Abstract

The L-type Ca2+ channel expressed in gastrointestinal smooth muscle is mechanosensitive. Direct membrane stretch and shear stress result in increased Ca2+ entry into the cell. The mechanism for mechanosensitivity is not known, and mechanosensitivity is not dependent on an intact cytoskeleton. The aim of this study was to determine whether L-type Ca2+ channel mechanosensitivity is dependent on tension in the lipid bilayer in human jejunal circular layer myocytes. Whole cell currents were recorded in the amphotericin-perforated-patch configuration, and lysophosphatidyl choline (LPC), lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), and choline were used to alter differentially the tension in the lipid bilayer. Shear stress (perfusion at 10 ml/min) was used to mechanostimulate L-type Ca2+ channels. The increase in L-type Ca2+ current induced by shear stress was greater in the presence of LPC (large head-to-tail proportions), but not LPA or choline, than in the control perfusion. The increased peak Ca2+ current also did not return to baseline levels as in control conditions. Furthermore, steady-state inactivation kinetics were altered in the presence of LPC, leading to a change in window current. These findings suggest that changes in tension in the plasmalemmal membrane can be transmitted to the mechanosensitive L-type Ca2+ channel, leading to altered activity and Ca2+ entry in the human jejunal circular layer myocyte.

Keywords: calcium channel, gastrointestinal, lipid bilayer tension, shear stress, lysophosphatidic acid

the concept of smooth muscle mechanosensitivity of the gut was first introduced in the 1950s with the discovery that smooth muscle can respond to stretch in the absence of extrinsic neural input (2). Later, the development of patch-clamp techniques led to the discovery of mechanosensitivity as an inherent property of some ion channels (15, 26), suggesting that these ion channels transduce mechanosensitivity in a variety of cells. Indeed, cells containing mechanosensitive ion channels are able to directly sense and then respond to mechanical forces (26, 40) by altering the flow of ions across the cell membrane.

The smooth muscle of the gut, like other smooth muscle, requires entry of Ca2+ for contraction. The increase in intracellular Ca2+ that precedes contraction is due, in part, to Ca2+ entry from outside the cell and, in part, to release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. These processes are interdependent, because Ca2+ release from intracellular stores relies largely on entry of extracellular Ca2+, dubbed Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (20). The major pathway for extracellular Ca2+ into the intestinal smooth muscle cell is the L-type Ca2+ channel (11), as supported by evidence that L-type Ca2+ channel blockers abolish effectively inward Ca2+ current.

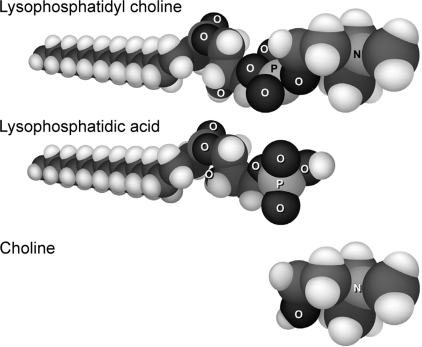

Intestinal smooth muscle L-type Ca2+ channels are gated by voltage and a number of chemical mediators (7, 22, 41, 44, 53). The channels are also mechanosensitive, and increased peak current through the channel is observed with mechanical perturbation of the cell membrane (9, 18, 24). This mechanosensitivity is an inherent property of the pore-forming unit of the channel (24). Current models of ion channel mechanosensitivity ascribe mechanosensitivity through two major mechanisms. One mechanism, transfer of force through connections between the cytoskeleton and the ion channel, is operative in human gastrointestinal smooth muscle, where NaV1.5 mechanosensitivity is abolished by disruption of the actin cytoskeleton without an effect on L-type Ca2+ channel mechanosensitivity (37), suggesting that another mechanism must be operative for the latter. Transfer of force from the lipid bilayer to the ion channel is the second proposed mechanism for ion channel mechanosensitivity (40). This model predicts that the composition, and hence the ability to impart force to the channel, of the lipid bilayer would alter mechanosensitivity. The aim of the present study was to determine whether L-type Ca2+ channel mechanosensitivity is dependent on the characteristics of the lipid bilayer by altering the composition of the bilayer. To differentially alter the tension within the lipid bilayer, we used lysophosphatidyl choline (LPC), which has a polar head and single fatty acid chain, lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), which has a fatty acid tail but no polar head, and choline, which has a polar head but no fatty acid tail. We found that LPC, but not LPA or choline, altered the mechanosensitive response and steady-state kinetics of the channel, suggesting that tension in the lipid bilayer can directly affect L-type Ca2+ channel activity.

METHODS

Dissociation of human jejunal circular smooth muscle cells.

Human jejunal tissue was obtained as surgical waste tissue from bariatric surgery performed for morbid obesity in otherwise healthy subjects. Tissue specimens were harvested directly into chilled buffer solution with warm ischemia times of <30 s. Single, isolated circular smooth muscle cells were obtained from the human jejunal specimens as described previously (38). The freshly isolated cells were used for electrophysiological recordings within 6 h of dissociation.

