Abstract

Chronic nerve compression injuries (CNC) are progressive demyelinating disorders characterized by a gradual decline of the nerve conduction velocity (NCV) in the affected nerve region. CNC injury induces a robust Schwann cell response with axonal sprouting, but without morphologic evidence of axonal injury. We hypothesize that early CNC injury occurs without damage to neuromuscular junction of motor axons. A well-established animal model was used to assess for damage to motor axons. As sprouting is considered a hallmark of regeneration during and after axonal degeneration and sprouting was confirmed visually at 2 weeks in CNC animals, we assessed for axonal degeneration in motor nerves after CNC by evaluating the integrity of the neuromuscular junction. NCV exhibited a gradual progressive decline consistent with the human condition. Compound motor action potential amplitudes decreased slightly immediately and plateaued, indicating that there was not sustained and increasing axonal loss. Sprouting was confirmed using immunofluorescence and by an increase in number of unmyelinated axons and Remak bundles. Blind analysis of the neuromuscular junction showed no difference between control and CNC images, indicating that there was no evidence for end-unit axonal loss in the soleus muscle. Because the progressive decline in NCV was not paired with a similar progressive decline in amplitude, it is likely that axonal loss is not responsible for slowing of action potentials. Blind analysis of the neuromuscular junction provides further evidence that the axonal sprouting seen early after CNC injury is not a consequence of axonal degeneration in the motor nerves.

Keywords: chronic nerve injury, demyelination, motor unit, axonal sprouts

After acute nerve injuries such as an axotomy or crush, the proximal segment of the nerve will develop a growth cone and attempt to reestablish a connection with the distal target tissue such as a muscle fiber or sensory structure.1,2 Growth cones, composed of sprouts, represent an attempt by the nerve to repair itself. The sprouting process is influenced by pro-regenerative growth factors secreted by surrounding neural structures including nerve growth factor, glial-derived neurotrophic factor, and other trophic support, that help direct regeneration of the nerve.3 As many factors influence the outcome of these sprouts, the regenerative process may be futile in rapidly progressive neurological processes such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA).4

Unlike ALS and SMA, chronic nerve compression (CNC) is a progressive demyelinating disorder characterized by a gradual decline of the nerve conduction velocity (NCV) in the affected nerve region. Recent work has shown that there is a dramatic Schwann cell response including concurrent proliferation and apoptosis prior to significant NCV change.5 Furthermore, previous research has shown an alteration of Schwann cell myelination and gene function. This creates a local downregulation of mRNA for MAG, a protein known for inhibiting myelination, and a pro-regenerative environment, resulting in nerve sprouting, confirmed by electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry.6–9 All of these experiments confirm sprouting in this model for CNC injury. CNC injury-induced demyelination involves the smaller diameter fibers first (as early as 2 weeks), with the larger diameter fibers showing involvement after 4 weeks of sustained injury when prominent nerve sprouts are seen at the site of compression.11 Axonal degeneration, as determined by Wallerian degeneration, is not seen until later time points, indicating that sprouting may be occurring without axonal degeneration.

To test our hypothesis that nerve sprouting in CNC is independent of regeneration caused by axonal degeneration, we rigorously examined for evidence for axonal degeneration in motor nerves early in the course of CNC. Neurophysiologic techniques included measuring NCV, compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes and needle EMG.12–14 Nerve sprouting was visualized using electron microscopy and immunofluorescence. We directly visualized the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) to evaluate both the presynaptic (terminal motor neuron fibers) and the postsynaptic (acetylcholine receptors, AChR) elements.15,16

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Model

All animal research was performed with permission from the UC Irvine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). As previously described,5,7 a CNC model was created using adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (weight 200–300 g). Animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). A dorsal gluteal-splitting approach was used to expose and mobilize both sciatic nerves of each animal and a sterile 1 cm silastic tube (internal diameter of 1.3 mm, outer diameter of 2.0 mm; Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL) was placed around the right sciatic nerve atraumatically to induce CNC injury. The tube was free to slide longitudinally along the nerve. The contralateral sciatic nerve was exposed and returned to the host bed to serve as a control specimen. Animals were euthanized by anesthetic overdose. To create positive controls, a 2-week acute transection study was performed on sciatic nerves. The posterior tibial branch of the sciatic nerve was transected at its proximal stump and sutured to the triceps surae muscle to prevent reinnervation. Four to six animals were used per experimental group, as approved by IACUC. These procedures were approved by our institutional review committee and conformed to national standards.

