The founders of AcademyHealth played a decisive role in advancing the health services field. Some, like Dr. Barbara McNeil, accomplished it through education and training of generations of health services researchers. Others, like Dr. Ron Andersen, achieved it through the development of theoretical models that resulted in a paradigm shift in how we conceptualize health services utilization. Still others, like Dr. Sam Shapiro, transformed the substantive nature of what we call health services research by linking structure and process to outcomes and asking questions such as, “What effect does being in a high performing organization have on the outcomes of care?”

As we join to celebrate 25 years of AcademyHealth, I want to look forward toward the critical role our field will play in the next 25 years. My message is simple: We now need to move health services research from a science of recommendation to a science of implementation. We cannot wait any longer for others to implement our recommendations.

Fifteen years ago, I reviewed the central problems in the field of mental health services research and identified unmet need for behavioral health services, lack of adherence to pharmacological therapies, inadequate retention in behavioral health care, and poor resource allocation of mental health providers as persistent problems requiring solutions. I found that, although there was a considerable knowledge base available to solve these problems and a substantial body of recommendations, we had no Randy Moss (an American football wide-receiver for the New England Patriots) at the other end to grab the recommendations and run with them.

So, I asked myself, why? Why is there such an enormous gap between the recommendations about how to solve enduring problems and the implementation of these recommendations? In fact, Lavis et al. (2003) referred to this gap as “the paradox of health services research, i.e., if it is not used, why do we produce so much of it?” I think it is critically important that we ask ourselves, “Why are ongoing health services research problems still with us today?” The answer to this question warrants serious reflection and debate among researches, policy makers, funders, and the wider public who support our field with their tax dollars.

I am not the only one asking this question. Some believe that health services problems do not get solved because the nature of the evidence is inadequate and have called for what are referred to as “practical clinical trials” (PCTs). In an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Tunis, Stryer, and Clancy (2003) stated: “The widespread gaps in evidence-based knowledge suggest that fundamental flaws exist in the production of scientific evidence, in part because there is no consistent effort to conduct clinical trials designed to meet the needs of decision makers.” The numbers of PCTs are restricted chiefly because the key funders of clinical research, such as the National Institutes of Health, do not focus on supporting such trials.

Others have suggested that the knowledge base is inadequate because research evidence by itself may be insufficient. For example, Claxton, Cohen, and Neumann (2005) argue that evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) does not tell us whether an intervention should be adopted. RCTs are not intended to address implementation issues or consideration of the benefits relative to the costs involved in the adoption of the intervention, or to provide contrasts to other alternative options of treatment.

It might not be the nature of the evidence that is problematic, but the use of that evidence for decision making that might be imperfect. Although Claxton, Cohen, and Neumann (2005) recommend decision analysis (such as the use of probability-weighted consequences in terms of QALYs) or value-of-information analysis, adoption and implementation of the evidence appears to require much more than evidence for decision making.

Some may view the problem of not having adequate evidence-based information as due to a lack of dissemination of evidence-based research and offer a short-sighted view of the need to invest in the process of implementation. The distance between the people who produce the information and the people who use the information—for example, end-users such as a clinician working in a safety net clinic or an immigrant worker who goes to his primary care doctor—is vast. We do not do much to minimize this distance—not even asking if the information we are producing will be valuable to the end-users. We basically produce the evidence and go on to the next research problem.

One likely problem with taking off-the-shelf recommendations from health services research is that they are filled with assumptions not supported by observable deliberations in real-life circumstances. This disconnect with everyday practice suggests that to move from a science of recommendation to a science of implementation, we need to better understand the assumptions involved in using the evidence for decision making or for anticipating the actual behaviors of consumers, payers, providers, or policy makers.

Let me offer a series of examples.

First, if you think about how patients and health care providers use the evidence for decision making and assume that providers will simply look at treatment alternatives and ask, “Of existing treatment alternatives, which makes the most sense for an individual patient?” you are making several potentially misinformed assumptions. The first assumption is that the patient or provider is aware and knowledgeable regarding the patient's treatment alternatives. The second assumption is that the patient understands his/her illness and prioritizes that illness and the risks and benefits associated with treatment decisions (including no treatment). These assumptions might be totally wrong.