Electrophysiology.

Whole cell patch-clamp recordings were obtained by using Kimble KG-12 glass pulled on a P-97 puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Electrodes were coated with R6101 (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) and fire polished to a final resistance of 3–5 MΩ. Currents were amplified, digitized, and processed using a Axopatch 200A or 200B amplifier, a Digidata 1322A, and pCLAMP 9 software (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). Data were filtered at 5 kHz with an eight-pole Bessel filter. The junction potential between pipette solution and bath solution was adjusted electronically to zero. Access resistance was recorded, and data were used only if access varied <5 MΩ throughout the experiment. Records were obtained in amphotericin-perforated, whole cell patch-clamp mode to limit rundown of the L-type Ca2+ current. Cells were held at −100 mV and pulsed (for 50 ms each) from −80 to +35 mV in 5-mV steps. The interpulse start-to-start time was 1 s to allow complete recovery from inactivation. All electrophysiological experiments were carried out at room temperature (20°C). Human jejunal circular layer myocytes express three dominant inward currents: a current carried by an L-type Ca2+ channel (CaV1.2) (24), a current carried by an Na+ channel (Nav1.5) (17, 31), and a nonselective current. Under physiological recording conditions, the L-type Ca2+ current is discernable in 85% of cells and the Na+ current in 89% of cells (38). Both are mechanosensitive but can be teased apart, because >90% of Na+ current inactivates <20 ms after initiation of a depolarizing pulse. Data presented in the figures show Na+ and Ca2+ currents. On average, the peak inward Na+ current is 87% greater than Ca2+ current at a holding voltage of −100 mV when both currents are present (−127 ± 8 vs. −68 ± 3 pA, n = 242, P < 0.01).

Mechanical activation of L-type Ca2+ channels.

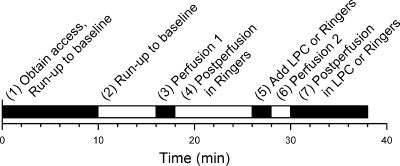

Perfusion of normal Ringer extracellular fluid at a rate of 10 ml/min for 1 min was used as the mechanical stimulus, as reported previously (24). The experimental protocol used to examine changes in peak inward current for the mechanosensitive L-type Ca2+ current was designed with an internal control (Fig. 1). Up to 10 min were allowed for amphotericin B to diffuse to and perforate the cell membrane. An additional 6 min were allowed for run-up until a stable baseline of Ca2+ current was reached. After 1 min of control perfusion with Ringer solution at 10 ml/min, Ca2+ current was allowed to return to baseline for 8 min. Then 100 μl of Ringer solution (control) or a solution of 100 μl of LPC (10 μM final concentration), LPA (10 μM final concentration), or choline (10 μM final concentration) was pipetted directly into the still bath (to prevent mechanoactivation) and allowed 2 min to equilibrate. Subsequently, a second perfusion was performed at the same rate and duration as the first, and a final 8-min postperfusion follow-up period allowed enough time to check for full reversibility of mechanostimulated Ca2+ current. Current was measured at 1- to 2-min intervals during the course of each experiment.

Fig. 1.

Time line showing 7-step experimental protocol of mechanical stimulus and application of amphipathic compounds. LPC, lysophosphatidyl choline.

Steady-state kinetics for activation and inactivation were calculated before and after the separate applications of LPC, LPA, and choline into the extracellular solution. The pulse protocol was similar to that described previously (11); however, in the present experiments, cells were held at −100 mV to allow better separation of the Ca2+ and Na+ currents (17).

Drugs and solutions.

The pipette solution contained (in mM) 130 Cs+, 125 methanesulfonate, 20 Cl−, 5 Na+, 5 Mg2+, 5 HEPES, and 2 EGTA (with final pH adjusted to 7.35 with CsOH). Amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in DMSO and suspended in the pipette solution. The final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1%. The bath solution contained (in mM) 2.54 Ca2+, 159 Cl−, 149.2 Na+, 4.74 K+, 5.5 glucose, and 5 HEPES (300 mmol/kg osmolality, with final pH adjusted to 7.35 with NaOH) for whole cell recordings. All drugs added to extracellular Ringer solution were allowed to equilibrate with the cells for 2 min before data were recorded.

The amphipathic compounds LPC, LPA, and choline (Sigma-Aldrich) were used to increase lateral tension and deformation of the lipid bilayer (Fig. 2). With its large polar head group and single fatty acid tail, LPC will exert more tension in the polar region of the lipid bilayer. This change in membrane characteristics is proposed to alter ion channel conformation, such that LPC may cause ion channels to assume more of a barrel-shaped conformation with a shorter pore (40). Conversely, LPA, like arachidonic acid (AA), lacks a large polar head group and, therefore, is likely to transfer tension to the hydrophobic region of the lipid bilayer, which has been proposed to cause ion channels to assume more of an hourglass shape (40). These conformational changes have been linked to mediating ion channel mechanosensitivity (40). Although LPA shares the same tail as LPC, LPA would more likely influence mechanosensitivity of two-pore domain channels, such as the TREK family (32), rather than L-type Ca2+ channels; however, LPA also has been shown to affect intracellular Ca2+ stores (29, 30). Choline, entirely missing a fatty acid tail, would reside outside the hydrophobic region.

