Abstract

The aim of this study is to evaluate the usefulness of heart rate recovery (HRRec) for assessing risk of death in heart failure (HF) patients. Echocardiographic and clinical exercise data were analyzed retrospectively on 712 HF patients (EF ≤ 45%). HRRec was calculated as peak exercise heart rate – heart rate at 1 min of active recovery. Patients were followed for all-cause mortality (5.9 ± 3.3 years follow-up). Groups were identified according to HRRec: group-1 (HRR ≤ 4 bpm), group-2 (5 ≤ HRR ≤ 9 bpm), and group-3 (HRR ≥ 10). Kaplan–Meier analysis estimated survival of 91, 64, and 43% (group-1); 94, 76, and 63% (group-2); and 92, 82, and 70% (group-3) at 1, 5, and 10 years, respectively. Ranked HRRec independently predicted mortality after adjusting for age, gender, NYHA class, LVEF and BMI, but was not independent of exercise time, peak VO2 and VE/VCO2 at nadir. HRRec is a useful prognostic marker in patients with HF, particularly when gas exchange measures are not available.

Keywords: Clinical exercise testing, Oxygen consumption, Dyspnea, Fatigue

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a clinical syndrome characterized by compromised cardiac function, high left ventricular filling pressures, and symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue that are most pronounced during periods of activity. Despite recent advances in the management of patients with HF, morbidity and mortality remain high and the prevalence is continuing to increase as the population ages (McMurray and Stewart 2000). Reliable prognostic indicators help to classify the patients at the highest risk and identify those in need of more aggressive management. Baseline measures of cardiac function provide only limited prognostic value and are poorly correlated with critical measures of functional capacity. In addition, since HF becomes a systemic illness influencing multiple physiologic systems (e.g., pulmonary, vasculature, and locomotor muscle), quantifying measures of these systems during clinical exercise testing provides important insight into pathophysiology of these systems.

A number of variables measured during clinical exercise testing have shown to be of prognostic value in HF patients. These include measures of exercise tolerance, expressed as exercise time on a given protocol or peak oxygen consumption (VO2 peak) (Cicoira et al. 2004; Francis et al. 2000; Hirsh et al. 2006; Mancini et al. 1991; Myers et al. 2000), oxygen consumption at anaerobic threshold (VO2 AT) (Gitt et al. 2002), 6-minute walk-test time (Guyatt et al. 1985; Rostagno et al. 2003), ventilatory efficiency (expressed by oxygen uptake efficiency slope or the slope of ventilation relative to carbon dioxide production, VE/VCO2) (Arena et al. 2004; Davies et al. 2006; Francis et al. 2000; Gitt et al. 2002; Hollenberg and Tager 2000) as well as a measure of autonomic function, such as an assessment of heart rate variability (Kruger et al. 2002; Wijbenga et al. 1998). Each of these measures has been shown to independently and variably correlate with mortality and morbidity.

The measure of HRRec after exercise is considered to be a function of vagal reactivation and a blunted heart rate recovery (HRRec) after exercise testing has been shown to predict all cause mortality in the general population (Cole et al. 1999). Interestingly, however, initial studies routinely excluded HF patients (Arai et al. 1989; Rosenwinkel et al. 2001). Patients with HF have known abnormalities of the autonomic nervous system, typified by increased sympathetic activity, decreased vagal tone and depressed baroreceptor responsiveness (Ferguson et al. 1992; Francis et al. 1990). However, there may be slight differences in the autonomic profiles among the patients with different HF etiologies, which might influence the HRRec in these subgroups (Malfatto et al. 2001). Recently, smaller studies have examined HRRec in HF patients and found that this measure is associated with functional class and linked to mortality. In addition, work in our laboratory suggests differences in the neurohumoral profile in HF patients as a function of post-exercise HRRec (Wolk et al. 2006).

It remains unclear, however, the degree to which HRRec adds to the prediction of prognosis in HF patients over more traditional measures obtained at rest or during an exercise test. It has been suggested that HRRec may only be useful to assess prognosis when used in conjunction with more traditional measures, such as peak VO2 (Hirsh et al. 2006). Thus, the focus of the present study was to evaluate the predictive value of HRRec in a large, well characterized HF population, and compare the prognostic strength of HRRec with other factors commonly considered to be important prognostic indicators in HF patients.

Methods

Participant characteristics

Retrospective data were obtained on 712 HF patients with a history of ischemic or dilated cardiomyopathy and left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) ≤45%. Co-morbidities including smoking history, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease (without previous myocardial infarction), and prior myocardial infarction were also identified. Data were collected from clinical echocardiographic studies as well as from cardiopulmonary exercise tests between January 1994 and May 2003. Follow-up for mortality or transplant was obtained through the Mayo Clinical database and confirmed through the social security index (SSI) in April of 2006. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Mayo Clinic institutional review board.

