Abstract

Determination of burn severity (i.e. burn depth) is important for effective medical management and treatment. Using a recently described acute burn model, we studied various morphological parameters to detect burn severity. Anaesthetized Sprague–Dawley rats received burns of various severity (0- to14-s contact time) followed by standard resuscitation using intravenous fluids. Biopsies were taken from each site after 5 h, tissues fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, processed and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Superficial burn changes in the epidermis included early keratinocyte swelling progressing to epidermal thinning and nuclear elongation in deeper burns. Subepidermal vesicle formation generally decreased with deeper burns and typically contained grey foamy fluid. Dermal burns were typified by hyalinized collagen and a lack of detectable individual collagen fibres on a background of grey to pale eosinophilic seroproteinaceous fluid. Intact vascular structures were identified principally deep to the burn area in the collagen. Follicle cell injury was identified by cytoplasmic clearing/swelling and nuclear pyknosis, and these follicular changes were often the deepest evidence of burn injury seen for each time point. Histological scores (epidermal changes) or dermal parameter depths (dermal changes) were regressed on burn contact time. Collagen alteration (r2 = 0.91) correlated best to burn severity followed by vascular patency (r2 = 0.82), epidermal changes (r2 = 0.76), subepidermal vesicle formation (r2 = 0.74) and follicular cell injury was useful in all but deep burns. This study confirms key morphological parameters can be an important tool for the detection of burn severity in this acute burn model.

Keywords: burn, collagen, rat, skin, trauma

Initial diagnosis of burn severity is typically based on the regional thickness of affected skin and established medical parameters such as burn depth (Singer et al. 2007a,b). The clinical ability to accurately diagnose burn depth is related to the experience of the clinician and the timing of the diagnosis following injury (Heimbach et al. 1984; DeSanti 2005). Severe burn injury promotes a significant inflammatory response and increases capillary permeability with intravascular volume deficits especially during the first 24 h (Friedl et al. 1989; Mulligan et al. 1994; Kita et al. 2008; Pham et al. 2008). Conventional treatment of major burns involves prompt and aggressive fluid therapy based on the patient weight and extent of burn (Monafo 1996; Pham et al. 2008). In recent years, advances in burn therapy management have significantly decreased morbidity and increased survival of patients (Brigham & McLoughlin 1996;Sheridan 2003; Brigham & Dimick 2008).

A dilemma that remains for the trauma specialist is an accurate and non-invasive method to monitor burn depth (Kim et al. 2001). In the hours to days following a thermal injury, a significant complication known as ‘burn progression’ can cause the zone of necrosis to expand in size (Singer et al. 2007a,b). Defining the dynamics of burn progression has been hindered in part because of the lack of accurate means of burn depth analysis. Dermal biopsy of burn wounds has been investigated as an aid in burn depth detection (Watts et al. 2001), but is considered too invasive for routine use and a less invasive technique would be preferred. The need for novel modalities for burn depth assessment has led to experimental investigation of photoacoustic signalling (Yamazaki et al. 2005), dielectric measurements (Papp et al. 2006), fluorescence imaging (Still et al. 2001), polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography (PS-OCT) (Pierce et al. 2004) and Laser Doppler Imaging (LDI) (Kim et al. 2001; Light et al. 2004) as minimally invasive technique to quantify burn depth.

Our group has recently developed a novel rat model to assess burn progression pathogenesis and develop experimental therapeutics to control it (Kim et al. 2001; Light et al. 2004). While this model has been useful in various studies, there has been a lack of model-specific histomorphometric analysis that could provide supplemental evaluation in any of the treatment modalities. Various animal models have been used to study the effects of dermal burn injury including the pig (Singer et al. 2000), rabbit (Knabl et al. 1999), mouse (Cribbs et al. 1998), dog (Matsumura et al. 1997), guinea pig (Chu et al. 1990) and rat (Kim et al. 2001). A review of the literature points to histological studies that have been useful in determination of burn severity; however, direct application of these parameters to our model is confounded by potential factors such as different model species, different time of assessment following burn injury, or inconsistent lesion descriptions. In this manuscript, we describe morphological changes with the goal of defining reliable histological parameters for burn severity assessment in an acute burn rat model.