Fig. 2.

Molecular space-fill models of LPC, lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), and choline. Charge and shape of amphipathic compounds direct location of incorporation into the lipid bilayer and induce a subsequent conformational change of proteins embedded in the bilayer.

Data analysis.

Values are means ± SE. Raw values from the same cells before and after addition of drug or control solution were evaluated by Student's t-test (two-tailed). P < 0.05 was considered significant. Current-voltage curves plotted peak inward current vs. voltage steps. Data were normalized using the following formula: Inorm = 100(Iv)/(Imax), where Inorm is the normalized peak inward current at a particular voltage sweep, Iv is the current at each voltage sweep, and Imax is the maximum peak inward current from the set of traces (usually the peak inward current at 0 mV). Steady-state activation and inactivation curves were fit with the Boltzmann equation: I/IMAX = 1/[1 + exp(V1/2 − V)/k], where V1/2 is the voltage at half-maximal activation or inactivation.

RESULTS

Membrane shear stress by fluid perfusion increases Ca2+ current.

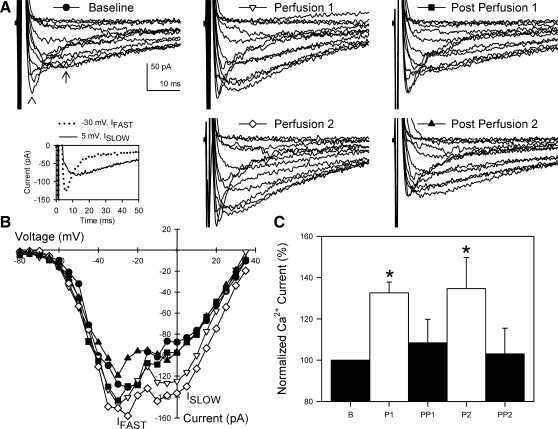

Under control conditions, perfusion increased inward L-type Ca2+ current (33 ± 5% from baseline to 1st perfusion, n = 6, P < 0.05; Fig. 3). This increase is consistent with our previously published data (9, 18, 24). The increase in Ca2+ current (peak Ca2+ current) dissipated over the 8 min after cessation of fluid perfusion, and at 8 min there was no difference between pre- and postperfusion periods (10 ± 11% from baseline to the end of the 1st postperfusion period, n = 6, P > 0.05). Repeat application of shear stress to the same cells produced similar increases in Ca2+ current compared with the first perfusion period: 1 ± 10% change in peak Ca2+ current between the first and second perfusion (n = 6, P = 0.92) and 35 ± 15% increase between baseline and the second perfusion (n = 6, P < 0.05). Again, 8 min after the end of the perfusion, Ca2+ current had returned to baseline levels: 3 ± 12% change between baseline and the second postperfusion (n = 6, P > 0.05). Both perfusions also increased Na+ current, as previously described (37).

Fig. 3.

Shear stress increased L-type Ca2+ current in circular smooth muscle cells of human jejunum. A: representative whole cell Ca2+ (arrow) currents before, during, and after 2 consecutive rounds of shear stress induced by perfusion. Arrowhead shows faster Na+ current. Inset: visual identification of Na+ (−30 mV, IFAST) and Ca2+ (0 mV, ISLOW) currents by step voltage and kinetics. B: current-voltage plots of peak inward currents from representative cell in A. IFAST peaked at −30 to −25 mV; ISLOW peaked at −5 to 5 mV. C: normalized peak Ca2+ currents averaged from 6 cells. *P < 0.05 vs. baseline (B). P1, 1st perfusion; PP1, 1st postperfusion; P2, 2nd perfusion; PP2, 2nd postperfusion.

LPC augments Ca2+ current increase to shear stress.

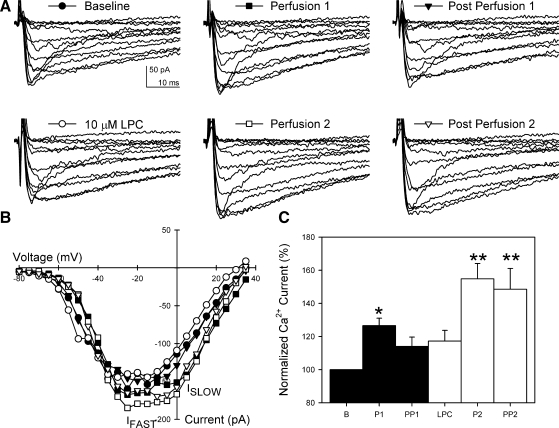

After addition of 10 μM LPC directly to the extracellular solution, no change in Ca2+ current was observed immediately or 2 min after LPC (3 ± 3% change 2 min after addition of LPC, n = 6, P > 0.05; Fig. 4). However, with application of shear stress, the increase in Ca2+ current was significantly greater (55 ± 9%, n = 6, P < 0.01) than that observed in the control first perfusion in the same cells without LPC (26 ± 4%, n = 6, P < 0.05). There was no effect of LPC on Na+ current (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

LPC increased L-type Ca2+ current during and after mechanoactivation. A: representative whole cell Ca2+ currents responding to 2 consecutive mechanical stimuli before and after application of 10 μM LPC. Faster Na+ current is also shown. LPC had no effect on Na+ current. B: current-voltage plots of peak inward currents from representative cell in A. IFAST peaked at −30 to −25 mV; ISLOW peaked at −5 to 5 mV. C: normalized peak Ca2+ currents averaged from 6 cells. *P < 0.05 vs. B. **P < 0.05 vs. B and P1.

