Abstract

Introduction:

Initial research on older smokers suggests that a subgroup of smokers with higher levels of psychological distress and health problems may be more likely to quit smoking than older smokers with fewer such problems. The present study, based on prospective data from a biracial sample of older adults (N = 4,162), examined characteristics of older adult smokers by race and gender.

Methods:

The present study uses both cross-sectional and prospective data to examine the association between smoking behavior, smoking cessation, health functioning, and psychological distress in a biracial sample of community-dwelling older adults.

Results:

We found baseline psychological distress to be associated with poor health functioning. Consistent with hypotheses, baseline (Time 1) psychological distress predicted smoking cessation 3 years later (Time 2). Moreover, the change in health problems between Time 1 and Time 2 fully mediated the association between Time 1 distress and smoking cessation.

Discussion:

Smoking cessation behavior of older adults is best explained by higher levels of distress and health problems regardless of race or gender. These findings may have important treatment implications regarding smoking cessation programs among older adults. Older adult smokers with higher levels of psychological distress and health problems may be more motivated to quit smoking than those with fewer such problems. These difficulties should be targeted within the context of the smoking cessation protocol. Also, we identified a subgroup of older smokers who are reporting fairly good health and lower levels of distress and who are less likely to quit smoking. Motivational methods may need to be developed to engage this group in smoking cessation treatment.

Introduction

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of premature death among older adults. Older adults who are cigarette smokers have increased medical problems, health care costs, disability, and mortality (Fillenbaum, Burchett, Kuchibhatla, Cohen, & Blazer, 2007; Hsu & Pwu, 2004; Rapuri, Gallagher, & Smith, 2007). Smoking predicts quality of life as well as mortality (Ferrucci et al., 1999). That is, nonsmokers not only have longer lives, but this increased life expectancy is also associated with more disability-free years of life (Fried, 2000). Given the rapid growth of the elderly population, we expect the medical, social, and economic consequences of smoking among older adults to become a greater burden over the next several decades.

Elderly individuals who have smoked for 3–4 decades can benefit substantially by abstaining from cigarette smoking. In their review of the literature on the positive effects of smoking cessation among older adults, LaCroix and Omenn (1992) concluded that older smokers who quit smoking have a reduced risk of premature death, markedly reduced risk of coronary events, slower decline in pulmonary function, and slower progression of osteoporosis, thus reducing the risk of hip fractures. Given the severity of health problems associated with smoking in older adults and the significant health benefits from quitting smoking even after decades of smoking, understanding characteristics of older smokers and smoking cessation patterns is vital in the development of specialized cessation programs.

In the general population, a number of demographic characteristics are related to quit attempts and successful quits. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2000, an estimated 70% of smokers said they wanted to quit, and 41% had tried to quit during the preceding year; however, marked differences in successful quitting were observed among demographic groups (CDC, 2002). In developing treatment programs for subpopulations of individuals, it is important to identify characteristics of those who are more likely and those who are less likely to quit smoking. For example, in one large epidemiological study of the general population, no racial differences in attempts to quit smoking were found; however, Whites were more successful at quitting smoking in comparison to minorities (Barbeau, Krieger, & Soobader, 2004). Researchers have found that Blacks are less likely than Whites to quit smoking (Fernander & Schumacher, 2006), though research suggests that the gap is narrowing (King, Polednak, Bendel, Vilsaint, & Nahata, 2004). Males are more likely than females to smoke, and a higher percentage of male smokers quit smoking compared with female smokers (Escobedo & Peddicord, 1996). Among older adults, however, few prospective studies have examined demographic characteristics that contribute to smoking cessation. This lack of data is unfortunate given the likelihood that gender and racial differences in smoking cessation behavior may have implications for identifying groups of smokers with different needs in terms of treatment interventions.

Research focusing on the comorbidity between psychological distress and smoking prevalence in the general population has found that individuals who smoke have higher rates of psychological distress than nonsmokers (Coambs, Kozlowski, & Ferrence, 1989; Hughes, 1993; Hughes & Brandon, 2003). That is, cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that, compared with nonsmokers, smokers have higher rates of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and general psychological distress. Similar such findings have been observed among older adults in several cross-sectional studies (Colsher et al., 1990; Honda, 2005; Lam et al., 2004; Salive & Blazer, 1993).

The higher rates of psychological distress found in smokers may be related to difficulties in smoking cessation. The “selection hypothesis of smoking” posits that smokers who are burdened by psychiatric difficulties, such as anxiety or depressive symptoms, may have a harder time quitting than those with lower levels of distress (Coambs et al., 1989; Hughes, 1993; Hughes & Brandon, 2003). Indeed, younger adults who are successful in quitting smoking have lower rates of psychological distress than those who do not quit (Coambs et al., 1989; Hughes, 1993; Hughes & Brandon, 2003). Thus, among younger adults, consequential individual difference variables appear to be associated with smoking cessation.

Although psychological distress is likely to increase the difficulty associated with successful quitting, preliminary research suggests that older adults with higher rates of distress may be more likely to quit smoking. For example, smoking cessation data obtained from the Duke established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly (EPESE) sample found clinically depressed women, but not men, to be more likely to quit smoking than women without depression (Salive & Blazer, 1993). Thus, psychological distress may be higher among those older females who quit smoking compared with those who continue to smoke. Research also suggests that, among older adults, smokers with health problems are more likely to quit smoking (Abdullah et al., 2006; Chaaya, Mehio-Sibai, & El-Chemaly, 2006). In particular, poor health has been found to be predictive of depressive symptoms among older adults (Blazer & Hybels, 2005). Thus, the association between depressive symptoms and smoking cessation identified in some studies of older adults may reflect, in part, the severity of the individual's health problems.

In contrast to the selection hypothesis, which has been found to characterize younger smokers, we propose the “distress hypothesis,” according to which older adults who are experiencing high levels of psychological distress and health problems will be more motivated to quit than those with lower levels of such problems. Specifically, based on these initial findings, we propose that a subgroup of older smokers is more likely to quit smoking and that these characteristics are related to a combination of risk factors associated with psychological distress and health problems. We believe that poor health is likely to be a more potent factor in influencing older adults, compared with younger adults, to quit smoking. Further, we expect psychological distress to be associated with poor health functioning. Thus, we suggest that older adults with higher levels of psychological distress (due in part to health problems) will be more likely to quit smoking than will those with lower levels of such problems, especially if they experience further health problems. Specifically, we predict that the association between psychological distress and subsequent smoking cessation will be explained, in great part, by health problems.

