Abstract

In addition to the revascularization and glycemic management interventions assigned at random, the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) design includes the uniform control of major coronary artery disease risk factors, including dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, central obesity, and sedentary lifestyle. Target levels for risk factors were adjusted throughout the trial to comply with changes in recommended clinical practice guidelines. At present, the goals are low-density lipoprotein cholesterol <2.59 mmol/L (<100 mg/dL) with an optional goal of <1.81 mmol/L (<70 mg/dL); plasma triglyceride level <1.70 mmol/L (<150 mg/dL); blood pressure level <130 mm Hg systolic and <80 mm Hg diastolic; and smoking cessation treatment for all active smokers. Algorithms were developed for the pharmacologic management of dyslipidemia and hypertension. Dietary prescriptions for the management of glycemia, plasma lipid profiles, and blood pressure levels were adapted from existing clinical practice guidelines. Patients with a body mass index >25 were prescribed moderate caloric restriction; after the trial was under way, a lifestyle weight-management program was instituted. All patients were formally prescribed both endurance and resistance/flexibility exercises, individually adapted to their level of disability and fitness. Pedometers were distributed as a biofeedback strategy. Strategies to achieve the goals for risk factors were designed by BARI 2D working groups (lipid, cardiovascular and hypertension, and nonpharmacologic intervention) and the ongoing implementation of the strategies is monitored by lipid, hypertension, and lifestyle intervention management centers.

The clustering of major coronary artery disease (CAD) risk factors, such as dyslipidemia and hypertension, contributes to the high incidence of CAD and increased cardiovascular mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.1,2 Smoking (an independent CAD risk factor for type 2 diabetes3–5), low levels of physical activity,6,7 and central obesity8 interact with the major risk factors to compound this risk. The uniform management of all CAD risk factors in all randomized patients has been an important goal of the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) trial since its inception. The importance of aggressive CAD risk-factor control in patients with type 2 diabetes has been strengthened by the results of additional studies and key clinical practice guidelines9–13 that support this approach. Interventions of both pharmacotherapy and lifestyle modification are part of the management of CAD risk factors. In BARI 2D, the patients receive coordinated care provided by both a diabetologist and a cardiologist in order to reach predetermined treatment goals and attainment strategies that were delineated by working groups before the study began. Protocol adjustment according to evolving clinical practice recommendations, as well as adherence to the protocol, is ensured through monitoring by clinical management centers and semiannual review by the BARI 2D Steering Committee. In this article, we describe the rationale for choosing the treatment goals, strategies, implementation, and monitoring patterns comprising a “best practice” model, aimed at uniformly controlling CAD risk factors in BARI 2D participants.

Management of Dyslipidemia

Treatment goals

The aggressive treatment of unhealthy plasma lipid levels in individuals with diabetes is now widely accepted,9,10 given the high risk of CAD events and clinical trial evidence of benefit. Both the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) fractions are important to address,14 and the BARI 2D protocol is designed with these twin foci. The evidence on which these guidelines are established is limited but persuasive. There is little doubt that total and LDL cholesterol values predict CAD events in men15 and women,16 independently of other major risk factors. A series of subgroup analyses in patients with diabetes from the major trials of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) show benefits in patients with diabetes similar to those seen in the general population, in both primary17,18 and secondary19–21 end points. The results of the Heart Protection Study (HPS)13 and the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS),22 which were published after BARI 2D recruitment was well under way, provide further evidence for the primary use of statins in most patients with diabetes. Elevated plasma triglyceride concentrations, the hallmark of the specific dyslipidemia in diabetes, have also been strongly implicated as a major CAD risk factor in patients with type 2 diabetes.23 The National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) also recognizes the importance of the dyslipidemia associated with glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, with its secondary focus on the metabolic syndrome and non–high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol.10 Interventions directed mainly at VLDL or triglyceride values, such as gemfibrozil therapy in the Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial (VA-HIT), have also been reported to have generally positive results,24 although these results were not always significant among patients with diabetes because of their small number in these trials.25 One angiography study, the Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study (DAIS), which tested fenofibrate and targeted patients with type 2 diabetes, also reported positive results.26

Because all BARI 2D participants have both type 2 diabetes and CAD, BARI 2D has adopted a primary goal level of LDL cholesterol <2.59 mmol/L (<100 mg/dL) for all participants and a secondary goal level of triglycerides <2.26 mmol/L (<200 mg/dL) or non-HDL cholesterol <3.37 mmol/L (<130 mg/dL) in accordance with the NCEP ATP III guidelines.10 Consistent with the NCEP guidelines, no goal level for HDL cholesterol was set. These goals, however, do not preclude investigators treating to lower targets, should that be their preference. It was anticipated that treatment goals would be revised as national guidelines and policy changed. Accordingly, in April 2004, the triglyceride goal was lowered to 1.70 mmol/L (150 mg/dL),9 and in October 2004, investigators were encouraged, but not mandated, to consider an LDL cholesterol goal of <1.81 mmol/L (<70 mg/dL) and to achieve a decrease in LDL cholesterol ≥30% from baseline in all newly treated participants.27

Lipid management protocols

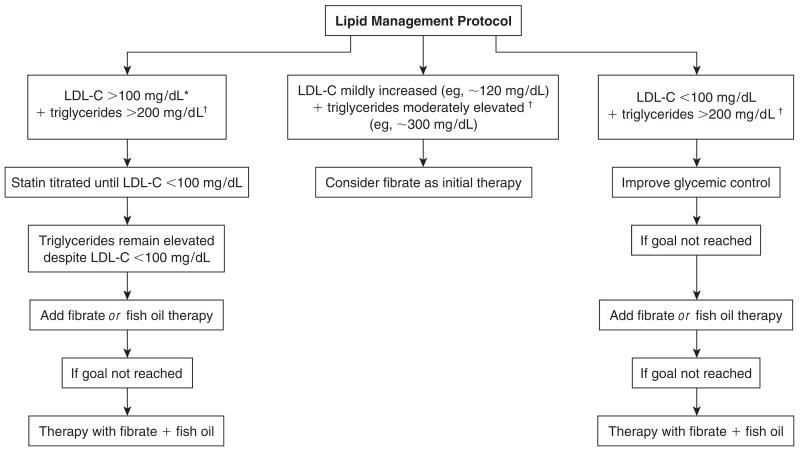

To achieve these lipid goals, early introduction of statin therapy is encouraged and expected by the 3-month visit, at the latest, unless contra-indicated (eg, allergy, prior side effects, liver disease). Figure 1 depicts an overview of the BARI 2D lipid management protocol. Fenofibrate or gemfibrozil therapy is also acceptable as first-line drug therapy if there is only modest LDL cholesterol elevation or optimal LDL cholesterol values together with hypertriglyceridemia and/or low levels of HDL cholesterol. Other drug classes in addition to statins are also encouraged, as needed, including bile acid sequestrants and, since its availability in 2004, the cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe. Once the LDL goal level is achieved, triglyceride and non–HDL cholesterol lowering is encouraged by means of a variety of approaches, including lifestyle modification, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation (fish oil), and where appropriate, combination statin–fibric acid therapy.10 Niacin therapy, however, is discouraged because of its direct conflict with the study’s insulin sensitization compared with insulin provision hypothesis,28 despite acceptance by many of the group that niacin has a place as a therapeutic agent for dyslipidemia in some patients with type 2 diabetes.

