Abstract

The kinase Mirk/dyrk1B mediated the clonogenic growth of pancreatic cancer cells in earlier studies. It is now shown that Mirk levels increased 7-fold in SU86.86 pancreatic cancer cells when over a third of the cells were accumulated in a quiescent G0 state, defined by Hoechst/Pyronin Y staining. Depletion of Mirk by a doxycycline-inducible short hairpin RNA increased the G0 fraction to about 50%, suggesting that Mirk provided some function in G0. Mirk reduced the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in quiescent cultures of SU86.86 cells and of Panc1 cells by increasing transcription of the antioxidant genes ferroxidase, superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), and superoxide dismutase 3 (SOD3). These genes were functional antioxidant genes in pancreatic cancer cells because ectopic expression of SOD2 and ferroxidase in Mirk-depleted cells lowered ROS levels. Quiescent pancreatic cancer cells quickly lost viability when depleted of Mirk because of elevated ROS levels, exhibiting up to 4-fold less colony forming activity and 4-fold less capability for dye exclusion. As a result, reduction of ROS by N-acetyl cysteine led to more viable cells. Mirk also destabilizated cyclin D1 and D3 in quiescent cells. Thus quiescent pancreatic cancer cells depleted of Mirk became less viable because they were damaged by ROS, and had increased levels of G1 cyclins to prime cells to escape quiescence.

Keywords: Mirk, dyrk1B, G0, quiescence, ROS

Introduction

Mirk/Dyrk1B is a member of the Minibrain/dyrk family of serine/threonine kinases (1), (2), (3) which mediate survival and differentiation in certain normal tissues: skeletal muscle (Mirk/dyrk1B) (4), neuronal cells (Dyrk1A) (1), (5), erythropoietic cells (Dyrk3) (6), (7), and sperm (Dyrk4) (8). Mirk/dyrk1B is an unusual kinase in that its expression and abundance varies up to 10-fold during the cell cycle, with the highest levels found in confluent NIH3T3 cells and in post-mitotic myoblasts (9), (4). Furthermore, Mirk helps to maintain non-transformed cells in a quiescent state by increasing levels of the CDK inhibitor p27kip1 which helps to maintain G0/G1 arrest. Mirk phosphorylates p27 at a site which blocks its degradation in quiescent cells (9), (10). Mirk also prevents both non-transformed cells and cancer cells from entering G1 by destabilizing the cyclin D family of G1 cyclins, by phosphorylation at a conserved ubiquitination site which leads to rapid turnover (11), (12). Mirk is expressed in several cancers and has been shown to mediate the clonogenic growth of pancreatic cancer cells and rhabdomyosarcoma cells (13),(14) by an unknown mechanism. In the current study Mirk is shown to mediate the survival of quiescent pancreatic cancer cells accumulated predominately in G0 and early G1 by protecting cells against oxidative stress through increasing transcription of antioxidant genes.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Antibodies were from Santa Cruz. Pancreatic cancer cell lines, and methods were as described (15), (11), (16). SU86.86 86 pancreatic cancer cell pools containing doxycycline-inducible lentiviral constructs were from Amgen and were maintained in tetracycline-negative FBS in the presence of G418. The doxycycline inducible shRNA's were either to Mirk mRNA sequences starting at bp530 or to the non-mammalian luciferase gene. Human MGC verified full length cDNA plasmids for ferroxidase, SOD2 and SOD3 were from Open Biosystems and their labeling and northern analysis were as described (15).

RNA interference and transfections

All synthetic RNAi duplexes were from Invitrogen and were used at 50-100 nM with Lipofectamine 2000 (13). Transfection of Panc1 cells with synthetic RNAi duplexes was over 90%, as assayed by co-transfection with a fluorescent oligonucleotide (BLOCK-IT, Invitrogen).

Flow cytometry

For analysis of DNA content only, cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and then treated with RNase A, before a minimum of 10,000 propidium iodide stained cells were analyzed by the LSR II. For determination of DNA and RNA content to distinguish G0 from G1 cells, two parameter cell cycle analysis was performed on cells fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol and stored at −20°C until staining. Cells were suspended in PBS containing 2 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 (to stain DNA and block DNA staining by Pyronin Y), incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature, Pyronin Y was added at 4 μg/ml to bind to RNA, and cells were placed on ice. Fluorescence of 10,000 cells per sample was measured after 20 min with Hoechst excitation at 355 nm, emission at 400-480 nm, and with Pyronin Y excitation at 561 nm, emission at 570-600 nm.

ROS activity measurement

Cells at 1×105 per 6 well plate were switched to DMEM +0.2% FBS +/- 1 μg/ml doxycycline and culture continued for 2- 4 days. Trypsinized cells were resuspended at 2×105 per ml in 5 μM CM-H2DCFA, made from a fresh stock at 10 mM in dimethylformamide. After 30 min at 37°, cells were resuspended in fresh DMEM, incubated 30 min at 37° and ROS activity levels measured in a Turner BioSystems Modulus fluorometer with filters optimized to detect fluorescein. Data was corrected using cell-free DMEM and for cell number.

Statistics

performed as indicated by the student's paired two-tailed t test. Mean +/- SE shown if SE>5%.

