Abstract

Background

The proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-18 (IL-18) is associated with major disabling conditions, although whether as byproduct or driver is unclear. The role of common variation in the IL-18 gene on serum concentrations and functioning in old age is unknown.

Methods

We used 1671 participants aged 65–80 years from two studies: the InCHIANTI study and wave 6 of the Iowa-Established Populations for Epidemiological Study of the Elderly (EPESE). We tested three common polymorphisms against IL-18 concentration and measures of functioning.

Results

In the InCHIANTI study, a 1 standard deviation increase in serum IL-18 concentrations was associated with an increased chance of being in the 20% of slowest walkers (odds ratio 1.45; 95% confidence interval, 1.17–1.80; p = .0007) and 20% of those with poorest function based on the Short Physical Performance Battery Score (odds ratio 1.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.22–1.89; p =.00016) in age sex adjusted logistic regression models. There was no association with Activities of Daily Living (p = .26) or Mini-Mental State Examination score (p = .66). The C allele of the IL-18 polymorphism rs5744256 reduced serum concentrations of IL-18 by 39 pmol/mL per allele (p = .00001). The rs5744256 single nucleotide polymorphism was also associated with shorter walk times in InCHIANTI (n =662, p =.016) and Iowa-EPESE (n =995, p =.026). In pooled ranked models rs5744256 was also associated with higher SPPB scores (n =1671, p = .019). Instead of adjusting for confounders in the IL-18 walk time association, we used rs5744256 in a Mendelian randomization analysis: The association remained in instrumental variable models (p = .021).

Conclusion

IL-18 concentrations are associated with physical function in 65- to 80-year-olds. A polymorphism in the IL-18 gene alters IL-18 concentrations and is associated with an improvement in walk speed. IL-18 may play an active role in age-related functional impairment, but these findings need independent replication.

Interleukin-18 (IL-18) is a powerful proinflammatory cytokine, with effects on both innate and acquired immunity (1). Raised serum concentrations of IL-18 have been implicated in atherosclerosis (2), myocardial infarction (3), rheumatoid arthritis (4), inflammatory bowel disease (5), asthma (6), and response to infection (7). IL-18 is also a possible mediator of neurodegeneration (8). As many of these conditions contribute to disability, and inflammation is a key driver of aging (9–11), IL-18 is a good candidate for causing early onset of disability in older people.

IL-18 serum concentrations increase with age (12), and are higher in healthy centenarians compared to younger controls (13). However, an association of higher IL-18 serum concentrations with aging phenotypes may not be causal. IL-18 concentrations may be raised as a by-product of disease or other processes producing physical decline. It is also possible that unaccounted for confounding factors may result in misleading associations. Assuming an ethnically homogeneous population, genes are randomly assigned to offspring at conception. Reverse causation or confounding factors are therefore very unlikely to affect polymorphisms. A gene variant that alters a potential risk factor provides a natural experiment analogous to a randomized controlled trial of the risk factor: If a polymorphism changes a risk factor but does not produce a linked and proportionate change in outcomes, then by implication the risk factor is unlikely to play an active role in producing the outcomes. This “Mendelian randomization” approach has recently shown that the association between C-reactive protein and features of the metabolic syndrome is unlikely to be causal (14).

The role of common variation in the IL-18 gene in aging-related disease and disability has not been well studied. In a recent study of four genes in the IL-18 system (IL-18, IL-18 receptor, IL-18 receptor accessory protein, and IL-18 binding protein) using 1288 patients with coronary artery disease (15), one single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was found to alter IL-18 serum levels. This SNP was also predictive of cardiovascular mortality over 6 years, but further studies will be needed to confirm this association.

The timing of onset of physical and cognitive functional limitations is a core marker of biological age (16), and functioning is often a more useful measure of older people’s health than are individual diseases, as multiple diseases are common and severity varies widely. Many aspects of physical functioning—including muscle strength (17), gait speed, and time to complete five chair stands (18)—show substantial heritability in older people. Cognitive function is also highly heritable (19,20).

