Abstract

Several observations suggest endogenous suppressors of inflammatory mediators are present in human blood. α-1-Antitrypsin (AAT) is the most abundant serine protease inhibitor in blood, and AAT possesses anti-inflammatory activity in vitro and in vivo. Here, we show that in vitro stimulation of whole blood from persons with a genetic AAT deficiency resulted in enhanced cytokine production compared with blood from healthy subjects. Using whole blood from healthy subjects, dilution of blood with RPMI tissue-culture medium, followed by incubation for 18 h, increased spontaneous production of IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-1R antagonist (IL-1Ra) significantly, compared with undiluted blood. Dilution-induced cytokine production suggested the presence of one or more circulating inhibitors of cytokine synthesis present in blood. Serially diluting blood with tissue-culture medium in the presence of cytokine stimulation with heat-killed Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epi) resulted in 1.2- to 55-fold increases in cytokine production compared with S. epi stimulation alone. Diluting blood with autologous plasma did not increase the production of IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1β, or IL-1Ra, suggesting that the endogenous, inhibitory activity of blood resided in plasma. In whole blood, diluted and stimulated with S. epi, exogenous AAT inhibited IL-8, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β significantly but did not suppress induction of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-1Ra and IL-10. These ex vivo and in vitro observations suggest that endogenous AAT in blood contributes to the suppression of proinflammatory cytokine synthesis.

Keywords: inflammation, dilution, serine protease inhibitor, interleukin

INTRODUCTION

Numerous observations demonstrate the presence of endogenous substances in blood, which suppresses the synthesis of proinflammatory molecules. For example, in health, biologically active, proinflammatory cytokines are rarely detected in blood [1]. However, diluting whole blood enhances proinflammatory cytokine production in vitro, suggesting that dilution reduces the function of cytokine inhibitors in blood. Chernoff et al. [2] reported that whole blood dilution enhanced IL-1β and TNF-α production. Similarly, synthesis of intracellular IFN (IFN-γ), TNF-α, IL-2, and IL-10 was optimized when blood was diluted in tissue-culture medium [3,4,5,6]. Therefore, diluting whole blood likely reduces concentrations of circulating inhibitors of cytokine production and increases cytokine synthesis per cell. Despite the common practice of diluting blood to enhance cytokine production, the identity of circulating inhibitors remains unclear.

α-1-Antitrypsin (AAT) is a 394-aa, 52-kDa glycoprotein synthesized primarily by hepatocytes [7], with smaller amounts synthesized by intestinal epithelial cells, neutrophils, pulmonary alveolar cells, and macrophages [8, 9]. AAT is the most abundant, endogenous serine protease inhibitor (Pi) in the circulation. Serum AAT concentrations in healthy subjects are 1.5–3.5 mg/mL and can increase fourfold during inflammation, indicating that AAT is an acute-phase protein [7, 10, 11]. The primary function of AAT is thought to be inactivation of neutrophil elastase and other endogenous serine proteases.

AAT has been studied extensively in the clinical setting as a result of the existence of genetic defects, resulting in abnormally low AAT concentrations in blood and referred to as AAT deficiency. More than 100 AAT alleles have been described, and the normal M-type AAT protein is designated PiM [7]. Persons with normal AAT concentrations in blood usually have two copies of the PiM gene (PiMM phenotype), and the prevalence of this phenotype is ∼83% in the United States population [12]. Reduced AAT levels are typically associated with Z-type (PiZ) or S-type (PiS) AAT variants. The term “AAT deficiency” often refers to the presence of homozygous PiZZ AAT, where serum AAT levels approximate 10–15% of normal [13]. However, other AAT phenotypes are associated with deficient AAT levels and include PiSS, PiSZ, and the pairing of PiZ or PiS with the normal PiM protein (PiMZ or PiMS) [14]. AAT-deficient individuals are at increased risk for extensive and early onset pulmonary emphysema thought to result from progressive destruction of alveolar walls as a result of unopposed activity of neutrophil-derived elastase [15].

Novel studies have expanded the link between AAT and human disease. For example, associations were shown between reduced AAT levels or abnormal AAT proteins and HIV type 1 infection [16,17,18], hepatitis C infection and chronic liver disease [19], atypical mycobacterial infection [20], diabetes mellitus [21], and panniculitis [22]. In mice, exogenous AAT protected islet cell allografts from rejection [23], blocked β cell apoptosis [24], prevented pulmonary emphysema [25], and inhibited angiogenesis and tumor growth [26].

Adding AAT to cultured human cells in vitro has revealed anti-inflammatory properties. For example, Janciauskiene et al. [27] reported that AAT inhibited LPS-stimulated synthesis and secretion of TNF-α and IL-1β in human blood monocytes. In addition, intracellular signaling studies showed that AAT inhibited activation of NF-κB, a transcription factor involved in the expression of several proinflammatory cytokines [18]. Importantly, some reports suggest that the anti-inflammatory properties of AAT may not require the serine Pi activity of AAT [15, 28, 29].

Investigations of AAT anti-inflammatory functions have used cell lines or PBMC-derived macrophages. As these experimental designs may not reflect AAT biological activity in vivo, we used an in vitro assay of cultured human whole blood to conduct studies that represent in vivo conditions more closely. In the present investigations, we addressed several issues in cytokine biology. First, in whole blood cultures, we compared cytokine synthesis in subjects with genetic AAT deficiency with cytokine synthesis in healthy subjects. Second, in whole blood from healthy subjects, we examined the effect of blood dilution on constitutive (spontaneous) and on Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epi)-stimulated cytokine synthesis. Third, we compared spontaneous cytokine production in whole blood diluted with tissue-culture medium with blood diluted with autologous plasma. Fourth, we evaluated exogenously added AAT as an inhibitor of cytokine production in diluted and S. epi-stimulated whole blood cultures. Finally, a synthetic serine Pi was studied for effects on whole blood cytokine production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

S. epi strain 49134 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Remel, Lenexa, KS, USA) and provided by Dr. Mary Bessesen (Denver Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of Colorado Denver, CO, USA). S. epi was grown overnight in suspension cultures in Luria-Bertani medium (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA). The S. epi suspension was heat-killed by boiling for 30 min and the protein concentration of the heat-killed S. epi preparation determined using the Coomassie Plus protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Clinical-grade human AAT (Aralast®, 20 mg/mL stock solution, Baxter Healthcare Corp., Westlake Village, CA, USA) and clinical-grade human serum-derived albumin (250 mg/mL stock solution, ZLB Bioplasma AG, Berne, Switzerland) were used in these studies. H-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-chloromethylketone (AAPV-CMK) was obtained from Bachem (King of Prussia, PA, USA) and solubilized in DMSO (Fisher Biotech, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA) at a stock concentration of 50 mM. RPMI-1640 medium and PBS were purchased from Mediatech (Herndon, VA, USA), and HBSS was obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA).

