Abstract

The relative composition of the two major monocytic subsets CD14+CD16− and CD14+CD16+ is altered in some allergic diseases. These two subsets display different patterns of Toll-like receptor levels, which could have implications for activation of innate immunity leading to reduced immunoglobulin E-specific adaptive immune responses. This study aimed to investigate if allergic status at the age of 5 years is linked to differences in monocytic subset composition and their Toll-like receptor levels, and further, to determine if Toll-like receptor regulation and cytokine production upon microbial stimuli is influenced by the allergic phenotype. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 5-year-old allergic and non-allergic children were stimulated in vitro with lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan. Cells were analysed with flow cytometry for expression of CD14, Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). The release of cytokines and chemokines [tumour necrosis factor, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70] into culture supernatants was measured with cytometric bead array. For unstimulated cells there were no differences in frequency of the monocytic subsets or their Toll-like receptor levels between allergic and non-allergic children. However, monocytes from allergic children had a significantly lower up-regulation of Toll-like receptor 2 upon peptidoglycan stimulation. Further, monocytes from allergic children had a higher spontaneous production of IL-6, but there were no differences between the two groups regarding p38-MAPK activity or cytokine and chemokine production upon stimulation. The allergic subjects in this study have a monocytic population that seems to display a hyporesponsive state as implicated by impaired regulation of Toll-like receptor 2 upon peptidoglycan stimulation.

Keywords: allergy, cytokines, monocytes, Toll-like receptors

Introduction

Studies of children growing up under different microbial exposures have shown that activation of innate immunity gives rise to a reduced immunoglobulin (Ig)E-specific adaptive immune response [1]. Pattern recognition receptors, such as the Toll-like receptors (TLRs), are important mediators of the innate immune response to microbial ligands [2], and TLR mRNA levels [3] and polymorphisms [4–6] have been shown to be important for susceptibility and severity of allergic diseases. The timing of microbial exposure further seems to be of importance for the development of allergic disease [7].

We have shown previously that cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMC) from newborns with allergic mothers have a defective interleukin (IL)-6 response to peptidoglycan (PGN) compared with children born from non-allergic mothers. However, no clear differences in cord blood monocytic surface TLR-2/TLR-4 expression in connection with maternal allergy were seen [8]. This was supported recently by another study, where allergic adults were shown to produce lower levels of proinflammatory cytokines following TLR-2 ligation, despite normal TLR-2 surface levels compared with non-allergic subjects [9]. As the altered IL-6 levels in our study were not mirrored in the TLR levels on the cell surface we further investigated intracellular events taking place after microbial stimulation. p38-Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is a well-characterized protein kinase known to be important for TLR-induced cytokine secretion [10]. We could show that children with allergic mothers have a statistically significant lower expression of monocytic phosphorylated p38-MAPK in response to PGN at 2 years of age compared with children with non-allergic mothers [11].

Recent evidence indicates that blood monocytes consist of several subpopulations. The subdivisions have sometimes been indistinct, but it has now been shown convincingly that the most prominent populations are the classical CD14+CD16− subpopulation and the proinflammatory CD14+CD16+ subpopulation, the latter representing about 10% of all monocytes in healthy individuals [12]. CD16 is the low-affinity receptor for IgG, therefore also named FcγRIII. CD14, expressed by monocytes and macrophages, is the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) binding receptor that presents LPS to its signalling receptor complex, MD-2/TLR-4 [13]. These two monocytic subsets have been shown to have different basal expressions of TLR-2/TLR-4 and to behave differently in response to microbial stimuli [14]. The relative numbers of these monocyte populations within an individual could therefore have an influence on TLR-mediated immune responses, and subsequently the adaptive immune responses.

The role of the two different monocyte subpopulations in allergic disorders is not elucidated fully. One study showed that blood monocytes from untreated adult asthmatics have a higher percentage of the proinflammatory CD14+CD16+ subset than non-allergic subjects [15]. Atopic eczema has also been linked to an increased population of CD14+CD16+, which was diminished in connection with clinical improvement [16]. However, another study on atopic dermatitis did not find any differences in the two monocytic subsets or in TLR levels, but an impaired IL-1β and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) production in response to a TLR-2 ligand [9].

