SUMMARY

Telomeres play critical roles in protecting genome stability, and their dysfunction contributes to cancer and age-related degenerative diseases. The precise architecture of telomeres, including their single-stranded 3′ overhangs, bound proteins, and ability to form unusual secondary structures such as t-loops, is central to their function and thus requires careful processing by diverse factors. Furthermore, telomeres provide unique challenges to the DNA replication and recombination machinery, and are particularly suited for extension by the telomerase reverse transcriptase. Helicases use the energy from NTP hydrolysis to track along DNA and disrupt base pairing. Here we review current findings concerning how helicases modulate several aspects of telomere form and function.

Keywords: telomere, helicase, senescence, replication, recombination, G-quadruplex

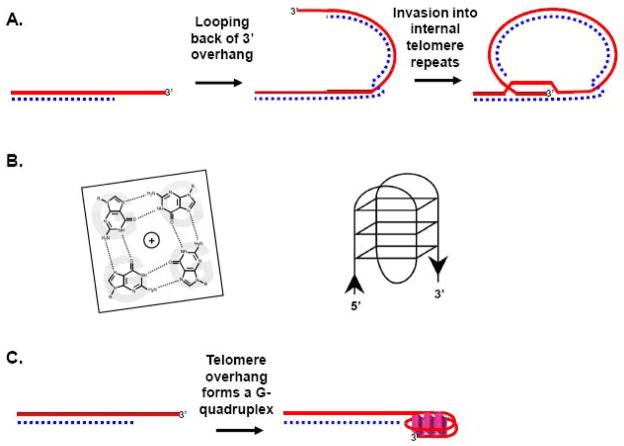

1. TELOMERE BIOLOGY

Telomeres are the repeated DNA sequences and associated proteins that lie at the termini of linear chromosomes [1–3]. In most eukaryotes, including all vertebrates, the telomere strand that extends in a 5′-to-3′ direction toward the terminus is G-rich and ends with a single-strand overhang. For example, vertebrate telomeres comprise several kb of repeats of the sequence TTAGGG, and S. cerevisiae telomeres comprise ~350 bp of imperfect repeats with the consensus (TG)0–6TGGGTGTG(G) [4, 5]. Like soldiers on the front lines of a battle, telomeres are critical to the protection and stability of internal chromosome sequences, a function known as telomere “capping”. In capping chromosome ends, telomeres restrict end resection by exonucleases and also prevent the improper activation of checkpoint response factors and DNA damage response pathways such as homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). In order to perform such a myriad of tasks, telomeres are endowed with a special type of armor that helps camouflage and protect them, even enabling them to subvert to their own ends the actions of potential foes, such as exonucleases and DNA damage response factors. In vertebrates, the core of this capping armor is called shelterin, a complex of proteins including (among others) the Myb-type homodomain proteins TRF1 and TRF2, which bind the duplex form of the telomere repeats, and the OB-fold containing protein POT1, which binds the single-stranded telomere overhang [3]. A similar arrangement is present in most other eukaryotes. For example, in the yeast S. cerevisiae the Myb-type homodomain protein Rap1 binds the duplex telomere repeats, and the OB-fold protein Cdc13 binds the 3′ overhang [6]. Remarkably, even factors such as ATM and Ku, which normally respond to the DNA termini exposed during double strand breaks by activating cell cycle checkpoint responses and initiating repair to rejoin the breaks, are enlisted by shelterin to instead help maintain telomere structure and function [7–10]. In many organisms (though apparently not in S. cerevisiae) telomeres can form a loop structure, called a t-loop (Fig 1A), in which the 3′ end of the single stranded overhang invades at the base of the telomere repeats to form a D-loop [11, 12]. Correlative evidence indicates that t-loops may be a critical component of the capping mechanism [13–15], but as described below, they may also present challenges to telomere replication and induce recombination-based deletion events. In addition, evidence is accumulating that another non-canonical set of structures called G-quadruplexes can form among telomere repeats. G-quadruplexes are stacked associations of G-quartets, which are themselves planar assemblies of four Hoogsteen-bonded guanines, with the guanines derived from one or more nucleic acid strands [16, 17]. The formation of such secondary DNA structures may also pose special problems for telomere maintenance, because their resolution would be necessary for the efficient completion of DNA replication (Fig. 1B–C).

Figure 1.

Potential secondary structures at telomeres. A) Through the assistance of TRF2 and perhaps other factors, the 3′ overhang loops back and invades into internal telomere repeats forming a t-loop. This is thought to help protect the telomere terminus from further exonucleolytic processing and to prevent it from inappropriately activating checkpoint proteins. B) The general structures of a G-quartet (left) and of an intramolecular G-quadruplex (right) are shown. C) Illustration of a G-quadruplex that has formed at the 3′ overhang, although it is possible that G-quadruplexes also form among internal telomere repeats, particularly under conditions where they become single-stranded, e.g. replication and recombination.

Telomeres shorten as cells divide, in part because the DNA replication machinery is incapable of fully copying the ends of linear molecules, but also due to resection by exonucleases, oxidative damage and inappropriate recombination events [18]. Telomerase, a reverse transcriptase that carries its own RNA template which codes for telomere repeats, can lengthen telomeres and thus counteract telomere shortening [2]. However, most human cells lack sufficient telomerase to maintain telomere length, and so their telomeres gradually shorten. When telomeres shorten to a critical length, telomeres become uncapped, which can lead to permanent cell cycle arrest (termed cellular senescence) or apoptosis, depending on the cellular context in which the uncapping occurs [19]. Telomere shortening clearly limits the replicative lifespan of many different human cells in culture, including fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells, because the artificial expression of telomerase can effectively immortalize these cells [20–22]. Telomeres shorten with age in many human tissues, including skin, kidney, liver, pancreas, blood vessels and leukocytes in peripheral blood [23, 24].

Much evidence supports the idea that short telomeres contribute to age-associated pathology. For example, individuals over the age of 60 who have telomeres in the bottom half of telomere length distribution have 1.9-fold higher mortality rates than age-matched individuals with telomere lengths in the top half of the distribution, and telomere length is heritable and associated with parental lifespan [25, 26]. Similarly, increased telomere length is correlated with improved left ventricular function and reduced cardiovascular disease risk, improved bone density and oocyte function, and reduced poststroke mortality and dementia [27–31]. Particularly short telomeres and markers of cell senescence are present at sites of pathology, including atherosclerotic vessels and cirrhotic liver nodules [32, 33]. Because short telomeres are associated with age-related pathology, it is not surprising that telomerase deficiency also correlates with age-related disease. For example, individuals with dyskeratosis congenita, who have a ~50% decrease in telomerase activity, suffer from several age-associated pathologies such as bone marrow failure and osteoporosis [34]. Similarly, people with other hypomorphic mutations in telomerase, or short telomeres in the absence of an apparent telomerase mutation, are at increased risk for bone marrow failure, pulmonary fibrosis and liver cirrhosis [35–38]. In addition, several lines of evidence (described below) indicate that telomere defects contribute centrally to the pathogenesis of the Werner premature aging syndrome [39–42], and shortened telomeres are found in other progeroid syndromes including Hutchinson-Gilford progeria (HGP) and ataxia telangiectasia [43]. The artificial overexpression of telomerase has recently been shown to reverse some of the cellular effects of the altered form of lamin A, called progerin, that causes HGP [44], which is consistent with the idea that telomere dysfunction contributes to pathogenesis in this disease. The development of the “TIF” (telomere dysfunction induced foci) assay that is based on colocalization of the DNA repair factors 53BP1 and γH2AX with uncapped telomeres has begun to allow measurement of telomere uncapping in aged tissues [45–48]. Remarkably, TIF+ nuclei increase exponentially with age in baboon dermis, are associated with markers of cell senescence, and are found in approximately 20% of dermal fibroblasts in the oldest individuals [49, 50]. Finally, telomere shortening appears to play important roles in cancer, a major age-related disease, where it both limits the progression of precancerous lesions into mature tumors and, at the same time, can contribute to genome instability in the rare neoplastic cells that progress through the proliferative barriers set by telomere attrition [51, 52]. Although definitive proof that improved telomere maintenance will mollify age-related disease is currently not available, there is good evidence that telomeres play an important role in human age-related diseases. Thus, efforts to understand mechanisms of telomere maintenance and dysfunction are expected to contribute to our understanding of the natural aging process and hopefully will provide targets for ameliorating diseases of aging, including cancer.

