Abstract

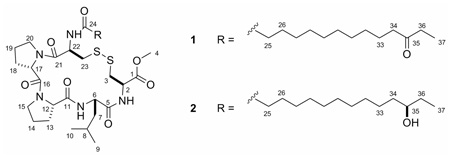

Eudistomides A (1) and B (2), two new cyclic peptides, were isolated from a Fijian ascidian Eudistoma sp. These five-residue cystine-linked cyclic peptides are flanked by a C-terminal methyl ester and a 12-oxo- or 12-hydroxy-tetradecanoyl moiety. The complete structures of the eudistomides were determined using a combination of spectroscopic and chemical methods. Chiral HPLC analysis revealed that all five amino acid residues in 1 and 2 had the L-configuration. Total synthesis of eudistomides A (1) and B (2) confirmed the proposed structures. Enantioselective lipase-catalyzed hydrolysis of a mixture of C-35 acetoxy epimers indicated a 35R absolute configuration for 2.

Introduction

Ascidians are known to be a rich source of complex and structurally unique peptides—peptides such as ulithiacyclamides,1–3 patellamides,3–7 lissoclinamides,7–9 and didemnins.10–15 To date, however, peptides have not been reported from the genus Eudistoma. Previous investigations of Eudistoma have yielded eudistomins,16–20 eudistomidins,21–24 iejimalides,25,26 and many alkaloids,27–37 several of which are brominated.33–37 As part of the continuing search for structurally unique secondary metabolites from marine invertebrates, a detailed exploration of the morphologically distinct Fijian ascidian Eudistoma sp. was undertaken. The isolation, structure elucidation, and synthesis of two new Eudistoma derived lipopeptides, eudistomides A (1) and B (2), are described herein.

Results and Discussion

The specimen (FJ04-12-071) of Eudistoma sp. was lyophilized, ground to a fine powder and exhaustively extracted with MeOH. The crude extract was subjected to an EtOAc/H2O partition, and the EtOAc soluble material was separated on HP20SS resin using a step gradient of H2O to acetone (10% steps, 11 fractions). The sixth (50/50 acetone/H2O) and seventh (60/40 acetone/H2O) fractions were combined and purified using several rounds of reversed-phase HPLC, resulting in the isolation of eudistomides A (1) and B (2).

Eudistomide A (1) showed an [M+Na]+ ion at m/z 790.3897 in the HRESIMS, consistent with the molecular formula C37H61N5O8S2 (calcd for C37H61N5O8S2Na, 790.3859; Δ +4.8 ppm), and required ten degrees of unsaturation. Initial evaluation of the 1H and 13C spectra suggested that 1 was a peptide (Table 1). The peptide nature of the molecule was further supported by the presence of three exchangeable NH signals at δH 6.08 (d, 10.5), 7.20 (d, 9.3), and 9.42 (d, 8.1) in the 1H NMR spectrum. The 13C NMR spectrum showed six carbonyl signals (amides and/or esters) at δC 169.4, 170.1, 170.9, 171.5, 171.8, and 173.2. The presence of an ester group in 1 was confirmed by analysis of the IR spectrum which displayed a characteristic absorbance band at νmax = 1740 cm−1. The 1H NMR and HMBC data corroborated the identity of the methyl ester; a methyl resonance at δH 3.73 (H-4) showed an HMBC correlation to a carbonyl at δC 170.9 (C-1). A carbon resonance at δ 212.1 (C-35) indicated the presence of a ketone in 1. The planar structure of eudistomide A (1) was assigned after extensive 1D and 2D NMR studies. Analysis of the 1D TOCSY, COSY, HSQC, and HMBC data established the presence of five amino acid residues; two Pro, two Cys, and one Leu (Table 1). The location of the C-35 ketone (δC 212.1) was established based on the presence of a triplet methyl δH 1.02 (H-37), a quartet methylene δH 2.38 (H-36), and a triplet methylene δH 2.36 (H-34) and their corresponding HMBC correlations to the ketone resonance. The combined NMR data was useful in assigning several methylene resonances to the aliphatic chain. However, the precise chain length could not be determined due to the extensive overlap of resonances within the methylene envelop. Fortunately, the molecular formula supported the proposed fourteen carbon lipid chain; the 12-oxo-tetradecanoyl portion of 1. Nine of the ten degrees of unsaturation were accounted for with the seven carbonyls and the two Pro, which suggested that a cystine-linked ring was the remaining degree of unsaturation.

Table 1.

NMR data for eudistomides A (1) and B (2) (600 MHz, CDCl3)

| eudistomide A (1) | eudistomide B (2)c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| position | δC | δH mult (J, Hz) | δC | δH mult (J, Hz) | |

