Abstract

Pathological cardiac hypertrophy, induced by various etiologies such as high blood pressure and aortic stenosis, develops in response to increased afterload and represents a common intermediary in the development of heart failure. Understandably then, the reversal of pathological cardiac hypertrophy is associated with a significant reduction in cardiovascular event risk and represents an important, yet underdeveloped, target of therapeutic research. Recently, we determined that muscle ring finger-1 (MuRF1), a muscle-specific protein, inhibits the development of experimentally induced pathological; cardiac hypertrophy. We now demonstrate that therapeutic cardiac atrophy induced in patients after left ventricular assist device placement is associated with an increase in cardiac MuRF1 expression. This prompted us to investigate the role of MuRF1 in two independent mouse models of cardiac atrophy: 1) cardiac hypertrophy regression after reversal of transaortic constriction (TAC) reversal and 2) dexamethasone-induced atrophy. Using echocardiographic, histological, and gene expression analyses, we found that upon TAC release, cardiac mass and cardiomyocyte cross-sectional areas in MuRF1−/− mice decreased ∼70% less than in wild type mice in the 4 wk after release. This was in striking contrast to wild-type mice, who returned to baseline cardiac mass and cardiomyocyte size within 4 days of TAC release. Despite these differences in atrophic remodeling, the transcriptional activation of cardiac hypertrophy measured by β-myosin heavy chain, smooth muscle actin, and brain natriuretic peptide was attenuated similarly in both MuRF1−/− and wild-type hearts after TAC release. In the second model, MuRF1−/− mice also displayed resistance to dexamethasone-induced cardiac atrophy, as determined by echocardiographic analysis. This study demonstrates, for the first time, that MuRF1 is essential for cardiac atrophy in vivo, both in the setting of therapeutic regression of cardiac hypertrophy and dexamethasone-induced atrophy.

Keywords: ubiquitin ligase, cardiac hypertrophy, cardiac atrophy, left ventricular assist device

pathological cardiac hypertrophy develops in response to increases in afterload and represents a common intermediary in the development of heart failure, a leading cause of mortality in the United States. Left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy is an independent risk factor for several adverse outcomes, including cardiac mortality, arrhythmias, and myocardial infarction (18, 25, 28, 29). Results from numerous studies have suggested that reducing heart mass in patients with pathological cardiac hypertrophy may reduce morbidity and mortality and improves patient outcomes (6, 10, 26, 35, 36, 44, 45). However, the only treatments currently proven to reverse both structural and functional cardiac abnormalities associated with pathological cardiac hypertrophy are antihypertensive therapies and aortic valve replacement (for aortic stenosis), both of which have a limited success rate (14, 39). Understanding the underlying processes regulating the plasticity of the heart will allow us to identify specific pathways against which to target new therapies and may improve the long-term outcomes of patients with pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

Muscle ring finger (MuRF) family proteins are striated muscle-specific proteins involved in cardiomyocyte development and the regulation of muscle mass (3, 32). MuRF1 localizes specifically to the M line, a central structure of the sarcomere thick filament that has recently been recognized as a center of mechanical sensing (21). The ring finger domain of MuRF1 has ubiquitin ligase capabilities (34), targeting sarcomeric proteins such as troponin I and β-/slow myosin heavy chain (MHC) for degradation (13, 24). This degradation occurs through the coordinated placement of polyubiquitin chains on recognized substrates, which are subsequently degraded by the proteasome (50). MuRF1 also interacts with and inhibits serum response factor (SRF) activity, a transcription factor critical to the development of cardiac hypertrophy (49). MuRF1's localization in the sarcomere places it in a unique position to both recognize the mechanical stresses that induce cardiac hypertrophy and regulate its subsequent development by controlling the degradation of targeted sarcomeric proteins. Indeed, results from studies using animal models where the expression of MuRF1 has been altered have implicated MuRF1 in the regulation of the development of cardiac hypertrophy: increasing MuRF1 in cardiomyocytes inhibits the development of hypertrophy (2), whereas the complete lack of MuRF1 results in the development of an exaggerated cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload (49).

The present study was prompted by our observation that human cardiac tissue samples obtained from patients after placement of a LV assist device (LVAD) expressed significantly higher levels of MuRF1 protein than samples taken before the device was implanted. The unloading of the heart by a LVAD device leads to a decrease in the workload of the failing heart and a decrease in LV mass. This form of cardiac atrophy is beneficial to the patient as it decreases the stress on the heart. Although previous studies have identified that MuRF1 is essential for the inhibition of the development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy, there is no evidence linking MuRF1 to the reversal of hypertrophy (i.e., cardiac atrophy). In this report, we used two independent models to demonstrate that MuRF1 is a necessary and significant mediator in the regulation of cardiac atrophy in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The MuRF1−/− mice used in these experiments have previously been described (3, 49).

Human cardiac LVAD samples.

MuRF1 protein levels were determined from heart samples from patients undergoing cardiac unloading by the placement of a LVAD. Heart samples were collected from patients with end-stage ischemic heart disease who received a LVAD for decompensated heart failure as a bridge to transplantation as previously described (40, 53). During the placement of the LVAD, a core of tissue is removed to prepare the LV for LVAD inflow. This specimen was collected at the time of LVAD placement (pre-LVAD sample), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. When patients returned for a heart transplant, ventricular samples were excised just adjacent to the LVAD placement site (post-LVAD sample), snap frozen, and stored at −80°C. Use of the human tissue used in this study was approved by the University of North Carolina Institution Review Board (no. 03-1359).

Mouse cardiac hypertrophy reversal.

Twelve to fifteen-week-old MuRF1−/− and wild-type (WT) mice were subjected to the reversible (slipknot) transaortic constriction (TAC) procedure recently described by our laboratory (42). All experiments used ∼50% male and 50% female MuRF1−/− mice and WT littermate controls. All animal protocols were reviewed by the University of North Carolina Institutional Animal Care Advisory Committee and were in compliance with the rules governing animal use published by the National Institutes of Health.

Dexamethasone model of cardiac atrophy.

MuRF1−/− and WT littermates were maintained on a standard diet with unlimited access to water. Dexamethasone (5 mg·kg−1·day−1) or saline vehicle was given by a daily subcutaneous injection for 2 wk as previously described (1, 16). In additional experiments, dexamethasone (1 mg·kg−1·day−1) or DMSO vehicle was continuously infused by a dorsally implanted osmotic minipump (model 2002, Alzet, Palo Alto, CA) for 2 wk. Echocardiography was performed at baseline and after 2 wk of dexamethasone treatment.

