Abstract

The role of nucleus of solitary tract (NTS) A2a adenosine receptors in baroreflex mechanisms is controversial. Stimulation of these receptors releases glutamate within the NTS and elicits baroreflex-like decreases in mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), and renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA), whereas inhibition of these receptors attenuates HR baroreflex responses. In contrast, stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors increases preganglionic adrenal sympathetic nerve activity (pre-ASNA), and the depressor and sympathoinhibitory responses are not markedly affected by sinoaortic denervation and blockade of NTS glutamatergic transmission. To elucidate the role of NTS A2a adenosine receptors in baroreflex function, we compared full baroreflex stimulus-response curves for HR, RSNA, and pre-ASNA (intravenous nitroprusside/phenylephrine) before and after bilateral NTS microinjections of selective adenosine A2a receptor agonist (CGS-21680; 2.0, 20 pmol/50 nl), selective A2a receptor antagonist (ZM-241385; 40 pmol/100 nl), and nonselective A1 + A2a receptor antagonist (8-SPT; 1 nmol/100 nl) in urethane/α-chloralose anesthetized rats. Activation of A2a receptors decreased the range, upper plateau, and gain of baroreflex-response curves for RSNA, whereas these parameters all increased for pre-ASNA, consistent with direct effects of the agonist on regional sympathetic activity. However, no resetting of baroreflex-response curves along the MAP axis occurred despite the marked decreases in baseline MAP. The antagonists had no marked effects on baseline variables or baroreflex-response functions. We conclude that the activation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors differentially alters baroreflex control of HR, RSNA, and pre-ASNA mostly via non-baroreflex mechanism(s), and these receptors have virtually no tonic action on baroreflex control of these sympathetic outputs.

Keywords: A2a adenosine receptor agonist, A2a adenosine receptor antagonist, baroreflex function, renal nerve, adrenal nerve

the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) is an important relay for afferent input from baroreceptors and therefore plays a critical role in central cardiovascular control. Among many neurochemical substances operating in the NTS, adenosine may be considered an important neuromodulator, which may inhibit and facilitate neurotransmitter release via presynaptic A1 and A2a adenosine receptor subtypes, respectively (9, 12, 13). Several studies from our laboratory and by others showed that adenosine may modulate cardiovascular control at the level of the NTS under both physiological and pathological conditions (1, 3, 4, 6, 10, 11, 16–29, 31). Our recent studies implied that activation of A1 adenosine receptors in the NTS resets baroreflex control of regional sympathetic outputs toward higher mean arterial pressure (MAP), probably via inhibition of glutamate release in the baroreflex pathway (16, 21). However, previous studies usually suggested that NTS A2a, not A1, adenosine receptors contribute to baroreflex mechanisms (1, 5, 11, 29). These suggestions were based on observations that microinjections of adenosine or a selective agonist of A2a adenosine receptors (CGS-21680) into the NTS evoke baroreflex-like decreases in MAP, heart rate (HR), and renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) (1, 4, 10, 11, 28, 31). Furthermore, nonselective stimulation of NTS adenosine receptors as well as selective activation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors increased glutamate release, whereas blockade of glutamatergic transmission attenuated depressor responses evoked by microinjections of adenosine into the NTS (5, 11). These studies suggested that activation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors may facilitate release of glutamate in the baroreflex arch. However, a study from our laboratory showed that, in contrast to baroreflex-like decreases in MAP, HR, and RSNA, stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors did not alter lumbar (LSNA) and actually increased preganglionic adrenal (pre-ASNA) sympathetic nerve activity, responses inconsistent with those evoked by arterial baroreceptor activation (15, 18, 19). In addition, we have shown that bilateral sinoaortic denervation combined with vagotomy (SAD + VX) as well as bilateral blockade of glutamatergic transmission in the NTS did not significantly attenuate the decreases in MAP, HR, and RSNA (19, 20). These observations, in contrast to previous reports, strongly suggested that the hemodynamic and differential sympathetic responses to stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors were mediated mostly via non-baroreflex mechanisms (19, 20). However, Thomas et al. observed that blockade of NTS A2a adenosine receptors attenuated baroreflex responses of HR (but not MAP) evoked by stimulation of the aortic depressor nerve (29). These contradictory conclusions suggest that NTS A2a adenosine receptors may differentially modulate baroreflex control of regional sympathetic activity.