Another area of common concern is the evidence that consumers do not use ratings of physician quality (Dolan 2008) in choosing physicians. Imagine that you assume that patients are only concerned with, “Which plan or physician is likely to provide me with high quality care?” In posing this as the relevant question, there are the potentially erroneous assumptions that the patient has access to a diverse pool of physicians, that he/she is likely to have access to the highest quality physicians, and that quality care is her/his primary priority (not cost or ease of obtaining services). Again, are these assumptions realistically expected to operate for most patients or for most conditions that patients have?

There are also assumptions about how providers will use quality improvements. The premise of quality improvements is that they will improve performance “by setting aims, examining processes of care, testing changes in these processes, and implementing those changes that improve results (Baker 2006).” We may think that providers usually assess their healthcare processes and that they have adequate supervision, support, and desire to change practice in light of the findings of these assessments. But how likely is it that providers see themselves as collecting information to improve quality and that they can easily change practice given other regulatory and institutional constraints?

Furthermore, what happens if you assume that providers will gravitate toward the use of evidence-based practices because they mainly focus on the simple question, “What is the best evidence-based approach for patients with selected conditions?” Once more, this question will prove meaningless if based on flawed assumptions, for example, that there are practice guidelines accessible for given conditions, and that the physician treating the patient is familiar with and informed by the guidelines and has the infrastructure support to implement them. Unfortunately, we know many conditions do not have strong evidence-based guidelines (e.g., eating disorders, peptic ulcers, chronic pain), and dissemination of guideline—concordant care is in its infancy (Davis and Howden-Chapman 1996).

Similar untested assumptions about how payers approach questions related to product purchasing and formulary selection have been posed. Imagine that when we provide information to payers we cast the question as: “How does this product compare with existing alternatives?” Again, we may incorrectly assume that the payer has access to a range of product options that are easily obtained and that there is a process in place to create uptake of these alternatives. But once more, the way we assume things will play out in the health care environment is naïve and full of misguided suppositions.

Currently, we make many untested assumptions about how people use research evidence for decision making, including that these are the questions they want answered. But given these potentially faulty assumptions, it leads me to question whether we will have another 20-year gap between when knowledge is produced and when uptake occurs.

The number of evidence-based research findings in both the natural and social sciences that have been translated into clinical practice is discouragingly small (Kerner, Rimer, and Emmons 2005; Zerhouni 2005). A recent study in Canada assessing why decision makers fail to use research findings found that 76 percent of those surveyed commented on the lack of relevant usable research for knowledge translation and integration (Kiefer et al. 2005). Green and Glasgow (2006) caution that criteria typically used to judge the scientific merit of interventions (internal validity) mostly ignore the external validity that is so relevant for service administrators, clinicians, and policy makers. As a consequence, practitioners often complain that research findings may not apply to their particular settings or service systems. Policy case studies point out that managers and policy makers habitually disregard pertinent research evidence on the grounds that inferences drawn from randomized control trials are too narrow and do not represent their circumstances (Davis and Howden-Chapman 1996).

The focus in research design has correspondingly shifted from efficacy and internal validity (Braslow et al. 2005) toward effectiveness. As a consequence, we have incorporated research designs that account for the contextual factors that influence a particular intervention in practice or “real-world” settings (Hohmann and Shear 2002). In addition, there has been great progress in identifying, critically appraising, and synthesizing the published evidence (Steinberg and Luce 2005).

More recently the emphasis has been on implementing small changes in how care is delivered by using local knowledge and in how care can be improved in real-life settings, rather than assessing whether these interventions are effective (Baker 2006). Recent federal initiatives from the Department of Health and Human Services highlight the importance of understanding the how, why, where, and who in the translation and implementation of evidence-based interventions (National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup 2001). Thus, the shift is toward identifying what are workable and pragmatic approaches to improve care. At the same time, those conducting evidence-based practice have begun to recognize the value of integrating patient views and understanding how they engage in decision making as a way to bridge research and practice (Institute of Medicine 2001). We have also started to acknowledge that successful translation of evidence-based health services requires evaluating the evidence of the impact of the services, resources necessary to provide them, context where services will be implemented, mechanisms for change in the organization, and preferences of consumers relating to acceptance of barriers to care (Kitson, Harvey, and McCormack 1998).

However, the progress, while notable, is not enough. We need to move to a new frontier, one focusing on knowledge of implementation and facilitation, where the spotlight is not only on the nature of the evidence but on the context of uptake and on how to facilitate uptake in that context. For example, when we start thinking about to whom research knowledge should be transferred, we also have to consider that knowledge transfer must be fine-tuned to the types of decisions that providers, payers, and consumers face and the types of contexts in which they live and work. But many times, this information is not available. We do not know whom to target and the constraints under which they live.

