Abstract

Phenethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC) is a promising cancer chemopreventive agent but the mechanism of its anticancer effect is not fully understood. We now demonstrate, for the first time, that PEITC treatment triggers Atg5-dependent autophagic and apoptotic cell death in human prostate cancer cells. Exposure of PC-3 (androgen-independent, p53 null) and LNCaP (androgen-responsive, wild-type p53) human prostate cancer cells to PEITC resulted in several specific features characteristic of autophagy including appearance of membranous vacuoles, formation of acidic vesicular organelles, and cleavage and recruitment of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) to autophagosomes. A normal human prostate epithelial cell line (PrEC) was markedly more resistant towards PEITC-mediated cleavage and recruitment of LC3 compared with prostate cancer cells. Even though PEITC treatment suppressed activating phosphorylations of Akt and mTOR, which are implicated in regulation of autophagy by different stimuli, processing and recruitment of LC3 was only partially/marginally reversed by ectopic expression of constitutively active Akt or overexpression of mTOR positive regulator Rheb. The PEITC-mediated apoptotic DNA fragmentation was significantly attenuated in the presence of a pharmacological inhibitor of autophagy (3-methyl adenine). Transient transfection of LNCaP and PC-3 cells with Atg5-specific siRNA conferred significant protection against PEITC-mediated autophagy as well as apoptotic DNA fragmentation. Xenograft model using PC-3 cells and C. elegans expressing lgg-1:GFP fusion protein provided evidence for occurrence of PEITC-induced autophagy in vivo. In conclusion, the present study indicates that Atg5 plays an important role in regulation of PEITC-induced autophagic and apoptotic cell death.

Keywords: Phenethyl isothiocyanate, Autophagy, Chemoprevention

Introduction

Molecular basis for onset and progression of prostate cancer is not fully understood (1) but this malignancy continues to be a leading cause of cancer related deaths among men in the United States. Prostate cancer is usually diagnosed in the sixth and seventh decades of life providing a large window of opportunity for intervention to prevent or slow disease progression. Therefore, identification and preclinical/clinical development of novel agents that are non-toxic but can delay onset and/or progression of human prostate cancer is highly desirable. Epidemiological studies have indicated that dietary intake of cruciferous vegetables may lower the risk of different types of malignancies including cancer of the prostate (2,3). Anticarcinogenic effect of cruciferous vegetables is attributed to organic isothiocyanates (ITC), which are released upon processing (cutting or chewing) of these vegetables (4,5). Phenethyl-ITC (PEITC) is one such naturally-occurring ITC compound that has received increasing attention due to its cancer chemopreventive effects. For example, PEITC is a potent inhibitor of pulmonary tumorigenesis in rats induced by tobacco-specific carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (6). Prevention of chemical carcinogenesis by PEITC has also been observed against diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocellular adenomas in C3H mice, and N-nitrosobenzylmethylamine-induced esophageal cancer in rats (7,8). Dietary N-acetylcysteine conjugate of PEITC during the post-initiation phase inhibited benzo[a]pyrene-induced lung adenoma multiplicity in mice (9).

More recent studies have revealed that PEITC treatment suppresses growth of prostate cancer cells in culture and in vivo (10-16). The mechanism of antiproliferative effect of PEITC is not fully understood but known cellular responses to this promising natural product in cultured cancer cells include activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinases and extracellular signal-regulated kinases, activation of G2-M phase checkpoint, apoptosis induction, suppression of nuclear factor-κB-regulated gene expression, inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling, repression of androgen receptor expression, and inhibition of cap-dependent translation (10-19). We have also shown previously that PEITC treatment suppresses angiogenesis in vitro and ex vivo at pharmacologically relevant concentrations in association with inhibition of serine-threonine kinase Akt (20).

The Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway has assumed a central role in regulation of autophagy, which is an evolutionarily conserved and dynamic process for bulk-degradation of cellular macromolecules and organelles (21-23). Because PEITC treatment inhibits Akt activity in human prostate cancer cells (17,20), the present study was designed to address the question of whether anticancer effect of PEITC is mediated by autophagic cell death. We now demonstrate that PEITC treatment causes Atg5-dependent autophagic as well as apoptotic cell death in human prostate cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

PEITC (purity >99%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Cell culture reagents and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Life Technologies; 3-methyl adenine (3-MA) and acridine orange were from Sigma-Aldrich; rapamycin was from Calbiochem; and a kit for quantification of cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragmentation was purchased from Roche Diagnostics. Antibody against microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) was from MBL and the antibodies against cleaved caspase-3, Atg5, phospho-(S473)-Akt, total Akt, phospho-(S2448)-mTOR, phospho-(T389)-p70s6k, total p70s6k, and Rheb were from Cell Signaling. The antibody against total mTOR was from Calbiochem.

Cell lines

The LNCaP and PC-3 cell lines were procured from ATCC. Monolayer culture of LNCaP cells was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 0.2% glucose, 10% (v/v) FBS, and antibiotics. PC-3 cells were cultured in F-12K Nutrient Mixture supplemented with 7% non-heat inactivated FBS and antibiotics. Normal human prostate epithelial cell line PrEC was purchased from Clonetics and maintained in PrEBM (Cambrex). Stock solution of PEITC was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted with medium for cellular studies and with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for the in vivo experiment. Final concentration of DMSO was <0.1% for cellular studies and 0.1% for the in vivo experiment.

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy was performed as described by us previously (24). Briefly, LNCaP or PC-3 cells (2×105) were seeded in six-well plates and allowed to attach by overnight incubation. The cells were treated with either DMSO (final concentration <0.1%) or 5 μmol/L PEITC for 6 or 9 h at 37°C. Cells were fixed in ice-cold 2.5% electron microscopy grade glutaraldehyde (in 0.1 mol/L PBS, pH 7.3), rinsed with PBS, post fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide with 0.1% potassium ferricyanide, dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol (30-90%), and embedded in Epon. Semi thin sections (300 nm) were cut using a Reichart Ultracut, stained with 0.5% toluidine blue, and examined under a light microscope. Ultra thin sections (65 nm) were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate and examined using JEOL 1210 transmission electron microscope at 5,000× and 30,000× magnifications.