The measure of HRRec was calculated as the difference between the peak heart rate during exercise and at 1-and 2-min into active recovery. Study patients were divided, a posteriori, into three groups according to their HRRec at 1 min: group-1 (HRRec ≤ 4 bpm), group-2 (5 ≤ HRRec ≤ 9 bpm), and group-3 (HRRec ≥ 10) as described in “Definition of heart rate recovery”. Patients were followed for all-cause mortality for 5.9 ± 3.3 years after exercise testing. The prognostic value of HRRec was assessed and compared to other selected variables.

Function measurements and protocol

All patients performed the same symptom-limited incremental treadmill test according to a standard protocol. The protocol consisted of an initial treadmill speed and grade of 2.0 mph and 0%, respectively. The speed and/or grade were subsequently adjusted every 2 min to yield an approximate 2-MET increase per stage of exercise. Participants were verbally encouraged to continue the exercise protocol to maximal exertion, which was confirmed by a rating of perceived exertion of ≥18 on the Borg 6–20 scale and a respiratory exchange ratio of ≥1.15. Gas exchange, HR and oxygen saturation were measured along with classical gas exchange measures (oxygen consumption, VO2; carbon dioxide production, VCO2; minute ventilation, VE; tidal volume VT; respiratory rate, fb; partial pressure of end-tidal O2 and CO2-PETO2 and PETCO2, along with a number of derived variables; e.g., VO2/HR; ventilatory efficiency, VE/Vco2) using a metabolic measurement system (MedGraphics CPX/D/Medical Graphics, St. Paul, MN). Participants wore electrodes for the electrocardiogram (heart rate and monitoring), a blood pressure cuff, and were fitted with a nose clip and standard mouthpiece attached to a PreVent Pneumotach (Medical Graphics, St. Paul, MN) throughout the testing procedure, including 3-min of recovery.

After the patients had achieved the peak workload, they were brought immediately to 1.7 mph and a 0% grade for an active recovery phase. This was maintained for 3-min after which they were seated for an additional 3-min of passive recovery.

Definition of heart rate recovery

Heart rate was captured beat-by-beat and averaged over the last 30 s of each stage of exercise to minimize artifact during the exercise testing. Post-exercise recovery HR was also captured beat-by-beat and averaged over 10 s to minimize artifact while maintaining the integrity of the 1-min and 2-min recovery time points. The HRRec was defined as the difference between heart rate at peak exercise and at 1- and 2-min into the recovery period. For the analyses, the HRRec at 1 min was used to classify patients into three groups with optimal cut off points at 4 and 9 bpm (group-1 = HRRec ≤ 4 bpm, group-2 = HRRec 5–9 bpm and group-3 = HRRec ≥ 10 bpm). To obtain these optimal cut off points, dummy variables were created for all cutoffs, (i.e., HRRec ≤ −2 to HRRec ≤ 22) and simultaneously entered into a prediction model, and after adjusting for age and gender, the backward selection method was used. To validate the cut off points, chi square values were compared from the model.

End points

The mean follow-up time was 5.9 ± 3.3 years. Initiation into the study was defined as the date on which the graded exercise test occurred. The primary end-point was defined as cardiac transplant and/or death from all causes, which was identified through the Mayo Clinic database and confirmed through the Social Security Index. The follow-up was completed in April 2006.

Statistical analysis

Group statistics were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. Categorical variables were summarized as percentages. Comparison between two groups was made using two sample t tests for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi square test for categorical variable. The Kruskal–Wallis test and F test were used to compare mean of multiple groups. Overall survival was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. A Univariate and Multivariate model to identify potential risk factors for these end points was assessed using the Cox proportional hazard model. Variables were selected in a backward selection manner with retention set at a significance level of 0.05. Results of these analyses were summarized as hazard ratios (HR) and associated log likelihood ratio χ2 and P values. To overcome the potential for poor distribution of HRRec with outliers in both directions, rank version of HRRec was computed for the multivariate analysis, assigning the best recovery with the highest rank.

