Abstract

Members of the CLC gene family either function as chloride channels or as

anion/proton exchangers. The plant AtClC-a uses the pH gradient across the

vacuolar membrane to accumulate the nutrient

in this organelle. When AtClC-a was

expressed in Xenopus oocytes, it mediated

in this organelle. When AtClC-a was

expressed in Xenopus oocytes, it mediated

exchange

and less efficiently mediated Cl–/H+ exchange.

Mutating the “gating glutamate” Glu-203 to alanine resulted in an

uncoupled anion conductance that was larger for Cl– than

exchange

and less efficiently mediated Cl–/H+ exchange.

Mutating the “gating glutamate” Glu-203 to alanine resulted in an

uncoupled anion conductance that was larger for Cl– than

. Replacing the “proton

glutamate” Glu-270 by alanine abolished currents. These could be

restored by the uncoupling E203A mutation. Whereas mammalian endosomal ClC-4

and ClC-5 mediate stoichiometrically coupled

2Cl–/H+ exchange, their

. Replacing the “proton

glutamate” Glu-270 by alanine abolished currents. These could be

restored by the uncoupling E203A mutation. Whereas mammalian endosomal ClC-4

and ClC-5 mediate stoichiometrically coupled

2Cl–/H+ exchange, their

transport is largely uncoupled from

protons. By contrast, the AtClC-a-mediated

transport is largely uncoupled from

protons. By contrast, the AtClC-a-mediated

accumulation in plant vacuoles

requires tight

accumulation in plant vacuoles

requires tight

coupling. Comparison of AtClC-a and ClC-5 sequences identified a proline in

AtClC-a that is replaced by serine in all mammalian CLC isoforms. When this

proline was mutated to serine (P160S), Cl–/H+

exchange of AtClC-a proceeded as efficiently as

coupling. Comparison of AtClC-a and ClC-5 sequences identified a proline in

AtClC-a that is replaced by serine in all mammalian CLC isoforms. When this

proline was mutated to serine (P160S), Cl–/H+

exchange of AtClC-a proceeded as efficiently as

exchange, suggesting a role of this residue in

exchange, suggesting a role of this residue in

exchange. Indeed, when the corresponding serine of ClC-5 was replaced by

proline, this Cl–/H+ exchanger gained efficient

exchange. Indeed, when the corresponding serine of ClC-5 was replaced by

proline, this Cl–/H+ exchanger gained efficient

coupling. When inserted into the model Torpedo chloride channel

ClC-0, the equivalent mutation increased nitrate relative to chloride

conductance. Hence, proline in the CLC pore signature sequence is important

for

coupling. When inserted into the model Torpedo chloride channel

ClC-0, the equivalent mutation increased nitrate relative to chloride

conductance. Hence, proline in the CLC pore signature sequence is important

for  exchange and

exchange and  conductance both in

plants and mammals. Gating and proton glutamates play similar roles in

bacterial, plant, and mammalian CLC anion/proton exchangers.

conductance both in

plants and mammals. Gating and proton glutamates play similar roles in

bacterial, plant, and mammalian CLC anion/proton exchangers.

CLC proteins are found in all phyla from bacteria to humans and either

mediate electrogenic anion/proton exchange or function as chloride channels

(1). In mammals, the roles of

plasma membrane CLC Cl– channels include transepithelial

transport

(2–5)

and control of muscle excitability

(6), whereas vesicular CLC

exchangers may facilitate endocytosis

(7) and lysosomal function

(8–10)

by electrically shunting vesicular proton pump currents

(11). In the plant

Arabidopsis thaliana, there are seven CLC isoforms

(AtClC-a–AtClC-g)2

(12–15),

which may mostly reside in intracellular membranes. AtClC-a uses the pH

gradient across the vacuolar membrane to transport the nutrient nitrate into

that organelle (16). This

secondary active transport requires a tightly coupled

exchange. Astonishingly, however, mammalian ClC-4 and -5 and bacterial EcClC-1

(one of the two CLC isoforms in Escherichia coli) display tightly

coupled Cl–/H+ exchange, but anion flux is largely

uncoupled from H+ when

exchange. Astonishingly, however, mammalian ClC-4 and -5 and bacterial EcClC-1

(one of the two CLC isoforms in Escherichia coli) display tightly

coupled Cl–/H+ exchange, but anion flux is largely

uncoupled from H+ when  is transported

(17–21).

The lack of appropriate expression systems for plant CLC transporters

(12) has so far impeded

structure-function analysis that may shed light on the ability of AtClC-a to

perform efficient

is transported

(17–21).

The lack of appropriate expression systems for plant CLC transporters

(12) has so far impeded

structure-function analysis that may shed light on the ability of AtClC-a to

perform efficient

exchange. This dearth of data contrasts with the extensive mutagenesis work

performed with CLC proteins from animals and bacteria.

exchange. This dearth of data contrasts with the extensive mutagenesis work

performed with CLC proteins from animals and bacteria.

The crystal structure of bacterial CLC homologues (22, 23) and the investigation of mutants (17, 19–21, 24–29) have yielded important insights into their structure and function. CLC proteins form dimers with two largely independent permeation pathways (22, 25, 30, 31). Each of the monomers displays two anion binding sites (22). A third binding site is observed when a certain key glutamate residue, which is located halfway in the permeation pathway of almost all CLC proteins, is mutated to alanine (23). Mutating this gating glutamate in CLC Cl– channels strongly affects or even completely suppresses single pore gating (23), whereas CLC exchangers are transformed by such mutations into pure anion conductances that are not coupled to proton transport (17, 19, 20). Another key glutamate, located at the cytoplasmic surface of the CLC monomer, seems to be a hallmark of CLC anion/proton exchangers. Mutating this proton glutamate to nontitratable amino acids uncouples anion transport from protons in the bacterial EcClC-1 protein (27) but seems to abolish transport altogether in mammalian ClC-4 and -5 (21). In those latter proteins, anion transport could be restored by additionally introducing an uncoupling mutation at the gating glutamate (21).

The functional complementation by AtClC-c and -d

(12,

32) of growth phenotypes of a

yeast strain deleted for the single yeast CLC Gef1

(33) suggested that these

plant CLC proteins function in anion transport but could not reveal details of

their biophysical properties. We report here the first functional expression

of a plant CLC in animal cells. Expression of wild-type (WT) and mutant

AtClC-a in Xenopus oocytes indicate a general role of gating and

proton glutamate residues in anion/proton coupling across different isoforms

and species. We identified a proline in the CLC signature sequence of AtClC-a

that plays a crucial role in

exchange. Mutating it to serine, the residue present in mammalian CLC proteins

at this position, rendered AtClC-a Cl–/H+ exchange

as efficient as

exchange. Mutating it to serine, the residue present in mammalian CLC proteins

at this position, rendered AtClC-a Cl–/H+ exchange

as efficient as

exchange. Conversely, changing the corresponding serine of ClC-5 to proline

converted it into an efficient

exchange. Conversely, changing the corresponding serine of ClC-5 to proline

converted it into an efficient

exchanger. When proline replaced the critical serine in Torpedo

ClC-0, the relative

exchanger. When proline replaced the critical serine in Torpedo

ClC-0, the relative  conductance of

this model Cl– channel was drastically increased, and

“fast” protopore gating was slowed.

conductance of

this model Cl– channel was drastically increased, and

“fast” protopore gating was slowed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Biology—cDNAs of A. thaliana AtClC-a (12), rat ClC-5 (34), and Torpedo marmorata ClC-0 (35) were cloned into the pTLN (36) expression vector. Mutations were generated by recombinant PCR and confirmed by sequencing. Capped cRNA was transcribed from linearized plasmids using the Ambion mMESSAGE mMACHINE kit (SP6 RNA polymerase for pTLN) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Expression in Xenopus Oocyte and Two-electrode Voltage-Clamp Studies—Pieces of ovary were obtained by surgery from deeply anesthetized (0.1% tricaine; Sigma) pigmented or albino Xenopus laevis frogs. Oocytes were prepared by manual dissection and collagenase A (Roche Applied Science) digestion. 23 ng (ClC-5), 46–50 ng (AtClC-a), or 1–3 ng (ClC-0) of cRNA were injected into oocytes. Oocytes were kept in ND96 solution (containing 96 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl .2, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm HEPES, pH 7.5) at 17 °C for 1–2 days (ClC-0), 3–4 days (ClC-5), or for 5–6 days (AtClC-a). Two-electrode voltage clamping was performed at room temperature (20–24 °C) using a TEC10 amplifier (npi Electronics, Tamm, Germany) and pClamp9 software (Molecular Devices). The standard bath solution contained 96 mm NaCl, 2 mm K+ gluconate, 5 mm Ca2+ d-gluconate, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 5 mm HEPES, pH 7.5 (or MES for buffering to pH 5.5 or 6.5; Tris for pH 8.5). For some experiments, NaCl was substituted with equal amounts of either NaNO3, NaBr, or NaI. Ag/AgCl electrodes and 3 m KCl agar bridges were used as reference and bath electrodes, respectively.

