Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To systematically review evidence of the treatment benefits of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for symptoms related to severe premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

DATA SOURCES

We conducted electronic database searches of MEDLINE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Embase, PsycINFO, and Cinahl through March 2007, and hand-searched reference lists and pertinent journals.

METHODS OF STUDY SELECTION

Studies included in the review were double-blind, randomized, controlled trials comparing an SSRI with placebo that reported a change in a validated score of premenstrual symptomatology. Studies had to report follow-up for any duration longer than one menstrual cycle among premenopausal women who met clinical diagnostic criteria for PMS or premenstrual dysphoric disorder. From 2,132 citations identified, we pooled results from 29 studies (in 19 citations) using random-effects meta-analyses and present results as odds ratios (ORs).

TABULATION, INTEGRATION, AND RESULTS

Our metaanalysis, which included 2,964 women, demonstrates that SSRIs are effective for treating PMS and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (OR 0.40, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.31-0.51). Intermittent dosing regimens were found to be less effective (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.45-0.68) than continuous dosing regimens (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.18-0.42). No SSRI was demonstrably better than another. The choice of outcome measurement instrument was associated with effect size estimates. The overall effect size is smaller than reported previously.

CONCLUSION

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were found to be effective in treating premenstrual symptoms, with continuous dosing regimens favored for effectiveness.

Moderate to severe premenstrual syndrome, which may include clinically relevant physical, behavioral, and emotional symptoms, affects almost 18% of women of reproductive age.1 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are currently considered the most effective pharmacologic class for the treatment of symptoms related to severe premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and its most intense form, premenstrual dysphoric disorder.2,3 Evidence implicates the serotonergic system in particular in the pathogenesis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder, which is thought to be associated with symptoms such as irritability, depressed mood, and carbohydrate craving.4

Despite the conduct of systematic reviews supporting SSRI efficacy,5,6 sources of heterogeneity (ie, clinically meaningful differences) between studies have not been elucidated in prior meta-analyses. Since the publication of the last major review by the Cochrane Collaboration in 2002, numerous additional studies have been published on the topic, which creates an opportunity to explore such differences further. Specifically, we conducted a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis to explore the effect of using different outcome measurement instruments, various SSRI types, and administration schedules.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

With the assistance of a professional librarian and using validated search methods,7 studies and review articles relating SSRIs and PMS, premenstrual dysphoria, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or late luteal phase dysphoric disorder were identified in six databases: MEDLINE, Web of Science, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews/Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Embase, PsycINFO, and Cinahl. Among others, the search terms included SSRI, PMS, PMD (premenstrual dysphoria), PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder), LLPDD (late luteal phase dysphoric disorder), and the generic names of SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline).

Each electronic database was searched from its initial inclusion date to March 2007. Definitions of PMS and premenstrual dysphoric disorder have changed over time with the most severe form of PMS redefined as premenstrual dysphoric disorder. The Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition 8 classification of premenstrual dysphoric disorder is a “depressive disorder not otherwise specified” that emphasizes emotional and cognitive-behavioral symptoms, with at least five of 11 prespecified symptoms that are limited to the luteal phase for at least two consecutive menstrual cycles present for a diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

Reference lists from retrieved reviews, meta-analyses, and sentinel trials were searched recursively to identify any additional trials. The tables of contents from the top five journals that published pertinent trials (Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, American Journal of Psychiatry, Psychoneuroendocrinology, and Biological Psychiatry) were handsearched over the past 5 years to identify additional studies. Appendix 1 (online at www.greenjournal.org/cgi/content/full/111/5/1175/DC1) contains the full search strategy.

Study Selection

To be considered for this systematic review, studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) the study had to have an English title; 2) the study was a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of an SSRI compared with placebo; 3) the study examined an SSRI at any dose and any dosing regimen for more than one menstrual cycle compared with placebo; 4) the study population included women of any age who met the diagnostic criteria for PMS, premenstrual dysphoria, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or late luteal phase dysphoric disorder; 5) diagnosis of PMS, premenstrual dysphoria, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or late luteal phase dysphoric disorder must have been confirmed by a general practitioner, hospital clinician, or other health care professional before a woman’s inclusion in the trial; 6) the study had to report change in overall premenstrual symptomatology as measured by a validated severity score (eg, Daily Record of Severity of Problems, Calendar of Premenstrual Experiences, etc.) We excluded studies that evaluated non-serotonin-specific inhibitors and crossover trials that did not report results at the end of the first phase of treatment.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two investigators independently reviewed all titles and studies included in meta-analyses. The full text of the citation was retrieved for any title with no abstract available. We excluded editorials, letters, and results not presented in peer-reviewed journals. Authors of included studies were contacted to identify unpublished data. All outcomes were dual-abstracted independently using standardized evidence tables, with discrepancies resolved by consensus. Appendix 2 (available online at www.greenjournal.org/cgi/content/full/111/5/1175/DC1) summarizes the findings of the literature search. A Jadad score9 was calculated for all included studies. Studies are scored on a 0-5 scale with higher scores assigned to higher quality studies, and sensitivity analyses based on quality score and individual quality items were conducted.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