Figure 1.

Overview of the lipid management protocol in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) study. LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. To convert conventional units to SI units, multiply by 0.0259 for LDL-C and by 0.0113 for triglycerides. *Optional LDL goal of <1.81 mmol/L (<70 mg/dL) as of October 2004; †triglyceride goal reduced to <1.70 mg/dL (<150 mg/dL) in April 2004. If triglycerides are substantially elevated (eg, >600 mg/dL), statin therapy is unlikely to be successful and fibrate therapy may be a more appropriate initial choice.

Monitoring levels and policies

To encourage consistent compliance with the BARI 2D protocol and to enhance the attainment of trial goals, a Lipid Management Center was established. This center comprises a responsible investigator, a part-time research assistant, a coordinating center analyst, and a facilitator. These individuals meet every 2 months to review monitoring tables produced by the analyst that describe the mean levels, percentage of participants at goal, and lipid distributions at each periodic data freeze. These values represent those reported to the coordinating center from the local sites as measured by local laboratories. The values analyzed annually by the core laboratory are not used for clinical case monitoring. The actions taken by the field centers for each patient whose plasma lipid values remain above goal are also reviewed, as are detailed listings of all clinic visits for patients whose values are above the established monitoring level. This monitoring level (initially an LDL cholesterol level of 3.37 mmol/L [130 mg/dL] and a triglyceride value of 4.52 mmol/L [400 mg/dL] at or after the 6-month visit) is used to trigger further follow-up with a particular study site. If the database suggests that less than optimal intervention is being adopted, the investigators responsible for participants whose plasma lipid values are above the monitoring goal are sent an e-mail letter seeking further information and offering appropriate advice. In addition, every 2 months, field centers with ≥10 participants with ≥6 months of follow-up receive a graphic display of how their site compares to others (whose identities are masked) in attaining lipid goals. This graph is accompanied by a listing of all of the center’s participants whose lipid levels are above goal to encourage and facilitate further review of the management of these cases. Monitoring is also conducted at the center level, and each center with a low ranking (at the time of writing, this was defined as centers with a third or more of participants above goal at ≥6 months) is reviewed in depth. Where necessary, further follow-up with the site investigators is made.

The treatment goals, drug management protocols, and monitoring levels and policies were developed by the lipid management group (LMG), a group of investigators who meet every 6 months at the steering committee meetings and more frequently by conference call or e-mail if needed. An updated report is presented every 6 months, including any additional monitoring analyses requested by the group. The impact of new developments in lipid management on BARI 2D are discussed at these meetings. To date, these new developments have included publication of ATP III guidelines10 and a subsequent report27; the results of newly completed trials, eg, the HPS13; and the release of new drugs/preparations, eg, ezetimibe. The LMG decides when to recommend protocol changes in response to these developments and also develops operations memos when appropriate. The LMG also reviews the treatment and monitoring goals with the intent of steadily improving performance at all BARI 2D sites. Since the original LMG recommendations were put in place, the LMG lowered the monitoring levels for LDL cholesterol to 2.98 mmol/L (115 mg/dL) and triglycerides to 3.39 mmol/L (300 mg/dL) at the April 2003 meeting, and 1 year later (April 2004) further lowered the triglyceride monitoring level to 2.83 mmol/L (250 mg/dL). As more patients achieve and maintain their LDL cholesterol goals, it is anticipated that the LMG will further lower the triglyceride goal and monitoring level.

Management of Hypertension

Treatment goals

Approximately 50% of patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes will have hypertension,29 which will account for 35%–75% of diabetes-related cardiovascular and renal complications. Blood pressure control, with lower target blood pressure levels in patients with hypertension and diabetes than in those without diabetes, has been recommended as an important strategy to prevent or retard the progression of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.30 Incorporation of recently recommended guidelines for hypertension treatment is a cornerstone of medical care for patients with type 2 diabetes, who are at very high risk for early cardiac mortality. As recommended by the seventh Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VII),31 BARI 2D defined hypertension as a blood pressure level >130 mm Hg systolic or >80 mm Hg diastolic; these levels are considered the targets for nonpharmacologic and/or pharmacologic treatment.

At study entry, patients were questioned about history, duration, and treatment of hypertension. Blood pressure was measured using an appropriately sized cuff after 5 minutes of rest and recorded to the nearest 2 mm Hg for systolic and diastolic levels. Blood pressure was recorded in the supine, sitting, and standing positions because patients with type 2 diabetes may have decreased baroreceptor sensitivity and/or autonomic neuropathy, resulting in blood pressures that vary with body position. Sitting blood pressure is regarded as the measurement for diagnosis and treatment in BARI 2D.

