Abstract

The tumour microenvironment, which is largely composed of inflammatory cells, is a crucial participant in the neoplastic process through the promotion of cell proliferation, survival and migration. Neutrophil polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) induce inflammatory reactions that can be either cytotoxic for tumour cells or can promote tumour growth and metastasis. Previously, we have reported a spontaneous metastasis tumour model that has tumour PMNs infiltration, and metastasis, to liver and spleen. The aim of this study was to evaluate the PMNs influences on the tumour cell invasion and metastatic properties. We analysed intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), MT1-MMP (membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase) and MMP2 protein expression in TuE-t cells cultured with PMNs or PMNs-conditioned medium isolated from tumour bearing and normal rats. The interaction between tumour cells and PMNs induced a decrease in ICAM-1 expression in tumour cells as well as an increase in MMP2 and tumour cell motility. Besides, conserved expression of uPAR and MT1-MMP in tumour cells was also demonstrated. The up-regulation in MMP2 associated with uPAR and MT1-MMP conserved expression may be related to an increased extracellular matrix proteolysis. These results showed that the interaction of tumour cells with PMNs could favour tumour cell spreading through the promotion of a tumour invasive phenotype.

Keywords: intercellular adhesion molecule-1, metalloproteases, metastasis, neutrophils, tumour, uPA receptor

The relationship between inflammation, innate immunity and cancer is widely accepted (Coussens 2002). Early in the neoplastic process, inflammatory cells and their released molecular species influence the growth, migration and differentiation of all cell types in the tumour microenvironment, whereas later in the tumourigenic process, neoplastic cells also develop inflammatory mechanisms, such as metalloproteinase production and chemokine/cytokine functions to favour tumour spread and metastasis (Liotta & Kohn 2001; Queen et al. 2005). Although the chemokines are potent and selective chemoattractive agents for different types of leucocytes, the chemokine system is remarkably promiscuous (Pease & Williams 2006) targeting a variety of normal and pathological cells. Nevertheless, chemokines are a major determinant of the type and number of leucocytes accumulating in inflammatory sites and in tumours (Sica et al. 2006).

The inflammatory component of a developing neoplasm includes a diverse leucocyte population, e.g. macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, and mast cells. Recent studies have shown that the tumour-associated leucocytes are variably loaded with an assorted array of cytokines, cytotoxic mediators as well as proteolytic enzymes (Kuper et al. 2000; Di Carlo et al. 2001) that promote all the steps associated with malignancy within tumours (Ribatti et al. 2001). However, the role of neutrophils polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) in tumour progression is still controversial. In vivo experimental studies show that circulating PMNs isolated from tumour bearing animals reduce the number of metastatic foci in the lungs (Lin & Pollard 2004). On the other hand, in vitro studies reveal that PMNs stimulate tumour cell attachment to endothelial monolayers, a relevant step for tumour migration (Starkey et al. 1984; Ishihara et al. 1998). Moreover, other authors have shown that tumour-associated PMNs were involved in tumour angiogenesis by the production of VEGF and IL-8, and in the invasion phenomenon, by the release of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and elastase (Iwatsuki et al. 2000; Shamamian et al. 2001; Schaider et al. 2003).

Matrix metalloproteinases are a family of zinc-binding endopeptidases, which are classified into soluble and membrane type-MMPs (MT-MMPs) (Egeblad & Werb 2002; Sounni et al. 2003). The activity of MMPs is regulated mainly by the activation of zymogens (pro-MMPs) and the MMPs inhibition by their common tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (Seiki & Yana 2003). Special attention was devoted to MMP2 and MT1-MMP enzymes in neoplasia. Tumour-derived MMP2 has been related with extracellular matrix (ECM) cleavage and matrix adhesion promotion in the initial steps of ovarian carcinogenesis (Kenny et al. 2008). In addition, MT1-MMP, an integral membrane proteinase frequently expressed in malignant cancer cells, is not just an enzyme that degrades ECM, but cleaves cell adhesion molecules and activates latent forms of MMPs (Kurschat et al. 1999; Seiki & Yana 2003).

