Abstract

Hypoxia elevates splanchnic sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) with differential effects during inspiration and expiration by unresolved central mechanisms. We examined the hypothesis that cardiovascular-related neurones in the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM) contribute to the complex sympathetic response to hypoxia. In chloralose-anaesthetized, ventilated, vagotomized rats, acute hypoxia (10% O2, 60 s) evoked an increase in SNA (103 ± 12%) that was characterized by a decrease in activity during early inspiration followed by a prominent rise during expiration. Some recorded baro-activated CVLM neurones (n= 13) were activated by hypoxia, and most of these neurones displayed peak activity during inspiration that was enhanced during hypoxia. In contrast, other baro-activated CVLM neurones were inhibited during hypoxia (n= 6), and most of these neurones showed peak activity during expiration prior to the onset of hypoxia. Microinjection of the glutamate antagonist kynurenate into the CVLM eliminated the respiratory-related fluctuations in SNA during hypoxia and exaggerated the magnitude of the sympathetic response. In contrast, microinjection of a GABAA antagonist (bicuculline or gabazine) into the CVLM dramatically attenuated the sympathetic response to hypoxia. These data suggest the response to hypoxia in baro-activated CVLM neurones is related to their basal pattern of respiratory-related activity, and changes in the activity of these neurones is consistent with a contribution to the respiratory-related sympathetic responses to hypoxia. Furthermore, both glutamate and GABA in the CVLM contribute to the complex sympathetic response to acute hypoxia.

Stimulation of peripheral chemoreceptors by inhalation of hypoxic air or systemic injection of cyanide produces physiological responses to promote enhanced gas exchange at the lungs and maintain cardiovascular function. To achieve this effect, central respiratory drive is increased and sympathetic vasomotor nerves are prominently activated (Marshall, 1994; Guyenet, 2000). Elimination of inputs from carotid sinus nerves or inhibition of the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) prevents the sympathetic response to acute hypoxia, suggesting these structures are necessary for the hypoxia-induced increase in sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) (Czyzyk-Krzeska & Trzebski, 1990; Koshiya et al. 1993). Additionally, brain transection experiments show that neural structures caudal to the inferior colliculus are sufficient for the full expression of the sympathetic chemoreceptor reflex (Koshiya & Guyenet, 1994).

Hypoxia-induced activation of SNA is complex with respiratory-related oscillations superimposed upon tonic, respiratory-independent changes that probably occur by distinct central mechanisms (Guyenet & Koshiya, 1995; Guyenet, 2000). Specifically, SNA is selectively reduced during inspiration, but massively activated during expiration to contribute to the overall rise in SNA (Czyzyk-Krzeska & Trzebski, 1990; Dick et al. 2004). Neurones in the caudal nucleus of the tractus solitarius (NTS) receive projections from the chemoreceptor afferent nerves, increase their discharge upon chemoreceptor stimulation, and have projections toward presympathetic neurones in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) (Mifflin, 1993; Koshiya & Guyenet, 1996). These NTS neurones are not modulated by the central respiratory generator, implying that the direct projection from the NTS to the RVLM could yield the tonic, but not respiratory-related changes in SNA during acute hypoxia (Mifflin, 1993). The mechanisms responsible for producing hypoxia-induced, respiratory-related changes in RVLM neurones (McAllen, 1992; Koshiya et al. 1993; Koganezawa & Terui, 2007) and in peripheral sympathetic nerves (Czyzyk-Krzeska & Trzebski, 1990; Guyenet, 2000; Dick et al. 2004) are not well understood.

Although the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM) does not appear to be essential for the tonic hypoxia-induced increases in SNA, inhibition of neuronal activity in the region of the CVLM eliminates respiratory-related oscillations in SNA and RVLM neurones during acute hypoxia (Koshiya & Guyenet, 1996). However, the identity of the critical CVLM neurones is not known. The CVLM contains GABAergic neurones that provide tonic and baroreflex-driven inhibition of the activity of presympathetic RVLM neurones (Schreihofer & Guyenet, 2003), and these neurones may also contribute to respiratory-related changes in SNA. Baro-activated GABAergic CVLM neurones display diverse respiratory-related activity inversely related to patterns observed in individual RVLM neurones (Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006). In addition, selective blockade of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the CVLM region modifies the respiratory-related modulation of RVLM neurones, SNA and arterial pressure (AP) (Miyawaki et al. 1996). We hypothesized that baro-activated CVLM neurones respond to acute hypoxia in a manner that could contribute the diverse respiratory-related changes in SNA during acute hypoxia. Furthermore, because antagonism of glutamate and GABA receptors in the CVLM alters AP via changes in SNA (Sved et al. 1985; Schreihofer et al. 2005), and these neurotransmitters are also common to the neural network that enhances central respiratory drive during hypoxia (Burton & Kazemi, 2000), we hypothesized that selective inhibition of these excitatory or inhibitory influences upon the CVLM would alter the sympathetic responses to hypoxia.

Methods

All experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Medical College of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgical preparation

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (275–375 g, Harlan, http://www.harlan.com) were anaesthetized with 5% isoflurane in 100% O2 and maintained at 1.9% for surgical procedures as previously described (Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006). A femoral vein was cannulated for injection of drugs, and a brachial artery was cannulated for measurement of arterial pressure (AP). The trachea was cannulated for artificial ventilation (Model 683, Harvard Apparatus, http://www.harvardapparatus.com). Rectal temperature was monitored and maintained at 37°C (TC-1000, Charles Ward). After confirmation of adequate anaesthesia level (absence of a corneal reflex or < 10 mmHg increase to firm toe pinch) the animal was given a neuromuscular blocker (pancuronium, 1 mg kg−1i.v., Abbott Laboratories), and then the cervical vagus nerves were sectioned bilaterally. An inflatable snare was positioned around the abdominal aorta for the production of rapid increases in upper body AP (Schreihofer & Guyenet, 2003; Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006) to test CVLM neurones for barosensitivity. The rat was placed in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, http://www.kopfinstruments.com) with the bite bar at −11 mm. The left splanchnic sympathetic nerve was isolated, placed on two bared silver wires (250 μm bare diameter, A-M systems, http://www.a-msystems.com) and embedded in polyvinylsiloxane (Darby Dental, http://www.darbydental.com). The dorsal surface of the brain stem was exposed by a partial occipital craniotomy, and the mid thoracic spinal cord was clamped to ensure stable brain stem recordings. The left phrenic nerve was isolated from a dorsolateral approach, placed on silver wires, cut distally, and embedded in polyvinylsiloxane. After completion of surgery, α-chloralose (30 mg ml−1 in 2% sodium borate) was slowly infused (60 mg kg−1i.v. initial dose, 20 mg kg−1 hourly supplements) while isoflurane was terminated. Animals were allowed to stabilize for 30 min before the onset of recordings. At each hour the adequacy of anaesthesia was verified, and then pancuronium was supplemented (0.3 mg kg−1).