| Cys-1 (Cys-OMe) |

1 | 170.9 | — | 170.9 | — |

| 2 | 49.9 | 4.86, ddd (11.0, 9.3, 3.7) | 49.9 | 4.87 | |

| 3a | 41.5 | 3.32, dd (14.2, 3.7) | 41.5 | 3.33 | |

| 3b | 2.77, dd (14.2, 11.0) | 2.77 | |||

| 4 | 52.5 | 3.73, s | 52.5 | 3.74 | |

| NH | — | 7.20, d (9.3) | — | 7.18 | |

| Leu | 5 | 171.5 | — | 171.5 | — |

| 6 | 51.4 | 4.49,b ddd (8.1, 5.3, 5.0) | 51.4 | 4.50 | |

| 7a | 36.1 | 1.83,b ddd (14.7, 10.8, 5.0) | 36.1 | 1.83 | |

| 7b | 1.48,b ddd (14.7, 9.3, 5.3) | 1.48 | |||

| 8 | 24.2 | 1.60, m (10.8, 9.3, 6.6, 6.4) | 24.2 | 1.60 | |

| 9 | 21.0 | 0.84, d (6.4) | 21.0 | 0.85 | |

| 10 | 23.0 | 0.94, d (6.6) | 23.0 | 0.95 | |

| NH | — | 9.42, br d (8.1) | — | 9.40 | |

| Pro-1 | 11 | 173.2 | — | 173.2 | — |

| 12 | 60.9 | 4.48,b dd (8.2, 2.5) | 60.9 | 4.49 | |

| 13a | 32.5 | 2.35,b dddd (12.5, 6.5, 6.5, 2.5) | 32.5 | 2.35 | |

| 13b | 2.10,b dddd (12.5, 10.5, 8.2, 1.9) | 2.10 | |||

| 14a | 21.3 | 1.96,a m | 21.3 | 1.96 | |

| 14b | 1.80,a m | 1.80 | |||

| 15 | 46.5 | 3.56,b dd (7.2, 10.0) | 46.5 | 3.56 | |

| Pro-2 | 16 | 170.1 | — | 170.1 | — |

| 17 | 59.4 | 4.94, dd (8.7, 2.0) | 59.4 | 4.94 | |

| 18a | 30.7 | 2.28,b dddd (8.1, 8.7, 12.3, 16.4) | 30.7 | 2.28 | |

| 18b | 1.83,a m | 1.83 | |||

| 19a | 22.4 | 1.94,a m | 22.4 | 1.94 | |

| 19b | 1.87,a m | 1.87 | |||

| 20a | 46.4 | 3.73,b ddd (11.9, 8.8, 4.6) | 46.4 | 3.73 | |

| 20b | 3.53,b ddd (11.9, 7.7, 7.7) | 3.53 | |||

| Cys-2 | 21 | 169.4 | — | 169.4 | — |

| 22 | 48.8 | 4.61, ddd (10.5, 10.5, 5.1) | 48.8 | 4.62 | |

| 23a | 38.4 | 3.25, dd (12.9, 5.1) | 38.4 | 3.25 | |

| 23b | 2.56, dd (12.9, 10.5) | 2.57 | |||

| NH | — | 6.08, br d (10.5) | — | 5.98 | |

| 12-oxo-tetradecanoyl | 24 | 171.8 | — | 171.8 | — |

| 25 | 36.1 | 2.10,a m | 36.1 | 2.10,a m | |

| 26 | 24.9 | 1.55,a m | 24.9 | 1.55,a m | |

| 27–32 | 29.0 | 1.23, br s | 29.0 | 1.23, br s | |

| 33a | 23.9 | 1.54,a m | 25.8 | 1.38,a m | |

| 33b | — | — | 1.28, m | ||

| 34 | 42.4 | 2.36, t (7.5) | 36.7 | 1.37,a m | |

| 35 | 212.1 | — | 73.1 | 3.49, m | |

| 36a | 35.8 | 2.38, q (7.3) | 29.7 | 1.47, m | |

| 36b | — | — | 1.40, m | ||

| 37 | 7.8 | 1.02, t (7.3) | 10.1 | 0.92, t (7.5) | |

Signals overlapped.

Obtained from 1D-TOCSY.

Coupling constants for peptide portion are similar.

