Abstract

The EGFR pathway has emerged as a key target in non-small-cell lung cancer. EGF receptor (EGFR) inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer is achieved via small molecular tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as erlotinib or gefitinib, or monoclonal antibodies such as cetuximab. A growing body of evidence is identifying potential molecular predictors of response and toxicity. This includes tumor-related molecular markers, such as EGFR mutation and copy number, as well as germline markers such as polymorphisms in EGFR or EGFR pathway-related genes. This review focuses on the current state of knowledge of predictors of response and toxicity to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer.

Keywords: cancer genetics, EGFR, lung cancer, predictive markers

The treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been revolutionized by the development of targeted agents. The EGFR pathway has emerged as a key target in NSCLC. A member of the ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase family, which also includes ErbB2 (her2), ErbB3 and ErbB4, the EGF receptor (EGFR) is a transmembrane protein consisting of an extracellular binding domain, a hydrophobic transmembrane segment and a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain. In response to ligand binding, EGFR is activated via dimerization and subsequent autophosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase domain. Phosphorylation activates downstream pathways including the MAPK, PI3K/AKT and STAT signaling pathways and ultimately stimulates cell growth and proliferation [1]. Overexpression of EGFR family members has been seen in a variety of solid tumors, and targeted agents against this family of receptors have been a focus of development [2].

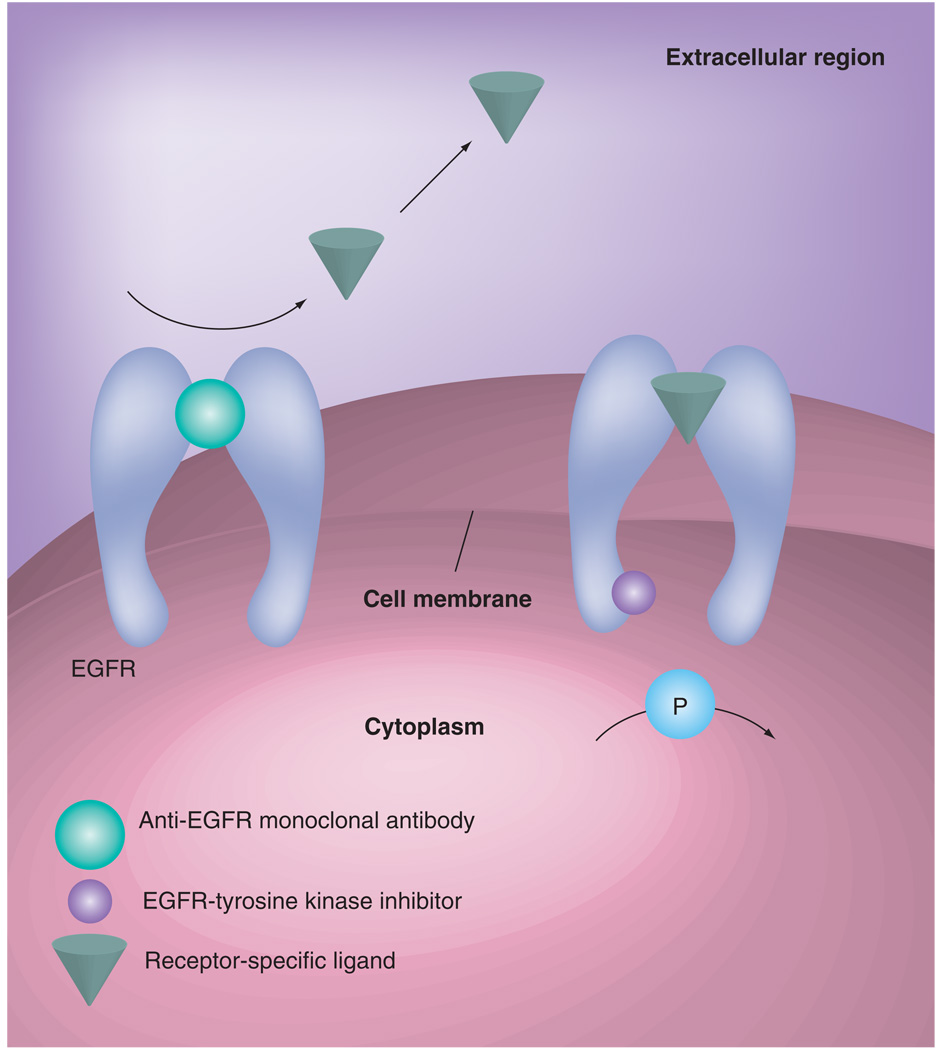

In lung cancer, EGFR is targeted via small molecular tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as erlotinib or gefitinib, or monoclonal antibodies such as cetuximab (Figure 1). A growing body of evidence is identifying molecular predictors of response and toxicity. This includes tumor related molecular markers, such as EGFR mutation, copy number and immunohistochemical protein-expression, as well as germline markers such as polymorphisms in EGFR or EGFR-related genes. This review focuses on the current state of knowledge of predictors of response and toxicity to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer.

Figure 1. Mechanisms of action of anti-EGFR drugs.

Inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and invasion, metastatsis and tumor-induced neoangiogenesis. Induction of cancer cell cycle arrest and potentiation of antitumor activity of cytotoxic drugs and radiotherapy.

Reproduced with permission from [2].

