Abstract

We measured brain activity using event-related fMRI as participants recalled answers to 160 questions about news events that had occurred during the past 30 years. Guided by earlier findings from patients with damage limited to the hippocampus who were given the same test material, we looked for regions that exhibited gradually decreasing activity as participants recalled memories from 1–12 years ago and a constant level of activity during recall of more remote memories. Regions in the medial temporal lobe exhibited a decrease in brain activity in relation to the age of the memory (hippocampus, temporopolar cortex, and amygdala). Regions in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and parietal lobe exhibited the opposite pattern. The findings for all of these regions were unrelated to the richness of the memories, to how well test questions were remembered later (encoding for subsequent memory), nor to how frequently semantic memories were accompanied by personal, episodic recollections. Last, activity in a different group of regions (perirhinal cortex, parahippocampal cortex, and inferior temporal gyrus) was associated with how well the test questions were subsequently remembered. The results support the idea that medial temporal lobe structures play a time-limited role in semantic memory.

Keywords: learning and memory, hippocampus, fMRI, imaging, amnesia, memory

Introduction

Early descriptions of memory impairment emphasized that the recent past is typically more vulnerable to disruption than the remote past (Ribot, 1881; Russell and Nathan, 1946). Subsequently, it became possible to relate these observations to neuroanatomy and especially to the functions of the hippocampus. Memory-impaired patients with circumscribed, bilateral lesions of the hippocampus exhibit both impaired new learning (anterograde amnesia) and temporally graded retrograde amnesia covering a period of a few years before the onset of memory impairment (Kapur and Brooks, 1999; Manns et al., 2003). For example, in a semantic memory test involving news events that occurred 1–30 years before the onset of amnesia, memory for remote events was intact (11–30 years before amnesia), but memory for events that occurred recently was impaired in a graded manner (1–10 years before amnesia) (Manns et al., 2003; Bayley et al., 2006).

A number of brain imaging studies have also investigated how recent and remote semantic memory are represented in the healthy brain, but findings from these studies are mixed. Some studies, in keeping with the findings from memory-impaired patients, found more activity in hippocampus or entorhinal cortex during recollection of recent semantic memories than during the recollection of remote semantic memories (Haist et al., 2001; Douville et al., 2005; Takashima et al., 2006). Yet other studies found no difference in the activity in these structures during recollection of recent and remote semantic memories (Maguire et al., 2001; Maguire and Frith, 2003; Bernard et al., 2004).

Guided by the findings from patients, we have assessed brain activity while participants recalled semantic memories from seven different time periods covering the past 30 years. We used the same test materials (News Events Test) that had revealed temporally limited retrograde amnesia in memory-impaired patients with hippocampal lesions (Manns et al., 2003; Bayley et al., 2006), and we looked for brain regions in which activity during recall of 1- to 30-year-old memories conformed to the function suggested by the findings from patients. Specifically, we looked for regions that exhibited gradually decreasing activity as participants recalled memories from 1–12 years ago and a constant level of activity during recall of more remote memories (from 13–30 years ago). We also looked for brain regions that exhibited the opposite pattern of activity (i.e., greater activity during recall of remote memories) because of evidence that the neocortex becomes increasingly important as time passes after learning (Bontempi et al., 1999; Frankland et al., 2004; Maviel et al., 2004; Takashima et al., 2006; Squire and Bayley, 2007).

The study of recent and remote memory with neuroimaging presents a number of challenges. For example, when participants retrieve memories from the past they are also incidentally encoding the questions that they are asked and the recollections that they produce. Accordingly, during retrieval of past memories brain activity related to encoding might mask or override brain activity related to retrieval of recent versus remote memory. In addition, the memories that are retrieved from different time periods might differ not only in age but also in their vividness or richness. Accordingly, a finding of greater brain activity for recent than for remote memories might be related more to the greater vividness or richness of recent memories than to their recency per se (Gilboa et al., 2004). Last, a finding of greater brain activity for recent than for remote memories might be related not to differences in the age of semantic memories, but to a tendency for more recent semantic memories to be associated with personal, episodic recollections.

Our study addressed these issues by directly evaluating the effect of memory age independently of the success of encoding the test questions. We also evaluated the effect of memory age independently of the effect of memory richness. Last, we asked whether recent memories (but not remote memories) tended to be associated with episodic recollections.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Fifteen healthy participants (7 males) were recruited from the University of California San Diego community. Participants averaged 56.4 ± 1.0 years of age (range = 51–64 years). Each participant qualified for the study by scoring at least 40% correct on a pretest of 10 news events questions that were not used in the fMRI scanning session. One additional participant was scanned but did not recall a sufficient number of answers to the news event questions to be included in the analyses.

Background

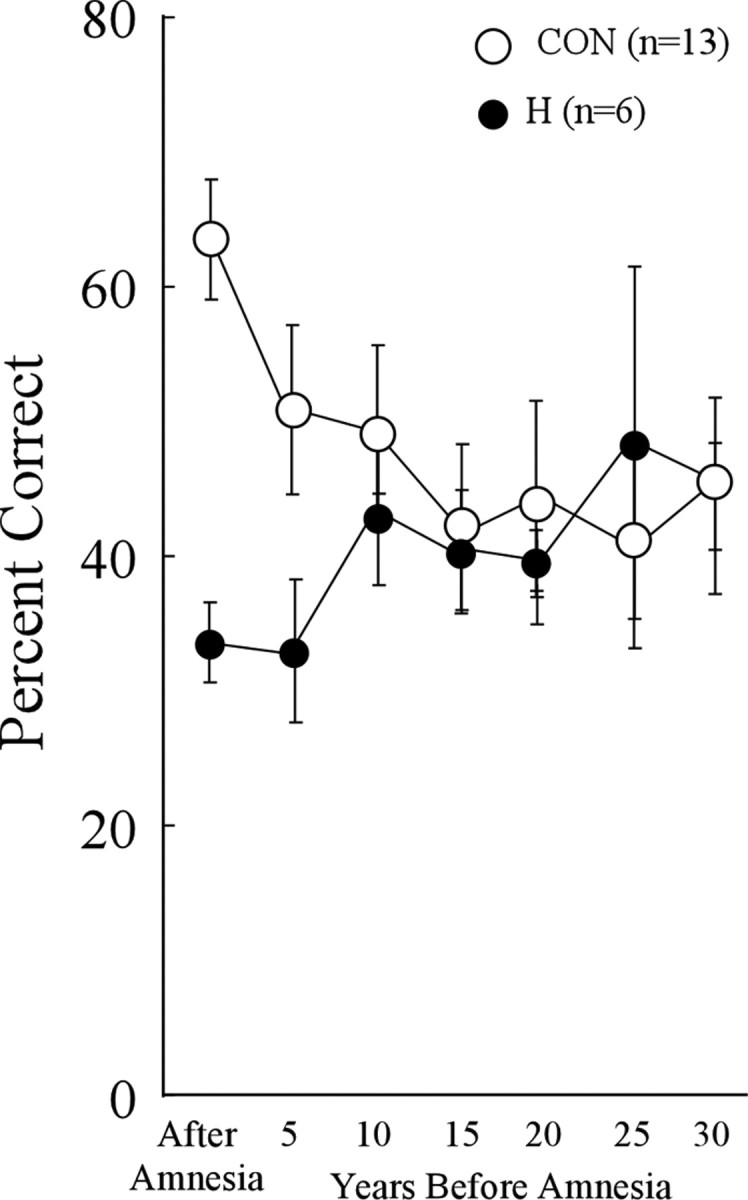

Evidence from memory-impaired patients with damage thought to be limited to the hippocampus indicates that the hippocampus plays a time-limited role in semantic memory. Figure 1 illustrates the main findings from the most recent of these studies (Bayley et al., 2006) and shows that a time span of 30 years is more than sufficient to document these features of temporally graded retrograde amnesia.