Whole blood collection from healthy volunteers

Healthy subjects not taking prescribed or over-the-counter medications participated. Blood obtained following antecubital venipuncture was aspirated into sterile glass vacuum tubes containing freeze-dried sodium heparin that resulted in a final heparin concentration of 14.3 units/mL (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Informed consent was obtained from each subject, and the Human Subject Institutional Review Board at the University of Colorado Denver approved the protocol.

Whole blood collection from AAT-deficient patients

Nine patients with AAT deficiency were studied. AAT deficiency was established using criteria defined previously, including serum AAT levels below 0.72 mg/mL (prior to initiation of replacement therapy) and the presence of Z-type AAT mutant protein by phenotype analysis. Five patients had the PiZZ mutant phenotype, two had the PiSZ phenotype, and two had the PiMZ phenotype. Eight of the nine AAT-deficient patients were treated with weekly i.v. infusions of 60 mg/kg Prolastin® (Talecris Biotherapeutics, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA), and one patient was treated with weekly infusions of 60 mg/kg Zemaira® (Aventis Behring LLC, King of Prussia, PA, USA). All nine AAT-deficient patients were diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and treated with inhaled fluticasone-salmeterol, and eight of the nine patients were treated with inhaled albuterol. Other prescribed medications included fluoxetine, tiotropium, iprotropium, lansoprazole, atorvastatin, alendronate, and fexofenadine. AAT concentrations from AAT-deficient and healthy volunteers were determined in heparanized plasma using a human AAT quantitative ELISA (GenWay Biotech, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Informed consent was obtained from each AAT-deficient subject, and the Human Subject Institutional Review Board at the National Jewish Medical and Research Center (Denver, CO, USA) approved the protocol.

Cytokine production in whole blood cultures from AAT-deficient persons and healthy volunteers

Heparinized venous blood obtained from healthy volunteers (controls) and from AAT-deficient donors was transferred to 12 × 75 mm snap-cap polypropylene tubes (Becton Dickinson) under sterile conditions. Heat-killed S. epi (final protein concentration, 1.2 μg/mL) was added to undiluted whole blood (1.0 mL final vol), and the cultures incubated with caps loosely applied at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 18 h. After incubation, the culture supernatants were aspirated, transferred to new tubes, and frozen at −70°C until assayed.

Whole blood dilution studies

Freshly obtained whole blood from each of four healthy subjects was aliquoted into 12 × 75 mm snap-cap polypropylene tubes. The blood from each subject was cultured without dilution or was serially diluted with RPMI to 1:4, 1:8, 1:16, or 1:32 in the absence or presence of 1.2 μg/mL (final concentration) S. epi in a volume of 1.0 mL. The whole blood cultures were then incubated as described above.

Whole blood diluted with RPMI or autologous plasma

Donor-matched (autologous) plasma was obtained by subjecting 8.0 mL heparinized blood from each of four healthy volunteers to 400 g centrifugation for 10 min and aspirating the supernatant plasma. Whole blood was diluted 1:32 with RPMI or with donor-matched plasma in 1.0 mL final vol. The cultures were incubated for 18 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 in loosely capped 12 × 75 mm snap-cap polypropylene tubes. After incubation, the separated plasma components of the cultures were collected and frozen at −70°C until assayed.

Whole blood cultures with exogenous AAT

Whole blood from the same four healthy subjects was diluted 1:32 in RPMI only, diluted 1:32 in RPMI with S. epi stimulation, or diluted 1:32 in RPMI with S. epi stimulation in the presence of increasing concentrations of AAT or albumin (1.0–8.0 mg/mL). AAT or albumin was added 1 h prior to S. epi stimulation, and all final culture volumes were 1.0 mL in 12 × 75 mm snap-cap polypropylene tubes. After 18 h of incubation with loosely applied caps, the separated plasma components of the blood cultures were aspirated and frozen at −70°C until assayed.

Whole blood cultures with exogenous AAPV-CMK

Whole blood from each of four healthy subjects was diluted 1:16 in RPMI only, diluted 1:16 in RPMI, and stimulated with S. epi or diluted 1:16 in RPMI and stimulated with S. epi in the presence of 50 μM AAPV-CMK or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control). AAPV-CMK or DMSO was added 1 h prior to S. epi stimulation, and all final culture volumes were 1.0 mL in 12 × 75 mm snap-cap polypropylene tubes. After 18 h of incubation, the separated supernatants of the cultured blood were aspirated and frozen at −70°C until assayed.

Cytokine measurements

IL-8, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-1R antagonist (IL-1Ra), and IL-10 were measured using ECL assays, as described previously [1, 30,31,32]. All biotinylated antibodies were obtained from eBioscience, Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA). Antibodies obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) were ruthenylated using BV-Tag™-normal human serum-ester (Bioveris Corp., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Cytokine measurements were performed using an M8 ECL analyzer (Bioveris Corp.). The limit of detection for each cytokine ECL assay was 10 pg/mL, and cytokine levels below the assay detection limit were assigned the value 10 pg/mL.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare plasma AAT concentrations and whole blood cytokine production in AAT-deficient subjects and healthy controls (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). For the whole blood dilution studies (see Fig. 2), cytokine concentrations were expressed using two methods: first, as directly measured levels (see Fig. 2, A, C, E, and G) and second, as values calculated by multiplication of the measured level by the dilution factor to obtain the amount of cytokine produced per mL of whole blood that was in the cultures (see Fig. 2, B, D, F, and H). For example, calculated levels in samples diluted 1:16 were obtained by multiplying the measured cytokine concentrations by 16. These calculations equalized the concentration of cytokine-producing leukocytes in undiluted and diluted blood cultures in each donor. For studies comparing cytokine levels in whole blood cultures in the absence or presence of dilution, S. epi stimulation, or AAT (see Figs. 2, 3, and 5), differences between experimental conditions were evaluated using repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. In the studies comparing dilution with RPMI or plasma (see Fig. 4) and in the studies comparing dilution alone with dilution and S. epi stimulation in the absence or presence of AAPV-CMK (see Fig. 6), group means were compared using repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of AAT-Deficient Subjects and Healthy Controls

| Characteristic | AAT-deficient (n = 9) | Healthy controls (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in yearsa | 58 (46–72) | 37 (24–49) |

| Gender (M/F) | 6/3 | 6/4 |

| AAT phenotype: PiZZ | five patients | ND |

| PiSZ | two patients | |

| PiMZ | two patients | |

| AAT dose | 60 mg/kgb | NA |

| Plasma AAT concentration in mg/mLa | 1.67 (1.43–2.61)c | 2.73 (1.81–4.32) |

Data shown as median (range).

Dosing frequency = 1 i.v. infusion per week.

Level determined immediately prior to AAT infusion; P = 0.004. ND = Not determined. NA = Not applicable.