Echocardiography.

Echocardiography on mice was performed on a VisualSonics Vevo 660 ultrasound biomicroscopy system as previously described (49).

Hemodynamic assessment of aorta flow.

To assess the aortic constriction after TAC and TAC reversal, right and left carotid artery flow were assessed using a 20-MHz probe driven by a high-frequency pulsed Doppler signal processing workstation (Induc Instruments, Houston, TX) as previously described (42).

Total RNA isolation/real-time PCR determination of mRNA expression.

Total RNA was isolated from cardiac ventricular tissue as previously described (49). mRNA expression was determined using a two-step reaction. cDNA was made using a High Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR products were amplified on an ABI Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System using cDNA and either 1) the TaqMan probe set in TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix or 2) unlabeled primers in Power CYBR Green Master Mix. The TaqMan probes used in these experiments included brain natriuretic peptide (BNP; Mm00435304_g1), smooth muscle α-actin (Mm00808218_g1), β-MHC (Mm00600555_m1), MuRF1 (Mm01188690_m1), MuRF2 (Mm01292963_g1), atrogin-1/ muscle atrophy F box/F box only protein 32 (Mm00499518_m1), and 18S (Hs99999901_s1) (Applied Biosystems). The unlabeled primers for mouse tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1, TIMP-2, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, pro-collagen type I (ColI), pro-collagen type III (ColIII), laminin B (Lamb), and GAPDH were as previously published (43). Samples were run in triplicate, and relative mRNA expression was determined using 18S (TaqMan Probes) or GAPDH (unlabeled primers) as internal endogenous controls.

Histology and lectin staining.

Hearts were perfused, processed for histology, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, trichrome, or Triticum vulgaris lectin TRITC conjugate as previously described (49). Myocyte area was determined using NIH ImageJ (version 1.38X) based on photomicrographs of a standard graticle ruler.

Western immunoblots.

Human ventricular (50 μg) samples were prepared in denaturing sample loading buffer, separated by 8% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C in 5% milk and Tris-buffered saline-Tween with polyclonal goat anti-MuRF1 antibody (NB100-2406, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO). The membrane was washed, incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-goat antibody (sc-2768, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and washed again. The HRP signal was then detected using the ECL Plus Western Blotting system (RPN2132, GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis.

One-way ANOVA or Student's t-test was performed using Sigma Stat 3.5 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA) and basic statistics on Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft, Seattle, WA). Results are expressed as means ± SE, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Cardiac MuRF1 increases after cardiac unloading.

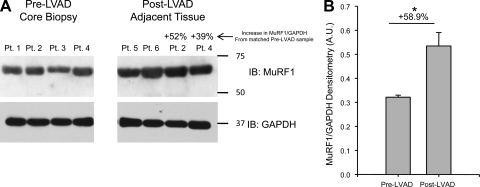

The placement of a LVAD in patients waiting for a heart transplant helps improve cardiac output by taking over the pumping of blood, effectively unloading the work the heart has to do. A number of studies have reported that LVAD-induced unloading results in beneficial cardiac atrophy, which is evidenced by a reduction in LV mass (4, 31, 40, 53). In this study, we collected samples from six patients before and after the placement of a LVAD, including two patients with matched consecutive samples (Fig. 1A). Post-LVAD levels of cardiac MuRF1 protein were significantly elevated (∼60%) compared with MuRF1 protein levels found in samples taken pre-LVAD (Fig. 1B). In the two matched samples, post-LVAD cardiac MuRF1 levels increased 52% and 39% from pre-LVAD levels taken from adjacent tissue (Fig. 1A). This suggested that MuRF1 was intrinsically involved in the cardiac atrophy resulting from LVAD-induced cardiac unloading. This result led us to propose the hypothesis that MuRF1 is involved in the regulation of cardiac atrophy. To test this hypothesis, we challenged MuRF1−/− mice to two independent models of cardiac atrophy: 1) cardiac hypertrophy regression after reversal of TAC and 2) dexamethasone-induced atrophy.

Fig. 1.

Expression of cardiac muscle ring finger-1 (MuRF1) after unloading of human and mouse hearts. A: cardiac MuRF1 protein levels increased after mechanical unloading with a left ventricular (LV) assist device (LVAD). n = 6 (with 2 of the 4 samples matched), all run on the same gel. LV mass determination from an echocardiography M-mode analysis taken from patient 2 and patient 4 demonstrated a change of 56.3 g (226.8 g pre-LVAD and 170.5 g post-LVAD) and 26.4 g (187.3 g pre-LVAD and 160.9 g post-LVAD), respectively. B: densitometric analysis of MuRF1 immunoblots (IB). Student's t-test was performed to compare patient groups. *P = 0.009.

MuRF1 is necessary for the reversal of pathological cardiac hypertrophy in vivo.