The extent to which psychological distress and health-related problems motivate smoking cessation or, in contrast, the extent to which psychological distress interferes with smoking cessation has not been studied systematically in older adults nor have these hypotheses been examined by gender or race. Given that rates of smoking and smoking cessation differ for men and women and for Blacks and Whites, variables that contribute to smoking cessation among these groups also may differ.

The present study uses both cross-sectional and prospective data to examine the association between smoking behavior, smoking cessation, health functioning, and psychological distress in a biracial sample of community-dwelling older adults. The data for the present study were obtained from the Duke-EPESE (Cornoni-Huntley et al., 1993), a longitudinal study of adults aged 65 years or older. Using these prospective data, we examined predictors of smoking cessation over a 3-year period. In line with prior work, we hypothesized that psychological distress and health problems would predict smoking cessation among older adults. However, the primary, unique aim of the present report was to determine whether the association between psychological distress and smoking cessation would be explained, in great part, by health problems. We did not have any specific hypotheses regarding how results might differ by gender or race, but we conducted explorative analyses to examine possible differences.

Methods

Data for this study were derived from the Duke-EPESE (Cornoni-Huntley et al., 1990). This population survey was part of a multicenter, collaborative epidemiological investigation of physical, psychological, and social functioning of persons aged 65 years or older. The North Carolina sample used in the present study consisted of community residents selected from five contiguous Piedmont counties. Blacks were purposely oversampled. We focused on data from the baseline interview (Time 1, 1986–1987; N = 4,162, 54.3% Black) and a second wave interview conducted 3 years later (Time 2, 1989–1990; N = 3,559, 54.6% Black).

The study used a probability sample of community residents. Participants were sampled in a way that allowed for the development of weights that took into account the probability of being selected and that matched demographic characteristics of the counties surveyed. These weights were used in the analysis of Time 1 data. The sampling design has been described in greater detail previously (Cornoni-Huntley et al., 1993).

The response rate at baseline was 80%. At the second wave (e.g., Time 2), 908 participants (including 126 Time 1 smokers) were not interviewed; most had died since Time 1. Furthermore, we did not have complete Time 2 data for 91 Time 1 smokers who were interviewed at Time 2; these smokers were excluded from prospective analyses. Most were missing data on Time 2 smoking status as well as other variables. A detailed description of the participants who died or for whom Time 2 data were missing is provided below.

Measures

Demographics.

A comprehensive demographic section of the survey assessed gender, family income, education, and race of participants.

Measurement of psychological distress.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item, self-report scale that was developed to measure depressive symptomatology in a community population (Radloff, 1977). The application of a standardized cutoff score has been shown to provide a valid and reliable measure for clinical depression (Irwin, Artin, & Oxman, 1999). However, the CES-D full-scale score provides a measure of general, nonspecific psychological distress as well as depressive symptoms (Vernon & Roberts, 1981). In addition to depression, the CES-D appears to tap aspects of state and trait anxiety (Orme, Reis, & Herz, 1986). Thus, the CES-D is a particularly appropriate measure to assess the association between smoking and psychological distress.

The CES-D was administered to all participants at both Time 1 and Time 2. For ease of administration, a dichotomous response scale was used for each item, coded 0 (no) and 1 (yes) (Irwin et al., 1999). Responses across the 20 items were summed to create a CES-D scale score for Time 1 (α = .82) and Time 2 (α = .86), with higher scores indicating more symptoms of psychological distress.

Specific medical problems at Time 1.

At Time 1, participants were asked whether they had been diagnosed by a medical professional as having a heart attack, high blood pressure, diabetes, stroke, broken hip, or cancer. Each health problem was coded based on the participant's response as follows: 0 (no), 1 (maybe), or 2 (yes).

Specific medical problems at Time 2.

At Time 2, participants were asked if a physician had told them they had experienced any of the following health problems over the past 3 years since the baseline interview, including having a heart attack, high blood pressure, diabetes, stroke, broken hip, or cancer. Participants’ responses were coded as follows: 0 (no), 1 (maybe), or 2 (yes).

Number count of medical problems at Time 1.

A count of the number of specific health problems (e.g., heart attack, high blood pressure, diabetes, stroke, broken hip, or cancer) at Time 1 was derived from the variables described above. This variable was then used to test a mediation model. That is, we examined whether the number of Time 1 medical problems mediated the association between Time 1 psychological distress and smoking cessation.

Number count of medical problems at Time 2.

A count of the number of medical problems that occurred between Time 1 and Time 2 was derived from the specific medical problems described above. This variable was examined as a possible mediator of the association between psychological distress and smoking cessation.

Physical functioning.

Physical functioning problems were measured at both Time 1 (α = .79) and Time 2 (α = .87) by three items from the Rosow–Breslau Functional Health Scale (Rosow & Breslau, 1966). These items pertained to doing heavy housework, walking up and down stairs, and walking one-half mile. The scale has been used extensively in epidemiological studies of the elderly, and its validity and reliability have been well established (Alexander et al., 2000; Reuben, Siu, & Kimpau, 1992).

Smoking.

Participants were asked at both Time 1 and Time 2 if they currently were a regular cigarette smoker (no, yes). From these responses, we were able to determine whether participants had quit smoking over the 3-year period (e.g., still smoking, quit smoking). Self-report of smoking behavior has been used predominately to assess smoking behavior in large epidemiological studies (Kessler et al., 2004) and has been shown to have good validity (Patrick et al., 1994).

Data analyses

Descriptive analyses.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for smokers and nonsmokers at baseline. We identified individuals who had been smokers at Time 1 and determined whether the participant had quit smoking between Time 1 and Time 2. Table 2 describes the characteristics of these smokers by quit status at Time 2. To better understand the influence of attrition on the results, we then looked at characteristics of participants who were interviewed at Time 1 but not at Time 2. In particular, we examined attrition among smokers by race and gender. In addition, descriptive statistics for Time 1 smokers with some missing data at Time 2 are described in greater detail in the Results section.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by smoking status

| Variable | Smokers (n = 714) | Nonsmokers (n = 3,448) | F value or χ2 | p value |

| Age (years) | 70.6 (6.1) | 74.1 (6.0) | F = 178.6 | <.001 |

| Gender | 58.8% males | 30.1% males | χ2 = 214.361 | <.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 47.9% | 44.8% | χ2 = 2.24 | .07 |

| Black | 52.1% | 55.2% | ||

| Mean income (SD) | $10,913 (9,725) | $10,052 (9,928) | F = 4.48 | .034 |

| Mean years of education (SD) | 8.30 (4.01) | 8.51 (4.1) | F = 1.54 | .215 |

| Mean physical functioning problems (SD) | 0.83 (1.08) | 0.98 (1.16) | F = 11.34 | < .001 |