2. HELICASE STRUCTURE, MECHANISM, AND CLASSIFICATION

Helicases catalyze the hydrolysis of nucleotide triphosphates (typically ATP) and convert this chemical energy into mechanical energy that enables the separation of base-paired strands of nucleic acids [53, 54]. One example of this is the “melting” of duplex DNA into its constituent single strands. All DNA helicase monomers have a pair of adjacent RecA-like domains that create a site for NTP binding and hydrolysis at their interface and participate together in nucleic acid binding. Cycles of nucleotide binding, hydrolysis, and release drive structural changes in the helicase that lead to its movement along the nucleic acid substrate and ultimately to strand separation. Helicases can differ in their substrate specificity (e.g. DNA vs. RNA; requirement for single strand overhangs for loading), directionality of translocation (5′-to-3′ or 3′-to-5′ along the bound strand), ability to translocate along single vs. duplex substrates, oligomeric structure (e.g. monomeric vs. hexameric), processivity, and their ability to do more than simply separate strands (e.g. to displace bound proteins from DNA). Helicases are currently classified into six superfamilies, SF1-6, based largely on conserved motifs within their NTP and DNA binding regions [54]. The N- and C-terminal protein sequences that usually flank the “core” catalytic helicase domain add additional layers of complexity to helicase function by determining substrate specificity (e.g. the HRDC domain within RecQ family members), providing binding sites for cooperating proteins (e.g. Topoisomerase IIIα binding to BLM), or adding novel catalytic activities (e.g. the nuclease domains present in the archaeal Hef or mammalian WRN proteins) [55, 56]. Different helicases are thus endowed with tools to facilitate different aspects of telomere maintenance and function. The importance of helicases for human health is underscored by the several genome instability diseases that can be caused by helicase deficiencies, including the Werner and Bloom syndromes, Fanconi anemia, Cockayne syndrome, xeroderma pigmentosum, and tricothiodystrophy [57]. Helicases are part of a larger family of nucleic acid translocases, the other members of which do not couple their motion to strand separation [54]. These other enzymes are structurally and mechanistically very similar to helicases, and some even play important roles in telomere and telomerase regulation (e.g. Pontin, Reptin [58]), but the scope of this review is limited to bona fide helicases.

3. HELICASE FUNCTIONS AT TELOMERES

The specialized characteristics of telomeres outlined above begin to explain why helicases play important roles in their maintenance. Helicase functions at telomeres can be divided into those serving in replication, end processing and capping, telomerase-mediated extension, telomere chromatin remodeling, responses to uncapped telomeres, and recombination-dependent maintenance of telomeres. Each of the following sections will describe a particular telomere function and briefly discuss any helicases that appear to play a role restricted to that particular function. Helicases with roles in multiple telomere functions will then be examined in more detail further below.

Telomere replication

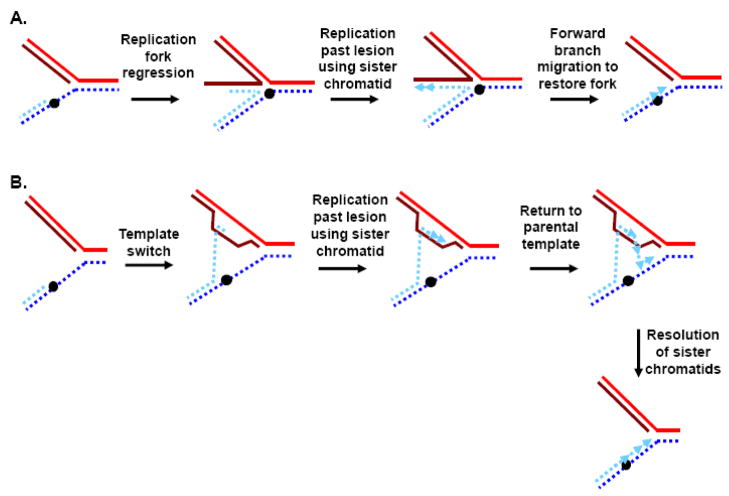

Telomeres provide several challenges to the DNA replication machinery [9, 59–61], and helicases may help overcome these obstacles. First, telomeres are bound by proteins that might impede the progression of replication forks, and a helicase moving ahead of the fork could help remove these proteins. Importantly, it isn’t yet clear to what extent particular telomere proteins inhibit or promote replication, because although some, e.g. TRF1, have been shown to impede replication in an in vitro system and perhaps in vivo, others, e.g. the S. pombe TRF1/2 homologue Taz1, actually facilitate telomere replication in vivo [62, 63]. Second, telomere DNA can itself form secondary structures, such as T-loops or G-quadruplexes (Fig. 1), that might impede forks in a way that could be relieved by helicases capable of unwinding such structures [61]. Third, because replication initiates from origins, and not from DNA ends, replication ought to proceed unidirectionally from subtelomeric origins toward the telomere terminus. This has been demonstrated directly in S. cerevisiae [59, 64], and is probably also true for higher eukaryotes (although there are intriguing hints that replication might conceivably be able to initiate within telomere repeat DNA in mammalian cells [65]). Such unidirectional replication prevents rescue of a collapsed replication fork by one approaching from the opposite direction, and therefore collapsed telomere forks must either be restarted or telomere loss events will occur. There are several mechanisms by which stalled forks can be stabilized and then enabled to replicate past damaged templates or by which collapsed forks can be restarted, and there is evidence for helicase functions in each of these [66–71]. For example, stalled or collapsed forks can either a) undergo reverse branch migration to form a “chicken-foot” structure, b) engage in HR-mediated template switching to bypass an inhibitory lesion, or c) undergo cleavage followed by invasion of the broken end into the intact duplex to form a new fork (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Examples of helicase-assisted mechanisms of replication fork rescue. A) A replication fork stalls or collapses at an inhibitory lesions (black dot). The replication fork can then regress via reverse branch migration to form a “chicken foot” structure, followed by copying of the newly synthesized sister strand to generate sequence beyond the lesion. Dissolution of the regressed chicken foot occurs by reverse branch migration, and replication resumes. Helicases could be involved at the branch migration steps. B) A lesion that blocks replication is bypassed by a switch in template from the parental strand to the newly replicated sister chromatid. Once the lesion has been bypassed, reinvasion back to the parental template can occur, and then resolution of entwined strands allows the sister chromatids to separate. Helicases could assist in the original template switch, the reinvasion step, and the final resolution step. C) If a collapsed fork leads to a double strand break, resection of the broken DNA end to generate a recombinogenic 3′ end allows invasion of the intact chromatid and resumption of DNA synthesis. Branch migration of the D-loop (to the left) establishes a full Holliday junction, thus allowing the resumption of replication. Helicases could assist in end-processing, invasion and branch migration.

Telomere end processing

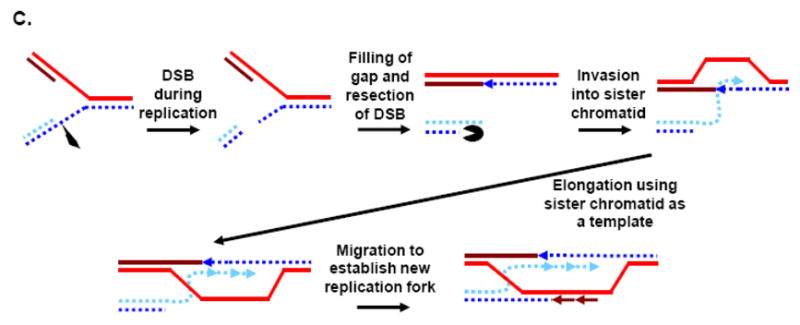

The replication products of both leading and lagging strand synthesis at telomeres require processing to generate the 3′ G-rich overhangs, which are ~12–14 nt and ~50–200 nt in length in S. cerevisiae and in human cells, respectively (Fig. 3). The product of leading strand synthesis is presumably a blunt ended (or 5′ overhang-containing) duplex, and so to produce the necessary 3′ overhang, processing of the C-rich strand by nucleases must occur. The nuclease(s) performing this task remain largely unidentified, although an exception may be Mre11, which is required to generate full overhang length in S. cerevisiae [72]. However, it isn’t clear whether its nuclease activity or its other functions within the Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 complex is involved. Furthermore, the fact that a similar requirement for MRE11 for full overhang length in human cells is dependent on telomerase suggests that extension of the overhang by telomerase, rather than resection of the C-rich strand, is the key Mre11-dependent process [72, 73]. Regardless, it is clear that telomere overhangs exist independently of telomerase [74, 75], and helicases could facilitate resection of the C-rich strand by nucleases to establish these overhangs. The product of lagging strand synthesis at telomeres naturally has a 3′ overhang because even if the ultimate RNA primer of lagging strand synthesis were to begin at the telomere terminus, a gap would remain after its removal; furthermore, there is some evidence in human cells indicating that the final RNA primer does not lie at the terminus [61]. In either case, helicase activity could still be involved in processing the lagging strand product, because the normal mechanism of RNA primer displacement by encroaching DNA polymerase δ does not exist at the terminus, and a helicase could substitute to help displace the primer so that the newly-exposed lagging strand product could be cleaved by nucleases such as FEN1 and DNA2 [76].

