Abstract

Objective

We performed a longitudinal study of Holocaust survivors with and without PTSD by assessing symptoms and other measures at two intervals, approximately 10 years apart.

Method

The original cohort consisted of 63 community-dwelling subjects, of whom 40 were available for follow-up.

Results

There was a general diminution in PTSD symptom severity over time. However, in 10% of the subjects (n=4), new instances of Delayed Onset PTSD developed between the Time 1 and Time 2. Self-report ratings at both assessments revealed a worsening of trauma related symptoms over time in persons without PTSD at Time 1, but an improvement in those with PTSD at Time 1.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that a nuanced characterization of PTSD trajectory over time is more reflective of PTSD symptomatology than simple diagnostic status at one time. The possibility of Delayed Onset trajectory complicates any simplistic overall trajectory summarizing the longitudinal course of PTSD.

Keywords: Holocaust servivors, longitudinal course, PTSD, morale, traumatic loss

Significant Outcomes

PTSD symptom severity generally diminishes over time, however in a small subsample, there is a delayed onset on new PTSD developed between Time 1 and Time 2, even in an elderly cohort exposed decades earlier. Thus, although there is a general diminution of symptoms in those with PTSD at Time 1, those without PTSD at Time 1 tended to show a worsening in PTSD and general symptomatology.

All survivors showed a decline in moral and physical health over time.

The findings suggest that longitudinal information over time provides a more powerful indicator of symptom severity than cross sectional diagnostic evaluations.

Limitations

The small sample size, particularly in some of the subgroups is a limitation of the study.

The attrition of subjects from Time 1 to Time 2 owing to death, illness or disability is a limitation.

Information about PTSD prior to the Time 1 assessment was obtained retrospectively at Time 1.

Introduction

The psychiatric literature continues to present divergent views on the longitudinal course of PTSD symptoms over decades and in relation to aging, making it difficult to predict rates of persistence or remission of PTSD with the passage of time or to identify individual differences that affect this trajectory. On one hand, some studies emphasize that PTSD symptoms often diminish over time in aging persons (1,2). Particularly noteworthy are prospective longitudinal data demonstrating a reduction in the percentage of subjects meeting criteria for PTSD 40 and 50 years following exposure compared to earlier time points (3,4). Older persons with PTSD tend to endorse mild to moderate symptom severity on diagnostic assessments rather than symptom severity in the extreme range (5). Contrasting this view are other longitudinal studies highlighting the persistence or exacerbation of PTSD symptoms in older subjects (6,7,8), particularly in Holocaust survivors (9,10,11). While recognizing the remarkable adaptive capacities of such persons, these studies underscore the continued psychiatric and medical morbidity associated with extreme traumatization.

The interpretation of equivocal data is fueled by the societal ramifications of defining either recovery or persistence as the norm. Thus, it has been suggested that a failure to expect resilience and adaptive capacities stigmatizes survivors by labeling them as irretrievably damaged (12). Conversely, denying the long-term consequences of trauma exposure may result in a reduced standard of care for many elderly trauma survivors, and may jeopardize compensation related disability. Indeed, chronic PTSD is a condition currently recognized by the Veterans Administration as permanently disabling.

A more nuanced approach to the dichotomy implied by the above review is to posit different trajectories of PTSD symptomatology over time, and identify individual differences that might be associated with them. When such an approach was applied to the study of Israeli war veterans, it revealed different recovery rates of PTSD in association with trauma duration (13). However, PTSD and other mental health problems in the elderly are not fully predicted by the severity of exposures that initiated PTSD decades earlier (14,15,16). In the current study, we present data from a ten-year follow-up assessment of PTSD symptoms in a small, but representative, group of Holocaust survivors described previously (17,18). At both times, we assessed severity of symptoms of PTSD and other psychiatric disorders, psychosocial indices of well-being such as morale and physical health, and exposure to trauma and stressful life events.

Aims of the study

We hypothesized based on the literature that there would be a general diminution in PTSD symptom severity over time, but that differences in the pattern of change would be associated with intervening life events that could account for persistence or exacerbation of PTSD symptoms in some subjects. It was also of interest to explore the potential relationships of other psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial characteristics with individual differences in the trajectory of PTSD.

Material and methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 40 Holocaust survivors (13 men, 27 women), representing a subgroup of 63 participants who had been evaluated approximately ten years earlier (17, 18). As previously described, participants were chosen randomly from public lists of Holocaust survivors available at the local historical society and were asked to participate in a study examining the impact of the Holocaust. Procedures for the follow-up study were approved separately by the Institutional Review Board at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Twenty-three subjects who had previously participated were not enrolled in the follow-up (10 were deceased, 8 relocated, 2 in nursing homes and 3 refused for scheduling reasons). There was no systematic difference in diagnostic status among those who were and were not available for the follow-up evaluation. Those subjects who agreed to participate at follow-up were screened first using the Mini-Mental Status Examination (19), a brief mental status evaluation, to identify cognitive impairment that could have interfered with the ability of the subject to provide informed consent or accurately report symptomatology, but no subject obtained a score under 21/30.

