Abstract

The anti-inflammatory effect of mammalian heparin analogues, named dermatan sulfate and heparin, isolated from the ascidian Styela plicata was accessed in a TNBS-induced colitis model in rats. Subcutaneous administration of the invertebrate compounds during a 7-day period drastically reduced inflammation as observed by the normalization of the macroscopic and histological characteristics of the colon. At the molecular level, a decrease in the production of TNF-α, TGF-β, and VEGF was observed, as well as a reduction of NF-κB and MAPK kinase activation. At the cellular level, the heparin analogues attenuated lymphocyte and macrophage recruitment and epithelial cell apoptosis. A drastic reduction in collagen-mediated fibrosis was also observed. No hemorrhagic events were observed after glycan treatment. These results strongly indicate the potential therapeutic use of these compounds for the treatment of colonic inflammation with a lower risk of hemorrhage when compared with mammalian heparin.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD)3 comprise basically Crohn disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis and are characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. The etiology of IBD is complex and multifactorial, involving genetic predisposition and environmental triggers, as well as microbial and immune factors (1). In CD, the chronic inflammatory process is a consequence of an imbalance in the production of proinflammatory and immunoregulatory cytokines, which results in a T helper cell type 1 (Th1) phenotype (2, 3).

Th1-type response is characterized by the production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-12, IL-18, interferon (IFN)-γ, among other proinflammatory cytokines, and also involves the production of growth factors such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (4–6). In this context, the nuclear transcription factor κB (NF-κB) was identified as a key regulator of the expression of proinflammatory genes, determining the course of mucosal inflammation in IBD (7). The increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in IBD intestinal mucosa is accompanied by the over expression of adhesion molecules, including the selectins (8, 9).

Animal models of mucosal inflammation have been utilized to investigate the pathogenesis of IBD and to evaluate possible new therapies. The trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis constitutes an established experimental model, which exhibits clinical and histological similarities to CD, and the course of colonic damage has been well characterized as a Th1-type immune response, with the resulting production of proinflammatory cytokines (10).

Heparin is a sulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAG) largely utilized in the clinical practice for anticoagulation and prevention and treatment of vascular thromboembolism (11, 12). Apart from its well-established anticoagulant and antithrombotic effects, heparin has anti-inflammatory properties such as inhibition of leukocyte adhesion and migration (13), and modulation of cytokine production (14). Based on these activities, and the suggested efficacy observed in several open clinical studies (15–17), heparin has been proposed as an alternative for the treatment of IBD. However, heparin therapy may cause hemorrhage and other adverse side effects (18).

Our laboratory has isolated and characterized several heparin analogues from marine invertebrates (19–24). The study of the anticoagulant properties of the marine invertebrate glycans indicated that although they are capable of inhibiting venous and arterial thrombosis, they are less anticoagulant and have no bleeding effect after intravenous administration to experimental animals. Therefore, in the present work, we investigate the anti-inflammatory effect of heparin analogues obtained from the ascidian Styela plicata in a rat model of colon inflammation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals—Male Wistar rats (each weighing between 250 and 300 g) obtained from a local supplier were maintained on a 12-h/12-h light and dark cycle in a temperature-controlled room (24 °C). Animals were housed in rack-mounted, wire cages with 3 animals per cage. Standard laboratory pelleted formula and tap water were provided ad libitum. The care and use of animals, as well as procedures reported in this study were approved by the institutional care committee of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and are in accordance with the guidelines of the International Care and Use Committee of the National Institutes of Health, and Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (25).

Induction of Colitis—On day (d) 0, rats were anesthetized subcutaneously with ketamine (35 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg), and colitis was induced by intracolonic instillation of 0.8 ml of a solution containing 20 mg of 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) (Sigma) in 20% ethanol (Merck, Damstadt, Germany) using a rubber cannula (8-cm long) inserted through the rectum. Thereafter, animals were allowed access to standard chow and water ad libitum. Clinical manifestations such as diarrhea, bleeding, and weight loss were observed during this period.

Experimental Design—After an initial acclimation period of 1 week, animals were assigned randomly to one of five groups of 10 animals each, and followed during 1 week. The colitis group (TNBS) was submitted to colitis induction but did not receive any treatment, and animals were sacrificed on experimental day 7. There were 4 GAG-treated groups: mam Hep, mammalian heparin (Hep); mam DS, mammalian dermatan sulfate (DS); S. plicata Hep and S. plicata DS. These groups were submitted to colitis induction followed by treatment with the indicated GAG (4 or 8 mg/kg per day) by a subcutaneous route over 7 days. In control experiments, the ascidian GAGs were either treated with chondroitin ABC-lyase or nitrous acid. Normal rats not submitted to any intervention constituted the control group, which was sacrificed after the acclimation period.

For the surgical procedure, animals were anesthetized as described in the previous paragraph and submitted to a mild laparotomy under sterile technique. The distal colon was removed, opened longitudinally, rinsed with sterile saline, and scored. After scoring, three tissue samples were excised from the colon for histological assessment. A quick death procedure by cervical dislocation was uniformly performed in all animals.

Histological Inflammatory Scores of the Colon—Specimens were fixed in 40 g/liter formaldehyde saline, embedded in paraffin, cut into 5-μm sections, stained with hematoxylin-eosin stain, and examined microscopically by two independent observers. The following histological parameters were studied: ulceration, hyperplasia, and inflammatory infiltrate. For both inflammatory infiltrate and hyperplasia, grading was considered: 3, severe; 2, moderate; 1, mild; 0, absent. For ulcers, grading was: 4, diffuse glandular disruption or extensive deep ulceration; 3, glandular disruption or focal deep ulceration; 2, diffuse superficial ulceration; 1, focal superficial ulceration; and 0, absent (26).