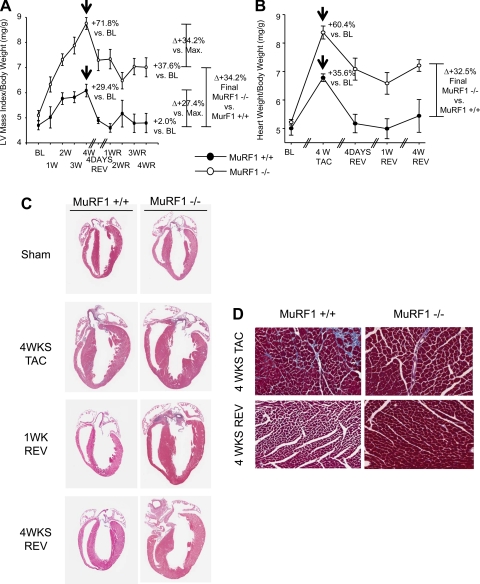

We (49) have recently identified that hearts taken from adult MuRF1−/− mice are indistinguishable from WT littermate controls. We (49) also discovered that MuRF1−/− mice develop an exaggerated cardiac hypertrophy after the induction of pressure overload by TAC, suggesting that MuRF1 antagonizes the development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. In the present study, we investigated the role that MuRF1 plays in the cardiac atrophy that is seen with the reversal of experimentally induced pathological cardiac hypertrophy. MuRF1−/− and WT control mice underwent reversible TAC, which was released 4 wk later. The ability of MuRF1−/− mice to decrease cardiac mass after TAC release was then determined by echocardiography, histology, and gene expression analyses. By calculating the LV mass index by echocardiography, we discovered that 4 wk after TAC, the increase in cardiac mass in MuRF1−/− mice was ∼2.4-fold higher than the increase seen in WT mice (71.8% vs. 29.4% from baseline, respectively; Fig. 2A). After TAC release [the success of which was confirmed by Doppler flow experiments (Table 1) and histological analysis (Supplemental Fig. 1)],1 the LV mass index of WT mice regressed to baseline within 4 days. A significant decrease in cardiac mass was also seen in MuRF1−/− mice 4 days after TAC release; however, this rate of cardiac atrophy was not maintained. Four weeks after TAC release, the cardiac mass of MuRF1−/− mice remained 37.6% higher than the pre-TAC baseline. The inability of MuRF1−/− mice to fully reverse the TAC-induced hypertrophy was confirmed by the determination of the actual whole heart mass in representative mice (Fig. 2B). As with the LV mass index, MuRF1−/− hearts exhibited an exaggerated total cardiac mass after 4 wk of TAC (60.4%) compared with WT mice (35.6%; Fig. 2B). However, whereas the total cardiac mass returned to baseline levels in WT mice by 4 days after TAC release, MuRF1−/− mice decreased their mass by only ∼50% (60.4% vs. 35.7%) and remained at 32.5% greater mass than WT hearts after 4 wk of TAC release (Fig. 2B). This response to TAC and TAC release was also seen by histological analyses (Fig. 2, C and D).

Fig. 2.

Histological and mass analysis of MuRF1−/− and wild-type (WT) mice after 4 wk of transaortic constriction (TAC) and 4 wk after TAC reversal (Rev/R). A: echocardiographic determination of LV mass. BL, baseline; Max, maximum. n = 3–25 mice/group. B: actual determination of heart weight/body weight. n = 3–7 mice/group. Arrows indicate the reversal of TAC. C and D: representative histological cross sections at low power (C; hematoxylin and eosin stained; magnification: ×0.7) and high power (D; Masson's trichrome stained; magnification: ×20). In C, the histological analysis was representative of 2–3 individual mice/group.

Table 1.

Physiological assessment of aortic constriction at baseline and after transaortic constriction reversal by right and left carotid blood flow determination by pulse-Doppler analysis

| Peak Right Carotid Artery Velocity, m/s | Peak Left Carotid Artery Velocity, m/s | Peak Right/Left Carotid Artery Velocity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prebanding baseline | |||

| WT | 42.1±6.3 | 40.8±5.5 | 1.0±0.5 |

| MuRF1−/− | 50.5±6.2 | 48.1±2.4 | 1.0±0.4 |

| Postbanding baseline | |||

| WT | 21.7±9.3 | 91.0±8.9 | 4.2±0.6* |

| MuRF1−/− | 25.7±13.7 | 98.4±6.6 | 3.8±1.2* |

| 4 days postdebanding | |||

| WT | 63.9±8.5 | 31.2±9.6 | 2.6±0.4† |

| MuRF1−/− | 75.4±7.3 | 80.6±5.6 | 1.2±0.5 |

| 1 wk postdebanding | |||

| WT | 57.8±6.8 | 58.3±3.0 | 0.9±0.8 |

| MuRF1−/− | 67.2±6.6 | 61.8±5.5 | 1.1±0.5 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 3 mice/group. Carotid Doppler velocities were performed at baseline and 4 and 7 days after mice had been debanded. WT, wild type; MuRF1, muscle ring finger-1.

P < 0.001 compared with baseline;

P < 0.001 compared with postdebanded MuRF1−/− and baseline WT peak velocities.

MuRF1−/− mice retain increases in wall thicknesses and cardiomyocyte size after TAC release.

To ascertain if the sustained increase in the LV mass index seen in MuRF1−/− mice after TAC release correlated with a lack of cardiac wall atrophy, we analyzed serial echocardiographic images of anterior and posterior ventricular walls in WT and MuRF1−/− mice before and after TAC release (Fig. 3). M-mode imaging identified an increase in both anterior and posterior wall thicknesses in WT and MuRF1−/− mice after 4 wk of TAC (Fig. 3A). Quantitative analysis of wall thickness in diastole demonstrated that MuRF1−/− mice increased anterior wall thickness 60.5% from baseline, which was ∼2.3-fold higher than the increase identified in WT mice (26.0%; Fig. 3B). Similarly, posterior wall thickness in MuRF1−/− mice increased 48.8% from baseline values, which was 1.9-fold higher than the increase identified in WT mice (25.3%; Fig. 3C). Consistent with our LV mass index results, anterior and posterior wall thicknesses in WT mice returned to baseline levels 4 days after TAC release. However, in MuRF1−/− mice, decreases of 47.3% and 30.5% (anterior and posterior wall thicknesses in diastole, respectively) occurred after 4 days post-TAC release but did not decrease further in the ensuing 4 wk. Surprisingly, during the TAC release time course, heart rate, percent fractional shortening, percent ejection fraction, and LV interventricular distance did not differ between MuRF1−/− and WT mice (Supplemental Fig. 2), indicating that neither MuRF1−/− nor WT heart function deteriorated during cardiac hypertrophy induction or after TAC release.

Fig. 3.

Transthoracic echocardiography on unanesthetized mice. A: representative M-mode images from MuRF1−/− and WT controls showing concentric increases in anterior and posterior wall thicknesses after TAC reversal (Rev/R). B and C: quantitative analyses of anterior wall (B) and posterior wall thicknesses (C) in diastole revealed that MuRF1−/− mice decreased wall thickness only minimally after 4 days of TAC release (indicated by arrows) but did not return to BL levels like WT mice. n = 3–25 mice/group. Arrows indicate the reversal of TAC.