Rats were ventilated with 100% oxygen to minimize baseline chemoreceptor activity. Parameters were adjusted to maintain end-tidal CO2 between 4.5 and 5.5% (1 ml (100 g body weight)−1 at ∼60 breaths min−1; CapStar-100, Charles Ward Electronics, http://www.cwe-inc.com). To separate coupling between central respiratory drive and physical ventilation, the ventilation rate was adjusted slightly to dissociate end-tidal CO2 waves from bursts of phrenic nerve discharge (PND).

Extracellular recordings of CVLM neurones

Extracellular recordings from individual CVLM neurones were performed as previously described (Schreihofer & Guyenet, 2003; Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006; Mobley et al. 2006). Glass electrodes (World Precision Instruments, http://www.wpiinc.com) filled with 1.5% biotinamide (Molecular Probes, http://www.probes.invitrogen.com) in 0.5 m sodium acetate were pulled to an optimal resistance of 10–20 MΩ measured in vivo. The signal was amplified and filtered (Neuroprobe 1600, A-M Systems and Neurolog, Digitimer), and the firing rate was counted using a spike trigger (Neurolog; Schreihofer & Guyenet, 2003; Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006).

In agreement with previous studies (Schreihofer & Guyenet, 2003; Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006; Mobley et al. 2006), CVLM neurones activated by increased AP were located 0.9–1.4 mm rostral and 1.8–2.0 mm lateral from calamus scriptorius and 2.4–2.8 mm ventral to the dorsal surface of the brain stem. Only neurones meeting the following criteria were considered for study: (1) spontaneous activity under resting conditions, (2) brisk increase in discharge with increased AP, (3) strong modulation by the AP pulse during increased AP, (4) no obvious respiratory-related activity (but observed with phrenic-triggered histograms), and (5) found ventral to respiratory-related neurones with obvious on–off patterns of activity. Neurones with these characteristic have been shown to be GABAergic and have axonal projections toward the RVLM (Jeske et al. 1993; Schreihofer & Guyenet, 2003; Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006).

Microinjections into the CVLM and RVLM

Microinjections were delivered by pulled glass pipettes with a tip diameter of 40–50 μm. All drugs were dissolved in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF in mm: 133.3 NaCl, 3.4 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.3 CaCl2, 3.4 glucose, 0.6 Na2HPO4, 32 NaHCO3 at pH 7.4) and slowly injected over 30 s in a 100 nl volume (Picospritzer III, Parker Instrumentation). Glutamate (1 nmol) was microinjected into the pressor region of the RVLM as previously described (1.7 mm lateral from the midline, 1.6 mm rostral to calamus scriptorius, and 2.9 mm below the dorsal surface of the brain stem with the pipette angled 20 deg rostrally; Schreihofer et al. 2005). Microinjections into the CVLM were placed where baro-activated neurones are found (1.0 mm rostral, 1.8 mm lateral from calamus scriptorius; 2.6 mm ventral to the dorsal surface of the brain stem; Mobley et al. 2006). The GABAA agonist, muscimol (100 pmol) was injected to globally inhibit CVLM neurones. Kynurenate (5 nmol) was microinjected to antagonize ionotropic glutamate receptors, bicuculline (50 pmol) or gabazine (135 pmol) was injected to antagonize GABAA receptors, and strychnine (200 pmol) was injected to antagonize glycine receptors. Artificial cerebrospinal fluid was microinjected as a vehicle control.

In a subset of rats the drugs were mixed with 5% red or green latex microspheres (Lumiphore) for histological confirmation of the injection sites. Rats were perfused with 4% formaldehyde and brains were stored in the same fixative for 48 h. The brain stems were sectioned coronally at 50 μm using a Vibratome. Sections were mounted onto glass slides, and coverslips were affixed with Krystalon (VWR). Injection sites were visualized under epifluorescence using an Olympus microscope (BX60). Using the Neurolucida system and a Ludl motor-driven stage, the outlines of the sections containing injection sites were drawn along with the injection sites and nearby landmarks as previously described (Schreihofer & Guyenet, 2003).

Activation of the peripheral chemoreflex

Peripheral chemoreceptors were stimulated in two ways to elicit the characteristic sympathetic response. To induce hypoxia the ventilated 100% O2 was replaced with 10% O2 (balanced with nitrogen) for 60 s. In addition, peripheral chemoreceptors were stimulated by injection of sodium cyanide (100 μg kg−1, i.v.). Given the exquisite sensitivity of the CVLM neurones to changes in AP, these two stimuli provided the means to stimulate SNA during opposing effects on AP.

Data analyses

The analog signals were converted to a digital output (Micro1401, Cambridge Electronic Design, http://www.ced.co.uk), and all physiological variables were viewed online (Spike2 software, Cambridge). The nerve activities were sampled at 4 kHz and filtered (SNA at 10 Hz to 3 kHz and PND at 30 Hz to 3 kHz with a 60 Hz notch filter, Differential AC Amplifier 1700, A-M Systems; Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006). The filtered raw SNA was amplified 25 000 times such that the largest bursts were in the volt range, and all experiments were performed with the same amplification settings. The SNA and PND were full-wave rectified using the Spike2 rectify function and averaged using the Spike2 smooth function (0.1 s bins). Phrenically triggered histograms of SNA and CVLM activity were created using 30 s of baseline activity and 30 s of activity during hypoxia (0.1 s bins, 4 s window, 20–25 sweeps). Pulse-triggered histograms of CVLM activity were created using 300 s of baseline activity (0.01 s bins, 1 s window, ∼1500 sweeps).

Extracellular CVLM neuronal activity was sampled at 8 kHz and filtered (300 Hz to 5 kHz, NeuroLog System, Digitimer Ltd, http://www.digitimer.com; Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006). The CVLM unit activity was counted in 1 s bins. Histograms were created triggering from the onset of PND (Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006).

