Abstract

Burkholderia pseudomallei is the causative agent of melioidosis, which is considered a potential deliberate release agent. The objective of this study was to establish and characterise a relevant, acute respiratory Burkholderia pseudomallei infection in BALB/c mice. Mice were infected with 100 B. pseudomallei strain BRI bacteria by the aerosol route (approximately 20 median lethal doses). Bacterial counts within lung, liver, spleen, brain, kidney and blood over 5 days were determined and histopathological and immunocytochemical profiles were assessed. Bacterial numbers in the lungs reached approximately 108 cfu/ml at day 5 post-infection. Bacterial numbers in other tissues were lower, reaching between 103 and 105 cfu/ml at day 4. Blood counts remained relatively constant at approximately 1.0 × 102 cfu/ml. Foci of acute inflammation and necrosis were seen within lungs, liver and spleen. These results suggest that the BALB/c mouse is highly susceptible to B. pseudomallei by the aerosol route and represents a relevant model system of acute human melioidosis.

Keywords: aerosol, Burkholderia pseudomallei, murine

Burkholderia pseudomallei, the aetiological agent of melioidosis, is widely distributed throughout the tropical countries of the world, where it exists as a free-living bacterium in soil and water (Pitt 1990).

Melioidosis in humans has a wide clinical presentation. Acute disease includes pneumonia and septicaemia, may be rapidly progressive and has a high mortality rate. Subacute and chronic forms of melioidosis also exist and re-activation following sometimes lengthy latent periods is common. Natural infection in humans occurs either via contamination of skin abrasions or by the inhalation of aerosols containing the bacterium (Leelarasamee & Bovornkitti 1989). B. pseudomallei is also considered a candidate organism for use in biological warfare or for deliberate release, most likely as an aerosol and respiratory disease would probably predominate.

Current recommended treatment for acute melioidosis is high-dose intravenous ceftazidime, or a carbapenem, for at least 10–14 days, followed by prolonged oral eradication therapy (Chaowagul 2000; Dance 2002; Health Protection Agency, 2003; Cheng et al. 2004). To date, no licensed vaccine for human use exists, although several candidates have been studied.

Acute and chronic models of B. pseudomallei infection in mice have been described previously (Veljanov et al. 1996; Leakey et al. 1998; Hoppe et al. 1999; Santanirand et al. 1999; Gauthier et al. 2001; Liu et al. 2002; Jeddeloh et al. 2003) and with one exception (Jeddeloh et al. 2003), these studies delivered organisms via either the intraperitoneal, intravenous or intranasal routes of infection. The clinical manifestations of disease have been shown, in part, to be dependent on the route of infection (Liu et al. 2002) and although any organ system may be involved during human B. pseudomallei infection, the lungs, liver and spleen are the primary targets of pathological involvement (Piggot & Hochholzer 1970; Wong et al. 1995; White 2003).

The aim of this study therefore, was to establish and further characterize an acute aerosol-challenge model of respiratory B. pseudomallei infection in the mouse. Such a model is needed for studies of pathogenesis of B. pseudomallei and for evaluation of antimicrobials and vaccine candidates.

Materials and methods

Bacteria

Burkholderia pseudomallei strain BRI is a clinical isolate recovered from a fatal case of melioidosis imported into the UK (originally a gift from P. Maynard at Blackburn Royal Infirmary, UK, Kenny et al. 1999). Stocks of B. pseudomallei were prepared by the inoculation of a single colony grown overnight on nutrient agar plates (BioMerieux, Basingstoke, UK) into 100 ml of nutrient broth. Broths were incubated at 37 °C on a rotary shaker for 24 h. Aliquots (0.5 ml) of the bacterial suspension were frozen at −80 °C using Protect beads according to manufacturer's instructions. B. pseudomallei was recovered subsequently by adding five Protect beads into 100 ml of nutrient broth, and incubation on a rotary shaker for 24 h at 37 °C.

Infection of animals

All animal studies were carried out in accordance with the UK Scientific Procedures Act (Animals) 1986 and the Codes of Practice for the Housing and Care of Animals Used in Scientific Procedures, 1989.

A Collison nebulizer containing 20 ml of B. pseudomallei at a concentration of 1.14 × 108 cfu/ml (1/50 dilution of an undiluted overnight broth suspension) and three drops of antifoam 289 (Sigma Chemical Co., Poole, UK) was used to generate aerosol particles. The particle size of the aerosol produced in this manner is between 1 and 3 μm in range (determined by an Anderson sampler). Control experiments have shown that antifoam is not detrimental to either the bacterial culture or the animals (data not shown). The aerosol was conditioned in a modified Henderson apparatus (Druett 1969). Barrier-reared, female, 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, UK) were placed in a nose-only exposure chamber and exposed for 10 min to a dynamic aerosol. The aerosol stream was maintained at 50–55% relative humidity and 22 ± 3 °C. The concentration of B. pseudomallei in the air stream was determined by taking samples from the exposure chamber using an All Glass Impinger (AGI 30), (May & Harper 1957) operating at 11.5 l/min, containing 10 ml sterile PBS and antifoam. Impinger samples were plated onto nutrient agar and incubated, in air at 37 °C, before counting.