Results

When pancreatic cancer cells accumulate in the G0 quiescent state, Mirk levels are increased several-fold

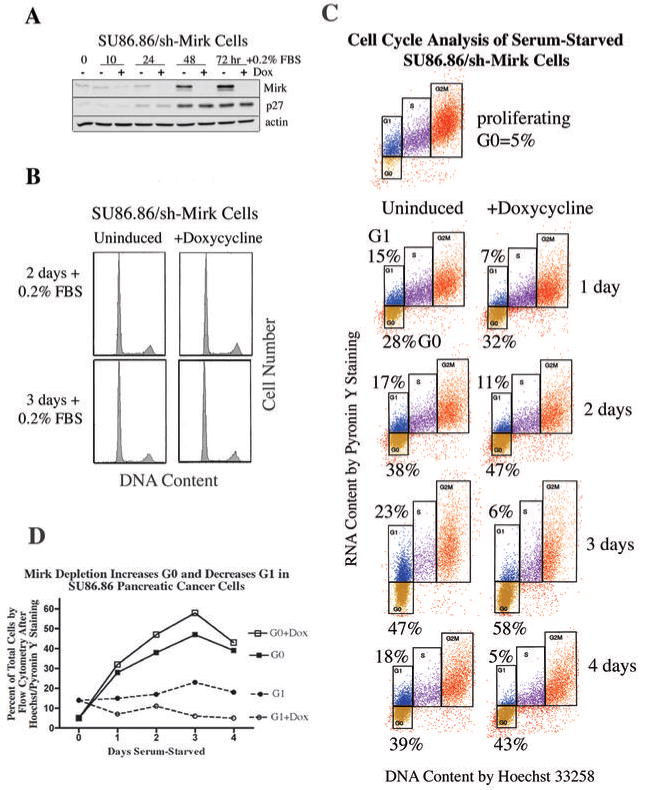

Quiescent tumor cells in G0 are considerably less responsive than cycling cells to chemotherapeutic drugs and radiation and may be one source of recurrent tumors, so the role of Mirk in SU86.86 pancreatic cancer cells in G0 was determined. The SU86.86 line was chosen because it contains an amplified Mirk gene within the 19q13 amplicon (17), and depletion of Mirk in these cells decreased anchorage-independent colony formation (data not shown) and enhanced apoptosis by the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine (13). SU86.86 cells stably bearing a doxycycline-inducible shRNA to the Mirk mRNA (SU86.86/sh-Mirk) were utilized to assess the role of Mirk in G0 cells. Mirk protein levels increased 7-fold in the uninduced cells after culture for 3 days in DMEM supplemented with only 0.2% FBS to inhibit cell cycling (Fig.1A). Parallel analysis of cell cycle position by flow cytometry with propidium iodide staining demonstrated that after 2-3 days about 70% of SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells with high Mirk levels had accumulated predominantly with a 2N DNA content, either in G0 or G1. Induction of the short hairpin RNA directed to the Mirk mRNA prevented any increase in Mirk levels, which were 25-fold lower compared with the uninduced cells, but only slightly decreased the fraction of cells in G0/G1 as assessed by propidium iodide staining for DNA content (mean of 71% to 67%, Fig.1B, Table 1). Thus Mirk is not essential for pancreatic tumor cells to accumulate in a quiescent state. A similar increase in Mirk protein levels with serum-free growth which increased the fraction of G0/G1 cells by flow cytometry was seen in Panc1, Capan1, and Capan2 pancreatic cancer cells (data not shown). The levels of the CDK inhibitor p27kip1, which helps to maintain a G0 arrest, were increased several-fold during culture in low serum medium and this increase was not altered by Mirk depletion (Fig.1A).

Figure 1.

- SU86.86/sh-Mirk pancreatic cancer cells were cultured in DMEM+ 0.2% tetracycline-negative FBS +/- 1 μg/ml doxycycline for 0-3 days, with levels of Mirk, p27kip1 and actin analyzed by western blotting.

- Parallel cultures to panel A were analyzed by flow cytometry after propidium iodide staining.

- Flow cytometry on SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells sequentially stained with Hoechst 33258 for DNA (x-axis) and then Pyronin Y (y-axis) for RNA. Cells were either proliferating in growth medium containing 7% FBS, or serum-starved in medium containing 0.2% FBS +/- doxycycline. G0 (gold, lower boxes) and G1 (blue, upper boxes) cells exhibit 2N DNA, with S phase cells (purple) and G2+M cells (orange). The analysis was performed on the same day with the same gating.

- Cells in G0 and G1 +/- Mirk depletion (Table 1A).

Table 1.

| Table 1A: Cell Cycle Analysis of Doxycycline-inducible SU86.86/sh-Mirk Pancreatic Cancer Cells during Serum-Starvation into a Quiescent State by staining sequentially with Hoechst 33258 for DNA and then Pyronin Y for RNA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | + |

| G0 | G0 | G1 | G1 | S | S | G2+M | G2+M | |

| proliferating | 5 | 14 | 20 | 61 | ||||

| Serum-starved 1 day |

28 | 32 | 15 | 7 | 21 | 22 | 35 | 39 |

| 2 days | 38 | 47 | 17 | 11 | 16 | 14 | 28 | 28 |

| 3 days | 47 | 58 | 23 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 24 | 23 |

| 3 days | 28 | 41 | 30 | 8 | 11 | 15 | 31 | 36 |

| 4 days | 39 | 43 | 18 | 5 | 11 | 15 | 33 | 37 |

| Data from 3 separate experiments. | ||||||||

| Table 1B. Analysis of Doxycycline-inducible SU86.86/sh-Mirk Pancreatic Cancer Cells during Serum-Starvation into a Quiescent State by staining with Propidium Iodide | ||||||||

| Doxycycline | - | + | - | + | - | + | ||

| G0/G1 | G0/G1 | S | S | G2+M | G2+M | |||

| Mean values: 3 days serum starvation | 71 | 67 | 8 | 9 | 21 | 23 | ||

| Mean values: 5-7 days Serum starvation | 66 | 62 | 6 | 8 | 20 | 23 | ||

| SU86.86 pancreatic cancer cells stably expressing a doxycycline inducible short hairpin RNA directed to Mirk mRNA were cultured in DMEM + 0.2% FBS for 1 to 7 days +/- doxycycline. When cells were so maintained in for 5-7 days the values do not equal 100% because of cell death. | ||||||||