Immunohistochemical Analysis of the Colon—Tissue samples were immediately embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Miles Scientific Laboratories Ltd, Naperville, IL) and snap-frozen in isopentane in a liquid nitrogen bath. Samples were then stored at -80 °C until processing, and cut into 6-μm section in a cryostat maintained at -20 °C. Tissue sections were air-dried and fixed for 10 min in a 1:1 solution of chloroformacetone. Immunologic assessment of the intestinal mucosa was made using indirect immunoperoxidase technique using the following antibodies: mouse monoclonal anti-rat ED1 (Serotec Ltd., Oxford, UK) to macrophages; mouse monoclonal anti-rat CD3 (PC3/188) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to lymphocytes; mouse monoclonal anti-rat p65 (F-6) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to NF-κB. Briefly, frozen sections were immersed in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. After rinsing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% Tween 20 for 10 min, tissue sections were incubated with nonimmune horse serum for 30 min and, subsequently, with the respective monoclonal antibody in a humidified chamber overnight, at room temperature. Two sections from each sample were incubated with either PBS alone or mouse monoclonal IgG1 (concentration-matched) (Dako A/S) and served as negative controls. After rinsing in PBS for 10 min, all tissue sections were incubated for 30 min with a goat anti-mouse peroxidase conjugate (Zymed Laboratories Inc., Inc., San Francisco, CA). Additional rinsing was followed by development with a solution containing hydrogen peroxide and diaminobenzidine, dehydrated, and mounted in histological mounting medium.

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy—For the indirect immunofluorescence study, frozen sections were incubated at room temperature with 2.5% bovine serum albumin + 2.0% nonfat milk + 8.0% fetal calf serum blocking buffer under shaking for 30 min. The sections were then incubated with appropriately diluted primary antibodies in PBS solution + 1.0% fetal calf serum for 1 h in wet atmosphere at 37 °C. The primary antibody used was the monoclonal mouse anti-rat P-ERK1/2 (1:50) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After rinsing three times in PBS for 5 min each, tissue sections were incubated for 1 h with a FITC-conjugated Fab fraction of goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Dako A/S). Slides were counterstained with Evan blue-diluted 0.01% in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, mounted in an anti-fading medium containing buffered glycerol and p-phenylenediamine (Sigma), and then observed with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope. At least four representative images from each slide were captured. Two sections from each sample were incubated with either PBS alone or FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody and served as negative controls.

Assessment of Collagen Deposition in the Colon—Specimens were fixed in 40 g/liter formaldehyde saline, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-μm sections. The phosphomolibidic acid-picro-sirius red dye was used to stain collagen fibers in tissue (27, 28). At least 15 different areas per tissue section were analyzed under light microscopy.

Detection of Apoptosis using TUNEL Assay—Paraffin-embedded colon samples were de-waxed in xylene twice for 5 min each time and then rehydrated in graded ethanol (100-70%) three times, followed by rehydration in PBS for 30 min. Apoptotic cells were detected by the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase (TdT)-mediated dUDP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay, using the in situ apoptosis detection kit ApopTag Fluorescein (Chemicon International, Inc. Temecula, CA), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Sections were analyzed in a confocal microscope.

Quantitative Assessment of Colon Sections—Quantitative analysis of tissue sections (under light microscopy) and captured immunofluorescence images (under confocal laser-scanning microscope) was carried out using a computer-assisted image analyser (Image-Pro Plus Version 4.1 for Windows, Media Cybernetics, LP, Silver Spring, MD). Any epithelial and lamina propria cells exhibiting identifiable reactivity distinct from background were regarded as positive.

In the immunoperoxidase and immunofluorescence studies, the densities of the different cell subsets were defined by the number of immunoreactive cells in the lamina propria per millimeter-squared (counted in at least 10 different areas). In the epithelium, the density of apoptotic cells was defined as the percentage of immunoreactive cells within at least 500 epithelial cells in the crypts and in the surface epithelium of longitudinally sectioned colonic pits.

The density of collagen fibers was defined by the area positively stained for collagen in relation to total intestinal tissue per millimeter-squared using an imaging analysis system. Two independent observers who were unaware of the experimental animal data examined all tissue sections and captured images.

Organ Culture and Cytokine Measurements—Colonic mucosal explants were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen), 2 mm l-glutamine (Sigma), 50 μm 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 10 mm HEPES (Promega), penicillin (100 killiunits/liter) and streptomycin (100 mg/liter) (Sigma) for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. After incubation for 24 h, the supernatant was collected and stocked at -20 °C. Samples were centrifuged, and the supernatants used for measurement of the concentration of cytokines TNF-α, TGF-β, and VEGF by a commercial sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method (R&D System, MN). The total protein content of the biopsy specimens was estimated by the Lowry method. In our data, biopsy specimen wet weight was shown to correlate closely with protein content of tissue homogenates. The minimum detectable concentration of rat TNF-α, TGF-β, and VEGF was typically less than 5.0 ng/liter.

Isolation and Quantification of GAGs—The dried intestinal samples (∼0.5 g) were individually suspended in 10 ml of 0.1 m sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), containing 50 mg of papain, 5 mm EDTA, and 5 mm cysteine, and incubated at 60 °C for 24 h. The mixtures were centrifuged (2000 × g for 10 min at room temperature). Another 50 mg of papain in 10 ml of the same buffer, containing 5 mm EDTA and 5 mm cysteine was added to the precipitate. The mixture was then incubated for another 24 h. The clear supernatants from the two extractions were combined, and the GAGs precipitated with a solution of cetylpyridinum chloride (0.5% final concentration), followed by 2 vol. of 95% ethanol and maintained at 4 °C for 24 h. The precipitate formed was collected by centrifugation (2000 × g for 10 min at room temperature), freeze-dried, and dissolved in 2 ml of distilled water. The amount of GAGs in the renal samples was estimated by the content of hexuronic acid, using the carbazole reaction (29).

Agarose Gel Electrophoresis—The intact or enzyme-degraded GAGs from the different intestinal samples were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, as described previously (23). Briefly, about 1.5 μg (as uronic acid) of the glycans, and a mixture of standard GAGs, containing chondroitin sulfate, dermatan sulfate, and heparan sulfate (1.5 μg as uronic acid of each) were applied to a 0.5% agarose gel in 0.05 m 1,3-diaminopropane/acetate (pH 9.0), and run for 1 h at 110 mV. After electrophoresis, the GAGs were fixed with aqueous 0.1% cetylmethylammonium bromide solution and stained with 0.1% toluidine blue in acetic acid/ethanol/water (0.1:5:5, v/v/v). The relative proportions of the GAGs were estimated by densitometry of the metachromatic bands on a Bio-Rad densitometer, following agarose gel electrophoresis.