Another proteolytic system involved in the metastatic process is the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) system, which consists of uPA, uPA receptor (uPAR) and uPA inhibitors 1 and 2 (PAI-1 and PAI-2). By binding uPA, uPAR localizes proteolytic activity to the leading edge of the cell, thereby facilitating cellular migration and penetration of tissue boundaries (Nguyen et al. 2000). Besides, uPA catalyses the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, which activates other proteases including some MMPs (Morgan & Hill 2005).

On the other hand, tumour cells interact with various host cells and ECM components by adhesion molecules expressed on the cell surface. Among these molecules, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) mainly participates in the interaction between target cells and cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. In this sense, the down regulation of ICAM-1 on tumour cells could be seen as a mechanism of immune evasion (Yasuda et al. 2001).

In this work we used an animal tumour model previously described by us (Donadio et al. 2002). The inoculation of TuE-t cells -a rat sarcoma cell line established in our laboratory- into the mammary pad gland of Wistar rats generates a tumour mass in the site of injection, accompanied by an important infiltration of PMNs (M.M. Remedi, unpublished observations) and the simultaneous presence of metastasis in the liver and spleen (Donadio et al. 2005). Here, we designed an experimental model in vitro that allowed us to evaluate how PMNs-derived products could influence tumour cell metastatic properties. The effect of PMNs on cell spreading and invasion of tumours is discussed.

Materials and methods

Cells, culture conditions and tumour model

TuE-t cells – a rat sarcoma cell line – were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (RPMI-FBS) (Natocor, Córdoba, Argentina) and 40 μg/ml gentamicin in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C.

Female, 75–90 days old Wistar rats were injected in the mammary pad gland with 1–2 × 106 TuE-t cells in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4. Animals were monitored regularly for tumour development as previously described (Donadio et al. 2002), and killed 2 weeks after tumour cells implantation.

Polymorphonuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood from normal and tumour bearing rats using the dextran-Ficoll technique described by Wang et al. (1997). Contaminating erythrocytes were removed by hypotonic lysis and the isolated PMN were suspended in RPMI 1640 containing 0.25% bovine serum albumin (RPMI-BSA). Cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Preparation of conditioned media

Polymorphonuclear cell-conditioned medium was prepared by incubating PMNs (5 × 106 PMN/ml) from normal (CM-Normal) and tumour bearing rats (CM-Tumour) in RPMI-BSA during 2 h. Culture supernatant was collected, centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min and conserved at −80 °C until use.

De-adhesion assay

TuE-t cells (10 × 104 cells/well/96-well plate) were grown in RPMI-FBS during 48 h in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. Cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS and cultured for 3 h at 37 °C with 100% CM-Normal, 100% CM-Tumour or RPMI-BSA (basal condition). After culture, the wells were washed twice with serum free medium and the adhered cells were fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde. The cells were stained with crystal violet (0.2%) during 25 min. The dying was solubilized in acetic acid (33% v/v) and the absorbance was read at 595 nm. The percentage of de-adhesion was calculated as % de-adhesion = [100 − % of adhered cells], taking as 100% the OD obtained in basal conditions.

Flow cytometry

TuE-t cells (2.5 × 105 cells/well/24-well plate) were grown in RPMI-FBS during 18 h in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. Cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS and cultured for 3 h at 37 °C with 100% PMN-conditioned medium or RPMI-BSA. After culture, the cells were harvested, fixed with 2% formol and stored at 4 °C for FACs analysis. Fixed cells were stained using a direct immunofluorescence for MT1-MMP or indirect immunofluorescence technique for the detection of ICAM-1 and uPAR antigens. Cells (5 × 105) were incubated with FITC-labelled anti-MT1-MMP (sc-12366; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. For indirect immunofluorescence 5 × 105 cells were incubated with anti-ICAM-1 (1A29 Cerdalane, Hornby, Ontario, Canada) or anti-uPAR (polyclonal antibody, a gift from Dr Francesco Blasi, Department of Molecular Biology and Functional Genomics, DIBIT, Milan, Italy) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by 1 h incubation with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (F-1010; Sigma Chemical Co.) or anti-rabbit IgG (401314; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) respectively as secondary antibody. A mouse non-related IgG was used as isotype control. After washing in PBS, the cells were analysed on a flow cytometer (Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Johnson & Johnson, Co., Raritan, NJ, USA).

