Abstract

Study Objectives:

We hypothesized that the non-benzodiazepine hypnotic zolpidem would improve idiopathic central sleep apnea (ICSA) by enhancing sleep stability, resulting in fewer arousals, which in turn would lessen oscillation in arterial CO2 and produce a decrease in central apnea/hypopnea events. Zolpidem might also decrease ventilatory control responsiveness during arousals, thereby reducing hyperpnea, hypocapnia, and subsequent apneas.

Patients and Study Design:

This was a case series in which all patients with ICSA seen in the Henry Ford Sleep Disorders Clinic from January 1, 2004, to December 31, 2006, were offered zolpidem, as well as other therapeutic options of acetazolamide, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel pressure support, or assist control ventilatory support. Those 20 patients who chose zolpidem were prescribed 10 mg at bedtime

Measurements and Results:

After a therapeutic trial averaging 9 weeks, a follow-up polysomnogram showed that the overall apnea/hypopnea index (AHI) and central AHI (CAHI) decreased, 30.0 ± 18.1 (SD) to 13.5 ± 13.3 (p = 0.001), and 26.0 ± 17.2 to 7.1 ± 11.8 (p < 0.001), respectively, without an overall change in obstructive AHI or arterial oxygen saturation. The total number of arousals per hour decreased with zolpidem use, 24.0 ± 11.6 to 15.1 ± 7.7 (p < 0.001), leading to a significant improvement in sleep efficiency. There was a positive correlation between the decrease in CAHI and the arousal index. Consistent with the hypnotic effect of zolpidem, sleep latency decreased, stage 1 sleep percentage decreased, and stage 2 percentage increased (all significant), without changes in stage 3-4 or REM sleep. Excessive daytime sleepiness, measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) decreased from 13 ± 5 to 8 ± 5 (p < 0.001). Three patients experienced a significant increase in obstructive events.

Conclusion:

In an open-label trial, ICSA patients studied experienced a decrease in central apnea/hypopneas with zolpidem. They also had improved sleep continuity and decreased subjective daytime sleepiness, without a worsening of oxygenation or obstructive events in the majority of patients. However, in the absence of a randomized, controlled trial, zolpidem cannot be recommended for treatment of ICSA at this time.

Citation:

Quadri S; Drake C; Hudgel DW. Improvement of idiopathic central sleep apnea with zolpidem. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5(2):122-129.

Keywords: Central sleep apnea, sleep disordered breathing, zolpidem

Idiopathic central sleep apnea (ICSA) is characterized by periodic episodes of apnea or hypopnea resulting from decreased neural input to the respiratory motor neurons.1–4 ICSA patients usually present with complaints of snoring, witnessed apneas, restless sleep, insomnia and/or excessive daytime sleepiness.1–5 Although the general population prevalence of ICSA is not known, within a sleep center population the prevalence has been reported to be 4% to 7% and within an apneic population to be 17%.1,2 A higher prevalence of ICSA has been reported in older patient populations.6,7

ICSA has no proven standardized treatment;5 CPAP is effective in some, but not in all patients.5,8,9 Therefore, some pharmacological agents have been used, but usually in forms of CSA other than ICSA. The respiratory stimulants theophylline and acetazolamide have been shown to improve CSA in some10 but not all studies11,12 of high altitude climbers. In this situation acetazolamide, temazepam and zolpidem have been shown to decrease nocturnal arousals and improve sleep continuity even when the sleep disordered breathing is not improved.11,12 Theophylline improved the CSA and periodic breathing found in congestive heart failure patients,13 but theophylline use during sleep is limited by its stimulant effect. Acetazolamide has been shown to improve the central apnea frequency in patients with ICSA.1,14,15 However, its usefulness may be limited because obstructive apneas have been found to worsen with this agent by some15 but not all investigators.1

Benzodiazepines have been tested for their effects on ICSA in a limited number of patients. Guilleminault et al showed an improvement in CAHI with clonazepam in 2 patients.16 Bonnet et al conducted a randomized crossover study using triazolam in 5 patients with ICSA and showed a reduction in the CAHI and the total number of arousals.17

We hypothesized that the non-benzodiazepine hypnotic zolpidem would stabilize sleep, resulting in fewer arousals, which, in turn, would lessen oscillation in arterial CO2 and produce a decrease in central apnea/hypopnea events. Zolpidem has a favorable safety profile in a range of clinical situations.18–22 It did not lead to enough pharyngeal muscle hypotonia to cause significant obstructive apneas in heavy non-apneic snorers.20 Zolpidem did not suppress ventilatory drive, produce hypercapnia or hypoxemia in those with hypercapnic obstructive lung disease.21,22 Similarly, it did not result in further hypoxemia in the hypoxemic environment of simulated high altitude.12 To objectively evaluate the response of ICSA to this agent and to make certain that zolpidem did not worsen obstructive apneas or hypoxemia, we tested the effect of zolpidem in patients with uncomplicated ICSA, in whom we were able to conduct a follow-up polysomnogram on treatment.

METHODS

This was an open label trial of zolpidem administered to 20 patients with newly diagnosed ICSA. ICSA was defined by a CAHI ≥ 10 events per hour of sleep, and an obstructive AHI ≤ 5 events per hour of sleep. An apnea was defined as a cessation or reduction in peak oronasal airflow ≥ 80% of baseline, lasting ≥ 10 s. Hypopnea was defined as a reduction in peak oronasal airflow ≥ 50%, ≤ 80% of baseline for ≥ 10 s, along with a ≥ 4% drop in SaO2 relative to pre-event baseline value. Apneas or hypopneas were determined to be central events if respiratory effort, as measured by piezoelectric crystal thoracic and abdominal belts decreased parallel with flow during the apnea or the hypopnea. Apneas or hypopneas were defined as obstructive events if oronasal airflow was decreased as described above, but the thoracic and abdominal breaths continued at the baseline amplitude, or increased in amplitude at any time during the period of decreased airflow. The AHI was calculated for all events relative to total sleep time and documented separately for central (CAHI) and obstructive (OAHI) events. Central apneas and hypopneas comprised the CAHI and obstructive apneas and hypopneas plus mixed apneas and hypopneas comprised the OAHI.

Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria included clinical or echocardiographic diagnosis of systolic heart failure (ejection fraction < 40%), diastolic cardiac dysfunction, or a history of transient ischemic attack or stroke. Those with a typical pattern of Cheyne Stokes respiration during sleep were excluded because of a high likelihood of underlying cardiac or neurologic disease. Patients with obstructive sleep apnea with an AHI ≥ 5 events per hour prior to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device use, or a history of restless legs syndrome/periodic leg movements were also excluded. Patients with prior use of a sedative or hypnotic agent including zolpidem or other pharmacological agents for ICSA, including acetazolamide, theophylline, medroxyprogesterone, any opiate, oxygen, or CPAP therapy were also excluded from the study to exclude comparative bias when evaluating subjective response to zolpidem. Finally, patients with hypercapnic lung disease or those with obesity hypoventilation syndrome were excluded.

Protocol

Patients were referred from primary care and subspecialty physicians to the sleep clinic. Initial consultation included detailed history, questionnaire data including baseline Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), physical examination, followed by an 8-h diagnostic polysomnogram (PSG). Patients were diagnosed with ICSA if they had excessive daytime sleepiness (ESS score ≥ 10 [maximum ESS = score of 24]) and had a CAHI ≥ 10 events/hour and an obstructive apnea index < 5 events/hour. Within one week of the polysomnogram, and with no intervening treatment, ICSA patients were offered zolpidem treatment after reviewing the potential benefits, risks, and known outcomes of this therapy and of alternative therapies: oxygen, CPAP, bilevel pressure ventilation, and acetazolamide. Patients who consented to take zolpidem were instructed to take 10 mg orally, approximately 30 minutes before bedtime each night, including the night of the follow-up polysomnogram. Outpatient monitoring was conducted every 3 weeks to assess patients for side effects of treatment and for evaluation of daytime sleepiness, using the ESS. Patients were instructed that 6–10 weeks following zolpidem initiation, a repeat nighttime 8-h PSG would be scheduled to assess the effects of treatment.

Overnight Recording

Nocturnal polysomnographic assessment using the Grass Aurora system (Grass Telefactor, West Warwick, RI) was performed in a standard manner23 consisting of an electroencephalogram (EEG), (O1/A2, O2/A1, C4/A1, C3/A2), an electro-oculogram (EOG), a submental electromyogram (EMG), an anterior tibialis EMG, and an electrocardiogram. Nasal-oral airflow was measured using thermocouples. Abdominal and thoracic respiratory movements were recorded with respiratory effort belts using piezoelectric crystal sensors. Transcutaneous oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2) was monitored with finger pulse oximetry (Ohmeda 3900, recording at 30 Hz, with a running 12-sec average). A recording of sleep position using video monitoring was done, and snoring was recorded using a snore sensor (anterior cervical microphone). Experienced sleep technologists, blinded to the study protocol, scored sleep recordings. Sleep architecture was analyzed according to the standard criteria.23

Statistics

The means and standard deviations of the continuous variables assessed (before and during zolpidem therapy) were compared using paired t-tests. The results were expressed as mean ± SD and /or range of values. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to analyze the relationships between changes in arousal indices and changes in apnea/hypopnea indices seen with treatment. The criterion for significance (α) was set at 5%. All analyses were performed using the statistical software (SPSS v.10.1, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Approval was obtained from the institutional review board at our institute for this study.

RESULTS

Participants and Follow-Up Data

Patients were recruited from January 2004 through December 2006. Of 28 patients with ICSA who met study inclusion/exclusion criteria for treatment with zolpidem, 20 patients completed the observation period. One patient had a slightly lower CAHI than called for, 8.6 events/h, and one had a slightly higher OAHI than protocol, 14.5 events/h. Three had an ESS less than 10 but met other inclusion criteria. Eight patients did not complete the study protocol for the following reasons: After initially agreeing, one patient refused to participate in the study, 2 patients did not fill their zolpidem prescriptions, and one patient stopped using the medication after one week, as he experienced increased appetite, which disappeared after stopping the medication. One patient did not complete the course of therapy after requiring an ICU stay for respiratory failure from community-acquired pneumonia. Three patients were lost to follow up after being included in the study.

The follow-up ESS and PSG were obtained 9 ± 7 weeks after initiation of zolpidem.

Demographics

Twenty subjects, 17 males and 3 females completed the trial. The racial profile was 15 Caucasians, 4 African Americans, and one Hispanic. The average age of the patients was 55 ± 9 years (range 28–68). The BMI was 36 ± 7 kg/meter2, which did not change with the zolpidem administration. Eleven patients consumed alcohol socially, and there were 8 regular smokers.

Clinical Picture

The most common presenting complaint was excessive daytime sleepiness, found in 14 patients. Five patients had difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep as their presenting complaint. One patient primarily complained of fatigue, a symptom also present as a secondary complaint in 7 other patients. Eleven patients gave a history of bed-partner witnessed apneas; 8 of these patients complained of being habitual snorers.