The identity of GAGs was determined by agarose gel electrophoresis before and after incubation with specific GAG-lyases (Chondroitin AC-lyase, Chondroitin ABC-lyase) or deaminative cleavage with nitrous acid as described previously (23).

Macrophage Activation Assay—Rat peritoneal macrophages were obtained by washing out the peritoneal cavity with 5 ml of ice-cold sterile RPMI 1640 serum-free medium and cultured at 37 °C for 4 h in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. After incubation, non-adherent cells were removed by washing with serum-free medium. Adherent cells were incubated in 24-well tissue culture plates at a density of 106 cells per well with RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Invitrogen) for 24 h in the presence of a range of heparin concentrations (5.0, 10, 20, and 40 μg/ml) plus LPS (1 μg/ml) (Sigma), added either concomitantly or 2 h after heparin under 5% CO2 atmosphere. In some experiments LPS was omitted to check the effect of heparin on macrophages.

Determination of TNF-α Production—The cell culture supernatant was collected from the cultures of macrophages cells stimulated with heparin or LPS or heparin plus LPS. The concentration of TNF-α was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit, according to the instructions of the manufacturer (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Ex Vivo Anticoagulant Action Measured by aPTT (Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time)—At experimental day 7, animals from the different groups were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of 100 mg/kg of ketamine (Cristália, São Paulo, Brazil) and 16 mg/kg of xylazine (Bayer AS, São Paulo, Brazil), supplemented as needed. The right carotid artery was isolated and cannulated with a 22-gauge catheter (Jelco, Johnson & Johnson Medical Inc.) for blood collection. Blood samples (∼500 μl) were collected into 2.8% sodium citrate (9:1, v/v) for analysis of aPTT. At least 5 animals were used per group. aPTT was carried out as following: rat plasma (100 μl) was incubated with 100 μl of aPTT reagent (Celite-Biolab) at 37 °C. After 2 min of incubation 100 μl of 0.25 m CaCl2 were added to the mixtures and the clotting time recorded in a coagulometer (Amelung KC4A).

Platelet Counts—Blood samples were carefully drawn on heparin from the portal vein during surgery just prior to colon removal. The platelet count in the whole blood was measured on an automatic hematology analyzer. Results are expressed as number of cells per cubic millimeter.

Statistical Analysis—Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software SPSS for Windows (Version 10.1, SPSS Inc., 1989–1999). Statistical differences among the experimental groups were evaluated with the one-way ANOVA test in which pairwise multiple comparisons were carried out using the Dunnett T3 test. Correlations between inflammatory scores, the densities of positive cells measured by immunohistochemistry, and the cytokine levels were assessed using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Histomorphological Changes in the Colonic Tissue—We found that animals subjected to TNBS treatment developed colitis accompanied by a significant weight loss. Evident morphological changes were observed predominantly in the distal colon of the animals. Inflammatory lesions in the colon included mucosal edema, ulceration, and evidence of transmural inflammation. Therapeutic approach consisted of subcutaneous administration of ascidian or mammalian heparin and dermatan sulfate (DS), initiated concomitantly with TNBS treatment and continued for 7 days. A drastic attenuation of the inflammatory lesions was observed macroscopically in the animals after subcutaneous administration of mammalian or ascidian GAGs at the dose of 8 mg/kg. No significant changes were observed at the dose of 4 mg/kg (not shown).

Histological analysis of formalin-fixed HE-stained intestinal sections revealed an increase in the microscopic damage score in all TNBS-treated animals, when compared with the normal mucosa of control animals (Fig. 1, A and B). Administration of mammalian or ascidian GAGs (8 mg/kg) significantly reduced the inflammatory scores in the TNBS-treated group. However, the scores obtained by ascidian heparin were significantly (p < 0.001) lower than that obtained by the mammalian counterpart. Administration of nitrous acid-treated S. plicata heparin or chondroitin ABC-lyase-treated S. plicata DS to the TNBS group abolished the beneficial effect of the GAGs (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of heparin analogues on histological parameters of inflamed colon. Colonic samples from Wistar rats after TNBS-induced colitis without or with heparin or ascidian heparin analogues administration were fixed in 40 g/liter formaldehyde saline and stained with HE (A). Unfractionated mammalian heparin (porcine intestinal mucosa) or ascidian heparin analogues (dermatan sulfate and heparin from S. plicata) (8 mg/kg/day) were administered to the animals subcutaneously for 7 days. The colonic samples were scored according to the following histological parameters: ulceration, hyperplasia, and inflammatory infiltrate. For both inflammatory infiltrate and hyperplasia, grading was considered: 3, severe; 2, moderate; 1, mild; 0, absent. For ulcers, grading was: 4, diffuse glandular disruption or extensive deep ulceration; 3, glandular disruption or focal deep ulceration; 2, diffuse superficial ulceration; 1, focal superficial ulceration; and 0, absent (B). In control experiments, the histological evaluation was performed after treatment of the ascidian GAGs with nitrous acid (HONO) or chondroitin ABC lyase (Chase ABC) (C). Values are mean ± S.E. of 10 animals/group. Statistical differences among the experimental groups were evaluated with the one-way ANOVA test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Mam, mammalian. Magnification, ×100. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Cellular Infiltration in the Colonic Tissue—TNBS colitis is characterized by a Th1-mediated immune response with intense infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages (10). Therefore, we evaluated the infiltrating cell profile in inflamed colonic tissue. The number of macrophages and T-cells significantly increased in the colonic lamina propria of all TNBS-treated animals, when compared with that of the control group (Fig. 2). Subcutaneous administration of mammalian or ascidian GAGs reduced the number of both macrophages (Fig. 2) and T-cells (Fig. 3) in TNBS-treated animals. Heparin administration, regardless of its source, was more effective in reducing infiltrating cells, when compared with DS (Figs. 2 and 3). However, ascidian heparin was more efficient in reducing macrophages than the mammalian counterpart (Fig. 2). Mammalian or ascidian DS reduced macrophages and CD4+ T-cells at the same extent (Figs. 2 and 3).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of heparin analogues on macrophage infiltration into the inflamed colon. Colonic samples from Wistar rats after TNBS-induced colitis without or with heparin or ascidian heparin analogues administration were immediately embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound, snap-frozen in isopentane in a liquid nitrogen bath, and submitted to immunohistochemical analysis using mouse monoclonal anti-rat ED1. Heparin and heparin analogues were administered to the animals as described in the legend of Fig. 1. The number of immunoreactive cells per millimeter-squared was counted in at least 10 different areas. Quantitative analysis of tissue sections were carried out under light microscopy at ×400 magnification. Values are mean ± S.E. of 10 animals/group. Statistical differences among the experimental groups were evaluated with the one-way ANOVA test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Mam, mammalian. Scale bar, 20 μm.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of heparin analogues on lymphocyte infiltration into the inflamed colon. Colonic samples from Wistar rats after TNBS-induced colitis without or with heparin or ascidian heparin analogues administration were immediately embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound, snap-frozen in isopentane in a liquid nitrogen bath, and submitted to immunohistochemical analysis using mouse monoclonal anti-rat CD3. Heparin and heparin analogues were administered to the animals as described in the legend of Fig. 1. The number of immunoreactive cells per millimeter-squared was counted in at least 10 different areas. Quantitative analysis of tissue sections were carried out under light microscopy at ×400 magnification. Values are mean ± S.E. of 10 animals/group. Statistical differences among the experimental groups were evaluated with the one-way ANOVA test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Mam, mammalian. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Cytokine Production and Intracellular Signaling in the Colonic Tissue—In IBD, increasing TNF-α production is associated with immunologically mediated tissue damage (30), and induces the activation of the NF-κB pathway in a variety of cell types. Therefore, we investigated whether the administration of mammalian or ascidian GAG could reduce TNF-α production and NF-κB activation in the inflamed colon.