At the termination of the experiments, sciatic nerves and soleus muscles were rapidly excised, cleaned of connective tissue, processed depending on the experiment, and stored at −80°C until subsequent analyses. We chose to study soleus, a predominantly slow-twitch muscle in rats, because of its early and severe involvement in denervation.17

Confirmation of Sprouting

To confirm the sprouting seen as previously reported,8 we harvested both compressed and normal sciatic nerves from 2-week CNC animals.

Longitudinal Section Immunofluorescence

Sciatic nerves were rinsed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 1 h, followed by 10% sucrose overnight at 4°C, then longitudinally sectioned at 20 µm and placed on slides. The slides were then frozen overnight at −80°C, incubated in 10% Triton-X in PBS for 1 h for permeabilization, and then incubated in 4% PFA for 20 min. Sections were blocked in blocking buffer (0.25% Triton-X, 4% normal goat serum in PBS), stained for neurofilament 160 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) overnight at 4°C, and imaged on an Olympus IX71 microscope with a Hamamatsu Camera and motorized stage by Prior. Image analysis and 3D image composition was done using Slidebook software by 3I.

Electron Microscopy of Whole Nerve Maps

Nerve specimens were fixed in 4% Gluteraldehyde overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation in 100 mM sodium cacodylate buffer overnight at 4°C. Postfixation was performed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 100 mM sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 h, and specimens were dehydrated in increasing serial dilutions of ethanol (70, 80, 90, 100 × 2) for 10 min each. Nerve segments were then incubated in propylene oxide for 1 h, incubated in propylene oxide/Spurr’s resin (1:1 mix) for 1 h, then embedded in Spurr’s resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) overnight. Sections were made at 70-nm increments and placed on formvar coated 2 × 1-mm slotted copper grids and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Entire nerve maps were made by taking multiple photos of each nerve (three normal and three compressed) with a Philips CM 10 electron microscope, and negatives were scanned for distinct histologic features to confirm that no region of the nerve cross-section was excluded. The total number of myelinated axons, unmyelinated axons, Remak bundles, macrophages, and Schwann cell nuclei were counted in Adobe Photoshop 8.0. Mean axonal diameter was determined by measuring 1000 randomly selected myelinated axons. Six hundred randomly selected unmyelinated axons were also analyzed for axonal diameter.

Electrophysiology

Nerve Conduction Studies

Animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (5 mg/mL) injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight. The distal hindlimbs were shaved, and animals were taped prone to a Styrofoam board. Recording electrodes, using subdermal EEG electrodes (Ambu A/S, Ballerup, Denmark) were placed under the skin overlying the tibialis anterior muscle, an easily accessible muscle innervated by the peroneal branch of the sciatic nerve. Reference electrode for the recording electrode (indifferent electrode) was placed in the ipsilateral foot, about 1.0–1.5 cm distal to the recording electrode. Sensory needle electrodes (7 mm) insulated with Teflon (Alpine Biomed, Fountain Valley, CA) were used for stimulation; a cathode was placed at the popliteal fossa for distal stimulation, and at the sciatic notch for stimulation, directly proximal to the site of compression; an anode was placed in the ipsilateral paraspinal muscles. A ground electrode was placed in the tail, if needed. Serial motor nerve conductions were performed at 2, 4, and 8 weeks as described5 and measurements of distal motor latency, conduction velocity and CMAP amplitudes were made both proximal and distal to the site of compression to determine decline across the site of compression. Animals exhibiting conduction block were excluded from the experimental group as conduction block is indicative of unintentional pinching of the nerve. Care was taken to keep the stimulation intensity to less than 3 mA for all neurophysiology studies.

