Abstract

We aimed to evaluate the efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) as a therapeutic option for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) through meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. For the years 1966 until September 2008, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched for double-blind, placebo-controlled trials investigating the efficacy of TCAs in the management of IBS. Seven randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials met our criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. TCAs used in the treatment arm of these trials included amitriptyline, imipramine, desipramine, doxepin and trimipramine. The pooled relative risk for clinical improvement with TCA therapy was 1.93 (95% CI: 1.44 to 2.6, P < 0.0001). Effect size of TCAs versus placebo for mean change in abdominal pain score among the two studies was -44.15 (95% CI: -53.27 to -35.04, P < 0.0001). It is concluded that low dose TCAs exhibit clinically and statistically significant control of IBS symptoms.

Keywords: Systematic review, Meta-analysis, Tricyclic antidepressants, Irritable bowel syndrome, Efficacy, Clinical response, Abdominal pain

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS OF IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME (IBS)

IBS is a prevalent functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by chronic or recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered bowel habits[1]. Up to 20% of the North American population are affected by IBS[2]. A community-based study carried out in Birmingham, UK estimated the prevalence of IBS to be 10.5%[3]. IBS is commonly diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 45 years and affects women twice as often as men[3,4]. IBS places a significant burden on health economy in terms of using more health care services even for non-gastrointestinal symptoms comparing to general population[5].

Environmental factors (psychological disturbances and stress), genetic links, recent infection, bacterial overgrowth, food intolerance, altered bowel motility and/or secretion, visceral hypersensitivity, altered central nervous system sensory processing, disturbed autonomic nervous system regulation, and serotonin dysregulation are all proposed as possible etiological factors for IBS[2–4,6,7].

MANAGEMENT OF IBS AND CURRENT PLACE OF TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS (TCAs)

In addition to non-pharmacological strategies such as diet and psychotherapy, various pharmacological agents are used for the management of IBS including bulking agents, antidiarrheal agents, laxatives, antispasmodics, antidepressants, serotonergic agonists or antagonists, antibiotics and probiotics[8–12]. The rationale of using antidepressants in IBS is that these agents may alter pain perception by a central modulation of visceral afferents, treat comorbid psychologic symptoms, and alter GI transit. Different classes of antidepressants likely act by different combinations of mechanisms[1]. Two classes of antidepressants frequently used for the treatment of IBS are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and TCAs. In a meta-analysis done in 2007[8], the efficacy of SSRIs in IBS was reported. In the present paper, the efficacy of TCAs in IBS has been reviewed by meta-analysis of all randomized controlled trials.

EVALUATION OF STUDIES

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched for studies investigated the efficacy of TCAs in IBS. Data were collected for the years 1966 to 2008 (up to September). The search terms were: “tricyclic antidepressants”, “amitriptyline”, “amoxapine”, “clomipramine”, “desipramine”, “dothiepin”, “doxepine”, “imipramine”, “iprindole”, “lofepramine”, “nortriptyline”, “opipramol”, “protriptyline”, or “trimipramine” and “irritable bowel”, “functional bowel diseases” or “irritable colon”. Search was restricted to English literature. Reference lists of the retrieved articles were also reviewed for additional applicable studies.

All controlled trials investigating the efficacy of TCAs in patients with IBS were considered. “Global improvement of symptoms” and “adequate relief of pain and discomfort” were the key outcomes of interest for assessment of efficacy. We evaluated all published studies as well as abstracts presented at meetings. Three reviewers independently examined the title and abstract of each article to eliminate duplicates, reviews, case studies, and uncontrolled trials. Trials were disqualified if they were not placebo-controlled or their outcomes did not consider efficacy. Reviewers independently extracted data on patients’ characteristics, therapeutic regimens, dosage, trial duration, and outcome measures. Disagreements, if any, were resolved by consensus.

Jadad score, which evaluates studies based on their description of randomization, blinding, and dropouts (withdrawals), was used to assess the methodological quality of the trials[13]. The quality scale ranges from 0 to 5 points with a low quality report of score 2 or less and a high quality report of score at least 3.

