Abstract

Blood pressure (BP) is more salt sensitive in men than in premenopausal women. In Dahl salt-sensitive rats (DS), high-salt (HS) diet increases BP more in males than females. In contrast to the systemic renin-angiotensin system, which is suppressed in response to HS in male DS, intrarenal angiotensinogen expression is increased, and intrarenal levels of ANG II are not suppressed. In this study, the hypothesis was tested that there is a sexual dimorphism in HS-induced upregulation of intrarenal angiotensinogen mediated by testosterone that also causes increases in BP and renal injury. On a low-salt (LS) diet, male DS had higher levels of intrarenal angiotensinogen mRNA than females. HS diet for 4 wk increased renal cortical angiotensinogen mRNA and protein only in male DS, which was prevented by castration. Ovariectomy of female DS had no effect on intrarenal angiotensinogen expression on either diet. Radiotelemetric BP was similar between males and castrated rats on LS diet. HS diet for 4 wk caused a progressive increase in BP, protein and albumin excretion, and glomerular sclerosis in male DS rats, which were attenuated by castration. Testosterone replacement in castrated DS rats increased BP, renal injury, and upregulation of renal angiotensinogen associated with HS diet. Testosterone contributes to the development of hypertension and renal injury in male DS rats on HS diet possibly through upregulation of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system.

Keywords: androgens, hypertension, renal injury, glomerular sclerosis, angiotensinogen

salt-sensitive hypertension is defined as an increase in blood pressure (BP) with high salt (HS) intake or a decrease in BP caused by salt restriction (32). Salt-sensitive hypertension in humans is associated with higher morbidity and mortality due to cardiovascular disease than hypertension of other etiologies (21, 31). The Dahl salt-sensitive rat (DS) exhibits a genetic form of hypertension that develops when animals are fed a HS diet (5). When male and female DS rats are fed HS diet, males become more hypertensive than females (4, 9). However, the mechanisms responsible for mediating the sex difference in BP on HS in DS rats are unknown.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is a major factor in long-term regulation of BP. It is well accepted that DS rats on HS diet exhibit a suppressed systemic RAS (2, 25). However, in male DS rats on HS, Kobori et al. (18) showed that intrarenal angiotensinogen expression is increased and levels of ANG II are not suppressed. These data support the idea that a locally active intrarenal RAS may play a major role in mediating salt-sensitive hypertension. Supporting this concept are data showing that administration of blockers of the RAS, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R) antagonists, decreases BP and improves hypertensive target organ injury in male DS on HS diet (22, 30). Whether attenuation of the intrarenal RAS plays a role in the lower BP found in female DS on HS has not been studied, however.

Sex steroids are able to modulate the intrarenal RAS in normotensive and hypertensive rat models (34). Estradiol has been shown to downregulate AT1R and ACE expression in the kidney, adrenal, vasculature, and brain in female normotensive rats (6). In contrast, testosterone was previously shown to upregulate angiotensinogen in kidneys of male spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) (3, 7) and mediates hypertension in several rat models, such as the SHR (26), Sabra rats (12), and the renal wrap model of hypertension (11). Whether testosterone is implicated in the pathogenesis of salt-induced hypertension and increases in intrarenal levels of angiotensinogen has not been studied previously.

The present study addressed the role of sex steroids in mediating changes in angiotensinogen and other components of the intrarenal RAS in response to HS diet in DS rats. The hypothesis tested was that, in contrast to the well-accepted suppression of the systemic RAS with HS, male DS on HS exhibit a testosterone-mediated activation of the intrarenal RAS, primarily because of upregulation of intrarenal angiotensinogen expression that could account in part for the sexual dimorphism in the pressor response to HS. Furthermore, we hypothesized that testosterone-mediated upregulation of intrarenal angiotensinogen is associated with hypertension and renal injury in male DS on HS diet.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

DS rats (Rapp strain) were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). The rats were housed in temperature-controlled rooms with a constant light-dark cycle (12:12 h) and free access to water and food. The protocols complied with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the National Institutes of Health and were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Protocol A: Measurement of components of intrarenal RAS in DS rats.

Male, female, ovariectomized female (OVX), and castrated male (CAS) DS rats (n = 6/group) were used. Gonadectomy was performed at 8 wk of age by the vendor. Upon arrival, the rats were maintained on a low-salt (LS) phytoestrogen-free diet (AIN 76, 0.28% NaCl) until 17 wk of age. Next male, female, OVX, and CAS rats were selected at random to receive HS diet (AIN 76 + 8% NaCl) for 4 wk or LS diet throughout the study. At the end of the experimental protocol, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, and the left kidney was removed, separated into cortex and medulla, and frozen in liquid nitrogen for mRNA expression measurement. The right kidney was perfused with 2% heparin in 0.9% NaCl for Western blot analysis.

Protocol B: Measurement of BP and renal injury in intact and CAS male DS rats.

Castration was performed at 8 wk of age by the vendor. Intact male and CAS rats (n = 11/group) were maintained on a LS diet until 15 wk of age when radiotelemetry catheters (TA11PA-C40 radiotelemetry transmitter; RLA-3000 receiver; Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) were implanted in the abdominal aorta below the renal arteries using isoflurane anesthesia, as we previously described (29). At 17 wk of age, mean arterial pressure was monitored continuously for 5 days in rats on LS diet. After the control period, the rats were challenged with HS diet (AIN 76 + 8% NaCl) for 4 wk. BP measurements were obtained during a 10-s sampling period (500 Hz), recorded, and averaged every 10 min for 24 h/day. To analyze the data, BP measurements from 8:00 A.M. to 11:00 A.M. were excluded since laboratory animal personnel were allowed to access the room during this time for routine maintenance and cleaning.