Needle EMG

Needle EMG examinations were performed at 2 weeks using monopolar needle electrodes (Alpine Biomed, Fountain Valley, CA). Tibialis anterior and medial gastrocnemius muscles were examined for fibrillation potentials.

Morphologic Studies

Skeletal Muscle Morphology

Soleus muscles were harvested at 2, 4, and 8 weeks following CNC on both sides. Control muscles from acutely denervated muscle, harvested 2 weeks following sciatic nerve transection, were used.

Approximately 5–7.5 mm of the proximal side of soleus muscle was sectioned off, mounted in OCT, and flash-frozen by dipping in isopentane brought close to freezing in liquid nitrogen. Cross-sections were taken at 20 µm, placed on slides, and air dried. Sections were then stained in hematoxylin for 5 min, rinsed three times in deionized distilled water, and stained in eosin-yellow for 1 min. Sections were then dehydrated by dipping them in 30% ethanol, 60% ethanol, and finally 90% ethanol. Slides were covered with permount and cover slipped. Muscle sections were evaluated for morphological changes of skeletal muscle denervation, using established criteria.18 These included evidence for sharply angulated atrophic fibers, pyknotic nuclear clumps, small or large group atrophy, and hyaline structures, suggestive of target fibers.

Immunofluorescence Study

The center portion of the soleus muscle was lightly compressed between two slides and flash frozen on dry ice. Longitudinal sections were taken at 20 µm, placed on slides, and air dried followed by fixation in ice-cold methanol for 1 min. Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation in blocking buffer (4% Bovine Serum Albumin, 1% Triton in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature. Acetylcholine receptors were stained using Alexa Fluor 555 conjugated α-bungarotoxin in blocking buffer for 20 min at room temperature (1:4000, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Slides were then incubated at 4°C overnight in blocking buffer with mouse monoclonal antisynaptophysin primary antibody (1:400, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and rabbit antineurofilament 160 kDa polyclonal antibody (1:400, Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Blocking buffer with Alexa Fluor 488 goat antimouse IgG (1:1000 Molecular Probes) and Alexa Fluor 488 goat antirabbit IgG (1:1000, Molecular Probes) was applied to the slides for 2 h at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted with fluoromount-G and sections were imaged at 40× using a Zeiss fluorescent microscope. A blinded assessment of the integrity of the neuromuscular junction was performed.

Statistical Analyses

All data are reported as means ± standard error (SE). A two-tailed, heteroscedastic Student’s t-test was used to determine if the results from the blind assessment of neuromuscular junction integrity differed from 100%. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Nerve Sprouting