Clinical Evaluation

Axis I psychiatric diagnoses, including PTSD, were determined by trained and credentialed clinical psychologists or psychiatrists with established inter-rater reliability according to DSM-IV criteria using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (20) and the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (21), respectively. The CAPS symptom subscales were used as continuous measures of symptom severity. To enhance fidelity of the evaluations, all interviews were taped, and reviewed by independent psychologists. Any discrepancy noted between the evaluator and the independent quality control rating was discussed at a consensus conference. Initial CAPS evaluation at Time 1 included assessments of both current and lifetime (previous worst episode, based on retrospective recall) symptomatology. The original scoring by the DSM-III-R criteria was converted to DSM-IV criteria by including physiological reactivity (previously a hyperarousal symptom) in the intrusive symptom cluster. Subjects also completed the Civilian Mississippi PTSD scale, a self-report measure that assesses the global effect of stressful life events (22); the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90), a self-report measure that evaluates a variety of psychiatric symptoms (23); the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale (Morale) (24), a 22 number scale that measures factors associated with agitation, attitude towards own aging, and lonely dissatisfaction; and a Likert rating of subjective physical health status obtained from the OARS Medical Checklist (25).

Statistical Methods

At Time 1, subjects were classified according to whether or not they met the diagnostic criteria for current PTSD, which invariably reflected a continuation of chronic symptoms beginning decades earlier in response to trauma exposure during World War II. The group not meeting criteria for current PTSD was comprised of both those who had never met criteria for PTSD and those who had met criteria for past PTSD but no longer met criteria at Time 1. At Time 2, in 25% of the cases, diagnostic status changed from Time 1. Thus, five groups were studied reflecting different PTSD trajectories: The PTSD-/PTSD-/PTSD- group (Resistant) did not meet criteria for current or past PTSD at any assessment (n=11). The PTSD+/PTSD-/PTSD- (Earlier Resilience) had demonstrated recovery at Time 1 and maintained it at the Time 2 assessment (n=5). The PTSD+/PTSD+/PTSD- group (Later Resilience) had been diagnosed with past and current PTSD, but demonstrated recovery at the Time 2 assessment (n=6). The PTSD-/PTSD-/PTSD+ group had not been diagnosed with past or current PTSD at Time 1, but developed PTSD by the Time 2 assessment (Delayed Onset; n=4). Finally, the PTSD+/PTSD+/PTSD+ (Chronic PTSD) group demonstrated a chronic course of PTSD that was maintained at both assessments (n=14).

Demographic and trauma exposure variables of the trajectory groups were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous measures and Pearson's chi square for categorical measures at each time point separately. The association between Time 1 and Time 2 on the CAPS and subject-rated measures was assessed by partial correlation controlling for the five groups (i.e., the pooled within-group correlations) and this was also used for correlations between changes on different measures.

For the CAPS data, a repeated measures ANOVA compared the trajectory groups on the three subscales at each of three times (worst lifetime and current PTSD at Time 1 and Time 2). The Huynh-Feldt adjustment to degrees of freedom was used to correct for violations of sphericity assumptions. For the four subject-rated measures, repeated measures ANOVA compared the groups at Time 1 and Time 2.

To compare trajectories among the five groups defined by PTSD at different times we performed t-tests for five comparisons among pairs of groups for which specific predictions were made. The Resistant and Earlier Resilience groups were expected to be indistinguishable at both Time 1 and Time 2 since both did not meet criteria for current PTSD at either of these assessments. Conversely, the Earlier and Later Resilience groups were expected to be significantly different at the Time 1 assessment, since they differed in diagnostic status, but not at Time 2, when their diagnostic status was the same. The Later Resilience and Chronic PTSD groups were expected to differ at Time 2, but not at Time 1, since the Later Resilience no longer met criteria for PTSD at Time 2. Resistant and Delayed Onset groups were not expected to differ at Time 1, as neither group had current PTSD or lifetime PTSD, but were expected to differ at Time 2. Since sample sizes were quite small, an effect size was calculated for each t-test.

Results

The age at Time 1 of those not tested at Time 2 was 70.2 (5.1) years compared to 65.8 (5.1) for those who were tested at Time 2. There was a significant difference in age among those that were tested at Time 2 and those that were not (F=10.61, df=1,62, p=0.002). Corresponding self report PTSD scores on Mississippi PTSD scale were 86.30 (18.9) and 92.05 (23), and for CAPS 73.08 (21.24) and 40.50 (25.4), for the lost to follow-up and study participants in Time 2, respectively. There was no significant difference between these two groups on these PTSD symptom measures.

Of those participants tested at both time intervals, the mean ages and SD for the samples at Time 1 and Time 2 were 65.83 (4.96) and 76.80 (5.11), respectively. The mean duration since the Holocaust was 49.45 (2.24) at Time 1 and 60.43 (2.27) at Time 2. There were no significant differences in age (F(4, 39) = .71, p = .59; F(4, 39) = 1.02, p = .41) or in mean duration since the Holocaust (F(4, 39) = .17, p = .95; F(4, 39) = .36, p = .84) at either time point according to group. The sample was 32.5% male. With respect to education, 15.0% completed grade 6 or below, 65.0% completed grade 7-12, and 20.0% completed high school or more. At Time 1, 77.5% were married; at Time 2, 62.5% were married. Mean age of exposure to the Holocaust was 16.38 (5.30). There were no differences across groups in gender (χ2(4) = 5.66, p = .23), education (χ2(16) = 17.57, p = .35), marital status at Time 1 (χ2(4) = 3.05, p = .55), marital status at Time 2 (χ2(4) = 1.86, p = .76) or age at Holocaust exposure (F(4, 35) = .64, p = .64). There were no significant differences in the percentage of the sample with a new onset of major depressive disorder between Time 1 and Time 2 (χ2(4) = 3.79, p = .44).

