Abstract

Timothy syndrome (TS) is a multiorgan dysfunction caused by a Gly to Arg substitution at position 406 (G406R) of the human CaV1.2 (L-type) channel. The TS phenotype includes severe arrhythmias that are thought to be triggered by impaired open-state voltage-dependent inactivation (OSvdI). The effect of the TS mutation on other L-channel gating mechanisms has yet to be investigated. We compared kinetic properties of exogenously expressed (HEK293 cells) rabbit cardiac L-channels with (G436R; corresponding to position 406 in human clone) and without (wild-type) the TS mutation. Our results surprisingly show that the TS mutation did not affect close-state voltage-dependent inactivation, which suggests different gating mechanisms underlie these two types of voltage-dependent inactivation. The TS mutation also significantly slowed activation at voltages less than 10 mV, and significantly slowed deactivation across all test voltages. Deactivation was slowed in the double mutant G436R/S439A, which suggests that phosphorylation of S439 was not involved. The L-channel agonist Bay K8644 increased the magnitude of both step and tail currents, but surprisingly failed to slow deactivation of TS channels. Our mathematical model showed that slowed deactivation plus impaired OSvdI combine to synergistically increase cardiac action potential duration that is a likely cause of arrhythmias in TS patients. Roscovitine, a tri-substituted purine that enhances L-channel OSvdI, restored TS-impaired OSvdI. Thus, inactivation-enhancing drugs are likely to improve cardiac arrhythmias and other pathologies afflicting TS patients.

Timothy syndrome (TS) is a multiorgan disorder caused by single mutation G406R (TS mutation) of an alternatively spliced human CaV1.2 (L-type) calcium channel containing exon 8a (Splawski et al. 2004; Splawski et al. 2005). The TS mutation can lead to lethal arrhythmias thought to be caused by impaired open-state voltage-dependent inactivation (OSvdI) (Splawski et al. 2004, 2005; Raybaud et al. 2006; Barrett & Tsien, 2008). But proarrhythmic wild-type (WT) L-channel gating alterations are not limited to disruption of OSvdI. For example, it has been shown that calcium-dependent inactivation (CDI) is also important for cardiac rhythm (Alseikhan et al. 2002). These authors showed that expression of an inactive calmodulin blocked CDI and prolonged the cardiac action potential (cAP). The role of CDI in TS was tested but variable results were obtained: CDI is not changed (Splawski et al. 2005; Zhu & Clancy, 2007), CDI is reduced (Raybaud et al. 2006), and CDI is accelerated by TS mutation (Barrett & Tsien, 2008). Thus, more work is required to determine if CDI plays a role in TS-induced cardiac arrhythmias. In addition to inactivation, altered deactivation can also be proarrhythmic. It has been shown that drugs that slow L-channel deactivation by favouring the high open probability (Po) state (mode 2) are arrhythmogenic (Mazur et al. 1999; Sicouri et al. 2007). It has been reported that the TS mutation (G436R) generates a phosphorylation site (RxxS) for calmodulin protein kinase II (CaMKII), and phosphorylation of this site (Ser-439) is correlated with increased high Po (mode 2) gating (Erxleben et al. 2006). Thus, slowed deactivation of G436R channels could result from CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of S439. Therefore, a detailed study of TS channel gating mechanisms may provide further insights into arrhythmias induced by these mutant channels.

Closed state voltage-dependent inactivation (CSvdI) is also important to L-channel physiology/pathophysiology, but is less studied than either CDI or OSvdI. This form of inactivation plays a crucial role in setting L-channel availability in arterial smooth muscle and is enhanced by dihydropyridine antagonists to control hypertension (Elmslie, 2004). mRNA containing exon 8a has been found in aorta (Splawski et al. 2004), which suggests that TS mutant L-channels are expressed in arterial smooth muscle. Impaired CSvdI should lead to increased calcium influx into arterial smooth muscle to increase vascular tone, but hypertension is not a pathology associated with TS. CSvdI and OSvdI are thought to share the same inactivation gate (Slesinger & Lansman, 1991a,b), which suggests that investigation of CSvdI could provide insights into the mechanism by which the TS mutation impairs inactivation.

A separate question is whether the TS mutation unconditionally impairs OSvdI or whether it can be pharmacologically corrected. A case study of successful tachyarrhythmia treatment by verapamil has been reported in a patient with Timothy syndrome (Jacobs et al. 2006). The mechanism for this effect was hypothesized to be verapamil-enhanced OSvdI, but this has yet to be directly confirmed. We recently showed that roscovitine, a tri-substituted purine, affects L-channel gating by enhancing OSvdI, which decreases calcium influx during phases 2 and 3 of the cardiac action potential (Yarotskyy & Elmslie, 2007). Roscovitine also slowed L-channel activation, but did not affect deactivation, CSvdI or CDI (Yarotskyy & Elmslie, 2007). Roscovitine-enhanced OSvdI could provide an antiarrhythmogenic action.

Our analysis of TS mutant L-channels revealed that, unlike OSvdI, CSvdI is normal, which is consistent with the absence of hypertension in these patients. The TS mutation slows activation of L-channels at voltages < 10 mV, and, more importantly, slows deactivation at all test voltages, which could facilitate the proarrhythmic effect of the mutation. Surprisingly, mutation of the putative CaMKII phosphorylation (S439A) site in the TS channel failed to restore WT deactivation kinetics, which suggests that increased L-channel phosphorylation is not the mechanism for this effect. We also show that roscovitine can restore OSvdI of TS mutant L-channels, which demonstrates a potential therapeutic treatment for TS patients.

Methods

Construction of mutant channels

Mutant CaV1.2 channels (Wei et al. 1991) were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Briefly, a pair of overlapping primers were used to introduce the desired mutations into CaV1.2 cDNA at positions corresponding to amino acid residues 436 and/or 439 (forward primer for G436R: 5′-CTC GGT GTG TTG AGC cGA GAG TTT TCC AAA GAG AGG-3′, and reverse primer for G436R: 5′-CCT CTC TTT GGA AAA CTC TCg GCT CAA CAC ACC GAG AAC CAG-3′; forward primer for S439E: 5′-TTG AGC GGA GAG TTT gag AAA GAG AGG GAG AAG GCC AAA GC-3′, and reverse primer for S439E: 5′-GGC CTT CTC CCT CTC TTT ctc AAA CTC TCC GCT CAA CAC AC-3′; forward primer for G436R/S439A: 5′-CTC GGT GTG TTG AGC cGA GAG TTT gCC AAA GAG AGG GAG AAG GCC AAA GC-3′, and reverse primer for G436R/S439A: 5′-GGC CTT CTC CCT CTC TTT GGc AAA CTC TCg GCT CAA CAC ACC GAG AAC CAG-3′) (lower case letters indicate mutation sites). The final overlap PCR products were amplified using a 5′ primers lying upstream of an existing ClaI site and a 3′ primer lying downstream of an existing SgrAI site in wild-type α1C plasmid (pCDNA3). The resulting PCR products were excised by ClaI/SgrAI digestion and ligated into ClaI/SgrAI-digested α1C vector. The mutation and integrity of each α1C mutant was confirmed by qualitative restriction map analysis and directional DNA sequence analysis of the entire subcloned region. Functional expression of the mutant cDNAs was confirmed by Western blot analysis and patch-clamp electrophysiology.

HEK cell transfection

We utilized the calcium phosphate precipitation method to transfect HEK293 cells with wild-type (WT), G436R, G436R/S439A, and S439E L-channels, which provided highly reproducible expression 24–72 h after transfection. HEK293 cells were maintained in standard Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic–antimycotic mixtures (regular medium), at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator. For transfection the medium was changed to DMEM/F-12 medium containing 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic mixtures. HEK293 cells were transfected by adding 1 ml of precipitated transfecting solution containing Hepes buffered saline (HeBS), 50 mm CaCl2 and cDNA plasmids as follow: 11 μg α1C subunit, 8.5 μg α2δ, 5.5 μg β1b, 2.15 μg TAG (to increase expression efficiency) and 1 μg GFP (to visualize transfected cells), and incubated for 8 h after which the medium was replaced by the standard DMEM. The transfected cells were split into 35 mm dishes that served as the recording chamber.

