Abstract

Autophagy, or cellular self-digestion, is a cellular pathway involved in protein and organelle degradation, with an astonishing number of connections to human disease and physiology. For example, autophagic dysfunction is associated with cancer, neurodegeneration, microbial infection and ageing. Paradoxically, although autophagy is primarily a protective process for the cell, it can also play a role in cell death. Understanding autophagy may ultimately allow scientists and clinicians to harness this process for the purpose of improving human health.

At first glance, it may seem perplexing that a process of cellular self-eating could be beneficial. In its simplest form, however, autophagy probably represents a single cell’s adaptation to starvation—if there is no food available in the surroundings, a cell is forced to break down part of its own reserves to stay alive until the situation improves. In single-cell organisms such as yeasts, this starvation response is one of the primary functions of autophagy, but in fact this role extends up through to humans. For example, even on a day-to-day basis, autophagy is activated between meals in organs such as the liver to maintain its metabolic functions, supplying amino acids and energy through catabolism1,2.

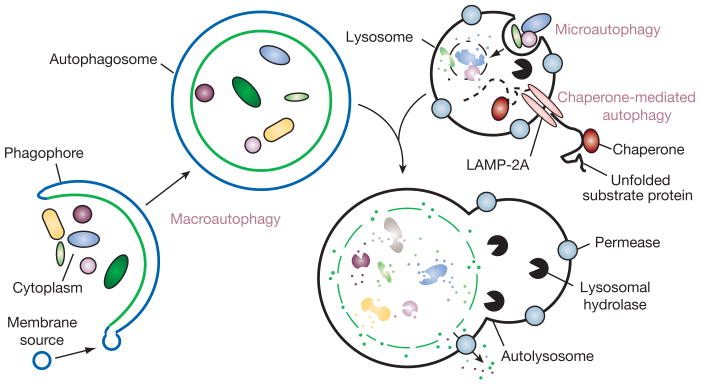

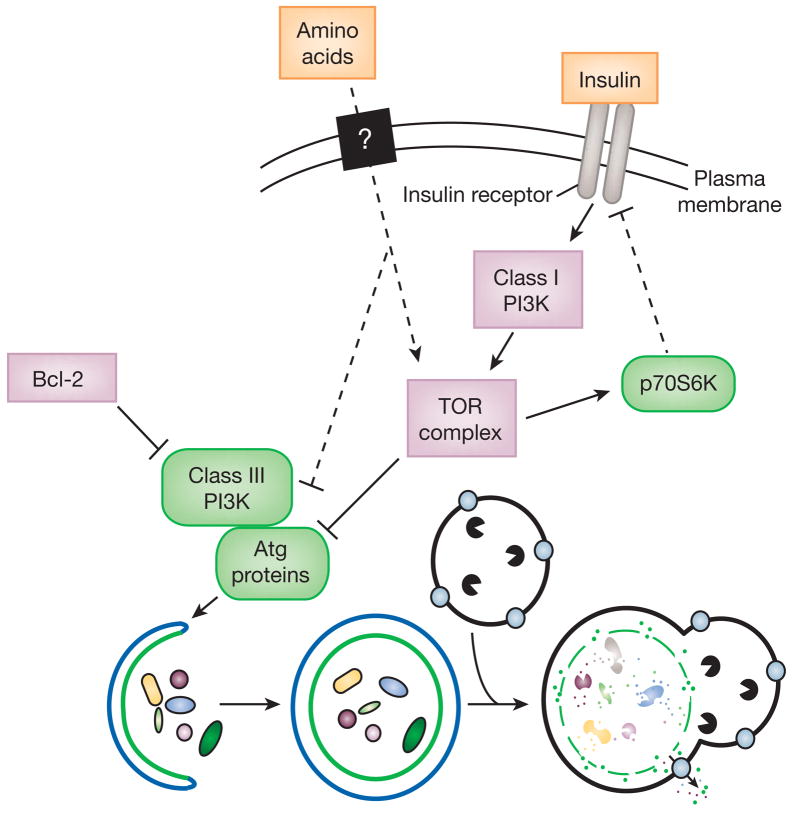

There are various types of autophagy, including micro- and macroautophagy, as well as chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), and they differ in their mechanisms and functions (Fig. 1)3,4. Both micro- and macroautophagy have the capacity to engulf large structures through both selective and non-selective mechanisms, whereas CMA degrades only soluble proteins, albeit in a selective manner. The capacity for large-scale degradation is important in autophagic function, but it carries a certain risk, because unregulated degradation of the cytoplasm is likely to be lethal. On the other hand, basal levels of autophagy are important for maintaining normal cellular homeostasis. Thus, it is important that autophagy be tightly regulated (Fig. 2) so that it is induced when needed, but otherwise maintained at a basal level. Although a complete picture of autophagy regulation is not available, many aspects have been covered in recent reviews5–8.