With respect to trauma exposure after the Holocaust and its immediate aftermath, events were classified into two broad categories, traumatic loss (of a sibling or a child, or early loss of spouse) unrelated to the Holocaust, and other events meeting the “Criterion A” definition (e.g., car accidents, assault, and war-zone exposure). At Time 2, subjects were assessed only for new incidents of trauma exposure between the two interviews. There were no group differences in either category of trauma exposure at Time 1 (χ2(4) = 7.37, p = .12, χ2(4) = 4.16, p = .39, respectively). Here 57.5% of the entire sample noted a traumatic loss by Time 1, there were fewer such losses in the Delayed Onset group (0%) compared to 60% of the Early Resilience Group, 54.5% of the Resistant group, 88.3% of the Later Resilience group, and 64.3% of the Chronic PTSD group experienced a traumatic loss at Time 1. However, at Time 2, there were significant differences in traumatic loss (χ2(4) = 13.54, p = .009), reflecting a greater percentage among those with Delayed Onset PTSD than the other groups (75.0%). 9.1% of the Resistant group, 0% of the Earlier Resilience and Later Resilience groups and 14.3% of the Chronic PTSD group experienced a traumatic loss between Times 1 and 2. There were no group differences in other traumatic exposures between Time 1 and Time 2 (χ2(4) = 3.07, p = .55).

There were significant pooled within-group associations between Time 1 and Time 2 for Intrusive (r = .53, p = .001), but not for Avoidance (r = -.13, p = .43), or Hyperarousal (r = .26, p = .13), and thus, CAPS total score (r = .22, p = .21). For the self-report measures, there were significant associations for Mississippi PTSD scores (r = 53, p = .001), SCL-90 (r = .43, p = .015), and Physical Health Status (r = .68, p < .0005), but not for Morale (r = .02, p =. 92). For all measures, the Time 1 and Time 2 means ± standard deviation (SD) by trajectory are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean symptom severity in five groups according to PTSD trajectory.

| Resistant (N=11) | Earlier Resilience (N = 5) | Later Resilience (N = 6) | Delayed Onset (N = 4) | PTSD (N=14) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||||

| Clinical Scales | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 |

| Intrusive | 4.6 (5.4) | 5.3 (5.4) | 16.0 (2.2) | 14.2 (4.6) | 13.7 (4.7) | 7.0 (7.4) | 18.0 (8.8) | 12.5 (7.9) | 20.6 (5.6) | 17.8 (6.8) |

| Avoidance | 2.1 (3.6) | 1.8 (3.5) | 12.8 (7.6) | 7.6 (6.2) | 20.3 (4.7) | 8.8 (7.00) | 7.2 (4.3) | 23.0 (7.0) | 22.6 (7.7) | 20.2 (6.6) |

| Hyperarousal | 3.7 (2.5) | 4.1 (5.6) | 9.4 (6.0) | 5.8 (4.8) | 14.3 (3.9) | 9.5 (2.7) | 10.5 (6.9) | 16.5 (6.9) | 21.6 (8.5) | 16.9 (6.6) |

| CAPS Total | 10.4 (8.9) | 11.2 (10.7) | 37.6 (10.3) | 27.6 (12.3) | 48.3 (11.2) | 25.3 (14.5) | 36.7 (14.1) | 52.0 (17.7) | 64.0 (18.4) | 54.9 (16.3) |

| Mississippi | 66.0 (9.2) | 76.4 (11.9) | 94.6 (21.2) | 91.0 (13.3) | 99.8 (9.1) | 84.5 (9.2) | 91.2 (16.9) | 99.9 (11.9) | 108.5 (19.7) | 98.4 (16.9) |

| SCL-90 | 2.3 (2.0) | 4.1 (5.3) | 6.6 (5.1) | 7.7 (5.2) | 5.8 (.96) | 5.5 (2.0) | 6.9 (4.1) | 9.7 (6.7) | 12.6 (7.0) | 11.1 (6.0) |

| Lawton Morale | 30.7 (2.0) | 26.6 (4.1) | 27.2 (1.8) | 23.8 (5.0) | 25.8 (2.9) | 23.0 (6.3) | 23.0 (4.0) | 20.6 (1.9) | 22.4 (3.2) | 21.9 (3.3) |

| Physical health | 3.4 (1.0) | 2.5 (0.5) | 3.2 (1.1) | 2.6 (0.9) | 3.0 (1.1) | 2.5 (.5) | 2.7 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.5) | 2.7 (1.1) | 1.7 (0.6) |