Measurement of Relative Intracellular pH Changes Using the “Fluorocyte” Device—Proton transport was measured semiquantitatively by monitoring intracellular fluorescence signal changes using the Fluorocyte device (21). Briefly, 23 nl of saturated aqueous solution of the pH indicator BCECF (Molecular Probes) were injected into oocytes 10–30 min before measurements. Oocytes were placed over a hole 0.8 mm in diameter, through which BCECF fluorescence changes were measured in response to pulse trains, which served to reduce the possible activation of endogenous oocyte currents. Starting from a holding voltage of –60 mV, depolarizing pulse trains clamped oocytes to +90 mV for 400 ms and –60 mV for 100 ms, whereas hyperpolarizing pulse trains started from –30 mV and clamped to –160 mV for 400 ms and to –30 mV for 100 ms. BCECF fluorescence was measured with a photodiode and digitally Bessel-filtered at 0.3 Hz. These nonratiometric measurements generally show drifts owed to bleaching or intracellular dye distribution (21) but allow for sensitive measurements of pH changes upon changes in voltage or external ion composition.

RESULTS

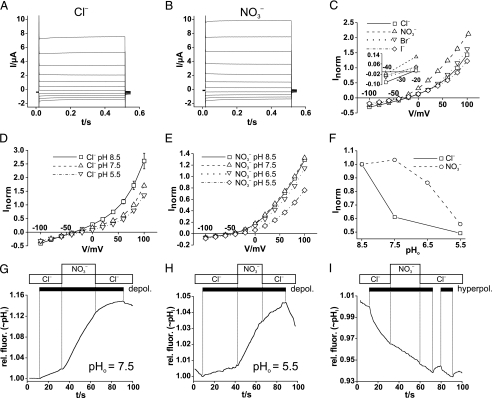

Previous attempts to functionally express plant CLC proteins in animal

cells proved unsuccessful

(12). However, when

Xenopus oocytes were measured 5 or more days after injecting AtClC-a

cRNA, currents well above background levels were observed in two-electrode

voltage-clamp experiments (Fig.

1). These outwardly rectifying currents were roughly 30% larger

when extracellular chloride was replaced by nitrate

(Fig. 1, A–C),

smaller with extracellular iodide, and nearly unchanged with a replacement by

bromide (Fig. 1C).

Reversal potentials indicated that the apparent anion permeability was larger

for

(Fig. 1, A–C),

smaller with extracellular iodide, and nearly unchanged with a replacement by

bromide (Fig. 1C).

Reversal potentials indicated that the apparent anion permeability was larger

for  than for the other anions

tested. It should be noted that for CLC exchangers, the observed apparent

permeabilities and conductances represent those of coupled anion/proton

exchange rather than diffusive anion transport. Contrasting with the slow

activation of currents by depolarization observed in plant vacuoles

(16), heterologously expressed

AtClC-a currents almost totally lacked time-dependent relaxations

(Fig. 1, A and

B). Like currents elicited by ClC-4 or -5

(26), AtClC-a currents were

reduced by acidic extracellular pH (pHo)

(Fig. 1, D–F).

With extracellular

than for the other anions

tested. It should be noted that for CLC exchangers, the observed apparent

permeabilities and conductances represent those of coupled anion/proton

exchange rather than diffusive anion transport. Contrasting with the slow

activation of currents by depolarization observed in plant vacuoles

(16), heterologously expressed

AtClC-a currents almost totally lacked time-dependent relaxations

(Fig. 1, A and

B). Like currents elicited by ClC-4 or -5

(26), AtClC-a currents were

reduced by acidic extracellular pH (pHo)

(Fig. 1, D–F).

With extracellular  , the

extracellular pH had to be more acidic to obtain the same degree of current

decrease as with Cl– (Fig.

1F).

, the

extracellular pH had to be more acidic to obtain the same degree of current

decrease as with Cl– (Fig.

1F).

FIGURE 1.

Electrophysiological characterization of AtClC-a in Xenopus

oocytes. A and B, voltage-clamp traces of

oocyte-expressed AtClC-a in either Cl–-containing

(A) or  -containing

(B) solutions. From a holding potential of –30 mV, the oocyte

was clamped in 20-mV steps to voltages between –100 and +100 mV for 500

ms. C, steady-state I/V curves of AtClC-a with

different extracellular anions. Currents were normalized for individual

oocytes to a current at +80 mV in Cl– solution (with a mean

value of 3.38 ± 0.40 μA). AtClC-a has a

-containing

(B) solutions. From a holding potential of –30 mV, the oocyte

was clamped in 20-mV steps to voltages between –100 and +100 mV for 500

ms. C, steady-state I/V curves of AtClC-a with

different extracellular anions. Currents were normalized for individual

oocytes to a current at +80 mV in Cl– solution (with a mean

value of 3.38 ± 0.40 μA). AtClC-a has a

conductance sequence (mean values from 13 oocytes from four batches; error

bars, S.E.). Inset, higher magnification of the

I/V curve to show reversal potentials. D and

E, steady-state I/V curves of AtClC-a at different

values of extracellular pH (pHo) in

Cl–-containing (D) or

conductance sequence (mean values from 13 oocytes from four batches; error

bars, S.E.). Inset, higher magnification of the

I/V curve to show reversal potentials. D and

E, steady-state I/V curves of AtClC-a at different

values of extracellular pH (pHo) in

Cl–-containing (D) or

-containing (E) solutions.

The voltage-clamp protocol was performed as in A and B.

Currents were normalized for individual oocytes to the respective current at

+80 mV at pH 7.5 (five oocytes for each data point; error bars,

S.E.). F, currents at +80 mV as a function of pHo

with extracellular Cl– (□) or

-containing (E) solutions.

The voltage-clamp protocol was performed as in A and B.

Currents were normalized for individual oocytes to the respective current at

+80 mV at pH 7.5 (five oocytes for each data point; error bars,

S.E.). F, currents at +80 mV as a function of pHo

with extracellular Cl– (□) or

(○). For each curve, currents

were normalized to currents at pHo 8.5.

G–I, AtClC-a mediated, voltage-driven H+ transport

assayed by pH-sensitive BCECF fluorescence using the Fluorocyte system

(21). Proton transport was

stimulated by trains (black bars) of 400-ms long voltage pulses,

either to +90 mV (depolarization) in (G and H) or to

–160 mV (hyperpolarization) in I in the presence of either

extracellular Cl– or

(○). For each curve, currents

were normalized to currents at pHo 8.5.

G–I, AtClC-a mediated, voltage-driven H+ transport

assayed by pH-sensitive BCECF fluorescence using the Fluorocyte system

(21). Proton transport was

stimulated by trains (black bars) of 400-ms long voltage pulses,

either to +90 mV (depolarization) in (G and H) or to

–160 mV (hyperpolarization) in I in the presence of either

extracellular Cl– or

(shown in boxes above).

Depolarizing pulses elicited intracellular alkalinization both with

pHo 7.5 (G) and pHo 5.5, when

proton transport occurs against a gradient (H). Extracellular

(shown in boxes above).

Depolarizing pulses elicited intracellular alkalinization both with

pHo 7.5 (G) and pHo 5.5, when

proton transport occurs against a gradient (H). Extracellular

accelerates depolarization (depol.)-driven alkalinization (G

and H) but not hyperpolarization (hyperpol.)-induced

acidification (I, pHo 7.5). Only changes in

relative fluorescence (rel. fluor.) induced by changes in voltage or

external anions are relevant because of the drift inherent to the Fluorocyte

technique (21). Results as in

G–I were obtained in 26, 6, and 7 independent experiments,

respectively.

accelerates depolarization (depol.)-driven alkalinization (G

and H) but not hyperpolarization (hyperpol.)-induced

acidification (I, pHo 7.5). Only changes in

relative fluorescence (rel. fluor.) induced by changes in voltage or

external anions are relevant because of the drift inherent to the Fluorocyte

technique (21). Results as in

G–I were obtained in 26, 6, and 7 independent experiments,

respectively.

