Abstract

The established view that schizophrenia may have a favorable outcome in developing countries has been recently challenged; however, systematic studies are scarce. In this report, we describe the clinical outcome of schizophrenia among a predominantly treatment-naive cohort in a rural community setting in Ethiopia. The cohort was identified in a 2-stage sampling design using key informants and measurement-based assessment. Follow-up assessments were conducted monthly for a mean duration of 3.4 years (range 1–6 years). After screening 68 378 adults, ages 15–49 years, 321 cases with schizophrenia (82.7% men and 89.6% treatment naive) were identified. During follow-up, about a third (30.8%) of cases were continuously ill while most of the remaining cohort experienced an episodic course. Only 5.7% of the cases enjoyed a near-continuous complete remission. In the final year of follow-up, over half of the cases (54%) were in psychotic episode, while 17.6% were in partial remission and 27.4% were in complete remission for at least the month preceding the follow-up assessment. Living in a household with 3 or more adults, later age of onset, and taking antipsychotic medication for at least 50% of the follow-up period predicted complete remission. Although outcome in this setting appears better than in developed countries, the very low proportion of participants in complete remission supports the recent observation that the outcome of schizophrenia in developing countries may be heterogeneous rather than uniformly favorable. Improving access to treatment may be the logical next step to improve outcome of schizophrenia in this setting.

Keywords: psychosis, remission, developing country, prognosis, prospective study

Introduction

The prevailing view of the outcome of schizophrenia in developing countries stems from a series of studies conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO). These studies identified setting (developed vs developing country) and nature of onset of illness (acute vs gradual) to be the key predictors of outcome in schizophrenia.1,5 Specifically, it was reported that the outcome of schizophrenia was significantly more favorable in developing than developed countries. With some qualifications, further reanalysis of the second WHO Study, the Determinants of Outcome in Severe Mental Disorders (DOSMD), confirmed this differential outcome.6 The recently published report of the 15- to 26-year follow-up study of earlier WHO studies, the International Study of Schizophrenia, also found a similarly favorable outcome in developing country settings.7 In this report, summarizing the findings of the WHO studies, the authors concluded that “for all variables considered, the schizophrenic patients in Ibadan, Agra, and Cali (all centres in developing countries) tended to have a better outcome on average than the schizophrenic patients in the other six centers.”

The WHO studies are among the best-designed and -executed outcome studies of psychosis. However, few methodological limitations need to be considered in interpreting the conclusions from the studies. First, only 3 developing countries (India, Colombia, and Nigeria) were included in the original series of the WHO studies; secondly, although the DOSMD study was epidemiological in approach, all cases were recruited in the context of service contact (formal and informal contact).3 In countries like Ethiopia with underdeveloped health infrastructure, patients with schizophrenia have little access to modern health facilities.8 As will be shown later, a large proportion of cases may not even access intervention from the informal sector. This is important because help seeking has a major bearing on outcome in these settings.9 Thus, omitting nonservice contact cases may favor good outcome.10 Thirdly, despite the application of well-defined operational criteria, broad diagnostic classes were incorporated together to represent schizophrenia. Specifically, among the sample from developing countries, 13.7% were not diagnosed as having schizophrenia (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, class 295) and 46.1% were not classed under the narrowly defined schizophrenia (CATEGO S+).3 This underlying heterogeneity in illness construct may affect the validity of conclusions regarding outcome.

Crucially, further evidence highlighting the complexity and heterogeneity of the outcome of schizophrenia in developing countries has emerged from recent reviews.11,12 One of these reviews, a synthesis of 23 outcome studies from 11 low- and middle-income countries conducted independently of the WHO, demonstrated the variations in clinical and functional outcome of schizophrenia in these settings.11 The report highlighted the need to carefully consider the role of families, gender effects, and the role of attrition through premature death in the outcome of schizophrenia. Nevertheless, the studies reviewed in the report were heterogeneous in methodology. It could thus be argued that any variation in outcome was a consequence of methodological heterogeneity of included studies rather than differences in outcome of schizophrenia per se.13

In this context, the aims of our study were to describe the medium-term outcome of schizophrenia and its sociodemographic and clinical predictors in a predominantly rural setting in Ethiopia. Additionally, we aimed to explore whether our initial finding of a high prevalence of schizophrenia among men8 compared with women may be partly accounted for by higher mortality, migration, or other causes of attrition among women. We postulated that if the various causes of attrition affected men and women differentially prior to inclusion into the study, they might have lead to differential prevalence between the sexes. Although this does not necessarily follow, if such differential attrition continues to operate during follow-up, it might offer an indirect clue regarding the differential prevalence rate. We were aware that this exploration was limited from the outset because of the small number of female patients and the short duration of follow-up. We were also aware that this exploration would only offer a very limited explanation for the difference in prevalence in this setting.