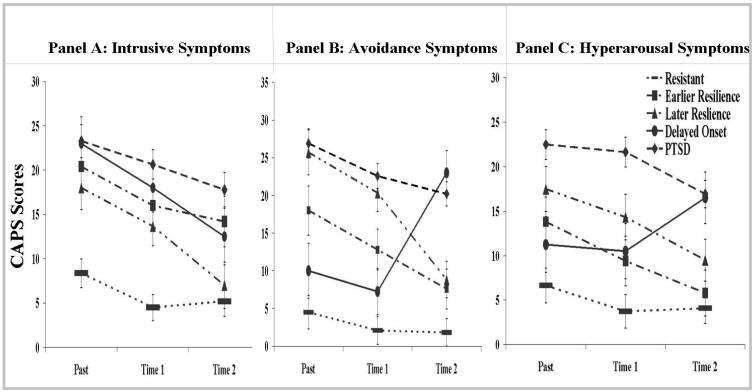

In addition to Time 1 and Time 2 CAPS measures, clinicians evaluated worst episode PTSD symptom severity based on retrospective reports at Time 1. These three time points are graphed in Figure 1 for the PTSD symptom clusters. Results of a repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated a significant main effect for Group (F(4, 35) = 31.50, p < .001), reflecting an overall tendency for the Resistant group to have lower levels of symptoms than the other four groups that had PTSD at some time. A main effect of Symptom Cluster (F(2, 70) = 4.52, p = .014) reflected that scores for Avoidance, which included a larger number of items, were higher than the other symptom clusters. A main effect of Time (F(2,70) = 14.63, p < .001) indicated an overall tendency for reduction in the extent of symptom severity. There were significant interactions for Group × Symptom (F(8, 70) = 3.51, p = .002) and Group × Time (F(8,70) = 3.08, p = .005), and trend level significance for Time × Symptom (F(3.93, 137.66) = 2.27, p = .07). Most importantly, there was a very significant 3-way interaction of Group × Time × Symptoms (F(15.73, 137.66) = 3.90, p < .001), reflecting that the Delayed Onset group was an exception to the general pattern of reduction of symptoms since their symptoms increased from Time 1 to Time 2 as they developed PTSD. Interestingly, however, this increase in symptoms was limited to Avoidance and Hyperarousal clusters, whereas Intrusive symptoms declined from Time 1 to Time 2 in a similar manner to the decline in the other groups. When we repeated the above analysis excluding the Delayed Onset group the 3-way interaction was not significant (F(12, 128) = 0.91, p = .54), confirming that the original 3-way interaction was driven by the Delayed Onset group.

Figure 1. CAPS symptom clusters of entire sample before Time 1, at Time 1 and at Time 2.

Numbers represent estimated marginal means for each subdivided symptom cluster on the CAPS before Time 1, at Time 1 and at Time 2.

A more detailed description of this interaction is obtained by considering the five specific comparisons among pairs of groups, defined by patterns of PTSD diagnosis over time (Table 2). Contrary to the hypothesis, the Earlier Resilience group was significantly more symptomatic than the Resistant group, for the CAPS total and the three symptom clusters at both times, except for Hyperarousal symptoms at Time 2. This difference may be attributed to the presence of past PTSD in the Earlier Resilience group, who were more symptomatic than those who had not developed the disorder, although not meeting diagnostic criteria for PTSD at either time. For all the significant results, the effect sizes ranged from 1.15 to 2.83, demonstrating very large differences between the groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical differences in five pairs of groups according to PTSD trajectory

| Resistant Vs. Earlier Resilience t(14), p, d (effect size) |

Earlier Resilience Vs. Later Resilience t(9), p, d (effect size) |

Later Resilience Vs. PTSD t(18), p d (effect size) |

Resistant Vs. Delayed Onset t(13), p, d (effect size) |

Resistant Vs. PTSD t(23), p, d (effect size) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Scales | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 |