In this study, we wanted to investigate if there were differences between allergic and non-allergic children in the ratio of the two monocytic subsets (CD14+CD16− and CD14+CD16+). We also wanted to examine the TLR-2/TLR-4 levels on the two subsets, as the different expressions of these receptors could play an important role in the response to microbial stimuli, thus also having an impact on susceptibility and severity of allergic diseases.

We further wanted to follow up our earlier results of defective IL-6 and p38-MAPK phosphorylation attributed to allergic heredity in children at birth and 2 years of age [8,11]. The fact that at 2 years the IgE sensitization of the children was not correlated with defective signalling [11] prompted us to look at children with a more manifested allergic disease. Further, as adult allergic individuals show a selective impairment of IL-1β and TNF in response to TLR-2 stimulation we were interested in looking at how children at the age of 5 years respond to microbial stimuli in terms of production of proinflammatory cytokines. The results at 5 years could differ substantially from what we found in children at birth and at 2 years of age, as this period is a very important time for the development of the immune system.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 33 children were selected randomly from a cohort of infants participating in a larger prospective study described in detail elsewhere [17]. The children were classified as allergic (n = 16) or non-allergic (n = 17) (Table 1) based on their clinical history, together with skin prick test (SPT) and specific IgE results at the age of 5. There were no significant differences between the two groups regarding environmental exposures such as attending day care, number of older siblings and the duration of exclusive breast-feeding (Table 1). The Human Ethics Committee in Stockholm approved this study and the parents provided their informed consent.

Table 1.

Demographic data of children.

| Allergic | Non-allergic | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group size, n | 16 | 17 | |

| Female/male, n | 7/9 | 8/9 | n.s. |

| Obstetric information | |||

| Delivery mode vaginal (caesarean) | 11 (5) | 16 (1) | n.s. |

| Birth weight, g, median (range) | 3468 (2680–4550) | 3555 (2805–4400) | n.s. |

| Sensitization data (n)* | |||

| Egg white | 0 | ||

| Peanut | 4 | ||

| Cow's milk | 4 | ||

| Soy bean protein | 1 | ||

| Cat | 3 | ||

| Dog | 2 | ||

| Dermatophagoides farinae | 0 | ||

| Birch | 6 | ||

| Timothy | 3 | ||

| Environmental exposure | |||

| Exclusive breast-feeding, months, median (range) | 4 (0·5–9) | 4 (0–6) | n.s. |

| Attending day care, n, yes (no) | 12 (4) | 16 (1) | n.s. |

| Age at which day care started, months, median (range) | 17 (13–24) | 18 (14–21) | n.s. |

| Older siblings at home, n | |||

| No sibling | 10 | 7 | n.s. |

| 1 sibling | 6 | 6 | n.s. |

| ≥ 2 siblings | 0 | 4 | n.s. |

Based on skin prick test, positive if ≥ 3 mm and/or specific immunoglobulin E, positive if ≥ 0·70 kUA/l; n.s., not significant.

Skin prick test

The children underwent SPT against food and inhalant allergens, which were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendation (ALK, Copenhagen, Denmark). The SPT included food allergens: egg white (Soluprick weight to volume ratio 1/100); cod (Soluprick 1/20); peanut (Soluprick 1/20); cow's milk (3% fat, standard milk) and soy bean protein (Soja Semp®; Semper AB, Stockholm, Sweden). SPT was also performed for inhalant allergens: cat, dog, horse, birch, timothy, mugworth and Dermatophagoides farinae (Soluprick 10 HEP). The SPT was considered positive if the wheal diameter was = 3 mm after 15 min. Histamine chloride (10 mg/ml) and the allergen diluent served as positive and negative controls respectively.

Determination of specific IgE

The children were tested serologically for the same allergens as for SPT, all performed with ImmunoCAP (Phadia AB, Uppsala, Sweden). The test was considered positive if allergen-specific IgE levels were = 0·7 kUA/l.

Blood sample treatment and in vitro activation

Blood sample collection, separation of mononuclear cells and in vitro activation was performed as described previously [8]. In brief, the cells were incubated either with medium alone or with the addition of the microbial stimuli LPS (Escherichia coli B, 1 ng/ml; Sigma Aldrich, Stockholm, Sweden) or PGN (Staphylococcus aureus, 1 µg/ml; Sigma Aldrich). For analysis of cell surface markers by flow cytometry the cells were stimulated for 3 h (n = 20) and for measurement of secreted cytokines the cells were stimulated for 24 h.