Data from selected studies were extracted into 2 × 2 tables. All included studies were weighted and pooled. Data analysis was done using StatsDirect (2.7.2). Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using Mantel-Haenszel and effect size (weighted mean difference) meta-analysis was performed using Mulrow-Oxman method. The Cochran Q test was used to test heterogeneity. The event rate in the experimental (intervention) group against the event rate in the control group was calculated using L'Abbe plot as an aid to explore the heterogeneity of effect estimates. In case of homogeneity, fixed effect model was used for meta-analysis; otherwise random effect model was applied. In addition to Kendall’s t test[14], funnel plots were used as an indicator for publication bias[15].

FINDINGS

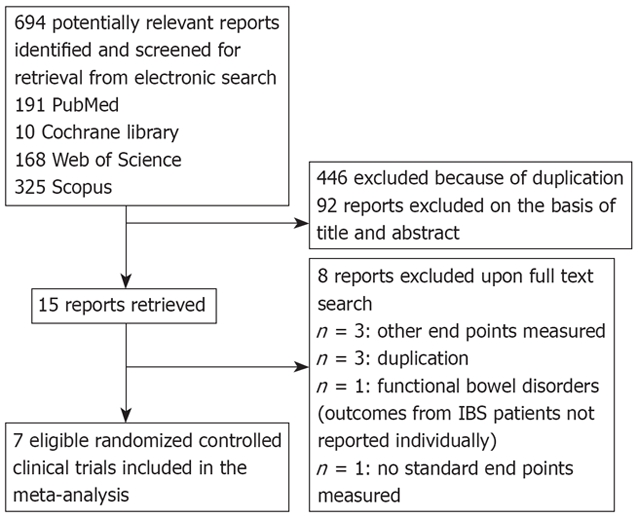

The electronic searches yielded 694 items; 191 from PubMed, 10 from Cochrane Central, 168 from Web of Science, and 325 from Scopus. Of these, 15 trials were scrutinized in full text and 7 trials[16–22] were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Of these 7 studies, 6[16–21] obtained a Jadad score of 3 or more and the remaining one[22] gained a Jadad score of 2 (Table 1). Regarding the Cochran Q test for heterogeneity, it was found that this study did not cause heterogeneity in our meta-analysis and thus, it was not excluded. Patients’ characteristics, IBS subtype, TCA subclass, dosage, duration of treatment/follow up for each study are reported in Table 2. All subtypes of IBS (diarrhea-predominant, constipation-predominant and alternating) were incorporated in the included studies. This meta-analysis included 257 IBS patients randomized to receive either TCA or placebo. The efficacy of various TCAs has been investigated including amitriptyline (3 trials), imipramine (1 trial), desipramine (1 trial), doxepin (1 trial) and trimipramine (1 trial). Duration of treatment/follow up ranged between 4 and 12 wk. Definition of clinical response and mean change in abdominal pain score in each study are reported in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

Table 1.

Jadad quality score of randomized controlled trials included in the meta-analysis

| Study |

Factors and Jadad score |

|||

| Randomization | Blinding | Withdrawals and dropouts | Total Jadad score | |

| Vahedi et al[16], 2008 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Talley et al[17], 2008 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Morgan et al[18], 2005 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Rajagopalan et al[19], 1998 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Vij et al[20], 1991 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Greenbaum et al[21], 1987 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Tripathi et al[22],1983 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of papers included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Mean age |

Sex |

IBS subtype | Type of TCA | Daily dosage | Duration of treatment/follow up (wk) | |

| Female | Male | ||||||

| Vahedi et al[16], 2008 | 36 | 21 | 29 | D-IBS | Amitriptyline | 10 mg | 8 |

| Talley et al[17], 2008 | ND | 21 | 13 | D-IBS, C-IBS, Alt-IBS | Imipramine | 2 wk: 25 mg; Thereafter to the end: 50 mg | 12 |

| Morgan et al[18], 2005 | 39 | 22 | 0 | D-IBS, C-IBS, Alt-IBS | Amitriptyline | First week: 25 mg; Thereafter to the end: 50 mg | 4 |

| Rajagopalan et al[19], 1998 | 34.8 | 11 | 11 | ND | Amitriptyline | First week: 25 mg; 2nd week: 50 mg; Thereafter to the end: 75 mg | 12 |

| Vij et al[20], 1991 | 32.5 | 14 | 36 | D-IBS, C-IBS, Alt-IBS | Doxepin | 75 mg | 6 |

| Greenbaum et al[21], 1987 | 45.2 | 18 | 11 | D-IBS, C-IBS | Desipramine | First week: 50 mg; 2nd week: 100 mg; Thereafter to the end: 150 mg | 6 |

| Tripathi et al[22], 1983 | 37 | ND | ND | ND | Trimipramine | 30 mg | 5 |

IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; D: Diarrhoea predominant; Alt: Alternating; C: Constipation predominant; TCA: Tricyclic antidepressant.

