Abstract

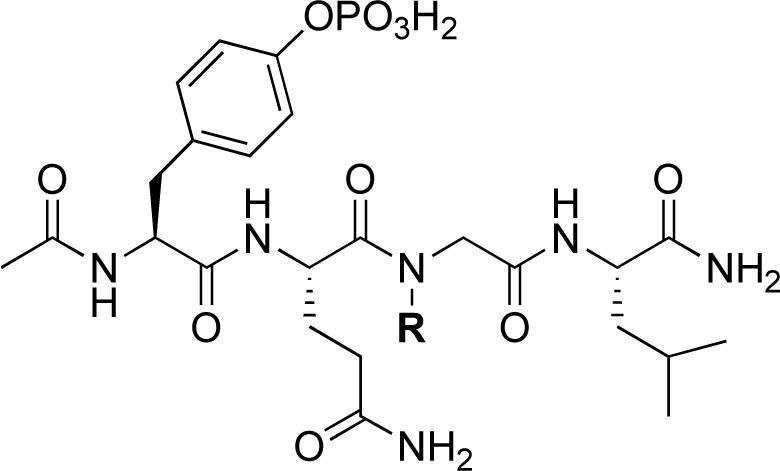

A fluorescence anisotropy (FA) competition – based Shc Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-binding was established using the high affinity fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-containing peptide, FITC-NH-(CH2)4-CO-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide (8; Kd = 0.35 μM). Examination of a series of open – chain bis-alkenylamide containing peptides, prepared as ring – closing metathesis precursors, showed that the highest affinities were obtained by replacement of the original Gly residue with Nα-substituted Gly (NSG) “peptoid” residues. This provided peptoid-peptide hybrids of the form, “Ac-pY-Q-[NSG]-L-amide.” Depending on the NSG substituent, certain of these hybrids exhibited up to 40 – fold higher Shc SH2 domain binding affinity than the parent Gly-containing peptide (IC50 = 248 μM), (for example, N-homo-allyl analogue 50; IC50 = 6 μM). To our knowledge, this work represents the first successful example of the application of peptoid-peptide hybrids in the design of SH2 domain-binding antagonists. These results could provide a foundation for further structural optimization of Shc SH2 domain-binding peptide mimetics.

Introduction

Disrupting protein-protein interactions is evolving as a challenging but potentially rewarding approach to therapeutic development.1 Src homology 2 (SH2) domains facilitate the formation of signaling complexes by mediating the recognition and binding to phosphotyrosyl (pTyr)-containing sequences,2-4 and SH2 domain-binding antagonists may down regulate protein-tyrosine kinase signaling in a fashion that is complimentary to kinase-directed inhibitors.5,6 Although significant effort has focused on development of p56lck, Src and growth factor receptor bound 2 (Grb2) SH2 domain-binding antagonists,7-11 relatively little has been reported on agents directed against the Shc SH2 domain.12,13 Members of the Shc family of non-catalytic SH2 domain-containing adapter proteins serve as transforming elements involved with mitogenic signal transduction,14,15 and they have been shown to be essential for induction of the pro-angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).16 Pathways downstream of Shc or Grb2 have also been shown to be critical for transformation and metastasis.17, 18 The importance of Shc in Ras activation pathways has made antagonists of Shc signaling potentially attractive therapeutic targets. The current report details unexpected finding of potent inhibitory motifs that grew out of unsuccessful attempts to develop macrocyclic Shc SH2 domain binding inhibitors.

Results and Discussion

Development of Shc SH2 domain – binding fluorescence anisotropy assays: Identification of a high affinity fluorescein isothiocyanate – containing peptide

Previous analyses of Shc SH2 domain – binding constants have relied on relatively labor – intensive NMR or surface plasmon resonance techniques,13 Assays based on fluorescence anisotropy (FA) afford attractive alternatives for determining binding constants, but they can be limited by the need to append fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) to every peptide examined. However, this requirement can be circumvented by the availability of a high affinity reference FITC-containing peptide that can be used in FA assays to determine affinities of non-FITC labeled peptides by competition techniques. Therefore, our first objective of the current study was to identify a reference FITC-containing reference peptide having high Shc SH2 domain binding affinity for use in FA competition assays.

Modeling based on NMR solution studies of the ζ chain-T cell receptor-derived 14 – mer peptide “GHDGLpYQGLSTATK” (1) bound to the Shc SH2 domain,19,20 indicated that significant interactions only occur for residues “pYQGL.” Accordingly, the slightly longer “LpYQGLS” sequence (2) was used as a starting point for structural exploration of FITC-containing peptides. Initial studies were conducted to determine the optimal introduction of an N-terminal FITC group using a variety of spacer lengths (3 − 14, Table 1). Direct N-terminal attachment of the FITC group (3) resulted in a complete loss of binding affinity. However, deletion of the N-terminal Leu residue from 2 prior to addition of the FITC tag gave high affinity (4, Kd ≈ 12 μM). Adding the FITC label to the latter “pY-Q-G-L-S-amide” sequence by means of a series of progressively longer amino-n-alkyl carboxylic acid amide linkers (5 − 9) gave the highest affinity using a pentanoyl chain (8, Kd = 0.35 μM). The best affinities from a similar series of FITC-containing peptides prepared using the longer “L-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide” sequence (10 − 14) were approximately 50-fold less potent. Replacement of the FITC group in 8 with N-acetyl (15, IC50 = 158 μM) resulted in a significant loss of binding affinity as determined using a FA competition assay against 8 as the reference peptide. This indicated that the FITC moiety in 8 contributes substantially to the binding affinity.

Table 1.