Methods

A detailed description of the setting and methods is given elsewhere.8,14

Setting and Cohort Identification

The study was conducted in Butajira, a predominantly rural district located 132 km south of the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa. Butajira district hosts a demographic surveillance site (DSS) that monitors vital health statistics. This offers a unique opportunity to standardize relevant events against the routinely gathered data of the DSS. All 45 subdistricts of Butajira, except one, were included. One subdistrict was excluded because of physical inaccessibility. Only the 4 subdistricts, representing 10.9% of our study population, came from a rural town.

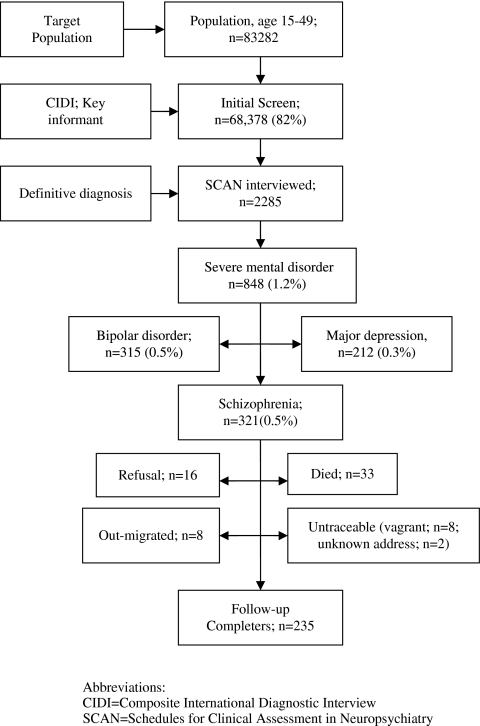

The cohort was identified through a 2-stage sampling design that consisted of an initial screen to identify potential cases with severe mental disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression) and a second confirmatory assessment stage. The initial screen targeted the entire adult population of the 44 subdistricts, ages 15–49, estimated to be 83 282.15 This initial screening involved a supervised, door-to-door survey using the affective and psychoses modules of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 2.1.16 The CIDI was administered to 68 378 individuals (82.1% of total population). Key informants selected from each village augmented case identification with the CIDI. We have separately reported on the performance of rating instruments and key informants.17 In the second stage, confirmatory diagnostic assessment was conducted using the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN), version 2.1.18 To be eligible for SCAN interview, participants should have had at least one psychotic symptom on the CIDI modules or be identified by key informants as suffering from severe mental illness.

Consenting individuals who resided in the study district for at least 6 months and receiving diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10)19 after a SCAN assessment were included in the cohort. Of those interviewed with SCAN, 321 were diagnosed with schizophrenia and 315 with bipolar disorder (figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Cohort Identification and Follow-up of Cases with Schizophrenia.

The upper age limit of 49 years was chosen to increase efficiency because case yield was expected to be reasonably high. Moreover, life expectancy at birth in the region was reported to be 50 years.20 Those nonavailable for initial screening predominantly resided in rural areas (18.7%) than in the town (13.6%). Most of those who were not available for screening were out of the district for work-related businesses. This was the reason for the nonavailability of 65% of nonscreened individuals.

Administration of Instruments

The CIDI (version 1.0) was initially translated into Amharic and back translated and was tested for feasibility of use, acceptability, and reliability. The assessment showed that the CIDI was acceptable and feasible with high interrater reliability (κ = 0.87 for any psychiatric diagnosis and 0.82 for schizophrenia).21 This version of the CIDI was further updated according to versions 2.0 and 2.1. For the administration of the CIDI, 15 male and 15 female high school graduates were employed. These were recruited through a competitive process involving written test and interviews, enabling employment of the most competent lay interviewers. The interviewers were then trained for 2 weeks by professionals trained through a WHO collaborative center from The Netherlands. The SCAN was translated on a consensus-based model after an initial translation by 2 resident psychiatrists. The SCAN was then piloted in a similar rural community setting before being applied among the study population. As a further step to assess the reliability of the SCAN diagnoses, 2 experienced psychiatrists rated the records. The agreement of the psychiatrists with the SCAN diagnoses was 100% for schizophrenia (κ = 1.0) and very high for the other major mental disorders (κ = 0.9 and 0.8 for bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder, respectively).22