Table 3.

Response to treatment

| Study | Definition of response |

Response |

Change in abdominal pain score (No. of patients) |

||

| TCA | Placebo | TCA | Placebo | ||

| Vahedi et al[16], 2008 | Complete loss of symptoms (total score= 0) at the end of the study or at least two scores with a decrease in the number of symptoms | 17/25 | 10/25 | - | - |

| Talley et al[17], 2008 | Adequate relief of IBS symptoms over 50% of the weeks | 10/18 | 9/16 | -45.3 ± 26.3 (18) | -7.4 ± 46.9 (16) |

| Morgan et al[18], 2005 | Improvement of IBS symptoms determined by patients | 13/22 | 5/22 | - | - |

| Rajagopalan et al[19], 1998 | Global well-being: patients were asked to estimate at the post-treatment interview how much better or worse they were on the whole (in percentage) as compared to the pretrial period | 7/11 | 3/11 | - | - |

| Vij et al[20], 1991 | Improvement of 50% or above in IBS symptoms | 11/21 | 5/23 | - | - |

| Greenbaum et al[21], 1987 | Global assessment of improvement | 15/28 | 5/28 | -58.96 ± 19.37 (28) | -13.93 ± 17.76 (28) |

| Tripathi et al[22], 1983 | Improvement of 50% or above in IBS symptoms | 7/25 | 4/25 | - | - |

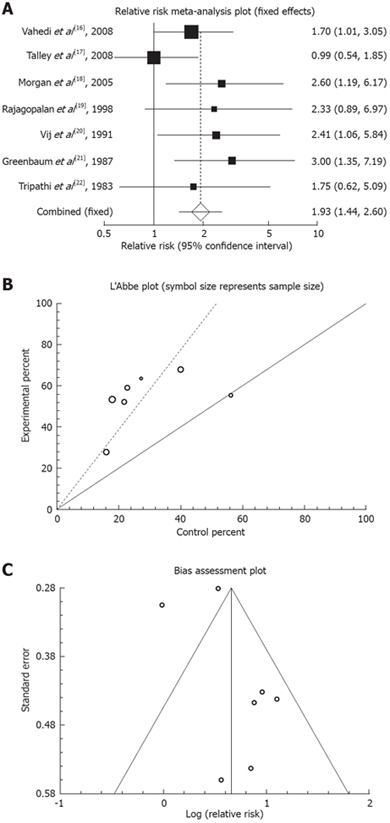

Cochrane Q test suggested that the studies are homogeneous (P = 0.3284, Figure 2B) therefore, a fixed effect model was used for meta-analysis. Regression of normalized effect versus precision for all included studies for clinical response among TCAs vs placebo therapy was 2.40 (95% CI: -1.14 to 5.95, P = 0.14). Funnel plot was suggestive of publication bias (Figure 2C); however, Kendall’s t test was not indicative of such a bias (tau = 0.05, P > 0.9999). Pooled RR for clinical response in 7 trials[16–22] was 1.93 (95% CI: 1.34 to 2.6, P < 0.0001, Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Outcome of “clinical response” in the studies considering TCAs vs placebo therapy. A: Individual and pooled relative risk; B: Heterogeneity indicators; C: Publication bias funnel plot.