Challenged mice were removed from the exposure chamber and returned to their home cages within an ACDP (U.K. Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens) animal containment level 3 facility. Animals were closely observed over a 5-day period for the development of symptoms, and where appropriate, time to death was recorded. Malaise was noted in some animals, as was immobility and ruffled coat. Humane endpoints were strictly observed (immobility, dyspnoea, paralysis) so that no animal became distressed. ‘Time to death’ figures included those animals killed by cervical dislocation, according to the humane endpoint.

Median lethal dose determination

Five separate groups each containing five mice (25 animals in total) were infected by the aerosol route with a five logarithmic dilution series of B. pseudomallei as described above and deaths were recorded over 5 days. The median lethal dose (MLD) by the aerosol route was calculated (Reed & Muench 1938) based on the number of retained organisms in the lungs of those animals that received the 1/50 dilution of the overnight bacterial suspension (the highest concentration of bacterial suspension). It was assumed that the number of retained organisms in the lungs of mice reduced by one logarithm in line with each logarithmic dilution of the spray suspension used in the dilution series (these figures were confirmed by impinger counts).

Pathogenesis study

In a separate experiment, 65 mice in total were randomized and allocated into four separate groups for aerosol challenge (the aerosol exposure equipment holds a maximum of 20 animals per run). One group contained 20 animals, and the remaining three groups contained 15 animals each. All four groups were challenged by the aerosol route with B. pseudomallei strain BRI. Each group was challenged with aliquots of the same bacterial suspension, and impinger counts from each run were plated out to confirm the calculated dose that mice from each run received.

The Collison nebulizer contained B. pseudomallei at a concentration of 1.14 × 108 cfu/ml (1/50 dilution of an undiluted overnight broth suspension) and the calculated retained dose for mice after each of the four runs was 66, 103, 87 and 178 cfu. This was calculated by applying the formula:

where a is the impinger count (cfu/ml), b the impinger volume (ml), c the minute volume of animal (ml/min), d the exposure time (min), e the impinger flow rate (l/min) and f the impinger sample time (min).

It was assumed that the minute volume of a mouse was 20 ml/min (Guyton 1947). The above formula gave the estimated dose each animal was exposed to but not necessarily retained and it was assumed that each mouse retained 40% of the organisms breathed-in (Harper & Morton 1962).

This dose was decided as this was approximately 20 MLD values and represents a realistic challenge dose for subsequent studies of vaccine efficacy and antimicrobial studies.

At eleven separate time-points after infection, animals (five per time point, including T = 0) were killed following aerosol exposure, as described above, and the numbers of viable bacteria present in blood and various organs were determined. Organs were removed at each time point from surviving animals, however, at the 5-day post-infection time point, only one animal remained alive for sampling. Organs were aseptically removed and homogenized in 2 ml of nutrient broth in a tissue homogenizer (Medicon, Tuttlingen, Germany). Bacteria were enumerated after plating 0.25 ml of tissue homogenate (1:10 serial dilutions in nutrient broth) onto nutrient agar in duplicate and incubating for 48 h at 37 °C in air. For enumeration of bacteria in blood, an undiluted 0.1 ml sample was plated out, in duplicate, and the number of viable bacteria was determined as described above. Counts obtained were expressed as colony forming units (cfu) per ml of homogenized tissue or blood.

Histopathological studies

Starting from 24 h post-infection, lung, liver, spleen, kidney and brain were taken for histology from one animal per time point (eleven time points in total). Tissues were fixed in 4% formal buffered saline and processed for paraffin wax embedding using standard techniques. Thin sections (5 μm) were cut and stained with haematoxylin and eosin for histopathological analysis. Selected sections were also stained by Giemsa method for the identification of bacterial cells.

Immunohistochemical studies

Immunohistochemical procedures were performed on sections (5 μm) cut from paraffin-embedded tissues, mounted on ‘snowcoat’ X-tra™ micro slides (Surgipath, Peterborough, UK), de-waxed in xylene and rehydrated through decreasing concentrations of industrial methylated spirit (99%) to distilled water. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using the Dako Ark immunohistochemical staining kit (Animal Research Kit) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dako Ltd. Ely, Cambs., UK) with the following modifications; enzyme predigestion using Proteinase K for 5 min and Protein block (serum free) for 5 min. This kit was designed to eliminate endogenous immunoglobulin background staining. The primary antibody was a murine monoclonal antibody specific for exopolysaccharide antigen from B. pseudomallei. A murine monoclonal antibody specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was used as a primary antibody in negative control slides and sections of non-infected mouse lung, liver and spleen served as negative control tissues. Positive control material was taken from BALB/c mice 3 days post-aerosol infection with B. pseudomallei.