We next explored proton transport of AtClC-a by measuring

semiquantitatively the pHi of voltage-clamped oocytes

using the Fluorocyte system

(21). Net ion transport was

elicited by strongly depolarizing oocytes to +90 mV. Because prolonged strong

depolarization can elicit endogenous transport processes in oocytes, trains of

depolarizing pulses were used instead

(20,

21). An inside-positive

voltage should lead to anion influx and proton efflux through electrogenic

anion/proton exchangers. Pulsing AtClC-a-expressing oocytes to positive

voltages indeed induced intracellular alkalinization

(Fig. 1G).

Importantly, alkalinization was also observed when protons were extruded

against their electrochemical potential (at pHo 5.5),

suggesting that their transport is driven by the coupled anion entry

(Fig. 1H). Under

either condition (pHo 7.5 or 5.5), alkalinization occurred

more rapidly with extracellular  than with Cl–. This shows that AtClC-a more efficiently

mediates

than with Cl–. This shows that AtClC-a more efficiently

mediates  exchange than Cl–/H+ exchange, a finding

compatible with its role in accumulating

exchange than Cl–/H+ exchange, a finding

compatible with its role in accumulating

in plant vacuoles

(16,

37). In contrast with ClC-4

and -5 (26), AtClC-a mediates

robust currents also at negative voltages

(Fig. 1, A–E).

Accordingly, and in contrast to ClC-5 (see

Fig. 5H), AtClC-a

mediated proton influx when oocytes were pulsed to negative voltages

(–160 mV) (Fig.

1I). Substituting extracellular Cl– by

in plant vacuoles

(16,

37). In contrast with ClC-4

and -5 (26), AtClC-a mediates

robust currents also at negative voltages

(Fig. 1, A–E).

Accordingly, and in contrast to ClC-5 (see

Fig. 5H), AtClC-a

mediated proton influx when oocytes were pulsed to negative voltages

(–160 mV) (Fig.

1I). Substituting extracellular Cl– by

failed to influence the rate of

acidification because proton influx is coupled to an efflux of anions from the

interior of oocytes.

failed to influence the rate of

acidification because proton influx is coupled to an efflux of anions from the

interior of oocytes.

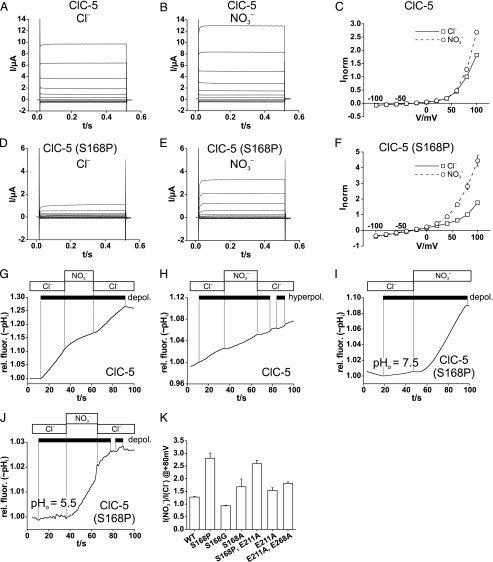

FIGURE 5.

Effect of the S168P mutation on ClC-5 conductance and proton

coupling. A and B, shown are the typical two-electrode

voltage-clamp traces of oocyte-expressed ClC-5 in

Cl–-containing (A) or

-containing (B) solutions.

C, shown are the steady-state I/V curves from such

experiments (averaged from 19 oocytes from seven batches; normalized for each

oocyte to current in Cl– at +80 mV, with mean current of 3.01

± 0.35 μA). D–F, shown are the current properties of

the S168P mutant measured as in A–C. The data in F

show means from 23 oocytes from five batches, normalized to I in

Cl– at +80 mV, with mean I of 0.79 ± 0.17

μA. Voltage-clamp protocols were performed in A–F as

described in the legend to Fig. 1.

G, shown is an example of less efficient depolarization

(depol.)-induced alkalinization by ClC-5 in the presence of

-containing (B) solutions.

C, shown are the steady-state I/V curves from such

experiments (averaged from 19 oocytes from seven batches; normalized for each

oocyte to current in Cl– at +80 mV, with mean current of 3.01

± 0.35 μA). D–F, shown are the current properties of

the S168P mutant measured as in A–C. The data in F

show means from 23 oocytes from five batches, normalized to I in

Cl– at +80 mV, with mean I of 0.79 ± 0.17

μA. Voltage-clamp protocols were performed in A–F as

described in the legend to Fig. 1.

G, shown is an example of less efficient depolarization

(depol.)-induced alkalinization by ClC-5 in the presence of

compared with Cl–.

Similar results were obtained in 17 experiments. H, hyperpolarization

(hyperpol.) does not elicit intracellular acidification with ClC-5,

in contrast to AtClC-a (Fig.

1I). Similar results were obtained in 13 experiments.

I and J, shown is the drastically increased

compared with Cl–.

Similar results were obtained in 17 experiments. H, hyperpolarization

(hyperpol.) does not elicit intracellular acidification with ClC-5,

in contrast to AtClC-a (Fig.

1I). Similar results were obtained in 13 experiments.

I and J, shown is the drastically increased

exchange

activity with ClC-5 (S168P), as shown by Fluorocyte with

pHo 7.5 (I) or with pHo 5.5

(transport against gradient) (J), resembling in this respect AtClC-a

(Fig. 1G and

H). Similar results were obtained in 21 (I) and

eight (J) experiments. K, shown is a ratio of currents at

+80 mV measured with extracellular

exchange

activity with ClC-5 (S168P), as shown by Fluorocyte with

pHo 7.5 (I) or with pHo 5.5

(transport against gradient) (J), resembling in this respect AtClC-a

(Fig. 1G and

H). Similar results were obtained in 21 (I) and

eight (J) experiments. K, shown is a ratio of currents at

+80 mV measured with extracellular  and Cl–, respectively, for ClC-5 and several mutants,

determined as in Fig.

4F. The number of oocytes used for averages are as

follows: ClC-5, 19; ClC-5(S168P), 23; ClC-5(S168G), 17; ClC-5(S168A), 2;

ClC-5(S168P,E211A), 6; ClC-5(E211A), 10; ClC-5(E211A,E268A), 34). Error

bars indicate S.E. rel. fluor., relative fluorescence.

and Cl–, respectively, for ClC-5 and several mutants,

determined as in Fig.

4F. The number of oocytes used for averages are as

follows: ClC-5, 19; ClC-5(S168P), 23; ClC-5(S168G), 17; ClC-5(S168A), 2;

ClC-5(S168P,E211A), 6; ClC-5(E211A), 10; ClC-5(E211A,E268A), 34). Error

bars indicate S.E. rel. fluor., relative fluorescence.

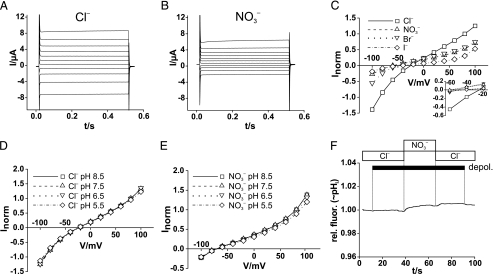

In EcClC-1 and ClC-4 and -5, a certain gating glutamate is important for

coupling chloride fluxes to proton countertransport

(17,

19,

20). In crystals of the

bacterial protein, the negatively charged side chain of this glutamate seems

to block the permeation pathway

(22,

23). Mutating this glutamate

to alanine in ClC-4 and -5 not only leads to flux uncoupling but also

abolishes the strong outward rectification of either transporter

(26). Likewise, currents of

the E203A mutant lost their outward rectification

(Fig. 2). Rather than being

linear and again similar to the analogous mutants of ClC-4 and -5

(19,

20,

26), currents showed slight

outward rectification at positive voltages and slight inward rectification at

negative voltages. Contrasting with the moderate changes in ion selectivity

observed with such mutations in ClC-4 and -5

(26), the E203A mutation

drastically altered the anion selectivity of AtClC-a. Whereas reversal

potentials indicated that the mutant remained more permeable for

than for Cl–

(Fig. 2C,

inset), its conductance was now reduced rather than increased when

extracellular Cl– was replaced by

than for Cl–

(Fig. 2C,

inset), its conductance was now reduced rather than increased when

extracellular Cl– was replaced by

(Fig. 2, A–C;

see Fig. 4F). With

either external anion, currents were insensitive to changes in

pHo (Fig. 2, D

and E), and trains of depolarizing pulses failed to

change pHi (Fig.