Figure 1. Different types of autophagy.

Microautophagy refers to the sequestration of cytosolic components directly by lysosomes through invaginations in their limiting membrane. The function of this process in higher eukaryotes is not known, whereas microautophagy-like processes in fungi are involved in selective organelle degradation. In the case of macroautophagy, the cargoes are sequestered within a unique double-membrane cytosolic vesicle, an autophagosome. Sequestration can be either nonspecific, involving the engulfment of bulk cytoplasm, or selective, targeting specific cargoes such as organelles or invasive microbes. The autophagosome is formed by expansion of the phagophore, but the origin of the membrane is unknown. Fusion of the autophagosome with an endosome (not shown) or a lysosome provides hydrolases. Lysis of the autophagosome inner membrane and breakdown of the contents occurs in the autolysosome, and the resulting macromolecules are released back into the cytosol through membrane permeases. CMA involves direct translocation of unfolded substrate proteins across the lysosome membrane through the action of a cytosolic and lysosomal chaperone hsc70, and the integral membrane receptor LAMP-2A (lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2A).

Figure 2. A simplified model of autophagy regulation.

Macroautophagy occurs at a basal level and can be induced in response to environmental signals including nutrients and hormones, and also microbial pathogens. The best-characterized regulatory pathway includes a class I PI3K and TOR, which act to inhibit autophagy, although the mechanism is not known. A class III PI3K is needed for activation of autophagy. TOR activity is probably regulated in part through feedback loops to prevent insufficient or excessive autophagy. For example, p70S6 kinase is a substrate of TOR that may act to limit TOR activity, ensuring basal levels of autophagy that are critical for homeostasis. Proteins in green and pink are stimulatory and inhibitory for autophagy, respectively. Dashed lines indicate possible regulatory effects.

Both the non-selective and selective nature of autophagy, as well as basal and induced levels, are important in regard to the role of this process in human health and disease. Perhaps the most fundamental point is that either too little or too much autophagy can be deleterious, a complexity seen in its dual role in cytoprotection and cell death. With the identification of many autophagy-related (ATG) genes and improved methods for monitoring this process, future research on this topic should continue to progress.

Autophagy in cell survival and cell death

The pro-survival function of autophagy has been demonstrated at the cellular and organismal level in different contexts, including during nutrient and growth factor deprivation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, development, microbial infection, and diseases characterized by the accumulation of protein aggregates8–11. This pro-survival function is generally believed to be adaptive, but, in the context of cancer, is potentially maladaptive12. Metabolic stress is a common feature of the tumour microenvironment and most chemotherapeutic agents induce cellular stress. Thus, an area of intense investigation is whether autophagy-dependent survival should be blocked in these settings to promote tumour-cell death13.

An apparent conundrum is that autophagy acts both in cytoprotection and in cell death. In response to most forms of cellular stress, autophagy plays a cytoprotective role, because ATG gene knockdown/knockout accelerates rather than delays cell death9,11. However, in certain settings where there is uncontrolled upregulation of autophagy (for example, overexpression of the autophagy protein Beclin 1 in mammalian cells14, and Atg1 overexpression in Drosophila15), autophagy can lead to cell death, possibly through activating apoptosis15 or possibly as a result of the inability of cells to survive the non-specific degradation of large amounts of cytoplasmic contents. Notably, many examples of ATG-gene-dependent cell death occur in cells deficient in apoptosis9, suggesting that autophagy, as a route to cell death, may be a choice of last resort. One general caveat to these types of studies is that the overexpression or knockout of a single ATG gene could have unknown indirect effects beyond autophagy.

Autophagic programmed cell death was originally described in tissues undergoing active development. Yet, not only is there no evidence that ATG gene inhibition prevents this death, but the opposite may be true. Nematodes lacking bec-1, the Caenorhabditis elegans orthologue of ATG6/beclin 1, and mice lacking beclin 1 or atg5 display increased numbers of apoptotic cells in embryonic tissues, arguing against a requirement for the autophagic machinery in developmental programmed cell death16,17. It may, however, be premature to conclude that autophagy deficiency results in the increased generation of apoptotic cells during development, because the ATG machinery also has a role in the heterophagic removal of apoptotic corpses16. In mature animals with tissue-specific ATG gene knockout, there is perhaps clearer evidence of an anti-apoptotic function of autophagy in vivo18–20.