Data were expressed as the ratio of intensity of fluorescence (RIF). RIF was calculated for each sample as the ratio between the mean fluorescence intensity value generated by the specific antibody and the mean fluorescence intensity value generated by the isotype control antibody. Percentage of RIF in the different treatments was calculated taking the RIF in basal conditions as 100%.

Zymography

TuE-t cells (2.5 × 105 cells/well/24-well plate) were grown in RPMI-FBS during 18 h in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. Cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS and 25% PMN-conditioned medium or PMN cells (1.25 × 105 cells/well) were added to the TuE-t cell monolayer. After 18 h of culture, supernatants were harvested, centrifuged at 6500 g for 3 min and stored at −80 °C until use. Gelatinolytic activity of MMP2 and MMP9 were analysed by electrophoresis under non-reducing conditions on 7.5% SDS-PAGE copolymerized with 1.5% gelatin as substrate (gelatin SDS-PAGE). After electrophoresis, the gel was washed in 2.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min to remove SDS. After rinsing twice in substrate buffer [50 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 200 mm NaCl, 9 mm CaCl2], gels were incubated at 37 °C for 40 h in the same buffer. Gels were stained for 45 min in 45% methanol-5% glacial acetic acid containing 0.125% (w/v) Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250 and destained in 25% ethanol/10% glacial acetic acid. White zones on the gels indicate the gelatinolytic activity of proteinases. The intensity of bands was estimated using image analyser software (scion free Version online, Scion Corporation, MD, USA).

Wound healing assay

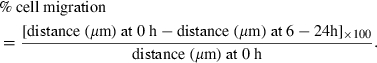

TuE-t cells (4 × 104 cells/well/24-well plate) were grown in RPMI-FBS for 48 h in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. After culture, a wound was made using the white tip (10 μl) of a pipette. After gentle rinsing twice with PBS to remove detached cells, 5% CM-Normal, 5% CM-Tumour or RPMI-BSA were added. Immediately following scratch wounding (0 h) and after incubation of cells at 37 °C for 6, 12 and 24 h, phase-contrast images (10× field) of the wound healing process were photographed digitally with a Nikon inverted microscope ECLIPSE TE2000-U. The distances of the wound areas were measured on the images. The percentage of migration was calculated as:

|

Results

Effect of PMN-conditioned medium in tumour cell adhesion

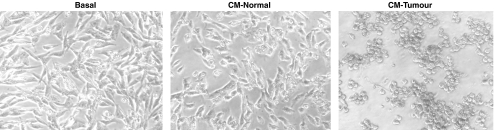

The incubation of TuE-t cells with 100% CM-Tumour induced a fast detachment (3 h) of the plated cells (Figure 1). A de-adhesion assay was performed in order to quantify tumour cell detachment in the presence of PMN-conditioned medium. A significant detachment of TuE-t cells was observed with CM-Tumour [85.0% (±6.2)] respect to CM-Normal [8.7% (±10.1)] and RPMI-BSA (P≤0.01). No significant differences were registered between CM-Normal and basal conditions.

Figure 1.

Detachment of TuE-t cells by PMN-conditioned medium. TuE-t cells were cultured with RPMI-BSA (basal), 100% of CM-Normal or 100% of CM-Tumour during 3 h. The complete detachment of TuE-t cells was observed with CM-Tumour.