Clinical background

Small molecular TKIs

Erlotinib and gefitinib are both small molecular TKIs of EGFR. Despite similar promise in early studies, only erlotinib is currently approved in the USA for the treatment of NSCLC. BR.21, a randomized Phase III trial of erlotinib versus placebo in previously treated patients with advanced NSCLC, showed significant improvement in survival with erlotinib [3]. In this study, 731 patients with one–two prior chemotherapy regimens for advanced NSCLC were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to receive erlotinib or placebo. Response rate was 8.9% in the erlotinib group and less than 1% in the placebo group. Overall survival was significantly improved in the erlotinib group, at 6.7 months versus 4.7 months.

Although gefitinib also had promising response rates in Phase II studies [4,5], an overall survival (OS) benefit was not shown in IRESSA™ Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer (ISEL), the randomized Phase III trial of gefitinib versus placebo [6]. Some researchers have postulated that differences in dose (erlotinib was dosed at the maximum tolerated dose [MTD], whereas gefitinib was dosed well below its MTD) may account for these different findings. In addition, ISEL and BR.21 had different eligibility requirements regarding progression, with ISEL, but not BR.21, requiring patients to have progressed within 90 days on the prior chemotherapy regimen [7]. Gefitinib in the USA is currently only used in patients who are experiencing ongoing benefits or are on clinical trials, although it is on the market in Japan, Korea and several other Asian countries. However, of note, are several large trials that have investigated gefitinib in comparison to docetaxel in the previously treated NSCLC setting [8–10], and in general have shown comparable efficacy results, with the INTEREST trial, which had 1466 patients, demonstrating noninferiority [9].

Monoclonal antibodies

Cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody to EGFR, may also have a benefit in NSCLC. A recently reported Phase III trial compared cisplatin/vinorelbine with cisplatin/vinorelbine and cetuximab in the treatment of first-line NSCLC [11]. A total of 1125 patients with advanced NSCLC whose tumors expressed EGFR were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to cisplatin/vinorelbine versus cisplatin/vinorelbine with cetuximab. Although no statistically significant difference in progression free survival (PFS) was seen, there was a 1-month improvement in OS favoring the cetuximab arm.

Tumor markers of response

EGFR mutations

Retrospective analyses consistently demonstrated clinical predictors of response to the EGFR TKIs, such as Asian ethnicity, female gender, adenocarcinoma and bronchoalveolar histology, and nonsmoking history [12,13]. In addition to clinical correlates of response to EGFR inhibition, mutations in the EGFR gene have been discovered that are associated with response [14,15]. Lynch et al. reported in-frame deletions and missense mutations involving the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain in eight out of nine patients responsive to gefitinib who had tumor tissue available. These mutations were not found in the matched normal tissue of the same patients, or in the tumor tissues of seven nonresponding patients [14]. Similarly, Paez et al. found mutations in the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain in all of five tumor samples from responding patients and none of four tumor samples from nonresponders [15]. In vitro studies showed that in the presence of EGF the mutated EGFR had significantly increased and prolonged activation as compared with wild-type. The mutated receptors were also more sensitive to inhibition by gefitinib [14].

These activating EGFR mutations localize to a small region in the EGFR gene that encodes the tyrosine kinase domain. The most common, now classical, mutations are an in-frame deletion in exon 19 and a missense mutation at codon 858 that leads to an arginine to leucine substitution (L858R). The presence of these mutations is closely correlated to clinical and pathologic factors, all of which were clinically observed to be associated with response to EGFR TKIs: female gender, Asian ethnicity, adenocarcinoma histology, never-smoking history [16].

Several Phase II studies have attempted to define the response rates and clinical outcomes of a strategy of using EGFR TKIs in patients selected for the presence of EGFR mutations (Table 1). Several Japanese studies have demonstrated response rates of 75–90% to gefitinib among patients with EGFR mutations, with a median PFS of 7.7–11.5 months [17–20]. A North American study showed response rates of 55% with median PFS of 9.2 months [21]. Of note, this study included atypical EGFR mutations in addition to the classical exon 19 deletion and L858R mutations. In a Spanish trial, treatment with erlotinib to patients with EGFR mutations yielded a response rate of 82% and median time to progression (TTP) of 13.3 months [22].

Table 1.

Phase II studies using EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR mutation-postive patients.

| Study | n | Treatment | Response rate median (%) (95%CI) | PFS median (95% CI) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asahina et al. | 16 | Gefitinib | 75 (48–93) | 8.9 mo (6.7–11.1) | [17] |

| Yoshida et al. | 21 | Gefitinib | 91 (70–99) | 7.7 mo (6–…) | [18] |

| Inoue et al. | 16 | Gefitinib | 75 (54–96) | 9.7 mo (7.4–9.9) | [19] |

| Tamura et al. | 28 | Gefitinib | 75 (58–91) | 11.5 mo (NR) | [20] |

| Sequist et al. | 34 | Gefitinib | 55 (33–70) | 9.2 mo (6.2–11.8) | [21] |

| Paz-Ares et al. | 37 | Erlotinib | 82 (66–92) | 13.3 mo (NR) | [22] |

CI Confidence interval; EGFR; EGF receptor; Mo: Months; NR: Not reported; PFS: Progression free survival; TKI: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Preliminary results were recently reported of The First Line IRESSA Versus Carboplatin/Paclitaxel in Asia study (IPASS), in which 1217 patients who were never/light smokers were randomized to receive gefitinib or carboplatin and taxol. In this Asian population, 453 (74.4%) patients in the gefitinib group experienced disease progression, compared with 497 (81.7%) patients in the chemotherapy arm (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.65–0.85; p < 0.0001). When analyzed by EGFR mutation status, among EGFR mutation-positive patients, PFS was significantly improved among those treated with gefitinib compared with those treated with carboplatin/paclitaxel (HR: 0.48; p < 0.0001). For EGFR mutation-negative patients, however, the chemotherapy arm did better (HR: 2.85; p < 0.0001) [23]. These results are preliminary and OS results are awaited; however they provide an intriguing insight into the potential of targeted treatment based on EGFR mutation status.