Figure 1.

Recall performance by patients with limited hippocampal lesions (H) and controls (CON) on a test of 279 news events that occurred between 1951 and 2005. The scores for each patient, and for two to three controls matched to each patient, were analyzed according to the year in which the patient became amnesic. The data point at 5 represents 1–5 years before amnesia, the point at 10 represents 6–10 years before amnesia, and so on. Error bars show SEM. The patients exhibited temporally limited retrograde amnesia covering several years before the onset of amnesia. This figure is modified from Bayley et al. (2006), their Figure 2.

Materials and procedure

While being scanned, participants were given a modified version of the News Events Test described previously (Bayley et al., 2006). Tests of past public events, like this one, are sufficiently specific that it is difficult to answer the questions correctly unless an individual has lived through the time period in question (Warrington and Silberstein, 1970; Squire, 1974). The test involved 160 questions about events that had occurred during the past 30 years [from 1976 to 2005; e.g., “What tire manufacturer recalled thousands of tires?” (Firestone)]. Of these, 126 were taken from the test given previously (Bayley et al., 2006). Thirty-four additional questions were added to obtain 20 questions for each of eight time periods (1976–1980, 1981–1985, 1986–1990, 1991–1993, 1994–1996, 1997–1999, 2000–2002, and 2003–2005; the two most remote time periods were subsequently combined into a single 10 year period). When the data in Figure 1 were rescored on the basis of the same 160 questions that were used in the present study (all but one patient and two controls in Fig. 1 were also given the 34 new questions), the same pattern of findings was obtained. Across all 14 data points, the mean difference between the scores for the 279 items used in Figure 1 and the scores for the 160 items used in the present fMRI study was 2.6% (maximum = 4%).

During scanning, which occurred between June 2006 and March 2007, the 160 questions were presented one at a time for 6 s. The questions were arranged in 16 blocks of 10 questions each, such that each block contained 10 questions about just one time period. Each participant was given a unique order of blocks and a unique order of questions within each block with the constraint that both the first eight blocks and the second eight blocks covered all eight time periods. The blocks of questions were presented in four scanning runs with a 2 min pause after every four blocks (40 questions). The data of principal interest concerned the brain activity associated with correctly answered news event questions. Baseline trials (making odd–even judgments for a single digit; 2 s each) were placed throughout the runs (7 before each block of 10 questions, 15 within each block, and 7 after each block). This task is known to result in relatively little medial temporal lobe activity (Stark and Squire, 2001). The news event questions were presented in an event-related manner such that each question within a block was followed by 0, 1, 2, or 3 baseline trials. Because incorrectly answered questions were not included in the data analysis, the effective mean intertrial interval for correctly answered news event questions (which consisted of baseline trials and incorrectly answered questions) was 10.8 s (range = 2–76 s). The mean intertrial interval ranged from 8.9 s for the most recent time period to 12.8 s for the most remote time period. Stimulus presentation and recording of behavioral data were controlled by E-prime (Psychology Software Tools).

When each question appeared, participants were asked to silently recall the answer and to indicate by button press, during the final 2 s of the 6 s time allotted for each question, whether they knew the answer or not. After scanning (5–10 min delay), participants answered three questions about each news event item that had been presented during scanning. The order of the time periods queried about was the same as the order of the time periods presented during scanning. Participants had as much time as they needed to answer each question. The first question assessed how well participants had encoded the information that was part of each test item (encoding). The second question asked for the answer to the news event question (recall accuracy). The third question asked participants to judge how much they knew about each news event (richness), because recent memories may be more vivid or contain more details than remote memories (Niki and Luo, 2002; Addis et al., 2004; Gilboa et al., 2004). The first and third questions gave us the opportunity to distinguish effects related to how well participants remembered the test items and effects related to the quality of each memory from effects related to the time period in which the news event occurred. Thus, encoding and richness were used as covariates in the analysis of effects related to the time period in which the news event occurred.

Subsequent memory for the content of the news event questions.

Participants were asked to indicate which of three specific topics they had been asked about during scanning. For example, for the item “The Gates was an art exhibit that took place in which U.S. city?”, participants were asked, “Which of these topics were you asked about in the scanner? 1) where ‘The Gates’ art exhibit took place; 2) what ‘The Gates’ art exhibit entailed; and 3) who the artist of ‘The Gates’ art exhibit was.”

Recall accuracy.

The news event question was next presented in its original form, and participants were asked to answer the question orally. There was good agreement between recall accuracy on this test and the responses made during scanning. Specifically, when participants answered a question correctly in the postscanning test, they had indicated in the scanner that they knew that answer 90% of the time (this correspondence did not vary with the age of the recalled memory). Conversely, when participants had indicated in the scanner that they knew the answer, they answered the question correctly in the postscanning test 71% of the time. Analysis of the fMRI data was based on the questions that were correctly answered according to the postscanning test.

Richness.

The richness of the memories was assessed in two ways. First, participants indicated on a 1–5 scale how much information they had available about the topic addressed by the news event question. In addition, 12 of the 15 participants returned later (13.5 months on average) for an extended 1.5–6 h interview in which they related what they knew about the correctly remembered events from four different time periods: 1976–1985, 1991–1993, 1997–1999, and 2003–2005. For each time period, we calculated the mean number of individual facts that could be related for each news event.

Episodic memory.

To evaluate whether knowledge about past news events was associated with personal, autobiographical recollections, we also asked 12 of the 15 participants as part of the extended interview (see above) to describe any episodic memories that were associated with the correctly remembered events from four different time periods: 1976–1985, 1991–1993, 1997–1999, and 2003–2005. These could involve, for example, remembering where they were or what they were doing when they learned about the news event, or remembering some activity associated with the news event, such as talking to a friend about it. For each of the four time periods, we calculated the proportion of correctly remembered events that were linked to an episodic memory.

fMRI parameters and analysis

Imaging was performed with a 3T GE scanner at the Center for Functional MRI (University of California, San Diego). Functional images were acquired using a gradient-echo, echo-planar, T2*-weighted pulse sequence (TR = 2000, TE = 30, Flip angle = 90°). The first five images acquired were discarded to allow for T1 equilibration. Thirty-four sections covering the whole brain were acquired perpendicular to the long axis of the hippocampus (3.4 × 3.4 × 5 mm voxels). Following four functional runs (236 images/run), high-resolution (1 mm3) T1-weighted, fast spoiled gradient echo (FSPGR) anatomical images were collected for each participant.