Methods

Animals

Fifteen adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan Labs, Indianapolis, IN, USA) with an average weight of approximately 460 g were housed and cared for under the direction of the MedStar Research Institute, Washington, DC, USA. Experiments were conducted in the Burn Center laboratory (MedStar Research Institute) conforming with local and national animal use and care guidelines with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval.

Standardized burn creation

For the terminal experiment, animals were anaesthetized with inhaled isoflurane to maintain adequate anaesthesia. Each animal's dorsal torso was shaved and then depilated using a commercial agent (Nair®; Church and Dwight Co., Inc., Princeton, New Jersey, USA). The proximal femoral artery and vein were isolated, cannulated with 22-gauge catheters and secured using magnification.

To create burns of varying severity, we followed the protocol in our previously reported model of thermal injury (Kim et al. 2001; Light et al. 2004). Briefly, the dorsum of each rat was premarked for contact burns with two rows of five 2-cm × 2-cm squares, each 1 cm apart. Custom-made 500-g aluminium branding irons with a contact surface of 2 cm × 2 cm were heated in a water bath to 100 °C for 30 min. Burns were created in a cephalad-to-caudad pattern with contact times of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 s. Five additional burns of 2-s duration each were placed on both flanks of the animal for an estimated total burn size of 30% total body surface area (TBSA) to replicate a major burn classification. Burn resuscitation [Lactated Ringers solution at 2 ml/kg/per cent total body surface area (%TBSA)/24 h] was initiated at the time of thermal injury. Resuscitation fluids were delivered intravenously (IV) using a continuous micro-infusion pump (Protégé 2010, Medex, Duluth, GA, USA). The animals were killed (carbon dioxide) 5 h after thermal injury.

Tissues

Prior to killing, biopsy samples were consistently collected (6-mm punch biopsy) from each burn location (1–14 s) and placed in a bath of 10% neutral-buffered formalin containing at least 20 volumes of fixative to tissue. In addition, two control tissues were biopsied in predetermined areas adjacent to the burned foci and were termed ‘watershed’ tissues. Following fixation, the samples were routinely processed, paraffin-embedded, sectioned (∼5 micrometers), stained with haematoxylin and eosin and cover slipped for histopathological examination.

Histopathological parameters and morphometry

To determine feasible histopathological parameters for burn severity assessment, a veterinary pathologist screened tissue sections from the model (a full time course from two animals) and reviewed the literature for possible microscopic markers of burn injury (Singer et al. 2000; Takamiya et al. 2001; Papp et al. 2004). Candidate tissue markers included collagen hyalinization, vascular patency, follicle cell injury, epidermal injury and subepidermal vesicle formation. The slides were then randomized and evaluated in a blinded manner for these tissue changes. Epidermal injury was scored from 0 to 3: (0) no lesion, (1) foci of keratinocyte cell swelling, uncommon epidermal thinning and/or elongation of nuclei, (2) foci of moderate to severe epidermal thinning and nuclear elongation, and (3) loss of discernible epidermal structure and significant epidermal thinning with elongate nuclei that are often parallel to the dermis.

For the remaining tissue parameters, the dermis was examined and the interface of normal and abnormal dermis (morphology defined in the Results section) determined. Each tissue section was digitized and the perpendicular distance between the surface epidermis and the burn parameter interface with normal tissue was defined (B×41 microscope, DP7 digital camera, and MicroSuite Pathology Edition software, Olympus).

Depth of collagen alteration was defined as the distance from the epidermis to the interface of normal collagen and collagen hyalinization with a corresponding loss of individual collagen fibre distinction. Depth of vascular patency was defined as the shortest distance from the epidermis at which was detected an undamaged blood vessel with intact erythrocytes in the central lumen. Depth of follicular injury was defined as the maximal depth at which follicle epithelia exhibited features consistent with cell injury (e.g. cell swelling, cytoplasmic vacuolization, nuclear pyknosis, etc.).