Effect of LPC on reversibility of mechanical activation of L-type Ca2+ current.

Previous work showed that, in HEK-293 cells transfected with CaV1.2 (24), mechanical activation of L-type Ca2+ current is reversible on cessation of the stimulus. Similarly, control experiments in human jejunal circular smooth muscle cells demonstrated that L-type Ca2+ current was reversible after each successive perfusion. However, after the addition of LPC, Ca2+ current increased to a new plateau after the mechanical stimulation (48 ± 12% from baseline to 2nd postperfusion, n = 6, P < 0.05; Fig. 4). Although Ca2+ current returned to baseline after the control perfusion (14 ± 6%, n = 6, P > 0.05, Fig. 4), it remained at the level of perfusion-induced current increase in the presence of LPC (−4 ± 6% from 2nd perfusion to the end of postperfusion, n = 6, P > 0.05; Fig. 4) and did not return to baseline.

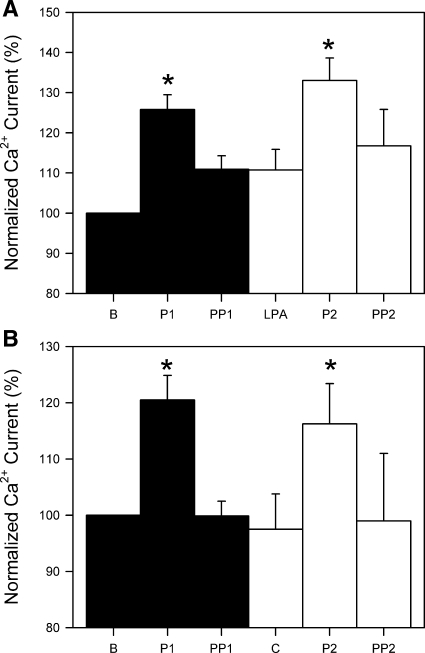

Neither LPA nor choline affects Ca2+ current increase with shear stress.

In contrast to LPC, which has a polar head and a single fatty acid chain, choline has a polar head but no fatty acid tail, and LPA has a fatty acid tail but no polar head (Fig. 2). The effect of these drugs was, therefore, tested as controls for LPC. Separate double-perfusion experiments were performed with LPA and choline. In both sets of experiments, similar increases in Ca2+ current were noted with the first (control) perfusion: 26 ± 4% increase from baseline (n = 6, P < 0.05; Fig. 5A) in the cells treated with LPA and 20 ± 4% increase from baseline (n = 6, P < 0.05; Fig. 5B) in the cells treated with choline. Neither LPA nor choline produced changes in Ca2+ current within 2 min of application: 0 ± 2% with LPA (n = 6, P > 0.05; Fig. 5A) and −3 ± 5% with choline (n = 6, P > 0.05; Fig. 5B). Furthermore, neither compound changed the magnitude of the expected Ca2+ current increase with the second perfusion: 20 ± 3% with LPA (n = 6, P < 0.05; Fig. 5A) and 19 ± 2% with choline (n = 6, P < 0.01; Fig. 5B). Mechanical activation of Ca2+ current was also reversible in the presence of LPA or choline: 5 ± 5% and 0 ± 7% increase compared with preperfusion current for LPA and choline, respectively (n = 6 each, P > 0.05; Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

LPA (10 μM) and choline (C, 10 μM) did not increase L-type Ca2+ current mechanoactivation. A and B: inward Ca2+ currents normalized to baseline current from each cell. Values are means ± SE (n = 6). *P < 0.05 vs. B.

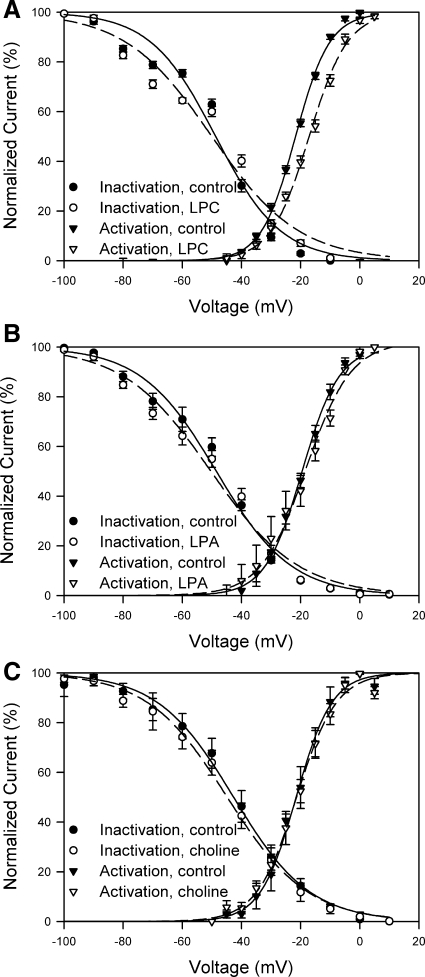

LPC, but not LPA or choline, alters steady-state kinetics of L-type Ca2+ channel.