Respiratory Variables

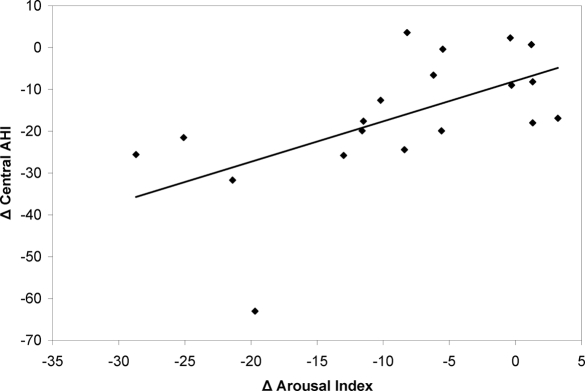

Respiratory variable data are presented in Tables 1 and 2. On zolpidem, the overall (central + obstructive events) AHI decreased from 30.0 ± 18.1 to 13.5 ± 13.3 (p = 0.0001). The CAHI decreased from 26.0 ± 17.2 to 7.1 ± 11.8 (p < 0.0001) with treatment. The decreased CAHI was composed of a decrease in the central apnea index from 13.6 ± 19.3 to 2.3 ± 4.5 events/h and a decrease in the central hypopnea index from 12.5 ± 6.5 to 4.9 ± 8.4 events/h. Four patients had complete resolution of the central events; 12 patients had a reduction in CAHI to < 5 events/h; and 18 of the 20 patients had > 50% reduction of CAHI. The total arousal index decreased from 24.0 ± 11.6 to 15.1 ± 7.7/h (p < 0.001) with treatment. The Pearson correlation coefficient between the change in CAHI and change in arousal index with treatment was 0.59, p < 0.0004. The self reported ESS score improved considerably on zolpidem treatment, decreasing from 12.8 ± 4.5 to 7.5 ± 5.2 (p < 0.001). There was not a significant correlation between changes in ESS and changes in CAHI.

Table 1.

Summary Respiratory Indices and Sleepiness Before and After Zolpidem in CSA Patients

| Patient | Apnea Hypopnea Index* |

Central Apnea Hypopnea Index |

Obstructive Apnea Hypopnea Index |

Arousal Index |

Epworth Sleepiness Score |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change |

| 1 | 22.8 | 2.9 | −19.9 | 19.1 | 2.5 | −16.6 | 3.7 | 0.4 | −3.3 | 10.9 | 5.3 | −5.6 | 17.0 | 7.0 | −10.0 |

| 2 | 67.8 | 53.5 | −14.3 | 53.3 | 48.6 | −4.7 | 14.5 | 4.9 | −9.6 | ** | ** | ** | 13.0 | 10.0 | −3.0 |

| 3 | 38.8 | 7.1 | −31.7 | 32.9 | 6.5 | −26.4 | 5.9 | 0.6 | −5.3 | 49.3 | 27.9 | −21.4 | 18.0 | 4.0 | −14.0 |

| 4 | 10.2 | 3.6 | −6.6 | 8.6 | 2.6 | −6.0 | 1.6 | 1.0 | −0.6 | 22.0 | 15.8 | −6.2 | 17.0 | 6.0 | −11.0 |

| 5 | 18.5 | 0.9 | −17.6 | 17.3 | 0.9 | −16.4 | 1.2 | 0.0 | −1.2 | 23.6 | 12.1 | −11.5 | 17.0 | 7.0 | −10.0 |

| 6 | 19.1 | 21.4 | 2.3 | 14.6 | 17.9 | 3.3 | 4.5 | 3.5 | −1.0 | 26.1 | 25.7 | −0.4 | 17.0 | 13.0 | −4.0 |

| 7 | 36.6 | 11.0 | −25.6 | 35.2 | 5.2 | −30.0 | 1.4 | 5.8 | 4.4 | 46.7 | 18.0 | −28.7 | 10.0 | 7.0 | −3.0 |

| 8 | 26.3 | 6.4 | −19.9 | 22.0 | 2.7 | −19.3 | 4.3 | 3.7 | −0.6 | 26.6 | 15.0 | −11.6 | 8.0 | 1.0 | −7.0 |

| 9 | 31.9 | 13.9 | −18.0 | 22.2 | 10.0 | −12.2 | 9.7 | 3.9 | −5.8 | 4.7 | 6.0 | 1.3 | 18.0 | 17.0 | −1.0 |

| 10 | 23.4 | 27.0 | 3.6 | 18.1 | 0.0 | −18.1 | 5.3 | 27.0 | 21.7 | 25.9 | 17.7 | −8.2 | 7.0 | 5.0 | −2.0 |

| 11 | 10.4 | 10.0 | −0.4 | 10.4 | 1.3 | −9.1 | 0.0 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 18.4 | 12.9 | −5.5 | 17.0 | 16.0 | −1.0 |

| 12 | 28.0 | 28.7 | 0.7 | 15.7 | 1.2 | −14.5 | 12.3 | 27.5 | 15.2 | 31.0 | 32.2 | 1.2 | 7.0 | 3.0 | −4.0 |

| 13 | 86.9 | 23.9 | −63.0 | 84.7 | 23.1 | −61.6 | 2.2 | 0.8 | −1.4 | 33.9 | 14.2 | −19.7 | 12.0 | 2.0 | −10.0 |

| 14 | 26.8 | 18.6 | −8.2 | 26.7 | 0.1 | −26.6 | 0.1 | 18.5 | 18.4 | 11.4 | 12.7 | 1.3 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 2.0 |

| 15 | 25.8 | 1.4 | −24.4 | 25.0 | 0.6 | −24.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 12.4 | 4.0 | −8.4 | 3.0 | 0.0 | −3.0 |

| 16 | 26.0 | 0.2 | −25.8 | 23.7 | 0.0 | −23.7 | 2.3 | 0.2 | −2.1 | 21.9 | 8.9 | −13.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 0.0 |

| 17 | 16.2 | 3.6 | −12.6 | 16.2 | 3.6 | −12.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18.5 | 8.3 | −10.2 | 10.0 | 6.0 | −4.0 |

| 18 | 29.2 | 7.7 | −21.5 | 28.2 | 0.0 | −28.2 | 1.0 | 7.7 | 6.7 | 35.1 | 10.0 | −25.1 | 16.0 | 2.0 | −14.0 |