In this study, we tested three related hypotheses: (i) that common variation in the IL-18 gene alters IL-18 serum concentrations, (ii) that increased IL-18 serum concentrations are associated with impaired functioning in old age, and (iii) that IL-18 gene alleles that reduce IL-18 concentrations also improve physical functioning in old age. To do this, we used IL-18 serum concentrations and functioning data from the InCHIANTI study (21). We used a Mendelian randomization (22) approach to test the strength of association between IL-18 concentrations and measures of functioning free from reverse causality and confounding. We used a second study, the Iowa- Established Populations for Epidemiological Study of the Elderly (EPESE) study population, to add further evidence on the role of IL-18 in aging related phenotypes.

Methods

The InCHIANTI Study

InCHIANTI (21) is a study of decline of mobility in late life, with a sample representative of the population aged 65 or older of two small towns in Tuscany, Italy. The participants were all of white European origin. The Italian National Institute of Research and Care of Aging Institutional Review Board ratified the study protocol.

During the interviews, participants were asked about difficulties performing six Activities of Daily Living (ADL), including bathing, dressing, eating, grooming, toileting, and continence. InCHIANTI participants were classified as having difficulty only if they required help or were unable to perform the task. This requirement identified a relatively small proportion of participants who were very disabled. The Short Physical Performance Battery score (SPPB) (23) was based on the results of balance tests, times to complete two 4-meter walks, and times to stand up from the seated position five times. The SPPB has been validated as a predictive marker for mortality and disability incidence (23). A 7-meter usual pace walk was also used. In addition, we used the Mini-Mental State Examination score (24) to assess cognitive functioning. Details of the InCHIANTI participants are given in Table 1. Fasting IL-18 serum concentrations were measured as described by Ferrucci and colleagues (12).

Table 1.

Details of Participants Aged 65–80 Years in the InCHIANTI and Iowa-EPESE Studies

| Trait | InCHIANTI | Iowa-EPESE |

|---|---|---|

| N | 674 | 997 |

| % Male | 46% | 37% |

| Age, y | 72 | 75 |

| ADL (n poor functioning ≥ 1 ADL; InCHIANTI-requiring help, Iowa-EPESE difficulty with ADL) | 24 (3.4%) | 444 (43%) |

| Summary Physical Performance Battery (range 0–12) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 10.61 (2.4) | 8.50 (2.6) |

| N poor functioning | 115 (17%) | 203 (20%) |

| Walking times, s | 7-m walk | 8-ft walk |

| Mean (SD) | 6.26 (2.4) | 3.94 (1.8) |

| N poor functioning | 131 (20%) | 193 (19%) |

| Cognitive function (MMSE in InCHIANTI, SPMSQ in Iowa-EPESE) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 25.7 (3.2) | 0.6 (0.9) |

| N poor functioning (≤ 23 MMSE, ≥ 2 SPMSQ) | 141 (20%) | 119 (12%) |

Note: For Activities of Daily Living (ADL), poor functioning is defined as needing help from another person or unable to do one or more of the activities (dressing, bathing, eating, grooming, toileting, or continence). Poor functioning for the performance scores, walking times, and cognitive levels are defined as the lowest 20%, slowest 20%, and lowest 20%, respectively, of the measured variable within the 65- to 80-year age group.

EPESE =Established Populations for Epidemiological Study of the Elderly; SD = standard deviation; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; SPMSQ = Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire.

Iowa-EPESE

The study design of the EPESE is described elsewhere (25). Briefly, between 1981 and 1983 the entire population aged 65 years or older, living in two Iowa counties was surveyed, and follow-up data were collected yearly for 7 years. Blood specimens were obtained from those participants reinterviewed for the sixth annual follow-up in 1988. To avoid confounding by ethnicity, we limited analyses to participants reporting that they were “White” to a question about race. Of these participants, 11% did not know the specific national or geographic origin of their maternal or paternal families, so we adjusted for this in models including Iowa-EPESE data by including two different values for ethnic origin: “known white” and “white but parents of unknown country of origin.”

ADL items in this study included bathing, grooming, dressing, eating without aid, transferring from bed to chair, and using the toilet. The number of ADL problems was counted as tasks for which the participant reported difficulty irrespective of any need for help—this was a lower disability threshold than that used in the InCHIANTI study. The three components of the SPPB were tested in a way similar to those in the InCHIANTI study, except that the usual pace walk test distance was short (8 feet) and timings were carried out by stopwatch rather than by electronic sensors. The Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (26) was used to measure cognition. IL-18 concentrations were not available in this study.

