Abstract

Water transport across gallbladder epithelium is driven by osmotic gradients generated from active salt absorption and secretion. Aquaporin (AQP) water channels have been proposed to facilitate transepithelial water transport in gallbladder and to modulate bile composition. We found strong AQP1 immunofluorescence at the apical membrane of mouse gallbladder epithelium. Transepithelial osmotic water permeability (Pf) was measured in freshly isolated gallbladder sacs from the kinetics of luminal calcein self-quenching in response to an osmotic gradient. Pf was very high (0.12 cm/s) in gallbladders from wild-type mice, cAMP independent, and independent of osmotic gradient size and direction. Although gallbladders from AQP1 knockout mice had similar size and morphology to those from wild-type mice, their Pf was reduced by ∼10-fold. Apical plasma membrane water permeability was greatly reduced in AQP1-deficient gallbladders, as measured by cytoplasmic calcein quenching in perfluorocarbon-filled, inverted gallbladder sacs. However, neither bile osmolality nor bile salt concentration differed in gallbladders from wild-type vs. AQP1 knockout mice. Our data indicate constitutively high water permeability in mouse gallbladder epithelium involving transcellular water transport through AQP1. The similar bile salt concentration in gallbladders from AQP1 knockout mice argues against a physiologically important role for AQP1 in mouse gallbladder.

Keywords: AQP1, transgenic mice, gastrointestinal system

the mammalian gallbladder functions as a storage compartment for bile produced by hepatobiliary secretion. Cells lining the luminal, bile-facing surface of the gallbladder form a leaky epithelium containing various salt transporters that alter bile composition and respond to hormonal stimuli (7, 9, 21). NaCl and water absorption across the gallbladder epithelium concentrates solutes including bile salts. Inhibition of NaCl absorption by hormones released during digestion, including secretin, serotonin, and vasoactive intestinal peptide, can result in net fluid secretion by the gallbladder epithelium. Net fluid absorption or secretion requires osmotic water transport across the gallbladder epithelium in response to the osmotic driving forces produced by active salt transport.

As a leaky epithelium, water movement across gallbladder epithelium could occur by paracellular and transcellular routes. Although early theories favored paracellular water transport in leaky epithelia, more recent theoretical and experimental evidence favors transcellular water transport (reviewed in Refs. 5 and 29). The expression of aquaporin (AQP) water channels in various leaky epithelia, such as kidney proximal tubule (23), provided further evidence for transcellular osmosis. In gallbladder, immunostaining from several laboratories showed AQP1 expression at cell plasma membranes, and perhaps intracellular vesicles, of gallbladder epithelium from humans and mice (2, 8, 17). It has been proposed, without direct evidence, that AQP1 facilitates osmotic water transport across the gallbladder epithelium and is thus an important determinant of bile composition (2). Involvement of AQP1 in gallstone disease has also been proposed based on indirect evidence showing altered gallbladder AQP1 expression in a mouse model of cholesterol gallstone disease (2).

The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of AQP1 in gallbladder water permeability and its possible involvement in modifying bile composition. We compared gallbladder morphology, AQP1 expression, and water permeability in wild-type and AQP1-deficient mice, as well as bile osmolality and composition. We also tested the hypothesis of cAMP-regulated gallbladder water permeability and AQP1 cellular trafficking. For these studies we developed calcein fluorescence quenching methods to measure transepithelial osmotic water permeability of intact gallbladder sacs and apical plasma membrane water permeability in inverted, perfluorocarbon-filled gallbladder sacs. The principal finding was constitutively high, AQP1-facilitated water permeability across gallbladder epithelium. We also found comparable osmolality and composition in gallbladders from wild-type and AQP1 knockout mice, suggesting that, despite its role in water permeability, gallbladder AQP1 is not involved in physiologically important functions.

METHODS

Mice.

AQP1 null mice in a CD1 genetic background were generated by targeted gene disruption as described (4). Eight- to 10-wk-old weight-matched wild-type and AQP1 null mice were used. Mice were maintained in air-filtered cages and fed normal mouse chow in the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Animal Care facility. All procedures were approved by the UCSF Committee on Animal Research.

Histology and immunofluorescence.

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal Avertin (125 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Following midline abdominal incision gallbladders were removed and fixed for 24 h in 4% paraformaldehyde at 20°C. Tissues were dehydrated with increasing concentrations of ethanol, treated with clearing agent, and embedded in paraffin. Some sections were deparaffinized, and stained by standard procedures with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunofluorescence, sections were blocked with bovine serum albumin (3%), incubated with rabbit anti-AQP1 antibody (1:100, Chemicon, Temecula, CA), and detected by using a fluorescent goat-anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200, Molecular Probes). Stained sections were viewed on a Nikon C1-SHS 90257 fluorescence confocal microscope.

RT-PCR.