Figure 3.

End-processing of telomeres after replication. The G-rich strand is replicated by lagging strand synthesis, and even with fully efficient lagging strand synthesis the removal of the terminal RNA primer allows for the generation of a 3′ overhang. Helicases could assist with RNA primer removal and might also aid with additional nucleolytic processing. The C-rich strand is replicated via leading strand synthesis and therefore for the 3′ overhang to be generated, the activity of exonucleases and/or endonucleases such as the Mre11 are required, which could be assisted by helicases.

Telomerase regulation

To extend the single-stranded G-rich 3′ telomere overhang, telomerase must first base pair part of its internal RNA template with the single-stranded telomere terminus. Telomerase activity at the telomere can therefore be inhibited if the overhang adopts secondary structures that inhibit such pairing, such as t-loops or G-quadruplexes [16]. By unwinding such secondary structures, helicases could stimulate extension of telomeres by telomerase. In contrast, helicases tracking along the telomere overhang could also displace telomerase and thus inhibit telomere extension [77]. Finally, there is some evidence that the telomerase template RNA itself can form G-quadruplexes that inhibit telomerase activity [78], and helicases might regulate telomerase activity by unwinding such secondary structures.

TERRA and telomere chromatin

Telomeres bear several marks of heterochromatin and can repress transcription from subtelomeric promoters [79]. Somewhat surprising, then, are the recent demonstrations that the telomere repeats are transcribed by RNA polymerase II in human, murine, and S. cerevisiae cells [80–82]. The RNA products, called TERRA (telomere repeat-containing RNA), are primarily transcribed from the C-rich strand and are thus themselves G-rich. TERRA molecules are nuclear and associate with telomere chromatin. Increased association correlates with telomere loss events in human cells and inhibits extension of telomeres by telomerase in yeast [80, 81]. How TERRA associates with telomeres has not been characterized, and although telomere proteins may certainly be involved, another intriguing possibility is that intermolecular RNA-DNA G-quadruplexes or G-loops (in which an RNA-DNA duplex between TERRA and the telomere C-rich strand would be stabilized by G-quadruplex formation on the displaced G-rich strand [83]) help mediate the interaction [61, 84]. In mammals, TERRA is dissociated from the telomere by the UPF1 5′-3′ RNA helicase [81], which is part of the nonsense-mediated mRNA degradation pathway, but the mechanism of dissociation is unknown. Similar inhibition of TERRA-telomere association has not yet been demonstrated for yeast Upf1, but upf1Δ mutants have shortened telomeres, consistent with such a role [85]. TERRA levels are decreased in several types of cancer [82], raising the possibility that TERRA might be a useful target for cancer therapeutics. However, the potential functional roles of TERRA in cell senescence, carcinogenesis and cancer growth are untested.

Processing uncapped telomeres

Perturbation of the proteins that compose telomere chromatin or critical shortening of the telomere repeat DNA can each cause telomeres to uncap. Examples are yeast cdc13-1 mutants, which upon shifting to a non-permissive temperature, lose Cdc13-dependent capping [86], and eukaryotic cells in which telomerase is either naturally absent or has been genetically disabled and which are then allowed to divide to the point of telomere shortening [45, 48]. Once telomeres become uncapped by these manipulations, nucleolytic resection of the C-rich strand leads to single strand DNA accumulation, which helps activate checkpoint responses [86, 87]. Exonuclease I is a key player, because both yeast and murine cells lacking Exo1 have reduced ssDNA generation at uncapped telomeres [86, 88, 89]. At generic DNA duplex ends, exonuclease activity can be stimulated by DNA helicases, including the RecQ family helicases Sgs1 and BLM (see below) [90–92]. This is presumably because DNA secondary structures or bound proteins, which can be removed by helicases, impede exonuclease progression. Similar helicase-mediated stimulation of telomere end-resection may also occur, although the telomere DNA and protein structures may affect certain details, such as which helicases are most important.

Telomere recombination

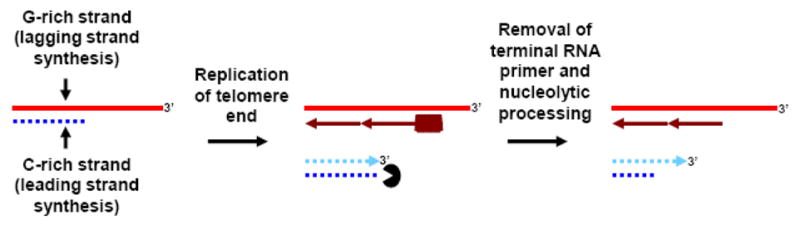

Uncapped telomeres can be engaged by DNA repair pathways, including NHEJ and different subpathways of HR. One possible outcome is telomere end-to-end fusions, which are of particular importance in carcinogenesis [93, 94]. This is because any incipient cancer cells that manage to pass through the barriers of apoptosis or cell senescence imposed by critically shortened telomeres can emerge from these barriers with aneuploidy caused by chromosome fusion-bridge-breakage events that arise from telomere fusions. Telomere fusions mediated by NHEJ are not known to be affected by helicases. However, fusions in S. pombe induced by genetic inactivation of Pot1 were found recently to result from single-strand annealing (SSA) rather than NHEJ [95]. SSA is a type of HR that involves base pairing of complementary 3′ ssDNA ends generated by 5′-to-3′ end resection (Fig. 4). The telomere fusions described in S. pombe pot1− mutants were found to require the 5′-to-3′ helicase Srs2, which is required generally for SSA involving long non-homologous 3′ tails [96]. Unexpectedly, they also required the 3′-to 5′ RecQ-family helicase Rqh1, which might function in this setting to unwind secondary structures formed by single-strand telomere repeats, such as G-quadruplexes, or to exonucleolytically process the DNA ends (see below). In contradistinction to mechanisms that lead to fusions, HR pathways different from SSA can support telomere length maintenance in the absence of telomerase. Examples are mechanisms supporting telomere maintenance in yeast telomerase mutants that have escaped the death that occurs in most cells due to telomere shortening, thus forming so-called “survivors”, and in some types of telomerase-negative human tumors, classified as “ALT”, for alternative lengthening of telomeres [97]. In simple terms, HR-dependent telomere maintenance involves a short telomere invading a longer telomere that in turn serves as a template to direct DNA synthesis and thus elongation of the shortened telomere. The many interesting details of such events are reviewed elsewhere [97, 98]. There is also evidence that HR mechanisms help maintain telomeres in dividing cells lacking telomerase as well as cause telomere lengthening in preblastoderm mouse embryos [99–101]. Further, as discussed below, helicases in the RecQ family play important roles in HR-dependent telomere maintenance.

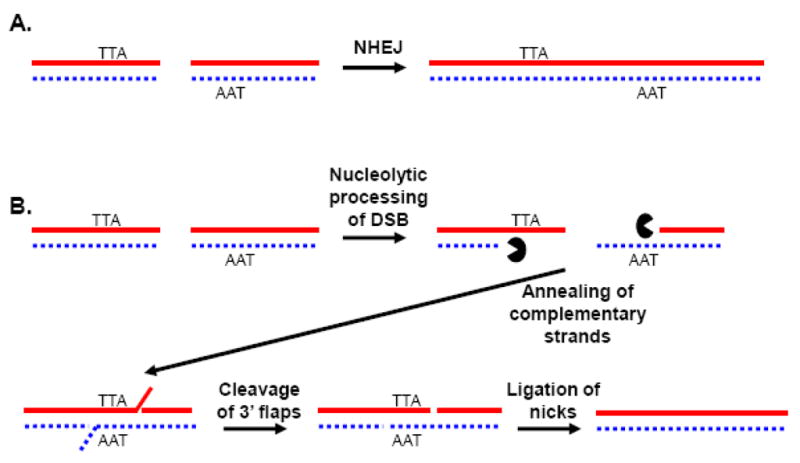

Figure 4.

Depictions of the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and single-strand annealing (SSA) pathways of DSB repair. A) In NHEJ, double strand breaks are essentially re-ligated back together. B) In SSA, nucleolytic processing of DNA ends (perhaps dependent upon RecQ-family helicases) occurs, and regions of homology are utilized to help guide the ligation of DNA breaks. The non-homologous 3′ flaps are removed by nucleases, such as Rad1/10, which can be assisted by the Srs2 helicase when the flaps are long.

