Abstract

In this study, we determined rates of lysine metabolism in fetal sheep during chronic hypoglycemia and following euglycemic recovery and compared results with normal, age-matched euglycemic control fetuses to explain the adaptive response of protein metabolism to low glucose concentrations. Restriction of the maternal glucose supply to the fetus lowered the net rates of fetal (umbilical) glucose (42%) and lactate (36%) uptake, causing compensatory alterations in fetal lysine metabolism. The plasma lysine concentration was 1.9-fold greater in hypoglycemic compared with control fetuses, but the rate of fetal (umbilical) lysine uptake was not different. In the hypoglycemic fetuses, the lysine disposal rate also was higher than in control fetuses due to greater rates of lysine flux back into the placenta and into fetal tissue. The rate of CO2 excretion from lysine decarboxylation was 2.4-fold higher in hypoglycemic than control fetuses, indicating greater rates of lysine oxidative metabolism during chronic hypoglycemia. No differences were detected for rates of fetal protein accretion or synthesis between hypoglycemic and control groups, although there was a significant increase in the rate of protein breakdown (P < 0.05) in the hypoglycemic fetuses, indicating small changes in each rate. This was supported by elevated muscle specific ubiquitin ligases and greater concentrations of 4E-BP1. Euglycemic recovery after chronic hypoglycemia normalized all fluxes and actually lowered the rate of lysine decarboxylation compared with control fetuses (P < 0.05). These results indicate that chronic hypoglycemia increases net protein breakdown and lysine oxidative metabolism, both of which contribute to slower rates of fetal growth over time. Furthermore, euglycemic correction for 5 days returns lysine fluxes to normal and causes an overcorrection of lysine oxidation.

Keywords: pregnancy; intrauterine growth restriction, glucose; amino acids

glucose, lactate, and amino acids are the primary substrates for energy production and tissue growth in the fetus. Both sufficient supply and appropriate balance of these nutrient substrates are necessary to promote optimal fetal energy metabolism and growth rates. Experiments among a variety of models of fetal under nutrition have shown characteristic fetal metabolic responses. Specifically for experimental conditions that limit the supply of glucose to the fetus and cause fetal hypoglycemia (e.g., maternal under feeding, insulin-induced hypoglycemia, or partial placental ablation) (5, 6, 8, 13), two characteristic metabolic changes occur. First, fasting acutely reduces fetal glucose supply, leading to fetal hypoglycemia and increased amino acid oxidation, which maintains fetal oxidative metabolism (measured as the rate of fetal oxygen consumption) (30). Second, over longer periods of reduced glucose supply, fetal glucose uptake decreases 75%, but glucose utilization is reduced by only 20% and glucose oxidation is not reduced at all due the appearance of endogenous fetal glucose production (8). This indicates that, in contrast to acute glucose deprivation when amino acids produced by protein breakdown directly substitute for glucose for oxidation (30), eventually chronic glucose deprivation leads to fetal glucose production, allowing for maintained glucose oxidation and conservation of amino acids for protein turnover (6, 8). If the glucose deprivation in this case is singular, i.e., oxygen and amino acid supplies are normally abundant, oxidative metabolism can be maintained.

The metabolic adaptations to acute glucose deprivation appear to be correctable by simple reintroduction of glucose (9, 10). In contrast, there has been little investigation to determine whether the metabolic adaptations to chronic glucose deprivation are permanent (“programmed”) or remedial by reintroduction of glucose. In our previous study, in which we examined pancreatic β-cell function following 2 wk of persistent glucose deprivation and hypoglycemia that also produced an 18% reduction in fetal weight, we found that 5 days of euglycemic correction resulted in a correction of fetal weights (13). Factors responsible for this catchup growth did not include increased tissue water content, a greater male/female sex ratio, or differences in gestational age.

To confirm this rapid recovery in growth in the hypoglycemic euglycemic correction group and test whether adaptations in amino acid metabolism and accretion rates could explain these findings, we studied the rate and distribution of lysine disposal into fetal compartments in fetal sheep during chronic hypoglycemia and following euglycemic recovery and compared results with normal, age-matched euglycemic control fetuses. Lysine was selected because it is an essential amino acid that is abundant in body proteins and its deamination product is not reused for lysine resynthesis (19). In addition, the rate of lysine accretion in the sheep fetus exceeds its net uptake rate from the placenta by only ∼10%, indicating that the major pathway for lysine disposal is into protein accretion (2). Furthermore, the fetal plasma concentration of lysine increases in response to chronic hypoglycemia and decreases in response to normalization of glucose concentration (13), indicating that it might be a good measure of the effect of glucose supply and concentration on net protein accretion.

In our model of experimental hypoglycemia, umbilical glucose uptake by the fetus is restricted, yet after 2 wk of reduced fetal glucose uptake and fetal hypoglycemia, fetal glucose oxidative metabolism remains at or only slightly below normal rates, fueled in part by the development of fetal endogenous glucose production (8). Thus, energy supplied by the placenta in the form of glucose, which supports fetal protein metabolism, is reduced. Therefore, we also measured factors regulating protein accretion and degradation in the skeletal muscle to identify possible shifts in the balance of protein synthesis and degradation that might occur in response to the reduced glucose supply. We examined muscle RING finger 1 (MuRF1) and muscle atrophy F-box (MAFbx-1), two ubiquitin ligases shown to promote muscle atrophy and found to increase in response to nutrient deprivation (3, 11). In addition, we measured skeletal muscle eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) content and phosphorylation status along with other members of the insulin-signaling pathway to determine regulation of protein synthesis (4). Skeletal muscle glycogen concentration was measured to determine whether glycogen breakdown also might support fetal oxidative metabolism in addition to the oxidation of glucose produced by the fetus (endogenous glucose production) and amino acids released by protein breakdown.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation.

Studies were conducted during the final 20% of gestation in pregnant Columbia-Rambouillet ewes carrying singletons [term = 147 days gestational age (dGA)]. Indwelling catheters were surgically placed into the maternal and fetal vasculature at 115–125 dGA for blood sampling, and animals were maintained as described previously (6, 13, 14, 16). All animal procedures were in compliance with guidelines of the US Department of Agriculture, the National Institutes of Health, and the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. The animal care and use protocols were approved by the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Experimental design.

Pregnant ewes were randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups: euglycemia control (n = 8), chronic hypoglycemia (n = 8), and chronic hypoglycemia with euglycemic recovery (n = 7) animals. The control ewes were age matched and maintained in the laboratory alongside the hypoglycemic and recovery ewes. The hypoglycemic ewes received a chronic intravenous insulin infusion (30–60 pmol·min−1·kg−1, Humulin R; Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) and saline (0.9% NaCl; Abbott Laboratories) to lower maternal plasma glucose concentrations by 50%. Lysine metabolism was determined in hypoglycemic fetuses after 14 ± 0.3 days of chronic hypoglycemia treatment (range 13–16 days of treatment). The recovery ewes were made chronically hypoglycemic (1.9 ± 0.1 mmol/l, not different from hypoglycemic ewes) for 13 days (range 12–13 days), and then their glucose concentrations were corrected by slowly lowering the insulin infusion rate over 4 days until no exogenous insulin was being administrated. The recovery fetuses were studied on the 4th (n = 1) and 5th (n = 5) days of euglycemic recovery. Two fetuses were examined twice, first on the 2nd or 3rd day of euglycemic recovery and then again on the 5th day of recovery. Patency of the catheter in umbilical vein was lost in one recovery fetus prior to the metabolic study being performed, leaving six fetuses studied in the recovery group.