Statistics

Voltage changes in SNA and firing rate of CVLM neurones with hypoxia and cyanide were analysed by paired t tests. For statistical analysis of changes in SNA, the voltages measured from full-wave-rectified raw signals were utilized. Baseline SNA was measured as the average voltage during the 30 s prior to a physiological manipulation, and minimum SNA (noise) was determined at the end of an experiment after the SNA was totally silenced by injection of clonidine (100 μg kg−1, Sigma).

The relationship between the respiratory-related pattern of CVLM unit activity prior to hypoxia and type of response to hypoxia was examined by χ2 analysis.

Results

Physiological responses to stimulation of the peripheral chemoreceptors

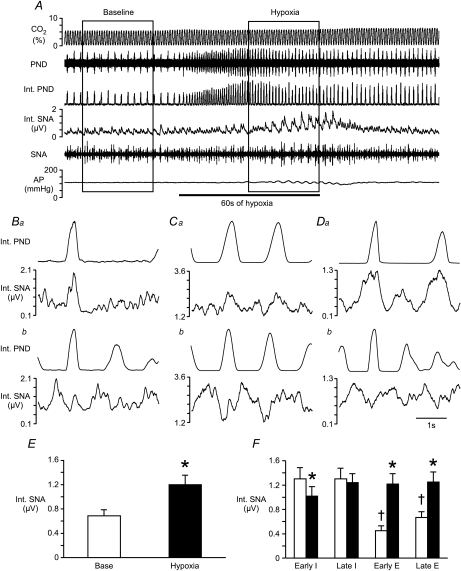

Before exposure to hypoxia, a predominant peak in activity coincident with inspiration was evident in SNA (Fig. 1A, B, C, D and F). Hypoxia evoked a 103 ± 12% increase in mean SNA (n= 25, P < 0.05; Fig. 1E) with strong oscillations related to the respiratory cycle (see Fig. 1A). During hypoxia SNA was reduced during early inspiration and elevated during both phases of expiration (Fig. 1F), as previously reported (Dick et al. 2004). In the same animals, injection of sodium cyanide briefly increased SNA 487 ± 53% (see Fig. 2A). Evaluation of the respiratory-related fluctuations in SNA was not possible during this manipulation due to the short duration of the response.

Figure 1. Effects of hypoxia on phrenic and splanchnic sympathetic nerve activity.

A, raw tracings of end-tidal CO2, phrenic nerve discharge (PND), splanchnic sympathetic nerve activity (SNA), integrated (Int.) nerve activities, and arterial pressure (AP) at baseline and during the hypoxia protocol. Ba, Ca and Da, phrenic-triggered histograms from 3 rats to display SNA in relation to central respiratory drive (made with 30 s of baseline SNA and PND). Bb, Cb and Db, the final 30 s of activity during 60 s of 10% O2 inhalation was used to evaluate SNA in relation to PND during hypoxia in the same 3 rats from Ba, Ca and Da. E, mean SNA collected for 30 s at baseline and during hypoxia (inside boxes in A). F, mean SNA was evaluated during the early inspiratory (Early I), late inspiratory (Late I), early expiratory (Early E) and late expiratory (Late E) phases of respiration. Open bars represent SNA at baseline. Filled bars represent SNA during hypoxia. *Significant difference from baseline value during that period. †Significant difference from values during both phases of inspiration.

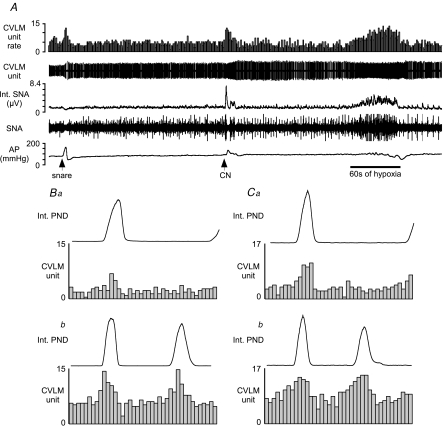

Figure 2. Examples of baro-activated caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM) neurones activated by hypoxia.

A, this CVLM neurone was activated by raising AP (snare), i.v. injection of sodium cyanide (CN), and inhalation of hypoxic air (bar = 60 s of hypoxia). B, phrenic-triggered histogram of CVLM neuronal activity using 30 s of baseline activity (Ba) and 30 s during hypoxia (Bb). C, phrenic-triggered histogram of another baro-activated, hypoxia-activated CVLM neurone at baseline (Ca) and during hypoxia (Cb). The CVLM units were counted in 0.1 s bins.

Hypoxia produced an initial wavering of AP followed by a significant decrease (−26 ± 4 mmHg) during the latter half of the 60 s stimulus (see Fig. 2A). In contrast, injection of cyanide increased AP (36 ± 4 mmHg) coincident with the burst in SNA (see Fig. 2A). Acute hypoxia did not alter end-tidal CO2 (see Fig. 1A).

Responses of baro-activated CVLM neurones to hypoxia and cyanide

Baro-activated, pulse-modulated CVLM neurones displayed diverse patterns of respiratory-related activity (Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006) and responses to activation of peripheral chemoreceptors by ventilation with hypoxic air or injection of sodium cyanide. In all cases, the response of a CVLM neurone to hypoxia was qualitatively mimicked by injection of sodium cyanide despite opposing effects on AP.

Thirteen recorded baro-activated CVLM neurones displayed increased firing rate during hypoxia and following intravenous injection of cyanide (Fig. 2; Table 1). Under basal conditions of 100% O2, most baro-activated CVLM neurones activated by hypoxia (11/13) exhibited a clear peak in neuronal activity during the inspiratory phase of respiration (Fig. 2Ba and Ca). The inspiratory-related activity of these CVLM neurones was maintained or enhanced during hypoxia (Fig. 2Bb and Cb).

Table 1.

Firing rates of baro-activated caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM) neurones at baseline and during stimulation of peripheral chemoreflex

| Firing rate | Baseline (spikes s−1) | During hypoxia (spikes s−1) | During cyanide (spikes s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activated CVLM neurones (n= 13) | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 9.4 ± 1.2* | 11.8 ± 1.3* |

| (0.9–6.9) | (2.9–14.1) | (7.3–20) | |

| Inhibited CVLM neurones (n= 6) | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 1.1* | 0.2 ± 0.1* |

| (0.5–6.3) | (0.0–4.8) | (0.0–0.5) |

Values are mean ±s.e.m. Values in parentheses represent the range of sampled values.

Significant change from baseline, P < 0.05.