To further identify whether the altered response to shear stress in the presence of LPC was secondary to a change in the gating of the channel, we tested whether LPC alters steady-state kinetics of the L-type Ca2+ channel in these human jejunal circular smooth muscle cells. After adding LPC, we observed a change in the slope [−11 ± 2 (control) and −15 ± 2 (LPC), P < 0.05] but not V1/2 [−49 ± 2 mV (control) and −50 ± 3 mV (LPC), P > 0.05] of the inactivation curves (Fig. 6A, n = 12). We did not observe a change in slope of the activation curve [5.7 ± 0.3 (control) and 6.5 ± 0.8 (LPC), P > 0.05], but we did observe a positive (5-mV) shift in V1/2 [−22 ± 4 mV (control) and −17 ± 1 mV (LPC), P < 0.05, n = 12]. The fit was tighter for the activation kinetics than for inactivation. The net result of these changes in steady-state activation and inactivation kinetics due to LPC was an increase in the L-type Ca2+ window current consistent with the increase in current seen after mechanical activation of the channel. Neither LPA nor choline altered the slope or V1/2 of activation or inactivation steady-state kinetics (Fig. 6, B and C).

Fig. 6.

LPC altered steady-state L-type Ca2+ channel kinetics. Steady-state activation and inactivation kinetics of human jejunal L-type Ca2+ channel in the presence of LPC (A, n = 12), LPA (B, n = 11), or choline (C, n = 4). Controls were recorded in each cell before addition of the amphipathic compound.

DISCUSSION

The L-type Ca2+ channel expressed in human jejunal circular layer myocytes is mechanosensitive (9, 24), demonstrating an increase in Ca2+ entry induced by membrane shear stress. The main finding of the present study was that a change in the tension of the lipid bilayer by addition of LPC increased mechanosensitivity of the L-type Ca2+ channel. LPC increased window current through altered steady-state activation and inactivation kinetics, providing a likely mechanism for the observed increase in mechanosensitivity of the L-type Ca2+ channel in the presence of LPC. The effect of LPC on the Ca2+ current was not seen with choline or LPA, compounds in the same class of molecules but with significant structural differences.

Gastrointestinal motility is controlled at several levels. Enteric nerves generate stereotypic motor patterns, receive input from extrinsic nerves, and regulate the function of smooth muscle and interstitial cells of Cajal. Interstitial cells of Cajal generate the electrical slow wave (19, 48), modulate neuronal input to smooth muscle (3, 47), transduce mechanical information (39, 43, 46, 49), and regulate the membrane potential of smooth muscle (10, 35). Smooth muscle is not only the final common pathway for contractility, but it can also respond directly to external mechanical stimuli by changes in function of its ion channels, including opening of L-type Ca2+ channels and, thereby, increase Ca2+ entry (18) into the cell and, thus, contractile strength. Although the cytoskeleton has been shown to affect other voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in cells from other tissues (13, 16, 45), previous work on the human jejunal L-type Ca2+ channel showed that disruption of the cytoskeleton had no effect on its mechanosensitivity, suggesting that force was not transduced to the channel through the cytoskeleton (39). By exploiting different physical conformations of amphipathic compounds to change membrane tension, the data in our study suggest that force can be transmitted to the channel from the bilayer.

Amphipathic compounds such as LPC and LPA can incorporate into the lipid bilayer of cells or independently form micelles (23, 33, 40). Together with their role as structural elements of the membrane, lysophospholipids also modulate the function of several membrane proteins, including ion channels. LPC, LPA, or AA modulates TREK channels (4, 21, 25, 33), LPC modulates T-type Ca2+ channels (55), LPC or sphingosine-1-phosphate modulates transient receptor potential channel type 5 (1, 50), LPC modulates Na+ channels (14), and LPA modulates a Cl− channel (52). The effects of lysophospholipids on these ion channels are diverse. Direct and indirect effects on membrane proteins have been demonstrated through a change in the physical properties of the membrane (56). Furthermore, lysophospholipids can also activate intracellular signaling pathways. LPA is known to exert effects on several intracellular signaling pathways, most notably G protein-coupled receptors (27). LPC also activates several pathways, including a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (42) and G protein receptor-coupled pathways (12). The results of the present experiments showed that LPC had no effect on the size of the baseline Ca2+ current or on baseline channel kinetics, yet LPC had a specific effect on mechanosensitivity, which supports the notion that the effects of LPC are mediated through changes in membrane tension, rather than activation of intracellular signaling cascades or changes in the membrane proteins. Also, prior work has not demonstrated an impact of disruption of channel phosphorylation on mechanosensitivity in intestinal L-type Ca2+ channels (24), again arguing against activation of a G protein-coupled receptor as a pathway accounting for the effects of LPC seen in the present study.