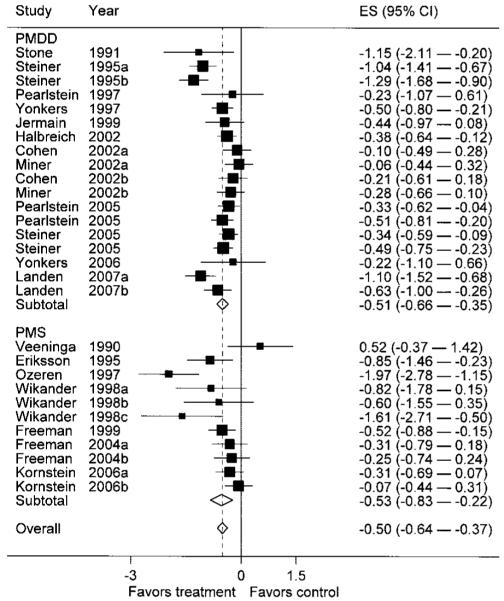

We conducted meta-analyses of studies on the use of SSRIs for the treatment of PMS and premenstrual dysphoric disorder with the methods of DerSimonian and Laird10 to compute point estimates and 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were conducted with the Stata 9.2 statistical software package (Stata-Corp LP, College Station, TX) using the “metan” command. Both random effects and fixed effects models were computed, but with no significant differences between the two, only random effects results are presented. A priori defined subgroup analyses by dosing regimen (intermittent compared with continuous, symptomatic dosing compared with standard dosing), SSRI type, and year of publication were conducted. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Q test, I2, and further evaluated with exploratory meta-regression.11,12 Publication bias was assessed by the methods of Egger with results presented in Figure 1.13

Fig. 1.

Filled funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence limits for publication bias.

Shah. SSRIs for PMS and Premenstrual Dysphoria. Obstet Gynecol 2008.

The included studies reported a variety of outcome assessments of overall symptoms. To calculate a pooled effect size, we used the standardized mean difference and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) as the effect measure, as was done in prior meta-analyses of this topic.5,6 The standardized mean difference was calculated based on reported or calculated (ie, from reported change scores) final endpoint values of the symptom score; standardized mean differences were converted to odds ratios using validated techniques for ease of interpretation.14

RESULTS

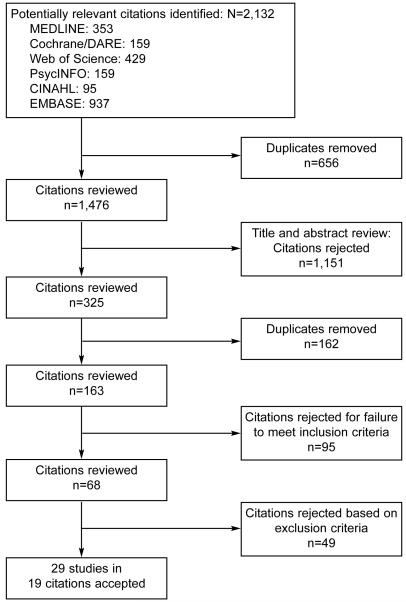

The search resulted in a sample of 2,132 titles (353 MEDLINE, 429 Web of Science, 159 Cochrane Database of Systematic/Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), 937 Embase, 159 PsycINFO, and 95 Cinahl). From these citations, we identified 325 potential controlled trials with data on the association between SSRIs and PMS, premenstrual dysphoria, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. Crossover trials were excluded for not presenting data at the end of the first phase. After excluding duplicates, we retrieved 163 articles for full-text review, of which 19 were included in the final meta-analysis. For data sets that were presented in multiple publications, we selected those with the most up-to-date results, longest follow-up, or most pertinent outcomes. All data elements relative to the meta-analyses had two reviewers who came to consensus on all items. See Appendix 2 (available online at www.greenjournal.org/cgi/content/full/111/5/1175/DC2) for a graphic of trial flow. Studies that are included in the meta-analyses are listed in Table 1. Other studies with either a drug and/or outcome of interest that did not meet inclusion criteria are listed in Appendix 3 (available online at www.greenjournal.org/cgi/content/full/111/5/1175/DC3), along with reasons for their exclusion. Nonparametric tests for publication bias resulted in no studies being trimmed or filled (Fig. 1), suggesting a low likelihood of important studies that were missed.