Detection of acidic vesicular organelles (AVOs)

Cells (1×105) were plated on coverslips in 12-well plates and allowed to attach by overnight incubation. Following treatment with DMSO (control) or PEITC, cells were stained with 1 μg/mL acridine orange in PBS for 15 min, washed with PBS, and examined under a Leica fluorescence microscope at 100× magnification.

Immunofluorescence microscopy for LC3 localization

Cells (1×105) were grown on coverslips in 12-well plates and allowed to attach by overnight incubation. Cells were then exposed to the desired concentration of PEITC or DMSO (control) for specified time periods at 37°C. The cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. The cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and blocked with BSA buffer (PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.15% glycine) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then treated with the anti-LC3 antibody (1:50 dilution in BSA buffer) for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubation with 2 μg/mL Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells with punctate pattern of LC3 localization were visualized under a Leica fluorescence microscope.

Immunoblotting

Cells were treated with the desired concentrations of PEITC or DMSO (control) for specified time periods and lysed as described by us previously (25). Lysate proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membrane. Immunoblotting was performed as described by us previously (24,25).

Transient transfection

PC-3 or LNCaP cells (1×105) were plated in 6-well plates, allowed to attach, and transiently transfected with pCMV6 vector encoding constitutively active Akt-1 (kindly provided by Dr. Daniel Altschuler, University of Pittsburgh, PA), pcDNA3.1 vector encoding Rheb or corresponding empty vector using Fugene6 transfection regent. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were treated with DMSO (control) or 5 μmol/L PEITC for 9 h. The cells were then processed for immunofluorescence microscopy for LC3 or immunoblotting as described above.

RNA interference of Atg5

PC-3 or LNCaP cells (105 in 6-well plates) were transfected at 30-50% confluency with either 100 nmol/L Atg5-targeted siRNA (pool of 3 target-specific 20-25nt siRNAs; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or a control non-specific siRNA (Qiagen). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were exposed to 5 μmol/L PEITC or DMSO and the incubation was continued for an additional 9 h. Cells were then collected and processed for immunoblotting of Atg5, LC3 and caspase-3, analysis of cytoplasmic histone-associated apoptotic DNA fragmentation or immunofluorescence microscopy for LC3 localization.

Xenograft study

Male nude mice (6-8 weeks old) were divided into two groups of five mice per group. The experimental mice were gavaged with 9 μmol PEITC in 0.1 mL PBS containing 0.1% DMSO five times per week, whereas the control mice received 0.1 mL vehicle. Exponentially growing PC-3 cells (3×106) were injected subcutaneously onto the right flank of each mouse above the hind limb. Treatment was started on the day of tumor cell injection and continued until the termination of the experiment (38 days after tumor cell injection). Tumor volume was measured as described by us previously (26). Tumor tissues were dissected and used for immunohistochemistry or immunoblotting. A portion of tumor tissue from control and PEITC-treated mice was fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4-5 μm thickness. Apoptotic bodies in tumor sections were visualized by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay using ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis kit (Chemicon International) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Representative tumor sections from control and PEITC-treated mice were fixed in acetone for 10 min at 4°C. After endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min, the sections were treated with normal serum for 20 min. The sections were then incubated with anti-LC3 antibody (1:100 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature, washed with Tris-buffered saline, and treated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG for 30 min at room temperature. Characteristic brown color was developed by incubation with 3,3-diaminobenzidine. At least three non-overlapping images from each tissue section were captured using a camera mounted onto the microscope.

Assessment of autophagy in C. elegans

The DA2123 strain (adIs2122[lgg-1:GFP rol-6(df)]) was generously provided by Dr. Chanhee Kang (University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX). Adult worms were transferred to plates spotted with PEITC (10 or 25 μmol/L) or DMSO (control). The plates were incubated at 20°C overnight. The worms were mounted in M9 medium containing 10 mmol/L sodium azide and photographed using an Olympus BX51 upright microscope at 40× objective lens magnification.

