Abstract

The MEP1A gene, located on human chromosome 6p (mouse chromosome 17) in a susceptibility region for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), encodes the α-subunit of metalloproteinase meprin A, which is expressed in the intestinal epithelium. This study shows a genetic association of MEP1A with IBD in a cohort of ulcerative colitis (UC) patients. There were four single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the coding region (P = 0.0012–0.04), and one in the 3′-untranslated region (P = 2×10−7) that displayed associations with UC. Moreover, meprin-α mRNA was decreased in inflamed mucosa of IBD patients. Meprin-α knockout mice exhibited a more severe intestinal injury and inflammation than their wild-type counterparts following oral administration of dextran sulfate sodium. Collectively, the data implicate MEP1A as a UC susceptibility gene and indicate that decreased meprin-α expression is associated with intestinal inflammation in IBD patients and in a mouse experimental model of IBD.

INTRODUCTION

The two major forms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD), are caused by genetic and environmental factors that affect the interaction between host and microflora.1 Several IBD susceptibility genes have been identified,2,3 and linkage analyses have implicated multiple regions within the human genome, including an area on chromosome 6p, IBD3, that contains the HLA region, and also harbors the meprin-α gene, MEP1A.4,5

Meprins are zinc metalloproteinases that are highly expressed in the epithelial cells of the human and mouse intestine, and are found membrane bound and/or secreted into the lumen of the intestine.6,7 In addition to the abundant expression in the epithelium, meprins are expressed in human intestinal lamina propria leukocytes and in mouse mesenteric lymph nodes both in the presence and absence of intestinal inflammation.8-10

Meprins belong to the superfamily of ‘metzincins’ that include the evolutionarily related families of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs), serralysins, ADAMs, and astacins.11 Meprins are unique metalloproteinases in terms of their non-catalytic domains, expression patterns, substrate specificity, and endogenous inhibitors.12-14

Meprins are oligomers that consist of two subunits, α and/or β, that are encoded on different chromosomes (α on human chromosome 6 and mouse chromosome 17; β on human and mouse chromosome 18).5,15-18 Both the subunits have proteolytic activity and are capable of degrading diverse proteins, including extracellular matrix components, such as collagen IV laminin, nidogen, and fibronectin, but the subunits have different peptide bond specificities and peptide substrates.13,19

In this study, complementary approaches were used to investigate the role of meprin-α in IBD. These included a case–control association study of MEP1A polymorphisms in IBD, a study of meprin-α expression in the intestinal mucosa of IBD patients, as well as an examination of the functional consequences of a lack of the meprin-α subunit using meprin αKO mice. Wild-type (WT) and αKO mice challenged with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) elicited an experimental model of IBD that was more severe in the αKO mice. The data presented here strongly implicate MEP1A as an IBD susceptibility gene.

RESULTS

Genetic association of MEP1A with IBD

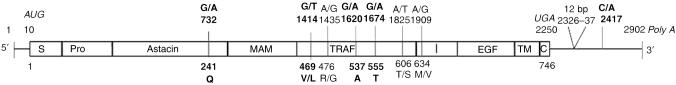

To identify polymorphisms in the MEP1A gene, all 14 exons were sequenced in 24 patients: 6 patients with UC, 6 with CD (none of whom carried any of the three common CD-associated NOD2/CARD15 variants), and 12 celiac disease patients. Eight single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and one polymorphism consisting of a 12-nucleotide (12 nt) insert were found (Table 1a, Figure 1). All nine polymorphisms were genotyped in 379 UC and 380 CD patients as well as in 372 healthy controls. The human genome contains multiple copies of MEP1A-like sequences on chromosome 9.20 Owing to the presence of these pseudogenes that share high sequence similarities with the meprin-α gene on chromosome 6, a MEP1A-specific sequencing strategy was developed. The genotype data and detailed information are summarized in Supplementary Table S1 online. A pairwise linkage disequilibrium analysis indicated strong linkage disequilibrium across the MEP1A gene (Supplementary Figure S1 online). Analysis of allele frequencies showed moderate, but statistically significant, associations with UC for four synonymous SNPs in the coding regions of the gene (P=0.0012, 0.03, 0.04, and 0.002, in exons 8, 11, 12, and 12, respectively) (Table 1b). One SNP in the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) (rs1059276 in exon 14) was most significantly associated with UC (P=2×10−7). The evidence for an association with CD was weaker, supported by the 3′-UTR only with a P-value of 0.003.

Table 1a.

MEP1A polymorphisms

| IDa | Exon | Position of aa | Domain | dbSNPb | Allelesc | Affected residue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 732 | 8 | 241 | Astacin | rs6920863d | G/A SNP | Syn Q |

| 1414 | 11 | 469 | TRAF | rs2274658d | G/T SNP | Non-syn V/L |

| 1435 | 11 | 476 | TRAF | rs12197930d | A/G SNP | Non-syn R/G |

| 1620 | 12 | 537 | TRAF | G/A SNP | Syn A | |

| 1674 | 12 | 555 | TRAF | rs4714952d | G/A SNP | Syn T |

| 1825 | 13 | 606 | I-domain | rs2297020 | A/T SNP | Non-syn T/S |

| 1909 | 13 | 634 | I-domain | rs2297019d | A/G SNP | Non-syn M/V |

| 2326 | 14 | — | 3′-UTR | 12-bp inserte | — | |

| 2417f | 14 | — | 3′-UTR | rs1059276d | C/A SNP | — |

Polymorphism ID according to position on mRNA GenBank acc. NM_005588 17 Nov 2006 (A of the AUG initiation codon=10).

Build 126 (Mar 2006).

Minor alleles are shown in bold.

Genotyped in HapMap Release #21a HapMap (Jan 2007).

Twelve-nt insert polymorphism: TTTGGGGCAGCT, minor allele is lack of the insert.

Nucleotide position with reference to mRNA GenBank acc. NM_005588, which lacks the 12-nt insert.

Figure 1.

An overview of MEP1A polymorphisms. The polymorphic sites in the human MEP1A gene are shown in the context of the multidomain structure of the meprin-α subunit. Meprin protein domains are S, signal peptide; Pro, propeptide; Astacin, catalytic protease domain; MAM, meprin/A5-protein/protein-tyrosine phosphate μ; TRAF, TNF-α receptor-associated factor; I, inserted; EGF, epidermal growth factor; TM, transmembrane; and C, cytosolic tail. The AUG start and UGA stop codons and Poly A are italicized. The SNPs and the 12-bp insert are indicated by their nucleotide positions. Affected amino-acid residues and their position in the protein sequence are shown below the subunit structure. UC-associated SNPs are highlighted in bold. Reference mRNA sequence, GenBank NM_005588, which lacks the 12-bp insert. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Table 1b.

MEP1A minor allele frequencies in IBD vs. controls

| IDa | UC | CD | Controls | P-valueUCb | P-valueCDb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 732 | 0.433 | 0.362 | 0.349 | 0.0012 | 0.53 |

| 1414 | 0.402 | 0.353 | 0.338 | 0.03 | 0.59 |

| 1435 | 0.039 | 0.024 | 0.029 | 0.27 | 0.58 |

| 1620 | 0.015 | 0.036 | 0.033 | 0.04 | 0.8 |

| 1674 | 0.335 | 0.390 | 0.422 | 0.002 | 0.27 |

| 1825 | 0.258 | 0.264 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.58 |

| 1909 | 0.256 | 0.258 | 0.254 | 0.97 | 0.9 |

| 2326 | 0.349 | 0.372 | 0.396 | 0.1 | 0.42 |

| 2417c | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.392 | 2×10−7 | 0.003 |

CD, Crohn's disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Polymorphism ID according to position on mRNA GenBank acc. NM_005588 17 Nov 2006 (A of the AUG initiation codon=10).