The Follow-up

Follow-ups were conducted at the research follow-up base in Butajira, in rural clinics near patients' residence and at patients' residence. The follow-ups were facilitated by research field workers, who initially worked as lay interviewers for the CIDI. The research workers were allocated patients residing in about 2 subdistricts. These workers had very good relationship with patients and their families. The research workers invited and escorted patients to the follow-up clinics during follow-up assessments. When getting patients to follow-up clinics was not possible, the psychiatry resident visited patients at their home. These assertive elements facilitated engagement in follow-ups. Clinical outcome was assessed by psychiatric residents or experienced psychiatry nurse practitioners through a monthly clinical assessment and an annual structured interview using the SCAN. At these monthly assessments, the clinical state of patients over the preceding month (presence or absence of psychotic symptoms, use of medication, and whether patients were in episode or remission [complete or partial]) was recorded. Such systematic follow-ups allowed characterization of the course of schizophrenia in terms of clinical remission and relapse and to determine whether patients had been taking medication. Medications were made freely available to the patients through the study project and were provided on a routine basis depending on clinical indication. Only first-generation psychotropic medications were available in the country and thus offered to participants. The cohort was followed up for a mean duration of 3.4 years (range 1–6 years).

Data Processing and Analysis

A full-time editor first scrutinized all interview forms in the field for completeness, accuracy, and consistency. Data were then entered using the Epi-Info (version 6) and CIDI and SCAN data entry programs. Double data entry and consistency checks were employed to assure the quality of data entry.

To describe the general features of course and outcome of our cohort, we used a similar pattern of analysis to the DOSMD study.3 Person-month analysis was used to estimate the proportion of time spent in various clinical and treatment categories. That is, the proportion of the total length of follow-up period during which a subject was (1) on antipsychotic medication (2) in complete remission (3) in partial remission, and (4) in a psychotic episode. Where monthly assessment data were missing, the person-time for the missing period was omitted from both numerator and denominator. In the logistic regression model, complete remission for more than 50% of an individual's follow-up time was taken as the outcome variable and sociodemographic (sex, age, marital status, education, residence, household size, and religion) and clinical characteristics (treatment with antipsychotics, type of onset, duration of illness, age of onset, and subtype of schizophrenia) were entered as explanatory variables in the model. We also assessed whether history of treatment with antipsychotics and from informal sectors (traditional and religious healers) at inclusion predicted treatment during follow-up and remission. Type of onset was categorized in 2 groups. Acute onset was defined as onset of schizophrenia within 1 month of onset of symptoms. Onset longer than 1 month was classified as insidious. Duration of illness was also categorized into 2 groups. Illness lasting more than 2 years was considered chronic while illness of shorter duration was considered acute. In the regression analysis, we conducted bivariate logistic regression followed by stepwise regression method with backward selection method.

Complete remission is a meaningful indicator of recovery and 50% duration in such a state may be assumed a minimum duration required for a relatively satisfactory outcome. Both complete and partial remissions were considered for the month leading to the monthly assessment. Complete remission was defined as absence of both positive and negative symptoms for at least 1 month while partial remission was defined as reduction in symptom severity such that the patient no longer fulfills the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia though experiencing ongoing symptoms.

Ethical review committees from the Department of Community Health and the Faculty of Medicine, Addis Ababa University, approved the study. All CIDIs were administered by same-sex interviewers, and all interviews were conducted in private. All participants provided consent to be interviewed.

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Retention

A total of 68 378 adults (42.5% males) were assessed for case detection. This slightly lower rate of men is not a reflection of the sex distribution of study population but was so because more men were unavailable for the initial screening interview. After the second-stage interview (SCAN interview), 321 cases were identified with schizophrenia—a prevalence of 4.7/1000. Of these, 318 cases (99.0%) constituted the actual cohort having complete baseline information. Cases were predominantly males (82.7%), below 35 years of age (75%), rural dwellers (73%), lived in a household with 3 or more adults (53.8%), and with at least some primary education (54.2%) (table 1). Over 53% had never been married. Paranoid and undifferentiated schizophrenia were the 2 most frequent diagnostic subtypes (table 1). Illness onset was acute in about two-thirds of cases. The mean duration of illness of cases was 7.6 years ranging from 0 to 30 years. Just over 10% of cases (n = 33) had ever received antipsychotic medications and 37.4% (n = 119) had sought treatment from informal sectors (eg, traditional and religious healers) at baseline (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Cases with Schizophrenia in Butajira, Ethiopia