Measurement of ionic currents

Cells were voltage clamped using the whole-cell configuration of the patch clamp technique. Pipettes were pulled from Schott 8250 glass (Garner Glass, Claremont, CA, USA) on a Sutter P-97 puller (Sutter Instruments Co., Novato, CA, USA). Currents were recorded using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and digitized with ITC-18 data acquisition interface (Instrutech Corp., Port Washington, NY, USA). Experiments were controlled by an Apple Power Macintosh G3 computer running S5 data acquisition software written by Dr Stephen Ikeda (NIH, NIAAA, Bethesda, MD, USA). Leak current was subtracted online using a P/4 protocol. All recordings were carried out at room temperature and the holding potential was −120 mV. Whole-cell currents were digitized depending on test step duration at 50 (25 ms), 10 (200 ms), and 4 (1000 ms) kHz after analog filtering at 1–10 kHz.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using IgorPro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) running on a Macintosh computer. Step currents were measured as the average of 1 ms at the end of the voltage step. Activation τ (τAct) was determined by fitting a single exponential function to the step current after a 0.3 ms delay (Buraei et al. 2007). OSvdI was measured using 1000 ms voltage steps. The magnitude of inactivation was measured from the IPost/IPre ratio from a triple pulse protocol consisting of identical 25 ms pre- and postpulse steps (to elicit peak current) bracketing a 1000 ms test pulse to voltages ranging from −120 mV to +60 mV. CSvdI was induced by a change in holding potential (HP) from −120 mV to −60 mV. Steps of 25 ms were applied from the HP to a voltage that evoked maximum step current at 1 s intervals. Fractional inactivation was calculated as 1 −I−60/I−120, where I−60 and I−120 are averaged currents measured at HP −60 mV and −120 mV, respectively. The protocol sequence was HP −120 mV (0.5 min), −60 mV (2.5 min), and back to −120 mV (2.5 min) (Fig. 2B). Currents from the last five steps of each HP were averaged. To minimize an effect of rundown, the averaged currents from HP −120 before and after HP −60 mV were averaged again to obtain I−120. Group data were calculated as means ±s.d. throughout the paper. Student's t test for paired data was used for within-cell comparisons. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD post hoc test was used to test for differences among three or more independent groups.

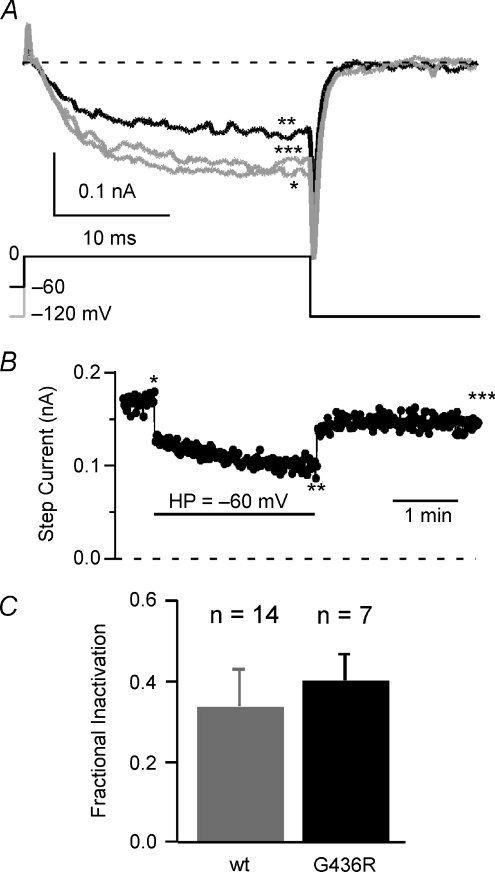

Figure 2. CSvdI is not impaired by the TS mutation.

A, the traces show TS mutant (G436R) L-currents evoked by 25 ms pulses to 0 mV from HP −120 mV (*grey), −60 mV (**black), and upon return to −120 mV (***grey). B, the CSvdI time course from TS mutant L-currents was obtained by pulsing (25 ms to 0 mV) at 1 s intervals. Horizontal bar shows the HP =−60 mV duration. Asterisks show the temporal position of currents shown on panel A. C, mean (±s.d.) fractional inactivation is shown for WT (grey, n= 14) and G436R (black, n= 7) channels (not significantly different).

Computer simulations

Simulated currents and action potentials were generated using Axovacs 3 (written by Stephen W. Jones, Case Western Reserve University) on a Macintosh G4 computer running Virtual PC 6 (Microsoft, Inc., Seattle, WA, USA). Voltage-dependent rate constants (kx) in the model were calculated from:

where Ax is the rate constant at 0 mV, V is the voltage and zx is the charge moved, and R, T, F are the gas constant, absolute temperature and Faraday's constant, respectively. Four channel models were employed to simulate cardiac action potential (cAP): the Hodgkin–Huxley voltage-dependent sodium channel model (Hodgkin & Huxley, 1952), the Hodgkin–Huxley delayed rectifier potassium channel model (Hodgkin & Huxley, 1952), a human ether-a-go-go related gene (HERG) channel model, and a cardiac L-type calcium channel model (Fig. 7A, Table 1). The HERG channel model is shown below (Scheme 1) and the parameters are listed in

| (Scheme 1) |

Table 2. The parameters were adjusted from Wang et al. (1997) to reproduce the gating of HERG channels stably expressed in HEK293 cells (Ganapathi, Kester and Elmslie, unpublished observations).

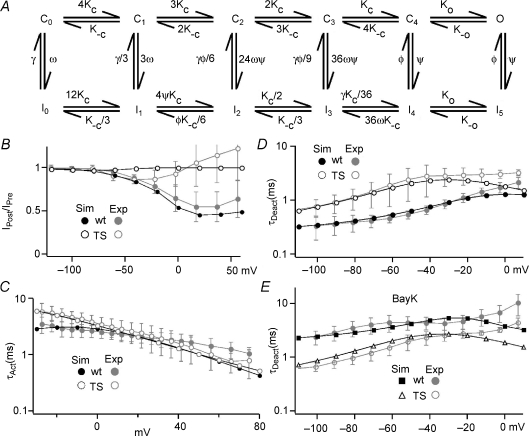

Figure 7. Our L-channel gating model reproduces experimental results from WT and TS channels.

A, the scheme for the L-channel model. C0–C4 are closed states and O represents the open state. I0–I5 are inactivated states. Kc and K−c are voltage-dependent rate constants for the forward and backward transitions, respectively, between closed states and between inactivated states (Table 1). B, simulations (Sim, black) using WT (filled circles) and TS mutant channel (open circles) models demonstrate good correspondence with experimental results (Exp, grey) for OSvdI. The same voltage protocols were used to generate both simulated and experimental results. C, the TS mutation slows the activation at voltages < 10 mV for both theoretical and experimental data. The symbols have the same meaning as for panel B. D, the TS model nicely reproduces our experimental results on the voltage dependence of τDeact for both WT and TS channels. The symbols have the same meaning as for panel B. E, the WT (filled squares) and TS (open triangles) models were also able to reproduce that effect of Bay K8644 on the τDeactversus voltage relationship and TS mutant channels. The grey symbols represent the experimental results.

Table 1.