Gallbladders were microdissected from wild-type and AQP1 knockout mice after euthanasia. Total RNA was isolated by homogenization in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and mRNA was extracted using the Oligotex mRNA mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was reverse-transcribed from mRNA with oligo(dT) (Super-Script First Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR; Invitrogen), along with a series of other tissues (kidney, testis, liver, and submandibular gland) used as positive controls. After reverse transcription, PCR was carried out using gene-specific primers designed to amplify portions of the coding sequences of each of the nine mouse aquaporins. Fluorescence-based real-time RT-PCR was carried out by use of the LightCycler and with LightCycler FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Primers were as follows: 5′-TGTATGCCTCTGGTCGTACC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CAGGTCCAGACGCAGGATG-3′ (antisense) for β-actin, 5′-CTCCCTAGTCGACAATTCAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACAGTACCAGCTGCAGAGTG-3′ (antisense) for AQP1, and 5′-GTCACAGTGATCGGAGGCCTCAAGAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCAGAATCTTTCCTCTGGACTCAC-3′ (antisense) for AQP8. Results are reported as calibrated ratios, normalized to β-actin as reference gene.

Transepithelial osmotic water permeability.

Transepithelial water permeability was measured from the kinetics of luminal calcein fluorescence self-quenching in response to transepithelial osmotic gradients. Following removal of the gallbladder, the lumen was rinsed with PBS three times and then filled with 15 μl of PBS containing 10 mM calcein. The neck of the gallbladder was tied with 4-0 silk suture to prevent leakage of luminal contents. The sealed gallbladder sac was immobilized in a custom perfusion chamber modified from an open bath slice chamber (RC-26; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) and positioned on the stage of an inverted microscope. Perfusion rate was generally 5 ml/min, giving an exchange time of a few seconds. Calcein fluorescence was visualized by using an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Diaphot, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with stabilized halogen light source, calcein filter set (480-nm excitation, 490-nm dichroic mirror, 535-nm emission filter), photomultiplier detector, and 14-bit analog-to-digital converter. The gallbladder sac was visualized by use of a ×10 air objective lens (Nikon, long working distance, numerical aperture 0.25). Calcein fluorescence was recorded at a rate of 1 Hz for 20–30 min during fluid exchanges.

The transepithelial osmotic water permeability coefficient (Pf) was computed from initial normalized fluorescence (F) slope, d(F/Fo)/dt, following solution exchanges from the equation

|

(1) |

This equation is derived from the defining equation for Pf: Jv = Pf S·vwΔOsm, where Jv is transepithelial volume flow (dV/dt, V is gallbladder luminal volume), S is surface area, vw is partial molar volume of water (18 cm3/mol), and ΔOsm is the transepithelial osmotic gradient. Because calcein remains in the lumen, V/Vo = [calcein]o/[calcein], where the o subscript refers to the initial condition before perfusate exchange, and brackets denote concentration. From measured calcein fluorescence vs. [calcein] (Fig. 2D), the function [calcein]/[calcein]o = f(F/Fo) is deduced, which, together with the V/Vo relation, allows determination of Jv from fluorescence slope d(F/Fo)/dt, giving Eq. 1.

Apical plasma membrane water permeability.

A calcein-quenching method was used in which cytoplasmic calcein fluorescence is quenched by cytoplasmic proteins and consequently sensitive to cell volume (24). Gallbladders were removed from mice and sacs were inverted with a glass tube so that the mucosal surface faced outward. The lumen of the inverted sac was filled with 15 μl of perfluorocarbon (FC-70, 3M Belgium NV), and the sac was closed with suture as above. To stain epithelial cell cytoplasm, the inverted sac was incubated with 5 μM calcein-AM (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) for 30 min at 37°C. After rinsing in PBS (pH 7.4), the inverted sacs were mounted in a custom perfusion chamber (300 μl volume) designed for rapid solution exchange of <250 ms at a 50 ml/min perfusion rate. The time course of calcein fluorescence was measured in response to cell swelling and shrinking produced by exchange of perfusate between PBS and hypertonic PBS (containing 300 mM d-mannitol). Calcein fluorescence was detected using an objective lens (Nikon, ×25, long working distance, numerical aperture 0.35) focused on the apical surface. Apical plasma membrane osmotic water permeability (assuming smooth surface) was computed from t1/2 as described (24), estimating a cell thickness of 20 μm, equivalent to a cell surface-to-volume ratio of 500 cm−1.

Bile osmolality and composition.

Mice were fasted for 8 h but given free access to water. Following anesthesia the gallbladder was visualized and 20–30 μl of luminal fluid was withdrawn using a 50- μl microsyringe. Osmolality was measured by freezing-point osmometry (Micro-osmometer; Precision Systems). Glutathione (GSH) and total bile acid were measured by using commercial colorimetric assay kits per manufacturers' instructions.

