Abstract

Objective

To test the hypothesis that high community-level unemployment is associated with reduced use of preventive dental care services by a dentally insured population.

Data

The study uses monthly data on population dental visits and unemployment in the Seattle and Spokane areas from 1995 to 2004. Utilization data come from Washington Dental Services. Unemployment data were obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and Washington's Employment Security Department.

Study Design

The study uses a Box–Jenkins Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) method to measure the association between the variables over time. The approach controls for the effects of autocorrelation, seasonality, and confounding variables.

Findings

In the Seattle area, an unexpected 10,000 unit increase in the number of unemployed individuals is associated with a 1.24 percent decrease in preventive visits during the month (p=.0043). In the Spokane area, a similar increase in unemployment is associated with a 5.95 percent decrease in preventive visits (p=.0326). The findings persist when the independent variable is the number of initial unemployment insurance claims.

Conclusions

The analysis suggests that utilization of preventive dental care declines during periods of high community-level unemployment. Community-level unemployment may impede or distract populations from utilizing preventive dental services. The study's findings have implications for insurers, dentists, policy makers, and researchers.

Keywords: Oral health care, time series analysis, unemployment

Oral health is necessary for many functions: eating, nutrition, communication, disease prevention, appearance, and overall health. Marked advances have been made in the quality and level of oral health over the past 50 years. However, the benefits have not been shared by all Americans and considerable room for progress remains (Evans and Kleinman 2000). One critical element in the ongoing improvement of oral health is preventive care.

Preventive dental services are typically provided during a routine check-up.1 They represent a direct and low-cost route to improved oral health. Preventive services include prophylaxis, sealants, and fluoride treatments, as well as screenings for tooth decay, periodontal disease, orthodontic disorders, and oral cancer. Regular care also allows providers to stop oral diseases from occurring and to diagnose and treat developing problems (Doty and Weech-Maldonado 2003).

Preventive dental care is important from two standpoints. First, regular preventive services yield health-related benefits. Individuals with at least one periodic visit annually are significantly less likely to have plaque, gingivitis, and calculus than individuals with no visits (Lang, Ronis et al. 1995). Moreover, adults who accessed preventive dental services in the past year reduced their risk of tooth loss by 27 percent (Kressin, Boehmer et al. 2003).

Utilization of preventive services is also important financially. Most preventive dental services are inexpensive and cost-effective, representing a fraction of the cost of care for advanced conditions, such as endodontic therapy, fixed prosthodontics, or dental implants (Brown and Lazar 1998). Researchers have found that utilization of preventive dental care services leads to significant savings over time for children (Savage, Lee et al. 2004,Quinonez, Downs et al. 2005). Reflecting these savings, total health care costs in the United States have been increasing dramatically, but spending on oral health has increased only slightly (Brown, Wall et al. 2002,Brown and Manski 2004;,Heffler, Smith et al. 2004)

Despite the importance of preventive dental care, evidence suggests that utilization of preventive services is far from universal. Estimates using the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) indicate that only 32 percent of all Americans had visited the dentist for a preventive visit during the previous year (Goodman, Manski et al. 2005).

The important nature of preventive dental services raises questions about the factors that influence utilization patterns. Many studies have examined the association between individual-level economic, demographic, and socioeconomic factors and utilization. However, there may also be community-level forces that affect utilization. Some research on the effect of community-level factors appears in the literature (Davidson, Andersen, et al. 2004,Brown, Davidson, et al. 2004), yet this area is largely understudied. One community-level factor that may affect utilization is unemployment.2

Unemployment can affect utilization of preventive oral health care through the mechanisms presented in Table 1 (Catalano and Satariano 1998,Catalano, Satariano, and Ciemins 2003). Along the first dimension, unemployment can have direct or indirect effects. Direct effects act on unemployed individuals and indirect effects act on those who are not unemployed, but who are economically tied to the unemployed individual. Along the second dimension, unemployment can have impedance and distraction effects. The impedance mechanism assumes that unemployment creates obstacles to accessing care. The distraction mechanism predicts that in stressful times, such as in periods of high unemployment, those items that typically receive little attention will receive even less attention.

Table 1.