Even if the differential sympathetic responses to stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors were mediated entirely via non-baroreflex mechanisms, the observed reciprocal changes in baseline levels of regional sympathetic activity (increases in pre-ASNA vs. decreases in RSNA) could likely affect baroreflex control of these sympathetic outputs in a regionally specific manner. For example, with the stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors, marked increases in pre-ASNA occur. Even if this increase occurs via non-baroreflex mechanisms, with the large increase in the baseline level, several possible changes in the sigmoidal baroreflex function curve for this sympathetic output could occur: 1) the curve may be reset upward, without changes in other parameters such as range and baroreflex gain; 2) the upper plateau of the function may increase without changes in the lower plateau, which could lead to increase of the response range and perhaps gain depending on whether the stimulus range also expands; 3) the function may be reset rightward, toward higher MAP needed to exert greater activation of baroreceptors and greater inhibition of increased sympathetic drive; and 4) combined resetting may occur (upward + rightward + increase function range). Similar, but opposite alternatives of resetting should be considered for RSNA and HR, which decrease following stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors. However, it remains unknown which, if any, of those possible scenarios occurs during stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors. It is also unknown whether blockade of NTS A2a adenosine receptors may reveal a tonic modulation of baroreflex control of regional sympathetic outputs. The present study was designed to answer all the above questions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All protocols and surgical procedures employed in this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals endorsed by the American Physiological Society and published by the National Institutes of Health.

Design.

The effects of activation or blockade of NTS A2a adenosine receptors on sigmoidal baroreflex stimulus-response curves constructed for regional SNA (RSNA and pre-ASNA) and HR were studied in 35 male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 330–430 g (mean ± SE = 368.3 ± 4.2 g). In 17 rats, A2a adenosine receptors were activated via bilateral microinjections into the subpostremal NTS of two different doses of the selective agonist CGS-21680 (CGS; 2.0 and 20 pmol/50 nl). In nine rats, A2a adenosine receptors were inhibited with the selective antagonist ZM-241385 (ZM; 40 pmol in 100 nl). In another nine rats, A1 and A2a adenosine receptors were inhibited with the nonselective A1 and A2a receptor antagonist 8-(p-sulfophenyl) theophylline (8-SPT; 1 nmol in 100 nl). In an additional eight and nine rats, the effects of bilateral microinjections of two volumes of vehicle [artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACF), 50 and 100 nl, respectively] on the baroreflex functions were evaluated.

Instrumentation and measurements.

All procedures were described in detail previously (3, 15, 16, 18–21, 23–25). Briefly, male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River) were anesthetized with a mixture of α-chloralose (80 mg/kg) and urethane (500 mg/kg ip), tracheotomized, connected to a small-animal respirator (SAR-830, CWE, Ardmore, PA), and artificially ventilated with a 40% oxygen-60% nitrogen mixture. Arterial blood gases were tested occasionally (Radiometer, ABL500, OSM3), and ventilation was adjusted to maintain Po2, Pco2, and pH within normal ranges. Average values measured at the end of each experiment were Po2 = 156.4 ± 2.4 Torr, Pco2 = 40.2 ± 0.4 Torr, and pH = 7.386 ± 0.006 (n = 52). The left femoral artery and vein were catheterized to monitor arterial blood pressure and infuse supplementary doses of anesthesia (12–21 mg·kg−1·h−1 of α-chloralose and 76–133 mg·kg−1·h−1 of urethane dissolved in 2.4–4.2 ml·kg−1·h−1 saline), respectively. Two additional catheters were placed into the right femoral vein to infuse sodium nitroprusside and phenylephrine, respectively.