RESULTS

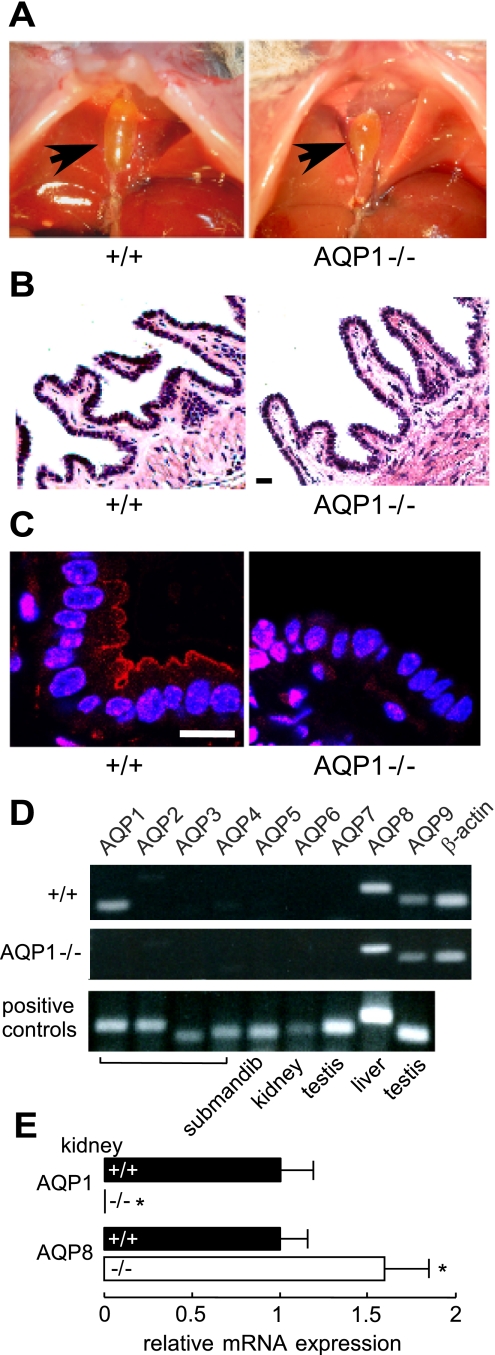

Figure 1A shows bile-containing gallbladders in situ in wild-type and AQP1 null mice at 8 h after fasting from solid food but provided water ad libitum. Gallbladders of wild-type and AQP1 null mice had similar size and gross anatomy. Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed similar histology of gallbladders from wild-type and AQP1 null mice, with comparable epithelial thickness and cell density (Fig. 1B). AQP1 immunofluorescence showed a plasma membrane expression pattern in gallbladders from wild-type mice, with strong fluorescence in epithelial cell apical membranes, with little staining of basolateral membranes or intracellular vesicles (Fig. 1C, left). Similar immunofluorescence was seen in forskolin-treated gallbladders from wild-type mice (not shown). No specific staining was seen in gallbladders from AQP1 null mice (Fig. 1C, right).

Fig. 1.

Gallbladder morphology and aquaporin-1 (AQP1) expression. A: photographs of gallbladders from wild-type and AQP1 null mice taken in situ after 8-h fasting. B: hematoxylin and eosin-stained gallbladder. Scale bar: 50 μm. C: AQP1 immunofluorescence. Scale bar: 20 μm. D: RT-PCR of gallbladder epithelial cell cDNA from wild-type and AQP1 null mice. Representative of data from 3 sets of experiments. Control amplifications done using cDNAs from indicated tissues. Submandib, submandibular gland. E: quantitative real-time RT-PCR of gallbladder epithelial cell cDNA showing relative expression of transcripts encoding AQP1 and AQP8, normalized to β-actin transcript expression (SE, n = 4 gallbladders per genotype). *P < 0.05.

RT-PCR was done to investigate the expression of other AQPs in mouse gallbladder and whether their expression is altered by AQP1 deletion. Figure 1D shows RT-PCR for mouse AQPs 1–9 with gallbladder epithelial cell DNA from wild-type and AQP1 null mice used as template. Expression of transcript encoding AQP1 and AQP8 was consistently seen in gallbladder cDNA from wild-type mice and transcript encoding AQP8 in cDNA from AQP1 null mice. Much lower expression of transcript encoding AQP9 was seen as well. By quantitative RT-PCR, the expression of transcript encoding AQP8 was increased mildly in AQP1 null compared with wild-type gallbladders (Fig. 1E).