Although response rates are high among patients with EGFR mutations, both de novo and acquired resistance remain issues. Numerous studies suggest that the atypical EGFR mutations are significantly less predictive of response as compared with the classical mutations. In addition, acquired resistance can develop via several mechanisms. The first described acquired resistance mechanism was a secondary EGFR mutation, T790M, which causes a threonine to methionine change at position 790 in the catalytic cleft of the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain. The methionine substitution introduces a bulkier side chain at this position, causing steric hindrance that is thought to interfere with binding of erlotinib [24]. Recently, MET amplification has also been identified as a mechanism of secondary resistance [25,26].

EGFR copy-number

Increased EGFR copy-number has also been reported to be associated with response and survival to EGFR TKIs. Capuzzo et al. evaluated tumors from 102 NSCLC patients treated with gefitinib for EGFR status by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), DNA sequencing and immunohistochemistry [27]. Patients with gene amplification (presence of tight EGFR gene clusters and a ratio of EGFR gene to chromosome of greater than or equal to 2, or greater than or equal to 15 copies of EGFR per cell in 10% or more of analyzed cells) or high polysomy (≥4 copies in ≥ 40% of cells) had significantly improved response, TTP and OS compared with those with no or low copy-number. Interestingly, gene copy-number does not seem to correlate with the reported clinical predictors of response. In an analysis of patients with adenocarcinoma or bronchioloalveolar carcinoma treated with gefitinib, Hirsh et al. reported that increased EGFR copy-number detected by FISH was associated with improved survival [28]. In a prospective Phase II trial, patients who were never smokers or were EGFR FISH- and phospho-Akt-positive were treated with gefitinib [29]. Overall response was high in this selected population, at 48%, with median TTP of 6.4 months. EGFR FISH-positive patients had significantly better outcomes than FISH-negative patients, with response rates of 68% versus 9.1%, and TTP of 7.6 versus 2.7 months. EGFR mutations were also tested in this trial and patients with exon 19 or 21 mutations had significant higher response rates compared with wild-type patients.

EGFR copy-number has also been evaluated in relation to response to the monoclonal antibody cetuximab. Of 221 patients enrolled in a Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) trial of chemotherapy with cetuximab versus chemotherapy followed by cetuximab in advanced NSCLC, 76 patients were assessable for EGFR FISH [30]. 59% of these patients were classified as FISH-positive, based on four or more gene copies per cell in 40% or more of cells, or gene amplification. Response rates were numerically higher in the FISH-positive population, although the difference was not statistically significant. Interestingly, PFS (6 months vs 3 months) and OS (15 months vs 7 months) were significantly better in the FISH-positive patients compared with FISH-negative patients in this retrospective analysis.

Analysis of large randomized controlled trials

Molecular analysis of the large randomized trials of the EGFR TKIs has been carried out to assess whether EGFR mutation or copy number significantly predicts outcomes. Of the 731 patients in the BR.21 trial, adequate tissue sample was available for 328 [31]. Of these, 325 were analyzed for immunohistochemistry (IHC), 197 for EGFR mutations and 221 for EGFR copy-number. Response rate was significantly higher among patients with high polysomy or amplification, but was not associated with EGFR mutations. However, of note is that 24 of the 45 mutations found were novel mutations rather than the classical exon 19 deletions or L858R that would be expected to have high response rates. Subsequent reanalysis with more sensitive methods for EGFR mutation detection in BR.21 showed higher response rates and a trend toward improved survival with erlotinib among those with exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R mutations [32]. Analysis of the ISEL trial has also been conducted, and showed high EGFR copy-number to be associated with survival; patients with EGFR mutations in this trial had higher response rates but there were not sufficient data for survival analysis [33]. Other studies have shown a close association of EGFR mutation with response: analysis of the the IRESSA dose evaluation in advanced lung cancer (IDEAL) study showed that 46% of those with EGFR mutation had response, compared with 10% of mutation-negative patients [34]. Patients with EGFR amplification also had a trend toward higher response to gefitinib, 29% versus 15% [34].

EGFR immunohistochemistry

EGFR expression levels as measured by IHC have not been shown to correlate with response to EGFR TKIs [35,36]. In lung cancer, the one positive trial using the monoclonal antibody cetuximab was a trial that selected for patients with EGFR expression [11]. However, most studies of cetuximab have not shown an association with EGFR IHC and response [37]. In colorectal cancer, a Phase III trial compared cetuximab and irinotecan to cetuximab monotherapy in the irinotecan failure setting. Although immunohistochemical evidence of EGFR expression was required for entry into the trial, the degree of EGFR expression, either in terms of percentage of EGFR-expressing cells or EGFR staining intensity, did not correlate with response rate [38]. Therefore, although the FLEX trial, which showed a survival benefit for the addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced disease, selected patients based on EGFR expression, it remains to be seen whether EGFR expression is truly associated with cetuximab outcomes.