The metabolic study was designed to measure fetal lysine metabolism with the use of l-[U-14C]lysine and 3H2O as tracers (New England Nucleotides; PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA). On the day of the study, time 0 samples were collected for background-specific radioactivities of lysine, 14CO2, and 3H2O. Each fetus was then infused with a solution of l-[U-14C]lysine (5 μCi/ml) and 3H2O (14 μCi/ml) into the venous catheter placed in the inferior vena cava. A bolus of l-[U-14C]lysine (10 μCi) and 3H2O (28 μCi) was given as a priming dose and was followed by a constant infusion of l-[U-14C]lysine (0.17 μCi/min) and 3H2O (0.47 μCi/min). After 2 h of tracer infusion, when the free lysine concentration had reached a plateau according to preliminary experiments, six blood samples were collected at 15- to 20-min intervals to determine blood flow rate, blood oximetry, plasma metabolites, and hormone concentration. Steady-state condition during the sampling period was confirmed during the sampling period when arterial plasma free l-[U-14C]lysine (dpm/ml) concentrations varied less than ±10% of the mean and showed no systematic trend with time. After each blood collection, maternal blood was given to the fetus to avoid fetal anemia.

Biochemical analysis.

Blood oxygen saturation and hemoglobin concentrations were measured with an ABL 520 blood gas analyzer (Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Oxygen content was determined as the product of oxygen saturation and oxygen capacity. The pH, Po2, and hematocrit were determined at 39.2°C (mean laboratory core body temperature) (24).

Whole blood collected in EDTA-coated syringes was centrifuged (14,000 g) for 3 min at 4°C. Plasma was aspirated from the pelleted red blood cells and stored at −70°C for hormone and amino acid measurements. Plasma glucose and lactate concentrations were measured immediately using a YSI model 2700 Select Biochemistry Analyzer (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). Arterial amino acid concentrations were measured using a Dionex 300 model 4500 amino acid analyzer (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) after deproteinization with sulfosalicyclic acid. Plasma insulin concentrations were measured with an ovine insulin ELISA (Mercodia, Winsten-Salem, NC).

l-[U-14C]lysine incorporates into small plasma proteins that remained in the supernatant after deproteinization (19). To separate the free l-[U-14C]lysine and unlabeled amino acids from these plasma proteins, we used cation exchange chromatography. The cation exchange resin AG 50W-X8 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was added to water to form a slurry, which was used to fill glass wool-plugged pasture pipettes with a 2-cm packed volume. The columns were washed with distilled water (20 ml). In preparation for the columns, the fetal plasma (0.5 ml) pH was lowered to <2.0 with 200 μl of 1 mol/l HCl, mixed, and then added to the AG 50W-X8 column. The resin was washed with 4 ml of distilled water, and the amino acids were eluted with 4 ml of 2 mol/l NH4OH. The eluant pH was neutralized with concentrated HCl and dried. The amino acid fraction was resuspended in 0.01 mol/l HCl and divided for amino acid measurements (by HPLC) and scintillation counting in BioSafe II scintillation cocktail (Research Products International, Mount Prospect, IL). The recovery for each separation was determined, and all were >90%. We confirmed that the cation exchange chromatography separated the free l-[U-14C]lysine from the incorporated l-[U-14C]lysine by size exclusion chromatography with Sephadex G-75, as reported previously by Meier et al. (19). Correction for recovery efficiency and volume displacement was accounted for in our calculations for lysine arterial-specific activity (dpm/nmol).

Postmortem exam.

After completion of physiological studies, fetal tissues were collected under treatment conditions by anesthetizing the ewe and fetus with ketamine (4.4 mg/kg) and diazepam (0.11 mg/kg). The fetus was removed by hysterotomy and weighed. The fetus was killed by surgical dissection and removal of all internal organs to measure its weight. The ewe was killed with concentrated pentobarbital sodium (Sleepaway, Fort Dodge Animal Health) given intravenously immediately after removal of the fetus.

Calculations.

The rate of umbilical blood flow (f; ml·min−1·kg−1) was calculated using the transplacental steady-state diffusion technique, with tritiated water as the blood flow indicator, and normalized to fetal weight during the study (6, 15, 20). Net umbilical uptakes rates (Rf,p; μmol·min−1·kg−1) for oxygen, glucose, and lysine by the fetus from the placenta were calculated as the product of the umbilical blood (or plasma) flow and concentration difference between the umbilical vein (Cv) and umbilical artery (Ca) blood (O2) or plasma (glucose and lysine) concentrations [Rf,p = f(Cv − Ca)] (6, 25).

Net tracer fluxes (dpm/kg) of l-[U-14C]lysine (LysRp,f) and 14CO2

to the placenta from the fetus were calculated as the product of umbilical blood flow (ml·min−1·kg−1 fetal weight) and umbilical arteriovenous concentration blood difference (dpm/ml).

to the placenta from the fetus were calculated as the product of umbilical blood flow (ml·min−1·kg−1 fetal weight) and umbilical arteriovenous concentration blood difference (dpm/ml).

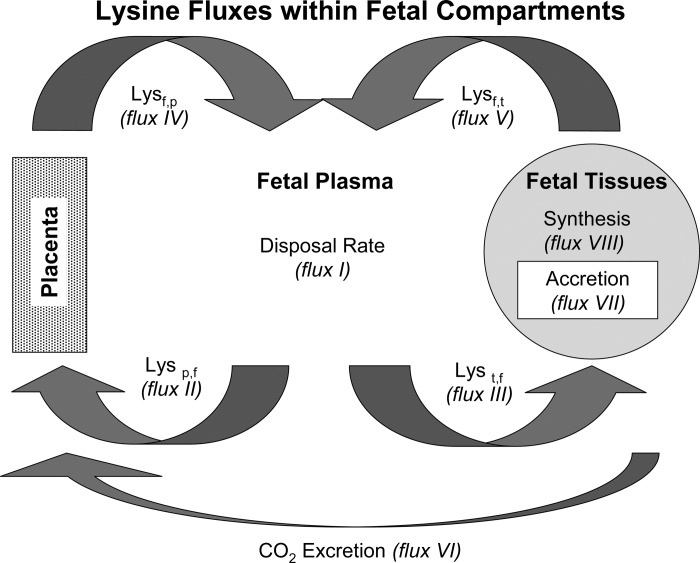

Calculations for tracer fluxes between the placenta and the fetal plasma and between the fetal plasma and fetal tissues were adapted from Loy and colleagues (17, 18), Ross et al. (25), and Carver et al. (6) (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Calculations for lysine fluxes