| Intrusive |

-4.52,< .001 2.78 |

-3.21, .006 1.79 |

1.01, ns 0.63 |

1.88, ns 1.16 |

-2.68, .015 1.35 |

-3.16, .005 1.51 |

-3.65, .003 1.85 |

-2.04, .062 1.07 |

-7.30, < .001 2.95 |

-4.99, < .001 2.04 |

| Avoidance | -3.92, .002 1.81 |

-2.41, .030 1.15 |

-2.03, .073 1.20 |

-.31, ns 0.19 |

-0.66, ns 0.35 |

-3.48, .003 1.68 |

-2.34, .036 1.30 |

-7.97, < .001 3.83 |

-8.15, < .001 3.42 |

-8.36, < .001 3.49 |

| Hyperarousal | -2.75, .016 1.24 |

-0.59, ns 0.33 |

-1.65, ns 0.97 |

-1.62, ns 0.95 |

-2.00, .061 1.11 |

-2.63, .017 1.48 |

-2.91, .012 1.30 |

-3.57, .003 1.96 |

-6.76, < .001 2.87 |

-5.14, < .001 2.09 |

| CAPS Total | -5.42, < .001 2.83 |

-2.71, .017 1.42 |

-1.64, ns 1.00 |

0.28, ns 0.17 |

-1.92, .071 1.03 |

-3.83, .001 1.92 |

-4.38, .001 2.24 |

-5.51, < .001 2.79 |

-8.85, < .001 3.71 |

-7.67, < .001 3.19 |

| Mississippi | -3.86, .002 1.75 |

-2.20, .045 1.16 |

-0.55, ns 0.32 |

0.96, ns 0.57 |

-1.02, ns 0.56 |

-1.89, .075 1.03 |

-3.79, .002 1.86 |

-3.38, .005 1.97 |

-6.59, < .001 2.76 |

-3.68, .001 1.51 |

| SCL-90 | -2.50, .025 1.12 |

-1.27, ns 0.69 |

0.39, ns 0.22 |

0.96, ns 0.56 |

-2.33, .032 1.36 |

-2.19, .042 1.24 |

-2.95, .011 1.41 |

-1.69, ns 0.92 |

-4.71 < .001 2.00 |

-3.03, .006 1.23 |

| Lawton Morale | 3.30, .005 1.83 |

1.17, ns 0.61 |

0.91, ns 0.56 |

0.23, ns 0.14 |

2.22, .040 1.11 |

0.53, ns 0.22 |

5.01, < .001 2.42 |

2.73, .017 1.84 |

7.40, < .001 3.06 |

3.18, .004 1.26 |

| Physical health | .45, ns 0.24 |

-.16, ns 0.07 |

0.30, ns 0.18 |

0.23, ns 0.13 |

0.52, ns 0.26 |

2.71, .014 1.35 |

1.28, ns 0.87 |

2.63, .021 1.56 |

1.68, ns 0.68 |

3.59, .002 1.46 |

Again contradicting initial hypotheses, no significant differences were observed between the Earlier and Later Resilience groups on total CAPS or distinct symptom clusters at Time 1, although there was a non-significant trend for a difference in avoidance symptoms. These effect sizes ranged from 0.63 to 1.20, which are substantially smaller than those for the significant results when comparing Resistant vs. Earlier Resilient groups. As expected, there were no significant differences at Time 2, with similar effect sizes (0.17 to 1.16).

As predicted, the Later Resilience and Chronic PTSD groups differed at Time 2 (effect sizes 1.48 to 1.92). However, they also differed at Time 1 in Intrusive symptoms, and showed a trend level difference in Hyperarousal and total CAPS scores (effect sizes 1.03 to 1.35 for these tests).

The Delayed Onset group was significantly higher than the Resistant group on all three symptom clusters (and total PTSD severity) at the Time 1 assessment (effect sizes 1.30- to 2.24), though group differences were not hypothesized. At the Time 2 assessment, group differences were as hypothesized, with a non-significant trend for a difference in Intrusive symptoms (effect sizes 1.07 to 3.83).

Finally, the Resistant and Chronic PTSD groups were compared. These groups were expected to differ significantly from each other at all time points, and indeed this was the case (effect sizes 2.04 to 3.71).

When change scores were compared in the five pairs of groups (Time 2 - Time 1), there were no significant differences in the extent of change in Intrusive, Avoidance, or Hyperarousal symptoms in four of the five pairs of groups, indicating that within the period of time that elapsed between the two assessments, the extent of change was comparable regardless of diagnostic status. The exception to this was in the comparison between Resistant vs. Delayed Onset subjects. Here there were differences in Intrusive (t(13) = -2.80, p = .015), Avoidance (t(13) = 2.28, p = .040), and Hyperarousal (t(13) = -2.10, p = .056) symptoms, reflecting a greater symptom exacerbation in the Delayed Onset group.

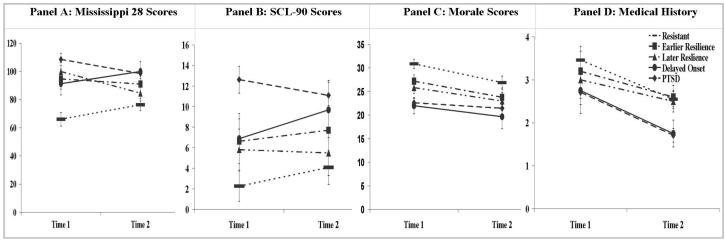

Because the above results were generated by different clinicians at different times, there may have been a lack of inter-rater reliability (which could not be assessed). Alternatively, the clinician-rated assessments may have been more objective, while the self-reports may have been more biased. To further examine these possibilities, we were interested in determining whether similar patterns of group differences would be present in self-reported measures of PTSD and other measures, obtained at both the Time 1 and Time 2 assessments. The means are presented in Table 1 and graphically portrayed in Figure 2 to demonstrate different patterns with these measures.

Figure 2. Self-report measures of symptom severity at Time 1 and Time 2.

Scores represent estimated marginal means for self-reports at Time 1 and Time 2.

On the Mississippi PTSD Scale, there was a significant effect of Group (F(4,33) = 9.22, p < .0005), but not Time (F(1,33) = .001, p = .97). There was also a significant Group × Time interaction (F(4,33) = 5.21, p = .002) reflecting increases for the Resistant and Delayed Onset groups and decreases for the other groups. This interaction was not completely driven by the increase for the Delayed Onset group since there was still a significant interaction of Group × Time (F(3, 31) = 6.07, p = .002) for the other four groups when the analysis was repeated without this group. In contrast, when those four groups were compared on the CAPS total score, for Time 1 and Time 2 the Group × Time interaction (F(3, 32) = 2.28, p = .10) was not significant. Thus, the Resistant group of Holocaust survivors who had never met criteria for PTSD rated themselves as increasing in the burden of PTSD symptoms over time, despite the fact that clinicians did not rate these symptoms as significantly increasing from Time 1 to Time 2.

