Webb. 1991. Stable integrative transformation of Trypanosoma brucei that occurs exclusively by homologous recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 882118-2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox, B. A., A. A. Belperron, and D. J. Bzik. 2001. Negative selection of herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 11685-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox, B. A., A. A. Belperron, and D. J. Bzik. 1999. Stable transformation of Toxoplasma gondii based on a pyrimethamine resistant trifunctional dihydrofolate reductase-cytosine deaminase-thymidylate synthase gene that confers sensitivity to 5-fluorocytosine. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 9893-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox, B. A., and D. J. Bzik. 2002. De novo pyrimidine biosynthesis is required for virulence of Toxoplasma gondii. Nature 415926-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox, B. A., and D. J. Bzik. 2003. Organisation and sequence determination of glutamine-dependent carbamoyl phosphate synthetase II in Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 3389-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox, B. A., K. Chaudhary, and D. J. Bzik. 2007. Toxoplasma: molecular and cellular biology. Horizon Bioscience, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 18.Fox, B. A., J. P. Gigley, and D. J. Bzik. 2004. Toxoplasma gondii lacks the enzymes required for de novo arginine biosynthesis and arginine starvation triggers cyst formation. Int. J. Parasitol. 34323-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox, B. A., W. B. Li, M. Tanaka, J. Inselburg, and D. J. Bzik. 1993. Molecular characterization of the largest subunit of Plasmodium falciparum RNA polymerase I. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 6137-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox, B. A., J. G. Ristuccia, and D. J. Bzik. 2008. Genetic dissection of essential indels and domains in carbamoyl phosphate synthetase II of Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 39533-539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardner, M. J., N. Hall, E. Fung, O. White, M. Berriman, R. W. Hyman, J. M. Carlton, A. Pain, K. E. Nelson, S. Bowman, I. T. Paulsen, K. James, J. A. Eisen, K. Rutherford, S. L. Salzberg, A. Craig, S. Kyes, M. S. Chan, V. Nene, S. J. Shallom, B. Suh, J. Peterson, S. Angiuoli, M. Pertea, J. Allen, J. Selengut, D. Haft, M. W. Mather, A. B. Vaidya, D. M. Martin, A. H. Fairlamb, M. J. Fraunholz, D. S. Roos, S. A. Ralph, G. I. McFadden, L. M. Cummings, G. M. Subramanian, C. Mungall, J. C. Venter, D. J. Carucci, S. L. Hoffman, C. Newbold, R. W. Davis, C. M. Fraser, and B. Barrell. 2002. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 419498-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giaever, G., A. M. Chu, L. Ni, C. Connelly, L. Riles, S. Veronneau, S. Dow, A. Lucau-Danila, K. Anderson, B. Andre, A. P. Arkin, A. Astromoff, M. El-Bakkoury, R. Bangham, R. Benito, S. Brachat, S. Campanaro, M. Curtiss, K. Davis, A. Deutschbauer, K. D. Entian, P. Flaherty, F. Foury, D. J. Garfinkel, M. Gerstein, D. Gotte, U. Guldener, J. H. Hegemann, S. Hempel, Z. Herman, D. F. Jaramillo, D. E. Kelly, S. L. Kelly, P. Kotter, D. LaBonte, D. C. Lamb, N. Lan, H. Liang, H. Liao, L. Liu, C. Luo, M. Lussier, R. Mao, P. Menard, S. L. Ooi, J. L. Revuelta, C. J. Roberts, M. Rose, P. Ross-Macdonald, B. Scherens, G. Schimmack, B. Shafer, D. D. Shoemaker, S. Sookhai-Mahadeo, R. K. Storms, J. N. Strathern, G. Valle, M. Voet, G. Volckaert, C. Y. Wang, T. R. Ward, J. Wilhelmy, E. A. Winzeler, Y. Yang, G. Yen, E. Youngman, K. Yu, H. Bussey, J. D. Boeke, M. Snyder, P. Philippsen, R. W. Davis, and M. Johnston. 2002. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 418387-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbert, L. A., S. Ravindran, J. M. Turetzky, J. C. Boothroyd, and P. J. Bradley. 2007. Toxoplasma gondii targets a protein phosphatase 2C to the nuclei of infected host cells. Eukaryot. Cell 673-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glover, L., R. McCulloch, and D. Horn. 2008. Sequence homology and microhomology dominate chromosomal double-strand break repair in African trypanosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 362608-2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goins, C. L., K. J. Gerik, and J. K. Lodge. 2006. Improvements to gene deletion in the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans: absence of Ku proteins increases homologous recombination, and co-transformation of independent DNA molecules allows rapid complementation of deletion phenotypes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43531-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gubbels, M. J., M. Lehmann, M. Muthalagi, M. E. Jerome, C. F. Brooks, T. Szatanek, J. Flynn, B. Parrot, J. Radke, B. Striepen, and M. W. White. 2008. Forward genetic analysis of the apicomplexan cell division cycle in Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 4e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haber, J. E. 2000. Partners and pathways repairing a double-strand break. Trends Genet. 16259-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herm-Gotz, A., C. Agop-Nersesian, S. Munter, J. S. Grimley, T. J. Wandless, F. Frischknecht, and M. Meissner. 