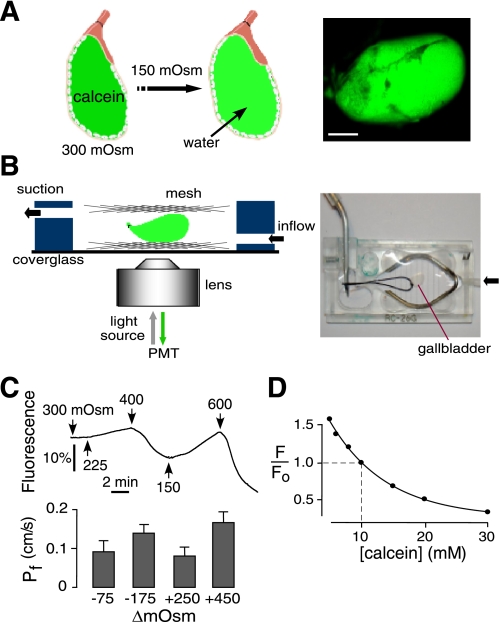

Transepithelial osmotic water permeability was measured in intact gallbladder sacs from the time course of luminal calcein fluorescence in response to changes in perfusate osmolality. Figure 2A (left) diagrams the principle of the method. Gallbladder sacs are washed and filled with an isosmolar buffer containing 10 mM calcein, a polar, membrane-impermeable fluorescent dye. The neck of the gallbladder was tied with suture to maintain a sealed sac. In response to an outwardly directed osmotic gradient water moves from the perfusate into the gallbladder lumen, resulting in calcein dilution. At 10 mM, calcein fluorescence is strongly self-quenched, such that calcein dilution following water influx reduces calcein self-quenching and so increases fluorescence. The kinetics of calcein fluorescence change provided a quantitative measure of transepithelial osmotic water permeability. This method is suitable to study inward or outward water transport with different osmotic gradients because calcein fluorescence quenching is reversible, essentially instantaneous, and occurs over a wide range of calcein concentrations. Figure 2A, right shows a photograph of a calcein-filled gallbladder sac. The bright calcein fluorescence and consequent excellent signal-to-noise ratio allows detection of small changes in calcein concentration that occur in intact gallbladder sacs over minutes during osmosis.

Fig. 2.

Transepithelial osmotic water permeability measured by luminal calcein self-quenching. A: principle of the measurement method, showing dilution of luminal calcein in response to osmotically driven water influx into the lumen of a calcein-filled gallbladder sac (left). Calcein dilution results in less fluorescence self-quenching and consequent increased fluorescence. Right: photograph of calcein-filled gallbladder sac. Scale bar: 1.5 mm. B: perfusion chamber for water permeability measurements. Left: schematic showing gallbladder sac immobilized by a nylon mesh. Right: photograph of perfusion chamber. C: transepithelial osmotic water permeability in gallbladder from wild-type mouse. Top: representative calcein fluorescence kinetics shown in response to indicated perfusate osmolalities. Bottom: summary of osmotic water permeability coefficients [mean ± SE, n = 5, transepithelial osmotic water permeability (Pf) at 23°C] measured as function of osmotic gradient (ΔmOsm). Differences are not significant. D: calcein fluorescence self-quenching shown as calcein fluorescence measured as a function of its concentration in physiological saline. Measurements were made by microfiberoptic fluorescence to avoid inner filter effect.

Figure 2B, left shows a schematic of the perfusion chamber in which the gallbladder sac is immobilized by a nylon mesh and visualized by epifluorescence microscopy. A photograph of the perfusion chamber with immobilized gallbladder sac is shown in Fig. 2B, right. Fluorescence measurements were made during continuous perfusion with solution exchange accomplished using electronic valves.

Figure 2C, top shows a representative time course of calcein fluorescence in a gallbladder sac from a wild-type mouse subjected to different osmotic gradients. The gallbladder lumen contained 10 mM calcein in a pH 7.4 buffered saline solution of initial osmolality 300 mosmol/kg. Fluorescence increased following perfusion with hypoosmolar solutions and decreased with hyperosmolar solutions, as expected. Figure 2D shows calcein fluorescence as a function of its concentration, showing strong self-quenching at 10 mM. This measured fluorescence-vs.-[calcein] relation is used for computation of Pf from fluorescence data (see methods). From the kinetic data, the calcein self-quenching relation, and gallbladder size, Pf values were computed, as summarized in Fig. 2C, bottom. Pf was very high, averaging ∼0.12 cm/s at 23°C, and approximately independent of osmotic gradient size and direction.

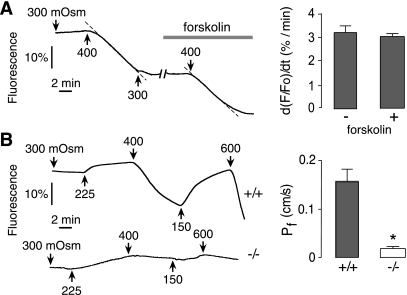

To investigate whether transepithelial osmotic water permeability is stimulated by cAMP elevation, as has been reported in intrahepatic biliary epithelium (15), luminal calcein fluorescence was measured in gallbladders before vs. after forskolin incubation. Figure 3A, left shows a similar slope of the reduced fluorescence (dashed lines) following exchange from 300 to 400 mosmol/kg perfusate before and after forskolin addition. Figure 3A, right shows no significant effect of forskolin on transepithelial water permeability.