TNBS treatment induced a ∼4-fold increase in the levels of TNF-α in the colonic tissue (Fig. 4A). The increase of the cytokine was accompanied by a clear increase in NF-κB activation (Fig. 5). Subcutaneous administration of GAGs, regardless of its source, drastically reduced TNF-α production to values observed in the basal level (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4A), and no significant difference was observed on the effect of DS or heparin. Similarly, NF-κB activation drastically reduced in inflamed colon after GAG administration (Fig. 5). No significant difference was observed in the effect of mammalian or ascidian DS and heparin. However, ascidian heparin induced the highest reduction in NF-κB activation.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of heparin analogues on cytokine production in the inflamed colon. Colonic mucosal explants from Wistar rats after TNBS-induced colitis without or with heparin or ascidian heparin analogues administration were cultured for 24 h at 37 °C. After centrifugation, the supernatants were used for measurement of the concentration of cytokines by a commercial sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method for rat TNF-α, TGF-β, and VEGF, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Heparin and heparin analogues were administered to the animals as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Quantitative analysis of tissue sections were carried out under light microscopy at ×400 magnification. Values were expressed as picogram of cytokine/mg protein and represent the mean ± S.E. of 10 animals/group. Statistical differences among the experimental groups were evaluated with the one-way ANOVA test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Mam, mammalian. Scale bar, 20 μm.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of heparin analogues on NF-κB activation in the inflamed colon. Colonic samples from Wistar rats after TNBS-induced colitis without or with heparin or ascidian heparin analogues administration were immediately embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound, snap-frozen, and submitted to immunohistochemical analysis using mouse monoclonal anti-rat p65. Heparin and heparin analogues were administered to the animals as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Quantitative analysis of tissue sections were carried out under light microscopy at ×800 magnification. The number of cells with nuclear NF-κB-staining (NF-κB-positive cells) per millimeter-squared was counted in at least 10 different areas. Values are mean ± S.E. of 10 animals/group. Statistical differences among the experimental groups were evaluated with the one-way ANOVA test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Mam, mammalian. Scale bar, 20 μm.

TNF-α production is also regulated by MAPK kinases, and inhibitors of these enzymes can reduce TNF-α synthesis (31). Therefore, we evaluated the activity of the MAPK kinase, ERK in the inflamed colonic tissue after GAG administration. TNBS treatment induced a ∼10-fold increase of ERK-active cells in the colonic tissue (Fig. 6). GAG administration, markedly reduced the number of ERK-active cells (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6). Mammalian GAGs reduced ERK-active cells in ∼50%, whereas ascidian DS and heparin reduced the number of ERK-active cells in ∼100%, reaching that of the basal level. No significant difference was observed on the effect of mammalian DS and heparin administration, as well as on that of ascidian DS and heparin.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of heparin analogues on ERK activation in the inflamed colon. Colonic samples from Wistar rats after TNBS-induced colitis without or with heparin or ascidian heparin analogues administration were immediately embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound, snap-frozen in isopentane in a liquid nitrogen bath, and submitted to immunohistochemical analysis using mouse monoclonal anti-rat P-ERK1/2 and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody. Heparin and heparin analogues were administered to the animals as described in the legend of Fig. 1. The tissues were observed with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope. The number of immunoreactive cells in the lamina propria per millimeter-squared was counted in at least 10 different areas. Values are mean ± S.E. of 10 animals/group. Statistical differences among the experimental groups were evaluated with the one-way ANOVA test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Mam, mammalian. Scale bar, 20 μm.