4. HELICASES WITH DIVERSE ACTIVITES AT TELOMERES

RecQ-family

The RecQ family of proteins are SF2-type helicases that track along ssDNA with 3′-to-5′ polarity, and their structure and functions have been reviewed recently: [57, 71, 102]. They are among the most studied helicases because loss-of-function mutations in three of the five human RecQ family proteins, WRN, BLM and RecQ4, lead to the Werner, Bloom and Rothmund-Thomson genome instability syndromes, respectively (WS, BS and RTS). Although these diseases are very rare, they are of broad interest because they are characterized by elevated rates of cancer and premature features of aging, particularly in the cases of BS and WS, respectively. Studies of the human proteins and of their homologues in model organisms have provided evidence for their involvement in several aspects of DNA metabolism, including regulation of homologous recombination, replication, base-excision repair, transcription, and intra-S phase checkpoint responses. Of note, RecQ4 might not be an actual helicase, because the purified protein apparently lacks helicase activity in vitro, although it does possess ATPase and ssDNA annealing activities [103]. It will be important to determine whether cofactors might enable RecQ4 helicase activity, if it is perhaps active in unwinding substrates different from those tested, or if it instead functions in a different capacity, e.g. as a translocase. Many RecQ-family helicases are particularly adept at unwinding non-canonical DNA substrates. Substrates defined in vitro include forked duplexes and replication forks, bubbles, X-structures, double Holliday junctions, D-loops, and G-quadruplexes [104–112]. WRN, BLM and Sgs1, but not RECQ1, unwind G-quadruplexes [108–111, 113]. Moreover, direct substrate competition experiments indicate that Sgs1 and BLM are approximately an order of magnitude more active in unwinding G-quadruplexes than other favored substrates [111]. Similarly, the kinetics of G4-DNA unwinding by WRN and BLM are greater than for other substrates [107]. Also of note, the WRN protein distinguishes itself from the rest of its family by containing a 3′-to-5′ dsDNA-dependent exonuclease domain ensconced near its N-terminus [114, 115]. Several RecQ family helicases have been shown to function at telomeres, including mammalian WRN and BLM, S. cerevisiae Sgs1, and S. pombe Rqh1 and Tlh1.

A role for WRN in telomere maintenance was first suggested by the premature senescence and elevated telomere shortening rates of cultured fibroblasts from individuals with WS [116, 117]. The partial localization of BLM at telomeres and the capacity of overexpressed BLM to lengthen telomeres in ALT cells, which use telomere recombination rather than telomerase to maintain telomere lengths, indicated that BLM also can function at telomeres [118, 119]. Studies of the WRN and BLM homolog Sgs1 in yeast then demonstrated that in cells lacking telomerase, this RecQ family helicase helped slow senescence and also facilitated the formation of ALT-like recombination-dependent survivors of telomere shortening [120–122]. The partial localization of WRN to telomeres in ALT and telomerase-positive cells also supported a telomere role, as did demonstrations that TRF2 binds WRN and BLM directly [119, 122–125]. One additional and particularly fascinating line of evidence came from studies of the smut fungus U. maydis and yeast S. pombe, where RecQ family helicase genes are located at subtelomeric regions [126, 127]. Genes located near telomere ends are subject to reversible transcriptional repression, referred to as telomere position effect (TPE), which has been shown to occur in a wide range of eukaryotes from S. cerevisiae to mice and humans [79, 128, 129]. Although their transcription is repressed in wild type cells, which possess telomerase, when telomeres shorten in the absence of telomerase, the transcript levels of these subtelomeric RecQ genes are increased, raising the possibility that these helicases may have important roles in the emergence of telomerase-independent survivors. Indeed data supporting this notion come from S. pombe where the overexpression of the native or an apparent dominant-negative form of the putative RecQ-related helicase Tlh1 (SPAC212.11) leads to a swifter or delayed recovery from critical telomere shortening in telomerase mutants, respectively [126]. Of note, a non-RecQ-family helicase, Y’-Help1, is positioned at similar subtelomeric positions in S. cerevisiae and is highly expressed in cells with critically shortened telomeres [130]. In normal cells, the subtelomeric locale of these helicases might enable cells to use HR to repair a telomere that has been suddenly and critically shortened by DNA damage.

The WRN protein has many apparent functions, but knowing which is of central importance for driving the human WS phenotype is difficult because all people with WS appear to have null alleles [131], thus preventing mapping of domains with particular biochemical functions to the disease phenotypes. However studies in mice argue for a particularly important role of WRN at telomeres. Mice lacking WRN are relatively (though not completely) unaffected, and this may be because the longer telomeres and more abundant telomerase activity in mice, relative to in humans, mask the telomere defects that might otherwise occur in the absence of WRN (because a telomere loss event caused by WRN deficiency could be repaired by telomerase) [132, 133]. However, when telomerase is inactivated genetically (in mTerc−/− mutants, which lack the telomerase RNA template), a clear role for WRN in mice becomes apparent, and the mTerc−/− and Wrn−/− mutations synergize to cause degenerative pathologies in many tissues [39, 41, 134]. This may explain why most degenerative pathologies in WS lie in mesenchymal tissues, where telomerase expression is at its lowest, thus allowing any telomere defect caused by WRN deficiency to have a profound effect. In mice, Blm deficiency has an even greater effect on pathology in combination with mTerc deficiency than does Wrn deletion [39]. However, in humans with BS, a telomere defect may be less relevant to pathology because BLM expression is most prominent in tissues, such as lymphocytes, that can express high levels of telomerase, which could repair telomere lesions that might be caused by BLM deficiency [39, 135]. We want to emphasize that while degenerative pathologies might be significantly impacted by telomere dysfunction in WS, and perhaps BS, it is likely that the elevated rates of malignancies in these syndromes are caused by widespread genome instability at regions outside the telomere, presumably related to roles for WRN and BLM in DNA recombination, replication fork stabilization and DNA damage checkpoint responses [136–138]. Nonetheless, evidence for an unexpectedly significant role for telomere dysfunction in driving widespread genome instability in WS cells has been reported [42].

How do RecQ-family helicases affect telomere metabolism? Based on the available evidence, a challengingly large number of potential mechanisms appear to exist. While not mutually exclusive, it seems likely that only a few will prove to be of primary importance. Elegant biochemical studies using purified WRN and defined substrates implicate the helicase in reactions that could encourage replication fork progression at telomeres including 1) enhancement of DNA polymerase delta processivity [139–141], 2) stimulation of translesion synthesis by direct stimulation of translesion polymerases or by unwinding secondary structures formed at stalled forks [67, 142], and dissolution of 3) t-loops or 4) G-quadruplexes which might form at telomere ends [40, 107, 108, 110, 125, 143, 144]. T-loops and G-quadruplexes could each impede replication fork progression, and POT1 could facilitate unwinding of either because it stimulates WRN (and also BLM) helicase activity and may be bound at the displaced single stranded DNA at a t-loop; furthermore, POT1 itself inhibits G-quadruplex formation by binding to the single-stranded conformation [144–146]. TRF2 could also be involved in t-loop unwinding because it binds and stimulates the helicase activity of WRN (and BLM) [123]. TRF2 induces positive DNA supercoiling and thus presumably binds positively supercoiled DNA more tightly than relaxed DNA. TRF2 could therefore accumulate at the positive supercoils created in front of advancing replication forks that are topologically constrained by a t-loop and then stimulate WRN to remove the t-loop, thus enabling the fork to advance further [61, 147]. In vitro studies suggest that WRN exonuclease activity may also help dissolve t-loops by degrading the telomere 3′ overhang that is inserted at the base of the t-loop [125, 143]. Thus the combined actions of WRN helicase and exonuclease activities may make it particularly well suited to removing these potential impediments to telomere replication. Finally, 5) WRN may play a role in resolving intermediates generated by template-switching mechanisms that enable replication forks to bypass stall-inducing lesions [67]. In vivo studies provide some support for each of these five models. Models 1 and 2 are supported by studies showing that replication fork progression is impaired in WS cells on a genome-wide level, particularly under conditions of replication stress, although the extent to which this applies to telomeres is unknown [148, 149]. There is no direct in vivo support for model 3, even though it is quite plausible. However, there is some evidence that may bear on this issue. WRN appears to modulate the generation of t-circles, which are circular duplexes comprising telomere repeats [150]. WRN reportedly enhances an HR-dependent form of t-circle genesis caused by expression of the mutant form of TRF2 lacking its basic domain (TRF2ΔB) [151] (although the original study did not observe a clear requirement for WRN [150]). One model for t-circle formation involves a modified t-loop that contains a double HJ (Fig. 5). When such a structure is resolved so that a crossover occurs, the circle can be deleted from the ends [152]. WRN might help form the double HJ t-loop by catalyzing branch migration of a standard t-loop. In contrast, WRN prevents HR-independent t-circle formation [151], conceivably by preventing replication-associated breaks that could occur if t-loops are not unwound. Model 5 is supported by studies showing that WRN promotes cell survival and resolves HR intermediates [153, 154], and by the demonstration that Sgs1 prevents rapid telomere loss by resolving replication-associated HR intermediates at telomeres [101, 155]. It is also possible that WRN functions at G-quadruplexes forming on single-stranded regions of telomere HR intermediates, thus unifying mechanisms 4 and 5. A remarkable study by Jan Karlseder’s group demonstrated a role for WRN in preventing rare telomere loss events occurring preferentially at the products of lagging strand synthesis, called sister telomere losses (STL) [40]. WRN helicase, but not exonuclease, activity prevents STL. Because telomere replication initiates from an internal origin, lagging strand synthesis occurs on the G-rich template, and so this raised the possibility that an inability of WS cells to resolve G-quadruplexes, or to remove proteins bound to other telomere-specific structures, such as Pot1 from the G-rich strand of a t-loop, during telomere replication explains the defect. However direct evidence for these ideas remains to be demonstrated. Nonetheless, two recent findings in S. cerevisiae suggest in vivo roles for G-quadruplexes that involve a RecQ helicase and telomeres. First, the genes that have altered expression in sgs1 mutants are preferentially those with the potential to form intramolecular G-quadruplexes, arguing that Sgs1 can regulate gene expression by unwinding G-quadruplexes [156]. Second, a screen of all viable haploid deletion mutants for those conferring enhancement or suppression of growth inhibition by the selective G-quadruplex ligand N-methyl mesoporphyrin IX revealed a set of mutants that was significantly enriched for telomere maintenance factors, indicating that G-quadruplexes affect telomere function in yeast [156]. Also of interest, telomere chromatin appears to play an important role in telomere maintenance by WRN because human cells deficient in the SirT6 histone H3K9 deacetylase are unable to recruit WRN to telomeres and have elevated rates of STL [157].