Treatment strategies

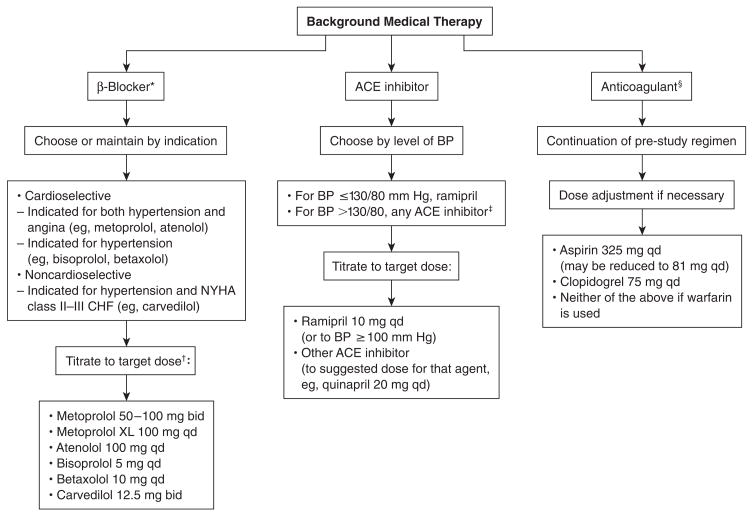

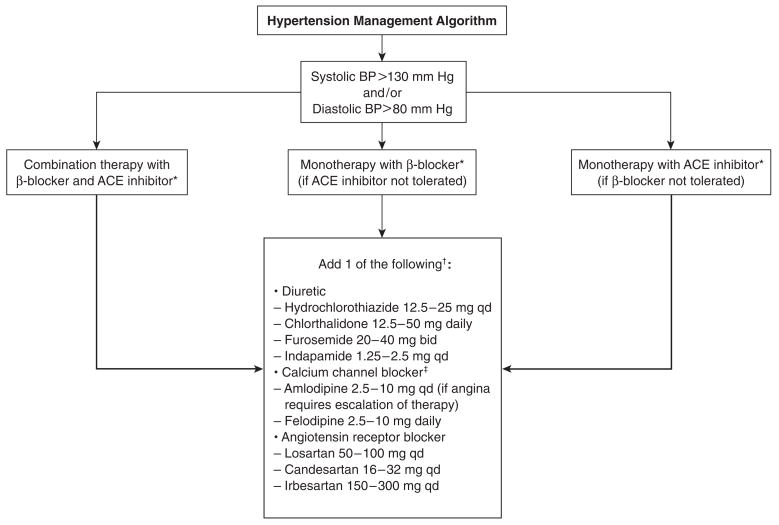

All patients in BARI 2D received counseling on lifestyle modification on enrollment in the study. This information includes advice on (1) smoking cessation; (2) dietary intervention, with the goals of weight reduction, reduction of sodium intake, and modification of alcohol intake; and (3) increased physical activity. Algorithms for the treatment strategies used in BARI 2D are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Background medical therapy in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) study. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; BP = blood pressure; CHF = congestive heart failure; NYHA = New York Heart Association; XL = extended release. *Because all patients in BARI 2D have coronary artery disease, β-blockers will be used (per American Diabetes Association recommendations) unless contraindications exist. β-Blockers vary in their indications, thus selection of agent depends on the particular clinical profile of the patient, eg, presence or absence of hypertension, angina, or CHF. †Exceptions: heart rate is ≤60 beats per minute, systolic BP is ≤100 mm Hg, or the maximum tolerated dose is less than the target dose. ‡Unless ramipril is provided through BARI 2D. §Use of 1 anticoagulant only. There have been case reports of INR elevation in patients on warfarin who receive omega-3 fish oils.

Figure 3.

Overview of the hypertension management algorithm in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) study. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; BP = blood pressure. *Ensure titration guidelines are met for ACE inhibitors and β-blockers. Target doses of β-blockers can be exceeded to “maximum” doses providing heart rate remains ≥60 beats per minute. †If an additional agent is necessary, choose from a central or peripheral α-blocker or a direct vasodilator (eg, hydralazine, minoxidil). ‡In ACE-inhibitor monotherapy, diltiazem and verapamil may also be considered.

Failure to achieve a blood pressure level of 130/80 mm Hg or lower after 3 months of nonpharmacologic treatment triggers the addition of pharmacologic treatment in patients not already diagnosed with hypertension and not receiving pharmacologic treatment at the time of BARI 2D enrollment, or modification of such treatment if present at enrollment. Treatment response is assessed at clinic visits every month for the initial 6 months and thereafter every 3 months.

The majority of patients with hypertension in BARI 2D will likely require ≥2 drugs to attain the target blood pressure. In the UKPDS,32 at 9 years of follow-up, >60% of patients assigned to tight blood pressure control required ≥2 drugs to achieve a target blood pressure <150/80 mm Hg, a level substantially higher than the BARI 2D target level. Compared with patients in the UKPDS, for whom diabetes was a new diagnosis, patients in BARI 2D were expected to be older, to have established diabetes, and to have had a longer history of hypertension, increasing the likelihood that they would need multiple antihypertensive drugs.

Numerous recent clinical trials have established the classes of drugs that are effective in reducing blood pressure and cardiac morbidity and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. The UKPDS32 showed that tight blood pressure control with either an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor (eg, captopril) or a β-adrenergic receptor blocker (eg, atenolol) reduces the incidence of microvascular disease, stroke, and heart failure, with a nonsignificant reduction of risk (21%) for myocardial infarction (MI). The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) trial33 indicated that in the subgroup of elderly hypertensive subjects with diabetes, diuretic (thiazide) treatment was associated with a significant reduction in cardiovascular events. In patients with type 2 diabetes and proteinuria, angiotensin receptor blockers are effective blood pressure–lowering agents and may prevent or retard the progression of diabetic nephropathy.34,35

Findings of several trials, such as Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in Diabetes (ABCD) and Fosinopril Versus Amlodipine Cardiovascular Events Randomized Trial (FACET),36 have suggested a higher relative risk of MI associated with calcium channel blockers (ie, nisoldipine and amlodipine) compared with ACE inhibitors (ie, enalapril and fosinopril) despite equipotent ability to lower blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes. Analysis of the subgroups with diabetes in other large clinical trials, however, has not suggested adverse cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes and hypertension who are treated with calcium channel blockers. The Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) study37 and the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial38 demonstrated reduced cardiovascular mortality when calcium channel blockers (ie, felodipine and nitrendipine) were used to treat hypertension in the diabetic subgroups. HOT also demonstrated that the greatest reduction in cardiovascular mortality was experienced in the group randomized to the lowest target blood pressure, eliminating the concern that overaggressive lowering of blood pressure may be harmful for patients with diabetes, particularly those with a history of vascular disease. The Antihy-pertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)39 showed that amlodipine was as effective as chlorthalidone or lisinopril in reducing blood pressure and the incidence of cardiovascular end points. Furthermore, compared with placebo, amlodipine did not increase mortality in patients with diabetes and congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association functional class III or IV) in the Prospective Randomized Amlodipine Survival Evaluation (PRAISE).40 More recently, in the International Verapamil SR and Trandolapril Study (INVEST), verapamil was shown to have benefits similar to those of atenolol in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes and CAD.41

Most patients in BARI 2D will be treated with β-blockers, either as treatment for angina pectoris or as secondary prevention for CAD events. In patients with hypertension, the dose of the β-blocker may be increased to achieve target blood pressure level. Caution is warranted, however, because β-blockers in patients with diabetes may reduce peripheral blood flow (incur or exacerbate claudication symptoms), mask warning signs of hypoglycemia, and/or impair glucose recovery in hypoglycemia. Adding another drug is a more prudent approach in these patients, particularly if the dose of the prescribed β-blocker is at a level that has been shown to provide secondary prevention against CAD.

Monitoring levels and policies

Blood pressure is monitored by the hypertension management center (HMC), which performs the following functions: (1) ensures that all patients enrolled in BARI 2D are on appropriate standard (background) medications as outlined in the BARI 2D Manual of Operations, and (2) monitors systolic and diastolic blood pressures in all patients to ensure that BARI 2D goals (≤130 mm Hg systolic and ≤80 mm Hg diastolic) are attained. The HMC will also assist sites when individual patients are found to have persistently elevated blood pressure and/or the average blood pressure of all patients at a particular site is persistently elevated.

The BARI 2D Coordinating Center forwards data to the HMC to track the blood pressure of all enrolled patients throughout the course of the trial. The coordinating center calculates and tracks both an overall BARI 2D average (and median) systolic and diastolic blood pressure and a center-specific percentage of subjects at goal. The coordinating center forwards to the HMC the systolic and diastolic blood pressure recorded for each patient at each clinic visit and will calculate the mean value of the systolic and diastolic blood pressure for every BARI 2D clinical site every 3 months by visit number. These data are provided to the HMC as a single histogram of all BARI 2D patients across all centers, as separate histograms of all patients within each center, and as a single histogram of the mean systolic and mean diastolic blood pressure levels of each center. Accompanying these histograms are tables of the distribution of the systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels that indicate the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 90th percentile values as well as the percentage of patients who have and have not achieved systolic and diastolic blood pressure goals. Individual patients whose blood pressure levels are above goal levels have their medications reported to the HMC, which makes recommendations regarding case management. The HMC investigates clinical sites with mean/median systolic blood pressure levels >150 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure levels >95 mm Hg diastolic or with 50% of patients above goal to assess the adequacy of treatment for those subjects.

To monitor medications used as background medical therapy and to treat hypertension, all clinical sites use a standardized drug check-off form, which is updated whenever a new drug is introduced into the protocol. The study coordinator at each clinical site will record the initiation and discontinuation dates of each drug used for blood pressure management. These data will be sent to the HMC, which will maintain in its database the drug use history of each BARI 2D patient from entry into the protocol until study completion.

