Abstract

The vagal afferent pathway is important in short-term regulation of food intake, and decreased activation of this neural pathway with long-term ingestion of a high-fat diet may contribute to hyperphagic weight gain. We tested the hypothesis that expression of genes encoding receptors for orexigenic factors in vagal afferent neurons are increased by long-term ingestion of a high-fat diet, thus supporting orexigenic signals from the gut. Obesity-prone (DIO-P) rats fed a high-fat diet showed increased body weight and hyperleptinemia compared with low-fat diet-fed controls and high-fat diet-induced obesity-resistant (DIO-R) rats. Expression of the type I cannabinoid receptor and growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1a in the nodose ganglia was increased in DIO-P compared with low-fat diet-fed controls or DIO-R rats. Shifts in the balance between orexigenic and anorexigenic signals within the vagal afferent pathway may influence food intake and body weight gain induced by high fat diets.

Keywords: cholecystokinin, diet-induced obesity, ghrelin

regulation of food intake and body weight involves both peripheral and central nervous systems, together with endocrine pathways (7). Both short- and long-term regulation of food intake occurs via complex, hierarchical control that maintains body weight within a narrow range. Signals initiated in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract in response to food ingestion are generally thought to be involved in short-term regulation of food intake. Thus the presence of nutrients in the gut lumen decreases food intake by meal termination and reduction in the size of individual meals, but with little or no effect on overall daily food intake (21). Cholecystokinin (CCK), released by fat and protein digestive products in the proximal small intestine, decreases meal size at least in part via activation of CCK1 receptors (CCK1R) expressed by vagal afferent neurons terminating in the gut wall (3, 9, 8). Peptide YY3–36 is an anorexigenic gut hormone released from the distal gut that reduces food intake following exogenous administration (2), possibly also acting at the level of vagal afferent nerve terminals (13).

However, there are hormones and bioactive molecules released by the GI tract that increase food intake and may stimulate appetite. These include ghrelin, a peptide released from the gastric corpus (14), and cannabinoids, such as anandamide (10). These factors are released during the intermeal interval, and plasma levels are highest right before meal initiation (7, 22). There is good evidence that exogenous ghrelin stimulates food intake, acting at least in part via the vagal afferent pathway (8), although this was not confirmed in another study (1).

It was recently shown that expression of peptide receptors by vagal afferent neurons is regulated by nutritional status. Prolonged fasting increases expression of receptors associated with anorexigenic mediators, the cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) and melanocortin concentrating hormone type 1 (MCH-1) receptors; this increase is reversed by feeding or administration of CCK (4, 5). Thus, under normal conditions, GI-derived anorexigenic and orexigenic signals interact to regulate expression levels; this is likely to be important in control of food intake and energy homeostasis. However, there is no information on whether this balance between anorexigenic and orexigenic receptor expression is altered by long-term changes in diet. Chronic ingestion of a high-fat (HF) diet leads to hyperphagia and weight gain. Numerous studies have shown adaptation at the level of the hypothalamus after chronic ingestion of a HF diet (7, 10), but there is evidence to suggest that adaptation to HF foods also can occur in the periphery at the level of the vagal afferent pathway. For example, ingestion of a HF diet decreases vagal afferent activation in response to CCK and to intestinal lipid (21) and diet-induced obesity in mice leads to attenuation of the synergistic action of urocortins and CCK to decrease food intake and delayed gastric emptying (12).

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that adaptation to a HF diet alters expression of gut hormone receptors [CCK1R, Y2 receptor (Y2R), growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR)], leptin receptor (ObR), and cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptor and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), both part of the endocannabinoid system, by vagal afferent neurons. We measured mRNA expression at the level of the vagal afferents by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. It is well established that distinct diet-induced obesity-prone (DIO-P) and -resistant (DIO-R) phenotypes of Sprague-Dawley rat can be revealed by maintenance on a HF diet (15, 16). We measured changes in the metabolic profile (body weight, adiposity, food intake, plasma insulin, and leptin) in rats fed a low-fat (LF) control diet or a HF diet for either 1 wk or following maintenance on the diets for 8 wk.