Health services researchers may need to expand their roles if their research is to be taken to implementation stages. Shonkoff (2000) suggests that a credible messenger may be essential to successful knowledge-transfer around interventions. Becoming a credible messenger can be time-consuming and skill-intensive, with many who produce the knowledge/evidence being ill-suited or not interested in being credible messengers. Additionally, there is evidence that a message embodying ideas rather than evidence-based data may be more influential for decision making in health care policy (Lavis et al. 2003). Ignoring the serious barriers to evidence use (e.g., time pressures, perceived threats to autonomy, the preference for “colloquial” knowledge based on individual experiences, difficulty in accessing the evidence base, difficulty differentiating useful and accurate evidence from that which is inaccurate or inapplicable, and lack of resources) may only serve to convince users of the information that research evidence does not work for them. Moreover, the changes required to translate and implement evidence-based care demand restructuring the usual routine of daily work so that there is a smooth transition—it requires letting go of old and competing demands to enable the adoption of the new way of providing care (Torrey et al. 2001). And more importantly, something that seems to be routinely disregarded in the translation and implementation of evidence is that the new evidence must ring true with the values and experience of providers, patients, and policy makers (Torrey et al. 2001).

Another critical element for successful knowledge implementation is engagement with the audience, broadly defined. That means we have to engage with policy makers, we have to engage with communities, and we have to engage with healthcare providers if we truly want to disseminate the research evidence. Effectively implemented interventions are those where there is repeated interaction between the clinician and an expert who has been trained in the principles of, for example, academic detailing, or frequent interaction between the clinician and someone to whom he or she routinely turns for guidance (Soumerai and Avorn 1990; Lomas et al. 1991). Making this transition to implementing the evidence goes beyond merely having the information; it requires having a support person who will facilitate uptake and ensure that the translation and implementation of evidence remains a priority.

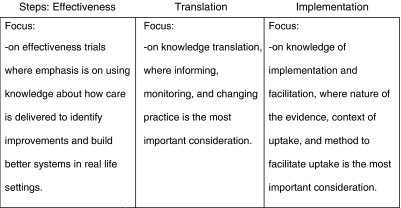

I hope that in the next 25 years we will approach this new frontier by focusing on the translation of findings so people can use them—where we not only study the decisions people make, but also the environments that constrain how they make use of research evidence and what they choose to adopt (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Towards a New Frontier … Moving from Efficacy to Effectiveness, from Knowledge Translation to Knowledge of Implementation and Facilitation

When measuring outcomes of evidence transfer, more emphasis needs to be placed on how research knowledge is being used rather than whether it is being used (Peltz 1978; Weiss 1979). This involves being able to tease out which components of the evidence are useful, which ones can be ignored and disregarded, and which seem central to successful knowledge implementation. Despite limited evidence that research evidence has affected clinical practice, there are case studies suggesting that dissemination of research evidence is enhanced if researchers involve managers, consumers, and policy makers in the development of the framework and the design of the investigation (Jones and Wells 2007). Horton's work (2006), for example, suggests what it might take to understand and fix health care policy so it can work. Her ethnographic study of Latino mental health clinics in the northwestern United States shows that the new private sector measures of productivity take a toll on both the Latina clinicians, whose invisible work subsidizes the system, and on the particular categories of patients—the uninsured and immigrants with serious psychosocial issues. She took the time to understand what it means to be a productive clinician when working in the context of the requirements of the health care system (e.g., managed care, cost containment).

Having a policy maker read her work could open a window on how policy making can affect practice in real-world settings, to create solutions that would remediate these harmful consequences. For example, she found that high demand for system accountability and worker efficiency encouraged providers to take shortcuts by treating individuals as mass categories. In particular, she observed that, while clinicians attempted to buffer their patients from the impact of such reforms, they also resorted to means to increase their productivity such as by dropping repeated no-show patients and denying care to the uninsured (Horton 2006).

As we reflect on how to move from a science of recommendation to a science of implementation, we must consider the importance of engaging with communities and clinicians, how to become the “Randy Moss receiver” for public facilities, to be able to anticipate the negative consequences that our policies may have on our “uptakers.” And herein lies the importance of community and practical clinical trials. If we create an operational infrastructure to conduct implementation research within a community or a public clinic, we not only transport ourselves to the scenarios and understand the circumstances of a given community, but we actually conduct implementation research to make an impact in the next 25 years.