At the end of the LS period and then after 4 wk of HS diet, urine was collected for 24 h in metabolic cages (Nalgene, Rochester, NY), for determination of total protein and albumin excretion. At the end of the experimental protocol, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane, a cathether was placed in the abdominal aorta for blood collection in heparinized tubes for determination of testosterone and estradiol, and kidneys were perfused free of blood with saline containing 2% heparin and stored in 10% buffered formalin for morphological analysis.

Protocol C: Testosterone replacement in CAS DS rats.

To determine the specific role of testosterone in mediating the changes in intrarenal angiotensinogen expression, BP, and renal injury in response to HS diet, CAS rats at 8 wk of age (n = 4/group) were implanted subcutaneously in their backs with testosterone propionate-filled Silastic pellets (5 mm in length) under isoflurane anesthesia and compared with intact males or CAS DS rats (n = 4/group). The pellets were changed every 4 wk. As in protocol B, at 15 wk of age, the rats were implanted with radiotelemetry probes for continuous BP measurement. At 17 wk of age, the rats were challenged with HS diet for 4 wk. At the end of the 4-wk period on HS diet, the rats were placed in metabolic cages for determination of protein excretion in the urine, blood was collected for determination of plasma testosterone, and kidneys were perfused with 2% heparin in saline. One kidney was stored in 10% buffered formalin for morphological analysis, and the other was used for determination of intrarenal levels of angiotensinogen mRNA and protein expression.

Measurement of mRNA expression by real-time PCR.

mRNA expression levels of the components of the RAS (angiotensinogen, renin, ACE, and AT1aR) were measured by real-time RT-PCR, as we have previously described (33).

Measurement of urinary protein and albumin excretion.

Total urinary protein excretion was measured by the method of Bradford (1), using a commercially available reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and BSA was used as standard. Rat albumin was measured by enzyme-linked immunoassay using a sheep polyclonal antibody raised against rat albumin, as we previously described (29).

Assessment of glomerular sclerosis.

Kidney sections from intact, CAS, and CAS replaced with testosterone DS rats on HS diet were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm sections. The sections were stained with methenamine silver and periodic acid-Schiff reagent and examined by a pathologist (Racusen) unaware of the identity of the groups. Three hundred glomeruli from each kidney were examined, and each was graded for injury as follows: <25% of the glomerulus damaged; 25–50% damaged; 51–75% damaged, and >75% damaged. The data from all rats in each group were averaged and expressed as a percentage of glomeruli from each kidney exhibiting the four levels of injury, as we previously published (8).

Plasma testosterone and estradiol.

Plasma testosterone and estradiol were measured using commercially available radioimmunoassay kits as we previously described (8).

Measurement of kidney angiotensinogen protein expression by Western blot.

Kidney tissue was homogenized in 8 vol/wt of RIPA buffer with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Kidney homogenates (25 μg protein) were separated electrophoretically, and Western blots were performed, as we previously described (33), using a sheep polyclonal antibody raised against purified rat angiotensinogen (1:50,000 dilution) (15).

Statistical analyses.

All results are expressed as means ± SE. Multiple groups were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance followed by Student-Newman-Keul's comparisons. Time series BP data were analyzed by repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance followed by Student-Newman-Keul's comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SigmaStat software package version 3.1 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

Effect of sex steroids and salt diet on renal cortical and medullary expression of angiotensinogen mRNA and protein (protocol A).

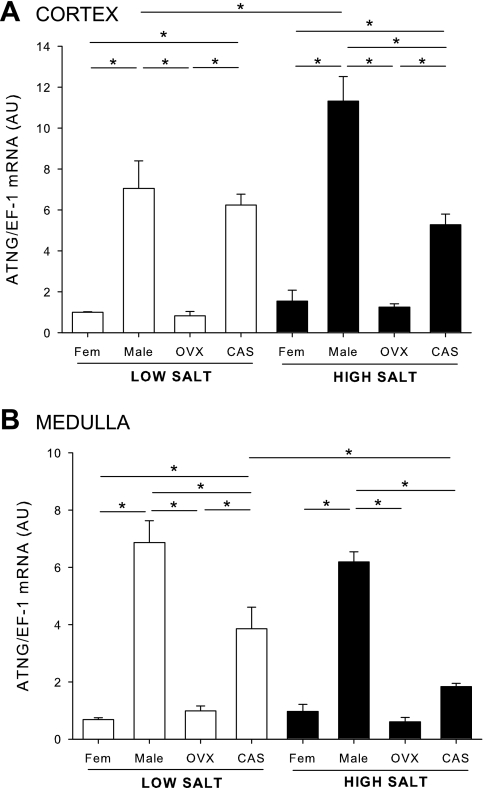

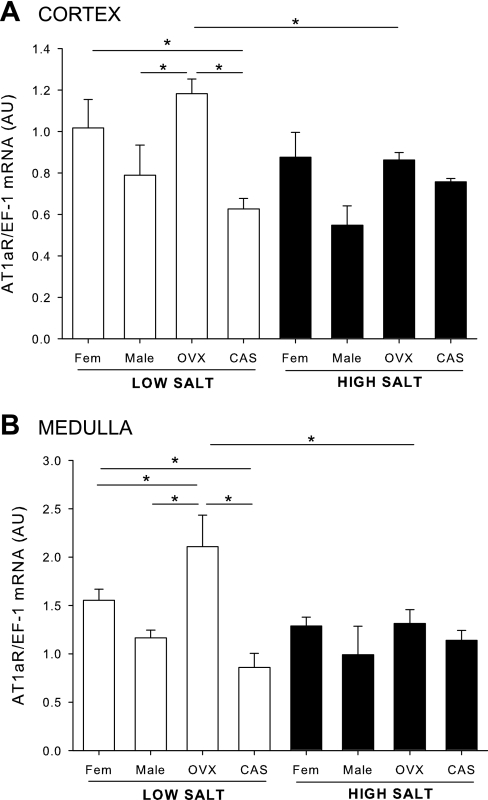

As shown in Fig. 1A, cortical angiotensinogen mRNA expression on LS diet was significantly higher in male DS than females, and gonadectomy did not alter the levels. HS diet elicited an additional significant increase in cortical angiotensinogen mRNA only in male DS, and castration of male DS blunted the upregulation. In contrast, ovariectomy in females did not alter the levels of angiotensinogen mRNA in kidney cortex on either HS or LS. As shown in Fig. 1B, medullary angiotensinogen mRNA was also higher in medulla of male DS than females and was reduced significantly by castration. In contrast to cortical expression, HS diet had no effect on angiotensinogen levels in the medulla of males, but HS caused a downregulation in angiotensinogen expression in CAS rats.