METHODS

Animals: Diets and Experimental Procedures

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (6 wk of age; Harlan, San Diego, CA) were fed ad libitum a LF diet (Research Diets D12450B) or a HF diet (Research Diets D12451) for 1 or 8 wk. The LF diet provided 3.85 kcal/g of energy {70% carbohydrate, 20% protein, 10% fat [saturated fatty acids (SAT), 25.1%; monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), 34.7%; polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), 40.2%]}, and the HF diet provided 4.73 kcal/g of energy [35% carbohydrate, 20% protein, 45% fat (SAT, 36.3%; MUFA, 45.3%; PUFA, 18.5%)]. Rats were initially housed in pairs for 1 wk and then housed individually in a temperature-controlled room with regular light conditions (lights on at 6:00 AM and off at 6:00 PM). Water was freely available throughout the experiments, and body weight was recorded daily. Food intake was measured daily for the first 3 wk and every 2–3 days thereafter for the duration of the experiment. The HF group weighed 177 ± 4 g (n = 15) and the LF group weighed 176 ± 7 g (n = 10) at the beginning of the experiment [no significant difference (NS)]. All experiments were performed in accordance with protocols reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (University of California, Davis, CA).

Measurement of Plasma Insulin and Leptin

Blood samples were collected from the tail (1 ml in 30 μl of heparin) following a 12-h fast during the light cycle (6:00 PM), at week 1, and at week 8. On a different day, 12-h-fasted rats were gavaged with 1 ml/100 g of lipid emulsion (Intralipid 20%; Baxter HealthCare, Deerfield, IL), and blood samples were collected 2 h after gavage. Blood was centrifuged (1,000 g for 10 min), and the plasma was removed and stored at −80°C. Leptin and insulin were measured by ELISA (catalog no. 22-LEP-E06, lot no. 090107 for leptin; catalog no. 80-INSRTU-E01, lot no. 00208 for insulin; ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH).

Tissue Collection

After 1 or 8 wk on the diets, rats were fasted for 12 h during the light cycle, gavaged with 1 ml/100 g lipid emulsion (Intralipid 20%) and, after 2 h, deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg ip, Nembutal; Abott Laboratories). The rationale for the use of lipid gavage in fasted rats 2 h before euthanasia was to ensure that all animals were in the same nutritional status. A blood sample (2 ml) was obtained from the descending aorta. Tissues were dissected with instruments cleaned with RNA Zap (Ambion, Austin, TX) and collected into 2-ml tubes previously decontaminated with RNA Zap, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Left and right nodose ganglia were collected; epididymal, mesenteric, and retroperitoneal fat pads were dissected and weighed individually. An adiposity index consisting of the summed weight of the three fat pads divided by the final body weight was calculated.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Right and left nodose ganglia were pooled from each individual rat. Samples (10–20 mg) were ground with a mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen. Once powdered, RNA extraction was executed with the RiboPure kit (Ambion); samples were extracted by adding 500 μl of Tri Reagent. Sample integrity was determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA), and RNA concentration was assayed with a NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE).

cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription from 500 ng of total RNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The TaqMan Gene Expression Assay consisted of a FAM dye-labeled TaqMan MGB probe and two PCR primers formulated into a single tube for each target gene (GenBank accession numbers: CCK1R, M88096; Y2R, AY004257; CB1, X55812; FAAH, U72497; Fa, D84550; GHSR, AB001982; and 18S ribosomal, X03205). cDNA (6 μl) diluted 30-fold after reverse transcription was added to each well and allowed to dry overnight. Each PCR was run with 8 μl of a mix containing PCR mix (TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix) using a TaqMan Gene Expression Assay on the ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems). Expected amplicon sizes were confirmed by high-resolution agarose gel electrophoresis.

Analysis of relative gene expression was performed using the 2{↑−ΔΔCT} method (17) using 18S as mRNA loading control. Briefly, the CT (threshold cycle when fluorescence intensity exceeds 10 times the standard deviation of the baseline fluorescence) value for the target amplicon (CCK1R, Y2R, CB1, FAAH, and GHSR) and endogenous control (18S) was determined for each PCR reaction. Each PCR reaction was repeated in triplicate (17). The sample expression levels are expressed as an n-fold difference relative to those found in the average low-fat (week 1) nodose ganglia expression level.

Statistical Analysis

Body weight and composition, plasma leptin, and insulin.