Using the AFNI suite of programs (Cox, 1996), data from each run were reconstructed using field map correction, temporally aligned, and coregistered using a 3D registration algorithm. All four runs were then concatenated into a single file that included all 160 questions. Motion events, defined as images (±1 image) in which there were >0.3 degrees of rotation or 0.6 mm of translation in any direction, were eliminated from the analysis. On average, 1.7 images per participant were eliminated due to motion events (maximum: 6 images). Voxels outside of the brain were eliminated from the analysis by a threshold mask of the fMRI data.

For data analysis, deconvolution of the fMRI time series data was performed using two general linear models (GLM) that consisted of both motion vectors and behavioral vectors (3dDeconvolve; http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/pub/dist/doc/manual/Deconvolvem.pdf). Six vectors were created that coded for motion (three for translation and three for rotation), and two vectors were created that coded for first-order and second-order drift in the MR signal. Behavioral vectors were created that coded each news event question according to the following criteria: (1) in which of seven time periods the news event occurred [note that the two most remote time periods were combined into a single vector, 1976–1985 (see Results, Behavioral findings)]; and (2) encoding the content of the news event question: whether or not the specific content of each question was subsequently remembered or forgotten.

The first GLM consisted of behavioral vectors for each of the seven time periods so that we could determine the effect of a memory's age on brain activity. In this analysis, correctly and incorrectly answered questions from each time period were coded separately, as determined by recall accuracy in the postscanning test. Seven vectors coded for the correctly answered questions from each time period (mean intertrial interval = 10.8 s; range = 2–76 s). A single vector coded for all incorrectly answered questions. We used a single vector because there were only a few incorrect trials in some time periods such that each time period could not be analyzed separately. The second GLM consisted of two behavioral vectors, one for news event questions whose content was later remembered and one for news event questions whose content was later forgotten, as determined by the three-alternative postscanning test. This GLM allowed us to determine the effect on brain activity of how well the content of the test questions was subsequently remembered.

For each trial type (e.g., for each of the seven time periods), a fit coefficient (β coefficient) was generated for each image that was acquired during the expected hemodynamic response (0–20 s after trial onset; 10 images). The β coefficient represents the amplitude of activity versus baseline in each voxel. The β coefficients were summed over the expected hemodynamic response and taken as the estimate of the amplitude of the response to each trial type (relative to the digit task baseline).

Initial spatial normalization was accomplished using each participant's structural MRI scan to transform the data to the atlas of Talairach and Tournoux (1988). Each subject's functional data were also transformed to Talairach space, resampled to 2.5 mm3, and smoothed using a Gaussian filter (4 mm FWHM) that respected the anatomical boundaries of the several medial temporal lobe (MTL) regions defined for each individual participant (see below). Specifically, the smoothing was performed within each of the anatomically defined MTL regions, but smoothing was not extended beyond the edges of these regions to prevent activity from one region (e.g., parahippocampal cortex) from being blurred into another, adjacent region (e.g., hippocampus). The Talairach-transformed data were used in the whole-brain analyses.

The ROI-LDDMM alignment technique (Miller et al., 2005) was used to achieve better alignment and increase statistical power for the analysis of medial temporal lobe activity (Kirwan et al., 2007). Anatomical regions of interest were manually segmented in 3D on the Talairach-transformed anatomical images for the hippocampus and temporal polar, entorhinal, perirhinal, and parahippocampal cortices. Temporal polar, entorhinal, and perirhinal cortices were defined according to the landmarks described by Insausti et al. (1998a). The parahippocampal cortex was defined bilaterally as the portion of the parahippocampal gyrus caudal to the perirhinal cortex and rostral to the splenium of the corpus callosum (Insausti et al., 1998b). The anatomically defined ROIs for each individual participant were then used to normalize each subject's set of ROIs to a previously defined template using ROI-LDDMM (Kirwan et al., 2007). This transformation was then applied to each subject's functional data, and all MTL analyses were performed on the ROI-LDDMM transformed data.

Voxels that exhibited significant activity (p < 0.05, based on the statistical tests to be described next) were reported as spatially contiguous voxels (i.e., significant clusters) if they were larger than a minimum volume determined to be significant by Monte Carlo simulation (to correct for multiple comparisons). The minimum cluster sizes were 375 mm3 when the analyses were restricted to the MTL and 1766 mm3 when the analyses included the whole brain.

Brain activity related to the time period in which the news event occurred.

A regression analysis tested for the effect of the time period in which the news event occurred for both the whole brain and the MTL. Our expectation about the effect of time period on brain activity was guided by the impairment exhibited by patients on the News Events Test. Figure 1 summarizes lesion evidence that the hippocampus is important for recalling news events from the past several years but not for recalling more remote events. Accordingly, in the fMRI study for correctly answered news event questions we looked for regions that responded according to a function that matched the impairment exhibited by the patients. Specifically, we tested for regions with linearly decreasing activity across the four most recent time periods (1–12 years) and a constant level of activity across more remote time periods (13–30 years). The results were the same when we identified regions with decreasing activity across the three most recent time periods (1–9 years) and constant activity across the past 10–30 years.

A second, otherwise identical regression analysis was also performed with two covariates. The two covariates were the mean encoding accuracy for the content of the news event questions from each time period (percentage correct score) and the mean richness of memory for the news events from each time period (rating score from 1 to 5). In this way, the effect on brain activity of the time period in which the news events occurred could be evaluated independently of the effects of encoding new information and independently of the effects of the richness of each memory. The same analysis was also performed using the measure for richness derived from the interview (number of facts recalled about each event). [Richness values for time periods not assessed in the interview (1986–1990, 1994–1996, and 2000–2002) were calculated as the weighted average of the richness values from the adjacent time periods. Also, for the three participants who did not complete the interview, the richness scores from the 1–5 scale were used.]

A third regression analysis, otherwise identical to the first analysis, tested for linearly decreasing activity across all time periods (rather than linearly decreasing for only a few years and then flat). Our expectation was that brain regions in the MTL outside of the hippocampus might exhibit brain activity that decreased linearly with memory remoteness. This expectation was based on the observation that memory-impaired patients with damage extending beyond the hippocampus exhibit more severe and more prolonged retrograde amnesia than patients with limited hippocampal damage (Bayley et al., 2006; Bright et al., 2006).

Brain activity related to encoding the content of the news event questions.

A voxelwise t test (two-tailed) was performed for voxels in the whole brain and in the medial temporal lobe to compare activity levels (relative to baseline) for news event questions whose content was subsequently remembered versus news event questions whose content was subsequently forgotten, as determined by the three-alternative postscanning test (regardless of when the news event occurred). This analysis was performed to determine if brain regions involved in encoding new information were the same regions involved when participants retrieve past memories and/or if during retrieval of past memories brain activity related to encoding might mask or override brain activity related to retrieval of recent versus remote memory.