Table 1. Randomized Controlled Trials Included in Meta-Analysis.

| Author | Design | Country | Study Sites | Sample Size | Drug | Dose | Dosing Regimen | Jadad Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veeninga 199015 | Parallel | Netherlands | 1 | 20 | Fluvoxamine | 50-150 mg | Continuous | 3 |

| Stone 199123 | Parallel | USA | 1 | 20 | Fluoxetine | 20 mg | Continuous | 3 |

| Eriksson 199517 | Parallel | Sweden | 1 | 44 | Paroxetine | 10-30 mg | Continuous | 4 |

| Ozeren 199722 | Parallel | Turkey | 1 | 35 | Fluoxetine | 20 mg | Continuous | 3 |

| Pearlstein 199726 | Parallel | USA | 2 | 22 | Fluoxetine | 20 mg | Continuous | 3 |

| Yonkers 199725 | Parallel | USA | 1 | 187 | Sertraline | 50-150 mg | Continuous | 5 |

| Freeman 199918 | Parallel | USA | 1 | 117 | Sertraline | 50-150 mg | Continuous | 5 |

| Jermain 199921 | Crossover | USA | 1 | 57 | Sertraline | 50-100 mg | Intermittent | 3 |

| Halbreich 200220 | Parallel | USA, Canada | 14 | 229 | Sertraline | 50-100 mg | Intermittent | 5 |

| Steiner 1995a27 | Parallel | Canada | 7 | 144 | Fluoxetine | 20 mg | Continuous | 3 |

| Steiner 1995b27 | Parallel | Canada | 7 | 133 | Fluoxetine | 60 mg | Continuous | 3 |

| Wikander 1998a24 | Parallel | Sweden | 1 | 23 | Citalopram | 20 mg | Continuous | 4 |

| Wikander 1998b24 | Parallel | Sweden | 1 | 23 | Citalopram | 5-20 mg | Continuous | 4 |

| Wikander 1998c24 | Parallel | Sweden | 1 | 23 | Citalopram | 20 mg | Intermittent | 4 |

| Cohen 2002a28 | Parallel | USA | 20 | 117 | Fluoxetine | 10 mg | Intermittent | 5 |

| Cohen 2002b28 | Parallel | USA | 20 | 109 | Fluoxetine | 20 mg | Intermittent | 5 |

| Miner 2002a29 | Parallel | USA | 30 | 123 | Fluoxetine | 90 mg | Intermittent | 4 |

| Miner 2002b29 | Parallel | USA | 30 | 124 | Fluoxetine | 90 mg | Intermittent | 4 |

| Freeman 2004a19 | Parallel | USA | 1 | 73 | Sertraline | 50-100 mg | Continuous | 5 |

| Freeman 2004b19 | Parallel | USA | 1 | 70 | Sertraline | 50-100 mg | Intermittent | 5 |

| Pearlstein 2005a30 | Parallel | USA, Canada | 47 | 187 | Paroxetine | 12.5 mg | Continuous | 5 |

| Pearlstein 2005b30 | Parallel | USA, Canada | 47 | 173 | Paroxetine | 25 mg | Continuous | 5 |

| Steiner 2005a31 | Parallel | Canada | 53 | 249 | Paroxetine | 12.5 mg | Intermittent | 3 |

| Steiner 2005b31 | Parallel | Canada | 53 | 235 | Paroxetine | 25 mg | Intermittent | 3 |

| Kornstein 2006a32 | Parallel | USA | 22 | 120 | Sertraline | 25 mg | Intermittent | 4 |

| Kornstein 2006b32 | Parallel | USA | 22 | 120 | Sertraline | 50 mg | Intermittent | 4 |

| Yonkers 200633 | Crossover | USA | NR | 20 | Paroxetine | 25 mg | Symptom Onset | 4 |

| Landen 2007a16 | Parallel | Sweden | 4 | 83 | Paroxetine | 20 mg | Intermittent | 5 |

| Landen 2007b16 | Parallel | Sweden | 4 | 84 | Paroxetine | 20 mg | Continuous | 5 |

NR, not reported.

Heterogeneity I2=66%.

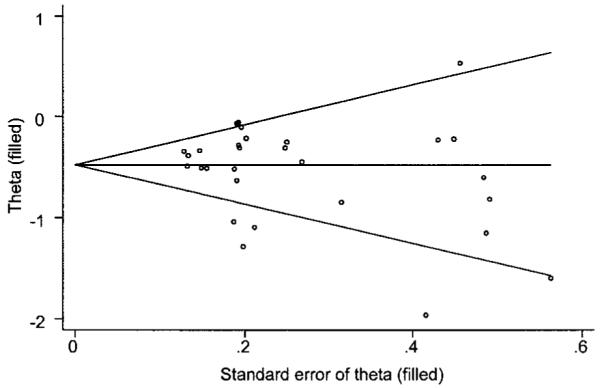

Twenty-nine randomized controlled trials (defined as a comparison between an SSRI and placebo for the treatment of PMS/premenstrual dysphoric disorder) in 19 published manuscripts met all inclusion criteria. Meta-analysis of these 29 studies, including 2,964 women, results in an overall odds ratio (OR) of 0.40 (95% CI 0.31-0.51), suggesting a strong association between the use of SSRIs and a reduction in PMS/premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptoms. Heterogeneity (I2=66%) was examined in subsequent meta-regression. A summary of the treatment effect point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for each study included in the meta-analysis is listed in Table 3. A forest plot for the overall treatment effect is shown in Figure 2.