Shc SH2 domain-binding affinities determined using a fluorescence anisotropy assay.

| No. | Sequence | Kd ± s.d. (μM)a |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | FITC-L-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | n.b.b |

| 4 | FITC-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | 12.4 ± 2.6 |

| 5 | FITC-NH-(CH2)-CO-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | n.b. |

| 6 | FITC-NH-(CH2)2-CO-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | 1.09 ± 0.04 |

| 7 | FITC-NH-(CH2)3-CO-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | 7.2 ± 0.2 |

| 8 | FITC-NH-(CH2)4-CO-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | 0.35 ± 0.13 |

| 9 | FITC-NH-(CH2)5-CO-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | 4.7 ± 0.1 |

| 10 | FITC-NH-(CH2) -CO-L-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | n.b. |

| 11 | FITC-NH-(CH2)2-CO-L-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | 7.6 ± 0.5 |

| 12 | FITC-NH-(CH2)3-CO-L-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | 8.6 ± 0.3 |

| 13 | FITC-NH-(CH2)4-CO-L-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | 8.9 ± 0.3 |

| 14 | FITC-NH-(CH2)5-CO-L-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | n.b. |

| 15 | Ac-NH-(CH2)4-CO-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide | 158 ± 10c |

Except as noted, determined by fluorescene anisotropy techniques as described in the Experiment Section.

No binding.

IC50 values determined by FA competition experiments using peptide 8 as the reference peptide.

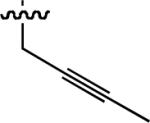

To examine the possible effects in binding affinity of the linker structure other than chain length, a series analogues was prepared based on the FITC-X-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide sequence (16 − 28, Table 2). These more structurally complex linkers could potentially affect binding affinity by interacting directly with the SH2 domain protein, or by positioning the FITC ring system. Most of the peptides exhibited binding affinities in the range 5 − 25 μM. However, peptides 24 (Kd ≈ 0.8 μM) and 27 (Kd ≈ 0.5 μM) exhibited approximately 10-fold higher affinities than other members of the series. Of particular note was the 50-fold higher affinity of 27 relative to its trans-isomer (26). Since none of the peptides in Table 2 exhibited higher affinity than the original FITC – containing 8, this latter peptide was chosen for use as a reference in subsequent FA competition assays.

Table 2.

Shc SH2 domain-binding affinities for FITC-X-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide.

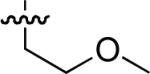

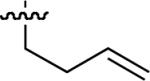

| No | Spacer (X) | Kd ± s.d (μM)a | No. | Spacer (X) | Kd ± s.d (μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

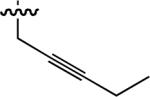

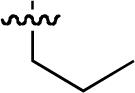

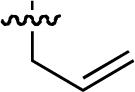

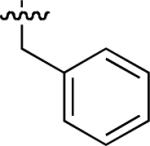

| 16 |  |

8.6 ± 0.9 | 23 |  |

5.0 ± 0.9 |

| 17 |  |

9.0 ± 3.2 | 24 |  |

0.77 ± 0.04 |

| 18 |  |

5.3 ± 0.6 | 25 |  |

14.2 ± 2.1 |

| 19 |  |

9.5 ± 1.1 | 26 |  |

25.4 ± 1.6 |

| 20 |  |

18.0 ± 0.8 | 27 |  |

0.5 ± 0.3 |

| 21 |  |

23.9 ± 2.0 | 28 |  |

12.3 ± 2.3 |

| 22 |  |

poor |

Determined by a direct binding fluorescence anisotropy assay as described in the experimental procedures.

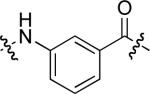

Blockade of Shc binding to c-Met tyrosine kinase in whole cells

In order to confirm that the highest affinity FITC-labeled peptide (8) is capable of binding to the Shc SH2 domain in a physiologically-relevant manner, studies were performed that examined the ability of 8 to inhibit the binding of intracellular Shc protein to the cytoplasmic domain of the c-Met protein-tyrosine kinase in intact human mammary B5/589 cells, which express high levels of c-Met. For this purpose, Universal PEG Novatag® Resin21 was used to prepare peptides 29 and 30 (Figure 1), which contained the membrane carrier peptide sequences, “RRRRRRRR”23 and “RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK”23 attached to the C-terminus of 8 by means of a polyethylene glycol (PEG) spacer. The Shc SH2 doman-binding affinities of 29 and 30 as determined by extracellular FA competition assays were Kd = 5 μM and 1 μM, respectively. Following incubation of cells with the peptides in the presence and absence of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF, a ligand for c-Met receptor), the cells were washed, lysed and binding of Shc to activated c-Met was measured as described in the Material and Methods. At 10 μM concentration, both 29 and 30 were able to achieve a consistent blockade of intracellular binding of Shc to c-Met (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Inhibition by peptides 29 (Panel A) and 30 (Panel B) of binding of Shc to hepatocyte growth factor receptor (c-Met) tyrosine kinase in intact B5/589 cells as described in Experimental Section. Cells were incubated for 1 h in presence (10 μM) or absence (0 μM) of the indicated peptides, then untreated (control) or briefly stimulated with HGF (+HGF). Cells were lysed and the amount of Shc bound to c-Met determined (upper panels) as well as the amount c-Met recovered (lower panels).