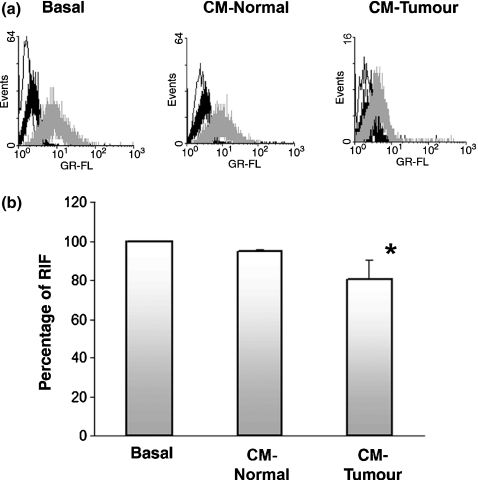

In vitro analysis of ICAM-1, uPAR and MT1-MMP expression

We previously demonstrated that cultured TuE-t cells constitutively express ICAM-1 antigen in a high percentage of the cells. In contrast, a low frequency of ICAM-1 positive cells was observed in in vivo tumour cells (Donadio et al. 2002). The detachment of cultured TuE-t cells in the presence of 100% CM-Tumour could be related with the loss of adhesion molecules. In order to check a possible modulation in tumour cell-associated ICAM-1 protein by soluble factors released from PMNs, TuE-t cells were incubated for 3 h with CM-Normal, CM-Tumour or RPMI-BSA. ICAM-1 protein expression was assessed in TuE-t cells by flow cytometry. We found a decreased ICAM-1 expression in cells incubated with CM-Tumour (Figure 2a). ICAM-1 diminution was quantified by the calculation of RIF, showing a significant difference between CM-Tumour treatment and CM-Normal and basal conditions (Figure 2b; P ≤ 0.05). Similarly, assays performed using 25% and 50% of PMN-conditioned media showed resembling results, although no significant differences in ICAM-1 cell-associated protein expression were reached.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface ICAM-1 expression. (a) TuE-t cells cultured with 100% CM-Normal, CM-Tumour and RPMI-BSA (basal) were collected, fixed and analysed by flow cytometry. Representative data of at least three independent experiments are shown. White peak: secondary antibody alone; black peak: isotype control antibody; grey peak: specific primary antibody. Percentage of RIF (b) in PMN-conditioned medium treated TuE-t cells and in basal conditions is depicted. Data represent the mean ± SD. Values significantly different from basal conditions (using Kruskal–Wallis test) are marked with an asterisk (*P ≤ 0.05).

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor and MT1-MMP are cell surface molecules involved in proteolysis of ECM and cell movement. We previously demonstrated the presence of uPAR and MT1-MMP antigens in TuE-t cells both in vitro and in vivo (Donadio et al. 2002, 2005). To evaluate the effect of soluble factors released from PMNs in tumour cell MT1-MMP and uPAR protein expression, TuE-t cells were incubated with CM-Normal, CM-Tumour or RPMI-BSA. MT1-MMP and uPAR protein expression was assessed by flow cytometry.

Neither uPAR nor MT1-MMP levels on cultured TuE-t cells were modified by the presence of PMN-conditioned medium (data not shown).