Results

Behavioral findings

Recall accuracy

News event recall decreased in relation to how long ago the event occurred (linear trend, F(1,14) = 13.9, p < 0.01). Note that the analysis of fMRI data was based on the news event questions that were answered correctly (60.4 ± 3.4% of the 160 questions; mean ± SEM). In this way, brain activity was assessed for material from seven different time periods that was remembered equally well (Fig. 2). Participants recalled an average of 13.6, 13.1, 11.9, 12.7, 12.2, 12.1, 11.3, and 21.1 events for the seven time periods (recent to remote, respectively; note that the number of questions answered correctly in the most remote time period was higher than in other time periods, because the most remote time period included 40 questions covering 10 years, whereas the other time periods included 20 questions covering 3–5 years).

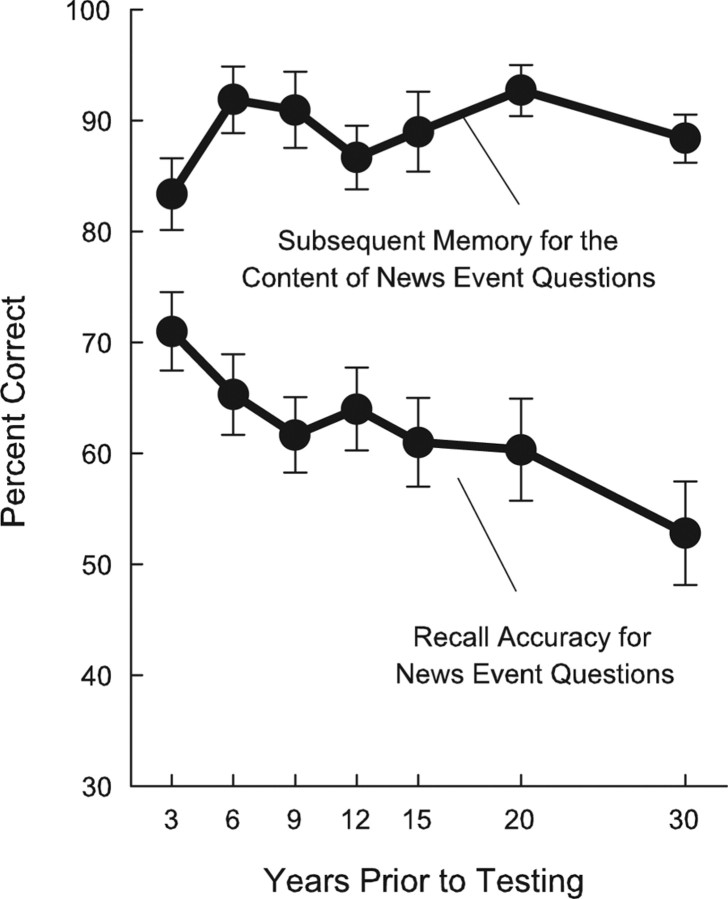

Figure 2.

The lower plot shows news event recall as a function of when the news event occurred. The upper plot shows how well participants remembered what they were asked about in the scanner (scores were based on the news events that were correctly recalled). The data point at 3 represents the score for events that occurred 1–3 years before testing, the point at 6 represents 4–6 years before testing, and so on. Error bars show SEM.

Note too that the difference between recent memory success and remote memory success was quite modest, and there was only a small difference across time periods with respect to the number of successfully recalled questions (i.e., there was forgetting as illustrated in Fig. 2, but the reduction in memory success across time periods was on the order of 15–20%). It is also notable that the reduction in memory success (and in the number of items available for analysis) across time periods was much less than the reduction in fMRI response from recent to remote time periods (35–107% reductions in fMRI signal) (see Fig. 4). Thus, the small differences in the numbers of correctly answered questions across time period (and, correspondingly, the small differences in intertrial interval) should have had minimal influence on the fMRI signal.

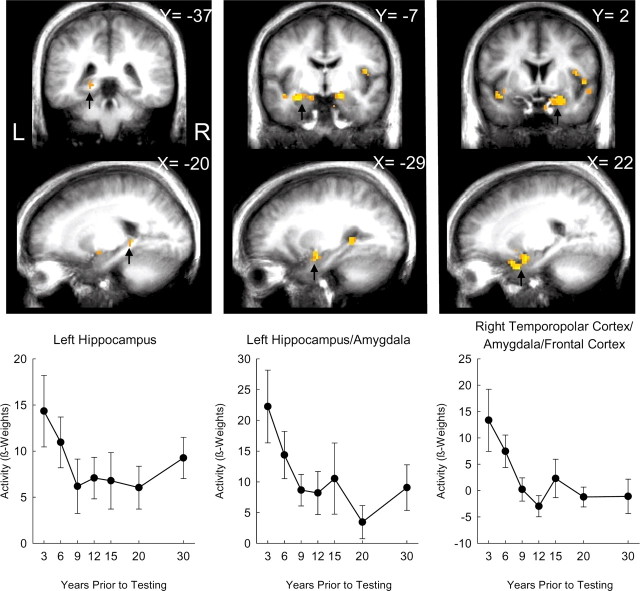

Figure 4.

Brain regions in the medial temporal lobe in which activity was related to the age of the memory. For regions identified by black arrows in the coronal sections (top row) and sagittal sections (middle row), activity levels (relative to baseline) are depicted for each time period covered by the test (bottom row). Error bars show SEM. X, Left/right Talairach coordinate; Y, anterior/posterior Talairach coordinate; L, left; R, right.

Subsequent memory for the content of the news event questions

To assess memory for what participants were asked about in the scanner, participants were given a three-alternative, multiple-choice test concerning the specific content of each news event question (Fig. 2). The score on this test was calculated only for the news event questions that were answered correctly. In this way, for each news event question that was answered correctly, one can also assess how well participants later remembered what they had been asked. Participants scored 88.9 ± 2.0% (mean ± SEM) correct on this test. As would be expected, memory for the content of the news event questions was unrelated to how long ago the news events occurred (p > 0.20).

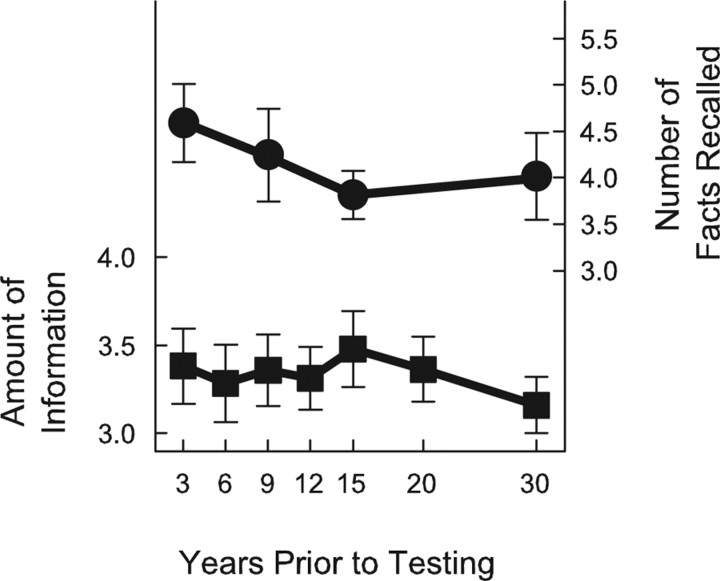

Richness

The ratings for richness of the memories were calculated for correctly answered news event questions. Ratings did not measurably decrease in relation to how long ago the event occurred, either when calculated on a 1–5 scale (p > 0.30) or when calculated on the basis of the number of facts recalled (p > 0.30) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Richness of memories for correctly answered news event questions as a function of the time period in which the news event occurred. Participants related the facts that they knew about each news event (circles) and also, in a different session, indicated on a 1–5 scale how much information they had about each news event (squares). Error bars show SEM.