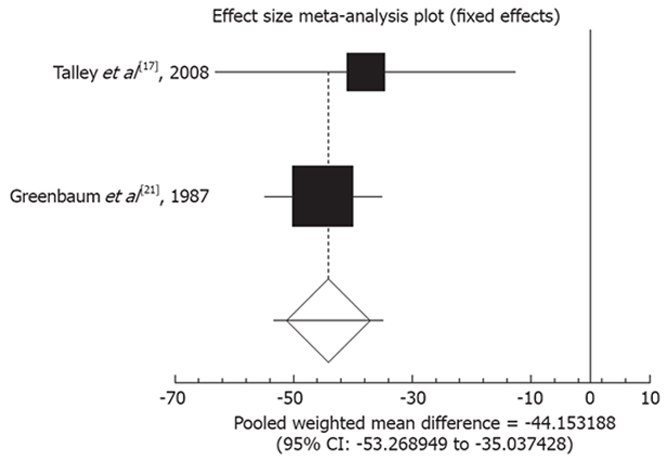

Studies that considered abdominal pain score as an outcome showed homogeneity using Cochrane Q test (P = 0.61). Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for mean change in abdominal pain score could not be calculated because of too few strata.

Using a fixed effect model, effect size of TCAs versus placebo for mean change in abdominal pain score among the two studies[17,21] was -44.15 (95% CI: -53.27 to -35.04, P < 0.0001, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pooled weighted mean difference for the outcome of “mean change in abdominal pain score” in the studies considering TCAs vs placebo.

DISCUSSION

Visceral hypersensitivity and dysregulation of central pain perception in the brain-gut axis is considered to play a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of IBS. IBS patients have a lower sensory threshold to colonic and rectal balloon distention and electrical stimulation[23]; therefore, beneficial effects of antidepressants can be explained by partial increment in central pain threshold. Other mechanisms by which antidepressants might express their effect include anticholinergic effects, regulation of GI transit and peripheral antineuropathic effects[24,25]. The results from the current meta-analysis show that TCAs induce clinical response and reduce abdominal pain score in patients with IBS.

Other meta-analysis studies that considered the effects of antidepressants in functional gastrointestinal diseases have essential differences with the present study: O'Malley et al[26] pooled all functional diseases including IBS, functional dyspepsia, headache, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue. Jackson et al[27] included all the functional gastrointestinal disorders and found a statistically significant effect for TCAs (OR 4.2; 95% CI: 2.3 to 7.9). Quartero et al[8] included 4 studies for “global improvement of symptoms” and 2 studies for “abdominal pain” and demonstrated no benefit for antidepressants. Lesbros-Pantoflickova et al[28] demonstrated a favorable effect for antidepressants (OR 2.6; 95% CI: 1.9 to 3.5). Studies with visual analogue outcome[29] and functional dyspepsia patients were included in their analysis. None of these reviews meta-analyzed the newer evidence that has surfaced in the literature[16,17,18].

Unfortunately, conduction of a randomized controlled trial in the field of antidepressants and IBS is challenging. High placebo response in IBS affects study trials and the stigma of antidepressants disturbs the compliance rate. Randomization is elusive as TCAs have immediate noticeable side effects for patients. As mentioned in Table 1, the majority of trials are of a medium quality. A well-designed trial has been conducted by Drossman et al[30] although not included in our study because of the recruitment of all functional bowel disorders. Drossman et al[30] conducted a large randomized 12-wk placebo-controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of desipramine in treating moderate to severe IBS (80% of the patients), functional constipation and functional chronic abdominal pain. Desipramine was shown to have statistically significant benefit over placebo in the per protocol analysis after non-compliant and drop-out patients were excluded (responder rate 73% vs 49%). 11% of the patients were proven to be non-adherent with non-detectable blood levels. This underlines the fact that previous studies might have underestimated the effect of antidepressants by the inclusion of non-adherent cases.

The choice of antidepressants in IBS patients remains controversial. Head to head trials comparing different classes or subclass formulations of antidepressants are lacking in the literature. In a recent meta-analysis[9], we concluded that on current evidence, SSRIs do not improve abdominal pain, abdominal bloating or other IBS symptoms. Three studies have compared the effects of TCAs with SSRIs and all together they depict a non-conclusive picture[17,31,32]. Talley et al[17] compared imipramine with citalopram during a 12-wk trial. Clinical response was seen in 56% of imipramine group, 47% of citalopram group and 56% of placebo arm. Neither imipramine nor citalopram siginificantly improved global IBS endpoints over placebo. Forootan et al[31] compared the effects of nortriptyline, amitriptyline, and fluoxetine. The results demonstrated improvement of abdominal pain, flatulence, and general performance in all subgroups. Amitriptyline and nortriptyline improved frequency of defecation in both diarrhea- and constipation-predominant IBS, while fluoxetine improved GI transit of constipation- predominant IBS. Differential effects of amitriptyline and fluoxetine on anorectal motility and visceral perception were assessed by Siproudhis et al[32] and the results demonstrated that both antidepressants similarly relax the internal anal sphincter, but only amitriptyline relaxed the external anal sphincter.

