Abstract

We tested the hypothesis that dynamic cerebral autoregulation (CA) and blood–brain barrier (BBB) function would be compromised in acute mountain sickness (AMS) subsequent to a hypoxia-mediated alteration in systemic free radical metabolism. Eighteen male lowlanders were examined in normoxia (21% O2) and following 6 h passive exposure to hypoxia (12% O2). Blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery (MCAv) and mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) were measured for determination of CA following calculation of transfer function analysis and rate of regulation (RoR). Nine subjects developed clinical AMS (AMS+) and were more hypoxaemic relative to subjects without AMS (AMS–). A more marked increase in the venous concentration of the ascorbate radical (A•−), lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) and increased susceptibility of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) to oxidation was observed during hypoxia in AMS+ (P < 0.05 versus AMS–). Despite a general decline in total nitric oxide (NO) in hypoxia (P < 0.05 versus normoxia), the normoxic baseline plasma and red blood cell (RBC) NO metabolite pool was lower in AMS+ with normalization observed during hypoxia (P < 0.05 versus AMS–). CA was selectively impaired in AMS+ as indicated both by an increase in the low-frequency (0.07–0.20Hz) transfer function gain and decrease in RoR (P < 0.05 versus AMS–). However, there was no evidence for cerebral hyper-perfusion, BBB disruption or neuronal–parenchymal damage as indicated by a lack of change in MCAv, S100β and neuron-specific enolase. In conclusion, these findings suggest that AMS is associated with altered redox homeostasis and disordered CA independent of barrier disruption.

Acute mountain sickness (AMS) is a primary disorder of the central nervous system characterized by headache which is associated with, if not the primary trigger for, other vegetative symptoms typically experienced by non-acclimatized mountaineers within 6–12 h of arrival to altitudes above 2500 m (Hackett & Roach, 2001). Though controversial (Bartsch et al. 2004), AMS is considered a mild form of high-altitude cerebral oedema (HACE) defined by vasogenic oedematous brain swelling (Roach & Hackett, 2001). Intracranial hypertension subsequent to an increase in intracranial volume (ICV) may prove the primary mechanism underlying headache following mechanical stimulation of pain-sensitive unmyelinated fibres that reside within the trigeminovascular system (TVS) (Sanchez del Rio & Moskowitz, 1999).

Recent attention has focused on disordered cerebral autoregulation (CA) as a potential haemodynamic risk factor that could increase ICV and thus predispose to AMS. Lassen & Harper (1975) were the first to hypothesize that in the setting of hypoxic cerebral vasodilatation, impaired CA would lead to a pressure-passive increase in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and the resultant elevation in cerebral capillary hydrostatic pressure would cause extracellular (vasogenic) oedema subsequent to mechanical disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Though recent MRI findings have failed to detect any evidence for barrier failure (Bailey et al. 2006a; Kallenberg et al. 2007, 2008; Schoonman et al. 2008), the inverse relationship recently observed between AMS cerebral symptom score and index of dynamic CA at high-altitude (HA) lends preliminary, albeit tentative, support to the vasogenic hypothesis (Van Osta et al. 2005).

However, the mechanisms underlying impaired CA in AMS have not been established. Though controversial (Zhang et al. 2004), the potent vasodilator nitric oxide (NO) may play an important role in the maintenance of cerebral vasomotor tone and BBB integrity by dynamically buffering changes in CBF in response to spontaneous changes in blood pressure (White et al. 2000). Vascular NO bioavailability is in part regulated by free radicals (Gryglewsky et al. 1986), which preliminary indications suggest may be responsible for the enhanced lipid peroxidation previously documented in AMS (Bailey et al. 2001b). Alternatively, NO could directly stimulate the TVS and trigger neurovascular headache (Sanchez del Rio & Moskowitz, 1999).

In light of these findings, the current study was designed to test the original hypothesis that dynamic CA and BBB function would be compromised in the most hypoxaemic subjects who develop AMS subsequent to a hypoxia-mediated alteration in systemic free radical metabolism, specifically the dynamic interplay between oxidative stress and NO metabolism. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy and ozone-based chemiluminescence (OBC) were specifically employed since they represent the most direct, sensitive techniques currently available for the molecular detection of free radicals and NO metabolites, respectively (Bailey, 2003; Rassaf et al. 2004; Swartz et al. 2007). The astrocytic protein S100β was incorporated as a metabolic surrogate of BBB integrity (Kanner et al. 2003b; Marchi et al. 2003) and transfer function analysis (Zhang et al. 1998) complemented by the thigh-cuff technique (Aaslid et al. 1989) to assess dynamic CA.

Methods

Subjects

Eighteen physically active and apparently healthy male lowlanders born and bred at sea level aged 26 ± 6 (mean ±s.d.) years old participated in the study. They provided written informed consent following local research ethics committee approval in accordance with procedures outlined by the Declaration of Helsinki. Specific exclusion criteria included any history of chronic daily headache, habitual antioxidant vitamin or anti-inflammatory supplementation, smoking and cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, or respiratory disease.

Experimental design

Subjects were instructed to attend the laboratory at 07.30 h, exactly 3 h following consumption of a standardised carbohydrate–protein drink and having refrained from any vigorous physical activity for 48 h. After 30 min of supine rest, measurements were performed in normoxia (21% O2) and following 6 h passive exposure to normobaric hypoxia (12% O2) in a thermoneutral environmental chamber. The hypoxic stimulus was comparable to that encountered at a terrestrial altitude of 4600 m (Bailey et al. 2006b).

Metabolic measurements

Venous blood was obtained from an indwelling catheter located in a forearm antecubital vein after 30 min of supine rest. Blood was centrifuged at 600 g (4°C) for 10 min and serum, plasma and red blood cells (RBCs) were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Samples were left to defrost at 21°C in the dark for 5 min prior to subsequent analyses.

Oxidative stress

Ascorbate free radical (A•−)

A•− was measured as a direct biomarker of oxidative stress (Buettner & Jurkiewicz, 1993; Bailey, 2004; Bailey et al. 2006a). Exactly 1 ml of K-EDTA plasma was injected into a high-sensitivity multiple-bore sample cell (AquaX, Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, MA, USA) housed within a TM110 cavity of an EPR spectrometer operating at X-band (9.87 GHz). Samples were analysed using a modulation frequency of 100 kHz, modulation amplitude of 0.65 gauss (G), microwave power of 10 mW, receiver gain of 2 × 105, time constant of 41 ms, magnetic field centre of 3477 G and scan width of ± 50 G for three incremental scans. After identical baseline correction and filtering, each of the spectral peak-to-trough line heights was normalized relative to the square root of line width in G and the mean considered a measure of the relative concentration of A•− following conformation of peak-to-trough line-width conformity and double integration on a random selection of samples. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation (CV) were both < 5%.

Lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH)

Serum LOOH was determined using the ferrous iron/xylenol orange (FOX) assay (Wolff, 1994) with modification. The intra- and interassay CV were < 2% and < 4%, respectively.

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation

LDL was isolated from plasma by rapid ultracentrifugation and oxidised according to established methods (McDowell et al. 1995; Bailey et al. 2006a). The protein concentration was standardized to 50 mg l−1 and oxidation was initiated by the addition of copper II chloride (2 μmol l−1 final concentration) at 37°C. Conjugated diene formation was monitored spectrophotometrically (in triplicate) by the change in absorbance at 234 nm using a 96-well microplate reader (SpectraMax 190, Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The time at half-maximum absorbance of the propagation phase (time ½max in min) was interpreted as a direct reflection of LDL oxidation potential. The intra- and interassay CV were < 3% and < 5%, respectively.

Antioxidants

For ascorbic acid measurements, plasma was stabilized and deproteinated by adding 900 μl of 5% metaphosphoric acid (Sigma Chemical Co., Poole, UK) to 100 μl K-EDTA plasma. Ascorbic acid was subsequently assayed by fluorimetry based on the condensation of dehydroascorbic acid with 1,2-phenylenediamine (Vuilleumier & Keck, 1993). Concentrations of α/γ-tocopherol, lycopene, α-carotene, β-carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin and β-cryptoxanthin were determined using an HPLC method (Catignani & Bieri, 1983; Thurnham et al. 1988). The intra- and interassay CV were both < 5%.