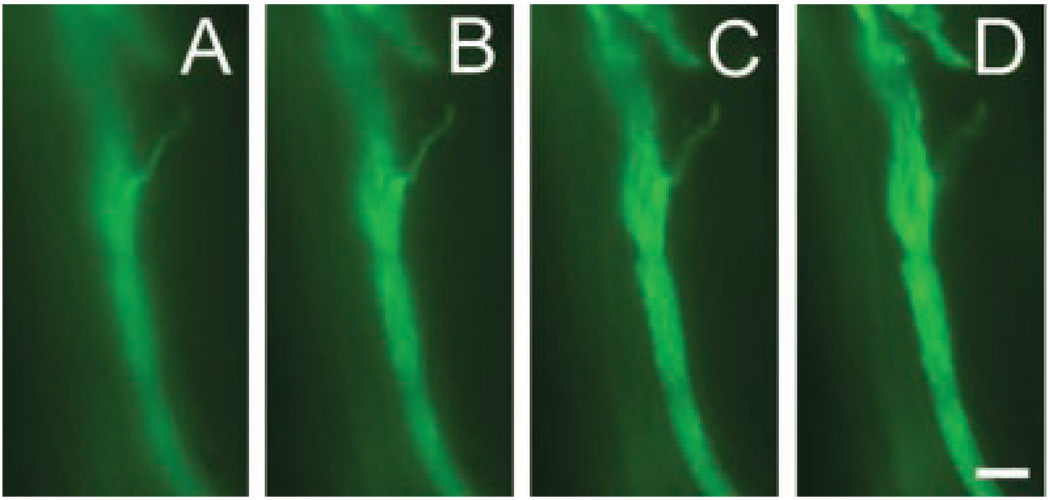

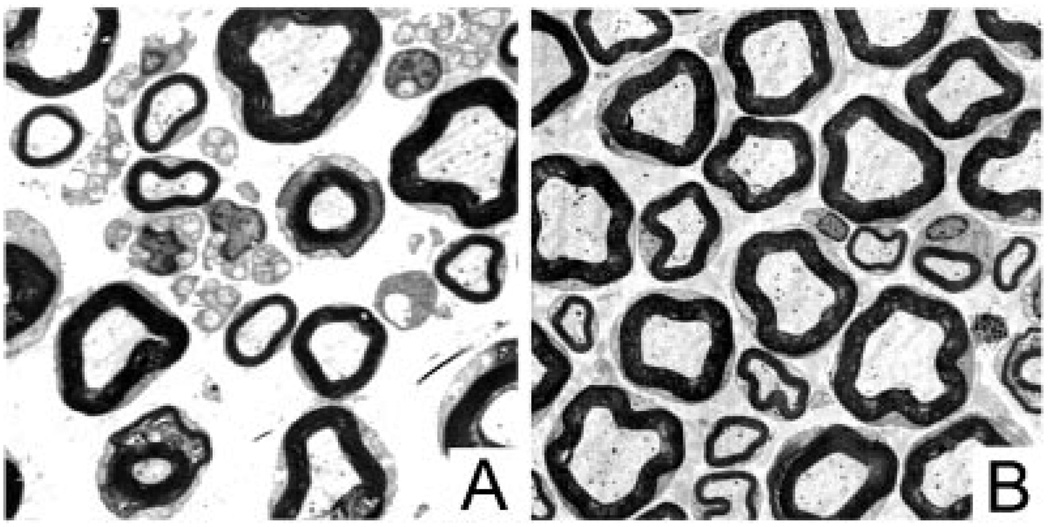

Immunofluorescence of 2-week longitudinal sections shows evident sprouting from the nodes of CNC sciatic nerves (Fig. 1). Electron micrographs of nerve cross-sections confirmed sprouting by showing an increase in number of Remak bundles and unmyelinated axons in compressed nerves when compared to normal without granular disintegration of the axoplasm (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Sprouting in longitudinal sections of 2 week CNC. Male rats (N = 4) were subjected to CNC for 2 weeks. Harvested sciatic nerves were sectioned longitudinally and stained for Neurofilament 160 (green). Images were taken at 3-µm increments to show three-dimentional sprouting from the node. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Figure 2.

Electron micrographs of sections of whole nerve maps of 2 week CNC nerves. Compressed nerves (A) show an increase in number of Remak bundles and unmyelinated axons when compared to normal nerves (B).