In contrast, the firing rate of six baro-activated CVLM neurones was greatly reduced or silenced during exposure to hypoxia or intravenous injection of cyanide (Fig. 3A and D; Table 1). The basal firing rates were comparable to hypoxia-activated CVLM neurones (Table 1). However, at baseline most (5/6) hypoxia-inhibited CVLM neurones had peak neuronal activity during the expiratory phase of respiration with decreased activity during inspiration (Fig. 3C). Changes in respiratory-related activity during hypoxia could not be evaluated for these six CVLM neurones due to the dramatically reduced firing rate.

Figure 3. Examples of baro-activated CVLM neurones inhibited by hypoxia.

A, this CVLM neurone was activated by raising AP (snare), but inhalation of hypoxic air (60 s at bar) inhibited the firing of this neurone. B, an AP pulse-triggered histogram shows the pulse-modulated activity of this CVLM neurone. The CVLM unit was counted in 0.01 s bins. C, phrenic-triggered histogram shows a depression of inspiratory-related activity in this CVLM neurone during baseline. The activity of this CVLM unit was counted in 0.1 s bins. D, injection of CN inhibits the firing of this baro-activated CVLM neurone concomitant with increases in SNA and AP. HR, heart rate. bpm, beats · min−1.

Effects of inhibition or antagonism of glutamatergic receptors in the CVLM on the sympathetic responses to hypoxia

Microinjection of vehicle into the CVLM did not alter baseline AP or SNA (Table 2) or the sympathetic response to hypoxia or cyanide (0.81 ± 0.44 μV versus 1.00 ± 0.44 μV, P= 0.37 for hypoxia; 3.61 ± 1.05 μV versus 3.11 ± 0.89 μV, P= 0.34 for cyanide). Thus, the magnitude of sympathetic responses to hypoxia and cyanide is repeatable under these experimental conditions within this time frame (10–15 min).

Table 2.

Physiological responses to microinjections into the CVLM

| n | Baseline AP (mmHg) | Treatment AP (mmHg) | SNA (% of baseline) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 3 | 108 ± 12 | 109 ± 12 | 101 ± 6 |

| Bicuculline | 8 | 124 ± 4 | 94 ± 10* | 60 ± 10* |

| Gabazine | 8 | 123 ± 4 | 104 ± 6* | 52 ± 7* |

| Strychnine | 5 | 129 ± 8 | 124 ± 8 | 98 ± 5 |

| Muscimol | 11 | 111 ± 5 | 183 ± 4* | 639 ± 85* |

| Kynurenate | 5 | 112 ± 2 | 189 ± 4* | 670 ± 182* |

Values are mean ±s.e.m.n, number of animals. AP, arterial pressure; SNA, sympathetic nerve activity.

Significant change from baseline, P < 0.05.

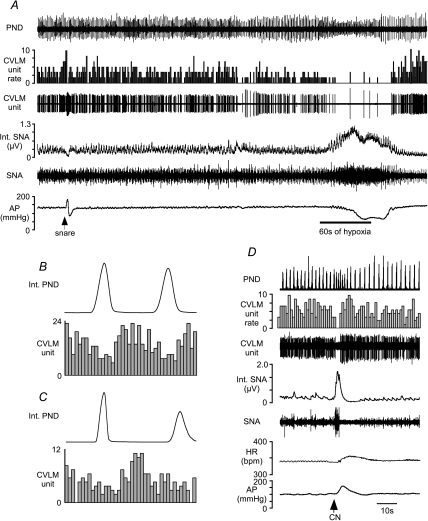

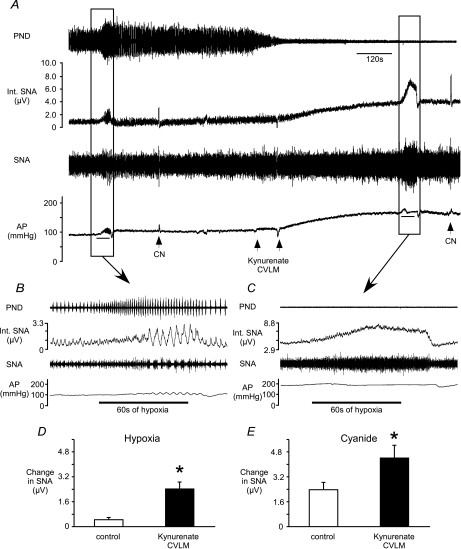

Bilateral microinjection of the glutamate antagonist kynurenate (n= 5) into the CVLM greatly increased SNA and AP (Fig. 4A; Table 2). These microinjections also silenced PND as previously reported (Koshiya et al. 1993). After microinjections of kynurenate, the hypoxia-induced increase in SNA was largely tonic, lacking the respiratory-related, phasic inhibition of SNA seen prior to the microinjections (Fig. 4B and C). However, the magnitude of the sympathetic response to hypoxia or cyanide was enhanced (Fig. 4D and E).

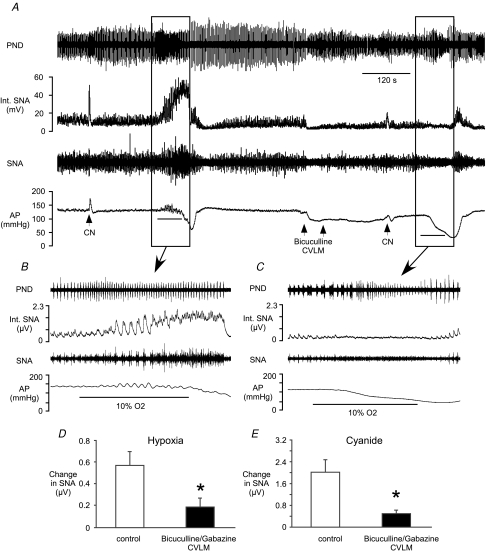

Figure 4. Effects of antagonism of glutamate receptors in the CVLM on the sympathetic responses to hypoxia and cyanide.

A, inhalation of hypoxic air or injection of CN increased SNA before and after bilateral microinjection of kynurenate into the CVLM. Kynurenate significantly increased SNA and AP (Table 2). Bars under traces of AP = 60 s exposure to hypoxia. B, at baseline, respiratory-related bursts in SNA are present in the sympathetic response to hypoxia. C, after kynurenate, hypoxia-induced oscillations in SNA are absent. The magnitude of the sympathetic response to hypoxia (D) or CN (E) was significantly larger after antagonism of glutamate receptors in the CVLM. *Significant difference from control values.