Kras mutation

Kras mutations in lung cancer appear, in general, to be exclusive to EGFR mutations and are more associated with smoking [39,40]. Kras mutations have been associated with resistance to EGFR TKIs. Pao et al. reported that nine out of 38 (24%) tumors refractory to gefitinib or erlotinib had kras mutations, while none of 21 sensitive tumors had kras mutations [41]. Similarly, van Zandwijk et al. found no kras mutations among responders to gefitinib in an expanded access program [42]. In a retrospective analysis of TRIBUTE, the randomized Phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without erlotinib in the first-line NSCLC setting, Eberhard et al. reported worse TTP and survival among kras mutant patients treated with chemotherapy with erlotinib as compared with chemotherapy alone, although it should be noted that numbers are small in this subset analysis [43]. In BR.21, response to erlotinib was lower among kras mutant patients than wild-type, with the only kras mutant patient who responded also having EGFR amplification. There was also a trend toward worse survival among kras mutant patients treated with erlotinib, while kras wild-type patients treated with erlotinib had improved survival [32].

Interestingly, multiple reports in colorectal cancer have shown a negative correlation of kras mutation with response to the EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab [44–48]. Analysis of the Phase III CRYSTAL trial, irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid (FOLFIRI) with or without cetuximab in the first-line metastatic colorectal setting, showed that among kras wild-type patients, the addition of cetuximab was associated with improved response and PFS. However, among kras mutant patients, there was no difference in response or PFS [49]. It remains to be seen whether kras mutations can predict responsiveness to cetuximab in lung cancer.

Germline EGFR polymorphisms & response & toxicity

Polymorphic variation in EGFR & EGFR-related genes

Polymorphisms in EGF and EGFR have been identified that are thought to be functional and influence gene-expression, promoter activity and protein production [50–56]. The CA simple sequence repeat 1 (CA-SSR1) is a highly polymorphic locus in intron 1 of EGFR, containing 14–21 CA dinucleotide repeats [50,57]. Length of the CA repeat has been inversely correlated with EGFR gene transcription, with shorter alleles having higher transcription [51]. In tumors, short CA repeats were associated with elevated EGFR expression compared with those with long CA repeats [52].

Other polymorphisms in EGFR have also been reported that are thought to be functional. The −16G/T polymorphism (rs712829) is located in the promoter region of EGFR and encodes a change from guanine to thymine. This polymorphism is located in an important binding site for the transcription factor Sp1, and the T allele is associated with increased EGFR expression [53]. The −91C/A polymorphism (rs712830) is also located in the EGFR promoter region and the variant form may be associated with differential protein production [58,59]. The R497K polymorphism (rs11543848) encodes an A->G alteration resulting in a substitution of arginine by lysine. The Lys allele is associated with decreased activity of EGFR [54].

Ethnic variation has been described in these polymorphisms, which is interesting in light of different responsiveness to EGFR inhibitors by ethnicity. Asian ethnicity is associated with longer CA dinucleotide repeats, while the variant forms of the −216G/T and −191C/A polymorphisms are less common [58,59]. Interestingly, the polymorphic variants associated with increased EGFR production were rare in Asians compared with other ethnicities.

Other polymorphisms in the EGFR pathway that have been investigated include variations in EGF, ABCG2 and cyclin D1 among others (Table 2). EGFR TKIs appear to be substrates for multidrug resistance efflux transporter proteins such as ABCG2, which appears to actively pump the drug from cells [60–62]. Functional polymorphisms in ABCG2 have been described that alter the expression or activity of the protein [63,64], leading to investigations of whether these polymorphisms may affect outcomes in patients treated with EGFR TKIs.

Table 2.

Selected EGFR and associated pathway polymorphisms.

| Polymorphisms | Proposed function |

|---|---|

| EGFR Intron 1 (CA)n | Shorter length associated with higher EGFR gene transcription |

| EGFR -216 G/T | T allele associated with increased promoter activity |

| EGFR -191 C/A | A allele associated with higher protein production |

| EGFR R497K A -> G | A -> G alteration resulting in substitution of Arg by Lys Lys associated with decreased activity of EGFR |

| EGF +61 A/G | A allele associated with less EGF production |

| ABCG2 421C/A (Q141K) | A allele associated with reduced transport of EGFR TKIs |

| ABCG2 -15994G/A | A allele associated with higher ABCG2 expression |

| ABCG2 -15622C/T | T allele associated with lower ABCG2 expression |

| ABCG2 16702G/A | A allele associated with higher ABCG2 expression |

| ABCG2 1143C/T | T allele associated with lower ABCG2 expression |

| FcGR3A 158V/F | T -> G alteration resulting in Val to Phe at position 158; Val associated with stronger binding to IgG1 and mediates antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytoxicity activity more effectively |

| FcGR2A 131H/R | G -> A alteration resulting in His to Arg at position 131; His thought to mediate antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytoxicity more effectively |

EGFR: EGF receptor TKI: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Polymorphisms & clinical outcomes in EGFR TKI treated lung cancer

Several studies have investigated the question of whether polymorphisms in EGFR-related pathways are predictors of response or toxicity to EGFR TKI therapy in lung cancer.

Many of these studies have focused on the intron 1 CA repeat polymorphism. Although there are limitations to the studies presented, including relatively small numbers, retrospective nature of the analysis, and nonhomogenous definitions for what is considered a short versus long repeat length, in general the studies seem to suggest that shorter CA repeat length is associated with better response and survival in patients treated with EGFR TKIs.