Results

MLD by the aerosol route

The MLD for B. pseudomallei strain BRI in BALB/c mice by the aerosol route of infection was 5 cfu.

Pathogenesis study

Impinger counts from each of the four aerosol challenge runs indicated that all mice had received a calculated dose of approximately 100 cfu (20 MLD) and therefore a significant challenge dose for pathogenesis studies. In the pathogenesis study, there was 100% mortality caused by B. pseudomallei infection between 2 and 5 days post-infection (excluding those animals taken for time points samples).

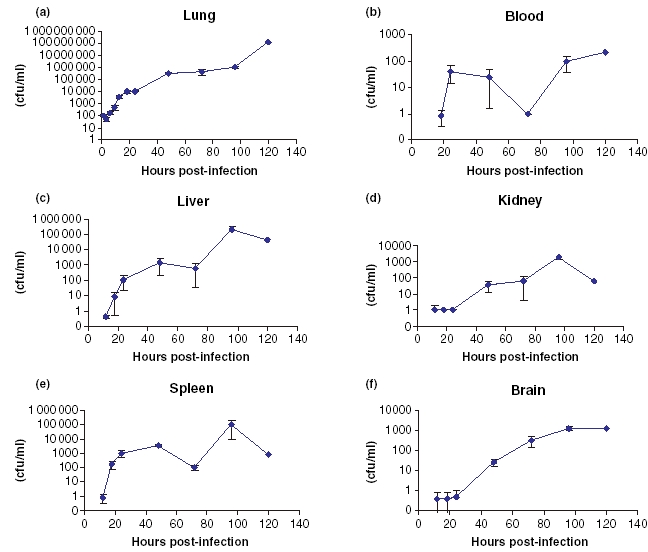

Colony counts per millilitre (cfu/ml) of homogenized tissue (n = 5) over the 5 days following challenge are shown in (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a–f) Bacterial counts (cfu/ml) of Burkholderia pseudomallei BRI in various organs following aerosol infection in Balb/c mice. (a) Lung, (b) Blood, (c) Liver, (d) Kidney, (e) Spleen and (f) Brain. Data points represent mean values (n = 5), except 120 h postinfection, which represents data from one surviving animal only. Data points where no cfu were detected are not plotted. Error bars are ± standard deviation.

Lungs contained 100 cfu/ml at 1 h post-infection, which had reduced to half that number by 3 h post-infection. Between 3 and 24 h post-infection, an exponential increase to approximately 104 bacterial cfu/ml was detected in the lungs. Between 24 h and 4 days post-infection, the number of bacteria in the lungs increased to approximately 1 × 106 cfu/ml. By 5 days post-infection, approximately 1 × 108 cfu/ml were present in the lungs of the remaining mouse.

Between 18 and 24 h post-infection, viable bacteria were recoverable from the peripheral blood, liver and spleen. Numbers of bacteria in both liver and spleen increased rapidly between 24 and 48 h post-infection to plateau at approximately 1000 cfu/ml. Although at 72 h postinfection, bacterial counts in the spleen and liver appeared to have fallen, by day 4 postinfection, the numbers of viable bacteria recovered from these sites had increased to a peak of approximately 1 × 105 cfu/ml. Peripheral blood bacterial counts declined between 48 and 72 h to approximately 1 cfu/ml, but rose rapidly over the next 48 h to around 100 cfu/ml. In the kidney and brain, bacterial numbers increased gradually over the course of the experiment, to peak at approximately 500 cfu/ml at 4 days post-infection.

Histopathological analysis of B. pseudomallei-infected tissues

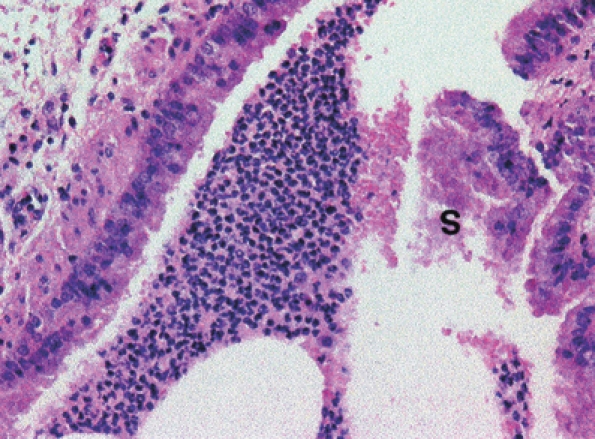

In lungs, a focal, acute exudative bronchitis was noted at 24 h post-infection (Figure 2); the exudate contained numerous neutrophils and smaller numbers of sloughed epithelial cells. Foci of acute alveolitis were seen that comprised focal thickening of alveolar walls by neutrophils (Figure 3). Larger foci of consolidation were observed in which alveolar walls and spaces were infiltrated with neutrophils and macrophages, some of which were necrotic (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Bronchus in the lung of a mouse killed 24 h postexposure to an aerosol of Burkholderia pseudomallei. An exudate containing polymorphonuclear leucocytes, erythrocytes and sloughed cells (S) is present in the lumen. H&E, ×200 magnification.