Fig. 1.

Renal angiotensinogen mRNA expression in male, female, castrated (CAS), and ovariectomized (OVX) Dahl salt-sensitive (DS) rats on low (LS)- and high (HS)-salt diet. Animals were maintained in LS diet and at 17 wk of age were randomly assigned to receive LS or HS diet for a 4-wk period. At the end of the experimental protocol, kidneys were removed and separated into cortex (A) and medulla (B), and angiotensinogen (ATNG) mRNA levels were quantified by real-time RT-PCR. *P < 0.05.

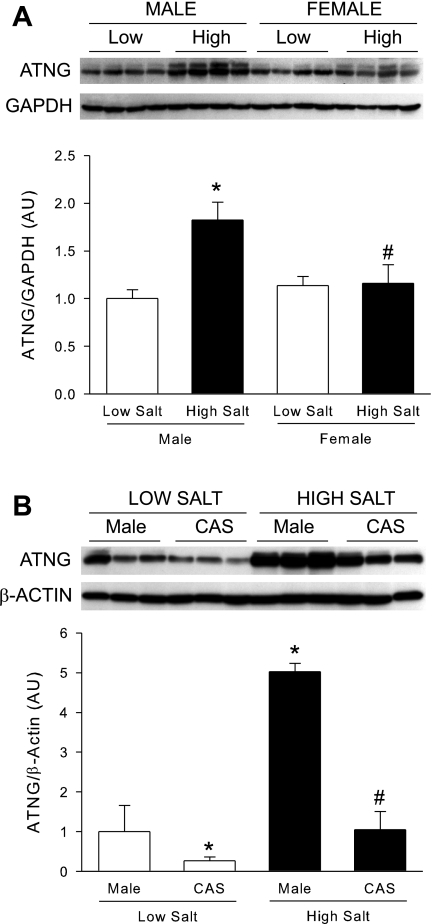

As shown in Fig. 2A, renal angiotensinogen protein expression was similar between intact male and female DS on LS. HS significantly increased renal angiotensinogen protein expression in male DS but not females. Castration significantly blunted the increases in renal angiotensinogen protein expression in DS males on HS diet, as shown in Fig. 2B.

Fig. 2.

Renal angiotensinogen protein expression in male, female, and CAS DS rats on LS and HS diet. Male and female (A) or male and CAS (B) DS rats were maintained on a LS diet and at 17 wk of age were randomly assigned to receive LS or HS diet for a 4-wk period. At the end of the experimental protocol, kidneys were removed and angiotensinogen protein levels were quantified by Western blot. P < 0.05 vs. intact male LS diet (*) and vs. male HS diet (#).

Effects of sex steroids and salt diet on renal cortical and medullary renin mRNA expression (protocol A).

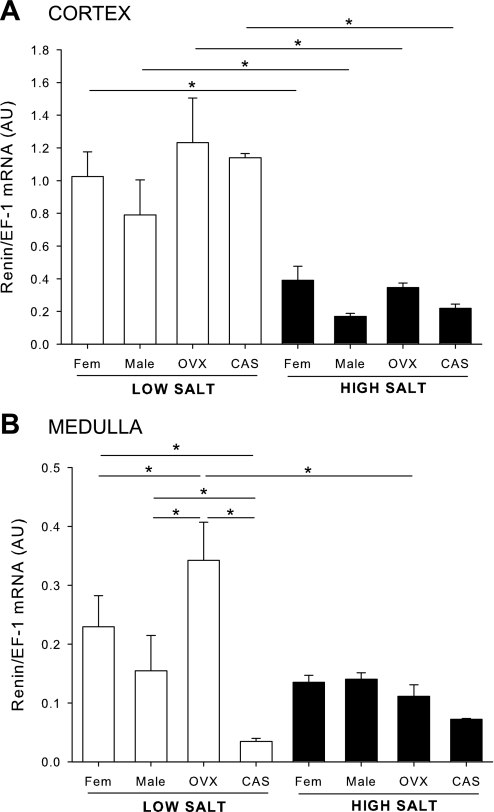

On LS diet, renin mRNA expression in the cortex was similar between male, female, OVX, and CAS rats (Fig. 3A). HS caused a significant reduction in renal cortical renin to similar levels in all groups. In the medulla, renin mRNA expression was not different between males and females but was higher in OVX and lower in CAS rats on LS (Fig. 3B). HS caused a reduction in medullary renin mRNA expression in OVX rats.

Fig. 3.

Renal renin mRNA expression in male, female, CAS, and OVX DS rats on LS and HS diet. Animals were maintained on LS diet and at 17 wk of age were randomly assigned to receive LS or HS diet for a 4-wk period. At the end of the experimental protocol, kidneys were removed and separated into cortex (A) and medulla (B), and renin mRNA levels were quantified by real-time RT-PCR. *P < 0.05.

Effects of sex steroids and salt diet on renal cortical and medullary ACE mRNA expression (protocol A).