Fig. 3.

Greatly reduced water permeability in gallbladder in AQP1 knockout mice. A: calcein fluorescence for gallbladder from wild-type mouse subjected to a 100 mosmol/kg transepithelial osmotic gradient, measured before and after 10 min incubation with 10 μM forskolin (left) and summary of initial slopes following osmotic challenge (SE, n = 5) (right). Difference is not significant. B: calcein fluorescence for gallbladders from wild-type and AQP1 null mice shown for different osmotic gradients (left) and summary of deduced Pf (averaged in each gallbladder) (SE, n = 5) (right). *P < 0.001.

Water permeability was compared in gallbladders from wild-type and AQP1 null mice. Figure 3B, left shows that changes in calcein fluorescence in response to osmotic gradients were remarkably slower in gallbladders from AQP1 null mice. The deduced Pf was ∼10-fold lower in AQP1 null mice than in wild-type mice (Fig. 3B, right), indicating that AQP1 is the principal water channel in gallbladder epithelium and that transepithelial water movement occurs primarily by a transcellular route.

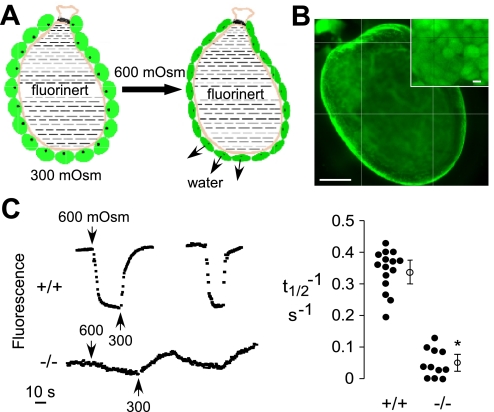

The Pf measurements in intact gallbladder sacs and the strong AQP1 immunofluorescence at the luminal surface of the gallbladder epithelium predict very high osmotic water permeability across the apical plasma membrane of gallbladder epithelial cells. We devised a method to measure apical membrane water permeability in intact gallbladders, in which the gallbladder is physically inverted (lumen surface facing outward) and the basal surface is bathed in perfluorocarbon, an inert, nonviscous, nonaqueous fluid (Fig. 4A). Cytoplasm in gallbladder epithelial cells was stained with calcein by incubation of the inverted gallbladder sac with the cell-permeable/trappable acetoxymethylester form of calcein. Figure 4B shows brightly calcein-stained gallbladder epithelial cells in an inverted sac, with individual cells seen in the en-face micrograph (inset). Rapid changes in perfusate osmolality drive water movement across the apical plasma membrane, resulting in changes in cell volume, producing instantaneous changes in cytoplasmic calcein fluorescence. In this measurement calcein fluorescence is quenched by cytoplasmic proteins (24), such that reduced cell volume concentrates the cytoplasm and hence decreases calcein fluorescence. Figure 4C, left shows representative cytoplasmic calcein fluorescence data in which changes in perfusate osmolality between 300 and 600 mosmol/kg produce reversible changes in calcein fluorescence. The kinetics of the fluorescence changes was remarkably slowed in gallbladders in AQP1 null mice. Reciprocal half-times for osmotic equilibration are summarized in Fig. 4C, right. Estimating a cell thickness of 20 μm, the rapid equilibration time for gallbladder epithelial cells in wild-type mice gives an apparent apical membrane osmotic water permeability of ∼0.3 cm/s, computed for a smooth (nonconvoluted) apical surface (see discussion).

Fig. 4.

Apical plasma membrane water permeability in gallbladder epithelial cells. A: schematic of measurement method showing cytoplasmic calcein staining of gallbladder epithelial cells in an inverted gallbladder sac (apical surface facing outward), with the lumen filled with perfluorocarbon. Increased perfusate osmolality reduces gallbladder cell volume, resulting in a quenching of cytoplasmic calcein fluorescence. B: fluorescence micrograph showing calcein-stained cytoplasm of gallbladder epithelial cells. Scale bar: 1 mm. Inset: en-face magnified view of stained gallbladder cells. Scale bar: 10 μm. C: time course of cytoplasmic calcein fluorescence in response to changes in perfusate osmolality between 300 and 600 mosmol/kg for gallbladders (left) from 2 wild-type mice (top) and 1 AQP1 null mouse (bottom) and deduced reciprocal half-times (t1/2−1) for osmotic equilibration (right). •, Individual measurements; ○, mean and SE. *P < 0.001.

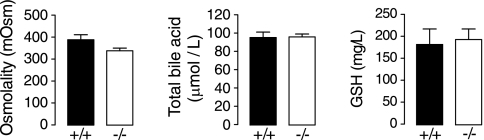

Last, to investigate the potential physiological significance of high, AQP1-dependent water permeability in mouse gallbladder, we analyzed gallbladder fluid contents for osmolality and the concentrations of GSH and total bile acid. Gallbladder luminal fluid was removed in situ from wild-type and AQP1 null mice at 8 h after fasting, which was done to reduce prosecretory hormonal effects. Figure 5 shows no significant effects of AQP1 deficiency in osmolality or in GSH or bile salt concentrations.