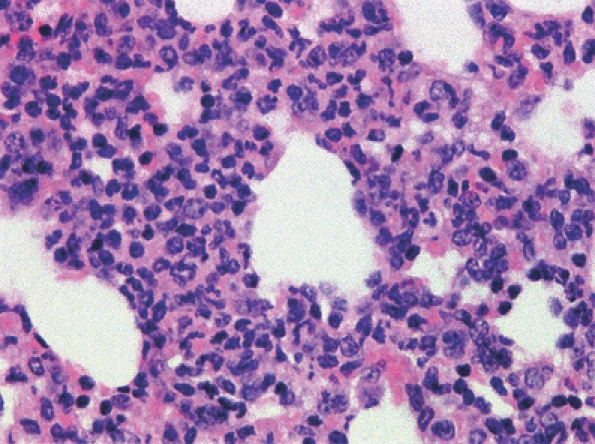

Figure 3.

A focus of acute alveolitis in the lung of a mouse killed 24 h after exposure to an aerosol of Burkholderia pseudomallei. The alveolar walls are infiltrated by neutrophils. H&E, ×400 magnification.

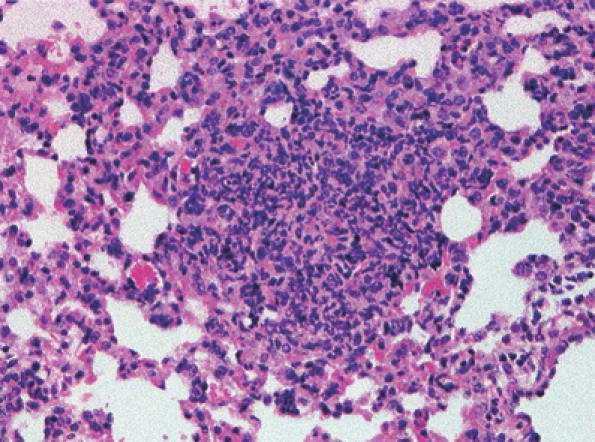

Figure 4.

A focus of acute necrotizing alveolitis and pneumonia in the lung of a mouse killed 24 h after exposure to an aerosol of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Alveolar spaces and walls are infiltrated by neutrophils, some of which are necrotic. H&E, ×200 magnification.