2F). Hence, the E203A mutant displayed uncoupled anion

transport and drastically reduced conductance in the presence of

(Fig. 2, A–C;

see Fig. 4F). With

either external anion, currents were insensitive to changes in

pHo (Fig. 2, D

and E), and trains of depolarizing pulses failed to

change pHi (Fig.

2F). Hence, the E203A mutant displayed uncoupled anion

transport and drastically reduced conductance in the presence of

.

.

FIGURE 2.

Impact of gating glutamate mutant E203A on AtClC-a properties.

A and B, voltage-clamp traces of oocytes expressing the

E203A mutant of AtClC-a with extracellular Cl– (A)

or  (B) using the pulse

protocol of Fig. 1 (A and

B). C, steady-state I/V curves

of AtClC-a(E203A) with different extracellular anions reveal a changed

conductance sequence of

(B) using the pulse

protocol of Fig. 1 (A and

B). C, steady-state I/V curves

of AtClC-a(E203A) with different extracellular anions reveal a changed

conductance sequence of

(mean of 19 oocytes; error bars, S.E.). Currents were normalized to

current in Cl– at + 80 mV (with mean current of 3.05 ±

0.22 μA). Inset, higher magnification of the I/V

curve to show reversal potentials. D and E, currents of

AtClC-a(E203A) are insensitive to pHo, both in the

presence of extracellular Cl– (D) or

(mean of 19 oocytes; error bars, S.E.). Currents were normalized to

current in Cl– at + 80 mV (with mean current of 3.05 ±

0.22 μA). Inset, higher magnification of the I/V

curve to show reversal potentials. D and E, currents of

AtClC-a(E203A) are insensitive to pHo, both in the

presence of extracellular Cl– (D) or

(E). The number of oocytes

is 10 for D and 14 for E (error bars, S.E.).

F, lack of depolarization (depol.)-induced alkalinization

with the E203A mutant. 25 independent experiments gave similar results.

rel. fluor., relative fluorescence.

(E). The number of oocytes

is 10 for D and 14 for E (error bars, S.E.).

F, lack of depolarization (depol.)-induced alkalinization

with the E203A mutant. 25 independent experiments gave similar results.

rel. fluor., relative fluorescence.

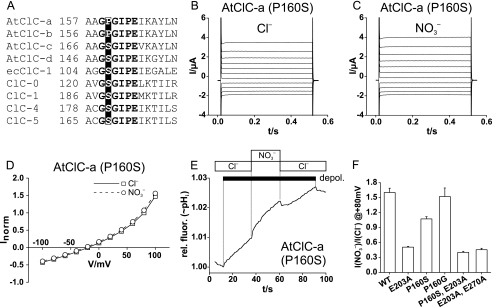

FIGURE 4.

A critical role of proline residue in AtClC-a in determining anion

selectivity. A, shown is the sequence alignment of several CLC

proteins in the region of the GSGIPE signature sequence. E. coli

EcClC-1 as well as all animal CLC proteins have a serine between the two

glycines. It is replaced by proline in plant AtClC-a and -b, but not in

AtClC-c and -d. B and C, shown are typical two-electrode

voltage-clamp traces of the AtClC-a P160S mutant in Xenopus oocytes

with external Cl– (B) or

(C) (voltage protocol as

in Fig. 1). D, the

current-voltage relationship of the mutant appears to be identical in

extracellular Cl– and

(C) (voltage protocol as

in Fig. 1). D, the

current-voltage relationship of the mutant appears to be identical in

extracellular Cl– and

(mean of nine oocytes from six

batches each). Currents were normalized to those in Cl– at

+80 mV (where mean current was 2.33 ± 0.44 μA). E,

depolarization (depol.)-induced H+ transport of AtClC-a

(P160S) is similarly effective with extracellular Cl– or

(mean of nine oocytes from six

batches each). Currents were normalized to those in Cl– at

+80 mV (where mean current was 2.33 ± 0.44 μA). E,

depolarization (depol.)-induced H+ transport of AtClC-a

(P160S) is similarly effective with extracellular Cl– or

, in stark contrast to the WT

(Fig. 1G,H). Similar

results were obtained in 14 experiments (14 ooyctes from six batches).

F, shown is the ratio of currents at + 80 mV in the presence of

, in stark contrast to the WT

(Fig. 1G,H). Similar

results were obtained in 14 experiments (14 ooyctes from six batches).

F, shown is the ratio of currents at + 80 mV in the presence of

and Cl– for

AtClC-a and several mutants, respectively. The number of oocytes is as

follows: AtClC-a, 25; AtClC-a(E203A), 24; AtClC-a(P160S), 9; AtClC-a(P160G),

5; AtClC-a(P160S,E203A), 4; and AtClC-a(E203A,E270A), 9. rel. fluor.,

relative fluorescence.

and Cl– for

AtClC-a and several mutants, respectively. The number of oocytes is as

follows: AtClC-a, 25; AtClC-a(E203A), 24; AtClC-a(P160S), 9; AtClC-a(P160G),

5; AtClC-a(P160S,E203A), 4; and AtClC-a(E203A,E270A), 9. rel. fluor.,

relative fluorescence.

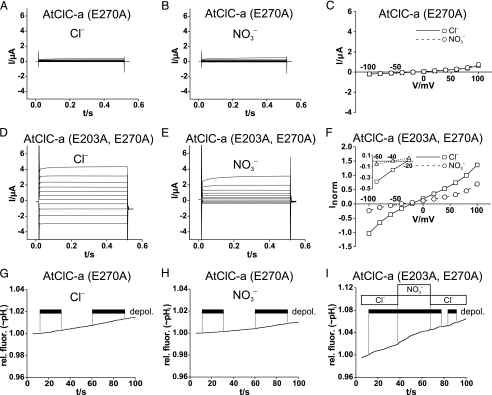

We next studied the AtClC-a mutant E270A, which is equivalent to the proton glutamate mutations of EcClC-1 (27) and ClC-4 and -5 (Fig. 3) (21). Neither currents (Fig. 3, A–C) nor depolarization-induced H+ transport (Fig. 3, G and H) were different from background levels with this mutant. However, when combined with the uncoupling E203A mutation in the gating glutamate, the AtClC-a(E203A,E270A) double mutant gave currents that resembled those of the single E203A mutant (Fig. 3, D–F). Like AtClC-a(E203A), the double mutant failed to transport protons in response to depolarization (Fig. 3I).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of proton glutamate E270A mutation alone and in combination with

the uncoupling E203A mutation on AtClC-a transport. A and

B, voltage-clamp traces of oocyte-expressed AtClC-a(E270A) in either

Cl–-containing (A) or

-containing (B) solutions

are not different from those from uninjected control oocytes (not shown).

C, steady-state I/V curves of AtClC-a(E270A) are

not different from controls (10 oocytes per data point). Currents were

normalized to current at +80 mV in Cl–. D and

E, currents of the AtClC-a(E203A,E270A) double mutant are larger with

Cl– (D) than with

-containing (B) solutions

are not different from those from uninjected control oocytes (not shown).

C, steady-state I/V curves of AtClC-a(E270A) are

not different from controls (10 oocytes per data point). Currents were

normalized to current at +80 mV in Cl–. D and

E, currents of the AtClC-a(E203A,E270A) double mutant are larger with

Cl– (D) than with

(E). These results also

suggest that the failure to observe AtClC-a(E270A) currents is not due to an

absence from the plasma membrane. F, I/V curves of

currents averaged from nine oocytes from four batches are shown. Currents were

normalized to those in Cl– at 80 mV (with mean current of

1.86 ± 0.47 μA). Inset, a higher magnification of the

I/V curve shows reversal potentials. G and

H, shown is a lack of detectable depolarization

(depol.)-induced alkalinization with AtClC-a(E270A) in the presence

of Cl– (G) or

(E). These results also

suggest that the failure to observe AtClC-a(E270A) currents is not due to an

absence from the plasma membrane. F, I/V curves of

currents averaged from nine oocytes from four batches are shown. Currents were

normalized to those in Cl– at 80 mV (with mean current of

1.86 ± 0.47 μA). Inset, a higher magnification of the

I/V curve shows reversal potentials. G and

H, shown is a lack of detectable depolarization

(depol.)-induced alkalinization with AtClC-a(E270A) in the presence

of Cl– (G) or

(H). Similar negative

results were obtained with nine oocytes (from four batches) for G and

H. I, shown is a lack of depolarization-induced proton

transport with AtClC-a(E203A,E270A). Similar results were obtained with five

oocytes from three batches. Voltage-clamp protocols are identical to those

described in the legend to Fig.