| Description | Product Symbol | Equation |

|---|---|---|

| Fraction of lysine tracer infusion rate taken up by the placenta | LysΦumb | = LysRp,f/If,0 |

| Fraction of metabolized l-[U-14C]lysine secreted as 14CO2 via the umbilical circulation | CO2Φumb | = CO2Rp,f/If,0 |

| DR | FluxI | = I × f,0/(Sa − [If,0]) |

| Back flux of lysine from umbilical circulation to the placenta | FluxII | = DR × (LysΦumb) |

| Lysine flux into fetal tissues | FluxIII | = DR × (1 − LysΦumb) |

| Net umbilical uptake rate | FluxIV | = LysRf,p + flux II |

| Lysine flux into plasma from fetal tissues | FluxV | = DR − flux IV |

| CO2 production from fetal lysine | FluxVI | = DR × CO2Φumb |

| Lysine for protein accretion | FluxVII | = LysRf,p − flux VI |

| Protein synthesis | FluxVIII | = flux VII + flux V |

If,0, l-[U-14C]lysine fetal infusion rate (dpm/min); Sa, specific activity (dpm/μmol); DR, disposal rate (μmol/min); LysRf,p, net flux of lysine into the fetus from the placenta; LysRp,f, net flux of lysine into the placenta from the fetus.

Fig. 1.

Model of lysine fluxes between placenta (p), fetal plasma (f), and fetus tissues (t) estimated by mass balance of l-[U-14C]lysine (tracer) and l-lysine (tracee).

Skeletal muscle analysis.

Skeletal muscle from the biceps femoris was collected because it was easily accessed and contains a mixture of muscle fiber types. The tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until further analysis. The tissue analysis was performed on 13 control fetuses, 15 hypoglycemic fetuses, and 12 recovery fetuses; selected data from some of these fetuses have been reported previously (13, 27). Skeletal muscle glycogen content was determined as described previously (1), and results are expressed as milligrams of glycogen per gram of skeletal muscle (wet weight).

For mRNA analysis, total RNA was extracted from pulverized skeletal muscle (200 mg) and reverse transcribed into complimentary DNA (cDNA), as described previously (15). Ovine F-box-only protein 32 (FBXO32; MAFbx-1) and ovine ring finger protein 28 (RFP28; MuRF1) (GenBank accession nos. EU492872 and EU525163, respectively) were cloned from ovine skeletal muscle cDNA by PCR (reagents obtained from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA was amplified with the following oligonucleotide primer pairs: FBXO32 sense 5′-CTC ACA TCC CTG AGT GGC A-3′ and FBXO32 antisense 5′-AAG TAC ATC TTC TTC CAA TCC A-3′ (493 bases); RFP28 sense 5′-TGT GCC AAC GAC ATC TTC CA-3′ and RFP28 antisense 5′-GAT GAT GTT CTC CAC CAG CA-3′ (168 bases). Amplified PCR products were TA cloned using TOPO PCR II kit and transformed into Mach1 T1 phage-resistant, chemically competent E. coli (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNA was purified using QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and the nucleotides sequenced to confirm cloned DNA.

Synthetic oligonucleotide primers to the ovine nucleotide sequences were developed for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). Primer sequences were FBXO32 sense 5′-AAA GTC CTT GAA GAC CAG CAA-3′ and FBXO32 antisense 5′-AAG CAC AAA GGC AGG TCT GT-3′ (232 bp). RFP28 cloning primers were used for RT-PCR. Cloning and qPCR for ovine ribosomal protein s15 (GenBank accession no. AY949774) has been described previously (28). Specificity of the primers for the gene of interest was confirmed with agarose gel electrophoresis, melting curve analysis, and sequencing of the PCR products. cDNA samples were run in triplicate, and the qPCR was performed as described previously (28), with the standard curve method of relative quantification used to compare results (31). Ribosomal protein s15 was used as a housekeeping gene and was not different between treatment groups.

For Western blot analysis, protein was extracted from pulverized skeletal muscle (200 mg) and the concentration quantified as described previously (26). Equal amounts of protein were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reduced conditions (5% β-mercaptoethanol, vol/vol). Proteins were then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad). All Western blot membranes were blocked for 1 h in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST; vol/vol) (Bio-Rad) and 5% nonfat dried milk (NFDM; wt/vol) for 1 h at room temperature. The following primary antibodies were diluted in PBST with 5% NFDM: Thr37/46-phosphorylated 4E-BP1 (1:500), Thr202/Tyr204-phosphorylated p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK, 1:500), Ser473-phosphorylated Akt (1:750), and β-actin (1:30,000). These primary antibodies were diluted in PBST with 5% bovine serum albumin (wt/vol): p44/42 MAPK (1:500), p70 S6 kinase (p70S6k; 1:500), and Akt (1:750). The following primary antibodies were diluted in PBST with 5% NFDM and 1% BSA: Thr421/Ser424-phosphorylated p70S6k (1:250), 4E-BP1 (1:500), and the β-subunit of the insulin receptor (IR; 1:1,000). All antibodies except for β-actin (NP Biomedical, Solon, OH) and IR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were diluted in PBST with 5% NFDM and applied to membranes for 1 h at room temperature. Immunocomplexes were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham ECL Plus, Piscataway, NJ), and densitometry was performed using Scion Image software (Scion, Frederick, MD). All results were normalized to β-actin to control for loading differences, and a reference sample was analyzed on every membrane to control for differences in transfer efficiency. Phosphorylated proteins were normalized to the total amount of each protein. Antibodies were stripped from the membranes with Restore Western stripping buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Results of densitometry are presented in arbitrary units and as fold changes compared with control fetuses.

Statistical analysis.

Calculations were based on the mean values for measured parameters collected during steady-state sampling period for the tracer lysine. Statistical analysis of differences for the flux rate calculations and biochemical, hematological, hormone, and fetal weight measurements were analyzed by general linear means ANOVA [Proc GLM (29)], and treatment means were separated by the least significant difference test for multiple comparisons. Differences for in vitro tissue analysis on the skeletal muscle were determined using an ANOVA with a Tukey's test for multiple comparisons. Due to heterogeneity of variability, the data for FBXO32 and RFP28 mRNA were log transformed.

RESULTS

Maternal experimental parameters.

Maternal plasma glucose concentrations in the insulin-infused hypoglycemic ewes averaged 2.0 ± 0.2 mmol/l, ∼45% lower than the mean value of 3.7 ± 0.1 mmol/l in the control ewes during the same period. These values were not different from those of the recovery group: 3.5 ± 0.2 mmol/l prior to hypoglycemia, 1.9 ± 0.1 mmol/l during the hypoglycemic period, and 3.9 ± 0.2 mmol/l during the euglycemic recovery period.