Fig. 5.

AQP1 deficiency does not alter bile osmolality or composition. Gallbladder contents were removed from mice after 8 h of fasting and were assayed for osmolality, total bile acid concentration, and GSH concentration (SE, n = 5 mice per genotype). Differences are not significant.

DISCUSSION

We found exceptionally high transepithelial osmotic water permeability in intact mouse gallbladder resulting from transcellular water movement through plasma membrane AQP1 water channels. The high, AQP1-facilitated water permeability was constitutive rather than cAMP-regulated, as was reported for intrahepatic biliary epithelium (15) and speculated for gallbladder epithelium (2). Though AQP1 deletion in mice greatly reduced gallbladder water permeability, it did not affect gallbladder morphology or bile osmolality or composition, providing evidence against a physiologically important role for gallbladder AQP1. Although there is evidence that another AQP, AQP8, is also expressed in the apical membrane of gallbladder epithelium (2), the greatly reduced osmotic water permeability in AQP1-deficient gallbladder indicates that AQP1 provides the principal route for water transport across the apical membrane of gallbladder epithelium. Also, AQP8 knockout mice do not manifest defective hepatobiliary function (37). The low gallbladder water permeability in AQP1 null mice indicates that despite the small increase in AQP8 transcript expression found in AQP1 null gallbladders, AQP8 does not functionally substitute for AQP1 in the AQP1 null gallbladders. The pathway for water movement across the basolateral membrane of gallbladder might involve AQP(s) and/or the lipid portion of the membrane. Of note, the highly convoluted basolateral membrane of gallbladder epithelium, which has a “folding factor” of >25 (30), could considerably enhance basolateral water permeability even without AQPs.

The small size and fragility of the mouse gallbladder, and its high water permeability, required the development of novel methodology to measure transepithelial and apical membrane water permeability. We developed a fluorescence method to measure water permeability in intact gallbladder sacs based on calcein self-quenching, in which the fluorescence quantum yield of calcein is reduced instantaneously as its concentration increases. Being membrane impermeant over the time course of the measurements, luminal calcein concentration changes reciprocally with osmotically induced changes in gallbladder luminal volume. The calcein quenching method is technically simple and does not require direct invasion of gallbladder cells. Older methods applied to rabbit and Necturus gallbladder used trimethylamine-sensitive microelectrodes to puncture gallbladder cells (4) or challenging imaging methods to deduce cell volume changes (19). Furthermore, the small size of the mouse gallbladder and the continuous external perfusion minimized unstirred layer effects, which allowed measurement of the high water permeability of gallbladder sacs from wild-type mice. Transepithelial osmotic water permeability was ∼0.12 cm/s in intact gallbladder sacs from wild-type mice. This value is approximately twofold higher than transepithelial, osmotically driven Pf reported in rabbit and Necturus gallbladder (4, 19, 31, 32), which may be related to higher AQP1 density in mouse gallbladder and/or to underestimates in the older work because of unstirred layer effects. The much reduced water permeability in AQP1-deficient mouse gallbladder implicates AQP1 as the major water-transporting pathway. The transepithelial Pf of ∼0.12 in mouse gallbladder is among the highest Pf values reported in mammalian epithelia, which includes 0.15 cm/s in kidney proximal tubule (23) and 0.26 cm/s in kidney thin descending limb of Henle (3).

Osmotic water permeability of the apical plasma membrane of gallbladder epithelial cells was measured in inverted gallbladder sacs in which the apical surface faced outward and the inward-facing basal surface was covered with an inert perfluorocarbon to minimize water movement across the basal membrane. Gallbladder epithelial cell volume was measured by quenching of cytoplasmic calcein, in which cytoplasmic proteins, rather than calcein itself, quenches fluorescence. The cytoplasmic calcein fluorescence quenching method was developed for measurement of plasma membrane water permeability in primary glial cell cultures (24) and subsequently applied to various cell culture (36) and freshly isolated cell systems (22). The high apical membrane water permeability of gallbladder epithelium and consequent rapid cell volume equilibration following an osmotic gradient required very fast perfusion and a low-volume chamber design. The deduced apical membrane Pf of gallbladder from wild-type mice was ∼0.3 cm/s, greater than the transepithelial Pf of ∼0.12, as would be anticipated. Since the apical membrane of gallbladder epithelium has been estimated to have a convolution factor of ∼8, the intrinsic apical membrane water permeability would be reduced approximately eightfold, 0.04 cm/s, which is still quite high compared with other cell types considered to be highly water permeable, including 0.02 cm/s in erythrocytes and in kidney proximal tubule apical membrane, 0.05 in astrocytes, and 0.07 cm/s in type I alveolar epithelial cells (6, 24). For a plasma membrane Pf of 0.04 cm/s and the AQP1 (monomer) single-channel water permeability of 10−13 cm3/s, we estimate ∼4,000 AQP1 monomers per square micrometer of cell plasma membrane. This very high density suggests that AQP1 constitutes ∼20% of apical plasma protein in gallbladder epithelial cells.