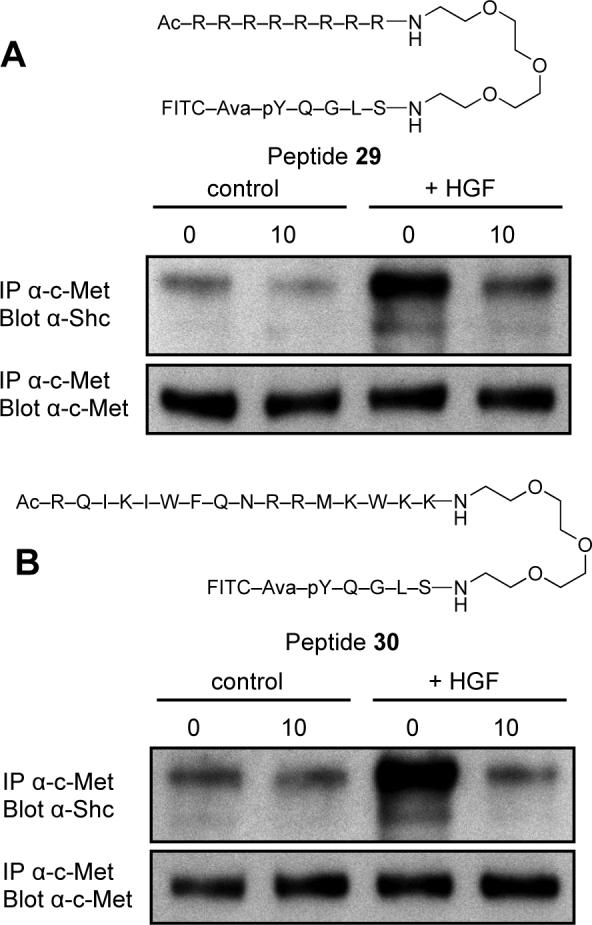

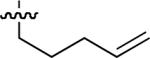

Examination of Shc SH2 domain – binding affinties of N-alkenyl – containing peptides (31 − 44) designed as ring – closing metathesis precursors

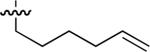

We had previously shown that induction of conformational constraint through macrocyclization using ring-closing metathesis (RCM)24 could improve the binding affinity of Grb2 SH2 domain-binding peptides.25 In the current study we performed molecular modeling experiments to explore the potential utility of RCM macrocyclization in the design of Shc SH2 domain – binding peptides. However, these modeling studies failed to identify obvious macrocyclic candidates. None-the-less, we undertook work directed at the preparation of a library of macrocycles. This was intended as an empirical alternative to a “structure – based design” approach. For this purpose, two series of peptides were prepared, predicated on the sequences Ac-pY-Q-G-L-S-NHR and Ac-pY-Q-G-L-NHR (A and B, respectively, Table 3), where R = allyl and homoallyl. For each series of peptides, additional N-allyl groups were placed at various nitrogen positions within the peptide backbone to form bis – alkenyl open – chain RCM precursors. Shc SH2 domain binding affinities of these putative precursors were determined prior to macrocyclization studies.

Table 3.

Shc SH2 domain-binding affinities of bis N-olefin containing peptides.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide A Analogues | Peptide B Analogues | |||||||

| No. | Positiona,b | n | IC50 ± s.d. (μM)c | No. | Positiona,b | n | IC50 ± s.d. (μM)c | |

| 31 | 0 | 1 | 189 ± 15 | 38 | 0 | 1 | 91 ± 12 | |

| 32 | 1 | 1 | 353 ± 34 | 39 | 1 | 1 | 81 ± 6 | |

| 33 | 2 | 1 | 48 ± 2 | 40 | 2 | 1 | 47 ± 2 | |

| 34 | 3 | 1 | 41 ± 7 | 41 | 3 | 1 | 450 ± 38 | |

| 35 | 0 | 2 | 165 ± 4 | 42 | 0 | 2 | 84 ± 4 | |

| 36 | 1 | 2 | 89 ± 5 | 43 | 1 | 2 | 84 ± 6 | |

| 37 | 2 | 2 | 8 ± 2 | 44 | 2 | 2 | 14 ± 3 | |

Site of N-allyl substitution.

A designation of “0” indicates the lack of N-allyl substitution.

Determined by a fluorescence anisotropy based competition assay using peptide 8 as a reference as described in the experimental procedures.

In the A series, the highest affinities were obtained by N-allylation of the Gln – Gly amide nitrogen, with the N-terminal homoallyl peptide (37; IC50 = 8 μM) exhibiting higher affinity than the corresponding N-terminal allyl congener (33; IC50 = 48 μM). Placement of the backbone N – alkenyl group at other positions in the peptide chain (positions 1 or 3, Table 3) or deletion entirely (peptides 31 and 35) gave generally lower affinities. Similar results were found in the B series. The data presented in Table 3 were of note in that the highest affinities were derived by replacing the original Gly residues with Nα-substituted Glycines (NSG). The NSG groups are the fundamental units of the “peptoid” class of peptide mimetics and peptides such as 37 and 44 represent peptoid-peptide hybrids. To our knowledge, this is the first identification of peptoid-peptide hybrids as high affinity SH2 domain-binding inhibitors.

As indicated above, the bis-alkenylamine – containing peptides were originally intended as precursors for the preparation of macrocyclic peptide mimetics. However, RCM macrocyclization studies carried out using 2nd generation Grubbs catalyst26 were largely unsuccessful and only a small number of ring – closed products could be obtained. Consistent with preliminary molecular modeling studies that failed to predict binding enhancement through macrocyclization, none of the obtained final cyclic peptides showed significantly enhanced affinity (data not shown), and further work with peptide macrocyclization was not pursued.