Statistical analysis

Ordinary simple linear and quadratic regressions of the various morphological parameters on the burn severity markers were used to see how well these parameters correlate to burn time and how easy their course can be predicted by burn time.

Results

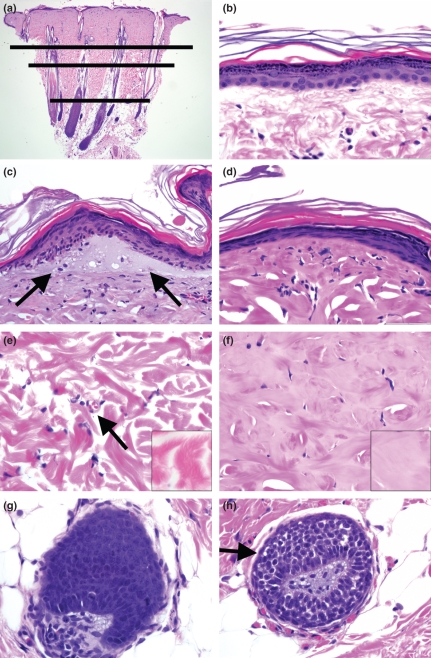

Watershed tissues (i.e. those biopsied adjacent to burn sites) typically had normal cellular integrity of epidermal and dermal structures. The only detectable alteration was mild superficial dermal oedema evidenced by separation of collagen fibres by clear space and superficial vascular congestion immediately subjacent to the epidermis. This was in contrast to burned tissue, which had a consistent stratification of morphological lesion detection (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Rat skin stained with haematoxylin and eosin 5 h following burns. (a) Low magnification tissue section showing the representative dermal stratification of burn parameter depth for collagen alteration (long line), vascular patency (medium line) and follicular cell injury (short line), 20×. (b) Superficial skin from a watershed control animal demonstrating uninjured epidermis, 600×. (c) Superficial skin with a subepidermal vesicle (arrows) and early epidermal thinning and nuclear elongation, 600×. (d) Superficial skin with severe thinning of epidermis. Note the elongate nuclei that are often parallel with the basement membrane, 600×. (e) Unburned rat dermis. Note the intact vasculature (arrow) and the distinct individual collagen fibres and bundles (inset), 600× and 1200×. (f) Burned rat dermis. Note the lack of patent vascular structures and absence of collagen fibre distinction (inset). Also note the relative homogeneity of the dermis in part due to mixing of grey background fluid with the collagen, 600× and 1200×. (g) Unburned hair follicle with intact uninjured epithelium, 600×. (h) Burned hair follicle with cellular damage (arrow) including cell swelling, cytoplasmic clearing and hyperchromatic nuclei, 600×.

Epidermal changes in tissues with short burn contact times were characterized by cell swelling/vacuolization of keratinocyte cytoplasm most often seen in the stratum basale and stratum spinosum. Focal sites of epidermal thinning with admixed nuclear elongation were occasionally present. Increased thermal contact time caused progressive thinning of the epidermis and remnant keratinocytes exhibited shrunken eosinophilic cytoplasm and extremely elongate nuclei that had become parallel with the dermal–epidermal junction. Occasionally, subepidermal vesicles filled with foamy pale grey material were detected and its formation decreased with increased burn time (Figure 1b–d).

Within the necrotic burn zone, there were no intact vascular structures and remnant nuclei were pyknotic to karyorrhectic. Defining features of the burn zone included alterations in the morphological appearance of the collagenous dermis. The necrotic dermis had a hyalinized collagen matrix that was set on a background of faintly eosinophilic to grey seroproteinaceous fluid. This interstitial oedema-like fluid was also seen filling some dilated draining lymphatics subjacent to the burn interface. While the interface between the necrotic and non-necrotic burn area were at times discernible from low power, the most often used diagnostic feature for this parameter was the visualization of individual undamaged collagen fibres (including those resembling a feathered-edge) that were detectable in the coagulated regions (Figure 1e,f). Within a high power microscopic field (i.e. 400–600×), the observer can easily discern normal and damaged collagen to define a region of interface.