Results

Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics for the entire cohort and groups, based on HRRec are provided in Table 1. Primary differences between the HRRec groups included group-1 having a slightly higher proportion of men and patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy compared to the other groups. Patients from this group were also more often classified as NYHA III–IV and the mortality in these groups was the highest (46 vs. 29% and 20% in group-1 vs. groups 2 and 3, respectively).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Entire cohort | HRRec ≤ 4 bpm | HRRec = 5–9 bpm | HRRec ≥ 10 bpm | P value for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 712 | 221 | 174 | 317 | <0.001 |

| Age | 56 ± 12 | 58 ± 11 | 59 ± 11 | 53 ± 13 | <0.001 |

| Male | 515 (72) | 175 (79) | 121 (70) | 129 (69) | 0.016 |

| BMI | 28.1 ± 5.6 | 28.4 ± 5.5 | 28.1 ± 5.5 | 27.9 ± 5.7 | 0.510 |

| NYHA class | <0.001 | ||||

| I | 117 (16) | 20 (9) | 31 (18) | 66 (21) | |

| II | 307 (43) | 14 (43) | 72 (41) | 141 (44) | |

| III | 218 (31) | 77 (35) | 55 (32) | 86 (27) | |

| IV | 70 (9) | 30 (14) | 16 (9) | 24 (7) | |

| LVEF (%) | 24.5 ± 8.8 | 23.3 ± 8.5 | 24.7 ± 8.7 | 25.3 ± 8.8 | 0.048 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 373 (52) | 106 (48) | 85 (49) | 182 (57) | 0.020 |

| Smoking history | 349 (49) | 118 (53) | 86 (49) | 145 (46) | 0.080 |

| Diabetes | 67 (9) | 25 (11) | 20 (11) | 22 (7) | 0.057 |

| Hypertension | 113 (16) | 34 (16) | 32 (18) | 47 (15) | 0.710 |

| Coronary artery disease | 171 (24) | 65 (28) | 46 (26) | 60 (19) | 0.002 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 92 (13) | 34 (15) | 24 (14) | 34 (11) | 0.095 |

| Medications | |||||

| ACE inhibitors | 558 (78) | 173 (78) | 142 (82) | 243 (77) | 0.230 |

| AII receptor blockers | 65 (9) | 19 (9) | 11 (6) | 35 (11) | 0.023 |

| β-Blockers | 227 (32) | 56 (25) | 61 (35) | 110 (35) | 0.530 |

| Digitalis | 522 (73) | 166 (75) | 123 (71) | 233 (74) | 0.710 |

| Diuretic | 548 (77) | 185 (84) | 127 (73) | 236 (74) | 0.030 |

| Statins | 140 (20) | 44 (20) | 35 (20) | 61 (19) | 0.820 |

| Died | 217 (30) | 102 (46) | 51 (29) | 64 (20) | <0.001 |

| Survived or transplanted | 489 (69) | 118 (53) | 123 (71) | 248 (78) | <0.001 |

Data are mean ± SD or count (percent) where appropriate

BMI Body mass index, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, ACE angiotensin converting enzyme, A-II angiotensin II

Physiologic characteristics measured during the graded exercise test are provided in Table 2. Patients in group-1 tended to have shorter exercise time, lower heart rate reserve, lower peak VO2 and a higher VE/VCO2 ratio. Conversely to group-1, group-3 had the longest exercise time and highest peak VO2, LVEF and heart rate reserve along with the lowest values of VE/VCO2 and lowest mortality compared to the other groups.

Table 2.

Physiologic measurements at rest and peak exercise

| Entire cohort | HRRec ≤ 4 bpm | HRRec 5–9 bpm | HRRec ≥ 10 bpm | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting values | |||||

| HR (bpm) | 83 ± 16 | 85 ± 18 | 82 ± 16 | 82 ± 16 | 0.11 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 109 ± 19 | 108 ± 21 | 110 ± 18 | 109 ± 17 | 0.31 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 71 ± 19 | 70 ± 30 | 71 ± 11 | 71 ± 12 | 0.07 |

| VE= VCO2 | 43.3 ± 7.9 | 44.5 ± 8.8 | 43.0 ± 7.4 | 42.7 ± 7.3 | 0.03 |

| PETCO2 (mmHg) | 34.2 ± 4.4 | 33.5 ± 4.2 | 34.9 ± 4.2 | 34.3 ± 4.5 | 0.004 |

| Peak exercise | |||||

| HR (bpm) | 136 ± 25 | 126 ± 25 | 133 ± 23 | 144 ± 23 | <0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 135 ± 32 | 129 ± 33 | 133 ± 31 | 141 ± 32 | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 69 ± 20 | 65 ± 23 | 70 ± 17 | 70 ± 19 | 0.04 |

| VE= VCO2 | 36.0 ± 9.3 | 39.5 ± 12.0 | 35.1 ± 7.2 | 34.0 ± 7.3 | <0.001 |

| PETCO2 (mmHg) | 34.7 ± 7.7 | 32.9 ± 6.7 | 35.1 ± 8.3 | 35.9 ± 7.9 | <0.001 |

| VO2 (ml/kg per minute) | 18.7 ± 5.8 | 16.3 ± 5.0 | 18.2 ± 5.4 | 20.5 ± 5.8 | <0.001 |

| Exercise time (min) | 6.5 ± 2.4 | 5.4 ± 2.0 | 6.3 ± 1.9 | 7.5 ± 2.6 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD

HR Heart rate, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, VE ventilation, VCO2 volume of carbon dioxide produced, PETCO2 partial pressure of end tidal CO2, VO2 volume of oxygen consumed

Determinants of HRRec

When exploring the relation between HRRec and other variables, it appeared that longer exercise time contributed to faster HRRec, whereas age, male gender and resting heart rate were associated with slower HRRec (Table 3). The influence of β-blocker and statin use on HRRec is presented in Tables 4 and 5. Unlike β-blockers, there was no significant influence of statins on HRRec.

Table 3.

Determinants of HRRec

| Parameter estimate | Pr > F | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.13 | 0.01 |

| Male | −2.49 | 0.04 |

| Exercise time | 0.98 | <0.001 |

| Resting HR | −0.08 | 0.01 |

HR Heart rate

Table 4.

Influence of beta blocker use on HRRec

| Beta blockers | No beta blockers | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting HR | 78 ± 15 | 85 ± 17 | <0.001 |

| Peak HR | 131 ± 24 | 138 ± 25 | 0.002 |

| HR reserve | 53 ± 22 | 53 ± 23 | 0.99 |

| HR1 | 120 ± 22 | 127 ± 24 | <0.001 |

| HR2 | 108 ± 19 | 115 ± 19 | <0.001 |

| HRRec1 | 11 ± 11 | 10 ± 13 | 0.05 |

| HRRec2 | 24 ± 15 | 24 ± 16 | 0.89 |

| Survivors | 79.74% | 63.51% | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or percent where appropriate

HR Heart rate, HR1 heart rate at first minute recovery, HR2 heart rate at second minute recovery, HRRec1 heart rate recovery at first minute recovery, HRRec2 heart rate recovery at second minute recovery

Table 5.

Effect of statins on HRRec

| Statins | No statins | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting HR | 81 ± 16 | 85 ± 17 | 0.03 |

| Peak HR | 136 ± 24 | 138 ± 24 | 0.45 |

| HR reserve | 55 ± 22 | 53 ± 23 | 0.41 |

| HR1 | 126 ± 23 | 128 ± 23 | 0.43 |

| HR2 | 110 ± 18 | 114 ± 19 | 0.11 |

| HRRec1 | 10 ± 11 | 11 ± 12 | 0.90 |

| HRRec2 | 26 ± 16 | 25 ± 15 | 0.83 |

| Survivors | 68.50% | 65.04% | 0.50 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or percent where appropriate

HR Heart rate, HR1 heart rate at first minute recovery, HR2 heart rate at second minute recovery, HRRec1 heart rate recovery at first minute recovery, HRRec2 heart rate recovery at second minute recovery

HRRec and mortality

Table 6 highlights the univariate predictors of mortality in this cohort of HF patients. Age, gender, NYHA class, LVEF, exercise time, heart rate reserve, peak HR, peak VO2, nadir of VE/VCO2, HRRec at 1 min, ischemic origin of HF and the use of beta-blockers were all predictive of mortality according to a univariate analysis. The highest hazard ratios were related to the nadir of VE/VCO2 > 34 (hazard ratio = 2.46, P < 0.0001), HRRec at 1 min ≤4 bpm (hazard ratio = 2.15, P < 0.0001) and peak VO2 < 14 ml/kg per minute (hazard ratio = 2.01, P < 0.0001).

Table 6.

Univariate predictors of mortality

| Hazard ratio | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.027 | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 1.608 | 0.005 |

| NYHA class | 1.678 | <0.001 |

| LVEF, % | 0.966 | <0.001 |

| Exercise time | 0.788 | <0.001 |

| HR reserve | 0.986 | <0.001 |

| Peak HR | 0.989 | <0.001 |

| HR at 1 min recovery | 0.983 | 0.02 |

| HR at 2 min recovery | 0.974 | <0.001 |

| HRRec1 | 0.991 | <0.001 |

| HRRec1 ≤ 4 bpm | 2.146 | <0.001 |

| Peak VO2 (ml/kg per minute) | 0.916 | <0.001 |

| Peak VO2 < 14VO2 < 14 (ml/kg per minute) | 2.011 | <0.001 |

| nVE/VCO2 | 1.070 | <0.001 |

| nVE/VCO2 > 34 | 2.461 | <0.001 |

| Non-ischemic origin of HF | 0.584 | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers use | 0.568 | <0.001 |