Table 3. Odds Ratios For Primary Outcome Measurement Instruments.

| Instrument | Study | Odds Ratio | 95% Lower CI | 95% Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPE* | Jermain (1999) | 0.45 | 0.17 | 1.16 |

| Ozeren (1997) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.12 | |

| Pooled | 0.12 | 0.01 | 1.78 | |

| DAF | Pearlstein (1997) | 0.66 | 0.14 | 3.04 |

| Pooled | - | - | - | |

| DRSP | Halbreich (2002) | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.80 |

| Yonkers (1997) | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.68 | |

| Miner (2002a) | 0.90 | 0.45 | 1.79 | |

| Miner (2002b) | 0.60 | 0.30 | 1.20 | |

| Cohen (2002a) | 0.83 | 0.41 | 1.66 | |

| Cohen (2002b) | 0.68 | 0.33 | 1.39 | |

| Yonkers (2006) | 0.67 | 0.14 | 3.32 | |

| Pooled | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.75 | |

| DSR | Freeman (1999) | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.76 |

| Freeman (2004a) | 0.57 | 0.24 | 1.38 | |

| Freeman (2004b) | 0.64 | 0.26 | 1.55 | |

| Kornstein (2006a) | 0.57 | 0.29 | 1.14 | |

| Kornstein (2006b) | 0.88 | 0.45 | 1.74 | |

| Pooled | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.82 | |

| GAS | Stone (1991) | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.70 |

| Pooled | - | - | - | |

| Global Change | Wikander (1998b) | 0.34 | 0.06 | 1.88 |

| Wikander (1998a) | 0.23 | 0.04 | 1.30 | |

| Wikander (1998c) | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.40 | |

| Pooled | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.51 | |

| MDQ | Veeninga (1990) | 2.59 | 0.51 | 13.10 |

| Pooled | - | - | - | |

| VAS | Steiner (1995a) | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.29 |

| Steiner (1995b) | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.20 | |

| Eriksson (1995) | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.66 | |

| Pooled | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.21 | |

| VAS-Mood | Steiner (2005) | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.85 |

| Steiner (2005) | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.66 | |

| Pearlstein (2005) | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.92 | |

| Pearlstein (2005) | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.69 | |

| Landen (2007a) | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.29 | |

| Landen (2007b) | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.62 | |

| Pooled | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.54 |

CI, confidence interval; COPE, Calendar of Premenstrual Experiences; DAF, Daily Assessment Form; DRSP, Daily Record of Severity of Problems; DSR, Daily Symptom Rating; GAS, Global Assessment Scale; MDQ, Menstrual Distress Questionnaire; VAS, Visual Analog Scale.

Calendar of Premenstrual Experiences pooled effect size showed statistical heterogeneity (Q-test=9.45, P=.002, I2=89.4%); VAS-Mood pooled effect size showed statistical heterogeneity (Q-test=11.31, P=.05, I2=55.8%); all other instruments had nonsignificant heterogeneity (P>.20).

Fig. 2.

Pooling of 29 studies favors treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors over placebo control for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. The pooled effect size (standardized mean difference) of -0.50 (-0.64 to -0.37) corresponds to an odds ratio of 0.40 (95% CI 0.31-0.51). ES, effect size.

Shah. SSRIs for PMS and Premenstrual Dysphoria. Obstet Gynecol 2008.

We conducted meta-regression based on prespecified covariates and on an exploratory basis. Among the exploratory analyses, only the study country showed some evidence of a relationship to the effect size; however, sensitivity analysis excluding the one study conducted outside of North America/Europe showed no appreciable change in the pooled effect size in the meta-analysis. No other variables examined in exploratory analyses (including pharmaceutical sponsorship of the study)34 were found to be both significant and clinically relevant.

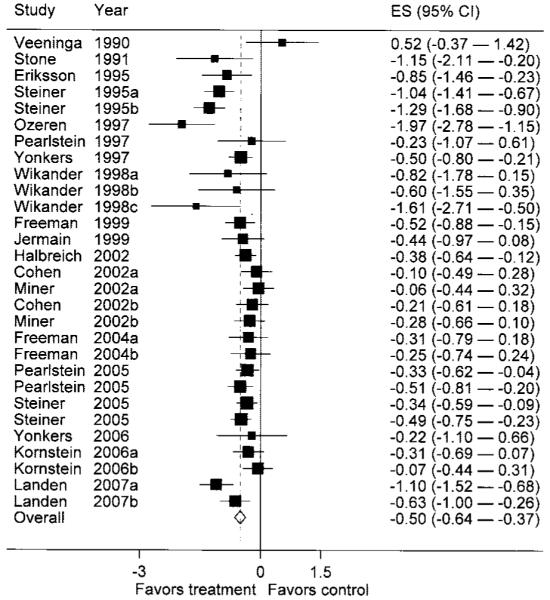

Some studies reported on outcomes related to PMS, the less severe version of the disorder compared with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. When results are stratified by PMS compared with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (Fig. 3), the pooled effect size for PMS is OR 0.38 (95% CI 0.22-0.66), whereas for premenstrual dysphoric disorder is OR 0.40 (95% CI 0.30-0.53). There is still significant within-strata heterogeneity (significant I2 of 67% for both PMS and premenstrual dysphoric disorder). Figure 3 also suggests that, with the exception of the studies by Veeninga15 and Landen,16 earlier studies tend to report a larger treatment effect for SSRIs in both PMS and premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

Fig. 3.