Neurophysiology Data

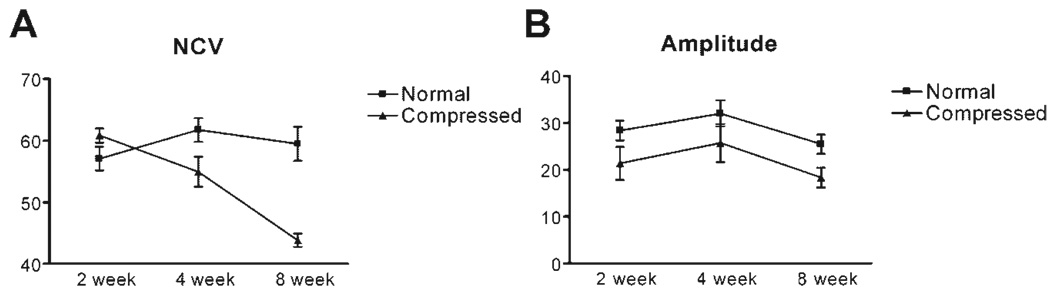

The NCV of the normal sciatic nerve (Fig. 3) did not exhibit a statistically significant change (58 ± 1.9 m/s at 2 weeks and 59.03 ± 1.6 m/s at 12 weeks), whereas NCV in the sciatic nerve on the compressed side showed a considerably declining trend 8 weeks following initiation of CNC injury (59.4 ± 1.9 m/s and 38.12 ± 1.1 m/s at 2 and 12 weeks, respectively). The CMAP, recorded from the tibialis anterior muscles, were similar on both sides with values of 28.37 ± 2.1 mV and 32.58 ± 4.2 mV at 2 and 12 weeks, respectively, on the uncompressed and 21.39 ± 3.5 and 15.54 ± 2.1 mV at 2 and 12 weeks, respectively, on the compressed side. These recordings were not statistically different. There was no evidence of conduction block or temporal dispersion in the animals included in the study. Needle EMG examination using monopolar electrodes in the tibialis anterior and medial gastrocnemius muscles bilaterally showed no fibrillation potentials (data not shown). In striking contrast, CMAP amplitudes could not be obtained from our positive controls, animals having undergone acute sciatic nerve transection.

Figure 3.

Neurophysiology in CNC. Male rats (N = 6) underwent serial neurophysiologic and MUNE examination 2, 4, and 8 weeks following CNC. Both compressed and uncompressed sides were tested. (A) Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) started declining at 2 weeks and declined by approximately 20 m/s on the compressed side compared to the uncompressed side. (B) Compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude showed a difference between the compressed and uncompressed sides at 2 weeks but never changed further. The difference between the two sides did not reach statistical significance at any of the time points.

Morphologic Data

Histologic examination of soleus muscles, in animals undergoing sciatic nerve transection (positive control), showed marked fiber size variation, with many small angular fibers and large areas of grouped atrophy, 2 weeks following sciatic nerve transection. The soleus muscles from CNC animals did not show any of these abnormalities at any of the studied time points (data not shown). These data provide further evidence that denervation atrophy does not occur in CNC muscles.