| HRR2 | 0.997 | 0.47 |

| Statins | 0.903 | 0.57 |

| Hypertension | 0.707 | 0.08 |

| Diabetes | 1.406 | 0.09 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1.188 | 0.37 |

| Resting HR | 1.001 | 0.88 |

| Smoking | 0.983 | 0.90 |

| Weight | 0.995 | 0.16 |

| BMI | 0.981 | 0.13 |

LVEF Left ventricular ejection fraction, HR heart rate, HRRec1 heart rate recovery at first minute recovery, HRRec2 heart rate recovery at second minute recovery, nVE/VCO2 ventilation for a given carbon dioxide production at nadir, BMI body mass index

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for the three groups based on HRRec (Fig. 1) suggests a significant difference among the groups, with group-1 having the worst prognosis. The relative risk of groups 1 and 2 were 2.44 (95% CLM = 1.8, 3.3) and 1.4 (95% CLM = 0.99, 2.04), respectively. The estimated survival probabilities at 1, 5, and 10 years were 91, 64, and 43% for group-1; 94, 76, and 63% for group-2; and 92, 82, and 70% for group-3.

Fig. 1.

Estimated survival probability in years for patients with heart failure grouped by heart rate recovery (HRRec) during the first minute of active recover after a maximal exercise test

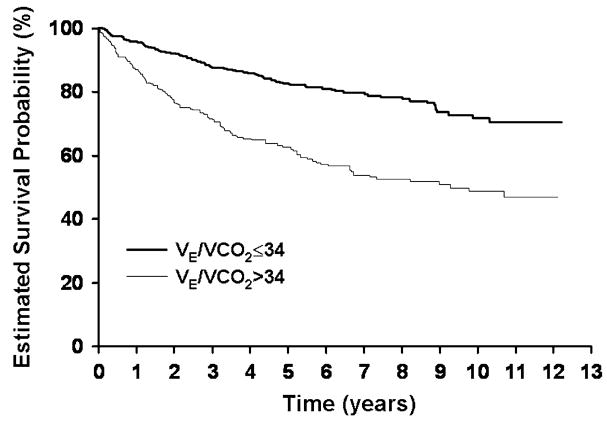

Figures 2 and 3 show Kaplan–Meier survival analyses for groups based on peak VO2, higher or lower than 14 ml/kg per minute (Fig. 2) and for groups based on the nadir of VE/VCO2, higher or lower than 34 (Fig. 3). Survival was significantly higher in groups with higher peak VO2 and lower nadir of VE/VCO2 Multivariate analysis suggests that after adjusting for age, gender, NYHA class and LVEF, HRRec at 1 min was not predictive of mortality. Also after adjusting for age, gender, NYHA class, and LVEF, the relative risk of groups 1 and 2 were 1.78 (95% CLM = 1.3, 2.4) and 1.2 (95% CLM = 0.84, 1.75), respectively. When HRRec was expressed in ranks, it was independently predictive. However, when exercise time, VE/VCO2, or VO2max were added to the ranked model, HRRec lost independent significance (P = 0.16, 0.053, and 0.058, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Estimated survival probability in years for patients with heart failure grouped by peak oxygen consumption (VO2 ) during a maximal exercise test

Fig. 3.

Estimated survival probability in years for patients with heart failure grouped by the nadir of ventilatory equivalent for the metabolic production of carbon dioxide (VE/VCO2 ) during a maximal exercise test

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to evaluate the predictive value of HRRec as a prognostic indicator in patients with a history of chronic HF. In addition, we compared the prognostic strength of HRRec with other commonly obtained variables associated with prognosis in the HF population. Although a number of studies have explored HRRec and its relationship to disease severity as well as prognosis, our study examined the role of HRRec in a larger well defined cohort of HF patients, with a history of both ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathies.

A critical point regarding the measurement of HRRec is the specific definition of this variable and the type of recovery implemented in the studies. The present study defined HRRec as the difference between HR at peak exercise and at 1 and 2 min after exercise. For the purpose of this study, we used HRRec at 1 min into the active recovery phase of the exercise test. In previous studies, authors have used several different cut-off points to establish this threshold, ranging from 6.5 to 18 bpm (Arena et al. 2006; Bilsel et al. 2006; Nanas et al. 2006). Further, there are a number of differences among these studies with regards to the recovery phase of the exercise testing. While some studies have applied passive recovery after achieving peak VO2, Arena et al. (2006) and Wolk et al. (2006) utilized active recovery. Subsequently, lower cut-off points (6.5 bpm) were used in those two studies. Because the optimal clinically useful cut-off value for HRRec in patients with HF has not been established, we attempted to estimate empirically optimal cut-off points or thresholds.