Episodic memory

Participants reported an episodic memory in association with 20.6% of the correctly answered news events for the four time periods that were tested (range: 17.0–23.8%). The percentage of news events linked to an episodic memory did not decrease in relation to how long ago the news event occurred (p > 0.50).

fMRI findings

Brain regions in which activity related to the time period in which the news event occurred

Brain activity associated with the questions in each time period was compared with the function that matched the impairment exhibited by the patients (Fig. 1 and Materials and Methods). In the MTL, activity matching this function was identified in left posterior hippocampus, left anterior hippocampus/amygdala, and in a large temporal–frontal region that included the right temporopolar cortex, the amygdala, the insula, and the inferior frontal gyrus (Fig. 4, Table 1). The findings for the whole brain appear in Table 1.

Table 1.

Brain regions in which activity related to the age of the memory

| Brain region | Direction of effect | B.A. | Talairach coordinates |

Vol. (mm3) | Effect size (η2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | PA | IS | |||||

| Medial temporal lobe (p < 0.05 corrected, minimum cluster size = 375 mm3) | |||||||

| Right temporopolar Ctx./amygdala/insula/Inf. frontal G. | REC > REM | 30.4 | 8.4 | −9 | 8031 | 0.278 | |

| Left hippocampus/amygdala | REC > REM | −33.1 | 5.8 | −5.7 | 2375 | 0.267 | |

| Left hippocampus | REC > REM | −24.7 | −41.6 | 3.2 | 484 | 0.273 | |

| Whole brain (p < 0.05 corrected; minimum cluster size = 1766 mm3) | |||||||

| Left Inf. frontal G./temporopolar Ctx./insula/Sup. temporal G. | REC > REM | 47, 22 | −47.8 | 12.1 | −5.2 | 5156 | 0.284 |

| Bilateral rectal G./Inf. frontal G./subcallosal G. | REC > REM | 11 | 5.6 | 30.1 | −21.6 | 4359 | 0.284 |

| Left Inf. frontal G. | REC > REM | 45 | −56.4 | 12.7 | 21 | 3391 | 0.334 |

| Right Mid. frontal G. | REC > REM | 31.6 | 45.4 | 4.3 | 1875 | 0.297 | |

| Bilateral Med. frontal G./Sup. frontal G. | REC > REM | 9, 8 | −5.1 | 30.2 | 52.9 | 2188 | 0.261 |

| Right insula | REC > REM | 32.1 | 0.7 | 17.8 | 1812 | 0.290 | |

| Right insula/temporopolar Ctx./subcallosal G./amygdala/hippocampus | REC > REM | 30.1 | 7.1 | −10.8 | 5469 | 0.284 | |

| Right Inf. parietal lobule | REC > REM | 40 | 42.4 | −44.3 | 45.3 | 2328 | 0.292 |

| Bilateral brainstem/cerebellum | REC > REM | 3.6 | −42 | −25.8 | 11,297 | 0.297 | |

| Whole brain (p < 0.05 uncorrected; minimum cluster size = 313 mm3) | |||||||

| Right Sup. frontal G.* | REM > REC | 10 | 27.2 | 50.5 | 28.5 | 313 | 0.288 |

| Right Med. frontal G.* | REM > REC | 6 | 16.0 | 28.5 | 34.5 | 797 | 0.304 |

| Left Mid. frontal G. | REM > REC | 9 | −25.4 | 22.5 | 25.4 | 672 | 0.275 |

| Left Mid. frontal G. | REM > REC | 8 | −23.6 | 14.0 | 36.4 | 375 | 0.296 |

| Right Med. frontal G. | REM > REC | 6 | 13.7 | −6.4 | 56.0 | 407 | 0.284 |

| Right Sup. Temporal G. | REM > REC | 39 | 40.0 | −51.8 | 18.8 | 469 | 0.268 |

| Left Mid. Temporal G.* | REM > REC | −34.0 | −63.2 | 19.5 | 532 | 0.285 | |

| Right precuneus/cuneus* | REM > REC | 19 | 26.2 | −83.7 | 36.1 | 1016 | 0.265 |

Inf., Inferior; Mid., middle; Sup., superior; Med., medial; Ctx., cortex; G., gyrus; B.A., Brodmann area; Vol., volume; REC, recent memories; REM, remote memories; LR, left/right; PA, posterior/anterior; IS, inferior/superior. Talairach coordinates indicate the center of mass of each cluster. Asterisks, also illustrated in Figure 5.

Two other factors that could have influenced these findings were (1) how well the questions from different time periods were subsequently remembered; and (2) the richness of the memories from different time periods. Neither encoding success nor richness differed across time period (see above). Nevertheless, we performed a separate analysis (and found the same regions illustrated in Fig. 4) when the effects of encoding new information and the effects of richness (whether measured by the 1–5 scale or by the number of facts recalled) were included as covariates in a regression analysis. Thus, neither the findings from the MTL analysis (Fig. 4) nor the findings from the whole brain analysis were influenced by the ability to subsequently remember the test questions or by the richness of the memories.