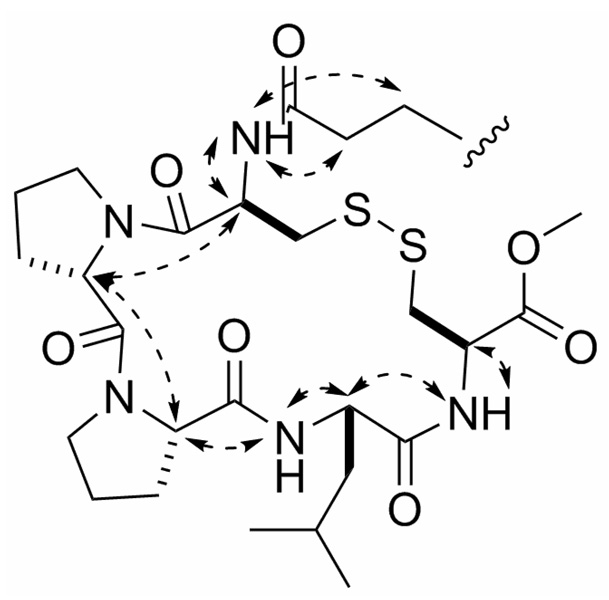

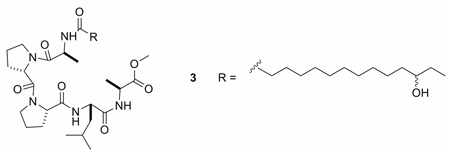

The amino acid sequence of eudistomide A (1) was determined using a combination of HMBC, ROESY, and MS/MS data. The location of the tetradecanoyl moiety and one of the Cys residues (Cys-2) in 1 was established based on HMBC correlations from the methylenes at δH 2.10 and 1.55 (H-25 and H-26, respectively), the Cys-2 α-proton (H-22, δH 4.61), and the Cys-2 NH (δH 6.08) to a carbonyl at δC 171.8 (C-24). The aforementioned methyl ester was assigned to the C-terminal Cys residue (Cys-1) based on a HMBC correlation from the Cys-1 α-proton (H-2, δH 4.86) to the methyl ester carbonyl (C-1, δC 170.9). The Leu residue was placed adjacent to Cys-1 (Cys-OMe) based on HMBC correlations from the Cys-1 NH (δH 7.19), and the Leu β-protons (H-7a, H-7b, δH 1.83, 1.48) to the carbonyl at δC 171.5 (C-5). Pro-1 was positioned adjacent to the Leu based on HMBC correlations from the Leu NH (δH 9.42), and the Pro-1 β-protons (H-13a, H-13b, δH 2.35, 2.10) to the carbonyl at δC 173.2 (C-11). Due to their overlap, HMBC correlations from the Leu α-proton (H-6, δH 4.49) and the Pro-1 α-proton (H-12, δH 4.48) could not be utilized. HMBC correlations from the Pro-1 δ-proton (H-15, δH 3.56) and the Pro-2 β-protons (H-18a, H-18b, δH 2.28, 1.83) to the carbonyl at δC 170.1 (C-16) placed Pro-2 adjacent to Pro-1. No HMBC correlations were observed between Pro-2 and Cys-2. ROESY data supported the proposed sequence of the peptide (Figure 1). Although the ROE correlations from δH 4.49 (H-6) and δH 4.48 (H-12) supported the peptide sequence, the overlap of the proton signals created ambiguity. Therefore, MS/MS studies were conducted to further support the proposed peptide sequence (Table 2). In order to simplify sequence analysis of 1, the linear peptide desthioeudistomide B (3), generated from a Raney Ni desulfurization of 1 (Cys → Ala, ketone → hydroxyl), was analyzed by MS/MS. Compound 3 showed fragment ions consistent with Leu-Ala-OMe, Pro-Leu-Ala-OMe, Pro-Pro-Leu-Ala-OMe, Pro-Leu, and Pro-Pro-Leu partial sequences. Eudistomide A (1) showed a similar fragmentation pattern to 3 (Pro-Leu and Pro-Pro-Leu were identical), with an addition of 64 Da for the Cys containing fragments, consistent with the addition of 2 sulfurs. Based on the HMBC, ROESY and MS/MS data, the peptide sequence of eudistomide A (1) was assigned as cyclized Cys-Pro-Pro-Leu-Cys-OMe, N-acylated with a 12-oxo-tetradecanoyl fragment.

Figure 1.

Key ROE correlations supporting the peptide sequence of Eudistomide A (1).

Table 2.

Fragmentation ions observed in ESI-MS/MS data confirming the amino acid sequences of eudistomides A (1) and B (2), and desthioeudistomide B (3)

| Compound | Ions Observed | Identity | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1, 2 | 281a,c | Leu-Cys-OMe + S | C10H21N2O3S2 |

| 1, 2 | 378a,c | Pro-Leu-Cys-OMe + S | C15H28N3O4S2 |

| 1, 2 | 475a,c | Pro-Pro-Leu-Cys-OMe + S | C20H35N4O5S2 |

| 1, 2 | 308a,c | Pro-Pro-Leu | C16H26N3O3 |

| 1, 2 | 211a,c | Pro-Leu | C11H19N2O2 |

| 3 | 217.15502b | Leu-Ala-OMe | C10H21N2O3 |

| 3 | 314.20796b | Pro-Leu-Ala-OMe | C15H28N3O4 |

| 3 | 411.26097b | Pro-Pro-Leu-Ala-OMe | C20H35N4O5 |

| 3 | 308.19740b | Pro-Pro-Leu | C16H26N3O3 |

| 3 | 211.14442b | Pro-Leu | C11H19N2O2 |

Ions observed on a micro Q-tof using CID.

Ions observed on a LTQ-FT using IRMPD, all ions have < 1.5 ppm accuracy.

Identical ions observed for synthetic eudistomides A (1) and B (2).

It is well documented that cis-trans conformational differences in proline amide bonds can be distinguished in solution by the chemical shift differential of the β- and γ-carbons (Δδβγ).38 Typically, a cis-Pro has a chemical shift differential greater than 8 ppm and a trans-Pro has a differential less than 6 ppm. In eudistomide A (1), the shift differentials are 11.5 and 8.5 for Pro-1 and Pro-2, respectively, indicating that both Pro residues are in the cis conformation.

The absolute configuration of each amino acid in eudistomide A (1) was determined by chiral HPLC analysis of the acid hydrolyzate. Compound 1 was desulfurized using Raney Ni in refluxing MeOH39 to generate desthioeudistomide B (3), which was then hydrolyzed with aqueous HCl. Chiral HPLC analysis of the hydrolyzate and authentic standards established the presence of two l-Pro, two l-Ala and one l-Leu in eudistomide A (1). Since the linear peptide 3 only contained l-Ala, the two cysteines in 1 were also assigned l configuration.

Eudistomide B (2) was assigned the molecular formula C37H63N5O8S2 based on HRESIMS analysis of the protonated molecular ion [M+H]+ at m/z 770.4160. When compared with the formula for 1, eudistomide B (2) showed an additional two H’s, which suggested either the disulfide bond or the ketone was reduced in 2. The NMR spectra of eudistomides A (1) and B (2) are virtually identical, and indicated that both 1 and 2 contained the same five amino acids (Table 1). One obvious difference between the two compounds was the lack of a ketone in 2. Analysis of COSY and HMBC data showed that a secondary alcohol (δC 73.1) was present at C-35 in eudistomide B (2). MS/MS fragmentation of 2 confirmed that the disulfide bond was still present (Table 2). Since HMBC, ROESY and MS/MS data for 2 were comparable to 1, the peptide sequence of eudistomide A (2) was confirmed as cyclized Cys-Pro-Pro-Leu-Cys-OMe, N-acylated with a 12-hydroxy-tetradecanoyl fragment. The Δδβγ for eudistomide B (2) was identical to 1, indicating that 2 also contained two cis-Pro residues. Since eudistomides A (1) and B (2) are biosynthetically related and all chemical shifts for the peptide portions are virtually indistinguishable, the amino acids in 2 were also assigned the l configuration.