| High blood pressure | 45.8% no | 41.9% no | χ2 = 4.51 | .105 |

| 3.2% maybe | 2.8% maybe | |||

| 51.0% yes | 55.3% yes | |||

| Diabetes | 82.7% no | 79.3% no | χ2 = 4.58 | .1 |

| 1.8% maybe | 2.5% maybe | |||

| 15.4% yes | 18.2% yes | |||

| Broken hip | 96.9% no | 96.1% no | χ2 = 1.07 | .586 |

| 0.1% maybe | 0.2% maybe | |||

| 2.9% yes | 3.7% yes | |||

| Stroke | 90.3% no | 91.2% no | χ2 = 1.5 | .41 |

| 1.4% maybe | 0.9% maybe | |||

| 8.3% yes | 7.8% yes | |||

| Cancer | 89.4% no | 88.0% no | χ2 = 2.97 | .23 |

| 0.7% maybe | 1.5% maybe | |||

| 9.9% yes | 10.5% yes | |||

| Heart attack | 84.1% no | 85.1% no | χ2 = 1.1 | .58 |

| 2.5% maybe | 2.9% maybe | |||

| 13.3% yes | 12.1% yes |

Table 2.

Time 1 smokers by quit status at Time 2

| Variables | Still smoking (n = 222) | Quit smoking (n = 53) | F value or χ2 | p value |

| Age (years) | 69.7 | 70.8 | F = 5.2 | .02 |

| Gender | 80.7% males, 71.0% females | 19.3% males, 29.0% females | χ2 = 6.5 | <.01 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 74% | 26% | χ2 = 2.4 | .07 |

| Black | 77.9% | 22.1% | ||

| Mean income | $10,705 | $12,767 | F = 4.1 | .04 |

| Mean years of education | 8.3 | 9.2 | F = 4.3 | .04 |

| Mean physical functioning problems | 0.86 | 1.03 | F = 2.4 | .12 |

| High blood pressure | 45.8% no | 33.1% no | χ2 = 6.0 | .05 |

| 3.7% maybe | 42.0% maybe | |||

| 50.5% yes | 62.7% yes | |||

| Diabetes | 92.9% no | 89.8% no | χ2 = 3.02 | .22 |

| 1.6% maybe | 4.2% maybe | |||

| 5.5% yes | 5.9% yes | |||

| Broken hip | 99.7% no | 99.2% no | χ2 = 0.77 | .42 |

| 0% maybe | 0.0% maybe | |||

| 0.3% yes | 0.8% yes | |||

| Stroke | 97.9% no | 98.3% no | χ2 = 1.3 | .5 |

| 0.3% maybe | 0.8% maybe | |||

| 1.8% yes | 0.8% yes | |||

| Cancer | 98.7% no | 93.8% no | χ2 = 5.4 | .07 |

| 0.0% maybe | 0.8 % maybe | |||

| 1.3% yes | 3.4% yes | |||

| Heart attack | 97.6% no | 92.4% no | χ2 = 8.6 | .014 |

| 1.0% maybe | 1.7% maybe | |||

| 1.3% yes | 5.9% yes |

Time 1 baseline cross-sectional analyses.

We conducted a cross-sectional logistic regression analysis on the baseline data to determine if Time 1 CES-D symptoms of distress and health problems were associated with Time 1 smoking status (current smoker or nonsmoker) by race and gender (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cross-sectional logistic regression analysis: predictors of smoking status at baseline

| Variable | β | SE | Wald | p value | Odds ratio |

| Step 1 | |||||

| Gender | −1.15 | 0.08 | 203.09 | <.01 | 0.32 |

| Race | −0.26 | 0.08 | 9.56 | <.01 | 0.77 |

| Age (years) | −0.09 | 0.01 | 158.96 | <.01 | 0.91 |

| Income | 0.00 | 0.00 | 24.64 | <.01 | 1.00 |

| Step 2 | |||||

| Physical functioning | 0.07 | 0.04 | 3.13 | .08 | 1.07 |

| Heart attack | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.17 | .68 | 0.98 |

| High blood pressure | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | .83 | 0.99 |

| Diabetes | −0.13 | 0.06 | 5.98 | .01 | 0.88 |

| Broken hip | −0.09 | 0.12 | 0.53 | .47 | 0.92 |

| Stroke | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | .91 | 1.01 |

| Cancer | −0.08 | 0.07 | 1.42 | .23 | 0.92 |

| Step 3 | |||||

| CES-D symptoms of distress | 0.04 | 0.01 | 12.88 | <.01 | 1.04 |

| Step 4 | |||||

| Sex × race | −0.98 | 0.16 | 36.64 | <.01 | 0.38 |

| Depression × race | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.19 | .67 | 0.99 |

| Sex × depression | −0.05 | 0.02 | 4.14 | .04 | 0.95 |

| Step 5 | |||||

| Three-way interaction | 0.09 | 0.05 | 3.46 | .06 | 1.09 |

Note. CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.

Prospective analyses.

We conducted a prospective logistic regression analysis to examine if (a) Time 1 CES-D symptoms (e.g., psychological distress), (b) health problems at baseline, or (c) the change in health problems between Time 1 and Time 2 predicted smoking cessation at Time 2. To examine whether there were gender and racial differences in patterns of smoking cessation, we also considered interactions between distress, health problems, race, and gender. Results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Prospective logistic regression analysis: Predictors of smoking cessation

| Variable | β | SE | Wald | p value | Odds ratio |

| Step 1 | |||||

| Gender | 0.45 | 0.22 | 4.09 | .04 | 1.57 |

| Race | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.00 | .97 | 1.01 |

| Age (years) | 0.05 | 0.02 | 5.00 | .03 | 1.05 |

| Income | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.43 | .06 | 1.00 |

| Step 2 | |||||

| Physical functioning | −0.02 | 0.12 | 0.03 | .85 | 0.98 |

| Heart attack | 0.28 | 0.17 | 2.71 | .10 | 1.32 |

| High blood pressure | 0.26 | 0.12 | 4.59 | .03 | 1.30 |

| Broken hip | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.74 | .39 | 1.39 |

| Diabetes | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.68 | .41 | 1.13 |

| Stroke | −0.68 | 0.33 | 4.26 | .04 | 0.51 |

| Cancer | −0.07 | 0.20 | 0.13 | .72 | 0.93 |

| Step 3 | |||||

| Time 1 distress | 0.06 | 0.03 | 4.04 | .04 | 1.07 |

| Step 4 | |||||

| Physical functioning | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.20 | .66 | 1.07 |