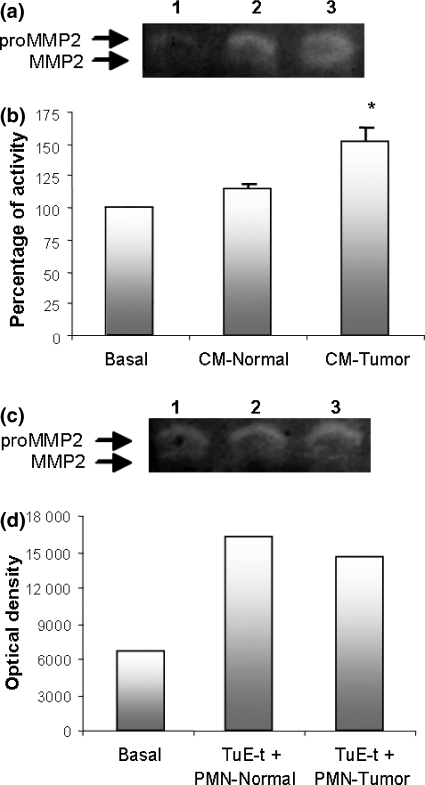

Analysis of MMP activities on TuE-t cell supernatants

Considering that MMP2 and MMP9 have been related to the ability of tumour cells to overcome tumour boundaries and to migrate to surrounding tissues, we analysed MMP2 and MMP9 activities in culture supernatants obtained from TuE-t cells incubated with PMNs or PMN-conditioned medium.

We previously demonstrated that the conditioned media of TuE-t cell cultures contain gelatinolytic activities equivalent to pro-MMP2, active MMP2, and pro-MMP9 (Donadio et al. 2005). When TuE-t cells were incubated with CM-Tumour a significant increase (P ≤ 0.05) in pro-MMP2 activity was observed compared with pro-MMP2 activities in TuE-t cell cultures with CM-Normal or RPMI-BSA (Figure 3a,b). Pro-MMP2 protein in PMN-conditioned medium was negligible (data not shown). Similarly, an increase in pro-MMP2 activity was also observed when TuE-t cells were co-cultured with PMN cells isolated from normal or tumour bearing rats (Figure 3c,d). Taken together, these results indicate that PMNs-derived factors can stimulate the production of pro-MMP2 by tumour cells. MMP9 activity could not be evaluated because of the high production of this enzyme by PMNs.

Figure 3.

Gelatin zymography from TuE-t cells culture supernatants. TuE-t cells were cultured with RPMI-BSA (basal), 25% CM-Normal, 25% CM-Tumour (a,b) or co-cultured with PMNs from normal or tumour bearing rats (c,d). Supernatants were analysed by gelatin zymography and protease activity is indicated as clear bands. (a) MMP2 in TuE-t cells cultured with RPMI-BSA (Lane 1), CM-Normal (Lane 2) and CM-Tumour (Lane 3). (b) Zymograms were scanned and the pixel density of each band was determined by scanning densitometry. Percentage of increase in pro-MMP2 protein expression respect to basal conditions is shown. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Values significantly different from basal conditions (using Kruskal–Wallis test) are marked with an asterisk (*P ≤ 0.05). (c) MMP2 in TuE-t cells co-cultured with PMNs (Lanes 1: TuE-t cells without PMNs; 2: TuE-t cells + PMNs from normal rats; 3: TuE-t cells + PMNs from tumour bearing rats). (d) The optical density of a representative experiment of two with similar results is depicted.

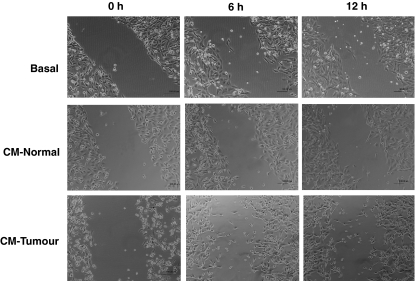

TuE-t cells migration into the wound area

The ability of TuE-t cells to migrate into the wound area was assessed over 24 h. Tumour cell monolayers were incubated in 5% CM-Normal, 5% CM-Tumour or RPMI-BSA. No higher proportions of conditioned media were used to avoid the detachment of the cells. Microphotographs were taken at various times after wound formation. By 6 h, TuE-t treated with CM-Normal started to populate the wound (Figure 4). At 12 h of culture, cells moved into the wound area, but no significant differences in relation with basal conditions were reached (Table 1). At 24 h, the wound was almost entirely covered (data not shown). In contrast, the treatment with CM-Tumour increased cell movement, evidencing a significant migratory effect respect to basal conditions at 6 and 12 h (P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01 respectively, Table 1). Nevertheless at 24 h of culture, cells treated with CM-Tumour were completely detached and the cell migration was not analysed (data not shown). In contrast, the cells cultured in basal condition (RPMI-BSA) did not significantly populate the wound area at any time analysed.