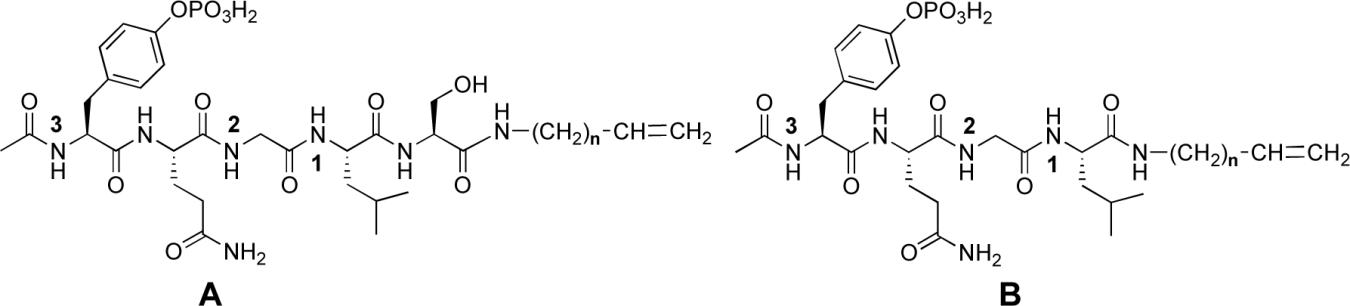

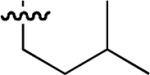

Examination of N-substituted glycine residues in peptides lacking C-terminal alkenylamide substituents

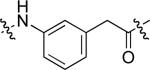

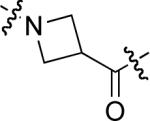

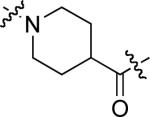

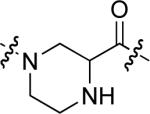

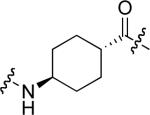

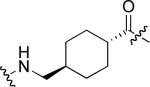

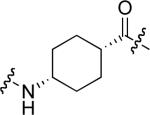

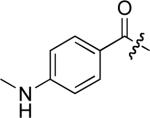

Because N-alkenylation of the Gln – Gly amide nitrogen appeared to be advantageous in the open-chain series bearing C-terminal alkenylamides (for example 37 and 44), studies were undertaken to examine an array of NSG residues in a simplified peptide platform lacking any C-terminal carboxamide subsituents (Table 4). For the parent non-substituted Gly-containing peptides 38 and 42, deletion of the C-terminal allyl and homoallyl amide functionalities respectively gave “Ac-pY-Q-G-L-amide”, which resulted in an approximate 2 − 3 fold loss of binding affinity (45, Table 4; IC50 = 248 μM). Relative to 45, addition of a C-terminal Ser residue (“Ac-pY-Q-G-L-S-amide”), resulted in an approximate doubling of binding affinity (IC50 = 112.5 ± 0.7 μM), while shortening 45 by removing the N-terminal Leu residue abrogated nearly all binding affinity (“Ac-pY-Q-G-amide” IC50 > 500 μM). Therefore, peptide 45 was taken as a starting point for peptoid – peptide synthesis, because it represented a balance between size and binding affinity.

Table 4.

Shc SH2 domain-binding affinities N-alkylglycine containing peptides.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

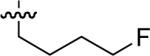

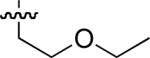

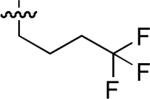

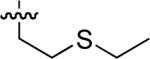

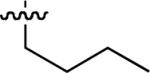

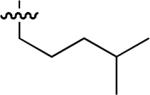

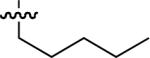

| No | R | IC50 ± s.d (μM)a | No | R | IC50 ± s.d (μM)a | No. | R | IC50 ± s.d (μM)a |

| 45 |  |

248 ± 5 | 52 |  |

83 ± 3 | 59 |  |

16 ± 4 |

| 46 |  |

19 ± 0.5 | 53 |  |

17 ± 3 | 60 |  |

17 ± 3 |

| 47 |  |

25.7 ± 0.7 | 54 |  |

40 ± 6 | 61 |  |

33 ± 1 |

| 48 |  |

26.6 ± 0.7 | 55 |  |

23 ± 3 | 62 |  |

34 ± 1 |

| 49 |  |

8.9 ± 0.1 | 56 |  |

56 ± 13 | 63 | 20 ± 3 | |

| 50 |  |

6.0 ± 0.2 | 57 |  |

29 ± 7 | 64 |  |

14 ± 0 |

| 51 |  |

18.9 ± 0.3 | 58 |  |

10 ± 0.7 | 65 | 44 ± 2 | |

Determined by a fluorescence anisotropy based competition assay using peptide 8 as the reference peptide as described in the experimental procedures.

Starting from 45, formation of NSG residues by alkylation of the Gln – Gly amide bond enhanced binding affinity by an order of magnitude or more (Table 4). The highest affinities were obtained with 4 – carbon linear chains (n-butyl (49), IC50 = 8.9 μM and homoallyl (50), IC50 = 6.0 μM). Increasing chain length beyond 4 units resulted in a loss of affinity (n-pentyl (58) IC50 = 10 μM and n-hexyl (63), IC50 = 20 μM), as did insertion of heteroatoms (oxygen (56), IC50 = 56 μM; sulfur (62), IC50 = 34 μM or nitrogen (65), IC50 = 44 μM). Although an approximate 10 – fold loss of potency was incurred by the original deletion of C-terminal alkenylamide functionality, subsequent introduction of a homoallyl – NSG residue (50) more than compensated for the potency loss to yield a peptide that exibited twice the affinity of the parent bis – homoallyl – containing 44.