Significant associations are highlighted in bold.

Nucleotide position with reference to mRNA GenBank acc. NM_005588, which lacks the 12-nt insert.

Allele frequencies for rs1059276 in our control group (risk allele frequency, 0.61) differed from those for Caucasians (the CEU population) in Hapmap (risk allele frequency, 0.64) and average frequency in dbSNP (risk allele frequency, 0.47). However, the association with UC was also evident considering control allele frequencies given in these databases (P=5×10−5 and < 1×10−8 for Hapmap and dbSNP, respectively). There were no clear-cut indications for a recessive or dominant genetic effect (Table 2). Both the multiplicative (allelic) and recessive models are consistent with the observed association in UC. A haplotype analysis provided some evidence that there are multiple association signals at the MEP1A locus. The risk allele of rs1059276 was present not only in a risk haplotype as expected, but also in a protective haplotype, indicating that a second risk allele in one of the other SNPs might be present independently (Supplementary Table S2 online). The sample size of this study limits the statistical power to confirm independent effects.

Table 2.

Genetic models for rs1059276 in UC

| Modela | OR (95% CI) | P-valueb |

|---|---|---|

| Allelic (A vs. C) | 1.94 (1.51–2.49) | 1.80×10−7 |

| Recessive (AA vs. CC+CA) |

2.46 (1.76–3.45) | 1.34×10−7 |

| Dominant (CC vs. AA+CA) |

0.49 (0.29–0.85) | 9.51×10−3 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Risk allele=A.

Pearson's goodness-of-fit χ2 (degree of freedom)=1.

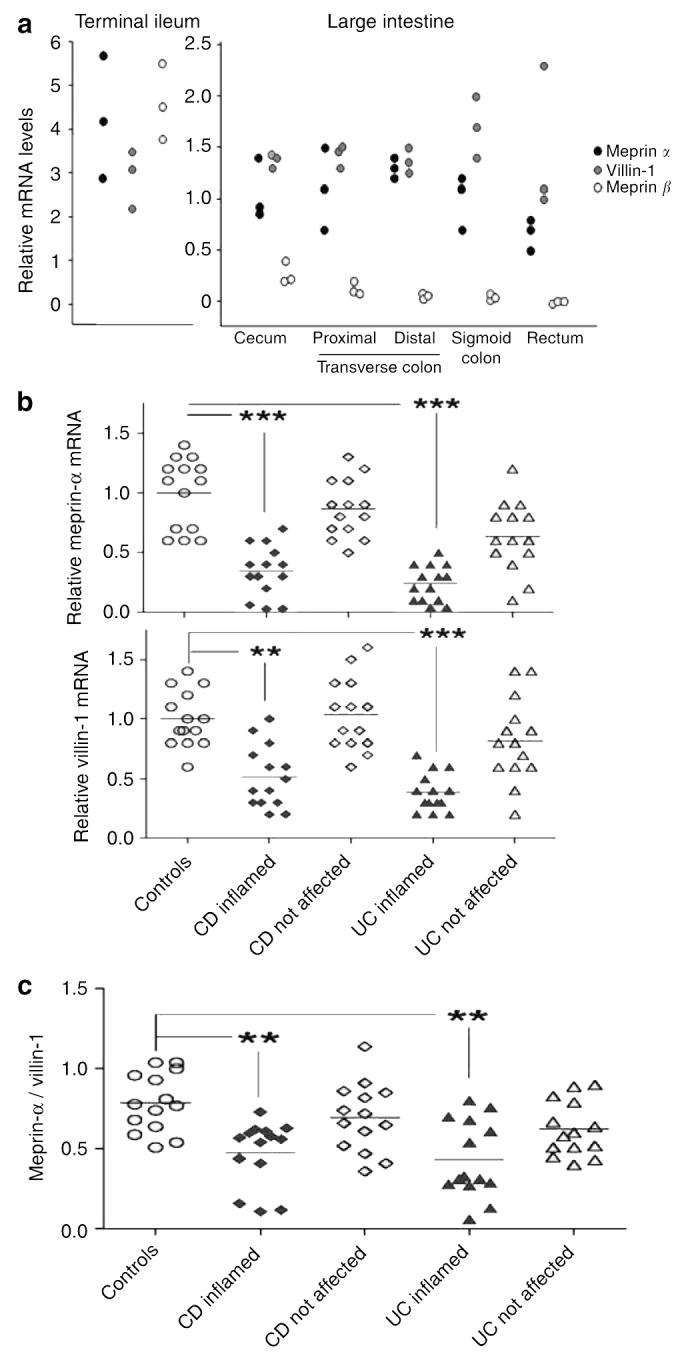

Expression of meprin-α mRNA in the intestine of IBD patients

The mRNA levels for both meprin-α and villin-1 (a marker of differentiated epithelial cells) were measured using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) in endoscopic biopsies from IBD patients and healthy controls. Meprin-α and meprin-α are expressed abundantly in the terminal ileum in healthy patients (Figure 2a, left panel). Meprin-α is also expressed in the entire large intestine (Figure 2a, right panel), albeit at two- to sixfold lower levels than in the ileum. Villin-1 displays a similar expression pattern that probably reflects a decrease in the relative number of differentiated epithelial cells in the colon. In contrast to meprin-α, meprin-β mRNA expression is markedly decreased in proximal parts of the colon and is undetectable in distal parts.

Figure 2.

Expression of meprin-α, meprin-β, and villin-1 in the intestinal mucosa of IBD patients and healthy controls. mRNA levels, as determined by quantitative RT-PCR, are shown relative to the average colonic expression levels of meprin-α in healthy controls. (a) Endoscopic biopsies of three control individuals collected from the terminal ileum, cecum, proximal and distal transverse colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum. (b) Endoscopic biopsies from the sigmoid colon from not affected and inflamed mucosal areas of CD patients, UC patients, and healthy controls (n=14 in each group). Shown are individual values and mean. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, compared with controls (Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn's multiple comparison test). (c) Ratio of meprin-α/villin-1 mRNA levels in mucosa in CD and UC patients as compared with controls. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; CD, Crohn's disease; RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR; UC, ulcerative colitis.

To determine whether meprin subunit expression correlates with inflammation, meprin mRNA levels were compared in affected and unaffected regions of the sigmoid colon of IBD patients and healthy controls. Meprin-α expression was significantly lower in inflamed mucosa of IBD patients compared with the other groups (Figure 2b, top panel). Little-to-no meprin-β mRNA was detectable in either unaffected or inflamed mucosa (data not shown). Expression levels of meprin-α in CD and UC relative to average values for healthy colon were between 0.03 and 0.7 (average, 0.34) and 0.04 and 0.5 (average, 0.24), respectively. A concomitant decrease of villin-1 mRNA indicated a decreased number of differentiated epithelial cells in affected mucosal areas, which could account for some of the decreased meprin-α expression (Figure 2b, bottom panel). If the loss of differentiated epithelial cells was the only cause for the decreased expression of meprin-α mRNA, the meprin-α/villin-1 ratio would be expected to remain unchanged in the inflamed samples. However, a significantly decreased ratio of meprin-α to villin-1 mRNA was found in affected mucosa (Figure 2c). Although the meprin-α to villin-1 mean ratio was 0.79 (range, 0.51–1.04) in healthy controls, it was lower in the affected regions to 0.48 (range, 0.11–0.73) in CD and 0.43 (range, 0.13–0.76) in UC groups, respectively, indicating that the expression of meprin-α was affected to a greater extent than of villin-1. Interestingly, meprin-α mRNA levels in unaffected mucosa of CD patients were similar to those of healthy controls (Figure 2b, top panel). However, in UC patients, we observed a trend of lower meprin-α mRNA levels in unaffected mucosa (mean, 0.64; range, 0.1–1.2). In summary, mucosal inflammation in IBD correlates strongly with low meprin-α mRNA levels in CD and UC.