Quiescent cells in G0 are characterized by lower levels of RNA than that seen in G1 and S phase cells and were detected by two-parameter analysis by flow cytometry using sequential staining with Hoechst dye to bind DNA and then Pyronin Y to bind to RNA. Proliferating cultures contained 5% of cells in G0, but after 1 day of serum-starvation, 28% of the pancreatic cancer cells were in G0 and this fraction increased to a mean of 38% (+/-4%) between days 2 and 4 (Table 1, Fig.1C). When Mirk was depleted, the fraction of cells in G0 between days 2 and 4 increased further to a mean of 47% (+/-4%). An average 22% increase in the fraction of cells in G0 was seen over the five time points (Fig.1D, Table 1). Thus quiescent SU86.86 pancreatic cancer cells could enter G0 when Mirk was depleted, and more cells did, suggesting that Mirk had functions in G0.

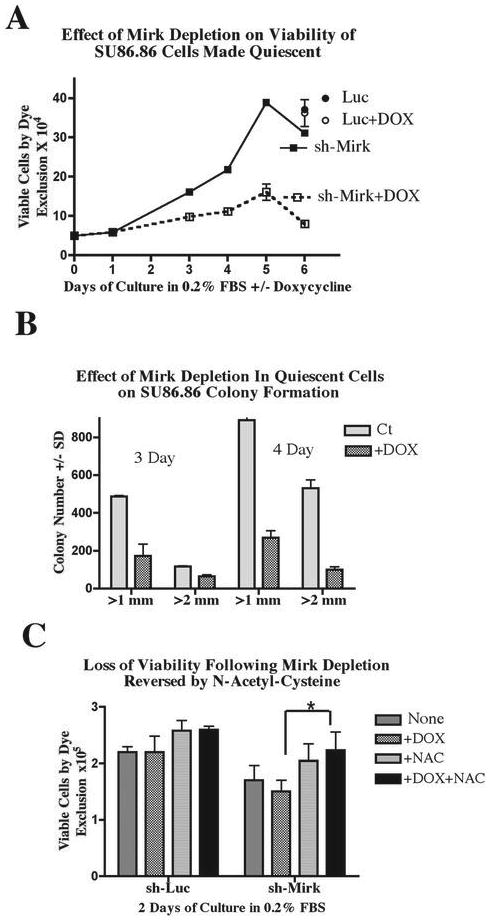

Pancreatic cancer cells maintained in G0 quiescence without Mirk lose viability

When Mirk was depleted in SU86.86/sh-Mirk cultures made quiescent and enriched in G0 cells (Fig.1C) by serum-starvation, cells lost viability as shown by their decreased capacity for trypan blue exclusion (Fig.2A) and their decreased ability to sustain clonogenic growth (Fig.2B). Cultures of SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells depleted of Mirk by the inducible shRNA contained about half as many viable cells after 3 days in low serum medium (Fig.2A) when 47% to 58% of cells were accumulated in G0 (Fig.1C). With continued culture, the control, uninduced cells cycled slowly as the total number of viable cells more than doubled from 3 to 5 days of culture. In contrast, little increase in viable cell number was seen in the Mirk-depleted cultures. After 6 days, 4 times as many viable cells were found in the uninduced cultures compared with the Mirk-depleted ones (Fig.2A). The majority of induced and uninduced cells accumulated in G0 or G1 during serum starvation up to 7 days (Table 1), but cells were continually dying during this period. The number of nonviable, trypan blue positive cells counted on day 4 constituted 23% of the total uninduced cells, but constituted a greater percentage, 41% of total cells, in the Mirk-depleted cultures, when about 40% of both cultures were in G0 (Table 1, Fig.1C). Thus more cell death occurred when cells were maintained in G0 quiescence in the absence of Mirk. The control cells for this study were SU86.86/Luc cells stably expressing an inducible short hairpin to the unexpressed gene luciferase. SU86.86/Luc cells were cultured with or without 1 μg/ml doxycycline for 6 days and their viability assayed by trypan blue exclusion. There was no difference in the number of viable cells between the control and doxycycline-treated SU86.86/Luc cultures (Fig.2A), demonstrating that the loss in cell viability by doxycycline-induced depletion of Mirk was due to loss of Mirk expression, not due to toxicity by doxycycline.

Figure 2.

- Viability by trypan blue exclusion assay: SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells and control SU86.86/luc cells (Luc) were cultured in DMEM+ 0.2% FBS to induce a quiescent state +/- 1 μg/ml doxycycline. Viable trypan blue negative cells were counted by phase microscopy.

- Viability by colony formation assay: SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells cultured for 3 - 4 days to quiescence as in panel A were analyzed for colony formation (Methods) with n=3. One of duplicate experiments shown.

- Viability by trypan blue exclusion assay: SU86.86/sh-Mirk and control SU86.86/luc cells quiescent for 2 days were assayed for viable cells, as in panel A, with the addition of the antioxidant N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) at 1 mM as noted. The shMirk viable cell numbers for +Dox +/-NAC were statistically different, p<0.02. One of duplicate experiments shown.