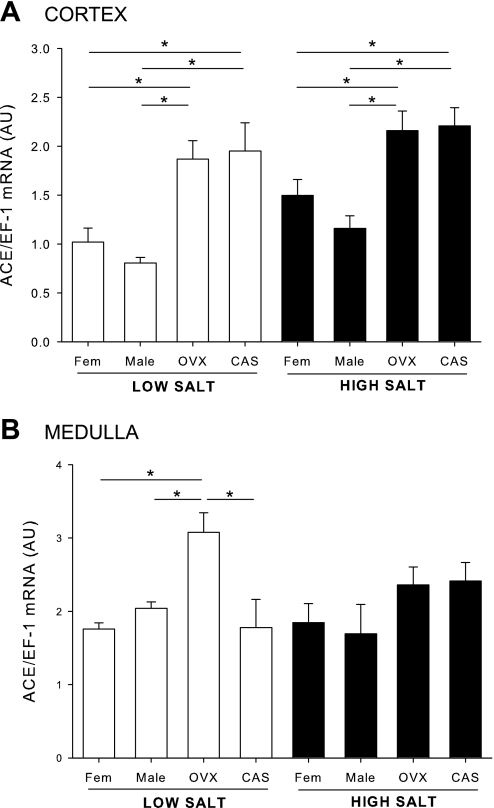

In the renal cortex, there was no sex difference in ACE mRNA expression in intact rats on LS diet. However, both CAS and OVX exhibited greater expression of ACE mRNA than intact rats. On HS, there was no change in cortical ACE mRNA in any of the groups. In the medulla, there was no sex difference in ACE mRNA, but OVX caused an increase in ACE. On HS, there was no difference in ACE expression among the groups (Fig. 4, A and B).

Fig. 4.

Renal angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) mRNA expression in male, female, CAS, and OVX DS rats on LS and HS diet. Animals were maintained in LS diet and at 17 wk of age were randomly assigned to receive LS or HS diet for a 4-wk period. At the end of the experimental protocol, kidneys were removed and separated into cortex (A) and medulla (B), and ACE mRNA levels were quantified by real-time RT-PCR. *P < 0.05.

Effects of sex steroids and salt diet on renal cortical and medullary AT1aR mRNA expression (protocol A).

On LS diet, there was no sex difference in cortical AT1aR mRNA expression in intact DS rats, nor was AT1aR mRNA expression affected by gonadectomy. HS diet did not affect the cortical expression of AT1aR expression in male, female, or CAS rats. However, HS downregulated AT1aR mRNA expression in cortex of OVX females so that the levels of AT1aR were similar in cortex of all rats on HS. In the medulla, there was no sex difference in AT1aR mRNA expression in intact DS rats on LS or HS. On LS, ovariectomy significantly increased AT1aR mRNA expression compared with intact males or females, whereas, on HS, AT1aR was downregulated in OVX DS rats so that the receptor levels were similar in all groups (Fig. 5, A and B).

Fig. 5.

Renal ANG II type 1 receptor (AT1aR) mRNA expression in male, female, CAS, and OVX DS rats on LS and HS diet. Animals were maintained in LS diet and at 17 wk of age were randomly assigned to receive LS or HS diet for a 4-wk period. At the end of the experimental protocol, kidneys were removed and separated into cortex (A) and medulla (B), and AT1aR mRNA levels were quantified by real-time RT-PCR. *P < 0.05.

Effect of castration on sex steroids and kidney and body weight in male DS rats on HS diet (protocol B).

As shown in Table 1, castration significantly reduced plasma testosterone and did not alter plasma levels of estradiol. CAS rats on 8% salt diet for 4 wk had significantly lower body weights and kidney weight-to-body weight ratios than intact males.

Table 1.

Effect of castration on plasma sex steroids and body and kidney weight

| Male | Castrated | |

|---|---|---|

| Body wt, g | 456.5±8.7 | 405.0±3.4* |

| Plasma testosterone, ng/dl | 203.0±58.4 | 1.0±0.2* |

| Plasma estradiol, pg/ml | 1.7±0.53 | 1.9±0.78 |

| Kidney/body wt, ×103 | 4.89±0.21 | 3.70±0.08* |

Values are means ± SE.

P < 0.05 vs. male.

Effect of castration on BP in male DS rats (protocol B).

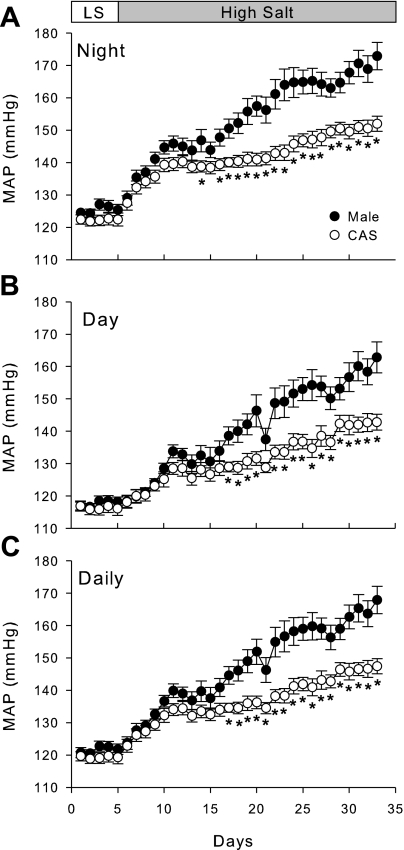

To determine whether castration modulates BP in DS rats on LS and HS diets, we measured BP in intact and CAS DS rats by radiotelemetry (Fig. 6). On LS diet, castration of male DS rats had no effect on BP. When rats were given HS diet, BP initially increased in both intact and CAS rats, showing salt sensitivity in both groups; however, castration significantly attenuated the progressive increase in BP during HS diet.

Fig. 6.

Effect of castration and HS diet on blood pressure. Intact and CAS males were maintained in LS diet and at 17 wk of age were challenged with HS diet for 4 wk. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was measured by radiotelemetry during night time (A), day time (B), or averaged for 24 h (C). *P < 0.05 vs. intact males, n = 11/ group.