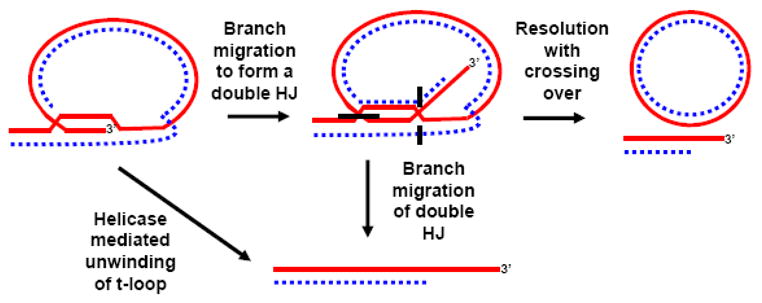

Figure 5.

t-loop dynamics. A standard t-loop might be unwound by a helicase (e.g. WRN or BLM) to facilitate replication of the telomere. In addition, a helicase (e.g. WRN), perhaps working together with HR factors, could allow a t-loop to branch migrate to form a double HJ at its base. If resolved with crossing over (e.g. by a classical HJ resolvase or by the concerted action of nucleases), this could lead to telomere truncation and t-circle formation. BLM, together with Topo IIIα, can resolve a double HJ in the middle of extensive flanking sequences and could thus dissolve a double HJ t-loop. Also, because a double HJ t-loop is near an end, other helicases, such as WRN may be able to remove it by simple branch migration

RecQ helicases play important roles in HR-dependent telomere maintenance, as noted above. BLM activity extends telomeres in human ALT cells, Tlh1 promotes survival in S. pombe lacking telomerase, and Sgs1 enables the formation of one form of telomerase-independent survivor in S. cerevisiae [119, 122, 126]. The Sgs1-dependent survivors are called type II and have amplified telomere repeat tracts of variable length similar to human ALT cells; this contrasts with type I survivors which are Sgs1-independent and have amplified subtelomeric sequences. In contrast to the pro-telomere HR functions of BLM, Tlh1, and Sgs1 there is evidence for inhibition of ALT by WRN, because cultured murine mTerc−/− Wrn−/− fibroblasts apparently adopt an ALT phenotype more readily than mTerc−/− Wrn+/+ controls [158]. Consistent with this finding, the double mutant cells also displayed higher rates of telomere sister chromatid exchanges and of telomere double-minute chromosome formation. Increased telomere recombination help explain the elevated incidence of mesenchymal tumors in WS, because such tumors in normal individuals are particularly prone to using an ALT mechanism of telomere maintenance [97, 159]. It would be interesting to test if WS mesenchymal tumors have a particularly high prevalence of ALT. On the other hand, WRN might sometimes promote, rather than inhibit, a standard ALT phenotype because one ALT cell line derived from an individual with WS and then immortalized with SV40 T-antigen has a telomere structure similar to type I yeast survivors, although the contribution of the Wrn mutation to the phenotype has not been demonstrated [160]. Further, WRN, like BLM, can substitute for Sgs1 in yeast to enable type II survivors to form [120, 161]. The distinction between a clear stimulation of HR-dependent telomere maintenance by BLM and Sgs1, and inhibition or less robust stimulation by WRN, might be explained by the association of the first two helicases with topoisomerase III, which does not interact with WRN [162–164]. Yeast top3Δ mutants fail to form type II survivors of telomerase deletion, and downregulation of topoisomerase III alpha interferes with ALT in human cells [165, 166]. Perhaps the combined action of a helicase with the strand-passage activity of a topoisomerase III protein facilitates efficient resolution of telomere recombination intermediates.

A newly recognized function for Sgs1 and BLM that is likely to be important at telomeres is the stimulation of 5′-to-3′ exonucleolytic end resection of duplex DNA ends. At breaks induced by the HO endonuclease, Sgs1 helicase activity stimulated end-resection by approximately four-fold, and the target of stimulation was found to be the Dna2 exonuclease [90–92]. Dna2 also possesses helicase activity itself, but this is dispensable for its end-resection activity [92]. In human cells siRNA-mediated knockdown of BLM diminished the appearance of ssDNA after camptothecin treatment, as assessed by the phosphorylation of, and nuclear focus formation by, the RPA single-strand DNA binding complex [90]. Sgs1/Dna2 and BLM appear to function at breaks largely in parallel with yeast Exo1 and human EXO1, respectively. However, the direct binding of EXO1 to WRN, as well as the stimulation of EXO1-mediated cleavage by WRN, suggest that RecQ helicases can also function together with Exo1/EXO1 [167]. Recently sgs1 deletion was found to allow yeast cells lacking both telomerase and HR (e.g. tlc1 rad52 mutants, which otherwise die because they cannot maintain telomeres) to grow indefinitely despite the eventual loss of telomere sequences [168]. Slowed end-resection might explain this observation because exo1 deletion has a similar effect [168, 169]. These findings raise the possibility that some of the functions of RecQ-family proteins in telomere HR stem from a role in generating recombinogenic 3′ single-stranded ends, instead of, or more likely in addition to, resolving HR intermediates. Moreover, it is possible that RecQ helicases might influence the exonucleolytic processing of telomere ends, for example after replication or upon telomere uncapping. The suppression of telomere loss by deletion of the Rqh1 RecQ-family helicase in S. pombe mutants with telomere protection defects (taz1-d rad11-D223Y double mutants, which lack the Taz1 telomere repeat binding factor and have a hypomorphic form of RPA) is consistent with the latter possibility [170]. Precisely how Sgs1 and BLM stimulate end-resection is unknown, but a reasonable possibility is that they remove DNA secondary structures that could impede exonuclease progression. G-quadruplex or other secondary structures formed at telomeres might thus make resection of telomeres particularly dependent on aid from helicases. Another possibility is that RecQ helicases might unwind telomere ends to reveal a 5′ ssDNA flap that could be cleaved by endonucleases like Dna2 or FEN1 [170]. Consistent with this possibility, WRN and BLM each bind and stimulate the nuclease activity of FEN1 [171–173]. Remarkably, defects in telomere replication via lagging but not leading strand synthesis caused by knockdown of FEN1 led to STL events similar to those observed in WS cells [174]. An allele of FEN1 that disrupts its interaction with WRN did not rescue the STL, arguing for the importance of the WRN-FEN1 interaction. However, inhibition of STL by WRN requires its helicase activity [40], whereas stimulation of FEN1 is independent of WRN helicase activity [172], and thus the precise contributions of each protein, and their cooperative interaction, to the suppression of STL are not yet clear.