A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was performed with time, diet, and time-diet interactions as independent variables. All analyses were conducted using SigmaStat (version 3.11; Systat Software). Differences among group means were analyzed using multiple comparison procedures (Holm-Sidak method) and were considered significant if P < 0.05. One HF week 1 and one LF week 8 rat died during gavage, explaining the difference in group size between body weight data and gene expression data.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Data are presented as the adjusted mean 2{↑−ΔΔCT} ± SE. Statistical analysis of the differences in mRNA levels was performed using two-way ANOVA with time, diet, and time-diet interactions as independent factors. Differences among group means were analyzed using multiple comparison procedures (Holm-Sidak method) and were considered significant if P < 0.05 (SigmaStat version 3.11).

Principal component analysis.

Principal components analyses (PCA) were performed on data sets using the Excel add-in developed by the Bristol Centre for Chemometrics (http://www.chm.bris.ac.uk/org/chemometrics/index.html). Before PCA were performed, quantitative results for each variable were transformed by vast scaling as described previously (23) using the following equation:

|

(1) |

This transformation provided better separation of experimental groups than either autoscaling, i.e., data transformed to unit standard deviation, or pareto scaling, i.e., data transformed to unit standard error of the mean.

RESULTS

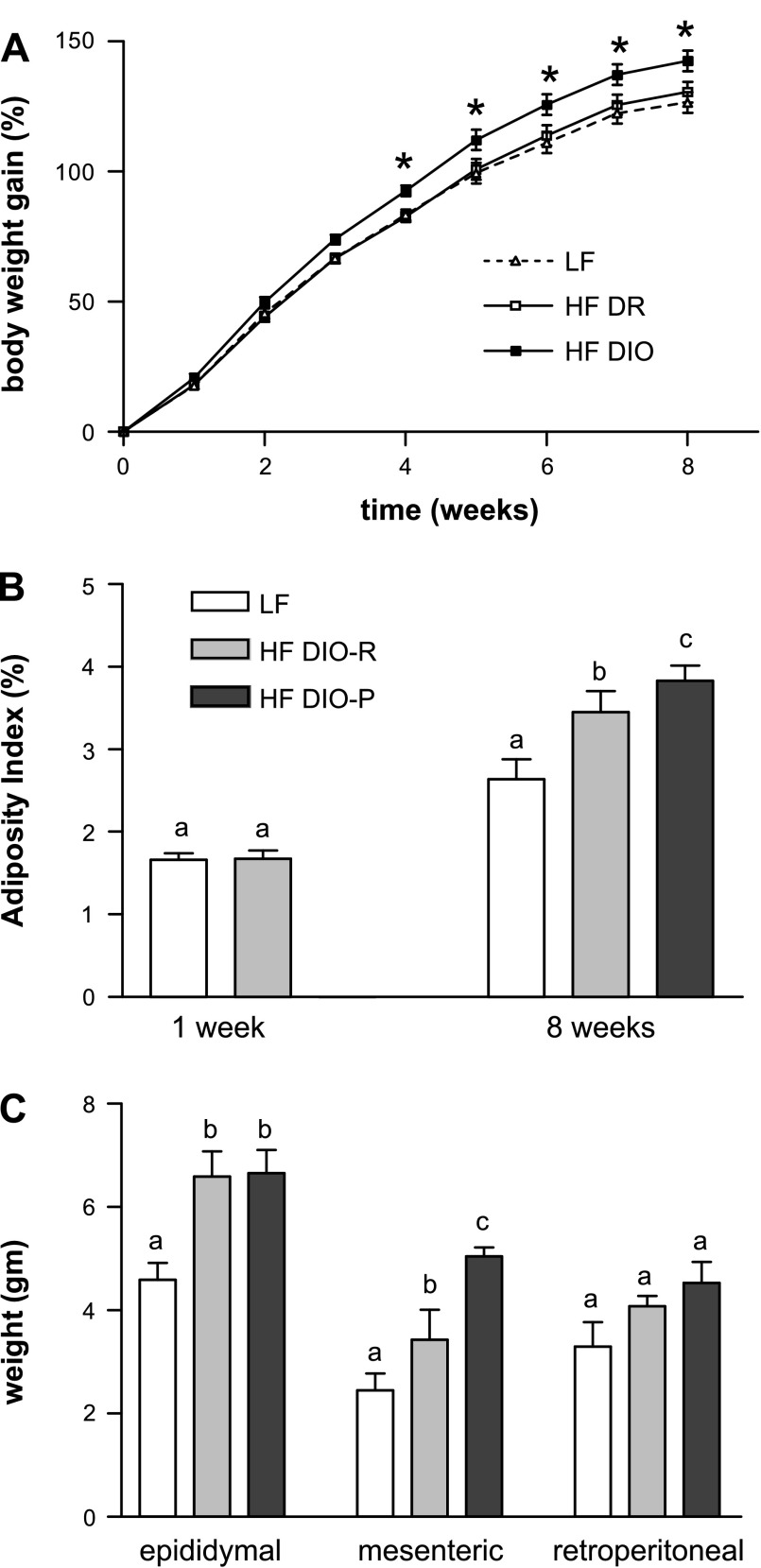

Within the HF group, two distinct phenotypes emerged by week 3; in a subgroup of HF rats, there was a significant increase in body weight gain compared with LF rats (Fig. 1A). HF rats with the highest terminal body weight were designated DIO-P; body weight was significantly greater in this group than in both DIO-R and LF groups (P < 0.05). There were no differences in body weight between DIO-R and LF groups at any time point (NS).

