Abstract

Arterioportal fistula (APF) is a rare cause of portal hypertension and may lead to death. APF can be congenital, post-traumatic, iatrogenic (transhepatic intervention or biopsy) or related to ruptured hepatic artery aneurysms. Congenital APF is a rare condition even in children. In this case report, we describe a 73-year-old woman diagnosed as APF by ultrasonography, computed tomography, and hepatic artery selective arteriography. The fistula was embolized twice but failed, and she still suffered from alimentary tract hemorrhage. Then, selective arteriography of the hepatic artery was performed again and venae coronaria ventriculi and short gastric vein were embolized. During the 2-year follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic. We therefore argue that embolization of venae coronaria ventriculi and short gastric vein may be an effective treatment modality for intrahepatic APF with severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Keywords: Congenital intrahepatic arterioportal fistula, Liver, Embolization, Portal hypertension, Angiography

INTRODUCTION

Arterioportal fistula (APF) is a rare cause of portal hypertension and may lead to death. APF can be congenital, post-traumatic, iatrogenic (transhepatic intervention or biopsy) or related to ruptured hepatic artery aneurysms. Congenital APF is a rare condition in children. To date, only 18 cases of congenital intrahepatic APF have been reported[1]. Most of them were found in their infancy, in which the oldest one was a 13-year-old boy[1]. We report here the incidental findings of a large and solitary congenital APF in a 73-year-old woman. Digital subtraction angiography revealed a stubby fistular vessel between the left hepatic artery and portal vein of the patient. Transcatheter closure of APF was performed three times using multiple coils.

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with complaints of ascites, splenomegaly, abdominal distension and pain. She had been asymptomatic before and denied any medication history as well as history of cirrhosis and hepatic neoplasms, blunt or penetrating trauma, percutaneous liver biopsy, transhepatic cholangiography, gastrectomy and biliary surgery. Her mother and aunt died of ascites and gastrointestinal bleeding in their thirties, about 60 years ago. There was no history of chronic hepatic disease in her family.

A recent physical examination revealed ascites, splenomegaly, and a subcutaneous varicose vein in the abdominal wall. Her laboratory results are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Laboratory results

| Item | Results |

| Hemoglobin | 97 g/L |

| Hematocrit | 40.30% |

| MCV | 89.8 fL |

| Blood cell count | 4.0 × 109/L |

| Platelet count | 131 × 109/L |

| Prothrombin time | 14 s (normal value: 9.8-15.0 s) |

| Serum ALT | 37 IU/L (normal value: 3-40 IU/L) |

| Serum AST | 62 IU/L (normal value: 3-40 IU/L) |

| Serum GGT | 102 IU/L (normal value: 0-54 IU/L) |

| Serum ALP | 141 IU/L (normal value: 30-115 IU/L) |

| Total bilirubin | 10 μmol/L (normal value < 22 μmol/L) |

| Direct bilirubin | 4 μmol/L (normal value < 7 μmol/L) |

| Albumin | 39.7 g/L |

Values for other biochemical tests were within the normal ranges. All viral markers for hepatitis including hepatitis A-E viruses, autoantibodies (antinuclear, anti-mitochondrial, anti-smooth-muscle, anti-liver-kidney microsomal enzymes, anti-soluble liver antigen, and anti-mitochondrial antibody) were also negative. Serum alpha-fetoprotein level was normal. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed non-bleeding esophageal and fundus varices, but mild portal hypertensive gastropathy.

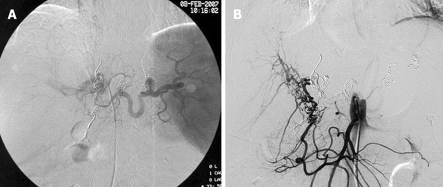

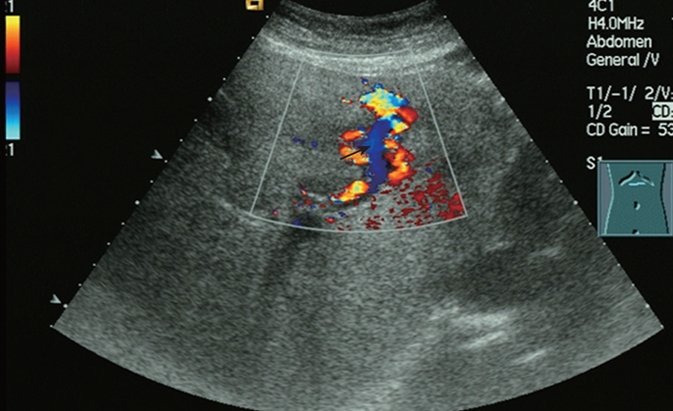

Real-time sonography of the liver demonstrated an anechoic lesion in continuity with a normal width of the left portal vein (LPV) branch, which was assumed to be an intrahepatic APF. Reverse flow in the left portal vein was observed on color Doppler sonography (Figure 1), and high-velocity flow at 1.31 m/s (Figure 2) was observed on spectral Doppler sonography. The distal portion of the LPV showed no enlargement but turbulent flow. The left hepatic artery branch was dilated, with a diameter of 5 mm. Color speckling (mosaic pattern), present in hepatic tissues adjacent to the aneurysmal lesion, was considered a typical sign of arteriovenous fistula.