The parameters for WT and TS L-channel models

| WT | TS | WT + Bay | TS + Bay K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ac | 520 | 520 | 520 | 520 |

| A−c | 200 | 45 | 200 | 45 |

| z | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| ω | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| γ | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| φ | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| ψ | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Ko | 300 | 300 | 3000 | 1000 |

| K−o | 3500 | 3500 | 556 | 3500 |

Ac and A−c (s−1) are the forward and backward rates at 0 mV for the closed–closed transitions (Kc and K−c, respectively) and z is the charge moved during those transitions. All other rate constants are voltage independent.

Table 2.

Rate parameters for the HERG model (Scheme 1)

| Forward rates |

Backwards rates |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | z | A | z | ||

| k1 | 2 | 0.6 | k−1 | 50 | −0.6 |

| k2 | 10 | — | k−2 | 10 | — |

| k3 | 14 | 1.5 | k−3 | 0.1 | −1.5 |

| k4 | 90 | 0.6 | k−4 | 20 | −0.6 |

A (s−1) is the rate constant at 0 mV and z is the charge moved.

The external and internal ionic concentrations for the cAP simulations (Fig. 8) were sodium 140 and 10 mm, potassium 5 and 140 mm, and calcium 2 and 0.0001 mm, respectively. The membrane conductances were 150 nS for L-channels, 15 nS for sodium channels, 5 nS for HERG channels and 0.05 nS for the delayed rectifier potassium channels. Simulated data were analysed using IgorPro.

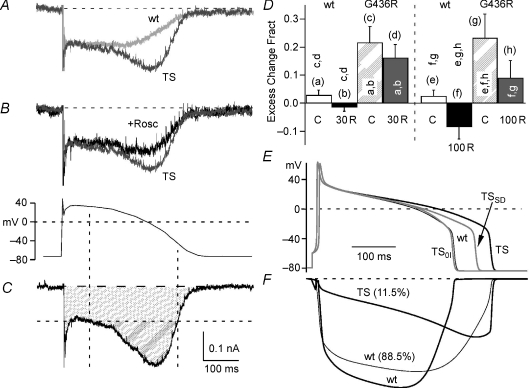

Figure 8. The TS mutation induces proarrhythmic changes to Ca2+ influx evoked by the cAP.

A, traces illustrate the calcium current generated during the cAP through WT (WT, grey) and TS channels (TS, dark grey). The currents are scaled to the initial portion of the plateau phase and superimposed to highlight the differences. The cAP waveform used to generate these currents is shown below panel B. These currents (panels A–D) were recorded in an external solution containing 5 mm Ca2+ and the time scale bar is the same as for panel C. B, the traces illustrate the effect of 100 μm roscovitine (+Rosc, black) on cAP-generated calcium currents through TS channels (TS, dark grey). The currents are scaled to the initial portion of the plateau phase and superimposed. C, the calcium current generated by the cAP (above) is used to illustrate the calculation of excess charge (double hatched area), and the horizontal dashed line (threshold line) delineates the plateau phase of inward calcium current. Vertical dashed lines illustrate the section of the cAP over which the excess charge is observed. To calculate the fractional excess charge, we determine the charge under the threshold line (Z; single hatched area) as well as the total charge influx (ZT; single + double hatched areas). Fractional excess charge is calculated by the ratio (ZT−Z)/ZT. D, fractional excess charge is near zero for WT channels (0.03 ± 0.02, n= 4), but is significantly increased by the TS mutation (G436R, 0.22 ± 0.06, n= 4). Roscovitine reduces the fractional excess charge in dose-dependent manner. The bar graph shows data for control (C), 30 μm roscovitine (30 R), and 100 μm roscovitine (100 R). Each column is marked by a letter in parentheses, and statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) is shown in the vertically oriented letters. E and F, simulated cAP (E) and the underlying calcium currents (F) illustrate proarrhythmic properties of TS-induced changes in L-channel gating. The WT cAP is generated with 100% of the calcium conductance contributed by the WT L-channel model. The calcium conductance for all TS cAPs is composed of 88.5% WT and 11.5% TS model (Splawski et al. 2004). The three models used are TS (slowed deactivation + Zero OSvdI), TSSD (only slowed deactivation) and TS0I (only Zero OSvdI). The calcium currents (F) are shown for 100% WT (WT, thick grey trace) and for a conductance mixture of 88.5% WT (WT, thin grey trace) and 11.5% TS model (thick black trace). In spite of a relatively small membrane conductance, the TS model generated a larger current during the repolarization phase of the cAP.

Solutions

For the transfection HeBS contained (in mm) 140 NaCl, 25 Hepes and 1.4 Na2HPO4; pH 7.10 adjusted using 5 n NaOH. The internal pipette solution contained (in mm) 104 N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMG)-Cl, 14 creatine-PO4, 6 MgCl2, 10 NMG-Hepes, 5 Tris-ATP, 0.3 Tris-GTP and 10 NMG-EGTA, with osmolarity 280 mosmol l−1 and pH 7.3. The external recording solution for most recordings contained (in mm) 30 BaCl2, 100 NMG-Cl, 10 NMG-Hepes, with osmolarity 300 mosmol l−1 and pH 7.3. For the cardiac action potential waveform experiments (Fig. 8A–D), Ba2+ in the external solution was replaced with 5 mm Ca2+ and the NMG-Cl concentration was adjusted to maintain osmoarlity. R-roscovitine was prepared as a 50 mm stock solution in DMSO and stored at −30°C. All external solutions contained the same DMSO concentration so that the roscovitine concentration was the sole variable when changing solutions. Test solutions were applied from a gravity-fed perfusion system with an exchange time of 1–2 s.

Chemicals

We used R-roscovitine from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). DMEM–F12, DMEM, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100× antibiotic/antimycotic were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Other chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

Results

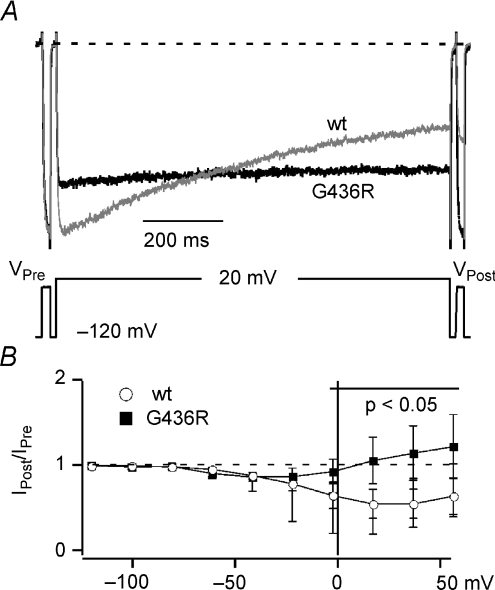

Timothy syndrome mutation impairs OSvdI

We compared OSvdI using a three-pulse protocol (see Methods) for both WT and TS L-channels to ensure that our model corresponds well with previously published observations (Splawski et al. 2004, 2005; Raybaud et al. 2006; Barrett & Tsien, 2008). IPost/IPre was plotted against inactivating voltage to generate the inactivation versus voltage relationship (Fig. 1). The maximum OSvdI was observed at +20 mV, where 45 ± 17% of WT L-channels inactivated over a 1 s step (n= 14), while no inactivation was observed at +20 mV in TS L-channels (IPost/IPre= 1.06 ± 0.27; n= 7) (Fig. 1B). The TS channels did show a small degree of inactivation that peaked at −40 mV (IPost/IPre= 0.87 ± 0.05; n= 7), but this may reflect CSvdI (see next section). These data correspond well with previous observations (Splawski et al. 2004, 2005; Raybaud et al. 2006; Barrett & Tsien, 2008) and show that the G436R mutation is an appropriate TS model.

Figure 1. Timothy syndrome mutation impairs OSvdI.