1. rel. fluor., relative fluorescence.

(H). Similar negative

results were obtained with nine oocytes (from four batches) for G and

H. I, shown is a lack of depolarization-induced proton

transport with AtClC-a(E203A,E270A). Similar results were obtained with five

oocytes from three batches. Voltage-clamp protocols are identical to those

described in the legend to Fig.

1. rel. fluor., relative fluorescence.

Two main biophysical differences between AtClC-a and ClC-4 and -5 are (i)

the much stronger rectification of the mammalian isoforms and (ii) their

partial uncoupling of anion from proton transport in the case of nitrate. We

therefore searched for differences in their primary sequences that may

underlie these differences. A salient feature is the presence of a proline in

a stretch of highly conserved “signature” sequences

(Fig. 4A). In AtClC-a,

this proline replaces a serine that is found at this position in most CLC

proteins. The importance of that serine was recognized early on

(25). Even the conservative

exchange of this serine for threonine (S123T) changed the ion selectivity,

single-channel conductance, and open-channel rectification of the ClC-0

Cl– channel

(25). In the crystal of

EcClC-1, the equivalent serine (Ser-107) participates in the coordination of

Cl– in the central binding site

(22). Mutating this particular

proline in AtClC-a to the “consensus” serine (P160S) resulted in

less rectifying currents (Fig. 4,

B–D), indicating that the difference in

rectification between WT AtClC-a and ClC-5 proteins is not determined by the

residue at this position. Importantly, both the apparent permeability (from

reversal potentials) and conductance no longer differed measurably between

and Cl– solutions

(Fig. 4, B–D).

Furthermore, the mutant performed Cl–/H+- and

and Cl– solutions

(Fig. 4, B–D).

Furthermore, the mutant performed Cl–/H+- and

exchange

with similar efficiencies (Fig.

4E). When this proline was mutated to glycine (P160G),

the ratio of currents measured in the presence of extracellular

exchange

with similar efficiencies (Fig.

4E). When this proline was mutated to glycine (P160G),

the ratio of currents measured in the presence of extracellular

to those measured with extracellular Cl–

(I(Cl–)) resembled the ratio

to those measured with extracellular Cl–

(I(Cl–)) resembled the ratio

of WT AtClC-a (Fig.

4F), with which it also shares the higher efficiency of

of WT AtClC-a (Fig.

4F), with which it also shares the higher efficiency of

exchange

as compared with Cl–/H+ exchange (data not shown).

When the P160S mutation was combined with the uncoupling mutation in the

gating glutamate, the resulting double mutant AtClC-a(P160S,E203A) displayed a

low

exchange

as compared with Cl–/H+ exchange (data not shown).

When the P160S mutation was combined with the uncoupling mutation in the

gating glutamate, the resulting double mutant AtClC-a(P160S,E203A) displayed a

low

ratio that was similar to the single E203A mutant

(Fig. 4F) and had lost

proton coupling (data not shown).

ratio that was similar to the single E203A mutant

(Fig. 4F) and had lost

proton coupling (data not shown).

The above experiments indicate that the presence of proline in the CLC

signature sequence may be responsible for the efficient

coupling

of AtClC-a. We asked next whether changing the equivalent serine to proline in

ClC-5 would increase its efficiency of

coupling

of AtClC-a. We asked next whether changing the equivalent serine to proline in

ClC-5 would increase its efficiency of

coupling. In the presence of extracellular chloride, currents from the

ClC-5(S168P) mutant (Fig.

5D) were much smaller (∼5–10-fold) than WT

currents (Fig. 5A).

They increased ∼3-fold in the presence of extracellular

coupling. In the presence of extracellular chloride, currents from the

ClC-5(S168P) mutant (Fig.

5D) were much smaller (∼5–10-fold) than WT

currents (Fig. 5A).

They increased ∼3-fold in the presence of extracellular

(Fig. 5E), coinciding

with the recent parallel work by Zifarelli and Pusch

(38). Whereas currents of WT

ClC-5 are also larger with

(Fig. 5E), coinciding

with the recent parallel work by Zifarelli and Pusch

(38). Whereas currents of WT

ClC-5 are also larger with  than

with Cl– (Fig. 5,

A–C), the

than

with Cl– (Fig. 5,

A–C), the

ratio is markedly increased in the mutant

(Fig. 5, D–F and

K). The strong rectification of ClC-5 currents is not

appreciably affected by the S168P mutation

(Fig. 5, A–F),

but currents showed somewhat more pronounced and slower “gating”

relaxations when jumping to positive voltages. In contrast to WT ClC-5

(Fig. 5G), trains of

depolarizing pulses alkalinized the oocyte interior much more rapidly when

extracellular Cl– was replaced by

ratio is markedly increased in the mutant

(Fig. 5, D–F and

K). The strong rectification of ClC-5 currents is not

appreciably affected by the S168P mutation

(Fig. 5, A–F),

but currents showed somewhat more pronounced and slower “gating”

relaxations when jumping to positive voltages. In contrast to WT ClC-5

(Fig. 5G), trains of

depolarizing pulses alkalinized the oocyte interior much more rapidly when

extracellular Cl– was replaced by

(Fig. 5I).

ClC-5(S168P) transported H+ efficiently against its electrochemical

gradient (with pHo 5.5) using

(Fig. 5I).

ClC-5(S168P) transported H+ efficiently against its electrochemical

gradient (with pHo 5.5) using

as a driving ion

(Fig. 5J). When

Ser-168 of ClC-5 was replaced by glycine or alanine, only the S168A mutation

yielded a moderately higher

as a driving ion

(Fig. 5J). When

Ser-168 of ClC-5 was replaced by glycine or alanine, only the S168A mutation

yielded a moderately higher

current ratio (Fig.

5K). This contrasts with AtClC-a, where glycine could

substitute for proline without compromising its

current ratio (Fig.

5K). This contrasts with AtClC-a, where glycine could

substitute for proline without compromising its

ratio (Fig. 4K) and

its efficient

ratio (Fig. 4K) and

its efficient

exchange. Hence, a single mutation that replaced a serine by proline, which is

found at that position in AtClC-a, strongly increased the preference of ClC-5

for

exchange. Hence, a single mutation that replaced a serine by proline, which is

found at that position in AtClC-a, strongly increased the preference of ClC-5

for  and converted it into an

efficient

and converted it into an

efficient

exchanger.

exchanger.

The uncoupling E211A mutation in the ClC-5 gating glutamate slightly

increased its relative nitrate conductance

(Fig. 5K), whereas the

equivalent mutation in AtClC-a quite drastically lowered its nitrate

versus chloride conductance (Fig.

4F). Exchanging serine 168 for proline in the uncoupled

ClC-5 mutant increased relative conductance in the presence of

(Fig. 5K), whereas a

similar exchange in the uncoupled AtClC-a mutant failed to change the

(Fig. 5K), whereas a

similar exchange in the uncoupled AtClC-a mutant failed to change the

current ratio (Fig.

4F).

current ratio (Fig.

4F).

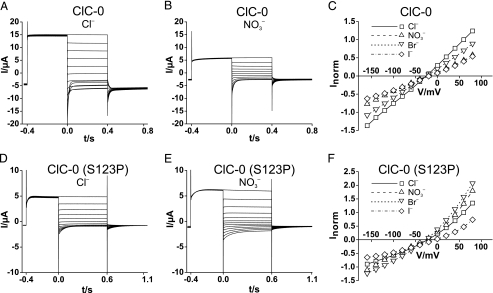

We finally asked whether also CLC Cl– channels gain higher

conductance with an equivalent

mutation and used the Torpedo Cl– channel ClC-0

(35) as a widely used model

channel. When expressed in Xenopus oocytes, the S123P mutant gave

robust currents that were, however, ∼4-fold smaller than those from WT

ClC-0 (Fig. 6, A and

D). Whereas the WT channel conducts Cl–

much better than nitrate (Fig. 6,

A–C),

conductance with an equivalent

mutation and used the Torpedo Cl– channel ClC-0

(35) as a widely used model

channel. When expressed in Xenopus oocytes, the S123P mutant gave

robust currents that were, however, ∼4-fold smaller than those from WT

ClC-0 (Fig. 6, A and

D). Whereas the WT channel conducts Cl–

much better than nitrate (Fig. 6,

A–C),  conductance was larger than Cl– conductance in the S123P

mutant (Fig. 6,

D–F). The selectivity was also changed for other

anions, as evident in the large increase of Br– conductance

(Fig. 6F). In

addition, the mutation drastically slowed the fast protopore gate (as evident

from current relaxations after stepping to negative voltages,

Fig. 6, A and

D) and introduced an open-pore outward rectification

(Fig. 6, C and

F). The concomitant change of pore and gating properties

reflects the tight coupling of permeation and gating in CLC

Cl– channels

(39).

conductance was larger than Cl– conductance in the S123P

mutant (Fig. 6,

D–F). The selectivity was also changed for other

anions, as evident in the large increase of Br– conductance

(Fig. 6F). In

addition, the mutation drastically slowed the fast protopore gate (as evident

from current relaxations after stepping to negative voltages,

Fig. 6, A and

D) and introduced an open-pore outward rectification

(Fig. 6, C and

F). The concomitant change of pore and gating properties

reflects the tight coupling of permeation and gating in CLC

Cl– channels

(39).