To study phosphorylation of p38-MAPK in monocytes, 106 cells/ml were resuspended in tissue culture medium and incubated (at 37°C with 5% CO2) for 2 h before being stimulated during 30 min with either 10 ng/ml LPS, 10 µg/ml PGN or in medium alone. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin (both from Sigma Aldrich) served as positive control.

Flow cytometric analysis

For surface detection, cells were stained for CD14, TLR-2 and TLR-4 as described previously [8], with the additional staining of anti-CD16 Alexa Fluor 647 (IgG1, 3G8; BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA). For analysis, gating was performed on the live cell population of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) based on forward- and side-scatter properties. The monocyte subsets were determined thereafter based on CD14 and CD16 staining. Relative fluorescence intensity was determined by subtracting the geometric mean fluorescence intensity (GeoMFI) of the isotype control from the sample.

In order to detect phosphorylated p38-MAPK in monocytes, BD™ Phosflow Phosphorylation State Analysis (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) was performed as described previously [11]. Gating was performed on live CD14+ monocytes that were analysed for phosphorylated p38-MAPK. The results are based on GeoMFI values and are analysed as stimulation index (GeoMFI of phosphorylated p38-MAPK in stimulated CD14+ monocytes/GeoMFI of phosphorylated p38-MAPK in unstimulated CD14+ monocytes). All flow cytometric data were acquired by a BD fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACSCalibur) flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and analysed further with the software BD CellQuest™Pro version 5.2.1.

Cytometric bead array

For measuring the release of TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and IL-12p70 into the culture supernatants, the cytometric bead array (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) technique was used as described previously [8]. The assay sensitivities were as follows: IL-1β (7·2 pg/ml), IL-6 (2·5 pg/ml), IL-8 (3·6 pg/ml), IL-10 (3·3 pg/ml), IL-12p70 (1·9 pg/ml) and TNF-α (3·7 pg/ml).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with statistica 7.1 software (Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Statistical advice was provided by the Division of Mathematics at Stockholm University. For demographic data, Fishers's exact test was used to test for differences between the two groups. For all results the Mann–Whitney U-test was used to test for differences between groups. The difference was considered significant if P < 0·05.

Results

No differences in unstimulated monocyte subsets or in their TLR levels between allergic and non-allergic children

Responses to microbial stimuli have shown to be of importance for susceptibility and severity of allergic diseases. Diverse expression of TLRs on CD14+CD16− and CD14+CD16+ monocytes implies that differences in the relative numbers of these subsets could influence the anti-microbial responses. We therefore aimed at comparing the composition of the monocyte population in 5-year-old allergic and non-allergic children.

The two subsets were found in equal amounts among allergic and non-allergic children (data not shown). In both groups the CD14+CD16+ subset represented 9% of all CD14 positive cells. After stimulation, the CD14+CD16+ subset was reduced drastically, and only made up ∼2% (LPS) and ∼4% (PGN) of all monocytes in both groups.