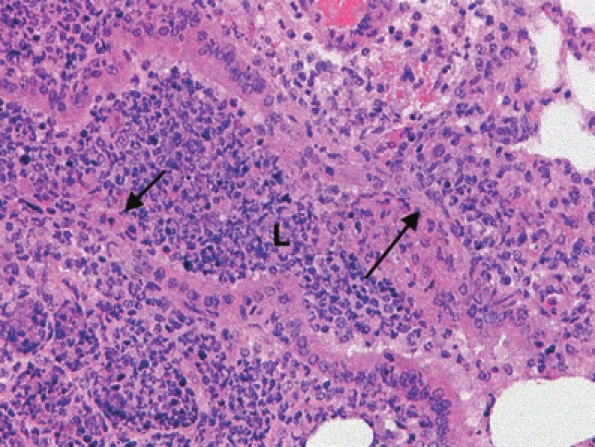

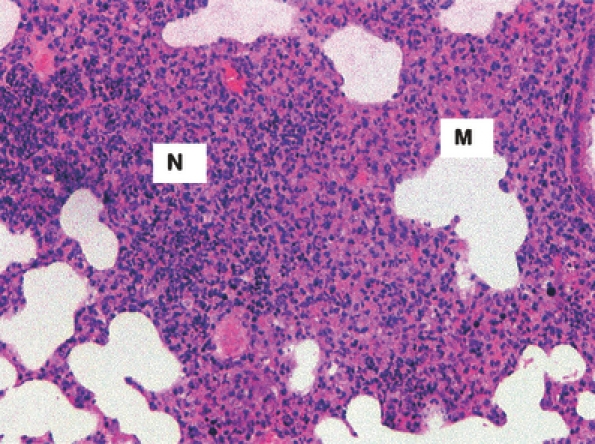

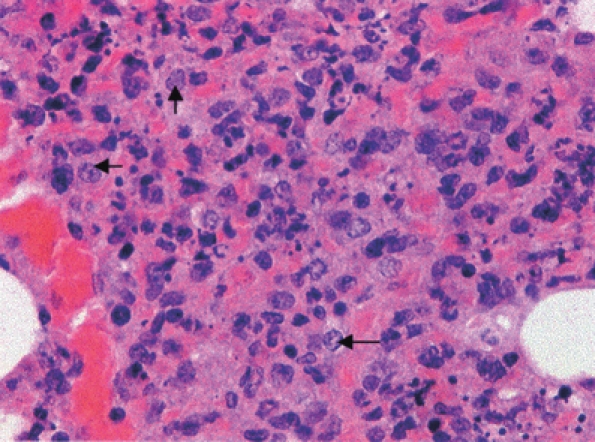

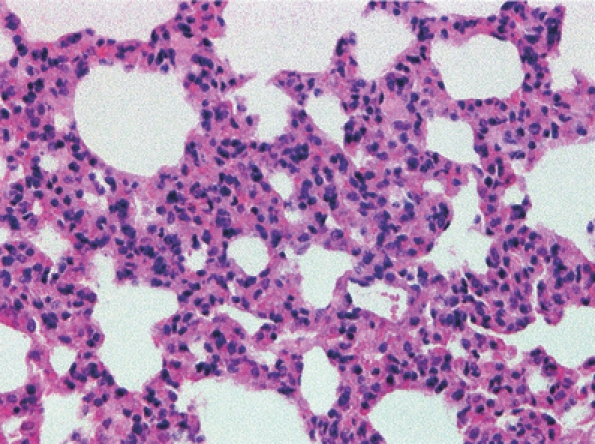

Similar lesions were seen in bronchi (Figure 5) and alveoli (Figure 6) at 48 h post-infection. Macrophages predominated in some lesions (Figure 7) and a patchy generalized thickening of alveolar walls by swollen macrophages was observed (Figure 8).

Figure 5.

Acute exudative bronchiolitis in the lung of a mouse killed 48 h postaerosol exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei. The bronchiole lumen (L) has signs of necrosis and loss of its epithelium (arrows). H&E, ×200 magnification.

Figure 6.

An area of pneumonic consolidation in the lungs of a mouse killed 48 h post-aerosol exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei. In some areas, the inflammatory cells are neutrophils (N) and many are necrotic. In other areas, macrophages (M) predominate. H&E, ×100 magnification.

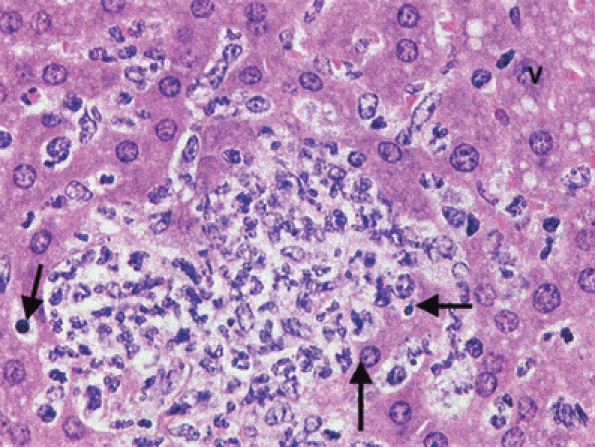

Figure 7.

Acute necrotizing alveolitis and pneumonia in a mouse killed 48 h post-aerosol exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei. Alveolar spaces are infiltrated by macrophages (arrows) predominately and by neutrophils to a lesser extent. Necrotic cells are present. H&E, ×400 magnification.

Figure 8.

Alveolar walls thickened by swollen macrophages in the lungs of a mouse killed 48 h post-aerosol exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei. H&E, ×200 magnification.

Focal, acute, necrotizing bronchopneumonia and alveolitis were seen at 72 and 96 h post-infection and not infrequently these foci of acute necrotizing inflammation were noted adjacent to an artery, bronchus or bronchiole (Figure 9).

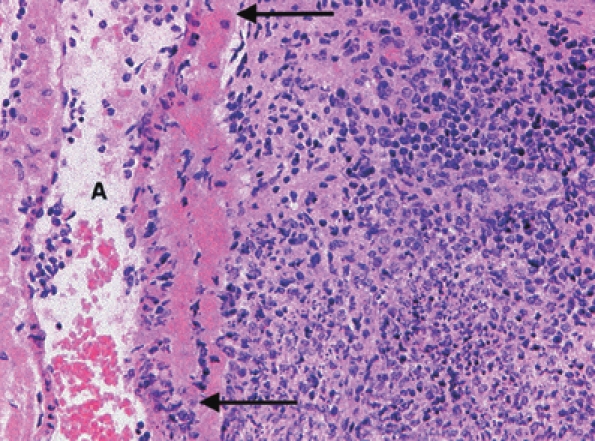

Figure 9.

An area of pneumonic consolidation adjacent to an artery (A) in the lungs of a mouse killed 96 h post-aerosol exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei. Neutrophils, lymphocytes and macrophages are present and a focus of necrosis is present. The artery wall is necrotic between the arrows. H&E, ×200 magnification.