| 19 | 21.3 | 4.4 | −16.9 | 13.2 | 0.6 | −12.6 | 8.1 | 3.8 | −4.3 | 15.5 | 18.7 | 3.2 | 12.0 | 7.0 | −5.0 |

| 20 | 33.7 | 24.7 | −9.0 | 33.5 | 15.3 | −18.2 | 0.2 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 22.3 | 22.0 | −0.3 | 10.0 | 8.0 | −2.0 |

| Mean ± | 30.0 ± | 13.5 ± | −16.4 ± | 26.0 ± | 7.1 ± | −18.9 ± | 4.0 ± | 6.4 ± | 2.5 ± | 24.0 ± | 15.1 ± | −8.4 ± | 12.8 ± | 7.5 ± | −5.3 ± |

| SD | 18.1 |

13.3 |

14.9 | 17.2 |

11.8 |

13.2 | 4.2 |

8.4 |

8.4 | 11.6 |

7.7 |

9.4 | 4.5 |

5.2 |

4.7 |

| P-value | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.21 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

All indices - number of events/hours of TST (total sleep time)

No Data. Polysomnogram study from another institution.

Table 2.

Distribution of Apnea and Hypopnea Types Before and After Zolpidem in CSA Patients

| Patient Number | Obstructive Apnea Index* |

Obstructive Hypopnea Index |

Central Apnea Index |

Central Hypopnea Index |

Mixed Apnea Hypopnea Index |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change | |

| 1 | 3.7 | 0.0 | −3.7 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 13.7 | 0.0 | −13.7 | 5.4 | 2.5 | −2.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 10.6 | 2.1 | −8.5 | 39.4 | 13.8 | −25.6 | 13.9 | 34.8 | 20.9 | 3.5 | 0.0 | −3.5 |

| 3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 24.0 | 3.4 | −20.6 | 8.9 | 3.1 | −5.8 | 5.3 | 0.3 | −5.0 |

| 4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | −0.2 | 2.1 | 0.0 | −2.1 | 6.5 | 2.6 | −3.9 | 0.4 | 0.0 | −0.4 |

| 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 | −1.2 | 3.4 | 0.1 | −3.3 | 13.9 | 0.8 | −13.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 6 | 0.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 0.5 | −2.1 | 3.3 | 0.3 | −3.0 | 11.3 | 17.6 | 6.3 | 1.7 | 0.7 | −1.0 |

| 7 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 14.2 | 1.5 | −12.7 | 21.0 | 3.7 | −17.3 | 1.2 | 0.3 | −0.9 |

| 8 | 0.9 | 0.0 | −0.9 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 0.0 | −2.3 | 19.7 | 2.7 | −17.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | −0.6 |

| 9 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 6.9 | 1.0 | −5.9 | 14.9 | 1.0 | −13.9 | 7.3 | 9.0 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | −0.2 |

| 10 | 3.3 | 0.0 | −3.3 | 1.4 | 27.0 | 25.6 | 10.5 | 0.0 | −10.5 | 7.6 | 0.0 | −7.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | −0.6 |

| 11 | 0.0 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | −0.4 | 10.0 | 1.3 | −8.7 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 12 | 1.1 | 0.0 | −1.1 | 6.6 | 23.9 | 17.3 | 10.5 | 0.3 | −10.2 | 5.2 | 0.9 | −4.3 | 4.6 | 3.6 | −1.0 |

| 13 | 1.2 | 0.8 | −0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 83.5 | 15.0 | −68.5 | 1.2 | 8.1 | 6.9 | 0.8 | 0.0 | −0.8 |

| 14 | 0.1 | 14.5 | 14.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.7 | 0.1 | −12.6 | 14.0 | 0.0 | −14.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| 15 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 10.0 | 0.0 | −10.0 | 15.0 | 0.6 | −14.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 | −0.4 |

| 16 | 1.3 | 0.0 | −1.3 | 1.0 | 0.2 | −0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 23.7 | 0.0 | −23.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 17 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 16.2 | 0.0 | −16.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 18 | 1.0 | 0.5 | −0.5 | 0.0 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 2.5 | 0.0 | −2.5 | 25.7 | 0.0 | −25.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 19 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 8.1 | 3.6 | −4.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 12.9 | 0.6 | −12.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 20 | 0.2 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 23.7 | 6.0 | −17.7 | 9.8 | 9.3 | −0.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Mean ± | 0.9 ± | 1.7 ± | 0.9 ± | 2.1 ± | 4.2 ± | 2.1 ± | 13.6 ± | 2.3 ± | −11.3 ± | 12.5 ± | 4.9 ± | −7.6 ± | 1.0 ± | 0.5 ± | −0.5 ± |

| SD | 1.1 |

3.3 |

3.7 | 3.2 |

7.6 |

7.7 | 19.3 |

4.5 |

15.5 | 6.5 |

8.4 |

11.2 | 1.6 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

| P-value | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.23 | ||||||||||

All indices - number of events/hours of TST (total sleep time)

For the group no significant worsening of obstructive events occurred with zolpidem (pre 4.0 ± 4.2, with zolpidem 6.4 ± 8.4) (p = 0.274). However, in seven patients the OAHI increased with therapy, but the overall AHI dropped except in 2 of these patients in whom the AHI increased by 1 and 3 events/h, respectively. The mean lowest NREM and REM arterial oxygen saturations did not change with zolpidem, from 88% ± 4% and 88% ± 3% to 88% ± 3%, and 88% ± 3% respectively. The percentage total sleep time (TST) spent in the lateral or supine body positions was also not different with treatment (p = 0.237).

Sleep Parameters

While on zolpidem, mean sleep latency decreased from 18 ± 15 to 11 ± 7 min (p = 0.011). Sleep efficiency also improved significantly (p < 0.006) (Table 3). There was a reduction in stage 1 sleep (p < 0.011) along with an increase in stage 2 sleep (p < 0.013) (Table 4). Stage 3/4 sleep (p = 0.592) and REM sleep (p = 0.898) percentages of total sleep time did not change (Table 4).