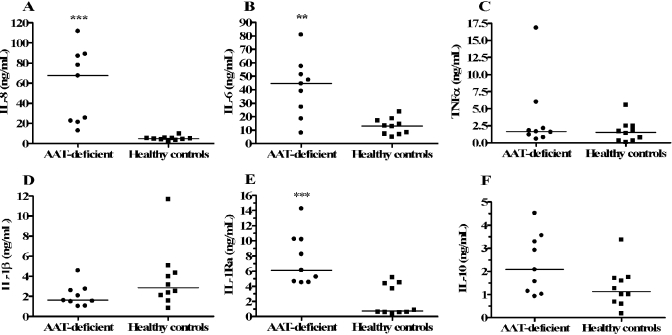

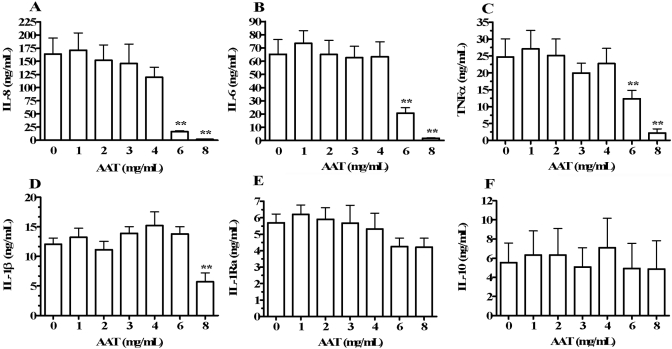

Fig. 1.

Effect of AAT deficiency on cytokine production in stimulated whole blood. Cytokine production was measured in undiluted, S. epi-stimulated blood obtained from nine AAT-deficient patients (•) and from 10 healthy controls (▪). After 18 h of stimulation, supernatants were removed for cytokine assays, including IL-8 (A), IL-6 (B), TNF-α (C), IL-1β (D), IL-1Ra (E), and IL-10 (F). Horizontal bars indicate median levels. **, P < 0.005, and ***, P < 0.0005, compared with healthy controls.

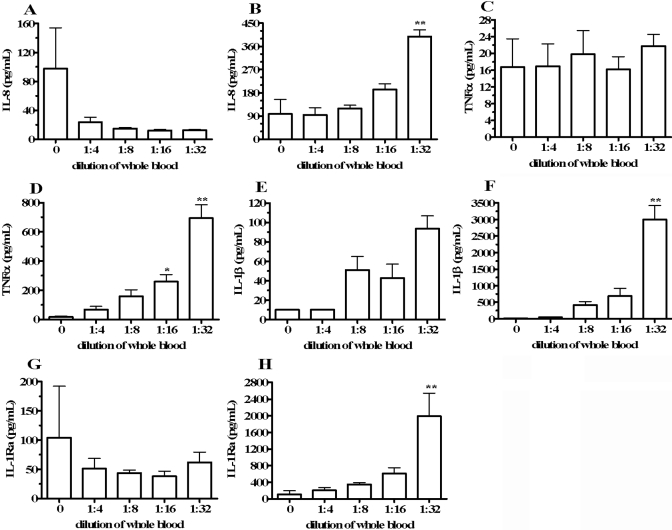

Fig. 2.

Spontaneous cytokine production in whole blood diluted with RPMI. Heparinized whole blood was incubated for 18 h undiluted (dilution=0) or diluted in RPMI to the final concentrations indicated on the horizontal axes. After incubation, supernatants were removed, and cytokine levels were quantified. Cytokine levels are depicted as measured concentrations (A, C, E, and G) or multiplied by the dilution factors (B, D, F, and H). Shown are concentrations of IL-8 (A, B), TNF-α (C, D), IL-1β (E, F), and IL-1Ra (G, H). Cytokine concentrations are indicated on the vertical axes as means ± sem in four separate donors. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, compared with dilution = 0.

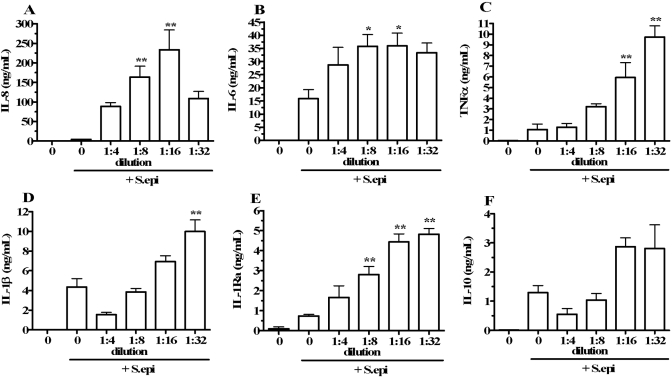

Fig. 3.

Effect of whole blood dilution on S. epi-stimulated cytokine production. Heparinized whole blood was incubated for 18 h undiluted (dilution=0, far-left bars), incubated undiluted with heat-killed S. epi as a stimulus (dilution=0, second bars from left), or with RPMI dilution to the levels indicated on the horizontal axes and with S. epi stimulation. After incubation, cytokine concentrations were measured and expressed as concentration per mL of blood (multiplied by dilution factor) for IL-8 (A), IL-6 (B), TNF-α (C), IL-1β (D), IL-1Ra (E), and IL-10 (F). Cytokine concentrations are indicated on the vertical axes as means ± sem in four separate donors. *, P < 0.05, and **, P < 0.01, compared with cultures stimulated with S. epi in the absence of dilution (dilution=0, second bars from left).

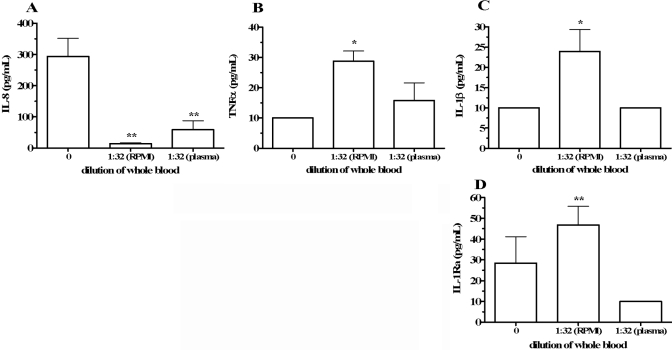

Fig. 4.

Cytokine production in whole blood diluted with RPMI or autologous plasma. Whole blood was incubated for 18 h undiluted (dilution=0), diluted 1:32 in RPMI [1:32 (RPMI)], or diluted 1:32 in autologous plasma [1:32 (plasma)]. Supernatant cytokine concentrations are reported without multiplication by the dilution factor. Shown are levels of IL-8 (A), TNF-α (B), IL-1β (C), and IL-1Ra (D). Cytokine concentrations are indicated on the vertical axes as means ± sem in eight separate donors. For IL-8, **, P < 0.01, compared with dilution = 0; for TNF-α, *, P < 0.05, compared with dilution = 0; for IL-1β, *, P < 0.05, compared with dilution = 0 and to 1:32 (plasma); and for IL-1Ra, **, P < 0.01, compared with 1:32 (plasma).