Mechanisms That Connect Unemployment to Preventive Oral Health Care Utilization

| Direct Effects: | Indirect Effects: | |

|---|---|---|

| Act Only on the Unemployed Individual | Act on Those Economically Connected to the Unemployed Individual | |

| Impedance mechanism | Cell I | Cell II |

| Individuals want to utilize preventive oral health care services, but are impeded from doing so. | Utilization of preventive oral health care services by unemployed individuals is impeded by unemployment through: (1) the loss of employer-sponsored dental insurance; and/or (2) the reduction of overall financial resources, making out-of-pocket care, transportation, and childcare too expensive. | Utilization of preventive oral health care services by those economically connected to an unemployed individual is impeded through: (1) the loss of employer-sponsored dental insurance from the unemployed individual; and/or (2) the reduction of overall financial resources, making out-of-pocket care, transportation, and childcare too expensive. |

| Distraction mechanism | Cell III | Cell IV |

| Individuals have access to preventive oral health care services, but are distracted from utilization of those services. | Individuals lack the time, energy, or attention to utilize preventive oral health care services due to their own unemployment. | Individuals lack the time, energy, or attention to utilize preventive oral health care services due to: (1) the demands of an unemployed spouse, partner, or friends; and/or (2) excess demands on those left working; and/or (3) concern about one's own possible pending unemployment. |

Adapted from Catalano et al. (2003).

In Cell I, the direct impedance mechanism predicts that unemployment affects utilization for unemployed individuals by creating barriers, preventing them from utilizing care they would otherwise have accessed. For example, unemployment may impede utilization through the loss of dental insurance. Unemployment may also pose barriers to care by reducing financial resources, limiting the ability to purchase care out-of-pocket or needs like transportation and childcare.

In Cell II, the indirect impedance mechanism predicts utilization may be curtailed for all family members by the loss of insurance and depleted resources, not simply the unemployed individual. The effects of unemployment may also extend to others who rely economically on the unemployed individual (Catalano et al. 2003).

Cells III and IV describe the distraction mechanism. This mechanism assumes individuals have a limited amount of time, energy, and attention for their daily activities. During stressful periods, the distraction mechanism predicts that the resources needed to cope with life's challenges leave too little time or energy for nonurgent activities (Catalano et al. 2003). Thus, routine check-ups that are received normally would be postponed or foregone altogether during periods of high unemployment. The distraction mechanism can be particularly acute for utilization of preventive care because of its seemingly discretionary nature.

It is important to note that the impact of the indirect distraction mechanism can extend to periods of high community-level unemployment when fears of anticipated unemployment for working individuals are high. In these times, individuals may become distracted because high community-level unemployment may be interpreted as a warning sign of pending unemployment (Catalano et al. 2003).

Some evidence suggests that the stress associated with economic downturns may affect utilization of preventive dental care. Levit and Lazenby (1991) observed a drop in dental expenditures between 1989 and 1990, speculating it reflected the period's recession. They theorized that dental services were sensitive to changes in the economy because concerns about economic outlook may delay discretionary purchases. Kuthy et al. (1996) argued that reduced utilization may be explained by dental care being “crowded out” by other concerns such as physical health, leaving too little time or energy to seek care. Other studies suggest that high-stress situations may make preventive dental care a lower priority (Carlos 1973,Okada and Wan 1979,Broder, Russell et al. 2002,Kelly, Binkley et al. 2005). Unemployment-related stress may also reduce utilization by rearranging short-and long-term priorities (Carlos 1973).

The objective of this study was to determine the effect of community-level unemployment on preventive dental care utilization by a dentally insured population in two metropolitan areas in Washington. The primary research question was: Does preventive oral health care utilization decline during periods of increased community-level unemployment? More specifically, the study asked whether the number of preventive dental care visits in the Seattle and Spokane metropolitan areas varied inversely with the unexpected number of unemployed individuals in those areas over time.3

DATA AND METHODS

Study Setting

The analysis examined the effect of community-level unemployment on preventive dental care utilization by dentally insured individuals in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett Primary Metropolitan Statistical Area (PMSA) and the Spokane Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). The Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA includes King and Snohomish Counties. The Spokane MSA is Spokane County.

Primary Independent Variable: Unemployed Individuals

The primary independent variable used to measure unemployment was the number of unemployed individuals. Monthly unemployment data were obtained for the 120 months beginning in January 1995. Unemployment statistics were acquired from the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2001), which uses the Current Population Survey to estimate the number of persons who “do not have a job, have actively looked for work in the prior 4 weeks, and are currently available for work.”