A, representative records (top) of L-currents evoked by a three-pulse voltage protocol (bottom) for WT (grey) and G436R (TS) channels (black). The prepulse (IPre) and postpulse (IPost) currents were elicited by 25 ms steps to 0 mV, while inactivation was induced by a 1000 ms step to +20 mV. Currents were normalized to IPre. B, the plot of IPost/IPre ratio versus 1000 ms inactivating voltage demonstrates impaired OSvdI for G436R (▪, n= 7) versus WT L-channels (○, n= 14). Error bars show standard deviation. The bold horizontal line shows the voltage range over which OSvdI magnitudes for WT and G436R are significantly different (P < 0.05). Dashed line shows IPost/IPre= 1 (no inactivation).

Timothy syndrome mutation does not affect CSvdI

CSvdI regulates the number of channels available for activation during membrane depolarization. CSvdI and OSvdI appear to share a common inactivation gate (Slesinger & Lansman, 1991a,b), so it seems likely that CSvdI could also be impaired by the TS mutation. CSvdI was measured by testing the effect of a 2.5 min depolarization from a HP of −120 to −60 mV. The fractional inactivation at −60 mV was 0.33 ± 0.09 (n= 14) and 0.40 ± 0.07 (n= 7; not significantly different) for WT and TS L-channels, respectively (Fig. 2C). Surprisingly, CSvdI is normal in TS mutant L-channels, which suggests previously unrecognized differences in the gating processes involved in CSvdI versus OSvdI.

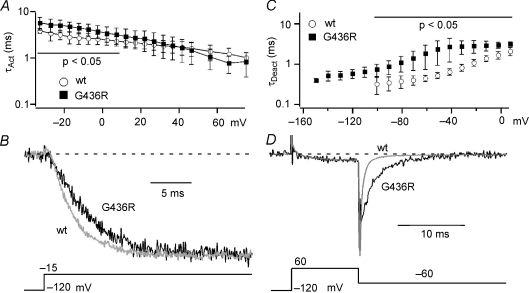

Timothy syndrome mutation affects activation and deactivation kinetics

Previous work using this TS model showed slowed activation of these channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Raybaud et al. 2006). However, the effect of the TS mutation on deactivation has not been examined. We compared the kinetics of activation and deactivation for both WT and TS mutant channels by fitting these processes using single exponential equations to generate τAct and τDeact (Buraei et al. 2005; Yarotskyy & Elmslie, 2007). We found that the TS channels activate significantly more slowly at voltages < 10 mV, but τAct at more depolarized voltages was not affected (Fig. 3A and B). τDeact was significantly increased for TS versus WT channels at all test voltages ranging from −100 mV to 10 mV (Fig. 3C and D). These changes will enhance Ca2+ influx during repolarization of cardiac action potential (cAP), which may lead to prolongation of the cAP and arrhythmogenesis (see Fig. 8).

Figure 3. The TS mutation slows activation and deactivation of cardiac L-channels.

A, the TS mutation (G436R, filled squares) significantly (P < 0.05, horizontal line) slows activation versus WT (open circles) at voltages < 10 mV. B, representative traces are normalized to the maximum current to illustrate activation kinetics for WT (grey) and TS (G436R, black) channels. The voltage protocol is shown under the traces. C, the TS mutation (G436R, filled squares) significantly (P < 0.05) slows deactivation versus WT (open circles) across all voltages. The data in panels A and C are shown as mean ±s.d.D, the superimposed currents were normalized to peak step current to highlight slowed deactivation kinetics for G436R (black) versus WT (grey) channels. The voltage protocol is shown under the traces.

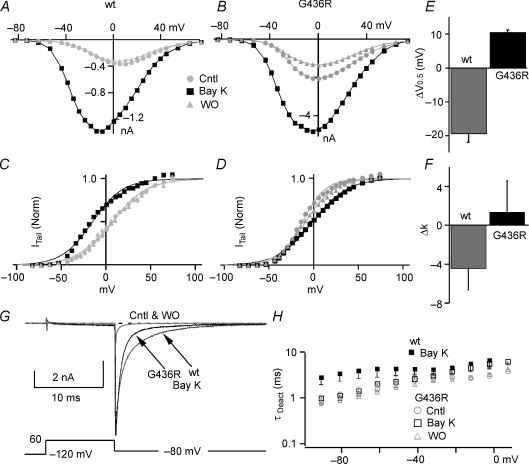

Bay K8644 fails to slow deactivation of TS mutant L-channels

It has been shown that (±)-Bay K8644 can be proarrhythmic by prolonging cAP, which appears to result from Bay K8644 induced slowed deactivation (Sicouri et al. 2007). Other effects of Bay K8644 on whole-cell L-current are an increase in step current amplitude and a 20 mV left-shift of the half-activation voltage. All of these effects are associated with Bay K8644-induced high Po (mode 2) gating (Hess et al. 1984; Marks & Jones, 1992). Since the TS mutation slows deactivation, we wondered if Bay K8644 would have an additional effect. In WT L-channels, 0.3 μm (±)-Bay K8644 induced a negative shift in the half-activation voltage (ΔV0.5=−19.4 ± 2.7 mV; n= 3), a 6-fold increase in current amplitude (6.1 ± 2.0-fold) and a significant slowing of deactivation (Fig. 4). Of these effects, only the increase in current was observed in TS channels (7.9 ± 2.1-fold; not significantly different from WT). The half-activation voltage was positively shifted (ΔV0.5= 10.5 ± 0.9 mV, n= 3) for TS channels (Fig. 4C, D and E), and Bay K8644 had no significant effect on τDeact at voltages < −20 mV (Fig. 4G and H). In this voltage range, τDeact of TS channels is smaller (faster deactivation) than that of WT L-channels in Bay K8644. Thus, TS channels dissociate the Bay K8644 effects on kinetics and V0.5 from the enhancement of current amplitude.

Figure 4. Effect of (±)-Bay K8644 on WT and TS mutant L-channels.

A and B, typical current versus voltage relationship measured from step currents for wild-type (A) and G439R (B) channels for control (Cntl, circles), 0.3 μm (±)-Bay K8644 (Bay K, squares), and washout (WO, triangles). C and D, the activation versus step voltage relationship obtained from tail currents normalized to that following a step to +80 mV is plotted for WT (C) and G436R (D) (same symbols as panel A) channels. The smooth lines are single Boltzmann equation fits to the data to yield V0.5 and slope factor (k). E, the Bay K8644-induced change in activation V0.5 (ΔV0.5) is negative for WT (grey, n= 3), but positive for G436R (black, n= 3) channels. Data are shown as means ± standard deviation and are significantly different for WT versus TS (P < 0.001). F, the Bay K8644-induced change in activation slope factor (Δk) is negative for WT (grey, n= 3), but not statistically different from zero for G436R (black, n= 3). Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation and are significantly different for WT versus TS mutant (P < 0.05). G, typical traces show the effect of Bay K8644 on tail current. Grey traces are control (Cntl) and washout (WO) for G436R mutant. Black traces are WT (right arrow) and G436R (left arrow) currents plus Bay K8644 (Bay K). The vertical scale lines indicate current amplitude for WT (right line) and G436R (left line). Note that Bay K8644 makes WT deactivation slower than that for TS channels. H, τDeact was determined from single exponential fitting of tail currents measured at the indicated voltage following a 10 ms +60 mV step to activate the channels. τDeact was plotted versus tail voltage for G436R (open symbols), control (Cntl, grey circles), 0.3 μm Bay K8644 (Bay K, squares) and washout (WO, grey triangles) at voltages < −20 mV (not significantly different). The filled squares represent τDeact from WT channels in the presence of Bay K to highlight a difference between Bay K-induced kinetics for WT and TS channels.