Figure 4.

Wound healing assay. A wound was made in the TuE-t cell monolayers and the cells were cultured with RPMI-BSA (basal), 5% CM-Normal or 5% CM-Tumour for 24 h. The closure of the wound is shown at 0, 6 and 12 h of culture.

Table 1.

TuE-t cells migration into the wound area

| Percentage of migration (%; mean ± SD) |

||

|---|---|---|

| 6 h | 12 h | |

| Basal | 21.7 ± 10.8 | 23.4 ± 7.7 |

| CM-Normal | 30.1 ± 15.9 | 42.1 ± 17.6 |

| CM-Tumour | 40.7 ± 14.7* | 45.5 ± 10.1** |

The ability of cells to migrate into the wound area was assessed over 24 h. The percentage of TuE-t cells migration was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Data are presented as the mean value of three independent experiments.

The asterisks (*P≤ 0.05; **P≤ 0.01; anova test) indicate significant differences between CM-Tumour and basal conditions.

Discussion

Using an experimental tumour model, we previously observed progressive tumours associated with PMNs-infiltration (Donadio et al. 2002). The PMNs were present not only in tumour sites but also in other organs such as the liver, which is a target for metastasis. In this study, we demonstrated that PMNs-soluble factors down regulate ICAM-1 expression on TuE-t cells. Although the molecular mechanism of the ICAM-1 diminution by PMNs soluble factors was not indicated, this down regulation could be attributed to the proteolysis by PMNs proteinases such as elastase, urokinase and MMPs. The cell surface diminution of ICAM-1 could impair the T-cell recognition and contribute to neoplastic dissemination through a defective antitumour response (Chen et al. 2006). Moreover, the ICAM-1 molecule could be released as soluble ICAM-1 (s-ICAM-1) which would promote haematogenous metastasis by suppressing local anticancer immunity (Maruo et al. 2002). Although the s-ICAM-1 production is not completely known, evidence indicates the proteolytic cleavage from cell surface (Shi et al. 2003). These observations are in accordance with our spontaneous metastasis model, where the level of ICAM-1 on tumour cells showed a down regulation during tumour progression (Donadio et al. 2002).

Matrix metalloproteinases are proteinases involved in tumour invasion and metastasis. In our system, we observed an enhanced expression of MMP2 on TuE-t cells when they were incubated with PMN-conditioned medium. In addition, this stimulatory effect on MMP2 expression was also demonstrated in co-cultures of TuE-t cells with PMNs cells. A possible mechanism for MMP2 up-regulation could be mediated by IL-8 produced by PMNs. It has been demonstrated that IL-8 is up-regulated in PMNs upon co-culturing with tumour cells (Peng et al. 2007). Besides, Mian et al. (2003) have demonstrated that IL-8 produced by human transitional cell carcinoma increases the tumourigenicity and metastasis by the up-regulation in the expression and activity of MMP2 and MMP9. PMNs from tumour bearing rats could produce more IL-8 than PMNs from normal rats and by this means increase the MMP2 expression. To test this hypothesis, we treated PMNs obtained from normal rats with PMA, which does not affect the IL-8 release (Lund & Osterud 2004). Conditioned medium from PMA-activated PMNs did not induce the increase in the MMP2 expression observed when we used CM-Tumour (data not shown). TGF-β is another candidate for the activation of MMP2 expression as PMNs could produce this cytokine and it has been reported that TGF-β is able to stimulate production on MMP2 in monocytes (Ma et al. 2004). However, more studies need to be addressed to clarify this point.