Our univariate analysis clearly supports the prognostic importance of HRRec. However, the results of the multivariate analysis were rather conflicting, potentially due to the poor distribution of HRRec with outliers in both directions. To overcome this concern, ranked HRRec was computed, assigning the best recovery with the highest rank. After adjusting for age, gender, NYHA class, and LVEF, the ranked version of HRRec was predictive of mortality. However, when exercise time, VE/VCO2, or VO2 peak (ml/kg per minute) were added to the model, ranked HRRec lost its independent significance, suggesting that much, but perhaps not all of the predictive value of HRRec is overshadowed by these other variables. Therefore, the main finding of this study was that HRRec after symptom limited exercise testing may be a useful tool in assessing prognosis in HF patients, however, this variable is not independent of VE/VCO2, VO2 peak, or exercise time.

Studies performed in the last few years have provided conflicting results concerning the predictive values of HRRec and other variables. Lipinsky and colleagues (Lipinski et al. 2005) measured HRRec during passive recovery at 1, 2, 3 and 5-min points and found that patients with a normal HRRec after 2 min had improved survival compared to patients with an abnormal 2-min HRRec. Bilsel and colleagues (Bilsel et al. 2006) studied HF patients, who underwent symptom limited exercise test and measured HRRec at 1 min of passive recovery. These authors suggest that the presence of abnormal HRRec (≤18 bpm) together with low peak VO2 (≤14 ml/kg per minute) were the only significant predictors of mortality. Similarly, Nanas et al. (2006) found that HRRec at 1-min passive recovery was an independent prognostic. Arena and colleagues (Arena et al. 2006) utilized active recovery and found that HRRec at 1 min provided additional prognostic information when assessed together with VE/VCO2 slope. Further, Wolk et al. (2006) recently published results of a similar study that utilized HRRec at 1 min of active recovery. These authors report significant differences between the groups for a number of parameters; restrictive changes in the lungs, exercise time, peak VO2, VE/VCO2 ratios, and chronotropic response to exercise. There were also indications of differences in LV filling pressures and left atrial pressure. Taken together, it can be surmised that HRRec is a clinically useful index for identifying patients with distinct and characteristic echocardiographic, neurohormonal and hemodynamic changes.

In the present study, the group with the slowest HRRec had higher all-cause mortality and NYHA class, lower exercise capacity, lower LVEF, and a higher proportion of patients with ischemic HF. Conversely, group-3 demonstrated that the fastest HRRec had the smallest proportion of patients with ischemic etiology of HF, lower NYHA class, highest LVEF, highest exercise capacity and longer survival rate. These patients also tended to be younger and there was higher proportion of women in the group when compared to group-1. When compared to other prognostic factors in the univariate analysis, HRRec ≤ 4 bpm was similar to VO2 peak ≤ 14 ml/kg per minute and was the second strongest predictor of mortality after the nadir of VE/VCO2 > 34. HRRec offers a practical application, especially for those facilities which perform exercise tests without more sophisticated non-invasive gas exchange analysis.

Multivariate analysis suggested that the risk of mortality was higher for older male patients and for those with a higher NYHA class. At the same time, survival odds increased for those with longer exercise time, faster HRRec, higher peak systolic blood pressure, higher BMI and those using beta blockers. The slight protective effect of BMI could be explained by the fact that heavy subjects, who achieved the same exercise time as their lighter counterparts, must be fitter. Interestingly, after exercise time was added to this model, HRRec and VO2 peak were no longer significantly prognostic. Using this analysis, VE/VCO2 retained only marginal independent prognostic value.

It has been suggested that specific medication use may influence HRRec. In particular, both beta-blocker and statin use have demonstrated conflicting results with regards to their impact on HRRec. Racine and colleagues (Racine et al. 2003) suggest that 6 months of beta-blocker therapy does not significantly improve HRRec up to 3 min after a maximal exercise test. Conversely, Lipinski et al. (2005) supports the value of HRRec, independent of beta-blocker use, by demonstrating significant differences at the second and third minute of recovery, and thus showing a faster HRRec in patients taking beta-blockers. The results of the present study suggest that beta-blockers influenced HRRec at 1 min but their influence on HRRec at 2 min was not significant. The resting HR, peak HR, HR at 1- and 2-min recovery were lower in the beta-blocker group, but heart rate reserve was not significantly different. Importantly, there were 79.7% of survivors in the group taking beta-blockers, whereas there were only 63.5% survivors in the group of patients not taking these medications. It is apparent that further investigation is needed in this area to clearly identify the influence beta-blocker therapy has on HRRec and further discriminate the influence of different cut-off values for patients being treated by beta-blocker therapy.