Fig. 1.

Effect of ingestion of a high-fat (HF) diet on body weight gain, adiposity, and fat pad mass in low-fat (LF) and HF rats after 1 and 8 wk on respective diets. A: diet-induced obesity-prone (DIO-P) rats had a significant increase in body weight (expressed as a percentage of initial body weight) at 3–8 wk compared with diet-induced obesity-resistant (DIO-R) or LF rats (LF or DIO-R vs. DIO-P, P < 0.05). B: adiposity index calculated as the sum of fat pads expressed as a percentage of body weight. Note that at week 1, rats divided into 2 groups, either LF or HF, as cannot be discriminated into DIO-R and DIO-P groups. There was a significant increase in adiposity in DIO-R and DIO-P rats compared with rats maintained on LF diet (LF vs. DIO-R or DIO-P, P < 0.05). C: mass of different fat pads. There was a significant difference in mesenteric fat pad mass between DIO-R and DIO-P rats after 8 wk on a HF diet (P < 0.05). Data are means ± SE (LF, n = 10; DIO-R, n = 7; and DIO-P, n = 8). a,b,cDifferent letters denote significant differences between groups.

There was no significant difference in the adiposity index between the LF or HF rats at week 1. At week 8, the DIO-P group had a higher adiposity index than the LF rats (P = 0.005), whereas the DIO-R group did not ( P = 0.06; Fig. 1B); there was no significant difference in the adiposity index between the DIO-P and DIO-R groups (P = 0.3). However, there were significant differences in the weights of individual fat pads between groups (Fig. 1C). DIO-P rats had significantly larger mesenteric fat pad weight than either the DIO-R or LF rats (LF vs. DIO-P, P < 0.001; DIO-R vs. DIO-P, P < 0.05). Both DIO-R and DIO-P rats had significantly larger epididymal fat pad weight than LF rats (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in the retroperitoneal fat pad weight among any groups (P ≥ 0.09).