Nonpharmacologic Management

Smoking cessation

Smoking is an independent risk factor for CAD,2 stroke,42 and peripheral vascular disease43 and is additive to type 2 diabetes.2,3,5 Smoking is associated with central adiposity, unfavorable plasma lipid levels, elevated procoagulation factors,5,44 worse plasma glucose control independent of dietary factors,5,45 and increased microvascular complications independent of glucose control and optimal antihypertensive treatment.46 Despite the adverse effects of smoking, approximately 22% of the population of US adults with diabetes continue to smoke.47 Patients with type 2 diabetes are counseled to stop smoking less often than they receive other aspects of preventive care.48 Given the success of smoking cessation programs in patients without diabetes4 and recently in patients with type 2 diabetes,49 it has been suggested that smoking cessation intervention is probably the single most cost-effective intervention for CAD management in this population.48

The principles that guide the smoking cessation intervention in BARI 2D are based on established clinical practice guidelines for the general population.50,51 The recently published guidelines underscore that (1) all tobacco products, not just cigarettes, exact devastating costs on the nation’s health and welfare; (2) for most, tobacco use results in true drug dependence, comparable to that caused by opiates, amphetamines, and cocaine; (3) chronic tobacco use warrants repeated clinical intervention just as do other addictive disorders. There is a positive correlation between the duration of the treatment and its effectiveness. Cessation is targeted in every smoking patient throughout the duration of the BARI 2D study.

Although smoking cessation treatment is included under the nonpharmacologic interventions, ≥1 of the 5 first-line pharmacologic therapies to aid in smoking cessation— bupropion, nicotine gum, nicotine inhaler, nicotine nasal spray, and nicotine patch—is prescribed in the absence of contraindication. It has been determined to be safe to prescribe nicotine for BARI 2D participants except in the presence of recent MI or unstable angina. However, second-line agents (ie, clonidine and nortriptyline) are relatively contraindicated for this population.

Dietary and weight control management

Dietary interventions are essential for the proper management of patients with type 2 diabetes and CAD.52 The specific goals include attaining and maintaining control of glycemia and CAD risk factors as well as prevention and treatment of obesity.53,54 On average, 70% of all patients with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese.8,55 Weight control is essential for control of glycemia, dyslipidemia, and blood pressure in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes.55 Although a normal, ideal body weight is defined as a body mass index of ≤25, attaining a normal body weight in many patients with type 2 diabetes may not be realistic. However, even a small change in body weight (5% to 10%) that is maintained over time may drastically improve glucose control, lipid profile, and blood pressure in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes.53,55

Strategies for BARI 2D include lifestyle changes such as modifications in energy balance, leading to weight loss, and/or changes in intake of specific nutrients.9,54 Individual nutritional needs, personal and cultural preferences, and lifestyle should be taken into account, as well as the individual’s wishes and willingness to change.54

DIET PRESCRIPTION

Since dietary saturated fat and cholesterol are the primary determinants of LDL cholesterol levels in community-dwelling individuals, the American Heart Association (AHA) Step 1 diet is recommended for the patients in BARI 2D. Although certain issues are considered— eg, replacing carbohydrate with monounsaturated fat may reduce glycemia and triglyceridemia while equally reducing LDL cholesterol levels56—ad libitum use of monounsaturated fat should be discouraged because it may promote weight gain.57 However, increased fiber content and special diet combinations leading to increased fiber intake have been shown to have favorable effects on glycemic, lipid, and blood pressure control in patients with and without diabetes as well as to promote weight loss.58

NUTRITION COUNSELING GUIDELINES

The purposes of the dietary consultation for the patients in BARI 2D are (1) to customize the dietary prescription according to the individual patient’s specific medical needs and cultural background and (2) to increase the patient’s nutritional knowledge regarding the prescribed diet. The need for further dietary consultation is prompted by a weight gain of 5% of original body weight; glycosylated hemoglobin >7.0% after maximum pharmacologic treatment (ie, for 2 months in the insulin-sensitizing arm and 1 month in the insulin-providing arm); and/or evidence of worsened glycemic, lipid, or blood pressure control since the previous measurement. BARI 2D provides basic education pamphlets, and additional educational materials are used locally for individualized ethnic and literacy needs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) nonpharmacologic interventions

|

HYPOGLYCEMIA

Specific instructions for the management of hypoglycemia—including description of symptoms as well as the relation among hypoglycemia, food, and activity patterns—are stressed and taught to each BARI 2D participant (Table 1).

STRATEGIES FOR WEIGHT REDUCTION

A lifestyle balance weight control program developed specifically for BARI 2D was designed to enhance uniformity in weight control–specific counseling tools and resources across the BARI 2D clinical sites. Materials were adapted from the Diabetes Prevention Program (www.bsc.gwu.edu/dpp/index.htmlvdoc),59 the National Diabetes Education Program (www.ndep.nih.gov), and the Primary Care Weight Control Project.60 The program is designed to help patients in the BARI 2D study achieve a 10% weight loss in approximately 6 months and is initiated after the 6-month follow-up clinic visit. A moderate caloric restriction goal of 250–500 calories per day less than the patient’s estimated total energy expenditure is recommended. Patients are advised to self-monitor intake of food and beverages as well as physical activity using daily logs (Table 1).

ORLISTAT

Prescription of orlistat (Xenical; Roche Pharmaceuticals, Nutley, NJ) is accepted and encouraged in BARI 2D. Orlistat as a pharmacologic agent produces small amounts of weight loss that have been shown to improve glycemic control and lipid profile, at least in the short term.8,55 However, maintenance of weight loss is improved when follow-up and long-term treatment are provided.8,55

Physical activity management

Regular exercise has been shown to improve blood glucose control, to contribute to weight loss and its maintenance, and to improve overall well-being.6,9 Increased physical activity is helpful in the management and control of hypertension and dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes and has favorable effects on cardiovascular mortality in patients with established CAD.11,61 The question of the type, amount/duration, and intensity of exercise that would be safe and beneficial for patients with type 2 diabetes and established CAD is not entirely resolved. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines9 point out the need, in patients with type 2 diabetes and CAD, for a supervised evaluation of the ischemic response to exercise, ischemic threshold, and propensity for arrhythmia during exercise. In many cases, left ventricular systolic function must be assessed at rest and in response to exercise. Thus, the maximum amount of exercise that is well tolerated and safe should be prescribed. In addition to the precautions taken because of CAD, other aspects of type 2 diabetes (eg, retinopathy, neuropathy, foot disease) must be considered when determining the goals and strategies of exercise in these patients.

TREATMENT STRATEGIES

An individualized exercise prescription written by either a cardiologist or the cardiologist’s designee is given to each BARI 2D participant to assist with clinical management. Whenever possible, patients are referred to a formal cardiac rehabilitation program.