NO metabolites

OBC is arguably the most sensitive technique for the molecular detection of NO in human blood (Rassaf et al. 2004). It was employed for the detection of plasma and red blood cell (RBC)-bound NO metabolites (Yang et al. 2003; Maher et al. 2008) using the Sievers NOA 280i nitric oxide analyser (GE Analytical Instruments, Boulder, CO, USA).

Plasma metabolites

Samples (20 μl) were analysed for the total concentration of plasma NO (nitrate (NO•3) + nitrite (NO•2) +S-nitrosothiols (RSNO)) by vanadium (III) reduction (Ewing & Janero, 1998). A separate sample (200 μl) was injected into tri-iodide reagent (Hausladen et al. 2007; Rogers et al. 2007) for the measurement of NO•2+ RSNO and 5% acidified sulphanilamide added and left to incubate in the dark at 21°C for 15 min to remove NO•2 for the measurement of RSNO in a third parallel sample. Nitrate (NO•3) was calculated as total NO – (NO•2+ RSNO).

RBC metabolites

Samples (100 μl) were injected into a modified tri-iodide reagent (Rogers et al. 2005) for the measurement of total RBC-bound NO (NO•2+ nitrosyl haemoglobin (HbNO) +S-nitrosohaemoglobin (HbSNO)). Acidified sulphanilamide was added to allow detection of Hb-bound NO. All calculations were performed using the Peak Fitting Module for Origin (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). The intra- and interassay CV for all NO metabolites were 7% and 10%, respectively.

Brain-specific proteins

S100β and neuron specific enolase (NSE)

The serum concentration of S100β and NSE were measured as peripheral biomarkers of BBB ‘leak’ (Kanner et al. 2003a; Marchi et al. 2003) and neuronal–parenchymal damage (Vogelbaum et al. 2005), respectively, using commercially available immunoradiometric assays (Ab, Sangtec Medical, Bromma, Sweden) (Bailey et al. 2006b). The intra- and interassay CV were both < 5% for NSE and < 9% and 4%, respectively, for S100β.

Blood gases

Venous blood (2–3 ml) was presented anaerobically to a blood gas analyser (ABL 5 Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark) for the determination of  and

and  . The intra- and interassay CV were both < 5%.

. The intra- and interassay CV were both < 5%.

Haemodynamic measurements

All recordings were performed in the supine position with the subject's head elevated to ∼30 deg.

Cardiovascular

Arterial haemoglobin oxygen saturation

was determined using finger-tip pulse oximetry (515C, Novametrix Medical Systems, Wallingford, CT, USA).

was determined using finger-tip pulse oximetry (515C, Novametrix Medical Systems, Wallingford, CT, USA).

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR)

MAP and HR were measured continuously using finger photoplethysmography (Portapress, TPD Biomedical Instrumentation, the Netherlands).

Cerebrovascular

Middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity (MCAv)

MCAv was estimated by the continuous measurement of backscattered Doppler signals from the right MCA using a 2 MHz pulsed trans-cranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound system (PMD 100, Spencer technologies, Washington, USA). Following standardized search techniques, the Doppler probe was secured over the trans-temporal window with a headband device (Spencer Technologies, Nicolet Instruments, Madison, WI, USA) to maintain optimal insonation position and maintained in this position for the duration of the study to avoid movement artefact (Appenzeller et al. 2006). MAP at the level of the MCA took into consideration the vertical distance from the heart (fourth intercostal space in the mid-clavicular line) to the TCD probe (i.e. hydrostatic pressure = vertical distance × 0.77 mmHg cm−1) (Ogoh et al. 2005). Cerebrovascular resistance (CVR) was calculated as MAP/MCAv and cerebrovascular conductance (CVC) as MCAv/MAP. The MAP and TCD waveforms were sampled continuously at 200 Hz using an analog-to-digital converter (Powerlab/16SP ML795; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) and stored on a personal computer for off-line computations.

Cerebral autoregulation (CA)

The dynamic relationship between fluctuations in MAP (input) and MCAv (output) was examined using two separate techniques (Sammons et al. 2007; Panerai, 2008), transfer function analysis (TFA) (Zhang et al. 1998) and rate of regulation using the thigh-cuff technique (Aaslid et al. 1989).

TFA

Beat-to-beat data of MAP and MCAv were recorded over 3 min steady-state transients prior to linear interpolation and re-sampling at 2 Hz for spectral analysis. The spectra of MAP and MCAv were calculated with a fast Fourier transformation algorithm and the transfer function calculated with a cross-spectral method as previously described (Zhang et al. 1998). The spectral power of MAP, MCAv, mean value of transfer function gain, phase and coherence function between MAP and MCAv were calculated in the very low (0.02–0.07 Hz), low (0.07–0.20 Hz) and high (0.20–0.30 Hz) frequency ranges. Data from the low frequency is presented specifically to identify dynamic CA since MAP fluctuations in this range are independent of respiratory frequency and reflect autoregulatory mechanisms (Diehl et al. 1995). The transfer gain and phase reflect the relative amplitude and time relationship between the changes in the two variables over a specified frequency range while the squared coherence function reflects the fraction of output power that can be linearly related to the input power at each frequency. Comparable to a correlation coefficient, coherence varies between 0 and 1. Transfer function gain estimates were incorporated as an ‘index’ of the ability of the cerebrovascular bed to buffer changes in MCAv induced by transient changes in MAP (Iwasaki et al. 2007). A reduction in gain indicated that larger changes in MAP lead only to small changes in MCAv, indicating effective autoregulation. Conversely, an elevation in gain was interpreted to mean that larger changes in MAP lead to similarly larger changes in MCAv, indicating impaired autoregulation.

Rate of regulation (RoR)

Bilateral thigh cuffs were connected to a Hokanson E20 (Bellevue, WA, USA) automatic inflator and inflated to 30 mmHg above the recorded systolic BP for 3 min. They were subsequently deflated (< 0.2 s) on three separate occasions with a 3 min recovery period and the RoR determined as the normalized change in CVR (per s) during 2.5 s following a step decrease in MAP as previously described (Aaslid et al. 1989).

AMS and headache scores

Individual symptoms of AMS were recorded by the principal investigator (DMB) using the Lake Louise (LL) (Roach et al. 1993) and Environmental Symptoms Questionnaire Cerebral Symptoms (ESQ-C) (Sampson et al. 1983) scoring systems and the mean scores calculated for analysis. The clinical diagnosis of AMS was confirmed if subjects presented with a combined total LL score (self assessment + clinical scores) of ≥ 5 points and ESQ-C score ≥ 0.7 points following 6 h passive exposure to 12% O2 as previously described (Bailey et al. 2006b). Based on our previous observations, we anticipated that this protocol would result in 50% of the subjects developing moderate to severe AMS (AMS+) with the remainder staying healthy (AMS–) (Bailey et al. 2006b). As a complementary measure, subjects were also asked to rate their cephalgia using a clinically validated visual analog scale (0–100 mm) (Iversen et al. 1989).

Statistical analysis

A prospective power calculation was performed to detect a ‘physiologically significant’ change (± 10% of the normoxic mean value based on pilot study data) in the main parameters of interest, specifically, A•−, plasma and RBC total NO, MCAv, and RoR assuming 80% power at the P < 0.05 level. Assuming a two-factor mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) design, our calculations indicated that eight subjects per group were sufficient to detect a difference either as a function of group (subjects with AMS (AMS+) versus subjects without AMS (AMS–)) or condition (hypoxia versus normoxia). Following confirmation of distribution normality using Shapiro–Wilks tests, data were analysed using a two-factor mixed ANOVA incorporating one between (group: AMS+versus AMS–) and one within (condition: normoxia versus hypoxia) subjects factor. Following a significant main effect and interaction, a paired samples t-test was employed to make post hoc comparisons at each level of the within-subjects factor. Between-group comparisons were assessed using independent samples t-tests applied to each level of the between-subjects factor. The relationship between selected variables was identified using a Pearson product moment correlation. Significance for all two-tailed tests was established at an α level of P < 0.05 and data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.).