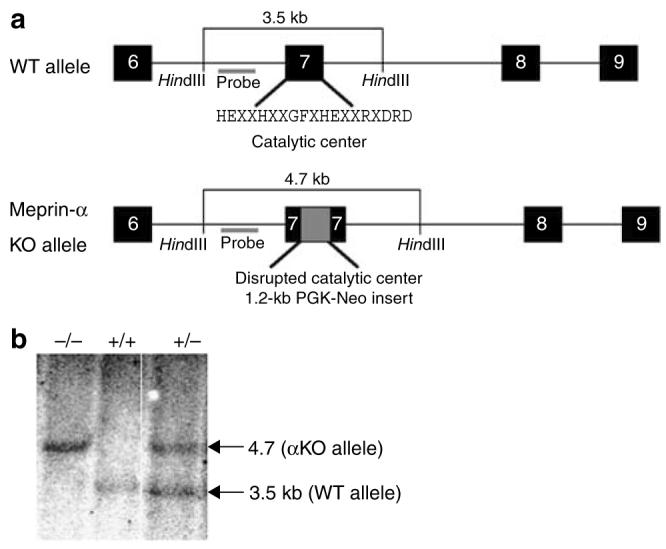

Generation and characterization of meprin αKO mice

To determine whether meprin-α affects the course of IBD in mice, meprin-α knockout mice were generated and an experimental model of IBD was used. Targeted disruption of the Mep1a gene was achieved by inserting a neomycin cassette in exon 7, the segment that codes for the zinc-catalytic center of meprin-α (Figure 3). F1 heterozygote matings gave the expected Mendelian genotype distribution (Supplementary Table S3 online). The homozygous meprin αKO mice did not show any overt physical, anatomical, or histological abnormalities (data not shown). Conventional serum chemistries were determined and all the parameters tested for meprin αKO mice lay within the normal ranges and were similar to those of the WT counterparts (Supplementary Table S4 online). The αKO and WT mice also showed no difference in growth rates, as determined by body weights during different the phases of growth.

Figure 3.

Strategy for Mep1a gene disruption on mouse chromosome 17. (a) Schematic diagram of a portion of the exon–intron structure of the WT and meprin αKO alleles. Exons (6–9) are represented as black boxes. The neomycin cassette derived from the targeting vector (Osdupdel: gift of O. Smithies) is depicted as a gray box in exon 7 of the KO allele. The 19-amino-acid consensus sequence for the catalytic center of astacin family metalloproteases is also shown. (b) Southern blot analysis of tail-derived genomic DNA. The probe used for Southern blotting detects two HindIII-generated fragments: 3.5 kb corresponding to the WT allele and 4.7 kb from the αKO allele. Lanes: −/−, meprin αKO DNA; +/+, WT DNA; +/−, meprin-α heterozygous DNA. WT, wild type.

Matings of meprin αKO mice produced significantly smaller litters than their WT counterparts (P < 0.005). The litter size of meprin αKO mice was 6.2±0.43, compared with 7.8±0.33 pups per litter for WT mice. The smaller litter size of the αKO is reminiscent of the meprin βKO mice that were under-represented in a heterozygous mating.21 Both meprin-α and -β subunits are expressed in WT mice during embryogenesis; the reduced litter sizes in αKO mice indicate the role of meprins in development.22 It is possible that the αKO mice do not have the same reproductive fitness as WT mice, or that there is maternal rescue in the αKO mice generated from the heterozygous parents.

Meprin-α mRNA and protein analysis from several tissues of meprin αKO mice revealed the lack of both, as expected (Supplementary Figure S2 online). End-point PCR of kidney mRNA failed to detect meprin-α message in the αKO mice (Supplementary Figure S2a online) and western blot analysis of urine samples showed detectable levels of the meprin-α protein in the urine of WT, but not αKO, mice (Supplementary Figure S2b online). Immunohistochemical staining of intestinal tissue detected meprin-α protein in the brush-border membranes of ileal villi of WT but not in meprin αKO mice (Supplementary Figure S2c online).

To determine whether the disruption of the Mep1a gene affected meprin-β expression, meprin-β mRNA, protein and activity was assessed in the meprin αKO mice (Supplementary Figure S3 online). PCR analyses indicated similar levels of meprin-β mRNA in the kidney and intestinal tissue in αKO and WT mice (kidney levels shown in Supplementary Figure S3a online). Immunohistochemical analysis indicated the presence of membrane-bound meprin-β subunits in the brush-border membrane of the ileum of both genotypes (Supplementary Figure S3b online). In addition, the activity of meprin-β in the ileum brush-border membranes of WT and meprin αKO mice was similar (Supplementary Figure S3c online). On the basis of these results, it was concluded that meprin-β expression was unchanged in meprin αKO mice.

Meprin αKO mice were more susceptible to DSS-induced colitis

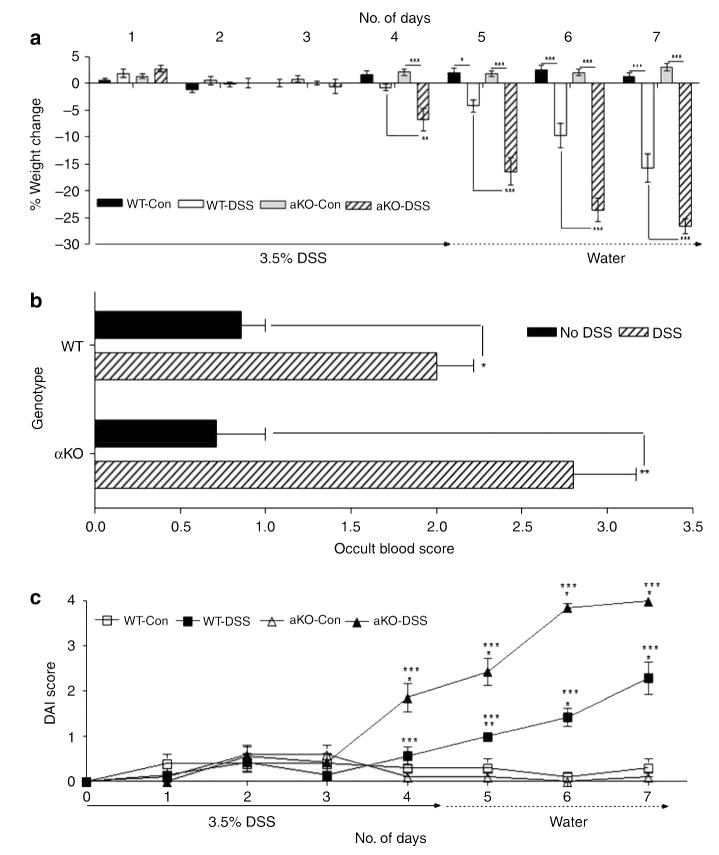

An experimental model of IBD was produced in mice by administering DSS in drinking water. Administration of DSS leads to a UC-like colitis.23 Oral administration of DSS results in toxicity to the epithelial cells of the colon and increased intestinal permeability along with macrophage activation, which results in inflammation as a secondary phenomenon.24-27 Both WT and meprin αKO mice began losing weight on day 4 (Figure 4a). The meprin αKO mice lost a larger percentage of body weight (relative to day 1) than WT mice during days 5–7 (P<0.001). These results indicated that meprin αKO mice developed a more severe colitis than WT mice.