| Characteristics (n)a | Total Population | % |

| Sex (318) | ||

| Male | 263 | 82.7 |

| Female | 55 | 17.3 |

| Age (318), y | ||

| 15–24 | 68 | 21.4 |

| 25–34 | 142 | 44.6 |

| 35–49 | 108 | 34.0 |

| Marital status (318) | ||

| Single | 168 | 52.8 |

| Married | 91 | 28.6 |

| Other | 59 | 18.6 |

| Education (273) | ||

| No formal education | 125 | 45.8 |

| Elementary education | 91 | 33.3 |

| Secondary and above | 57 | 20.9 |

| Residence (308) | ||

| Urban/semiurban | 75 | 24.4 |

| Rural | 233 | 75.6 |

| Household size (318) | ||

| Less than 3 persons | 147 | 46.2 |

| 3 or above | 171 | 53.8 |

| Religion (300) | ||

| Muslim | 231 | 77.0 |

| Christian | 69 | 23.0 |

| On antipsychotics (318) | ||

| 50% of follow-up time or longer | 70 | 22.0 |

| Other | 248 | 78.0 |

| Type of onset (232) | ||

| Acute | 156 | 67.2 |

| Insidious | 76 | 32.8 |

| Duration of illness (313), y | ||

| 2 or less | 80 | 25.6 |

| Longer than 2 | 233 | 74.4 |

| Age of onseta (n = 295), y | ||

| 19 or less | 87 | 29.5 |

| 20–29 | 153 | 51.9 |

| 30 or more | 55 | 18.6 |

| Clinical subtypes (n = 318) | ||

| Paranoid | 108 | 34.0 |

| Hebephrenic | 17 | 5.4 |

| Catatonic | 23 | 7.2 |

| Undifferentiated | 119 | 37.4 |

| Residual | 44 | 13.8 |

| Other | 7 | 2.2 |

| Treatment experience at baseline | ||

| Antipsychotic treatment | 33 | 10.4 |

| Treatment from informal sectorb | 119 | 37.4 |

Total number in some categories is less than 318 because of missing values.

Includes traditional and religious healers.

A large proportion of cases were retained in follow-up (figure 1). Including all causes of attrition, 85.4% of the sample was followed up for at least 2 years (table 2). At the time of reporting, 33 cases (10.4%) had died, 22 (7%) had out migrated, 16 (5.1%) had refused to participate, and 10 (3.2%) were untraceable either because of change of address (0.6%) or homelessness (2.5%). The total loss to follow-up from various causes was much higher in men (n = 75) than women (n = 6). Death and out migration were higher in male patients (10:1), and all cases refusing follow-up were men (table 2).

Table 2.

Gender-Specific Profile of the Various Follow-up States of Patients

| Sex | Number (Baseline) | Follow-up Duration, y | Deceased | Out Migrated | Refusal | Untraceable | Completers | Total (%) |

| Male | 47 | ≤1 | 15 | 17 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 14.9 |

| 166 | 2–4 | 14 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 140 | 52.5 | |

| 49 | 5–6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 46 | 15.5 | |

| Total (N) | 262 | 30 | 20 | 16 | 9 | 187 | 82.9 | |

| Female | 5 | ≤1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1.6 |

| 33 | 2–4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 10.4 | |

| 16 | 5–6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 5.1 | |

| Total (N) | 54 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 48 | 17.1 | |

| Overall total | 33 (10.4) | 22 (7.0) | 16 (5.1) | 10 (3.2) | 235 (74.4) | 316 (100) | ||

| Person-year contributed (%) | 61 (5.6) | 33 (3.0) | 32 (2.9) | 17 (1.6) | 950 (86.9) | 1093 (100) | ||

Clinical Outcome

The general course of illness, pattern of remission, and the percentage of time cases spent in different clinical states are depicted in tables 3 and 4. The majority of patients had a remitting course of illness with nearly 70% of patients achieving complete remission at least once. On the other hand, about a third (30.8%) had continuous illness suffering either from residual symptoms or psychotic episodes. A near-continuous remission was achieved only by a small proportion of cases (5.7%), and less than a fifth (17.3%) of cases experienced remission for about half of the follow-up period (tables 3 and 4). Overall, our findings are comparable to the findings of the WHO studies in developing countries. However, the very low proportion of cases with continuous remission during follow-up (table 4) is the main exception.

Table 3.

Percentage of Follow-up Time Spent in Various Clinical States or During Which Patients Were on Antipsychotic Medications, Butajira, Ethiopia

| No. of Patients | % Time Spent in Different Clinical and Treatment States |

|||||||

| 0 | 1–5 | 6–15 | 16–45 | 46–75 | 76–100 | Total | ||

| Clinical state | ||||||||

| Complete remission | 318 | 30.8 | 4.4 | 17.3 | 30.2 | 11.6 | 5.7 | 100.0 |

| Partial remission | 318 | 38.1 | 17.0 | 20.4 | 19.8 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 100.0 |

| Psychotic episode | 318 | 22.0 | 36.8 | 28.6 | 11.3 | 0 | 1.3 | 100.0 |

| Antipsychotic medication | ||||||||

| Any medication | 318 | 9.1 | 22.0 | 18.2 | 26.1 | 11.6 | 12.9 | 100.0 |

| Oral medication | 318 | 12.6 | 26.4 | 23.3 | 22.6 | 6.9 | 8.2 | 100.0 |

| Injectibles | 318 | 72.6 | 11.6 | 6.9 | 7.9 | 0.9 | 0 | 100.0 |

| Both oral and injections | 318 | 75.2 | 11.0 | 7.5 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 100.0 |

Table 4.