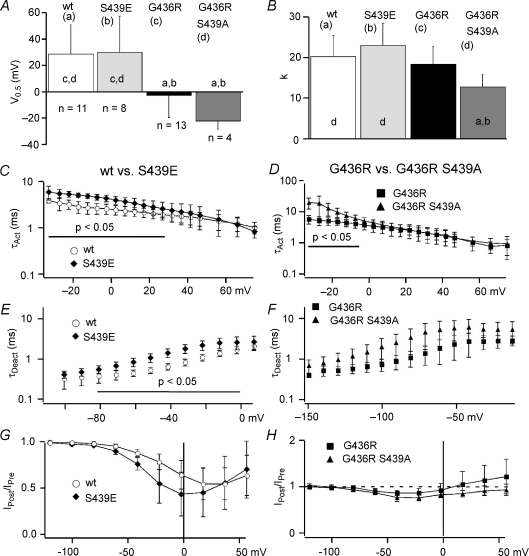

Slowed deactivation does not result from Ser-439 phosphorylation

It has been reported that the TS mutation (G436R) generates a phosphorylation site (RxxS) for calmodulin protein kinase II (CaMKII), and phosphorylation of this site (Ser-439) is correlated with increased high Po (mode 2) gating (Erxleben et al. 2006). Thus, slowed deactivation of G436R channels could be caused by CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of S439. The data reported by (Erxleben et al. 2006) were obtained from single channels recorded under conditions designed to maintain normal intracellular Ca2+ levels. However, our experiments utilized 30 mm Ba2+ in the extracellular solution and an internal solution with 10 mm EGTA, which together should prevent CaMKII activation. To further investigate a possible role for S439, we examined macroscopic currents from HEK293 cells expressing either double mutant G436R/S439A channels (which removes the phosphorylation site) or channels with a S439E mutation (which is engineered to mimic phospho-Ser-439 by replacing serine with a negatively charged glutamate). Deactivation of the S439E mutant was significantly slower than WT, but similar to the TS mutant, which supports a phosphorylation mechanism (Fig. 5E and F). However, replacing the potential phosphorylation site with alanine (G436R/S439A) failed to restore fast deactivation kinetics, since there was no significant difference with TS channels (Fig. 5F). Thus, phosphorylation of Ser-439 cannot explain the slowed deactivation observed here.

Figure 5. Phosphorylation cannot explain the effect of the TS mutation on L-channel gating.

All data are presented as means ±s.d.A and B, V0.5 (A) and slope factor (k) (B) were obtained from Boltzmann fitting of the tail current activation versus voltage relationship and are compared among WT (a, n= 11), S439E (b, n= 8), G436R (c, n= 13), and G436R/S439A (d, n= 4) channels. Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) between the channels is shown as lower case symbols near base of the bars. Gating comparisons of WT (open symbols) versus S439E (♦) channels (C, E, G) and G436R (▪) versus G436R/S439A (▴) channels (D, F, H). C and D, τAct was determined from single exponential fitting as described in Methods and is plotted versus step voltage. E and F, τDeact was determined from single exponential fitting of tail currents as described in Methods. The voltage range over which results are significantly different (P < 0.05) is indicated by a horizontal line. G and H, IPost/IPreversus voltage shows inactivation induced by 1000 ms inactivation steps over a range from −120 mV to +60 mV. Note the left-shift in the relationship for S439E versus WT.

Other effects of the TS mutation were also not consistent with Ser-439 phosphorylation. The slowed activation induced by the TS mutation was reproduced by S439E, but τAct was even larger for the G436R/S439A mutant at voltages < −5 mV (instead of being smaller like WT channels) (Fig. 5C and D). The TS mutation induced a significant left shift in V0.5, but that was not reproduced by S439E and a similar shift was observed with G436R/S439A (Fig. 5A). Finally, phosphorylation cannot explain the effect of the TS mutation on OSvdI. Using the three-pulse inactivation protocol, we have found that inactivation was negatively shifted for S439E compared to WT (Fig. 5G), but maximum fractional OSvdI was not significantly altered (0.45 ± 0.17 (n= 14) and 0.56 ± 0.24 (n= 8) for WT at 20 mV and S439E at 0 mV, respectively). OSvdI was also not restored by mutating Ser-439, since there was no significant difference in inactivation between the TS mutant and G436R/S439A channels (Fig. 5H). Under our conditions the observed effect of the TS mutation on L-channel gating does not involve phosphorylation of Ser-439.

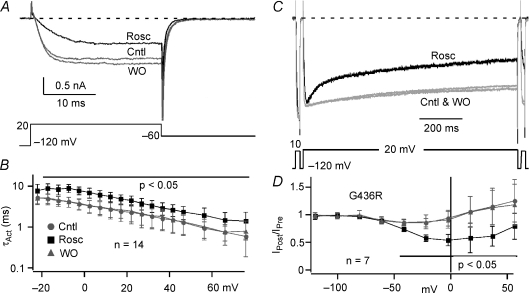

Roscovitine restores OSvdI of TS mutant L-channels

We recently showed that roscovitine enhances OSvdI of WT L-channels (Yarotskyy & Elmslie, 2007), which motivated us to determine if this drug can restore TS-impaired inactivation. Using the maximally effective roscovitine concentration (100 μm) we found that OSvdI was enhanced in TS channels. Maximum fractional OSvdI was restored by roscovitine to 0.45 ± 0.10 (n= 7) compared to 0.45 ± 0.17 for WT control. One difference was the half-inactivation voltage was left-shifted for the TS channel + roscovitine, which is consistent with the TS mutant-induced 25 mV left-shift in the activation V0.5 (Fig. 5A). As in WT L-channels (Yarotskyy & Elmslie, 2007), roscovitine slowed activation of TS mutant channels (Fig. 6A and B), which was significantly different across all voltages (P < 0.05, n= 14, Fig. 6B). The slowed activation induced by roscovitine should impair re-activation of L-channels during action potential repolarization that can result in early afterdepolarizations (Carmeliet, 1999; Bers, 2002; Ter Keurs & Boyden, 2007).

Figure 6. Roscovitine normalizes inactivation of TS mutant L-channels.

A, typical records show the effect of 100 μm roscovitine (Rosc, black trace) to slow TS channel activation relative to control (Cntl, grey) and washout (WO, grey). B, τActversus voltage for the TS mutant in control (Cntl, grey circles), 100 μm Rosc (black symbols), and WO (grey triangles). Roscovitine significantly (P < 0.05) slowed activation for voltages > −20 mV (horizontal line). C, roscovitine-enhanced OSvdI of TS (G436R) mutant L-current (Rosc, black trace). Grey traces are control and washout (Cntl & WO). D, the IPost/IPreversus voltage relationship illustrates the normalization of TS mutant channel inactivation by 100 μm roscovitine (black squares) relative to control and washout (grey symbols). Significantly different results (P < 0.05) are indicated by horizontal line. Data are presented as means ±s.d.

Mathematical model of L-type calcium channels

We wanted to further explore the gating defects induced by the TS mutation and modified previously developed models (Marks & Jones, 1992; Tanskanen et al. 2005; Mahajan et al. 2008) to reproduce our experimental data. Our goal was to first adjust model parameters to fit our WT L-channel results and then find the model with the fewest parameter adjustments that could reproduce our TS mutant data. We also wanted to preserve the Hodgkin–Huxley formalism for activation/deactivation gating (i.e. independence) and were careful to maintain microscopic reversibility (Fig. 7A). The model was greatly simplified by excluding CDI. We assume that each voltage-dependent transition moves an equal amount of charge in both the forward and reverse directions, and that the close–open transition is voltage independent (Marks & Jones, 1992; Mahajan et al. 2008). The voltage-dependent and voltage-independent transitions along the activation/deactivation pathway are mirrored in the parallel inactivation pathway (Hodgkin & Huxley, 1952). The inactivation states I0 and I1 are mainly accessible when membrane potential is below the activation threshold and, thus, represent CSvdI, while I4 and I5 were accessible only from activated channels (i.e. C4 or O) so that they represent OSvdI. The intermediate inactivation states (I2 and I3) are accessed from closed states that are predominantly occupied at potentials around the threshold for channel activation so that they contribute strongly to inactivation when relative Po is < 0.5 (partial activation). Since these inactivated states will contribute apparent open state inactivation, we defined their rate constants as products of scaled rate constants for CSvdI (γ and ω) and OSvdI (φ and ψ). TS-impaired OSvdI was simulated by setting ψ= 0, and slowed deactivation was reproduced by decreasing the backward closed–closed (C→C) rate constant K−c (TS model; Table 1). We could have achieved slowed deactivation by decreasing the open to closed (O→C) rate constant, but previous single channel recordings clearly demonstrated brief open times (like WT channels) for the G436R/S439A mutant (Erxleben et al. 2006). However, this double mutation showed slowed deactivation similar to the TS mutant (G436R), which together strongly supported WT O→C gating in these mutants and focused our attention on C→C transitions.