The cross-talk between autophagy, a pathway that functions primarily in cell survival, and apoptosis, a pathway that invariably leads to cell death, is complex. The two pathways are regulated by common factors, they share common components, and each can regulate and modify the activity of the other9,11. Many signals originally studied in the context of apoptosis activation induce autophagy, whereas signals that inhibit apoptosis also inhibit autophagy5–7. Anti-apoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2 family members, inhibit Beclin 114, and pro-apoptotic factors, such as BH3-only proteins, disrupt this inhibitory interaction and thereby activate autophagy21. Another link between the autophagic machinery and apoptosis is the observation that Atg5 can undergo calpain-mediated cleavage to generate a pro-apoptotic fragment that functions in the intrinsic mitochondrial death pathway22. These examples may represent only the tip of the iceberg, as we clearly are just beginning to understand the intricate molecular interplay between autophagy and apoptosis. However, it does seem likely that the coordinated regulation of ‘self-digestion’ by autophagy and ‘self-killing’ by apoptosis may underlie diverse aspects of development, tissue homeostasis and disease pathogenesis.

Neurodegeneration

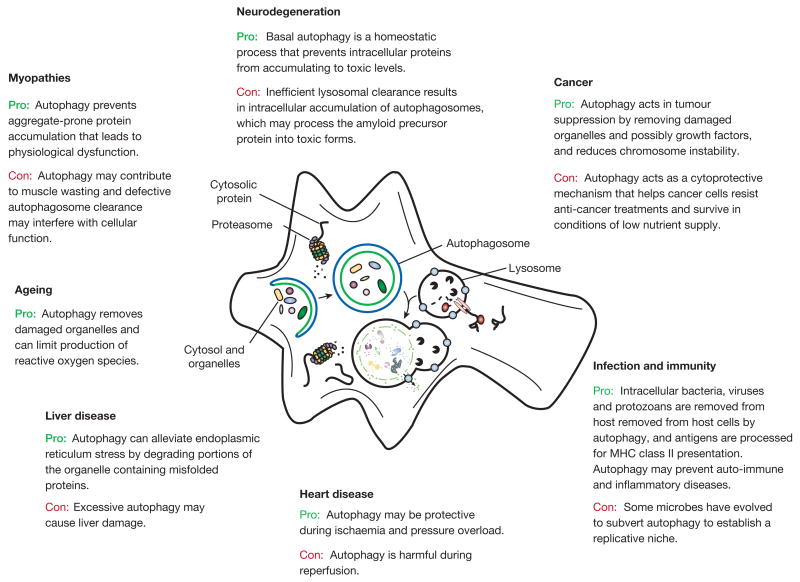

Growing evidence reveals that alterations in autophagy occur in many human diseases. Here we discuss only those disorders in which autophagy malfunction has been shown to contribute to their pathogenesis (Fig. 3). As mentioned above, autophagy occurs at basal, constitutive levels and recent studies have highlighted the importance of basal autophagy in intracellular quality control. The demand for basal autophagy differs among tissues; it is particularly important in the liver and in other tissues where the cells, such as neurons and myocytes, do not divide after differentiation18,19,23–25. In contrast to conventional atg5, atgatg5 and beclin 1 knockout mice, which die during embryogenesis or the neonatal period1,23,26–29, those with neural-tissue-specific knockouts of these genes survive the postnatal starvation period. However, these mice develop progressive motor deficits and display abnormal reflexes, and ubiquitin-positive inclusion bodies accumulate in their neurons18,19. Although the levels of autophagosomes detected in neurons are very low under normal and even starvation conditions30,31, these studies strikingly show that constitutive turnover of cytosolic contents by autophagy is indispensable, even in the absence of expression of any disease-associated mutant proteins.

Figure 3. The role of autophagy in human disease.

Degradation, in particular through autophagy and the proteasome, is important in cellular physiology. Autophagy can act as a cytoprotective mechanism to prevent various diseases, and dysfunctional autophagy leads to pathology. In some cases, however, autophagy can be deleterious; for example, some microbes subvert autophagy for replication, and the cytoprotective action can allow cancer cells to resist anti-cancer treatments.

Despite the important function of basal autophagy in healthy individuals, the requirement for autophagy is even more evident under disease conditions. Recent studies reveal that degradation of disease-related mutant proteins is highly dependent on autophagy, in addition to the ubiquitin–proteasome system. Examples include extended polyglutamine-containing proteins that cause various neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington’s disease and spinocerebellar ataxia, and mutant forms of α-synuclein that cause familial Parkinson’s disease32–34. CMA also participates in wild-type α-synuclein degradation, but mutant forms of α-synuclein block the lysosomal receptor, resulting in general CMA inhibition35. The affected cells attempt to compensate for the CMA blockage by upregulating macroautophagy, which guarantees cell survival but renders the cells more susceptible to stressors4.