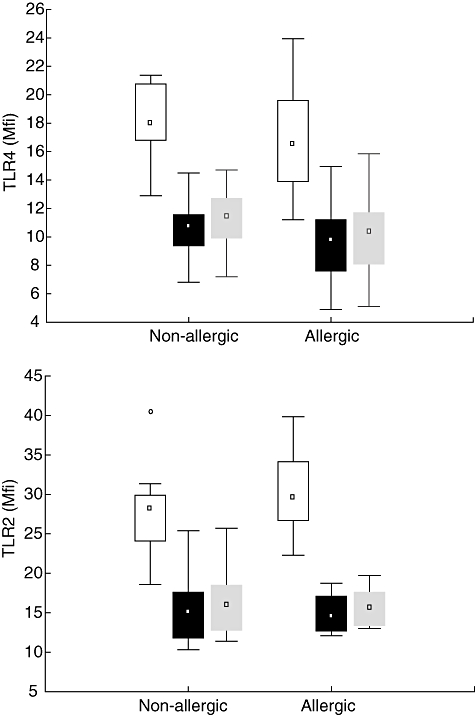

There were further no statistical differences in TLR-4 surface expression between the two groups for unstimulated cells (Fig. 1a). However, the CD14+CD16+ subset had a higher expression of TLR-4 compared with the CD14+CD16− subset in both groups of children (65% higher expression in non-allergic individuals and 69% in allergic individuals) (Fig. 1a). For TLR-2, there were no statistical differences in surface expression between the allergic and non-allergic children in either of the two subsets (Fig. 1b), but as for TLR-4 there were differences in expression between the two monocytic subsets. For non-allergic individuals TLR-2 expression in the CD14+CD16+ subset was 85% higher compared with expression in the CD14+CD16− subset, while for allergic individuals there was a 104% higher expression in the CD14+CD16+ compared with expression in the CD14+CD16− subset.

Fig. 1.

Cell-surface expression of (a) Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 and (b) TLR-2 in the different monocyte populations in allergic (n = 10) and non-allergic (n = 10) 5-year-old children. Boxes cover the middle 50% of the data values between the 25th and 75th percentiles, the central square being the median. Lines extend to non-outlier max and non-outlier min. ° = outliers, □ CD14+CD16+, ▪ CD14+CD16− All CD14 positive cells.

All CD14 positive cells.

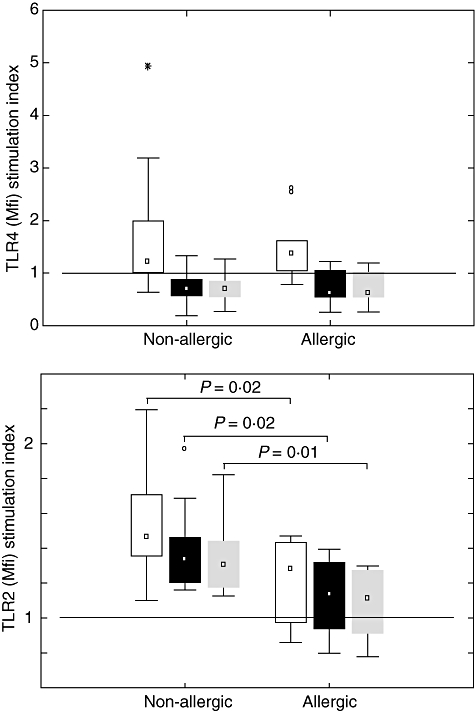

Impaired TLR-2 signalling in response to PGN in allergic children

Monocytic surface expression of TLRs following activation has not been shown convincingly to differ between allergic and non-allergic individuals. The age of the child is most probably an important aspect when investigating TLR levels and regulation and in this study, to our knowledge, we are the first to investigate children at the age of 5. Our results show that after stimulation with LPS, TLR-4 was up-regulated in the CD14+CD16+ subset, while in the CD14+CD16− subset TLR-4 was down-regulated (Fig. 2a). There were no statistical differences between the two groups.

Fig. 2.

Stimulation index [ratio of Toll-like receptor (TLR) expression in stimulated/unstimulated monocytes] for (a) TLR-4 after lipopolysaccharide stimulation and (b) TLR-2 after peptidoglycan stimulation in the different monocyte populations in allergic (n = 10) and non-allergic (n = 10) 5-year-old children. ° = outliers and * = extremes. The line represents stimulation index = 1, which means no up-/down-regulation. □ CD14+CD16+, ▪ CD14+CD16− All CD14 positive cells.

All CD14 positive cells.

However, after stimulation with PGN there was a significantly (P = 0·01) lower up-regulation of TLR-2 in CD14 positive cells from allergic compared with non-allergic individuals (Fig. 2b). If the CD14 positive cells were divided into two subsets on the basis of CD14 and CD16 expression, the level of up-regulation was significantly lower in the allergic group than the non-allergic group for both subsets (CD14+CD16+, P = 0·02, CD14+CD16−, P = 0·02) (Fig. 2b).

No differences in p38-MAPK activity in CD14+ monocytes

We have shown previously that 2-year-old children with allergic mothers have a defective PGN response in terms of p38-MAPK activity in CD14+ monocytes [11]. Despite finding an impaired TLR-2 response to PGN in allergic children in this study of 5-year-old children, we did not observe any differences in the p38-MAPK activity between allergic and non-allergic children. This holds true for unstimulated cells as well as stimulated cells (data not shown).