Figure 1.

Color Doppler sonography of the portal vein aneurysm showing increased blood flow in the LPV and turbulence (arrow) at the distal portion of the aneurysmal sac.

Figure 2.

PW Doppler sonography of the portal vein aneurysm showing a high speed blood flow at 1.31 m/s in the aneurysm.

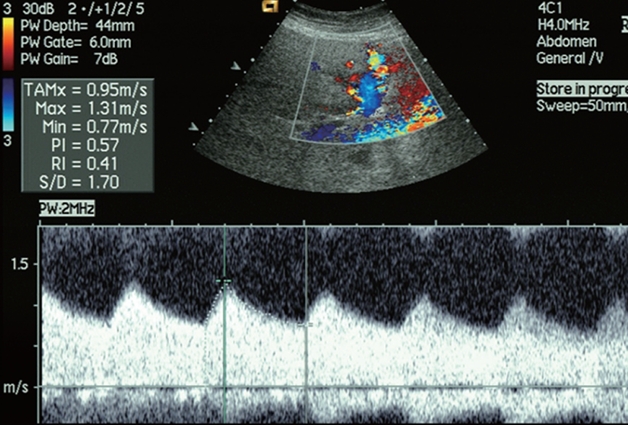

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) also confirmed the diagnosis of intrahepatic APF. A high density of the LPV was observed with a CT value of 220.6 Hounsfield units (HU) (Figure 3A) at the arterial phase, and a CT value of 159.7 Hu (Figure 3B) at the portal venous phase, close to the CT values of 226.2 Hu (Figure 3A) and 168.0 Hu (Figure 3B), respectively, for the abdominal aorta at the same phase.

Figure 3.

Contrast-enhanced CT showing a LPV density of 220.6 Hu and an abdominal aorta density of 226.2 Hu at artery phase (A), a LPV density of 159.7 Hu and an abdominal aorta density of 168.0 Hu at portal venous phase (B), and CT of coronal section (C) and sagittal section (D) showing the direct shunt of APF.

After a comprehensive analysis, a diagnosis of portal hypertension secondary to hepaticoportal fistula was established.

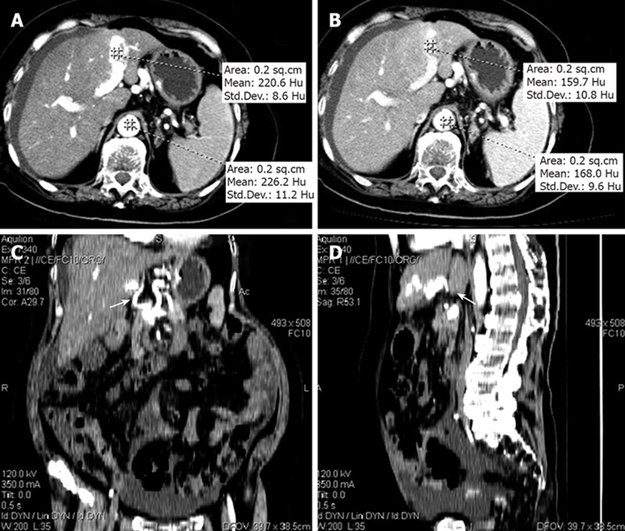

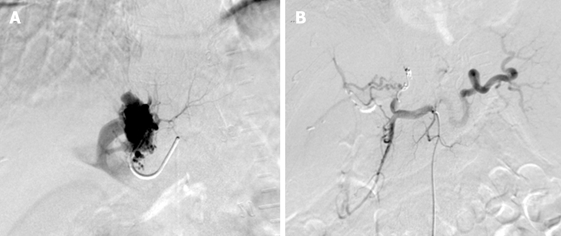

Selective digital subtraction angiography of the hepatic artery was performed, which revealed a large left hepatic artery-left portal vein fistula (Figure 4A). The aneurysmal lesion was embolized, and angiography CT and sonography showed no shunt after operation (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Selective digital subtraction angiography of the hepatic artery. A: A large left hepatic artery-left portal vein fistula; B: No more shunt after embolism.

Three months after operation, the patients had severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding from esophageal and fundus varices. She received another transcatheter closure, with no recurrence of bleeding. She underwent somatostatin infusion and conservative treatment but hemorrhage recurred 1 mo later. She refused any surgical intervention. Selective arteriography of the hepatic artery was performed again with her venae coronaria ventriculi and short gastric vein embolized (Figure 5A and B). During the 2-year follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic.

Figure 5.

Angiography showing collateral circulation in fistula after embolism (A) and no more shunt after embolism (B).