Results

Clinical response

AMS

Fifty per cent of the subjects developed AMS (n= 9) with a corresponding increase in headache scores manifest as bilateral or diffuse pulsatile pain (Table 1).

Table 1.

Acute mountain sickness and headache

| AMS– (n= 9) | AMS+ (n= 9) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROUP: | |||||||

| CONDITION: | Normoxia | Hypoxia | Δ | Normoxia | Hypoxia | Δ | |

| LL (points) | 0 ± 1 | 4 ± 2 | 3 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 8 ± 3*† | 8 ± 3† | Group and condition main effects/Group × Condition interaction |

| ESQ-C (AU) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.2* | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 1.3*† | 2.0 ± 1.3† | Group and condition main effects/Group × Condition interaction |

| VAS (mm) | 1 ± 2 | 6 ± 9 | 6 ± 8 | 0 ± 0 | 47 ± 27*† | 47 ± 27† | Group and condition main effects/Group × Condition interaction |

Values are mean ±s.d.; AMS–, subjects without (AMS–) and with (AMS+) acute mountain sickness; main effect for group indicates a pooled (normoxia + hypoxia) difference (P < 0.05) between AMS–versus AMS+; main effect for condition indicates a pooled (AMS–+ AMS+) difference (P < 0.05) between normoxia versus hypoxia;

different within and

between groups (P < 0.05); LL, Lake Louise score; ESQ-C, Environmental Symptoms Questionnaire Cerebral Symptoms score in arbitrary units (AU); VAS, Visual Analogue Scale score; Δ, delta value (hypoxia minus normoxia).

Metabolic response

Oxidative stress: free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation

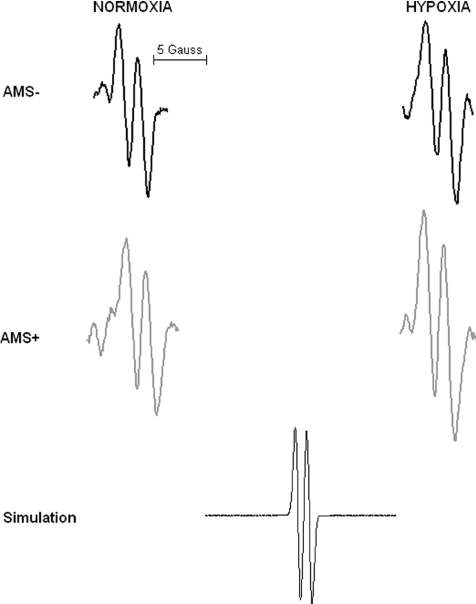

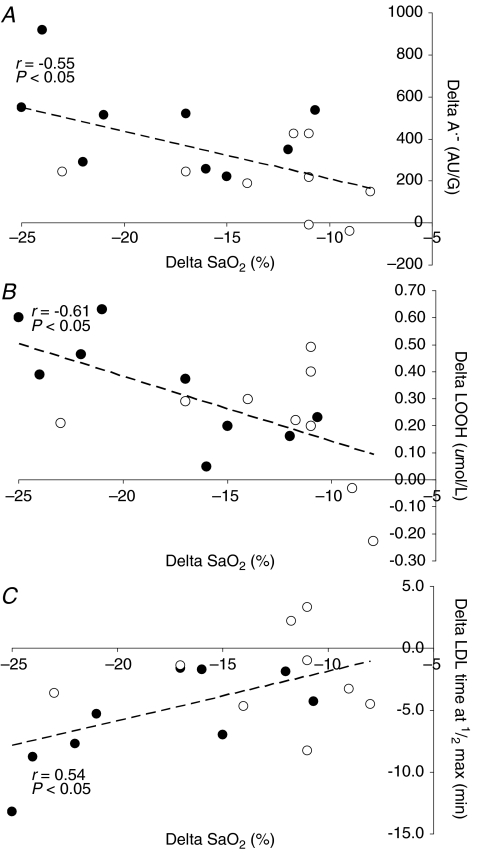

Hypoxia selectively increased A•− and LOOH in AMS+ (P < 0.05 versus AMS–) whereas no differences were observed in LDL oxidation (Table 2). Figure 1 provides a typical example of the differences observed in the EPR spectral intensity of A•− between AMS+ and AMS–. Changes in A•−, LOOH and LDL oxidation in hypoxia were consistently related to the decrease in  (Fig. 2A–C).

(Fig. 2A–C).

Table 2.

Oxidative stress

| AMS– (n= 9) | AMS+ (n= 9) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROUP: | |||||||

| CONDITION: | Normoxia | Hypoxia | Δ | Normoxia | Hypoxia | Δ | Main effect |

| Free radicals | |||||||

| A•− (AU/√G) | 1617 ± 285 | 1822 ± 348* | 205 ± 161 | 1809 ± 412 | 2271 ± 474*† | 461 ± 215† | Condition main effect/Group × Condition interaction |

| Lipid peroxidation | |||||||

| LOOH (μmol l−1) | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 0.82 ± 0.19 | 0.21 ± 0.22 | 0.69 ± 0.15 | 1.03 ± 0.20 | 0.34 ± 0.20 | Group and Condition main effects |

| LDL time at ½max (min) | 57.2 ± 4.5 | 54.8 ± 4.1 | –2.4 ± 3.6 | 60.8 ± 8.1 | 55.1 ± 8.4 | –5.7 ± 3.9 | Condition main effect |

| Antioxidants | |||||||

| Ascorbic acid (μmol l−1) | 42.1 ± 18.6 | 40.7 ± 21.1 | –1.5 ± 4.9 | 53.9 ± 21.2 | 40.5 ± 12.0* | –13.4 ± 12.6†* | Condition main effect Group × Condition interaction |

| α-Tocopherol (μmol l−1) | 22.2 ± 4.5 | 22.9 ± 4.7 | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 24.2 ± 2.8 | 24.9 ± 2.7 | 0.7 ± 0.8 | Condition main effect |

| γ-Tocopherol (μmol l−1) | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | –0.6 ± 0.6† | Condition main effect Group × Condition interaction |

| β-carotene (μmol l−1) | 0.42 ± 0.27 | 0.50 ± 0.30 | 0.09 ± 0.22 | 0.37 ± 0.27 | 0.46 ± 0.26 | 0.09 ± 0.11 | Condition main effect |

| Retinol (μmol l−1) | 1.88 ± 0.37 | 1.77 ± 0.33 | –0.11 ± 0.14 | 1.93 ± 0.24 | 1.80 ± 0.26 | –0.13 ± 0.11 | Condition main effect |

| Lycopene (μmol l−1) | 0.47 ± 0.26 | 0.71 ± 0.48 | 0.23 ± 0.47 | 0.53 ± 0.47 | 0.67 ± 0.41 | 0.15 ± 0.21 | Condition main effect |

Values are mean ±s.d.; AMS–, subjects without (AMS–) and with (AMS+) acute mountain sickness; main effect for group indicates a pooled (normoxia + hypoxia) difference (P < 0.05) between AMS–versus AMS+; main effect for condition indicates a pooled (AMS–+ AMS+) difference (P < 0.05) between normoxia versus hypoxia;

different within and

between groups (P < 0.05); A•−, ascorbate free radical expressed in arbitrary units (AU) width in Gauss (G); LOOH, lipid hydroperoxides; LDL, low density lipoprotein; Δ, delta value (hypoxia minus normoxia).

width in Gauss (G); LOOH, lipid hydroperoxides; LDL, low density lipoprotein; Δ, delta value (hypoxia minus normoxia).

Figure 1.