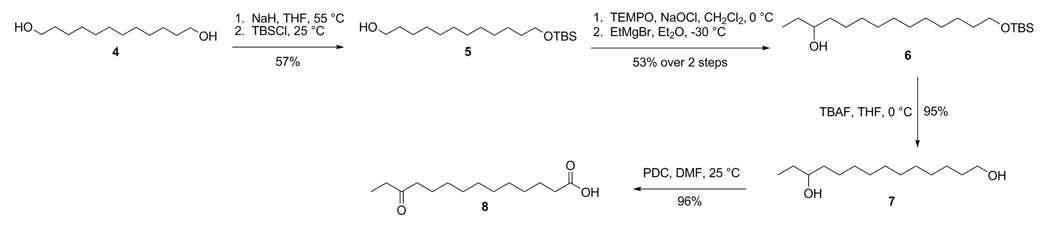

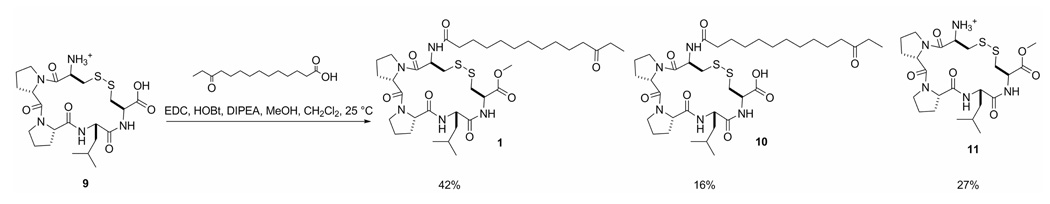

A total synthesis of eudistomide A (1) was undertaken to confirm the proposed structure. To synthesize the 12-keto-tetradecanoic acid, the commercially available starting material dodecane-1,12-diol (4) was protected with TBSCl to give the monoprotected 12-(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)dodecan-1-ol (5) (Scheme 1). Catalytic TEMPO oxidation of compound 5, followed by Grignard addition of the ethyl group generated 14-(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)tetradecan-3-ol (6). Compound 6 was deprotected with TBAF to yield tetradecane-1,12-diol (7), and subsequently oxidized to form 12-oxo-tetradecanoic acid (8). The cyclized pentapeptide, Cys-Pro-Pro-Leu-Cys (9), was synthesized by the University of Utah Peptide Synthesis facility using standard solid phase peptide synthesis procedures. Coupling of the acid (8) to the cyclic pentapeptide (9), and simultaneous methylation was achieved using EDC, HOBt, DIPEA, and MeOH to yield eudistomide A (1) as the major product. Eudistomide acid (10) and the cyclic pentapeptide methyl ester (11) were identified as side products (Scheme 2). Interestingly, when attempting to form the methyl ester (11) of precursor peptide (9) with diazomethane prior to coupling, the primary amine of Cys-2 was concurrently methylated to form the quaternary amine. Thionyl chloride in MeOH proved to be the best means of introducing the methyl ester to this peptide, and can be used prior to coupling without undesired amine methylation. The side products of the coupling reaction (10 and 11) were converted to eudistomide A (1) in the following manner: compound 10 was methylated using thionyl chloride in MeOH,40 and 11 was coupled to the acid (8) using EDC, HOBt, and DIPEA. The final synthetic product (1) was identical to the natural product obtained from Eudistoma sp. in HPLC retention time, MS/MS fragmentation, MS and NMR spectra, which confirmed the proposed structure for eudistomide A (1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 12-oxo-tetradecanoic acid (8)

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of eudistomide A (1)

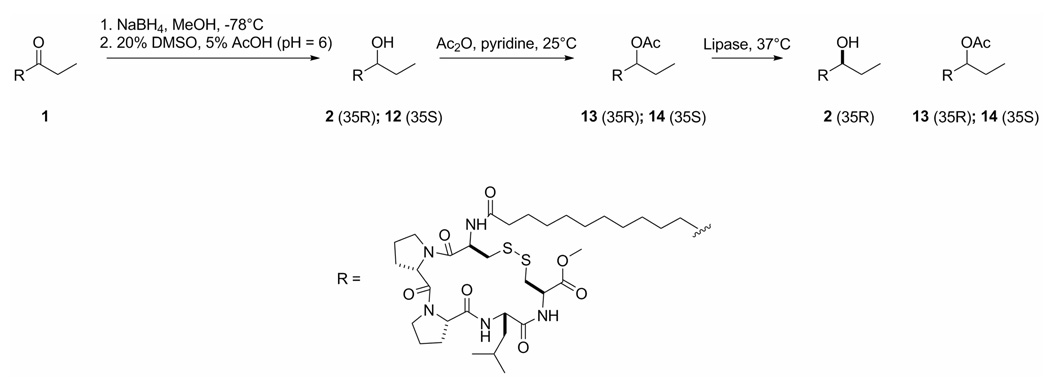

Determining the configuration of the C-35 alcohol in eudistomide B (2) was necessary to complete the structure. Several attempts were made to esterify the C-35 alcohol of 2 with MPA to determine the configuration by the modified Mosher method; however, none proved successful. Optimization of reaction conditions for MPA-derivitization was carried out using 6 from the synthesis, but the conditions were not favorable for 2, and no significant amounts of product were detected by LC-MS. To preserve the limited supply of eudistomide B (2), a scheme was proposed using synthetic eudistomide A (1) in an attempt to resolve the configuration of the C-35 alcohol in 2 (Scheme 3). Compound 1 was reduced using sodium borohydride in MeOH at −78 °C,41 and the disulfide was re-oxidized using DMSO in acetic acid42 to give a mixture of C-35 alcohol epimers (2, 12). The HSQC data showed that the 1H and 13C chemical shifts of the C-35 hydroxy methines of the two epimers were very different; one showed a proton resonance at δH 3.52 attached to a carbon at δC 73.2, and the other showed a proton resonance at δH 4.84 attached to a carbon at δC 74.7. Efforts to separate the alcohol epimers (2, 12) were not successful. Literature precedents using similar substrates43,44 confirm that lipase B from Candida antarctica shows selectivity for R-secondary acetates as substrates, with % ee being ≥ 99% when conversion is less than 50%. Accordingly, lipase-catalyzed hydrolysis of the C-35 acetoxy epimers would primarily generate the R-alcohol. Therefore, the alcohol epimers were treated with acetic anhydride in pyridine to generate the C-35 acetoxy derivatives (13, 14). Lipase B from C. antarctica was added to the acetoxy epimers (13, 14) at 37 °C and the products were analyzed by HSQC. Only one alcohol signal appeared in the HSQC (δH 3.52, δC 73.2), and was assigned the R-configuration. The C-35 alcohol in eudistomide B (2) (δH 3.49, δC 73.1) was also assigned the R-configuration on the basis of identical chemical shifts to the lipase-derived R-isomer of 1.