| Heart attack | 0.67 | 0.32 | 4.38 | .04 | 1.95 |

| High blood pressure | 0.21 | 0.17 | 1.46 | .23 | 1.23 |

| Broken hip | 0.24 | 0.74 | 0.11 | .75 | 1.27 |

| Diabetes | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.26 | .61 | 1.13 |

| Stroke | −0.30 | 0.52 | 0.34 | .56 | 0.74 |

| Cancer | 0.48 | 0.37 | 1.72 | .19 | 1.62 |

| Step 5 | |||||

| Time 2 distress | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | .87 | 1.01 |

| Step 6 | |||||

| Sex × race | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.20 | .65 | 1.23 |

| Time 1 distress × race | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.49 | .49 | 0.96 |

| Sex × Time 1 distress | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.14 | .71 | 0.98 |

| Step 7 | |||||

| Three-way interaction | −0.08 | 0.13 | 0.40 | .53 | 0.92 |

Mediation analyses.

In separate prospective analyses, we tested 2 potential mediation models. First, we tested whether psychological distress mediated the relationship between health problems and smoking cessation. Second, and consistent with our predictions, we evaluated whether changes in health problems between Time 1 and Time 2 mediated the relationship between psychological distress and smoking cessation.

Results

Descriptive statistics

At baseline, participants (N = 4,162) were 16.6% White males, 18.6% Black males, 31.0% White females, and 33.8% Black females. Smokers were more likely to be male than female (28.6% vs. 10.9%, χ2 = 214.4, p < .001). Whereas we found no significant differences in rates of smoking by race (18.2% White vs. 16.6% Black), when we considered gender and race together, differences emerged. Specifically, Black males were more likely to smoke than White males (31.9% vs. 25%, χ2 = 8.3, p < .01). In contrast, White females were more likely to smoke than Black females (14.4% vs. 8.0%, χ2 = 27.8, p < .01).

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the participants by smoking status at baseline. At baseline, the average age of participants was 73.56 years (SD = 6.7). Smokers were considerably younger than nonsmokers (70.6 vs. 74.1, respectively; p < .001), which has implications for direct comparisons of the two groups. As people age, their health problems tend to increase, particularly among older adults (Blazer & Hybels, 2005). Although one would expect smokers to have more health problems than nonsmokers, in the present study, this age difference would likely influence direct comparisons between smokers and nonsmokers on health functioning measures. Indeed, in uncontrolled analyses, we found no differences between smokers and nonsmokers in rates of Time 1–specific health problems. Moreover, smokers reported fewer physical functioning problems compared with nonsmokers (0.83 vs. 0.98, respectively; p < .001). Nonsmokers had a significantly higher income (though the actual difference was small) compared with smokers US$10,913 vs. $10,052, respectively; p < .001).

Baseline smoking status was significantly associated with Time 1 symptoms of distress once demographic variables (gender, race, and age) were controlled for in the analyses, F(1, 3,971) = 7.7, p < .01. In particular, CES-D distress was related to health functioning at Time 1. Indeed, CES-D symptoms of distress were correlated with each measure of health functioning assessed at Time 1 included in our analyses (e.g., physical functioning problems, high blood pressure, heart attack, stroke, cancer, broken hip, and number of health problems; all p values < .001). Time 1 CES-D distress also was significantly correlated with each of the Time 2 health problems (e.g., Time 2 physical functioning problems, high blood pressure, heart attack, stroke, cancer, broken hip, and number of health problems; all p values < .001). It may be that Time 1 distress was an indicator of the severity of health problems at Time 1, which is a risk factor for health problems occurring between Time 1 and Time 2.

Of the Time 1 participants, 908 were not interviewed at Time 2 (including 126 smokers), among which more than two-thirds had died. Not surprisingly, participants who died (or refused) were significantly older than those who survived; 75.1 versus 73.3 years, F(1, 4,160) = 38.8, p < .01. Attrition was related to smoking status. Although at baseline smokers were younger than nonsmokers, a much higher percentage of smokers than nonsmokers died (or refused to be interviewed) between Time 1 and Time 2 (17.8% vs. 13.9%, χ2 = 9.3, p < .01). Among the Time 1 smokers, we also found differences in attrition by race and gender. Specifically, rates of attrition were significantly higher for White male smokers than for White male nonsmokers (24.9% vs. 16.1%, χ2 = 8.4, p < .01). However, none of the other gender by race group differences were significant. Overall, smokers who died (or refused to be interviewed) had higher levels of CES-D distress at Time 1 than those who survived; 3.64 versus 2.18 years, F(1, 3,994) = 8.5, p < .01. However, post-hoc analyses revealed that the difference was significant only when comparing White male smokers who died (or refused) with White male smokers who were interviewed at Time 2 (3.7 vs. 2.1, p = .024). Not surprisingly, we found differences by Time 1 health status. Smokers who died (or refused) had higher levels of each of the health measures included in the study than did smokers who were interviewed at Time 2 (all p values < .01). Post-hoc analyses revealed that this difference was significant for each group by race and gender (all p values < .01).

Smoking status at baseline cross-sectional analysis

We performed a logistic regression analysis on the baseline data with the continuous measure of CES-D symptoms and the specific Time 1 health problems (e.g., heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke, diabetes, broken hip, cancer, and physical functioning problems) as the predictor variables and Time 1 smoking status (current smoker, nonsmoker) as the criterion variable (see Table 3). We also included interactions between psychological distress, race, and gender (e.g., gender and CES-D, CES-D and race, gender and race).

In the first step, we found the following characteristics to be related to current smoking at baseline: male gender, Wald(1, 3,927) = 203.1, p < .001, odds ratio [OR] = 0.32; younger age, Wald(1, 3,927) = 159.9, p < .001, OR = 0.91; lower income, Wald(1, 3,927) = 24.6, p = .03, OR = 1.01; and White race, Wald(1, 3,927) = 9.6, p < .01, OR = 0.77. In the next step, we entered the Time 1 health variables. Diabetes was related to smoking, Wald(1, 3,920) = 6.0, p = .014, OR = 0.88, such that nonsmokers were more likely than smokers to have diabetes (which may be related to the older age of the nonsmokers). Nonsmokers also had increased physical functioning problems, Wald(1, 3,920) = 208, p = .04, OR = 1.1. In the next step, we included symptoms of psychological distress (e.g., CES-D symptoms). Higher levels of Time 1 CES-D symptoms were associated with smoking at Time 1, Wald(1, 3,919) = 11.7, p < .001, OR = 1.05.