Ichihara et al. performed a retrospective analysis of 137 Japanese patients who had received gefitinib [65]. Of these, 98 had specimens available for analysis that included EGFR and kras mutations, EGFR copy-number and EGFR polymorphisms, including the intron 1 CA repeat, −216G/T and −191C/A polymorphisms. They found that the classical EGFR mutations predicted sensitivity to gefinitib. Although none of the polymorphisms studied were significantly associated with response or survival, there was a trend toward shorter CA repeats being associated with prolonged survival among those with a classical drug-sensitive EGFR mutation. Long CA was defined as length of the short allele equal to or greater than 19, or sum of the two alleles equal to or greater than 39 or more; short CA defined as length of short allele less than 19 or sum of two alleles less than 39.

Similarly, Han et al. retrospectively analyzed 86 Korean patients treated with gefitinib for EGFR mutation and CA repeat polymorphism [66]. Again, the classical EGFR mutations were significantly associated with response and survival. In addition, there was a trend towards higher response rates among patients with low CA repeats, defined as sum of two alleles less than or equal to 37 (25 vs 13%; p = 0.16). In multivariate analysis, low CA repeat was associated with high response and TTP, independent of mutation status.

The association of improved outcomes with shorter CA repeats was also reported by Nie et al., who analyzed 70 Chinese patients who had been treated with gefitinib for the CA repeat polymorphism and R497K SNP [67]. They found that patients with shorter repeats, defined as any allele less than or equal to 16, had better response, with partial response of 58% compared with 28% for those where both alleles were less than 16. In addition, patients who had any allele 16 or less had a median survival of 20 months, compared with 11 months for those where both alleles were greater than 16.

In a study of a predominantly Caucasian population, Liu et al. investigated the −216G/T, −191 C/A, intron 1 and Arg497Lys polymorphisms among 92 North American NSCLC patients treated with gefitinib [68]. Shorter CA repeats, defined as 16 or fewer repeats, were associated with improved PFS. In addition, the T allele of the −216G/T polymorphism was associated with improved PFS.

However, not all studies have confirmed the association with the intron 1 CA polymorphism. Gregorc et al. evaluated 175 Caucasian patients treated with gefitinib for EGFR intron 1, −216G/T and −191C/A polymorphisms [69]. These authors did not find any association with the intron 1 CA repeat polymorphism. However, those with the −216/−191 haplotype G-C had lower response rates.

In addition to the EGFR polymorphisms, much interest has centered on polymorphisms in ABCG2 as a mediator of drug toxicity. ABCG2 is a polymorphic efflux transporter protein that has been shown to actively transport EGFR TKIs such as gefitinib and erlotinib [70]. Expression of ABCG2 has been shown to protect EGFR signaling dependent cells from death on exposure to gefitinib [60]. Since SNPs have been described that affect the expression and activity of ABCG2 [63,64,70], it has been hypothesized that these SNPs may affect individual efficacy and toxicity.

The ABCG2 421C>A (Q141K) polymorphism results in a glutamine to lysine substitution in codon 141. The variant has been associated with low ABCG2 expression levels [63,64]. Patients carrying the 421C>A variant have been shown to have significantly higher drug accumulation [70]. Investigators have hypothesized that increased steady state exposure to EGFR TKI would increase the risk for drug-induced toxicity. In 124 patients treated with gefinitib, the ABCG2 421C>A polymorphism was significantly associated with diarrhea. A total of 44% of patients with the variant developed diarrhea compared with only 12% of those who were homozygous wild-type [71].

Rudin et al. reported a prospective trial investigating pharmacogenomic and pharmacokinetic determinants of skin rash and diarrhea among 80 patients with NSCLC, head and neck cancer, and ovarian cancer treated with erlotinib [72]. Polymorphisms in EGFR, CYP3A4 and 3A5, as well as ABCG2, were investigated to assess for association with toxicity. Several novel ABCG2 polymorphisms that were associated with differential ABCG2 expression levels were investigated in this study, in addition to previously described SNPs. Skin toxicity seemed to be associated with trough erlotinib concentration and variability in the EGFR intron 1 polymorphism, while diarrhea was associated with two linked polymorphisms in EGFR promoter, −216G/T and −191C/A. The newly identified ABCG2 polymorphisms, 1143C/T and −15622C/T, were associated with differential erlotinib concentrations, but there was not a definitive association with toxicity.

In addition to skin rash and diarrhea, interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a well described phenomenon to EGFR TKIs. Although studies suggest clinical predictors for ILD such as gender, smoking history and coincidence of interstitial pneumonia [73], there has not yet been data regarding potential molecular predictors of this toxicity.

Polymorphisms & clinical outcomes to EGFR antibodies

To date there is little reported on predictors of cetuximab responsiveness in lung cancer. There have been studies in colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab that offer some insight into potential avenues of study in lung cancer [74–77]. In general these studies have focused on polymorphisms of EGF and EGFR such as those described in the sections above. For example, Goncalves et al. found that a variant of exon 13 in EGFR (R421K) was associated with improved PFS and OS in colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab and irinotecan [77]. In addition, interest has focused on polymorphisms of the immunoglobulin-G fragment-C receptor (FcγR). The Fcγ receptors are of interest as cetuximab is thought to mediate antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytoxicity against cancer cells (ADCC), and the effectiveness of ADCC may depend on the activation of effector cells after engagement with the Fcγ receptors [77–79]. The V/V genotype of the FCGR3A-V158F polymorphism has been associated with higher response to rituximab in follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and the V allele is thought to mediate ADCC more effectively [78]. The H/H genotype of the FCGR2A-H131R polymorphism has also been shown to be predictive of response to rituximab [79].