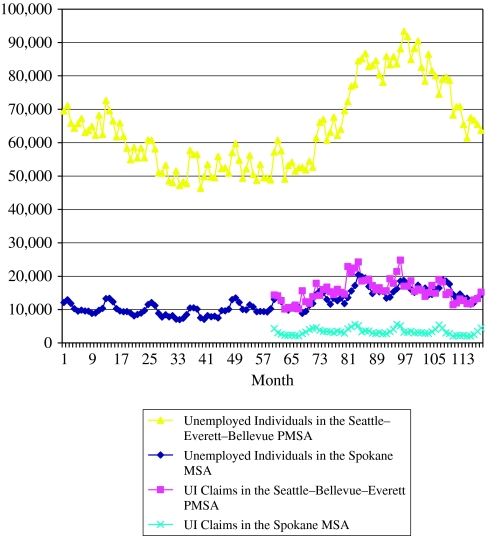

Over the 10-year period the monthly number of unemployed individuals in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA ranged from 46,354 (April 1998) to 93,333 (February 2003). Over the same period, the monthly number of unemployed individuals in the Spokane MSA ranged from 6,982 (October 1997) to 20,145 (January 2002). The data are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Unemployment in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett Primary Metropolitan Statistical Area (PMSA) and Spokane Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) for the 120 Months from January 1995 to December 2004.

Alternate Independent Variable: Initial Unemployment Insurance (UI) Claims

The fraction of the unemployed who recently lost their jobs is typically much smaller than the total number of unemployed. The analysis was thus repeated with an alternative independent variable that measures “disemployment.” This variable was the number of monthly initial UI claims, which measures the number of persons who had jobs covered by unemployment compensation coverage but lost their job, though no fault of their own. The disemployed are a subset of the unemployed and temporal variation in the number of initial UI claims may be a purer gauge of the demand for labor. Because UI claims correspond to only those individual who are new applicants, they better measure recent unemployment and may elicit different effects than total unemployment.

Monthly data on the number of initial UI claims were obtained for the 60 months between January 2000 and December 2004. Data were unavailable for the full 10-year period in the primary analysis. UI data came from Washington's Employment Security Department.4 The department creates monthly estimates from aggregated weekly UI data to measure the new claims for UI. The data are unofficial, but they are useful as a general measure of UI claiming data.

Over the 5-year period the monthly number of initial UI claims in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA varied from 10,129 (April 2000) to 24,821 (January 2002). The mean monthly number of initial UI claims in the Spokane MSA ranged from 2,015 (April 2004) to 5,607 (December 2002). The data are presented in Figure 1.

Dependent Variable: Preventive Oral Health Care Utilization

The dependent variable was preventive dental care utilization, measured by the number of monthly preventive visits in each community. Utilization data were provided by Washington Dental Service's (WDS) Dental Data and Analysis Center. WDS is Washington's Delta Dental affiliate. WDS is the largest dental insurer in the state and covered approximately one-third of the state's roughly 6 million residents at the end of 2004. WDS insurance packages are offered only through the group market. Enrollment increased across the study period, growing to nearly 985,000 in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA and approximately 195,000 in the Spokane MSA by 2004.5

The data set consists of aggregate monthly utilization data by enrollees of the WDS fee-for-service and preferred provider organization plans over the period. Utilization data for enrollees in the WDS health maintenance organization (HMO) product were not included in the data. However, HMO enrollment made up <1 percent of total enrollment over the period.

The WDS data include the number of total visits and the number of preventive visits over the 10-year period. Preventive visits were identified from claims from area providers that included service codes between 1000 and 1999. These codes represent a combination of WDS proprietary codes and those in the American Dental Association's Current Dental Terminology-2005. The codes cover cleanings, oral exams, fluoride treatments, and sealants. Preventive visits were defined as any visit that included one or more of these preventive codes.

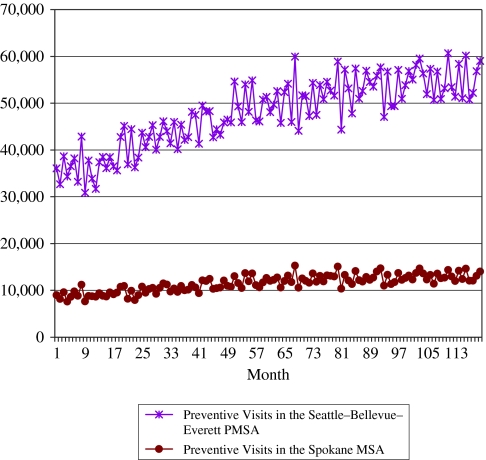

The key dependent variable in the analysis was the number of preventive oral health care visits in the month. The monthly number of preventive visits in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA ranged from 30,873 (September 1995) and 60,664 (March 2004). Monthly preventive oral health care visits in the Spokane MSA ranged from 7,607 (April 1995) to 15,313 (August 2000). The time series is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Preventive Oral Health Care Visits in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett Primary Metropolitan Statistical Area (PMSA) and Spokane Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) for the 120 Months from January 1995 to December 2004.