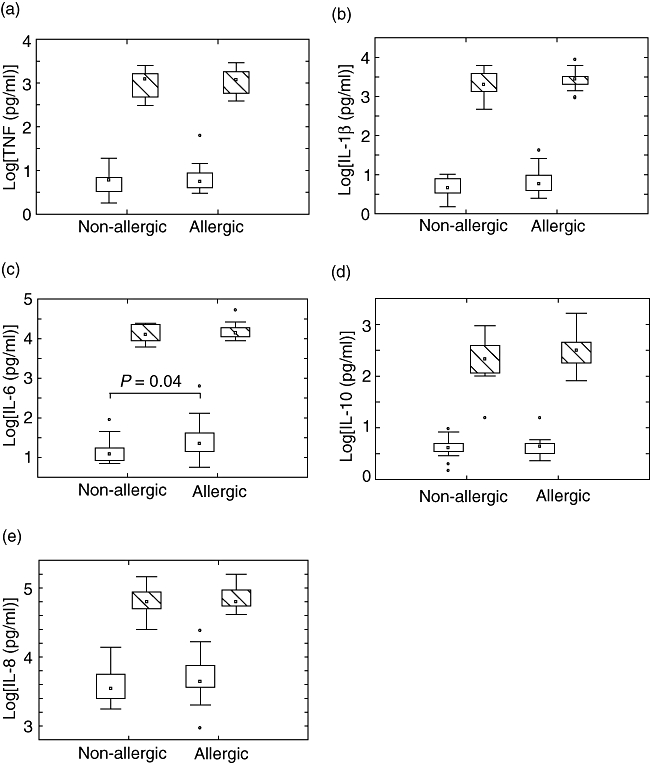

Cytokine responses following LPS and PGN stimulation

We and others have shown that there is an impaired proinflammatory cytokine response to TLR-2 stimulation in cells from children [8] with allergic heredity and in adults [9] with allergic disease. Because, in this study, we observed an impaired TLR-2 response to PGN for 5-year-old allergic children, we further aimed to examine cytokine production in PBMCs in response to PGN stimulation.

For unstimulated cells, there were no differences for TNF (Fig. 3a), IL-1β (Fig. 3b), IL-10 (Fig. 3d) or IL-8 (Fig. 3e) production between allergic and non-allergic children, and IL-12p70 production was below the detection limit. However, allergic children produced significantly more IL-6 (P = 0·04) than non-allergic children (Fig. 3c), even though there is pronounced variability. For PGN stimulated cells there were no statistical differences for any of the cytokines (3a–e). However, if the cytokine levels after stimulation are presented as a stimulation index (levels after stimulation/levels for unstimulated cells) there is a weak indication (P = 0·18) of a decreased IL-6 response in allergic individuals compared with non-allergic subjects.

Fig. 3.

Levels of (a) tumour necrosis factor, (b) interleukin (IL)-1β, (c) IL-6, (d) IL-10 and (e) IL-8 after peptidoglycan stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from allergic (n = 16) and non-allergic (n = 17) 5-year-old children. ° = outliers, □ unstimulated,  PGN stimulated.

PGN stimulated.

Discussion

Various inflammatory diseases including asthma and atopic eczema have shown an expansion of the CD14+CD16+ subset [12]. In this study, we investigated the distribution of the two major monocyte populations CD14+CD16− and CD14+CD16+ in allergic and non-allergic 5-year old children and their responses to microbial stimulation. Our results of a similar distribution of the monocyte subpopulations between allergic and non-allergic children diverge from some other studies describing a difference [15,16], but are also supported by a study showing no connection between allergic status and monocytic subsets [9].

The interpretation of differences in monocytic subsets should, however, be taken with some caution, because instrument settings and gating during flow cytometric analysis can differ between different studies [12]. It should also be emphasized that expansion of the CD14+CD16+ inflammatory subset seems to be a transient state that is connected to ongoing inflammation, as the subset decreases with improving symptoms [16]. The children participating in this study had no severe symptoms at the time of sampling, which could be a reason for the lack of differences. However, it should be noted that the only child who was allergic to timothy, sampled in May, had a normal level of the CD14+CD16+ subset, but the highest level of the CD16 molecule on the surface of monocytes in the allergic group. The expansion of the CD14+CD16+ inflammatory subset might not be the cause of disease but rather a marker of inflammation, which makes the frequency of these cells somewhat less important when studying their role in connection with susceptibility of disease.