Besides, we demonstrated here that uPAR and MT1-MMP are expressed on TuE-t cells and their expressions were not affected by PMNs. Both uPAR and MT1-MMP presence is important not only for their effect on MMP2 activation but also for their roles in cell locomotion and matrix degradation (Hotary et al. 2003). Moreover, it has been speculated that binding to MT1-MMP generates conformational changes in pro-MMP2 that make a cleavage site in the prodomain region available for PMN-derived serine proteinases (Egeblad & Werb 2002). On the other hand, Kugler et al. (2003) showed that sustained uPAR expression mediates the loss of cell–cell contact and the increase of cell motility. TuE-t cells are able to produce uPA (data not shown) binding uPAR, leading to membrane-associated extracellular proteolysis and driving signals through transmembrane proteins, thus regulating cell migration, adhesion and cytoskeletal status (Alfano et al. 2005).

Taken together, our results demonstrate that the PMNs infiltrating tumours are able to modify tumour cell phenotype making them more suitable for invasion and metastasis. Importantly, the results observed in the adhesion and wound healing assays are consistent with the changes in the expression of adhesion molecules in TuE-t cells induced by PMN-conditioned medium, providing a more invasive phenotype. On the other hand, the marked increase in MMP2 production by TuE-t cells in association with the conservation of uPAR and MT1-MMP surface expression may be related to proteolysis of the ECM, cell adhesion molecules and cell spreading promotion. In addition, decreased ICAM-1 expression could be attributed to proteinases and its change could impair T-cell recognition and favour cell–cell detachment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Secretaría de Ciencia y Tecnología de la Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (SECyT-UNC), Agencia de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica de la República Argentina (FONCyT) and Consejo de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET).