For the Mississippi PTSD Scale scores, analysis of the different groups with pairwise comparisons (Table 2) reveals a similar pattern to the CAPS scores in that no group differences might have been expected at Time 1 or 2 between the Resistant and Earlier Resilient group, but differences were present at both times. Differences between Earlier and Later Resilience groups and between Later Resilience and Chronic PTSD groups might have been expected at Time 1, but were not significant. Conversely, differences between Resistant and Delayed Onset PTSD might not have been expected at Time 1, but were significant.

On the SCL-90 there was only a main effect of Group (F(4, 35) = 6.99, p < .001) but no effect of Time (F(1, 35) = .53, p = .47) or Group × Time interaction (F(4, 35) = .71, p =. 59). At both times, the groups with current PTSD had higher SCL-90 scores than the groups without PTSD. Thus, although there were differences among the groups, their overall mean did not change over time and groups did not differ in their changes over time. This differed from the PTSD symptomatology, demonstrating that its changes were not representative of more general changes.

On the Morale Scale there was a main effect of Group (F(4, 35) = 11.45, p < .001) and of Time (F(1, 35) = 8.90, p = .005) but no Group × Time interaction (F(4, 35) = .87, p = .49). Morale Scale scores were reduced in all groups over time.

For Physical Health Status there was a main effect of Time (F(1, 35) = 28.20, p < .001) and a trend level effect of Group (F(4, 35) = 2.19, p = .09), but no Group × Time interaction (F(4, 35) = .51, p = .73). Ratings of physical health declined in all groups, and persons with PTSD tended to have somewhat worse scores on this scale at both times.

Correlational analyses on the change scores were performed to determine whether the change in PTSD measures were concurrent with changes in general psychiatric symptoms, morale, or physical health, controlling for group. There were significant correlations among changes in the Mississippi PTSD Scale score and SCL-90 (r = .434, p = .04), the Mississippi PTSD Scale and Morale Scale scores (r = -.550, p = .008), and for the SCL-90 and Morale Scale (r= -.495, p = .019). However, changes in physical health status were not significantly associated with changes in these other variables.

In view of these substantial associations, we replicated the analyses of variance controlling for these other self-report measures. When the ANOVA on Mississippi PTSD Scale scores was repeated covarying separately for changes in SCL-90 and Morale Scale scores, the Group × Time interaction was not affected. (F(4, 34) = 3.45, p = .02; F(4, 34) = 3.80, p = .01, respectively). In contrast, when the ANOVA examining differences in SCL-90 was repeated using differences in the Mississippi PTSD Scale scores as covariates, the effect of group was no longer significant (F(4, 34) = 2.81, p = .10). Nonetheless, covariation with differences in Morale did not affect the main effect of Group (F(4, 34) = 6.38, p = .001). When covaried with the change in Mississippi PTSD Scale scores, the effect of Group (F(4, 34) = 9.02, p < .001) on Morale Scale scores were still significant. Similarly, controlling for SCL-90 did not affect Morale. The effects of Group (F(3, 34) = 10.60, p < .001) and of Time (F(1, 34) = 8.02, p = .008) were still significant and the Group × Time interaction remained non-significant (F(4, 34) = .57, p = .69). Overall, these results suggest that with the exception of differences in SCL-90, the observed differences in Group and Time were strong enough so that they are not attributable to associated changes over time.

Discussion

The findings demonstrate that in the sample as a whole, measures of Intrusive symptoms on the CAPS, as well as Mississippi PTSD scores, SCL-90 and physical health were highly correlated between the Time 1 and Time 2 assessments, suggesting that these characteristics are stable (and/or change in the same way over time) in Holocaust survivors. In contrast, Avoidance and Hyperarousal symptoms (and hence, CAPS total scores) and Morale Scale scores were not significantly associated, suggesting that these measures are more reflective of current state. When considering changes between Time 1 and Time 2, there was a decline in Intrusive symptoms, morale and physical health status that was consistent across all five groups. General psychiatric symptoms scored on the SCL-90 did not change over time.

The failure to observe a consistent pattern of symptom decline in the Avoidance, Hyperarousal and Mississippi PTSD Scale scores reflects increased symptomatology in persons who developed PTSD at the later assessment. PTSD onset delayed by decades has been rarely reported among aging trauma survivors, but an assessment technique for this has recently been developed, based on preliminary observations of this phenomenon among WWII, Korean War and Vietnam veterans (26). For the Mississippi PTSD Scale, the Resistant group also displayed higher scores, reflecting a significant increase in PTSD symptoms.

Unlike the Mississippi PTSD Scale, the CAPS did not demonstrate changes over time in the Resistant group. CAPS scores were only elevated from Time 1 to Time 2 in those with Delayed Onset, but not in those whose diagnostic status remained constant or improved. Scores on the other self-report measures confirm that the Resistant subjects not only reported higher scores on the Mississippi PTSD Scale, but also reported lower morale, poorer physical health and higher general psychiatric SCL-90 symptomatology at Time 2 than at Time 1. This discrepancy between the CAPS and the self-report measures may stem from the fact that the raters on the CAPS differed between Time 1 and Time 2, while the same subject reported their own symptoms on the other measures at both assessments. The review and consensus conference of clinician ratings reduces the likelihood that this discrepancy was due to clinician error, per se. A more subtle possibility for error is that the clinicians may have adapted to change, rating symptomatology relative to the group as a whole at each time. Rather, the discrepancy may be attributable to the fact the self-report measures reflect broader ranges of symptoms than the CAPS, which is limited specifically to Intrusive, Avoidance, and Hyperarousal symptoms.