Figure 4.

Meprin αKO mice are more severely affected than WT mice by DSS treatment. (a) Body weight loss in WT and meprin αKO mice was monitored over a 7-day period (n=7 mice per group). The meprin αKO DSS group lost a greater percent of body weight than the WT DSS group over days 4–7 (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001). (b) Occult blood scores for both WT and meprin αKO DSS groups on day 7 showed significantly higher bleeding than their corresponding control groups (n=7 mice per group; *P<0.01; **P<0.001). (c) Disease activity index (DAI) for the 3.5% DSS colitis model. WT and meprin αKO controls maintained DAI scores of 0–0.5 over the 7-day period. The DAI for the meprin αKO DSS group was significantly increased starting on day 4 (*P<0.001; compared with controls), whereas the WT DSS DAI increased day 5 onwards (**P<0.01; *P<0.001; compared with controls). There was a significant difference in the DAIs of the two DSS-treated groups from days 4 to 7 (***P<0.001). DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; WT, wild type.

When fecal matter of DSS-treated and control mice was monitored for occult blood to assess rectal bleeding, the control groups had an occult score less than 1 (WT values, 0.86±0.14; meprin αKO values, 0.71±0.29) (Figure 4b). There was an increase in fecal occult blood at 7 days in mice treated with DSS, with meprin αKO mice (mean values, 2.8±0.37) bleeding more than the WT mice (mean values, 2.0±0.22).

Disease activity index (DAI) values were calculated as described in the Methods section considering weight loss, stool formation, and rectal bleeding. These scores reflect the degree of inflammation and injury in mice. The DAI values were greater for the meprin αKO mice than for WT mice from days 4 to 7 (Figure 4c). Although the DAI score for the DSS-treated meprin αKO mice (1.86±0.3) was significantly higher than that for controls (0.1±0.1) at day 4 (P<0.001), the DAI of DSS-treated WT mice started increasing only at day 5 (control, 0.3±0.2; DSS, 1.0±0) (P<0.01). At day 5, the DAI for the DSS-treated meprin αKO mice (2.43±0.3) was more than double the score for the WT group (P<0.001). By day 7, the DAI for the meprin αKO group reached a value of 4.0±0.01, accompanied by extensive weight loss, diarrhea, and profuse bleeding, whereas the WT group value was 2.29±0.36.

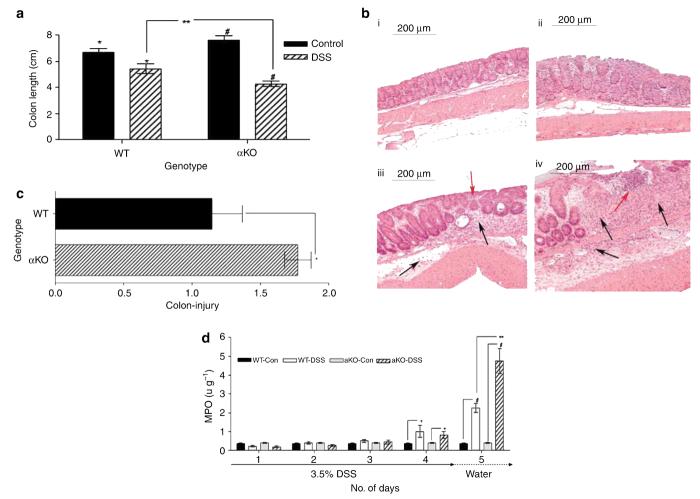

Meprin αKO mice showed greater colon damage and inflammation

To assess the damage caused by DSS-induced colitis, colon lengths were measured and tissues examined histologically (Figure 5). Colons from the DSS-treated groups showed prominent shortening at necropsy on day 7 compared with those from the control groups (WT, P<0.02; meprin αKO, P<0.0001) (Figure 5a). The decrease in colon length was more marked for meprin αKO mice than for WT mice, indicating greater damage (P<0.04).

Figure 5.

Greater colon injury and inflammation in meprin αKO compared with WT mice. (a) Colon shortening at day 7 for the mice treated with DSS. The average colon length for both WT and meprin αKO mice administered 3.5% DSS was shorter than that for their respective controls at day 7 (*P<0.02; #P<0.0001). The meprin αKO DSS group had shorter colons than WT DSS group (n=7 mice per group; **P<0.04). (b) Proximal colons from WT and meprin αKO mice were scored for injury. Representative histological sections from (i) WT control, (ii) meprin αKO control, (iii) WT DSS-treated, and (iv) meprin αKO DSS-treated colons are shown. Colon sections from both the control groups have normal appearance (i and ii). DSS-treated colon of WT mouse (iii) had crypt destruction (red arrow) along with leukocytic infiltration in the lamina propria as well as in the submucosa (black arrows). Greater damage is evident in the DSS-treated αKO section (iv) in which massive crypt destruction is seen in an area of ulceration (red arrow). Heavy leukocyte infiltration is evident in the lamina propria and submucosal regions (black arrows). (c) The injury scores of WT and meprin αKO DSS-treated groups were normalized to the corresponding control populations. Colons from meprin αKO mice show significantly greater damage than those from WT mice (n=7 mice per group; *P<0.04). (d) MPO activities of WT and meprin αKO colons from DSS-treated and -untreated animals were measured from days 1 to 5. The DSS-treated mice had increased MPO activity relative to their controls (n=6; *P<0.00002; #P<0.00005) and the colon MPO activity of DSS-treated meprin αKO mice was significantly greater than that of the DSS-treated WT mice on days 4 and 5 (**P<0.007). DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; MPO, myeloperoxidase; WT, wild type.

Sections of proximal colon of all the groups were examined histologically after hematoxylin–eosin staining (Figure 5b, panels i–iv). Both the WT (i) and meprin αKO (ii) controls showed normal colon morphology. DSS treatment caused marked changes in colon structure in both the genotypes with respect to their control groups. In addition, obvious differences between the two genotypes were observed. The DSS-treated WT mice showed some crypt destruction and infiltrating leukocytes (iii). Greater damage in the DSS-treated meprin αKO mice was observed, as evidenced by massive crypt destruction and ulceration. Heavy leukocytic infiltration was seen both in the lamina propria and submucosal regions (iv).

The colon sections were scored for injury using a multifactorial scoring system.28 The DSS-treated mice had a greater injury score than the controls of both the genotypes, with αKO having a higher score (WT, 14.5±2.3; αKO, 21.1±1.1) (P<0.01). The injury scores of the DSS-treated groups were normalized to their corresponding control populations to assess the degree of colon injury brought about by DSS treatment (Figure 5c). Although the WT sections showed 1.14-fold injury (control, 12.6±1.8; DSS, 14.5±2.3), the fold increase for meprin αKO (control 11.9±1.3; DSS, 21.1±1.1) sections was 1.77. This difference between the two groups was significant (P<0.04).

To assess the accumulation of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes, inflammation of colonic mucosa was evaluated by myeloperoxidase (MPO) assay (Figure 5d). The colons of WT and meprin αKO mice in control groups had negligible MPO activity. After DSS treatment, increased MPO activity was observed in both WT and meprin αKO mouse colons (P<2×10−5 and P<5×10−5, respectively). The meprin αKO mice had a significantly greater MPO activity than their WT counterparts (P<0.007). This indicated a more severe inflammatory reaction in the meprin αKO mice.