Other Covariates

Three covariates were used in the analysis. First, to control for changes in secular utilization trends, the number of monthly nonpreventive visits was included. This variable allows the analysis to proceed with confidence that any change in preventive utilization does not simply reflect general utilization trends. The number of monthly nonpreventive oral health care visits was defined as the difference between the total number of monthly visits and the number of preventive visits. Nonpreventive visits include the full range of restorative and emergency care.

A second covariate used in the analysis was monthly change in the size of the provider network in the two areas. These measures were included because utilization of preventive care is at least partly dependent on the availability of dental providers.

A third covariate included in the analysis was the average daily maximum temperature for the month. These data were included because inclement weather is one factor that could deter utilization. Previous research has demonstrated that ambient temperature has significant effects on help seeking for somatic and psychosomatic illnesses (Hartig, Catalano, et al. 2007). The inclusion of the weather data allows the analysis to control for months when the weather is particularly extreme.

One variable that was not included in the analysis was the size of the enrolled population. These data were unavailable for the first 2 years of the time series. Additionally, the enrollment data were highly collinear with the size of the provider networks over time, as the two series trended upward over the 120-month period.

Study Design

This project used a quasiexperimental time series methodology to estimate the association between measures of unemployment and the population's preventive dental visits over time. This approach is effective at determining an association between two variables only to the extent that it can rule out other “rival hypotheses” for the observed correlation. The methods described below borrow heavily from a similar design used by Catalano and Serxner (1987).

Time series models need to account for the so-called “third variables,” which could affect the two variables of interest and cause their observed correlation. Failure to control for these confounding or omitted variables can lead to spurious correlations and give credence to rival hypotheses. Third variables have three characteristics:

Accessibility—whether the third variable is measurable. Inaccessible third variables include those that are impossible to measure, unavailable, or unknown to the researcher (Catalano and Serxner 1987).

Regularity—how predictable the third variable is over time. The regular behavior of the third variable can follow linear trends or seasonal patterns over time, leading to spurious conclusions (Catalano 1981, p. 671).

Latitude—the unique characteristics of the sample community in the analysis, particularly those that set them apart from other communities in the analysis (Catalano and Serxner 1987).

A multistep approach was used to account for the effect of third variables. First, the effects of accessible third variables were measured by including them in the regression. In this study, the accessible third variables were the three covariates mentioned above.

Second, inaccessible and regularly occurring third variables were controlled for by including the regular behavior of the dependent variable in the equation. In practice, this meant including the expected level of the dependent variable in the right-hand side of the equation. This expected level is extrapolated from measurements of the dependent variable in previous periods. This process is described below. The approach accounted for the impact of any of the economic, demographic, and socioeconomic factors that have been found to affect utilization, but for which monthly data were unavailable. This technique also accounted for any regularly occurring patterns in utilization.

Next, to capture third variables that are inaccessible and irregular, the model included the dependent variable from a comparison community. The ideal comparison community shares as many of characteristics with the test community as possible, while still having an independent economy. Inclusion of the dependent variable for the comparison community allowed the model to control for any statewide regulatory or policy changes that may affect the dependent variable. In this study, the Spokane MSA served as the comparison community for the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA and vice versa.

Finally, to control for the inaccessible, irregular, and locally occurring third variables, the analysis was repeated in a second community. The second test helped to confirm that the findings in the first test were not the product of unmeasured local factors (Catalano and Serxner 1987).

Data Analysis

With these analytical tools in mind, the general model was set up, as follows:

| (1) |

where YTt is the number of monthly preventive dental care visits in the test community in month t; XT1t is the unexpected unemployment in the test community in month t; XT2t is the predicted value of the YT variable for month t, based on the history of YT over the preceding months; YCt is the number of monthly preventive visits in the comparison community in month t; XT4t+…+XTnt are any specified exogenous accessible third variables in the test community for month t; and e Tt is the error term for month t.

The variables XT1t and XT2t were generated through an iterative process to decompose the time series into expected and unexpected components by identifying patterns in the data (Catalano and Bruckner 2005). The Box–Jenkins approach involved Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) modeling, which allows a number of different iterative models to fit the data over time (Catalano and Satariano 1998). The technique accounts for trends and seasonality in the data and permits the model to construct the best estimate of these variables given historical data (McCleary and Hay 1980). This approach avoids the pitfall of drawing spurious conclusions about the relationship between two variables if one fails to recognize trends and patterns in the time series (Catalano et al. 2002).

The general model in the construction of XT1t and XT2t was

| (2) |

where Zt is the value of the modeled series at time t; μ is the mean of the series; θ is the moving average parameter; φ is the autoregressive parameter; at are the values that cannot be predicted from the history of the series; and Bn is the value of the series at time t−n.