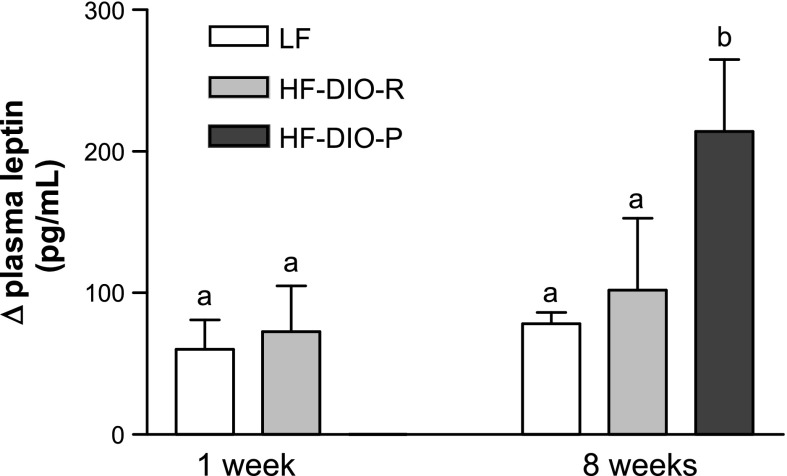

After 8 wk on a HF diet, DIO-P rats had a significantly higher caloric intake than DIO-R or LF rats (week 1: LF vs. HF, 67 ± 4 vs. 60 ± 6 kcal/day, P = 0.04; week 8: LF vs. DIO-R, 73 ± 4 vs. 66 ± 9 kcal/day, P = 0.2, and LF vs. DIO-P, 73 ± 4 vs. 94 ± 7 kcal/day, P < 0.001; n = 5 in each group). There was no significant difference in fasting plasma level of leptin at 1 wk; however, after 8 wk on the diets, DIO-R and DIO-P had higher fasting plasma leptin level compared with LF rats, consistent with higher adiposity (week 1: LF, 339 ± 80 pg/ml; HF, 431 ± 101 pg/ml; week 8: LF, 372 ± 49 pg/ml; DIO-R, 816 ± 67 pg/ml; DIO-P, 755 ± 136 pg/ml; P = 0.003). The increase in plasma leptin between the fasted state and 2 h after gavage with a lipid load was significantly higher in the DIO-P rats compared with LF (P < 0.05) but not DIO-R rats (P = 0.2; Fig. 2). There was no significant difference in fasting insulin between LF rats or DIO-R and DIO-P rats at 8 wk (week 8: LF vs. DIO-R vs. DIO-P, 0.97 ± 0.11 vs. 1.07 ± 0.18 vs. 1.01 ± 0.13 ng/ml; NS).

Fig. 2.

The increase in plasma leptin concentration between fasted state and 2 h after oral lipid gavage was significantly higher in DIO-P than in LF or DIO-R rats after 8 wk on a HF diet. Data are means ± SE (week 1: LF, n = 5; HF, n = 5; week 8: LF, n = 4; DIO-R and DIO-P, n = 5). a,bP < 0.05, different letters denote significant differences between groups.

Nodose Ganglion Receptor Expression

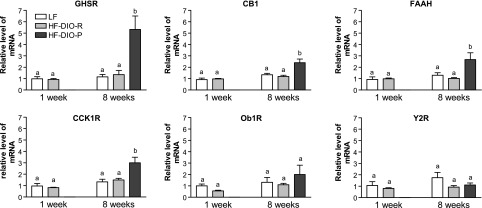

After 8 wk on the LF or HF diet, there was an increased expression of CB1 (2 ± 0.7-fold), CCK1R (3 ± 1-fold), and GHSR1a (5 ± 3-fold) in the DIO-P rats compared with either the DIO-R or LF rats (Fig. 3). There was no significant difference in the gene expression of Ob1R and Y2R among any groups.

Fig. 3.

Cholecystokinin receptor (CCK1R), growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR), cannabinoid type 1 receptor (CB1), and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) expression in the nodose ganglia are significantly increased in DIO-P but not DIO-R rats. No change was observed for Y2 receptor and leptin receptor (Ob1R). Receptor expression was expressed relative to LF rats at week 1 as a control group. Data are means ± SE (week 1: LF, n = 5; HF, n = 5; week 8: LF, n = 4; DIO-R, n = 5; DIO-P, n = 5).