Typical electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of the ascorbate free radical (g= 2.00518; aH4= 1.76 Gauss) detected in the venous circulation of one subject without (AMS–) and a separate subject with (AMS+) acute mountain sickness in normoxia and following 6 h passive exposure to hypoxia (12% O2). All spectra were filtered and scaled identically. Simulation spectrum also illustrated.

Figure 2.

Relationship between the change (delta: hypoxia minus normoxia) in arterial haemoglobin oxygen saturation  and the ascorbate free radical (A•−: A), lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH: B) and low density lipoprotein (LDL)-oxidation (C) in subjects with (•) and without (^) acute mountain sickness.

and the ascorbate free radical (A•−: A), lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH: B) and low density lipoprotein (LDL)-oxidation (C) in subjects with (•) and without (^) acute mountain sickness.

Oxidative stress: antioxidants

Hypoxia decreased ascorbate and retinol whereas α-tocopherol, β-carotene and lycopene increased independent of AMS (Table 2). AMS was associated with a selective reduction in ascorbate and γ-tocopherol (P < 0.05 versus AMS–) whereas no differences were observed in any of the remaining antioxidants measured.

NO metabolites

A significant decline (∼50% in both groups) in total NO and NO•3 was observed in hypoxia independent of AMS (Table 3). However, there was a tendency towards a more marked increase in plasma NO•2, RSNO and intraerythrocytic concentration of RBC total NO and Hb-bound NO in AMS+ during hypoxia due predominantly to a lower baseline NO metabolite pool in normoxia (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nitric oxide (NO) metabolites

| GROUP: | AMS– (n= 9) | AMS+ (n= 9) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONDITION: | |||||||

| Normoxia | Hypoxia | Δ | Normoxia | Hypoxia | Δ | ||

| Plasma | |||||||

| Total NO (μmol) | 31.4 ± 14.9 | 17.2 ± 4.4* | –14.3 ± 14.6 | 29.9 ± 13.3 | 18.3 ± 9.9* | −11.5 ± 16.0 | Condition main effect/Group × Condition interaction |

| NO•3 (μmol) | 30.9 ± 14.9 | 16.7 ± 4.4* | −14.2 ± 14.6 | 29.4 ± 13.4 | 17.8 ± 9.9* | −11.6 ± 16.0 | Condition main effect/Group × Condition interaction |

| NO•2 (nmol) | 507.7 ± 177.9 | 436.8 ± 81.2 | −70.9 ± 213.8 | 479.4 ± 125.2 | 529.4 ± 120.8 | 50.0 ± 179.8 | — |

| RSNO (nmol) | 8.1 ± 7.1 | 10.8 ± 19.0 | 2.7 ± 19.4 | 7.4 ± 7.0 | 12.9 ± 21.3 | 5.5 ± 24.0 | — |

| RBC | |||||||

| Total NO (nmol) | 180.7 ± 156.5 | 183.6 ± 84.3 | 2.9 ± 111.5 | 118.1 ± 91.0 | 168.8 ± 72.2* | 50.8 ± 110.8 | Group × Condition interaction |

| Hb-bound NO (nmol) | 77.2 ± 89.3 | 79.7 ± 76.2 | 2.4 ± 77.7 | 35.9 ± 45.3 | 74.7 ± 36.4* | 38.7 ± 57.2† | Group × Condition interaction |

Values are mean ±s.d.; subjects without (AMS–) and with (AMS+) acute mountain sickness; main effect for group indicates a pooled (normoxia + hypoxia) difference (P < 0.05) between AMS–versus AMS+; main effect for condition indicates a pooled (AMS–+ AMS+) difference (P < 0.05) between normoxia versus hypoxia;

different within and †between groups (P < 0.05); NO•3, nitrate; NO•2, nitrite; RSNO, S-nitrosothiols; RBC, red blood cell; Hb (haemoglobin)-bound NO represents primarily nitrosyl haemoglobin (HbNO) +S-nitrosohaemoglobin (HbSNO) but also other NO metabolites stable to sulphanilamide treatment; Δ, delta value (hypoxia minus normoxia).

Brain-specific proteins

The plasma concentrations of S100β and NSE were not influenced by hypoxia or AMS (Table 4).

Table 4.

Brain-specific proteins

| AMS– (n= 9) | AMS+ (n= 9) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROUP: | ||||||

| CONDITION: | Normoxia | Hypoxia | Δ | Normoxia | Hypoxia | Δ |

| S100β (μg l−1) | 0.04 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.05 | 0.01 ± 0.05 | 0.03 ± 0.04 | 0.06 ± 0.07 | 0.03 ± 0.04 |

| NSE (μg l−1) | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | −0.5 ± 0.09 | 4.8 ± 1.1 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | −0.2 ± 0.9 |

Values are mean ±s.d.; subjects without (AMS–) and with (AMS+) acute mountain sickness; NSE, neuron specific enolase; Δ, delta value (hypoxia minus normoxia); no main effects observed (P > 0.05) for group (pooled normoxia + hypoxia) difference between AMS–versus AMS+ or condition (pooled AMS–+ AMS+) difference between normoxia versus hypoxia.

Blood gases

The decrease in  during hypoxia was more marked in AMS+ (−18.6 ± 5.4 versus AMS–: −12.8 ± 5.3 mmHg, P < 0.05) whereas no differences were observed in the decrease in

during hypoxia was more marked in AMS+ (−18.6 ± 5.4 versus AMS–: −12.8 ± 5.3 mmHg, P < 0.05) whereas no differences were observed in the decrease in  (−6.8 ± 3.2 versus AMS–: −8.0 ± 5.4 mmHg, P > 0.05).

(−6.8 ± 3.2 versus AMS–: −8.0 ± 5.4 mmHg, P > 0.05).

Haemodynamic response

Cardiovascular

The decrease in  observed during hypoxia was more marked in AMS+ (−18 ± 5%) compared to AMS– (−13 ± 5%, P < 0.05). There were no between group differences detected for HR (AMS–: +15 ± 14 beats min−1versus AMS+ : + 19 ± 9 beats min−1, P < 0.05) or MAP (AMS–: −2 ± 9 mmHg versus AMS+ : +7 ± 11 mmHg, P > 0.05).

observed during hypoxia was more marked in AMS+ (−18 ± 5%) compared to AMS– (−13 ± 5%, P < 0.05). There were no between group differences detected for HR (AMS–: +15 ± 14 beats min−1versus AMS+ : + 19 ± 9 beats min−1, P < 0.05) or MAP (AMS–: −2 ± 9 mmHg versus AMS+ : +7 ± 11 mmHg, P > 0.05).

Cerebrovascular

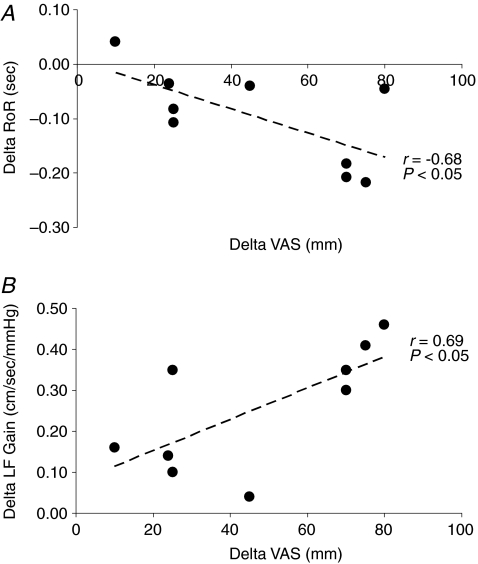

Hypoxia was associated with a mild reduction in MCAv due to an increase in CVR and corresponding reduction in CVC though these changes were independent of AMS (Table 5). In contrast, a selective increase in LF gain independent of any changes in phase or coherence and a decrease in RoR was observed in AMS+ (P < 0.05 versus AMS–) indicative of impaired CA. These changes were linearly related to the increase in headache scores, the primary symptom of AMS (Fig. 3A and B).

Table 5.