Comparative Course Characteristics of Patients with Schizophrenia in Current Study (Butajira) and That of DOSMD

| Course Characteristics (Categories) | % Patients in Course Categories |

||

| Butajira | DOSMD—Developing Countries | DOSMD—Developed Countries | |

| Continuous illness with psychotic episodes or residual symptoms | 30.8 | 35.7 | 60.9 |

| Psychotic (≤5% of follow-up) | 36.8 | 18.4 | 18.7 |

| Psychotic (>75% of follow-up) | 1.3 | 15.9 | 20.2 |

| Complete remission (>75% of follow-up) | 5.7 | 38.3 | 22.3 |

| On antipsychotic (>75% of follow-up) | 12.9 | 15.9 | 60.8 |

| Never on antipsychotics | 9.1 | 5.9 | 2.5 |

DOSMD, Determinants of Outcome in Severe Mental Disorders.

Of those who completed fourth and fifth year of follow-up, the respective percentage of cases with continuous illness was 27.4% (31/113) and 36.5% (19/52). Cross-sectionally, of all patients having a clinical assessment at the third year of follow-up (n = 215), most (54%) were in a psychotic episode, while 27.4% were in complete remission and 17.6% in partial remission for at least the month preceding the third-year assessment. Although most patients who dropped out of study through death and refusal had a poorer outcome, the contribution of this subgroup to the overall symptomatic outcome of the cohort was very low (data not shown).

The majority (90%) of the cases received antipsychotic medications at least once during follow-up and, of these, 30% had received medications for at least 50% of the follow-up period. However, only 12.9% had antipsychotic medication for over 75% of follow-up period. Over a quarter (27.3%) had taken injectible medications, primarily fluphenazine decanoate depot at least once during follow-up.

Correlates of Remission

Household size, age of onset, and treatment with antipsychotic medication were independently associated with being in remission for at least 50% of the follow-up time (table 5). The highest effect, albeit with a wide confidence interval (CI), was associated with later age of onset of illness. Onset of illness after age 30 was associated with a nearly 6-fold odds of achieving remission for 50% or longer of the follow-up duration (odds ratio [OR] = 5.95, 95% CI = 1.14–31.10, P = 0.04). Those living in a household with 3 or more adults were 3 times more likely to be in complete remission for more than 50% of the follow-up time (OR = 3.00, 95% CI = 1.06–8.46, P = 0.04). Those who took antipsychotic medication for at least 50% of the follow-up period were also more likely to be in complete remission (OR = 5.0, 95% CI = 1.75–4.25; P < 0.01). Previous history of treatment at baseline (both with antipsychotics medications and receipt of treatment from informal sectors) did not predict either treatment or remission during follow-up (data not shown).

Table 5.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Factors Associated With Complete Remission Among Cases With Schizophrenia in Butajira, Ethiopia

| Characteristics (N)a | Cases (%) | Crude Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)b | P Value |

| Sex (n = 318) | ||||

| Male | 40 (15.2) | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 7 (12.7) | 0.81 (0.34–1.92) | ||

| Age (n = 318), y | ||||

| 15–24 | 12 (17.6) | 1.00 | ||

| 25–34 | 22 (15.5) | 0.86 (0.40–1.85) | ||

| 35–49 | 13 (12.0) | 0.64 (0.27–1.50) | ||

| Marital status (n = 318) | ||||

| Single | 22 (13.1) | 1.00 | ||

| Married | 18 (19.8) | 1.64 (0.83–3.24) | ||

| Other | 7 (11.9) | 0.90 (0.36–2.21) | ||

| Education (n = 273) | ||||

| No formal education | 13 (10.4) | 1.00 | ||

| Elementary education | 15 (16.5) | 1.70 (0.77–3.78) | ||

| Secondary and above | 8 (14.0) | 1.41 (0.55–3.61) | ||

| Residence (n = 308) | ||||

| Urban/semiurban | 9 (12.0) | 1.00 | ||

| Rural | 38 (16.3) | 1.43 (0.66–3.11) | ||

| Household size (n = 318) | ||||

| Less than 3 persons | 22 (15.0) | 1.00 | 1.0 | |

| 3 or above | 25 (14.6) | 0.97 (0.52–1.81) | 3.00 (1.06–8.46) | 0.04 |

| Religion (n = 300) | ||||

| Muslim | 30 (13.0) | 1.00 | ||

| Christian | 13 (18.8) | 1.55 (0.76–3.18) | ||

| On antipsychotics (n = 318) | ||||

| 50% of follow-up time or more | 23 (32.9) | 4.57 (2.40–8.77) | 5.0 (1.75–14.25) | <0.01 |