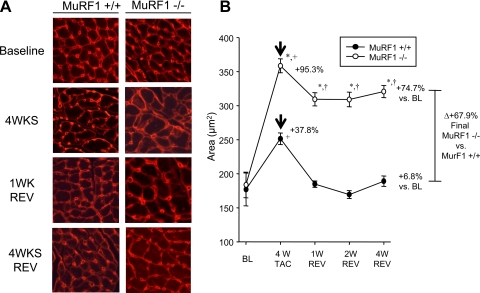

To determine whether the maintained cardiac wall thickness and mass seen in MuRF1−/− mice after TAC release represented a sustained increased in cardiomyocyte size, we next analyzed the cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes from WT and MuRF1−/− hearts (Fig. 4). Representative cross-sectional areas demonstrated that hearts lacking MuRF1 had an exaggerated increase in cardiomyocyte size compared with WT mice after TAC (Fig. 4A, 4 wk). Quantitative analysis of the cross-sectional areas revealed that MuRF1−/− cardiomyocytes increased their cross-sectional areas 95.3%, ∼2.5 times the increase in cross-sectional areas of WT mice at 4 wk of TAC (37.8%; Fig. 4B). In WT mice, the individual cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area decreased to baseline levels by 1 wk after TAC release, whereas at the same time point, MuRF1−/− cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area had decreased by only 20.6% (Fig. 4B). No further decrease in cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area was seen in MuRF1−/− hearts for the remainder of the TAC release period (Fig. 4A, 1 wk Rev and 4 wk Rev). A confounding issue with these findings is that MuRF1−/− hearts have an exaggerated cardiac hypertrophy, which proportionally decreases to the same extent as WT mice (∼30%; Fig. 2A). By several measures, including heart weight (Fig. 2) and wall thickness (Fig. 3), MuRF1−/− mice hypertrophy to nearly the same extent after 1 wk of TAC as WT mice do after 4 wk of TAC. To more clearly delineate the role of MuRF1 in pathological cardiac hypertrophy reversal, MuRF1−/− mice underwent TAC for 1 wk to achieve comparable cardiac hypertrophy to WT mice after 4 wk. The TAC was then released, and the degree of cardiac wall thickness was followed by echocardiography and histology (Supplemental Fig. 3 and Supplemental Table 1). Surprisingly, little if any decrease in anterior and posterior wall thicknesses was detected by echocardiography (Supplemental Fig. 3, A and B). Histological analysis of cardiomyocyte cross-sectional areas demonstrated a 9.6% decrease in size 7 days after the release of TAC (Supplemental Fig. 3, C and D). This contrasts to the 100% decrease in cardiac hypertrophy identified in WT mice 7 days after release of TAC and comparable cardiac hypertrophy (Figs. 2–4). These results demonstrate that MuRF1 is involved in regulating the decrease in cardiomyocyte mass during cardiac atrophy associated with hypertrophy regression.

Fig. 4.

MuRF1−/− cardiomyocytes are resistant to TAC reversal-induced reductions in size. A: representative cross-sectional micrographs of WT (left) and MuRF1−/− (right) hearts showing that cardiomyocytes from WT hearts returned to BL sizes after TAC reversal. B: quantitative analysis of cross-sectional cardiomyocyte areas. n = 2–4 mice/group; 50 measurements from multiple sections from multiple mice were taken. One-way ANOVA was performed to determine significance, followed by a Holm-Sidak pairwise comparison to significance between groups: +P < 0.001 vs. BL and †P < 0.001 vs. 4 wk of TAC. Student's t-test was performed to compared MuRF1−/− with WT animals: *P < 0.001 vs. WT controls. Arrows indicate the reversal of TAC.

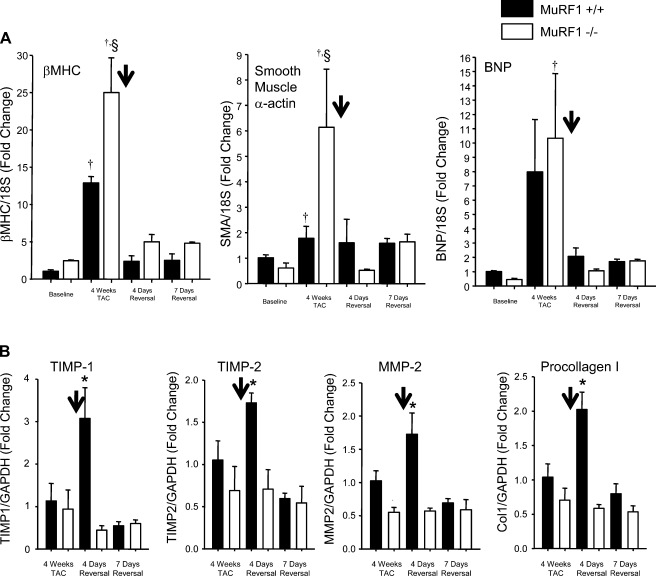

Lack of MuRF1 does not affect the suppression of hypertrophy-associated transcriptional activity after debanding.

The development of pressure overload-induced pathological cardiac hypertrophy is associated with signaling processes that result in the activation of distinct transcriptional programs (15). This includes activation of transcription factors such as SRF and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), which regulate the increase in genes normally expressed during development, including β-MHC, smooth muscle α-actin, and BNP. We compared the expression of these genes during cardiac atrophy resulting from the reversal of cardiac hypertrophy in WT and MuRF1−/− mice (Fig. 5A). Surprisingly, both MuRF1−/− and WT mice had comparable reductions in all three fetal genes examined after TAC release, indicating that the genes associated with pathological cardiac hypertrophy were similarly inactivated in both MuRF1−/− and WT hearts after unloading of the heart (Fig. 5A). This result suggests that the sustained cardiac hypertrophy seen in MuRF1−/− mice after TAC release is not due to continued prohypertrophic transcriptional programs and may instead be linked to impairments in mechanisms associated with cardiac muscle mass reduction.

Fig. 5.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of mRNA at baseline, after 4 wk of TAC, and 4 and 7 days after TAC reversal. A: expression of genes involved in cardiac hypertrophy [β-myosin heavy chain (MHC), smooth muscle α-actin, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP)]. B: expression of genes associated with cardiac remodeling [tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1, TIMP-2, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, and pro-collagen I]. One-way ANOVA was performed to determine significance, followed by a Holm-Sidak pairwise comparison to significance between groups: §P < 0.05 vs. WT mice at 4 wk of TAC; †P < 0.05 vs. WT and MuRF1−/− at BL, 4 days of TAC reversal, and 7 days TAC reversal; and *P < 0.001 vs. all other groups. Arrows indicate the reversal of TAC.

Genes associated with cardiac remodeling do not increase in MuRF1−/− mice after TAC release.