TGF-β is a key cytokine during periods of active inflammation, modulating epithelial cell restitution, and extracellular matrix remodeling after intestinal injury (32, 33). In addition, TGF-β increase is associated with collagen deposition that may result in fibrosis (34, 35). We investigated the effect of mammalian or ascidian GAG administration in TGF-β production and collagen deposition in the inflamed colon. TNBS induced a 4-fold increase in TGF-β production in the colon (Fig. 4C). The increase in TGF-β is correlated with increased collagen deposition in the lamina propria (Fig. 7). Administration of mammalian or ascidian GAGs regardless of the origin (mammalian or ascidian) and type (DS or heparin) reduced TGF-β production and collagen deposition to the levels observed in control animals (Figs. 4C and 7).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of heparin analogues on collagen deposition in the inflamed colon. Colonic samples from Wistar rats after TNBS-induced colitis without or with heparin or ascidian heparin analogues administration were fixed in 40 g/liter formaldehyde saline and the collagen fibers stained with phosphomolibidic acid-picro-sirius red dye. Heparin and heparin analogues were administered to the animals as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Density of collagen fibers was defined by the area positively stained for collagen in relation to total intestinal tissue per millimeter-squared using an imaging analysis system. At least 15 different areas per tissue section were analyzed under light microscopy at ×400 magnification. Values are mean ± S.E. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Mam, mammalian. Scale bar, 20 μm.

VEGF is an angiogenic cytokine, which modulates not only proliferation (36) but also the expression of cellular adhesion molecules in endothelial cells (37). In patients with IBD, VEGF is overexpressed both in the serum and in the intestinal mucosa (38). Recently, it has been shown that angiogenesis is an integral component of IBD pathogenesis and that inhibition of angiogenesis attenuates inflammation and vice versa (39). Therefore, we sought to determine whether GAG treatment would affect VEGF production in the inflamed colon. TNBS induced a 5.5-fold increase in VEGF production (Fig. 4B). The increase in VEGF correlated directly with active inflammation as denoted by the increased inflammatory parameters. Administration of mammalian or ascidian GAGs regardless of the origin (mammalian or ascidian) and type (DS or heparin) reduced VEGF production to levels observed in control animals (Fig. 4B). VEGF reduction correlated with the attenuation of inflammation, as indicated by the inflammatory parameters.

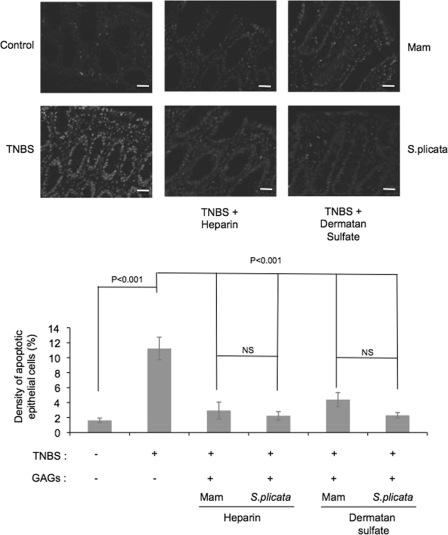

Apoptosis in the Colonic Tissue—Chronic inflammation of the intestine leads to epithelial destruction due to the action of cytokines produced by inflammatory cells. Therefore, we investigated if the epithelial protection observed after GAG administration in TNBS-treated animals could be related to an attenuation of the apoptotic process. TNBS treatment induced a 5-fold increase in the number of apoptotic intestinal epithelial cells. Administration of mammalian or ascidian GAGs, regardless of the origin (mammalian or ascidian) and type (DS or heparin), reduced the number of apoptotic epithelial cells to those observed in controls (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Effect of heparin analogues on epithelial cell apoptosis in the inflamed colon. Colonic samples from Wistar rats after TNBS-induced colitis without or with heparin or ascidian heparin analogues administration were embedded in paraffin and apoptotic cells were determined by the TUNEL assay, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Heparin and heparin analogues were administered to the animals as described in the legend of Fig. 1 and sections were analyzed in a confocal microscope. The density of apoptotic cells was defined as the percentage of immunoreactive cells within at least 500 epithelial cells in the crypts and in the surface epithelium of longitudinally sectioned colonic pits. Values are mean ± S.E. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Mam, mammalian. Magnification ×400. Scale bar, 20 μm.

GAGs Content in the Colonic Tissue—We have previously shown that in inflamed areas of the colon of patients with active Crohn disease there is an increase in the total amount of GAGs and a disorganized distribution of these molecules throughout the inflamed tissue (40). To investigate whether TNBS administration would produce a similar effect, total GAGs were isolated from rat normal or inflamed colonic tissues, quantified and subjected to biochemical analysis by agarose gel electrophoresis before and after degradation with specific GAG lyases. TNBS treatment induced a ∼2.2-fold increase in the content of GAGs (Table 1). This increment was due to an increase in the relative amounts on heparan sulfate (HS) and chondroitin sulfate (CS) and a parallel decrease in the amount of DS. Therapeutic administration of GAGs not only reduced the amount of total intestinal GAGs to that observed in control animals, but normalized the amounts of HS, CS, and DS.

TABLE 1.

Content and type of glycosaminoglycans present in colonic samples from Wistar rats after TNBS-induced colitis without or with heparin or ascidian heparin analogues administration

|

Group

|

Uronic

acida

|

GAGsb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS | DS | CS | ||||

| μg/mg | % | |||||

| Control | 1.20 ± 0.039c | 26.4 ± 0.245 | 45.2 ± 0.408 | 28.4 ± 0.159 | ||

| TNBS | 2.61 ± 0.077 | 33.7 ± 0.365 | 18.7 ± 0.195 | 47.6 ± 0.204 | ||

| TNBS+Hep Mam | 1.23 ± 0.059 | 28.56 ± 0.439 | 41.58 ± 0.444 | 29.86 ± 0.333 | ||

| TNBS+Hep Sp | 1.18 ± 0.033 | 20.88 ± 0.201 | 52.58 ± 0.367 | 26.86 ± 0.155 | ||

| TNBS+DS Mam | 1.17 ± 0.070 | 26.23 ± 0.284 | 43.44 ± 0.466 | 30.33 ± 0.395 | ||

| TNBS+DS Sp | 1.34 ± 0.115 | 25.33 ± 0.288 | 48.34 ± 0.326 | 26.33 ± 0.449 | ||

The content of glycosaminoglycan in each group was estimated by uronic acid after isolation of the glycans from the colon, as described under “Experimental Procedures”