The viability of the Mirk-depleted quiescent cultures was also determined by assaying their capacity for colony formation. SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells were cultured for 3 or 4 days in medium supplemented with 0.2% FBS to place the majority of control cells and Mirk-depleted cells in either G0 or G1 (Table 1). The cells were then trypsinized, equally diluted and replated in serum-containing growth medium in the absence of doxycycline. Colonies which arose 10 days after plating were counted and displayed by colony size (Fig.2B). Quiescent cells depleted of Mirk gave rise to an average of 33% (+/- 4%) as many colonies as controls. Thus depletion of Mirk in cultures of quiescent pancreatic cancer cells reduced their viability 3 to 4 fold by two different assays.

Mirk mediates pancreatic cancer cell survival by decreasing the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

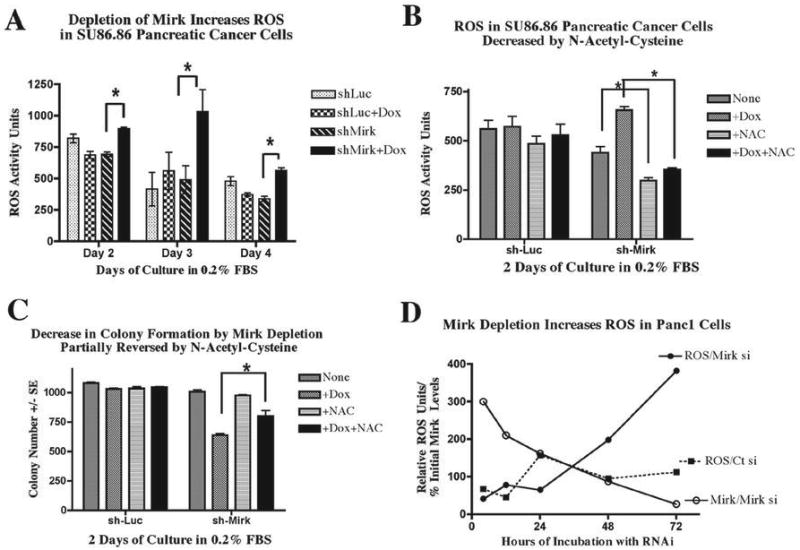

To test the hypothesis that Mirk controlled ROS levels in pancreatic cancers, SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells and control SU86.86/sh-Luc cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 0.2% FBS for 2,3 and 4 days to accumulate cells in G0 and G1. Depletion of Mirk strongly correlated with increased ROS activity over this period by a statistically significant amount (p=0.0488 by student's paired t test), with increases after 2,3 or 4 days of 129%, 210% and 166%, respectively (Fig.3A). The increase in ROS activity was less after 4 days when cell death was evident in the cultures (Fig. 2A). Possibly cells with the highest ROS levels had died at this time point. In contrast, no increase in basal ROS activity was seen at any time point with doxycycline treatment of the control SU86.86/Luc cells (p=0.3776). A similar increase in ROS was seen when the parental SU86.86 cells were depleted of Mirk by transient transfection of RNAi duplexes (data not shown).

Figure 3.

- SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells and control SU86.86/Luc cells were grown in DMEM + 0.2% FBS +/- 1 μg/ml doxycycline. ROS activity was detected with CM-H2DCFA by fluorometer. The values (n=3) +/- doxycycline were statistically different, p=0.0488.

- The antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine blocked the increase in ROS following Mirk depletion. ROS activity in SU86.86/sh-Mirk and control SU86.86/Luc cells after culture for 2 days in DMEM + 0.2% FBS +/- 1 μg/ml doxycycline +/- 0.5 mM N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) was detected with CM-H2DCFA by fluorometer. ROS values (n=3) +/- NAC were statistically different, p<0.001, and representative of duplicate experiments.

- The antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine partially blocked the loss of viability of SU86.86 cells caused by Mirk depletion. SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells and control SU86.69/luc cells were cultured for 2 days in DMEM + 0.2% FBS +/- 1 μg/ml doxycycline and +/- 1 mM N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) to block ROS, and colony number determined (Methods) (n=3). Mirk depletion decreased colony number 40% while NAC restored colony numbers with p<0.001.

- Mirk was depleted in Panc1 pancreatic cancer cells by transfection of RNAi duplexes. The time-course for Mirk depletion performed in parallel is shown as percentage of initial Mirk levels times 3. ROS activity was detected with CM-H2DCFA using flow cytometry.

Elevated ROS levels were shown to be one cause of the loss of viability seen when Mirk was depleted. SU86.86 cells were incubated with the antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) and their viability and their ROS activity were compared with and without depletion of Mirk. Incubation with NAC for 48 hours decreased by about half the ROS levels in both the uninduced and in the doxycycline-induced SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells (Fig.3B), with both reductions statistically significant with p<0.001. The experiment was then repeated and cells were assayed for viability by dye exclusion (Fig.2C) and for their capacity for colony formation (Fig.3C). Addition of NAC to Mirk-depleted quiescent cells led to a 50% increase in viable cell numbers as assayed by dye exclusion, and partially restored clonogenicity to the Mirk-depleted cells (Fig.3C), a statistically significant effect with p<0.001. NAC slightly decreased ROS levels in control SU86.86/sh-Luc cells, and had little effect on their capacity for dye exclusion or colony formation (Fig.2C, 3B+C). Thus toxicity of doxycycline was not the cause of the loss in viability when Mirk was depleted by a doxycycline-inducible construct in SU86.86/shMirk cells.