The effect of LPC on the L-type Ca2+ channel does not appear to be a nonspecific interaction between the lipid bilayer and an ion channel, because there was no effect of addition of LPC on Nav1.5, another mechanosensitive ion channel expressed in human gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells. Nav1.5 mechanosensitivity has been shown previously to depend on an intact cytoskeleton. Application of shear stress on the α-subunit of the L-type Ca2+ channel expressed in human embryonic kidney cells is sufficient to reproduce mechanosensitivity (24), suggesting a direct interaction between the pore-forming subunit of the L-type Ca2+ channel and the membrane. The increase in Ca2+ current in response to mechanical stimulation was transient under control conditions. Within 8 min of cessation of shear stress to the membrane, the Ca2+ current returned to pre-shear stress levels, suggesting that the mechanism that allows transmission of force to the pore-forming subunit is readily reversible. The failure of the L-type Ca2+ current to return to pre-shear stress values after addition of LPC, but not after LPA or choline, suggests that the level of membrane tension is an important determinant of the sustained response to a stimulus. The mechanisms by which force from the lipid bilayer alters Ca2+ channel kinetics are not known. Potential reasons for this include a limitation of the ability of the L-type Ca2+ channel to undergo conformational changes once mechanoactivated or a different energy requirement to change states as a result of the increased tension in the lipid bilayer.

Analysis of the activation/inactivation kinetics of the channel with LPC in the bath solution revealed changes in activation and inactivation of the L-type Ca2+ channel, leading to a larger window current than observed in normal extracellular fluid or in the presence of LPA or choline. This change was not seen unless the channel was mechanically activated. The change in the window current observed in the presence of LPC is of likely importance, because it not only reflects increased current at the baseline “window” voltages but, also, a rightward shift in the activation curve toward membrane potentials that are likely closer to the physiological resting membrane potential of intestinal myocytes.

LPC, a product of hydrolysis of oxidized phospholipids, is generated under physiological and pathophysiological conditions (6, 34, 51). Micromolar concentrations can be found in plasma (5). Production of LPC from membrane phosphatidylcholines is regulated tightly. The concentration of LPC in the plasma is dependent on paraoxonases (34) and lysophospholipases (28) and is altered in disease states such as ischemia (6, 36) and cancer (8, 54). The concentrations of LPC used in the present study are within the range that may occur in the human body. Given that a particular gastrointestinal smooth muscle cell is constantly either actively contracting or being deformed by neighboring contracting cells, the concentration of LPC may alter Ca2+ entry into gastrointestinal smooth muscle, thereby altering contractility.

In summary, the data presented in this report suggest that mechanosensitivity of the L-type Ca2+ channel in human gastrointestinal circular smooth muscle is modulated by LPC, likely through a change in lipid bilayer tension. This regulatory mechanism may have pathophysiological relevance.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-57061 and DK-52766.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gary Stoltz for tissue dissection and cell dissociation and Kristy Zodrow for secretarial assistance.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beech DJ Bipolar phospholipid sensing by TRPC5 calcium channel. Biochem Soc Trans 35: 101–104, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulbring E Correlation between membrane potential, spike discharge and tension in smooth muscle. J Physiol 128: 200–221, 1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns AJ, Lomax AE, Torihashi S, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Interstitial cells of Cajal mediate inhibitory neurotransmission in the stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 12008–12013, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chemin J, Patel A, Duprat F, Zanzouri M, Lazdunski M, Honore E. Lysophosphatidic acid-operated K+ channels. J Biol Chem 280: 4415–4421, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croset M, Brossard N, Polette A, Lagarde M. Characterization of plasma unsaturated lysophosphatidylcholines in human and rat. Biochem J 345: 61–67, 2000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daleau P Lysophosphatidylcholine, a metabolite which accumulates early in myocardium during ischemia, reduces gap junctional coupling in cardiac cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 31: 1391–1401, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Yazbi AF, Cho WJ, Cena J, Schulz R, Daniel EE. Smooth muscle NOS, co-localized with caveolin-1, modulates contraction in mouse small intestine. J Cell Mol Med 12: 1404–1415, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang X, Gaudette D, Furui T, Mao M, Estrella V, Eder A, Pustilnik T, Sasagawa T, Lapushin R, Yu S, Jaffe RB, Wiener JR, Erickson JR, Mills GB. Lysophospholipid growth factors in the initiation, progression, metastases, and management of ovarian cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci 905: 188–208, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrugia G, Holm AN, Rich A, Sarr MG, Szurszewski JH, Rae JL. A mechanosensitive calcium channel in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Gastroenterology 117: 900–905, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrugia G, Lei S, Lin X, Miller SM, Nath KA, Ferris CD, Levitt M, Szurszewski JH. A major role for carbon monoxide as an endogenous hyperpolarizing factor in the gastrointestinal tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 8567–8570, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrugia G, Rich A, Rae JL, Sarr MG, Szurszewski JH. Calcium currents in human and canine jejunal circular smooth muscle cells. Gastroenterology 109: 707–717, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frasch SC, Zemski-Berry K, Murphy RC, Borregaard N, Henson PM, Bratton DL. Lysophospholipids of different classes mobilize neutrophil secretory vesicles and induce redundant signaling through G2A. J Immunol 178: 6540–6548, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galli A, DeFelice LJ. Inactivation of L-type Ca channels in embryonic chick ventricle cells: dependence on the cytoskeletal agents colchicine and taxol. Biophys J 67: 2296–2304, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gautier M, Zhang H, Fearon IM. Peroxynitrite formation mediates LPC-induced augmentation of cardiac late sodium currents. J Mol Cell Cardiol 44: 241–251, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamill OP Twenty odd years of stretch-sensitive channels. Pflügers Arch 453: 333–351, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayakawa K, Tatsumi H, Sokabe M. Actin stress fibers transmit and focus force to activate mechanosensitive channels. J Cell Sci 121: 496–503, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holm AN, Rich A, Miller SM, Strege P, Ou Y, Gibbons SJ, Sarr MG, Szurszewski JH, Rae JL, Farrugia G. Sodium current in human jejunal circular smooth muscle cells. Gastroenterology 122: 178–187, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holm AN, Rich A, Sarr MG, Farrugia G. Whole cell current and membrane potential regulation by a human smooth muscle mechanosensitive calcium channel. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 279: G1155–G1161, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Kluppel M, Malysz J, Mikkelsen HB, Bernstein A. W/kit gene required for interstitial cells of Cajal and for intestinal pacemaker activity. Nature 373: 347–349, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kao CY Ionic channel functions in some visceral smooth myocytes. In: Cellular Aspects of Smooth Muscle Function, edited by Kao CY and Carsten ME. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 98–131.