Fig. 5.

Effect of exogenous AAT on cytokine production in diluted whole blood with S. epi stimulation. Whole blood was diluted 1:32 in RPMI and stimulated with heat-killed S. epi in the absence (AAT=0) or presence of AAT added 1 h prior to S. epi. Final AAT concentrations are shown on the horizontal axes. Supernatant cytokine concentrations were measured and expressed as concentrations per mL of blood (multiplied by dilution factor). Shown are levels of IL-8 (A), IL-6 (B), TNF-α (C), IL-1β (D), IL-1Ra (E), and IL-10 (F). Cytokine concentrations are shown on the vertical axes as means ± sem in cultures from four separate donors. **, P < 0.01, compared with AAT = 0.

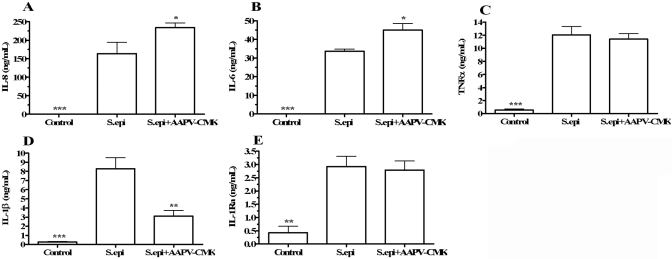

Fig. 6.

Effect of the synthetic serine Pi AAPV-CMK on cytokine production in diluted and S. epi- stimulated whole blood, which was diluted 1:16 in RPMI (Control), diluted 1:16 in RPMI and stimulated with S. epi (S.epi), or diluted 1:16 in RPMI and stimulated with S. epi in the presence of 50 μM AAPV-CMK, added 1 h prior to S. epi (S.epi+AAPV-CMK). After 18 h of incubation, supernatant cytokine concentrations were determined and expressed as concentration per mL of blood (multiplied by dilution factor). Shown are levels of IL-8 (A), IL-6 (B), TNF-α (C), IL-1β (D), and IL-1Ra (E). Cytokine concentrations are shown on the vertical axes as means ± sem in four separate donors. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001, compared with S. epi.

RESULTS

Cytokine production is increased in whole blood from AAT-deficient patients

We compared cytokine production in stimulated whole blood from nine subjects with genetic AAT deficiency to production in 10 healthy controls. Table 1 depicts characteristics of the two groups of participants. Blood from the AAT-deficient donors was collected immediately prior to infusion of Prolastin® or Zemaira® (clinical formulations of AAT) so that blood AAT levels were at their respective nadirs. Plasma AAT concentrations were significantly lower (P=0.004) in the AAT-deficient patients compared with the healthy volunteers (median levels of 1.67 mg/mL and 2.73 mg/mL, respectively). The blood for these studies was cultured without dilution to maintain endogenous AAT concentrations. Whole blood from AAT-deficient and control subjects was stimulated with S. epi and assessed for cytokine production after 18 h of incubation. As shown in Figure 1A, healthy controls produced a median 4.7 ng/mL IL-8, whereas blood cultures in the AAT-deficient donors produced a median 67.6 ng/mL (14.4 times the level in healthy donors, P<0.0005). Median IL-6 and IL-1Ra production were also increased significantly in the AAT-deficient group (3.4 and 8.4 times the median level in healthy controls, respectively, Fig. 1, B and E). However, no significant difference in median TNF-α or IL-1β production was observed in AAT-deficient patients compared with controls (Fig. 1, C and D). IL-10 levels were elevated in the AAT-deficient group (median IL-10 in the AAT-deficient group was 1.8 times that of the healthy controls), but this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 1F).

Diluting whole blood with RPMI increases spontaneous cytokine production

To assess whether blood contains inhibitors of cytokine synthesis, whole blood was collected from four healthy donors and incubated for 18 h, undiluted or diluted with RPMI, to final blood concentrations 1:4, 1:8, 1:16, or 1:32. Figure 2, A, C, E, and G, shows spontaneous cytokine production presented as measured concentrations. In Figure 2, B, D, F, and H, cytokine levels are depicted after multiplication by the dilution factors to obtain the calculated cytokine concentrations in the undiluted blood component of the cultures. These calculations were designed to assess alterations in cytokine produced per white blood cell in blood as a result of dilution. In Figure 2, A and B, undiluted blood (dilution=0) produced 97.8 ± 56.4 pg/mL IL-8 (mean±sem). After multiplying by the dilution factor, blood diluted to final concentrations 1:4, 1:8, 1:16, and 1:32 contained IL-8 levels of 93.9 ± 28.4 pg/mL, 118.9 ± 13.1 pg/mL, 192.7 ± 21.9 pg/mL, and 398.2 ± 26.1 pg/mL, respectively (Fig. 2B). This represented a maximum mean 3.1-fold increase in IL-8 levels in blood diluted 1:32 compared with undiluted blood. In the same whole blood cultures, we measured TNF-α (Fig. 2, C and D), IL-1β (Fig. 2, E and F), and IL-1Ra (Fig. 2, G and H). As observed for IL-8, dilution of blood with RPMI resulted in significant and dose-dependent escalation in spontaneous TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-1Ra after adjustment for dilution. We observed maximum increases of 40-fold, 299-fold, and 18-fold in cytokine levels adjusted for dilution compared with undiluted blood, respectively (Fig. 2, D, F, and H). IL-6 and IL-10 concentrations in the same cultures were below the limit of assay detection for all conditions tested (data not shown).

To determine if increased spontaneous cytokine production was dependent on RPMI constituents, we repeated the blood dilution experiments, except that blood was diluted in PBS or HBSS instead of RPMI. In blood diluted 1:16 or 1:32 in PBS or HBSS, IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-1Ra were increased to similar extents, as observed for dilution in RPMI (data not shown). These results indicate that cytokine increases were dilution-dependent and not a result of RPMI components.