References

- Alfano D, Franco P, Vocca I, et al. The urokinase plasminogen activator and its receptor: role in cell growth and apoptosis. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;93:205–211. doi: 10.1160/TH04-09-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PW, Uno T, Ksander BR. Tumor escape mutants develop within an immune-privileged environment in the absence of T cell selection. J. Immunol. 2006;177:162–168. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens LM. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo E, Forni G, Lollini P, Colombo MP, Modesti A, Musiani P. The intriguing role of polymorphonuclear neutrophils in antitumor reactions. Blood. 2001;97:339–345. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donadio AC, Remedi MM, Frede S, Bonacci GR, Chiabrando GA, Pistoresi-Palencia MC. Decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) is associated with tumor cell spreading in vivo. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 2002;19:437–444. doi: 10.1023/a:1016329802327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donadio AC, Durand S, Remedi MM, et al. Evaluation of stromal metalloproteinases and vascular endothelial growth factors in a spontaneous metastasis model. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2005;79:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;3:161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotary KB, Allen ED, Brooks PC, Datta NS, Long MW, Weiss SJ. Membrane type I matrix metalloproteinase usurps tumor growth control imposed by the three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Cell. 2003;114:33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara Y, Iijima H, Matsunaga K. Contribution of cytokines on the suppression of lung metastasis. Biotherapy. 1998;11:267–275. doi: 10.1023/a:1008070025561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsuki K, Kumara E, Yoshimine T, Nakagawa H, Sato M, Havakawa T. Elastase expression by infiltrating neutrophils in gliomas. Neurol. Res. 2000;22:465–468. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2000.11740701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny HA, Kaur S, Coussens LM, Lengyel E. The initial steps of ovarian cancer cell metastasis are mediated by MMP-2 cleavage of vitronectin and fibronectin. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:1367–1379. doi: 10.1172/JCI33775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler MC, Wei Y, Chapman HA. Urokinase receptor and integrin interactions. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2003;9:1565–1574. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper H, Adani HO, Trichopoulos D. Infections as a major preventable cause of human cancer. Intern. Med. 2000;248:171–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurschat P, Zigrino P, Nischt R, et al. Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-2 regulates matrix metalloproteinase-2 activation by modulation of membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase activity in high and low invasive melanoma cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:21056–21062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EY, Pollard JW. Role of infiltrated leucocytes in tumor growth and spread. Br. J. Cancer. 2004;90:2053–2058. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotta LA, Kohn EC. The microenvironment of the tumor-host interface. Nature. 2001;411:375–379. doi: 10.1038/35077241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund T, Osterud B. The effect of TNF-alpha, PMA, and LPS on plasma and cell-associated IL-8 in human leukocytes. Thromb. Res. 2004;113:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Chang MJ, Shah R, Adamski J, Zhao X, Benveniste EN. Brg-1 is required for maximal transcription of the human matrix metalloproteinase-2 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:46326–46334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo Y, Gochi A, Kaihara A, et al. ICAM-1 expression and the soluble ICAM-1 level for evaluating the metastatic potential of gastric cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2002;100:486–490. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian BM, Dinney CP, Bermejo CE, et al. Fully human anti-interleukin 8 antibody inhibits tumor growth in orthotopic bladder cancer xenografts via down-regulation of matrix metalloproteases and nuclear factor-kappaB. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:3167–3175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan H, Hill PA. Human breast cancer cell mediated bone collagen degradation requires plasminogen activation and matrix metalloproteinase activity. Cancer Cell Int. 2005;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DH, Webb DJ, Catling AD, et al. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator stimulates the Ras/Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signalling pathway and MCF-7 cell migration by a mechanism that requires focal adhesion kinase, Src, and Shc. Rapid dissociation of GRB2/Sps-Shc complex is associated with the transient phosphorylation of ERK in urokinase-treated cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:19382–19388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909575199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease JE, Williams TJ. Chemokines and their receptors in allergic disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006;118:305–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng HH, Liang S, Henderson AJ, Dong C. Regulation of interleukin-8 expression in melanoma-stimulated neutrophil inflammatory response. Exp. Cell Res. 2007;313:551–559. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queen MM, Ryan RE, Holzer RG, Keller-Peck CR, Jorcyk CL. Breast cancer cells stimulate neutrophils to produce oncostatin M: potential implications for tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8896–8904. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Vacca A, Nico B, Crivellato E, Roncali L, Dammacco F. The role of mast cells in tumor angiogenesis. Br. J. Haematol. 2001;115:514–521. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaider H, Oka M, Bogenrieder T, et al. Differential response of primary and metastatic melanomas to neutrophils attracted by IL-8. Int. J. Cancer. 2003;103:335–343. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiki M, Yana I. Roles of pericellular proteolysis by membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase in cancer invasion and angiogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:569–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamamian P, Schwartz JD, Pocock BJ, et al. Activation of progelatinase A (MMP-2) by neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, and proteinase-3: a role for inflammatory cells in tumor invasion and angiogenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2001;189:197–206. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Benderdour M, Lavigne P, Ranger P, Fernandes JC. Evidence for two distinct pathways in TNFα-induced membrane and soluble forms of ICAM-1 in human osteoblast-like cells isolated from osteoarthritic patients. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;15:300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sica A, Schioppa T, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages are a distinct M2 polarised population promoting tumour progression: potential targets of anti-cancer therapy. Eur. J. Cancer. 2006;42:717–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sounni NE, Janssen M, Foidart JM, Noel A. Membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase and TIMP-2 in tumor angiogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey JR, Liggitt HD, Jones W, Hosick HL. Influence of migratory blood cells on the attachment of tumor cells to vascular endothelium. Int. J. Cancer. 1984;34:535–543. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910340417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JH, Sexton DM, Redmond HP, Watson RWG, Croke DT, Bouchier-Hayes D. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) is expressed on human neutrophils and is essential for neutrophil adherence and aggregation. Shock. 1997;8:357–361. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda M, Tanaka Y, Tamura M, et al. Stimulation of beta1 integrin down-regulates ICAM-1 expression and ICAM-1-dependent adhesion of lung cancer cells through focal adhesion kinase. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2022–2030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]