Although the endurance exercises will typically include activities like walking, swimming, or bicycling, each patient in BARI 2D is instructed on flexibility and resistance training exercises through information and illustrations of exercises provided in the BARI 2D Lifestyle Handbook (Table 1). Other information provided describes proper foot care and hypoglycemia management. Insulin and other medication adjustments, as well as prevention of injuries, are particularly stressed. Specific challenges to implementing exercise in BARI 2D—and in patients with type 2 diabetes and vascular disease—include the presence of peripheral neuropathy, diabetic retinopathy, peripheral vascular disease, and autonomic neuropathy. These conditions are managed according to the ADA guidelines9 and are addressed individually with each patient. In BARI 2D, pedometers and instructions for pedometer use are made available to the clinical sites from the coordinating center. Pedometer use will be encouraged for all patients in the study as a biofeedback tool to increase physical activity, and it can be initiated at any time during the study. Patients are encouraged to record their exercise routine, including the daily number of steps recorded by the pedometer.

Monitoring levels and policies for nonpharmacologic interventions

To ensure compliance with the nonpharmacologic protocol and to oversee the attainment of trial goals, a lifestyle intervention management center (LIMC) was established in June 2004. The LIMC monitors the actual implementation of the protocol by reviewing data on smoking, weight gain, and physical activity by means of data provided by the coordinating center every 3 months with regard to individual sites in relation to the overall study mean. The LIMC will intervene by keeping in contact with those sites that are outliers (>1 standard deviation above the study mean) every 6 months.