The pooled effect size (standardized mean difference) for studies of premenstrual syndrome is -0.53 (95% CI -0.83 to -0.23), which corresponds to an odds ratio of 0.38 (95% CI 0.22-0.66). The pooled effect size (standardized mean difference) for studies of premenstrual dysphoric disorder is -0.51 (95% CI -0.66 to -0.35), which corresponds to an odds ratio of 0.40 (95% CI 0.30-0.53). PMDD, premenstrual dysphoric disorder; PMS, premenstrual syndrome.

Shah. SSRIs for PMS and Premenstrual Dysphoria. Obstet Gynecol 2008.

Intermittent dosing studies17-25 yielded a significantly smaller estimate of the treatment effect size (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.45-0.68, I2=20%) than continuous dosing studies (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.18-0.42) with evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2=70%).

Eleven studies allowed participants to adjust the dose of study medication according to their symptoms.17-24 These “flexible” dosing strategies, however, do not conform to the traditional clinical definition of symptomatic dosing. In our analysis, only one study that met inclusion criteria allowed patients to initiate medication upon symptoms, hence we were unable to shed further light on this issue in a pooled analysis. The symptom-onset dosing study reported a smaller effect size (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.14-3.32) than either intermittent or continuous dosing studies; the wide confidence interval makes it difficult to generalize from this single study.

Fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine were the most common SSRIs studied for PMS/premenstrual dysphoric disorder. The relative effect sizes for these SSRIs are presented in Table 2. No significant differences in effect sizes were found, and all were associated with improved symptoms except for fluvoxamine, which has only one small trial that met inclusion criteria, with wide confidence intervals allowing for the possibility of benefit or no benefit. Further subgroup analyses examining drug by dose, dosing regimen, or duration were not conducted, because there were too few studies to provide a comprehensive assessment of these issues.

Table 2. Odds Ratios By Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor.

| Drug | Number of Studies | Pooled N | Odds Ratio | 95% Lower CI | 95% Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | 3 | 69 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.51 |

| Fluoxetine | 9 | 827 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.62 |

| Fluvoxamine | 1 | 20 | 2.59 | 0.51 | 13.10 |

| Paroxetine | 8 | 1,075 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.52 |

| Sertraline | 8 | 973 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.65 |

CI, confidence interval.

Table 3 lists the pooled treatment effect and odds ratios for the primary outcome assessment instrument used in each study. Eighteen studies used an ordinal scale. The Daily Record of Severity of Problems, used in seven studies, was the most commonly used instrument. A total of nine studies used a visual analog scale (VAS) to assess the primary outcome; the VAS-Mood was used in six of the studies and the VAS-Total in the remaining three studies. The pooled effect size for studies using the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.46-0.75) is smaller than the pooled effect size for studies using the VAS-Mood (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.27-0.54); however, the three studies using the VAS-Total report a markedly larger pooled effect size (OR 0.13, 95% CI: 0.09, 0.21) than either the Daily Record of Severity of Problems or VAS-Mood. Meta-regression results suggest that the choice of instrument may be associated with the pooled effect size. Stratification by Daily Record of Severity of Problems, VAS-Mood, and VAS-Total eliminates residual statistical evidence of heterogeneity.

All included studies received a Jadad score of 3 or higher. Exploratory meta-regression indicated only one component of the Jadad score was associated with the pooled effect size: whether the study described the method of randomization. Studies that failed to describe the method of randomization had a larger pooled effect size (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.16-0.44) and greater heterogeneity (I2=73%) than studies that included a description of the method of randomization (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.38-0.61; I2=43%). Because all studies had a Jadad score of 3 or greater, we did not exclude any studies in sensitivity analyses.

CONCLUSION

The clinical implications of this report are threefold: 1) SSRIs (specifically, citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline) are effective for treatment of PMS/premenstrual dysphoric disorder, 2) Continuous dosing regimens may be more effective than intermittent dosing regimens, and 3) The effect size observed, although significant, is smaller than previously reported (see below). We found a strong association between the use of SSRIs and symptomatic relief for PMS/premenstrual dysphoric disorder (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.31-0.51). Whereas overall pooled results demonstrated evidence of statistical heterogeneity, pre-specified subgroup analyses by medication, indication (PMS or premenstrual dysphoric disorder), and dosing regimen (intermittent or continuous) continued to show robust associations.

We found that earlier studies demonstrated a larger association between SSRIs and symptomatic relief than more recent studies. This may be attributable to several factors. Secular trends, with improvements over time in ancillary treatments or care, may explain the decreasing effect size seen in recent studies (Table 1). A better understanding of disease and improved exclusion of depression and other SSRI-responsive states could result in the smaller effect size observed; earlier studies tended to report on PMS, whereas more recent studies tended to report on premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Also, the increasing availability of SSRI treatment to women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder has made it difficult to recruit participants for premenstrual dysphoric disorder studies with a likely result of subjects who are less responsive. Finally, generally lower doses used in later studies might correspond to the treatment benefit seen, but there are too few studies to examine this further.