It is important to note that this analytical technique is explicitly conservative. The test is designed to avoid a Type I error (which in this case would mean supporting an incorrect hypothesis). This research design controls for any variance in the dependent variable that is shared with autocorrelation, as well as utilization in the comparison community. As a result, the findings may underestimate the total impact of unemployment on utilization.

RESULTS

The first set of analyses used the number of unemployed individuals as the explanatory variable. The best-fitting model for the number of unemployed individuals in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA was

| (3) |

The time series was differenced to account for trending in the number of unemployed individuals over time. The best-fitting model of unemployment in the current month included autoregressive parameters at 1 and 12 months.

The results are presented in Table 2. The natural log of all measures of utilization was taken to account for outliers in the data. In column (1), the impact of an increase in the number of unexpected unemployed individuals each month has a statistically significant effect in the immediate month, as well as at one lag. An unexpected 10,000 unit increase in the number of unemployed individuals each month decreased the number of preventive oral health care visits by 1.24 percent (p<.01) in the current month and 0.80 percent in the following month (p<.10). There was no statistically significant lagged effect in the other months.

Table 2.

Coefficients for Predictors of the Natural Log of Preventive Oral Health Care Visits in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA and Spokane MSA for the 120 Months Starting January 1995

| (1) | (2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA | Spokane MSA | ||

| Predicted Value of Ln(dependent variable) | Predicted Value of Ln(dependent variable) | ||

| Moving average at lag 6 | −0.4526*** | Moving average at lag 8 | −0.0942 |

| (0.1251) | (0.1145) | ||

| Autoregression at lag 1 | 0.3363*** | Autoregression at lag 12 | 0.7969*** |

| (0.1057) | (0.0609) | ||

| Autoregression at lag 12 | 0.8843*** | ||

| (0.0516) | |||

| Ln(nonpreventive visits) | 0.7560*** | Ln(nonpreventive visits) | 0.5651*** |

| (0.0386) | (0.0850) | ||

| Ln(preventive visits in comparison community†) | 0.2684*** | Ln(preventive visits in comparison community†) | 0.3696*** |

| (0.0455) | (0.0753) | ||

| Providers in network‡ | −0.278E−05 | Providers in network‡ | 0.0003 |

| (0.491E−04) | (0.0010) | ||

| Average daily temperature | −0.0008 | Average daily temperature | 0.6102E-04 |

| (0.0005) | (0.0005) | ||

| Unemployed individuals (10,000s) | −0.0124*** | Unemployed individuals (10,000s) | 0.0090 |

| (0.0043) | (0.0324) | ||

| Lag 1 | −0.0080* | Lag 1 | 0.0292 |

| (0.0045) | (0.0334) | ||

| Lag 2 | −0.0068 | Lag 2 | 0.0457 |

| (0.0047) | (0.0323) | ||

| Lag 3 | −0.0057 | Lag 3 | −0.0066 |

| (0.0046) | (0.0322) | ||

| Lag 4 | 0.0011 | Lag 4 | −0.0595* |

| (0.0043) | (0.0326) | ||

Numbers in parentheses are standard errors.

p<.10, two-tailed test,

p<.05, two-tailed test,

p<.01, two-tailed test.

Comparison community for the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA is the Spokane MSA and vice versa.

Provider network data were differenced to account for the strong upward trend over time.

MSA, Metropolitan Statistical Area; PMSA, Primary Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The analysis was then repeated, using the Spokane MSA as the test community. The best-fitting model for the number of unemployed individuals in the Spokane MSA was

| (4) |

The Spokane model was more complicated than the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett model. The time series required de-trending (by differencing at 1 month) and de-seasonalizing (by differencing at 12 months). After de-trending and de-seasonalizing the time series, the best-fitting model included moving average parameters at 6 and 12 months.

The results from the analysis are presented in column (2) of Table 2. Natural logs were also taken to account for outliers. The impact of an increase in the number of unexpected unemployed individuals each month had a statistically significant effect at a 4-month lag. This effect suggests that an unexpected 10,000 unit increase in the number of unemployed individuals decreased the number of preventive oral health care visits by 5.95 percent (p<.10) 4 months in the future. There was no statistically significant effect in the other months.

Traditional measures of goodness-of-fit are not particularly helpful with time series approaches. These methods can create artificially high R 2 statistics because removing trend alone accounts for much of the original variance in a variable exhibiting secular trends. This analysis used another approach to estimate goodness-of-fit. Under this technique, the dependent variable was regressed on the values predicted for it by a Box–Jenkins model. Next, the residuals of the first regression were regressed on the model's control variables. Finally, the unemployment variable was added to this second equation. By comparing R 2 across the last two regressions, the contribution of the unemployment data in explaining the variance of the utilization can be estimated.