2007. Rapid control of protein level in the apicomplexan Toxoplasma gondii. Nat. Methods 41003-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishibashi, K., K. Suzuki, Y. Ando, C. Takakura, and H. Inoue. 2006. Nonhomologous chromosomal integration of foreign DNA is completely dependent on MUS-53 (human Lig4 homolog) in Neurospora. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10314871-14876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janzen, C. J., F. Lander, O. Dreesen, and G. A. Cross. 2004. Telomere length regulation and transcriptional silencing in KU80-deficient Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res. 326575-6584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim, K., D. Soldati, and J. C. Boothroyd. 1993. Gene replacement in Toxoplasma gondii with chloramphenicol acetyltransferase as selectable marker. Science 262911-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim, K., and L. M. Weiss. 2004. Toxoplasma gondii: the model apicomplexan. Int. J. Parasitol. 34423-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, K., and L. M. Weiss. 2008. Toxoplasma: the next 100 years. Microbes Infect. 10978-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirisits, M. J., E. Mui, and R. McLeod. 2000. Measurement of the efficacy of vaccines and antimicrobial therapy against infection with Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 30149-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kooistra, R., P. J. Hooykaas, and H. Y. Steensma. 2004. Efficient gene targeting in Kluyveromyces lactis. Yeast 21781-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazumdar, J., E. H. Wilson, K. Masek, C. A. Hunter, and B. Striepen. 2006. Apicoplast fatty acid synthesis is essential for organelle biogenesis and parasite survival in Toxoplasma gondii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10313192-13197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mercier, C., J. F. Dubremetz, B. Rauscher, L. Lecordier, L. D. Sibley, and M. F. Cesbron-Delauw. 2002. Biogenesis of nanotubular network in Toxoplasma parasitophorous vacuole induced by parasite proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 132397-2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Messina, M., I. Niesman, C. Mercier, and L. D. Sibley. 1995. Stable DNA transformation of Toxoplasma gondii using phleomycin selection. Gene 165213-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer, V., M. Arentshorst, A. El-Ghezal, A. C. Drews, R. Kooistra, C. A. van den Hondel, and A. F. Ram. 2007. Highly efficient gene targeting in the Aspergillus niger kusA mutant. J. Biotechnol. 128770-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ngo, H. M., E. O. Ngo, D. J. Bzik, and K. A. Joiner. 2000. Toxoplasma gondii: are host cell adenosine nucleotides a direct source for purine salvage? Exp. Parasitol. 95148-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ninomiya, Y., K. Suzuki, C. Ishii, and H. Inoue. 2004. Highly efficient gene replacements in Neurospora strains deficient for nonhomologous end-joining. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10112248-12253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pfefferkorn, E. R. 1978. Toxoplasma gondii: the enzymic defect of a mutant resistant to 5-fluorodeoxyuridine. Exp. Parasitol. 4426-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pfefferkorn, E. R., D. J. Bzik, and C. P. Honsinger. 2001. Toxoplasma gondii: mechanism of the parasitostatic action of 6-thioxanthine. Exp. Parasitol. 99235-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pfefferkorn, E. R., and L. C. Pfefferkorn. 1976. Toxoplasma gondii: isolation and preliminary characterization of temperature-sensitive mutants. Exp. Parasitol. 39365-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roos, D. S., W. J. Sullivan, B. Striepen, W. Bohne, and R. G. Donald. 1997. Tagging genes and trapping promoters in Toxoplasma gondii by insertional mutagenesis. Methods 13112-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabin, A. B. 1941. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in children. JAMA 116801-807. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaw, M. K., D. S. Roos, and L. G. Tilney. 2001. DNA replication and daughter cell budding are not tightly linked in the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Microbes Infect. 3351-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Poppel, N. F., J. Welagen, R. F. Duisters, A. N. Vermeulen, and D. Schaap. 2006. Tight control of transcription in Toxoplasma gondii using an alternative tet repressor. Int. J. Parasitol. 36443-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker, J. R., R. A. Corpina, and J. Goldberg. 2001. Structure of the Ku heterodimer bound to DNA and its implications for double-strand break repair. Nature 412607-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, D., L. M. Topper, and T. E. Wilson. 2008. Recruitment and dissociation of nonhomologous end joining proteins at a DNA double-strand break in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1781237-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu, Y., L. A. Kirkman, and T. E. Wellems. 1996. Transformation of Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites by homologous integration of plasmids that confer resistance to pyrimethamine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 931130-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.