Analyses of the EGFR pathway polymorphisms in relation to cetuximab outcomes have yielded conflicting results, with disparate findings reported from several small series [71,74–76]. For example, Graziano et al. reported that among 110 colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab and irinotecan, the EGFR intron 1 S/S and EGFR 61G/G genotypes were associated with better OS, while there was no association with EGF, cyclin D1, and FcγR polymorphisms [74]. However, among 39 colorectal patients treated with cetuximab, Zhang et al. reported associations with PFS for the FCGR2A-H131R and FCGR3A-V158F polymorphisms [75,76]. They also reported the A allele of the EGF 61A/G polymorphism was associated with better survival, which is contrary to the Graziano results.

Predictors of cetuximab toxicity are also being investigated. Graziano et al. also investigated the EGF, EGFR, cyclin D1 and FcγR polymorphisms in relation to skin toxicity among patients treated with cetuximab and irinotecan, and found that EGFR intron 1 short allele carriers were more prone to have grade 2–3 skin toxicity compared with those who carried the long alleles [74].

These findings in colorectal cancer are clearly preliminary and limited by small numbers but, as increasing numbers of patients with lung cancer are treated with cetuximab, would be potential targets for further study.

Conclusions

Currently, EGFR inhibition is a valid strategy in the treatment of advanced NSCLC. As EGFR inhibitors, such as the TKI erlotinib, and monoclonal antibodies such as cetuximab, emerge as an important part of the treatment strategy for NSCLC, finding better predictors of response, toxicity and survival will be critical to identifying particular populations of patients who might derive the most benefit.

Future perspective

Much work has been carried out to identify molecular predictors of response and survival outcome with treatment with EGFR inhibitors. Tumor-associated somatic mutations and changes in copy number have been most extensively studied in relation to EGFR TKIs. Germline polymorphisms also appear to have a role in management, with EGFR polymorphisms such as the intron 1 CA repeat polymorphism and polymorphisms in ABCG2 being shown to affect response and toxicity to EGFR TKIs. Less is known about potential molecular markers of prediction for EGFR antibodies such as cetuximab, but investigations are ongoing.

Executive summary

Clinical background

Erlotinib, an EGF receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), improves survival in previously treated, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients compared with placebo. Cetuximab, an EGFR antibody, was recently shown to improve survival when added to chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC.

Tumor markers of response

Somatic mutations in EGFR have been identified that are associated with response, with the exon 19 deletion and L858R substitution being the classical mutations associated with response to EGFR TKIs.

EGFR copy-number has also been identified as a predictive marker, with high polysomy or amplification being associated with response and survival in those treated with EGFR TKIs.

Germline polymorphisms & response, & toxicity

Multiple germline polymorphisms have been studied as predictors of outcome.

The EGFR intron 1 CA repeat polymorphism has been most extensively studied, and most reports suggest that shorter repeat lengths, which is associated with higher transcription, are associated with better response. Polymorphisms in ABCG2 have also been shown to be associated with toxicity.

Acknowledgments

Financial & competing interests disclosureSupported by NIH grants R01CA92824, R01CA074386 and K12 CA087723. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

of interest

of considerable interest

- 1.Jorissen RN, Walker F, Pouliot N, Garrett TPJ, Ward CW, Burgess AW. Epidermal growth factor receptor: mechanisms of activation and signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;284:31–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:1160–1174. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707704. Excellent review article encompassing clinical use of EGF receptor (EGFR) inhibitors in oncology.

- 3. Sheperd FA, Pereira JR, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. Pivotal Phase III trial showing benefit of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) erlotinib in lung cancer.

- 4.Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, et al. Multi-institutional randomized Phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:2237–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA. 2003;290:2149–2158. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. Phase III trial of EGFR TKI gefitinib in lung cancer.

- 7.Stinchcombe TE, Socinski MA. Gefitinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: does it deserve a second chance? Oncologist. 2008;13(9):933–944. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maruyama R, Nishiwaki Y, Tamura T, et al. Phase III study, V-15–32, of gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated Japanese patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:4244–4252. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douillard JV, Kim E, Hirsch V, et al. Gefinitib versus docetaxel in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer pre-treated with platinum-based chemotherapy: a randomized open label Phase III study (INTEREST) J. Thorac. Oncol. 2007;2(8 Suppl 4):S305. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee D, Kim S, Park K, et al. A randomized open-label study of gefitinib versus docetaxel in patients with advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who have previously received platinum-based chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26 Suppl. (Abstract 8025) [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pirker R, Szczesna A, von Pawel J, et al. FLEX: A randomized, multicenter, Phase III study of cetuximab in combination with cisplatin/ vinorelbine (CV) versus CV alone in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26 Suppl. (Abstract 3) Phase III trial showing an overall survival benefit of the EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab in addition to chemotherapy in first-line treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

- 12.Miller VA, Kris MG, Shah N, et al. Bronchoalveolar pathologic subtype and smoking history predict sensitivity to gefitinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:1103–1109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janne PA, Gurubhagavatula S, Yeap BY, et al. Outcomes of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with gefitinib on an expanded access study. Lung Cancer. 2004;44:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. Key initial paper describing EGFR mutations and responsiveness to EGFR TKI.