Dilution of blood augments S. epi-induced cytokine production

We extended the dilution studies to assess the effect of dilution on whole blood cultures stimulated with heat-killed S. epi, which is a well-described cytokine inducer in vitro, and S. epi-exposed blood reflects cytokine responses following activation of the TLR-2 [33]. Blood was cultured undiluted, undiluted and stimulated with S. epi, or diluted and stimulated with S. epi. As shown in Figure 3A, undiluted blood (dilution=0; far-left bars) and undiluted blood stimulated with S. epi (dilution=0, second bars from left) produced 97.8 ± 56.4 pg/mL and 4.2 ± 0.3 ng/mL IL-8 after 18 h of incubation, respectively. Blood stimulated with S. epi and diluted 1:4, 1:8, 1:16, or 1:32 with RPMI produced 88.6 ± 9.5 ng/mL, 163.7 ± 27.9 ng/mL, 233.6 ± 50.7 ng/mL, and 108.8 ± 18.1 ng/mL IL-8, respectively. Diluting S. epi-stimulated blood 1:16 produced a maximum mean 55-fold IL-8 increase (P<0.01) compared with blood exposed to S. epi in the absence of dilution. In the same whole blood cultures, we measured IL-6 (Fig. 3B), TNF-α (Fig. 3C), IL-1β (Fig. 3D), IL-1Ra (Fig. 3E), and IL-10 (Fig. 3F). As observed for IL-8, cultures stimulated with S. epi and diluted with RPMI demonstrated significant increases in cytokine concentrations compared with undiluted, S. epi-stimulated cultures. Combined S. epi stimulation and RPMI dilution resulted in maximum IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-1Ra, and IL-10 levels that were increased 1.3-fold (P<0.05), 8.1-fold (P<0.01), 1.3-fold (P<0.01), 5.6-fold (P<0.01), and 1.2-fold (P=not significant) compared with levels observed with S. epi stimulation alone (no dilution), respectively.

Effect of diluting blood with autologous plasma on cytokine production

To determine if increased cytokine production in diluted blood was a result of reduced concentration of inhibitory substances in plasma, we examined the effect of blood dilution with autologous plasma. Blood was collected from four healthy donors and incubated for 18 h undiluted, diluted with RPMI to a final blood concentration of 1:32, or diluted 1:32 in autologous plasma. Cytokine levels were not multiplied by the dilution factor (1:32) to directly compare the cytokine levels in undiluted blood (dilution=0) and in plasma-diluted blood. Compared with blood diluted in RPMI, dilution in plasma suppressed TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-1Ra production (Fig. 4, B–D, respectively). IL-8 production was decreased in RPMI and plasma-diluted samples (Fig. 4A). Although IL-8 measured in the plasma-diluted cultures was increased compared with the RPMI-diluted cultures, the difference was not statistically significant. We also measured IL-6 and IL-10 in these cultures, and levels were below the detection limit (10 pg/mL) of the ECL assays in all conditions tested (data not shown).

Exogenous AAT inhibits cytokine production in whole blood cultures

As AAT deficiency resulted in greater cytokine production in whole blood cultures (Fig. 1), and other studies report anti-inflammatory properties of AAT [7, 10, 11, 27, 34], we examined the effect of exogenous AAT on stimulated cytokine production in whole blood. As shown in Figure 5A, whole blood cultures diluted 1:32 with RPMI and stimulated with S. epi (AAT=0) induced a mean 163.7 ± 30.9 ng/mL IL-8. The addition of AAT reduced IL-8 in diluted and S. epi-stimulated whole blood by a maximum of 99% using 8 mg/mL AAT compared with cultures conducted in the absence of AAT. In these cultures, we also measured IL-6 (Fig. 5B), TNF-α (Fig. 5C), IL-1β (Fig. 5D), IL-1Ra (Fig. 5E), and IL-10 (Fig. 5F). Dose-dependent IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β suppression was observed in the presence of AAT, with maximum mean reductions of 97%, 91%, and 47%, respectively, compared with cultures without AAT. However, AAT did not affect the levels of stimulated IL-1Ra and IL-10 significantly (Fig. 5, E and F).

To assess the specificity of AAT inhibition of stimulated whole blood cytokine production, we used human serum-derived albumin as a protein control. Whole blood was diluted 1:32 with RPMI and stimulated with S. epi in the absence (control) or presence of 1–8 mg/mL albumin. In three separate experiments, albumin did not affect diluted and S. epi-stimulated whole blood production of any cytokine tested (IL-8, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-1Ra, and IL-10; data not shown).

Effect of AAPV-CMK, a synthetic serine Pi, on cytokine production

As AAT is the prototypical serine Pi in the circulation, we surmised that AAT-induced suppression of whole blood proinflammatory cytokine production was a result of inhibition of serine proteases. Therefore, we tested AAPV-CMK, a small-molecule synthetic inhibitor of serine proteases in whole blood cytokine production [18]. Blood was collected from healthy donors and diluted 1:16 with RPMI (control), diluted 1:16 with RPMI and stimulated with S. epi, or diluted 1:16 with RPMI and stimulated with S. epi in the presence of 50 μM AAPV-CMK (added 1 h prior to S. epi). After 18 h of incubation, the mean IL-8 and IL-6 levels in blood diluted and stimulated with S. epi were 163.8 ± 30.4 ng/mL and 33.7 ± 1.1 ng/mL, respectively (Fig. 6, A and B, S. epi). Compared with diluted and S. epi-stimulated blood, AAPV-CMK exposure resulted in a statistically significant increase in IL-8 (234.3±12.4 ng/mL, P<0.05) and IL-6 (45.0±3.5 ng/mL, P<0.05) production. AAPV-CMK did not affect stimulated TNF-α (Fig. 6C) or IL-1Ra significantly (Fig. 6E). In contrast, IL-1β was reduced in diluted and S. epi-stimulated cultures containing AAPV-CMK compared with diluted and S. epi-stimulated cultures (Fig. 6D) with a mean reduction of 62.5% compared with blood-diluted 1:16 and stimulated with S. epi (P<0.01).

As AAPV-CMK was solubilized in DMSO, we examined the DMSO effect in whole blood cytokine production. Whole blood was diluted 1:16 with RPMI and S. epi, or blood was diluted 1:16 with S. epi and the equivalent volume of DMSO used in the AAPV-CMK experiments (added 1 h prior to S. epi). After the whole blood cultures were incubated for 18 h, the presence of DMSO did not significantly affect diluted and S. epi-stimulated production of any cytokine tested (IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-1Ra; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Cytokine production in disease is studied commonly to elucidate pathogenesis or to quantify disease severity. Although cytokines are measured routinely in serum, circulating cytokine levels are transient and reflect production, renal clearance, hepatic metabolism, and binding to soluble cytokine receptors or natural anticytokine antibodies [35,36,37,38]. Several studies have shown that cytokine RNA expression in freshly isolated whole blood is low or absent [39,40,41]. In the case of IL-1β, low gene expression and absence of the IL-1β precursor protein have been reported [40, 41]. In contrast, IL-18 gene expression and the biologically inactive IL-18 precursor protein are present in the circulation of healthy individuals [41, 42].

Although PBMC or monocyte-derived macrophages are commonly used to study in vitro cytokine production, the isolation procedures are time-consuming and can result in nonspecific stimulation of cytokine production [38]. In addition, PBMC populations do not reflect the ratios of cellular components in circulating blood [3, 43]. For example, in PBMC preparations, there are few or no neutrophils, and monocytes are three to five times more abundant than in the circulation. For these reasons, incubation of whole blood cultures for the analysis of cytokine production and regulation emulates in vivo conditions more closely. However, dilution of blood is necessary to maximize cytokine synthesis in whole blood cultures [2,3,4,5,6], suggesting that in vitro dilution of whole blood reduces the concentration of factors present in the plasma that suppress cytokine production. In the present study, we assessed the role of AAT in cytokine production in whole blood cultures.