Fetal weights.

Fetal whole body and organ weights measured at necropsy are presented in Table 2. Gestational ages were not different between the treatment groups at the time of study. Fetal body weights were 16 and 19% lower (P < 0.05) in the hypoglycemic and recovery fetuses, respectively, than in the control fetuses. The brain weights of hypoglycemic and recovery fetuses were not different from control fetuses, but brain weights in recovery fetuses were less than in hypoglycemic fetuses. The hypoglycemic and recovery mean liver weights were less than those in control fetuses. There was no difference in crown-rump length among the groups.

Table 2.

Necropsy measurements of fetal lambs

| Control | Hypoglycemic | Recovery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at necropsy | 137±1 | 139±1 | 139±2 |

| Fetal weight, kg | 4.3±0.3a | 3.6±0.1b | 3.5±0.2b |

| Brain weight, g | 46.9±1.9a,b | 50.1±0.8a | 44.9±1.25b |

| Liver weight, g | 122.3±5.8a | 103.0±6.5b | 98.2±10.2b |

| Crown-rump length, cm | 51.4±1.6 | 47.9±1.1 | 50.2±0.8 |

Values are means ± SE. Different superscripts indicate differences where P ≤ 0.05.

Fetal blood flows and lysine uptake.

Fetal studies were performed at 137 ± 1 dGA in control and hypoglycemic groups and at 138 ± 2 dGA in the recovery group. The umbilical blood and plasma flow rates per kilogram of fetal weight did not differ between treatment groups. The umbilical venous and arterial lysine concentrations were significantly higher in the hypoglycemic group compared with control fetuses. However, lysine concentrations of the recovery fetuses did not differ from the control fetuses. Net fetal (umbilical) lysine uptake rates were not different among all three groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Umbilical blood and plasma flow, plasma lysine concentrations, and umbilical lysine uptake in fetal lambs

| Control | Hypoglycemic | Recovery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Umbilical blood flow, ml·min−1·kg−1 | 204.8±15.9 | 225.3±25.2 | 229.9±10.6 |

| Umbilical plasma flow, ml·min−1·kg−1 | 135.0±11.7 | 148.3±17.1 | 160.8±10.6 |

| Umbilical vein plasma lysine, μmol/l | 91.8±11.2b | 152.8±16.0a | 64.5±9.6b |

| Arterial plasma lysine, μmol/l | 74.5±9.9b | 139.2±16.8a | 51.6±8.3b |

| Lysine uptake, μmol·min−1·kg−1 | 1.73±0.17 | 1.86±0.16 | 1.61±0.15 |

Values are means ± SE. Different superscripts indicate differences where P ≤ 0.05.

Insulin, glucose, lactate, and oxygen concentrations and umbilical uptakes.

The mean arterial plasma insulin, glucose, and lactate concentrations and blood oxygen contents for each treatment group are shown in Table 4. Mean fetal plasma insulin concentration in the hypoglycemic group was 33% lower than in the control group (P < 0.01). Similarly, mean fetal plasma glucose concentration in the hypoglycemic group was 46% lower than in the control group (P < 0.05); mean fetal plasma insulin and glucose concentrations in the control and recovery groups were not different. Mean fetal plasma lactate concentration was 33% lower in the hypoglycemic fetuses compared with control fetuses (P < 0.05), but the mean control group value was not different from that in the recovery group. The mean blood oxygen content in the hypoglycemic group was 37% greater than in the control group (P < 0.05); there was no difference between mean oxygen contents in the control and recovery groups.

Table 4.

Fetal insulin, glucose, lactate, and oxygen concentrations and net rates of fetal uptake from the placenta

| Control | Hypoglycemic | Recovery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial plasma insulin, ng/ml | 0.30±0.05a | 0.11±0.01b | 0.34±0.10a |

| Arterial plasma glucose, mmol/l | 1.06±0.06a | 0.57±0.04b | 1.21±0.06a |

| Arterial plasma lactate, mmol/l | 2.1±0.1a | 1.4±0.1b | 1.9±0.1a |

| Arterial plasma oxygen, mmol/l | 2.9±0.2a | 4.1±0.2b | 3.1±0.1a |

| Glucose uptake, μmol·min−1·kg−1 | 25.2±1.9a | 14.6±1.8b | 26.5±1.8a |

| Lactate uptake, μmol·min−1·kg−1 | 20.3±2.8 | 13.1±2.2 | 15.7±2.8 |

| Oxygen uptake, μmol·min−1·kg−1 | 394±28 | 340±25 | 371±12 |

Values are means ± SE. Different superscripts indicate differences where P ≤ 0.05.

Mean net fetal (umbilical) glucose uptake rate was significantly lower in hypoglycemic than control fetuses (P < 0.05) and was not different between control and recovery groups. Net fetal (umbilical) uptake rates of lactate were marginally lower (P = 0.054) in the hypoglycemic group than the control group and not different between control and recovery groups. Net fetal (umbilical) uptake rates of oxygen were not different among all three groups.

Fetal lysine flux rates.

The lysine fluxes between placental and fetal compartments were calculated for each treatment group, and results are shown in Table 5. The mean disposal rate for lysine (flux I) was 1.4 ± 0.1-fold greater (P < 0.05) in the hypoglycemic fetuses compared with the control group due to greater rates of lysine transfer into the placental (flux II, 1.8 ± 0.4-fold, P < 0.05) and fetal tissues (flux III, 1.3 ± 0.1-fold, P < 0.05). The rate of lysine coming from the placenta into fetal plasma (flux IV, Lysf,p) was not different between control and hypoglycemic fetuses, but the flux of lysine from the fetal tissues into the fetal plasma (fetal protein breakdown, flux V, Lysf,t) was 3.4 ± 0.6-fold greater (P < 0.05) in the hypoglycemic than in the control fetuses. No differences were found for rates of protein accretion (flux VII) or synthesis (flux VIII) using lysine tracer data between control and hypoglycemic fetuses. The rate of fetal CO2 production from lysine (flux VI) was 2.4 ± 0.4-fold higher (P < 0.05) in the hypoglycemic fetuses compared with the control fetuses.

Table 5.

Lysine flux rates estimated by combining tracer and tracee data and using plasma lysine Sa

| Flux No. | Control | Hypoglycemic | Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| I: fetal plasma lysine disposal rate | 2.33±0.25b | 3.16±0.21a | 2.06±0.14b |

| II: lysine flux into the placenta from fetal blood | 0.42±0.08b | 0.76±0.12a | 0.37±0.06b |

| III: lysine flux into fetal tissues from fetal blood | 1.91±0.2b | 2.40±0.11a | 1.69±0.15b |

| IV: lysine flux into fetal blood from placenta | 2.17±0.20 | 2.62±0.24 | 2.02±0.15 |

| V: lysine flux into fetal blood from fetal proteins | 0.16±0.1b | 0.54±0.09a | 0.04±0.1b |

| VI: CO2 produced by fetus from fetal plasma l-[U-14C]lysine | 0.16±0.02b | 0.38±0.07a | 0.07±0.01c |

| VII: lysine flux into fetal protein accretion from fetal blood | 1.59±0.16 | 1.49±0.15 | 1.58±0.16 |

| VIII: lysine flux into fetal protein synthesis | 1.75±0.19 | 2.02±0.12 | 1.62±0.15 |

Values are means ± SE. Different superscripts indicate differences where P ≤ 0.05.