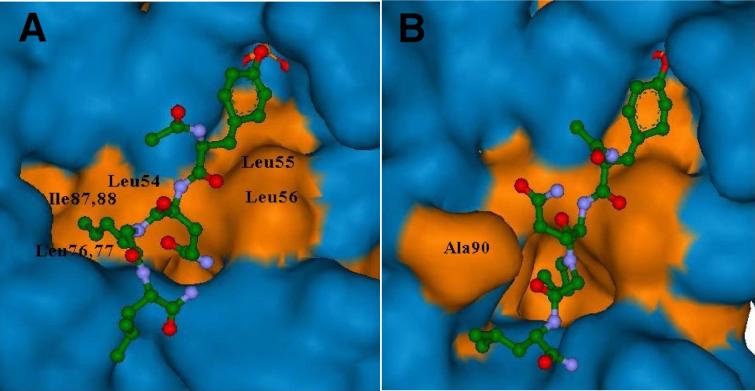

Molecular Modeling

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of N-homoallyl-containing 50 bound to the Shc SH2 domain protein were conducted. The two conformations with the two lowest energy complexes are depicted in Figure 2. Subjecting these complexes to FEB (free energy of binding) calculations using the program eMBrAcE developed by Schrödinger, showed that both complexes were energetically similar (Conformation A: −21957.656 KJ/mol; Conformation B: −21957.133 KJ/mol). NMR and crystallographic studies have previously indicated that interactions of peptide ligands with Shc SH2 domain protein can vary significantly.19,27 Therefore it was not surprising that binding of peptide 50 differed from that reported for the 14 – mer T-cell derived parent peptide (1).19 For peptide 50, the slightly more favorable Conformation A, (Figure 2), has the N-homoallyl group interacting with a hydrophobic pocket created by residues Leu59, Leu76 and Ile87, Ile88. In Conformation B, the Ala90 residue has shifted position allowing the N-homoallyl group to bind within a newly created hydrophobic pocket. In both conformations, the homoallyl group makes significant binding interactions that may explain the relatively high affinity of the peptoid – peptide hybrids.

Figure 2.

Hydrophobic and hydrophilic surface maps for two confomations (A and B) of peptide ligand 50 binding to Shc SH2 domain formed after 10 ps of molecular dynamics simulations. The coloring of atoms is: carbon – green; nitrogen – blue; oxygen – red. The N-homoallyl group interacts with hydrophobic pockets. Hydrophobic and hydrophilic surface maps are colored in orange and blue, respectively. Peptide 50 is displayed in ball and stick representation.

Conclusions

Using a FA based competition assay based on the high affinity FITC-containing peptide 8, evaluation of a number of bis – alkenylamide peptides for Shc SH2 domain-binding affinity, resulted in the discovery of pTyr+2 N-alkyl-Gly residues as favorable structural motifs. Deletion of the C – terminal alkenyl amide could be achieved without overall loss of binding affinity. Molecular modeling studies identified specific pockets within the protein surface that appear to afford regions of hydrophobic interactions with the NSG side chain. These findings represent the first examples of peptoid – peptide hybrids as preferred SH2 domain – binding motifs. As such, this work could provide the foundation for further structure-based optimization of Shc SH2 domain-binding peptide mimetics.

Experimental Section

Preparation of Shc SH2 Domain Protein

Shc protein was prepared using previously published protocols.28 A total of 1.2 mg of lyophilized Shc protein was resuspended in a 17 μL of 100% (v/v) dimtheyl sulphoxide and then 159 μL of a buffer solution (BS) consisting of 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.5 was added for a stock of 500 μM of protein.

Steady State Fluorescence Anisotropy Assays

Aliquots of a solution of 5 nM of peptide labeled with fluorescein at the N-terminus in 1 × BS, 10% (v/v) dimtheyl sulphoxide (DMSO) were placed in 96 well Costar polypropylene plates (Corning, NY). Shc protein was serially diluted in the peptides with a starting concentration of 100 μM. 40 μL was removed and transferred into 384-well Costar polypropylene plates (Corning, NY). Samples were excited at 485 nm and the emission intensities at 535nm from the parallel and perpendicular planes were measured using a Tecan Ultra plate reader (Durham, NC).

Curves were fit assuming a single binding site per peptide, using the relation:

| (1) |

where An(C) is the measured anisotropy as a function of concentration, Lt is the peptide concentration, Anfree is the anisotropy of unbound peptide, Anbound is the anisotropy of the completely bound peptide solution, R is the ratio of the fluorescence intensity of saturated bound peptide relative to free peptide, C is the protein concentration, and Kd is the measured dissociation constant resulting from the fit.

Fluorescence Anisotropy Competition Assays

A complex of 2 μM Shc and 10 nM peptide 8 in 1 × BS, 10% (v/v) DMSO was placed in 96 well Costar polypropylene plates (Corning, NY). Unlabeled competitor peptides were serially diluted into the complex with starting concentrations of 500 μM. A total of 40 μL was removed and transferred into 384-well Costar polypropylene plates (Corning, NY). Samples were excited at 485 nm and the emission intensities at 535 nm from the parallel and perpendicular planes were measured using a Tecan Ultra plate reader (Durham, NC). To estimate the IC50 values for these competition experiments, the fractional binding of the competitor ligand was determined from the binding part of the anisotropy signal using estimates of the maximum and minimum anisotropy signal.29 The fractional binding signal is described using a least squares spline approximate.30 Three knots in a spline of order three were used with the value at which the spline achieved one half being taken as an estimate of the IC50 value.

Inhibition of Shc SH2 Domain Binding to Cytoplasmic c-Met Tyrosine Kinase Receptor in Intact Cells

Intact B5/589 human mammary epithelial cells were serum-deprived (48 h), then incubated (1 h) in presence or absence of peptides 29 and 30. Cells were treated with hepatocyte growth factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; 50 ng/mL; 20 minutes) and then lysed in cold buffer (pH 7.4) containing non-ionic detergent and protease and phosphatase inhibitors. After incubation with a biotin-tagged, affinity-purified c-Met antibody (BAF358, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; 1 h on ice), immunocomplexes were captured using a streptavidin resin (Pierce, Rockford, IL, 1 h at 4 °C with rotation). The beads were washed with cold lysis buffer (3 ×), and samples were eluted with SDS sample buffer and resolved by SDS - PAGE prior to electrophoretic transfer to PVDF membranes (Immobilon P; Millipore, Billerica, MA). Chemiluminescent detection of anti-Shc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or anti-c-Met (AF276, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) antibodies was performed using ECL (GE Healthcare).