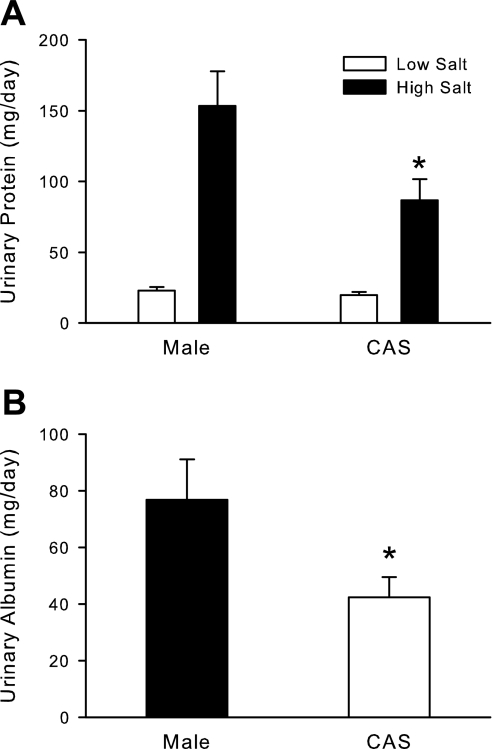

Effect of castration on urinary protein and albumin excretion in male DS rats (protocol B).

On LS diet, there was no difference in urinary protein excretion between intact and CAS DS rats (Fig. 7A), but HS diet significantly increased protein excretion in both intact and CAS DS. Castration significantly attenuated the increase in protein excretion compared with intact males. At the end of 4 wk on HS diet, castration also significantly reduced urinary albumin excretion compared with intact males (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Effect of gonadectomy on urinary protein and albumin excretion in intact and CAS male DS rats. Intact and CAS males were maintained on LS diet and at 17 wk of age were challenged with HS diet for 4 wk. Rats were placed in metabolic cages, and urine was collected to measure total protein (A) or albumin (B) on LS diet and after 4 wk of HS diet. Data are expressed as mg protein or albumin excreted/24 h. *P < 0.05 vs. intact male, n = 11/group.

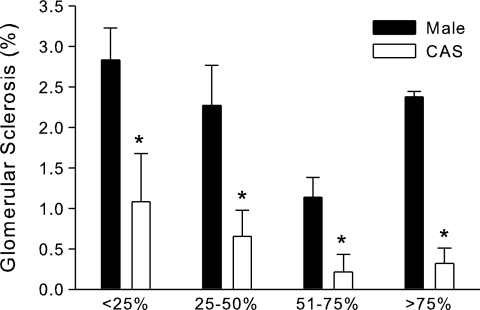

Effect of castration on glomerular sclerosis in male DS rats on HS diet (protocol B).

At the end of 4 wk on HS diet, kidney sections were examined by light microscopy for assessment of glomerular injury. As shown in Fig. 8, the level of glomerular sclerosis, although mild, was significantly greater in intact males than CAS rats.

Fig. 8.

Effect of castration on glomerular sclerosis in intact and CAS male DS rats. Intact and CAS males were maintained on LS diet and at 17 wk of age were challenged with HS diet for 4 wk. At the end of the experimental protocol, kidneys were removed for histological analysis of glomerular injury. *P < 0.05 vs. intact male, n = 5/group.

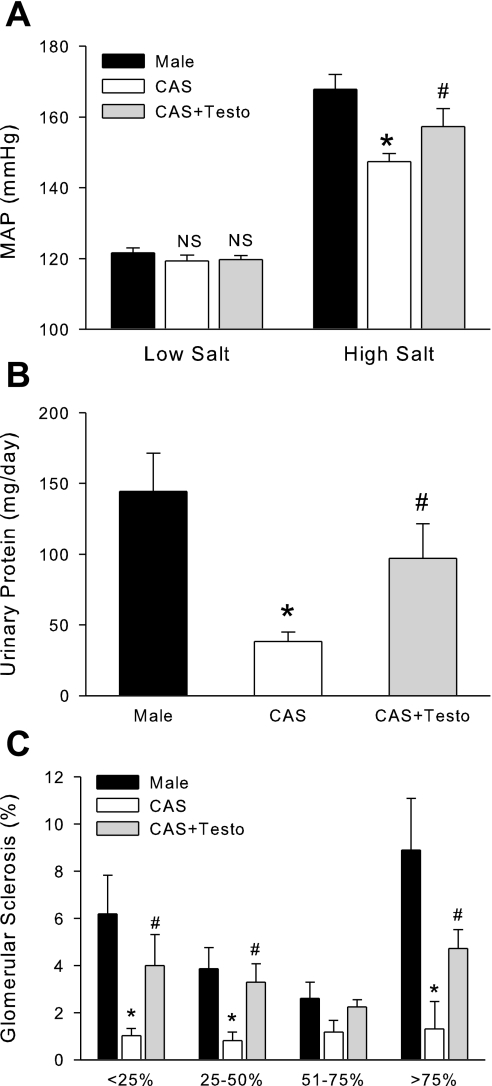

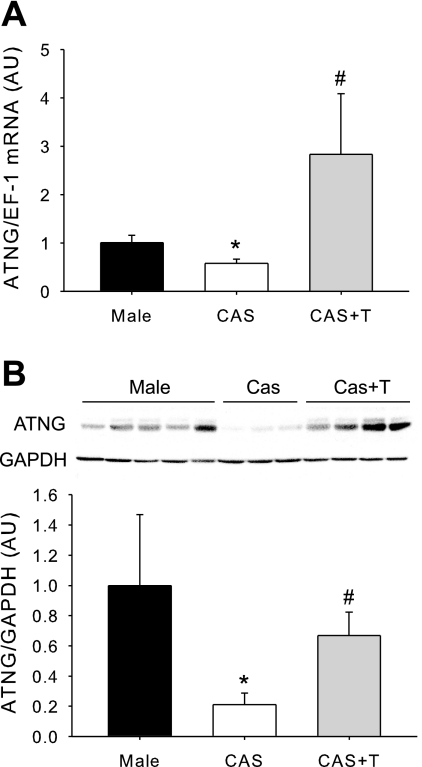

Effect of testosterone replacement to CAS rats on BP, renal injury, and intrarenal angiotensinogen levels (protocol C).