Results

PEITC treatment caused autophagy in prostate cancer cells

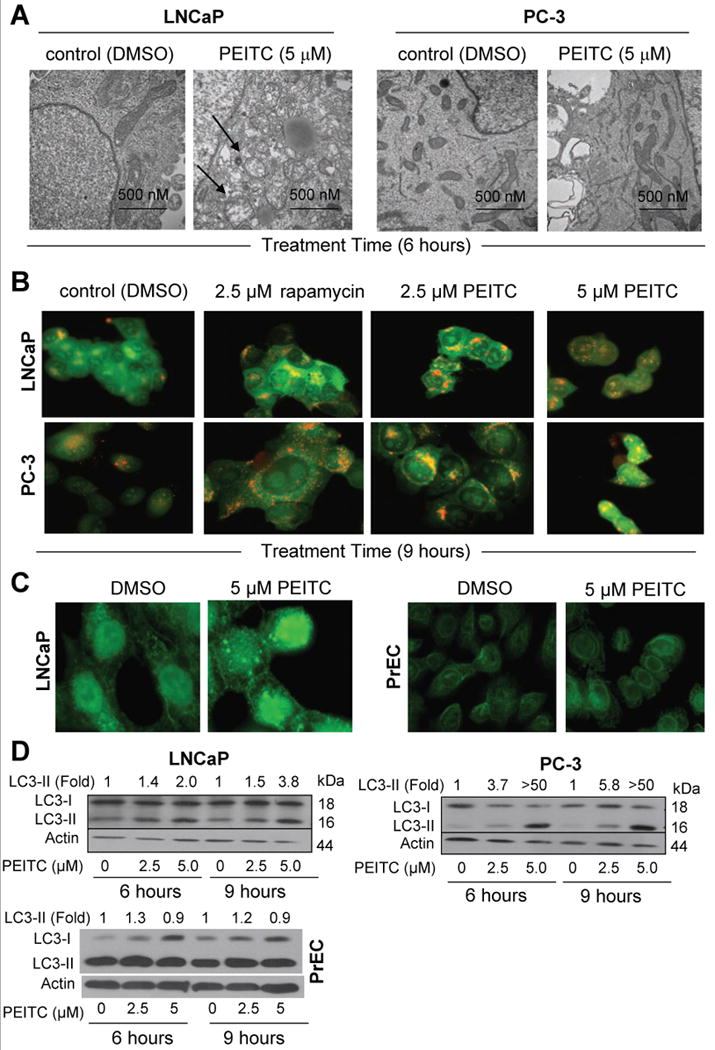

Fig. 1A depicts effect of PEITC treatment on ultrastructures of LNCaP and PC-3 cells. The DMSO-treated control LNCaP and PC-3 cells exhibited normal complement of healthy looking mitochondria. Exposure of LNCaP and PC-3 cells to 5 μmol/L PEITC for 6 h (Fig. 1A) or 9 h (data not shown) resulted in appearance of membranous vacuoles resembling autophagosomes (identified by arrows in Fig. 1A), which were rare in DMSO-treated controls. We confirmed autophagic response to PEITC by analysis of AVOs and processing and recruitment of LC3, which are hallmarks of autophagy (27-29). As can be seen in Fig. 1B, the DMSO-treated control LNCaP and PC-3 cells primarily exhibited green fluorescence. On the other hand, treatment of LNCaP and PC-3 cells with rapamycin (positive control) and PEITC resulted in formation of yellow-orange AVOs. The LC3 protein (18 kDa) is cleaved by autophagic stimuli to a 16 kDa intermediate (LC3-II) that localizes to the autophagosomes (29). Recruitment of LC3-II to the autophagosomes is characterized by punctate pattern of its localization. The DMSO-treated control LNCaP cells (9 h treatment) exhibited diffuse and weak LC3-associated green fluorescence (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, the LNCaP cells treated for 9 h with 5 μmol/L PEITC exhibited punctate pattern of LC3 immunostaining (Fig. 1C). A marked increase in fraction of cells with punctate pattern of LC3 over DMSO-treated control was also observed in LNCaP and PC-3 cells treated for 6 h with 2.5 and 5 μmol/L PEITC (results not shown). Punctate pattern of LC3 localization was not readily apparent by 5 μmol/L PEITC treatment for 6 h (Fig. 1C) or 9 h (results not shown) in a normal prostate epithelial cell line PrEC. Treatment of LNCaP and PC-3 cells with 2.5 and 5 μmol/L PEITC for 6 and 9 h resulted in cleavage of LC3 (Fig. 1D). The control PrEC cells (DMSO-treated) exhibited higher levels of basal cleaved LC3. The PEITC-mediated cleavage of LC3 was much less pronounced in the PrEC cell line compared with prostate cancer cells (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these observations indicated that PEITC treatment caused autophagy in human prostate cancer cells.

Fig. 1.

A, representative transmission electron micrographs depicting ultrastructures of LNCaP and PC-3 cells treated with DMSO (control) or 5 μmol/L PEITC for 6 h (30,000× magnification). B, acridine orange staining in LNCaP and PC-3 cells treated with DMSO, 2.5 μmol/L rapamycin (positive control), and 2.5 or 5 μmol/L PEITC for 9 h. C, fluorescence microscopic analysis for punctate pattern of LC3 in LNCaP cells (9 h treatment) and PrEC normal prostate epithelial cells (6 h treatment) treated with DMSO or 5 μmol/L PEITC. D, immunoblotting for LC3 using lysates from LNCaP, PC-3, and PrEC cells treated for 6 or 9 h with DMSO or the indicated concentrations of PEITC. Densitometric quantitation for cleaved LC3-II relative to DMSO-treated control is shown on top of the immunoreactive band.

PEITC-mediated autophagy correlated with suppression of activating phosphorylations of Akt and mTOR

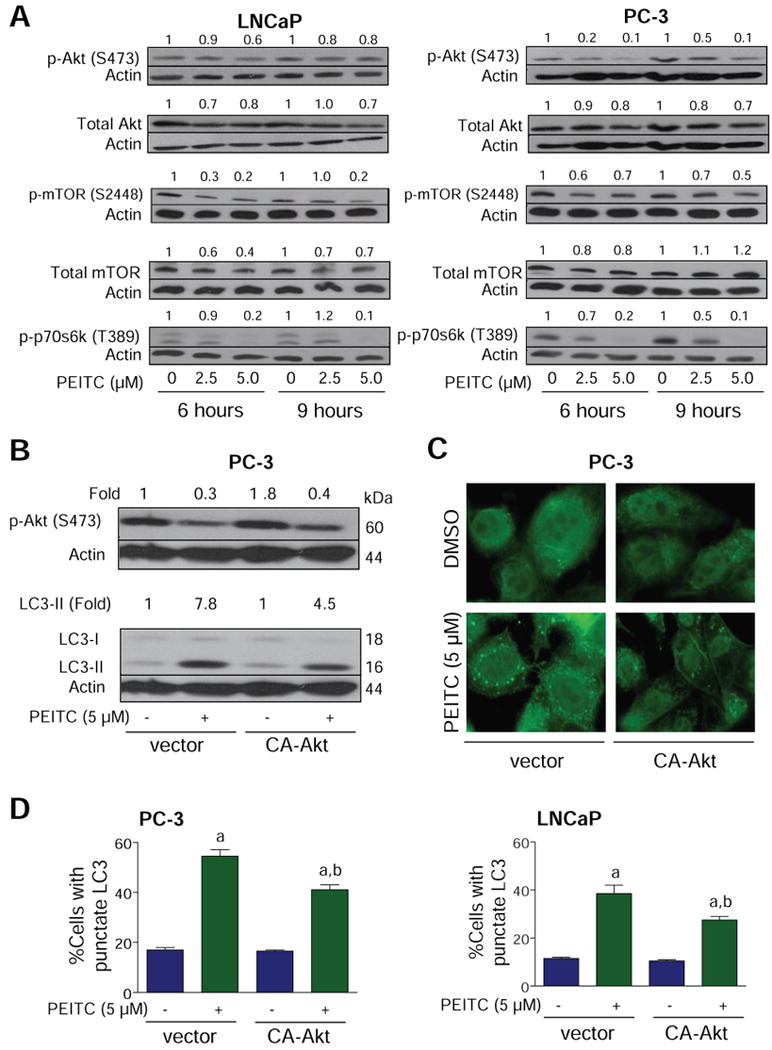

The protein kinase mTOR has emerged as a key negative regulator of autophagy (21-23,28). The activity of mTOR is regulated by Akt-mediated phosphorylation of tuberin (30). To gain insight into the mechanism of PEITC-mediated autophagy in our model, initially we determined the effect of PEITC treatment on activating phosphorylations of Akt (S473) and mTOR (S2448) using LNCaP and PC-3 cells (Fig. 2A). We found that PEITC treatment decreased S473 phosphorylation of Akt in both LNCaP and PC-3 cells; albeit more efficiently in the PC-3 cell line (Fig. 2A). The level of total Akt protein was only modestly decreased (20-30% decrease compared with control) upon treatment of LNCaP and PC-3 cells with PEITC. The levels of S2448-phosphorylated mTOR and phosphorylation of mTOR downstream target p70s6k (T389) were also decreased upon treatment of LNCaP and PC-3 cells with PEITC (Fig. 2A). The PEITC treatment decreased the level of mTOR protein in the LNCaP but not in the PC-3 cell line.