Computer simulations revealed good correspondence between experimental and theoretical results for both WT and TS mutant channels (Fig. 7B–E). The TS model showed a 29 mV left shift of activation I–V versus 31 mV for our experiments. We have also achieved satisfactory matching of the activation and deactivation kinetics for both WT and TS mutant channels (Fig. 7C and D). The effect of Bay K8644 on WT channels was simulated by increasing the C→O rate (Ko) and reducing the O→C rate (K−o) (Table 1), which achieved a slowing of deactivation that mimicked our experimental results. To reproduce the effect of Bay K8644 on TS mutant channels, we increased the forward C→O rate constant, but the O→C rate was not changed (Table 1). The increased forward rate constant generated a 3-fold increase in step current, but that was smaller than the 8-fold increase we observed experimentally. The absence of an effect on the O→C rate was needed to mimic lack of a Bay K8644 effect on deactivation τ as with our experimental data. We ran many simulations with altered O→C transition rates and found that any decrease would obviously slow deactivation. Our simulations support our hypothesis that the TS mutation slows deactivation by reducing the backwards C→C rate constant. In addition, our modelling suggests that the TS mutant may disrupt the ability of Bay K8644 to alter the O→C transition rate.

The physiological impact of the TS mutation

The TS mutation is strongly associated with arrhythmia, but the effect of the mutation on physiologically activated L-current has yet to be investigated. We reasoned that insights into the arrhythmogenic properties of the TS mutation would come from such an investigation. As a first step, we compared currents (5 mm Ca2+) generated by WT versus TS mutant channels activated by a human cAP waveform (Yarotskyy & Elmslie, 2007). As we had observed previously, the WT channels showed a stable current during the plateau phase of the cAP that declined with repolarization (Fig. 8A). The TS channels showed a similar plateau phase current, but the current transiently increased during repolarization creating an influx of excess charge. We quantified this excess charge by using the plateau current level to determine a threshold level (Fig. 8C; see also legend Fig. 8), and found that excess charge was significantly increased by the TS mutation over WT channels (Fig. 8D). As expected from increased inactivation, roscovitine reduced the excess charge so that in the presence of 100 μm roscovitine the TS fractional excess charge was not statistically different from WT (Fig. 8B and D). Thus, drugs like roscovitine that enhance inactivation can restore normal Ca2+ influx via TS mutant channels during the cAP.

We hypothesized that both TS-induced slowed deactivation and impaired OSvdI contribute to arrhythmogenesis, which was tested by simulating the cAP (Fig. 8E). The four models combined to generate this simulation were the minimum needed to reproduce the human cAP, and the duration and shape of the cAP were obtained by adjusting the membrane conductance for each model (see Methods). To simulate the cAP from a TS patient, we replaced 11.5% of the WT membrane conductance with the TS channel model (Fig. 8D). This simulated the estimated relative abundance of the heterozygous mutant protein (∼11.5% exon 8a versus 88.5% exon 8) in human cardiac myocytes (Splawski et al. 2004). We measured the cAP duration (cAPD) at −40 mV and found that cAPD was dramatically increased from 306 ms (WT) to 395 ms (29% increase) by the addition of the TS mutant model even though it accounted for only 11.5% of the total calcium conductance. To determine the impact of slowed deactivation versus impaired OSvdI, we replaced our TS model with models that had each gating property separately altered. We simulated TS-impaired OSvdI by setting ψ= 0 in our WT model (normal K−c) and separately simulated slowed deactivation by decreasing K−c (normal ψ). In each case, the mutant channel model comprised 11.5% of the total calcium conductance. Surprisingly, impaired inactivation alone caused no increase in cAPD from 306 to 303 ms (or 1% decrease), while slowed deactivation alone increased cAPD to 360 ms (or 18% increase). We conclude that both slowed deactivation and impaired OSvdI synergistically increase cAPD to generate the long QT intervals observed in TS patients (Splawski et al. 2004).

Discussion

Timothy syndrome-impaired OSvdI of cardiac L-type calcium channels has a major impact on Ca2+ influx into the heart and other cell types expressing this channel isoform (Splawski et al. 2004, 2005), and impaired OSvdI has been shown to be proarrhythmic in mathematical models (Faber et al. 2007). We have found that other L-channel gating mechanisms are also altered by the TS mutation, and slowed deactivation plus impaired OSvdI may synergistically contribute to Timothy syndrome pathology. We have also investigated other gating processes that provide clues the mechanisms that underlie slowed deactivation and impaired OSvdI. The absence of an effect of the mutation on CSvdI demonstrates that these two classes of voltage-regulated inactivation can be independently modulated (Yarotskyy & Elmslie, 2007). In addition, the surprising inability of Bay K8644 to slow deactivation or left-shift the activation V0.5 of these channels suggests that the mutation alters mechanism by which Bay K8644 affects gating.

TS mutation affects OSvdI but not CSvdI

Calcium channel antagonists that target inactivation gating are helpful in treatment of such cardiovascular diseases as hypertension, angina pectoris and some ventricular arrhythmias (Sanguinetti & Kass, 1984; Motoike et al. 1999; Elmslie, 2004). Dihydropyridines (DHPs), a class of L-channel antagonists, preferably enhance CSvdI (Sanguinetti & Kass, 1984) to reduce excess Ca2+ influx into arterial smooth muscle, which makes DHPs very effective in the treatment of hypertension (Elmslie, 2004). We expected impaired CSvdI for TS mutant channels because of strong evidence that a single gate mediates both OSvdI and CSvdI (Slesinger & Lansman, 1991a,b). Impaired CSvdI will result in an enhanced L-channel availability that would be expected to increase arterial smooth muscle contraction leading to hypertension. However, the Timothy syndrome phenotype does not include hypertension (Splawski et al. 2004, 2005), and our results reveal one reason could be that CSvdI functions normally in TS mutant L-channels.

As stated above, there is good evidence for a common inactivation gate for both CSvdI and OSvdI (Slesinger & Lansman, 1991a,b). Perhaps the effect of the TS mutation indicates a need to reinvestigate this idea. However, a more likely possibility is that these two classes of voltage-regulated inactivation are controlled by different mechanisms. Thus, they could share a common gate, but the TS mutation disrupts the coupling between the OSvdI control mechanism and the gate while leaving CSvdI unaffected. Support for this idea comes from sodium channel inactivation, where fast voltage-dependent inactivation is primarily triggered by movement of S4 in domain IV (Chen et al. 1996; Mitrovic et al. 1998; Horn et al. 2000), while voltage sensor movement within domains I–III have a larger impact on CSvdI (Chen et al. 1996; Kontis & Goldin, 1997). Differential control mechanisms could explain the sparing of CSvdI by the TS mutation.