In each experiment, simultaneous recordings from RSNA and pre-ASNA were performed. These nerves were exposed retroperitoneally, and neural recordings were accomplished as described previously (15, 16, 18–21, 23–25). Neural signals were initially amplified (2,000–20,000×) with bandwidth set at 100–1,000 Hz, digitized, rectified, and averaged in 1-s intervals. Background noise was determined 30–60 min after the animal was euthanized. Resting nerve activity before each microinjection was normalized to 100%.

The ratio between preganglionic and total nerve activity was initially tested with an intravenous bolus injection of the short-lasting (1–2 min) ganglionic blocker Arfonad (trimethaphan, 2 mg/kg; Hoffmann-La Roche) and reevaluated at the end of each experiment with hexamethonium (20 mg/kg iv). RSNA was almost completely postganglionic; only 4.3 ± 0.5% (n = 52) of the activity persisted after the ganglionic blockade. According to the criteria established in our laboratory's previous studies (16, 19–21, 23–25), pre-ASNA was considered as predominantly preganglionic if the activity remaining after ganglionic blockade at the end of each experiment was >75%. Average pre-ASNA measured after ganglionic blockade was 128.1 ± 4.1% (n = 52). Pre-ASNA increased over 100% likely because of an arterial baroreflex response caused by the decrease in MAP after ganglionic blockade. The arterial pressure and neural signals were digitized and recorded with a Hemodynamic and Neural Data Analyzer (Biotech Products, Greenwood, IN), averaged over 1-s intervals, and stored on hard disk for subsequent analysis.

Microinjections into the NTS.

Bilateral microinjections of two different doses of the selective A2a receptor agonist (CGS-21680, 2.0 and 20 pmol) and the selective and nonselective A2a receptor antagonists (ZM-241385 and 8-SPT, respectively) were made with multibarrel glass micropipettes into the medial region of the caudal subpostremal NTS as described previously (3, 16, 18–21, 23–25). In a separate group of animals, microinjections of the same amount of vehicle (50 nl or 100 nl of ACF) into the same site of the NTS were performed as respective volume controls. All microinjection sites were verified histologically as described previously (3, 16, 18–21, 23–25) and are presented in Fig. 1 according to the atlas of the rat subpostremal NTS by Barraco et al. (2).

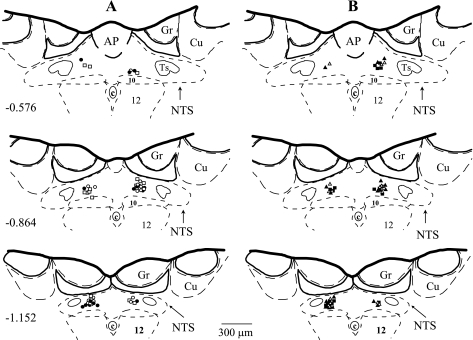

Fig. 1.

Microinjection sites in subpostremal nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) for all experiments. Schematic diagrams show transverse sections of medulla oblongata from a rat brain. AP, area postrema; c, central canal; 10, dorsal motor nucleus of vagus nerve; 12, nucleus of hypoglossal nerve; Ts, tractus solitarius; Gr, gracile nucleus; Cu, cuneate nucleus. Scale is shown at bottom; number on left schematic diagram denotes the rostrocaudal position in millimeters of the section relative to the obex according to the atlas of the rat subpostremal NTS by Barraco et al. (2). Microinjection sites for selective NTS A2a adenosine receptor agonist (CGS-21680; 2.0 and 20 pmol in 50 nl; n = 9 and 8, respectively), selective A2a adenosine receptor antagonist (ZM-241385; 40 pmol in 100 nl; n = 9), nonselective A1 + A2a adenosine receptor antagonist (8-SPT; 1 nmol in 100 nl; n = 9), and respective volume control [artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACF); 50 and 100 nl; n = 8 and 9, respectively] were marked with fluorescent dye. A: ○, CGS 2.0 pmol; •, CGS 20 pmol; □, ACF 50 nl. B: ▵, ZM; ▴, 8-SPT; ▪, ACF 100 nl.