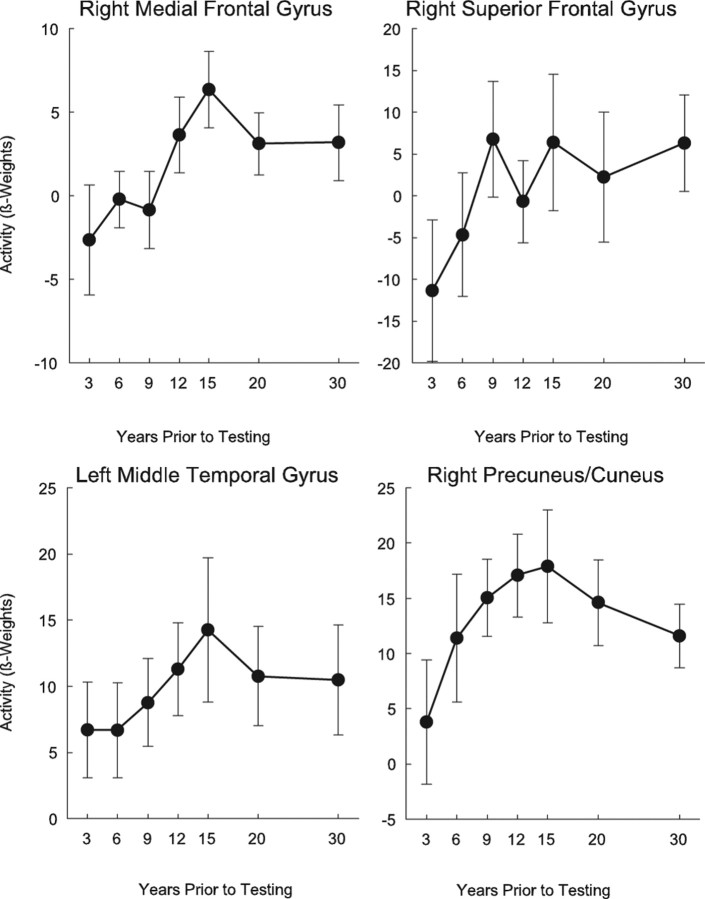

There is evidence that as memories become more remote, activity in the neocortex increases as activity in the hippocampus decreases (Bontempi et al., 1999; Frankland et al., 2004; Maviel et al., 2004; Takashima et al., 2006). To locate such activity, regions were identified that were negatively correlated with the pattern of impairment exhibited by the patients. That is, we looked for regions that exhibited linearly increasing activity across the four most recent time periods (1–12 years), and a constant level of activity across more remote time periods (13–30 years). No regions with these characteristics were found in the MTL. In the whole brain, regions were identified in the frontal lobe, lateral temporal lobe, and parietal lobe (Fig. 5, Table 1). Note that activity in these regions should be interpreted with caution because a less stringent threshold was used to detect them (p < 0.05 uncorrected, cluster sizes = 313–1016 mm3).

Figure 5.

Brain regions in the frontal, parietal, and lateral temporal lobes in which activity increased with the age of the memory (also see Table 1, bottom section).

Finally, brain activity in the MTL associated with the questions in each time period was compared with a function that linearly decreased across all time periods. No such regions were identified in the hippocampus. However, regions were identified in the left temporopolar cortex (−35.7, 13, −24.3; 984 mm3), left amygdala/entorhinal cortex (−27.2, −4.4, −16.2; 609 mm3), and a large temporal–frontal region that included the right temporopolar cortex, the entorhinal cortex, the amygdala, and the inferior frontal gyrus (27.6, 12.7, −18.2; 2406 mm3). Note that the large temporal–frontal cluster overlapped, in part, with a cluster in the analysis reported above (Table 1).

We next asked whether the clusters identified in our earlier analysis (Table 1, medial temporal lobe REC > REM) responded differently than the clusters just described, which were identified by a linear function. Specifically, we compared the average brain activity (β coefficients) across time periods within each of the three medial temporal lobe clusters in Table 1 (REC > REM) to the average brain activity across time periods within each of the three clusters just described (cluster × time period ANOVAs). Several of the cluster × time period interactions were significant. The left hippocampus cluster (Table 1) responded differently across time periods than the just-described cluster in the left amygdala/entorhinal cortex (p < 0.05). In addition, the left hippocampus/amygdala cluster (Table 1) responded differently across time periods than all three clusters just described (ps < 0.05). Finally, the temporal–frontal cluster (Table 1) responded differently across time periods than the right temporopolar cortex cluster just described (p < 0.05).

Brain regions in which activity related to the success of encoding the content of the news event questions

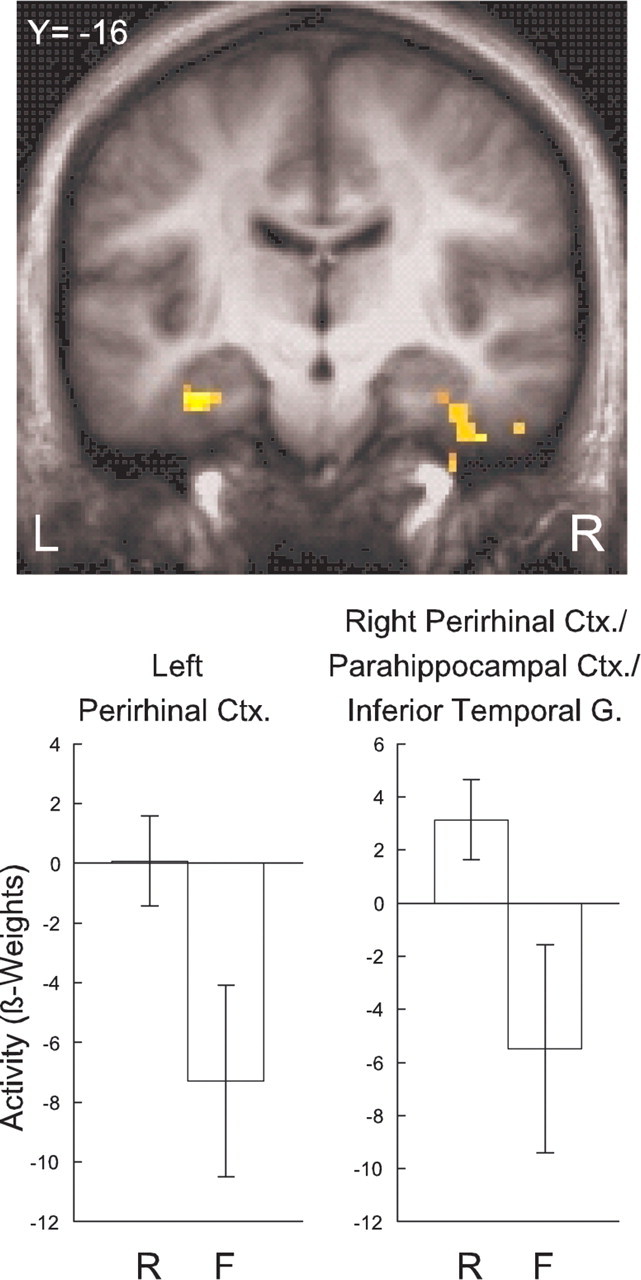

Last, activity associated with questions whose content was subsequently remembered was compared with activity associated with questions whose content was subsequently forgotten. In the MTL, regions in perirhinal cortex bilaterally predicted subsequent memory accuracy (Fig. 6, Table 2). The right perirhinal region extended into the parahippocampal cortex and inferior temporal gyrus. Notably, these regions were distinct from the regions in which activity related to the time period in which the news event occurred. The findings for the whole brain appear in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Brain regions in the medial temporal lobe in which activity was related to subsequent memory for the content of the news event questions. Regions were identified in left perirhinal cortex and in a region including right perirhinal cortex, parahippocampal cortex, and the inferior temporal gyrus. Error bars show SEM. Top, Y, Anterior/posterior Talairach coordinate; L, left; R, right. Bottom, R, content that was subsequently remembered; F, content that was subsequently forgotten.

Table 2.