In the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA, the R 2 in the first step regression was 0.090. After the unemployment data were included, the R 2 increased to 0.136. In the Spokane MSA regressions, the R 2 increased from 0.001 to 0.111. In both cases, the findings suggest that the unemployment data considerably improved the model's ability to explain the variance in utilization.

In order to confirm that the findings in Table 2 were not an artifact of the explanatory variable, the analysis was repeated using the number of initial UI claims each month for the measure of unemployment. The first set of regressions measure the association between monthly UI claims and preventive dental care utilization in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA. The best-fitting model for the number of initial UI claims in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA was

| (5) |

The model included moving average parameters at 1 and 12 months, as well as an autoregressive parameter at 1 month.

The results from the analysis are presented in column (1) of Table 3. The natural log of all measures of monthly oral health care utilization was taken to account for outliers. The impact of an increase in the number of unexpected unemployed individuals each month had a statistically significant effect in the immediate month, as well as at one lag. An unexpected 10,000 unit increase in the number of initial UI claims each month decreased the monthly number of preventive oral health care visits by 1.9 percent (p<.01) in the following month and by 2.2 percent in the next month (p<.01). There was no statistically significant effect in the immediate month, nor any lagged effect in the third or fourth months.

Table 3.

Coefficients for Predictors of the Natural Log of Preventive Oral Health Care Visits in the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA and Spokane MSA for the 60 Months Starting January 2000

| (1) | (2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA | Spokane MSA | ||

| Predicted Value of Ln(dependent variable) | Predicted Value of Ln(dependent variable) | ||

| Moving average at lag 1 | −0.2965* | Autoregression at lag 10 | −0.4310* |

| (0.1323) | (0.2220) | ||

| Moving average at lag 12 | −0.6331*** | Autoregression at lag 12 | 0.5673*** |

| (0.1312) | (0.1070) | ||

| Ln(nonpreventive visits) | 0.4940*** | Ln(nonpreventive visits) | −0.0055 |

| (0.0417) | (0.1203) | ||

| Ln(preventive visits in comparison community†) | 0.5782*** | Ln(preventive visits in comparison community†) | 0.8722*** |

| (0.0495) | (0.1055) | ||

| Providers in network‡ | −0.0002 | Providers in network‡ | 0.0012 |

| (0.0005) | (0.0023) | ||

| Average daily temperature | −0.0007* | Average daily temperature | 0.0001 |

| (0.0004) | (0.0004) | ||

| Initial unemployment insurance claims (10,000s) | −0.0114 | Initial unemployment insurance claims (10,000s) | −0.2724*** |

| (0.0079) | (0.1070) | ||

| Lag 1 | −0.0193** | Lag 1 | −0.1509* |

| (0.0087) | (0.0874) | ||

| Lag 2 | −0.0222*** | Lag 2 | −0.1419* |

| (0.0084) | (0.0784) | ||

| Lag 3 | −0.0096 | Lag 3 | 0.0740 |

| (0.0093) | (0.0834) | ||

| Lag 4 | −0.0015 | Lag 4 | −0.2033*** |

| (0.0076) | (0.0807) | ||

Numbers in parentheses are standard errors.

p<.10, two-tailed test,

p<.05, two-tailed test,

p<.01, two-tailed test.

Comparison community for the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA is the Spokane MSA and vice versa.

Provider network data were differenced to account for the strong upward trend over time.

MSA, Metropolitan Statistical Area; PMSA, Primary Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The analysis was repeated again, using the Spokane MSA as the test community. The best-fitting model for the number of initial UI claims in the Spokane MSA was

| (6) |

The Spokane model was more complicated than the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett model. The time series required de-trending (by differencing at 1 month) and de-seasonalizing (by differencing at 12 months). After de-trending and de-seasonalizing the time series, the model suggested that the best-fitting model included moving average parameters at 1 and 12 months.

The results from the analysis are presented in column (2) of Table 3. The natural log of all measures of utilization was taken again. This results suggests that an unexpected 10,000 unit increase in the number of monthly initial UI claims decreased the number of preventive oral health care visits by 27.2 percent (p<.01) in the immediate month, 15.1 percent in the first lag (p<.10), 14.2 percent in the second lag (p<.10), and 20.3 percent 4 months in the future (p<.01). There was no significant effect in third month.