The doses of CGS-21680 were the same as those used in our laboratory's previous studies (18–20, 23): 1) the approximate threshold hypotensive dose (2 pmol diluted in 50 nl) and 2) the maximally effective hypotensive dose (20 pmol in 50 nl) (1). Selective blockade of adenosine A2a receptors was achieved by bilateral microinjections into the NTS of selective A2a receptor antagonist ZM-241385 (40 pmol in 100 nl). Combined blockade of both A1 and A2a adenosine receptor subtypes located in the NTS was accomplished with bilateral microinjections of 8-SPT (1 nmol in 100 nl). The doses of antagonists were similar to those used effectively in previous studies (24, 29). The volume of microinjected antagonists was the same as used in our previous studies where other NTS receptors/mechanisms (glutamatergic, nitroxidergic, or vasopressinergic) were effectively antagonized (20, 21, 23–25). All drugs were dissolved in ACF, and the pH was adjusted to 7.2.

Baroreflex stimulus-response relationships.

The sigmoidal baroreflex-response curves were constructed similarly as described in our laboratory's previous paper (16). Briefly, MAP was decreased by graded intravenous infusion of sodium nitroprusside (200 mg/ml, 4–6 steps, 0.25–8 ml/h) until maximal steady-state increases in SNA and HR were observed for at least 1 min. MAP was allowed to return to the resting values and then increased via graded intravenous infusion of phenylephrine (200 mg/ml, 4–6 steps, 0.5–8 ml/h) until the steady-state maximal decreases in SNA and HR were observed. The values between the upper and lower plateaus of the responses were used to construct baroreflex-response curves for each variable (RSNA, pre-ASNA, and HR). This method allowed us to generate whole sigmoidal baroreflex-response curves (slow ramp changes) over ∼6–10 min, a period short enough to match the plateau of maximal responses to stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors. The timeline of the protocol is presented in Fig. 2.

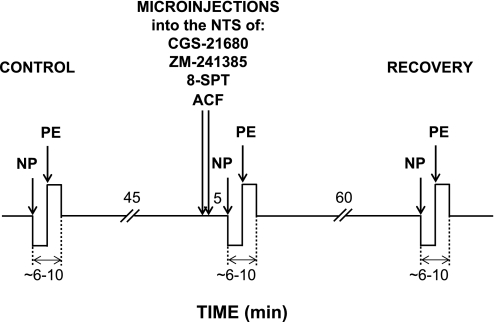

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of the experimental protocol. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was decreased and increased via intravenous infusion of sodium nitroprusside (NP) and phenylephrine (PE), respectively. Baroreflex response curves were performed under control conditions, following bilateral microinjections into the NTS of selective A2a adenosine receptor agonist CGS-21680 (2.0 and 20 pmol in 50 nl), selective A2a adenosine receptor antagonist ZM-241385 (40 pmol in 100 nl), nonselective A1 + A2a adenosine receptor antagonist 8-SPT (1 nmol in 100 nl), or respective volume control (ACF; 50 and 100 nl for the agonist and the antagonists, respectively), and ∼70 min after the microinjections of the agonist and the antagonists (recovery).

Data analysis.

The baroreflex response curves for RSNA, pre-ASNA, and HR generated under control conditions were compared with the functions generated after bilateral stimulation or blockade of NTS A2a adenosine receptors, combined blockade of A1 + A2a adenosine receptors, and after bilateral microinjections of respective volume controls into the NTS. Control baroreflex response functions obtained before microinjections of CGS-21680 and the adenosine receptor antagonists were also compared with the functions generated ∼70 min after the microinjections (recovery). Sigmoidal logistic baroreflex curves were approximated to experimental data points (averaged in 1-s intervals) according to the model described by Kent et al. (8) with SigmaPlot for Windows 9.0 and the formula:

|

(1) |

where P1 is the upper plateau of the curve, P2 is the lower plateau, P3 is a coefficient describing the distribution of gain along the curve, and P4 is MAP in the midpoint of the curve (BP50). Maximum gain (Gmax) was calculated according to the formula:

|

(2) |

The range of baroreflex control was calculated as a difference between upper and lower plateaus (range = P1 − P2). The baroreflex response curves were calculated for each animal under each experimental condition and then averaged across animals.