A clinical study (47) has demonstrated that the development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy and subsequent therapeutic atrophy is accompanied by changes in the cardiac extracellular matrix (ECM). The ECM is a network of collagens that sustains myocyte structure and function. The balance of collagen turnover is controlled by specific MMPs and inhibitors of MMPS called TIMPs. During LV atrophy associated with surgical repair of aortic stenosis, increases in MMP-2, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 have been reported (47). In the present study, we investigated the remodeling mechanism in MuRF1-/- hearts by determining the mRNA levels of proteins associated with regulation of the cardiac ECM, including pro-collagen I, procollagen III, and laminin. We also investigated the mRNA levels of enzymes that degrade these proteins, including MMP-2, MMP-13, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 (Fig. 5B). At 4 days after TAC release, WT mice expressed higher levels of cardiac TIMP-1, TIMP-2, MMP-2, and ColI compared with MuRF1−/− mice. We did not identify increases (or differences) in ColIII, Lamb, or MMP-13 during atrophy 4 or 7 days after TAC release in MuRF1−/− or WT mice (data not shown). These findings indicate that the expression of some genes associated with the ECM remodeling that accompanies atrophy associated with pathological cardiac hypertrophy regression (i.e., TIMP-1 and TIMP-2) is attenuated in mice lacking MuRF1, which may be associated with the apparent inability of MuRF1−/− cardiomyocytes to decrease in size after TAC release.

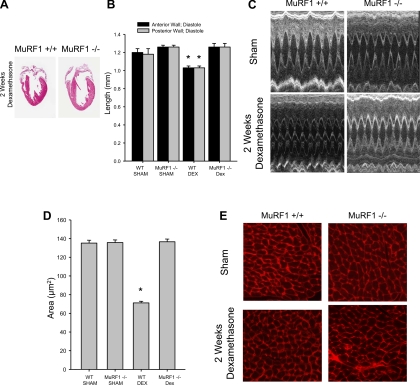

MuRF1 mediates the cardiac atrophy induced by dexamethasone treatment.

The experiments described above point to a critical role of MuRF1 in mediating cardiac atrophy associated with the regression of pathological hypertrophy. However, there has been some debate as to whether or not the process of hypertrophy regression involves the same cellular mechanics as pure muscle atrophy, that is, a decrease in muscle mass from a steady-state level. To test whether or not the effects of MuRF1 described above are specific to pathological hypertrophic regression, we also tested whether or not MuRF1 is involved in the cardiac atrophy induced by chronic dexamethasone treatment. A previous study (7) has already demonstrated that MuRF1 plays a significant role in mediating dexamethasone-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. We tested the effect of chronic dexamethasone treatment on cardiac wall thickness in WT and MuRF1−/− mice. Daily dexamethasone injections were given to mice for 2 wk and followed by echocardiography and histological analysis. When sham mice (saline injections only) were compared with WT mice receiving dexamethasone treatment, significant decreases in anterior and posterior wall thicknesses were identified (Fig. 6, A–C), with parallel decreases in cardiomyocyte cross-sectional areas (Fig. 6, D and E). However, MuRF1−/− animals were resistant to dexamethasone-induced cardiac atrophy and appeared to trend toward increased cardiac mass by heart weight/body weight measures (Table 2). In parallel experiments, osmotic pumps that released dexamethasone were implanted dorsally and left in place for 2 wk (7), followed by cardiac wall thickness assessment by echocardiography. When sham mice (osmotic pumps releasing vehicle only) were compared with WT mice undergoing dexamethasone treatment, significant decreases in anterior and posterior wall thicknesses in dexamethasone-treated animals were identified, as anticipated (Supplemental Fig. 4), along with cardiac dilation (Supplemental Table 2). In contrast, MuRF1−/− mice were resistant to dexamethasone-induced cardiac atrophy, as indicated by little or no changes in anterior and posterior wall thicknesses in diastole (Supplemental Fig. 4) or chamber dilation (Supplemental Table 2). Although it was noted that the osmotic pump experiments demonstrated a greater overall atrophy than the daily dexamethasone injections, technical issues with wound dehiscence (likely due to the dexamethasone treatment) made further analysis of this observation impractical. These findings suggest that MuRF1 mediates atrophy in the dexamethasome model in the same manner that it does in the atrophy associated with pathological cardiac hypertrophy regression. MuRF1 may therefore play a more generalized role in decreasing cardiac muscle mass in a variety of clinical scenarios.

Fig. 6.

Histological and echocardiographic analysis of MuRF1−/− mice after daily treatment with subcutaneous dexamethasone (Dex) treatment. A: representative histological cross sections at low power (hematoxylin and eosin stained; magnification: ×0.7). B: quantitative analysis of anterior and posterior wall thicknesses in diastole revealed that MuRF1−/− mice were resistant to Dex-induced wall thinning. C: representative M-mode images of mouse hearts after 2 wk of sham or Dex treatment. D: quantitative analysis of cross-sectional cardiomyocyte areas; 100 measurements from multiple sections from multiple mice were taken with representative histological sections shown in E. Histological analysis was representative of 2–3 individual mice/group. One-way ANOVA was performed to determine significance, followed by a Holm-Sidak pairwise comparison to significance between groups: *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups.

Table 2.

Transthoracic echocardiography on unanesthetized MuRF1−/− and WT control mice after 2 wk of daily subcutaneous saline or dexamethasone treatment

|

Saline Treatment |

Dexamethasone Treatment

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | MuRF1−/− | WT | MuRF1−/− | |

| n | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 581.3±22.5 | 614.9±12.1 | 585.8±15.7 | 596.8±13.1 |

| Anterior wall at diastole, mm | 1.20+0.02 | 1.26+0.02 | 1.03±0.02* | 1.26±0.04 |

| Posterior wall at diastole, mm | 1.18+0.04 | 1.19+0.01 | 0.97±0.01* | 1.18±0.01 |

| Anterior wall at systole, mm | 1.83+0.04 | 1.96+0.05 | 1.43±0.03 | 1.86±0.02 |

| Posterior wall at systole, mm | 1.70+0.04 | 1.58+0.03 | 1.44±0.03* | 1.67±0.03 |

| LVEDD | 2.8+0.4 | 3.4+0.3 | 3.0+0.1 | 3.2+0.1 |

| LVESD | 1.3+0.2 | 1.5+0.2 | 1.4+0.1 | 1.5+0.1 |

| LV mass/body weight, mg/g | 3.99+0.19 | 4.04+0.19 | 3.32±0.12* | 5.47±0.18* |

| LV mass/tibia length, mg/mm | 6.88+0.34 | 7.43+0.40 | 5.87±0.22* | 9.06±0.41* |

| Heart weight/body weight, mg/g | 5.20+0.28 | 5.74+0.25 | 4.18±0.07* | 6.01±0.25 |

| Fractional shortening, % | 54.5+1.0 | 55.0+0.9 | 52.8±1.8 | 54.8±0.8 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 86.5+0.90 | 86.5+0.7 | 84.7±1.5 | 86.4±0.6 |

Values are means ± SE; n, no. of mice/group. LVEDD, left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic dimension; LVESD, LV end-systolic dimension. LV mass was calculated as follows: (external LV diameter in diastole3 − LVEDD3) × 1.055. Fractional shortening was calculated as follows: (LVEDD − LVESD)/LVEDD × 100. The ejection fraction was calculated as follows: (end Simpson's diastolic volume − end Simpson's systolic volume)/end Simpson's diastolic volume × 100.