As described above, traditional measures of goodness-of-fit are not particularly helpful with time series approaches. The method described above was used again to gauge the improvement in goodness-of-fit after adding the data UI claims. In the Seattle–Bellevue–Everett PMSA, the R 2 in the first step regression was 0.370, which increased to 0.371 in the second step. In the Spokane MSA regressions, the R 2 rose from <0.001 to 0.288. In both cases, these findings suggest that the UI data improve the ability of the model to explain the variance of utilization.

DISCUSSION

The results in Tables 2 and 3 provide support for the hypothesis that preventive oral health care utilization declines during periods of unexpectedly high community-level unemployment. A statistically significant, negative relationship between community-level unemployment and the population's preventive oral health care utilization was found using different measures of unemployment across two communities. The finding is particularly notable, because it occurs within a dentally insured population.

With the exception of the results in the Spokane MSA using initial UI claims, the findings are relatively small in magnitude. Yet the magnitude should be kept in perspective. The utilization data in this study come from an insured population. It is reasonable to expect that the effect on the total population (including those without dental insurance) would be much larger. Further, the analytic method is a conservative test used to avoid a Type I error, which may underestimate the total impact of community-level unemployment.

One explanation for the much larger effects in the UI test on the Spokane MSA is that the two measures of unemployment capture different effects. That is, the difference between “unemployment” and “disemployment” appears to be important in the Spokane MSA, with initial UI claims a stronger driver of the impedance and distraction effects. The findings suggest that the number of initial UI claims may do a better job of measuring the real or anticipated unemployment among the population in Spokane.

Practice and Policy Implications

The findings from this study have several important implications. First, for administrators of oral health care systems, it is important to understand the determinants of preventive dental care utilization, particularly because it represents a lower-cost alternative to restorative or emergency care. If administrators want to promote preventive oral health care utilization, they may want to take action at times of high unemployment.

Second, an appreciation for the effects that economic downturns have on utilization is important for dentists wanting to maintain financially successful practices. If dentists can expect to see proportionally fewer patients for preventive services during times of high unemployment, they may wish to adjust staffing patterns, prices, or operating expenses. Similarly, it is possible that providers may face future increases in demand for restorative and emergency services that result from decreased demand for preventive care in the current period. More research is needed to examine the link between short-term changes in preventive services and their effect on the demand for restorative and emergency services.

Third, the findings suggest that policy makers may want to encourage preventive care utilization during times of high unemployment. Outreach efforts may be particularly important during economic downturns. The results from this study also suggest the importance of policies to eliminate secondary barriers to accessing care, such as childcare and transportation.

Fourth, if a significant negative relationship between community-level unemployment and aggregate preventive dental care utilization was found in an insured population, it is reasonable to expect that the effects are greater for the dentally uninsured. This may mean policy makers should broaden coverage of dental benefits in programs like Medicaid.

Finally, for researchers, this study provides insight into factors related to utilization of other essential health care services. The role of community-level factors, including unemployment, is often ignored. The importance of this study may extend beyond dental care to a much wider array of preventive health services and care for chronic illnesses.

Limitations

Some limitations provide an opportunity for future research to better identify the impact of community-level unemployment on utilization of preventive dental services. First, the analysis does not include data on the utilization patterns of the dentally uninsured. This may underestimate the total effect of unemployment on utilization. Second, the data included information only on total visits and preventive visits. Both restorative and emergency visits are combined into “nonpreventive” visits. It is possible that restorative and emergency visits behave differently. Future studies may benefit from analyzing them distinctly. Third, the data did not contain individual-level information on enrollees or practices. A future study would benefit from these data in addition to community-level data when analyzing the effects of unemployment. Nor did it include information on benefit packages offered by WDS, which could be important in explaining utilization patterns. Finally, the findings may not be generalizable to other insurance plans or other geographic areas.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgement/Disclosure Statement: No financial support was received for this project. The authors would like to acknowledge the helpful suggestions of the two anonymous reviewers. The authors are grateful for helpful comments on earlier versions of this project from Helen Halpin, Jane Weintraub, and William Satariano.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

NOTES

For the purposes of this analysis, “preventive oral health care” refers to “secondary” preventive care, the services professionally administered at the provider level during a patient's routine check-up. In contrast, “primary” preventive care includes fluoridation of drinking water, use of fluoridated toothpaste, and regular brushing and flossing by individuals. “Tertiary” prevention includes treatment of early stage oral health problems after they have already occurred, such as the replacement of missing teeth and periodontal therapy (Freudenheim 1994).

It is important to note that in order for community-level unemployment to have a significant impact on preventive oral health care utilization, it must have an effect above and beyond the aggregation of individual-level unemployment in the community. That is, high unemployment must be negatively affecting individuals who are not actually unemployed themselves.