| Other | 24 (9.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Type of onset (n = 232) | ||||

| Acute | 21 (13.5) | 1.00 | ||

| Insidious | 13 (17.1) | 1.34 (0.63–2.82) | ||

| Duration of illness (n = 313), y | ||||

| 2 or less | 14 (17.5) | 1.00 | ||

| More than 2 | 32 (13.7) | 0.75 (0.38–1.50) | ||

| Age of onseta (n = 295), y | ||||

| 19 or less | 8 (9.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 20–29 | 29 (19.0) | 2.31 (1.01–5.31) | 5.58 (1.34–23.20) | 0.02 |

| 30 or more | 8 (14.5) | 1.68 (0.60–4.78) | 5.95 (1.14–31.10) | 0.04 |

| Clinical subtypes (n = 318) | ||||

| Paranoid | 20 (18.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Hebephrenic | 5 (29.4) | 1.83 (0.58–5.80) | 2.58 (0.21–31.26) | 0.46 |

| Catatonic | 5 (29.4) | 1.22 (0.41–3.68) | 4.13 (0.83–20.43) | 0.08 |

| Undifferentiated | 10 (8.4) | 0.40 (0.18–0.91) | 0.47 (0.15–1.52) | 0.21 |

| Residual | 7 (15.9) | 0.83 (0.32–2.14) | 0.19 (0.02–1.70) | 0.14 |

| Other | 0 | — | ||

| Total | 47 (14.8) |

Total number in some categories is less than 318 because of missing values.

Stepwise logistic regression with backward selection method with factors retained in the model.

Discussion

This study is the only community-based study on the outcome of schizophrenia in Africa and one of the very few worldwide focusing on a predominantly rural community sample and treatment-naive majority. The study contributes to the existing knowledge on the outcome of schizophrenia because of methodological elements unique to this study. First, the study was genuinely epidemiological with complete ascertainment of all cases with schizophrenia from a predominantly rural district in a house-to-house survey. The majority of cases identified (about 90%) had no contact with mental health services. Secondly, all patients in the cohort were confirmed cases of schizophrenia on measurement-based assessment and independent clinical review by 2 psychiatrists. Thirdly, we used assertive prospective follow-up with monthly assessments, instead of the annual (or longer interval) assessment methods used in other studies. Such frequent assessments are better suited for measuring outcome in an illness like schizophrenia that tends to be both episodic and chronic.23 Fourthly, we carefully accounted for all patients who had died and lost from follow-up for other reasons. Finally, we used similar analytical methods to the WHO studies for comparability.

Treatment and Clinical Outcome

We assessed 3 related clinical outcomes with respect to duration of treatment: proportion of follow-up time spent in full remission or partial remission and proportion of time spent in psychotic episode. Although in some respects our findings are similar to what has been reported elsewhere in developing countries, some of the findings indicate a poorer clinical outcome in this rural setting.

The intermittent nature of the course of illness in nearly 70% of patients, absence of relapse in about a fifth of cases (22%), the low rate experiencing continuous psychotic episodes, and the pattern of medication use are similar to what has been reported in the DOSMD3 and other developing country studies.24 However, the overall course of illness is worse in 2 important respects. First, the proportion attaining full remission for over 75% of the follow-up period in our sample (5.7%) is smaller than that found in the developing country samples where at least 10% of cases were in this category. This is particularly highest for cases from Nigeria (73.1%). Second, and related to the first point, is that a large proportion of cases (30.8%) had persistent symptom of illness, which may partly explain our previous finding of a worse functional outcome in this setting.25 The proportion with continuous illness for those who completed the 3 years follow-up is also high. Delay in initiation of treatment, side effect burden in those who take medication, predominance of chronic cases, and a high proportion of men in the sample might have contributed to the tendency for this poorer clinical outcome.

Although most of those leaving the study were more severely ill, their contribution to the overall follow-up duration and symptomatic outcome is negligible. As shown in table 2, more than 86% of the person-time of follow-up is contributed by those who remained in follow-up. Therefore, the propensity for a worse clinical outcome is primarily due to the course of illness amongst those who remained in the study rather than due to those leaving. Nevertheless, it can be legitimately proposed that had those who dropped out of the study remained in the follow-up for longer, the symptomatic course of illness could have been even worse. Lack of adequate accounting of attritions is one of the main criticisms of studies from developing countries.11 Thus, not withstanding our attempt to account for the impact of attrition, the trajectory of the antecedents of attrition is likely to be significant but difficult to account fully.