To confirm the contribution of testosterone to hypertension, renal injury, and upregulation of renal angiotensinogen that occurs with HS in intact male DS, another cohort of rats was studied, using the same experimental design described above in protocol B, with the addition of a group of CAS DS that received testosterone replacement. At the end of the experimental protocol, plasma levels of testosterone in CAS rats replaced with testosterone were similar to values in intact males (218.2 ± 89.56 vs. 297.0 ± 110.5 ng/dl, P = not significant). Testosterone replacement significantly increased BP in CAS rats on HS diet to values similar to those found in intact males (Fig. 9A). Protein excretion was elevated significantly in CAS given testosterone to similar values as found in intact males (Fig. 9B). Glomerular sclerosis was reduced significantly by CAS, and testosterone replacement increased glomerular injury to similar levels as found in intact male DS (Fig. 9C). Renal angiotensinogen mRNA and protein were also significantly upregulated by testosterone replacement in CAS rats (Fig. 10, A and B).

Fig. 9.

Effect of testosterone replacement on blood pressure and renal injury in male and CAS rats on HS diet (data from protocol C). Testosterone pellets were implanted in CAS DS rats at 8 wk of age. At 15 wk of age, blood pressure was measured in intact, CAS, and CAS + testosterone replacement (CAS + Testo) (n = 4/group) rats during LS diet and after 4 wk of HS diet. A: MAP average of the last 5 days of LS or HS diet. B: urinary protein excretion. C: glomerular sclerosis. P < 0.05 vs. intact male (*) and vs. CAS (#).

Fig. 10.

Effect of testosterone replacement on kidney angiotensinogen expression (data from protocol C). Testosterone pellets were implanted in CAS DS rats at 8 wk of age, and, at 17 wk of age, intact males, CAS, and CAS + Testo (n = 4/group) rats were challenged with HS diet for 4 wk. At the end of the experimental protocol, mRNA (A) and protein (B) angiotensinogen levels were quantified in total kidney by real-time RT-PCR or Western blot, respectively. P < 0.05 vs. intact male (*) and vs. CAS (#).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study are: 1) there is a sexually dimorphic expression of renal angiotensinogen mRNA and protein in DS on HS, with males exhibiting higher levels than females; 2) castration attenuates HS-induced increases in intrarenal angiotensinogen expression in male DS; 3) castration of male DS attenuates the increased BP and renal injury caused by HS diet; and 4) testosterone replacement to CAS DS rats elevates BP and increases renal injury and intrarenal angiotensinogen.

Kobori et al. (16, 18) showed that, when male DS are placed on HS, intrarenal angiotensinogen expression is increased. Furthermore, these investigators found that the intrarenal levels of ANG II were not suppressed by HS, suggesting that an active intrarenal RAS is present in DS rats on HS diet. Our study confirms those observations but shows that this response is sex steroid dependent. With HS diet, cortical expression of angiotensinogen mRNA and protein was upregulated further in males but not in female DS rats, and this upregulation was attenuated by castration. Thus the upregulation of angiotensinogen protein expression in response to HS is androgen dependent in DS and likely contributes to the higher BP in response to HS in males. Indeed, it has been shown that upregulation of renal angiotensinogen causes hypertension and renal injury in transgenic mice (27).

Sex differences in BP in DS rats have been addressed previously. Crofton and colleagues (4) reported that BP was higher in male DS rats than in females when placed on HS diet. These data were further confirmed by Hinojosa-Laborde and colleagues (10), who showed that ovariectomy of females resulted in an increase in BP that was independent of salt diet, since the increase in BP with ovariectomy was present regardless of whether rats were maintained on LS or HS diet.

Our study carries these original observations further and shows that castration of males modulates BP in DS rats just as ovariectomy does in females. The modulation of BP by testosterone in males is salt dependent, whereas the modulation in females is not, since ovariectomy increases BP in female DS regardless of salt diet (10). In contrast to females, our study reveals that BP and renal injury are not different in intact and CAS male DS rats on LS diet. However, although both intact and CAS male rats exhibit salt sensitivity of BP, since BP increased in both groups following the change to HS diet, intact male rats developed significantly higher BP in response to HS than their CAS male counterparts.

On HS diet, an increase in renal angiotensinogen protein in male DS is capable of increasing renin activity if the renin enzyme is not performing at maximal velocity even if renin levels are decreased on HS. In our study, renal renin mRNA levels were similar in all groups on HS, suggesting that expression of renin itself played a minor role in the sex-dependent increase in BP in DS males. Thus an increase in angiotensinogen protein expression in the kidney likely drives the pressor response to HS in male DS rats contributing to the sex difference in BP response. Terada et al. (30a) reported that angiotensinogen mRNA was expressed largely in the convoluted and proximal straight tubules with small amounts present in the glomeruli and vasa recta. Androgens have been shown to stimulate sodium reabsorption by the proximal tubule in a RAS-dependent manner (24). Thus one could speculate that the androgen-mediated increase in renal angiotensinogen, and thereby increase in ANG II, could cause an increase in sodium reabsorption in the proximal tubule in response to HS in DS males, leading to their exaggerated pressor response to HS diet.