Scheme 3.

Determination of the side chain configuration in eudistomide B (2)

Eudistomides A (1) and B (2) are interesting cyclic lipopeptides that contain several rare structural motifs. The acyl chain present in 1 and 2 has never been reported from a marine organism.45 However, similar acyl groups such as unsubstituted tetradecanoyl,46–48 13-methyltetradecanoyl,49,50 2,3-hydroxy-tetradecanoyl,51 3-hydroxy-13-methyltetradecanoyl,52 and 7-methoxytetradec-4-enoyl53–55 chains have been reported. Interestingly, the microsporins56 contain a 2-amino-8-oxodecanoic acid or a 2-amino-8-hydroxydecanoic acid that is similar to the ketone and hydroxyl derivatives seen in 1 and 2. And while marine organisms are the source of several peptides that contain cystine moieties such as the ulithiacyclamides,1–3 thiocoralines,57 microcionamides,39 and neopetrosiamides,58 eudistomides A (1) and B (2) are the first ascidian-derived peptides cyclized solely by a disulfide bridge.45

Experimental Section

Biological Material

Eudistoma sp., sample FJ04-12-071, was collected by SCUBA near Namena Barrier Reef, Fiji Islands (17° 06.884′ S, 179° 03.805′ E); a voucher specimen is maintained at the University of Utah. This thick dark gray encrusting Eudistoma sp. was found in large patches (approximately 0.5 m) and expressed copious amounts of clear mucous.

Extraction and Isolation

The Eudistoma sp. specimen was lyophilized and ground to a fine powder. The powder was exhaustively extracted with MeOH to yield 15.4 g of crude extract. The crude extract was subjected to an EtOAc/H2O partition to generate 1.7 g of the organic fraction. The EtOAc soluble material was separated on HP20SS resin using a gradient of H2O to acetone in 10% steps, and a final wash of 100% acetone, to yield 11 fractions. The sixth (50/50 acetone/H2O) and seventh fractions (60/40 acetone/H2O) were combined (34.5 mg) and chromatographed by HPLC using a Phenomenex Luna C18 column (250 × 10 mm) employing a gradient of 50% CH3CN/H2O to 100% CH3CN at 2.5 mL/min over 30 min to yield 4 fractions, 29A–29D. Fraction 29C was further chromatographed using a Phenomenex Luna C18 (150 × 4.6 mm) column using a gradient of 70% CH3CN/H2O to 85% CH3CN/H2O at 1.0 mL/min over 15 min to yield 2 fractions, 35A–35B. Fraction 35A was re-purified using a Phenomenex Luna C18 (250 × 10 mm) column using a gradient of 50% CH3CN/50% H2O (+0.1% AcOH) to 98% CH3CN/2% H2O (+ 0.1% AcOH) at 4.5 mL/min over 20 min to yield eudistomide A (1, 0.2 mg) eluting at 12.9 min and eudistomide B (2, 0.35 mg) eluting at 11.2 min. Reisolation from associated fractions and extraction of the remaining crude material provided an additional 3.2 mg of 1.

Eudistomide A (1)

amorphous, white solid [α]20D −1.3 (c 0.2, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) 206 (3.77) nm; IR (film, NaCl) νmax 3284 (br), 2921, 2852, 1743, 1708, 1662, 1641, 1549, 1253, 702 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 790.3897 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C37H61N5O8S2Na, 790.3859).

Eudistomide B (2)

amorphous, white solid [α]20D −4.0 (c 0.03, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) 206 (3.61) nm; IR (film, NaCl) νmax 3222 (br), 2921, 2852, 1745, 1662, 1641, 1549, 1259, 725 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 770.4160 [M+H]+ (calcd for C37H64N5O8S2, 770.4191).

Desulfurization of Eudistomide A (1)

Approximately 100 µL of Raney 2800 nickel (50% slurry in H2O; excess) was added to eudistomide A (1.0 mg, 1.3 µmol) in MeOH (1.2 mL). Argon was bubbled through the solution to remove O2, the resulting black suspension was heated at 65 °C under argon for 4 h, and monitored by HPLC for the disappearance of starting material. Upon cooling, the solution was purified on a C18 SPE cartridge using MeOH as eluant, yielding pure desthioeudistomide B (3, 0.5 mg, 54% yield).

Desthioeudistomide B (3)

amorphous white solid. HRESIMS m/z 708.49059 [M+H]+ (calcd for C37H66N5O8, 708.49059); HRESI-MS/MS, see Table 2.

Absolute Configuration of each Amino Acid in Desthioeudistomide B (3)

Compound 3 (0.5 mg) was dissolved in 6N HCl (500 µL) and heated at 110 °C under argon for 21 h. The product mixture was lyophilized and analyzed by chiral HPLC [column, Phenomenex Chirex phase 3126 (D) (250 × 4.6 mm); solvent 1 mM CuSO4/CH3CN (95:5); flow rate, 1.0 mL/min, UV detection at 254 nm], comparing the retention times with those of authentic standards. The retention times (min) of the authentic amino acids were: l-Ala (6.9), d-Ala (8.4), l-Pro (9.5), d-Pro (20.0), l-Leu (51.3), and d-Leu (65.9). The retention times of the amino acid components in the acid hydrolyzate were 6.9, 9.4, and 51.3, indicating the presence of l-Ala, l-Pro, and l-Leu, respectively.