Hepatic lesions were not detected at 24 h post-infection. A mild diffuse vacuolation of hepatocytes, probably intracellular lipid, was noted at 48 h post-infection together with two foci of necrosis infiltrated by neutrophils (Figure 10). These lesions were also present at 72 and 96 h post-infection and small foci of mixed inflammatory cells, frequently containing one or two degenerate hepatocytes were common (Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Focal necrotizing hepatitis in the liver of a mouse killed 48 h post-aerosol exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei. Necrotic hepatocytes (arrows), neutrophil infiltration and generalized cytoplasmic vacuolation (V) of hepatocytes was evident. H&E, ×400 magnification.

Figure 11.

Liver of a mouse killed 96 h post-aerosol exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei. A focal infiltration by mixed inflammatory cells and generalized cytoplasmic vacuolation of hepatocytes was evident. H&E, ×400 magnification.

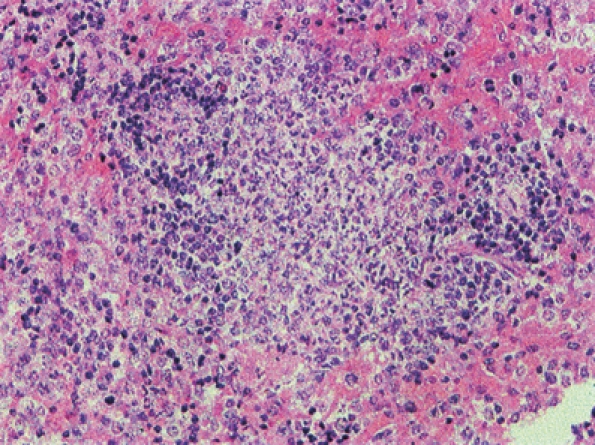

Foci of acute necrotizing splenitis were detected in the red pulp and periarterial lymphoid sheaths at 48 and 72 h post-infection (Figure 12). No abnormalities were detected in brain or kidneys of mice infected with B. pseudomallei and no bacterial cells were detected, by the Giemsa staining method, in lung or liver tissues removed at 4 days postinfection.

Figure 12.

Focal necrotizing splenitis in a mouse killed 48 h post-aerosol exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei. H&E, ×200 magnification.

Immunocytochemical analysis of B. pseudomallei-infected tissues

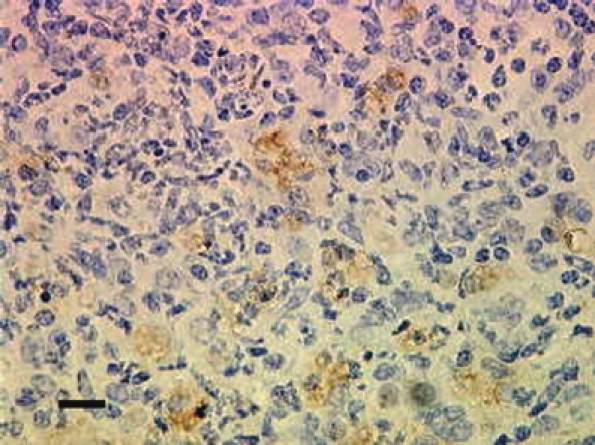

Immunolabelling of paraffin-embedded tissues with the monoclonal antibody, which recognized exopolysaccharide antigen, indicated that B. pseudomallei antigen was only present in lung tissue. No immuno-labelled antigen was detected in liver or spleen tissues at any time throughout the course of the experiment.

Staining in the lung became more intensive and extensive over time as infection progressed. At day 1 post-infection, labelling was moderate, but by days 3 and 4 post-infection, the intensity of the labelling was scored as severe. Antigen was confined to foci of acute necrotizing alveolitis and was located primarily within the cytoplasm of macrophages and neutrophils associated with areas of consolidation (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Section of a lung from a mouse killed 72 h after aerosol exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei. Exopolysaccharide antigen (stained brown) is associated with foci of acute necrotizing alveolitis. Bar, 0.20 mm.

Discussion

The MLD value of 5 cfu found in this study is comparable with the value for B. pseudomallei strain 1026b (10 cfu) delivered in small particle aerosols to BALB/c mice (Jeddeloh et al. 2003). It is also comparable with (or below) the MLD values for other virulent strains of B. pseudomallei delivered by the aerosol route, determined previously in this laboratory (data not shown).

The MLD of strain BRI was 54 cfu by the intraperitoneal route (data not shown). Other workers have reported a wide range of MLD values with different routes of infection, and with various strains of B. pseudomallei [4 cfu (Leakey et al. 1998) to 103 cfu (Hoppe et al. 1999)].

Other microorganisms, such as Legionella pneumophila (Fitzgeorge et al. 1983) and B. mallei (Lever et al. 2003), have also been shown to be more virulent when delivered by the airborne route. This may be related to the anatomy of the lung rather than the bacterial properties. The lung is a vast expanse of epithelial tissue, richly supplied with blood travelling to all areas of the body. The surface area of the epithelial tissue may allow for a rapid uptake of bacterial cells into both the cells and the bloodstream, providing a quicker dissemination of the bacteria. Alternatively, phagocytic cells within the lungs may support the uptake and replication of bacterial cells more efficiently.