Pif1 family

The Pif1 family of proteins is a set of SF1-type DNA helicases that are conserved among all eukaryotes and translocate along ssDNA in the 5′ to 3′ direction. Pif1 family members have been shown to have roles in the maintenance of both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, including important roles at telomeres. In S. cerevisiae there are two Pif1 family members, Pif1 and Rrm3, but most other eukaryotes have only one Pif1 homolog [175].

As first shown in S. cerevisiae, Pif1 proteins negatively regulate telomerase activity by removing telomerase complexes from telomere ends [77, 176]. In vitro, yeast and human Pif1 limit the processivity of telomerase [177]. In vivo, yeast pif1 deletion leads to a telomerase-dependent increase in telomere length, whereas overexpression of yeast Pif1 shortens telomeres and inhibits the occupancy of telomere ends by telomerase [77]. Overexpression of human Pif1 in telomerase-positive HT1080 cells also reportedly shortens telomeres [177]. The ability of yeast Pif1 to inhibit telomerase activity was recently found to depend on its interaction with the Est2 subunit of the telomerase holoenzyme [178]. This finding taken with the demonstration that Pif1 has a preference to unwind forked RNA-DNA hybrids, where the DNA strand has a 5′ overhang and thus acts as the loading strand [179], leads to the following model. Pif1 is recruited to telomere ends through its interaction with Est2, and it then selectively unwinds the RNA-DNA hybrid formed between the TLC1 telomerase template RNA and the associated telomere DNA end, thus limiting the activity of telomerase. An important corollary function to Pif1 action at telomeres is its inhibition of the “healing” of DSBs by telomerase. Such telomerase-mediated healing is stimulated over 200-fold by pif1 deletion in S. cerevisiae [180]. By preventing the conversion of DSBs to de novo telomeres, Pif1 allows cells to exert appropriate checkpoint responses to breaks and to then repair them by HR or NHEJ, thus promoting genome stability. Surprisingly, Snow and coworkers recently found that mouse Pif1p, although able to bind the catalytic subunit of telomerase (TERT), does not inhibit telomerase activity in vitro, and that murine cells from mice lacking Pif1 had normal telomere lengths, sensitivity to DNA damaging agents, and gross chromosome stability, even after successive generations of breeding in two different strain backgrounds [181]. More work is needed to determine if the unanticipated mouse results might be explained by redundant helicases or by differences in mouse telomere length or telomerase regulation.

Pif1 may also play additional roles at telomeres. For example, Pif1 has recently been found to be important for one pathway of Okazaki fragment cleavage, and so it has been proposed to also play a role in removing the terminal RNA primer at the start of the last telomeric Okazaki fragment [76]. In addition, deletion of the nuclear form of Pif1 suppresses the growth defect of cdc13-1 mutants at non-permissive temperatures [182, 183]. A mutation in the TLC1 telomerase template RNA that disrupts optimal association of telomerase with the telomere (tlc1Δ48) exacerbates the temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1 mutants, suggesting that pif1 deletion might enhance telomere capping by increasing the amount of telomerase bound at the telomere. However, it is also possible that absence of Pif1 could stabilize telomere secondary structures (e.g. G-quadruplexes) that might impede exonucleases.

The yeast Rrm3 protein appears to function primarily to promote DNA replication. Replication fork progression is slowed at numerous sites in cells lacking Rrm3, including the ribosomal DNA (rDNA), tRNA genes, centromeres, silent mating loci, subtelomeres and telomeres [60, 184]. Increased replication pausing in rrm3 mutants is associated with increased levels of DSBs and ectopic recombination, and enhanced dependence on factors that assist in DNA repair and in restarting collapsed replication forks, such as Mec1, and the Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 and Sgs1/Top3/Rmi1 complexes [185]. One indication of how Rrm3 promotes fork progression is that it moves with the replication apparatus and can associate physically with PCNA and DNA polymerase epsilon [186, 187]. The DNA sites of slowed replication in rrm3 mutants are bound by non-nucleosomal protein complexes, e.g. Fob1 at the rDNA, TFIIIc at tRNA genes, Rap1 at silent mating loci, and the Sir2/3/4 complex at telomeres [184, 188]. Deletion of Fob1 or mutation of TFIIIc or Rap1 binding sites can relieve replication pausing in a site-specific fashion in rrm3 mutants, and deletion of Sir proteins also has a modest effect on pausing at telomeres. This indicates that Rrm3 might help remove particular chromatin proteins to facilitate passage of the replication fork, although it might also function to unwind DNA secondary structures. It is noteworthy that tlc1 mutants, which lack the telomerase RNA template and thus telomerase activity, lose replicative capacity at a rate that is unaffected by Rrm3, indicating that any increased telomere damage in rrm3 mutants is efficiently repaired by backup pathways and thus does not accelerate telomere loss in the absence of telomerase [155].

FANCJ family

The FANCJ family of DNA helicases are SF2 5′-3′ helicases, and include mammalian FANCJ and RTEL, and C.elegans DOG-1 and RTEL-1 [189, 190]. FANCJ was first identified as being mutated in the germline of early-onset breast cancer patients, and was then found to be mutated in rare cases of the Fanconi anemia genome instability disorder [191, 192]. Among the FANCJ family of helicases, RTEL (Regulator of telomere length) has the clearest roles in telomere biology. It was originally implicated in telomere homeostasis following crosses between the Mus musculus and Mus spretus species of mice, which have long and short telomeres, respectively. The shorter Mus spretus telomeres are rapidly elongated in the derived F1 progeny of such matings, and the responsible dominant and trans-acting factor was mapped to a five cM area of chromosome 2 of Mus musculus by Zhu and colleagues [193]. The Lansdorp group later identified this factor as RTEL [194]. RTEL is most highly expressed in rapidly dividing tissues and upon differentiation. Consistent with this, Rtel−/− ES cells have a striking defect in embryoid body formation and display a variety of chromosomal abnormalities, the most prominent of which are chromosomal end-to-end fusions lacking detectable telomeric signal at the fusion site.

The mechanism through which RTEL maintains telomere integrity is unknown, but recently the human helicase was shown to disrupt preformed D-loops in vitro, similar to the S. cerevisiae Srs2 helicase [189, 195]. Taken together with the findings that C. elegans worms lacking RTEL-1 and human cells with siRNA-mediated knockdown of RTEL each show signs of elevated recombination, it appears that RTEL suppresses HR. This led to the suggestion that RTEL might prevent t-loop HR events leading to telomere losses (Fig. 5), or alternatively it might unwind t-loops to enable access of telomerase to the telomere end. It is unlikely that the latter mechanisms alone could explain all of the telomere defects because even mice with null alleles of telomerase require several generations of telomere shortening before telomere fusions occur. An earlier suggestion that RTEL might instead maintain telomeres by unwinding G-quadruplexes was based on its homology to C. elegans DOG-1, because dog-1 mutants show a striking and selective loss genome-wide of sequences having G-quadruplex forming potential [196]. However, RTEL is a closer homologue of RTEL-1, and rtel-1 mutant worms do not suffer from similar deletions [189]. Furthermore, dog-1 mutants do not suffer deletions at telomeres, although this may be because the C. elegans telomere repeat, (TTAGGC)n, has relatively low G-quadruplex forming potential [197]. In addition, the closest human homolog of DOG-1, FANCJ, unwinds G-quadruplexes in vitro and protects human cells from the toxicity of the G-quadruplex small molecule ligand telomestatin, arguing that perhaps DOG-1 and FANCJ are the members of the FANCJ helicase family that process G-quadruplexes [198]. Therefore, these findings make it unlikely that RTEL resolves telomere G-quadruplexes, although the ability of the protein to unwind G-quadruplexes has yet to be tested directly. It is also not known whether human FANCJ plays any roles in telomere maintenance. Further study should clarify the mechanisms by which this important family of helicases helps maintain telomeres and overall genome stability.