Molecular Modeling

Calculations were performed on Silicon Graphics computer running the IRIX operating system. All simulations were performed using the molecular modeling tools available within Macromodel 9.1 (Schrödinger Inc.). The peptide GHDGLyQGLSTATK (1) extracted from the Shc SH2 domain NMR structure (PDB code 1TCE) was used as a starting geometry for the modeling study. The structure of the bound ligand was modified using the 3D-sketcher tools available within Macromodel 9.1 to yield initial structures of peptide 50 complexed with the protein. The resulting protein-ligand complex was then subjected to minimization using the OPLS2005 method until a gradient convergence threshold of 0.05 was reached. This was followed by 10 ps of equilibration and 50 ps of molecular dynamics simulation using the OPLS2005 force field. During minimization, the phosphotyrosine and all atoms of the protein were held fixed. Two bound conformations of 50 were obtained and subjected to molecular dynamics simulations, during which the phosphotyrosine and all protein residues were held fixed except for those within a 10 Å sphere around the ligand. A total of 100 structures were saved for each simulation and the two conformations with the two lowest energy complexes are depicted in Figure 2. These two complexes were subjected to FEB (free energy of binding) calculations using the program eMBrAcE developed by Schrödinger. Both complexes were energetically similar (Conformation A: −21957.656 KJ/mol; Conformation B: −21957.133 KJ/mol).

General Synthetic Procedures

Except where noted, solid-phase peptide synthesis was performed using NovaSyn® TGR resin (Novabiochem, Inc., catalog number 01−64−0060) in 5 or 10 mL disposable polypropylene columns (Pierce) fitted with porous polyethylene filter discs. Resin mixing was achieved by means of 360° rotation on a Barnstead-Thermolyne Labquake™ shaker. Protected-peptide resins were manually constructed using Fmoc-based solid-phase protocols. Trityl protection was employed for Gln and Ser side-chain protection and tert-butyl was used to protect the Tyr 4’-hydroxyl. The pTyr residue was incorporated in its PO(NMe2)2 form. Fmoc amino acids were coupled in NMP by treatment with Fmoc amino acid (5 equivalents) and coupling reagents [DIPCDI (5 equivalents)/HOBt (5 equivalents) for 2 h; PyBroP (5 equivalents)/DIPEA (10 equivalents) for 2 h. Double couplings were used for secondary amines. After completion of the coupling reactions, resins were washed (DMF, 6 ×), then Fmoc deprotection was achieved using 20% piperidine in DMF (20 min) followed by DMF wash (6 ×). Final N-terminal acetylation was performed in DMF by treating with 1-acetylimidazole (for primary amines) or acetic anhydride/DIPEA (for secondary amines). Introduction of N-terminal fluorescein was achieved by reaction of deprotected resins with fluorescein isothiocyanate (“isomer I”, Sigma Aldrich Corp) in DMF containing 3 equivalents of diisopropylamine (shaken overnight shielded from light). Finished resins were washed with DMF, methanol, dichloromethane and ether then dried under vacuum. Peptides and peptoid – peptide hybrids were cleaved from the resin by treatment (3 h) with 5 mL of trifluoroacetic acid : EDT : H2O (76 : 20 : 4). An additional 0.5 mL of H2O was added mixing continued (overnight). Resin was removed by filtration and the filtrate was concentrated under vacuum, and crude peptide precipitated by the addition of diethyl ether and the precipitate was washed with diethyl ether (2 ×). The resulting solids were dissolved in aqueous acetonitrile and purified by reverse phase preparative HPLC using a Phenomenex C18 column (21.20 mm dia × 250 mm) with a linear gradient from 0% aqueous acetonitrile (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) to 100% acetonitrile (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) over 30 minutes at a flow rate of 10.0 mL/minute. Lyophilization provided products as amorphous solids.

FITC-NH-(CH2)4-CO-pTyr-Gln-Gly-Leu-Ser-amide (8)

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.09 (s, 1H), 9.93 (s, 1H), 8.25 (br, 1H), 8.15 (d, 1H), 8.06 (t, 1H), 7.93 (d, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 4Hz,1H), 7.73 (d, J = 4Hz, 1H), 7.17 (d, 1H), 7.11 (d, 1H), 7.01 (d, J = 4 Hz, 2H), 6.73 (br, 1H), 6.62 (d, 2H), 6.54−6.50 (m, 3H), 4.50−4.45 (m, 1H), 4.33−4.27 (m, 1H), 4.18 (dd, J1 = 8Hz, J2 = 4Hz, 1H), 4.13−4.10 (m, 1H), 3.76−3.67 (m, 2H), 3.53−3.46 (m, 2H), 3.39 (s, 2H), 2.98 (d, J = 8Hz, 1H), 2.68−2.62 (m, 1H), 2.06 (dd, J1 = 4Hz, J2 = 4Hz, 4H), 1.88−1.83 (m, 1H), 1.77−1.70 (m, 1H), 1.51−1.59 (m, 1H), 1.46−1.37 (m, 2H), 0.82 (d, J = 4Hz, 3H), 0.79 (d, J = 8Hz, 3H). MALDI-MS calcd for C51H60N9O17PS : 1134.11; found 1134.82.