Genetic Analyses

We used data from the HapMap (phase I) (http://www.hapmap.org/) project to select an optimum set of SNPs from the IL-18 gene with minor allele frequencies > 0.1. Three SNPs (rs5744256, rs543810, and rs1293344) were selected that correlated with a minimum r2 ≥ 0.8 with all other SNPs in the IL-18 gene. During the study, HapMap phase II data became available, and reanalysis showed that the three SNPs correlated with 15 of 21 SNPs at r2 > 0.8 and 17 SNPs at r2 > 0.5.

A previous study described two SNPs associated with IL-18 serum concentrations (15). Neither of these SNPs occurs in HapMap II. To ensure that we captured the information from these variants, we sequenced 581 bp of IL-18 containing the two SNPs IL-18/A+183G (rs5744292) and IL-18/T+533C (rs4937100) (15) in the 90 European HapMap samples. We then compared patterns of linkage disequilibrium between HapMap SNPs and the sequenced SNPs.

With the InCHIANTI DNA samples we first performed whole genome amplification, including 6% blind duplicates. We used the modified TaqMan assays at KBiosciences (Hoddesdon, U.K.) to generate genotypes from both SNPs for all samples including duplicates. For the Iowa-EPESE samples, we used conventional TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Statistical Analysis

Most physical functioning measures can be analyzed as continuous variables, but are really ordinal scores that are more sensitive in identifying poor function: Analyses, therefore, used both linear and logistic regression models. We used logistic regression to calculate odds ratios of being among the poor functioning groups given a 1 standard deviation (SD) increase in IL-18 concentrations, using z scores of logged serum concentrations. All analyses were corrected for age and sex, as IL-18 serum concentrations are associated with these covariates (12). Details differed in the methods for the measures, so we used ranked data from each study (SPPB in 12 ranks, walk speed in 30) to combine in pooled analyses. All pooled models were adjusted for age, sex, study, plus known versus unknown family origin for Iowa-EPESE (but included only those reporting being white to a question about race).

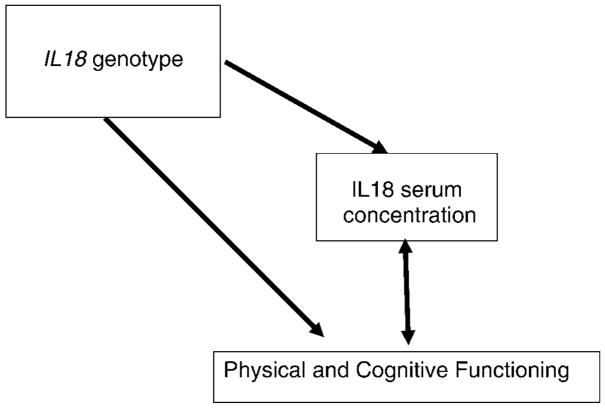

We used a Mendelian randomization (22) approach, implemented with the instrumental variables (27) options in Stata v9 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), to obtain estimates of the associations between IL-18 serum concentrations and performance measures free from reverse causality or confounding. We compared the instrumental variable estimates of the association between IL-18 concentration and performance measures to those from ordinary linear regression using a Durbin–Wu–Hausman endogeneity test based on the C statistic. This is analogous to testing whether any observed associations between SNPs and functioning were consistent with the expected association, given (a) the association between SNPs and IL-18 serum concentrations and (b) the correlation between IL-18 concentrations and functioning (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Triangle of associations of interleukin-18 (IL-18) genotypes, IL-18 serum concentrations, and physical functioning in old age. Possible causal directions of associations are shown by direction of arrows. Physical functioning and IL-18 concentrations cannot alter genotypes, but causal associations between physical functioning and IL-18 concentrations could occur in both directions.