P < 0.05 vs. all other groups.

DISCUSSION

The development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy is a common precursor to heart failure and heightens the risk of heart failure and arrhythmias. Not surprisingly, the reversal of pathological cardiac hypertrophy reduces these risks and is therefore an attractive process against which to target potential therapies. In the present study, we used two models of cardiac atrophy to investigate the role of MuRF1 in decreasing cardiac muscle mass in vivo. The concept of cardiac atrophy in the present study has been expanded from muscle mass loss from baseline levels to the decrease in muscle mass seen in the therapeutic regression of hypertrophic states. Our results demonstrate that MuRF1 is an essential mediator of the cardiac atrophy associated with both regression of TAC-induced pathological hypertrophy as well as the atrophy resulting from chronic dexamethasone treatment. Together, these findings demonstrate, for the first time, a major role for MuRF1 in the process of reducing cardiac muscle mass in vivo. As preclinical trials have demonstrated the value of blunting hypertrophic growth without compromising cardiac performance, the potential for antihypertrophy therapy has been suggested (19, 20). This strongly supports the notion of exploring MuRF1 as a useful therapeutic target in the quest to improve clinical outcomes and prevent heart failure in a wide range of patients.

While the reversal of pathological cardiac hypertrophy that occurs after the removal of pressure overload appears to involve a reduction in cardiomyocyte size, it is only one aspect of a broader process that involves the restoration of diastolic function and remodeling of the ECM. In clinical scenarios where high blood pressure is adequately treated or aortic stenosis is surgically repaired, reversal of pathological cardiac hypertrophy occurs in patients. In this situation, several studies have reported that regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy parallels improvements in diastolic dysfunction (12, 22, 30, 46). A balance of degradation by MMPs and TIMPs in the ECM is vital to the remodeling process that occurs during hypertrophy regression. In failing hearts, alterations in the balance of MMPs and their endogenous inhibitors (TIMPs) have been reported. The regulation of MMPs and TIMPs during the regression of pathological cardiac hypertrophy, which occurs in as little as 4 days in the present study, has not been previously reported. We identified that WT mice had an expected transient increase in MMP-2, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and ColI mRNA levels 4 days after TAC release. In contrast, these did not change in MuRF1−/− mice. While we don't necessarily believe that MuRF1 has a direct effect on ECM regulation, MuRF1's effect on cardiomyocyte size might allow it to indirectly affect the ECM.

In the present study, we identified, for the first time, that dexamethasone treatment in adult mice leads to a reduction in cardiac mass. This should be contrasted to the effects that dexamethasone has on the heart in both human and experimental neonates. Dexamethasone therapy in neonates for bronchpulmonary dysplasia, premature birth, and chronic lung disease has been reported to be associated with increased cardiac mass repeatedly (23, 38, 41, 48, 52). In a randomized clinical trial, a common side effect of dexamethasone therapy is cardiac hypertrophy after therapy for as little as 7 days, resulting in clinically significant symptoms (54). Therefore, the effects of dexamethasone-induced cardiac atrophy reported in the present study are observations likely confined to adult mouse hearts. The role of MuRF1 in this age-dependent effect in cardiac mass is tantalizing, however, beyond the scope of the present study.

MuRF1 is found exclusively in skeletal muscle and the heart and has been localized to the M-line of the sarcomere (3, 5). Structurally, MuRF1 contains a ring finger domain, a motif known to have ubiquitin ligase activity. Ubiquitin ligases interact with ubiquitin-activating and ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes to place ubiquitin chains on substrates to be recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome (50). Our laboratory was the first to identify that MuRF1 is a bona fide ubiquitin ligase capable of interacting with cardiac troponin I and tagging it for degradation in a proteasome-dependent manner (24). Other investigators have identified that MuRF1 interacts with additional sarcomeric proteins including telethonin and myotilin (51) as well as β-MHC, which is degraded in vivo by MuRF1 (13). In the present study, mice deficient for MuRF1 exhibited a significant attenuation in cardiac atrophy after TAC release, implicating MuRF1 as a key player in the sarcomeric degradation that occurs after cardiac unloading. The fact that MuRF1−/− hearts displayed some degree of cardiac atrophy after TAC release suggests that MuRF1 is not the only ubiquitin ligase operating in this process. A previous study (3) has demonstrated that the muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1, in addition to MuRF1, is capable of regulating the decrease in skeletal muscle mass that occurs during atrophy. When we examined the expression of both MuRF1 and atrogin-1 in WT mice in our model system, we found that both proteins were increased after the induction of TAC (Supplemental Fig. 5, A and B). The increase in atrogin-1 expression was comparable between MuRF1−/− and WT mice during cardiac atrophy after TAC release; however, the levels of MuRF2, a related MuRF family member, did not significantly change in either MuRF1−/− or WT mice after pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Supplemental Fig. 5C). The robust increase in atrogin-1 during cardiac atrophy associated with hypertrophy regression in MuRF1−/− mice could account for the small amount of hypertrophic regression seen in these mice during the first week after TAC release.

In the heart, MuRF1 was initially identified as a protein that inhibits the development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy by blocking PKC-ɛ signaling and degrading cardiac troponin I (2, 24). Consistent with this described role, we (49) have previously demonstrated that MuRF1−/− mice exhibit an amplified pathological cardiac hypertrophic response to TAC-induced pressure overload and that this effect persists for up to 2 wk after TAC induction. The development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy involves enhanced protein synthesis by individual myocytes (8, 33, 37). Recent studies (9, 11) have identified that, in addition to increased protein synthesis, proteasomal activity and protein turnover are also enhanced during the development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Given that the ubiquitin-proteasome system degrades as much as 30% of newly synthesized cellular proteins (17), it stands to reason that mice deficient in MuRF1, a ubiquitin ligase known to interact with and degrade multiple sarcomeric proteins, exhibit enhanced cardiac hypertrophy in response to TAC. Without MuRF1, a key component of the protein quality control system is missing in these mice, allowing for the extravagant build up of cardiac muscle with little or no protein degradation against which to balance.