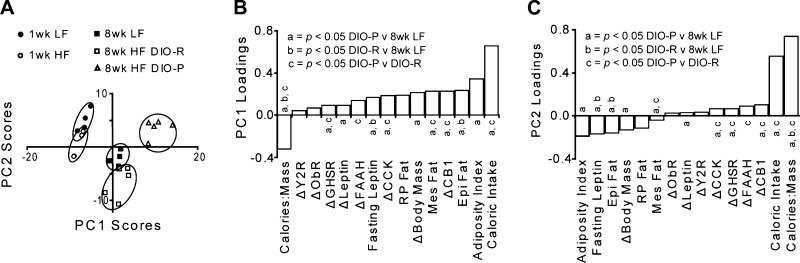

Discrimination of DIO-P and DIO-R Phenotype

As shown above, multiple differences were identified among the experimental groups. By using the aggregated data set and the unsupervised multivariate analysis PCA to discriminate experimental groups, the relative weight each factor has in separating these groups was evaluated within a single analysis. Considering the entire data matrix, rats at week 1 could not be discriminated, despite maintenance on the different diets, but were distinct from rats at week 8 (Figs. 4 and 5). The daily caloric intake, mass specific caloric intake (i.e., kcal·day−1·g body wt−1), and adiposity index were the most powerful discriminates of animals by age and diet, discriminating LF and DIO-R from DIO-P animals at 8 wk. Moreover, the changes in nodose ganglion expression profiles were powerful factors separating the experimental groups, and in this aggregate analysis, the variance within the data set after vast scaling was not different among groups (F test, P > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Principle component analysis of all measured parameters from all rat groups after vast scale transformation of the data reveals the phenotypic shifts responsible for group changes in a single evaluation. Within-group variance was equivalent after transformation, and experimental groups are clearly discriminated. The first 2 principle components accounted for 86% of the variance in the data set. The 8-wk HF DIO-R animals differed from the 8-wk LF group in PC2 (P = 0.03) but not PC1 (P = 0.6), whereas the 8-wk HF DIO-P group differed from the LF group in both components (P < 0.001).

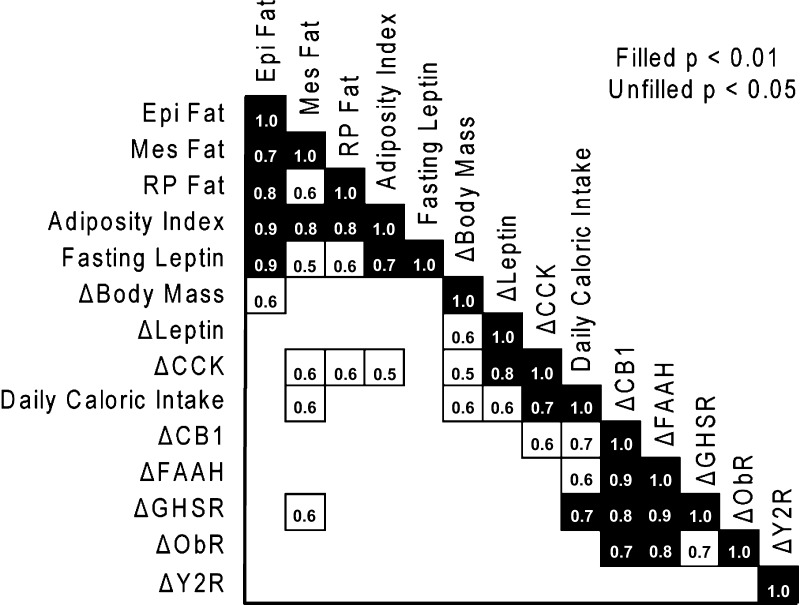

Fig. 5.

Correlations between variables were assessed in a Pearson's correlation matrix with all measured variables. Notably, fasting leptin was strongly correlated with epididymal fat mass but weakly correlated with other adipose depots measured. Also of specific interest, the change in CCK1R expression in nodose ganglion was strongly correlated with the fasting to 2-h post-lipid challenge leptin.

DISCUSSION

The results from the present study demonstrate that expression of receptors for gut-derived orexigenic factors (ghrelin and cannabinoids) in the nodose ganglion increase in rats chronically ingesting a HF diet and prone to obesity, but not in rats fed the same diet but resistant to the obesigenic effects of the HF diet. This increase in receptor expression is accompanied by an increase in food intake in DIO-P rats compared with DIO-R rats; these data suggest that an increase in expression of orexigenic receptors by vagal afferent neurons may increase food intake via peripherally acting ghrelin and endogenous cannabinoids. This increase in receptor expression is not dependent solely on the ingestion of a HF diet but is only evident in rats susceptible to the obesigenic effects of ingesting HF diets, that is, rats with an increase in body weight and circulating leptin and a significantly greater mesenteric fat pad mass. Whether this change in receptor expression is driving the hyperphagia and weight gain or is secondary to these metabolic changes is not clear from the present study. We have previously shown that rats fed a HF diet became hyperphagic on a HF diet predominantly via an increase in meal size (18), suggesting a decreased satiation. The predominant effect of exogenous ghrelin on food intake is to decrease latency to feeding; ghrelin action is mediated at least in part via the vagal afferent pathway (8), although other investigators have not been able to confirm this finding (1). It was recently shown that there is considerable short-term regulation of receptor expression, at the level of both RNA and protein, in vagal afferents (4, 5). Prolonged (48 h) fasting increases expression of CB1 and MCH-1 receptors; this is reversed by feeding or by exogenous CCK acting via a CCK1R mechanism. Prolonged fasting did not change expression of GHSRs, but administration of ghrelin counteracted the decrease in the CB1/MCH1 receptors in response to refeeding or CCK (4). Thus an increase in GHSR expression in response to high fat feeding might result in an increased orexigenic drive and an increase in food intake due to an increase in CB1 receptor expression and possibly MCH-1 receptor. Levels of protein were not measured in the current study; however, there is good agreement between levels of mRNA and protein for these receptors (4, 5). It is interesting to note there is evidence from the ghrelin or GHSR null mice model to suggest that ghrelin signaling is required for development of the full phenotype of diet-induced obesity (24, 25).