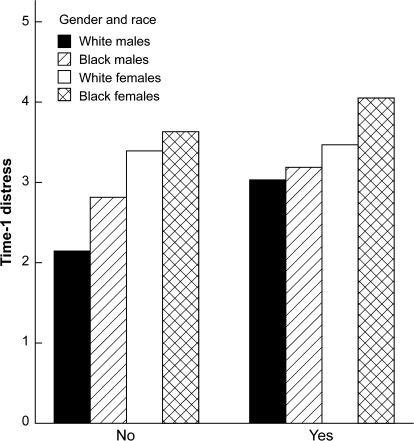

In the next step, we entered the two-way interactions (e.g., gender and CES-D, CES-D and race, gender and race). The interaction of gender and race, Wald(1, 3,917) = 31, p < .001, OR = .38, predicted smoking status. The interaction of gender and CES-D symptoms of distress approached significance, Wald(1, 3,917) = 3.5, p = .055, OR = .95. We then entered the three-way interaction, which was not significant. Additional analyses were conducted to determine the nature of the interaction. Figure 1 illustrates Time 1 smoking status in relation to race, gender, and CES-D symptoms. Chi-square post-hoc analyses using the least significant difference revealed that rates of CES-D symptoms were generally higher for females than males, higher for Blacks than Whites, and higher for smokers than nonsmokers (all p values < .05). However, for White females (but not males), we found no differences in CES-D symptoms of distress between smokers and nonsmokers at baseline.

Figure 1.

Time 1 smoking status and Time 1 CES-D psychological distress by race and gender. CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.

Wave 2 data

Surviving participants (N = 3,003) were interviewed 3 years later (Time 2). Among these participants were 497 participants who were smokers at Time 1 and for whom we had all relevant data. However, among the Time 1 smokers were 126 smokers who had died or refused to be interviewed at follow-up. We did not have complete Time 2 data needed for the analyses for 91 Time 1 smokers who were interviewed at Time 2. Most of these smokers had missing data on Time 2 smoking status as well as other variables. As we have found in other studies using the EPESE dataset (Sachs-Ericsson et al., 2007), participants with some missing Time 2 data had, at Time 1, higher rates of CES-D depressive symptoms, poorer health functioning, and higher numbers of problems on a measure of cognitive functioning (all p values < .01). However, we found no differences by gender, race, or age.

Among the Time 1 smokers for whom we had complete data, 24% (n = 118) reported having quit smoking. More females than males had quit smoking (29.0% vs. 19.3%, χ2 = 6.8, p < .001). However, rates of smoking cessation were neither significantly different for White and Black males (22.1% vs. 18.1%) nor for White and Black females (20.0% vs. 20.3%). See Table 2 for the descriptive statistics for Time 2 data by quit status.

Predictors of smoking cessation: longitudinal analysis

Regression analyses were conducted with Time 1 smokers to determine if Time 1 distress predicted smoking status at Time 2. We performed a longitudinal logistic regression analysis to examine predictors of smoking cessation. We used Time 2 smoking status (still smoking or quit smoking) as the criterion variable. The results are summarized in Table 4. In the first step of the logistic regression analysis, we found female gender, Wald(1, 484) = 4.4, p = .04, OR = 1.6; older age, Wald(1, 484) = 5.1, p = .03, OR = 1.6; and higher income, Wald(1, 484) = 4.0, p = .046, OR = 1.01, to predict smoking cessation. In the next step, we entered the Time 1–specific health problems (e.g., heart attack, high blood pressure, broken hip, diabetes, stroke, or cancer) and physical functioning problems. Having had high blood pressure at Time 1, Wald(1, 477) = 4.8, p = .028, OR = 1.3, predicted smoking cessation by Time 2. However, having had a stroke before Time 1 was associated with an increased likelihood that the participant would not quit smoking, Wald(1, 477) = 4.1, p = .043, OR = 0.50. No other specific Time 1 health variables were related to smoking status. After the inclusion of Time 1 health variables, female gender was no longer related to smoking cessation.

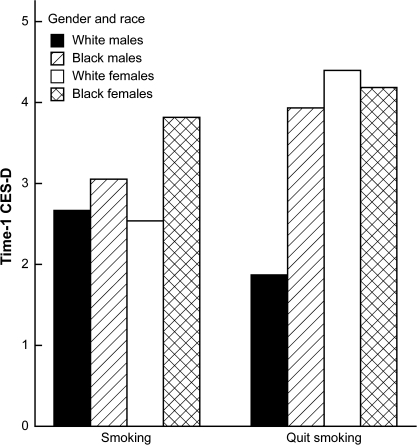

On the next step, we entered Time 1 psychological distress. Increased distress at Time 1 predicted smoking cessation, Wald(1, 476) = 3.87, p = .041, OR = 1.1. In the following step, we entered the two-way interactions, none of which was significant. On the final step, we included the three-way interaction (e.g., Time 1 CES-D symptoms, race, and gender), which was significant, Wald(1, 472) = 3.87, p = .045, OR = 0.77. The interaction is illustrated in Figure 2. Additional analyses were conducted to determine the nature of the interaction. Participants who quit smoking tended to have higher levels of distress at Time 1 than those who did not quit (p = .05). For White women and for Black women, post-hoc analyses revealed that Time 1 distress was greater for those who quit smoking than for those who continued to smoke (all p values < .01). We found no significant difference in level of Time 1 distress for the males in terms of their smoking status. However, as depicted in Figure 2, the pattern of results for Black males was similar to that for female quitters and nonquitters, with Time 1 distress greater for those who quit smoking than for those who continued to smoke. Interestingly, and in contrast, White males who quit smoking had relatively low rates of Time 1 distress compared with all other participants. However, this result needs to be viewed in light of the selective attrition of White male smokers who were more depressed at Time 1 and had greater health problems at Time 1 compared with White male smokers who were interviewed at Time 2.

Figure 2.

Time 1 CES-D symptoms and Time 2 quit status by race and gender. CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.

Time 2 health problems.

We repeated the above longitudinal logistic regression analyses, and this time we included the specific health problems that occurred between Time 1 and Time 2 (e.g., heart attack, high blood pressure, broken hip, diabetes, stroke, or cancer) and Time 2 physical functioning problems. Having had a heart attack between Time 1 and Time 2 was a significant predictor of smoking cessation, Wald(1, 465) = 4.1, p = .048, OR = 1.9. People who had a heart attack between Time 1 and Time 2 were nearly twice as likely to quit smoking as those who did not have a heart attack. None of the other health-related problems were significantly related to smoking status. Nonetheless, with the inclusion of all the Time 2 health problems, Time 1 psychological distress was no longer related to smoking status. Hence, changes in health problems between Time 1 and Time 2 appear to explain, in part, the association between Time 1 psychological distress and smoking cessation. Formal mediation analyses were conducted (see Mediation analyses section). After inclusion of the Time 2 health variables, neither gender nor race predicated smoking cessation.