Fig. 2.

A, immunoblotting for phospho-(S473)-Akt, total Akt, phospho-(S2448)-mTOR, total mTOR, and phospho-(T389)-p70s6k using lysates from LNCaP or PC-3 cells treated with DMSO or 2.5 and 5 μmol/L PEITC for 6 or 9 h. B, immunoblotting for phospho-(S473)-Akt and LC3 using lysates from PC-3 cells transiently transfected with the empty-vector or vector encoding CA-Akt and treated with DMSO or 5 μmol/L PEITC for 9 h. Densitometric quantitation relative to DMSO-treated control is shown on top of the immunoreactive band. C, immunofluorescence microscopy for analysis of punctate pattern of LC3 localization in PC-3 cells transiently transfected with the vector encoding CA-Akt or empty-vector and treated with DMSO (control) or 5 μmol/L PEITC for 9 h. D, percentage of cells with punctate LC3 in PC-3 or LNCaP cultures transiently transfected with the empty-vector or vector encoding CA-Akt and treated with DMSO (control) or 5 μmol/L PEITC for 9 h. Columns, mean (n= 3); bars, SE. Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with acorresponding DMSO-treated control and bPEITC-treated empty-vector transfected cells by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. Each experiment was repeated twice and the results were comparable.

To determine functional significance of Akt suppression in autophagic response to PEITC, we determined the effect of ectopic expression of constitutively active Akt (CA-Akt) on PEITC-mediated cleavage and recruitment of LC3 using PC-3 and LNCaP cells. Transient transfection of PC-3 cells with 3 μg CA-Akt plasmid DNA resulted in about 1.8-fold increase in the levels of S473-phosphorylated Akt relative to empty-vector transfected control cells (Fig. 2B). The PEITC-mediated cleavage of LC3 was approximately 1.7-fold higher in the empty-vector transfected control cells compared with CA-Akt overexpressing cells (Fig. 2B). Overexpression of CA-Akt also conferred partial protection against PEITC-mediated increase in fraction of cells with punctate LC3 over DMSO-treated control in both PC-3 and LNCaP cell lines (Fig. 2C,D).

PEITC-induced autophagy was marginally affected by overexpression of mTOR regulator Rheb

Because CA-Akt overexpression resulted in only partial protection against PEITC-induced autophagy we carried out additional experiments involving ectopic expression of Rheb to further define the role of mTOR in autophagic response to PEITC. The Rheb activates mTOR by antagonizing its endogenous inhibitor FKBP38 (31). Ectopic expression of Rheb in PC-3 cells resulted in activation of mTOR as evidenced by about 3.1-fold increase in T389 phosphorylation of its downstream target p70s6k (supplemental Fig. S1). The Rheb-mediated activation of mTOR conferred marginal protection against PEITC-mediated cleavage of LC3 (Fig. S1). These results indicate that suppression of Akt/mTOR cannot fully explain PEITC-mediated autophagy.

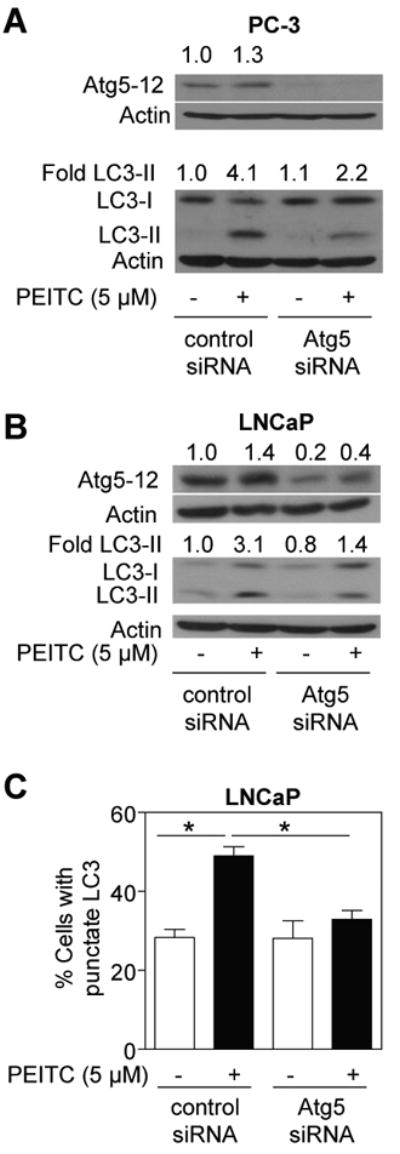

Atg5 knockdown conferred significant protection against PEITC-mediated autophagy

Atg5 is required for formation of autophagosomes and Atg5-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells display significantly diminished number of autophagic vesicles (32). Treatment of control non-specific siRNA transfected PC-3 cells with 5 μmol/L PEITC for 9 h resulted in modest induction of Atg5-12 complex (Fig. 3A). Atg5-12 was not detectable in PC-3 cells transiently transfected with a pool of 3 Atg5-targeted siRNA confirming knockdown of this protein (Fig. 3A). The cleavage of LC3 resulting from a 9 h exposure to 5 μmol/L PEITC was suppressed by about 50% in PC-3 cells with knockdown of Atg5 protein (Fig. 3A). The level of Atg5 was reduced by about 80% in LNCaP cells transiently transfected with the Atg5-targeted siRNA compared with non-specific siRNA transfected LNCaP cells (Fig. 3B). The PEITC-mediated cleavage of LC3 was about 2.2-fold higher in non-specific siRNA transfected LNCaP cells than in the LNCaP cells transfected with the Atg5-specific siRNA (Fig. 3B). In addition, PEITC treatment (5 μmol/L, 9 h) caused a significant increase in fraction of cells with punctate LC3 over DMSO-treated control in control siRNA transfected cells, which was not observed in cells transfected with the Atg5-targeted siRNA (Fig. 3C). Together, these results indicated that the PEITC-induced autophagy was regulated by Atg5.