The ANOVA and significance of differences between mean values were calculated with the statistical package SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Two-way ANOVA for repeated measures was used to compare the absolute values of parameters of the baroreflex response functions across the experimental conditions (control vs. microinjection and control vs. recovery) and across the two sympathetic nerves (renal vs. adrenal). In addition, the relative changes of baroreflex functions were calculated as differences between the parameters of control baroreflex function vs. respective parameters of baroreflex functions measured following microinjections into the NTS of CGS-21680, ZM-241385, 8-SPT, and respective volume controls. Two-way ANOVA for independent measures was used to analyze the relative changes in baroreflex response functions evoked by two doses of CGS-21680 or two adenosine receptor antagonists (ZM-241385, 8-SPT) vs. the changes evoked by respective volume controls (ACF) for two sympathetic nerves (RSNA vs. pre-ASNA). If significant interactions were found (nerve × experimental condition and nerve × dose), the differences between the means were calculated with a modified Bonferroni t-test. One-way ANOVA for independent measures followed by modified Bonferroni t-test was used for comparison of HR and MAP responses evoked by microinjection of two doses of CGS-21680, two adenosine receptor antagonists, and ACF. Also one-way ANOVA for independent measures was used to evaluate changes in the parameters of HR baroreflex response functions evoked by two doses of CGS-21680 and the respective volumes of ACF (50 nl) or the two adenosine receptor antagonists and the respective volumes of ACF (100 nl). The relative changes of MAP, HR, RSNA, and pre-ASNA evoked by bilateral microinjections of two doses of CGS-21680, two adenosine receptor antagonists, and the respective volume of vehicle were calculated as a change between resting values averaged during the last 30 s preceding the microinjections and the last 30 s of the 5-min period of the response to microinjections measured before generating the second baroreflex curve. An α level of P < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

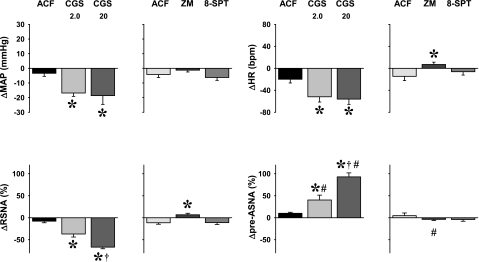

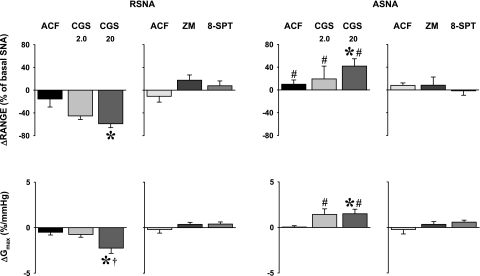

Basal MAP and HR measured before the control baroreflex response curves in each animal (n = 52) were 94.9 ± 1.4 mmHg and 365.0 ± 6.5 beats/min, respectively. Approximately 45 min after the control baroreflex curves, the basal parameters, measured just before microinjections into the NTS of selective A2a adenosine receptor agonist (CGS-21680), selective A2a receptors antagonists (ZM-241385), nonselective A1 + A2a receptors antagonist (8-SPT), or vehicle (ACF) returned to normal levels: 96.8 ± 1.5 mmHg and 366.4 ± 6.3 beats/min for MAP and HR, respectively. Also, in those animals in which the third baroreflex curve was performed ∼70 min after the microinjections of CGS-21680 or the adenosine receptor antagonists (recovery, n = 35), basal MAP (95.3 ± 1.3 mmHg) and HR (358.3 ± 6.8 beats/min) were similar to those measured at the beginning of the experiment. There were no significant differences between basal levels of MAP and HR measured during the three stages of the experiments: control, stimulation, or blockade of NTS A2a adenosine receptors, and recovery (P > 0.05 for all comparisons). The effects of bilateral microinjection of two doses of selective A2a adenosine receptor agonist (CGS-21680, 2.0 and 20 pmol in 50 nl, n = 9 and 8, respectively), two adenosine receptor antagonists (selective A2a receptors antagonist, ZM-241385, 40 pmol in 100 nl, n = 9; and nonselective A1 + A2a receptor antagonist, 8-SPT, 1 nmol in 100 nl, n = 9), and respective volumes of vehicle (ACF, 50 nl and 100 nl, n = 8 and 9, respectively) on resting hemodynamic and neural variables are presented in Fig. 3. These responses were similar to those observed in our previous studies where unilateral microinjections were used (18, 19, 23–25).