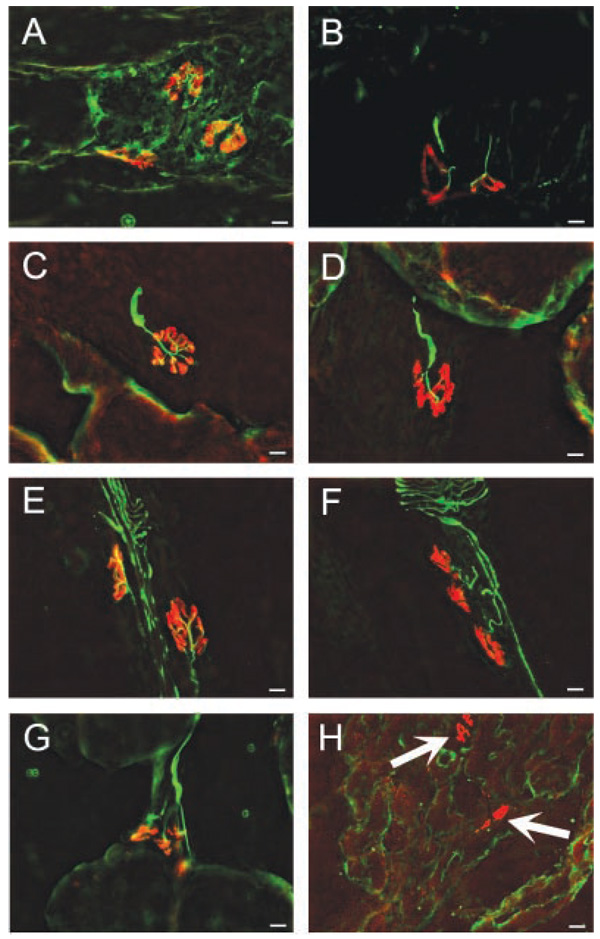

After axonal disintegration of motor nerves, there is a readily detectable loss of integrity of the presynaptic elements, resulting from a decline in structural proteins such as neurofilament protein and synaptic vesicle markers such synaptophysin. In contrast, the postsynaptic apparatus is relatively stable and readily identified by its high density of AChR many weeks after denervation. The density of extrajunctional AChR, however, increases dramatically during this same period.19–21 If axonal degeneration was prominent early after axonal degeneration, the NMJ in muscles from these animals would have been expected to show morphologic changes, including degeneration in the presynaptic apparatus and increase in density of postsynaptic receptors and presence of extrajunctional receptors. Rigorous blinded evaluation of the NMJ at each of the time points, however, failed to demonstrate any morphological distinction between the compressed and uncompressed sides (Fig. 4A–F) in CNC animals (p = 0.23). Presynaptic motor terminals were intact on both compressed and uncompressed sides and no extrajunctional receptors were seen. This was in contrast to the effects of sciatic nerve transection where, 2 weeks following surgery, neurofilament/synaptophysin labeling was not present in any of the muscle sections, and many areas of ectopic (extrajunctional) staining for AChRs were seen (Fig. 4H, arrows).

Figure 4.

The integrity of the neuromuscular junction is visually inspected using immunohistochemical analysis. Neurofilament and synaptophysin are stained green to localize presynaptic elements. Postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors are stained red. Neuromuscular junctions remain intact and normal for 2 week compressed animals on both the control side (A) and the compressed side (B). Four week compressed animals are normal on both the control side (C) and the compressed side (D). Eight week animals also have normal neuromuscular junctions on both the control side (E) and the compressed side (F). Positive control transected animals have normal neuromuscular junctions on the control side (G), however, the transected side shows extrajunctional acetylcholine receptors (arrow) and no positive neurofilament or synaptophysin staining (H).

DISCUSSION

Chronic nerve compression injuries, such as carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), are common human disorders that result in significant morbidity and worked-related disability. Focal and gradual demyelination of the median nerve occurs early in CTS and, if untreated, axonal loss may occur with irreversible loss of sensation along with sensory potentials, muscle atrophy, and degeneration of the thenar muscles. There has recently been considerable progress in understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for demyelination and axonal loss with compressive neuropathies.5–11,22 This study confirms a gradual decline in motor nerve conduction velocities in the animal model of CNC without a statistically significant change in CMAP. We found no alterations in the neuromuscular junctions that would support axonal loss.

The neurophysiologic findings in this study confirm that the early changes in this animal model are those of demyelination, and not axonal loss, at least not in the motor nerves. Our previous neurophysiologic and morphologic data provides evidence that axonal degeneration does not occur in the early stages of this model. The findings of normal appearing NMJ at all time points after CNC are highly significant in light of data from muscles of animals undergoing sciatic nerve transection. These muscles very early (at 2 weeks) show clear axonal loss as manifest by an almost complete disintegration of the presynaptic components of the NMJ and junctional remodeling with increased numbers and ectopic and extrajunctional positioning of the AChR in anticipation of reinnervation. Blinded evaluation of the muscles for NMJ could not differentiate between the compressed versus the uncompressed side at any of the time points. This, combined with all the data presented to date, strongly suggests that axonal loss is not occurring at the early stages of CNC, and thus is not responsible for nerve sprouting that has been so prominently noted in this model.

It is conceivable that our experimental methods failed to detect small degree of axonal damage in motor nerves that may have occurred. Sampling errors may have also failed to detect small areas of denervation atrophy. There clearly is not a progressive decline in CMAP amplitudes, and the maximal decline in CMAP amplitudes seems to occur within the first 2 weeks, after which no further decline occurs. This is in sharp contrast to the NCV, which continues to decline at each time point. If the 2-week decline in CMAP amplitude was related to axonal loss, it should have progressively worsened secondary to continued axonal loss. Yet, this was not the case, and rather, these values plateaued. Although a murine model for CNC does not currently exist, it would be worthwhile to explore how the CNC injury affects the WldS trangenic mouse, which exhibits delayed Wallerian Degeneration.24 If nerve sprouting is secondary to axonal loss, then CNC-induced sprouting in the WldS trangenic mouse would be expected to be substantially delayed as axonal integrity would be preserved. As we did not examine sensory functions, it is possible that nerve sprouting seen in this model may entirely be related to sensory, and not motor, axonal degeneration. This possibility is being addressed with our current set of experiments.