The increase in CCK1R expression was surprising given functional data to suggest a decrease in activation of the vagal afferent pathway by CCK when rats are maintained on a HF diet (21). It is possible that there is altered coupling between receptor and intracellular signaling pathways or changes in synaptic activity at the level of the nucleus of the solitary tract, where vagal afferents terminate. There is data to suggest decreased FAAH expression and/or activity as a result of obesity or high fat intake (10); in the current study, we have shown that FAAH is correlated with CB1 expression in the nodose ganglia. It is interesting to note the expression of FAAH in the nodose ganglia, suggesting that there may be regulation of the endocannabinoids at the level of the vagal afferents in conjunction with the CB1 receptor.

It is well-documented that Sprague-Dawley rats fall into two broad groups, those that gain significant weight on a HF diet and those that seem relatively resistant to the obesigenic effects of a HF diet (15, 16). In the current study, we have presented an original way to discriminate DIO-P from DIO-R rats beyond using body weight gain alone. We performed a PCA using a variety of phenotypic outcomes successfully differentiating cohorts, highlighting that phenotypic “signatures” may be used as a tool to predict diet-induced obesity. It is interesting to note that there were no significant differences in the overall adiposity of the two groups of HF rats, which were both significantly increased over that of the LF rats. However, if the different fat depots are examined separately, it can be seen that there is an increase in mesenteric, but not epididymal or retroperitoneal, fat mass in the DIO-P animals. Mesenteric fat is thought to be a source of inflammatory mediators that can influence the GI tract and distant organs (6). It is also interesting to note that fasting plasma levels of leptin did not reflect the overall increase in adiposity; in the DIO-R rats, there was a tendency for an increase in plasma levels of leptin as would be expected with an increase in fat pad mass; however, this did not reach significance. There was no difference in fasting plasma levels of insulin in either high fat-fed group, suggesting that the animals were not insulin resistance after 8 wk on the diets. Although the mechanism by which receptor expression in vagal afferent neurons is changed in response to the HF diets in DIO-P is not the focus of the present study, it is interesting to speculate on the role of inflammatory mediators released from the mesenteric fat on vagal afferent nerve terminals.