- 15. Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2005;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. Key initial paper describing EGFR mutations and responsiveness to EGFR TKI.

- 16. Sequist LV, Bell DW, Lynch TJ, Haber DA. Molecular predictors of response to epidermal growth factor receptor antagonists in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25(5):587–595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3585. Excellent review of EGFR TKI predictors of response.

- 17.Asahina H, Yamazaki K, Kinoshita I, et al. A Phase II trial of gefinitib as first-line therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. Br. J. Cancer. 2006;95:998–1004. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshida K, Yatabe Y, Park JY, et al. Prospective validation for prediction of gefitinib sensitivity by epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2007;2(1):22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue A, Suzuki T, Fukuhara T, et al. Prospective Phase II study for chemotherapynaive patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24(21):3340–3346. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamura K, Okamoto I, Negoro S, et al. Multicentre prospective Phase II trial of gefitinib for advanced non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations: results of the West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group trial (WJTOG0403) Br. J. Cancer. 2008;98:907–914. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sequist LV, Martins RG, Spigel D, et al. First-line gefitinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer harboring somatic EGFR mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(15):2442–2449. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paz-Ares L, Sanchez JM, Garcia-Velasco A, et al. A prospective Phase II trial of erlotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor. 2006 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24 Suppl. S18 (Abstract 7020) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mok T. Phase III, randomised, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib (G) vs carboplatin/paclitaxel (C/P) in clinically selected patients (PTS) with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (IPASS); European Society of Medical Oncology Congress; 12–16 September 2008; Stockholm, Sweden: Presented at: (Abstract LBA2) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:786–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bean J, Brennan C, Shih JY, et al. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA. 2007;104(52):20932–20937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710370104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cappuzzo F, Hirsch FR, Rossi E, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene and protein and gefitinib sensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(9):643–655. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, McCoy M, et al. Increased epidermal growth factor receptor gene copy number detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization associated with increased sensitivity to gefinitinb in patients with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtypes: a Southwest Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23(28):6838–6845. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cappuzzo F, Ligorio C, Janne PA, et al. Prospective study of gefitinib in epidermal growth factor receptor fluorescence in situ hybridization-positive/phosph-Akt-positive or never smoker patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: the ONCOBELL trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25(16):2248–2255. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.4300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirsch FR, Herbst RS, Olsen C, et al. Increased EGFR gene copy number detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization predicts outcome in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with cetuximab and chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(20):3351–3357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsao M, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, et al. Erlotinib in lung cancer - molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:133–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu CQ, da Cunha Santos G, Ding K, et al. Role of kras and EGFR as biomarkers of response to erlotinib in National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:4628–4675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, et al. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib in a Phase III placebo-controlled study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24(31):5034–5042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bell DW, Lynch TJ, Haserlat SM, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and gene amplification in non-small cell lung cancer: molecular analysis of the INTACT/IDEAL gefitinib trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23(31):8081–8092. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendelsohn J, Baselga J. Status of epidermal growth factor receptor antagonists in the biology and treatment of cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:2787–2799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey LR, Kris MG, Wolf M, et al. Tumor EGFR membrane staining is not clinically relevant for predicting response in patients receiving gefitinib monotherapy for pretreated advanced non-small cell lung cancer: IDEAL 1 and 2. Proc AACR. 2003 (Abstract LB-170) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galizia G, Lieto E, de Vita F, et al. Cetuximab, a chimeric human mouse anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody, in the treatment of human colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3654–3660. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refratory metastatic colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:337–345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, et al. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in lung cancer: biological and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8919–8923. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tam IYS, Chung LP, Suen WS, et al. Distinct epidermal growth factor receptor and kras mutation patterns in non-small cell lung cancer patients with different tobacco exposure and clinicopathologic features. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:1647–1653. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pao W, Want TY, Riely GJ, et al. kras mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med. 2005;2:E17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Zandwijk N, Mathy A, Boerrigter L, et al. EGFR and kras mutations as criteria for treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: retro- and prospective observations in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2007;18:99–103. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, et al. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and kras are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:5900–5909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benvenuti S, Sartore-Bianchi A, di Nicolantonio F, et al. Oncogenic activation of the ras/raf signaling pathway impairs the response of metastatic colorectal cancers to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody therapies. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2643–2648. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.di Fiore F, Blanchard F, Charbonnier F, et al. Clinical relevance of kras mutation detection in metastatic colorectal cancer treated by cetuximab plus chemotherapy. Br. J. Cancer. 2007;96:1166–1169. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Roock W, Piessevaux H, de Schutter J, et al. kras wildtype state predicts survival and is associated to early radiological response to metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Ann. Oncol. 2008;19:508–515. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lievre A, Bachet JB, Boige V, et al. kras mutations as an independent prognosic factor in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:374–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khambata-Ford S, Garrett CR, Meropol NJ, et al. Expression of epiregulin and amphiregulin and kras mutation status predict disease control in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:3230–3237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Cutsem E, Lang I, D’haens G, et al. kras status and efficacy in the first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with FOLFIRI with or without cetuximab: the CRYSTAL experience. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26 (Abstract 2) [Google Scholar]

- 50. Araujo A, Ribeiro R, Azevedo I, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of the epidermal growth factor and related receptor in non-small cell lung cancer – a review of the literature. Oncologist. 2007;12:201–210. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-2-201. Excellent review of germline polymorphisms in EGFR and EGFR-related pathways.