Recently, we have reported an increase in glial derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), which may be indicative of a phenotypic shift toward small-diameter nociceptive fibers.11 In this study, we discovered that CNC injury preferentially affects small-diameter neurons by colocalizing fluoro ruby uptake with neuronal subpopulation markers. This potential increase in small-diameter nociceptive fibers may account for the pain associated with chronic nerve injuries.

The finding that axonal degeneration is not required for the generation of nerve sprouts in CNC implies that there must be other physiologic mechanisms that underlie their production. Altered Schwann cell function may be responsible for the ensuing pathology. Schwann cells do respond robustly early after CNC injury with concurrent proliferation and apoptosis.5 It is likely that not all of these new Schwann cells are myelinating as the number of axons has not changed, and there are distinctly different patterns of myelination and remyelination after CNC.10,25 As such, these Schwann cells are likely at an earlier developmental phenotype as both in vivo and in vitro models have shown that these Schwann cells will increase production of pro-angiogenic molecules and decrease production of promyelogenic molecules.6,9 Recently, we have reported that there exists a local downregulation of MAG in regions of nerve sprouting with intraneural injections of MAG abrogating this response.8 Axonal sprouting and nerve growth have been shown to be inhibited by myelin associated proteins such as MAG.26–29 A decrease or a local deficiency of MAG would play an integral role in production of these sprouts. Moreover, compressive neuropathies are often associated with pain in the early stages of the neuropathy; neurologic dysfunction, such as sensory loss and motor weakness, occurs later. The mechanisms underlying pain generation are not well defined. Release of nociceptive chemical factors may underlie this phenomenon and such chemicals may effect morphologic, chemical, or ionic changes that may mediate the pain response. As the temporal course of nerve sprouting closely parallels the temporal course of c-fos upregulation in an animal CNC model,30 it is possible that this nerve sprouting may play an important role in mediating the pain response.