Fig. 3.

Immunoblotting for Atg5-12 and LC3 using lysates from (A) PC-3 cells and (B) LNCaP cells transiently transfected with a control non-specific siRNA or a pool of 3 Atg5-targeted siRNA and treated with DMSO or 5 μmol/L PEITC for 9 h. Densitometric quantitation relative to DMSO-treated non-specific siRNA transfected cells is shown on top of the immunoreactive band. C, percentage of cells with punctate LC3 in LNCaP cells transiently transfected with a control non-specific siRNA or Atg5-targeted siRNA and treated with DMSO (control) or 5 μmol/L PEITC for 9 h. *Significantly different (P<0.05) between the indicated groups by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test. Each experiment was repeated twice and the results were comparable.

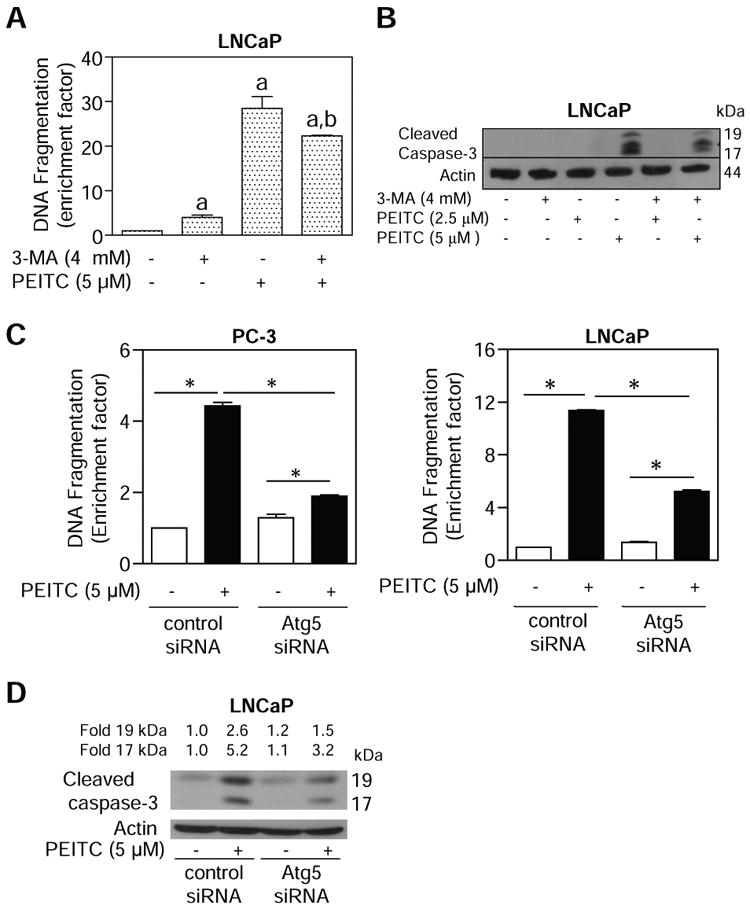

Autophagy was not a protective mechanism against PEITC-induced apoptosis

Autophagy represents a protective mechanism against apoptotic cell death under starvation as well as contributes to resistance against therapy-induced apoptosis in cancer cells (21,22,33-35). At the same time, autophagy has been suggested to be a form of cell death, referred to as type II cell death, distinct from apoptosis (type I cell death) for various antineoplastic agents (36,37). We proceeded to determine the role of autophagy in growth suppression and apoptosis induction by PEITC using autophagy inhibitor 3-MA. The cytoplasmic histone-associated apoptotic DNA fragmentation, which is a widely-accepted technique for quantitation of apoptotic cell death, resulting from exposure of LNCaP (Fig. 4A) and PC-3 (results not shown) to 5 μmol/L PEITC for 16 h was partially but statistically significantly attenuated in the presence of 3-MA. Consistent with these results, the 3-MA treatment conferred partial yet marked protection against PEITC-mediated cleavage of procaspase-3 in LNCaP (Fig. 4B) and PC-3 cells (results not shown). Together these results indicated that PEITC can trigger both apoptosis (type I cell death) and autophagy (type II cell death) in prostate cancer cells.

Fig. 4.

A, quantitation of cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragmentation in LNCaP cells following 16 h treatment with 5 μmol/L PEITC in the absence or presence of 4 mmol/L 3-MA (2 h pre-treatment). Columns, mean (n=3); bars, SE. Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with aDMSO-treated control and bPEITC alone treatment group by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. B, immunoblotting for cleaved caspase-3 using lysates from LNCaP cells treated for 16 h with 2.5 or 5 μmol/L PEITC in the absence or presence of 4 mmol/L 3-MA (2 h pre-treatment). C, cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragmentation in PC-3 (left panel) and LNCaP cells (right panel) transiently transfected with a control non-specific siRNA or a pool of 3 Atg5-targeted siRNA and treated with DMSO (control) or 5 μmol/L PEITC for 9 h. Columns, mean (n=3); bars, SE. *Significantly different (P<0.05) between the indicated groups by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test. D, immunoblotting for cleaved caspase-3 using lysates from LNCaP cells transiently transfected with a control non-specific siRNA or a pool of 3 Atg5-targeted siRNA and treated with DMSO (control) or 5 μmol/L PEITC for 9 h. Each experiment was repeated at least twice and the results were comparable.

To further define the relationship between autophagy and apoptosis in our model, we determined the effect of Atg5 knockdown on PEITC-mediated apoptosis. Consistent with the results using 3-MA (Fig. 4A,B), the cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragmentation (Fig. 4C) and cleavage of procaspase-3 (Fig. 4D) resulting from PEITC exposure (5 μmol/L, 9 h) was significantly attenuated by knockdown of Atg5 protein level in both PC-3 and LNCaP cells.