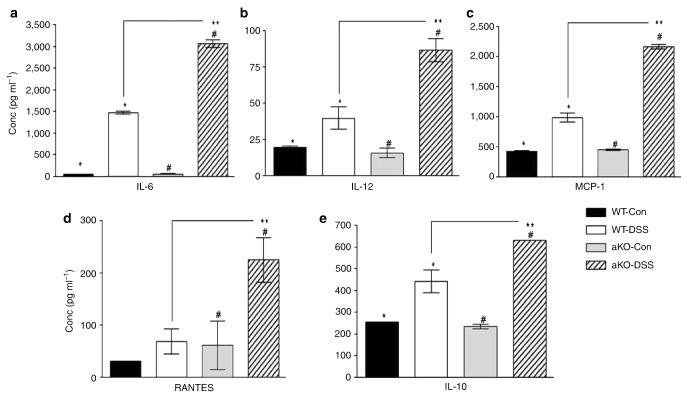

Colon cytokines of meprin αKO mice show greater elevation

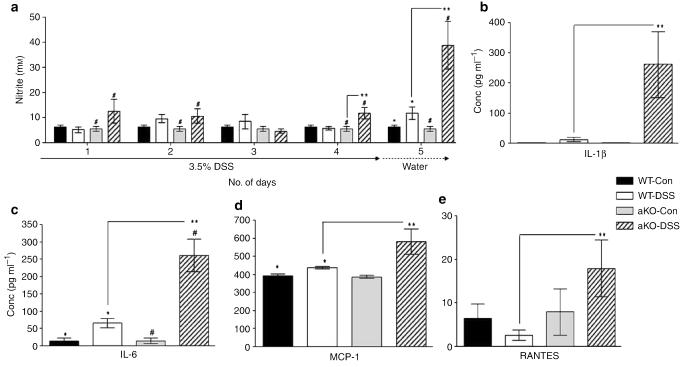

To elucidate further the differences between the WT and αKO mice, as well as understand the inflammatory environment upon IBD induction, colon cytokines were measured on day 5 using an array that quantifies the levels of a panel of 16 cytokines and chemokines (Supplementary Table S5 online). The cytokines were significantly higher in the DSS-treated WT and αKO mice compared with their corresponding controls. DSS-treated WT and αKO mice showed a greater than fivefold elevation of interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels, compared with their untreated controls. Furthermore, IL-12 and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α showed more than fivefold elevation only in the αKO mice. Seven cytokines—IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) (CCL2), RANTES (CCL5), and IFN-γ—were significantly elevated in the αKO mice compared with their WT counterparts (P<0.05). Levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-9, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, MIP-1α (CCL3), and tumor necrosis factor-α were not significantly different between WT and αKO DSS-treated groups (Supplementary Table S5 online). IL-6 had the highest fold increase in both the genotypes; in WT mice, it was 28-fold higher after DSS treatment, whereas in the αKO, the fold increase was 50-fold (Figure 6a). The other pro-inflammatory molecules, namely IL-12, MCP-1, and RANTES, showed a two- to threefold increase in WT mice but a four- to fivefold increase in αKO mice (Figure 6b–d). Both the genotypes had significantly elevated levels (two- to threefold) of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, in the DSS-treated colons (Figure 6e). Overall, the cytokine data show that meprin αKO mice mount a more robust immune response than WT mice in this model of experimental colitis.

Figure 6.

Colon cytokine and chemokine levels of WT and αKO mice treated with or without DSS were measured on day 5 (n=5 per group). Both the DSS-treated groups had significant elevations in their cytokine levels compared with their corresponding controls (WT DSS treated vs. control, *P<0.03; αKO DSS treated vs. control, #P<0.05). (a) IL-6 levels were greatly elevated upon DSS treatment, in both WT and αKO mice, to significantly higher levels in the latter (**P<0.0001). (b–d) There were significant increases in the levels of IL-12 (**P<0.01), MCP-1 (**P<0.00007), and RANTES (**P<0.02), in the DSS-treated αKO colons compared with those of the DSS-treated WT group. (e) IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, was also elevated in both genotypes after DSS treatment; meprin αKO colons had significantly higher levels of IL-10 (**P<0.03). DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; WT, wild type.

Meprin αKO mice show higher systemic inflammation in response to DSS treatment

As colitis induction elicited a greater inflammatory response in the αKO mice, the degree of systemic inflammation was investigated by measuring the serum nitric oxide (NO2/NO3) levels (Figure 7a). The total nitric oxide levels in control mice of both the genotypes were low (5–7 μm). The levels in WT DSS-treated mice did not show any significant elevation until day 5, and the increase was modest (10–15 μm). By contrast, the nitric oxide levels in the DSS-treated meprin αKO group was increased as early as day 1 (P<0.05), and by day 5, the values were elevated over fivefold (∼40 μm), indicating systemic inflammation in this genotype.

Figure 7.

Meprin αKO mice have greater systemic inflammation than WT mice. (a) Serum nitric oxide levels of all the four groups were measured throughout the course of the study from days 1 to 5. Compared with its control group, DSS-treated meprin αKO mice showed significantly higher levels as early as day 1(#P<0.05), whereas in the WT DSS-treated mouse, values were not elevated until day 5 (*P<0.05). The nitrite levels in meprin αKO mice were significantly higher than the WT DSS-treated group on days 4 and 5 (n=6; **P<0.02). (b–e) The DSS-treated groups had increased levels of serum cytokines compared with their respective water controls (n=7–15 mice per group; WT DSS treated vs. control, *P<0.03; αKO DSS treated vs. control, #P<0.05). IL-1β and IL-6 levels were markedly elevated in αKO compared with WT serum after DSS treatment (**P<0.04 and P<0.001, respectively). DSS-treated αKO mice also had significantly higher levels of MCP-1 (**P<0.05) and RANTES (**P<0.05) than the DSS-treated WT group. DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; IL, interleukin; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; WT, wild type.

The same panel of 16 cytokines and chemokines, measured in the colon, was measured in the sera of these mice to define the inflammatory environment further. In contrast to the colon cytokines, significant differences between the two genotypes were limited to four cytokines: IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, and RANTES. IL-1β levels in the DSS-treated WT mice were ninefold higher than in controls, whereas in the αKO mice, the elevation was over 200-fold (Figure 7b). Serum IL-6 levels in the WT mice were approximately fourfold increased after DSS treatment compared with controls, whereas in the αKO mice, levels increased over 16-fold (Figure 7c). Modest increases in MCP-1 and RANTES levels were also observed in the αKO DSS-treated group (Figure 7d and e).

DISCUSSION

The positive association of the five exonic SNPs at the MEP1A locus with UC reported in this study implicates this metalloprotease gene as a genetic determinant in this disease. Of these five SNPs, only rs1059276 was statistically significant in CD in our study, and the P-value for the SNP was much lower in CD (3×10−3) than in UC (2×10−7). An “in silico” replication was performed with the publicly available data from the recent CD meta-analysis, incorporating the data of three previous genome-wide studies.29 Although the SNPs presented here were not specifically analyzed in these studies, “imputed” P-values for the SNPs were not significant.30 Therefore, we conclude that although there is a strong association of meprin-α SNPs with UC, evidence for such associations with CD remains unclear.