Results

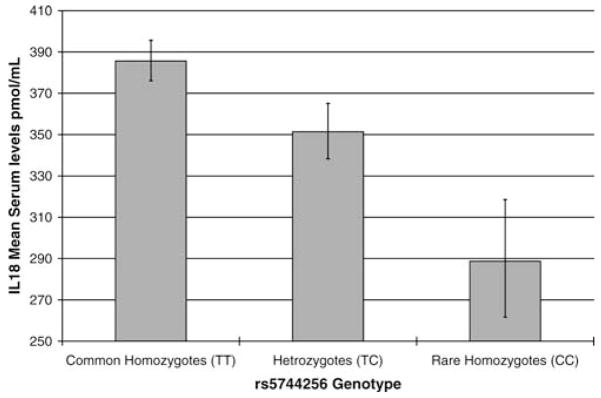

IL-18 Genotype Alters IL-18 Serum Concentration

The effects of IL-18 genotypes on IL-18 serum concentrations are shown in Figure 2. There was a highly significant decrease in IL-18 concentrations for each additional C allele of rs5744256: Mean serum concentrations were 76.8 pmol/mL (0.5 SD) lower in rare homozygotes (TT) compared to common homozygotes (CC) (linear regression p = 1 × 10−5). There were no significant associations with the other two SNPs (rs543810, p =.31, rs1293344, p =.11).

Figure 2.

Mean interleukin-18 (IL-18) concentrations by alleles of the haplotype tagging IL-18 single nucleotide polymorphism rs5744256 (In-CHIANTI study, ages 65–80 years). Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted linear regression p = 1 ×10−5.

All genotyped SNPs were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p > .05), and the genotyping error rate, as assessed by blind duplicates, was < 1% for each SNP. Our sequencing analysis in HapMap samples showed that rs5744256 is also strongly correlated (r2 = 0.85) with the IL-18/A+183G (rs5744292) SNP reported by Tiret and colleagues (15) as associated with IL-18 concentrations.

IL-18 Serum Concentrations Are Associated With Functioning in Old Age

Using the InCHIANTI participants, we found associations between IL-18 serum concentrations and the tested physical performance measures (SPPB and 7-meter walk-time) in both linear and logistic models (Table 2). A 1 SD increase in IL-18 serum concentrations was associated with an increased chance of being in the 20% of slowest walkers (odds ratio, 1.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.17–1.80; p = .0007) and 20% of poorest functioning participants based on the Summary Performance Scores (SPPB) (odds ratio, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.22–1.89; p = .00016). There was no association with ADL (p = .26) or Mini-Mental State Examination (p = .66).

Table 2.

Associations of IL-18 Serum Levels (Log Transformed) With Measures of Function in the InCHIANTI Study (Ages 65–80 Years)

| Performance Measure | Linear Regression Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value (Regression Coefficient) | Odds Ratio for Being in Poorest Functioning Group Given a 1 SD Increase in IL-18 (95% CI) | p Value for Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported functioning | ||||

| ADLs | 0.11 (−0.01 to 0.23) | .076 | 1.27 (0.84–1.91) | .26 |

| Tested physical performance | ||||

| Summary Physical Performance Battery | −0.76 (−1.25 to −0.28) | .002 | 1.52 (1.22–1.89) | .00016 |

| Walking test (7 m) | 0.08 (0.03–0.13) | .00096 | 1.45 (1.17–1.80) | .00070 |

| Tested cognitive function | ||||

| MMSE | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | .466 | 1.05 (0.86–1.28) | .66 |

Notes: All models were adjusted for age and sex. Poorest functioning groups are defined as: 1 or more Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), lowest 20% of performance scores, slowest 20% of walking times, and lowest 20% Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores within the 65–80 age group.

IL-18 = interleukin-18; CI = confidence interval; SD = standard deviation.

IL-18 rs5744256 SNP Is Associated With Physical Functioning

Using both the InCHIANTI and Iowa-EPESE studies, we next assessed the role of the IL-18 rs5744256 SNP on the functional measures associated with IL-18 concentrations. We hypothesized that C allele carriers would have lower rates of limitation in physical functioning, given that the C allele reduces IL-18 concentrations and the positive correlation between IL-18 concentrations and functioning.

In the InCHIANTI study, the rs5744256 SNP was associated with a reduction in walking time (p = .016, Table 3). We observed a similar trend with improved functioning measured by SPPB, although this did not reach nominal significance (p = .065).

Table 3.