To assess the generality of these results, Mirk was depleted from another pancreatic cancer cell line, Panc1, by transient transfection of RNAi duplexes directed to a different sequence in the Mirk mRNA than that targeted by the shRNA. Both the shRNA and the synthetic RNAi duplexes greatly reduced Mirk mRNA levels (Fig.3D, data not shown). Parallel time-courses showed that 10-fold Mirk depletion was seen 48 to 72 hours post-transfection, while ROS levels increased at the same time in only the Mirk-depleted cultures. Depletion of Mirk by two different methods in two pancreatic cancer cell lines led to an increase in ROS. Thus one role of Mirk is to maintain the viability of quiescent tumor cells by decreasing ROS levels.

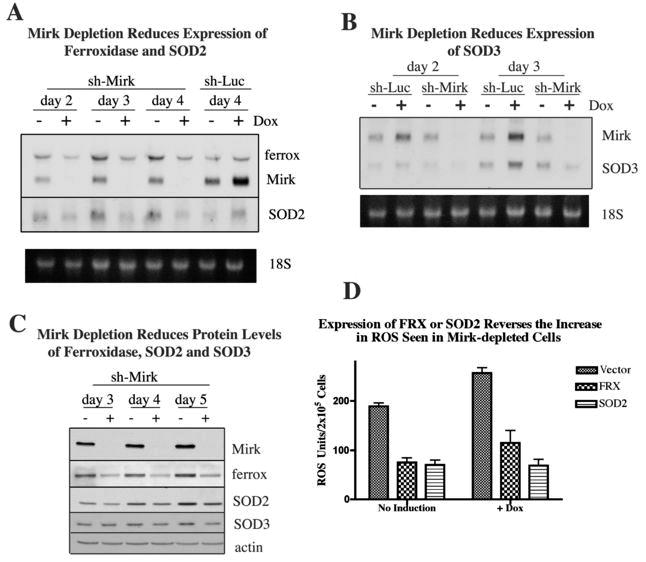

Mirk mediates cell survival by increasing transcription of genes which reduce ROS levels

Since Mirk is a co-activator of several transcription factors (18), (19), (16), (20), possibly Mirk enhanced the survival of pancreatic cancer cells by upregulating expression of genes involved in countering oxidative damage. A microarray screen compared gene expression profiles in Mirk-depleted (via doxycycline-inducible shRNA) SU86.86 pancreatic cancer cells versus uninduced controls. No decrease in expression of anti-apoptotic or DNA repair genes was seen, but decreased expression of several antioxidant genes followed Mirk depletion. The microarray data were confirmed by northern analysis of mRNA levels of ferroxidase, superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), and SOD3 following culture in DMEM supplemented with 0.2% FBS for 2 to 4 days. Mirk levels were decreased over 10-fold by doxycycline-induction of shRNA over this induction period (Fig.4A+B), leading to a 2.5 fold (+/-0.8) mean reduction in ferroxidase mRNA levels and a 3 fold (+/-0.2) mean reduction in SOD2 and SOD3 mRNA levels. Induction of the shRNA to the luciferase gene was used as a control, and surprisingly led to a 2-fold increase in Mirk mRNA levels on days 2, 3 and 4, which correlated with small increases in ferroxidase, SOD2, and SOD3 mRNA levels on these days (Fig.4A,B, data not shown). Thus when mRNA levels of Mirk were reduced, mRNA levels of ferroxidase, SOD2 and SOD3 were also reduced, while small increases in Mirk expression correlated with small increases in expression of these antioxidant genes. These three genes function together to maintain low levels of superoxide and hydroxyl ions. SOD2 and SOD3 detoxify superoxide ions to hydrogen peroxide which is then metabolized to water when its conversion to free hydroxyl ion is blocked by ferroxidase (see Discussion).

Figure 4.

- SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells and control SU86.86/Luc cells were cultured +/- 1 μg/ml doxycycline in DMEM +0.2% FBS. Mirk, ferroxidase and SOD2 mRNA levels were measured by northern blotting. All three genes were probed on the same blot, with the SOD2 results shown from a longer exposure, with the ethidium bromide stained gel shown below.

- SU86.86/sh-Mirk and control SU86.86/Luc cells were cultured +/- doxycycline as in panel A before northern blotting for Mirk and SOD3 mRNA. Genes were probed on the same blot, with the ethidium bromide stained gel shown below.

- SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells were cultured +/- doxycycline as in panel A before Mirk. ferroxidase, SOD2, SOD3 and actin levels were analyzed by western blotting. One of 3 representative experiments shown.

Levels of three antioxidant proteins were determined by western analysis in SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells during culture in DMEM supplemented with 0.2% FBS for 5 days to accumulate cells in a quiescent state. In the control cells with elevated Mirk levels, ferroxidase levels were up to 6–fold higher over Mirk-depleted cells (mean 3.3 fold +/-0.8, n=4). Likewise, levels of SOD2 and SOD3 were on average 1.5 fold (+/-0.1, n=6) higher in uninduced cells compared with Mirk-depleted cells after 3-5 days of culture in low serum medium. As a control, ferroxidase, SOD2, and SOD3 levels were compared in SU86.86/luc cells. No decrease in these proteins were seen after 3-5 days treatment with doxycycline (data not shown).

To confirm that reduction of expression of the antioxidant genes SOD2 and ferroxidase were able to cause the increase in ROS levels seen when Mirk was depleted, the SOD2 and ferroxidase genes were transiently transfected into SU86.86/shMirk cells. Depletion of Mirk for 2 days caused a 36% increase in ROS levels, similar to that seen in earlier experiments (compare Fig.4D with Fig.3). However, expression of either SOD2 or ferroxidase reduced ROS levels over 2-fold in both Mirk-depleted cells and in untreated cells (Fig.4D). Therefore, Mirk upregulates the transcription of antioxidant genes which maintain the viability of pancreatic cancer cells in G0 by reducing ROS levels.