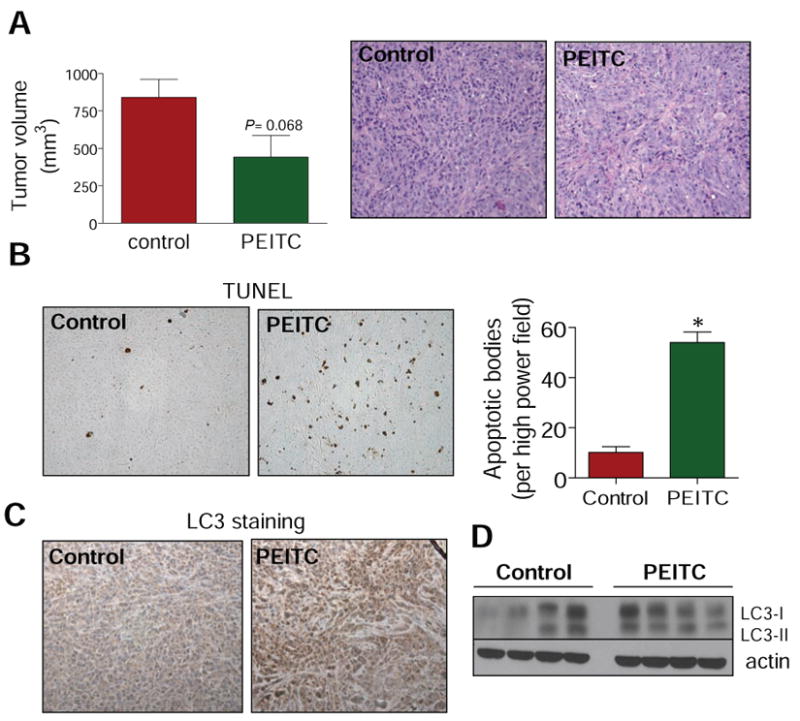

Oral administration of PEITC inhibited PC-3 xenograft growth in association with increased apoptosis and LC3 cleavage in the tumor

We designed animal experiments to test whether PEITC treatment caused autophagy in vivo. The average tumor volume on the day of sacrifice (38 days after tumor cell implantation) in mice gavaged with 9 μmol PEITC was lower by about 48% compared with the vehicle-treated control mice (Fig. 5A). The body weights of the control and PEITC-treated mice did not differ significantly throughout the experimental protocol (results not shown). The H&E staining revealed a marked decrease in nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio in the tumors from PEITC-treated mice relative to control tumors indicating suppression of cell proliferation by PEITC administration (Fig. 5A, right panel). The fraction of brown-color TUNEL-positive apoptotic bodies was statistically significantly higher in tumor sections from PEITC-treated mice compared with control tumors (Fig. 5B). Moreover, the tumors from PEITC-treated mice exhibited increased expression (Fig. 5C) as well as cleavage of LC3 (Fig. 5D). For example, cleaved LC3-II protein was detectable in each tumor sample from the PEITC treatment group but not in each tumor from control mice (Fig. 5D). These results indicated that the PEITC-mediated suppression of PC-3 xenograft growth in vivo was accompanied by apoptosis as well as autophagy.

Fig. 5.

A, tumor volume in vehicle-treated control mice and PEITC-treated mice. Columns, mean (n= 5); bars, SE. Right panel, H&E staining in representative tumor section of a vehicle-treated control mouse and tumor section of a PEITC-treated mouse. B, visualization of TUNEL-positive apoptotic bodies in representative tumor section of a vehicle-treated control mouse and tumor section of a PEITC-treated mouse. Right panel, quantitation of TUNEL-positive apoptotic bodies in tumor sections from control mice and PEITC-treated mice. Columns, mean (n= 3); bars, SE. *Significantly different (P<0.05) compared with control by t-test. C, LC3 expression in representative tumor section of a vehicle-treated control mouse and tumor section of a PEITC-treated mouse. D, immunoblotting for LC3 using tumor supernatants from four different mice of both vehicle-treated control and PEITC-treated groups.

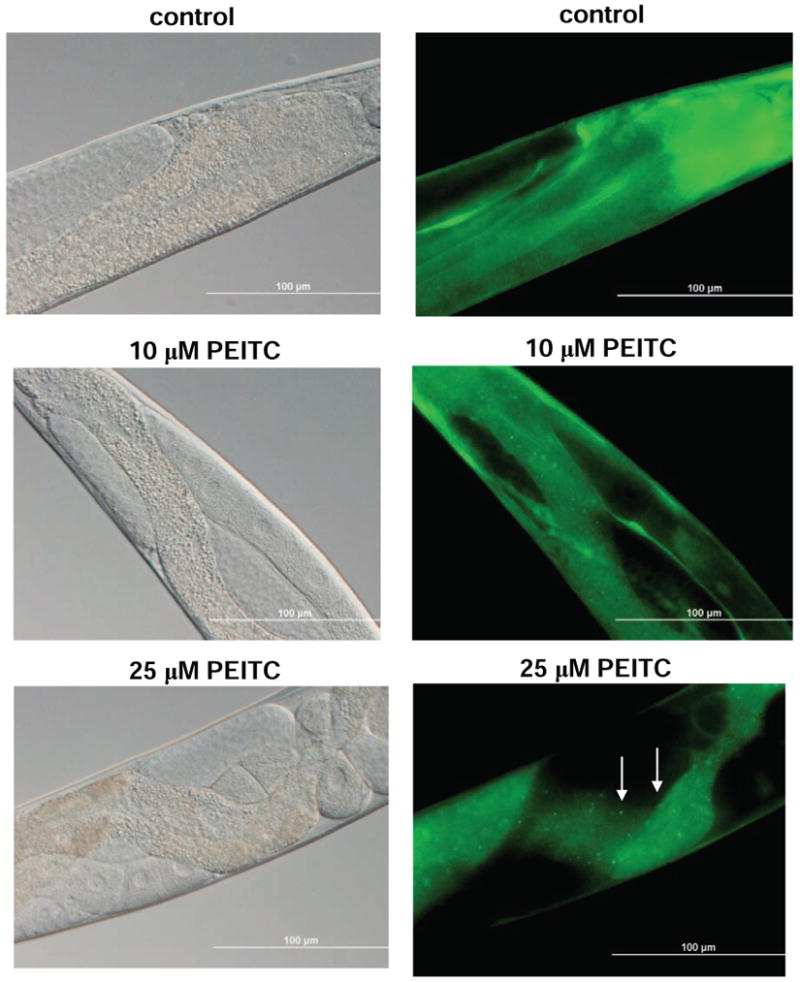

PEITC treatment caused autophagy in C. elegans

To test whether PEITC treatment caused autophagy in an intact organism, we treated the adult nematode C. elegans with PEITC for 24 h and monitored autophagy by following the cellular localization of the lgg-1:GFP fusion protein expressed by the DA2123 strain (38). The lgg-1 is the worm ortholog of yeast Apg8p and mammalian LC3. The lgg-1:GFP fusion protein has been shown to undergo redistribution from diffuse cytoplasmic localization to form punctate foci representing preautophagosomal and autophagosomal structures (39). Previous work has shown redistribution of lgg-1:GFP in response to starvation, caloric restriction, and reductions in daf-2 insulin/IGF-1 receptor signaling (38-40). As can be seen in Fig. 6, treatment of DA2123 with either 10 or 25 μmol/L PEITC resulted in the formation of punctate lgg-1:GFP foci in the intestine of worm in contrast to the diffuse GFP expression seen in control worms. Results in C. elegans provided added in vivo evidence for autophagy induction by PEITC in an intact organism.