Considering all of the available data, there is no doubt that autophagy has a beneficial effect of protecting against neurodegeneration; however, how autophagy can prevent neurodegeneration is not completely understood. One hypothesis is that autophagy eliminates protein aggregates or inclusion bodies, possibly in a directed manner36,37. One possible adaptor is p62/sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1)36. Almost all protein aggregates are decorated with ubiquitin, and SQSTM1 has both LC3-binding (the mammalian homologue of the autophagy-related protein Atg8) and ubiquitin-binding domains, allowing it to mediate the recognition of protein aggregates by a protein (LC3) in the membrane of the forming autophagosome36,38. Furthermore, proper turnover of p62 by autophagy is critical to prevent spontaneous aggregate formation39.

However, direct degradation of aggregates by autophagy is somehow contradictory to the recent hypothesis that the generation of protein aggregates is a protective mechanism40,41. Rather, the primary target of autophagy seems to be diffuse cytosolic proteins, not inclusion bodies themselves, suggesting that inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient cells is an event secondary to impaired general protein turnover18. However, it is still possible that misfolded proteins in soluble or oligomeric states could be preferentially recognized by autophagosomal membranes, which might also be mediated by ubiquitin–p62–LC3 interactions.

Alterations of autophagy have also been observed in Alzheimer’s disease, but in this case the contribution of autophagy may not be as simple as in other types of neurodegeneration. For example, autophagosome-like structures accumulate in dystrophic neurites of Alzheimer’s disease patients and model mice, probably owing to impairment of autophagosome maturation into autolysosomes (Fig. 1)42. Surprisingly, the toxic proteolytic product Aβ can be produced within these partially degraded compartments because the Aβ precursor protein, APP, and the protease responsible for its cleavage, are both present in the endoplasmic reticulum sequestered in these structures42. Therefore, one hypothesis is that impaired autophagic flux provides a novel site for Aβ peptide production.

It is reasonable to assume that autophagy could be a therapeutic target for treatment of these neurodegenerative diseases because of its protective role43. For example, upregulation of autophagy by the regulatory protein kinase complex Target of Rapamycin (TOR) inhibitors such as rapamycin and its analogue CCI-779 protects against neuro-degeneration seen in polyglutamine disease models in Drosophila and mice44. Recently, small-molecule enhancers of rapamycin were identified45. These improve the clearance of mutant huntingtin and α-synuclein, and protect against neurodegeneration in a fruit-fly Huntington’s disease model. Importantly, the effects of small-molecule enhancers of rapamycin are independent of TOR, making it possible to use them in combination with rapamycin for therapeutic purposes. In any attempt at manipulating autophagy therapeutically, however, it is important to take into account the dynamic nature of the changes that occur in the autophagic system during the pathogenic course of a disease (Fig. 3).

Innate and adaptive immunity

The disposal of intracellular organisms, similar to cellular organelles, represents a steric challenge for cellular degradative pathways that may be uniquely met by autophagy. The same autophagic machinery used to selectively capture cellular organelles is used for the selective delivery of microorganisms to lysosomes in a process termed xenophagy46. In mammals (and perhaps other metazoan organisms), the role of autophagy in antimicrobial defence probably extends beyond the direct elimination of pathogens. A growing number of studies indicate a role for autophagy in delivery of microbial antigenic material to the innate and adaptive immune system, as well as in maintaining lymphocyte homeostasis47,48 (Fig. 3).

Xenophagy can target extracellular bacteria that invade intracellularly, bacteria and parasites that reside in the cytosol, phagosomes, or pathogen-containing vacuoles, as well as newly synthesized virions during their exit from the nucleus through the cytoplasm47,49. The cell biology of xenophagy is less well-studied than classical autophagy and despite the overlap in molecular components required for the two processes, it is not yet clear whether the membranes engulfing microorganisms have a biogenesis similar or different to that of classical autophagosomes. Pathogen-containing LC3-positive compartments can be considerably larger than classical autophagosomes consisting exclusively of cellular constituents47, indicating a plasticity of the autophagic process that permits it to adapt to the need to engulf microbes that are larger than its own organelles, a capacity that reflects the unique mechanism of autophagosome formation (Fig. 1). Although xenophagy appears to be primarily a selective form of autophagy, almost nothing is known about how microbes (or membranous compartments containing microbes) are recognized by the autophagic machinery.