Continuous dosing had a larger effect size (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.18-0.42) than intermittent dosing (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.45-0.68). This finding is contrary to recent belief and practice,5,35-37 and should be considered by clinicians initiating treatment, given the potential magnitude of the effect size difference observed. Head-to-head trials of continuous compared with intermittent dosing strategies are needed to conclusively examine the issue.

Of the five SSRIs included in this report (citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline), all were significantly associated with improved symptoms with the exception of fluvoxamine (OR 2.59, 95% CI 0.51-13.10). This last SSRI was studied in only one small trial included in our systematic review, and with its wide confidence intervals has insufficient evidence to exclude the possibility of benefit. There were too few studies to conduct stratified analyses by drug compared with dose compared with regimen (intermittent compared with continuous), hence any direct comparisons of efficacy between SSRIs are premature and require additional studies or head-to-head randomized trials.

In a meta-analysis that included randomized controlled trials conducted through 2000, the authors of the Cochrane report pooled 13 studies and reported a standardized mean difference of -0.75 (95% CI -0.98 to -0.51), which corresponds to an OR of 0.22 (95% CI 0.13-0.37) favoring SSRIs over placebo for the reduction of symptoms related to PMS/premenstrual dysphoric disorder.5,6 We pooled the results from 29 studies including over 2,900 women and found a more moderate, albeit significant effect size (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.31-0.51). Furthermore, the 16 additional studies we identified allowed a priori subgroup analyses, which addressed important clinical issues.

As with any meta-analysis, the strength of the findings reflects the quality of the underlying data, potential for publication bias, and heterogeneity. All included studies had a Jadad quality score of 3 or more. Sensitivity analyses by quality score suggests that lower-quality studies, as defined by whether authors described the method of randomization, tend to overestimate benefits of SSRIs. We contacted study authors for additional reports and also found no evidence of publication bias using a funnel plot, suggesting that important studies which might materially affect conclusions have not been missed. Although statistical heterogeneity was found in some of our analyses, we attempted to address these instances by conducting meta-regression and sensitivity analyses whenever possible.

Future research should focus on the relative effect size observed with different SSRIs (perhaps with head-to-head trials), a better understanding of duration of treatment required, the relative effects on behavioral compared with psychological compared with physical symptoms, and a comprehensive look at adverse effects.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Shah has received unrestricted research grants from GlaxoSmithKline (Philadelphia, PA), Novartis (Basel, Switzerland), AstraZeneca (Wilmington, DE), Roche (Basel, Switzerland), Berlex (Montville, NJ), and Pfizer (New York, NY) and has been a consultant for Cerner Health Insights (Los Angeles, CA) and LifeTech Research (Baltimore MD). Dr. Borenstein has received research grants and a served as a consultant for Berlex. The other authors do not have any potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supported by grant number 5305535 from Berlex Laboratories, Inc. (Montville, NJ) and the New York University School of Medicine.

Appendix 1

Medline Search Strategy

| 1 | Premenstrual Syndrome/ |

| 2 | (premenstrual syndrome$ or pms).mp. |

| 3 | (premenstrual dysphoric disorder or pmdd).mp. |

| 4 | menstrual cycle/ or fertile period/ or follicular phase/ or luteal phase/ or menstruation/ or ovulation/ |

| 5 | exp Ovary/ |

| 6 | (menstru$ w5 cycle or fertile w5 period$ or follicular w5 phase or luteal w5 phase or ovulat$ or ovary or ovarian or ovaries).mp. |

| 7 | llpdd.mp. |

| 8 | premenstrual tension syndrome.mp. |

| 9 | pmts.mp. |

| 10 | menstrual mood disorder$.mp. |

| 11 | premenstrual mastalgia.mp. |

| 12 | cyclical mastalgia.mp. |

| 13 | premenstrual depression.mp. |

| 14 | premenstrual tension.mp. |

| 15 | mastalgia$.mp. |

| 16 | or/1-15 |

| 17 | randomized controlled trial.pt. |

| 18 | controlled clinical trial.pt. |

| 19 | randomized controlled trials/ |

| 20 | random allocation/ |

| 21 | double blind method/ |

| 22 | single blind method/ |

| 23 | or/17-22 |

| 24 | animal/ not human/ |

| 25 | 23 not 24 |

| 26 | clinical trial.pt. |

| 27 | exp clinical trials/ |

| 28 | (clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab. |

| 29 | ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. |

| 30 | placebos/ |

| 31 | placebo$.ti,ab. |

| 32 | random$.ti,ab. |

| 33 | research design/ |

| 34 | or/26-33 |

| 35 | 34 not 24 |

| 36 | 35 not 25 |

| 37 | comparative study/ |

| 38 | exp evaluation studies/ |

| 39 | follow up studies/ |

| 40 | prospective studies/ |

| 41 | (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).ti,ab. |

| 42 | or/37-41 |

| 43 | 42 not 24 |

| 44 | 43 not (25 or 36) |

| 45 | 25 or 36 or 44 |

| 46 | exp Serotonin Uptake Inhibitors/ |

| 47 | (ssri$ or serotonin uptake inhibitor$ or serotonin reuptake inhibitor$ or 5-ht uptake or 5ht uptake or 5 ht uptake).mp. |