Although the mechanisms underlying generation of these nerve sprouts after CNC currently remain unanswered, the data from this study supports the conclusion that axonal sprouting after chronic nerve compression in this animal model is not caused by axonal degeneration in motor nerves.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Jeremy Shefner for introducing us to the MUNE techniques and subsequent critique of the MUNE data. The study was supported by PHS grants 5K08NS002221 (RG), 5R01NS049203 (RG) and 5R01NS033213 (MAS).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kapfhammer JP. Axon sprouting in the spinal cord: growth promoting and growth inhibitory mechanisms. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1997;196:417–426. doi: 10.1007/s004290050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg S, Frank B, Krayanek S. Axon end-bulb swellings and rapid retrograde degeneration after retinal lesions in young animals. Exp Neurol. 1983;79:753–762. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(83)90039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batchelor PE, Porritt MJ, Martinello P, et al. Macrophages and microglia produce local trophic gradients that stimulate axonal sprouting toward but not beyond the wound edge. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;21:436–453. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas CK, Zijdewind I. Fatigue of muscles weakened by death of motoneurons. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:21–41. doi: 10.1002/mus.20400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta R, Steward O. Chronic nerve compression induces concurrent apoptosis and proliferation of Schwann cells. J. Comp Neurol. 2003;461:174–186. doi: 10.1002/cne.10692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta R, Gray M, Chao T, et al. Schwann cells upregulate vascular endothelial growth factor secondary to chronic nerve compression injury. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:452–460. doi: 10.1002/mus.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta R, Lin YM, Bui P, et al. Macrophage recruitment follows the pattern of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in a model for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Neurotrauma. 2003;20:671–680. doi: 10.1089/089771503322144581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta R, Rummler LS, Palispis W, et al. Local downregulation of myelin-associated glycoprotein permits axonal sprouting with chronic nerve compression injury. Exp Neurol. 2006;200:418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.02.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta R, Truong L, Bear D, et al. Shear stress alters the expression of myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) and myelin basic protein (MBP) in Schwann cells. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:1232–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta R, Rowshan K, Chao T, et al. Chronic nerve compression induces local demyelination and remyelination in a rat model of carpal tunnel syndrome. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao T, Pham K, Steward O, et al. Chronic nerve compression injury induces a phenotypic switch of neurons within the dorsal root ganglia. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:180–193. doi: 10.1002/cne.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shefner JM, Cudkowicz ME, Brown RH., Jr Comparison of incremental with multipoint MUNE methods in transgenic ALS mice. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:39–42. doi: 10.1002/mus.10000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shefner JM, Gooch CL. Motor unit number estimation in neurologic disease. Adv Neurol. 2002;88:33–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shefner JM, Jillapalli D, Bradshaw DY. Reducing intersubject variability in motor unit number estimation. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:1457–1460. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199910)22:10<1457::aid-mus18>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen QT, Son YJ, Sanes JR, et al. Nerve terminals form but fail to mature when postsynaptic differentiation is blocked: in vivo analysis using mammalian nerve-muscle chimeras. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6077–6086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06077.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. Induction, assembly, maturation and maintenance of a postsynaptic apparatus. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:791–805. doi: 10.1038/35097557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huey KA, Haddad F, Qin AX, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the type I myosin heavy chain gene in denervated rat soleus. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C738–C748. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00389.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brooke MH, Kaiser KK. Trophic functions of the neuron. II. Denervation and regulation of muscle. The use and abuse of muscle histochemistry. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;228:121–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb20506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burden SJ, Sargent PB, McMahan UJ. Acetylcholine receptors in regenerating muscle accumulate at original synaptic sites in the absence of the nerve. J Cell Biol. 1979;82:412–425. doi: 10.1083/jcb.82.2.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pestronk A, Drachman DB. Motor nerve terminal outgrowth and acetylcholine receptors: inhibition of terminal outgrowth by alpha-bungarotoxin and anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody. J Neurosci. 1985;5:751–758. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-03-00751.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pestronk A, Drachman DB, Stanley EF, et al. Cholinergic transmission regulates extrajunctional acetylcholine receptors. Exp Neurol. 1980;70:690–696. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(80)90193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta R, Channual JC. Spatiotemporal pattern of macrophage recruitment after chronic nerve compression injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:216–226. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta R, Rummler L, Steward O. Understanding the biology of compressive neuropathies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;436:251–260. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000164354.61677.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mack TG, Reiner M, Beirowski B, et al. Wallerian degeneration of injured axons and synapses is delayed by a Ube4b/Nmnat chimeric gene. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1199–1206. doi: 10.1038/nn770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger BL, Gupta R. Demyelination secondary to chronic nerve compression injury alters Schmidt-Lanterman incisures. J Anat. 2006;209:111–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domeniconi M, Cao Z, Spencer T, et al. Myelin-associated glycoprotein interacts with the Nogo66 receptor to inhibit neurite outgrowth. Neuron. 2002;35:283–290. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu BP, Fournier A, GrandPre T, et al. Myelin-associated glycoprotein as a functional ligand for the Nogo66 receptor. Science. 2002;297:1190–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.1073031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen YJ, DeBellard ME, Salzer JL, et al. Myelin-associated glycoprotein in myelin and expressed by Schwann cells inhibits axonal regeneration and branching. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1998;12:79–91. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang S, Shen YJ, DeBellard ME, et al. Myelin-associated glycoprotein interacts with neurons via a sialic acid binding site at ARG118 and a distinct neurite inhibition site. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1355–1366. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rummler L, Gupta R. Mechanisms of pain in an in vivo model for chronic nerve compression injury. vol. 383. Atlanta, GA: Society for Neuroscience; 2006. [Google Scholar]