FIGURE 6.

Modification of ClC-0 Cl– channel currents by the S123P

mutation. A and B, typical voltage-clamp traces of an

oocyte expressing WT ClC-0 and measured in Cl– saline

(A) and  saline

(B). After ∼8 s at –120 mV (to activate the slow

hyperpolarization-activated gate of ClC-0), the oocytes were clamped

consecutively for 1 s to –120 mV (to keep the “slow” common

gate open), 400 ms to +80 mV to open the fast protopore gate. At t =

0, they were clamped (for 400 ms) to test voltages between +80 and –160

mV in steps of 20 mV, followed by a constant pulse to –100 mV for 400

ms. C, normalized I/V curves of WT ClC-0 in the

presence of different extracellular anions. Values were obtained from

exponential fits to t = 0 and represent open channel currents because

both slow and fast gates were opened by hyperpolarizing and depolarizing

prepulses, respectively. Averaged currents from five oocytes of two batches

were normalized for each individual oocyte to the current in

Cl– at V =+60 mV, where mean I was 13.8

± 2.2 μA. D and E, typical traces from an oocyte

expressing the S123P mutant of ClC-0. Voltage-clamp protocol was similar to

A, but the test voltages were applied for 600 ms, followed by a

500-ms pulse to –100 mV. F, normalized open-channel

I/V for the mutant obtained as in C. Means are from

seven oocytes of two batches (normalized to current in Cl– at

+60 mV, where mean I was 4.41 ± 0.90 μA).

saline

(B). After ∼8 s at –120 mV (to activate the slow

hyperpolarization-activated gate of ClC-0), the oocytes were clamped

consecutively for 1 s to –120 mV (to keep the “slow” common

gate open), 400 ms to +80 mV to open the fast protopore gate. At t =

0, they were clamped (for 400 ms) to test voltages between +80 and –160

mV in steps of 20 mV, followed by a constant pulse to –100 mV for 400

ms. C, normalized I/V curves of WT ClC-0 in the

presence of different extracellular anions. Values were obtained from

exponential fits to t = 0 and represent open channel currents because

both slow and fast gates were opened by hyperpolarizing and depolarizing

prepulses, respectively. Averaged currents from five oocytes of two batches

were normalized for each individual oocyte to the current in

Cl– at V =+60 mV, where mean I was 13.8

± 2.2 μA. D and E, typical traces from an oocyte

expressing the S123P mutant of ClC-0. Voltage-clamp protocol was similar to

A, but the test voltages were applied for 600 ms, followed by a

500-ms pulse to –100 mV. F, normalized open-channel

I/V for the mutant obtained as in C. Means are from

seven oocytes of two batches (normalized to current in Cl– at

+60 mV, where mean I was 4.41 ± 0.90 μA).

DISCUSSION

We have achieved for the first time the functional expression of a plant

CLC transporter in animal cells. This enabled us to study the currents and

proton transport of wild-type and mutant AtClC-a, a

exchanger that serves to accumulate the plant nutrient

exchanger that serves to accumulate the plant nutrient

in vacuoles

(16,

37). We have studied the role

in AtClC-a of key glutamate residues that are important for anion/proton

coupling in bacterial and mammalian CLC isoforms and have shown that a

proline-serine exchange in a highly conserved stretch (GSGIPE, the “CLC

signature sequence”) strongly affects nitrate/proton transport in

AtClC-a and ClC-5.

in vacuoles

(16,

37). We have studied the role

in AtClC-a of key glutamate residues that are important for anion/proton

coupling in bacterial and mammalian CLC isoforms and have shown that a

proline-serine exchange in a highly conserved stretch (GSGIPE, the “CLC

signature sequence”) strongly affects nitrate/proton transport in

AtClC-a and ClC-5.

In our previous study, we were unable to detect plasma membrane currents in Xenopus oocytes injected with AtClC-a–AtClC-d (12). Currents reported previously for the oocyte-expressed tobacco CLC NtClC (40) resemble endogenous oocyte currents (12). Hence, the present study may represent the first functional characterization of plant CLC proteins in animal cells. This renders AtClC-a accessible to structure-function analysis by mutagenesis. The most important technical differences from our previous study (12) are the injection of about twice the amount of RNA and a longer time of expression. Whereas we previously measured oocytes 3 days after injection, we now found that AtClC-a currents rise above background levels only after 5 days. Because AtClC-a is physiologically expressed in the plant vacuole (16), the presence of plasma membrane currents may indicate a misrouting of AtClC-a in overexpressing oocytes.

The currents reported here for oocyte-expressed AtClC-a resemble in many

aspects the currents from Arabidopsis vacuoles that were studied by

patch clamp in the whole vacuole configuration and that were absent in strains

with AtClC-a gene deletions

(16). Both currents showed

similar rectification and proton coupling. However, there are also conspicuous

differences. When studied under asymmetric ionic conditions with

in the pipette (vacuole) and

Cl– in the bath (cytosol), which resembles our oocyte

experiments with external

in the pipette (vacuole) and

Cl– in the bath (cytosol), which resembles our oocyte

experiments with external  , vacuolar

currents showed prominent, depolarization-induced activation that remained

incomplete after several seconds

(16). Such current relaxations

were clearly absent from our recordings. Moreover, whereas our currents

increased with extracellular

, vacuolar

currents showed prominent, depolarization-induced activation that remained

incomplete after several seconds

(16). Such current relaxations

were clearly absent from our recordings. Moreover, whereas our currents

increased with extracellular  only

∼1.6-fold, this increase was much more drastic with vacuolar currents

(16). Several explanations may

be invoked. Current properties may be influenced by different lipid

compositions of membranes from oocytes and plant vacuoles, or AtClC-a might

endogenously form complexes with other proteins. These other proteins may

include structurally unrelated ancillary β-subunits (as known for some

mammalian CLC proteins) (10,

41), other AtClC isoforms

(12) (CLC proteins function as

dimers (22,

25,

30)), or anchoring

proteins.

only

∼1.6-fold, this increase was much more drastic with vacuolar currents

(16). Several explanations may

be invoked. Current properties may be influenced by different lipid

compositions of membranes from oocytes and plant vacuoles, or AtClC-a might

endogenously form complexes with other proteins. These other proteins may

include structurally unrelated ancillary β-subunits (as known for some

mammalian CLC proteins) (10,

41), other AtClC isoforms

(12) (CLC proteins function as

dimers (22,

25,

30)), or anchoring

proteins.

The outward rectification of AtClC-a is less strong than that of ClC-4 and

-5, both of which do not transport measurably at negative voltages

(26). This difference is not

due to the presence of proline instead of serine in the signature sequence of

AtClC-a, as revealed by our mutagenesis experiments. The weaker rectification

of AtClC-a may be crucial for the proton-driven uptake of

into vacuoles that may have a

lumen-positive voltage. The much stronger rectification of ClC-4 and -5 is

a priori difficult to reconcile with their presumed role in

electrical compensation of H+-ATPase currents

(11).

into vacuoles that may have a

lumen-positive voltage. The much stronger rectification of ClC-4 and -5 is

a priori difficult to reconcile with their presumed role in

electrical compensation of H+-ATPase currents

(11).

The heterologous expression of AtClC-a allowed the first structure-function

analysis of a plant CLC protein. We began by studying two glutamate residues

that are conserved in all confirmed CLC exchangers. The gating glutamate is

important for anion/proton coupling in CLC exchangers, as well as for gating

in CLC Cl– channels. Its replacement in AtClC-a by alanine

uncoupled anion flux from protons as in other CLC transporters

(17,

21). Similar to ClC-4 and

ClC-5, this mutation also drastically changed current rectification, with both

inward and outward rectification being observed. Unlike equivalent mutations

in ClC-4 and -5, this uncoupling AtClC-a mutation also drastically changed the

current ratio. This change did not depend on the presence of a proline in the

signature sequence.

current ratio. This change did not depend on the presence of a proline in the

signature sequence.