Cerebral haemodynamic function

| GROUP: | AMS– (n= 9) | AMS+ (n= 9) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONDITION: | Normoxia | Hypoxia | Δ | Normoxia | Hypoxia | Δ | |

| Haemodynamics | |||||||

| MCAv (cm s−1) | 60.1 ± 10.6 | 51.8 ± 9.2 | −8.3 ± 6.7 | 56.6 ± 10.7 | 53.2 ± 14.1 | −3.3 ± 14.4 | Condition main effect |

| CVR (mmHg cm−1 s−1) | 1.44 ± 0.30 | 1.60 ± 0.25 | 0.16 ± 0.22 | 1.44 ± 0.31 | 1.72 ± 0.49 | 0.28 ± 0.50 | Condition main effect |

| CVC (cm s−1 mmHg−1) | 0.72 ± 0.13 | 0.64 ± 0.10 | −0.08 ± 0.09 | 0.72 ± 0.16 | 0.63 ± 0.20 | −0.09 ± 0.22 | Condition main effect |

| Autoregulation | |||||||

| LF Gain (cm s−1 mmHg−1) | 1.22 ± 0.07 | 1.17 ± 0.09 | 0.03 ± 0.07 | 1.25 ± 0.07 | 1.43 ± 0.19*† | 0.26 ± 0.15† | Group main effect/Group × Condition interaction |

| LF phase (radians) | 1.17 ± 0.04 | 1.15 ± 0.09 | −0.03 ± 0.05 | 1.14 ± 0.07 | 1.13 ± 0.06 | −0.02 ± 0.04 | — |

| LF Coherence (units) | 0.73 ± 0.06 | 0.69 ± 0.06 | −0.01 ± 0.06 | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 0.68 ± 0.06 | −0.01 ± 0.03 | — |

| RoR (s) | 0.27 ± 0.08 | 0.32 ± 0.11 | 0.05 ± 0.15 | 0.28 ± 0.08 | 0.18 ± 0.05*† | −0.10 ± 0.09† | Group and Condition main effects/Group × Condition interaction |

Values are mean ±s.d.; subjects without (AMS–) and with (AMS+) acute mountain sickness; main effect for group indicates a pooled (normoxia + hypoxia) difference (P < 0.05) between AMS–versus AMS+; main effect for condition indicates a pooled (AMS–+ AMS+) difference (P < 0.05) between normoxia versus hypoxia;

different within and

between groups (P < 0.05); MCAv, middle cerebral artery velocity; CVR, cerebrovascular resistance; CVC, cerebrovascular conductance; RoR, rate of regulation; LF, low frequency (0.07–0.20Hz); Δ, delta value (hypoxia minus normoxia).

Figure 3.

Relationship between the change (delta: hypoxia minus normoxia) in the rate of regulation (RoR, A) and low frequency (LF) transfer function gain (B) and increase in headache scores measured using a visual analog scale (VAS) in subjects with acute mountain sickness.

Discussion

The present study examined if dynamic CA and BBB function would become compromised in lowlanders who develop AMS subsequent to a hypoxia-mediated alteration in systemic free radical metabolism. Consistent with this hypothesis, AMS+ subjects were more hypoxaemic and exhibited a greater increase in free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation compared to AMS– controls. A marked reduction in the total metabolite pool (plasma + RBC) occurred in both AMS+ and AMS– during hypoxia. However, the baseline plasma nitrite and RBC NO metabolite pool in normoxia was lower in AMS+ and a selective increase or normalization occurred with hypoxia. Consequently, a significant increase in these parameters was observed in AMS+. Dynamic CA was selectively impaired in AMS+ though we could not detect any evidence for cerebral hyper-perfusion, BBB disruption or neuronal–parenchymal damage. These findings suggest that disordered CA may be the consequence of altered redox homeostasis though the lack of autoregulatory breakthrough questions its pathophysiological significance in the setting of AMS.

Free radical metabolism

Our data provide convincing evidence for increased free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation in AMS+ which may be responsible for the mild impairment in CA observed. Mitochondrial superoxide (O•−2) formation has been shown to impair CA in the animal model subsequent to activation of KCa channels in cerebral vascular smooth muscle cells (Zagorac et al. 2005). In light of the low reduction potential associated with the A•−/ascorbate monanion (AH−) couple, any oxidising radical present in blood will react with AH− to form A•− (R + AH•−→ A•−+ R-H, E°′=+282 mV) (Buettner, 1993). Thus, the EPR detection of A•− provides direct evidence for increased free radical formation in AMS+ though it does not permit ‘upstream’ identification of the primary oxidising species.

The increase in A•− was preceded by a decrease in plasma ascorbate, which probably reflects selective consumption of this terminal reductant during the process of on-going oxidation. Ascorbate is considered the most effective water-soluble antioxidant in human plasma, with the capacity to ‘repair’O•−2, hydroxyl, alkyl, peroxyl and alkoxyl radicals (Sharma & Buettner, 1993). It can also re-cycle the tocopheroxyl radical back to the fully functional α-tocopherol isomer to ‘chain-break’ lipid peroxidation (Sharma & Buettner, 1993). The lack of change in α-tocopherol and selective depletion of the γ isomer is an interesting finding in light of the α-isomer's superior electron donating potential and previous reports of consumption during oxidative stress at an identical inspirate (Bailey et al. 2006b). This may be explained by the fact that the unsubstituted C-5 position of the γ-isomer renders it a more effective trap for lipophilic electrophiles such as RNS formed during inflammation (Jiang et al. 2001), which has previously been documented in AMS+ (Richalet et al. 1991).

The subsequent formation of LOOH and tendency towards enhanced LDL-oxidation confirms that lipid peroxidation also increased in AMS. AMS+ subjects were mildly more hypoxaemic which may render polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) membrane lipids more susceptible to molecular attack (Bailey et al. 2001a) as the inverse relationship between  , A•− and LOOH tentatively suggests. The notion that systemic hypoxia can trigger oxidative stress is intriguing in light of the fundamental importance of molecular O2 for formation of the peroxyl radical (PUFA + O2→ PUFA-OO•, k≈ 108m s−1) (Hasegawa & Patterson, 1978) and subsequent progression of the lipid peroxidation chain. However, this ‘oxygen paradox’ is supported by an accumulating body of evidence demonstrating how cellular hypoxia can accelerate mitochondrial ubisemiquinone and O•−2 formation (Guzy & Schumacker, 2006; Bailey et al. 2007) as a result of changes in the fluidity of the inner mitochondrial membrane (Clanton, 2007).

, A•− and LOOH tentatively suggests. The notion that systemic hypoxia can trigger oxidative stress is intriguing in light of the fundamental importance of molecular O2 for formation of the peroxyl radical (PUFA + O2→ PUFA-OO•, k≈ 108m s−1) (Hasegawa & Patterson, 1978) and subsequent progression of the lipid peroxidation chain. However, this ‘oxygen paradox’ is supported by an accumulating body of evidence demonstrating how cellular hypoxia can accelerate mitochondrial ubisemiquinone and O•−2 formation (Guzy & Schumacker, 2006; Bailey et al. 2007) as a result of changes in the fluidity of the inner mitochondrial membrane (Clanton, 2007).

The functional significance of increased peroxidation in the setting of AMS remains unclear. Thermodynamically, free radicals and associated reactive oxygen species (ROS) are eminently capable of causing structural damage to cellular membranes when in ‘physiological excess’ (Bailey et al. 2001b). Recently we suggested that a free radical-mediated down-regulation of Na+/K+-ATPase activity may be responsible for the neuronal swelling observed in AMS+ (Kallenberg et al. 2007). This may also prove the unifying mechanism responsible for the low ATP1A1 subunit mRNA expression and neurovascular headaches recently documented in patients with chronic mountain sickness (Appenzeller et al. 2005).