Table 3.

Sleep Summary Before and After Zolpidem in CSA Patients

| Patient Number | Total Sleep Time (hours) |

Sleep Efficiency (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change | |

| 1 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 0.2 | 87.1 | 90.3 | 3.2 |

| 2 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 0.3 | 70.0 | 74.0 | 4.0 |

| 3 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 42.2 | 48.3 | 6.1 |

| 4 | 5.3 | 6.9 | 1.6 | 65.8 | 85.9 | 20.1 |

| 5 | 6.0 | 7.4 | 1.4 | 75.1 | 92.2 | 17.1 |

| 6 | 5.2 | 5.8 | 0.5 | 65.6 | 72.0 | 6.4 |

| 7 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 0.8 | 86.8 | 96.7 | 9.9 |

| 8 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 0.8 | 65.9 | 75.7 | 9.8 |

| 9 | 6.2 | 5.5 | −0.7 | 77.3 | 68.4 | −8.9 |

| 10 | 5.0 | 5.9 | 0.9 | 62.7 | 73.6 | 10.9 |

| 11 | 5.7 | 7.3 | 1.6 | 70.7 | 90.9 | 20.2 |

| 12 | 5.3 | 6.9 | 1.6 | 66.7 | 86.3 | 19.6 |

| 13 | 7.5 | 5.2 | −2.3 | 94.0 | 65.0 | −29.0 |

| 14 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 0.3 | 92.1 | 96.4 | 4.3 |

| 15 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 1.2 | 67.6 | 82.2 | 14.6 |

| 16 | 3.1 | 6.5 | 3.3 | 39.1 | 80.8 | 41.7 |

| 17 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 0.4 | 90.8 | 95.9 | 5.1 |

| 18 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 1.1 | 63.7 | 77.6 | 13.9 |

| 19 | 3.5 | 6.7 | 3.2 | 43.2 | 83.5 | 40.3 |

| 20 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 0.6 | 79.1 | 86.9 | 7.8 |

| Mean ± SD | 5.6 ± 1.3 |

6.5 ± 1.0 |

0.9 ± 1.2 | 70.3 ± 16.0 |

81.0 ± 12.2 |

10.9 ± 15.1 |

| P-value | 0.005 | 0.005 | ||||

Table 4.

Sleep Variables Before and After Zolpidem in CSA Patients

| Patient | % TST Stage 1 |

% TST Stage 2 |

% TST Stage 3, 4 |

% TST REM |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change | Baseline | Treated | Change |

| 1 | 14.3 | 9.0 | −5.3 | 63.5 | 63.9 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 22.2 | 27.0 | 4.8 |

| 2 | 26.4 | 17.9 | −8.5 | 73.6 | 82.1 | 8.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 55.1 | 46.2 | −8.9 | 44.9 | 52.0 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| 4 | 33.7 | 25.8 | −7.9 | 50.8 | 64.8 | 14.0 | 1.6 | 0.7 | −0.9 | 13.9 | 8.7 | −5.2 |

| 5 | 15.8 | 11.0 | −4.8 | 77.9 | 78.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 10.4 | 4.1 |

| 6 | 36.2 | 26.5 | −9.7 | 53.3 | 56.2 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.5 | 17.2 | 6.7 |

| 7 | 11.0 | 9.4 | −1.6 | 81.7 | 83.1 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 0.1 |

| 8 | 66.8 | 32.8 | −34.0 | 30.5 | 54.4 | 23.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 12.8 | 10.1 |

| 9 | 72.9 | 32.7 | −40.2 | 5.9 | 34.9 | 29.0 | 2.8 | 18.1 | 15.3 | 18.3 | 14.4 | −3.9 |

| 10 | 45.1 | 46.6 | 1.5 | 47.3 | 51.3 | 4.0 | 7.2 | 0.0 | −7.2 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| 11 | 22.8 | 19.3 | −3.5 | 61.8 | 76.8 | 15.0 | 4.4 | 1.6 | −2.8 | 11.0 | 2.3 | −8.7 |

| 12 | 62.1 | 40.6 | −21.5 | 28.3 | 51.8 | 23.5 | 1.5 | 0.0 | −1.5 | 8.1 | 7.6 | −0.5 |

| 13 | 4.2 | 5.9 | 1.7 | 95.8 | 94.1 | −1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 14 | 73.1 | 42.0 | −31.1 | 21.4 | 55.9 | 34.5 | 3.8 | 0.0 | −3.8 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 0.5 |

| 15 | 28.3 | 23.5 | −4.8 | 54.8 | 59.4 | 4.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | −0.2 | 16.7 | 17.1 | 0.4 |

| 16 | 69.0 | 15.8 | −53.2 | 15.5 | 69.6 | 54.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 15.5 | 14.6 | −0.9 |

| 17 | 43.1 | 21.4 | −21.7 | 35.6 | 49.0 | 13.4 | 4.3 | 4.1 | −0.2 | 16.9 | 25.5 | 8.6 |

| 18 | 39.1 | 78.7 | 39.6 | 52.3 | 7.4 | −44.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.6 | 13.9 | 5.3 |

| 19 | 39.6 | 23.0 | −16.6 | 23.0 | 63.1 | 40.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 37.4 | 13.5 | −23.9 |

| 20 | 38.1 | 40.8 | 2.7 | 42.9 | 47.5 | 4.6 | 12.1 | 1.6 | −10.5 | 6.9 | 10.0 | 3.1 |

| Mean ± | 39.8 ± | 28.4 ± | −11.4 ± | 48.0 ± | 59.8 ± | 11.8 ± | 1.9 ± | 1.3 ± | −0.6 ± | 10.2 ± | 10.4 ± | 0.2 ± |

| SD | 21.2 |

17.3 |

19.4 | 23.6 |

19.1 |

20.2 | 3.2 |

4.1 |

4.7 | 9.3 |

7.8 |

7.2 |

| P-value | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.6 | 0.9 | ||||||||