Another attribute examined in the study was that of vascular patency. We defined this as the detection of an intact vascular structure in which undamaged erythrocytes resided in a clear space background within the vessel walls (Figure 1e). Patent vessels in the dermal tissue were principally detected deep to the burn. These small vessels were most noticeable near relatively vascular rich adnexal structures. Importantly, given the relatively short time frame from burn application to biopsy, vascular ectasia consistent with acute inflammation was diminutive. The most superficial patent vasculature structure detected during examination was used for the morphometry. Typically in one section, there were 1–5+ superficial vessels at the same level in the dermis demonstrating the relative consistency of parameter in the tissue.

The final parameter examined was that of follicle cell injury. Follicular epithelia were examined for evidence of cellular injury and the deep point of this parameter was used in morphometric analysis. Damaged follicular epithelia had morphological features consistent with cell injury including hydropic degeneration, cytoplasmic clearing, nuclear pyknosis and karyorrhexis (Figure 1g,h).

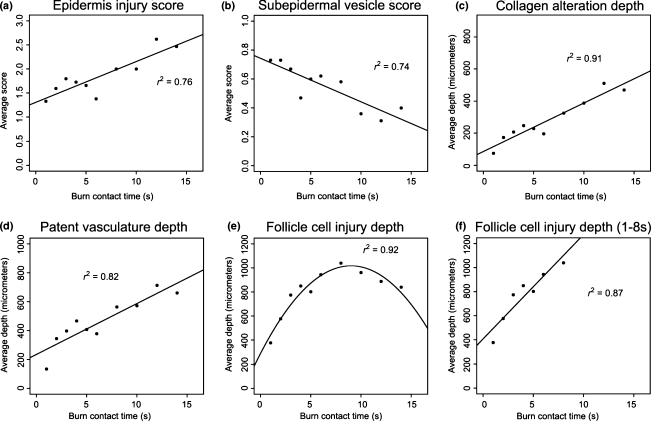

Scores of epidermal changes and presence of subepidermal vesicles along with morphometric analysis of collagen alteration, vascular patency and follicle cell injury were assessed for their detection of burn severity (Figure 2). Collagen alteration (r2 = 0.91) had the highest correlation with burn contact time followed by patent vascularity (r2 = 0.82), epidermal changes (r2 = 0.76) and the presence of a subepidermal vesicle (r2 = 0.74). Follicle cell injury would be ideally fitted through a quadratic regression model on contact time (r2 = 0.92). This, while statistically feasible, would be discordant with clinical and biological data such as inconsistent hair cycling among animals ranging from telogen to anagen that caused an artefactual plateauing of the burn depth detection in deep burns. The value of the follicle cell injury in early time points (e.g. 1- to 8-s contact times) was not affected by the stage of hair cycle as seen in the strong linear correlation (r2 = 0.87).

Figure 2.

Morphometric scores and measurements from rat skin with various burn severity. (a) Epidermal injury was scored 0–3 with increasing severity of scores observed through increased burn contact time (r2 = 0.76). (b) Subepidermal vesicle formation was scored 0 (absent) to 1 (present) and this parameter progressively decreased with increased burn contact time (r2 = 0.74). (c) Depth of collagen alteration extended deeper into the dermis with increased burn contact time (r2 = 0.91). (d) Patent vasculature depth was consistently deeper than collagen alteration and deepened with increased burn contact time (r2 = 0.82). (e) Follicle cell injury depth was described well in a quadratic formula (r2 = 0.92); however, it lacked biological significance because of the artefactual plateauing of burn depth detection in the deep burn times. (f) Follicle cell injury was useful for assessment in superficial to partial thickness burns as demonstrated from 1 to 8-s contact times using linear regression (r2 = 0.87).