Fig. 6.

Representative bright field (left) and fluorescence (right) images showing cellular localization of lgg-1:GFP in intestinal cells of control (DMSO-treated) and PEITC-fed worms. In contrast to controls, the worms fed 10 or 25 μmol/L PEITC for 24 h exhibited redistribution of lgg-1:GFP from a diffuse cytoplasmic pattern to punctate foci representing the pre- and autophagosomal structures (marked by arrows). Images were captured at 40× objective lens magnification. Bars, 100 μm.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that dietary cancer chemopreventive agent PEITC causes autophagy in cultured human prostate cancer cells. Furthermore, oral administration of PEITC inhibits growth of PC-3 xenograft in vivo in association with induction and cleavage of LC3. The autophagic response to PEITC is rapid and evident at low micromolar concentrations. The PEITC concentrations required to elicit autophagic response in cultured prostate cancer cells (2.5-5 μmol/L) and in PC-3 xenograft in vivo (9 μmol PEITC/day) are well within the range that can be generated through dietary intake of cruciferous vegetables (41,42). We also found that a normal prostate epithelial cell line (PrEC) is markedly more resistant to PEITC-mediated cleavage and recruitment of LC3. Recent studies have pointed towards an important role of p53 tumor suppressor in regulation of autophagy (43). Our data suggest that p53 is not necessary for PEITC-induced autophagy because this response is observed in both wild-type p53 expressing LNCaP cell line and p53-null PC-3 cells.

Molecular mechanism for autophagy induction in mammalian cells is still not fully understood but at least 30 autophagy-related genes (ATG) have been identified in yeast (44). The mTOR has emerged as a key negative regulator of autophagy in yeast and possibly in mammalian cells (21-23,45). Results of the present study indicate that even though PEITC treatment suppresses Akt-mTOR signaling axis, this mechanism can't fully explain PEITC-mediated autophagic response.

The connection between apoptotic (type I cell death) and autophagic cell death (type II cell death) in the context of cancer-relevant stimuli is still unresolved, but autophagy seems to protect against apoptosis in some models. For example, inhibition of autophagy by chloroquine has been shown to increase activity of the alkylating agent cyclophosphamide in a Myc-driven model of lymphoma (34). Furthermore, 3-MA and chloroquine have been shown to synergistically augment the proapoptotic response to a histone deacetylase inhibitor (46). The results of the present study clearly indicate that autophagy is not a protective mechanism against PEITC-induced apoptosis at least in LNCaP and PC-3 cells, and that PEITC-mediated autophagy and apoptosis both contribute to PEITC-mediated suppression of prostate cancer cell growth.

The process of formation of autophagosomes is regulated by multiple proteins including Atg5. Previous studies have shown that enforced expression of Atg5 not only promotes autophagy but also enhances susceptibility towards apoptotic stimuli irrespective of the cell type (47). Apoptosis was associated with calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 resulting in translocation of truncated Atg5 to mitochondria for its association with Bcl-xL (47). We found that Atg5 protein status significantly impacts autophagic response to PEITC. Atg5 knockdown confers marked protection against PEITC-mediated cleavage of LC3 in both PC-3 and LNCaP cell lines. PEITC-mediated apoptotic DNA fragmentation in PC-3 and LNCaP cells is also significantly suppressed by knockdown of Atg5 protein level. These results not only demonstrate a critical role of Atg5 protein in regulation of PEITC-mediated autophagy in prostate cancer cells but also provide additional evidence to indicate that autophagy and apoptosis are interrelated in cancer cell growth suppression by PEITC. The mechanism by which Atg5 connects autophagic and apoptotic responses to PEITC is not yet clear.

In conclusion, the present study indicates that PEITC treatment selectively triggers autophagy in prostate cancer cells, and that Atg5 is critically involved in regulation of PEITC-mediated autophagic and apoptotic cell death.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This investigation was supported in part by the USPHS grants CA101753 and CA115498 (to SVS) awarded by the National Cancer Institute and the grant K08 AG028977 (to AF) awarded by the National Institute of Aging.