The two earlier genome-wide studies for UC by Fisher et al.31 and Franke et al.32 did not report SNPs at or nearby the MEP1A locus. Notably, Fisher et al.31 analyzed only a subset of non-synonymous SNPs. The UC-associated SNPs are all synonymous, which points to expression levels being affected rather than enzyme function. We cannot exclude the possibility that the MEP1A locus contains causal intronic SNPs linked to the significantly associated exonic SNPs identified in this study. The most significant genetic association between MEP1A SNPs and UC was the 3′-UTR C2417A SNP (dbSNP ID rs1059276). Important functions mediated by the 3′-UTR are mRNA stability and translation regulation.33 It is, therefore, possible that the 3′-UTR polymorphism affects constitutive meprin-α expression levels and/or the regulation of meprin-α expression in inflamed mucosa. Consistent with this idea is the evidence provided by the expression studies in human IBD patients in this study as well as by a microarray study reported earlier in UC patients34 showing that there are decreased levels of meprin-α mRNA associated with mucosal inflammation in the intestine. Our studies show that mice lacking meprin-α protein develop a heightened inflammatory response and greater intestinal injury than WT mice when challenged with DSS. Therefore, the genetic and expression studies in humans and mice are consistent with a lack of meprin-α protein being associated with greater inflammation.

Earlier studies using inbred strains of mice that have low expression of meprin-α (e.g., as in C3H/HeJ) showed that these mice were more vulnerable to DSS-induced IBD than mice with high levels of expression (e.g., C57BL/6J mice).35,36 These C-strain mice contain several differences in their major histocompatibility genes on chromosome 17 (the area of the genome that Mep1a is linked to), and thus several genes in these mice could influence vulnerability to intestinal damage by DSS. The study presented herein is the first to report that the disruption of the meprin-α gene alone affects the severity of IBD.

The colon and serum cytokine profiles exhibited by the WT and αKO mice show that meprins modulate the immune environment in a manner consistent with human IBD. Notably, two pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and IL-12, are markedly higher in the αKO colon compared with WT, and there is evidence that these cytokines play crucial roles in human IBD.37,38 A recent study has shown that proIL-18 is activated by meprin B in vitro and that IL-18 is significantly elevated in the serum of DSS-treated αKO mice compared with that in the WT mice.39 Thus, the elevated IL-18 levels in the αKO mice also correlate with one of the hallmarks of human colitis. Two other cytokines that are characteristically elevated in human colitis, IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α, however, are not significantly different in the WT and αKO; thus, there is not a perfect match between the meprin αKO mouse and the human IBD phenotype. The increased colon levels of MCP-1 in the αKO mice are consistent with a positive correlation for MCP-1 increase in both the epithelium and inflammatory cells of IBD patients.40 MIP-1α, a chemokine that boosts the Th1 response, is significantly elevated in the DSS-treated αKO colon but not in the WT colon; MIP-1α exacerbates IBD in mice, and may lead to the early development of IBD in the αKO.41 In addition, there is clear evidence for greater systemic inflammation in the αKO mice compared with WT mice as indicated by serum NO, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels. This implies a loss of the capability of the mucosa of αKO mice to keep the disease localized and that meprin-α is a protective factor in the intestine.

The enhanced cytokine levels of the αKO mice could result by several mechanisms, including direct interactions of meprin isoforms with specific cytokines. For example, meprin A (consisting of homomeric α-subunits or heteromeric α/β-subunits) is capable of cleaving and inactivating several chemokines, such as MCP-1, RANTES, and MIP-1, and therefore a lack of meprin A isoforms may result in an increased accumulation of these pro-inflammatory molecules.22 By contrast, meprin B (consisting of meprin-β dimers) is capable of activating pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β42 and IL-18.39 Thus, the balance between the meprin isoforms that is altered in the αKO mouse may well affect the activation and degradation of cytokines resulting in the altered inflammatory response observed in experimental IBD.

The balance between specific MMPs and their inhibitors has also been implicated in the pathology of intestinal inflammatory conditions.43,44 For example, MMP-2 and MMP-9 are upregulated in human and mouse models of IBD, whereas MMP-9 enhances inflammation and tissue damage, and MMP-2 is protective and is involved in healing and tissue resolution.45 Meprins can also degrade extracellular matrix proteins, such as collagen IV, fibronectin, and nidogen,13 and these activities might be important in the remodeling of injured tissue in inflammatory conditions as seen in the recovering segments of the intestine. The studies reported herein indicate a role for meprin A in tissue regeneration/healing as opposed to tissue damage, as well as protection against inflammatory responses.

In summary, several lines of evidence, from human genetic studies and the meprin αKO mouse model presented here, associate MEP1A with IBD. MEP1A variants are associated with UC, pointing to this protease as a novel susceptibility factor. The decrease of meprin-α mRNA in the intestinal mucosa is associated with inflammation in human CD and UC patients and in the mouse DSS-induced experimental model of IBD.

METHODS

MEP1A genotyping and genetic association study in IBD

A total of 380 CD and 379 UC patients (Supplementary Table S6 online) were recruited from the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK. CD and UC were diagnosed according to the standard criteria. The healthy controls were age and sex matched and included 276 subjects randomly chosen from general practitioner clinics around Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK, and 96 samples from the UK National Blood Transfusion Service. All subjects were white, non-Jewish UK Caucasians. The study had 90% power to detect association at a P-value <0.05, given an allele frequency of no less than 10% and a relative risk of 2. Ethics approval was obtained from the Central Oxford Region Ethics Committee (COREC 00.083) and written consent was obtained from all participants.

dbSNP (build 129) states a total of 255 SNPs at the MEP1A locus, the large majority of which are intronic. There are 10 SNPs in the coding region and 6 in the 3′-UTR region. Eighty-four SNPs have been genotyped in Hapmap. Owing to the presence of highly similar pseudogene regions (>90% in exons 11–14) on chromosome 9, there was the risk that the genotypes in databases were not 100% correct. Therefore, MEP1A was screened for common SNPs by sequencing 24 samples (6 UC, 6 CD, and 12 celiac disease), thus avoiding this potential source for errors. Only exons were analyzed, which were considered most likely to be functional. Seven of the nine identified exonic SNPs have been genotyped in Hapmap (Table 1a).

MEP1A exons were amplified from genomic DNA and genotyped with an ABI automated sequencer and analyzed using Lasergene (DNASTAR) (see Supplementary Table S7 online for primers). Fulfilling the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was an inclusion criterion for statistical analysis with SPSS (SPSS), the Epi Info (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, http://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/), and Open Epi online epidemiologic calculators (version 2, www.openepi.com). χ2 test was used on allele frequencies data in 2×2 contingency tables. The extended Mantel–Haenszel χ2 test for linear trend (one degree of freedom, with continuity correction) was performed on genotype–phenotype associations of MEP1A polymorphisms. Linkage disequilibrium between genotyped polymorphisms was determined using GOLD.30

Quantitative RT-PCR in human intestinal specimens

The human biopsies originated from the IBD biobank of the Clinic for Gastroenterology, Inselspital Bern, Switzerland. The study was approved by the local ethics committee, the “Kantonale Ethikkommission Bern,” and written informed consent was obtained from all the patients. The following were included in the study: 14 samples each of healthy mucosa from control individuals, and inflamed and not-affected mucosa samples from CD patients and UC patients (Supplementary Table S8 online). Anti-inflammatory medication of patients included salazopyrin and corticoids.

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and reverse transcribed using the Reverse Transcription System Kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA samples of insufficient quality, as determined using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), were excluded from the study. cDNA (20 ng) was added to a reaction volume of 20 μl 1× TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix containing uracil N-glycosylase (UNG; AmpErase, Foster City, CA) and dUTP (Applied Biosystems, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Target genes were quantified in duplicate on an Applied Biosystems 7500 PCR System using Taqman probes from Applied Biosystems: Mep1A, Mep1B, Vill-1, and TBP (assay IDs Hs01574670_m1, Hs00195535_m1, Hs01031722_g1, and Hs00427620_m1, respectively). Sample dilution series confirmed that the RT-PCR measurements for these genes were quantitative. Technical duplication variation was <10%. TATA-binding protein (TBP) was used as a housekeeping gene. Differences between mean expression levels in the patient groups were analyzed statistically using Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn's multiple comparison tests.