The type of glycosaminoglycan was determined by agarose gel electrophoresis of the isolated glycans from each group before and after treatment with specific GAG lyases, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Hep, heparin; Mam, mammal; Sp, S. plicata

Values are median ± S.E., n = 7

Effect of Ascidian Heparin on Macrophage Activation—The inhibitory effect of S. plicata heparin on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated production of TNF-α was investigated in rat peritoneal macrophages (Fig. 9). LPS induced a significant increase in TNF-α production by macrophages. Administration of the ascidian GAG to macrophages prior to LPS stimulation caused a concentration-dependent inhibition in TNF-α production. At the concentration 40 μg/ml S. plicata Hep total inhibition was achieved. Ascidian heparin has no effect on macrophage in the absence of LPS stimulation (Fig. 9). Administration of ascidian Hep concomitantly to LPS stimulation also inhibited TNF-α production by macrophages (not shown).

FIGURE 9.

Effect of ascidian heparin on LPS-induced macrophage activation. Rat peritoneal macrophages were obtained as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cells were incubated in 24-well tissue culture plates for 24 h in the presence of a range of heparin concentrations (5.0, 10, 20, and 40 μg/ml) plus LPS (1 μg/ml) (Sigma), added 2 h after heparin treatment (A). In some experiments LPS was omitted to check the effect of heparin on the macrophages (B). The concentration of TNF-α was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (R&D Systems). The data shown are the average of two independent experiments. Each point was performed in duplicate.

Effect of GAG Treatment on Coagulation—Heparin therapy can lead to the development of hemorrhagic events (18) due to alterations in blood coagulation and platelet counts. Therefore, we investigated the effect of subcutaneous administration of GAGs in TNBS-treated animals. After GAG administration, blood was collected for time clotting analysis by determining the plasma aPTT and platelet count (Fig. 10, A and B). Administration of GAGs for 7 days did not produce any significant changes in plasma aPTT or in platelet counts.

FIGURE 10.

Effect of heparin analogues on coagulation and platelet counts ex vivo. At experimental day 7, animals from the different groups were anesthetized and blood samples were collected. A, aPTT was carried out in rat plasma using a coagulometer (Amelung KC4A) and expressed in seconds, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, platelet count in the whole blood was measured on an automatic hematology analyzer. Results are expressed as number of cells per cubic millimeter. Values are mean ± S.E. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Mam, mammalian.

DISCUSSION

Although great advances have been made in the field of etiopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases, currently approved therapies have limited efficacy and safety issues are still a matter of concern regarding the new agents. In fact, the two main anti-inflammatory drugs used to treat acute relapses of CD continue to be 5-acetil-salycilic acid and corticosteroids (reviewed in Ref. 41). Although these drugs can ameliorate intestinal inflammation, they have important side effects. This encourages the search for new anti-inflammatory agents. Here, we tested the therapeutic effect of heparin and heparin analogues in an animal model of IBD.

Similar to human CD, the resulting pathologic process of TNBS-induced colitis consisted of patchy inflammatory lesions and evidence of transmural inflammation in the distal colon. In regard to efficacy, both mammalian and marine invertebrate heparin, and dermatan sulfate consistently reduced the intestinal inflammation after 1 week of treatment, lowering the macroscopic and histologic scores in the experimental model compared with colitic animals. In particular, we demonstrated that the treatment with GAGs reduced the accumulation of inflammatory cells in the colonic lamina propria, the rate of epithelial apoptosis, the amount of collagen deposition, and the local production of TNF-α, VEGF, and TGF-β.

In this study, colitic animals showed elevated percentages of T-cells and macrophages in the intestinal lamina propria, and the numbers were significantly reduced by heparin and heparin analogues. Therefore, colitis attenuation observed after GAGs could be probably attributed to the reduction in the number of inflammatory cells in the colon. Because the rate of apoptosis in the lamina propria remained relatively unchanged after treatment with GAGs, it seems unlikely that apoptosis induction would constitute a primary mechanism of action of GAGs in TNBS-induced colitis. Hence, we hypothesize that the lower number of cells infiltrating the lamina propria actually reflects the inhibition of cell migration into the intestine. In fact, it has been demonstrated that heparin and heparin analogues inhibit inflammation by blocking P-selectin-mediated leukocyte immigration (42). As a result, a reduction in the production of inflammatory mediators, including cytokines such as TNF-α, would be expected to occur.

TNF-α is a crucial player for the establishment of the inflammatory process of CD as suggested by the increased levels of the cytokine observed in the plasma and stools of patients with active disease (43, 44). TNF-α induces activation of the NF-κB and MAP kinase signaling pathways, leading to an increase in the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, and an augment in lymphocyte and macrophage recruitment. In addition, TNF-α stimulates the production of metalloproteinases and collagen by myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in the intestinal mucosa, contributing to matrix degradation and fibrosis (45). Clinical studies have shown that TNF-α blockage constitutes a beneficial therapy for refractory luminal and fistulizing CD, and recently for refractory ulcerative colitis as well (46–49). Moreover, inhibitors of the NF-κB and p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways were shown to attenuate the inflammatory response in a murine model of CD (50).

In the present work, administration of GAGs dramatically reduced TNF-α as well as NF-κB and MAP kinase signaling pathways. In addition, a drastic reduction of epithelial cells apoptosis in TNBS-treated animals was also observed. These results corroborate literature data, indicating that TNF-α induces apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells (51) and strongly suggest that these glycans target directly or indirectly important effectors involved in colon inflammation.