Association of the IL-18 Serum Level Altering SNP rs5744256 With Short Physical Performance Battery Scores and Walking Times in Participants Aged 65–80 Years in the InCHIANTI and Iowa-EPESE Studies

| TT |

Genotype TC |

CC |

Total |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Tested Physical Performance |

N | Mean (95% CI) |

N | Mean (95% CI) |

N | Mean (95% CI) |

N | Linear Regression Coefficient (95% CI)* |

p Value |

| InCHIANTI | Summary Physical Performance Battery | 445 | 10.48 (10.24–10.72) | 201 | 10.87 (10.59–11.15) | 28 | 10.96 (10.37–11.56) | 674 | 0.283 (−0.02 to 0.58) | .065 |

| 7-m walk times | 436 | 6.42 (6.17–6.79) | 198 | 5.93 (5.721–6.13) | 28 | 6.01 (5.46–6.57) | 662 | −0.038 (−0.07 to −0.01) | .016 | |

| Iowa-EPESE | Summary Physical Performance Battery | 557 | 8.45 (8.24–8.67) | 376 | 8.45 (8.18–8.73) | 64 | 9.22 (8.63–9.81) | 997 | 0.222 (−0.04 to 0.48) | .092 |

| 8-ft walk times | 556 | 3.99 (3.84–4.14) | 375 | 3.94 (3.75–4.12) | 64 | 3.49 (3.15–3.83) | 995 | −0.040 (−0.08 to −0.005) | .026 | |

Notes: All models were adjusted for age and sex, and Iowa models (which included only participants reporting being white) were adjusted for origin of parental families (known vs unknown): dependent variable logged.

IL-18 = Interleukin-18; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism; EPESE = Established Populations for Epidemiological Study of the Elderly; CI = confidence interval.

In the Iowa-EPESE study, we saw a similar trend with the C allele of rs5744256 associated with reduction in walking time (p = .026, Table 3). The SPPB score trended in the same direction but did not reach nominal significance (p = .092).

When data from the two studies were combined (using ranked data) the associations remained, even after adjustment for age, sex, study, and known family origin, in ordinal regression models. For the SPPB, the ordinal regression coefficient for the rs5744256 SNP was β = 0.1740 (95% CI, 0.0280–0.3200; p = .019). For ranked walk speeds in the two studies together, the adjusted association with rs5744256 had an ordinal regression coefficient of β = −0.2384 (95% CI, −0.3821 to −0.0947; p = .001).

Loss to follow-up over the first 6 years of the Iowa-EPESE study was strongly associated with disability at baseline, which could result in differential attrition of gene variants detrimental to functioning. We therefore did additional analyses restricted to those participants who reported being free of functional impairments at baseline. In this incident cohort (n = 510), the regression coefficient for the SNP walking time association was in the same direction but reduced, and not nominally significant (coefficient −0.015; p = .505).

Mendelian Randomization Using rs5744256

We next estimated the strength of the association between IL-18 serum concentrations (in the InCHIANTI data only) and walking time due to the rs5744256 SNP, thus excluding reverse causation and confounding. Using instrumental variables analyses (Table 4), we found that there was a significant association between IL-18 serum concentrations and walk time due to the three rs5744256 genotypes (linear regression coefficient =0.324; 95% CI, 0.050–0.598; p = .021). This is analogous to showing that the observed association between rs5744256 and functioning is consistent with the expected effect given the association between the SNP and IL-18 concentrations and the association between IL-18 concentrations and functioning. The estimate of the regression coefficient between IL-18 concentrations and walking speed using genotypes was larger than the observed regression coefficient (0.082; 95% CI, 0.029–0.135; p value for difference =.048). This difference may be due to chance or could reflect possible regression dilution bias caused by the error in the measurement of IL-18 concentrations.

Table 4.

Association of IL-18 Serum Levels (Log Transformed) With 7-m Walking Times (InCHIANTI Study Age Group 65–80 Years), in Simple Linear Regression and Instrumental Variable Models

| Outcome | Regression Coefficient* | 95% CI | p Value | Change With Doubling of IL-18 Serum Level* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear regression | 0.082 | 0.029–0.135 | .002 | 1.058 |

| Instrumental variable model (instrument = SNP rs5744256) | 0.324 | 0.050–0.598 | .021 | 1.252 |

Notes: IL-18 = Interleukin-18; CI = confidence interval; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism.