Generation of meprin α−/− mice

The Mep1a gene on chromosome 17 was inactivated by homologous recombination with a targeted vector that inserted a neomycin-resistant cassette into the catalytic center, encoded by exon 7 of the Mep1a gene, thereby deleting 140 bp at the targeted site. Primers 5′-CAGGTGAGTATGACTCGAGCAGAGTAGG-3′ (containing an XhoI restriction site, corresponding to exon7/intron7 junction) and 5′-GATGAGGCAGCTAGCATACTGGGATTC-3′ (encoding an NheI site and corresponding to intron 8) were used to generate a 4.9-kb amplicon from the 129×1/SvJ genomic DNA (Jackson stock no. 000691). The XhoI–NheI-digested amplicon was ligated into XhoI–NheI cut Osdupdel (a kind gift from Professor Oliver Smithies, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) to generate Osdupdel-Mep1a-4.9. A second amplicon was made using primers 5′-GTCAGAAGAAATCTAGACAGTAGATCAGTG-3′ (containing an XbaI restriction site and corresponding to intron 6) and 5′-CCCACCTGTGGATCCCCAATCATAGAC-3′ (encoding a BamHI restriction site and corresponding to exon 7). This 2.5-kb fragment was XbaI–BamHI digested and ligated into XbaI–BamHI cut Osdupdel-Mep1a-4.9. The final vector, Osdupdel-Mep1a, had exon 7 disrupted by a 1.2-kb neomycin cassette with an in-frame stop codon (Figure 3a).

The targeting vector, Osdupdel-Mep1a, was electroporated into R1 mouse embryonic stem cells.46 A total of 390 clones were screened by PCR. PCR product from the WT allele corresponded to 3.1 kb and that of the targeted allele corresponded to 4.3 kb. The positive clones were microinjected into blastocysts of C57BL/6 and four germline chimeras were obtained. Electroporation and selection of targeted embryonic stem cells and subsequent blastocyst injections were performed at the University of Michigan Transgenic Animal Facility. Chimeric animals were crossed with C57BL/6 mice at Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine in full compliance with animal use and care regulations. Genotypes were determined by tail biopsies using PCR as well as Southern analysis. For Southern analysis, HindIII was used to digest 10 μg of DNA. A 740-bp probe, corresponding to intron 8, was generated to detect WT (4.7 kb) and disrupted (3.5 kb) alleles (Figure 3b) (see Supplementary Table S9 online for primers).

End-point PCR

Total RNA isolated from mouse kidney using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was subjected to RT-PCR with the Superscript One-Step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen). The amount of amplicon was obtained with the Stratagene Eagle-Eye II system equipped with Eagle-Sight software. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was amplified as a control. Meprin-α primers gave a 164-bp and meprin-β primers gave a 145-bp product (see Supplementary Table S9 online for primers).

Immunoblotting of urinary samples and immunohistochemistry

The presence of meprin-α protein was determined by western analysis of urine from WT and meprin αKO mice as described earlier.21

For immunohistochemistry, tissues were fixed in methyl Carnoy's solution (60% methanol, 30% chloroform, and 10% acetic acid), dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in paraffin wax, and thin sectioned (5 μm). Sections were probed using anti-meprin-α or -β antibody.21 Digital photographs were taken with a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope.

Ileum brush-border membrane preparation

Ileal samples were weighed and homogenized in 10 volumes of cold homogenization buffer (50 mm mannitol, 2 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.0) in the presence of Complete Mini Protease Cocktail Inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). CaCl2 was added to a final concentration of 10 mm and the homogenate stirred slowly at 4°C for 15 min. After centrifugation at 3,000 g for 15 min, the sediment was discarded. The supernatant fraction was centrifuged at 27,000 g for 30 min and the sediment was suspended in 0.5 volumes of homogenization buffer. After a final centrifugation at 27,000 g for 30 min, the sediment was suspended in 0.5 volumes of homogenization buffer. Meprin-β activity was assayed as described earlier.47

Induction of experimental colitis by DSS

WT and meprin αKO litter-mates on C57BL/6×129/Sv background were used for DSS experiments. All mice were age matched (8–9 weeks of age) and sex matched (males) and housed under conventional nonspecific pathogen-free conditions. DSS (mol. wt, 44,000; TDB Consultancy, Uppsala, Sweden) was administered in drinking water at 3.5 % wt/vol concentration for 4 days, followed by water alone for 3 days. The controls were given water only. The mice were scored daily for body weight, stool formation, and rectal bleeding. The DAI was calculated giving equal weight to all the three parameters on a scale of 0–4; with 0 indicating no disease and 4 corresponding to maximal disease activity.24 Briefly, mice that lost ∼5% of their body weight were given a score of 1, if their stool formation was normal and they showed no hemoccult bleeding. The scores of 2 and 3 were assigned based on the magnitude of weight loss accompanied with loose stool and rectal bleeding. The mice receiving the highest score of 4 had lost more than 20% of their body weight and showed gross rectal bleeding and diarrhea. Animals were necropsied on day 7 and the entire colon was removed using standard surgical procedures and measured before being dissected for sample preparation. Immediately before necropsy, stool was tested for blood using hemoccult blood slides (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). For colon MPO and serum nitrite studies, mice were killed on day 5. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture.

Histology

A histological examination was performed on samples of proximal colon from each animal. The sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin and evaluated for tissue damage by an investigator blinded to the treatment groups using the validated scoring system of Williams et al.28

MPO assay and serum nitric oxide levels

Colon samples were weighed and assayed for MPO activity as described.48 One unit of enzyme activity is defined as the amount of MPO that degrades 1 mmol of H2O2 per min at room temperature.

Blood was collected in EDTA-coated microvettes (Sarstedt, Newton, NC) and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min. The serum was removed and filtered using a 10,000 MW cutoff microcon (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The ultrafiltrate was measured for total NO2/NO3 (μm) following the manufacturer's instructions using the standard Greiss assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI).

Measurement of colon and serum cytokines

Colon and serum cytokines in control and DSS-treated mice were measured using mouse Inflammation Cytokine Array (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Colons were homogenized in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (0.1 g ml−1). The plate was developed using Biochemi EC3 imaging system (UVP, Upland, CA). Intensity of the spots was analyzed using the software provided (Quansys Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

For analysis of genotype distributions of the F2 population, a χ2 analysis was performed on data obtained from F1 heterozygous crosses. For all other analyses, the unpaired, two-tailed t-test was used. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Christine Valeski and Ge Jin, Penn State College of Medicine, for excellent technical assistance; Ken I. Welsh, Imperial College, London, Jeffrey Barrett, Wellcome Trust Center for Human Genetics, Oxford, and Martin Kohli, Max-Planck Institute of Psychiatry, Munich, for their advice in the analysis of the genetic association data, and Beatrice Flogerzi and Stefan Müller, Gastroenterology Department, University of Bern, for their help in acquiring and processing the biopsies of IBD patients. The meprin αKO vector was introduced into mouse ES cells by Thomas L. Saunders, University of Michigan Medical School Transgenic Facility. The Penn State College of Medicine Molecular Genetics Core Facility is acknowledged for help with DNA sequencing. This study was supported by NIH DK19691 (J.S.B.), the Falk Foundation (D.L.), the Foundation Johanna Dürmüller-Bol (D.L.), the Swiss National Science Foundation no. 3100A0.100772 (E.E.S.), and 3200BO-107527 (F.S.), and the Carlino Gift Fund from the Penn State College of Medicine (G.L.M.). S. Banerjee, G.L. Matters, L.R. Fitzpatrick, and J.S. Bond generated and characterized the meprin αKO mice and performed the studies for the experimental model of IBD; B. Oneda, F. Seibold, E.E. Sterchi, and D. Lottaz contributed to the analysis of the biopsies of IBD patients; L.M. Yap, D.A. Jewell, T. Ahmad, and D. Lottaz conducted the case–control association study for meprin-α in IBD.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/mi