Depletion of Mirk enables quiescent pancreatic cancer cells to increase levels of G1 cyclins

More Mirk-depleted cells than control cells were found in G0, suggesting that Mirk-depleted cells damaged by elevated ROS levels remained longer in G0 (Fig.1D). However, fewer Mirk-depleted cells were found in G1 and more in S (Fig.1C,D, Table 1). Possibly Mirk depletion in quiescent cells led to an increase in the G1 cyclins that are needed to traverse G1 and enter S. Cyclin D isoforms have crucial roles in controlling entry into the cell cycle in pancreatic cancers as the CDK/cyclin D inhibitor p16ink4a is either homozygously deleted, as in SU86.86 cells, or functionally inactivated by mutation. Both cyclins D1 and D3 are overexpressed in pancreatic cancers (21), and were detectable at low levels in quiescent SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells and Panc1 cells. Mirk destabilizes cyclin D1 by phosphorylation and less phosphorylation of endogenous cyclin D1 was seen in Mirk-depleted cultured cells (data not shown). As a result, depletion of Mirk by induced shRNA SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells, or by transfected RNAi duplexes in Panc1 cells, increased cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 levels because of a 2 to 3 fold increase in protein half-life (Figs.5A,B). More cyclin D/CDK complexes phosphorylated the retinoblastoma protein family member p130/Rb2, leading to its slower migration and its reduced capacity to sequester the transcription factor E2F4 (Supplementary Data Fig.1). Genes transcribed by E2F4 allow G0 cells to enter into G1 (22). Therefore, quiescent pancreatic cancer cells became enriched in cyclin D isoforms when depleted of Mirk, so when ribosomal RNA and proteins levels rose enough to enable cells to enter G1, cells were biochemically primed to rapidly transit G1 and enter S.

Figure 5.

- Mirk was depleted in SU86.86/sh-Mirk pancreatic cancer cells +/- doxycycline for 2 days in DMEM + 0.2% FBS. Half-life measurements of cyclin D3 were made by translation arrest with 20 μg/ml cycloheximide. Blots were scanned by laser densitometry and values analyzed by the IP LabGel Program.

- Mirk was depleted in Panc1 pancreatic cancer cells by synthetic duplex RNAi siA or treated with a GC-matched control sequence. Half-life measurements of cyclin D1 were made as in panel A.

- Time-course of SU86.86/sh-Mirk pancreatic cancer cells cultured in DMEM + 0.2% FBS +/- 1 μg/ml doxycycline showed faster induction of cyclin E when Mirk was depleted. Cyclin E normalized to actin was determined by western blotting, n=4. Peak of increase in cyclin D3 at 24 hours (arrow).

- Levels of Mirk, cyclin E, and actin were determined by western blotting in SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells and SU86.86/Luc controls cultured in DMEM+ 0.2% FBS +/- doxycycline.

The model of rapid transit of Mirk depleted cells through G1 was tested by a time-course measurement of the late G1 cyclin, cyclin E. Transcription of cyclin E increases when cyclin D/CDK complexes are active. Control SU86.86/sh-Luc cells and SU86.86/sh-Mirk cells were serum-starved for 3 days to increase Mirk levels and accumulate cells in G0 (Fig.5C,D). In the control SU86.86/Luc cells and uninduced SU86.86/shMirk cells, cyclin E levels remained low for 2 days, then doubled, consistent with a slow transit of G1 (Fig.5C,D). In contrast, in Mirk-depleted cells cyclin E levels rose within the first day and reached a 3-fold higher level by 2-3 days. The more rapid transit of G1 in Mirk-depleted cells led to more cells in S phase after days 3 and 4 of serum-starvation, an average of 14% (+/-1%) compared with 9% (+/-2%) in the controls (Table 1). Thus Mirk-depleted cells accumulated G1 cyclins, priming them to rapidly traverse G1 and enter S phase.

Mirk aids in maintenance of the quiescent state in pancreatic cancers in vivo

Nuclear Ki67 antigen is expressed in all phases of the cell cycle except G0, and was found in only 28% of pancreatic cancer cells in vivo in a recent study (23). Mirk protein was detected by immunohistochemistry in 25 of 28 resected pancreatic cancers (13). Three of these cases were recut and sequential sections analyzed for Mirk expression and for nuclear expression of Ki67. Since individual cells could not be reliably identified on the adjacent slides, all of the cells in the same malignant ducts were counted for Mirk reactivity and for Ki67 nuclear staining. In two cases, almost all of the malignant ductal epithelium was positive for Mirk and negative for Ki67 nuclear staining (0 of 352), (0/140), (case#1, Supple. Fig.2) demonstrating that these quiescent tumor cells expressed Mirk. In another case, a group of closely associated malignant ducts exhibited elevated expression of Mirk and no nuclear Ki67 staining (0/67 cells) while two proliferating lymphocytes directly adjacent exhibited nuclear Ki67 staining (case#2, Supple. Fig.2). In each of three cases pancreatic cancer cells which expressed Mirk protein were quiescent, lacking nuclear expression of Ki67. Thus Mirk is expressed in noncycling pancreatic cancer cells in vivo as well as in cultured pancreatic tumor cells experimentally made quiescent.