Individual Patient Responses

Although there was a dramatic decrease in central apneas/hypopneas as indicated in the group statistics, there were some interesting individual or subgroup responses to zolpidem worthy of note. For instance, 3 patients experienced small increases in the total AHI with treatment: from 19 to 21, from 23 to 27, and from 28 to 29. As indicated in Table 1, these increases were due to an increase in CAHI from 15 to 18 events/h in only one individual and increases in the OAHI of 5 to 27 and 12 to 28 in the latter 2 cases. However, in these 2 cases, there was a dramatic decrease in the number of central events, from 18 to 0 and 16 to 1, respectively. Of the 4 patients who had elimination of CSA with zolpidem, 3 had an increase in obstructive events, from 5 to 27, 0 to 19, and 1 to 8/h. This pattern also was seen in 2 of the 5 patients whose CAHI decreased to 1 event/h (Cases # 11 and # 12). One patient had a minimal decrease in CAHI, from 53 to 49 events/h, but had a reduction in obstructive events from 15 to 0 (Patient #2). Another patient had an OAHI ≥ 10, and the obstructive events increased to 28/h with treatment. We included one patient with a CAHI of 9 events/h in the study because he had clinically significant excessive daytime sleepiness with an ESS a score of 17. With zolpidem, this patient had a reduction of the AHI from 10 to 4 events/h, and an improvement in the ESS from 17 to 6. Four patients had CAHI > 10/h at the conclusion of the study. One was the only case whose CSA increased, from 15 to 18 events/h. The other three experienced > 50% reduction in the CAHI. Sixteen of 20 patients experienced an improvement in their ESS of > 1 point. One had had an increase from a score of 10 to 12, one had no change at a score of 17. Ten others had a decrease in the ESS score < 5 with therapy. One patient had significant esophageal reflux symptoms with zolpidem administration.

DISCUSSION

We found an improvement in ICSA in an open-label trial of zolpidem, in that the central apneas and hypopneas decreased significantly, and sleep variables and symptoms improved without any significant worsening of OSA or oxygenation in a group of 20 ICSA patients. Three patients did experience a moderately large increase in obstructive apnea/hypopneas of 22, 18, and 15 events/h. However, all 3 had a nearly equivalent decrease in central events, keeping the overall AHI close to the baseline value, +4, −8, and +1, respectively. The ESS scores decreased significantly for the group, but 11 patients had a decrease < 5 points on the ESS. However, one would not necessarily expect a large change in ESS score the closer the baseline value was to normal range of 8–10 points.

Although our results have not been confirmed by a blinded randomized trial, zolpidem appears to have some advantages over previously studied agents. Since zolpidem decreased arousals and improved sleep efficiency, it is preferred over theophylline, which likely would disrupt sleep. Since zolpidem did not worsen obstructive apnea significantly, except in the patients discussed above, zolpidem is preferred over acetazolamide, which increased the obstructive AHI in the 8 patients studied in one trial.15 Whether zolpidem would provide superior results relative to other benzodiazepines or non-benzodiazepine hypnotic agents would require direct comparison.

Although this study is an initial therapeutic trial and does not examine mechanisms, the results compel us to consider mechanisms, both those that may predispose individuals to ICSA and those responsible for the beneficial response to zolpidem in ICSA. Naturally, in sleep, ventilation may be more perturbed than during wakefulness.24,25 Three mechanisms that might contribute to the presence of the oscillatory breathing pattern of apnea-arousal-apnea pattern seen during sleep in ICSA are abnormalities in CO2 apnea threshold, ventilatory control loop gain, and sleep stability or arousability.26–35 Abnormalities in one or more of these variables may work in a synergistic or individual way to facilitate the presence of CSA in a given individual. The CO2 apnea threshold mechanism is basically a switch that can turn ventilation on or off during sleep.26,27 This mechanism attempts to maintain eucapnia during sleep at a PCO2 above the wakefulness level. When the apneic threshold is close to the sleep eucapnic level; only a minimal amount of hyperventilation is required to push PCO2 below this threshold during sleep and for a central apnea to occur—an unstable ventilatory state. Conversely, if the apneic threshold is at a lower PCO2, then more hyperventilation will be required to produce the central event—a more stable ventilatory state. Alternatively, if the fluctuations in ventilation are large, possibly because of intermittent arousals, the PCO2will fluctuate above and below the apneic threshold, producing an oscillatory pattern of breathing characterized by apnea/hypopnea alternating with hyperpnea.

The ventilatory control system may become involved in the sleep oscillatory breathing pattern associated with central apnea/hypopnea in that if the gain of this system is high; that is, the amount of change in ventilation that occurs with a given change in PCO2is high, then further hypocapnia and central apneas likely may occur.28 The occurrence of an arousal complicates the picture following a central apnea/hypopnea; although the CO2 apnea threshold mechanism will not be functional, the ventilatory control loop gain will be a major contributor to the post-apneic hyperventilation,29,30 such that the awake ventilatory drive loop gain, being higher than the gain during sleep, will contribute to a greater degree of hyperventilation and hypocapnia than would have occurred had there not been an arousal.

As stated, the occurrence of arousals plays a major role in the pathophysiology of ICSA. To this end, it has been hypothesized that there is a variation in the arousal threshold, or arousability, within the population and that patients with ICSA have a low arousal threshold,31,32 contributing to the oscillatory breathing in ICSA. This possibility was supported by Berthon-Jones et al. who showed an intersubject variability in the arousal response to hypercapnia.30 Women aroused at a lower PCO2 than men, and arousal occurred at a lower PCO2in REM sleep than NREM sleep. Arousals occurred less frequently in stage 3/4 sleep than in stage 2 NREM sleep in response to hypercapnia or airway obstruction.30–32 If a given patient's arousability is high (i.e., a small change in ventilation leads to an arousal), the tendency for oscillatory breathing and central apnea/hypopnea will be high.