Generally, management of IBS requires lower doses of TCAs compared to doses used to treat depression; reflecting the fact that modulation of the brain-gut axis rather than treating concomitant depression is the target in IBS patients. Myren et al[29] in a large 8-wk trial demonstrated no dose-related response with various dosing regimens of trimipramine.

CONCLUSION

This review has some limitations. Funnel plot is suggestive of publication bias with lack of negative small RCTs. However, a firm conclusion about bias is elusive to reach as the asymmetry of the funnel plot is minimal and Kendall’s T is not suggestive of publication bias. In addition funnel plots can show asymmetry for various reasons other than publication bias[33]. Paucity of small negative or neutral studies has been brought to attention in other functional disorders[26] which might encompass IBS as well. Therefore, our pooled OR might be an overestimate of the true effect. Some other limitations that can be numbered for this meta-analysis are usage of various TCA formulations and doses, dissimilar duration of treatment, and different diagnostic criteria for IBS.

TCAs exhibit clinically and statistically significant control of IBS symptoms; however, given their abundant side effects they should be reserved for moderate to severe cases. Subjects should be started on subtherapeutic doses for depression and choice of drug should be tailored for each individual. We suggest using TCAs with the least anticholinergic effects (i.e. doxepin and desipramine) for elderly patients or constipation-predominant IBS and imipramine or amitriptyline for diarrhea-predominant IBS and patients with insomnia. Larger comparative trials with strict surveillance on compliance are needed to elaborate the role of antidepressants in standard practice.

In addition, new evidence suggests that IBS is very similar to IBD in pathogenesis but different in severity. Recent meta-analyses have indicated the benefit of antibiotics, probiotics, and anti-tumor necrosis factor agents[34–42] in IBD and thus the effects of these drugs on IBS remain to be elucidated in the future.

Supported by National Science Foundation, Tehran

Peer reviewers: Ian D Wallace, MD, Shakespeare Specialist Group, 181 Shakespeare Rd, Milford, Auckland 1309, New Zealand; Yoshiharu Motoo, MD, PhD, FACP, FACG, Professor and Chairman, Department of Medical Oncology, Kanazawa Medical University, 1-1 Daigaku, Uchinada, Ishikawa 920-0293, Japan