Discussion

Mutant K-ras has been implicated in mediating survival in several different types of cancer cells. The kinase Mirk/dyrk1B is activated by oncogenic K-ras in pancreatic cancer cells and mediates their survival (24), at least in part, through lowering ROS levels by increasing transcription of at least three antioxidant genes (this study). Culture of epithelial cells under serum-free conditions can increase their intracellular ROS concentrations (25), (26), while oncogenic ras proteins increase basal ROS levels as well (27). The current study utilized SU86.86 and Panc1 pancreatic cancer cells, both of which exhibited amplified Mirk genes, and which were mutant in their K-ras genes, so would be expected to exhibit elevated ROS levels. Mirk protein levels were found to increase 7-fold in quiescent cultures where the cells had accumulated in G0, and depletion of Mirk in quiescent cells decreased their viability 4-fold. G0 tumor cells were identified by 2N DNA content and lower abundance of RNA than G1 cells and S phase cells by two-parameter flow cytometry. Thus Mirk is an unusual kinase that is most active in resting, quiescent cancer cells and mediates the survival of such cells. Identification of potentially druggable targets in quiescent tumor cells is important because such cells may be one source of recurrent tumors. Quiescent cells have been reported to be relatively resistant to apoptosis induced by DNA damage, nutrient starvation or oxidative stress. Normal diploid fibroblasts carrying the bacterial lacI gene in a lambda shuttle vector have been used to quantitate DNA damage and repair in quiescent and in proliferating cells in primary culture. N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea treatment of such quiescent normal diploid fibroblasts led to less pre-mutagenic damage in the transgene and one-fifth as many mutations, compared with proliferating cells. Quiescent cells were proficient in transcription-coupled repair (28), (29), demonstrating their enhanced survival advantage.

G0 cells comprised about 5-10% of the cells in proliferating pancreatic cancer cell cultures in multiple experiments. Tumor cells can enter a final G0 arrest like myeloid leukemia cells undergoing terminal differentiation (30). Alternatively, tumor cells may be able to enter a G0 period to repair damage occurring from ROS generated by metabolic activity, and then resume cycling. The 4-fold decrease in colony forming ability exhibited by Mirk-depleted SU86.86 cells (Fig.2) suggested that a large fraction of the clonogenic subpopulation of tumor cells were unable to repair ROS-initiated damage in the absence of Mirk in a transient G0 repair period.

ROS are oxygen-containing chemical species with reactive chemical properties, such as hydroxyl radicals which contain an unpaired electron and the free radical superoxide. Cancer cells often exhibit higher levels of ROS than normal cells because of increased metabolism and oncogenic stimulation, so are under increased oxidative stress. Genes which detoxify superoxide (superoxide dismutases 2 and 3) and which prevent the generation of hydroxyl radical (ferroxidase/ceruloplasmin) were upregulated in SU86.86 pancreatic cancer cells through Mirk. These genes work together to reduce ROS. Superoxide dismutases detoxify superoxide resulting in hydrogen peroxide, which in turn can either be metabolized to water or to hydroxyl radical through the Fenton reaction if Fe++ is available. Conversion to hydroxyl radical is blocked by ferroxidase which converts Fe++ to Fe+++. Thus these Mirk-upregulated genes working together increase antioxidant potential while minimizing hydroxyl production.

A second function of Mirk is to block quiescent pancreatic cancer cells from traversing G1 through destabilization of cyclin D1 and cyclin D3. Induced depletion of Mirk may lead tumor cells to enter the cycle because of their elevated levels of G1 cyclins before repairing damage incurred in G0 through elevated ROS levels. Decreasing the viability of quiescent pancreatic cancer cells and priming them for easy entry into the cell cycle by depletion of Mirk or by pharmacological inhibition of Mirk could enhance tumor cell kill by chemotherapeutic drugs or radiation. Of concern is the possibility that tumor cells which retain viability following Mirk depletion could progress into a more aggressive clone.

Loss of Mirk may allow p53 mutant pancreatic cancer cells like the SU86.86 and Panc1 lines used in this study to enter S phase with unrepaired damage. Normal diploid cells have wild-type p53 and thus the p21cip1 G1 checkpoint. Depletion of Mirk in normal diploid cells may only allow the cells to proceed to this G1 checkpoint in response to sublethal damage. Normal diploid fibroblasts exhibited no alteration in survival after 20-fold depletion of Mirk (24). Mirk is not an essential gene because embryonic knockout of Mirk/dyrk1B caused no evident phenotype in mice (31). Unfortunately, this mouse strain was lost due to infection before full characterization (W. Becker, personal communication, 2008). These data suggest that targeting Mirk in pancreatic cancer cells might lead to little damage to normal diploid cells because they exhibit a functioning p53 protein and G1 checkpoint, and so may not require Mirk to block entry into G1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hassan Nahkla, M.D. of this Pathology Department for examining 3 cases of pancreatic cancers for expression of Mirk and Ki67 and to Zhiwei Lai, Ph.D. for assistance in flow cytometry analyses.