12-(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)dodecan-1-ol (5)

0.4 g of NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil, 10 mmol) was washed with anhydrous THF (2 × 20 mL; to remove the mineral oil), and suspended in anhydrous THF (20 mL). 2.02 g (10 mmol) of dodecane-1,12-diol (4) was added to the solution and left to stir under argon at 55 °C. After 18 h, the mixture was cooled to room temperature, and 1.51 g of TBSCl (10 mmol) in anhydrous THF (2.5 mL) was added, and allowed to stir for 2 h at rt. The mixture was diluted with Et2O, and washed successively with 10% K2CO3 and brine. The combined organic extracts were dried (MgSO4) and concentrated in vacuo. Purification of the crude material by silica column chromatography: [solvent 1: 90% Hexanes/10% EtOAc (elutes the di-silyl ether product); solvent 2: 80% Hexanes/20% EtOAc] afforded the mono-silylated product 5 as a colorless solid (1.01 g, 57% yield). 5: 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 3.57 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz), 3.48 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz), 1.45 (4H, m), 1.28 (14H, br s), 0.84 (9H, s), 0.00 (6H, s); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 63.4, 63.1, 34.0, 33.8, 31.0−30.5, 27.1, 27.0, 26.6, 19.3, −5.0; HRESIMS m/z 299.2765 [M-H2O]+ (calcd for C18H39OSi, 299.2770).

14-(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)tetradecan-3-ol (6)

A 0.5 M aq solution of KBr (7.14 mg, 0.06 mmol) was added to a vigorously stirring solution of 5 (188.8 mg, 0.6 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.7 mL) at 0 °C, followed by the addition of TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperdine 1-oxyl) free radical (0.94 mg, 0.006 mmol). NaOCl (5% active chlorine) adjusted to pH = 8.6 using NaHCO3 (1.5 mL) was added drop-wise to the solution and allowed to stir for 5 min at 0 °C until the hypochlorite was consumed and the solution went from a red-orange to a milky yellow color. The organic layer of the two phase mixture was separated, dried (MgSO4) and concentrated to dryness in vacuo at 0 °C. The crude aldehyde (160 mg, 0.51 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous Et2O (3.2 mL) and cooled to −30 °C under argon. EtMgBr (202 µL, 0.61 mmol, 3M in ether) was added drop-wise to the solution, and the mixture was left to stir at −30 °C. After 1.5 h, the reaction was quenched with saturated NH4Cl (316 µL). The solution was warmed to room temperature, washed with brine, and extracted with Et2O. The ethereal extracts were combined, dried (MgSO4), filtered and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica column chromatography: [solvent: 83% Hexanes/17% MTBE] to afford 6 as a colorless solid (91.8 mg, 53% yield). 6: 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 3.55 (2H, t, J = 6.7 Hz), 3.47 (1H, m), 1.55−1.30 (6H, m), 1.24 (16H, br s), 0.89 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 0.84 (9H, s), 0.00 (6H, s); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 73.5, 63.6, 37.2, 33.1, 30.4, 30.0−29.5, 26.2, 26.0, 25.9, 18.6, 10.1, −5.0; HRESIMS m/z 367.3009 (calcd for C20H44O2SiNa, 367.3008).

Tetradecane-1,12-diol (7)

TBAF (tetrabutylammonium fluoride, 124.5 mg, 0.48 mmol) in THF (0.5 mL) was added drop-wise to a solution of 6 (81.8 mg, 0.24 mmol) in THF (3.1 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 4 h. Cold water was added to quench the reaction, and the resultant mixture was extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic extracts were washed with brine, dried (MgSO4), filtered and concentrated to dryness in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica column chromatography: [solvent 1: 80% CH2Cl2/20% EtOAc (eluted remaining 6); solvent 2: 50% CH2Cl2/50% EtOAc] to yield 7 as a colorless solid (52.0 mg, 95% yield). 7: 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 3.58 (2H, t, J = 6.6 Hz), 3.46 (1H, m), 1.60−1.30 (8H, m), 1.24 (14H, br s), 0.89 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 73.5, 63.2, 37.1, 33.0, 30.3, 30.0−29.5, 25.9, 25.8, 10.1; HRESIMS m/z 213.2217 [M-H2O]+ (calcd for C14H29O, 213.2218).

12-oxo-tetradecanoic acid (8)

A solution of 7 (15 mg, 65.2 µmol) in anhydrous DMF (700 µL) was treated with PDC (197 mg, 0.52 mmol) under argon. The dark brown solution was allowed to stir at room temperature for 17 h. The reaction was quenched with water and extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed successively with water and brine, dried (MgSO4), and concentrated to dryness in vacuo to yield 8 as a colorless solid (15.1 mg, 96% yield). 8: 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) 2.50−2.20 (6H, m), 1.60−1.40 (4H, m), 1.23 (12H, br s) 1.01 (3H, br t, J = 6.5 Hz); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 212.0, 179.7, 42.3, 35.7, 33.9, 29.5−28.5, 24.5, 23.8, 7.7; HRESIMS m/z 243.1946 [M+H]+ (calcd for C14H27O3, 243.1955).

Cyclic Pentapeptide (9)

amorphous white solid. 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Supporting Info Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 552.1912 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C22H35N5O6S2Na, 552.1926).