Euglycemic correction following 2 wk of chronic hypoglycemia in recovery fetuses normalized all differences found for the lysine disposal rate and fetal-placental compartment flux rates II–V in the hypoglycemic fetuses. Evaluation of fetal lysine disposal rates on days 2, 3, 4, and 5 of euglycemic recovery showed no systematic trends, indicating that fetal adaptations were not progressively augmented but an immediate and persistent response during the 5 days of euglycemic recovery. In the recovery fetuses, the rate of CO2 production from fetal lysine (flux VI) was 42 ± 7% (P < 0.05) of control fetuses. No differences were found for protein accretion (flux VII) or protein synthesis (flux VIII) rates in the recovery fetuses compared with the hypoglycemic and control fetuses.

Skeletal muscle analysis.

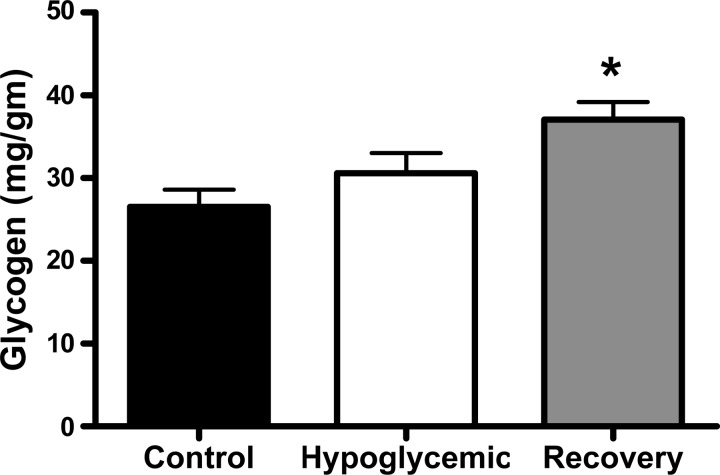

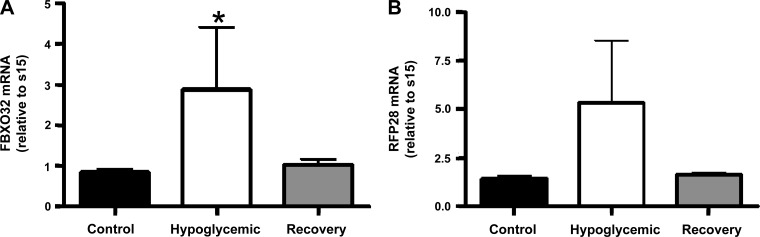

The mean glycogen content of the skeletal muscle was not different between the hypoglycemic and control fetuses but was significantly increased in the recovery fetuses compared with E fetuses (P < 0.01; Fig. 2). We also measured the mRNA content of two muscle-specific ubiquitin ligases. There was a higher amount of FBXO32 mRNA in hypoglycemic fetuses compared with control fetuses (P < 0.05); a similar trend was found for RFP28 mRNA (P = 0.08). The FBXO32 and RFP28 mRNA content in recovery fetuses was close to the values in the control fetuses, although they were not different from either control or hypoglycemic fetuses (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Skeletal muscle glycogen content. The average skeletal muscle glycogen content (mg glycogen/g tissue) was determined for each treatment group indicated on the x-axis. *Significantly greater glycogen content in the recovery fetuses compared with euglycemic control fetuses; P < 0.01 by ANOVA.

Fig. 3.

Skeletal muscle ovine F-box-only protein 32 (FBXO32) and ring finger protein 28 (RFP28) mRNA concentrations. Mean mRNA concentrations for FBXO32 (A) and RFP28 (B) were determined by quantitative real-time PCR in the skeletal muscle and normalized to ribosomal protein s15. Treatment groups are indicated on the x-axis of the bar graph, with means ± SE shown. FBXO32 mRNA was significantly elevated in hypoglycemic fetuses compared with control fetuses; *P < 0.05 by ANOVA.