Appendix

The BARI 2D Investigators: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA (Coordinating Center): (Principal Investigator) Katherine M. Detre, MD, DrPH,† (Co-Principal Investigator) Maria Mori Brooks, PhD, (Co-Investigators) David Kelley, MD, Sheryl F. Kelsey, PhD, Trevor J. Orchard, MBBCh, MMedSci, Stephen B. Thomas, PhD, Kim Sutton Tyrrell, RN, DrPH, Joseph Zmuda, PhD, Richard Holubkov, PhD, (Coordinator) Sharon Weber Crow, BS, (Administrative Coordinators) Michele Carion, Sharon Happe, Joy Herrington, MEd, Joan M. MacGregor, MS, Scott M. O’Neal, MA, Veronica Sansing, BA, Mary Tranchine, BS, (Statisticians) Regina Hardison, MS, Kevin Kip, PhD, Jiang Lu, MS, Manuel Lombardero, MS, (Data Managers) Sue Janiszewski, MSIS, Heather Luiso, BS, Sarah Reiser, BS, David Salopek, BS, (System Programmers) Stephen Barton, ASB, Yulia Kushner, BS, BA, Owen Michael, ASB, Juinn-Woei Pan, MSIS, Nicole Bartolowits, BS, (System Support) Jeffrey P. Martin, MBA, Christopher Kania, BS, Michael Kania, BS, Jeffrey O’Donnell, BS, (Consultant) Rae Ann Maxwell, RPh, PhD. Mayo Clinic Foundation, Rochester, MN: (Study Chair) Robert L. Frye, MD. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD (Program Office): (Project Officer) Suzanne Goldberg, RN, MSN, (Deputy Project Officer) Tracey Hoke, MD, ScM, (NHLBI Officers) Patrice Desvigne-Nickens, MD, Abby Ershow, ScD, David Gordon, MD, PhD, Dina Paltoo, PhD, MPH. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH, Bethesda, MD (Co-Funding): (Program Director for Diabetes Complications) Teresa L. Z. Jones, MD, Judith Fradkin, MD. University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL (Clinical Center, Vanguard Site): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: William Rogers, MD; Diabetology: Fernando Ovalle, MD, David Bell, MBBCh, (Coordinators) Melanie Smith, RN, BSN, Ashley Vaughan, RN, BSN, Beth Barret, RN, Susan Rolli, RN. Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Scott Monrad, MD, Vankeepuram Srinivas, MD; Diabetology: Jill Crandall, MD, Joel Zonszein, MD, (Coordinators) Helena Duffy, ANP, CDE, Eugen Vartolomei, MD. Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Neal Kleiman, MD; Diabetology: Alan Garber, MD, (Coordinators) Maribel Henry, RN, BSN, Lynn Sue Felker, RN, Bella Belleza-Bascon, RN. Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Alice Jacobs, MD; Diabetology: Elliott Sternthal, MD, Susana Ebner, MD, (Coordinators) Monica Voudris, BS, Deborah Gannon, MS, Jamie Hutchinson, BS. University of British Columbia/Vancouver Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Christopher Buller, MD; Diabetology: Tom Elliott, MBBS, (Coordinators) Rebecca Fox, PA, MSc, Rossali Pilapillee, MD. Brown University/Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: David Williams, MD; Diabetology: Robert Smith, MD, Marc Laufgraben, MD, (Coordinators) Mary Grogan, RN, Janice Muratori, RNP. University of Chicago Medical Center, Chicago, IL (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: David Faxon, MD; Diabetology: Andrew Davis, MD, Sirimon Reutrakul, MD, (Coordinators) Peggy Bennett, RN, BSN, Melissa Hill, MS. University Hospitals of Cleveland/Case School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH (Clinical Center, Vanguard Site): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Dale Adler, MD; Diabetology: Faramarz Ismail-Beigi, MD, PhD, Suvinay Paranjape, MD, (Coordinators) Stacey Mazzurco, RN, Michael Borsich, RN, Karen Ridley, RN, BSN. Duke University, Durham, NC (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Christopher Granger, MD; Diabetology: Mark Feinglos, MD, Jennifer Green, MD, (Coordinators) Ronna Bakst, MS, RD, LDN, CDE, Dani Underwood, MSN, ANP. Emory University, Atlanta, GA (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: John Douglas, Jr., MD, Ziyad Ghazzal, MD, Tarek Helmy, MD, Laurence Sperling, MD; Diabetology: Suzanne Gebhart, MD, (Coordinators) Pamela Hyde, RN, Margaret Jenkins, RN, Barbara Grant. Fletcher Allen Health Care, Colchester, VT (Clinical Center, Vanguard Site): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: David Schneider, MD; Diabetology: Richard Pratley, MD, William Cefalu, MD, (Coordinators) Michaelanne Rowen, RN, CCRC, Linda Tilton, MS, RD, DE. University of Florida, Gainesville, FL (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Carl Pepine, MD, Karen Smith, MD; Diabetology: Laurence Kennedy, MD, (Coordinators) Karen Brezner, CCRC, Tempa Curry, RN, Carol Heissenberg, RN, Natalie Leddy. Fuqua Heart Center/Piedmont Hospital, Atlanta, GA (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Carl Jacobs, MD, Spencer King III, MD; Diabetology: David Robertson, MD, (Coordinators) Marty Porter, PhD, Renita Sharma, RN, BSN. The Greater Fort Lauderdale Heart Group Research, Fort Lauderdale, FL (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Alan Niederman, MD; Diabetology: Cristina Mata, MD, (Coordinator) Terri Kellerman, RN. Henry Ford Heart & Vascular Institute, Detroit, MI (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Adam Greenbaum, MD; Diabetology: Fred Whitehouse, MD, (Coordinators) Raquel Pangilinan, RN, Karen Piotrowski, RN. Houston VA Medical Center, Houston, TX (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Gabriel Habib, MD, MS, Issam Mikati, MD; Diabetology: Marco Marcelli, MD, (Coordinators) Emilia Cordero, MS, RN, NP-C, Ruben Valdez, MD. Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, MD (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Sheldon H. Gottlieb, MD; Diabetology: Annabelle Rodriguez, MD, (Coordinator) Melanie Herr, RN. Kaiser-Permanente Medical Center, San Jose, CA (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Ashok Krishnaswami, MD; Diabetology: Lynn Dowdell, MD, (Coordinator) Sarah Berkheimer, RN. Lahey Clinic Medical Center, Burlington, MA (Clinical Center, Vanguard Site): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Nicholas Tsapatsaris, MD, Bartholomew Woods, MD; Diabetology: Gary Cushing, MD, (Coordinators) Gail DesRochers, RN, Gail Wood-head, RN, Deborah Gannon, MS, Nancy Campbell, RN MS. University of Maryland Hospital, Baltimore, MD (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: J. Lawrence Stafford, MD; Diabetology: Thomas Donner, MD, (Coordinators) Michele Cines, RN, BSN, Kathryn Jeffries, BS, BSN, Margaret Testa, RN, MS, Dana Beach, RN, Cathy Krichten, NP, MS. Mayo Clinic–Rochester, Rochester, MN (Clinical Center, Vanguard Site): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Gregory W. Barsness, MD, Kirk Garratt, MD, David Holmes, MD, Charanjit Rihal, MD, Charles Mullaney, MD; Diabetology: Frank Kennedy, MD, Robert Rizza, MD, (Coordinators) Pam Helgemoe, RN, Deborah Rolbiecki, LPN. Mayo Clinic–Scottsdale, Scottsdale, AZ (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Richard Lee, MD; Diabetology: Pasquale Palumbo, MD, (Coordinators) Susan Roston, RN, Lori Wood, RN, Alycia Metcalf, RN. Memphis VA Medical Center/University of Tennessee, Memphis, TN (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Kodangudi Ramanathan, MD, Darryl Weinman, MD; Diabetology: Solomon Solomon, MD; Nephrology: Barry Wall, MD, (Coordinators) Lillie Johnson, RN, Tammy Touchstone, RN, BSN. Mexican Institute of the Social Security, Mexico City, Mexico (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cariology: Luis Lepe-Montoya, MD; Diabetology: Jorge Escobedo, MD, (Coordinators) Luisa Virginia Buitrón, MD, Beatriz Rico-Verdin, MD, PhD. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Eric Bates, MD, Claire Duvernoy, MD; Diabetology: William Herman, MD, MPH, Rodica Pop-Busui, MD, Martin Stevens, MBBCh, (Coordinators) Ann Luciano, RN, Cheryl Majors, BSN, Patricia Ross, RN, MSN. Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, MO (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Steven Marso, MD, James O’Keefe, MD; Diabetology: Alan Forker, MD, William L. Isley, MD, (Coordinators) Paul Kennedy, RN, Margaret Rosson, LPN, CCRC. University of Minnesota/Minnesota Veterans Research Institute, Minneapolis, MN (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Carl White, MD; Diabetology: John Bantle, MD, (Coordinators) Deb Johnson, RN, Aimee Muehlen, Christine Kwong, RD, CDE, Julie Dicken, RN, Kristell Reck, RD. Montreal Heart Institute/Hôtel-Dieu-CHUM (Vanguard Site), Montreal, Quebec, Canada (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Martial Bourassa, MD, Jean-Claude Tardif, MD; Diabetology: Jean-Louis Chiasson, MD, (Coordinators) Hélène Langelier, BSc, Johanne Trudel, RN, BSC, Suzy Foucher, RN, BA. Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Michael Farkouh, MD, MSc, Michael Kim, MD; Diabetology: Donald A. Smith, MD, MPH, (Coordinators) Bradley Brown, MS, Dipti Sahoo, MPH, Arlene Travis, RN. Na Homolce Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Lenka Pavlickova, MD, Petr Neuz il, MD, PhD, Jaroslav Benedik, MD; Diabetology: Šte pánka Stehlíková, MD, (Coordinators) Liz Coling, Stepan Kralovec. New York Hospital Queens, Queens, NY (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: David Schechter, MD; Diabetology: Daniel Lorber, MD; Nephrology: Phyllis August, MD, (Coordinators) Maisie Brown, RN, MSN, Patricia Depree, PhD, ANP, CDE. New York Medical College/Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Melvin Weiss, MD; Diabetology: Irene Weiss, MD, (Coordinators) Maysa Burles, MD, Joanne C. Kurylas, RN, CDE, Jean Baruth, RN, BSN. Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago, IL (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Charles Davidson, MD; Diabetology: Mark Molitch, MD, (Coordinators) Lynn Goodreau, RN, Elaine Massaro, MS, RN, CDE, Fabiola Arroyo, CCT. NYU School of Medicine, New York, NY (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Michael Attubato, MD, Frederick Feit, MD, Ivan Pena-Singh, MD; Diabetology: Stephen Richardson, MD, (Coordinator) Angela Amendola, PA, Bernardo Vargas, BS, Dallas Regan, MSN, NP, Susan Cotton Gray, NP. Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus, OH (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Raymond Magorien, MD; Diabetology: Kwame Osei, MD, (Coordinators) Cecilia Casey Boyer, RN, Kelly Neidert, RN. University of Ottawa Heart Institute/Ottawa Hospital-Civic Campus, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Richard Davies, MD, Christopher Glover, MD, Michel LeMay, MD, Thierry Mesana, MD; Diabetology: Teik Ooi, MD, Mark Silverman, MD, Alexander Sorisky, MD, (Coordinators) Colette Favreau, RN, Susan McClinton, BSN, Susan Hagar, RN, Melody Dallaire, RN. University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA (Clinical Center, Vanguard Site): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Oscar Marroquin, MD, Howard Cohen, MD; Diabetology: Mary Korytkowski, MD, (Coordinators) Glory Koerbel, MSN, CDE, Deborah Rosenfelder, BS, Carole Farrell, BSN, CCRC, Theresa Toczek, BS. Quebec Heart Institute/Laval Hospital, Sainte-Foy, Quebec, Canada (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Gilles Dagenais, MD; Diabetology: Claude Garceau, MD, (Coordinators) Dominique Auger, RN, Lyne Kelly, RN, Genviève Landry, RN, BSc. University of Sao Paulo Heart Institute, Sao Paulo, Brazil (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Whady Hueb, MD, José Ramires, MD; Diabetology: Bernardo Wajchenberg, MD, (Coordinators) Roberto Betti, MD, Neuza Lopes, MD. St. Joseph Mercy Hospital/Michigan Heart and Vascular Institute and Ann Arbor Endocrinology and Diabetes, PC, Ann Arbor, MI (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Ben McCallister, Jr., MD; Diabetology: Kelly Mandagere, MD, Robert Urbanic, MD, (Coordinators) Carol Carulli, RN, Ruth Churley-Strom, MSN, Penny Wilms, RN, BSN. St. Louis University, St. Louis, MO (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Frank Bleyer, MD; Diabetology: Arshag Mooradian, MD, (Coordinator) Sharon Plummer, NP. St. Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital Center, New York, NY (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: James Wilentz, MD, Judith Hochman, MD, James Slater, MD; Diabetology: Jeanine Albu, MD, (Coordinators) Sylvaine Frances, PA, Deborah Tormey, RN. Texas Health Science at San Antonio/South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Robert O’Rourke, MD, Edward Sako, MD, PhD; Diabetology: Janet Blodgett, MD, (Coordinators) Judith Nicastro, RN, Robin Prescott, FNP. University of Texas at Houston, Houston, TX (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Francisco Fuentes, MD, Roberto Robles, MD; Diabetology: Victor Lavis, MD, (Coordinators) Maria Selin Fulton, RN, CDE, Carol Underwood, RN, BSN, Glenna Scott, RN, Jennifer Garza, MA. Toronto General Hospital/University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Leonard Schwartz, MD; Diabetology: George Steiner, MD, (Coordinators) Kristeen Chamberlain, RN, BScN, Lisa Mighton, RN, Lilianna Stefanczyk-Sapieha, RN, Linda Wright, RN. University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Ian Sarembock, MD, Eric Powers, MD; Diabetology: Eugene Barrett, MD, (Coordinators) Linda Jahn, RN, MEd, Karen Murie, RN. Washington Hospital Center/George-town University Medical Center, Washington, DC (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Kenneth Kent, MD, William Suddath, MD; Diabetology: Michelle F. Magee, MD, (Coordinator) Becky Cockerill, MSN, Vida Reed, RN, CDE. Washington University/Barnes Jewish Hospital, St. Louis, MO (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Richard Bach, MD, Ronald Krone, MD, Majesh Makan, MD; Diabetology: Janet McGill, MD, (Coordinators) Carol Recklein, RN, MHS, CDE, Laurie Chappell, RN, Mary Jane Clifton. Wilhelminen Hospital, Vienna, Austria (Clinical Center): (Principal Investigators) Cardiology: Kurt Huber, MD; Diabetology: Ursula Hanusch-Enserer, MD, (Coordinators) Nelly Jordanova, MD, Martina Penka, MD. Angiographic Core Laboratory, Stanford University, Stanford, CA: (Principal Investigator) Edwin Alderman, MD, (Staff) Anne Schwarzkopf. Biochemistry Core Laboratory, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: (Principal Investigator) Michael Steffes, MD, PhD, (Staff) Jean Bucksa, CSL, Maren Nowicki, MT. ECG Core Laboratory, St. Louis University, St. Louis, MO: (Principal Investigator) Bernard Chaitman, MD, (Staff) Terri Belgeri, RN, Jane Eckstein, RN. Economics Core Laboratory, Stanford University, Stanford, CA: (Principal Investigator) Mark A. Hlatky, MD, (Staff) Kathryn A. Melsop, MS. Fibrinolysis Core Laboratory, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT: (Principal Investigator) Burton E. Sobel, MD, (Staff) Michaelanne Rowen, RN, CCRC. Nuclear Cardiology Core Laboratory, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL: (Principal Investigator) Ami E. Iskandrian, MD, (Staff) Mary Beth Hall, RN, BSN. Diabetes Management Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH: (Director) Saul Genuth, MD, (Staff) Theresa Bongarno, BS. Hypertension Management Center, Lahey Clinic Medical Center, Burlington, MA: (Co-Director) Richard W. Nesto, MD. Hypertension Management Center, New York Hospital Queens, Queens, NY: (Co-Director) Phyllis August, MD, (Staff) Karen Hultberg, MS. Lifestyle Intervention Management Center, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, MD: (Co-Director) Sheldon H. Gottlieb, MD. Lifestyle Intervention Management Center, St. Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital Center, New York, NY: (Co-Director) Jeanine Albu, MD, (Staff) Helene Rosenhouse-Romeo, MS, RD. Lipid Management Center, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: (Director) Trevor J. Orchard, MBBCh, MMedSci, (Staff) Georgia Pambianco, MPH. North Canton, Ohio: (Safety Officer) Michael Mock, MD. Operations Committee: (Chair) Robert L. Frye, MD, (Members) Maria Mori Brooks, PhD, Sharon Weber Crow, BS, Patrice Desvigne-Nickens, MD, Katherine M. Detre, MD, DrPH,† Abby Ershow, ScD, Saul Genuth, MD, Suzanne Goldberg, RN, MSN, David Gordon, MD, PhD, Regina Hardison, MS, Tracey Hoke, MD, ScM, Teresa L. Z. Jones, MD, David Kelley, MD, Sheryl Kelsey, PhD, Richard W. Nesto, MD, Trevor J. Orchard, MBBCh, MMedSci, Dina Paltoo, PhD, MPH. Morbidity and Mortality Classification Committee: (Chair) Thomas Ryan, MD, (Co-Chair) Harold Lebovitz, MD, (Members) Robert Brown, MD, Gottlieb Friesinger, MD, Edward Horton, MD, Jay Mason, MD, Jack Titus, MD, PhD, Lawrence Wechsler, MD. Data and Safety Monitoring Board: (Chair) C. Noel Bairey-Merz, MD, (former Chair) J. Ward Kennedy, MD, (Executive Officer) David Gordon, MD, PhD, (Members) Elliott Antman, MD, John Colwell, MD, PhD, Sarah Fowler, PhD, Curt Furberg, MD, Lee Goldman, MD, Bruce Jennings, MA, Scott Rankin, MD.