It was somewhat surprising that ACE mRNA expression was not different in male and female DS but was increased with gonadectomy in both groups. The increase in ACE mRNA was also independent of HS diet. Thus these data suggest that, in situations in which there is a reduction in sex steroids in both males and females, such as with aging, there is an upregulation of ACE that could play a role in mediating age-dependent increases in BP. However, in our present studies, it is likely that, since castration reduces angiotensinogen expression and thus attenuates renin activity, that led to a reduction in substrate for ACE. Thus, in the absence of adequate ANG I, an increase in ACE expression with castration will not result in an increase in ACE activity or a subsequent increase in ANG II production. This is evidenced by studies showing that mice that overexpress ACE are not hypertensive (19), whereas mice that overexpress angiotensinogen are hypertensive (27).

Testosterone has been shown to be involved in the development of renal injury in several experimental models. For example, we have previously shown that, in the aging male SHR (8), despite the fact that their plasma testosterone levels are decreased compared with young male SHR, castration still protects against renal injury. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to show that castration attenuates the development of renal injury in male DS rats fed a HS diet. The beneficial effect of castration may be in part BP-mediated, since castration decreased BP in male DS rats. Whether the effect of testosterone on renal injury in male DS rats on HS diet is entirely hemodynamically mediated should be evaluated in future studies.

Although changes in the intrarenal RAS are likely important mechanisms in mediating the sex difference in BP in response to HS in male and female DS rats, the role of the RAS in mediating the higher BP in OVX DS is not clear from our study. After 12–14 wk of age, OVX females maintained on LS exhibit higher BP than intact females (9, 10). In the present study, we found that ovariectomy had no effect on intrarenal angiotensinogen expression in female rats, either on LS or HS. Similarly, neither cortical renin nor AT1aR expression was affected by ovariectomy. Medullary renin and AT1aR expression were higher in OVX than intact females, however, on LS, but not HS. Estrogen has been shown to increase angiotensinogen levels in the liver (14) and to reduce the number of AT1aR in many tissues, including the adrenal, kidney, and vasculature (6), attenuating the tissue responsiveness to ANG II. Prieto-Carrasquero and colleagues (23) recently reported that the two-kidney, one-clip Goldblatt maneuver, a high circulating ANG II state, leads to increases in renin in the medulla of rats via an AT1R mechanism and to an increase in sodium reabsorption and mediates the Goldblatt hypertension (23). Our data support the possibility that a similar situation occurs in kidneys of OVX DS rats on LS. Thus our data suggest that, on LS, the RAS does play a role in mediating the higher BP in OVX DS compared with intact females. However, our data do not support a role for the intrarenal RAS in mediating the higher BP in OVX females on HS since angiotensinogen, renin, and AT1aR expression are similar in intact female and OVX DS rats. We speculate rather that differences in the endothelin system between intact and OVX females are induced by HS, leading to the higher BP in OVX DS. Future studies will be necessary to evaluate this hypothesis.

As portrayed in the data in Fig. 6, it is obvious that a portion of the salt sensitivity of BP in DS rats is independent of sex steroids, since all DS rats, intact males, females, CAS, or OVX, exhibit increases in BP with HS diet. However, how androgens augment the salt-mediated pressor response in DS males is not clear. Unlike in SHR in which castration decreases the expression of angiotensinogen even on a normal salt diet (3), castration in DS rats on LS diet had no effect on angiotensinogen expression. HS diet has been shown to cause an increase in oxidative stress (13). Androgen-mediated hypertension is in part mediated by oxidative stress, such as in male SHR, for example (28). Furthermore, an increase in intrarenal ANG II, which our data suggest occurs with testosterone supplementation due to increased angiotensinogen expression, will cause an increase in intrarenal oxidative stress (20). In fact, Kobori and Nishiyama (17) reported that the increase in renal angiotensinogen expression with HS diet in DS males was abolished by administration of tempol, a superoxide anion scavenger. We hypothesize then that HS diet increases BP in both intact male and CAS male DS rats because of the increase in oxidative stress. However, the combination of androgens, ANG II, and oxidative stress in response to HS diet causes an augmented response in BP in male DS that is not present when one has a simple increase in oxidative stress alone with HS (as in CAS rats). This hypothesis remains to be tested in future studies.