We propose that one of MuRF1's key roles in the heart is to regulate the development and maintenance of pathological cardiac hypertrophy, perhaps by actively degrading worn sarcomeric proteins as part of a broader process of protein quality control. This would parallel MuRF1's proposed role in the protein quality control of creatine kinase, whereby oxidized forms of creatine kinase are preferentially ubiquitinated and targeted for degradation (27, 55). In addition to the role that MuRF1 appears to play in preventing pathological cardiac hypertrophy, we have also uncovered evidence in this study that MuRF1 is critical to the process of cardiac atrophy, paralleling the results of another study (3) in which skeletal muscle atrophy was induced in MuRF1−/− mice by limb denervation. In that study (3), MuRF1−/− mice had a 36% sparing of muscle mass loss after denervation, indicating that MuRF1 plays an active role in skeletal muscle atrophy. MuRF1's ability to degrade specific sarcomeric proteins is likely the underlying process that mediates both cardiac and skeletal muscle atrophy in these studies.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the University of North Carolina Research Council, the R. J. Reynolds Faculty Development Award from the University of North Carolina Foundation, an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant, the Children's Cardiomyopathy Foundation (to M. S. Willis), and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-065619 (to C. Patterson).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Janice Weaver in the Animal Histopathology Laboratory at the University of North Carolina for assistance in preparing histological specimens.