Discussion

Thermal injury to the skin is generally characterized by variable necrosis and cell injury (Cribbs et al. 1998; Papp et al. 2004). Burns can generally be divided into three concentric tissue layers – the centre of the burn is a zone of coagulation, surrounded sequentially by a zone of ischaemia and finally the zone of hyperaemia (Gómez & Cancio 2007). The zone of coagulation is an area of devitalized tissue that often has a microscopic appearance of coagulation necrosis. The zone of ischaemia lies peripheral to the zone of necrosis. It is characterized by poor vascular perfusion and injured cells that are susceptible to necrosis. The zone of hyperaemia is adjacent to the zone of ischaemia and is characterized by intense vascular ectasia due in part to the inflammatory response. Burn depth is a measure of burn severity and can have profound influence on treatment modalities and eventual prognosis (DeSanti 2005; Gómez & Cancio 2007).

Burn depth in the skin is progressively classified into superficial, superficial partial-thickness, deep partial-thickness, full-thickness and subdermal burns (Johnson & Richard 2003). There is a wide divergence in the standard burn treatment depending on severity. Superficial burns require symptomatic medical care and usually offer a good prognosis. This is in great contrast to deeper burns that require surgical debridement and can have serious prognostic implications ranging from cosmetic (e.g. scarring) to mortal complications. The midpoint of the dermis is the localization of this diagnostic interface and happens to be consistent with the localization of the regenerative stems cells in the hair follicle bulge. These cells can differentiate into epidermis, follicle and adnexal structures and are often detected near the insertion of the arrector pili muscle (Ohyama 2007). Burns, which destroy these cells, are subject to more severe clinical implications. Burn specialists require an accurate assessment of burn depth in the early clinical examination as well as in the ensuing hours to days to successfully treat and monitor burn progression. This premise is true also in translational burn research where histopathological assessment can be a valuable tool to assess the efficacy of novel diagnostic aids, therapeutics and treatment modalities. Herein, we describe morphological parameters that characterize and correlate to burn severity in an acute burn rat model.

In this study, we describe superficial tissue parameters through scoring epidermal morphological changes and subepidermal vesicle formation. Both parameters had similar correlation to burn severity (contact time). For the pathologist, epidermal changes such as epidermal thinning and nuclear elongation were useful for rapid initial burn assessment of the tissue section. Nuclear elongation was at one time suggested to be morphologically diagnostic for electrocution and possibly thermal injuries, but recently epidermal thinning and nuclear elongation were demonstrated to be directly related to dermal swelling caused by a variety of injuries including electrical injury, thermal burns and contusions (Knight 1996; Takamiya et al. 2001). In the present study, we identified gradation in epidermal changes that corresponded with the degree of burn depth. While the correlation for burn severity was not as robust as collagen alteration, it did provide the pathologist with a low power assessment on the extent of burn injury in the dermis. While the formation of subepidermal vesicles decreased with burn severity, its relevant application may be limited in part due to the constraints of a binomial scoring system. Future efforts should explore more diverse morphometric analysis to better define this parameter.

Dermal components that were evaluated in the study included collagen alteration, vascular patency and follicle cell injury. Collagen alteration had the best correlation to burn contact time followed by the other dermal parameters. Collagen alteration in this model was optimally discerned on high power microscope with routine haematoxylin and eosin staining. Even so, microscope operation with low power magnification or through adjustment of the focus was helpful to fully appreciate the morphological alterations in the collagen structure. Investigators with limited pathology or histological experience may choose to utilize additional special stains to enhance detection of burn parameters such as collagen alteration. Techniques that can provide corroborative assessment of collagen alteration depth have included tinctorial stains (e.g. elastica-Masson tinctorial stain, damaged collagen stains reddish) and immunohistochemistry (e.g. ubiquitin or vimentin, reduced staining in burned dermis) (Nanney et al. 1996; Takamiya et al. 2001).