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Videlock EJ, Chang L. Irritable bowel syndrome: current approach to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36:665–685, x. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:S1–S5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(02)05656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson S, Roberts L, Roalfe A, Bridge P, Singh S. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: a community survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:495–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croghan A, Heitkemper MM. Recognizing and managing patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17:51–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1041-2972.2005.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longstreth GF, Wilson A, Knight K, Wong J, Chiou CF, Barghout V, Frech F, Ofman JJ. Irritable bowel syndrome, health care use, and costs: a U.S. managed care perspective. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:600–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bommelaer G, Dorval E, Denis P, Czernichow P, Frexinos J, Pelc A, Slama A, El Hasnaoui A. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in the French population according to the Rome I criteria. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2002;26:1118–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foxx-Orenstein A. IBS--review and what's new. MedGenMed. 2006;8:20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quartero AO, Meineche-Schmidt V, Muris J, Rubin G, de Wit N. Bulking agents, antispasmodic and antidepressant medication for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;8:CD003460. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003460.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the management of irritable bowel syndrome: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Med Sci. 2008;4:71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Efficacy and tolerability of alosetron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in women and men: a meta-analysis of eight randomized, placebo-controlled, 12-week trials. Clin Ther. 2008;30:884–901. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fumi AL, Trexler K. Rifaximin treatment for symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:408–412. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Rahimi F, Derakhshani S, Abdollahi M. Efficacy of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1775–1780. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9335-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadad A. Randomised controlled trials: a user's duide. Vol. 51. BMJ Books: London; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vahedi H, Merat S, Momtahen S, Kazzazi AS, Ghaffari N, Olfati G, Malekzadeh R. Clinical trial: the effect of amitriptyline in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:678–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talley NJ, Kellow JE, Boyce P, Tennant C, Huskic S, Jones M. Antidepressant therapy (imipramine and citalopram) for irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:108–115. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan V, Pickens D, Gautam S, Kessler R, Mertz H. Amitriptyline reduces rectal pain related activation of the anterior cingulate cortex in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2005;54:601–607. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajagopalan M, Kurian G, John J. Symptom relief with amitriptyline in the irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:738–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vij JG, Jiloha RG, Kumar N, Madhu SV, Malika V, Anand BS. Effect of antidepressant drug (doxepin) on irritable bowel syndrome patients. Indian J Psychiatry. 1991;33:243–246. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenbaum DS, Mayle JE, Vanegeren LE, Jerome JA, Mayor JW, Greenbaum RB, Matson RW, Stein GE, Dean HA, Halvorsen NA. Effects of desipramine on irritable bowel syndrome compared with atropine and placebo. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:257–266. doi: 10.1007/BF01297051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tripathi BM, Misra NP, Gupta AK. Evaluation of tricyclic compound (trimipramine) vis-a-vis placebo in irritable bowel syndrome. (Double blind randomised study) J Assoc Physicians India. 1983;31:201–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truong TT, Naliboff BD, Chang L. Novel techniques to study visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:369–378. doi: 10.1007/s11894-008-0071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer EA, Tillisch K, Bradesi S. Review article: modulation of the brain-gut axis as a therapeutic approach in gastrointestinal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:919–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorelick AB, Koshy SS, Hooper FG, Bennett TC, Chey WD, Hasler WL. Differential effects of amitriptyline on perception of somatic and visceral stimulation in healthy humans. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G460–G466. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.3.G460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Malley PG, Jackson JL, Santoro J, Tomkins G, Balden E, Kroenke K. Antidepressant therapy for unexplained symptoms and symptom syndromes. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:980–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson JL, O'Malley PG, Tomkins G, Balden E, Santoro J, Kroenke K. Treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders with antidepressant medications: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2000;108:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Michetti P, Fried M, Beglinger C, Blum AL. Meta-analysis: The treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1253–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myren J, Løvland B, Larssen SE, Larsen S. A double-blind study of the effect of trimipramine in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1984;19:835–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drossman DA, Toner BB, Whitehead WE, Diamant NE, Dalton CB, Duncan S, Emmott S, Proffitt V, Akman D, Frusciante K, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus education and desipramine versus placebo for moderate to severe functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:19–31. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00669-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forootan H, Taheri A, Hooshangi H, Mohammadi HR. Effects of Fluoxetine, Nortriptyline and Amitriptyline in IBS patients. Feyz Kashan Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 2002;21:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siproudhis L, Dinasquet M, Sébille V, Reymann JM, Bellissant E. Differential effects of two types of antidepressants, amitriptyline and fluoxetine, on anorectal motility and visceral perception. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:689–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:882–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis of the benefit of probiotics in maintaining remission of human ulcerative colitis: evidence for prevention of disease relapse and maintenance of remission. Arch Med Sci. 2008;4:185–190. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rahimi F, Elahi B, Derakhshani S, Vafaie M, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis on the efficacy of probiotics for maintenance of remission and prevention of clinical and endoscopic relapse in Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2524–2531. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Meta-analysis technique confirms the effectiveness of anti-TNF-alpha in the management of active ulcerative colitis when administered in combination with corticosteroids. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:PI13–PI18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis of antibiotic therapy for active ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2920–2925. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9760-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Do anti-tumor necrosis factors induce response and remission in patients with acute refractory Crohn's disease? A systematic meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Biomed Pharmacother. 2007;61:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy in patients with active Crohn's disease. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1983–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Efficacy and tolerability of Hypericum perforatum in major depressive disorder in comparison with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elahi B, Nikfar S, Derakhshani S, Vafaie M, Abdollahi M. On the benefit of probiotics in the management of pouchitis in patients underwent ileal pouch anal anastomosis: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1278–1284. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0006-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Derakhshani S, Pakzad M, Vafaie M, Tehrani-Tarighat S, Abdollahi M. A report of 112 cases of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome from Iran. Cent Eur J Med. 2009;4:49–53. [Google Scholar]