Comparable to the effects of microinjections of kynurenate, microinjections of the GABAA agonist muscimol to silence the activity of neurones in the CVLM region (n= 6) increased SNA and AP (Table 2) while silencing PND. The respiratory-related bursts in SNA that occur during hypoxia were also eliminated by microinjection of muscimol into the CVLM, and the mean increases in SNA during hypoxia (1.04 ± 0.22 μV versus 6.09 ± 0.66 μV, P < 0.05) and cyanide (3.53 ± 0.74 μV versus 8.50 ± 1.11 μV, P < 0.05) were similarly exaggerated after microinjection of muscimol into the CVLM.

To determine whether inhibition of CVLM activity enhanced the ability of glutamate to excite the RVLM, we microinjected glutamate into the RVLM before and after microinjection of muscimol into the CVLM (n= 5). The rise in SNA evoked by microinjection of glutamate into the RVLM was not altered by inhibition of CVLM neuronal activity (3.64 ± 0.66 μV versus 4.92 ± 1.50 μV, P= 0.11).

Effects of antagonism of GABAA receptors in the CVLM on the sympathetic responses to hypoxia

Microinjection of the GABAA antagonists gabazine or bicuculline into the CVLM produced comparable decreases in SNA and AP (Table 2). Because the physiological changes evoked by these antagonists were equivalent, the data were pooled for subsequent analyses. Microinjection of gabazine or bicuculline into the CVLM often altered the amplitude, frequency and duration of phrenic bursts, preventing the reliable examination of respiratory-related changes in SNA during antagonism of GABAA receptors in the CVLM (see Fig. 5C). Following microinjection of gabazine (n= 6) or bicuculline (n= 5) into the CVLM, exposure to hypoxia or injection of cyanide evoked dramatically reduced increases in SNA (Fig. 5). In addition, the cyanide-evoked increase in AP was significantly attenuated (23 ± 5 mmHg versus 9 ± 1 mmHg, P < 0.05).

Figure 5. Effects of antagonism of GABAA receptors in the CVLM on the sympathetic response to hypoxia and cyanide.

A, inhalation of hypoxic air or injection of CN increased SNA before and after bilateral microinjection of bicuculline into the CVLM. Microinjection of bicuculline into the CVLM decreases SNA and AP (Table 2). B, prior to antagonism of GABAA receptors in the CVLM, hypoxia significantly elevates SNA with respiratory-related bursts. C, after bicuculline, the sympathetic response to hypoxia is significantly reduced. The hypoxia-induced (D) or CN-induced (E) increases in SNA were greatly blunted by antagonism of GABAA receptors in the CVLM. *Significant difference from control values.

To ensure that microinjection of bicuculline or gabazine into the CVLM did not reduce the ability of glutamate to activate presympathetic RVLM neurones, we microinjected glutamate into the RVLM before and after microinjection of gabazine (n= 2) or bicuculline (n= 3) into the CVLM. The magnitude of the sympathetic response to microinjection of glutamate into the RVLM was not altered by antagonism of GABAA receptors in the CVLM (Fig. 6).

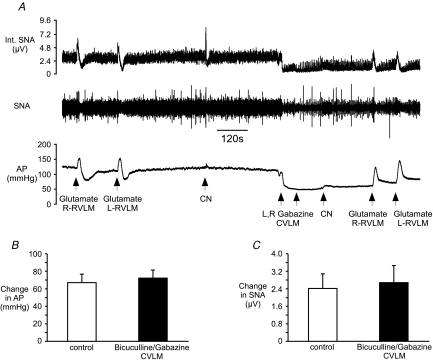

Figure 6. Effects of antagonism of GABAA receptors in the CVLM on the ability of glutamate to activate rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) and SNA.

A, raw tracings of SNA and AP during the experimental protocol. B, the change in AP evoked by microinjection of glutamate (1 nmol) into the RVLM is not altered after microinjection of bicuculline or gabazine into the CVLM. C, the change in SNA after microinjection of glutamate into the RVLM is not altered by microinjection of bicuculline or gabazine into the CVLM.

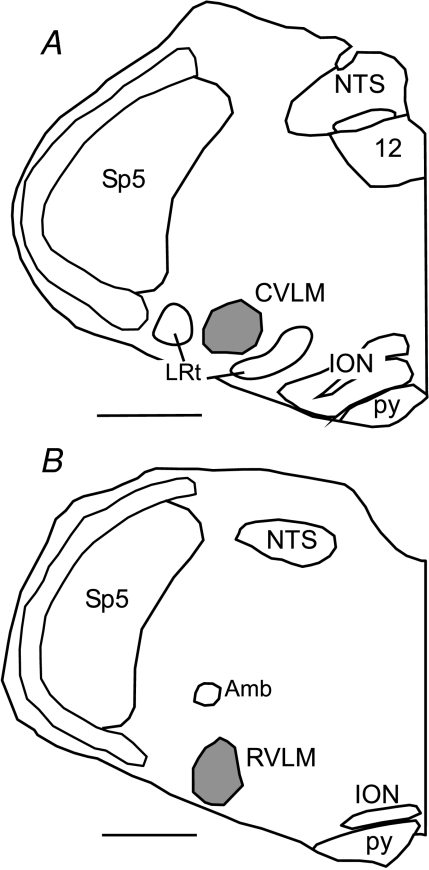

Histological examination of microinjections into the CVLM and RVLM verified sites previously described for cardiovascular-related neurones (Fig. 7; Schreihofer & Guyenet, 1997, 2002, 2003).

Figure 7. Representative RVLM and CVLM microinjection sites.

A, tracing of a coronal hemi-section through the caudal medulla from a rat that received a microinjection into the CVLM. B, tracing of a coronal hemi-section through the rostral medulla from a rat that received a microinjection into the RVLM. In each case the spread of the injected dye is outlined in grey. Scale = 1 mm. NTS, nucleus of the tractus solitarius. 12, hypoglossal nucleus, Amb, nucleus amblguus, RVLM, rostral ventrolateral medulla, ION, inferior olivary nucleur, Sp5, spinal trigeminal nucleus, py, pyramidal tract, LRt, lateral reticular nucleus.

Effects of antagonism of glycine receptors in the CVLM on the sympathetic responses to hypoxia

Bilateral microinjection of strychnine into the CVLM did not significantly alter baseline SNA or AP (Table 2). Furthermore, these microinjections did not significantly alter the magnitude of the sympathetic responses to hypoxia (0.41 ± 0.07 versus 0.41 ± 0.12 μV) or injection of cyanide (1.78 ± 0.42 versus 1.22 ± 0.60 μV). Histological examination of microinjections into the CVLM and RVLM verified sites previously described for cardiovascular-related neurones (Fig. 7; Schreihofer & Guyenet, 1997, 2002, 2003).