In ICSA we propose that zolpidem diminishes the heightened gain of one or more of these mechanisms. Most obviously, zolpidem would be expected to diminish arousability. In healthy adults, Hedemark and Kronenberg33 found that flurazepam delayed arousal from hypercapnia, while Gothe et al34 did not. Bonnet et al demonstrated decreased arousals and central apnea/hypopneas in ICSA patients with triazolam.17 Thus, if arousals can be prevented or diminished, the tendency to have post-arousal apneas would be diminished. There is support for this proposed mechanism of action; in insomnia patients, zolpidem has been shown to decrease cyclic arousals and electroencephalographic signs of cyclic arousals in NREM sleep.35 However, the action of zolpidem on breathing abnormalities during sleep may be only partially dependent on its improvement in sleep stability.12 Zolpidem may decrease the ventilatory control loop gain, thereby decreasing the extent of the hyperpneic response to ventilatory stimulants, decreasing the tendency for hypocapnia and apnea/hypopnea and arousal to occur. How zolpidem might affect CO2apnea threshold is not known.

Limitations of the Study

We would like to emphasize that this study was a preliminary examination of the effect of zolpidem on ICSA. We acknowledge that the major limitations of this study are the lack of a placebo control and lack of systematic recruitment of consecutive patients with ICSA. Also, we did not evaluate any dose-response effect of zolpidem. As there was no significant worsening in oxygenation we can assume that the apnea count did not decrease because of a prolongation of the apnea/hypopneas, but apnea/hypopnea duration was not measured. The value of the finding of an improved subjective daytime sleepiness without a blinded protocol is limited, but the improved ESS scores are consistent with an improvement in respiratory and sleep variables observed. Regarding the use of ESS, an objective measurement of daytime sleepiness using a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) would have been a more accurate method for determining changes in daytime sleepiness than the ESS, which has inherent variability.36 However, use of the ESS was more convenient for patients. While the limited patient population (n = 20) is a concern, the magnitude of effect seen in even such a small group suggests potential clinical significance. Obviously, now that there are promising preliminary results, a study involving a larger patient group in a randomized, placebo-controlled double-blinded fashion is the next necessary step to verify the beneficial effect of zolpidem in ICSA. Further study is needed to evaluate the potential for obstructive apneas to appear with zolpidem administration, as occurred in 3 patients in this study.

Our ability to detect central hypopneas without esophageal or pharyngeal pressure measurements might be questioned. First, invasive esophageal or posterior pharyngeal techniques would disturb or limit sleep and not allow a valid comparison between the pre- and on-treatment polysomnograms. These techniques are valuable tools to evaluate mechanisms of respiratory abnormalities during sleep, but they have limited usefulness in a pharmacological study of sleep and breathing

In addition, it has been demonstrated previously that the combination of abdominal and thoracic strain gauges detect the majority of central events, verified by simultaneously recorded esophageal pressure,37 although this finding is disputed in a small minority, 9% of sleep apnea patients studied by Staats et al.38 With the addition of the oxygen desaturation requirement for the scoring of central hypopneas, excessive identification of central events would be lessened. The importance of the potential error in the measurement of central hypopneas is lessened by the fact that zolpidem produced a significant decrease in central apneas (Table 2). Central apneas and hypopneas decreased to a similar degree with zolpidem. Therefore, the study outcome would have been similar had we only scored apneas. In addition, the same measurement techniques were used prior to and during zolpidem therapy. Even if some hypopneas were missed or misclassified by our techniques, the same measurement and scoring techniques were used at the 2 testing points; with these same techniques, a decrease in central apneas, hypopneas, and overall AHI was found with zolpidem administration.

Another limitation is the clinical applicability of these data. Because of the preliminary nature of this study, we do not recommend that physicians use zolpidem in patients with central sleep apnea, especially those with a significant obstructive component, although the worsening in obstructive apnea was not always predictable from the baseline obstructive AHI. An increase in the obstructive apnea/hypopnea index was noted in 7 patients taking zolpidem, ranging from an increase of 4 to 22 events/h, with 3 patients having a significant increase of 22, 18, and 15 events/h. Since the central apnea/hypopnea index decreased a similar amount in these patients, the overall AHIs stayed close to the pre-treatment AHIs, or actually improved. Changes in AHI values for these 3 patients were +4, −8, and +1 events/h, respectively. Keeping these findings in mind, an on-therapy PSG would be mandatory even when symptoms are improved. At this time, it is unclear whether the residual OSA needs treatment. Caution is also recommended for use of zolpidem in any patients with respiratory disease, without close monitoring of sleep respiratory and oxygenation status.

In summary, in an open-label, uncontrolled study, in ICSA we have shown that the hypnotic zolpidem decreased the central apnea and hypopnea frequency, decreased arousals, improved sleep quality, and resulted in a subjective improvement in excessive daytime sleepiness without worsening oxygenation or obstructive apnea/hypopneas, except in 3 individuals who experienced a significant increase in obstructive events.

Figure 1.