In summary, our data support the idea that salt-sensitive hypertension in male DS rats is because of an inappropriate activation of intrarenal RAS driven by increases in intrarenal angiotensinogen. The presence of testosterone likely constitutes a critical factor in augmenting the pressor response, renal injury, and upregulation of intrarenal angiotensinogen caused by HS diet in male DS rats.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Postdoctoral Fellowships from the American Heart Association, Southeast Affiliate (0425461B to L. L. Yanes, 0525320B to R. Iliescu, 0725561B to J. C. Sartori-Valinotti), a Scientific Development Grant (0830239N to L. L. Yanes and 0830416N to R. Iliescu), and by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-69194, HL-66072, and HL-51971.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Celso E. Gomez-Sanchez (G. V. Montgomery Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Jackson, MS) and Christoph P. R. Klett (University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS) for generously providing the anti-rat albumin and anti-rat angiotensinogen antibodies, respectively.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bradford M A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding (Abstract). Anal Biochem 72: 248, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandramohan G, Bai Y, Norris K, Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Vaziri ND. Effects of dietary salt on intrarenal angiotensin system, NAD(P)H oxidase, COX-2, MCP-1 and PAI-1 expressions and NF-kappaB activity in salt-sensitive and -resistant rat kidneys. Am J Nephrol 28: 158–167, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YF, Naftilan AJ, Oparil S. Androgen-dependent angiotensinogen and renin messenger RNA expression in hypertensive rats. Hypertension 19: 456–463, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crofton JT, Ota M, Share L. Role of vasopressin, the renin-angiotensin system and sex in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension. J Hypertension 11: 1031–1038, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahl LK, Heine M, Tassinari L. Effects of chronic excess salt ingestion: evidence that genetic factors play an important role in susceptibility to experimental hypertension. J Exp Med 115: 1173–1190, 1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean SA, Tan J, O'Brien ER, Leenen FH. 17beta-estradiol downregulates tissue angiotensin-converting enzyme and ANG II type 1 receptor in female rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R759–R766, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellison KE, Ingelfinger JR, Pivor M, Dzau VJ. Androgen regulation of rat renal angiotensinogen messenger RNA expression. J Clin Invest 83: 1941–1945, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fortepiani LA, Yanes L, Zhang H, Racusen LC, Reckelhoff JF. Role of androgens in mediating renal injury in aging SHR. Hypertension 42: 952–955, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinojosa-Laborde C, Craig T, Zheng W, Ji H, Haywood JR, Sandberg K. Ovariectomy augments hypertension in aging female Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension 44: 405–409, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinojosa-Laborde C, Lange DL, Haywood JR. Role of female sex hormones in the development and reversal of dahl hypertension. Hypertension 35: 484–489, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji H, Menini S, Mok K, Zheng W, Pesce C, Kim J, Mulroney S, Sandberg K. Gonadal steroid regulation of renal injury in renal wrap hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F513–F520, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khalid M, Ilhami N, Giudicelli Y, Dausse JP. Testosterone dependence of salt-induced hypertension in Sabra rats and role of renal alpha(2)-adrenoceptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 300: 43–49, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitiyakara C, Chabrashvili T, Chen Y, Blau J, Karber A, Aslam S, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Salt intake, oxidative stress, and renal expression of NADPH oxidase and superoxide dismutase. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2775–2782, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klett C, Hellmann W, Hackenthal E, Ganten D. Modulation of tissue angiotensinogen gene expression by glucocorticoids, estrogens, and androgens in SHR and WKY rats. Clin Exp Hypertens 15: 683–708, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klett CP, Granger JP. Physiological elevation in plasma angiotensinogen increases blood pressure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R1437–R1441, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Expression of angiotensinogen mRNA and protein in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 431–439, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobori H, Nishiyama A. Effects of tempol on renal angiotensinogen production in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 315: 746–750, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobori H, Nishiyama A, Abe Y, Navar LG. Enhancement of intrarenal angiotensinogen in Dahl salt-sensitive rats on high salt diet. Hypertension 41: 592–597, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krege JH, Kim HS, Moyer JS, Jennette JC, Peng L, Hiller SK, Smithies O. Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene mutations, blood pressures, and cardiovascular homeostasis. Hypertension 29: 150–157, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laursen JB, Rajagopalan S, Galis Z, Tarpey M, Freeman BA, Harrison DG. Role of superoxide in angiotensin II-induced but not catecholamine-induced hypertension. Circulation 95: 588–593, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morimoto A, Uzu T, Fujii T, Nishimura M, Kuroda S, Nakamura S, Inenaga T, Kimura G. Sodium sensitivity and cardiovascular events in patients with essential hypertension. Lancet 350: 1734–1737, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakaya H, Sasamura H, Mifune M, Shimizu-Hirota R, Kuroda M, Hayashi M, Saruta T. Prepubertal treatment with angiotensin receptor blocker causes partial attenuation of hypertension and renal damage in adult Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Nephron 91: 710–718, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Botros FT, Pagan J, Kobori H, Seth DM, Casarini DE, Navar LG. Collecting duct renin is upregulated in both kidneys of 2-kidney, 1-clip goldblatt hypertensive rats. Hypertension 51: 1590–1596, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quan A, Chakravarty S, Chen JK, Chen JC, Loleh S, Saini N, Harris RC, Capdevila J, Quigley R. Androgens augment proximal tubule transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F452–F459, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapp JP, Tan SY, Margolius HS. Plasma mineralocorticoids, plasma renin, and urinary kallikrein in salt-sensitive and salt-resistant rats. Endocr Res Commun 5: 35–41, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reckelhoff JF, Zhang H, Granger JP. Testosterone exacerbates hypertension and reduces pressure-natriuresis in male spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 31: 435–439, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sachetelli S, Liu Q, Zhang SL, Liu F, Hsieh TJ, Brezniceanu ML, Guo DF, Filep JG, Ingelfinger JR, Sigmund CD, Hamet P, Chan JS. RAS blockade decreases blood pressure and proteinuria in transgenic mice overexpressing rat angiotensinogen gene in the kidney. Kidney Int 69: 1016–1023, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sartori-Valinotti JC, Iliescu R, Fortepiani LA, Yanes LL, Reckelhoff JF. Sex differences in oxidative stress and the impact on blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34: 938–945, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sartori-Valinotti JC, Iliescu R, Yanes LL, Dorsett-Martin W, Reckelhoff JF. Sex differences in the pressor response to angiotensin II when the endogenous renin-angiotensin system is blocked. Hypertension 51: 1170–1176, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeda Y, Zhu A, Yoneda T, Usukura M, Takata H, Yamagishi M. Effects of aldosterone and angiotensin II receptor blockade on cardiac angiotensinogen and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 expression in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens 20: 1119–1124, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Terada Y, Tomita K, Nonoguchi H, and Marumo F. PCR localization of angiotensin II receptor and angiotensinogen mRNAs in rat kidney. Kidney Int 43: 1251–1259, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinberger MH, Fineberg NS, Fineberg SE, Weinberger M. Salt sensitivity, pulse pressure, and death in normal and hypertensive humans. Hypertension 37: 429–432, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinberger MH, Miller JZ, Luft FC, Grim CE, Fineberg NS. Definitions and characteristics of sodium sensitivity and blood pressure resistance. Hypertension 8: II127–II134, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yanes LL, Romero DG, Iles JW, Iliescu R, Gomez-Sanchez C, Reckelhoff JF. Sexual dimorphism in the renin-angiotensin system in aging spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R383–R390, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yanes LL, Sartori-Valinotti JC, Reckelhoff JF. Sex steroids and renal disease: lessons from animal studies. Hypertension 51: 976–981, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]