AAT deficiency is a genetic condition that increases the risk of early onset and severe emphysema, chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, and liver disease [7, 13, 15]. To examine AAT anticytokine activity under in vivo-like conditions, we assessed cytokine production in blood obtained from AAT-deficient persons and from healthy controls. The whole blood was not diluted to maintain endogenous AAT concentrations. S. epi-stimulated blood collected from AAT-deficient individuals demonstrated significantly greater IL-8, IL-6, and IL-1Ra production compared with blood from healthy donors (Fig. 1). These findings suggest that reduced AAT blood levels in AAT-deficient subjects are associated with increased cytokine production, implicating AAT as a cytokine-suppressive factor in whole blood cultures.

These studies likely underestimate the cytokine-suppressive effects of AAT. As our AAT-deficient patients received chronic AAT replacement therapy, the difference in AAT levels between AAT-deficient patients and healthy controls was narrowed. Despite AAT replacement therapy, the median AAT level was reduced significantly in the AAT-deficient patients (1.67 mg/mL) compared with healthy controls (2.73 mg/mL). This difference was sufficient to result in significantly higher IL-8, IL-6, and IL-1Ra production in the AAT-deficient group (Fig. 1). It is possible that larger reductions in AAT (for example, in AAT-deficient persons not receiving AAT supplementation) would result in significantly enhanced levels of other cytokines compared with healthy persons with normal amounts of AAT.

When blood was diluted with RPMI tissue-culture medium, spontaneous, proinflammatory cytokine production per mL of blood was increased significantly (Fig. 2). Mean IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-1Ra levels were increased 3.1-, 40-, 299-, and 18-fold compared with levels observed in undiluted blood. Diluted whole blood cytokine levels that were not adjusted for dilution demonstrated a dramatic reduction in IL-8, which was not present for any other cytokine tested (Fig. 2A). In fact, blood dilution resulted in increased, unadjusted TNF-α and IL-1β concentrations, and IL-1Ra concentrations were only slightly reduced. Although the reason for this anomalous IL-8 observation is uncertain, it may be relevant that of the cytokines measured, only IL-8 is produced by polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN). It is possible that blood dilution reduced PMN concentrations in the cultures to the point that unadjusted IL-8 levels declined precipitously. Alternatively, as cell–cell contact between monocytes and T cells has been shown to enhance IL-8 production [44], larger dilutions of blood may limit the intercellular contact necessary for efficient IL-8 production. It is noteworthy that dilution-induced diminution in monocyte concentrations did not result in similar reductions in the monocyte-derived cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-1Ra (Fig. 2, C, E, and G). However, despite dilution-induced reductions in unadjusted IL-8 levels, adjusted IL-8 concentrations (multiplication of IL-8 concentrations by the dilution factor) increased with dilution (Fig. 2B).

We also examined the effect of dilution on cytokine production in blood stimulated with S. epi (Fig. 3). Dilution-induced increases in cytokine production were observed for each S. epi-stimulated cytokine tested (IL-8, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-1Ra, and IL-10). These results show that dilution increased cytokine levels in stimulated whole blood beyond levels observed with S. epi stimulation alone. In contrast to all other measured cytokines, IL-8 production was not maximal at the highest dilution but peaked at 1:16 dilution and decreased at the 1:32 dilution (Fig. 3A). It is not clear why IL-8 production did not continue to increase with higher dilution. It is possible that in the presence of S. epi simulation and high (1:32) dilution, the IL-8 contribution by PMN decreased, as described for Figure 2A.

Three possibilities may explain increases in dilution-induced cytokine production in the presence of S. epi stimulation as observed in Figure 3: i) Dilution decreased cell–cell interaction, which may enhance cytokine production; ii) the concentration of cells was decreased in diluted samples, resulting in an increase in the total amount of stimulus (S. epi) molecules per cell; and iii) cytokine production was enhanced by reducing concentrations of natural inhibitors in the blood. As a dilution-induced reduction in cell–cell interaction would be expected to decrease the levels of cytokines produced [45], this likely cannot explain the increase in cytokine production associated with dilution (Figs. 2 and 3). Furthermore, as the fluid-phase concentration of S. epi was identical in each diluted blood culture, the increased, total amount of S. epi per cell in the cultures would not alter the magnitude of stimulation per cell. Therefore, the hypothesis that soluble plasma inhibitors are depleted by dilution is the most likely explanation.

To confirm the presence of cytokine inhibitors in the plasma component of circulating blood, we diluted whole blood 1:32 in RPMI or autologous plasma (Fig. 4). Dilution in plasma did not increase levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-1Ra compared with levels observed in undiluted blood. In no case did plasma dilution increase cytokine synthesis significantly, as observed for blood diluted in RPMI. These results support the contention that dilution-induced cytokine synthesis is a result of reduced concentrations of suppressive factors in plasma (as shown in Fig. 2). Unlike the other cytokines we tested, IL-8 decreased in response to dilution (Fig. 4A). As Figure 4 data are presented as levels unadjusted for dilution, the results are similar to the data shown in Figure 2A. As described in the text above that refers to Figure 2, only IL-8 levels declined substantially with dilution. We surmise this is a result of diminishing PMN contribution to IL-8 production, where each PMN, may not respond to dilution with increased IL-8 synthesis to the extent that the monocyte-derived cytokines increase with dilution.

Major protein components of plasma include albumin, Igs, α 2-macroglobulin, and AAT. Several studies have suggested that AAT possesses anti-inflammatory function [10, 23, 27, 34, 46,47,48], raising the possibility that AAT contributes to proinflammatory cytokine suppression in whole blood. As shown in Figure 1, we demonstrated enhanced cytokine production in stimulated cultures of whole blood obtained from AAT-deficient patients compared with whole blood from healthy subjects. These data identified AAT as a likely cytokine-suppressive factor in blood. To determine if AAT inhibited cytokine production directly in whole blood cultures, we added exogenous AAT to whole blood that was diluted with RPMI and stimulated with S. epi (Fig. 5). AAT (6–8 mg/mL) suppressed IL-8, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β production significantly by 99%, 97%, 91%, and 47%, respectively (Fig. 5, A–D). Relatively high concentrations (6–8 mg/mL) of exogenous AAT were required for substantial cytokine suppression in these experiments. Although AAT levels of this magnitude can occur during the acute-phase response, it is noteworthy that other molecules in the circulation besides AAT suppress cytokines. For example, α2-macroglobulin contributes to inflammatory response modulation by binding and sequestering cytokines [49]. Therefore, significant cytokine suppression in diluted whole blood likely requires high exogenous AAT concentrations to compensate for the reduced levels of other (non-AAT) inhibitors. Also, high AAT levels may have been necessary to overcome the large cytokine induction effect provided by the combination of dilution and S. epi stimulation.