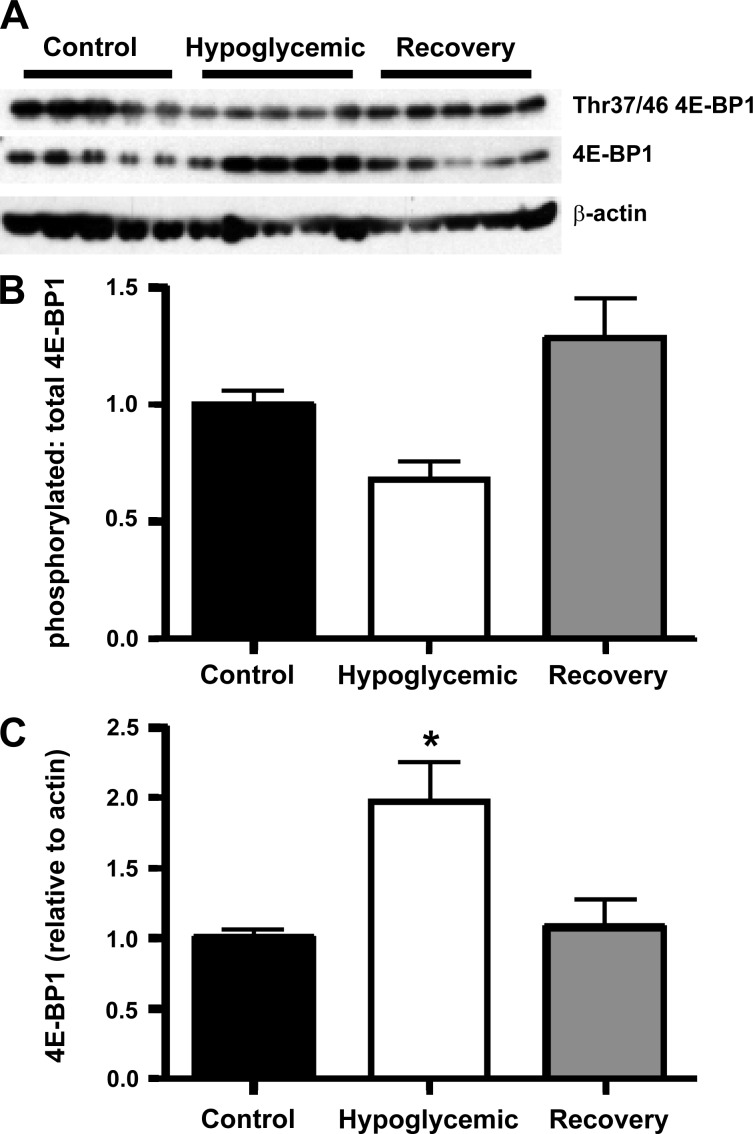

We also examined the insulin-signaling pathways that regulate protein synthesis. The proportion of phosphorylated 4E-BP1 (Thr37/46) to total 4E-BP1 was not different in hypoglycemic or recovery fetuses compared with control fetuses, although hypoglycemic fetuses tended to have a lower ratio than control fetuses (P = 0.09; Fig. 4). There was a significantly lower phosphorylated/total 4E-BP1 ratio in recovery compared with hypoglycemic fetuses (P < 0.005). The total amount of 4E-BP1 relative to β-actin was higher in the skeletal muscle of the hypoglycemic fetuses compared with the control and recovery fetuses (P < 0.05). No differences were found among the three groups for skeletal muscle content of IR (control 1.00 ± 0.09, hypoglycemic 0.89 ± 0.09, recovery 1.13 ± 0.18), Akt (control 1.00 ± 0.14, hypoglycemic 1.08 ± 0.29, recovery 1.19 ± 0.4), p44/42 MAPK (control 1.00 ± 0.12, hypoglycemic 0.99 ± 0.18, recovery 0.62 ± 0.10), or p70S6k (control 1.00 ± 0.11, hypoglycemic 0.81 ± 0.13, recovery 0.72 ± 0.13). Similarly, no differences were found among the three groups for the ratio of Ser473-phosphorylated Akt (control 1.00 ± 0.16, hypoglycemic 1.79 ± 0.47, recovery 1.69 ± 0.32), Thr202/Tyr204-phosphorylated p44/42 MAPK (control 1.00 ± 0.21, hypoglycemic 1.59 ± 0.24, recovery 1.51 ± 0.22), or Thr421/Ser424-phosphorylated p70S6k (control 1.00 ± 0.20, hypoglycemic 1.47 ± 0.26, recovery 0.87 ± 0.23) to the total amount of the respective protein present.

Fig. 4.

Total and phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1). A: a representative Western blot is shown for Thr37/46-phosphorylated 4E-BP1, total 4E-BP1, and β-actin. B: the bar graph for the mean ± SE densitometry measurements of Thr37/46 4E-BP1 relative to total 4E-BP1 identified no significant difference between treatment groups (x-axis) compared with controls. However, there is a significantly lower ratio in hypoglycemic fetuses compared with recovery fetuses (P < 0.005) and a trend toward a lower ratio compared with control fetuses (P = 0.009). C: the mean ± SE densitometry measurement for 4E-BP1 relative to β-actin in each treatment group is presented. There is significantly increased 4E-BP1 in hypoglycemic fetuses compared with control and recovery fetuses (*P < 0.01) determined by ANOVA.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we determined the rate and distribution of lysine disposal into fetal compartments in fetal sheep during chronic hypoglycemia and following euglycemic recovery and compared results with normal, age-matched euglycemic control fetuses. Our goal was to define the amino acid/protein metabolic adaptations to chronic glucose deficiency and to determine whether reintroduction of glucose could normalize amino acid and protein metabolism. In response to 2 wk of sustained glucose deficiency, the mean fetal plasma lysine concentration was 1.9-fold greater in hypoglycemic compared with control fetuses, and there was a higher rate of lysine disposal into the placental and fetal tissue compartments without a change in the rate of net fetal (umbilical) lysine uptake. The oxidative metabolism of lysine (the rate of CO2 production from lysine decarboxylation) was 2.4-fold greater in hypoglycemic fetuses. Although there was no difference in fetal tissue protein synthesis or accretion, there was an increase in fetal tissue protein breakdown (the flux of lysine from fetal tissues into the plasma). Euglycemic recovery normalized all fluxes and even reduced the rate of lysine decarboxylation compared with control fetuses (P < 0.05), indicating that lysine oxidation was overcorrected following normalization of plasma glucose concentrations. These changes in protein breakdown in the hypoglycemic fetuses coincided with greater expression levels of muscle-specific ubiquitin ligases. The maintained protein synthesis occurred despite an increase in total 4E-BP1, perhaps related to otherwise maintained phosphorylation ratios in the insulin-signaling pathways that were measured. Together, our results for lysine indicate that chronic hypoglycemia may decrease fetal growth over time by increasing ubiquitin ligase-mediated protein degradation rates. Of major importance, the chronic metabolic adaptations of lysine and protein metabolism to glucose deficiency were remedial, indicating that after at least 2 wk of glucose deprivation, the fetal sheep can shift back to normal glucose utilization. However, lysine oxidation rates were reduced compared with normal fetuses. Coupled with normalization of the rate of protein breakdown, this might allow for resumption of normal to marginally greater rates over time of fetal growth once the hypoglycemia is corrected.

Similar to the current study, previous measurements in our laboratory of leucine metabolism in fetal sheep that were chronically hypoglycemic for 8 wk revealed increased rates of leucine release from protein breakdown. In contrast, 8 wk of hypoglycemia resulted in reduced rates of overall protein accretion. Clearly, a reduced rate of protein accretion as a response to chronic hypoglycemia is an adaptation that progressively increases over time. Similar to our current study, however, 8 wk of chronic hypoglycemia produced no difference in the rate of protein synthesis (6). A major and novel finding of the present study is that reintroduction of glucose following a chronic, 2 wk restriction in glucose supply leads to resumption of normal amino acid and protein metabolism.

Following 2 wk of chronic hypoglycemia the rate of protein breakdown is increased, but protein accretion is maintained. This must be due to a nonsignificant, 15% increase in the mean rates of protein synthesis in the hypoglycemic fetuses. Analysis of fetal skeletal muscle corroborated our in vivo findings, except for our 4E-BP1 results. The total amount of 4E-BP1 increased in the hypoglycemic fetuses and then returned to normal following restoration of a normal fetal glucose supply. 4E-BP1 is a binding protein that normally binds to eIF4E and acts to inhibit translation initiation and protein synthesis. In the acute setting, 4E-BP1 is regulated by phosphorylation events that act to inhibit its eIF4E-binding function, thereby allowing for increased translation initiation (23). In the hypoglycemic fetuses, the proportion of phosphorylated 4E-BP1 compared with the total amount was not different. This may be one reason why protein synthesis is maintained despite increased amounts of the inhibitory 4E-BP1. Additionally, p70S6k and its phosphorylation were maintained, as were other proteins in the insulin-signaling pathways that regulate protein synthesis; however, the variation in these measurements increased during hypoglycemia, which might have limited our ability to identify the small but significant increases in insulin action. As for the increased release of amino acids from fetal tissues, FBXO32 and RFP28, also known as MAFbx-1 and MuRF1, have been identified as two muscle-specific ubiquitin ligases that mediate protein degradation due to a variety of experimental conditions (3). They appear to be part of a common final pathway that mediates skeletal muscle atrophy (3). Our results show that chronic fetal glucose deprivation increases these ligases, which in turn allows for greater amino acid release from fetal tissue into fetal plasma and for increased rates of lysine oxidation, as observed in hypoglycemic fetuses. Again, this is a reversible process since the expression of these ligases returns to normal following restoration of a normal glucose supply. To our knowledge, this is the first experimental demonstration of these ligases regulating fetal protein breakdown in situations of nutrient deprivation.