Alternatively, these biomolecules also serve as integral components of the signal transduction cascade that are physiologically essential in controlled amounts capable of initiating protective adaptation in the face of hypoxic stress for the maintenance of homeostasis (Bailey et al. 2001a; Guzy & Schumacker, 2006; Pryor et al. 2006; Burgoyne et al. 2007). The ability to maintain a steady state in the face of hypoxic stress is a fundamental property of life which presumably bestows advantages to those challenged by changes in barometric pressure with consequent arterial hypoxaemia (Beall, 2007). Thus, while speculative, the selective increase in oxidative stress in AMS+ may represent a physiological attempt to regain homeostasis in the face of more profound hypoxaemia.

It is interesting to note that acute hypoxia results in a very rapid (within minutes) increase in systemic oxidative stress (Bailey et al. 2001a) yet, despite clear evidence for arterial hypoxemia, there is a significant time delay before symptoms of AMS appear, typically in the order of 6 h, which is considered the minimal ‘threshold’ time for a clinical diagnosis to be confirmed (Bartsch et al. 2004; Bailey et al. 2006b). This may be related to progressive hyper-sensitisation of the trigeminovascular system (TVS) and subsequent pain perception. However, there are no studies to the best of our knowledge that have defined the kinetic between systemic ROS/RNS metabolism and AMS. From a purely biochemical perspective, it is important to emphasise that there are, nonetheless, interpretative limitations associated with this approach since the half-life of different ROS/RNS species is very different, which renders any correlation against subjective symptoms extremely challenging.

The pathophysiological implications of altered NO metabolism in the setting of AMS remains unclear though we are confident with our analytical approach since OBC represents the most sensitive method currently available for the molecular detection of blood-borne NO metabolites (Rassaf et al. 2004). It has been suggested that increased NO may predispose to AMS subsequent to hypoxia-mediated cerebral vasodilatation (van Mil et al. 2002) and/or following intracellular accumulation of hypoxic-inducible factor-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor, which all conspire to increase BBB permeability (Fischer et al. 1999) and raise intracranial pressure. Dietary supplementation with the NO substrate l-arginine has been shown to increase the incidence of AMS (Mansoor et al. 2005) which may be due to direct sensitisation and/or activation of the TVS (Strecker et al. 2002). Alternatively, hypoxia has been associated with a reduction in vascular NO bioavailability, which provides a molecular basis for the enhanced hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, vascular endothelial dysfunction and arterial hypoxaemia observed in high-altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPE), which is typically preceded by AMS (Bartsch et al. 2005).

In the present study, we observed a general decline in plasma total NO during hypoxia that was independent of AMS+. It is unlikely that this was caused by the oxidative inactivation of NO (O•−2+ NO•→ ONOO−, k≈ 109m s−1) (Nauser & Koppenol, 2002) in light of the prevailing oxidative stress since both subgroups experienced a similar reduction despite markedly different oxidative stress profiles. It was intriguing to note that both plasma NO•2 and RBC-bound NO were generally lower in AMS+ at the normoxic baseline time point, which cannot be attributed to differences in baseline systemic oxygenation status or oxidative stress. The increase during hypoxia may therefore represent ‘normalisation’ of the NO metabolite pool in response to the more marked arterial hypoxaemia observed. It must be noted, however, that if total NO metabolites are taken to reflect vascular NO production, then both AMS+ and AMS– show similar levels in hypoxia.

The selective increase in plasma NO•2 and anticipated rise in deoxyHb would be expected to increase the intraerythrocytic formation of NO metabolites as observed, specifically HbNO (NO2−+ Hb-FeII+ H+→ NO + Hb-FeIII+ OH−→ NO + Hb-FeII→ Hb-FeIINO) (Doyle et al. 1981) and increased S-nitrosation with β-Cys93 to yield HbSNO. While it has been proposed that both molecules may serve to conserve NO bioactivity in the hypoxic circulation (Jia et al. 1996), the changes observed did not translate into any differences in CBF.

Cerebral haemodynamic function

An inverse relationship was recently reported between dynamic CA assessed via the thigh-cuff technique and ESQ-C score at 4559 m (Van Osta et al. 2005), which equates to a comparable inspired partial pressure of oxygen  to that encountered in the present study. Our findings provide more convincing evidence for disordered CA as the reduction in RoR and elevated LF-gain between MAP and MCAv variability clearly suggest. Furthermore, both indices were positively related to the severity of headache, the primary symptom of AMS (Hackett & Roach, 2001). The two tests of CA are complementary since CA during transient hypotension is related to impaired static CA (Tiecks et al. 1995) and the elevated LF-gain reflects larger oscillations in MCAv for any given change in MAP. Together, these findings suggest that the ‘AMS brain’ was less capable of buffering rapid surges in MAP (in the order of < 10 mmHg since subjects were rested supine) and potentially more vulnerable to mild over-perfusion and thus by consequence, vasogenic oedema.

to that encountered in the present study. Our findings provide more convincing evidence for disordered CA as the reduction in RoR and elevated LF-gain between MAP and MCAv variability clearly suggest. Furthermore, both indices were positively related to the severity of headache, the primary symptom of AMS (Hackett & Roach, 2001). The two tests of CA are complementary since CA during transient hypotension is related to impaired static CA (Tiecks et al. 1995) and the elevated LF-gain reflects larger oscillations in MCAv for any given change in MAP. Together, these findings suggest that the ‘AMS brain’ was less capable of buffering rapid surges in MAP (in the order of < 10 mmHg since subjects were rested supine) and potentially more vulnerable to mild over-perfusion and thus by consequence, vasogenic oedema.

However, the physiological significance of such a mild impairment in CA as relates to AMS warrants critical evaluation. We observed a decrease rather than an increase in CBF during hypoxia which may be due in part, to hypoxic hyperventilation and hypocapnia-mediated cerebral vasoconstriction as indicated by the general decrease in  . Furthermore, we could not detect any molecular evidence for ongoing failure of the BBB or neuronal–parenchymal damage as indicated by the lack of change in S100β and NSE, established biomarkers of BBB ‘leak’ (Kanner et al. 2003b; Marchi et al. 2003) and structural brain ‘damage’ (Vogelbaum et al. 2005), respectively. These observations confirm more recent diffusion-weighted MRI (Kallenberg et al. 2007b, 2008; Schoonman et al. 2008) and Doppler (Van Osta et al. 2005) findings and argue against vasogenic oedema subsequent to compromised barrier integrity as a significant pathogenic event.

. Furthermore, we could not detect any molecular evidence for ongoing failure of the BBB or neuronal–parenchymal damage as indicated by the lack of change in S100β and NSE, established biomarkers of BBB ‘leak’ (Kanner et al. 2003b; Marchi et al. 2003) and structural brain ‘damage’ (Vogelbaum et al. 2005), respectively. These observations confirm more recent diffusion-weighted MRI (Kallenberg et al. 2007b, 2008; Schoonman et al. 2008) and Doppler (Van Osta et al. 2005) findings and argue against vasogenic oedema subsequent to compromised barrier integrity as a significant pathogenic event.

We remain confident that the lack of barrier disruption is not simply an artefact associated with an inadequate sample size since retrospective power calculations indicated values for these and other parameters of interest ranging between 70 and 99% at P < 0.05. Furthermore, we do not consider the insensitivity of the AMS scoring symptoms as a causative factor though the limitations of a questionnaire and subjective reporting of symptoms has unavoidable limitations. We have also scored headache, the hallmark symptom of AMS, using a clinically validated VAS scoring system (Iversen et al. 1989) to complement the AMS questionnaires. Furthermore, our clinical ‘cut-off’ for AMS was especially rigorous allowing us to identify those subjects with moderate to severe illness, thus eliminating the confusion that may arise when subjects suffer from mild or ‘borderline’ AMS, which is an unavoidable artefact of more traditional, conservative scoring systems (Roach et al. 1993).