References

- 1.Nelson WG, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB. Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:366–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verhoeven DT, Goldbohm RA, van Poppel G, Verhagen H, van den Brandt PA. Epidemiological studies on brassica vegetables and cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:733–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolonel LN, Hankin JH, Whittemore AS, et al. Vegetables, fruits, legumes and prostate cancer: a multiethnic case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:795–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecht SS. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by isothiocyanates. Drug Metab Rev. 2000;32:395–411. doi: 10.1081/dmr-100102342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conaway CC, Yang YM, Chung FL. Isothiocyanates as cancer chemopreventive agents: their biological activities and metabolism in rodents and humans. Curr Drug Metab. 2002;3:233–55. doi: 10.2174/1389200023337496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morse MA, Wang C, Stoner GD, et al. Inhibition of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced DNA adduct formation and tumorigenicity in the lung of F344 rats by dietary phenethyl isothiocyanate. Cancer Res. 1989;49:549–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira MA. Chemoprevention of diethylnitrosamine-induced liver foci and hepatocellular adenomas in C3H mice. Anticancer Res. 1995;15:1953–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoner GD, Morrissey DT, Heur YH, Daniel EM, Galati AJ, Wagner SA. Inhibitory effects of Phenethyl isothiocyanate on N-nitrosobenzylmethylamine carcinogenesis in the rat esophagus. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2063–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang YM, Conaway CC, Chiao JW, et al. Inhibition of benzo(a)pyrene-induced lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice by dietary N-acetylcysteine conjugates of benzyl and Phenethyl isothiocyanates during the postinitiation phase is associated with activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and p53 activity and induction of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YR, Han J, Kori R, Kong AN, Tan TH. Phenylethyl isothiocyanate induces apoptotic signaling via suppressing phosphatase activity against c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39334–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao D, Singh SV. Phenethyl isothiocyanate-induced apoptosis in p53-deficient PC-3 human prostate cancer cell line is mediated by extracellular signal-regulated kinases. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3615–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu C, Shen G, Yuan X, et al. ERK and JNK signaling pathways are involved in the regulation of activator protein 1 and cell death elicited by three isothiocyanates in human prostate caner PC-3 cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:437–45. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao D, Johnson CS, Trump DL, Singh SV. Proteasome-mediated degradation of cell division cycle 25C and cyclin-dependent kinase 1 in Phenethyl isothiocyanate-induced G2-M-phase cell cycle arrest in PC-3 human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:567–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu C, Shen G, Chen C, Gelinas C, Kong AN. Suppression of NF-kappaB and NF-kappaB-regulated gene expression by sulforaphane and PEITC through lkappaBalpha, IKK pathway in human prostate cancer PC-3 cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:4486–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao D, Zeng Y, Choi S, Lew KL, Nelson JB, Singh SV. Caspase-dependent apoptosis induction by Phenethyl isothiocyanate, a cruciferous vegetable-derived cancer chemopreventive agent, is mediated by Bak and Bax. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2670–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao D, Lew KL, Zeng Y, et al. Phenethyl isothiocyanate-induced apoptosis in PC-3 human prostate cancer cells is mediated by reactive oxygen species-dependent disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:2223–34. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JH, Xu C, Keum YS, Reddy B, Conney A, Kong AN. Inhibition of EGFR signaling in human prostate cancer PC-3 cells by combination treatment with beta-phenylethyl isothiocyanate and curcumin. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:475–82. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang LG, Liu XM, Chiao JW. Repression of androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells by phenethyl isothiocyanate. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:2124–32. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J, Straub J, Xiao D, et al. Phenethyl isothiocyanate, a cancer chemopreventive constituent of cruciferous vegetables, inhibits cap-dependent translation by regulating the level and phosphorylation of 4E-BP-1. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3569–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao D, Singh SV. Phenethyl isothiocyanate inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and ex vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2239–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1542–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergamini E. Autophagy: a cell repair mechanism that retards aging and age-associated diseases and can be intensified pharmacologically. Mol Aspects Med. 2006;27:403–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meijer AJ, Codogno P. Signaling and autophagy regulation in health, aging and disease. Mol Aspects Med. 2006;27:411–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YA, Xiao D, Xiao H, et al. Mitochondria-mediated apoptosis by diallyl trisulfide in human prostate cancer cells is associated with generation of reactive oxygen species and regulated by Bax/Bak. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1599–609. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao D, Srivastava SK, Lew KL, et al. Allyl isothiocyanate, a constituent of cruciferous vegetables, inhibits proliferation of human prostate cancer cells by causing G2/M arrest and inducing apoptosis. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:891–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh SV, Mohan RR, Agarwal R, et al. Novel anti-carcinogenic activity of an organosulfide from garlic: Inhibition of H-RAS oncogene transformed tumor growth in vivo by diallyl disulfide is associated with inhibition of p21-H-ras processing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;225:660–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paglin S, Hollister T, Delohery T, et al. A novel response of cancer cells to radiation involves autophagy and formation of acidic vesicles. Cancer Res. 2001;61:439–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwamaru A, Kondo Y, Iwado E, et al. Silencing mammalian target of rapamycin signaling by small interfering RNA enhances rapamycin-induced autophagy in malignant glioma cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:1840–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;21:5720–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiang GG, Abraham RT. Targeting the mTOR signaling network in cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:433–42. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bai X, Ma D, Liu A, et al. Rheb activates mTOR by antagonizing its endogenous inhibitor, FKBP38. Science (Washington DC) 2007;318:977–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1147379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Hatano M, et al. Dissection of autophagosome formation using Apg5-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:657–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herman-Antosiewicz A, Johnson DE, Singh SV. Sulforaphane causes autophagy to inhibit release of cytochrome C and apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5828–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amaravadi RK, Yu D, Lum JJ, et al. Autophagy inhibition enhances therapy-induced apoptosis in a Myc-induced model of lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:326–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI28833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han J, Hou W, Goldstein LA, et al. Involvement of protective autophagy in TRAIL resistance of apoptosis-defective tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19665–77. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710169200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeuchi H, Kondo Y, Fujiwara K, et al. Synergistic augmentation of rapamycin-induced autophagy in malignant glioma cells by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3336–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanzawa T, Kondo Y, Ito H, Kondo S, Germano I. Induction of autophagic cell death in malignant glioma cells by arsenic trioxide. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2103–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang C, You YJ, Avery L. Dual roles of autophagy in the survival of Caenorhabditis elegans during starvation. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2161–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.1573107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melendez A, Talloczy Z, Seaman M, Eskelinen EL, Hall DH, Levine B. Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science (Washington DC) 2003;301:1387–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1087782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia K, Levine B. Autophagy is required for dietary restriction-mediated life span extension in C. elegans. Autophagy. 2007;3:597–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung FL, Morse MA, Eklind KI, Lewis J. Quantitation of human uptake of the anticarcinogen Phenethyl isothiocyanate after a watercress meal. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1992;1:383–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hecht SS, Chung FL, Richie JP, et al. Effects of watercress consumption on metabolism of a tobacco-specific lung carcinogen in smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:877–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tasdemir E, Maiuri CM, Galluzzi L, et al. Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:676–87. doi: 10.1038/ncb1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki K, Kubota Y, Sekito T, Ohsumi Y. Hierarchy of Atg proteins in pre-autophagosomal structure organization. Genes Cells. 2007;12:209–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang S, Houghton PJ. Targeting m-TOR signaling for cancer therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:371–7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carew JS, Nawrocki ST, Kahue CN, et al. Targeting autophagy augments the anticancer activity of the histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA to overcome Bcr-Abl mediated drug resistance. Blood. 2007;110:313–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yousefi S, Perozzo R, Schmid I, et al. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:1124–32. doi: 10.1038/ncb1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]