It is instructive to compare our results following 2 wk of hypoglycemia with those obtained using leucine kinetics to measure amino acid metabolism following 8 wk of hypoglycemia. After 8 wk there was not an increase in leucine oxidation, although we found a significant increase in lysine oxidation following 2 wk of hypoglycemia. One explanation for this discrepancy is that the chronically hypoglycemic fetus develops a progressive increase in fetal glucose production, presumably due to gluconeogenesis (8, 22, 26). This endogenously produced glucose might progressively replace amino acid oxidation during chronic selective fetal hypoglycemia such that amino acid oxidation is increased toward the beginning of the hypoglycemia but then decreases somewhere between 2 and 8 wk. However, in very acute maternal insulin-induced fetal hypoglycemia (3 h), no increase in leucine oxidation was demonstrated (21). Therefore, the capacity of the fetus to oxidize amino acids in place of glucose during hypoglycemia appears to require more than 3 h to develop and then is downregulated somewhere between 2 and 8 wk. This time course also is consistent with leucine oxidation rates in a model of intrauterine growth restriction following chronic (>8 wk) placental insufficiency, which are normal (25) and have increased leucine oxidation rates obtained following 5 days of maternal fasting (12). An additional confounding variable includes the gestational age of onset of the nutrient restriction, which may also influence the fetal response. Of course, differences between fetal leucine and lysine utilization patterns cannot be excluded. These important differences between fetal leucine and lysine metabolism include the proportion of the disposal rate that represents fetal protein accretion and amino acid oxidation (2). Normally, most of the lysine that enters the fetal tissues from the fetal plasma is committed to protein accretion, with only a small percentage destined for oxidation and energy production (6). For leucine, a much higher percentage of the flux into fetal tissues is oxidized (∼35%) (25). Further studies would be required to determine whether these differences are important and to better define the time course of amino acid oxidation as a substitute for glucose.

Another interesting comparison is the difference between protein accretion, synthesis, and breakdown over the various lengths of fetal hypoglycemia. Acute, 3-h, fetal hypoglycemia significantly decreased fetal protein accretion due to decreased protein synthesis and did not change rates of fetal protein breakdown (21). By 2 wk of hypoglycemia we found increased fetal protein breakdown with normal protein accretion and synthesis. At 8 wk of hypoglycemia there was a significant decrease in protein accretion due to a persistent increase in the rate of protein breakdown; rates of protein synthesis were not different. An early adaptation to hypoglycemia is decreased protein accretion due to decreased protein synthesis and not to increased protein breakdown. This is followed by a return of protein synthetic rates to normal and increased protein breakdown that eventually results in persistently lower rates of protein accretion by 8 wk. The implications for improvement of fetal growth during fetal growth restriction and chronic nutrient restriction are that interventions designed to reduce protein breakdown might be more effective than those designed to increase rates of protein synthesis. Studies are currently underway to evaluate these potential interventions and their effects on fetal protein breakdown.

Although we did not measure glucose metabolism in this study, previously we used this model to investigate glucose metabolism with glucose tracers following 2 wk of hypoglycemia. The data demonstrated maintained fetal glucose oxidation rates relative to a significant reduction in fetal insulin and glucose concentrations (8). Furthermore, glucose transporter concentrations (GLUT1 and -4) in insulin-responsive tissues are unaffected by chronic glucose deprivation, indicating that avidity for glucose uptake is not the reason for maintained glucose oxidation (7). Consistent with this, we found skeletal muscle glycogen (1 product of glucose utilization) to be maintained in the hypoglycemic fetuses, similar to previously documented glycogen contents in the livers of these hypoglycemic fetuses (26). This suggests maintained or even increased insulin and/or glucose sensitivity in the hypoglycemic fetuses, at least for the pathways regulating fetal glucose utilization, oxidation, and glycogen content. Although we did not test this directly by measuring fetal glucose utilization rates during a hyperinsulinemic euglycemic and/or hyperglycemic euinsulinemic clamp, we did measure the relative phosphorylation of the proximal insulin-signaling proteins Akt and MAPK and found no difference in baseline phosphorylation in the fetuses. Maintained phosphorylation relative to the total amounts of these proteins despite a significant reduction in fetal insulin concentrations cannot be explained by an increase in skeletal muscle insulin receptor because this was likewise unchanged. Two phenomena in the recovery group suggest that there may be a residual increase in insulin and/or glucose sensitivity. One is the rebound increase in fetal skeletal muscle glycogen. The other is that a significant reduction in lysine oxidation in this group compared with control fetuses might indicate increased glucose oxidation in the recovery fetuses, thus sparing lysine for nonoxidative pathways. A more detailed explanation of the mechanisms responsible for maintained or increased insulin and/or glucose sensitivity requires further studies, including measuring glucose utilization rates during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic and hyperglycemic euinsulinemic clamps followed by tissue collection under these experimental conditions.

In our previous study with euglycemic correction following 2 wk of persistent fetal hypoglycemia, we found that 5 days of euglycemic recovery resulted in a normalization of fetal weights (13). A primary reason for repeating this treatment design was to understand potential effects of amino acid metabolism that might be responsible for the catchup growth observed in the previous study. In the current data set, however, no correction in fetal weight was observed (Table 2), although all other in vivo results between the two cohorts of fetuses were similar. We did not measure fetal protein synthesis or net protein balance in the first study. In the present study, during the recovery period there was evidence for conservation of lysine into fetal protein (reduced release of lysine from protein and reduced oxidation of lysine), but protein synthesis and accretion from lysine were not different from controls, perhaps due to the unexplained lower fetal plasma lysine concentration. Thus, although this new data provides insight into the mechanisms involved in regulation of protein metabolism in response to nutrient deprivation and glucose replacement, it is possible that undetermined differences in study design and animal variability contributed to differences in fetal weight gain between the two studies. Clearly, the interaction between glucose and amino acid supply and the regulation of fetal protein metabolism and weight change require more thorough investigation, particularly if therapy of intrauterine growth restriction should become a target for future experimental trials.