| 48 | Fluoxetine/ |

| 49 | (fluoxetine or fluoxetin or prozac or sarafem or fluctin or fluctine or flunirin or fluoxifar or lovan or prosac or prozamin).mp. |

| 50 | 48 or 49 |

| 51 | or/46-49 |

| 52 | (citalopram or cytalopram or escitalopram or celexa or cipramil or elopram or nitalapram or sepram or seropram).mp. |

| 53 | dapoxetine.mp. |

| 54 | dapoxetine/ |

| 55 | (citalopram or cytalopram or escitalopram or celexa or cipramil or elopram or nitalapram or sepram or seropram or cipralex or lexapro).mp. |

| 56 | (femoxetine or malexil).mp. |

| 57 | (fluvoxamine or desiflu or dumirox or faverin or fevarin or floxyfral or fluvoxadura or fluvoxamin or luvox or fluoxamine or fluroxamine).mp. |

| 58 | depromel.mp. |

| 59 | ifoxetine.mp. |

| 60 | litoxetine.mp. |

| 61 | Paroxetine/ |

| 62 | (paroxetine or aropax or paxil or seroxat or deroxat or dexorat or motivan or tagonis).mp. |

| 63 | Sertraline/ |

| 64 | (sertraline or altruline or aremis or besitran or gladem or lustral or sealdin or zoloft or serad or serlain or tresleen).mp. |

| 65 | Zimeldine/ |

| 66 | (zimeldine or zimelidine or zelmid or zimelidin).mp. |

| 67 | (normud or zelmid or zelmidine or zimelidine).mp. |

| 68 | Citalopram/ |

| 69 | cericlamine.mp. |

| 70 | cericlamine/ |

| 71 | fluvoxamine/ |

| 72 | or/46-71 |

| 73 | 16 and 45 and 72 |

Appendix 2

Appendix 2.

Flow diagram of search and selection processes. Online appendix to Shah N, Jones JB, Aperi J, Shemtov R, Karne A, Borenstein J. Selective reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:1175-82.

Appendix 3

Studies Excluded From the Meta-Analysis

| Author | Year | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Atmaca | 2003 | Not placebo-controlled |

| Brandenburg | 1993 | Open trial |

| Brzezinski | 1990 | Not an SSRI |

| Cohen | 1998 | Not an RCT |

| Cohen | 2004a | Preliminary report of Pearlstein 2005 |

| Cohen | 2004b | Open trial |

| Daamen | 1992 | Not an RCT |

| De la Gandara | 1997 | Not placebo controlled |

| Diegoli | 1998 | Did not present data at end of first cross-over phase |

| Flores Ramos | 2003 | Not placebo controlled |

| Freeman | 1996 | Not placebo controlled |

| Freeman | 1999 | Not placebo controlled |

| Freeman | 2000 | Analysis of previously reported trial |

| Freeman | 2001a | Analysis of previously reported trial |

| Freeman | 2001b | Not an SSRI |

| Freeman | 2002 | Not an SSRI |

| Freeman | 2004 | Not placebo controlled |

| Freeman | 2005 | Not placebo controlled |

| Halbreich | 1997 | Did not present data at end of first cross-over phase |

| Hunter | 2002a | Not SSRI vs placebo |

| Hunter | 2002b | Not SSRI vs placebo |

| Landen | 2001 | Not an SSRI |

| Martignoni | 1997 | Not an RCT |

| Menkes | 1992 | Included with Menkes 1993 |

| Menkes | 1993 | Did not present data at end of first cross-over phase |

| Metz | 1990 | Case report |

| Pearlstein | 2000 | Analysis of previously reported trial |

| Pies | 1990 | Case report |

| Prior | 1995 | Not an RCT |

| Ramos | 2003 | Not placebo controlled |

| Rickels | 1990 | Not a randomized study |

| Roca | 2002 | Not an SSRI |

| Steinberg | 1999 | Not an SSRI |

| Steiner | 1997a | Case series |

| Steiner | 1997b | Analysis of previously reported trial |

| Steiner | 2001 | Analysis of previously reported trial |

| Steiner | 2005 | Analysis of previously reported trial |

| Stenchever | 2003 | Not an RCT |

| Stewart | 1994 | Did not evaluate PMS/PMDD symptomatology |

| Su | 1997 | Did not present data at end of first cross-over phase |

| Sundblad | 1993a | Not an SSRI |

| Sundblad | 1993b | Not an SSRI |

| Tamayo | 2004 | Not an RCT |

| Wood | 1992 | Did not present data at end of first cross-over phase |

| Yonkers | 1996a | Not placebo controlled |

| Yonkers | 1996b | Preliminary report of included study |

| Yonkers | 2003 | Not an RCT |

| Yonkers | 2005 | Evaluation of previous study |

| Young | 1998 | Did not present data at end of first cross-over phase |

SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; RCT, randomized controlled trial; PMS, premenstrual syndrome; PMDD, premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