5. CONCLUSION

The importance of telomeres for the maintenance of genome stability and the pathogenesis of age-related degenerative diseases and cancer is becoming increasingly apparent. Helicases are critical regulators of several aspects of telomere metabolism, including telomere replication and recombination, end-processing and capping, extension by telomerase, and responses to uncapped telomeres. Werner syndrome is the human disease most likely to reflect the importance of telomere maintenance by helicases, although further work is needed to determine if telomeres are indeed the critical target of WRN in preventing age-related pathology and to demonstrate precisely how WRN maintains telomeres. Biochemical and genetic studies indicate that non-canonical DNA structures, including t-loops and G-quadruplexes, likely represent important substrates for helicases at telomeres, and these structures might provide targets for manipulating telomere function. Given the complexities of telomere processing and maintenance and the large number of helicases involved, as well as the lack of any apparent helicase that is dedicated to only a telomere target, targeting helicases to selectively manipulate telomere function will not be a simple task. Prospects for DNA helicases as therapeutic targets have been well reviewed recently elsewhere [199]. As more is learned about telomere form and function and their modulation by helicases, one can envision means by which these fascinating structures at the end of our chromosomes can be manipulated to the benefit of human health.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Johnson lab, Eric Brown, Roger Greenberg, Shelley Berger, Peter Adams, Ronen Marmorstein, Bob Pignolo, Chris Sell, Paul Lieberman, and Harold Riethman for discussions. We also thank Jay Johnson for Figure 1B. This work was supported by NIH grants R01-AG021521 and P01-AG031862. A. Chavez was supported by NIH T32-AG000255.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Riethman H. Human telomere structure and biology. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2008;9:1–19. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.021506.172017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan SR, Blackburn EH. Telomeres and telomerase. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:109–21. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Lange T. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2100–10. doi: 10.1101/gad.1346005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyne J, Ratliff RL, Moyzis RK. Conservation of the human telomere sequence (TTAGGG)n among vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7049–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forstemann K, Lingner J. Molecular basis for telomere repeat divergence in budding yeast. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 2001;21:7277–86. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7277-7286.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanoh J, Ishikawa F. Composition and conservation of the telomeric complex. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:2295–302. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3245-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey SM, Meyne J, Chen DJ, Kurimasa A, Li GC, Lehnert BE, Goodwin EH. DNA double-strand break repair proteins are required to cap the ends of mammalian chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14899–904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myung K, Ghosh G, Fattah FJ, Li G, Kim H, Dutia A, Pak E, Smith S, Hendrickson EA. Regulation of telomere length and suppression of genomic instability in human somatic cells by Ku86. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5050–9. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.5050-5059.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verdun RE, Karlseder J. The DNA damage machinery and homologous recombination pathway act consecutively to protect human telomeres. Cell. 2006;127:709–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabourin M, Zakian VA. ATM-like kinases and regulation of telomerase: lessons from yeast and mammals. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:337–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei C, Price M. Protecting the terminus: t-loops and telomere end-binding proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:2283–94. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3244-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith JD, Comeau L, Rosenfield S, Stansel RM, Bianchi A, Moss H, de Lange T. Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop. Cell. 1999;97:503–14. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stansel RM, de Lange T, Griffith JD. T-loop assembly in vitro involves binding of TRF2 near the 3′ telomeric overhang. Embo J. 2001;20:5532–40. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karlseder J, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. Senescence induced by altered telomere state, not telomere loss. Science. 2002;295:2446–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1069523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celli GB, de Lange T. DNA processing is not required for ATM-mediated telomere damage response after TRF2 deletion. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:712–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Cian A, Lacroix L, Douarre C, Temime-Smaali N, Trentesaux C, Riou JF, Mergny JL. Targeting telomeres and telomerase. Biochimie. 2008;90:131–155. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson JE, Smith JS, Kozak ML, Johnson FB. In vivo veritas: using yeast to probe the biological functions of G-quadruplexes. Biochimie. 2008;90:1250–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Zglinicki T, Martin-Ruiz CM. Telomeres as biomarkers for ageing and age-related diseases. Curr Mol Med. 2005;5:197–203. doi: 10.2174/1566524053586545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aubert G, Lansdorp PM. Telomeres and aging. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:557–79. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaziri H, Benchimol S. Reconstitution of telomerase activity in normal human cells leads to elongation of telomeres and extended replicative life span. Curr Biol. 1998;8:279–82. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt SE, Chiu CP, Morin GB, Barley CB, Shay JW, Lichtsteiner S, Wright WE. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science. 1998;279:349–52. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minamino T, Miyauchi H, Yoshida T, Tateno K, Kunieda T, Komuro I. Vascular cell senescence and vascular aging. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:175–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baird DM, Kipling D. The extent and significance of telomere loss with age. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1019:265–8. doi: 10.1196/annals.1297.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishii A, Nakamura K, Kishimoto H, Honma N, Aida J, Sawabe M, Arai T, Fujiwara M, Takeuchi F, Kato M, Oshimura M, Izumiyama N, Takubo K. Telomere shortening with aging in the human pancreas. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:882–6. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cawthon RM, Smith KR, O’Brien E, Sivatchenko A, Kerber RA. Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older. Lancet. 2003;361:393–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Njajou OT, Cawthon RM, Damcott CM, Wu SH, Ott S, Garant MJ, Blackburn EH, Mitchell BD, Shuldiner AR, Hsueh WC. Telomere length is paternally inherited and is associated with parental lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12135–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702703104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin-Ruiz C, Dickinson HO, Keys B, Rowan E, Kenny RA, Von Zglinicki T. Telomere length predicts poststroke mortality, dementia, and cognitive decline. Ann Neurol. 2006 doi: 10.1002/ana.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valdes AM, Richards JB, Gardner JP, Swaminathan R, Kimura M, Xiaobin L, Aviv A, Spector TD. Telomere length in leukocytes correlates with bone mineral density and is shorter in women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brouilette SW, Moore JS, McMahon AD, Thompson JR, Ford I, Shepherd J, Packard CJ, Samani NJ. Telomere length, risk of coronary heart disease, and statin treatment in the West of Scotland Primary Prevention Study: a nested case-control study. Lancet. 2007;369:107–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keefe DL, Liu L, Marquard K. Telomeres and aging-related meiotic dysfunction in women. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:139–43. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6466-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collerton J, Martin-Ruiz C, Kenny A, Barrass K, von Zglinicki T, Kirkwood T, Keavney B. Telomere length is associated with left ventricular function in the oldest old: the Newcastle 85+ study. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:172–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiemann SU, Satyanarayana A, Tsahuridu M, Tillmann HL, Zender L, Klempnauer J, Flemming P, Franco S, Blasco MA, Manns MP, Rudolph KL. Hepatocyte telomere shortening and senescence are general markers of human liver cirrhosis. Faseb J. 2002;16:935–42. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0977com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minamino T, Komuro I. Vascular cell senescence: contribution to atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2007;100:15–26. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000256837.40544.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bessler M, Wilson DB, Mason PJ. Dyskeratosis congenita and telomerase. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16:23–8. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200402000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alder JK, Chen JJ, Lancaster L, Danoff S, Su SC, Cogan JD, Vulto I, Xie M, Qi X, Tuder RM, Phillips JA, 3rd, Lansdorp PM, Loyd JE, Armanios MY. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13051–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804280105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, Alder JK, Ingersoll RG, Markin C, Lawson WE, Xie M, Vulto I, Phillips JA, 3rd, Lansdorp PM, Greider CW, Loyd JE. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1317–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia CK, Wright WE, Shay JW. Human diseases of telomerase dysfunction: insights into tissue aging. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7406–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsakiri KD, Cronkhite JT, Kuan PJ, Xing C, Raghu G, Weissler JC, Rosenblatt RL, Shay JW, Garcia CK. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7552–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701009104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du X, Shen J, Kugan N, Furth EE, Lombard DB, Cheung C, Pak S, Luo G, Pignolo RJ, DePinho RA, Guarente L, Johnson FB. Telomere shortening exposes functions for the mouse Werner and Bloom syndrome genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8437–46. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8437-8446.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crabbe L, Verdun RE, Haggblom CI, Karlseder J. Defective telomere lagging strand synthesis in cells lacking WRN helicase activity. Science. 2004;306:1951–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1103619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang S, Multani AS, Cabrera NG, Naylor ML, Laud P, Lombard D, Pathak S, Guarente L, DePinho RA. Essential role of limiting telomeres in the pathogenesis of Werner syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:877–82. doi: 10.1038/ng1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crabbe L, Jauch A, Naeger CM, Holtgreve-Grez H, Karlseder J. Telomere dysfunction as a cause of genomic instability in Werner syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2205–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609410104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hofer AC, Tran RT, Aziz OZ, Wright W, Novelli G, Shay J, Lewis M. Shared phenotypes among segmental progeroid syndromes suggest underlying pathways of aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:10–20. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kudlow BA, Stanfel MN, Burtner CR, Johnston ED, Kennedy BK. Suppression of proliferative defects associated with processing-defective lamin A mutants by hTERT or inactivation of p53. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5238–48. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.d’Adda di Fagagna F, Reaper PM, Clay-Farrace L, Fiegler H, Carr P, Von Zglinicki T, Saretzki G, Carter NP, Jackson SP. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature. 2003;426:194–8. doi: 10.1038/nature02118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hao LY, Strong MA, Greider CW. Phosphorylation of H2AX at short telomeres in T cells and fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45148–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herbig U, Jobling WA, Chen BP, Chen DJ, Sedivy JM. Telomere shortening triggers senescence of human cells through a pathway involving ATM, p53, and p21(CIP1), but not p16(INK4a) Mol Cell. 2004;14:501–13. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takai H, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. DNA damage foci at dysfunctional telomeres. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1549–56. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herbig U, Ferreira M, Condel L, Carey D, Sedivy JM. Cellular senescence in aging primates. Science. 2006;311:1257. doi: 10.1126/science.1122446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeyapalan JC, Ferreira M, Sedivy JM, Herbig U. Accumulation of senescent cells in mitotic tissue of aging primates. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finkel T, Serrano M, Blasco MA. The common biology of cancer and ageing. Nature. 2007;448:767–74. doi: 10.1038/nature05985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pyle AM. Translocation and unwinding mechanisms of RNA and DNA helicases. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:317–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singleton MR, Dillingham MS, Wigley DB. Structure and mechanism of helicases and nucleic acid translocases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:23–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052305.115300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu L, Chan KL, Ralf C, Bernstein DA, Garcia PL, Bohr VA, Vindigni A, Janscak P, Keck JL, Hickson ID. The HRDC domain of BLM is required for the dissolution of double Holliday junctions. Embo J. 2005;24:2679–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bernstein DA, Keck JL. Conferring substrate specificity to DNA helicases: role of the RecQ HRDC domain. Structure. 2005;13:1173–82. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ouyang KJ, Woo LL, Ellis NA. Homologous recombination and maintenance of genome integrity: cancer and aging through the prism of human RecQ helicases. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:425–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Venteicher AS, Meng Z, Mason PJ, Veenstra TD, Artandi SE. Identification of ATPases pontin and reptin as telomerase components essential for holoenzyme assembly. Cell. 2008;132:945–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Makovets S, Herskowitz I, Blackburn EH. Anatomy and dynamics of DNA replication fork movement in yeast telomeric regions. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4019–31. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.4019-4031.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ivessa AS, Zhou JQ, Schulz VP, Monson EK, Zakian VA. Saccharomyces Rrm3p, a 5′ to 3′ DNA helicase that promotes replication fork progression through telomeric and subtelomeric DNA. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1383–96. doi: 10.1101/gad.982902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gilson E, Geli V. How telomeres are replicated. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:825–38. doi: 10.1038/nrm2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller KM, Rog O, Cooper JP. Semi-conservative DNA replication through telomeres requires Taz1. Nature. 2006;440:824–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ohki R, Ishikawa F. Telomere-bound TRF1 and TRF2 stall the replication fork at telomeric repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1627–37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wellinger RJ, Wolf AJ, Zakian VA. Structural and temporal analysis of telomere replication in yeast. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1993;58:725–32. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1993.058.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deng Z, Lezina L, Chen CJ, Shtivelband S, So W, Lieberman PM. Telomeric proteins regulate episomal maintenance of Epstein-Barr virus origin of plasmid replication. Mol Cell. 2002;9:493–503. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heller RC, Marians KJ. Replisome assembly and the direct restart of stalled replication forks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:932–43. doi: 10.1038/nrm2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sidorova JM. Roles of the Werner syndrome RecQ helicase in DNA replication. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:1776–86. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davies SL, North PS, Hickson ID. Role for BLM in replication-fork restart and suppression of origin firing after replicative stress. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:677–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zou H, Rothstein R. Holliday junctions accumulate in replication mutants via a RecA homolog- independent mechanism. Cell. 1997;90:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Osman F, Whitby MC. Exploring the roles of Mus81-Emel/Mms4 at perturbed replication forks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1004–17. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bachrati CZ, Hickson ID. RecQ helicases: guardian angels of the DNA replication fork. Chromosoma. 2008;117:219–33. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Larrivee M, LeBel C, Wellinger RJ. The generation of proper constitutive G-tails on yeast telomeres is dependent on the MRX complex. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1391–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.1199404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chai W, Sfeir AJ, Hoshiyama H, Shay JW, Wright WE. The involvement of the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex in the generation of G-overhangs at human telomeres. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:225–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dionne I, Wellinger RJ. Cell cycle-regulated generation of single-stranded G-rich DNA in the absence of telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13902–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hemann MT, Greider CW. G-strand overhangs on telomeres in telomerase-deficient mouse cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3964–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.20.3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Budd ME, Reis CC, Smith S, Myung K, Campbell JL. Evidence suggesting that Pif1 helicase functions in DNA replication with the Dna2 helicase/nuclease and DNA polymerase delta. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2490–500. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2490-2500.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boule JB, Vega LR, Zakian VA. The yeast Pif1p helicase removes telomerase from telomeric DNA. Nature. 2005;438:57–61. doi: 10.1038/nature04091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gros J, Guedin A, Mergny JL, Lacroix L. G-Quadruplex formation interferes with P1 helix formation in the RNA component of telomerase hTERC. Chembiochem. 2008;9:2075–9. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tham WH, Zakian VA. Transcriptional silencing at Saccharomyces telomeres: implications for other organisms. Oncogene. 2002;21:512–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Luke B, Panza A, Redon S, Iglesias N, Li Z, Lingner J. The Rat1p 5′ to 3′ exonuclease degrades telomeric repeat-containing RNA and promotes telomere elongation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2008;32:465–77. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Azzalin CM, Reichenbach P, Khoriauli L, Giulotto E, Lingner J. Telomeric repeat containing RNA and RNA surveillance factors at mammalian chromosome ends. Science. 2007;318:798–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1147182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schoeftner S, Blasco MA. Developmentally regulated transcription of mammalian telomeres by DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:228–36. doi: 10.1038/ncb1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Duquette ML, Handa P, Vincent JA, Taylor AF, Maizels N. Intracellular transcription of G-rich DNAs induces formation of G-loops, novel structures containing G4 DNA. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1618–29. doi: 10.1101/gad.1200804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xu Y, Kimura T, Komiyama M. Human telomere RNA and DNA form an intermolecular G-quadruplex. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf) 2008:169–70. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrn086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lew JE, Enomoto S, Berman J. Telomere length regulation and telomeric chromatin require the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6121–30. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.6121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zubko MK, Guillard S, Lydall D. Exo1 and Rad24 differentially regulate generation of ssDNA at telomeres of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cdc13-l mutants. Genetics. 2004;168:103–15. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hackett JA, Greider CW. End resection initiates genomic instability in the absence of telomerase. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8450–61. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8450-8461.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maringele L, Lydall D. EX01 plays a role in generating type I and type II survivors in budding yeast. Genetics. 2004;166:1641–9. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.4.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schaetzlein S, Kodandaramireddy NR, Ju Z, Lechel A, Stepczynska A, Lilli DR, Clark AB, Rudolph C, Kuhnel F, Wei K, Schlegelberger B, Schirmacher P, Kunkel TA, Greenberg RA, Edelmann W, Rudolph KL. Exonuclease-1 deletion impairs DNA damage signaling and prolongs lifespan of telomere-dysfunctional mice. Cell. 2007;130:863–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gravel S, Chapman JR, Magill C, Jackson SP. DNA helicases Sgs1 and BLM promote DNA double-strand break resection. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2767–72. doi: 10.1101/gad.503108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature. 2008;455:770–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhu Z, Chung WH, Shim EY, Lee SE, Ira G. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell. 2008;134:981–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Maser RS, DePinho RA. Connecting chromosomes, crisis, and cancer. Science. 2002;297:565–9. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5581.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.De Lange T. Telomere-related genome instability in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:197–204. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang X, Baumann P. Chromosome fusions following telomere loss are mediated by single-strand annealing. Mol Cell. 2008;31:463–73. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Paques F, Haber JE. Two pathways for removal of nonhomologous DNA ends during double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6765–71. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cesare AJ, Reddel RR. Telomere uncapping and alternative lengthening of telomeres. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.McEachern MJ, Haber JE. Break-Induced Replication and Recombinational Telomere Elongation in Yeast. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006 doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lundblad V, Blackburn EH. An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1- senescence. Cell. 1993;73:347–60. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90234-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu L, Bailey SM, Okuka M, Munoz P, Li C, Zhou L, Wu C, Czerwiec E, Sandler L, Seyfang A, Blasco MA, Keefe DL. Telomere lengthening early in development. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1436–41. doi: 10.1038/ncb1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lee J, Kozak M, Martin J, Pennock E, Johnson FB. Evidence that a RecQ helicase slows senescence by resolving recombining telomeres. PLOS Biology. 2007;5:e160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]