In conclusion, we have shown that fetal lysine oxidation and fetal protein breakdown increase as metabolic adaptations to 2 wk of fetal hypoglycemia. These results are consistent with data from fetuses made hypoglycemic for 8 wk (6) but add to our knowledge by indicating that these changes in amino acid and protein metabolism are progressive over time and are reversible, at least after the 2 wk of hypoglycemia that we studied, upon restoration of normal fetal glucose concentrations. Future studies are clearly needed to better understand the molecular events responsible for changes in glucose, insulin, and amino acid metabolism in this model, such as measurement of glucose and/or amino acid metabolism under various clamp conditions with varying levels of glucose, amino acids, and insulin.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health {RO1-HD-42815 [W. W. Hay, Jr., principal investigator (PI)], KO1-DK-067393 (S. W. Limesand, PI), and Institutional Training Grant T32-HD-07186 (W. W. Hay, Jr., PI; P. J. Rozance, trainee)}, The Children's Hospital Research Institute, Research Scholar Awards (P. J. Rozance, PI; L. D. Brown, PI), and Pilot Project Awards from the Colorado Clinical Nutrition Unit (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: 2-P30-DK-048520-11, J. Hill, PI; P. J. Rozance and L. D. Brown, awardees).

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to C. Teng, K. Trembler, and A. Cheung for their valuable technical contributions.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry JS, Davidsen ML, Limesand SW, Galan HL, Friedman JE, Regnault TR, Hay WW Jr. Developmental changes in ovine myocardial glucose transporters and insulin signaling following hyperthermia-induced intrauterine fetal growth restriction. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 231: 566–575, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battaglia FC, Meschia G. An Introduction to Fetal Physiology. London: Academic, 1986.

- 3.Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, Lai VK, Nunez L, Clarke BA, Poueymirou WT, Panaro FJ, Na E, Dharmarajan K, Pan ZQ, Valenzuela DM, DeChiara TM, Stitt TN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 294: 1704–1708, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown LD, Rozance PJ, Barry JS, Friedman JE, Hay WW Jr. Insulin is required for amino acid stimulation of dual pathways for translational control in skeletal muscle in the late-gestation ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E56–E63, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carver TD, Anderson SM, Aldoretta PW, Hay WW Jr. Effect of low-level basal plus marked “pulsatile” hyperglycemia on insulin secretion in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 271: E865–E871, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carver TD, Quick AA, Teng CC, Pike AW, Fennessey PV, Hay WW Jr. Leucine metabolism in chronically hypoglycemic hypoinsulinemic growth-restricted fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 272: E107–E117, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das UG, Schroeder RE, Hay WW Jr, Devaskar SU. Time-dependent and tissue-specific effects of circulating glucose on fetal ovine glucose transporters. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 276: R809–R817, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiGiacomo JE, Hay WW Jr. Fetal glucose metabolism and oxygen consumption during sustained hypoglycemia. Metabolism 39: 193–202, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hay WW, Sparks JW, Wilkening RB, Battaglia FC, Meschia G. Partition of maternal glucose production between conceptus and maternal tissues in sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 245: E347–E350, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hay WW, Sparks JW, Wilkening RB, Battaglia FC, Meschia G. Fetal glucose uptake and utilization as functions of maternal glucose concentration. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 246: E237–E242, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Gilbert A, Gomes M, Baracos V, Bailey J, Price SR, Mitch WE, Goldberg AL. Multiple types of skeletal muscle atrophy involve a common program of changes in gene expression. FASEB J 18: 39–51, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liechty EA, Boyle DW, Moorehead H, Liu YM, Denne SC. Effect of hyperinsulinemia on ovine fetal leucine kinetics during prolonged maternal fasting. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 263: E696–E702, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Limesand SW, Hay WW Jr. Adaptation of ovine fetal pancreatic insulin secretion to chronic hypoglycaemia and euglycaemic correction. J Physiol 547: 95–105, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Limesand SW, Regnault TR, Hay WW Jr. Characterization of glucose transporter 8 (GLUT8) in the ovine placenta of normal and growth restricted fetuses. Placenta 25: 70–77, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Smith D, Hay Jr WW. Increased insulin sensitivity and maintenance of glucose utilization rates in fetal sheep with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1716–E1725, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Zerbe GO, Hutton JC, Hay WW Jr. Attenuated insulin release and storage in fetal sheep pancreatic islets with intrauterine growth restriction. Endocrinology 147: 1488–1497, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loy GL, Quick AN Jr, Battaglia FC, Meschia G, Fennessey PV. Measurement of leucine and alpha-ketoisocaproic acid fluxes in the fetal/placental unit. J Chromatogr 562: 169–174, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loy GL, Quick AN Jr, Hay WW Jr, Meschia G, Battaglia FC, Fennessey PV. Fetoplacental deamination and decarboxylation of leucine. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 259: E492–E497, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meier PR, Peterson RG, Bonds DR, Meschia G, Battaglia FC. Rates of protein synthesis and turnover in fetal life. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 240: E320–E324, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meschia G, Cotter JR, Breathnach CS, Barron DH. Simultaneous measurement of uterine and umbilical blood flows and oxygen uptake. Q J Exp Physiol 52: 1–8, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milley JR Ovine fetal protein metabolism during decreased glucose delivery. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 265: E525–E531, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narkewicz MR, Carver TD, Hay WW Jr. Induction of cytosolic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in the ovine fetal liver by chronic fetal hypoglycemia and hypoinsulinemia. Pediatr Res 33: 493–496, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pause A, Belsham GJ, Gingras AC, Donze O, Lin TA, Lawrence JC Jr, Sonenberg N. Insulin-dependent stimulation of protein synthesis by phosphorylation of a regulator of 5′-cap function. Nature 371: 762–767, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Regnault TR, Orbus RJ, Battaglia FC, Wilkening RB, Anthony RV. Altered arterial concentrations of placental hormones during maximal placental growth in a model of placental insufficiency. J Endocrinol 162: 433–442, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross JC, Fennessey PV, Wilkening RB, Battaglia FC, Meschia G. Placental transport and fetal utilization of leucine in a model of fetal growth retardation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 270: E491–E503, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rozance PJ, Limesand SW, Barry JS, Brown LD, Thorn SR, LoTurco D, Regnault TR, Friedman JE, Hay WW Jr. Chronic late-gestation hypoglycemia upregulates hepatic PEPCK associated with increased PGC1α mRNA and phosphorylated CREB in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 294: E365–E370, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozance PJ, Limesand SW, Hay WW Jr. Decreased nutrient-stimulated insulin secretion in chronically hypoglycemic late-gestation fetal sheep is due to an intrinsic islet defect. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E404–E411, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rozance PJ, Limesand SW, Zerbe GO, Hay WW Jr. Chronic fetal hypoglycemia inhibits the later steps of stimulus-secretion coupling in pancreatic β-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E1256–E1264, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS Institute. SAS/STAT User's Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 1999.

- 30.van Veen LC, Teng C, Hay WW Jr, Meschia G, Battaglia FC. Leucine disposal and oxidation rates in the fetal lamb. Metabolism 36: 48–53, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong ML, Medrano JF. Real-time PCR for mRNA quantitation. Biotechniques 39: 75–85, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]