Eudistomide A (1)

EDC (12.6 mg, 22.7 µmol) and HOBt (8.9 mg, 22.7 umol) were added to a stirred solution of 8 (5.1 mg, 22.7 µmol) in anhydrous 90% CH2Cl2/10% MeOH (1.8 mL) under argon for 3 h to activate the acid. DIPEA (3.3 µL, 19.3 µmol) was added to a stirred solution of 9 (10.2 mg, 19.3 µmol) in 85% CH2Cl2/15% MeOH (1.9 mL) and allowed to stir for 3 h to neutralize the peptide. After 3 h, the neutralized peptide (9) was added to the acid (8) and DIPEA was added to the solution (3.3 µL, 19.3 µmol). The reaction was monitored by HPLC for the disappearance of starting material. The reaction was quenched with H2O after 48h, extracted with CH2Cl2, and concentrated in vacuo. The reaction products were purified using a Phenomenex C18 (250 × 10 mm) column using a gradient of 2% CH3CN/98% H2O (+0.1% AcOH) to 98% CH3CN/2% H2O (+ 0.1% AcOH) at 4.5 mL/min over 40 min to yield pure eudistomide A (1) (2.2 mg, 42%) eluting at 33.4 min, the peptide methyl ester (11) (1.0 mg, 27%) eluting at 11.2 min, and the eudistomide acid (10) (0.8 mg, 16%) eluting at 28.3 min. HPLC retention times of the natural eudistomide A (1) and the synthetic eudistomide A (1) were compared using a Phenomenex C18 (250 × 4.6 mm) column employing a gradient of 50% CH3CN/50% H2O (+ 0.1% AcOH) to 98% CH3CN/2% H2O (+ 0.1% AcOH) at 1 mL/min over 20 min. Natural 1 had a retention time of 12.8 min, and synthetic 1 also had a retention time of 12.8 min. 1: [α]20D −3.5 (c 0.06, MeOH); 1H NMR and 13C NMR data identical to natural product, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 768.4034 [M+H]+ (calcd for C37H62N5O8S2, 768.4040). ESI-MS/MS, see Table 2.

Eudistomide B Epimers (2, 12)

A solution of 1 (1.3 mg, 1.7 µmol) in anhydrous MeOH (250 µL) at −78 °C was treated with NaBH4 (1.0 mg, 26.4 µmol) under argon. The solution was allowed to stir for 7 h. The reaction was quenched with water, the MeOH was evaporated under argon, and the resulting aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic extracts were dried under argon, and redissolved in 5% AcOH (400 µL, pH=6). DMSO (100 µL) was added to the solution that was left to stir overnight. The reaction products were concentrated in vacuo and purified using a Phenomenex C18 (250 × 10 mm) column employing a gradient of 50% CH3CN/50% H2O (+ 0.1% AcOH) to 98% CH3CN/2% H2O (+ 0.1% AcOH) at 4.5 mL/min over 20 min to yield a mixture of C-35 alcohol epimers (2, 12) co-eluting at 11.3 min (1.1 mg, 84%). HPLC retention times of the natural eudistomide B (2) and the synthetic C-35 alcohol epimers (2, 12) were compared using a Phenomenex C18 (250 × 4.6 mm) column employing a gradient of 50% CH3CN/50% H2O (+ 0.1% AcOH) to 98% CH3CN/2% H2O (+ 0.1% AcOH) at 1 mL/min over 20 min. Natural 2 had a retention time of 11.2 min, and the synthetic alcohol epimers (2, 12) also had retention times of 11.2 min. LRESIMS m/z 770.4 [M+H]+; ESI-MS/MS, see Table 2

Supplementary Material

General experimental procedures, acetylation reaction conditions, lipase reaction conditions, 1H spectra of 1 and 2, 13C spectrum of 1, 1H and 13C spectra of 5–;9, table of assignments for 9, 1H and HSQC spectra of eudistomide B epimers (2, 12), 1H and HSQC spectra of eudistomide B acetate ester epimers (13, 14), and 1H and HSQC spectra of the lipase reaction products (2, 13, 14). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Krishna Parsawar and Dr. Chad Nelson, University of Utah Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Core Facility, for performing FTMS experiments. Ascidian taxonomy was graciously provided by Gretchen Lambert, University of Washington, Friday Harbor Laboratories. The authors would also like to recognize Dr. Robert Schackmann and Scott Endicott of the University of Utah Peptide Synthesis Core Facility. We acknowledge the NIH, grants RR13030, RR06262 and RR14768, and NSF grant DBI-0002806 for funding NMR instrumentation in the University of Utah Health Sciences NMR Facility. This research was supported by NCI grant CA67786 and NIH grant CA36622.

References and Notes

- 1.Ireland CM, Scheuer PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:5688–5691. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams DE, Moore RE, Paul VJ. J. Nat. Prod. 1989;52:732–739. doi: 10.1021/np50064a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu X, Do T, Schmitz FJ, Andrusevich V, Engel MH. J. Nat. Prod. 1998;61:1547–1551. doi: 10.1021/np9802872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ireland CM, Durso AR, Newman RA, Hacker MP. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:1807–1811. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald LA, Ireland CM. J. Nat. Prod. 1992;55:376–379. doi: 10.1021/np50081a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rashid MA, Gustafson KR, Cardellina JH, 2nd, Boyd MR. J. Nat. Prod. 1995;58:594–597. doi: 10.1021/np50118a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degnan BM, Hawkins CJ, Lavin MF, McCaffrey EJ, Parry DL, van den Brenk AL, Watters DJ. J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:1349–1354. doi: 10.1021/jm00126a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris LA, Kettenes van den Bosch JJ, Versluis K, Thompson GS, Jaspars M. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:8345–8353. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawkins CJ, Lavin MF, Marshall KA, van den Brenk AL, Watters DJ. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:1634–1638. doi: 10.1021/jm00168a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinehart KL, Gloer JB, Cook JC, Mizsak SA, Scahill TA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:1857–1859. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rinehart KL, Kishore V, Bible KC, Sakai R, Sullins DW, Li KM. J. Nat. Prod. 1988;51:1–21. doi: 10.1021/np50055a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmitz FJ, Yasumoto T. J. Nat. Prod. 1991;54:1469–1490. doi: 10.1021/np50078a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rinehart KL. Med. Res. Rev. 2000;20:1–27. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(200001)20:1<1::aid-med1>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulanger A, Abou-Mansour E, Badre A, Banaigs B, Combaut G, Francisco C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:4345–4348. doi: 10.1021/np50106a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakai R, Stroh JG, Sullins DW, Rinehart KL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:3734–3748. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rinehart KL, Kobayashi J, Harbour GC, Hughes RG, Mizsak SA, Scahill TA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:1524–1526. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi J, Harbour GC, Gilmore J, Rinehart KL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:1526–1528. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinzer KF, Cardellina JH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:925–926. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang H, Fenical W. Nat. Prod. Lett. 1996;9:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schupp P, Poehner T, Edrada R, Ebel R, Berg A, Wray V, Proksch P. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66:272–275. doi: 10.1021/np020315n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi J, Nakamura H, Ohizumi Y, Hirata Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:1191–1194. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi J, Cheng J, Ohta T, Nozoe S, Ohizumi Y, Sasaki T. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:3666–3670. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murata O, Shigemori H, Ishibashi M, Sugama K, Hayashi K, Kobayashi J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:3539–3542. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rashid MA, Gustafson KR, Boyd MR. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:1454–1456. doi: 10.1021/np010214+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi J, Cheng J, Ohta T, Nakamura H, Nozoe SHY, Ohizumi Y, Sasaki T. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:6147–6150. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kikuchi Y, Ishibashi M, Sasaki T, Kobayashi J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:797–798. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi J, Cheng J, Kikuchi Y, Ishibashi M, Yamamura S, Ohizumi Y, Ohta T, Nozoe S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:4617–4620. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudi A, Kashman Y. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:5331–5337. [Google Scholar]