The rise detected in bacterial counts to around 100 cfu/ml within peripheral blood after 72 h postinfection is consistent with acute human septicaemic melioidosis, in which 76% of patients are reported to have bacterial blood counts of up to 100 cfu/ml (Walsh et al. 1995).

The bacterial burden throughout the course of this study was the greatest in the lung. This is consistent with other studies where the route of infection was via the aerosol route, (Jeddeloh et al. 2003) and to a lesser extent via the intranasal route of infection (Liu et al. 2002). It suggests rapid bacterial multiplication within the lungs as well as at other sites. In comparison, when B. pseudomallei was delivered by the intraperitoneal or intraveneous routes of infection, lung involvement was minimal (Hoppe et al. 1999; Santanirand et al. 1999; Gauthier et al. 2001) and disease signs were less severe.

Bacterial multiplication within the lung was exponential over the first 24 h postinfection, and organisms once seeded to the spleen and liver underwent a similar phase of initial exponential growth before the rate of replication became more gradual. A similar pattern of replication has been reported previously (Jeddeloh et al. 2003).

Haematogenous spread of bacteria occurred with secondary foci of infection in both the spleen and liver. This is similar to the pattern of disease seen in humans, in whom liver and splenic abscesses are common (White 2003). Bacterial cells were consistently detected in the blood of infected mice throughout the course of infection, as has been reported previously (Leakey et al. 1998; Jeddeloh et al. 2003). In this study, however, numbers of bacterial cells in the blood remained relatively constant, after an initial increase, at approximately 100 cfu/ml. This is in contrast to other studies, which have reported increasing blood bacterial loads (Leakey et al. 1998; Jeddeloh et al. 2003). However, the bacterial loads detected in brain and kidney, in this study, may be a reflection of the numbers of bacteria in the blood rather than secondary foci of infection within these organs; however, bacterial numbers in these organs are above those detected in whole blood for the last three time points. This is consistent with the aerosol infection of BALB/c mice by the closely related organism B. mallei (Lever et al. 2003). However, the pathogenesis of B. mallei in BALB/c mice was significantly different, as bacteraemia was transient and the disease less acute.

In this study, all BALB/c mice exhibited splenomegaly by day 4 postinfection; splenomegaly has often been reported in human cases of melioidosis (Dance 2002).

No abnormalities were detected in brain or kidneys of mice infected with B. pseudomallei, which is consistent with observations on the pathology of human melioidosis where solid-organ pathology occurs mainly in the lungs, liver and spleen (Piggot & Hochholzer 1970; Wong et al. 1995).

The necrotizing nature of many of the lesions seen could be because of the bacterial cells elaborating a toxin(s) capable of inducing cell death. B. pseudomallei is known to produce numerous exotoxins (Nigg et al. 1955; Mohamed et al. 1989; Haase et al. 1997; Haussler et al. 1998) and the acute progression of the disease seen in the aerosol-infected BALB/c mice in this study is consistent with the course of infection observed in humans suffering from acute melioidosis.

The specific staining of antigen within the cytoplasm of macrophages and neutrophils associated with lung consolidation is consistent with the findings of immunohistochemical staining performed on human tissue samples taken from known cases of melioidosis infection (Wong et al., 1996).

Lack of staining in liver and spleen is surprising as numbers present in those organs were similar to numbers seen in lung tissues. This suggests that individual bacterial cells in the liver and spleen may not produce as much capsule as those bacterial cells in lung tissue. Three different phenotypes of B. pseudomallei in vivo have been described previously; one being acapsular, one with a microcapsule and a third with a macrocapsule (Popov et al. 1990, 1992). The macrocapsule variant was shown to persist longer within alveolar macrophages by avoiding phagocytosis and the increased immunostaining observed within the lung tissue in this study may therefore be because of the selection of a capsular variant. A similar immunostaining profile detected during B. mallei infection of BALB/c mice (Lever et al. 2003) may be explained by this selection of capsular variants by B. mallei in vivo.

In summary, a murine model of acute melioidosis, which closely resembles the characteristics of acute melioidosis in humans has been developed, and the pathology described, using a fully virulent human clinical isolate and a relevant route of infection. This is the first time the pathology of respiratory melioidosis in a murine model has been characterized. This model may therefore be suitable for studies of the efficacy of candidate vaccines and therapies against respiratory B. pseudomallei infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Graham Hall for pathological analysis and Georgina Knight for histopathological services.