- 21.Kim D A mechanosensitive K+ channel in heart cells. Activation by arachidonic acid. J Gen Physiol 100: 1021–1040, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim I, Gibbons SJ, Lyford GL, Miller SM, Strege PR, Sarr MG, Chatterjee S, Szurszewski JH, Shah VH, Farrugia G. Carbon monoxide activates human intestinal smooth muscle L-type Ca2+ channels through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 288: G7–G14, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundbaek JA, Andersen OS. Lysophospholipids modulate channel function by altering the mechanical properties of lipid bilayers. J Gen Physiol 104: 645–673, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyford GL, Strege PR, Shepard A, Ou Y, Ermilov L, Miller SM, Gibbons SJ, Rae JL, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G. α1C (Cav1.2) L-type calcium channel mediates mechanosensitive calcium regulation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C1001–C1008, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maingret F, Patel AJ, Lesage F, Lazdunski M, Honore E. Lysophospholipids open the two-pore domain mechano-gated K+ channels TREK-1 and TRAAK. J Biol Chem 275: 10128–10133, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinac B Mechanosensitive ion channels: molecules of mechanotransduction. J Cell Sci 117: 2449–2460, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer zu Heringdorf D, Jakobs KH. Lysophospholipid receptors: signalling, pharmacology and regulation by lysophospholipid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta 1768: 923–940, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamura K, Kishimoto T, Ohkawa R, Okubo S, Tozuka M, Yokota H, Ikeda H, Ohshima N, Mizuno K, Yatomi Y. Suppression of lysophosphatidic acid and lysophosphatidylcholine formation in the plasma in vitro: proposal of a plasma sample preparation method for laboratory testing of these lipids. Anal Biochem 367: 20–27, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohata H, Tanaka K, Aizawa H, Ao Y, Iijima T, Momose K. Lysophosphatidic acid sensitises Ca2+ influx through mechanosensitive ion channels in cultured lens epithelial cells. Cell Signalling 9: 609–616, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohata H, Tanaka KI, Maeyama N, Ikeuchi T, Kamada A, Yamamoto M, Momose K. Physiological and pharmacological role of lysophosphatidic acid as modulator in mechanotransduction. Jpn J Pharmacol 87: 171–176, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ou Y, Gibbons SJ, Miller SM, Strege PR, Rich A, Distad MA, Ackerman MJ, Rae JL, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G. SCN5A is expressed in human jejunal circular smooth muscle cells. Neurogastroenterol Motil 14: 477–486, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parrill AL Structural characteristics of lysophosphatidic acid biological targets. Biochem Soc Trans 33: 1366–1369, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel AJ, Lazdunski M, Honore E. Lipid and mechano-gated 2P domain K+ channels. Curr Opin Cell Biol 13: 422–428, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenblat M, Gaidukov L, Khersonsky O, Vaya J, Oren R, Tawfik DS, Aviram M. The catalytic histidine dyad of high-density lipoprotein-associated serum paraoxonase-1 (PON1) is essential for PON1-mediated inhibition of low-density lipoprotein oxidation and stimulation of macrophage cholesterol efflux. J Biol Chem 281: 7657–7665, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sha L, Farrugia G, Harmsen WS, Szurszewski JH. Membrane potential gradient is carbon monoxide-dependent in mouse and human small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 293: G438–G445, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobel BE, Corr PB, Robison AK, Goldstein RA, Witkowski FX, Klein MS. Accumulation of lysophosphoglycerides with arrhythmogenic properties in ischemic myocardium. J Clin Invest 62: 546–553, 1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strege PR, Holm AN, Rich A, Miller SM, Ou Y, Sarr MG, Farrugia G. Cytoskeletal modulation of sodium current in human jejunal circular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C60–C66, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strege PR, Mazzone A, Kraichely RE, Sha L, Holm AN, Ou Y, Lim I, Gibbons SJ, Sarr MG, Farrugia G. Species dependent expression of intestinal smooth muscle mechanosensitive sodium channels. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19: 135–143, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strege PR, Ou Y, Sha L, Rich A, Gibbons SJ, Szurszewski JH, Sarr MG, Farrugia G. Sodium current in human intestinal interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 285: G1111–G1121, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sukharev S, Corey DP. Mechanosensitive channels: multiplicity of families and gating paradigms. Sci STKE 2004: re4, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Summers BA, Overholt JL, Prabhakar NR. Nitric oxide inhibits L-type Ca2+ current in glomus cells of the rabbit carotid body via a cGMP-independent mechanism. J Neurophysiol 81: 1449–1457, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takenouchi T, Sato M, Kitani H. Lysophosphatidylcholine potentiates Ca2+ influx, pore formation and p44/42 MAP kinase phosphorylation mediated by P2X7 receptor activation in mouse microglial cells. J Neurochem 102: 1518–1532, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thuneberg L, Peters S. Toward a concept of stretch-coupling in smooth muscle. I. Anatomy of intestinal segmentation and sleeve contractions. Anat Rec 262: 110–124, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uemura K, Adachi-Akahane S, Shintani-Ishida K, Yoshida K. Carbon monoxide protects cardiomyogenic cells against ischemic death through L-type Ca2+ channel inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 334: 661–668, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Unno T, Komori S, Ohashi H. Microtubule cytoskeleton involvement in muscarinic suppression of voltage-gated calcium channel current in guinea-pig ileal smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol 127: 1703–1711, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang XY, Vannucchi MG, Nieuwmeyer F, Ye J, Faussone-Pellegrini MS, Huizinga JD. Changes in interstitial cells of Cajal at the deep muscular plexus are associated with loss of distention-induced burst-type muscle activity in mice infected by Trichinella spiralis. Am J Pathol 167: 437–453, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward SM, Beckett EA, Wang X, Baker F, Khoyi M, Sanders KM. Interstitial cells of Cajal mediate cholinergic neurotransmission from enteric motor neurons. J Neurosci 20: 1393–1403, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward SM, Burns AJ, Torihashi S, Sanders KM. Mutation of the proto-oncogene c-kit blocks development of interstitial cells and electrical rhythmicity in murine intestine. J Physiol 480: 91–97, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Won KJ, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Interstitial cells of Cajal mediate mechanosensitive responses in the stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 14913–14918, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu SZ, Muraki K, Zeng F, Li J, Sukumar P, Shah S, Dedman AM, Flemming PK, McHugh D, Naylor J, Cheong A, Bateson AN, Munsch CM, Porter KE, Beech DJ. A sphingosine-1-phosphate-activated calcium channel controlling vascular smooth muscle cell motility. Circ Res 98: 1381–1389, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu Y, Xiao YJ, Zhu K, Baudhuin LM, Lu J, Hong G, Kim KS, Cristina KL, Song L, S Williams F, Elson P, Markman M, Belinson J. Unfolding the pathophysiological role of bioactive lysophospholipids. Curr Drug Targets 3: 23–32, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yin Z, Tong Y, Zhu H, Watsky MA. ClC-3 is required for LPA-activated Cl− current activity and fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C535–C542, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshimura N, Seki S, de Groat WC. Nitric oxide modulates Ca2+ channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons innervating rat urinary bladder. J Neurophysiol 86: 304–311, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao Z, Xiao Y, Elson P, Tan H, Plummer SJ, Berk M, Aung PP, Lavery IC, Achkar JP, Li L, Casey G, Xu Y. Plasma lysophosphatidylcholine levels: potential biomarkers for colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 25: 2696–2701, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng M, Uchino T, Kaku T, Kang L, Wang Y, Takebayashi S, Ono K. Lysophosphatidylcholine augments Cav3.2 but not Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel current expressed in HEK-293 cells. Pharmacology 76: 192–200, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu X, Learoyd J, Butt S, Zhu L, Usatyuk PV, Natarajan V, Munoz NM, Leff AR. Regulation of eosinophil adhesion by lysophosphatidylcholine via a non-store-operated Ca2+ channel. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 36: 585–593, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]