- 29.He HY, Faulkner DJ. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:5369–5371. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viracaoundin I, Faure R, Gaydou EM, Aknin M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:2669–2671. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Wagoner RM, Jompa J, Tahir A, Ireland CM. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:1100–1101. doi: 10.1021/np010127h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis RA, Christensen LV, Richardson AD, Moreira da Rocha R, Ireland CM. Mar. Drugs. 2003;1:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Debitus C, Laurent D, Pais M. J. Nat. Prod. 1988;51:799–801. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adesanya SA, Chbani M, Pais M, Debitus C. J. Nat. Prod. 1992;55:525–527. doi: 10.1021/np50082a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makarieva TN, Ilyin SG, Stonik VA, Lyssenko KA, Denisenko VA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:1591–1594. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Wagoner RM, Jompa J, Tahir A, Ireland CM. J. Nat. Prod. 1999;62:794–797. doi: 10.1021/np9805589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makarieva TN, Dmitrenok AS, Dmitrenok PS, Grebnev BB, Stonik VA. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:1559–1561. doi: 10.1021/np010161w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siemion IZ, Wieland T, Pook KH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1975;14:702–703. doi: 10.1002/anie.197507021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis RA, Mangalindan GC, Bojo ZP, Antemano RR, Rodriguez NO, Concepcion GP, Samson SC, de Guzman D, Cruz LJ, Tasdemir D, Harper MK, Feng X, Carter GT, Ireland CM. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:4170–4176. doi: 10.1021/jo040129h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Culbertson SM, Porter NA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4032–4038. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baag MM, Puranik VG, Argade NP. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:1009–1012. doi: 10.1021/jo0619128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tam JP, Wu CR, Liu W, Zhang JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:6657–6662. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohtanib T, Nakatsukasaa H, Kamezawab M, Tachibanab H, Naoshimaa Y. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 1998;4:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baumann M, Hauer BH, Bornscheuer UT. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2000;11:4781–4790. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blunt JW, Blunt DA. MarinLit Database. Department of Chemistry, University of Canterbury; http://www.chem.canterbury.ac.nz/marinlit/marinlit.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rowley DC, Kelly S, Kauffman CA, Jensen PR, Fenical W. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003;11:4263–4274. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(03)00395-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smyrniotopoulos V, Abatis D, Tziveleka LA, Tsitsimpikou C, Roussis V, Loukis A, Vagias C. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66:21–24. doi: 10.1021/np0202529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou BN, Tang SB, Johnson RK, Mattern MP, Lazo JS, Sharlow ER, Harich K, Kingston DGI. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:883–887. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bultel-Ponce VV, Debitus C, Berge JP, Cerceau C, Guyot M. J. Mar. Biotechnol. 1998;6:233–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagle DG, McClatchey WC, Gerwick WH. J. Nat. Prod. 1992;55:1013–1017. doi: 10.1021/np50085a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neuhof T, Schmieder P, Preussel K, Dieckmann R, Pham H, Bartl F, von Dohren H. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:695–700. doi: 10.1021/np049671r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalinovskaya NI, Kuznetsova TA, Ivanova EP, Romanenko LA, Voinov VG, Huth F, Laatsch H. Mar. Biotechnol. 2002;4:179–188. doi: 10.1007/s10126-001-0084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orjala J, Nagle D, Gerwick WH. J. Nat. Prod. 1995;58:764–768. doi: 10.1021/np50119a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suntornchashwej S, Suwanborirux K, Koga K, Isobe M. Chem. Asian J. 2007;2:114–122. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tan LT, Okino T, Gerwick WH. J. Nat. Prod. 2000;63:952–955. doi: 10.1021/np000037x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gu W, Cueto M, Jensen PR, Fenical W, Silverman RB. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:6535–6541. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perez Baz J, Canedo LM, Fernandez Puentes JL, Silva Elipe MV. J. Antibiot. 1997;50:738–741. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.50.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams DE, Austin P, Diaz-Marrero AR, Soest RV, Matainaho T, Roskelley CD, Roberge M, Andersen RJ. Org. Lett. 2005;19:4173–4176. doi: 10.1021/ol051524c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

General experimental procedures, acetylation reaction conditions, lipase reaction conditions, 1H spectra of 1 and 2, 13C spectrum of 1, 1H and 13C spectra of 5–;9, table of assignments for 9, 1H and HSQC spectra of eudistomide B epimers (2, 12), 1H and HSQC spectra of eudistomide B acetate ester epimers (13, 14), and 1H and HSQC spectra of the lipase reaction products (2, 13, 14). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.