An additional issue beyond the symptom measure is the utility of the diagnostic cut-offs established by the DSM-IV for this group of highly traumatized persons. Although the CAPS has recently been validated for use in older combat veterans (27), in this group of Holocaust survivors, groups with the same diagnosis at a particular time were not necessarily similar in CAPS total symptom severity at that time. Conversely, groups with different diagnoses at a particular time were sometimes not different on this measure. In particular, persons not meeting criteria for PTSD at either Time 1 or Time 2 had higher CAPS total scores at both times if they had met criteria for PTSD in the past (Early Resilience), than if they did not (Resistant). Moreover, subjects who never reportedly met criteria for PTSD at the earlier assessment were more symptomatic at that earlier assessment if they developed PTSD subsequently (Delayed Onset). Persons who developed PTSD at Time 2 had higher CAPS scores at Time 1 than other persons without PTSD at this time. These discrepancies suggest that PTSD symptom severity may be a more relevant clinical variable than PTSD diagnosis in this group, consistent with other findings in aging military veterans (28).

The pattern of symptom change associated with Delayed Onset PTSD was particularly interesting in that this group was similar to the others in showing a decline in Intrusive symptoms at Time 2, while Avoidance and Hyperarousal scores increased. Among the subjects in this group, all of them changed in that they met Avoidance criteria at Time 2 but not at Time 1 and half also changed from not meeting the criterion for Hyperarousal at Time 1 to meeting the criterion at Time 2. In contrast, all subjects in this group already met the criterion for Intrusive symptoms at Time 1, and even exceeded the number of symptoms required for this cluster. Thus, “delayed” PTSD in this group can be understood as a change in the distribution of symptomatology rather than an initiation of previously absent symptomatology. This notion is consistent with recent descriptions of aging combat veterans who develop late-onset stress symptomatology (LOSS), brought about by increased combat-related thoughts, feelings and reminiscence, and also the changes and challenges associated with aging (26). It is also consistent with a recent report of symptom trajectories based on a 20-year longitudinal study of Israeli war veterans (8). Indeed, the Delayed Onset group in the current study notably differed from the others in having experienced a recent traumatic loss.

Although the Delayed Onset group differed from the other groups in demonstrating increased symptom severity on the Avoidance and Hyperarousal subscales and on the Mississippi PTSD scale, it did not exhibit a corresponding difference from the other groups in the SCL-90, Morale Scale, or in physical health status, reflected by an absence of a significant Group x Time interaction. Accordingly, there may be distinct effects of trajectory on PTSD symptoms and Morale, but perhaps SCL-90 changes are secondary to changes in PTSD. This interpretation is further supported by the fact that covariation with Mississippi PTSD Scale scores obliterated the observed effects in SCL-90 scores.

Contrary to other reports in aging trauma survivors, we did not observe a significant association between changes in PTSD symptomatology and decrements in health over time. However, there were trend level differences among the five trajectories in overall health status with lowest health status in the two groups with PTSD at Time 2.

The importance of this study is that it demonstrates that a nuanced characterization of PTSD trajectory over time is more reflective of PTSD symptomatology at some time than simple diagnostic status at that time. The presence of a Delayed Onset trajectory complicates any simplistic overall trajectory summarizing the longitudinal course of PTSD or other psychological symptoms following trauma exposure and highlights the utility of a more adaptive approach. We are only aware of two other reports of longitudinal symptom change in Holocaust survivors, both by our group, reported on overlapping clinical samples distinct from the subjects studied here. These studies did not identify a Delayed Onset subgroup, but rather demonstrated improvements in PTSD symptom severity (29) and dissociation symptoms (30) reported within a 5 and 8 year period, respectively. We did not previously attribute the decline in symptoms over time to the natural longitudinal course of PTSD, since many of the subjects not only sought but received treatment in our clinic. In contrast, the current sample was recruited as a community sample, which had little prior psychiatric treatment at Time 1, and for whom treatment between Time 1 and Time 2 was not provided by our group and not associated with differences in trajectory.