On the next step, we included Time 2 depression, which was unrelated to Time 2 smoking status. We then included the two-way and three-way interactions among race, gender, and Time 1 distress. None of the interactions were significant. Indeed, after we controlled for the Time 2 health problems, there was no longer an association between Time 1 distress and smoking cessation, regardless of race or gender.

Mediation analyses

According to Baron and Kenny (1986), starting with the assumption that the independent variable has a significant effect on the outcome variable, three conditions must be met to establish mediation. First, the independent variable should predict the prospective mediator. Second, the mediator should predict the outcome variable. Third, when both the mediator and the independent variable are included in the regression equation, the independent variable should no longer predict the outcome variable.

Mediation analyses focused on psychological distress as a potential mediator between change in health problems and smoking cessation.

To test for the basic assumption for mediation, the independent variable (change in health status between Time 1 and Time 2) must predict the dependent variable (smoking status at Time 2). We found this condition to be met; Time 2 medical problems predicted smoking cessation after controlling for demographics and Time 1 health problems, Wald(1, 465) = 8.4, p = .004, OR = 1.3. The first criterion necessary for mediation is that the independent variable (change in health problems) should predict the potential mediator (psychological distress). We found this association to be significant, F(1, 465) = 6.7, p = .008. Second, to examine the next criterion for mediation, we performed a logistic regression analysis to examine the association between the potential mediator (Time 1 psychological distress) and the dependent variable (smoking cessation) after controlling for demographics and Time 1 and Time 2 health problems. This association was not significant; therefore, the criteria for mediation were not met. We also tested for a similar mediation model, specifically, that the change in psychological distress between Time 1 and Time 2 mediated the association between change in health status and Time 2 smoking status. This model also was not significant.

Mediation analyses focused on change in health status as a potential mediator of the association between psychological distress and smoking cessation.

The basic assumption required to test for mediation was demonstrated in the original longitudinal regression analyses (e.g., Time 1 psychological distress predicted smoking cessation). Establishing the first condition for mediation, we found that the independent variable (Time 1 distress) predicted the prospective mediator (change in health problems occurring between Time 1 and Time 2), F(1, 486) = 3.99, p < .05, after controlling for Time 1 health problems. We then performed a logistic regression analysis to examine the association between the mediator (change in health problems between Time 1 and Time 2) and the dependent variable (smoking cessation). After controlling for demographics and Time 1 health problems, we found that the association was significant, F(1, 465) = 10.8, p < .01, OR = 1.3. Thus, the second condition for mediation was met. For the third condition for mediation to be met, the relationship between Time 1 distress and smoking cessation at Time 2 should no longer be significant when the mediator is included in the analysis. We performed an additional longitudinal logistic regression analysis, controlling for demographics and the Time 1 medical problems count. After including the change in medical problems occurring between Time 1 and Time 2, we found that the association between Time 1 distress and smoking cessation was no longer significant, F(1, 494) = 2.5, p = .11. A Sobel test (Baron & Kenny, 1986) confirmed that the change in medical problems occurring between Time 1 and Time 2 significantly mediated the association between Time 1 distress and smoking cessation (z = 10.81, p < .001).

Discussion

Previous research with the general population has shown that lower levels of psychological distress are associated with individuals who are more likely to quit smoking. Previous research has suggested that among older adults, the characteristics of those who quit smoking may differ from those of younger adults. Building on the work of Salive and Blazer (1993) and Whitson, Heflin, and Burchett (2006), in the present study, we explored smoking behavior among older adults by gender and race.

CES-D symptoms of distress at baseline were generally higher for females than males, higher for Blacks than Whites, and higher for smokers than nonsmokers. In cross-sectional analyses, Time 1 CES-D symptoms of distress were correlated with several indices of poor health functioning at baseline. In prospective analyses, older adults who experienced greater levels of psychological distress at Time 1 were more likely to have quit smoking 3 years later compared with those smokers with lower levels of such problems. Further, the number of health problems occurring between Time 1 and Time 2 fully mediated the association between distress and smoking cessation. Thus, although Time 1 psychological distress predicted smoking cessation at Time 2, health problems occurring between Time 1 and Time 2 explained the association between Time 1 distress and smoking cessation.

How do health problems occurring between Time 1 and Time 2 mediate the association between symptoms of distress measured at Time 1 and smoking cessation at Time 2? First, distress at Time 1 was highly associated with Time 1 health problems. Still, distress predicted the association even after controlling for Time 1 health problems. Although we were able to measure the presence or absence of health problems, we could not measure the severity of the health problems. The severity of the Time 1 health problems may be associated with the level of Time 1 distress. Moreover, symptoms of distress assessed at Time 1 may be associated with unmeasured Time 1 health problems. As suggested by Black, Markides, and Ray (2003), depression among older adults may be a marker for underlying disease severity. The severity of health problems at Time 1, in turn, is a risk factor for subsequent health problems. A second, but not mutually exclusive, possibility is that Time 1 distress itself contributed to increased health problems occurring between Time 1 and Time 2 (Black et al., 2003). Time 1 depressive symptoms were associated with each of the Time 2 health measures. We also tested for this alternative explanation, specifically that psychological distress mediated the association between change in health problems and smoking cessation; this model was not significant.

We identified racial and gender differences in the prediction of smoking cessation. Psychological distress predicted smoking cessation for the sample as a whole but not for White males. Among White males, those with lower levels of distress were more likely to quit smoking. These results should be viewed in light of our findings of selective attrition. For White male smokers, those with higher levels of Time 1 distress and health functioning problems were more likely to have died (or refused to be interviewed again) by Time 2. Due to selective attrition, we may have been unable to identify the smoking cessation patterns of White males who have higher levels of distress and health problems. Nonetheless, it appears that White male smokers who were interviewed at Time 2 had relatively high rates of Time 2 health problems as well as Time 2 symptoms of distress. We can only speculate that the present results suggest for White male smokers that the experience of increased health problems between Time 1 and Time 2 explains, in great part, their smoking cessation behavior. Indeed, among older smokers who have relatively low levels of distress and health problems, the occurrence of a significant health problem may be pivotal in an individual's decision to quit smoking. Interventions that directly address the motivation to quit smoking may be essential in addressing the needs of older smokers who have yet to experience the negative effects of smoking. Furthermore, in contrast to younger populations, we found women to be more likely than men to quit smoking. This gender difference appears to be related to increased health problems among women compared with men. After we controlled for the specific health problems, female gender no longer predicted smoking cessation. Indeed, after controlling for Time 2 health problems, we found no gender or racial differences in smoking cessation.