Discussion

Acute hypoxia activates peripheral chemoreceptors to stimulate SNA with oscillations linked to increased drive in the central respiratory cycle. Previous studies have suggested the CVLM is not necessary for the tonic excitation of SNA produced by acute hypoxia, but may play a role in the respiratory-related changes in SNA seen under this condition (see Fig. 4; Koshiya et al. 1993; Koshiya & Guyenet, 1996). A major finding of the present study is that baro-activated CVLM neurones show robust and differential responses to stimulation of the peripheral chemoreceptors by hypoxia or cyanide. The nature of the CVLM neuronal response was predicted by the basal pattern of respiratory-related activity, and these changes were consistent with and inversely related to the hypoxia-induced changes in SNA. In addition, the sympathetic response to hypoxia was enhanced by blocking excitation of the CVLM but reduced by blocking inhibition of the CVLM. These data suggest glutamate and GABA influence inhibitory CVLM neurones to contribute to both the magnitude and patterning of the sympathetic response to the activation of peripheral chemoreceptors.

Recordings of CVLM neurones

An assumption of the present study is that the recorded CVLM neurones are a sample of the population that inhibits presympathetic RVLM neurones and SNA. Pharmacological studies suggest that GABAergic neurones in the CVLM tonically inhibit the RVLM to reduce SNA (Willette et al. 1984; Blessing, 1988; Schreihofer et al. 2005), and evoke sympatho-inhibitory reflexes such as the arterial baroreflex (Gordon, 1987; Koshiya & Guyenet, 1996). In the present study we recorded in the region of the CVLM that contains GABAergic baro-activated neurones with axonal projections to the RVLM (Minson et al. 1997; Chan & Sawchenko, 1998; Schreihofer & Guyenet, 2002). Our criteria for selecting the neurones included robust activation by increased AP (Schreihofer & Guyenet, 2003; Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006) and a location ∼150–200 μm ventral to recorded central respiratory neurones (Gieroba et al. 1992; Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006). Furthermore, the activity of these recorded CVLM neurones, which was generally inversely related to SNA and presumed RVLM neuronal activity, showed predominant firing during systole (see Fig. 3; Schreihofer & Guyenet, 2003) and distinct patterns of activity related to the central respiratory cycle (see Figs 2 and 3; Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006). In previous studies from this laboratory (Schreihofer & Guyenet, 2003; Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006; Mobley et al. 2006), all juxtacellularly labelled CVLM neurones with these selection criteria expressed GAD67 mRNA, suggesting a GABAergic phenotype. Although we cannot prove that we are recording from the critical sympatho-inhibitory neurones, CVLM neurones with these properties are the most likely candidates to inhibit the RVLM to reduce SNA and AP.

The proportion of recorded CVLM neurones with peak activity during expiration versus those peaking during inspiration was not equivalent in the present study. However, our previous study evaluating the respiratory-related modulation of baro-activated CVLM neurones (Mandel & Schreihofer, 2006) found a comparable number of neurones with peak activity during expiration (n= 24) versus inspiration (n= 25). Because these studies involve a random sampling from a larger population of neurones, the true ratio of CVLM neurones with these particular patterns of respiratory-related activity and responses to hypoxia are not known. Thus, these data serve to document the existence of both types of neurones but not their proportion within the population or the ratio needed to evoke the observed sympathetic responses to hypoxia.

Activation of the CVLM by the peripheral chemoreflex

A subset (13/19) of recorded baro-activated CVLM neurones was excited by inhalation of hypoxic air or by i.v. injection of sodium cyanide. These data are in agreement with a previous report of hypoxia-induced excitation of baro-activated CVLM neurones antidromically activated from the RVLM in rabbits (Gieroba et al. 1992). In the context of that study it was seemingly paradoxical how the activation of inhibitory CVLM neurones could contribute to the resulting increase in SNA. However, with analyses in the context of the central respiratory cycle, sympathetic responses to hypoxia can readily be explained by the activation of certain inhibitory CVLM neurones. In the present study most CVLM neurones activated by hypoxia displayed a peak in activity during inspiration that was enhanced by hypoxia, coincident with a hypoxia-induced depression in SNA during inspiration. Furthermore, the hypoxia-enhanced, inspiratory-related activity in baro-activated CVLM neurones may also promote the hypoxia-induced depression of RVLM neuronal activity observed during the inspiratory phase (Koshiya et al. 1993) and contribute to the complete inhibition of some RVLM neurones during activation of the peripheral chemoreflex (McAllen, 1992; Koshiya et al. 1993; Koganezawa & Terui, 2007).

Although the injection of cyanide also evoked a small rise in AP that could contribute to the excitation of the baro-activated CVLM neurones, it does not fully explain their response to the stimulus. Cyanide produced a dramatic increase in activity of these CVLM neurones that was much larger than the response to raising AP alone (see Fig. 2). In addition, the cyanide-activated CVLM neurones were always excited by hypoxia, which sometimes produced a decrease or no significant change in AP (see Fig. 2). Indeed, during hypoxia these neurones sustained activity during decreases in AP that would have normally led to a significant reduction in firing or silencing of CVLM neuronal activity. These data suggest that chemoreceptor-related activation via predominantly inspiratory-related inputs is capable of sustaining the activity of CVLM neurones that would be silent in the absence of tonic inputs from arterial baroreceptors.

The neurotransmitter that produces the inspiratory-related peak in activity in some baro-activated CVLM neurones during hypoxia is not known, but several lines of evidence indicate that glutamate in the CVLM promotes inspiratory-related depression of RVLM neuronal activity and SNA under resting conditions. Some presympathetic RVLM neurones no longer show depressed activity during inspiration when CVLM activity is silenced by microinjection of the GABAA agonist muscimol (Koshiya & Guyenet, 1996), and this response is mimicked by blockade of glutamatergic receptors in the CVLM (Miyawaki et al. 1996). In contrast, other RVLM neurones display post-inspiratory peaks that are enhanced by blockade of glutamatergic receptors in the CVLM (Miyawaki et al. 1996). These data suggest that a subset of CVLM neurones are activated by glutamate to suppress RVLM activity and SNA during discrete portions of the central respiratory cycle, which could serve to produce inspiratory depressions observed in some RVLM neurones and limit the post-inspiratory-related peaks in other RVLM neurones.