In CLC anion/proton exchangers, the pathways of Cl– and H+ diverge at a point approximately half-way through the membrane and reach the cytoplasm at different points (27). A proton glutamate at the cytoplasmic CLC surface is thought to bind protons, handing them over to the gating glutamate using a poorly defined path. In both mammalian and E. coli CLC exchangers, this glutamate could be replaced by other titratable amino acids without abolishing anion/proton coupling (21, 27, 42). When mutated to nontitratable residues, however, Cl– and H+ transport were below detection levels in ClC-4 and -5 (21), whereas small, uncoupled anion currents were observed with EcClC-1 (42). This can be rationalized by a blockade of anion/proton exchange at the gating glutamate, when the supply of protons ceases (21). The uncoupled but reduced anion flux in EcClC-1 might be owed to “slippage” past the central exchange site (42). This model is strongly supported by double mutants in ClC-4 and -5, in which the uncoupling gating glutamate mutation rescued the uncoupled anion flux (21). Exactly this situation was found here with AtClC-a.

It was puzzling that anion transport of ClC-4, -5, and EcClC-1 is largely

uncoupled from proton transport with the polyatomic anion

(21), whereas AtClC-a

efficiently couples

(21), whereas AtClC-a

efficiently couples  to proton

countertransport (16), an

essential property for its role in accumulating this plant nutrient in

vacuoles. Using sequence comparison, we identified a proline in the CLC

signature sequence as a likely candidate for this difference. In all animal

CLC proteins, this position is occupied by serine. Indeed, when Pro-160 in

AtClC-a was mutated to serine, the plant transporter performed the

Cl–/H+ exchange with similar efficiency as the

to proton

countertransport (16), an

essential property for its role in accumulating this plant nutrient in

vacuoles. Using sequence comparison, we identified a proline in the CLC

signature sequence as a likely candidate for this difference. In all animal

CLC proteins, this position is occupied by serine. Indeed, when Pro-160 in

AtClC-a was mutated to serine, the plant transporter performed the

Cl–/H+ exchange with similar efficiency as the

exchange, rather than preferring

exchange, rather than preferring  as

in the WT. Importantly, when the equivalent serine of ClC-5 was mutated to

proline, ClC-5 mediated an efficient

as

in the WT. Importantly, when the equivalent serine of ClC-5 was mutated to

proline, ClC-5 mediated an efficient

exchange

both in the present study as well as in parallel work by Zifarelli and Pusch

(38). A novel method

(43) to measure proton

transport allowed these authors to show that ClC-5(S168P) had gained an

exchange

both in the present study as well as in parallel work by Zifarelli and Pusch

(38). A novel method

(43) to measure proton

transport allowed these authors to show that ClC-5(S168P) had gained an

coupling

ratio of ∼2 at voltages between +40 and +60 mV, indistinguishable from

that for Cl–/H+ exchange

(38). Our data on other ClC-5

mutants at this position (Fig.

5K) largely agree with their results

(38) but show interesting

differences with data obtained for AtClC-a

(Fig. 4F). The

substitution of the critical proline by glycine in AtClC-a did not interfere

with its efficient

coupling

ratio of ∼2 at voltages between +40 and +60 mV, indistinguishable from

that for Cl–/H+ exchange

(38). Our data on other ClC-5

mutants at this position (Fig.

5K) largely agree with their results

(38) but show interesting

differences with data obtained for AtClC-a

(Fig. 4F). The

substitution of the critical proline by glycine in AtClC-a did not interfere

with its efficient

exchange, possibly suggesting that a helix breaker might be sufficient to

support such an exchange. However, glycine at the equivalent position in ClC-5

does not increase currents in the presence of

exchange, possibly suggesting that a helix breaker might be sufficient to

support such an exchange. However, glycine at the equivalent position in ClC-5

does not increase currents in the presence of

nor does it enable efficient

nor does it enable efficient

exchange

(data not shown) (38).

exchange

(data not shown) (38).

Only four of seven Arabidopsis CLC proteins have a proline in

their signature sequence, with the remaining three displaying a serine like

all known animal CLC proteins. This suggests that all these four

proline-containing AtClC proteins function as

exchangers. A more definitive assignment of their physiological roles,

however, is not yet possible. In this respect, it is interesting to note that

only AtClC-c and AtClC-d were reported to complement

(12,

32) growth phenotypes of a

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain deleted for the single yeast CLC

(ScClC or Gef) (33). Whether

this is related to the fact that AtClC-c and -d, just like ScClC, carry serine

in their signature sequence and hence probably prefer chloride over nitrate

remains unclear.

exchangers. A more definitive assignment of their physiological roles,

however, is not yet possible. In this respect, it is interesting to note that

only AtClC-c and AtClC-d were reported to complement

(12,

32) growth phenotypes of a

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain deleted for the single yeast CLC

(ScClC or Gef) (33). Whether

this is related to the fact that AtClC-c and -d, just like ScClC, carry serine

in their signature sequence and hence probably prefer chloride over nitrate

remains unclear.

The interpretation of conductance ratios of ClC-5, and by extension of

AtClC-a, is complicated by results from a noise analysis that indicates that

ClC-5 switches from transporting to nontransporting modes of operation

(21). Such a gating of

transport activity probably underlies the time-dependent current relaxation

upon depolarization of ClC-5 and might also explain the slow

depolarization-induced activation of vacuolar currents observed by De Angeli

et al. (16).

Zifarelli and Pusch (38)

recently concluded from their noise analysis that the increase in ClC-5

currents with  is not due to an

increased “unitary conductance” of the “turned on”

transporter (which would include slippage of the anion) but rather to a higher

“open probability” of the transporter. However, it seems unlikely

that the difference in

is not due to an

increased “unitary conductance” of the “turned on”

transporter (which would include slippage of the anion) but rather to a higher

“open probability” of the transporter. However, it seems unlikely

that the difference in

ratios between WT AtClC-a and mutant P160S is solely due to an effect on

gating. This is because this mutation not only modified conductance ratios but

also changed the apparent permeability (reversal potentials). We therefore

conclude that the proline-serine exchange affects the ion selectivity of the

exchange process. This conclusion is indirectly bolstered by the

single-channel analysis of the ClC-0(S123T) mutant, which demonstrated changes

in ion selectivity and other pore properties

(25) and by the changed ion

selectivity of the ClC-0(S123P) mutant described here. Unfortunately, we

cannot draw similar conclusions for ClC-5 because its strong rectification

precludes the determination of reversal potentials.

ratios between WT AtClC-a and mutant P160S is solely due to an effect on

gating. This is because this mutation not only modified conductance ratios but

also changed the apparent permeability (reversal potentials). We therefore

conclude that the proline-serine exchange affects the ion selectivity of the

exchange process. This conclusion is indirectly bolstered by the

single-channel analysis of the ClC-0(S123T) mutant, which demonstrated changes

in ion selectivity and other pore properties

(25) and by the changed ion

selectivity of the ClC-0(S123P) mutant described here. Unfortunately, we

cannot draw similar conclusions for ClC-5 because its strong rectification

precludes the determination of reversal potentials.

In the crystal of EcClC-1, the equivalent serine participates in the

coordination of a Br– ion (used as a Cl–

substitute in crystallography) in the central binding site

(22). Several mutations in

Tyr-445, another residue involved in this coordination

(22), uncoupled chloride from

proton fluxes (44). Such

mutations were associated with a reduced presence or complete absence of

anions at the central binding site

(44). Likewise, crystals

obtained in the presence of  revealed that this anion, which uncouples Cl– from

H+ transport in EcClC-1, cannot be detected at this position

(18). Thus, anion/proton

coupling seems to require that an anion occupies this site. It was proposed

that this anion serves as an intermediate binding site for protons on their

way from the proton glutamate to the gating glutamate, leading to the

seemingly outlandish proposal of HCl as a proton transport intermediate

(45). We suggest that the

replacement of serine by proline in the GSGIPE sequence enables

revealed that this anion, which uncouples Cl– from

H+ transport in EcClC-1, cannot be detected at this position

(18). Thus, anion/proton

coupling seems to require that an anion occupies this site. It was proposed

that this anion serves as an intermediate binding site for protons on their

way from the proton glutamate to the gating glutamate, leading to the

seemingly outlandish proposal of HCl as a proton transport intermediate

(45). We suggest that the

replacement of serine by proline in the GSGIPE sequence enables

to occupy the central anion binding

site, thereby leading to efficient proton coupling.

to occupy the central anion binding

site, thereby leading to efficient proton coupling.