For unstimulated cells we saw no differences in terms of TLR-2/TLR-4 levels in either of the monocytic subsets in connection to allergic disease. This is in agreement with other studies [8,9] showing that, although there might be differences in terms of cytokine production, the receptor levels do not confirm this difference automatically. One earlier study showed a higher expression of TLR-4, but not TLR-2 levels for the CD14+CD16+ subset [14]. However, another study showed higher levels of TLR-2, and not TLR-4 [18]. Here we report a higher level of TLR-2 as well as TLR-4 in the CD14+CD16+ subset in both groups of children. Studies of monocytes that do not differentiate between the two subpopulations (CD14+CD16− and CD14+CD16+) may show different results of TLR expression levels and regulation depending on the distribution of the two subsets. Figures 1 and 2 show clearly that when the monocytes are phenotyped only with regard to CD14 and not CD16, the results resemble those of the CD14+CD16− population. Even though the CD14+CD16+ subpopulation is only 5–15% of all CD14 positive cells, it may play an important role as it displays substantially higher levels of TLRs, and because the receptor regulation is different.

We and others have shown previously that there seems to be a selective impairment of TLR-2 responses in terms of cytokine production in children having allergic heredity [8,11,19], or in adults with allergic disease [9]. Age has shown to be of importance for innate immune responses in mice [20,21], making interpretations from different studies in humans difficult because of study populations with different ages. The immune system of the growing child is undergoing multiple important maturation steps. A study in humans showed that age can affect responses to LPS stimulation in terms of IL-12p70 production; however, there were no differences in TLR levels [22]. In this study we investigated responses to microbial stimuli (LPS and PGN) in PBMCs from 5-year-old children, as this time-point would reflect a state where children have a more manifested allergic disease in comparison with 2-year-old children whom we have investigated previously [11].

Studies have shown that genetic variations [23] and mRNA levels of TLR-2 [3] are linked to allergic disease. Even though we found no differences in TLR levels, in our previous study IL-6 responses to PGN were impaired in CBMCs from children with different allergic heredity. Although this could be explained by the questioned role of PGN in TLR-2 signalling [24], it is now recognized that there is cross-talk between nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-2 and TLR-2 in response to PGN [25]. A study in mice also confirmed that PGN acts on TLR-2 as PGN induced proliferation in wild-type mice, but not in TLR-2 knock-out mice [26]. In a later study we further detected a reduced signalling capacity in 2-year-old children in response to PGN in terms of p38-MAPK phosphorylation [11]. A very recent study of human alveolar macrophages confirmed that lack of changes in surface TLR levels upon stimulation with TLR-2 and TLR-4 agonists do not exclude changes in signalling in terms of p38-MAPK and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [27].

In the present study we observed a reduced up-regulation of TLR-2 in response to PGN for allergic children compared with non-allergic children (P = 0·02). A very recent study found the same defective up-regulation of both TLR-2 and TLR-4, together with a reduced up-regulation of human leucocyte antigen D-related in monocytes from patients with atopic dermatitis in response to S. aureus enterotoxin B [22], a compound that acts upon both TLR-4 and TLR-2 in human monocytes. Taken together, this could illustrate an activated monocytic state in allergic individuals that seems to lead to hyporesponsiveness to further stimulation. As the monocytic subsets were not altered for allergic individuals in this study, the lower TLR-2 response in monocytes for allergic individuals seems to hold true for both subsets studied.

It is known that cytokines that are connected to allergic disease, such as IL-4 and IL-13, down-regulate TLR-4-mediated activation [28]. In this study we could not observe any differences in TLR-4 signalling attributed to allergic disease, showing that the allergic phenotype in this study seems to have a larger impact on TLR-2 rather than TLR-4 signalling. Another interesting result concerning TLR-4 expression in response to LPS is that in the CD14+CD16+ subset TLR-4 was up-regulated, while in the CD14+CD16− subset TLR-4 was down-regulated, regardless of allergic status. There have been earlier conflicting results regarding the regulation of TLR-4 in response to LPS [29]. A reason for the diverging results could be that much of the evidence for TLR regulation is based on mRNA levels, and the cell surface expression of TLR-4 does not parallel data obtained at the mRNA level [30]. Our results of different regulation of TLR-4 in the two monocytic subsets also show that gating and phenotyping of monocytes when performing this type of experiment is a crucial event for interpretation of the results obtained.