Correlates of Outcome

Three factors, 1 sociodemographic and 2 clinical (household size, age of onset, and use of antipsychotic medications), were associated with longer period in complete remission. The association of living in a household with 3 or more adults and remission may be due to improved social network and support.26,27 Although the effect of larger household size may be partly due to improved use of medication, further analysis of data indicated that its effect was not mediated through treatment in our sample. This is somewhat consistent with the observation that having extended families in developing countries may not necessarily enhance chances of accessing care.28 Other studies should replicate this finding and explore the role of household size in mediating better outcome in conjunction with other social factors such as expressed emotion.

The association of a relatively older age at onset of illness with remission is consistent with findings from previous studies.3,24 Taking antipsychotic treatment for more than 50% of the time was also shown to be associated with complete remission even though most of the cases were chronically ill. This emphasizes the benefit of medication at any stage of illness.29,30 Moreover, the outcome of schizophrenia tends to be poorer without treatment.31,33 In general, other relevant factors associated with outcome of schizophrenia have included duration of illness, presence of negative symptoms, and the nature of onset of illness (acute vs chronic).24,34 These factors were not associated with outcome of schizophrenia in our setting. This might be due to the small sample size in the subgroups. Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) has also been associated with poor outcome.34,35 We were unable to determine the effect of DUP on outcome in our study because of the small number of cases who received treatment at time of recruitment. Nevertheless, in our cohort, duration of illness may be equated with DUP for the same reason. If the latter is the case, DUP was not associated with outcome in this setting.

Gender and Follow-up

It is now recognized that the prevalence of schizophrenia may be higher among men than women36 but not to the extent found in our setting (a nearly 5-fold rate among men).8 The reason behind this high gender differential in the prevalence of schizophrenia in this setting is unclear. In this follow-up study, we explored whether differential attrition through death or other reasons might partly explain the lower prevalence of schizophrenia among women in this setting. Our finding of a lower attrition rate among women, at least as reflected during follow-up, suggests that differential attrition may not explain the differential prevalence of schizophrenia between men and women. A recent descriptive analysis of admissions to the national inpatient unit in Ethiopia has also shown a significant gender differential in schizophrenia admissions.37 Discussion of other potential reasons for the gender differential is beyond the scope of this report.

Limitations

Limitations of the study relate to the nature of the sample and setting. The sample was composed of a mixture of chronic and recent onset cases, and this may lead to a more heterogeneous outcome. However, almost all cases were first contact. The predominance of men with a large proportion of untreated sample and a relatively short follow-up duration might also favor a worse outcome. Although physical health was assessed at recruitment of cohort, its association with course of illness was not determined. The variable duration of follow-up may also be another limitation. However, the data analysis allowed the use of all available information.

Conclusions

We draw 3 main conclusions from this study. First, although the overall pattern of outcome of schizophrenia in this setting is comparable to that reported in developing countries, there is a clear tendency toward a poorer outcome in this community-based study. This is likely to reflect the outcome in many sub-Saharan African countries38 where most patients live in the community with limited access to care. Second, treatment with psychotropic medication is a crucial external factor that modifies the outcome of severe mental disorders.14,25 Provision of adequate treatment and enhancement of adherence should receive priority. Third, based on the follow-up data, prerecruitment differential attrition may not explain the differential gender rate found in this setting.

Funding

Stanley Medical Research Institute (98–991).

Acknowledgments

Dr Charlotte Hanlon is highly acknowledged for reviewing the earlier manuscript.