Brain regions in which activity related to the success of encoding the test questions into memory

| Brain region | Direction of effect | B.A. | Talairach coordinates |

Vol. (mm3) | Effect size (η 2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | PA | IS | |||||

| Medial temporal lobe (p < 0.05 corrected, minimum cluster size = 375 mm3) | |||||||

| Right perirhinal/parahippocampal Ctx./Inf. temporal G. | R > F | 20 | 40.9 | −13.1 | −29.9 | 1531 | 0.306 |

| Left perirhinal Ctx. | R > F | −34.8 | −18.6 | −19.3 | 562 | 0.316 | |

| Whole brain (p < 0.05 corrected; minimum cluster size = 1766 mm3) | |||||||

| Right Inf. frontal G./temporopolar Ctx. | R > F | 47 | 2.3 | 23.1 | 11.7 | 6984 | 0.301 |

| Bilateral Sup. parietal lobule/precuneus | R > F | 7 | −3.7 | −52.1 | 67.4 | 2438 | 0.303 |

| Left postcentral G./Inf. parietal lobule | R > F | 40 | −36.3 | −28.9 | 53.7 | 2312 | 0.303 |

| Right parahippocampal Ctx./Inf. temporal G. | R > F | 20 | 43.1 | −13.3 | −28.1 | 1875 | 0.322 |

| Right Inf. temporal G./fusiform G./Mid. occipital G. | R > F | 19 | 48.3 | −62.3 | −11.2 | 3609 | 0.288 |

| Bilateral dorsomedial/pulvinar N. thalamus | R > F | −2.3 | −23.1 | 11.7 | 6984 | 0.301 | |

| Bilateral cerebellum/lingual G. | R > F | 3.6 | −84 | −16.3 | 3641 | 0.297 | |

Inf., Inferior; Mid., middle; Sup., superior; Ctx., cortex; G., gyrus; N., nuclei; B.A., Brodmann area; Vol., volume; R, news event questions whose content was subsequently remembered; F, news event questions whose content was subsequently forgotten; LR, left/right; PA, posterior/anterior; IS, inferior/superior. Talairach coordinates indicate the center of mass of each cluster.

Discussion

We searched for brain regions in which activity during the recall of past news events varied in relation to the age of the memory (1–30 years). Guided by findings from patients with damage limited to the hippocampus who were given many of the same test questions, we looked for regions that exhibited gradually decreasing activity as participants recalled memories from 1–12 years ago and a constant level of activity during recall of more remote memories (13–30 years ago). Within the medial temporal lobe, the left hippocampus, the right temporopolar cortex, and the left and right amygdala exhibited activity that conformed to this function (Fig. 4). Regions in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and parietal lobe exhibited the opposite pattern. That is, brain activity in these regions increased linearly with the age of recently recalled memories and remained at a constant level for recall of more remote memories. In addition, activity in bilateral perirhinal cortex, right parahippocampal cortex, and right inferior temporal gyrus was associated with how well the test questions were subsequently remembered (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the regions in the medial temporal lobe that responded during recall according to the age of the memory were different from the regions that responded during recall according to how well the test questions were subsequently remembered. This finding shows that the task of acquiring information about question content (presumably involving short-lived, unimportant facts) engages different medial temporal lobe regions than the task of recollecting past news events (presumably involving more important and long-lived facts).

In addition to the age of the memory, we also evaluated three other factors that might have contributed to the findings in the medial temporal lobe. Thus, neither the richness of the memories that were recalled nor how well the test questions were subsequently remembered was related to the time period in which the news events occurred (Figs. 2, 3). Moreover, when the richness of the memories and subsequent memory for the test questions were included as covariates in the fMRI analysis, the findings in the medial temporal lobe (as identified in Fig. 4) were unchanged. Last, the number of semantic memories that were associated with a personal, episodic recollection was not related to the age of the memory. Thus, the decrease in activity in the medial temporal lobe during recall of more remote memories could not have occurred because of a tendency for more recent semantic memories to be associated with episodic recollections.

Because participants answered more questions correctly for recent time periods than for remote time periods, correctly answered questions were more frequent (and more closely spaced) in recent time periods than in more remote time periods. Specifically, the mean intertrial interval for correctly answered questions was 8.9 s in the most recent time period and 12.8 s in the most remote time period (range = 2–76 s). These intertrial intervals were sufficiently long and sufficiently variable, such that the small differences in the mean intertrial interval across time periods should have had little effect on estimating the fMRI response (for further discussion, see Materials and Methods and Results, Behavioral findings).

Studies of patients with hippocampal lesions suggest that the hippocampus is essential for the formation and maintenance of semantic memory for a period of a few years after learning (Kapur and Brooks, 1999; Manns et al., 2003; Bayley et al., 2006). The present study was designed on the basis of these earlier findings. Using the same test material as in Bayley et al. (2006), we sampled news event memory across seven different time periods that spanned the past 30 years. With this approach, we identified regions in the hippocampus, amygdala, and temporopolar cortex in which activity during recall related to the age of the memory across the same time periods suggested from the studies with patients. These findings demonstrate the utility of carrying out fMRI studies in conjunction with lesion studies, and they provide convergent evidence for the idea that the hippocampus has a time-limited role in the formation and maintenance of memory.

Patients with damage to the hippocampus together with damage to the adjacent cortex (parahippocampal gyrus) exhibit more extensive retrograde amnesia than what is observed after damage to the hippocampus alone (Bayley et al., 2006; Bright et al., 2006). In this circumstance, retrograde amnesia for news events can cover several decades rather than only a few years. In accordance with this observation, we found brain regions in the parahippocampal gyrus (bilateral entorhinal cortex and bilateral temporopolar cortex) that exhibited a gradual decrease in brain activity across all time periods. This pattern is consistent with the idea that regions outside the hippocampus are involved in the recall of semantic memories for a longer period of time than the hippocampus proper.

In addition to parahippocampal gyrus, other regions in neocortex also exhibited gradually decreasing activity as the age of the memory increased (Table 1; REC > REM). These observations might be related to qualitative changes in the nature of memory representations as time passes after learning (e.g., reduced availability and loss of contextual information).

Imaging studies in humans and animals have identified regions of neocortex in which activity is greater during recall of remote memories than during recall of recent memories, even when activity in hippocampus exhibits the opposite pattern (Bontempi et al., 1999; Frankland et al., 2004; Maviel et al., 2004; Takashima et al., 2006). We also identified brain regions that exhibited more activity during recall of remote memories than during recall of recent memories. There were no regions with this pattern of activity in the medial temporal lobe, but regions in the frontal, lateral temporal, and parietal cortex did exhibit increases in activity that were related to the age of the memory. It has been proposed that memory initially depends on both the hippocampus and neocortex. As the hippocampus becomes less important, gradual changes in neocortex increase the complexity, distribution, and connectivity among multiple cortical regions (McClelland et al., 1995; Squire and Alvarez, 1995; Frankland and Bontempi, 2005). An additional way to understand the increasing involvement of some cortical areas, especially frontal cortex, as time passes is that older memories require more strategic, effortful search (Wheeler et al., 1995; Buckner and Wheeler, 2001; Rudy et al., 2005).