All work was performed at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article is available online at the American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agbenyega ET, Wareham AC. Effect of clenbuterol on skeletal muscle atrophy in mice induced by the glucocorticoid dexamethasone. Comp Biochem Physiol Comp Physiol 102: 141–145, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arya R, Kedar V, Hwang JR, McDonough H, Li HH, Taylor J, Patterson C. Muscle ring finger protein-1 inhibits PKCɛ activation and prevents cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Cell Biol 167: 1147–1159, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, Lai VK, Nunez L, Clarke BA, Poueymirou WT, Panaro FJ, Na E, Dharmarajan K, Pan ZQ, Valenzuela DM, DeChiara TM, Stitt TN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 294: 1704–1708, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burkhoff D, Klotz S, Mancini DM. LVAD-induced reverse remodeling: basic and clinical implications for myocardial recovery. J Card Fail 12: 227–239, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centner T, Yano J, Kimura E, McElhinny AS, Pelin K, Witt CC, Bang ML, Trombitas K, Granzier H, Gregorio CC, Sorimachi H, Labeit S. Identification of muscle specific ring finger proteins as potential regulators of the titin kinase domain. J Mol Biol 306: 717–726, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cipriano C, Gosse P, Bemurat L, Mas D, Lemetayer P, N'Tela G, Clementy J. Prognostic value of left ventricular mass and its evolution during treatment in the Bordeaux cohort of hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens 14: 524–529, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke BA, Drujan D, Willis MS, Murphy LO, Corpina RA, Burova E, Rakhilin SV, Stitt TN, Patterson C, Latres E, Glass DJ. The E3 ligase MuRF1 degrades myosin heavy chain protein in dexamethasone-treated skeletal muscle. Cell Metab 6: 376–385, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman PS, Parmacek MS, Lesch M, Samarel AM. Protein synthesis and degradation during regression of thyroxine-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 21: 911–925, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Depre C, Wang Q, Yan L, Hedhli N, Peter P, Chen L, Hong C, Hittinger L, Ghaleh B, Sadoshima J, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Madura K. Activation of the cardiac proteasome during pressure overload promotes ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation 114: 1821–1828, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devereux RB, Wachtell K, Gerdts E, Boman K, Nieminen MS, Papademetriou V, Rokkedal J, Harris K, Aurup P, Dahlof B. Prognostic significance of left ventricular mass change during treatment of hypertension. JAMA 292: 2350–2356, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickhout JG, Austin RC. Proteasomal regulation of cardiac hypertrophy: is demolition necessary for building? Circulation 114: 1796–1798, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyadyk AI, Bagriy AE, Lebed IA, Yarovaya NF, Schukina EV, Taradin GG. ACE inhibitors captopril and enalapril induce regression of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12: 945–951, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fielitz J, Kim MS, Shelton JM, Latif S, Spencer JA, Glass DJ, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Myosin accumulation and striated muscle myopathy result from the loss of muscle RING finger 1 and 3. J Clin Invest 117: 2486–2495, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frey N, Katus HA, Olson EN, Hill JA. Hypertrophy of the heart: a new therapeutic target? Circulation 109: 1580–1589, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frey N, Olson EN. Cardiac hypertrophy: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Annu Rev Physiol 65: 45–79, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilson H, Schakman O, Combaret L, Lause P, Grobet L, Attaix D, Ketelslegers JM, Thissen JP. Myostatin gene deletion prevents glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy. Endocrinology 148: 452–460, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg AL Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature 426: 895–899, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haider AW, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Increased left ventricular mass and hypertrophy are associated with increased risk for sudden death. J Am Coll Cardiol 32: 1454–1459, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill JA, Karimi M, Kutschke W, Davisson RL, Zimmerman K, Wang Z, Kerber RE, Weiss RM. Cardiac hypertrophy is not a required compensatory response to short-term pressure overload. Circulation 101: 2863–2869, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill JA, Olson EN. Cardiac plasticity. N Engl J Med 358: 1370–1380, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoshijima M Mechanical stress-strain sensors embedded in cardiac cytoskeleton: Z disk, titin, and associated structures. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1313–H1325, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikonomidis I, Tsoukas A, Parthenakis F, Gournizakis A, Kassimatis A, Rallidis L, Nihoyannopoulos P. Four year follow up of aortic valve replacement for isolated aortic stenosis: a link between reduction in pressure overload, regression of left ventricular hypertrophy, and diastolic function. Heart 86: 309–316, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Israel BA, Sherman FS, Guthrie RD. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with dexamethasone therapy for chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Am J Perinatol 10: 307–310, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kedar V, McDonough H, Arya R, Li HH, Rockman HA, Patterson C. Muscle-specific RING finger 1 is a bona fide ubiquitin ligase that degrades cardiac troponin I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 18135–18140, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koren MJ, Devereux RB, Casale PN, Savage DD, Laragh JH. Relation of left ventricular mass and geometry to morbidity and mortality in uncomplicated essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med 114: 345–352, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koren MJ, Ulin RJ, Koren AT, Laragh JH, Devereux RB. Left ventricular mass change during treatment and outcome in patients with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens 15: 1021–1028, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koyama S, Hata S, Witt CC, Ono Y, Lerche S, Ojima K, Chiba T, Doi N, Kitamura F, Tanaka K, Abe K, Witt SH, Rybin V, Gasch A, Franz T, Labeit S, Sorimachi H. Muscle RING-finger protein-1 (MuRF1) as a connector of muscle energy metabolism and protein synthesis. J Mol Biol 376: 1224–1236, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krumholz HM, Larson M, Levy D. Prognosis of left ventricular geometric patterns in the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 25: 879–884, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med 322: 1561–1566, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loureiro J, Smith S, Fonfara S, Swift S, James R, Dukes-McEwan J. Canine dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction: assessment of myocardial function and clinical outcome. J Small Anim Pract 49: 578–586, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maybaum S, Mancini D, Xydas S, Starling RC, Aaronson K, Pagani FD, Miller LW, Margulies K, McRee S, Frazier OH, Torre-Amione G. Cardiac improvement during mechanical circulatory support: a prospective multicenter study of the LVAD Working Group. Circulation 115: 2497–2505, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McElhinny AS, Kakinuma K, Sorimachi H, Labeit S, Gregorio CC. Muscle-specific RING finger-1 interacts with titin to regulate sarcomeric M-line and thick filament structure and may have nuclear functions via its interaction with glucocorticoid modulatory element binding protein-1. J Cell Biol 157: 125–136, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgan HE, Kira Y, Gordon EE. Aortic pressure, substrate utilization and protein synthesis. Eur Heart J 5, Suppl F: 141–146, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mrosek M, Labeit D, Witt S, Heerklotz H, von Castelmur E, Labeit S, Mayans O. Molecular determinants for the recruitment of the ubiquitin-ligase MuRF-1 onto M-line titin. FASEB J 21: 1383–1392, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muiesan ML, Salvetti M, Rizzoni D, Castellano M, Donato F, Agabiti-Rosei E. Association of change in left ventricular mass with prognosis during long-term antihypertensive treatment. J Hypertens 13: 1091–1095, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okin PM, Devereux RB, Jern S, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Nieminen MS, Snapinn S, Harris KE, Aurup P, Edelman JM, Wedel H, Lindholm LH, Dahlof B. Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy during antihypertensive treatment and the prediction of major cardiovascular events. JAMA 292: 2343–2349, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parmacek MS, Magid NM, Lesch M, Decker RS, Samarel AM. Cardiac protein synthesis and degradation during thyroxine-induced left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 251: C727–C736, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riede FT, Schulze E, Vogt L, Schramm D. Irreversible cardiac changes after dexamethasone treatment for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Cardiol 22: 363–364, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schillaci G Pharmacogenomics of left ventricular hypertrophy reversal: beyond the “one size fits all” approach to antihypertensive therapy. J Hypertens 22: 2273–2275, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Selzman CH, Sheridan BC. Off-pump insertion of continuous flow left ventricular assist devices. J Card Surg 22: 320–322, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skelton R, Gill AB, Parsons JM. Cardiac effects of short course dexamethasone in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 78: F133–F137, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stansfield WE, Rojas M, Corn D, Willis M, Patterson C, Smyth SS, Selzman CH. Characterization of a model to independently study regression of ventricular hypertrophy. J Surg Res 142: 387–393, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ueberham E, Low R, Ueberham U, Schonig K, Bujard H, Gebhardt R. Conditional tetracycline-regulated expression of TGF-beta1 in liver of transgenic mice leads to reversible intermediary fibrosis. Hepatology 37: 1067–1078, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verdecchia P, Angeli F, Borgioni C, Gattobigio R, de Simone G, Devereux RB, Porcellati C. Changes in cardiovascular risk by reduction of left ventricular mass in hypertension: a meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens 16: 895–899, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Gattobigio R, Zampi I, Reboldi G, Porcellati C. Prognostic significance of serial changes in left ventricular mass in essential hypertension. Circulation 97: 48–54, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Villari B, Vassalli G, Monrad ES, Chiariello M, Turina M, Hess OM. Normalization of diastolic dysfunction in aortic stenosis late after valve replacement. Circulation 91: 2353–2358, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walther T, Schubert A, Falk V, Binner C, Kanev A, Bleiziffer S, Walther C, Doll N, Autschbach R, Mohr FW. Regression of left ventricular hypertrophy after surgical therapy for aortic stenosis is associated with changes in extracellular matrix gene expression. Circulation 104: I54–58, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Werner JC, Sicard RE, Hansen TW, Solomon E, Cowett RM, Oh W. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with dexamethasone therapy for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr 120: 286–291, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willis MS, Ike C, Li L, Wang DZ, Glass DJ, Patterson C. Muscle ring finger 1, but not muscle ring finger 2, regulates cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Circ Res 100: 456–459, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willis MS, Schisler JC, Patterson C. Appetite for destruction: E3 ubiquitin-ligase protection in cardiac disease. Future Cardiol 4: 65–75, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Witt SH, Granzier H, Witt CC, Labeit S. MURF-1 and MURF-2 target a specific subset of myofibrillar proteins redundantly: towards understanding MURF-dependent muscle ubiquitination. J Mol Biol 350: 713–722, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yeh TF, Lin YJ, Hsieh WS, Lin HC, Lin CH, Chen JY, Kao HA, Chien CH. Early postnatal dexamethasone therapy for the prevention of chronic lung disease in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome: a multicenter clinical trial. Pediatrics 100: E3, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zafeiridis A, Jeevanandam V, Houser SR, Margulies KB. Regression of cellular hypertrophy after left ventricular assist device support. Circulation 98: 656–662, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zecca E, Papacci P, Maggio L, Gallini F, Elia S, De Rosa G, Romagnoli C. Cardiac adverse effects of early dexamethasone treatment in preterm infants: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Pharmacol 41: 1075–1081, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao TJ, Yan YB, Liu Y, Zhou HM. The generation of the oxidized form of creatine kinase is a negative regulation on muscle creatine kinase. J Biol Chem 282: 12022–12029, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]