FITC-[3-aminomethylbenzoyl]- pTyr-Gln-Gly-Leu-Ser-amide (23)

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.11 (s, 1H), 10.07 (s, 1H), 8.53 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 8Hz, 1H), 8.25 (s, 1H), 8.15 (t, J = 8Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d, 1H), 7.86 (d, 1H), 7.76 7.79 (m, 3H), 7.41 (d, J = 8Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 8Hz, 2H), 7.25 (br, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 4Hz, 2H), 7.07 (s, 1H), 6.76 (br, 1H), 6.68 (d, J = 4Hz, 2H), 6.58 (s, 1H), 6.55 (d, J = 4Hz, 2H), 4.84 (d, J = 4Hz, 2H), 4.72−4.66 (m, 1H), 4.38−4.25 (m, 2H), 4.17 (dd, J1 = 4Hz, J2 = 8Hz, 1H), 3.77 (d, 1H), 3.73 (d, 1H), 3.60 (t, J = 4Hz, 2H), 3.51 (s, 2H), 3.13 (d, J = 4Hz, 1H), 2.96 (t, J = 16Hz, 1H), 2.66−2.67 (m, 1H), 2.33−2.32 (m, 1H), 2.14 (t, J = 8Hz, 2H), 1.93−1.90 (m, 1H), 1.82−1.77 (m, 1H), 1.62−1.57 (m, 1H), 1.48 (br, 1H), 0.87 (d, J = 4Hz, 3H), 0.84 (d, J = 2Hz, 3H). MALDI-MS calcd for C54H58N9O17PS : 1168.13; found 1168.71.

Peptides Bearing C-Terminal N-Alkenylamides (31 − 65)

Peptides bearing C-terminal N-alkenylamides were prepared by adding the appropriate N-alkenyl amine (10 equivalents) and NaBH(OAc)3 (10 equivalents) to a suspension of 4-(4-formyl)-3-methoxyphenoxy)butyryl-NovaGel HL resin (Novabiochem, Inc.) in dry 1,2-dichloroethane/trimethyl orthoformate (2:1) solution, followed by mixing at room temperature (12 h). The resin was washed successively with DMF, 10% iPr2NEt/DMF, and DMF. Sequential coupling of amino acids was then achieved according to the general synthetic procedures outlined above. For peptides bearing Nα-alkenyl or Nα-alkyl residues, introduction of Nα-alkenyl and Nα alkyl groups was conducted on solid-phase resin by reaction of the corresponding N-terminally deprotected peptide with the appropriate alkenyl or alkyl bromide (1.2 equivalents) and powdered K2CO3 in anhydrous DMF at room temperature (overnight). Resins were washed with DMF (2 ×); 50% aqueous MeOH (5 ×) and CH2Cl2 (3 ×), followed by coupling of remaining amino acid residues. Cleavage of final peptides from the resin afforded side chain – deprotected peptide products, which were purified by reverse phase preparative HPLC.

Ac- pTyr-Gln-Gly(N-allyl)-Leu-NH(homoallyl) (44)

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.28−8.20 (dd, J = 8, 12Hz, 1H), 7.97−7.91 (m, 2H), 7.20 (d, 1H), 7.09−7.05 (m, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 8Hz, 2H), 5.75−5.56 (m, 2H), 5.16−5.08 (m, 1H), 5.04−5.01 (m, 1H), 4.96−4.91 (m, 1H), 4.65−4.61 (m, 1H), 4.47−4.44 (m, 2H), 4.18−4.16 (m, 2H), 4.06−4.02 (m, 2H), 3.63−3.55 (m, 2H), 3.12 (s, 1H), 3.10−2.99 (m, 1H), 2.65−2.62 (m, 1H), 2.04−1.98 (m, 1H), 1.73 (s, 3H), 1.53−1.46 (m, 1H), 1.40−1.38 (m, 2H), 0.82 (d, J = 4Hz, 3H), 0.77 (d, J = 8Hz, 3H). MALDI – MS calcd for C31H47N6O10P: 694.71; found 717.25.

Ac-pTyr-Gln-Gly(N-ethyl)-Leu-amide (46)

1H NMR (400MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.05(d, J = 8Hz, 2H), 6.98(d, J = 8Hz, 2H), 6.91 (br, 2H), 4.65−4.64 (m, 1H), 4.47−4.11 (q, J = 8Hz, 2H), 4.09−4.07 (m, 1H), 3.68−3.62 (m, 1H), 3.55−3.52 (m, 1H), 3.26−3.19 (m, 2H), 2.85−2.83 (m, 1H), 2.65−2.62 (m, 2H), 2.33−2.32 (m, 1H), 2.08−2.06 (m, 2H), 1.93 (d, J = 8Hz, 1H), 1.76 (d, 2H), 1.74 (s, 3H), 1.55−1.53 (m, 1H), 1.07 (t, J = 8Hz, 3H), 0.88−0.87 (m, 1H), 0.84 (d, J = 4Hz, 3H), 0.78 (d, J = 4Hz, 3H). MALDI – MS calcd for C26H41N6O10P: 628.61; found 650.52.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Appreciation is expressed to Dr. Oleg Chertov for purification of Shc SH2 domain protein. The Work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Center for Cancer Research, NCI-Frederick and the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Abbreviations

- FA

fluorescence anisotropy

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- SH2

Src homology 2

- NSG

Nα-substituted glycine

- pTyr

phosphotyrosyl

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- Grb2

growth factor receptor bound 2

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- RCM

ring-closing metathesis

- FEB

free energy of binding

- NMP

N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone

- DIPCDI

N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide

- HOBT

1-hydroxybenzotriazole

- PyBOP

(Benzotriazol-1-yloxy)tripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- EDT