TS-slowed deactivation may contribute to cardiac arrhythmias

L-channel deactivation is slowed by treatments that place the channel into the high Po gating mode (mode 2) (Hess et al. 1984; Marks & Jones, 1992). These treatments include Bay K8644 (Hess et al. 1984; Marks & Jones, 1992), β-adrenergic agonists (protein kinase A (PKA) activation) and Ca2+ (CaMKII activation) (Yue et al. 1990; Dzhura et al. 2000). The treatments that slow L-channel deactivation have also been found to be proarrhythmic. Bay K8644 has been shown to prolong the cAP, which led to proarrhythmic early and delayed afterdepolarization development (EAD and DAD, respectively) (Sicouri et al. 2007). In addition, both the PKA inhibitor H-7 and the CaMKII inhibitor W-7 reduced Torsades de Pointes arrhythmia (Mazur et al. 1999). Thus, the slowed deactivation of TS channels will increase cAP induced Ca2+ influx, which is likely to contribute to arrhythmogenesis along with impaired OSvdI. In the brain, the increased Ca2+ influx resulting from combined slowed deactivation and impaired OSvdI likely contributes to the neurological problems associated with this disease. Our recordings of L-currents during the cAP demonstrates the profound impact of the TS mutation on Ca2+ influx. As a result of slowed deactivation and disrupted OSvdI Ca2+ influx via TS channels increased during the repolarization phase of the cAP instead of showing the monotonic decrease observed from WT channels. The resulting excess charge would depolarize the myocyte to lengthen the cAP and could be sufficiently large to trigger inappropriate electrical activity such as EADs (Hirano et al. 1992; Antoons et al. 2007; Thomas et al. 2007). Our cAP simulations demonstrate excess Ca2+ influx with our TS model and also show the profound effect of this excess charge on cAPD.

The slowed deactivation of TS channels is consistent with the mutation inducing the high Po gating mode (mode 2). Indeed, this type of gating has been observed in single channel recordings where TS channels showed a significant enhancement of mean open time (Erxleben et al. 2006). Mutagenesis and pharmacological experiments supported the involvement of CaMKII phosphorylation in TS mutant high Po gating. Specifically, single channel gating was normalized in the G436R/S439A double mutant, which removed the phosphorylation site generated by the TS mutation (RxxS) (Erxleben et al. 2006). This double mutation was not able to normalize gating under our conditions, in which CaMKII activation was prevented by high internal EGTA (10 mm) and the use of Ba2+ as the charge carrier. Thus, this form of slowed deactivation appears to be distinct from high Po (mode 2) gating, which is further supported by the strong effect of Bay K8644 to enhance the current amplitude of TS channels (not significantly different from WT). Thus, Bay K8644 can place TS channels into the high Po gating state, but fails to slow deactivation or left-shift the activation V0.5 as it does for WT channels. These effects can be explained if the TS mutation introduces a new rate-limiting step to channel closing. L-channels have been shown to have voltage-independent open times that has been modelled using voltage-independent rate constants between the last closed state and open state, and Bay K8644 appears to affect this gating step (Marks & Jones, 1992). We propose that the TS mutation slows voltage-dependent closed–closed gating steps so that the channel makes multiple closed–open transitions during deactivation. Our theoretical study strongly supports this idea. We reduced the backward rate constants for C→C transitions, which nicely mimicked our experimental results. The effect of Bay K8644 was simulated by increasing the C→O rate and decreasing the O→C rate (Marks & Jones, 1992). However, for TS mutant channels only the C→O rate could be altered to achieve good correspondence with our voltage dependence of τDeact results, suggesting that TS mutation uncouples deactivation from Bay K8644. One problem with this model was that we were not able to achieve as large an increase in simulated TS current with the addition of Bay K8644 (3-fold versus 8-fold). Thus, more work is required to understand the effect of the TS mutation on L-channel gating and on the effect of DHP agonists.

Our cAP simulations revealed proarrhythmic properties of TS-altered L-channel gating. Slowed deactivation alone prolonged cAP, while impaired OSvdI alone had no effect in our model. However, we were able to achieve prolonged cAPD if we doubled the level of OSvdI-impaired L-channels as was previously observed (Faber et al. 2007). Thus, impaired OSvdI alone can lead to more Ca2+ influx and an extension of the cAPD, but the rapid closing of active L-channels during cAP repolarization strongly limits the effect on cAPD. On the other hand, slowed L-channel deactivation alone enhances Ca2+ influx during repolarization to increase cAPD, but OSvdI continues to reduce the number of active channels to limit the increase. However, together they synergistically prolonged the cAP because the negative feedback from OSvdI is lost so that only potassium channel activation remains to oppose the excess Ca2+ influx and terminate the cAP. As a result of this synergism it is likely that restoring only one of the disrupted gating mechanisms would strongly reduce the cAPD and, thus, the QT interval to help reestablish normal cardiac rhythm.

Roscovitine restores OSvdI of TS mutant

Roscovitine is currently undergoing Phase II clinical trials as an anticancer drug and the clinically relevant dosing range has been shown to be 10–50 μm (De Azevedo et al. 1997; Meijer et al. 1997; Darios et al. 2005). We have previously shown that roscovitine, a tri-substituted purine, uniquely affects different ion channels at clinically relevant concentrations (Buraei et al. 2005; Buraei et al. 2007; Yarotskyy & Elmslie, 2007; Buraei & Elmslie, 2008). Roscovitine is an open channel blocker of several potassium channels (Buraei et al. 2007), which might be expected to be pro-arrhythmic. However, cardiac arrhythmias have not been observed in human trials to evaluate roscovitine as an anticancer treatment (Fischer & Gianella-Borradori, 2003; Benson et al. 2007). Roscovitine slows activation and enhances OSvdI of WT cardiac L-channels (Yarotskyy & Elmslie, 2007). Here we showed that roscovitine can restore TS-impaired OSvdI to that of WT L-channels. Loss of inactivation from TS channels was suggested to result from an impaired ‘hinged lid’ inactivation mechanism (Splawski et al. 2005; Raybaud et al. 2006) based on the idea that amino acids within the intracellular loop between domains I and II form the inactivation gate (Stotz et al. 2004). Thus, one possibility is that roscovitine (and perhaps verapamil) increases the rate of inactivation gate movement to restore inactivation. However, if CSvdI and OSvdI share the same gate, it would appear that gate movement is not impaired in TS channels. An alternative possibility is that the TS mutation prevents the control mechanism from triggering gate movement for OSvdI. This suggests that roscovitine (and perhaps verapamil) restores the coupling between the control mechanism and the inactivation gate to normalize OSvdI of TS mutant L-channels. Roscovitine also normalized the Ca2+ influx via TS channels during cAP, which supports the idea that the restoration of one of the two gating defects will help to restore normal cardiac rhythm. A recent case study reported that the PAA verapamil decreased ventricular tachyarrhythmia in a patient with Timothy syndrome (Jacobs et al. 2006). Verapamil enhances OSvdI, which was the proposed mechanism for the beneficial effects in the TS patient. Drugs that enhance L-channel OSvdI can normalize action potential-induced Ca2+ influx, which suggests that these drugs will be useful in treating the multiple disorders associated with the TS mutation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yunhua Wang for superb technical assistance. This work was supported by startup funds from the Department of Anaesthesiology at Penn State College of Medicine (K.S.E.), a grant from the Pennsylvania (P.A.) Department of Health using Tobacco Settlement Funds (K.S.E.) and The National Institutes of Health (HL074143, B.Z.P). The PA Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for analyses, interpretations and conclusions presented here.