The ∼10-fold reduced water permeability in AQP1-deficient gallbladders indicates that AQP1 provides the principal route for osmotic water transport across the gallbladder epithelium and that most water moves by a transcellular rather than a paracellular pathway. A primarily transcellular route for osmotic water movement is consistent with theoretical predictions based on the small size of the paracellular pathway in leaky epithelia (5, 29). The finding of AQP1-dependent transcellular osmosis in gallbladder agrees with experimental data in another leaky epithelium, the kidney proximal tubule, where AQP1 knockout reduced transepithelial water permeability by ∼90% (23). The paradigm of transcellular water transport in epithelia is likely to be of general relevance in mammalian physiology.

The similar bile osmolality and bile salt concentration in gallbladders from wild-type and AQP1 knockout mice do not support a physiologically important role for AQP1 expression in gallbladder or for very high gallbladder water permeability. Further evidence supporting the lack of involvement of AQP1 in gallbladder physiology is the normal phenotype of adult AQP1 null mice with regard to dietary fat processing (12) and the lack of overt gastrointestinal problems in rare humans lacking AQP1 (20). There are multiple examples where epithelial aquaporin deletion greatly reduces water permeability without physiological impact, including AQP1 and AQP5 in alveolar epithelium (1, 11), AQP3 and AQP4 in airway epithelium (25), AQP5 in sweat gland (27), AQP1 in peritoneum (35) and pleura (26), and multiple AQPs in colon (34) and lacrimal gland (16). The common feature in these examples is that rates of transepithelial fluid transport are much lower than those in tissues where AQPs are of physiological importance such as kidney tubules (33), salivary gland (10, 13), airway submucosal gland (28), ciliary epithelium (14), and choroid plexus (18).