Beyond its direct role in pathogen elimination, autophagy may exert cytoprotective functions in infected cells and also mediate trafficking events required for innate and adaptive immunity. In the case of certain RNA viral infections, autophagy is required for the delivery of viral nucleic acids to the endosomal toll-like receptor TLR7, and subsequent activation of type I interferon signalling47. The autophagic machinery is also used for the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II presentation of certain endogenously synthesized viral antigens47. Not only does the autophagic machinery function in innate and adaptive immunity, but several innate and adaptive immune mediators involved in intracellular pathogen control stimulate autophagy47.

Given the diverse roles of autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity, it is not surprising that many pathogens have devised strategies to outsmart autophagy. Some intracellular bacteria and viruses co-opt the autophagic machinery to use Atg protein-dependent dynamic membrane rearrangements to their own replicative advantage49,50. More commonly, successful intracellular pathogens modulate the signalling pathways that regulate autophagy or block the membrane trafficking events required for autophagy-mediated pathogen delivery to the lysosome47. Notably, in certain settings, microbial evasion of autophagy may be essential for microbial pathogenesis. For example, fatal herpes simplex virus encephalitis requires inhibition of the Beclin 1 autophagy protein by a virus neurovirulence protein51. Thus, the selective disruption of interactions between microbial virulence factors and their targeted host autophagy proteins may help reduce infection-induced pathology.

Other postulated roles of autophagy in immunity that warrant further scientific attention include T-cell homeostasis, central and peripheral tolerance induction, and the prevention of unwanted inflammation and autoimmunity47. We also note that several recent genome-wide scans have uncovered strong associations between a non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism in the autophagy gene ATG16L1 as well as in the autophagy-stimulatory immunity-related GTPase IRGM, and susceptibility to Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory disease of the intestine13. These associations suggest an intriguing potential role for autophagy deregulation in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. However, it is not known whether the ATG16L variant is defective in autophagy function and whether this genetic association is indicative of a mechanistic link between autophagy impairment and Crohn’s disease pathogenesis. Studies in targeted mutant mice with a knock-in T300A mutation in ATG16L1 should help clarify these important questions.

Cancer

Cancer is one of the first diseases genetically linked to autophagy malfunction12,13. The ATG gene beclin 1 is monoallelically deleted in 40–75% of cases of human breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer. This is probably mechanistically important in tumorigenesis, because mice with heterozygous disruption of beclin 1 have decreased autophagy and are more prone to the development of spontaneous tumours including lymphomas, lung carcinomas, hepatocellular carcinomas, and mammary precancerous lesions27,29. Further, immortalized kidney and mammary epithelial cells derived from beclin 1 heterozygous-deficient mice are more tumorigenic when transplanted in vivo. Other components that enhance the autophagic activity of the Beclin 1/class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) complex, including ultraviolet irradiation resistance-associated gene (UVRAG), Ambra1 and Bif-1 may also play a role in cell growth control and/or tumour suppression26,28. In animal models, additional ATG genes including atg4c also exert tumour suppressor effects52, suggesting that tumour suppression may be a shared property of autophagy proteins that act at different steps of the pathway (Fig. 3). Beyond a role for ATG genes in tumour suppression, there is accumulating evidence that autophagy signalling regulation is tightly linked to oncogenic signalling. Several commonly activated oncogenes (for example, those encoding class I PI3K, PKB, TOR, Bcl-2) inhibit autophagy, whereas commonly mutated or epigenetically silenced tumour suppressor genes (such as those encoding p53, PTEN, DAPk, TSC1/TSC2) stimulate autophagy5.

These genetic links between defects in autophagy regulation or execution and cancer suggest that autophagy is a true tumour suppressor pathway. However, the mechanisms by which it functions in tumour suppression remain largely undetermined. Autophagy may directly regulate cell growth, functioning as a brake to prevent cells from inappropriately dividing in the absence of appropriate trophic support (even though it may promote cell survival in this setting)13. The increased frequency of mitochondrial DNA mutations in autophagy-deficient yeast suggests that mitochondrial turnover mediated by basal autophagy may prevent genotoxic stress and DNA damage12,13. Indeed, recent studies strikingly reveal that both beclin 1 and atg5 function as ‘guardians’ of the cellular genome. Immortalized epithelial cells with mono-allelic or bi-allelic loss of beclin 1 or atg5, respectively, display increased DNA damage, gene amplification, and aneuploidy, especially during ischaemic stress, in parallel with increased tumorigenicity12. It is not yet known how autophagy deficiency compromises genomic stability.