References

- Alseikhan BA, DeMaria CD, Colecraft HM, Yue DT. Engineered calmodulins reveal the unexpected eminence of Ca2+ channel inactivation in controlling heart excitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17185–17190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262372999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoons G, Volders PGA, Stankovicova T, Bito V, Stengl M, Vos MA, Sipido KR. Window Ca2+ current and its modulation by Ca2+ release in hypertrophied cardiac myocytes from dogs with chronic atrioventricular block. J Physiol. 2007;579:147–160. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CF, Tsien RW. The Timothy syndrome mutation differentially affects voltage- and calcium-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2, L-type calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2157–2162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710501105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson C, White J, De Bono J, O’Donnell A, Raynaud F, Cruickshank C, McGrath H, Walton M, Workman P, Kaye S, Cassidy J, Gianella-Borradori A, Judson I, Twelves C. A phase I trial of the selective oral cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor seliciclib (CYC202; R-Roscovitine), administered twice daily for 7 days every 21 days. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:29–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM. Calcium and cardiac rhythms: physiological and pathophysiological. Circ Res. 2002;90:14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z, Anghelescu M, Elmslie KS. Slowed N-type calcium channel (CaV2.2) deactivation by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor roscovitine. Biophys J. 2005;89:1681–1691. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.052837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z, Elmslie KS. The separation of antagonist from agonist effects of trisubstituted purines on CaV2.2 (N-type) channels. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1450–1461. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z, Schofield G, Elmslie KS. Roscovitine differentially affects CaV2 and Kv channels by binding to the open state. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:883–894. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet E. Cardiac ionic currents and acute ischemia: from channels to arrhythmias. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:917–1017. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Santarelli V, Horn R, Kallen R. A unique role for the S4 segment of domain 4 in the inactivation of sodium channels. J Gen Physiol. 1996;108:549–556. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.6.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darios F, Muriel MP, Khondiker ME, Brice A, Ruberg M. Neurotoxic calcium transfer from endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria is regulated by cyclin-dependent kinase 5-dependent phosphorylation of tau. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4159–4168. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0060-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Azevedo W, Leclerc S, Meijer L, Havlicek L, Strnad M, Kim S. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by purine analogues: crystal structure of human cdk2 complexed with roscovitine. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:518–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0518a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhura I, Wu Y, Colbran RJ, Balser JR, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase determines calcium-dependent facilitation of L-type calcium channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:173–177. doi: 10.1038/35004052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS. Calcium channel blockers in the treatment of disease. J Neurosci Res. 2004;75:733–741. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erxleben C, Liao Y, Gentile S, Chin D, Gomez-Alegria C, Mori Y, Birnbaumer L, Armstrong DL. Cyclosporin and Timothy syndrome increase mode 2 gating of CaV1.2 calcium channels through aberrant phosphorylation of S6 helices. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3932–3937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber GM, Silva J, Livshitz L, Rudy Y. Kinetic properties of the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel and its role in myocyte electrophysiology: a theoretical investigation. Biophys J. 2007;92:1522–1543. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer PM, Gianella-Borradori A. CDK inhibitors in clinical development for the treatment of cancer. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2003;12:955–970. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess P, Lansman JB, Tsien RW. Different modes of Ca channel gating behaviour favoured by dihydropyridine Ca agonists and antagonists. Nature. 1984;311:538–544. doi: 10.1038/311538a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano Y, Moscucci A, January CT. Direct measurement of L-type Ca2+ window current in heart cells. Circ Res. 1992;70:445–455. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J Physiol. 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn R, Ding S, Gruber HJ. Immobilizing the moving parts of voltage-gated ion channels. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:461–476. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs A, Knight BP, McDonald KT, Burke MC. Verapamil decreases ventricular tachyarrhythmias in a patient with Timothy syndrome (LQT8) Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:967–970. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontis KJ, Goldin AL. Sodium channel inactivation is altered by substitution of voltage sensor positive charges. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:403–413. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.4.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan A, Shiferaw Y, Sato D, Baher A, Olcese R, Xie LH, Yang MJ, Chen PS, Restrepo JG, Karma A, Garfinkel A, Qu Z, Weiss JN. A rabbit ventricular action potential model replicating cardiac dynamics at rapid heart rates. Biophys J. 2008;94:392–410. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.98160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks TN, Jones SW. Calcium currents in the A7r5 smooth muscle-derived cell line. An allosteric model for calcium channel activation and dihydropyridine agonist action. J Gen Physiol. 1992;99:367–390. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur A, Roden DM, Anderson ME. Systemic administration of calmodulin antagonist W-7 or protein kinase A inhibitor H-8 prevents torsade de pointes in rabbits. Circulation. 1999;100:2437–2442. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.24.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer L, Borgne A, Mulner O, Chong J, Blow J, Inagaki N, Inagaki M, Delcros J, Moulinoux J. Biochemical and cellular effects of roscovitine, a potent and selective inhibitor of the cyclin-dependent kinases cdc2, cdk2 and cdk5. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:527–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-2-00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrovic N, George AL, Jr, Horn R. Independent versus coupled inactivation in sodium channels. Role of the domain 2, S4 segment. J Gen Physiol. 1998;111:451–462. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.3.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoike HK, Bodi I, Nakayama H, Schwartz A, Varadi G. A region in IVS5 of the human cardiac L-type calcium channel is required for the use-dependent block by phenylalkylamines and benzothiazepines. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9409–9420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raybaud A, Dodier Y, Bissonnette P, Simoes M, Bichet DG, Sauve R, Parent L. The role of the GX9GX3G motif in the gating of high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39424–39436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Kass RS. Voltage-dependent block of calcium channel current in the calf cardiac Purkinje fiber by dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists. Circ Res. 1984;55:336–348. doi: 10.1161/01.res.55.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicouri S, Timothy KW, Zygmunt AC, Glass A, Goodrow RJ, Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the electrocardiographic and arrhythmic manifestations of Timothy syndrome: effects of ranolazine. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesinger PA, Lansman JB. Inactivating and non-inactivating dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channels in mouse cerebellar granule cells. J Physiol. 1991a;439:301–323. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesinger PA, Lansman JB. Inactivation of calcium currents in granule cells cultured from mouse cerebellum. J Physiol. 1991b;435:101–121. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splawski I, Timothy KW, Decher N, Kumar P, Sachse FB, Beggs AH, Sanguinetti MC, Keating MT. Severe arrhythmia disorder caused by cardiac L-type calcium channel mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8089–8096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502506102. discussion 8086–8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM, Decher N, Kumar P, Bloise R, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Joseph RM, Condouris K, Tager-Flusberg H, Priori SG, Sanguinetti MC, Keating MT. CaV1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell. 2004;119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotz SC, Jarvis SE, Zamponi GW. Functional roles of cytoplasmic loops and pore lining transmembrane helices in the voltage-dependent inactivation of HVA calcium channels. J Physiol. 2004;554:263–273. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanskanen AJ, Greenstein JL, O’Rourke B, Winslow RL. The role of stochastic and modal gating of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels on early after-depolarizations. Biophys J. 2005;88:85–95. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.051508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter Keurs HE, Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:457–506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G, Gurung IS, Killeen MJ, Hakim P, Goddard CA, Mahaut-Smith MP, Colledge WH, Grace AA, Huang CLH. Effects of L-type Ca2+ channel antagonism on ventricular arrhythmogenesis in murine hearts containing a modification in the Scn5a gene modelling human long QT syndrome 3. J Physiol. 2007;578:85–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.121921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Liu S, Morales MJ, Strauss HC, Rasmusson RL. A quantitative analysis of the activation and inactivation kinetics of HERG expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1997;502:45–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.045bl.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei XY, Perez-Reyes E, Lacerda AE, Schuster G, Brown AM, Birnbaumer L. Heterologous regulation of the cardiac Ca2+ channel a1 subunit by skeletal muscle b and g subunits. Implications for the structure of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21943–21947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarotskyy V, Elmslie KS. Roscovitine, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, affects several gating mechanisms to inhibit cardiac L-type (CaV1.2) calcium channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:386–395. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue DT, Herzig S, Marban E. β-Adrenergic stimulation of calcium channels occurs by potentiation of high-activity gating modes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:753–757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu ZI, Clancy CE. L-type Ca2+ channel mutations and T-wave alternans: a model study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3480–H3489. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00476.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]