The present study's results support the development of two very different approaches to treating older adults who are smokers. First, older adults who will attempt to quit smoking are likely to have relatively high rates of health problems and psychological distress. Such problems have implications for developing treatment cessation programs for this segment of the population. Health problems and psychological distress should be addressed directly within the context of the smoking cessation programs for older adults. Indeed, negative affect is a leading cause for relapse among quitters (Shiffman, 1982); therefore, smoking cessation programs need to address coping with such negative affect. In contrast, older adults who have lower levels of health problems and distress appear to be less likely to quit smoking. This segment of the population may need a different, more motivational approach to smoking cessation interventions. Smoking cessation programs are being developed to target smokers who have low motivation to quit (Soria, Legido, Escolano, Lopez Yeste, & Montoya, 2006).

Considerable attention has been given to offering smoking cessation programs to young and middle-aged adults, whereas older adults have not been a focus of most interventions (Cox, 1993). Further, women and Blacks may be less likely to receive smoking cessation counseling (Brown et al., 2004), although our results show that among older adults, female smokers were more likely than male smokers to quit smoking and Black smokers were just as likely as White smokers to quit smoking. Moreover, Black males had the highest rate of smoking at baseline compared with all other groups. Even though these data were collected more than 20 years ago, recent data have shown that Black men aged 65 years and older have higher rates of smoking than other groups (National Center for Health Statistics, 2007), and this may be the case particularly among southern populations (CDC, 1999). This finding points out the need for a focus on Black males in developing smoking cessation programs. Barbeau et al. (2004) have noted that more attention should be given to developing programmatic efforts focusing on socioeconomic disparities in smoking behavior, within and across diverse racial, ethnic, and gender groups.

The limited focus on smoking cessation programs for older adults may be due to several misperceptions regarding smoking behavior among older adults. Many researchers may assume that it is too late to attempt to modify risk factors in elders because smoking behavior is so difficult to change (Riegel & Bennett, 2000). Additionally, older smokers may be less apt to quit because they are unaware of the many benefits of smoking cessation even at an advanced age (Donze, Ruffieux, & Cornuz, 2007). However, the benefits of smoking cessation even among older adults are quite substantial. For example, risk of recurrent infarction in smokers may decline by as much as 50% within 1 year of smoking cessation and may normalize to that of nonsmokers within 2 years (Wilhelmsson, Vedin, Elmfeldt, Tibblin, & Wilhelmsen, 1975). Indeed, in the present study, participants who had a heart attack between Time 1 and Time 2 were nearly twice as likely to quit smoking as those who did not have a heart attack. Others have found that smoking cessation strategies for older adults that address psychological distress and beliefs about smoking and health harms would aid in successful cessation (Honda, 2005). In particular, when offered the tools they need, older smokers quit smoking at rates comparable to those of younger smokers (Donze et al., 2007).

Research in the general population has found that smoking cessation programs developed to directly address symptoms of anxiety and depression, in addition to providing standard smoking cessation interventions, are more effective than programs that provide the standard smoking cessation intervention alone (Honda, 2005). Our results demonstrate that older individuals who are most likely to quit smoking generally have high levels of distress; thus, adding a component that addresses psychological distress and coping strategies to deal with compromised health functioning in delivering smoking cessation programs may be vital to best help such older adults quit (Honda, 2005). Significant strides in helping older smokers to quit smoking ultimately will require the development of specialized treatments that target the particular needs of subgroups of smokers (Brown, 2003; Shiffman, 1993).

The present study identified a subgroup of older adult smokers who are less likely than others to quit smoking. These individuals have lower levels of distress and fewer health problems. Although data strongly suggest that it is just a matter of time before smoking-related health problems will affect these smokers, this population may need a different, more motivational approach to even engage them in smoking cessation programs (Schmitt, Tsoh, Dowling, & Hall, 2005). Research is needed to identify public health strategies, including educational and motivational procedures, that will encourage such individuals to consider smoking cessation even though they have yet to feel significant negative effects of smoking. Schmitt et al. (2005) suggest that smoking cessation programs also may target individuals who are not ready to quit and that education about the benefits of quitting smoking in older adults is needed for health professionals as well as older smokers.

As with any study, a number of limitations of the present work point to directions for future studies. In the present study, we relied on participants’ self-report of medical problems identified by a physician. Although self-reports of health problems among older adults have been found to be reliable (Mossey & Shapiro, 1982), some participants may have been unaware of their health problems or may have forgotten about the occurrence of some medical problems assessed in the study. This may have attenuated the observed association between health problems and smoking cessation. Further, a number of medical problems were not assessed; a more comprehensive assessment might have strengthened the association between health and smoking cessation.

Further, results may have been influenced by selective attrition. The attrition rate was high among White male smokers who were depressed and who had higher levels of health problems than smokers who were interviewed at follow-up. Thus, we were unable to identify clear patterns of smoking cessation among White male smokers with high levels of distress and health problems. Additionally, a number of smokers who were interviewed at Time 2 were excluded from analyses because we did not have data on their smoking status at Time 2. Analyses of these participants’ data at Time 1 suggested that these participants also had high levels of depressive symptoms and poor health functioning. If participants with missing data would have quit smoking, the results of the study would be consistent with that reported here. However, at some point, an individual may theoretically be too ill or distressed to quit smoking. Thus, we may have failed to capture a potential curvilinear relationship between distress, health problems, and smoking cessation. Future research is needed to determine if the pattern of smoking cessation identified in the present study also applies to older smokers with more advanced health problems.

Data were collected in the late 1980s. Subsequent cohorts of older adults are more likely to have been exposed to educational materials regarding the negative health effects of smoking before they started smoking. As the current population ages, the differences between the characteristics of older adults and those of the present sample may increase (Morabia, Costanza, Bernstein, & Rielle, 2002). Indeed, given increased knowledge of the profound negative effects of smoking, subsequent cohorts of older adults who continue to smoke into older age may consist of individuals who have had the most difficulties in quitting.

As Husten et al. (1997) have pointed out that, given the rapid growth of the elderly population, the medical, social, and economic consequences of smoking will become a greater burden over the next several decades. Thus, focusing greater attention on providing smoking cessation programs for the elderly should be a priority among public health professionals. Our findings underscore the significant role psychological distress and health problems may play among older adults who may be most likely to quit smoking.