A seeming paradox is that autophagy, a pathway that functions primarily in cell survival, also functions in tumour suppression (Fig. 3), but two hypotheses have recently been proposed to explain this paradox12. First, when tumour cells cannot die by apoptosis upon exposure to metabolic stress, autophagy may prevent death by necrosis, a process that might exacerbate local inflammation and thereby increase tumour growth rate. Second, as noted above, even though autophagy promotes cell survival in the setting of metabolic stress in the tumour microenvironment, it acts concurrently to prevent genomic instability. An additional possibility is that despite its pro-survival effects, autophagy activation during metabolic stress (and high density conditions) prevents cell growth13. Although the pro-survival effects of autophagy may often be counterbalanced by its tumour suppressor effects, an area of growing interest is the potential contribution of these pro-survival effects to tumour cell resistance to chemotherapy; recent studies have shown that genetic or pharmacological inhibition of autophagy enhances cytoxicity of cancer chemotherapeutic agents53,54. Consequently, clinical trials are in progress (based on studies in mouse models55) to disrupt autophagic degradation to maximize the effects of cancer cytotoxic agents. Thus, much as in neurodegenerative and cardiac diseases, it may be necessary to differentially target autophagy in a context-specific and disease-stage-specific manner; autophagy augmentation may be effective in preventing tumour formation and progression, whereas autophagy inhibition may be helpful in promoting tumour regression.

Ageing and longevity

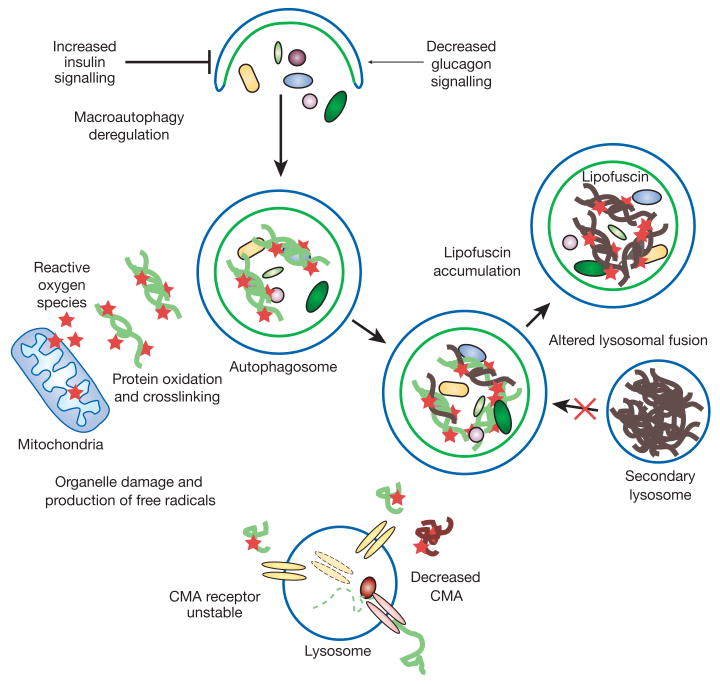

A common characteristic of all ageing cells is the accumulation of damaged proteins and organelles, even in the absence of any mutations that predispose the cells to a pathogenic phenotype such as aggregate-prone mutant proteins (Fig. 4). As discussed above, these deposits of altered components are particularly detrimental in non-dividing differentiated cells, such as neurons and cardiomyocytes, where the characteristic functional decline with age usually manifests itself sooner than in other cell types. Both macroautophagy and CMA activity decrease with age56,57. In light of the dramatic phenotypes observed in the recently generated genetic mouse models with impaired autophagy18,19,23,24, it is easy to infer that a gradual decrease in autophagic activity with age could play a major role in the functional deterioration of ageing organisms. Conversely, caloric restriction, the only intervention known to slow down ageing, seems to improve autophagy induction, possibly owing to lower levels of insulin, an autophagy inhibitor (Fig. 2). Current efforts to prevent or restore the decline in macroautophagy with age are aimed at reproducing the observed beneficial effect of caloric restriction on this pathway through the use of anti-lipolytic drugs (that mimic the starvation state induced by caloric restriction)58.

Figure 4. Autophagy and ageing.

Defective lysosomal function has been reported in almost all tissues of ageing organisms, from nematode worms to mammals, and both macroautophagy and CMA activity decrease with age56. Problems in the regulation and execution of macroautophagy contribute to its functional decline during ageing57. Upregulation of macroautophagy by increased levels of glucagon in serum (that is, between meals) is lost in older organisms, possibly owing to persistently enhanced basal activity of the insulin receptor in response to the higher content of reactive oxygen species in ageing cells59. Also, accumulation of undigested material (lipofuscin) inside secondary lysosomes (for example, autolysosomes) interferes with their ability to fuse with autophagosomes and to degrade their cargo. Changes with age in the lysosomal membrane make the CMA receptor unstable. The age-dependent decrease in the levels of this receptor is responsible for low CMA activity in older organisms60. Some predicted consequences of the decline in autophagy with age are the inefficient clearance of damaged components, a poor response to stress, and a possible precipitating effect on disease.