Interpretation of the current findings is constrained by several limitations. Primarily, the small sample size - especially for some of the trajectories - calls for further replication. The effect sizes are reported so that statistical significance is not the only criterion for judging differences between trajectory groups. An additional limitation is the loss of over one third of the original sample to follow-up primarily due to death and/or relocation that often reflected inability to live independently. Though the unavailable group was not different on the variables of interest (PTSD symptom severity) presented here at Time 1, since they tended to be older, this limited the age range of the current sample and precluded an evaluation of the interaction between PTSD and age. Despite the general lessening in PTSD symptoms, the other decrements in self-reported measures suggest that aging trauma survivors continue to decline in many important domains. Thus it is important to follow aging trauma survivors, to describe broadly the patterns of change over time, and distinguish the effects of aging per se from the trajectories of PTSD.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIMH R01 MH 64675-01 entitled “Biology of Risk and PTD in Holocaust Survivor Offspring” and in part by a grant (5 M01 RR00071) for the Mount Sinai General Clinical Research Center from the National Institute of Health. The authors acknowledge Ms. Shira Kaufman and Mr. William Blair for research coordination, and Drs. Lisa Tischler and Alicia Hirsch for diagnostic evaluations and consensus conferencing. The authors report no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

References

- 1.Zeiss RA, Dickman HR. PTSD 40 years later: incidence and person-situation correlates in former POWs. J Clin Psychol. 1989;45:80–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198901)45:1<80::aid-jclp2270450112>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontana A, Rosenheck R. Traumatic war stressors and psychiatric symptoms among World War II, Korean, and Vietnam War veterans. Psychol Aging. 1994;9:27–33. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.9.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kluznik JC, Speed N, Van Valkenburg C, Magraw R. Forty-year follow-up of United States prisoners of war. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1443–1446. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.11.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tennant C, Fairley MJ, Dent OF, Sulway MR, Broe GA. Declining prevalence of psychiatric disorder in older former prisoners of war. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:686–689. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yehuda R, Schmeidler J, Siever LJ, Binder-Brynes K, Elkin A. Individual differences in posttraumatic stress disorder symptom profiles in Holocaust survivors in concentration camps or in hiding. J Trauma Stress. 1997;10:453–463. doi: 10.1023/a:1024845422065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Port CL, Engdahl B, Frazier P. A longitudinal and retrospective study of PTSD among older prisoners of war. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1474–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon Z, Dekel R. Posttraumatic stress disorder among Israeli ex-prisoners of war 18 and 30 years after release. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1031–1037. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon Z, Mikulincer M. Trajectories of PTSD: a 20-year longitudinal study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:659–666. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trappler B, Cohen CI, Tulloo R. Impact of early lifetime trauma in later life: depression among Holocaust survivors 60 years after the liberation of Auschwitz. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:79–83. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000229768.21406.a7. Epub 2006 Oct 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barak Y, Aizenberg D, Szor H, Swartz M, Maor R, Knobler HY. Increased risk of attempted suicide among aging holocaust survivors. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:701–704. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.8.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joffe C, Brodaty H, Luscombe G, Ehrlich F. The Sydney Holocaust study: posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychosocial morbidity in an aged community sample. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16:39–47. doi: 10.1023/A:1022059311147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suedfeld P, Soriano E, McMurtry DL, Paterson H, Weiszbeck TL, Krell R. Erikson's “components of a healthy personality” among Holocaust survivors immediately and 40 years after the war. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2005;60:229–28. doi: 10.2190/U6PU-72XA-7190-9KCT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon Z, Neria Y, Ohry A, Waysman M, Ginzburg K. PTSD among Israeli former prisoners of war and soldiers with combat stress reaction: a longitudinal study. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:554–559. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engdahl B, Dikel TN, Eberly R, Blank A., Jr. Posttraumatic stress disorder in a community group of former prisoners of war: a normative response to severe trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1576–1581. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCranie EW, Hyer LA. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in Korean conflict and World War II combat veterans seeking outpatient treatment. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:427–439. doi: 10.1023/A:1007729123443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins C, Burazeri G, Gofin J, Kark JD. Health status and mortality in Holocaust survivors living in Jerusalem 40-50 years later. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17:403–411. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000048953.27980.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yehuda R, Kahana B, Binder-Brynes K, Southwick SM, Mason JW, Giller EL. Low urinary cortisol excretion in Holocaust survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:982–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yehuda R, Kahana B, Schmeidler J, Southwick SM, Wilson S, Giller EL. Impact of cumulative lifetime trauma and recent stress on current posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in holocaust survivors. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1815–1818. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.12.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mini-Mental State. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID) New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biomedical Research; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, et al. The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keane TM, Weathers FW, Blake D. The Civilian Mississippi Scale. National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Behavioral Science Division; Boston: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale--preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973;9:13–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawton MP. The Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale: a revision. J Gerontol. 1975;30:85–89. doi: 10.1093/geronj/30.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blazer D. Durham Survey: Description and application, in Multi-dimensional Functional Assessment OARS Methdology: A manual. 2nd ed. Duke University Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development; Durham, NC: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 26.King LA, King DW, Vickers K, Davison EH, Spiro A., 3rd Assessing late-onset stress symptomatology among aging male combat veterans. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11:175–191. doi: 10.1080/13607860600844424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schinka JA, Brown LM, Borenstein AR, Mortimer JA. Confirmatory factor analysis of the PTSD checklist in the elderly. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:281–289. doi: 10.1002/jts.20202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dirkzwager AJ, Bramsen I, van der Ploeg HM. The longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among aging military veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:846–853. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200112000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yehuda R, Tischler L, Golier JA, et al. Longitudinal assessment of cognitive performance in Holocaust survivors with and without PTSD. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:714–721. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labinsky E, Blair W, Yehuda R. Longitudinal assessment of dissociation in Holocaust survivors with and without PTSD and nonexposed aged Jewish adults. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:459–462. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]