Abbreviations

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

supported by NCI 2RO1CA67405 (EF), Research Collaboration Agreement 200614198 from Amgen (EF) and the Jones/Rohner Endowment (EF)

References

- 1.Tejedor F, Zhu X, Kaltenbach E, et al. Minibrain:a new protein kinase family involved in postembryonic neurogenesis in Drosophila. Neuron. 1995;14:287–301. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kentrup H, Becker W, Heukelbach J, et al. Dyrk, a dual specificity protein kinase with unique structural features whose activity is dependent on tyrosine residues between subdomains VII and VIII. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3488–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker W, Weber Y, Wetzel K, Eirmbter K, Tejedor F, Joost HG. Sequence characteristics, subcellular localization and substrate specificity of dyrk-related kinases, a novel family of dual specificity protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25893–902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercer SE, Ewton DZ, Deng X, Lim S, Mazur TR, Friedman E. Mirk/Dyrk1B Mediates Survival during the Differentiation of C2C12 Myoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25788–801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413594200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arron JR, Winslow MM, Polleri A, et al. NFAT dysregulation by increased dosage of DSCR1 and DYRK1A on chromosome 21. Nature. 2006;441:595–600. doi: 10.1038/nature04678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geiger JN, Knudsen GT, Panek L, et al. mDYRK3 kinase is expressed selectively in late erythroid progenitor cells and attenuates colony-forming unit-erythroid development. Blood. 2001;97:901–10. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li K, Zhao S, Karur V, Wojchowski DM. DYRK3 Activation, Engagement of Protein Kinase A/cAMP Response Element-binding Protein, and Modulation of Progenitor Cell Survival. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47052–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sacher F, Moller C, Bone W, Gottwald U, Fritsch M. The expression of the testis-specific Dyrk4 kinase is highly restricted to step 8 spermatids but is not required for male fertility in mice. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2007;267:80–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng X, Mercer SE, Shah S, Ewton DZ, Friedman E. The Cyclin-dependent Kinase Inhibitor p27Kip1 Is Stabilized in G0 by Mirk/dyrk1B Kinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22498–504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Besson A, Gurian-West M, Chen X, Kelly-Spratt KS, Kemp CJ, Roberts JM. A pathway in quiescent cells that controls p27Kip1 stability, subcellular localization, and tumor suppression. Genes Dev. 2006;20:47–64. doi: 10.1101/gad.1384406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zou Y, Ewton D, Deng D, Mercer S, Friedman E. Mirk/dyrk1B Kinase Destabilizes Cyclin D1 by Phosphorylation at Threonine 288. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27790–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi-Yanaga F, Mori J, Matsuzaki E, et al. Involvement of GSK-3beta and DYRK1B in Differentiation-inducing Factor-3-induced Phosphorylation of Cyclin D1 in HeLa Cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38489–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng X, Ewton DZ, Li S, et al. The Kinase Mirk/Dyrk1B Mediates Cell Survival in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4149–58. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercer SE, Ewton DZ, Shah S, Naqvi A, Friedman E. Mirk/Dyrk1b Mediates Cell Survival in Rhabdomyosarcomas. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5143–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng X, Ewton DZ, Pawlikowski B, Maimone M, Friedman E. Mirk/dyrk1B Is a Rho-induced Kinase Active in Skeletal Muscle Differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41347–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306780200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ewton D, Lee K, Deng X, Lim S, Friedman E. Rapid turnover of cell-cycle regulators found in Mirk/dyrk1B transfectants. International Journal of Cancer. 2003;103:21–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuuselo R, Savinainen K, Azorsa DO, et al. Intersex-like (IXL) Is a Cell Survival Regulator in Pancreatic Cancer with 19q13 Amplification. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1943–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim S, Jin K, Friedman E. Mirk Protein Kinase Is Activated by MKK3 and Functions as a Transcriptional Activator of HNF1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25040–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng X, Ewton DZ, Mercer SE, Friedman E. Mirk/dyrk1B Decreases the Nuclear Accumulation of Class II Histone Deacetylases during Skeletal Muscle Differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4894–905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411894200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Groote-Bidlingmaier F, Schmoll D, Orth HM, Joost HG, Becker W, Barthel A. DYRK1 is a co-activator of FKHR (FOXO1a)-dependent glucose-6-phosphatase gene expression. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;300:764–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02914-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Aynati MM, Radulovich N, Ho J, Tsao MS. Overexpression of G1-S Cyclins and Cyclin-Dependent Kinases during Multistage Human Pancreatic Duct Cell Carcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6598–605. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith E, Leone G, Nevins J. Distinct mechanisms control the accumulation of the Rb-related p107 and p130 proteins during cell growth. Cell Growth & Differentiation. 1998;9:297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanton KJ, Sidner RA, Miller GA, et al. Analysis of Ki-67 antigen expression, DNA proliferative fraction, and survival in resected cancer of the pancreas. The American Journal of Surgery. 2003;186:486–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin K, Park SJ, Ewton D, Friedman E. The survival kinase Mirk/dyrk1B is a downstream effector of oncogenic K-ras. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7247–55. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nemoto S, Finkel T. Redox Regulation of Forkhead Proteins Through a p66shc-Dependent Signaling Pathway. Science. 2002;295:2450–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1069004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelicano H, Carney D, Huang P. ROS stress in cancer cells and therapeutic implications. Drug Resistance Updates. 2004;7:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trachootham D, Zhou Y, Zhang H, et al. Selective killing of oncogenically transformed cells through a ROS-mediated mechanism by beta-phenylethyl isothiocyanate. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:241–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bielas JH, Heddle JA. Proliferation is necessary for both repair and mutation in transgenic mouse cells. PNAS. 2000;97:11391–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190330997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bielas JH, Heddle JA. Quiescent murine cell lack global genomic repair but are proficient in transcription-coupled repair. DNA Repair. 2004;3:711–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen M, Yen A. c-Cbl Interacts with CD38 and Promotes Retinoic Acid-Induced Differentiation and G0 Arrest of Human Myeloblastic Leukemia Cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8761–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leder S, Czajkowska H, Maenz B, et al. Alternative splicing variants of the protein kinase DYRK1B exhibit distinct patterns of expression and functional properties. Biochem J. 2003;372:881–8. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]