Whether the abolition of respiratory-related fluctuations in SNA during hypoxia after blockade of glutamate receptors in the CVLM is due to the silencing of local central respiratory neurones themselves, as PND is eliminated, or by the silencing of baro-activated CVLM neurones cannot be determined by the present study. However, it is possible to eliminate PND by microinjections of kynurenate into the vicinity of the CVLM without disrupting hypoxia-induced, rhythmic fluctuations in SNA (Koshiya et al. 1993), suggesting that the two effects of the antagonism of glutamate receptors in the CVLM can be dissociated. Indeed, silencing of PND does not necessarily indicate that other central respiratory neurones that may influence CVLM neurones are inactivated. In the present study inhibition of the CVLM either by muscimol or kynurenate raised SNA and yielded enhanced sympathetic responses to cyanide and hypoxia. These data suggest that elimination of the buffering influence of the CVLM allows other inputs to the RVLM to raise SNA unchecked. The persistence of the sympathetic response to activation of the chemoreceptors after inhibition of the CVLM has been reported previously (Koshiya et al. 1993; Koshiya & Guyenet, 1996), but in those studies the magnitude of the sympathetic response was not enhanced. This difference may be related to the balance of the excitatory and inhibitory influences to the RVLM under resting conditions dictated by the state of the animal (see Fig. 8). In either case, excitation of the CVLM by glutamate appears to contribute to respiratory-related shaping of presympathetic RVLM neuronal activity and SNA, and this input is strengthened by activation of peripheral chemoreceptors.

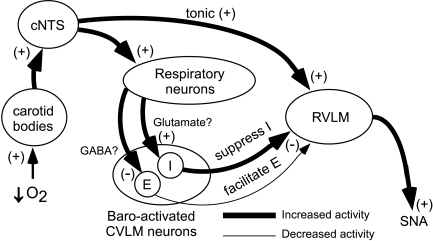

Figure 8. Proposed model for the impact of CVLM activity on RVLM activity during hypoxia.

Ventilation with hypoxic air decreases arterial  and stimulates the peripheral chemoreceptors to initiate the chemoreceptor reflex (for comprehensive review see Guyenet, 2000). Chemoreceptor afferents activate neurones in the caudal region of the nucleus of the tractus solitarius (cNTS). By means of a direct, respiratory-independent input to the RVLM, cNTS neurones activate the RVLM to increase SNA. The cNTS neurones also innervate central respiratory neurones and promote enhanced central respiratory drive (increase PND). Within the CVLM are populations of baro-activated neurones with principal respiratory-related activity during inspiration (I) or respiratory-related activity during expiration (E). The I baro-activated neurones are activated by hypoxia, which in turn suppresses I activity in the RVLM and SNA during hypoxia. The E baro-activated neurones are inhibited during hypoxia and facilitate the excitation of RVLM neurones and SNA during the expiratory phase of respiration.

and stimulates the peripheral chemoreceptors to initiate the chemoreceptor reflex (for comprehensive review see Guyenet, 2000). Chemoreceptor afferents activate neurones in the caudal region of the nucleus of the tractus solitarius (cNTS). By means of a direct, respiratory-independent input to the RVLM, cNTS neurones activate the RVLM to increase SNA. The cNTS neurones also innervate central respiratory neurones and promote enhanced central respiratory drive (increase PND). Within the CVLM are populations of baro-activated neurones with principal respiratory-related activity during inspiration (I) or respiratory-related activity during expiration (E). The I baro-activated neurones are activated by hypoxia, which in turn suppresses I activity in the RVLM and SNA during hypoxia. The E baro-activated neurones are inhibited during hypoxia and facilitate the excitation of RVLM neurones and SNA during the expiratory phase of respiration.

Inhibition of the CVLM by the peripheral chemoreflex

The activity of a separate subset of baro-activated CVLM neurones was reduced or silenced by hypoxia or i.v. injection of sodium cyanide. These hypoxia-inhibited CVLM neurones were primarily active during the expiratory phase of the central respiratory cycle under normoxic conditions. Inhibition of these CVLM neurones could promote the observed hypoxia-induced increase in RVLM activity and SNA observed during the expiratory phase of the central respiratory cycle (Koshiya et al. 1993; Dick et al. 2004). Furthermore, silencing of these CVLM neurones may contribute to the hypoxia-induced increased activity of RVLM neurones during all phases of the central respiratory cycle (McAllen, 1992; Koshiya et al. 1993; Koganezawa & Terui, 2007).

The hypoxia-induced reductions in CVLM neuronal activity occurred without correlation to the changes in AP, which were usually small at the onset of the stimulus and highly variable due to the concomitant rise in SNA offset by the direct vasodilatory effects of hypoxia (Daugherty et al. 1967; Marshall, 1994). Strikingly, baro-activated, hypoxia-inhibited CVLM neurones were also silenced by i.v. injection of sodium cyanide despite a substantial rise in AP. Indeed, the excitatory input to the baro-activated CVLM neurones with increased AP was overpowered by the inhibitory influence evoked by stimulation of peripheral chemoreceptors. These data suggest that although baroreceptors can provide a powerful drive for these neurones, other inputs can dominate to inhibit their activity.

The neurotransmitter responsible for inhibiting baro-activated, expiratory-related CVLM neurones during hypoxia is not known, but GABA is a likely candidate. Blockade of GABAA receptors in the CVLM reduces SNA and AP (Fig. 5; Sved et al. 1985), suggesting tonic GABAergic inputs to the CVLM normally facilitate RVLM neuronal activity and SNA. Blockade of GABAA receptors in the region of the CVLM greatly attenuated and sometimes eliminated the hypoxia-induced increase in SNA, suggesting that inhibition of the CVLM normally facilitates the response. This surprising finding was confirmed using two different GABAA antagonists, gabazine and bicuculline. One possible interpretation of this observation is that altered CVLM activity influences the ability of glutamate from other sources to excite RVLM neurones during stimulation of the peripheral chemoreceptors. To address this issue, we microinjected glutamate directly into the RVLM before and after microinjection of GABAA agonists or antagonists into the CVLM. Our results suggest that the putative enhanced CVLM neuronal activity with blockade of GABA receptors in the CVLM does not influence the ability of glutamate to drive RVLM activity. Thus, it appears that GABA provides a tonic influence upon CVLM neurones that inhibit the RVLM and SNA, and that this input is stimulated by hypoxia to facilitate the sympathetic response.