In one histopathological study of burns in a pig model, the identification of a seroproteinaceous fluid material interspersed between coagulated collagen fibres was undetermined (Singer et al. 2000). In this study, the seroproteinaceous fluid was intimately admixed with and between only altered collagen and the same material was seen in dilated draining lymphatics in the subjacent dermis. We believe this material represents a combination of cellular fluid and that was released from damaged cells and vascular structures in the zone of coagulative necrosis. Furthermore in the porcine model, collagen alteration was a highly reproducible parameter that had a consistent relationship with burn time similar to our results (Singer et al. 2000). Conversely, our results differed from that study in that we found a consistent depth relationship in burns to be collagen alteration < vascular patency < follicle cell injury whereas in the pig, the depth relationship was collagen alteration < follicle cell injury < vascular patency. A significant factor that could have contributed to this discrepancy is the duration from burn to biopsy, which was 30 min in the pigs and 5 h in our model – potentially allowing further morphological development of cell injury. In addition, inherent difference in species may play a role as well given the varying anatomical structure and consistency. Some investigators have used thrombosis as a histological aid in experimental burn tissue assessment (Watts et al. 2001; Papp et al. 2004). In this study, no evidence of thrombosis was noticed, but given the short time frame in our model, the induction of proinflammatory and thrombogenic events may not have reached a ‘critical mass’ as it did in other studies by 1–3 days postburn. Finally, follicular cell injury was readily detectable when follicles were present in tissue sections; however, the wide range of anagen to telogen hair follicles among animals complicated the detection of injury especially in deep burns (Figure 2e,f). It has been previously recognized that the stage of hair follicle cycle can affect burns through various means such as differing skin thickness (Zawacki & Jones 1967; Knabl et al. 1999). For this study, as we were further characterizing an already established model of burn injury that had not coordinated the cycle of hair follicle growth in the rats, we chose to be consistent with the model. Ultimately, morphological parameters such as collagen alteration were useful in the model and apparently independent of hair follicle cycle. Lastly, it is important for the investigator to be familiar with normal follicular structure so as to recognize normal morphological variation seen along the follicle structure and not call it a lesion.

Even though morphological assessment of experimental burn models has been variously described, our assessment of this model showed similarities and differences with descriptions in the literature. Our results highlight the need for investigators to define optimal histopathological parameters, each for their specific models. We found that epidermal and dermal changes can be useful for determining burn severity and that in our model, collagen alteration had the best correlation to burn severity. We believe the results of this study will be extremely useful in future experiments to evaluate novel therapeutics and treatment modalities in the acute rat burn model.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Eli Lilly Xigris Research Grant, Washington DC Firefighters Foundation, Carver College of Medicine Research Funds, and the UI Departments of Pathology and Surgery.