Fig. 3.

Responses of basal hemodynamic and neural variables to bilateral microinjections of selective NTS A2a adenosine receptor agonist CGS-21680 (CGS; 2.0 and 20 pmol in 50 nl; n = 9 and 8, respectively), selective A2a adenosine receptor antagonist ZM-241385 (ZM; 40 pmol in 100 nl; n = 9), nonselective A1 + A2a adenosine receptor antagonist 8-SPT (1 nmol in 100 nl; n = 9), and respective volume controls (ACF; 50 and 100 nl for the agonist and the antagonists; n = 8 and 9, respectively). *P < 0.05 vs. ACF. †P < 0.05 vs. CGS 2.0 pmol. #P < 0.05 vs. RSNA.

Effects of stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors on baroreflex control of SNA.

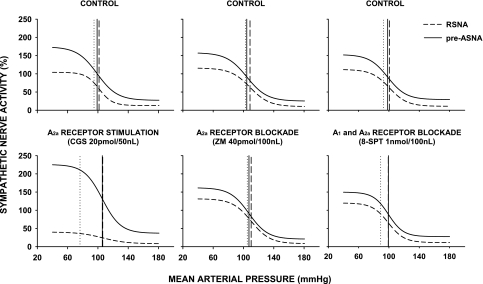

The examples of original recordings of baroreflex function curves generated under control and different experimental conditions (following microinjections of ACF, CGS-21680, and ZM-241385) are presented in Fig. 4. Sigmoidal baroreflex response curves for RSNA and pre-ASNA obtained under control conditions (Fig. 5, top) were similar to those observed in our laboratory's previous studies (15, 16) (Table 1). The midpoints of baroreflex functions (BP50) were similar for both sympathetic outputs (P = 0.126) and were located close to the resting MAP (Fig. 5, top, and Table 1).

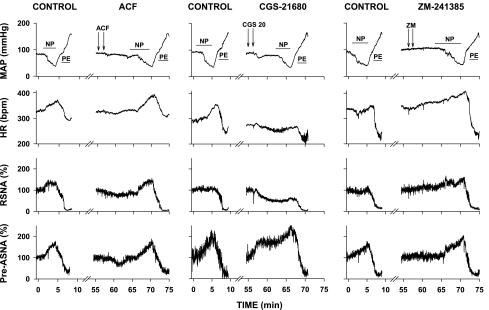

Fig. 4.

Examples of original recordings of baroreflex responses obtained under control conditions and following microinjections of volume control (ACF), and selective agonist and antagonist of A2a adenosine receptors (CGS, CGS-21680, 20 pmol; and ZM, ZM-241385, 40 pmol, respectively). Arterial pressure was decreased and subsequently increased via intravenous infusions of NP and PE. The time of intravenous infusion is marked with horizontal lines. Microinjections are marked with arrows. Note that baroreflex responses to NP and PE were preserved despite of marked increase of pre-ASNA and marked decrease in RSNA caused by microinjection of CGS-21680.

Fig. 5.

Averaged baroreflex-response functions for renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) and preganglionic adrenal sympathetic nerve activity (pre-ASNA) under control conditions (top) and after bilateral microinjections of NTS A2a adenosine receptor agonist (CGS-21680; 20 pmol, n = 8), selective A2a adenosine antagonists (ZM-241385; n = 9), and nonselective A1 + A2a receptor antagonist (8-SPT; n = 9) (bottom). Vertical dotted, dashed, and solid lines indicate resting MAP and BP50 for RSNA and pre-ASNA, respectively.