Other studies have also examined brain activity during recall of recent and remote semantic memory across a span of many years (Haist et al., 2001; Maguire et al., 2001; Maguire and Frith, 2003; Bernard et al., 2004; Douville et al., 2005), but only one of these studies reported activity in the hippocampus that decreased with memory age (Douville et al., 2005). Most studies used only two time points to assess memory age (e.g., a recent and a remote time point) and/or considered relatively old memories to be recent (e.g., 1- to 10-year-old or 5- to 15-year-old). We found that activity in the hippocampus decreased across the four time periods covering the most recent 12 years and then exhibited little change in activity across the three time periods that covered more remote memories. Earlier studies may not have measured memory from a sufficient number of time periods in the recent past and therefore did not achieve enough temporal resolution to detect the pattern of hippocampal activity that we observed. Further, this limited temporal resolution across time periods might also account for why earlier studies have not reported brain activity in the neocortex that changed in relation to memory age (Haist et al., 2001; Maguire et al., 2001; Maguire and Frith, 2003; Bernard et al., 2004).

In summary, brain activity in the hippocampus and temporopolar cortex during recall of semantic memories decreased as the memories became more remote. This activity followed the pattern that would be predicted from findings with patients who have circumscribed lesions of the hippocampus. The findings in the medial temporal lobe were not related to the richness of memories, to how well test questions were remembered later, nor to how frequently semantic memories were accompanied by episodic recollections. Accordingly, the findings appear to be due to a decreased dependence on medial temporal lobe structures as time passes after learning.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institute of Mental Health (MH24600), the Metropolitan Life Foundation, and the National Institute on Aging (P50 AG005131). We thank Mark Starr, Jennifer Frascino, Brock Kirwan, Yael Shrager, Peter Bayley, Peter Wais, Jeffrey Gold, and Adam Fleisher for assistance and also gratefully acknowledge the use of the resources of the Center for Imaging Science at The Johns Hopkins University for the LDDMM alignment analysis.

References

- Addis DR, Moscovitch M, Crawley AP, McAndrews MP. Recollective qualities modulate hippocampal activation during autobiographical memory retrieval. Hippocampus. 2004;14:752–762. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley PJ, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. The fate of old memories after medial temporal lobe damage. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13311–13317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4262-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard FA, Bullmore ET, Graham KS, Thompson SA, Hodges JR, Fletcher PC. The hippocampal region is involved in successful recognition of both remote and recent famous faces. Neuroimage. 2004;22:1704–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi B, Laurent-Demir C, Destrade C, Jaffard R. Time-dependent reorganization of brain circuitry underlying long-term memory storage. Nature. 1999;400:671–675. doi: 10.1038/23270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright P, Buckman J, Fradera A, Yoshimasu H, Colchester ACF, Kopelman MD. Retrograde amnesia in patients with hippocampal, medial temporal lobe, or frontal pathology. Learn Mem. 2006;13:545–557. doi: 10.1101/lm.265906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Wheeler ME. The cognitive neuroscience of remembering. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:624–634. doi: 10.1038/35090048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29:162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douville K, Woodard JL, Seidenberg M, Miller SK, Leveroni CL, Nielson KA, Franczak M, Antuono P, Rao SM. Medial temporal lobe activity for recognition of recent and remote famous names: an event related fMRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland PW, Bontempi B. The organization of recent and remote memories. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:119–130. doi: 10.1038/nrn1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland PW, Bontempi B, Talton LE, Kaczmarek L, Silva AJ. The involvement of the anterior cingulate cortex in remote contextual fear memory. Science. 2004;304:881–883. doi: 10.1126/science.1094804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilboa A, Winocur G, Grady CL, Hevenor SJ, Moscovitch M. Remembering our past: functional neuroanatomy of recollection of recent and very remote personal events. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:1214–1225. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haist F, Bowden Gore J, Mao H. Consolidation of human memory over decades revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1139–1145. doi: 10.1038/nn739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insausti R, Juottonen K, Soininen H, Insausti AM, Partanen K, Vainio P, Laakso MP, Pitkänen A. MR volumetric analysis of the human entorhinal, perirhinal, and temporopolar cortices. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998a;19:659–671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insausti R, Insausti AM, Sobreviela MT, Salinas A, Martínez-Peñuela JM. Human medial temporal lobe in aging: anatomical basis of memory preservation. Microsc Res Tech. 1998b;43:8–15. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19981001)43:1<8::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur N, Brooks DJ. Temporally-specific retrograde amnesia in two cases of discrete bilateral hippocampal pathology. Hippocampus. 1999;9:247–254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:3<247::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan CB, Jones CK, Miller MI, Stark CEL. High-resolution fMRI investigation of the medial temporal lobe. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28:959–966. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Frith CD. Lateral asymmetry in the hippocampal response to the remoteness of autobiographical memories. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5302–5307. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05302.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Henson RNA, Mummery CJ, Frith CD. Activity in prefrontal cortex, not hippocampus, varies parametrically with the increasing remoteness of memories. Neuroreport. 2001;12:441–444. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns JR, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. Semantic memory and the human hippocampus. Neuron. 2003;38:127–133. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maviel T, Durkin TP, Menzaghi F, Bontempi B. Sites of neocortical reorganization critical for remote spatial memory. Science. 2004;305:96–99. doi: 10.1126/science.1098180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland JL, McNaughton BL, O'Reilly RC. Why there are complementary learning systems in the hippocampus and neocortex: insights from the successes and failures of connectionist models of learning and memory. Psychol Rev. 1995;102:419–457. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.102.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MI, Beg MF, Ceritoglu C, Stark CEL. Increasing the power of functional maps of the medial temporal lobe by using large deformation diffeomorphic metric mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9685–9690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503892102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niki K, Luo J. An fMRI study of the time-limited role of the medial temporal lobe in long-term topographical autobiographical memory. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14:500–507. doi: 10.1162/089892902317362010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribot T. Les maladies de la memoire [Diseases of memory] New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1881. [Google Scholar]

- Rudy JW, Biedenkapp JC, O'Reilly RC. Prefrontal cortex and the organization of recent and remote memories: an alternative view. Learn Mem. 2005;12:445–446. doi: 10.1101/lm.97905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell WR, Nathan PW. Traumatic amnesia. Brain. 1946;69:280–300. doi: 10.1093/brain/69.4.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR. Remote memory as affected by aging. Neuropsychologia. 1974;12:429–435. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(74)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Alvarez P. Retrograde amnesia and memory consolidation: a neurobiological perspective. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Bayley PJ. The neuroscience of remote memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark CEL, Squire LR. When zero is not zero: the problem of ambiguous baseline conditions in fMRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12760–12766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221462998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima A, Petersson KM, Rutters F, Tendolkar I, Jensen O, Zwarts MJ, McNaughton BL, Fernández G. Declarative memory consolidation in humans: a prospective functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:756–761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507774103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. A co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain. New York: Thieme Medical; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Warrington EK, Silberstein M. A questionnaire technique for investigating very long term memory. Q J Exp Psychol. 1970;22:508–512. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler MA, Stuss DT, Tulving E. Frontal lobe damage produces episodic memory impairment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1995;1:525–536. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]