1,2-ethanedithiol

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Mass spectral data for peptide products. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Wells JA, McClendon CL. Reaching for high-hanging fruit in drug discovery at protein-protein interfaces. Nature. 2007;450:1001–1009. doi: 10.1038/nature06526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradshaw JM, Waksman G. Molecular recognition by SH2 domains. Advances in Protein Chemistry (Protein Modules and Protein-Protein Interaction) 2003;61:161–210. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)61005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawson T. Specificity in signal transduction: From phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions to complex cellular systems. Cell. 2004;116:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pawson T, Gish GD, Nash P. The SH2 domain: a prototype for protein interaction modules. Modular Protein Domains. 2005:5–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladbury JE. Protein-protein recognition in phosphotyrosine-mediated intracellular signaling. Protein Reviews (Proteomics and Protein-Protein Interactions) 2005;3:165–184. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Machida K, Mayer BJ. The SH2 domain: versatile signaling module and pharmaceutical target. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (Proteins and Proteomics) 2005;1747:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broadbridge RJ, Sharma RP. The Src homology-2 domains (SH2 domains) of the protein tyrosine kinase p56lck: structure, mechanism and drug design. Curr. Drug Targets. 2000;1:365–386. doi: 10.2174/1389450003349074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shakespeare WC. SH2 domain inhibition: a problem solved? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2001;5:409–415. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metcalf CA, III, Sawyer T. Src homology-2 domains and structure-based, small-molecule library approaches to drug discovery. Drug Discovery Strategies and Methods. 2004:23–59. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Echeverria C. Inhibitors of signaling interfaces: targeting Src homology 2 domains in drug discovery. Protein Tyrosine Kinases. 2006:31–52. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke TR., Jr. Development of Grb2 SH2 domain signaling antagonists: a potential new class of antiproliferative agents. Int. J. Pept. Res. Therap. 2006;12:33–48. doi: 10.1007/s10989-006-9014-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batzer AG, Rotin D, Urena JM, Skolnik EY, Schlessinger J. Hierarchy of binding sites for Grb2 and Shc on the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:5192–201. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou MM, Harlan JE, Wade WS, Crosby S, Ravichandran KS, Burakoff SJ, Fesik SW. Binding affinities of tyrosine-phosphorylated peptides to the COOH-terminal SH2 and NH2-terminal phosphotyrosine binding domains of Shc. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:31119–31123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelicci G, Lanfrancone L, Grignani F, McGlade J, Cavallo F, Forni G, Nicoletti I, Grignani F, Pawson T, Pelicci PG. A novel transforming protein (SHC) with an SH2 domain is implicated in mitogenic signal transduction. Cell. 1992;70:93–104. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90536-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravichandran KS. Signaling via Shc family adapter proteins. Oncogene. 2001;20:6322–6330. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saucier C, Khoury H, Lai KMV, Peschard P, Dankort D, Naujokas MA, Holash J, Yancopoulos GD, Muller WJ, Pawson T, Park M. The Shc adaptor protein is critical for VEGF induction by Met/HGF and ErbB2 receptors and for early onset of tumor angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:2345–2350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308065101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saucier C, Papavasiliou V, Palazzo A, Naujokas MA, Kremer R, Park M. Use of signal specific receptor tyrosine kinase oncoproteins reveals that pathways downstream from Grb2 or Shc are sufficient for cell transformation and metastasis. Oncogene. 2002;21:1800–1811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ursini-Siegel J, Hardy WR, Zuo D, Lam SHL, Sanguin-Gendreau V, Cardiff RD, Pawson T, Muller WJ. ShcA signalling is essential for tumour progression in mouse models of human breast cancer. EMBO J. 2008;27:910–920. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou M-M, Meadows RP, Logan TM, Yoon HS, Wade WS, Ravichandran KS, Burakoff SJ, Fesik SW. Solution structure of the Shc SH2 domain complexed with a tyrosine-phosphorylated peptide from the T-cell receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92(17):7784–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Protein Data Bank code 1TCE.

- 21.Novabiochem Letters. Jan, 2004. See. (Catalog number 04−12−3911)

- 22.Kertesz A, Varadi G, Toth GK, Fajka-Boja R, Monostori E, Sarmay G. Optimization of the cellular import of functionally active SH2-domain-interacting phosphopeptides. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:2682–2693. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6346-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Echeverria C, Jiang L, Ramsey TM, Sharma SK, Chen YNP. A new Antennapedia-derived vector for intracellular delivery of exogenous compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:1363–1366. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackwell HE, Sadowsky JD, Howard RJ, Sampson JN, Chao JA, Steinmetz WE, O'Leary DJ, Grubbs RH. Ring closing metathesis of olefinic peptides: Design, synthesis, and structural characterization of macrocyclic helical peptides. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:5291–5302. doi: 10.1021/jo015533k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oishi S, Shi ZD, Worthy KM, Bindu LK, Fisher RJ, Burke TR., Jr. Ring closing metathesis of allylglycines with β-vinyl-substituted residues as an approach to novel macrocyclic β-bend mimetics. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:668–674. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scholl M, Ding S, Lee CW, Grubbs RH. Synthesis and activity of a new generation of Ruthenium-based olefin metathesis catalysts coordinated with 1,3-dimesityl-4,5 dihydroimidazol-2-ylidene ligands. Org. Lett. 1999;1:953–956. doi: 10.1021/ol990909q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikol V, Baumann G, Zurini MGM, Hommel U. Crystal structure of the SH2 domain from the adaptor protein SHC: a model for peptide binding based on x-ray and NMR data. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;254:86–95. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oishi S, Karki RG, Shi ZD, Worthy KM, Bindu L, Chertov O, Esposito D, Frank P, Gillette WK, Maderia M, Hartley J, Nicklaus MC, Barchi J,J, Jr., Fisher RJ, Burke TR., Jr. Evaluation of macrocyclic Grb2 SH2 domain-binding peptide mimetics prepared by ring-closing metathesis of C-terminal allylglycines with an N-terminal beta-vinyl-substituted phosphotyrosyl mimetic. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:2431–2438. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Second Edition Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boor CD. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 2nd Edition Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.