In summary, a breakthrough in heterologous expression of AtClC-a has

allowed us to extend the structure-function analysis of anion/proton exchange

to plant CLC proteins. Mutagenesis of critical gating and proton glutamates

resulted in changes of proton coupling and rectification that bear close

resemblance to results from mammalian endosomal CLC proteins. However, there

were also significant differences in effects on

conductance. We further identified

an important proline residue in the CLC signature sequence of AtClC-a that is

crucial for its efficient

conductance. We further identified

an important proline residue in the CLC signature sequence of AtClC-a that is

crucial for its efficient

exchange

activity and that conferred more efficient

exchange

activity and that conferred more efficient

coupling

on the mammalian ClC-5 exchanger and an increase in

coupling

on the mammalian ClC-5 exchanger and an increase in

conductance on the Torpedo

Cl– channel ClC-0. Our work provides a basis for future

studies of other plant CLC proteins and their comparison to mammalian

counterparts.

conductance on the Torpedo

Cl– channel ClC-0. Our work provides a basis for future

studies of other plant CLC proteins and their comparison to mammalian

counterparts.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Fast, N. Kroenke, P. Seidler, and S. Zillmann for technical assistance.

This work was supported by a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant (to A. A. Z. and T. J. J.) and by the Leibniz Graduate School of Biophysics.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: AtCIC-n, member n of the CLC

family of Cl– channels and transporters in the plant

Arabidopsis thaliana; CIC-n, member n of the CLC

family of chloride channel and transporters (in animals);

pHi, intracellular pH; pH0,

extracellular pH;  and

I(Cl–), current in the presence of

and

I(Cl–), current in the presence of

and Cl–,

respectively, which in CLC exchangers also involves an H+

component; WT, wild-type; MES, 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid;

BCECF, 2′,7′-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein.

and Cl–,

respectively, which in CLC exchangers also involves an H+

component; WT, wild-type; MES, 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid;

BCECF, 2′,7′-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein.

References

- 1.Jentsch, T. J. (2008) Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 3–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bösl, M. R., Stein, V., Hübner, C., Zdebik, A. A., Jordt, S. E., Mukhophadhyay, A. K., Davidoff, M. S., Holstein, A. F., and Jentsch, T. J. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 1289–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon, D. B., Bindra, R. S., Mansfield, T. A., Nelson-Williams, C., Mendonca, E., Stone, R., Schurman, S., Nayir, A., Alpay, H., Bakkaloglu, A., Rodriguez-Soriano, J., Morales, J. M., Sanjad, S. A., Taylor, C. M., Pilz, D., Brem, A., Trachtman, H., Griswold, W., Richard, G. A., John, E., and Lifton, R. P. (1997) Nat. Genet. 17, 171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumura, Y., Uchida, S., Kondo, Y., Miyazaki, H., Ko, S. B., Hayama, A., Morimoto, T., Liu, W., Arisawa, M., Sasaki, S., and Marumo, F. (1999) Nat. Genet. 21, 95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rickheit, G., Maier, H., Strenzke, N., Andreescu, C. E., De Zeeuw, C. I., Muenscher, A., Zdebik, A. A., and Jentsch, T. J. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 2907–2917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinmeyer, K., Klocke, R., Ortland, C., Gronemeier, M., Jockusch, H., Gründer, S., and Jentsch, T. J. (1991) Nature 354, 304–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piwon, N., Günther, W., Schwake, M., Bösl, M. R., and Jentsch, T. J. (2000) Nature 408, 369–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornak, U., Kasper, D., Bösl, M. R., Kaiser, E., Schweizer, M., Schulz, A., Friedrich, W., Delling, G., and Jentsch, T. J. (2001) Cell 104, 205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasper, D., Planells-Cases, R., Fuhrmann, J. C., Scheel, O., Zeitz, O., Ruether, K., Schmitt, A., Poët, M., Steinfeld, R., Schweizer, M., Kornak, U., and Jentsch, T. J. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 1079–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lange, P. F., Wartosch, L., Jentsch, T. J., and Fuhrmann, J. C. (2006) Nature 440, 220–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jentsch, T. J. (2007) J. Physiol. (Lond.) 578, 633–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hechenberger, M., Schwappach, B., Fischer, W. N., Frommer, W. B., Jentsch, T. J., and Steinmeyer, K. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 33632–33638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marmagne, A., Vinauger-Douard, M., Monachello, D., de Longevialle, A. F., Charon, C., Allot, M., Rappaport, F., Wollman, F. A., Barbier-Brygoo, H., and Ephritikhine, G. (2007) J. Exp. Bot. 58, 3385–3393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von der Fecht-Bartenbach, J., Bogner, M., Krebs, M., Stierhof, Y. D., Schumacher, K., and Ludewig, U. (2007) Plant J. 50, 466–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Angeli, A., Monachello, D., Ephritikhine, G., Frachisse, J. M., Thomine, S., Gambale, F., and Barbier-Brygoo, H. (2009) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 364, 195–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Angeli, A., Monachello, D., Ephritikhine, G., Frachisse, J. M., Thomine, S., Gambale, F., and Barbier-Brygoo, H. (2006) Nature 442, 939–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Accardi, A., and Miller, C. (2004) Nature 427, 803–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguitragool, W., and Miller, C. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 362, 682–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheel, O., Zdebik, A., Lourdel, S., and Jentsch, T. J. (2005) Nature 436, 424–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picollo, A., and Pusch, M. (2005) Nature 436, 420–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zdebik, A. A., Zifarelli, G., Bergsdorf, E.-Y., Soliani, P., Scheel, O., Jentsch, T. J., and Pusch, M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 4219–4227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dutzler, R., Campbell, E. B., Cadene, M., Chait, B. T., and MacKinnon, R. (2002) Nature 415, 287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dutzler, R., Campbell, E. B., and MacKinnon, R. (2003) Science 300, 108–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gründer, S., Thiemann, A., Pusch, M., and Jentsch, T. J. (1992) Nature 360, 759–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludewig, U., Pusch, M., and Jentsch, T. J. (1996) Nature 383, 340–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedrich, T., Breiderhoff, T., and Jentsch, T. J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 896–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Accardi, A., Walden, M., Nguitragool, W., Jayaram, H., Williams, C., and Miller, C. (2005) J. Gen. Physiol. 126, 563–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, X., Wang, T., Zhao, Z., and Weinman, S. A. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. 282, C1483–C1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuñiga, L., Niemeyer, M. I., Varela, D., Catalán, M., Cid, L. P., and Sepúlveda, F. V. (2004) J. Physiol. (Lond.) 555, 671–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Middleton, R. E., Pheasant, D. J., and Miller, C. (1996) Nature 383, 337–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinreich, F., and Jentsch, T. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 2347–2353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaxiola, R. A., Yuan, D. S., Klausner, R. D., and Fink, G. R. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95, 4046–4050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greene, J. R., Brown, N. H., DiDomenico, B. J., Kaplan, J., and Eide, D. J. (1993) Mol. Gen. Genet. 241, 542–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinmeyer, K., Schwappach, B., Bens, M., Vandewalle, A., and Jentsch, T. J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 31172–31177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jentsch, T. J., Steinmeyer, K., and Schwarz, G. (1990) Nature 348, 510–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lorenz, C., Pusch, M., and Jentsch, T. J. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93, 13362–13366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geelen, D., Lurin, C., Bouchez, D., Frachisse, J. M., Lelièvre, F., Courtial, B., Barbier-Brygoo, H., and Maurel, C. (2000) Plant J. 21, 259–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zifarelli, G., and Pusch, M. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 175–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pusch, M., Ludewig, U., Rehfeldt, A., and Jentsch, T. J. (1995) Nature 373, 527–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lurin, C., Geelen, D., Barbier-Brygoo, H., Guern, J., and Maurel, C. (1996) Plant Cell 8, 701–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Estévez, R., Boettger, T., Stein, V., Birkenhäger, R., Otto, M., Hildebrandt, F., and Jentsch, T. J. (2001) Nature 414, 558–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim, H. H., and Miller, C. (2009) J. Gen. Physiol. 133, 131–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zifarelli, G., Soliani, P., and Pusch, M. (2007) Biophys. J. 94, 53–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Accardi, A., Lobet, S., Williams, C., Miller, C., and Dutzler, R. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 362, 691–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller, C., and Nguitragool, W. (2009) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 364, 175–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]