The expected and necessary changes that will impact and restructure health care will require research evidence to be used for significant policy and system change. With this research, serious attention will need to be devoted to the translation and implementation of knowledge. It is here where all of us, as the responsible generation of health services researchers, and all of the younger investigators in this area in particular, must make sure that we provide a science of implementation that is not only inspirational to practitioners but also pragmatic enough that it will result in “uptake.” In this way, we may be able to ensure that 25 years from now we are not reviewing the same old problems.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This work was supported by Grant # P60 MD002261 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD) and Grant # P50 MH073469 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

REFERENCES

- Baker G R. Strengthening the Contribution of Quality Improvement Research to Evidence Based Health Care. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2006;15(3):150–1. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braslow J T, Duan N, Starks S L, Polo A, Bromley E, Wells K B. Generalizability of Studies on Mental Health Treatment and Outcomes, 1981 to 1996. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(10):1261. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.10.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton K, Cohen J T, Neumann P J. When Is Evidence Sufficient? Health Affairs. 2005;24(1):93–101. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis P, Howden-Chapman P. Translating Research Findings into Health Policy. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;43(5):865–72. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan G R. Patients Rarely Use Online Ratings to Pick Physicians. [accessed on October 13, 2008]. [Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2008/06/23/bill0623.htm.

- Green L, Glasgow R. Evaluating the Relevance, Generalization, and Applicability of Research Issues in External Validation and Translation Methodology. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 2006;29(1):126–53. doi: 10.1177/0163278705284445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann A A, Shear K M. Community-Based Intervention Research: Coping with the ‘Noise’ of Real Life in Study Design. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):201–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton S. The Double Burden on Safety Net Providers: Placing Health Disparities in the Context of the Privatization of Health Care in the US. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;63(10):2702–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for Academic and Clinician Engagement in Community-Participatory Partnered Research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297(4):407–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner J, Rimer B, Emmons K. Introduction to the Special Section on Dissemination: Dissemination Research and Research Dissemination: How Can We Close the Gap? Health Psychology. 2005;24(5):443–6. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer L, Frank J, Di Ruggiero E, Dobbins M, Manuel D, Gully P, Mowat D. Fostering Evidence-Based Decision-Making in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005;96(3):I1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the Implementation of Evidence Based Practice: A Conceptual Framework. British Medical Journal. 1998;7(3):149–58. doi: 10.1136/qshc.7.3.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis J N, Robertson D, Woodside J M, McLeod C B, Abelson J. How Can Research Organizations More Effectively Transfer Research Knowledge to Decision Makers? Milbank Quarterly. 2003;81(2):221–48. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J, Enkin M, Anderson G M, Hannah W J, Vayda E, Singer J. Opinion Leaders vs Audit and Feedback to Implement Practice Guidelines. Delivery after Previous Cesarean Section. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;265(17):2202–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; An Investment in America's Future: Racial/Ethnic Diversity in Mental Health Research Careers. [Google Scholar]

- Peltz D C. Some Expanded Perspectives on Use of Social Science in Public Policy. In: Yinger J M, Cutler S J, editors. Major Social Issues: A Multidisciplinary View. New York: Free Press; 1978. pp. 346–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff J P. Science, Policy, and Practice: Three Cultures in Search of a Shared Mission. Child Development. 2000;71(1):181–7. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumerai S B, Avorn J. Principles of Educational Outreach (‘Academic Detailing’) to Improve Clinical Decision Making. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;263(4):549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg E P, Luce B R. Evidence Based? Caveat Emptor! Health Affairs. 2005;24(1):80–92. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey W C, Drake R E, Dixon L, Burns B J, Flynn L, Rush A J, Clark R E, Klatzker D. Implementing Evidence-Based Practices for Persons with Severe Mental Illnesses. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(1):45–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunis S R, Stryer D B, Clancy C M. Practical Clinical Trials Increasing the Value of Clinical Research for Decision Making in Clinical and Health Policy. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(12):1624–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss C H. The Many Meanings of Research Utilization. Public Administration Review. 1979;39(5):426–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zerhouni E. Translational and Clinical Science—Time for a New Vision. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(15):1621–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]