Relationship between the change in central apnea/hypopnea index (central AHI) and the change in arousal index. Each point represents an individual subject. R = 0.59. In general, the central AHI and arousal index changed in parallel.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Hudgel has consulted for Invacare and Medtronics. Dr. Drake has received research support from Takeda and Cephalon; has participated in speaking engagements for Sanofi-Aventis, Sepacor, and Cephalon; Consultant for Sanofi-Aventis; and has consulted for Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Quadri has indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.DeBaker WA, Verbraeken J, Willemen M, Wittescale W, DeCock W, Van de Hening P. Central apnea index decreases after prolonged treatment with acetazolamide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:87–91. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.1.7812578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guilleminault C, van den Hoed J, Mitler M. Clinical overview of the sleep apnea syndromes. New York, NY: Alan R Liss; 1978. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley TD, Phillipson EA. Central sleep apnea. Clin Chest Med. 1992;13:493–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roehrs T, Conway W, Wittig R. Sleep complaints in patients with sleep-related respiratory disturbances. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:520–23. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley TD, McNicholas WT, Rutherford R. Clinical and physiologic heterogeneity of the central sleep apnea syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:217–21. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carskadon M, Dement W. Respiration during sleep in the aged human. J Gerontol. 1981;36:420–3. doi: 10.1093/geronj/36.4.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bixler E, Vgontzas A, Ten Have T, Tyson K, Kales A. Effects of age on sleep apnea in men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:144–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9706079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Issa FG, Sullivan CE. Reversal of central sleep apnea using nasal CPAP. Chest. 1986;90:165–71. doi: 10.1378/chest.90.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffstein V, Slutsky AS. Central sleep apnea reversed by continuous positive airway pressure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:1210–2. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.5.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer R, Lang SM, Leiti M, Thiere M, Steiner U, Huber RM. Theophylline and acetazolamide reduce sleep-disordered breathing at high altitude. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:47–52. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00113102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicholson AN, Smith PA, Stone BM, Bardwell AR, Coote JH. Altitude insomnia: studies during an expedition to the Himalayas. Sleep. 1988;11:354–61. doi: 10.1093/sleep/11.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaumont M, Batejat D, Coste O, et al. Effect of zolpidem and zaleplon on sleep, respiratory patterns and performance at a simulated altitude of 4,000 m. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;49:154–62. doi: 10.1159/000076723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Wexler L, Liming JD, Lindower P, Roselle GA. Effect of theophylline on sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:562–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White D, Zwillich C, Pickett C. Central sleep apnea: improvement with acetazolamide therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:1816–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharief I, Budihiraja R, Hudgel DW. Acetazolamide resolves central apnea but worsens obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2004;126:782S-b. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guilleminault C, Crowe C, Quera-Salva MA, Miles L, Partinen M. Periodic leg movements, sleep fragmentation and central sleep apnea in two cases: reduction with clonazepam. Eur Respir J. 1988;1:762–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonnet MH, Dexter JR, Arand DL. The effect of triazolam on arousal and respiration in central sleep apnea patients. Sleep. 1990;13:31–41. doi: 10.1093/sleep/13.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholson AN, Pascoe PA. Hypnotic activity of an imidazo-pyridine (zolpidem) Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1986;21:205–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1986.tb05176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holm KJ, Goa KL. Zolpidem. An update of its pharmacology, therapeutic efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of insomnia. Drugs. 2000;59:865–69. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059040-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quera-Salva MA, Crowe McCann CJ, Frik M, Borderies P, Meyer P. Effect of zolpidem on sleep architecture, night time ventilation, daytime vigilance and performance in heavy snorers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;39:539–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb04301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murciano D, Amengaud MH, Cramer PH, et al. Acute effect of zolpidem, triazolom and flunitrazepam on arterial blood gases on control of breathing in severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 1993;6:625–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steens RD, Pouliot Z, Millar TW, Kryger MH, George CF. Effect of zolpidem and triazolam on sleep and respiration in mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Sleep. 1993;16:318–26. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring systems for sleep stages of human subjects. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1968. NIH Publication No 204. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillipson EA. Control of breathing during sleep. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118:909–39. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.118.5.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Longobardo GS, Gothe B, Goldman MD, Cherniak NS. Sleep apnea considered as a control system instability. Respir Physiol. 1982;50:311–33. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dempsey JA, Skatrud JB. A sleep-induced apneic threshold and its consequences. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;133:1163–70. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.6.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowley JA, Zhou XS, Diamond MP, Badr MS. The determinants of the apnea threshold during NREM sleep in normal subjects. Sleep. 2006;29:95–103. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naughton M, Bernard D, Tam A, Rutherford R, Bradley TD. Role of hyperventilation in the pathogenesis of central sleep apneas in patients with congestive heart failure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:330–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solin P, Roebuck T, Johns DP, Walters H, Naughton MT. Peripheral and central ventilatory responses in central sleep apnea with and without congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2194–200. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2002024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berthon-Jones M, Sullivan CE. Ventilation and arousal responses to hypercapnia in normal sleeping humans. J Appl Physiol. 1984;57:59–67. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berry RB, Gleeson K. Respiratory arousal from sleep: mechanisms and significance. state of the art review. Sleep. 1997;20:654–75. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.8.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dingli K, Fietze I Assimakopoulos T, Quispe-Bravo S, Witt C, Douglas NJ. Arousability in sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome patients. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:733–40. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00262002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hedemark LL, Kronenberg RS. Flurazepam attenuates the arousal response to CO2, during sleep in normal subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:980–3. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.6.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gothe B, Cherniack NS, Williams L. Effect of hypoxia on ventilation and arousal responses to CO2, during NREM sleep with and without flurazepam in young adults. Sleep. 1986;9:24–37. doi: 10.1093/sleep/9.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parrino L, Smerieri A, Gigla F, Milioli G, De Paolis F, Terzano MG. Polysomnographic study of intermittent zolpidem treatment in primary sleep maintenance insomnia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2008;31:40–50. doi: 10.1097/wnf.0b013e3180674e0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen AT, Baltzan MA, Small D, Wolkove N, Guillon S, Pallayew M. Clinical reproducibility of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:170–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boudewyns A, Willemen M, Wagemans M, De Cock W, Van de Heyning P, De Backer W. Assessment of respiratory effort by means of strain gauges and esophageal pressure swings: a comparative study. Sleep. 1997;20:168–70. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staats BA, Bonekat HW, Harris CD, Offord KP. Chest wall motion in sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;130:59–63. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]