- 51.Gebhart F, Zanker KS, Brandt B, et al. Modulation of epidermal growth factor receptor gene transcription by a polymorphic dinucleotide repeat in intron 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13176–13180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buerger H, Gebhardt F, Schmidt H, et al. Length and loss of heterozygosity of an intron 1 polymorphic sequence of EGFR is related to cytogenetic alterations and epithelial growth factor receptor expression. Cancer Res. 2000;60:854–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu W, Innocenti F, Wu MH, et al. A functional common polymorphism in a Sp1 recognition site of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moriai T, Kobrin MS, Hope C, Speck L, Korc M. A variant epidermal growth factor receptor exhibits altered type-α transforming growth factor binding and transmembrane signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:10217–10221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhowmick DA, Zhuang Z, Wait SD, Weil RJ. A functional polymorphism in the EGF gene is found with increased frequency in glioblastoma multiforme patients and is associated with more aggressive disease. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1220–1223. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang W, Weissfeld JL, Romkes M, Land SR, Grandis JR, Siegfried JM. Association of the EGFR intron 1 CA repeat length with lung cancer risk. Mol. Carcinog. 2007;46(5):372–380. doi: 10.1002/mc.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Desai AA, Innocenti F, Ratain MJ. Pharmacogenomics: road to anticancer therapeutics nirvana? Oncogene. 2003;22:6621–6628. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nomura M, Shigematsu H, Lin L, et al. Polymorphisms, mutations, and amplification of the EGFR gene in non-small cell lung cancers. PLoS Med. 2007;4(4):E125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu W, Innocenti F, Chen P, et al. Interethnic difference in the allelic distribution of human epidermal growth factor receptor intron 1 polymorphism. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:1009–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elkind NB, Szentpetery Z, Apati A, et al. Mutidrug transporter ABCG2 prevents tumor cell death induced by the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor iressa (gefitinib) Cancer Res. 2005;65:1770–1777. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li J, Sparreboom A, Zhao M, et al. Gefinitib and erlotinib, epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, are substrates for the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)/ABCG2 transporter. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11A:120. (Abstract A251) [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ozvegy-Laczka C, Hegedus T, Varady G, et al. High-affinity interaction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors with the ABCG2 multidrug transporter. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;65:1485–1495. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mizurai S, Aozasa N, Kotani H. Single nucleotide polymorphisms result in impaired membrane localization and reduced ATPase activity in multidrug transporter ABCG2. Int. J. Cancer. 2004;109:238–246. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Imai Y, Nakane M, Kage K, et al. C421A polymorphism in the human breast cancer resistance protein gene is associated with low expression of Q141K protein and low-level drug resistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002;1:611–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ichihara S, Toyooka S, Fujiwara Y, et al. The impact of epidermal growth factor receptor gene status on gefitinib-treated Japanese patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;120:1239–1247. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Han SW, Jeon YK, Lee KH, et al. Intron 1 CA dinucleotide repeat polymorphism and mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor and gefitinib responsiveness in non-small cell lung cancer. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2007;17:313–319. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328011abc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nie Q, Wang Z, Zhang GC, et al. The epidermal growth factor receptor intron 1 (CA)n microsatellite polymorphism is a potential predictor of treatment outcome in patients with advanced lung cancer treated with gefitinib. Eur J. Pharmacol. 2007;570:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu G, Gurubhagavatula S, Zhou W, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor polymorphisms and clinical outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib. Pharmacogenomics J. 2008;8(2):129–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gregorc V, Hidalgo M, Spreafica A, et al. Germline polymorphisms in EGFR and survival in patients with lung cancer receiving gefitinib. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;83(3):477–484. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li J, Cusatis G, Brahmer J, et al. Association of the variant ABCG2 and the pharmacokinetics of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer patients. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007;6(3):432–438. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.3.3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cusatis G, Gregorc V, Ling J, et al. Pharmacogenetics of ABCG2 and adverse reactions to gefitinib. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(23):1739–1742. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rudin CM, Liu W, Desai A, et al. Pharmacogenomic and pharmacokinetic determinants of erlotinib toxicity. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:1119–1127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ando M, Okamoto I, Yamamoto N, et al. Predictive factors for interstitial lung disease, antitumor response, and survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24(16):2549–2556. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.9866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Graziano F, Ruzzo A, Loupakis F, et al. Pharmacogenetic profiling for cetuximab plus irinotecan therapy in patients with refractory advanced colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(9):1427–1434. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang W, Gordon M, Press OA, et al. Cyclin D1 and epidermal growth factor polymorphisms associated with survival in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2006;16:475–483. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000220562.67595.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang W, Gordon M, Schultheis A, et al. FCGR2A and FCGR3A polymorphisms associated with clinical outcome in epidermal growth factor-expressing metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with single-agent cetuximab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25(24):3712–3718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goncalves A, Esteyries S, Taylor-Smedra B, et al. A polymorphism in the EGFR extracellular domain is associated with progression-free survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving cetuximabbased treatment. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cartron G, Dacheus L, Salles G, et al. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcγRIIIA gene. Blood. 2002;99:754–758. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weng WK, Levy R. Two immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms independently predict response to rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:3940–3947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]