References

- Chaowagul W. Recent advances in the treatment of severe melioidosis. Acta Trop. 2000;74:133–137. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(99)00062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AC, Fisher DA, Anstey NM, Stephens DP, Jacups SP, Currie BJ. Outcomes of patients with melioidosis treated with meropenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1763–1765. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1763-1765.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dance DAB. Melioidosis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2002;15:127–132. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druett HA. A mobile form of the Henderson apparatus. J. Hyg. (Lond.) 1969;67:437–448. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400041851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgeorge RB, Baskerville A, Broster M, Hambleton P, Dennis PJ. Aerosol infection of animals with strains of Legionella pneumophila of different virulence: comparison of virulence with intraperitoneal and intranasal routes of infection. J. Hyg. (Lond.) 1983;90:81–89. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400063877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier YP, Hagen RM, Brochier GS, et al. Study on the pathophysiology of experimental Burkholderia pseudomallei infection in mice. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2001;30:53–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2001.tb01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyton AC. Measurement of the respiratory volumes of laboratory animals. Am. J. Path. 1947;150:70–77. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1947.150.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase A, Jansen J, Barrett S, Currie B. Toxin production by Burkholderia pseudomallei strains and correlation with severity of melioidosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 1997;46:557–563. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-7-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GJ, Morton JD. A method for measuring the retained dose in experiments on airborne infection. J. Hyg. (Lond) 1962;60:249–257. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400039504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haussler S, Nimtz M, Domke T, Wray V, Steinmetz I. Purification and characterisation of a cytotoxic exolipid of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:1588–1593. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1588-1593.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Protection Agency. Health Protection Agency Interim Guidelines for Action in the Event of a Deliberate Release: Glanders & Melioidosis, version 2.2, 14 August 2003. London: HPA; 2003. [Online] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe I, Brenneke B, Rohde M, et al. Characterisation of a murine model of melioidosis: comparison of different strains of mice. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:2891–2900. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2891-2900.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeddeloh JA, Fritz DL, Waag DM, Hartings JM, Andrews GP. Biodefense-driven murine model of pneumonic melioidosis. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:584–587. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.584-587.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DJ, Russell P, Rogers D, Eley SM, Titball RW. In vitro susceptibilities of Burkholderia mallei in comparison to those of other pathogenic Burkholderia spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2773–2775. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.11.2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leakey AK, Ulett GC, Hirst RG. BALB/c and C57BI/6 mice infected with virulent Burkholderia pseudomallei provide contrasting animal models for the acute and chronic forms of human melioidosis. Microb. Pathog. 1998;24:269–275. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelarasamee A, Bovornkitti S. Melioidosis: review and update. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1989;11:413–425. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever MS, Nelson M, Ireland PI, et al. Experimental aerogenic Burkholderia mallei (glanders) infection in the BALB/c mouse. J. Med. Microbiol. 2003;52:1109–1115. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Ghee CK, Eu HY, Kim LC, Yunn-Hwen G. Model of differential Susceptibility to mucosal Burkholderia pseudomallei infection. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:504–511. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.504-511.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May KR, Harper GJ. The efficiency of various liquid impinger samplers in bacterial aerosols. Br. J. Ind. Med. 1957;14:287–297. doi: 10.1136/oem.14.4.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed R, Nathan S, Embi N, Razak N, Ismail G. Inhibition of macromolecular synthesis in cultured macrophages by Pseudomonas pseudomallei exotoxin. Microbiol. Immunol. 1989;33:811–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1989.tb00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg C, Heckly RJ, Colling M. Toxin produced by Malleomyces pseudomallei. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1955;89:17–20. doi: 10.3181/00379727-89-21700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggot JA, Hochholzer L. Human melioidosis: a histopathologic study of acute and chronic melioidosis. Arch. Pathol. 1970;90:101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt TL. Pseudomonas mallei and P. pseudomallei. In: Parker MT, Duerden BI, editors. Topley and Wilson's Principles of Bacteriology, Virology and Immunity. 8th edn. II. London: Edward Arnold; 1990. pp. 265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Popov SF, Mel’nikov BI, Kurilov VIa, Bozhko VG. The ultrastructural characteristics of the causative agent of melioidosis and its interaction with phagocytes in vivo. Mikrobiol. Zh. 1990;52:18–22. in Russian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popov SF, Kurilov VI, Lagutin MP. The interaction of the causative agent of melioidosis with the host's alveolar macrophages. Mikrobiol. Zh. 1992;54:3–7. in Russian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Santanirand P, Harley VS, Dance DAB, Drasar BS, Bancroft GJ. Obligatory role of gamma interferon for host survival in a murine model of infection with Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:3593–3600. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3593-3600.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veljanov D, Vesselinova A, Nikolova S, Najdenski H, Kussovski V, Markova N. Experimental melioidosis in inbred mouse strains. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 1996;283:351–359. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(96)80071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh AL, Smith MD, Wuthiekanun V, et al. Prognostic significance of quantitative bacteremia in septicemic melioidosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995;21:1498–1500. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.6.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White NJ. Melioidosis. Lancet. 2003;361:1715–1722. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KT, Puthucheary SD, Vadivelu J. The histopathology of human melioidosis. Histopathology. 1995;26:51–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1995.tb00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]