Funding

National Institute on Aging (Contract N01 AG 1 2102).

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abdullah ASM, Ho L-M, Kwan YH, Cheung WL, McGhee SM, Chan WH. Promoting smoking cessation among the elderly: What are the predictors of intention to quit and successful quitting? Journal of Aging and Health. 2006;18:552–564. doi: 10.1177/0898264305281104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander NB, Guire KE, Thelen DG, Ashton-Miller JA, Schultz AB, Grunawalt JC, et al. Self-reported walking ability predicts functional mobility performance in frail older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48:1408–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader M-J. Working class matters: Socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. American Journal of Public Health, 2004;94:269–278. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SA, Markides KS, Ray LA. Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2822–2828. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Hybels CF. Origins of depression in later life. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:1241–1252. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705004411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DW, Croft JB, Schenck AP, Malarcher AM, Giles WH, Simpson RJ. Inpatient smoking-cessation counseling and all-cause mortality among the elderly. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA. Comorbidity treatment: Skills training for coping with depression and negative moods. In: Abrams DB, Niaura RS, Brown RA, Emmons KM, Goldstein MG, Monti PM, editors. The tobacco dependence treatment handbook: A guide to best practices. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 178–229. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: Tobacco use—United States, 1900–1999. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1999;48:986–993. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2000. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2002;51:642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaaya M, Mehio-Sibai A, El-Chemaly S. Smoking patterns and predictors of smoking cessation in elderly populations in Lebanon. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2006;10:917–923. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coambs RB, Kozlowski LT, Ferrence RG. The future of tobacco use and smoking research. In: Ney T, Gale A, editors. Smoking and human behavior. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. pp. 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Colsher PL, Wallace RB, Pomrehn PR, LaCroix AZ, Cornoni-Huntley J, Blazer D, et al. Demographic and health characteristics of elderly smokers: Results from established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1990;6:61–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornoni-Huntley J, Blazer D, Lafferty M, Everett D, Brock D, Farmer M. Established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly: Resource data book (Vol. II) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cornoni-Huntley J, Ostfeld AM, Taylor JO, Wallace RB, Blazer D, Berkman LF, et al. Established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly: Study design and methodology. Aging (Milan, Italy) 1993;5:27–37. doi: 10.1007/BF03324123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL. Smoking cessation in the elderly patient. Clinics in Chest Medicine. 1993;14:423–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donze J, Ruffieux C, Cornuz J. Determinants of smoking and cessation in older women. Age and Ageing. 2007;36:53–57. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo LG, Peddicord JP. Smoking prevalence in US birth cohorts: The influence of gender and education. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:231–236. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernander AF, Schumacher M. Socio-culturally specific stress and coping factors and smoking among African American women. American Association for Cancer Research Meeting Abstracts. 2006;2006:B50. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, Izmirlian G, Leveille S, Phillips CL, Corti M-C, Brock DB, et al. Smoking, physical activity, and active life expectancy. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;149:645–653. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum GG, Burchett BM, Kuchibhatla MN, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG. Effect of cancer screening and desirable health behaviors on functional status, self-rated health, health service use and mortality. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:66–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP. Epidemiology of aging. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2000;22:95–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K. Psychosocial correlates of smoking cessation among elderly ever-smokers in the United States. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu HC, Pwu RF. Too late to quit? Effect of smoking and smoking cessation on morbidity and mortality among the elderly in a longitudinal study. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences. 2004;20:484–491. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70247-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Treatment of smoking cessation in smokers with past alcohol/drug problems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10:181–187. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Brandon TH. A softer view of hardening. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:961–962. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001615330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husten CG, Shelton DM, Chrismon JH, Lin YC, Mowery P, Powell FA. Cigarette smoking and smoking cessation among older adults: United States, 1965–94. Tobacco Control. 1997;6:175–180. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.3.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: Criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159:1701–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, et al. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): Design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G, Polednak A, Bendel RB, Vilsaint MC, Nahata SB. Disparities in smoking cessation between African Americans and Whites: 1990–2000. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1965–1971. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.11.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCroix AZ, Omenn GS. Older adults and smoking. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 1992;8:69–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam T, Li Z, Ho S, Chan W, Ho K, Li M, et al. Smoking and depressive symptoms in Chinese elderly in Hong Kong. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;110:195–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabia A, Costanza MC, Bernstein MS, Rielle J-C. Ages at initiation of cigarette smoking and quit attempts among women: A generation effect. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:71–74. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossey JM, Shapiro E. Self-rated health: A predictor of mortality among the elderly. American Journal of Public Health. 1982;71:800–808. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.8.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2007 with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD.: 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2008, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus07.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orme JG, Reis J, Herz EJ. Factorial and discriminant validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1986;42:28–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198601)42:1<28::aid-jclp2270420104>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking: A review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1086–1093. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rapuri PB, Gallagher JC, Smith LM. Smoking is a risk factor for decreased physical performance in elderly women. The Journal of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2007;62:93–99. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben DB, Siu AL, Kimpau S. The predictive validity of self-report and performance-based measures of function and health. Journal of Gerontology. 1992;47:M106–M110. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.4.m106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel B, Bennett JA. Cardiovascular disease in elders: Is it inevitable? Journal of Adult Development. 2000;7:101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttmann health scale for the aged. Journal of Gerontology. 1966;21:556–559. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs-Ericsson N, Burns AB, Gordon KH, Eckel LA, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, et al. Body mass index and depressive symptoms in older adults: The moderating roles of race, sex, and socioeconomic status. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15:815–825. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180a725d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salive M, Blazer D. Depression and smoking cessation in older adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1993;41:1313–1316. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt EM, Tsoh JY, Dowling GA, Hall SM. Older adults' and case managers' perceptions of smoking and smoking cessation. Journal of Aging and Health. 2005;17:717–733. doi: 10.1177/0898264305280995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Relapse following smoking cessation: A situational analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:71–86. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Assessing smoking patterns and motives. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:732–742. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.5.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria R, Legido A, Escolano C, Lopez Yeste A, Montoya J. A randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. British Journal of General Practice. 2006;56:768–774. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon SW, Roberts RE. Measuring nonspecific psychological distress and other dimensions of psychopathology. Further observations on the problem. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38:1239–1247. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780360055005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitson HE, Heflin MT, Burchett BM. Patterns and predictors of smoking cessation in an elderly cohort. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:466–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsson C, Vedin JA, Elmfeldt D, Tibblin G, Wilhelmsen L. Smoking and myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1975;1:415–420. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)91488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.