Outlook

In the past decade there has been a tremendous advance in our knowledge about the molecular mechanism of macroautophagy, including the identification of many of the components of the protein machinery. By comparison, our understanding of regulation, particularly the complex interplay of multiple stimulatory and inhibitory inputs, is relatively limited. To manipulate autophagy for therapeutic purposes, especially considering its dual capacity in cytoprotection and cell death, we need to improve our understanding of the various regulatory pathways.

In contrast to the rapid advance in the molecular dissection of macroautophagy and growing information about its regulation and its pathophysiological relevance, our understanding of other forms of autophagy is still limited. Critical molecular players have been identified for CMA, but it is clear, by comparison with other membrane translocation systems, that other regulatory components are yet to be discovered. The current available information about microautophagy is even more limited and the absence of reliable markers or assays to track this process has prevented any connection of microautophagic changes with physiological or pathological conditions.

Although starvation or stress adaptation is an evolutionarily conserved function of autophagy under physiological conditions, the degradation of intracellular components may be a more important function when considering the role of autophagy in disease. One area of future interest is to study how autophagy functions in preventing neurodegeneration, although at present we do not know the direct cause of the toxicity of neuropeptides such as Aβ and α-synuclein. In addition, we need to understand the issue of functional autophagy serving a protective role, as opposed to compromised autophagy and the accompanying accumulation of cytosolic autophagosomes, which contributes to pathogenesis in neurodegeneration, liver disease and myopathies, because induction of autophagy in these latter situations can exacerbate the disease pathology. Similarly, we should carefully consider the type and progression of diseases such as cancer when attempting to determine whether autophagy inhibition or stimulation is likely to be beneficial. To understand immunity better, it will be important to identify the mechanisms by which autophagy is activated in response to microbial invasion, the targets that allow specific recognition of intracellular pathogens, and the roles of autophagy in immune cell function.

One of the current challenges in the study of autophagy in ageing is that most of the genetic mouse models with impaired autophagy do not reproduce the main characteristics of the ageing-dependent changes. In these models there is complete blockage of autophagy and this blockage is present from birth. The recent introduction of conditional knockout mice should help in part to overcome this problem, because these make it possible to compare the consequences of impaired autophagy from birth, when compensatory mechanisms are likely to be activated, with that occurring in the adult organism.

Thus, although tremendous advances have been made in our understanding of autophagy, many unanswered questions remain. A fuller understanding of all types of autophagy is necessary before we can hope to manipulate these pathways to treat human disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NCI, NIA, NIAID, NIGMS) the American Cancer Society, the Ellison Medical Foundation, Grants-in-Aid Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and the Toray Science Foundation.