The term “unexpected” is used throughout the paper to describe the portion of unemployment that cannot be explained by trends, patterns, or seasonality in the data.

Data are available at http://www.wilma.org/occinfo/main.asp. The web site reports that the UI data “do not represent official unemployment claimant numbers reported to the Federal government (but) they are taken from the same reporting database as all other UI numbers.”

According to a 1997 report in MMWR approximately 41 percent of Washingtonians lacked dental insurance in the first year of the study (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1997. “Dental Service Use and Dental Insurance Coverage—United States, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1995.”MMWR 46(50):1199–203.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- Broder H L, Russell S, Catapano P, Reisine S. Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Dental Treatment among Female Caregivers of Children with and without HIV and Their Health Care Providers. Pediatric Dentistry. 2002;24(4):301–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E, Manski R. Dental Services: Use, Expenses, and Sources of Payment, 1996–2000. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brown E R, Davidson P L, et al. Effects of Community Factors on Access to Ambulatory Care for Lower-Income Adults in Large Urban Communities. Inquiry. 2004;41:39–56. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_41.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L J, Lazar V. Dental Procedure Fees 1975 through 1995: How Much Have They Changed? Journal of the American Dental Association. 1998;129:1291–4. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L J, Wall T P, et al. The Funding of Dental Services among U.S. Adults Aged 18 Years and Older: Recent Trends in Expenditures and Sources of Funding. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2002;133(5):627–35. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos J P. Prevention and Oral Health. Washington, DC: Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano R. Contending with Rival Hypotheses in Correlation of Aggregate Time-Series (CATS): An Overview for Community Psychologists. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1981;9(6):667–79. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano R A, Bruckner T. Economic Antecedents of the Swedish Sex Ratio. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;60(3):537–43. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano R A, Satariano W A. Unemployment and the Likelihood of Detecting Early-Stage Breast Cancer. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(4):586–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.4.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano R A, Satariano W A, Ciemins E L. Unemployment and the Detection of Early Stage Breast Tumors among African Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites. Annals of Epidemiology. 2003;13(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(02)00273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano R A, Serxner S. Time Series Designs of Potential Interest to Epidemiologists. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1987;126:724–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson P L, Andersen R M, et al. A Framework for Evaluating Safety-Net and Other Community-Level Factors on Access for Low-Income Populations. Inquiry. 2004;41:21–38. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_41.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty H E, Weech-Maldonado R. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Adult Preventive Dental Care Use. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2003;14(4):516–34. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C A, Kleinman D V. The Surgeon General's Report on America's Oral Health: Opportunities for the Dental Profession. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2000;131(12):1721–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenheim E. Healthspeak: A Complete Dictionary of America's Health Care System. New York: Facts on File; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman H, Manski M, et al. An Analysis of Preventive Dental Visits by Provider Type, 1996. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2005;136:221–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig T, Catalano R, et al. Cold Summer Weather, Constrained Restoration, and the Use of Antidepressants in Sweden. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2007;27:107–16. [Google Scholar]

- Heffler S, Smith S, et al. Health Spending Projections through 2013. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2004;W4:79–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S, Binkley C, et al. Barriers to Care-Seeking for Children's Oral Health among Low-Income Caregivers. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(8):1345–51. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.045286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kressin N R, Boehmer U, et al. Increased Preventive Practices Lead to Greater Tooth Retention. Journal of Dental Research. 2003;82(3):223–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuthy R A, Strayer M S, et al. Determinants of Dental User Groups among an Elderly, Low-Income Population. Health Services Research. 1996;30(6):809–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang W P, Ronis D L, et al. Preventive Behaviors as Correlates of Periodontal Health Status. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 1995;55(1):10–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1995.tb02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levit K R, Lazenby H C. National Health Expenditures. Health Care Financing Review. 1991;13(1):29–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleary R, Hay R. Applied Time Series Analysis for the Social Sciences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Okada L M, Wan T T. Factors Associated with Increased Dental Care Utilization in Five Urban, Low-Income Areas. American Journal of Public Health. 1979;69(10):1001–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.69.10.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinonez R B, Downs S M, et al. Assessing Cost-Effectiveness of Sealant Placement in Children. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 2005;65(2):82–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2005.tb02791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage M F, Lee J Y, et al. Early Preventive Dental Visits: Effects on Subsequent Utilization and Costs. Pediatrics. 2004;114:418–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0469-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. How the Government Measures Unemployment. [accessed on March 18, 2007]. Available at http://www.bls.gov/cps/cps_htgm.htm.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.