Similarly, statin therapy may also have influence on HRRec in the HF population. Pliquet and colleagues (Pliquett et al. 2003) suggest that statins may partly restore sympathovagal balance. These authors found partial normalization of autonomic function may be a result of the effects of statins on neurohumoral stimulation in the rabbit model of HF. More recently, short-term treatment with atorvastatin was found to increase HRV, decrease QT interval variability, and shorten QTc interval duration in patients with advanced chronic heart failure (Vrtovec et al. 2005). In contrast, however, Hamaad et al. (Hamaad et al. 2005) found no effect on the time domain of HRV indices in small group of heart failure patients on statins, which may suggest a lesser degree or potentially no effect of statins on parasympathetic tone. The results of the present study suggest that patients currently taking statin drugs exhibited the same HRRec response as those not on statins.

Clinical and practical implications

Heart rate recovery is a safe and easy measurement with the potential to provide considerable prognostic information for patients with HF. Further HRRec has the potential to be used as a marker of treatment efficacy as it has been suggested that HRRec in HF patients can be improved through exercise training (Dimopoulos et al. 2006; Streuber et al. 2006). Unfortunately, it has yet to be determined by means of a controlled prospective study, whether improvements in HRRec can also improve the prognosis in HF patients. However, our findings suggest that HRRec may be an important target for intervention in HF patients.

Conclusions

The main finding of this study was that HRRec after a maximal exercise test is a useful tool in assessing prognosis in HF patients. In addition, another easily obtainable variable, exercise time was strongly and independently predictive of prognosis. Therefore, HRRec and exercise time might be used as prognostic indicators in those settings where more sophisticated measures of gas analysis are not routinely performed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kathy O’Malley and Minelle Hulsebus for their help with data collection and Renee Blumers for her help in manuscript preparation. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants: HL71478 and HL07111. Vera Kubrychtova, a visiting graduate student from Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic was supported by Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic and the Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement The authors of this study have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Vera Kubrychtova, Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic.

Thomas P. Olson, Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Joseph 4-225C, Rochester, MN 55905, USA, e-mail: olson.thomas2@mayo.edu

Kent R. Bailey, Division of Biostatistics, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Prabin Thapa, Division of Biostatistics, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Thomas G. Allison, Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Joseph 4-225C, Rochester, MN 55905, USA

Bruce D. Johnson, Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Joseph 4-225C, Rochester, MN 55905, USA