DISCUSSION

Congenital APF is a rare cause of severe portal hypertension, with challenging diagnostic and therapeutic implications[2,3]. Upon physical examination, a characteristic bruit can be heard over the right upper quadrant. Liver function tests are usually normal. Radiologic evaluation of APF is usually performed with color Doppler ultrasonography (US), helical CT, and magnetic resonance imaging. Arterial and direct portography as well as splenoportography may also be used. Doppler ultrasound is the best way in making the decisive diagnosis and helpful in the subsequent evaluation of these patients[4,5]. Angiography is the most useful test because it can not only identify multiple APFs but also be therapeutic. These APFs are mostly intrahepatic and represent 12% of the cases developmental intrahepatic shunts[3]. The presence of a patent ductus venosus is protective in the initial postnatal period. Symptoms usually develop after 1 mo of age, and these children are often investigated for generalized abdominal findings and are later noted to develop symptoms related to portal hypertension[2,3]. APF often presents in conjunction with major gastrointestinal tract bleeding and should be differentiated between small peripheral intrahepatic APF (type 1) and large central APF (type 2), whereas diffuse congenital intrahepatic APF that is difficult to manage is defined as typed 3[6]. A few cases of congenital fistula from the hepatic artery to the portal vein have been reported[4], but this abnormality is not a common cause of portal hypertension. Increased blood flow in the portal system is considered to be the cause of hyperkinetic portal hypertension in patients with hepatoportal arteriovenous fistula. Arteroportal venous fistula can be treated with percutaneous arterial occlusion[7]. Ligation of the hepatic artery has been proved to be successful in reported cases[8]. Recently, transcatheter arterial embolization has been attempted as the first choice, because of its low invasiveness and success in some cases. Recanalization of the embolized artery in some cases has also been reported[9,10]. Therefore, some of the cases can undergo hepatic resection, including fistula.

To date, in the literature, the oldest congenital APF case was a 13-year-old child[1]. We report here a 73-year-old woman. This patient had no history of cirrhosis and hepatic neoplasms, blunt or penetrating trauma, percutaneous liver biopsy, transhepatic cholangiography, gastrectomy, and biliary surgery, and was finally diagnosed having a congenital APF. Initially, the APF was demonstrated by contrast-enhanced CT and the fistula was subsequently identified by color Doppler imaging and angiography. The case was classified as type 3.

No more shunt was found after coil occlusion. Notably, esophageal varices and ascites disappeared after embolization. However, color Doppler sonography still displayed the shunt 3 mo after operation.

The aneurysmal lesion was embolized twice, but transcatheter closure did not work well. After undergoing embolization twice, she suffered alimentary tract hemorrhage again, suggesting that transcatheter closure is not so effective against a large APF. The reason why embolization failed was because of too much collateral circulation. The purpose of embolizing the venae coronaria ventriculi and short gastric vein is to cut off the collateral circulation, because it can effectively control hemostasis. Since it cannot cure the disease, the treatment modality is radical surgery.

In conclusion, this case suggests that interventional radiology plays an important role in the treatment of congenital APF with severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding caused by esophageal and fundus varices. Liver function test, abdomen ultrasonography and gastroscopy should be performed regularity during the follow-up.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Paolo Del Poggio, Hepatology Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Treviglio Hospital, Piazza Ospedale 1, Treviglio Bg 24047, Italy; David Cronin II, MD, PhD, FACS, Associate Professor, Department of Surgery, Yale University School of Medicine, 330 Cedar Street, FMB 116, PO Box 208062, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8062, United States

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Wang XL and Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Kumar N, de Goyet Jde V, Sharif K, McKiernan P, John P. Congenital, solitary, large, intrahepatic arterioportal fistula in a child: management and review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:20–23. doi: 10.1007/s00247-002-0764-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heaton ND, Davenport M, Karani J, Mowat AP, Howard ER. Congenital hepatoportal arteriovenous fistula. Surgery. 1995;117:170–174. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paley MR, Farrant P, Kane P, Heaton ND, Howard ER, Karani JB. Developmental intrahepatic shunts of childhood: radiological features and management. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:1377–1382. doi: 10.1007/s003300050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallego C, Miralles M, Marin C, Muyor P, Gonzalez G, Garcia-Hidalgo E. Congenital hepatic shunts. Radiographics. 2004;24:755–772. doi: 10.1148/rg.243035046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallego C, Velasco M, Marcuello P, Tejedor D, De Campo L, Friera A. Congenital and acquired anomalies of the portal venous system. Radiographics. 2002;22:141–159. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.1.g02ja08141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzman EA, McCahill LE, Rogers FB. Arterioportal fistulas: introduction of a novel classification with therapeutic implications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumann UA, Tillmann U, Frei J, Fehr HF. [Arterial aneurysm of the liver with arterio-portal fistula: treatment using embolization] Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1984;114:451–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donovan AJ, Reynolds TB, Mikkelsen WP, Peters RL. Systemic-portal arteriovenous fistulas: pathological and hemodynamic observations in two patients. Surgery. 1969;66:474–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko S, Nakajima Y, Kanehiro H, Aomatsu Y, Yoshimura A, Taki J, Ueno M, Kin T, Nakano H. Successful management of portal hypertension following artificial arterioportal shunting: report of a case. Surg Today. 1995;25:557–559. doi: 10.1007/BF00311316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwala S, Dutta H, Bhatnagar V, Gulathi M, Paul S, Mitra D. Congenital hepatoportal arteriovenous fistula: report of a case. Surg Today. 2000;30:268–271. doi: 10.1007/s005950050057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]