Even though allergic children had reduced TLR-2 up-regulation in response to PGN we observed no differences in p38-MAPK activity. The reason for this remains unclear; however, it should be emphasized that the signalling cascade in response to PGN involves many other pathways that could have compensatory roles [25]. An alternative explanation could be that the altered TLR regulation for allergic children in this study does not have an effect on the signalling pathway. A recent study in mice illustrates the complex interplay between TLR signalling and p38-MAPK activity when they show that an excess p38-MAPK activity can be inhibitory for TLR-induced production of proinflammatory cytokines [21].

As we had found previously a defective IL-6 response to PGN in cells from children with allergic heredity, at birth and at 2 years of age, in this study we analysed the production of cytokines in response to PGN at the age of 5 years. For unstimulated cells there was a higher production of IL-6 for allergic children. IL-8 and IL-1β levels were also slightly elevated for the allergic children, although not statistically significant. The pattern of higher spontaneous proinflammatory cytokines in allergic children shows that once the disease is declared there is a greater inflammatory state of the immune system in allergic children compared with non-allergic children.

Our results of no differences in proinflammatory cytokine production after stimulation between allergic and non-allergic individuals are supported by a study in 2006, showing that TNF secretion was similar in women with and without atopy [19]. However, another study using a different ligand (Pam3Cys) for TLR-2 activation observed a diminished TNF response in allergic adults compared with non-allergic individuals [9]. This discrepancy could be the affect of the different microbial stimuli used in the studies. Nevertheless, a study showing decreased allergic symptoms in mice after stimulation with two different TLR ligands (PGN and PamCys) demonstrated that TLR-2-mediated suppression of allergic responses is independent of the TLR2 agonist administered [31], showing that the final biological response is the same.

Even though we detected no differences in levels of cytokines after stimulation that could be attributed to allergic disease, the stimulation index can be used for examining the responsive capacity of the cells. When dividing the levels for stimulated cells by the values for unstimulated cells in order to look at the responsive capacity of the cells, there is indication of a decreased IL-6 response in allergic individuals, which strengthens our hypothesis of a hyporesponsive TLR-2 phenotype in allergic children.

In conclusion, the allergic subjects in this study have a higher level of spontaneous IL-6 production and a lower TLR-2 response to PGN after PGN stimulation. Taken together, these results illustrate that the allergic individuals have a monocytic population that seems activated but hyporesponsive to microbial stimulation.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge all the families participating in the study. We also thank Monica Nordlund, Anna Stina Ander, Jacob T. Minang and Yvonne Sundström for their valuable assistance and Jan-Olov Persson for providing excellent statistical support. This study was supprted by the Swedish Asthma and Allergy Association's Research foundation, the Swedish Research Council (Medicine) grant no 74X-15160, the Swedish Medical Society, the Golden Jubilee Memorial Foundation, the Crown-princess Lovisa & Axel Tielman-, Golje-, Hesselman-, Vardal-, Swärd/Eklund- and the Åhlén foundations.