Test of equality of linear regression and instrumental variable estimates: p = .048.

Ratios of geometric means by a doubling in IL-18 serum level.

Discussion

In this study, we have tested three hypotheses on the relationships between IL-18 concentrations, IL-18 gene tagging SNPs, and functioning in younger old age. We have shown positive associations between higher IL-18 serum concentrations and tested physical functioning. We showed that the minor, C, allele of the rs5744256 SNP in IL-18 is associated with a 0.25 SD reduction in serum concentrations of IL-18 per allele and with better performance, based on walk tests in 65- to 80-year-olds. We showed that the effect on walk speed is consistent with the expected effect given the association between the SNP and IL-18 concentrations and the association between IL-18 concentrations and functioning. As reverse association between genotypes and functioning is very unlikely, this evidence suggests that IL-18 may be an active or causal factor in inflammation and age-related poor physical function. Our results are consistent across two studies. However, the association between the genotype and functioning does not reach genome-wide thresholds for significance, so further studies are needed to confirm this association.

The details of measurement of the SPPB and walking times differed between the InCHIANTI and Iowa-EPESE participants. To deal with this in pooled analyses we have ranked all scores within study, before combining them in ordinal regression models. This process should have removed distributional differences between the measures. The minor allele frequency for rs5744256 was higher in the Iowa-EPESE study than in the InCHIANTI study (44% vs 33%, respectively), and we therefore corrected for study in the pooled models. In the Iowa-EPESE study, all participants included in our analyses reported being “white” to a question on race, and the majority identified maternal and paternal family origins in Europe, although a limited group did not know these origins. Although the entire included sample is likely to have been of Caucasian origin, we have adjusted for this possible source of admixture. The finding of broadly consistent associations within two quite separate population studies also makes it unlikely that admixture could have biased the results.

Associations between serum markers and disease or functioning in observational studies always need to be viewed cautiously, as confounding and reverse causation are difficult to control in conventional analyses. Genetic variation is randomly inherited and is fixed at conception, and when such variation alters risk factor levels, these properties can be exploited to reduce confounding and reverse causation. The instrumental variable model presented has been used before for this purpose (14). In our study, the model clearly shows an un-confounded association of IL-18 concentrations with walk time when using IL-18 SNPs. If confirmed, this association indicates that IL-18 may play an active role in age-related physical decline.

The SNP associated with both IL-18 levels and altered functioning in old age is in intron 3 of the IL-18 gene and has no obvious function. Based on HapMapII data in Caucasians, the association could be due to nine other SNPs, including several outside of the IL-18 gene. It is likely that one or more of these SNPs alters IL-18 gene expression, and direct measurement of expression is needed. Previous in vitro experiments have shown IL-18 gene expression to be altered by two promoter polymorphisms, −607 (rs1946518) and −137 (rs187238) (28,29). The data from HapMap indicates that we have captured the −607 SNP with an r2 of 0.56 using rs1293344. This SNP was not associated with IL-18 levels (p = .11), and −607 is not in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the SNP we found is most strongly associated with levels (correlation, r2 = 0.14 with rs5744256). The −137 SNP is not in HapMap, and we have not analyzed it further. It therefore remains possible that there is further variation in the IL-18 gene that alters serum levels of IL-18.

Conclusion

There is mounting evidence that inflammation is a core process contributing to aging. IL-18 is a potent proinflammatory cytokine and is a good candidate for contributing to inflammation-mediated aging. We have analyzed common variation in the IL-18 gene, and found that a common allele is strongly correlated with IL-18 concentration and, through this, with altered physical functioning in early old age. If replicated, these results indicate that associations between IL-18 and physical functioning are unlikely to be due to confounding or reverse causation. IL-18 may be an active factor and not a by-product in age-related decline in physical functioning.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (NIH/NIA) Grant R01 AG24233-01, and by the Intramural Research Program, NIA, NIH. D. M. is supported by a National Health Service Executive National Public Health Career Scientist Award (Ref: PHCSA/00/002). The InCHIANTI study was supported as a “targeted project” (ICS 110.1\RS97.71) by the Italian Ministry of Health, by the National Institute on Aging (N01-AG-916413, N01-AG-821336, 263 MD 9164 13, and 263 MD 821336).