References

- Arai Y, Saul JP, Albrecht P, Hartley LH, Lilly LS, Cohen RJ, et al. Modulation of cardiac autonomic activity during and immediately after exercise. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H132–H141. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.1.H132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arena R, Myers J, Aslam SS, Varughese EB, Peberdy MA. Peak VO2 and VE/VCO2 slope in patients with heart failure: a prognostic comparison. Am Heart J. 2004;147:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arena R, Guazzi M, Myers J, Peberdy MA. Prognostic value of heart rate recovery in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2006;151:851.e7–851.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsel T, Terzi S, Akbulut T, Sayar N, Hobikoglu G, Yesilcimen K. Abnormal heart rate recovery immediately after cardiopulmonary exercise testing in heart failure patients. Int Heart J. 2006;47:431–440. doi: 10.1536/ihj.47.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicoira M, Davos CH, Francis DP, Doehner W, Zanolla L, Franceschini L, et al. Prediction of mortality in chronic heart failure from peak oxygen consumption adjusted for either body weight or lean tissue. J Card Fail. 2004;10:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole CR, Blackstone EH, Pashkow FJ, Snader CE, Lauer MS. Heart-rate recovery immediately after exercise as a predictor of mortality. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1351–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies LC, Wensel R, Georgiadou P, Cicoira M, Coats AJ, Piepoli MF, et al. Enhanced prognostic value from cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic heart failure by non-linear analysis: oxygen uptake efficiency slope. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:684–690. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulos S, Anastasiou-Nana M, Sakellariou D, Drakos S, Kapsimalakou S, Maroulidis G, et al. Effects of exercise rehabilitation program on heart rate recovery in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:67–73. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200602000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson DW, Berg WJ, Roach PJ, Oren RM, Mark AL. Effects of heart failure on baroreflex control of sympathetic neural activity. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:523–531. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90998-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis GS, Benedict C, Johnstone DE, Kirlin PC, Nicklas J, Liang CS, et al. Comparison of neuroendocrine activation in patients with left ventricular dysfunction with and without congestive heart failure. A substudy of the studies of left ventricular dysfunction (SOLVD) Circulation. 1990;82:1724–1729. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.5.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DP, Shamim W, Davies LC, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Anker SD, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing for prognosis in chronic heart failure: continuous and independent prognostic value from VE/VCO(2)slope and peak VO(2) Eur Heart J. 2000;21:154–161. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitt AK, Wasserman K, Kilkowski C, Kleemann T, Kilkowski A, Bangert M, et al. Exercise anaerobic threshold and ventilatory efficiency identify heart failure patients for high risk of early death. Circulation. 2002;106:3079–3084. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000041428.99427.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt GH, Sullivan MJ, Thompson PJ, Fallen EL, Pugsley SO, Taylor DW, et al. The 6-minute walk: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J. 1985;132:919–923. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaad A, Sosin M, Lip GY, MacFadyen RJ. Short-term adjuvant atorvastatin improves frequency domain indices of heart rate variability in stable systolic heart failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:183–187. doi: 10.1007/s10557-005-2219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh DS, Vittorio TJ, Barbarash SL, Hudaihed A, Tseng CH, Arwady A, et al. Association of heart rate recovery and maximum oxygen consumption in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:942–945. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg M, Tager IB. Oxygen uptake efficiency slope: an index of exercise performance and cardiopulmonary reserve requiring only submaximal exercise. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:194–201. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00691-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger C, Lahm T, Zugck C, Kell R, Schellberg D, Schweizer MW, et al. Heart rate variability enhances the prognostic value of established parameters in patients with congestive heart failure. Z Kardiol. 2002;91:1003–1012. doi: 10.1007/s00392-002-0868-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski MJ, Vetrovec GW, Gorelik D, Froelicher VF. The importance of heart rate recovery in patients with heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Card Fail. 2005;11:624–630. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.06.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malfatto G, Branzi G, Gritti S, Sala L, Bragato R, Perego GB, et al. Different baseline sympathovagal balance and cardiac autonomic responsiveness in ischemic and non-ischemic congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3:197–202. doi: 10.1016/S1388-9842(00)00139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini DM, Eisen H, Kussmaul W, Mull R, Edmunds LH, Jr, Wilson JR. Value of peak exercise oxygen consumption for optimal timing of cardiac transplantation in ambulatory patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1991;83:778–786. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.3.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray JJ, Stewart S. Epidemiology, aetiology, and prognosis of heart failure. Heart. 2000;83:596–602. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.5.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers J, Gullestad L, Vagelos R, Do D, Bellin D, Ross H, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing and prognosis in severe heart failure: 14 mL/kg/min revisited. Am Heart J. 2000;139:78–84. doi: 10. 1016/S0002-8703(00)90312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanas S, Anastasiou-Nana M, Dimopoulos S, Sakellariou D, Alexopoulos G, Kapsimalakou S, et al. Early heart rate recovery after exercise predicts mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliquett RU, Cornish KG, Zucker IH. Statin therapy restores sympathovagal balance in experimental heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:700–704. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00265.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine N, Blanchet M, Ducharme A, Marquis J, Boucher JM, Juneau M, et al. Decreased heart rate recovery after exercise in patients with congestive heart failure: effect of beta-blocker therapy. J Card Fail. 2003;9:296–302. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2003.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwinkel ET, Bloomfield DM, Arwady MA, Goldsmith RL. Exercise and autonomic function in health and cardiovascular disease. Cardiol Clin. 2001;19:369–387. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8651(05)70223-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostagno C, Olivo G, Comeglio M, Boddi V, Banchelli M, Galanti G, et al. Prognostic value of 6-minute walk corridor test in patients with mild to moderate heart failure: comparison with other methods of functional evaluation. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:247–252. doi: 10.1016/S1388-9842(02)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streuber SD, Amsterdam EA, Stebbins CL. Heart rate recovery in heart failure patients after a 12-week cardiac rehabilitation program. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:694–698. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.09.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrtovec B, Okrajsek R, Golicnik A, Ferjan M, Starc V, Radovancevic B. Atorvastatin therapy increases heart rate variability, decreases QT variability, and shortens QTc interval duration in patients with advanced chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.06.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijbenga JA, Balk AH, Meij SH, Simoons ML, Malik M. Heart rate variability index in congestive heart failure: relation to clinical variables and prognosis. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:1719–1724. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk R, Somers VK, Gibbons RJ, Olson T, O’Malley K, Johnson BD. Pathophysiological characteristics of heart rate recovery in heart failure. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:1367–1373. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000228949.78023.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]