Unexpectedly, exogenous AAT at these same levels did not suppress IL-1Ra and IL-10 significantly (Fig. 5, E and F), two cytokines with anti-inflammatory activities. This suggests that AAT preferentially inhibits proinflammatory cytokines, many of which are regulated through the NF-κB pathway [50, 51], and AAT has been shown to inhibit NF-κB activation [18, 46]. In contrast, IL-10 is stimulated through cAMP, and AAT has been shown to increase cAMP synthesis and IL-10 production in human monocytes in vitro [34, 52]. These opposing, AAT-induced, intracellular signaling effects may explain why AAT suppressed pro- but not anti-inflammatory cytokines in our in vitro studies.

We used a synthetic inhibitor of serine proteases, AAPV-CMK, to determine if serine protease blockade is the mechanism by which AAT suppresses cytokine production in whole blood (Fig. 6). AAPV-CMK (50 μM) did not inhibit dilution and S. epi-stimulated TNF-α or IL-1Ra production, suggesting that serine protease blockade does not necessarily inhibit these cytokines in whole blood. Interestingly, AAPV-CMK increased IL-8 and IL-6 production to a significant extent, which contradicts the hypothesis that serine protease inhibition is the mechanism by which AAT suppressed cytokine production in these investigations. Unlike the other cytokines assessed, IL-1β production was inhibited significantly by AAPV-CMK added to stimulated whole blood (Fig. 6D). Of the cytokines we tested, only IL-1β is secreted following processing by the caspase-1 inflammasome [53]. It is possible that inhibition of caspase-1 activity by AAPV-CMK blocked IL-1β processing and prevented mature IL-1β release into the culture supernatant. Collectively, these AAPV-CMK results further suggest that serine protease inhibition cannot completely account for AAT suppression of proinflammatory cytokines, an observation noted by others [15, 28, 29].

These studies suggest that AAT is an endogenous inhibitor of proinflammatory cytokine production in whole blood, and AAT may participate in containing an aggressive innate immune response to an inflammation-inducing stimulus. Furthermore, AAT activities separate from serine protease inhibition likely participate in proinflammatory cytokine suppression. Administration of exogenous AAT to patients with disease characterized by excessive cytokine synthesis and inflammation may provide therapeutic benefit.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grant A115614 (to C. A. D.) and the Campbell Foundation (to L. S.). The authors thank Dr. Kristin Morris and Scott Beard for reviewing the manuscript and the AAT-deficient patients for participating in these investigations.