References

- 1.Hoshino T, Kawase Y, Okamoto M, et al. Cutting edge: IL-18-transgenic mice: in vivo evidence of a broad role for IL-18 in modulating immune function. J Immunol. 2001;166:7014–7018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JL, Carlquist JF. Cytokines, interleukin-18, and the genetic determinants of vascular inflammation. Circulation. 2005;112:620–623. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.554733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blankenberg S, Cambien F, Tiret L, et al. Interleukin-18 and the risk of coronary heart disease in European men: the Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction (PRIME) Circulation. 2003;108:2453–2459. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099509.76044.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liew FY, Wei XQ, McInnes IB. Role of interleukin 18 in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(suppl 2):48–50. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.suppl_2.ii48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sivakumar PV, Westrich GM, Kanaly S, et al. Interleukin 18 is a primary mediator of the inflammation associated with dextran sulphate sodium induced colitis: blocking interleukin 18 attenuates intestinal damage. Gut. 2002;50:812–820. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.6.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Izakovicova Holla L. Interleukin-18 in asthma and other allergies. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:1023–1025. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinarello CA, Fantuzzi G. Interleukin-18 and host defense against infection. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(suppl 2):S370–S384. doi: 10.1086/374751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felderhoff-Mueser U, Schmidt OI, Oberholzer A, Buhrer C, Stahel PF. IL-18: a key player in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration? Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caruso C, Lio D, Cavallone L, Franceschi C. Aging, longevity, inflammation, and cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1028:1–13. doi: 10.1196/annals.1322.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franceschi C, Olivieri F, Marchegiani F, et al. Genes involved in immune response/inflammation, IGF1/insulin pathway and response to oxidative stress play a major role in the genetics of human longevity: the lesson of centenarians. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinarello CA. Interleukin 1 and interleukin 18 as mediators of inflammation and the aging process. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:447S–455S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.447S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrucci L, Corsi A, Lauretani F, et al. The origins of age-related proinflammatory state. Blood. 2005;105:2294–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangemi S, Basile G, Merendino RA, et al. Increased circulating interleukin-18 levels in centenarians with no signs of vascular disease: another paradox of longevity? Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:669–672. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Timpson NJ, Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, et al. C-reactive protein and its role in metabolic syndrome: mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2005;366:1954–1959. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67786-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiret L, Godefroy T, Nicaud V, et al. Genetic analysis of the interleukin-18 system highlights the role of the interleukin-18 gene in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2005;112:643–650. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.519702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karasik D, Demissie S, Cupples LA, Kiel DP. Disentangling the genetic determinants of human aging: biological age as an alternative to the use of survival measures. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60A:574–587. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.5.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frederiksen H, Gaist D, Petersen HC, et al. Hand grip strength: a phenotype suitable for identifying genetic variants affecting mid- and late-life physical functioning. Genet Epidemiol. 2002;23:110–122. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmelli D, Kelly-Hayes M, Wolf PA, et al. The contribution of genetic influences to measures of lower-extremity function in older male twins. J Gerontol Biol Sci. 2000;55A:B49–B53. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.1.b49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenwood PM, Parasuraman R. Normal genetic variation, cognition, and aging. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2003;2:278–306. doi: 10.1177/1534582303260641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGue M, Christensen K. The heritability of level and rate-of-change in cognitive functioning in Danish twins aged 70 years and older. Exp Aging Res. 2002;28:435–451. doi: 10.1080/03610730290080416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, et al. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1618–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith GD, Ebrahim S. Mendelian randomization: prospects, potentials, and limitations. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:30–42. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2000;55:M221–M231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The Mini-Mental State Examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:922–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cornoni-Huntley J, Ostfeld AM, Taylor JO, et al. Established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly: study design and methodology. Aging (Milano) 1993;5:27–37. doi: 10.1007/BF03324123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenland S. An introduction to instrumental variables for epidemiologists. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:722–729. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.4.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giedraitis V, He B, Huang W, et al. Cloning and mutation analysis of the human IL-18 promoter: a possible role of polymorphisms in expression regulation. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;112:146–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang X, Cheung W, Heng CK, et al. Reduced transcriptional activity in individuals with IL-18 gene variants detected from functional but not association study. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]