References

- 1.Dube K, Kumar N, Dube S. Longterm course and outcome of Agra cases in the International Pilot study of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1984;70:170–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1984.tb01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–517. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, et al. Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence, and course in different cultures. A World Health Organization ten-country study. Psychol Med Monogr Suppl. 1992;20:1–97. doi: 10.1017/s0264180100000904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sartorius N, Gulbinat W, Harrison G, Laska E, Siegel C. Long-term follow-up of schizophrenia in 16 countries. A description of the International Study of Schizophrenia conducted by the World Health Organization. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1996;31:249–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00787917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sartorius N, Jablensky A, Shapiro L. Two-year follow-up of the patients included in the WHO International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 1977;7:529–541. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700004517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig TJ, Siegel C, Hopper K, et al. Outcome in schizophrenia and related disorders compared between developing and developed countries. A recursive partitioning re-analysis of the WHO DOSMD data. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:229–233. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopper K, Harrison G, Janca A, Sartorius N. Recovery from Schizophrenia: An International Perspective—Results from the WHO-Coordinated International Study of Schizophrenia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kebede D, Alem A, Shibre T, et al. Onset and clinical course of schizophrenia in Butajira-Ethiopia—a community-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:625–631. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0678-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurihara T, Kato M, Reverger R, Yagi G. Clinical outcome of patients with schizophrenia without maintenance treatment in a non-industrialised society. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:515–524. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopper K, Wanderling J. Revisiting the developed versus developing country distinction in course and outcome in schizophrenia: results from ISoS, the WHO collaborative follow-up project. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:835–846. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen A, Patel V, Thara R, Gureje O. Questioning an axiom: better prognosis for schizophrenia in the developing world? Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:229–244. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel V, Cohen A, Thara R, Gureje O. Is the outcome of schizophrenia really better in developing countries? Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28:149–152. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462006000200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bromet EJ. Cross-national comparison: problems in interpretation when studies are based on prevalent cases. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:256–257. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fekadu A, Kebede D, Alem A, et al. Clinical outcome in bipolar disorder in a community-based follow-up study in Butajira, Ethiopia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114:426–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Office of Population and Housing Census Commission (OPHCC) The 1994 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia. Results for Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples' Region. Volume 1: Part V. Abridged Statistical Report: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Central Statistical Authority. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), Core Version, 2.1. Geneva: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shibre T, Kebede D, Alem A, et al. An evaluation of two screening methods to identify cases with schizophrenia and affective disorders in a community survey in rural Ethiopia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2002;48:200–208. doi: 10.1177/002076402128783244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry, Version 2.1 (SCAN 2.1) Geneva: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byass P, Berhane Y, Emmelin A, et al. The role of demographic surveillance systems (DSS) in assessing the health of communities: an example from Ethiopia. Public Health. 2002;116:145–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rashid E, Kebede D, Alem A. Evaluation of an Amharic version of the CIDI and prevalence estimation of DSM-III-R disorders in Addis Ababa. Ethiop J Health Dev. 1996;10:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alem A, Kebede D, Shibre T, Negash A, Deyassa N. Comparison of computer assisted scan diagnoses and clinical diagnoses of major mental disorders in Butajira, rural Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2004;42:137–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eaton W, Thara R, Federman E, Tien A. Remission and relapse in schizophrenia: the Madras Longitudinal Study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:357–363. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199806000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menezes P, Rodrigues L, Mann A. Predictors of clinical and social outcomes after hospitalization in schizophrenia. Euro Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;247:137–145. doi: 10.1007/BF03033067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kebede D, Alem A, Shibre T, et al. Short-term symptomatic and functional outcomes of schizophrenia in Butajira, Ethiopia. Schizophr Res. 2005;78:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harvey CA, Jeffreys SE, McNaught AS, Blizard RA, King MB. The Camden Schizophrenia Surveys. III: five-year outcome of a sample of individuals from a prevalence survey and the importance of social relationships. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2007;53:340–356. doi: 10.1177/0020764006074529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salokangas RKR. Living situation, social network and outcome in schizophrenia: a five-year prospective follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;96:459–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srinivasan TN, Thara R. How do men with schizophrenia fare at work? A follow-up study from India. Schizophr Res. 1997;25:149–154. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(97)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips M, Zhao Z, Xiong X, Cheng X, Sun G, Wu N. Changes in the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenic in-patients in China. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:226–231. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wunderink A, Nienhuis F, Systema S, Wiersma D. Treatment delay and response rate in first episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;113:332–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murthy RS, Kishore KV, Chisholm D, Thomas T, Sekar K, Chandrashekari CR. Community outreach for untreated schizophrenia in rural India: a follow-up study of symptoms, disability, family burden and costs. Psychol Med. 2005;35:341–351. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ran M, Xiang M, Huang M, Shan Y, Cooper J. Natural course of schizophrenia: 2-year follow-up study in a rural Chinese community. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:154–158. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurihara T, Kato M, Reverger R, Kashima H. Never-treated patients with schizophrenia in the developing country of Bali. Schizophr Res. 2005;79:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arndt S, Andreasen N, Flaum M, Miller D, Nopoulos P. A longitidinal study of symptom dimensions in schizophrenia. Prediction and symptoms of patterns of change. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:352–360. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950170026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Haan L, Linszen DH, Lenior ME, de Win ED, Gorsira R. Duration of untreated psychosis and outcome of schizophrenia: delay in intensive psychosocial treatment versus delay in treatment with antipsychotic medication. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:341–348. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saha S, chant D, Welham J, McGrath J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fekadu A, Desta M, Alem A, Prince M. A descriptive analysis of admissions to Amanuel Psychiatric Hospital in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2007;21:173–178. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gureje O. Thirteen-year social outcome among Nigerian outpatients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:147–151. doi: 10.1007/s001270050126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]