Together, these data suggest that the gut-brain axis, in addition to metabolic changes associated with a chronic ingestion of a HF diet, is modified by the diet, leading to altered short-term control of food intake toward an orexigenic system and an increase in food intake. The increase in the expression of orexigenic receptors CB1 and GHSR1a might lead to an increase peripheral hunger signals and thus contribute to hyperphagia when ingesting a HF diet. The data also show a paradoxical increase in expression of CCK1Rs; however, it remains to be determined whether this is associated with altered receptor signaling as several studies have shown a decrease in vagal afferent response to CCK in rats maintained on HF diets.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-41004 (to H. E. Raybould), U.S. Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service (USDA/ARS) Intramural Current Research Information System Grant 5306-51530-016-00D (to S. H. Adams and J. W. Newman), and a USDA/ARS Postdoctoral Fellowship (to T. A. Knotts).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold M, Mura A, Langhans W, Geary N. Gut vagal afferents are not necessary for the eating-stimulatory effect of intraperitoneally injected ghrelin in the rat. J Neurosci 26: 11052–11060, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batterham RL, Cowley MA, Small CJ, Herzog H, Cohen MA, Dakin CL, Wren AM, Brynes AE, Low MJ, Ghatei MA, Cone RD, Bloom SR. Gut hormone PYY(3–36) physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature 418: 650–654, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bi S, Chen J, Behles RR, Hyun J, Kopin AS, Moran TH. Differential body weight and feeding responses to high-fat diets in rats and mice lacking cholecystokinin 1 receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R55–R63, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burdyga G, Lal S, Varro A, Dimaline R, Thompson DG, Dockray GJ. Expression of cannabinoid CB1 receptors by vagal afferent neurons is inhibited by cholecystokinin. J Neurosci 24: 2708–2715, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burdyga G, Varro A, Dimaline R, Thompson DG, Dockray GJ. Ghrelin receptors in rat and human nodose ganglia: putative role in regulating CB-1 and MCH receptor abundance. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290: G1289–G1297, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calabro P, Yeh ET. Intra-abdominal adiposity, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk: new insight into global cardiometabolic risk. Curr Hypertens Rep 10: 32–38, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coll AP, Farooqi IS, O'Rahilly S. The hormonal control of food intake. Cell 129: 251–262, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Date Y, Murakami N, Toshinai K, Matsukura S, Niijima A, Matsuo H, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. The role of the gastric afferent vagal nerve in ghrelin-induced feeding and growth hormone secretion in rats. Gastroenterology 123: 1120–1128, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donovan MJ, Paulino G, Raybould HE. CCK1 receptor is essential for normal meal patterning in mice fed high fat diet. Physiol Behav 92: 969–974, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engeli S Dysregulation of the endocannabinoid system in obesity. J Neuroendocrinol 20, Suppl 1: 110–115, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez R, Navarro M, Ferrer B, Trigo JM, Bilbao A, Del Arco I, Cippitelli A, Nava F, Piomelli D, Rodríguez de Fonseca F. A peripheral mechanism for CB1 cannabinoid receptor-dependent modulation of feeding. J Neurosci 22: 9612–9617, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gourcerol G, Wang L, Wang YH, Million M, Taché Y. Urocortins and cholecystokinin-8 act synergistically to increase satiation in lean but not obese mice: involvement of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor-2 pathway. Endocrinology 148: 6115–6123, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koda S, Date Y, Murakami N, Shimbara T, Hanada T, Toshinai K, Niijima A, Furuya M, Inomata N, Osuye K, Nakazato M. The role of the vagal nerve in peripheral PYY3–36-induced feeding reduction in rats. Endocrinology 146: 2369–2375, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature 402: 656–660, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levin BE, Triscari J, Sullivan AC. Altered sympathetic activity during development of diet-induced obesity in rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 244: R347–R355, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levin BE, Triscari J, Sullivan AC. Metabolic features of diet-induced obesity without hyperphagia in young rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 251: R433–R440, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oort PJ, Warden CH, Baumann TK, Knotts TA, Adams SH. Characterization of Tusc5, an adipocyte gene co-expressed in peripheral neurons. Mol Cell Endocrinol 276: 24–35, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulino G, Darcel N, Tome D, Raybould H. Adaptation of lipid-induced satiation is not dependent on caloric density in rats. Physiol Behav 93: 930–936, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raybould HE Mechanisms of CCK signaling from gut to brain. Curr Opin Pharmacol 7: 570–574, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato M, Nakahara K, Miyazato M, Kangawa K, Murakami NJ. Regulation of GH secretagogue receptor gene expression in the rat nodose ganglion. J Endocrinol 194: 41–46, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savastano DM, Covasa M. Adaptation to a high-fat diet leads to hyperphagia and diminished sensitivity to cholecystokinin in rats. J Nutr 135: 1953–1959, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strader AD, Woods SC. Gastrointestinal hormones and food intake. Gastroenterology 128:175–191, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van den Berg RA, Hoefsloot HCJ, Westerhuis JA, Smilde AK, van der Werf MJ. Centering, scaling, and transformations: improving the biological information content of metabolomics data. BMC Genomics 7: 142–157, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wortley KE, del Rincon JP, Murray JD, Garcia K, Iida K, Thorner MO, Sleeman MW. Absence of ghrelin protects against early-onset obesity. J Clin Invest 115: 3573–3578, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zigman JM, Nakano Y, Coppari R, Balthasar N, Marcus JN, Lee CE, Jones JE, Deysher AE, Waxman AR, White RD, Williams TD, Lachey JL, Seeley RJ, Lowell BB, Elmquist JK. Mice lacking ghrelin receptors resist the development of diet-induced obesity. J Clin Invest 115: 3564–3572, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]