Summary

These data highlight previously unappreciated roles for the CVLM as a contributor to both the magnitude and the patterning of the sympathetic response to acute hypoxia. Both glutamate and GABA appear to tonically regulate the CVLM neurones that restrain the RVLM and SNA, and central respiratory neurones may either influence or supply these inputs to the CVLM. In addition, the sympathetic response to stimulation of peripheral chemoreceptors appears to be dampened by glutamatergic inputs to the CVLM and enhanced by GABAergic inhibition of CVLM during different phases of the central respiratory cycle. These data highlight the importance of examining the pattern of sympathetic responses in addition to gross changes in magnitude. Indeed, changes observed in relation to the central respiratory cycle in SNA are well-matched and inversely related to the activity of putative inhibitory neurones in the CVLM. Without such analysis, the significance of the diverse responses in the CVLM neurones would be difficult to place into a meaningful context. These data suggest that during activation of the peripheral chemoreflex, baro-activated GABAergic CVLM neurones receiving diverse respiratory-related inputs differentially affect the activity of RVLM neurones and shape the pattern of the SNA in relation to the central respiratory cycle.

In the present study both baroreceptor-related and respiratory-related inputs influenced the activity of the recorded CVLM neurones, and when opposing influences were present, either could predominate. Although we commonly refer to these CVLM neurones as cardiovascular-related due to their exquisite barosensitivity and presumed effects upon the SNA to cardiovascular targets, a re-evaluation of how these neurones are classified is warranted. Perhaps these CVLM neurones should be more aptly referred to as cardio-respiratory integrative neurones that not only tonically inhibit SNA, but also promote the shaping of the rhythmic properties of the SNA that maintains AP.

References

- Blessing WW. Depressor neurons in rabbit caudal medulla act via GABA receptors in rostral medulla. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1988;254:H686–H692. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.4.H686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton MD, Kazemi H. Neurotransmitters in central respiratory control. Respir Physiol. 2000;122:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RK, Sawchenko PE. Organization and transmitter specificity of medullary neurones activated by sustained hypertension: implications for understanding baroreceptor reflex circuitry. J Neurosci. 1998;18:371–387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00371.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Trzebski A. Respiratory-related discharge pattern of sympathetic nerve activity in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Physiol. 1990;426:355–368. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty RM, Jr, Scott JB, Dabney JM, Haddy FJ. Local effects of O2 and CO2 on limb, renal, and coronary vascular resistances. Am J Physiol. 1967;213:1102–1110. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1967.213.5.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick TE, Hsieh Y-H, Morrison S, Coles SK, Prabhakar N. Entrainment pattern between sympathetic and phrenic nerve activities in the Sprague-Dawley rat: hypoxia-evoked sympathetic activity during expiration. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R1121–R1128. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00485.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieroba ZJ, Li YW, Blessing WW. Characteristics of caudal ventrolateral medullary neurones antidromically activated from rostral ventrolateral medulla in the rabbit. Brain Res. 1992;582:196–207. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90133-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon FJ. Aortic baroreceptor reflexes are mediated by NMDA receptors in caudal ventrolateral medulla. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1987;252:R628–R633. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.252.3.R628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG. Neural structures that mediate sympathoexcitation during hypoxia. Respir Physiol. 2000;121:147–162. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, Koshiya N. Working model of the sympathetic chemoreflex in rats. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1995;17:167–179. doi: 10.3109/10641969509087063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeske I, Morrison SF, Cravo SL, Reis DJ. Identification of baroreceptor reflex interneurons in the caudal ventrolateral medulla. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1993;264:R169–R178. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.1.R169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koganezawa T, Terui N. Differential responsiveness of RVLM sympathetic premotor neurones to hypoxia in rabbits. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H408–H414. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00881.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiya N, Guyenet PG. Role of the pons in the carotid sympathetic chemoreflex. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1994;267:R508–R518. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.2.R508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiya N, Guyenet PG. NTS neurones with carotid chemoreceptor inputs arborize in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1996;270:R1273–R1278. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.6.R1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiya N, Huangfu D, Guyenet PG. Ventrolateral medulla and sympathetic chemoreflex in the rat. Brain Res. 1993;609:174–184. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90871-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllen RM. Actions of carotid chemoreceptors on subretrofacial bulbospinal neurones in the cat. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1992;40:181–188. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(92)90199-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel DA, Schreihofer AM. Central respiratory modulation of barosensitive neurones in rat caudal ventrolateral medulla. J Physiol. 2006;572:881–896. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. Peripheral chemoreceptors and cardiovascular regulation. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:543–594. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mifflin SW. Absence of respiration modulation of carotid sinus nerve inputs to nucleus tractus solitarius neurones receiving arterial chemoreceptor inputs. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1993;42:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90364-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minson JB, Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Chalmers JP, Pilowsky PM, Arnolda LF. c-fos identifies GABA-synthesizing barosensitive neurones in caudal ventrolateral medulla. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3015–3021. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709290-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki T, Minson J, Arnolda L, Chalmers J, Llewellyn-Smith I, Pilowsky P. Role of excitatory amino acid receptors in cardiorespiratory coupling in ventrolateral medulla. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1996;271:R1221–R1230. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.5.R1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobley SC, Mandel DA, Schreihofer AM. Systemic cholecystokinin differentially affects baro-activated GABAergic neurones in rat caudal ventrolateral medulla. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2760–2768. doi: 10.1152/jn.00526.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreihofer AM, Guyenet PG. Identification of C1 presympathetic neurons in rat rostral ventrolateral medulla by juxtacellular labeling in vivo. J Comp Neurol. 1997;387:524–536. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971103)387:4<524::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreihofer AM, Guyenet PG. The baroreflex and beyond: Control of sympathetic vasomotor tone by GABAergic neurons in the ventrolateral medulla. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:514–521. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreihofer AM, Guyenet PG. Baro-activated neurones with pulse-modulated activity in the rat caudal ventrolateral medulla express GAD67 mRNA. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1265–1277. doi: 10.1152/jn.00737.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreihofer AM, Ito S, Sved AF. Brain stem control of arterial pressure in chronic arterial baroreceptor-denervated rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:1746–1755. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00307.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sved AF, Blessing WW, Reis DJ. Caudal ventrolateral medulla can alter vasopressin and arterial pressure. Brain Res Bull. 1985;14:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(85)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willette RN, Punnen S, Krieger AJ, Sapru HN. Interdependence of rostral and caudal ventrolateral medullary areas in the control of blood pressure. Brain Res. 1984;321:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]