References

- Brigham PA, Dimick AR. The evolution of burn care facilities in the United States. J. Burn Care Res. 2008;29:248–256. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31815f366c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigham PA, McLoughlin E. Burn incidence and medical care use in the United States: estimates, trends, and data sources. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 1996;17:95–107. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CS, McManus AT, Mason AD, Jr, Okerberg CV, Pruitt BA., Jr Multiple graft harvestings from deep partial-thickness scald wounds healed under the influence of weak direct current. J. Trauma. 1990;30:1044–1049. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199008000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribbs RK, Luquette MH, Besner GE. A standardized model of partial thickness scald burns in mice. J. Surg. Res. 1998;80:69–74. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSanti L. Pathophysiology and current management of burn injury. Adv. Skin Wound Care. 2005;18:323–332. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200507000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl HP, Till GO, Trenz O, Ward P. Roles of histamine, complement and xanthine oxidase in thermal injury of skin. Am. J. Pathol. 1989;135:203–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez R, Cancio LC. Management of burn wounds in the emergency department. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 2007;25:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimbach DM, Afromowitz MA, Engrav LH, Marvin JA, Perry B. Burn depth estimation – man or machine. J. Trauma. 1984;24:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RM, Richard R. Partial-thickness burns: identification and management. Adv. Skin Wound Care. 2003;16:178–187. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DE, Phillips TM, Jeng JC, et al. Microvascular assessment of burn depth conversion during varying resuscitation conditions. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 2001;22:406–416. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200111000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita T, Ogawa M, Sato H, Kasai K, Tanak T, Tanaka N. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway on heart failure in the infant rat after burn injury. Int. J. Exp. Path. 2008;89:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2007.00561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knabl JS, Bayer GS, Bauer WA, et al. Controlled partial thickness burns: an animal model for studies of burn wound progression. Burns. 1999;25:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(98)00172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B. Electrical Fatalities. Forensic Pathology. 2nd edn. London: Arnold Publication; 1996. pp. 319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Light TD, Jeng JC, Jain AK, et al. Real-time metabolic monitors, ischemia-reperfusion, titration endpoints and ultraprecise burn resuscitation. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 2004;25:33–44. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000105344.84628.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura H, Yoshizawa N, Kimura T, Watanabe K, Gibran NS, Engrav LH. A burn wound healing model in the hairless descendent of the Mexican hairless dog. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 1997;18:306–312. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199707000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monafo WW. Initial management of burns. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:1581–1586. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611213352108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan MS, Till GO, Smith CW, et al. Role of leukocyte adhesion molecules in lung and dermal vascular injury after thermal trauma of skin. Am. J. Pathol. 1994;144:1008–1015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanney LB, Wenczak A, Lynch JB. Progressive burn injury documented with vimentin immunostaining. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 1996;17:191–198. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199605000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama M. Hair follicle bulge: a fascinating reservoir of epithelial stem cells. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2007;46:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp A, Kiraly K, Härmä M, Lahtinen T, Uusaro A, Alhava E. The progression of burn depth in experimental burns: a histological and methodological study. Burns. 2004;30:684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp A, Lahtinen T, Härmä M, Nuutinen J, Uusaro A, Alhava E. Dielectric measurement in experimental burns: a new tool for burn depth determination? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006;117:889–898. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000197213.12989.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham TN, Cancio LC, Gibran NS. American Burn Association practice guidelines: burn shock resuscitation. J. Burn Care Res. 2008;29:257–266. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31815f3876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce MC, Sheridan RL, Hyle Park B, Cense B, de Boer JF. Collagen denaturation can be quantified in burned human skin using polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography. Burns. 2004;30:511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan RL. Burn care: results of technical and organizational progress. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2003;290:719–722. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.6.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer AJ, Berruti L, Thode HC, McClain SA. Standardized burn model using a multiparametric histologic analysis of burn depth. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2000;7:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer AJ, Brebbia J, Soroff HH. Management of local burn wounds in the ED. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2007a;25:666–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer AJ, McClain SA, Romanov A, Rooney J, Zimmerman T. Curcumin reduces burn progression in rats. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2007b;14:1125–1129. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Still JM, Law EJ, Klavuhn KG, Island TC, Holtz JZ. Diagnosis of burn depth using laser-induced indocyanine green fluorescence: a preliminary clinical trial. Burns. 2001;27:364–371. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamiya M, Saigusa K, Nakayashiki N, Aoki Y. A histological study on the mechanism of epidermal nuclear elongation in electrical and burn injuries. Int. J. Legal Med. 2001;115:152–157. doi: 10.1007/s004140100250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts AM, Tyler MP, Perry ME, Roberts AH, McGrouther DA. Burn depth and its histological measurement. Burns. 2001;27:154–160. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki M, Sato S, Ashida H, Saito D, Okada Y, Obara M. Measurement of burn depths in rats using multiwavelength photoacoustic depth profiling. J. Biomed. Opt. 2005;10:064011. doi: 10.1117/1.2137287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawacki BE, Jones RJ. Standard depth burns in the rat: the importance of the hair growth cycle. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1967;20:347–354. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(67)80065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]