References

- Puren A J, Fantuzzi G, Gu Y, Su M S, Dinarello C A. Interleukin-18 (IFNγ-inducing factor) induces IL-8 and IL-1β via TNFα production from non-CD14+ human blood mononuclear cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:711–721. doi: 10.1172/JCI1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff A E, Granowitz E V, Shapiro L, Vannier E, Lonnemann G, Angel J B, Kennedy J S, Rabson A R, Wolff S M, Dinarello C A. A randomized, controlled trial of IL-10 in humans. Inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production and immune responses. J Immunol. 1995;154:5492–5499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy-Ramirez K, Franck K, Mahdavifar S, Andersson L, Gaines H. Optimum culture conditions for specific and nonspecific activation of whole blood and PBMC for intracellular cytokine assessment by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 2004;292:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaak A J, van den Brink H G, Aarden L A. Cytokine production in whole blood cell cultures of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:693–695. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.11.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewell W A, North M E, Webster A D, Farrant J. Determination of intracellular cytokines by flow-cytometry following whole-blood culture. J Immunol Methods. 1997;209:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaqoob P, Newsholme E A, Calder P C. Comparison of cytokine production in cultures of whole human blood and purified mononuclear cells. Cytokine. 1999;11:600–605. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank CA, Brantly M. Clinical features and molecular characteristics of α 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Ann Allergy. 1994;72:105–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldonyte R, Jansson L, Ljungberg O, Larsson S, Janciauskiene S. Polymerized α-antitrypsin is present on lung vascular endothelium. New insights into the biological significance of α-antitrypsin polymerization. Histopathology. 2004;45:587–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.02021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabbagh K, Laurent G J, Shock A, Leoni P, Papakrivopoulou J, Chambers R C. α-1-Antitrypsin stimulates fibroblast proliferation and procollagen production and activates classical MAP kinase signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2001;186:73–81. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200101)186:1<73::AID-JCP1002>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrell R W. α 1-Antitrypsin: molecular pathology, leukocytes, and tissue damage. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1427–1431. doi: 10.1172/JCI112731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massi G, Chiarelli C. α 1-Antitrypsin: molecular structure and the Pi system. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1994;393:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Serres F J. Worldwide racial and ethnic distribution of α1-antitrypsin deficiency: summary of an analysis of published genetic epidemiologic surveys. Chest. 2002;122:1818–1829. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.5.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Serres F J. α-1 Antitrypsin deficiency is not a rare disease but a disease that is rarely diagnosed. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1851–1854. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnlein T, Welte T. α-1 Antitrypsin deficiency: pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Med. 2008;121:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wewers M D, Gadek J E. The protease theory of emphysema. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:761–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-5-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papuashvili M N, Savitskaya J, Kostrikin D, Novokhatsky A. Low-level alpha-1-antitrypsin in serum of hiv-infected patients demonstrates progression of disease. Int Conf AIDS (2002 July 7–12) 2002;14 abstract no. A10113. [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff A V, Munch J, Kirchhoff F, Brockmeyer N H. HIV infection in a patient with α-1 antitrypsin deficiency: a detrimental combination? AIDS. 2007;21:2115–2116. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f08b97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L, Pott G B, Ralston A H. α-1-Antitrypsin inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1. FASEB J. 2001;15:115–122. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0311com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok K F, Wahab P J, Houwen R H, Drenth J P, de Man R A, van Hoek B, Meijer J W, Willekens F L, de Vries R A. Heterozygous α-I antitrypsin deficiency as a co-factor in the development of chronic liver disease: a review. Neth J Med. 2007;65:160–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E D, Kaminska A M, Gill W, Chmura K, Feldman N E, Bai X, Floyd C M, Fulton K E, Huitt G A, Strand M J, Iseman M D, Shapiro L. α-1-Antitrypsin (AAT) anomalies are associated with lung disease due to rapidly growing mycobacteria and AAT inhibits Mycobacterium abscessus infection of macrophages. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:690–696. doi: 10.1080/00365540701225744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi M, Naderi M, Rashidi H, Ghavami S. Impaired activity of serum α-1-antitrypsin in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:246–248. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Riordan K, Blei A, Rao M S, Abecassis M. α 1-Antitrypsin deficiency-associated panniculitis: resolution with intravenous α 1-antitrypsin administration and liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1997;63:480–482. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199702150-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis E C, Shapiro L, Bowers O J, Dinarello C A. α1-Antitrypsin monotherapy prolongs islet allograft survival in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12153–12158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505579102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Lu Y, Campbell-Thompson M, Spencer T, Wasserfall C, Atkinson M, Song S. α1-Antitrypsin protects β-cells from apoptosis. Diabetes. 2007;56:1316–1323. doi: 10.2337/db06-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrache I, Fijalkowska I, Zhen L, Medler T R, Brown E, Cruz P, Choe K H, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Scerbavicius R, Shapiro L, Zhang B, Song S, Hicklin D, Voelkel N F, Flotte T, Tuder R M. A novel antiapoptotic role for α1-antitrypsin in the prevention of pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1222–1228. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200512-1842OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Campbell S C, Nelius T, Bedford D F, Veliceasa D, Bouck N P, Volpert O V. α1-Antitrypsin inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:1042–1048. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janciauskiene S, Larsson S, Larsson P, Virtala R, Jansson L, Stevens T. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-mediated human monocyte activation, in vitro, by α1-antitrypsin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;321:592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniyam D, Virtala R, Pawlowski K, Clausen IG, Warkentin S, Stevens T, Janciauskiene S. TNF-α-induced self expression in human lung endothelial cells is inhibited by native and oxidized α1-antitrypsin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;40:258–271. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janciauskiene S, Moraga F, Lindgren S. C-terminal fragment of α1-antitrypsin activates human monocytes to a pro-inflammatory state through interactions with the CD36 scavenger receptor and LDL receptor. Atherosclerosis. 2001;158:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00767-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaver D R. A new non-isotopic detection system for immunoassays. Nature. 1995;377:758–760. doi: 10.1038/377758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadkhodayan S, Elliott L O, Mausisa G, Wallweber H A, Deshayes K, Feng B, Fairbrother W J. Evaluation of assay technologies for the identification of protein–peptide interaction antagonists. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2007;5:501–513. doi: 10.1089/adt.2007.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang M, Klakamp S L, Funelas C, Lu H, Lam B, Herl C, Umble A, Drake A W, Pak M, Ageyeva N, Pasumarthi R, Roskos L K. Detection of high- and low-affinity antibodies against a human monoclonal antibody using various technology platforms. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2007;5:655–662. doi: 10.1089/adt.2007.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuyt R J, Kim S H, Reznikov L L, Fantuzzi G, Novick D, Rubinstein M, Kullberg B J, van der Meer J W, Dinarello C A, Netea M G. Regulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis-induced IFN-γ in whole human blood: the role of endogenous IL-18, IL-12, IL-1, and TNF. Cytokine. 2003;21:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(02)00501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janciauskiene S M, Nita I M, Stevens T. α1-Antitrypsin, old dog, new tricks. α1-Antitrypsin exerts in vitro anti-inflammatory activity in human monocytes by elevating cAMP. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8573–8582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607976200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtzen K. Anti-IFN BAb and NAb antibodies: a minireview. Neurology. 2003;61:S6–10. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000092357.07278.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtzen K, Hansen M B, Ross C, Svenson M. Detection of autoantibodies to cytokines. Mol Biotechnol. 2000;14:251–261. doi: 10.1385/MB:14:3:251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brynskov J, Nielsen O H, Ahnfelt-Ronne I, Bendtzen K. Cytokines (immunoinflammatory hormones) and their natural regulation in inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis): a review. Dig Dis. 1994;12:290–304. doi: 10.1159/000171464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L, Dinarello C A. Hyperosmotic stress as a stimulant for proinflammatory cytokine production. Exp Cell Res. 1997;231:354–362. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin K, Turteltaub K, Bankaitis-Davis D, Gerren R, Siconolfi L, Storm K, Cheronis J, Trollinger D, Macejak D, Tryon V, Bevilacqua M. Limited dynamic range of immune response gene expression observed in healthy blood donors using RT-PCR. Mol Med. 2006;12:185–195. doi: 10.2119/2006-00018.McLoughlin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileno M D, Margolis N H, Clark B D, Dinarello C A, Burke J F, Gelfand J A. Coagulation of whole blood stimulates interleukin-1 β gene expression. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:308–311. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puren A J, Fantuzzi G, Dinarello C A. Gene expression, synthesis, and secretion of interleukin 18 and interleukin 1β are differentially regulated in human blood mononuclear cells and mouse spleen cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2256–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sailer C A, Pott G B, Dinarello C A, Whinney S M, Forster J E, Larson-Duran J K, Landay A, Al-Harthi L, Schooley R T, Benson C A, Judson F N, Thompson M, Palella F J, Shapiro L. Whole-blood interleukin-18 level during early HIV-1 infection is associated with reduced CXCR4 coreceptor expression and interferon-γ levels. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:734–738. doi: 10.1086/511435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appay V, Reynard S, Voelter V, Romero P, Speiser D E, Leyvraz S. Immuno-monitoring of CD8+ T cells in whole blood versus PBMC samples. J Immunol Methods. 2006;309:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech J T, Andreakos E, Ciesielski C J, Green P, Foxwell B M, Brennan F M. T-cell contact-dependent regulation of CC and CXC chemokine production in monocytes through differential involvement of NFκB: implications for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R168. doi: 10.1186/ar2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayer J M. How T-lymphocytes are activated and become activators by cell–cell interaction. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;44:10s–15s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00000403b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldonyte R, Jansson L, Janciauskiene S. Concentration-dependent effects of native and polymerized α1-antitrypsin on primary human monocytes, in vitro. BMC Cell Biol. 2004;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bata J, Martin J P, Revillard J P. Cell surface protease activity of human lymphocytes; its inhibition by α 1-antitrypsin. Experientia. 1981;37:518–519. doi: 10.1007/BF01986172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churg A, Wang X, Wang R D, Meixner S C, Pryzdial E L, Wright J L. α1-Antitrypsin suppresses TNF-α and MMP-12 production by cigarette smoke-stimulated macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:144–151. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0345OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feige J J, Negoescu A, Keramidas M, Souchelnitskiy S, Chambaz E M. α 2-Macroglobulin: a binding protein for transforming growth factor-β and various cytokines. Horm Res. 1996;45:227–232. doi: 10.1159/000184793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozato K, Tsujimura H, Tamura T. Toll-like receptor signaling and regulation of cytokine gene expression in the immune system. Biotechniques. 2002;Oct.:66–68. 70, 72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawiger J. Innate immunity and inflammation: a transcriptional paradigm. Immunol Res. 2001;23:99–109. doi: 10.1385/IR:23:2-3:099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi S, Good R A, Day N K. Immunosuppressive retroviral peptides: cAMP and cytokine patterns. Immunol Today. 1995;16:595–603. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello C A. Interleukin-1 β, interleukin-18, and the interleukin-1 β converting enzyme. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;856:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]