In conclusion, our results provide evidence for high, AQP1-facilitated osmotic water transport across mouse gallbladder epithelium. However, as found in various other epithelia, the presence of AQPs and high transepithelial water permeability does not ensure their involvement in physiologically important functions.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (no. 30325011) and National Natural Science Fund (nos. 30570864 and 30670477) of China, National Basic Research Program of China (973) (no. 2009CB521908) (T. Ma), and grants EY-13574, EB-00415, DK-35124, HL-59198, DK-72517 and HL-73856 from the National Institutes of Health (A. S. Verkman).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bai C, Fukuda N, Song Y, Ma T, Matthay MA, Verkman AS. Lung fluid transport in aquaporin-1 and aquaporin-4 knockout mice. J Clin Invest 103: 555–561, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calamita G, Ferri D, Bazzini C, Mazzone A, Bottà G, Liquori GE, Paulmichl M, Portincasa P, Meyer G, Svelto M. Expression and subcellular localization of the AQP8 and AQP1 water channels in the mouse gall-bladder epithelium. Biol Cell 97: 415–423, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou CL, Knepper MA, Hoek AN, Brown D, Yang B, Ma T, Verkman AS. Reduced water permeability and altered ultrastructure in thin descending limb of Henle in aquaporin-1 null mice. J Clin Invest 103: 491–496, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cotton CU, Weinstein AM, Reuss L. Osmotic water permeability of Necturus gallbladder epithelium. J Gen Physiol 93: 649–679, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diamond JM Osmotic water flow in leaky epithelia. J Membr Biol 51: 195–216, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobbs L, Gonzalez R, Matthay MA, Carter EP, Allen L, Verkman AS. Highly water-permeable type I alveolar epithelial cells confer high water permeability between the airspace and vasculature in rat lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 2991–2996, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frizzell RA, Heintze K. Transport functions of the gallbladder. Int Rev Physiol 21: 221–247, 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasegawa H, Lian SC, Finkbeiner WF, Verkman AS. Extrarenal tissue distribution of CHIP28 water channels by in situ hybridization and antibody staining. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 266: C893–C903, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Igimi H, Yamamoto F, Lee SP. Gallbladder mucosal function: studies in absorption and secretion in humans and in dog gallbladder epithelium. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 263: G69–G74, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krane CM, Melvin JE, Nguyen HV, Richardson L, Towne JE, Doetschman T, Menon AG. Salivary acinar cells from aquaporin 5-deficient mice have decreased membrane water permeability and altered cell volume regulation. J Biol Chem 27: 23413–23420, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma T, Fukuda N, Song Y, Matthay MA, Verkman AS. Lung fluid transport in aquaporin-5 knockout mice. J Clin Invest 105: 93–100, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma T, Jayaraman S, Wang KS, Song Y, Yang B, Li J, Bastidas JA, Verkman AS. Defective dietary fat processing in transgenic mice lacking aquaporin-1 water channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280: C126–C134, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma T, Song Y, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS. Defective secretion of saliva in transgenic mice lacking aquaporin-5 water channels. J Biol Chem 274: 20071–20074, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma T, Yang B, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS. Severely impaired urinary concentrating ability in transgenic mice lacking aquaporin-1 water channels. J Biol Chem 273, 4296–4299, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Marinelli RA, Pham L, Agre P, LaRusso NF. Secretin promotes osmotic water transport in rat cholangiocytes by increasing aquaporin-1 water channels in plasma membrane. Evidence for a secretin-induced vesicular translocation of aquaporin-1. J Biol Chem 272: 12984–12988, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore M, Ma T, Yang B, Verkman AS. Tear secretion by lacrimal glands in transgenic mice lacking water channels AQP1, AQP3, AQP4 and AQP5. Exp Eye Res 70: 557–562, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen S, Smith BL, Christensen EI, Agre P. Distribution of the aquaporin CHIP in secretory and resorptive epithelia and capillary endothelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 7275–7279, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oshio K, Watanabe H, Song Y, Verkman AS, Manley GT. Reduced cerebrospinal fluid production and intracranial pressure in mice lacking choroid plexus water channel aquaporin-1. FASEB J 19: 76–78, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persson BE, Spring KR. Gallbladder epithelial cell hydraulic water permeability and volume regulation. J Gen Physiol 79: 481–505, 1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preston GM, Smith BL, Zeidel ML, Moulds JJ, Agre P. Mutations in aquaporin-1 in phenotypically normal humans without functional CHIP water channels. Science 265: 1585–1587, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reuss L, Segal Y, Altenberg G. Regulation of ion transport across gallbladder epithelium. Annu Rev Physiol 53: 361–373, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiz-Ederra J, Zhang H, Verkman AS. Evidence against functional interaction between aquaporin-4 water channels and Kir4.1 K+ channels in retinal Müller cells. J Biol Chem 282: 21866–21872, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnermann J, Chou CL, Ma T, Traynor T, Knepper MA, Verkman AS. Defective proximal tubular fluid reabsorption in transgenic aquaporin-1 null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 9660–9664, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solenov E, Watanabe H, Manley GT, Verkman AS. Sevenfold-reduced osmotic water permeability in primary astrocyte cultures from AQP-4-deficient mice, measured by a fluorescence quenching method. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C426–C432, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song Y, Ma T, Matthay MA, Verkman AS. Role of aquaporin-4 in airspace-to-capillary water permeability in intact mouse lung measured by a novel gravimetric method. J Gen Physiol 115: 17–27, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song Y, Yang B, Matthay MA, Ma T, Verkman AS. Role of aquaporin water channels in pleural fluid dynamics. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1744–C1750, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song Y, Sonawane N, Verkman AS. Localization of aquaporin-5 in sweat glands and functional analysis using knockout mice. J Physiol 541: 561–568, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song Y, Verkman AS. Aquaporin-5 dependent fluid secretion in airway submucosal glands. J Biol Chem 276: 41288–41292, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spring KR Routes and mechanism of fluid transport by epithelia. Annu Rev Physiol 60: 105–119, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki K, Kottra G, Kampmann L, Fromter E. Square wave pulse analysis of cellular and paracellular conductance pathways in Necturus gallbladder epithelium. Pflügers Arch 394: 302–312, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Os CH, Slegers JF. Path of osmotic water flow through rabbit gall bladder epithelium. Biochim Biophys Acta 291: 197–207, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Os CH, Wiedner G, Wright EM. Volume flows across gallbladder epithelium induced by small hydrostatic and osmotic gradients. J Membr Biol 49: 1–20, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verkman AS Dissecting the role of aquaporins in renal pathophysiology using transgenic mice. Semin Nephrol 28: 217–226, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verkman AS, Thiagarajah JR. Physiology of water transport in the gastrointestinal tract. In: Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract (vol. 4), edited by Johnson LR, Barrett K, Ghishan F, Manchant J, Said H, Wood J. New York: Academic, 2006, p. 1827–1845. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang B, Folkesson HG, Yang J, Matthay MA, Ma T, Verkman AS. Reduced osmotic water permeability of the peritoneal barrier in aquaporin-1 knockout mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 276: C76–C81, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang B, Zhang H, Verkman AS. Lack of aquaporin-4 water transport inhibition by antiepileptics and arylsulfonamides. Bioorg Med Chem 16: 7489–7493, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang B, Song Y, Zhao D, Verkman AS. Phenotype analysis of aquaporin-8 null mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C1161–C1170, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang D, Vetrivel L, Verkman AS. Aquaporin deletion in mice reduces intraocular pressure and aqueous fluid production. J Gen Physiol 119: 561–569, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]