Footnotes

Presented as a poster at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in Toronto, Canada, April 25-27, 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Halbreich U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T, Kahn LS. The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD) Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(suppl):1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapkin AJ. New treatment approaches for premenstrual disorders. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:S480–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steiner M, Pearlstein T, Cohen LS, Endicott J, Kornstein SG, Roberts C, et al. Expert guidelines for the treatment of severe PMS, PMDD, and comorbidities: the role of SSRIs. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:57–69. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue Y, Terao T, Iwata N, Okamoto K, Kojima H, Okamoto T, et al. Fluctuating serotonergic function in premenstrual dysphoric disorder and premenstrual syndrome: findings from neuroendocrine challenge tests. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:213–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0607-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimmock PW, Wyatt KM, Jones PW, O’Brien PM. Efficacy of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Lancet. 2000;356:1131–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, O’Brien PM. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2002;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001396. Art No.: CD001396. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD001396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickersin K, Manheimer E, Wieland S, Robinson KA, Lefebvre C, McDonald S. Development of the Cochrane Collaboration’s CENTRAL Register of controlled clinical trials. Eval Health Prof. 2002;25:38–64. doi: 10.1177/016327870202500104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington (DC): 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:820–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Altman DG, editors. Systematic reviews in health care. 2nd ed. BMJ Publishing Group; London (UK): 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2000;19:3127–31. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3127::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veeninga AT, Westenberg HG, Weusten JT. Fluvoxamine in the treatment of menstrually related mood disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990;102:414–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02244113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landen M, Nissbrandt H, Allgulander C, Sorvik K, Ysander C, Eriksson E. Placebo-controlled trial comparing intermittent and continuous paroxetine in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:153–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eriksson E, Hedberg MA, Andersch B, Sundblad C. The serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetin is superior to the noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor maprotiline in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;12:167–76. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00076-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, Polansky M. Differential response to antidepressants in women with premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:932–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, Polansky M, Xiao S. Continuous or intermittent dosing with sertraline for patients with severe premenstrual syndrome or premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:343–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halbreich U, Bergeron R, Yonkers KA, Freeman E, Stout AL, Cohen L. Efficacy of intermittent, luteal phase sertraline treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:1219–29. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jermain DM, Preece CK, Sykes RL, Kuehl TJ, Sulak PJ. Luteal phase sertraline treatment for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:328–32. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozeren S, Corakci A, Yucesoy I, Mercan R, Erhan G. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;73:167–70. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(97)02741-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stone AB, Pearlstein TB, Brown WA. Fluoxetine in the treatment of late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:290–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wikander I, Sundblad C, Andersch B, Dagnell I, Zylberstein D, Bengtsson F, et al. Citalopram in premenstrual dysphoria: is intermittent treatment during luteal phases more effective than continuous medication throughout the menstrual cycle? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;18:390–8. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yonkers KA, Halbreich U, Freeman E, Brown C, Endicott J, Frank E, et al. Sertraline Premenstrual Dysphoric Collaborative Study Group Symptomatic improvement of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with sertraline treatment. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278:983–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearlstein TB, Stone AB, Lund SA, Scheft H, Zlotnick C, Brown WA. Comparison of fluoxetine, bupropion, and placebo in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:261–6. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199708000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steiner M, Steinberg S, Stewart D, Carter D, Berger C, Reid R, et al. Canadian Fluoxetine/Premenstrual Dysphoria Collaborative Study Group Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1529–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506083322301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen LS, Miner C, Brown EW, Freeman E, Halbreich U, Sundell K, et al. Premenstrual daily fluoxetine for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a placebo-controlled, clinical trial using computerized diaries. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:435–44. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miner C, Brown E, McCray S, Gonzales J, Wohlreich M. Weekly luteal-phase dosing with enteric-coated fluoxetine 90 mg in premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Ther. 2002;24:417–33. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)85043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearlstein TB, Bellew KM, Endicott J, Steiner M. Paroxetine controlled release for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Remission analysis following a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psych. 2005;7:53–60. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v07n0203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steiner M, Hirschberg AL, Bergeron R, Holland F, Gee MD, Van Erp E. Luteal phase dosing with paroxetine controlled release (CR) in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:352–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kornstein SG, Pearlstein TB, Fayyad R, Farfel GM, Gillespie JA. Low-dose sertraline in the treatment of moderate-to-severe premenstrual syndrome: efficacy of 3 dosing strategies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1624–32. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yonkers KA, Holthausen GA, Poschman K, Howell HB. Symptom-onset treatment for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:198–202. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000203197.03829.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deeks JJ. Word limits best explain failings of industry supported meta-analyses. BMJ. 2006;333:1021. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39024.372662.1F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freeman EW. Luteal phase administration of agents for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:453–68. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halbreich U, Kahn LS. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with luteal phase dosing of sertraline. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4:2065–78. doi: 10.1517/14656566.4.11.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yonkers KA, Pearlstein T, Fayyad R, Gillespie JA. Luteal phase treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder improves symptoms that continue into the postmenstrual phase. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:317–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]