References

- 1.Kuma A, et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizushima N, Klionsky DJ. Protein turnover via autophagy: implications for metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:19–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klionsky DJ. The molecular machinery of autophagy: unanswered questions. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:7–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massey AC, Zhang C, Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy in aging and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2006;73:205–235. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)73007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Botti J, Djavaheri-Mergny M, Pilatte Y, Codogno P. Autophagy signaling and the cogwheels of cancer. Autophagy. 2006;2:67–73. doi: 10.4161/auto.2.2.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gozuacik D, Kimchi A. Autophagy and cell death. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;78:217–245. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)78006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meijer AJ, Codogno P. Signalling and autophagy regulation in health, aging and disease. Mol Aspects Med. 2006;27:411–425. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Eating the endoplasmic reticulum: quality control by autophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine B, Yuan J. Autophagy in cell death: an innocent convict? J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2679–2688. doi: 10.1172/JCI26390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lum JJ, DeBerardinis RJ, Thompson CB. Autophagy in metazoans: cell survival in the land of plenty. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:439–448. doi: 10.1038/nrm1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maiuri C, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nature Rev Cancer. 2007;7:961–967. doi: 10.1038/nrc2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pattingre S, et al. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell. 2005;122:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott RC, Juhász G, Neufeld TP. Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu X, et al. Autophagy gene-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells during embryonic development. Cell. 2007;128:931–946. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takacs-Vellai K, et al. Inactivation of the autophagy gene bec-1 triggers apoptotic cell death in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1513–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hara T, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komatsu M, et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pua HH, Dzhagalov I, Chuck M, Mizushima N, He YW. A critical role for the autophagy gene Atg5 in T cell survival and proliferation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:25–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maiuri MC, et al. Functional and physical interaction between Bcl-XL and a BH3-like domain in Beclin-1. EMBO J. 2007;26:2527–2539. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yousefi S, et al. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:1124–1132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komatsu M, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakai A, et al. The role of autophagy in cardiomyocytes in the basal state and in response to hemodynamic stress. Nature Med. 2007;13:619–624. doi: 10.1038/nm1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komatsu M, et al. Essential role for autophagy protein Atg7 in the maintenance of axonal homeostasis and the prevention of axonal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14489–14494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701311104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fimia GM, et al. Ambra1 regulates autophagy and development of the nervous system. Nature. 2007;447:1121–1125. doi: 10.1038/nature05925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qu X, et al. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1809–1820. doi: 10.1172/JCI20039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi Y, et al. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nature Cell Biol. 2007;9:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ncb1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ, Heintz N. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15077–15082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436255100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Matsui M, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1101–1111. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nixon RA, et al. Extensive involvement of autophagy in Alzheimer disease: an immuno-electron microscopy study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:113–122. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez-Vicente M, Cuervo AM. Autophagy and neurodegeneration: when the cleaning crew goes on strike. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:352–361. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubinsztein DC. The roles of intracellular protein-degradation pathways in neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:780–786. doi: 10.1038/nature05291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubinsztein DC, et al. Autophagy and its possible roles in nervous system diseases, damage and repair. Autophagy. 2005;1:11–22. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.1.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, Sulzer D. Impaired degradation of mutant α-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Science. 2004;305:1292–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.1101738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjørkøy G, et al. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:603–614. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwata A, Riley BE, Johnston JA, Kopito RR. HDAC6 and microtubules are required for autophagic degradation of aggregated huntingtin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40282–40292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508786200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pankiv S, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komatsu M, et al. Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell. 2007;131:1149–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, Segal MR, Finkbeiner S. Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature. 2004;431:805–810. doi: 10.1038/nature02998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka M, et al. Aggresomes formed by α-synuclein and synphilin-1 are cytoprotective. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4625–4631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu WH, et al. Macroautophagy—a novel β-amyloid peptide-generating pathway activated in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:87–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubinsztein DC, Gestwicki JE, Murphy LO, Klionsky DJ. Potential therapeutic applications of autophagy. Nature Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:304–312. doi: 10.1038/nrd2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ravikumar B, et al. Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nature Genet. 2004;36:585–595. doi: 10.1038/ng1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarkar S, et al. Small molecules enhance autophagy and reduce toxicity in Huntington’s disease models. Nature Chem Biol. 2007;3:331–338. doi: 10.1038/nchembio883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levine B. Eating oneself and uninvited guests: autophagy-related pathways in cellular defense. Cell. 2005;120:159–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levine B, Deretic V. Unveiling the roles of autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity. Nature Rev Immunol. 2007;7:767–777. doi: 10.1038/nri2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmid D, Münz C. Innate and adaptive immunity through autophagy. Immunity. 2007;27:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang J, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy and human disease. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1837–1849. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.15.4511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kirkegaard K, Taylor MP, Jackson WT. Cellular autophagy: surrender, avoidance and subversion by microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:301–314. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orvedahl A, et al. HSV-1 ICP34.5 confers neurovirulence by targeting the Beclin 1 autophagy protein. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mariño G, et al. Tissue-specific autophagy alterations and increased tumorigenesis in mice deficient in Atg4C/autophagin-3. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18573–18583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abedin MJ, Wang D, McDonnell MA, Lehmann U, Kelekar A. Autophagy delays apoptotic death in breast cancer cells following DNA damage. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:500–510. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carew JS, et al. Targeting autophagy augments the anticancer activity of the histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA to overcome Bcr-Abl-mediated drug resistance. Blood. 2007;110:313–322. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amaravadi RK, et al. Autophagy inhibition enhances therapy-induced apoptosis in a Myc-induced model of lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:326–336. doi: 10.1172/JCI28833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cuervo AM, et al. Autophagy and aging: the importance of maintaining “clean” cells. Autophagy. 2005;1:131–140. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.3.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Del Roso A, et al. Ageing-related changes in the in vivo function of rat liver macroautophagy and proteolysis. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:519–527. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(03)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bergamini E. Targets for antiageing drugs. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2005;9:77–82. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hildebrandt W, et al. Effect of thiol antioxidant on body fat and insulin reactivity. J Mol Med. 2004;82:336–344. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kiffin R, et al. Altered dynamics of the lysosomal receptor for chaperone-mediated autophagy with age. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:782–791. doi: 10.1242/jcs.001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]