The inhibitory effect of heparin analogues on LPS-mediated production of TNF-α, may constitute another mechanism by which glycans can exert anti-inflammatory action. LPS-activation of macrophages occurs after LPS complexed with serum LPS-binding protein (LBP) binds receptor CD14, resulting in the activation of the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB (52, 53). In fact, the dose-dependent inhibitory effect on macrophage activation is probably a consequence of heparin interference with LPS binding to its receptor protein (54). Because in the TNBS-colitis model the disruption of the epithelial barrier leads to increased exposure of the mucosal immune system to gut microflora and bacterial products such as LPS (55), it is likely that the glycans act also upon earlier events upstream in the cascade of macrophage activation. Hence, given early in the course of an acute model of colitis, heparin treatment prevents the development of colitis, the priming phase of the induction of Th1 response.

TGF-β is a multifunctional cytokine capable of regulating the proliferation, differentiation and function of immune and non-immune cells (56). In CD, this cytokine induces the proliferation of fibroblasts and miofibroblasts and an increase in the synthesis of matrix components such as collagen and GAGs (57, 58) that have been shown to accumulate in the colonic tissue of patients with active CD. Although TGF-β is regarded as an anti-inflammatory cytokine, its abundant expression in IBD tissue is incapable of down regulating the immune response (59), probably because TGF-β fails to suppress NF-κB activation in gut inflammation (60). Here, we showed that treatment of TNBS-induced colitis with GAGs significantly reduced collagen deposition, probably as a consequence of TGF-β reduction.

It is also interesting to notice that GAGs administration restored the quantity and composition of endogenous colonic GAGs in TNBS-treated animals, which may reflect normalization of the extracellular matrix. A possible explanation for this effect could be attributed to GAGs blockage of heparanase. Heparanase is an endoglycosidase that degrades heparan sulfate proteoglycans, major components of the extracellular matrix and cell surfaces (61). Taking together the up-regulation of heparanase found in the colonic epithelium of IBD, and our previous observation of increased distribution of heparan sulfate within the inflamed colon of patients with CD (40), we speculate that anti-inflammatory effect of GAGs could also be mediated by their interaction with heparanase.

The expansion of the microvascular bed favors inflammation by allowing the influx of inflammatory cells, increase of nutrient supply and production of cytokines, chemokines, and metalloproteinases by activated endothelium (62, 44). Recent studies provided evidence that angiogenesis is involved in the pathogenesis of IBD. In fact, expression of the proangiogenic factor VEGF is augmented in intestinal mucosa of patients with active CD (39). In agreement with literature data, here we showed that exposure to TNBS resulted in a marked increase of VEGF production in the inflamed colon. Administration of GAGs reduced the growth factor levels to that of control animals, corroborating the idea that among the anti-inflammatory actions of heparins, an important role should be attributed to the interference with angiogenesis (63, 64).

Finally, interestingly, unfractionated mammalian heparin given subcutaneously produced a very effective anti-inflammatory effect in the model studied without causing any significant changes in the coagulation parameters and platelet counts. In addition, non-hemorrhagic heparin and DS obtained from the invertebrate S. plicata inhibited colon inflammation more efficiently than mammalian heparin, indicating that these compounds could be a potential alternative to heparin in the treatment of IBD.

This work was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Fundação de Amparo `a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), Fundação José Bonifácio (FUJB), Mizutani Foundation for Glycoscience (to M. S. G. P.).

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: IBD, inflammatory bowel diseases; CD, Crohn disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; GAG, glycosaminoglycan; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; ANOVA, analysis of variance; TNBS, trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; DS, dermatan sulfate; MAP, mitogen-activated protein; HS, heparan sulfate; CS, chondroitin sulfate.

References

- 1.Xavier, R. J., and Podolsky, D. K. (2007) Nature 448, 427-434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papadakis, K., and Targan, S. (2000) Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 6, 303-313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinecker, H., Steffen, M., Witthoeft, T., Pflueger, I., Schreiber, S., MacDermott, R., and Raedler, A. (1993) Clin. Exp. Immunol. 94, 174-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiocchi, C. (1998) Gastroenterology 115, 182-205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Podolsky, D. (2002) N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 417-429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macdonald, T. T., and Monteleone, G. (2005) Science 307, 1920-1925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atreya, I., Atreya, R., and Neurath, M. F. (2008) J. Intern. Med. 263, 591-596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schurmann, G. M., Bishop, A. E., Facer, P., Vecchio, M., Lee, J. C., Rampton, D. S., and Polak, J. M. (1995) Gut. 36, 411-418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andoh, A., Tsujikawa, T., Hata, K., Araki, Y., Kitoh, K., Sasaki, M., Yoshida, T., and Fujiyama, Y. (2005) Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100, 2042-2048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strober, W., Fuss, I. J., and Blumberg, R. S. (2002) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20, 495-549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roden, L., Ananth, S., Campbell, P., Curenton, T., Ekborg, G., Manzella, S., Pillion, D., and Meezan, E. (1992) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 313, 1-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsh, J., Warkentin, T. E., Shaughnessy, S. G., Anand, S. S., Halperin, J. L., Raschke, R., Granger, C., Ohman, E. M., and Dalen, J. E. (2001) Chest 119, Suppl. 1, 64S-94S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papa, A., Danese, S., Gasbarrini, A., and Gasbarrini, G. (2000) Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 14, 1403-1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elsayed, E., and Becker, R. C. (2003) J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 15, 11-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaffney, P. R., Doyle, C. T., Gaffney, A., Hogan, J., Hayes, D. P., and Annis, P. (1995) Am. J. Gastroenterol. 90, 220-223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folwaczny, C., Wiebecke, B., and Loeschke, K. (1999) Am. J. Gastroenterol. 94, 1551-1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ang, Y. S., Mahmud, N., White, B., Byrne, M., Kelly, A., Lawler, M., McDonald, G. S., Smith, O. P., and Keeling, P. W. (2000) Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 14, 1015-1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulman, S., Beyth, R., Kearon, C., and Levine, M. (2008) Chest 133, 257S-298S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos, J., Mesquita, J., Belmiro, C., da Silveira, C., Viskov, C., Mourier, P., and Pavao, M. (2007) Thromb. Res. 121, 213-223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cardilo-Reis, L. C. M., Silveira, C. B., and Pavao, M. S. (2006) Braz J. Med. Biol. Res. 39, 1409-1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pavao, M. (2002) An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 74, 105-112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vicente, C., Zancan, P., Peixoto, L., Alves-Sa, R., Araujo, F., Mourao, P., and Pavão, M. S. (2001) Thromb. Haemost. 86, 1215-1220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavao, M., Aiello, K., Werneck, C., Silva, L., Valente, A., Mulloy, B., Colwell, N., Tollefsen, D., and Mourao, P. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27848-27857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavao, M., Mourao, P., Mulloy, B., and Tollefsen, D. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 31027-31036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Live Sciences, National Research Council (1996), National Academic Press, Washington, D.C.