Footnotes

Deceased.

The core laboratories for electrocardiography (Dr. Bernard Chaitman, St. Louis University), economics (Dr. Mark A. Hlatky, Stanford University), and fibrinolysis (Dr. Burton E. Sobel, University of Vermont) were funded, respectively, by Grant Nos. U01 HL061746, U01 HL061748, and U01 HL063804 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The Nuclear Cardiology Core Laboratory (Dr. Ami E. Iskandrian, University of Alabama at Birmingham) received funding from Astellas Pharma US, Inc.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. American Diabetes Association Consensus Statement: Role of cardiovascular risk factors in prevention and treatment of macrovascular disease in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1989;12:573–579. doi: 10.2337/diacare.12.8.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner RC, Millns H, Neil HAW, Stratton IM, Manley SE, Matthews DR, Holman RR for the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Risk factors for coronary artery disease in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS: 23) BMJ. 1998;316:823–828. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7134.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suarez L, Barrett-Connor E. Interaction between cigarette smoking and diabetes mellitus in the prediction of death attributed to cardiovascular disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;120:670–675. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haire-Joshu D, Glasgow RE, Tibbs TL. Smoking and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1887–1898. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.11.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eliasson B. Cigarette smoking and diabetes. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;45:405–413. doi: 10.1053/pcad.2003.00103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider SH, Ruderman NB. Exercise and NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:785–789. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.7.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregg EW, Gerzoff RB, Caspersen CJ, Williamson DF, Narayan KMV. Relationship of walking to mortality among US adults with diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1440–1447. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.12.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albu J, Pi-Sunyer FX. Obesity and diabetes. In: Bray G, Bouchard C, editors. Handbook of Obesity. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc; 2004. pp. 899–918. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes 2005. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(suppl 1):S4–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2005;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith SC, Blair SN, Bonow RO, Brass LM, Cerqueira MD, Dracup K, Fuster V, Gotto A, Grundy SM, Miller NH, et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for preventing heart attack and death in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: 2001 Update. A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1581–1583. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01682-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G for the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Effects of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients [published corrections appear in N Engl J Med 2000;342:748 and 2000;342:1376] N Engl J Med. 2000;342:145–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2005–2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orchard TJ. Dyslipoproteinemia and diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1990;19:361–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton J, Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12 year cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:434–444. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manson JE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Królewski AS, Rosner B, Arky RA, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of maturity-onset diabetes mellitus and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1141–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.West Scotland Coronary Prevention Group. Influence of pravastatin and plasma lipids on clinical events in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS) Circulation. 1998;97:1440–1445. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.15.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, Whitney E, Shapiro DR, Beere PA, Langendorfer A, Stein EA, Kruyer W, Gotto AM., Jr Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. JAMA. 1998;279:1615–1622. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pyörälä K, Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J, Faergeman O, Olsson AG, Thorgeirsson G. Cholesterol lowering with simvastatin improves prognosis of diabetic patients with coronary heart disease. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:614–620. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg RB, Mellies MJ, Sacks FM, Moyé LA, Howard BV, Howard WJ, Davis BR, Cole TG, Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E for the CARE Investigators. Cardiovascular events and their reduction with pravastatin in diabetic and glucose-intolerant myocardial infarction survivors with average cholesterol levels: subgroup analyses in the Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) Trial. Circulation. 1998;98:2513–2519. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.23.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811053391902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, Hitman GA, Neil HA, Livingstone SJ, Thomason MJ, Mavkness MI, Charlton-Menys V, Fuller JH for the CARDS investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multi-center randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;364:685–696. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kannel WB. Lipids, diabetes, and coronary heart disease: insights from the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1985;110:1100–1106. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, Nelson DB, Elam MB, Schaefer EJ. Diabetes, plasma insulin and cardiovascular disease: subgroup analysis from the Department of Veterans Affairs high-density lipoprotein intervention trial (VA-HIT) Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2597–2604. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.22.2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koskinen P, Manttari M, Manninen V, Huttunen JK, Heinonen OP, Frick MH. Coronary heart disease in NIDDM patients in the Helsinki Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:820–825. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.7.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Effect of fenofibrate on progression of coronary artery disease in type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study, a randomised study [published correction appears in Lancet 2001;357:1890] Lancet. 2001;357:905–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, Pasternak RC, Smith SC, Jr, Stone NJ for the Coordinating Committee of the National Cholesterol Education Program. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown WV. Niacin for lipid disorders: indications, effectiveness, and safety. Postgrad Med. 1995;98:185–189. 192–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arauz-Pacheco C, Parrott MA, Raskin P. The treatment of hypertension in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:134–147. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Diabetes Association. Hypertension management in adults with diabetes [position statement] Diabetes Care. 2004;27(suppl 1):S65–S67. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report [published correction appears in JAMA 2003; 290:197] JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Efficacy of atenolol and captopril in reducing risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 39. BMJ. 1998;317:713–720. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curb JD, Pressel SL, Cutler JA, Savage PJ, Applegate WB, Black H, Camel G, Davis BR, Frost PH, Gonzalez N, et al. for the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program Cooperative Research Group. Effect of diuretic-based antihypertensive treatment on cardiovascular disease risk in older diabetic patients with isolated systolic hypertension. JAMA. 1996;276:1886–1892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S for the RENAAL Study Investigators. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zanella MT, Ribeiro AB. The role of angiotensin II antagonism in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review of renoprotection studies. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1019–1034. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moser M. Current recommendations for the treatment of hypertension: are they still valid? J Hypertens. 2002;20(suppl 1):S3–S10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlof B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, Menard J, Rahn KH, Wedel H, Westerling S for the HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–1762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tuomilehto J, Rastenyte D, Birkenhager WH, Thijs L, Antikainen R, Bulpitt CJ, Fletcher AE, Forette F, Goldhaber A, Palatini P, et al. for the Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Investigators. Effects of calcium-channel blockade in older patients with diabetes and systolic hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:677–684. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) [published corrections appear in JAMA 2003;289:178 and 2004;291:2196] JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Packer M, O’Connor CM, Ghali JK, Pressler NL, Carson PE, Belkin RN, Miller AB, Neuberg GW, Frid D, Wertheimer JH, et al. for the Prospective Randomized Amlodipine Survival Evaluation Study Group. Effect of amlodipine on morbidity and mortality in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1107–1114. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bakris GL, Gaxida E, Messerli FH, Mancia G, Erdine S, Cooper-DeHoff R, Pepino CH for the INVEST Investigators. Clinical outcomes in the diabetes cohort of the International Verapamil SR-Trandolapril Study (INVEST) Hypertension. 2004;44:637–642. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000143851.23721.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kothari V, Stevens RJ, Adler AI, Stratton IM, Manley SE, Neil HA, Holman RR for the UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. UKPDS 60: risk of stroke in type 2 diabetes estimated by the UK Prospective Diabetes Study risk engine. Stroke. 2002;33:1776–1781. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020091.07144.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adler AI, Stevens RJ, Neil A, Stratton IM, Boulton AJM, Holman RR for the UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. UKPDS 59: hyperglycemia and other potentially modifiable risk factors for peripheral vascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:894–899. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan J, Rimm E, Colditz G, Stampfer M, Willett W. Obesity, fat distribution and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1–10. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sargeant LA, Khaw KT, Bingham S, Day NE, Luben RN, Oakes S, Welch A, Wareham NJ. Cigarette smoking and glycaemia: the EPIC-Norfolk study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:547–554. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chuahirun T, Wesson DE. Cigarette smoking predicts faster progression of type 2 established diabetic nephropathy despite ACE inhibition. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:376–382. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.30559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris MI. Health care and health status and outcomes for patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:754–758. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glasgow RE. Giving smoking cessation the attention that it deserves. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1453–1454. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.10.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Canga N, De Irala J, Vara E, Duaso MJ, Ferrer A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Intervention study for smoking cessation in diabetic patients: a randomized controlled trial in both clinical and primary care settings. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1455–1460. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.10.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.The Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline Panel, Staff and Consortium Representatives. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: a US Public Health Service report. JAMA. 2000;283:3244–3254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fiore M, Bailey W, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Reference Guide for Clinicians. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; Oct, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Activity and Good Nutrition: Essential Elements to Prevent Chronic Diseases and Obesity. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maggio CA, Pi-Sunyer FX. The prevention and treatment of obesity: application to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1744–1766. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.11.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Franz MJ, Bantle JP, Beebe CA, Brunzell JD, Chaisson JL, Garg A, Holzmeister LA, Hoogwerf B, Mayer-Davis E, Mooradian AD, et al. Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:148–198. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Albu J, Raja-Khan N. The management of the obese diabetic patient. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2003;30:465–491. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(03)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garg A. High mono-saturated fat diets for patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1994;271:1421–1428. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu-Poh S, Zhao G, Etherton T, Naglak M, Jonnalagadda S, Kris-Etherton PM. Effects of the National Cholesterol Education Program’s step I and step II dietary intervention programs of cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:632–646. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, Obarzanek E, Conlin PR, Miller ER, III, Simons-Morton DG, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:3–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.The Diabetes Prevention Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Simkin-Silverman L, Wing RR. Management of obesity in primary care. Obes Res. 1997;5:603–612. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gibbons RJ, Chatterjee K, Daley J, Douglas JS, Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Grunwald MA, Levy D, Lytle BW, O’Rourke RA, et al. ACC/AHA/ACP-ASIM guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients with Chronic Stable Angina) [published corrections appear in J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:314 and 2001;38:296] J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:2092–2197. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]