Thus, it is equally conceivable that disordered CA bears no immediate relevance to the pathophysiology of AMS as previously suggested (Jansen et al. 2000) and merely represents an epiphenomenon secondary to free radical-mediated neurovascular dysfunction. Our observation that the ‘systemic NO pool’ in hypoxia is not different in AMS+ and failure to demonstrate any relationship with indices of cerebral haemodynamic function is consistent with a recent study demonstrating that inhibition of tonic NO formation does not influence dynamic CA (Zhang et al. 2004). However, we acknowledge the fact that we have focused on the systemic circulation and this may not necessarily reflect ‘regional’, that is cerebral, metabolism. Future studies should consider more invasive approaches that involve paired sampling of arterial and jugular venous blood combined with the global assessment of CBF using the Kety–Schmidt technique (Kety & Schmidt, 1948) to document the trans-cerebral exchange kinetics of free radicals to test this hypothesis more directly.

An alternative explanation borne out by the present findings is that metabolites of oxidative-nitrosative stress may serve as noxious agents directly capable of altering central and peripheral pain perception (Bailey et al. 2001b) and/or sensitising perivascular sensory nerves and activating trigeminovascular nocioceptors (Sanchez del Rio & Moskowitz, 1999) independent of any underlying haemodynamic or morphological change. This may depend to some extent on an individual's cranio-spinal axis CSF reserve volume and subsequent ability to buffer potential volumetric changes in the hypoxic brain. Despite clear evidence for increased oxidative stress (Harman, 1956; Finkel & Holbrook, 2000), advancing chronological age is also associated with cerebral atrophy and a subsequent reduction in susceptibility to AMS (Hackett et al. 1976). Future studies need to consider pharmacological approaches such as intravenous ascorbate prophylaxis to determine if redox activation of the TVS represents an important pathogenic event.

References

- Aaslid R, Lindegaard K, Sorteberg W, Nornes H. Cerebral autoregulation dynamics in humans. Stroke. 1989;20:45–52. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appenzeller O, Claydon VE, Gulli G, Qualls C, Slessarev M, Zenebe G, Gebremedhin A, Hainsworth R. Cerebral vasodilatation to exogenous NO is a measure of fitness for life at altitude. Stroke. 2006;37:1754–1758. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000226973.97858.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appenzeller O, Minko T, Qualls C, Pozharov V, Gamboa J, Gamboa A, Wang Y. Migraine in the Andes and headache at sea level. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:1117–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DM. Radical dioxygen: from gas to (unpaired!) electrons. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;543:201–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey D. Ascorbate, blood–brain barrier function and acute mountain sickness: a radical hypothesis. Wilderness Environ Med. 2004;15:231–233. doi: 10.1580/1080-6032(2004)15[234:ltte]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DM, Davies B, Young IS. Intermittent hypoxic training: implications for lipid peroxidation induced by acute normoxic exercise in active men. Clin Sci (Lond) 2001a;101:465–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DM, Davies B, Young IS, Hullin DA, Seddon PS. A potential role for free radical-mediated skeletal muscle soreness in the pathophysiology of acute mountain sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2001b;72:513–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DM, Lawrenson L, McEneny J, Young IS, James PE, Jackson SK, Henry R, Mathieu-Costello O, McCord JM, Richardson RS. Electron paramagnetic spectroscopic evidence of exercise-induced free radical accumulation in human skeletal muscle. Free Radic Res. 2007;41:182–190. doi: 10.1080/10715760601028867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey D, Raman S, McEneny J, Young I, Parham K, Hullin D, Davies B, McKeeman G, McCord J, Lewis M. Vitamin C prophylaxis promotes oxidative lipid damage during surgical ischemia-reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006a;40:591–600. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DM, Roukens R, Knauth M, Kallenberg K, Christ S, Mohr A, Genius J, Storch-Hagenlocher B, Meisel F, McEneny J, Young IS, Steiner T, Hess K, Bartsch P. Free radical-mediated damage to barrier function is not associated with altered brain morphology in high-altitude headache. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006b;26:99–111. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch P, Bailey DM, Berger MM, Knauth M, Baumgartner RW. Acute mountain sickness: controversies, advances and future directions. High Altitude Med Biol. 2004;5:110–124. doi: 10.1089/1527029041352108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch P, Mairbaurl H, Maggiorini M, Swenson ER. Physiological aspects of high-altitude pulmonary edema. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1101–1110. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01167.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall CM. Two routes to functional adaptation: Tibetan and Andean high-altitude natives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8655–8660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701985104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner GR. The pecking order of free radicals and antioxidants: lipid peroxidation, α-tocopherol, and ascorbate. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:535–543. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner GR, Jurkiewicz BA. Ascorbate free radical as a marker of oxidative stress: an EPR study. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993;14:49–55. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90508-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne JR, Madhani M, Cuello F, Charles RL, Brennan JP, Schroder E, Browning DD, Eaton P. Cysteine redox sensor in PKGIa enables oxidant-induced activation. Science. 2007;317:1393–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.1144318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catignani GL, Bieri JG. Simultaneous determination of retinol and alpha-tocopherol in serum or plasma by liquid chromatography. Clin Chem. 1983;29:708–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clanton TL. Hypoxia-induced reactive oxygen species formation in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:2379–2388. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01298.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl RR, Linden D, Lucke D, Berlit P. Phase relationship between cerebral blood flow velocity and blood pressure: a clinical test of autoregulation. Stroke. 1995;26:1801–1804. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.10.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle MP, Pickering RA, DeWeert TM, Hoekstra JW, Pater D. Kinetics and mechanism of the oxidation of human deoxyhemoglobin by nitrites. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:12393–12398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing JF, Janero DR. Specific S-nitrosothiol (thionitrite) quantification as solution nitrite after vanadium (III) reduction and ozone-chemiluminescent detection. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:621–628. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Clauss M, Wiesnet M, Renz D, Schaper W, Karliczek GF. Hypoxia induces permeability in brain microvessel endothelial cells via VEGF and NO. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1999;276:C812–C820. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.4.C812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryglewsky RJ, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Superoxide anion is involved in the breakdown of endothelium-derived vascular relaxing factor. Nature. 1986;320:454–456. doi: 10.1038/320454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzy RD, Schumacker PT. Oxygen sensing by mitochondria at complex III: the paradox of increased reactive oxygen species during hypoxia. Exp Physiol. 2006;91:807–819. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.033506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett PH, Rennie D, Levine HD. The incidence, importance, and prophylaxis of acute mountain sickness. Lancet. 1976;2:1149–1155. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91677-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett PH, Roach RC. High-altitude illness. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:107–114. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol. 1956;11:298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa K, Patterson LK. Pulse radiolysis studies in model lipid systems: formation and behavior of peroxy radicals in fatty acids. Photochem Photobiol. 1978;28:817–823. [Google Scholar]