- 26.Hahm, K., Im, Y., Parks, T., Park, S., Markowitz, S., Jung, H., Green, J., and Kim, S. (2001) Gut 49, 190-198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolber, P., and Spach, M. (1987) Stain Technol. 62, 23-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolber, P., and Spach, M. (1993) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 41, 465-469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bitter, T., and Muir, H. M. (1962) Anal. Biochem. 4, 330-334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schreiber, S., Nikolaus, S., Hampe, J., Hamling, J., Koop, I., Groessner, B., Lochs, H., and Raedler, A. (1999) Lancet 353, 459-461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyriakis, J. M., and Auruch, J. (2001) J Physiol. Rev. 81, 807-869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dignass, A., and Podolsky, D. (1996) Exp. Cell Res. 225, 422-429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dignass, A. V., Stow, J. L., and Babyatsky, M. W. (1996) Gut 38, 687-693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawrance, I., Maxwell, L., and Doe, W. (2001) Inflamm Bowel Dis. 7, 226-236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawrance, I., Maxwell, L., and Doe, W. (2001) Inflamm Bowel Dis. 7, 16-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kevil, C., Payne, D., Mire, E., and Alexander, J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15099-15103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim, I., Moon, S., Kim, S., Kim, H., Koh, Y., and Koh, G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 7614-7620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsiolakidou, G., Koutroubakis, I., Tzardi, M., and Kouroumalis, E. (2008) Dig. Liver Dis. 40, 673-679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koutroubakis, I., Tsiolakidou, G., Karmiris, K., and Kouroumalis, E. (2006) Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 12, 515-523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belmiro, C., Souza, H., Elia, C., Castelo-Branco, M., FR, S., Machado, R., and MS, P. (2005) Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 20, 295-304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baumgart, D. C., and Sandborn, W. J. (2007) Lancet 369, 1641-1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, L., Brown, J., Varki, A., and Esko, J. (2002) J. Clin. Investig. 110, 127-136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murch, S., Lamkin, V., Savage, M., Walker-Smith, J., and MacDonald, T. (1991) Gut 32, 913-917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braegger, C., Nicholls, S., Murch, S., Stephens, S., and MacDonald, T. (1992) Lancet 339, 89-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Sabatino, A., Pender, S., Jackson, C., Prothero, J., Gordon, J., Picariello, L., Rovedatti, L., Docena, G., Monteleone, G., and Rampton, D. (2007) Gastroenterology 133, 137-149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Dullemen, H. M., van Deventer, S. J. H., Hommes, D. W., Bijl, H. A., Jansen, J., Tytgat, G. N., and Woody, J. (1995) Gastroenterology 109, 129-135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Targan, S., Hanauer, S., van Deventer, S., Mayer, L., Present, D., Braakman, T., DeWoody, K., Schaible, T., and Rutgeerts, P. (1997) N. Engl. J. Med. 337, 1029-1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sands, B. E., Anderson, F. H., Bernstein, C. N., Chey, W. Y., Feagan, B. G., Fedorak, R. N., Kamm, M. A., Korzenik, J. R., Lashner, B. A., Onken, J. E., Rachmilewitz, D., Rutgeerts, P., Wild, G., Wolf, D. C., Marsters, P. A., Travers, S. B., Blank, M. A., and van Deventer, S. J. (2004) N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 876-885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rutgeerts, P., Sandborn, W. J., Feagan, B. G., Reinisch, W., Olson, A., Johanns, J., Travers, S., Rachmilewitz, D., Hanauer, S. B., Lichtenstein, G. R., de Villiers, W. J., Present, D., Sands, B. E., and Colombel, J. F. (2005) N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 2462-2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hollenbach, E., Vieth, M., Roessner, A., Neumann, M., Malfertheiner, P., and Naumann, M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14981-14988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Begue, B., Wajant, H., Bambou, J., Dubuquoy, L., Siegmund, D., Beaulieu, J., Canioni, D., Berrebi, D., Brousse, N., and Desreumaux, P. (2006) Gastroenterology 130, 1962-1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perera, P. Y., Vogel, S. N., Detore, G. R., Haziot, A., and Goyert, S. M. (1997) J. Immunol. 158, 4422-4429 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brass, D. M., Hollingsworth, J. W., McElvania-Tekippe, E., Garantziotis, S., Hossain, I., and Schwartz, D. A. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 293, L77-L83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dziarski, R., and Gupta, D. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 2100-2110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Te Velde, A. A. Verstege, M. I., and Hommes, D. W. (2006) Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 12, 995-999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Letterio, J., and Roberts, A. (1998) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16, 137-161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beddy, D., Watson, W., Fitzpatrick, J., and O'Connell, P. (2004) J. Am. Coll Surg. 199, 234-242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Theiss, A., Simmons, J., Jobin, C., and PK, L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36099-36109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Babyatsky, M. W., Rossiter, G., and Podolsky, D. K. (1996) Gastroenterology 110, 975-984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Monteleone, G., Pallone, F., and MacDonald, T. T. (2004) Trends Immunol. 25, 513-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dempsey, L. A., Brunn, G. J., and Platt, J. L. (2000) Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 349-351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Firestein, G. (1999) J. Clin. Investig. 103, 3-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khorana, A. A., Sahni, A., Altland, O. D., and Francis, C. W. (2003) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 2110-2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marchetti, M., Vignoli, A., Russo, L., Balducci, D., Pagnoncelli, M., Barbui, T., and Falanga, A. (2008) Thromb Res. 121, 637-645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]