References

- 1.von Mutius E. Asthma and allergies in rural areas of Europe. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:212–16. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-028AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krauss-Etschmann S, Hartl D, Heinrich J, et al. Association between levels of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and CD14 mRNA and allergy in pregnant women and their offspring. Clin Immunol. 2006;118:292–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fageras Bottcher M, Hmani-Aifa M, Lindstrom A, et al. A TLR4 polymorphism is associated with asthma and reduced lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-12(p70) responses in Swedish children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:561–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad-Nejad P, Mrabet-Dahbi S, Breuer K, et al. The Toll-like receptor 2 R753Q polymorphism defines a subgroup of patients with atopic dermatitis having severe phenotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:565–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novak N, Yu CF, Bussmann C, et al. Putative association of a TLR9 promoter polymorphism with atopic eczema. Allergy. 2007;62:766–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ege MJ, Bieli C, Frei R, et al. Prenatal farm exposure is related to the expression of receptors of the innate immunity and to atopic sensitization in school-age children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:817–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amoudruz P, Holmlund U, Malmstrom V, et al. Neonatal immune responses to microbial stimuli: is there an influence of maternal allergy? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1304–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasannejad H, Takahashi R, Kimishima M, Hayakawa K, Shiohara T. Selective impairment of Toll-like receptor 2-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production by monocytes from patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Shepherd EG, Nelin LD. MAPK phosphatases – regulating the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:202–12. doi: 10.1038/nri2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saghafian-Hedengren S, Holmlund U, Amoudruz P, Nilsson C, Sverremark-Ekstrom E. Maternal allergy influences p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase activity upon microbial challenge in CD14(+) monocytes from 2-year-old children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:449–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The CD14+ CD16+ blood monocytes: their role in infection and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:584–92. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitchens RL, Thompson PA. Modulatory effects of sCD14 and LBP on LPS–host cell interactions. J Endotoxin Res. 2005;11:225–9. doi: 10.1179/096805105X46565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skinner NA, MacIsaac CM, Hamilton JA, Visvanathan K. Regulation of Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 on CD14dimCD16+ monocytes in response to sepsis-related antigens. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;141:270–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivier A, Pene J, Rabesandratana H, Chanez P, Bousquet J, Campbell AM. Blood monocytes of untreated asthmatics exhibit some features of tissue macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;100:314–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03670.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novak N, Allam P, Geiger E, Bieber T. Characterization of monocyte subtypes in the allergic form of atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome. Allergy. 2002;57:931–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.23737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nilsson C, Linde A, Montgomery SM, et al. Does early EBV infection protect against IgE sensitization? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:438–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwahashi M, Yamamura M, Aita T, et al. Expression of Toll-like receptor 2 on CD16+ blood monocytes and synovial tissue macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1457–67. doi: 10.1002/art.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaub B, Campo M, He H, et al. Neonatal immune responses to TLR2 stimulation: influence of maternal atopy on Foxp3 and IL-10 expression. Respir Res. 2006;7:40. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chelvarajan RL, Liu Y, Popa D, et al. Molecular basis of age-associated cytokine dysregulation in LPS-stimulated macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:1314–27. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0106024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chelvarajan L, Popa D, Liu Y, Getchell TV, Stromberg AJ, Bondada S. Molecular mechanisms underlying anti-inflammatory phenotype of neonatal splenic macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:403–16. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0107071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandron M, Aries MF, Boralevi F, et al. Age-related differences in sensitivity of peripheral blood monocytes to lipopolysaccharide and Staphylococcus aureus toxin B in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:882–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eder W, Klimecki W, Yu L, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 as a major gene for asthma in children of European farmers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:482–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Travassos LH, Girardin SE, Philpott DJ, et al. Toll-like receptor 2-dependent bacterial sensing does not occur via peptidoglycan recognition. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:1000–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strober W, Murray PJ, Kitani A, Watanabe T. Signalling pathways and molecular interactions of NOD1 and NOD2. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nri1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaub B, Bellou A, Gibbons FK, et al. TLR2 and TLR4 stimulation differentially induce cytokine secretion in human neonatal, adult, and murine mononuclear cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2004;24:543–52. doi: 10.1089/jir.2004.24.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H, Cowan MJ, Hasday JD, Vogel SN, Medvedev AE. Tobacco smoking inhibits expression of proinflammatory cytokines and activation of IL-1R-associated kinase, p38, and NF-{kappa}B in alveolar macrophages stimulated with TLR2 and TLR4 agonists. J Immunol. 2007;179:6097–106. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller T, Terada T, Rosenberg IM, Shibolet O, Podolsky DK. Th2 cytokines down-regulate TLR expression and function in human intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:5805–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan H, Cook JA. Molecular mechanisms of endotoxin tolerance. J Endotoxin Res. 2004;10:71–84. doi: 10.1179/096805104225003997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adib-Conquy M, Cavaillon JM. Gamma interferon and granulocyte/monocyte colony-stimulating factor prevent endotoxin tolerance in human monocytes by promoting interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase expression and its association to MyD88 and not by modulating TLR4 expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27927–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velasco G, Campo M, Manrique OJ, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 or 2 agonists decrease allergic inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:218–24. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0435OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]