- Hausladen A, Rafikov R, Angelo M, Singel DJ, Nudler E, Stamler JS. Assessment of nitric oxide signals by triiodide chemiluminescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2157–2162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611191104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen HK, Olesen J, Tfelt-Hansen P. Intravenous nitroglycerin as an experimental model of vascular headache. Basic characteristics. Pain. 1989;38:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K-I, Levine BD, Zhang R, Zuckerman JH, Pawelczyk JA, Diedrich A, Ertl AC, Cox JF, Cooke WH, Giller CA, Ray CA, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Jr, Baisch FJ, Eckberg DL, Robertson D, Biaggioni I, Blomqvist CG. Human cerebral autoregulation before, during and after spaceflight. J Physiol. 2007;579:799–810. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.119636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen GFA, Krins A, Basnyat B, Bosch A, Odoom JA. Cerebral autoregulation in subjects adapted and not adapted to high altitude. Stroke. 2000;31:2314–2318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Bonaventura C, Bonaventura J, Stamler JS. S-nitrosohaemoglobin: a dynamic activity of blood involved in vascular control. Nature. 1996;380:221–226. doi: 10.1038/380221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Christen S, Shigenaga MK, Ames BN. γ-Tocopherol, the major form of vitamin E in the US diet, deserves more attention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:714–722. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.6.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallenberg K, Bailey DM, Christ S, Mohr A, Roukens R, Menold E, Steiner T, Bartsch P, Knauth M. Magnetic resonance imaging evidence of cytotoxic cerebral edema in acute mountain sickness. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1064–1071. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallenberg K, Dehnert C, Dorfler A, Schellinger PD, Bailey DM, Knauth M, Bartsch PD. Microhemorrhages in nonfatal high-altitude cerebral edema. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1635–1642. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner AA, Marchi N, Fazio V, Mayberg MR, Koltz MT, Siomin V, Stevens GH, Masaryk T, Aumayr B, Ayumar B, Vogelbaum MA, Barnett GH, Janigro D. Serum S100β: a noninvasive marker of blood–brain barrier function and brain lesions. Cancer. 2003b;97:2806–2813. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner A, Marchi N, Fazio V, Mayberg M, Koltz M, Siomin V, Stevens G, Masaryk T, Ayumar B, Vogelbaum M, Barnett G, Janigro D. Serum S100β: a noninvasive marker of blood–brain barrier function and brain lesions. Cancer. 2003a;97:2806–2813. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kety SS, Schmidt CF. The nitrous oxide method for the quantitative determination of cerebral blood flow in man: theory, procedure and normal values. J Clin Invest. 1948;27:476–484. doi: 10.1172/JCI101994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassen NA, Harper AM. Letter: High-altitude cerebral oedema. Lancet. 1975;2:1154. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)91053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher AR, Milsom AB, Gunaruwan P, Abozguia K, Ahmed I, Weaver RA, Thomas P, Ashrafian H, Born GVR, James PE, Frenneaux MP. Hypoxic modulation of exogenous nitrite-induced vasodilation in humans. Circulation. 2008;117:670–677. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.719591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor JK, Morrissey BM, Walby WF, Yoneda KY, Juarez M, Kajekar R, Severinghaus JW, Eldridge MW, Schelegle ES. L-Arginine supplementation enhances exhaled NO, breath condensate VEGF, and headache at 4,342 m. High Alt Med Biol. 2005;6:289–300. doi: 10.1089/ham.2005.6.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchi N, Rasmussen P, Kapural M, Fazio V, Kight K, Mayberg M, Kanner A, Ayumar B, Albensi B, Cavaglia M, Janigro D. Peripheral markers of brain damage and blood–brain barrier dysfunction. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2003;21:109–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell I, McEneny J, Trimble E. A rapid method for measurement of the susceptibility to oxidation of low-density lipoprotein. Ann Clin Biochem. 1995;32:167–174. doi: 10.1177/000456329503200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauser T, Koppenol WH. The rate constant of the reaction of superoxide with nitrogen monoxide: approaching the diffusion limit. J Phys Chem A. 2002;106:4084–4086. [Google Scholar]

- Ogoh S, Brothers RM, Barnes Q, Eubank WL, Hawkins MN, Purkayastha S, O-Yurvati A, Raven PB. The effect of changes in cardiac output on middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity at rest and during exercise. J Physiol. 2005;569:697–704. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panerai RB. Cerebral autoregulation: from models to clinical applications. Cardiovasc Eng. 2008;8:42–59. doi: 10.1007/s10558-007-9044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor WA, Houk KN, Foote CS, Fukuto JM, Ignarro LJ, Squadrito GL, Davies KJA. Free radical biology and medicine: it's a gas, man! Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R491–R511. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00614.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassaf T, Feelisch M, Kelm M. Circulating NO pool: assessment of nitrite and nitroso species in blood and tissues. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richalet JP, Hornych A, Rathat C, Aumont J, Larmignat P, Remy P. Plasma prostaglandins, leukotrienes and thromboxane in acute high altitude hypoxia. Respir Physiol. 1991;85:205–215. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(91)90062-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach RC, Bartsch P, Hackett PH, Oelz O. The Lake Louise acute mountain sickness scoring system. In: Sutton JR, Coates J, Houston CS, editors. Hypoxia and Molecular Medicine. Burlington: Queen City Printers; 1993. pp. 272–274. [Google Scholar]

- Roach RC, Hackett PH. Frontiers of hypoxia research: acute mountain sickness. J Exp Biol. 2001;204:3161–3170. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.18.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SC, Khalatbari A, Gapper PW, Frenneaux MP, James PE. Detection of human red blood cell bound nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26720–26728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SC, Khalatbari A, Datta BN, Ellery S, Paul V, Frenneaux MP, James PE. NO metabolite flux across the human coronary circulation. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammons EL, Samani NJ, Smith SM, Rathbone WE, Bentley S, Potter JF, Panerai RB. Influence of noninvasive peripheral arterial blood pressure measurements on assessment of dynamic cerebral autoregulation. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:369–375. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00271.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson JB, Cymerman A, Burse RL, Maher JT, Rock PB. Procedures for the measurement of acute mountain sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1983;54:1063–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez del Rio M, Moskowitz MA. High altitude headache. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;474:145–153. Lessons from headaches at sea level. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonman GG, Sandor PS, Nirkko AC, Lange T, Jaermann T, Dydak U, Kremer C, Ferrari MD, Boesiger P, Baumgartner RW. Hypoxia-induced acute mountain sickness is associated with intracellular cerebral edema: a 3 T magnetic resonance imaging study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:198–206. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Buettner G. Interaction of vitamin C and vitamin E during free radical stress in plasma: an ESR study. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993;14:649–653. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90146-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecker T, Dux M, Messlinger K. Nitric oxide releases calcitonin-gene-related peptide from rat dura mater encephali promoting increases in meningeal blood flow. J Vasc Res. 2002;39:489–496. doi: 10.1159/000067206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz HM, Khan N, Khramtsov VV. Use of electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy to evaluate the redox state in vivo. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1757–1771. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurnham DI, Smith E, Flora PS. Concurrent liquid-chromatographic assay of retinol, alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene, alpha-carotene, lycopene, and beta-cryptoxanthin in plasma, with tocopherol acetate as internal standard. Clin Chem. 1988;34:377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiecks FP, Lam AM, Aaslid R, Newell DW. Comparison of static and dynamic cerebral autoregulation measurements. Stroke. 1995;26:1014–1019. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Mil AHM, Spilt A, van Buchem MA, Bollen ELEM, Teppema L, Westendorp RGJ, Blauw GJ. Nitric oxide mediates hypoxia-induced cerebral vasodilation in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:962–966. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00616.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Osta A, Moraine J-J, Melot C, Mairbaurl H, Maggiorini M, Naeije R. Effects of high altitude exposure on cerebral hemodynamics in normal subjects. Stroke. 2005;36:557–560. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000155735.85888.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelbaum MA, Masaryk T, Mazzone P, Mekhail T, Fazio V, McCartney S, Marchi N, Kanner A, Janigro D. S100β as a predictor of brain metastases: brain versus cerebrovascular damage. Cancer. 2005;104:817–824. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier JP, Keck E. Fluorimetric assay of vitamin C in biological materials using a centrifugal analyser with fluorescence attachment. J Micronutr Anal. 1993;5:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- White RP, Vallance P, Markus HS. Effect of inhibition of nitric oxide synthase on dynamic cerebral autoregulation in humans. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;99:555–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff SP. Ferrous ion oxidation in presence of ferric ion indicator xylenol orange for measurement of hydroperoxides. Methods Enzymol. 1994;233:183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Yang BK, Vivas EX, Reiter CD, Gladwin MT. Methodologies for the sensitive and specific measurement of S-nitrosothiols, iron-nitrosyls, and nitrite in biological samples. Free Radic Res. 2003;37:1–10. doi: 10.1080/1071576021000033112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagorac D, Yamaura K, Zhang C, Roman RJ, Harder DR. The effect of superoxide anion on autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. Stroke. 2005;36:2589–2594. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000189997.84161.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Wilson TE, Witkowski S, Cui J, Crandall CG, Levine BD. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase does not alter dynamic cerebral autoregulation in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H863–H869. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00373.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Zuckerman JH, Giller CA, Levine BD. Transfer function analysis of dynamic cerebral autoregulation in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;274:H233–H241. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.1.h233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]