DISCLOSURE The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogura Y, et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:603–606. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duerr RH, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006;314:1461–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.1135245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hampe J, et al. Linkage of inflammatory bowel disease to human chromosome 6p. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;65:1647–1655. doi: 10.1086/302677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang W, et al. Fine mapping of MEP1A, the gene encoding the alpha subunit of the metalloendopeptidase meprin, to human chromosome 6P21. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;216:630–635. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bankus JM, Bond JS. Expression and distribution of meprin protease subunits in mouse intestine. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;331:87–94. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lottaz D, Hahn D, Muller S, Muller C, Sterchi EE. Secretion of human meprin from intestinal epithelial cells depends on differential expression of the alpha and beta subunits. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;259:496–504. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lottaz D, Maurer CA, Hahn D, Buchler MW, Sterchi EE. Nonpolarized secretion of human meprin alpha in colorectal cancer generates an increased proteolytic potential in the stroma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1127–1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lottaz D, et al. Compartmentalised expression of meprin in small intestinal mucosa: enhanced expression in lamina propria in coeliac disease. Biol. Chem. 2007;388:337–341. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crisman JM, Zhang B, Norman LP, Bond JS. Deletion of the mouse meprin beta metalloprotease gene diminishes the ability of leukocytes to disseminate through extracellular matrix. J. Immunol. 2004;172:4510–4519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stocker W, et al. The metzincins—topological and sequential relations between the astacins, adamalysins, serralysins, and matrixins (collagenases) define a superfamily of zinc-peptidases. Protein Sci. 1995;4:823–840. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bond JS, Matters GL, Banerjee S, Dusheck RE. Meprin metalloprotease expression and regulation in kidney, intestine, urinary tract infections and cancer. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3317–3322. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruse MN, et al. Human meprin alpha and beta homo-oligomers: cleavage of basement membrane proteins and sensitivity to metalloprotease inhibitors. Biochem. J. 2004;378:383–389. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirano M, et al. Mannan-binding protein blocks the activation of metalloproteases meprin alpha and beta. J. Immunol. 2005;175:3177–3185. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bond JS, Rojas K, Overhauser J, Zoghbi HY, Jiang W. The structural genes, MEP1A and MEP1B, for the alpha and beta subunits of the metalloendopeptidase meprin map to human chromosomes 6p and 18q, respectively. Genomics. 1995;25:300–303. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang W, Beatty BG. Assignment of Mep 1a to mouse chromosome band 17C1-D1 by in situ hybridization. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1997;76:206–207. doi: 10.1159/000134550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorbea CM, et al. Cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of the mouse meprin beta subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:21035–21043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn D, Illisson R, Metspalu A, Sterchi EE. Human N-benzoyl-L-tyrosyl-p-aminobenzoic acid hydrolase (human meprin): genomic structure of the alpha and beta subunits. Biochem. J. 2000;346(Part 1):83–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertenshaw GP, et al. Marked differences between metalloproteases meprin A and B in substrate and peptide bond specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:13248–13255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011414200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang W, Beatty BG. Identification and localization of MEP1A-like sequences (MEP1AL1-4) in the human genome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;261:163–168. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norman LP, Jiang W, Han X, Saunders TL, Bond JS. Targeted disruption of the meprin beta gene in mice leads to underrepresentation of knockout mice and changes in renal gene expression profiles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:1221–1230. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1221-1230.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norman LP, Matters GL, Crisman JM, Bond JS. Expression of meprins in health and disease. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2003;54:145–166. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(03)54008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boismenu R, Chen Y. Insights from mouse models of colitis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000;67:267–278. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper HS, Murthy SN, Shah RS, Sedergran DJ. Clinicopathologic study of dextran sulfate sodium experimental murine colitis. Lab. Invest. 1993;69:238–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dieleman LA, et al. Dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis occurs in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1643–1652. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90803-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egger B, et al. Characterisation of acute murine dextran sodium sulphate colitis: cytokine profile and dose dependency. Digestion. 2000;62:240–248. doi: 10.1159/000007822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ni J, Chen SF, Hollander D. Effects of dextran sulphate sodium on intestinal epithelial cells and intestinal lymphocytes. Gut. 1996;39:234–241. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams KL, et al. Enhanced survival and mucosal repair after dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in transgenic mice that overexpress growth hormone. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:925–937. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrett JC, et al. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn's disease. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:955–962. doi: 10.1038/NG.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frazer KA, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher SA, et al. Genetic determinants of ulcerative colitis include the ECM1 locus and five loci implicated in Crohn's disease. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:710–712. doi: 10.1038/ng.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franke A, et al. Sequence variants in IL10, ARPC2 and multiple other loci contribute to ulcerative colitis susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1319–1323. doi: 10.1038/ng.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss IM, Liebhaber SA. Erythroid cell-specific determinants of alpha-globin mRNA stability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:8123–8132. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawrance IC, Fiocchi C, Chakravarti S. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: distinctive gene expression profiles and novel susceptibility candidate genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:445–456. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahler M, et al. Differential susceptibility of inbred mouse strains to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:G544–G551. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.3.G544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beynon RJ, Bond JS. Deficiency of a kidney metalloproteinase activity in inbred mouse strains. Science. 1983;219:1351–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.6338590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atreya R, Neurath MF. Involvement of IL-6 in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2005;28:187–196. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:28:3:187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pang YH, Zheng CQ, Yang XZ, Zhang WJ. Increased expression and activation of IL-12-induced Stat4 signaling in the mucosa of ulcerative colitis patients. Cell. Immunol. 2007;248:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banerjee S, Bond JS. Prointerleukin-18 is activated by meprin beta in vitro and in vivo in intestinal inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:31371–31377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802814200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banks C, Bateman A, Payne R, Johnson P, Sheron N. Chemokine expression in IBD. Mucosal chemokine expression is unselectively increased in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. J. Pathol. 2003;199:28–35. doi: 10.1002/path.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pender SL, et al. Systemic administration of the chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha exacerbates inflammatory bowel disease in a mouse model. Gut. 2005;54:1114–1120. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.052779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herzog C, Kaushal GP, Haun RS. Generation of biologically active interleukin-1beta by meprin B. Cytokine. 2005;31:394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Lampe B, Barthel B, Coupland SE, Riecken EO, Rosewicz S. Differential expression of matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors in colon mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2000;47:63–73. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kobayashi K, et al. Therapeutic implications of the specific inhibition of causative matrix metalloproteinases in experimental colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium. J. Pathol. 2006;209:376–383. doi: 10.1002/path.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garg P, et al. Selective ablation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 exacerbates experimental colitis: contrasting role of gelatinases in the pathogenesis of colitis. J. Immunol. 2006;177:4103–4112. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, Abramow-Newerly W, Roder JC. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:8424–8428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bertenshaw GP, Villa JP, Hengst JA, Bond JS. Probing the active sites and mechanisms of rat metalloproteases meprin A and B. Biol. Chem. 2002;383:1175–1183. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Medina C, et al. Increased activity and expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in a rat model of distal colitis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G116–G122. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00036.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.