Table 1.

Averaged parameters of sigmoidal baroreflex functions obtained for RSNA and preASNA under control conditions in all experiments

| BP50, mmHg | Range, % | Upper Plateau, % | Lower Plateau, % | Gmax, %/mmHg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSNA | 101.5±1.4 | 105.8±4.6 | 118.2±4.6 | 12.4±1.5 | 2.6±0.1 |

| Pre-ASNA | 100.0±1.2 | 130.8±5.1* | 160.2±5.0* | 29.5±1.8* | 2.7±0.1 |

Data are means ± SE (n = 52). BP50, mean arterial pressure (MAP) at midpoint of baroreflex curve; Gmax, maximum gain of sigmoidal baroreflex function; RSNA, renal sympathetic nerve activity; Pre-ASNA, preganglionic adrenal sympathetic nerve activity.

Significant difference vs. RSNA (P < 0.05).

Selective stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors did not reset baroreflex functions along the MAP axis. The midpoints of the functions (BP50) for RSNA and pre-ASNA remained unaltered despite the marked decreases in baseline MAP and RSNA and increases in baseline pre-ASNA evoked by the agonist (Figs. 3 and 5, Table 2). The stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors significantly decreased and increased the ranges of baroreflex response curves for RSNA and pre-ASNA, respectively (nerve × experimental condition interaction, P < 0.001 for both doses of selective A2a receptors agonist). The differential changes in the range of baroreflex regulation were largely a result of different changes in upper plateaus for each sympathetic output (Fig. 5 and Table 2). Selective stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors significantly decreased the upper plateau of baroreflex response curves for RSNA, whereas it increased the upper plateau for pre-ASNA (nerve × experimental condition interaction, P < 0.001 for both dose of selective A2a agonist). The changes in Gmax showed similar tendencies to those observed for the ranges and upper plateaus, i.e., stimulation of A2a adenosine receptors decreased Gmax for RSNA and tended to increase Gmax for pre-ASNA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Averaged parameters of sigmoidal baroreflex functions for RSNA and preASNA obtained before and after bilateral microinjections of two doses of A2a adenosine receptor agonist (CGS-21680), selective A2a and nonselective A1 +A2a adenosine receptor antagonists (ZM-241385 and 8-SPT, respectively), and respective volume controls

| n |

BP50, mmHg |

Range, %

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Injection | Recovery | Control | Injection | Recovery | ||

| RSNA | |||||||

| ACF 50 | 8 | 91.4±3.9 | 94.7±3.5 | 123.6±15.9 | 108.1±7.6 | ||

| CGS 2.0 | 9 | 103.0±4.2 | 101.0±5.4 | 102.0±2.8 | 107.2±17.6 | 47.5±6.8* | 129.9±14.9 |

| CGS 20 | 8 | 101.5±3.3 | 106.3±2.4 | 90.9±2.4 | 91.3±7.4 | 32.3±4.7* | 112.6±14.3 |

| ACF 100 | 9 | 101.2±6.9 | 108.9±10.7 | 100.5±9.2 | 106.0±8.5 | 95.1±7.0 | |

| ZM | 9 | 108.6±2.1 | 110.2±2.2 | 109.9±1.7 | 105.9±6.0 | 123.4±5.8 | 109.6±7.1 |

| 8-SPT | 9 | 100.6±1.8 | 99.1±2.6 | 99.4±2.7 | 101.2±6.9 | 108.9±10.7 | 100.5±9.2 |

| ASNA | |||||||

| ACF 50 | 8 | 94.9±3.5 | 95.4±4.7 | 155.5±5.2 | 125.5±7.7 | ||

| CGS 2.0 | 9 | 100.1±2.9 | 99.1±3.1 | 100.1±2.4 | 140.1±17.3 | 159.4±19.0 | 160.0±14.7 |

| CGS 20 | 8 | 98.9±2.5 | 105.8±1.9 | 91.0±1.8 | 147.1±13.6 | 189.0±17.0* | 170.5±21.9 |

| ACF 100 | 9 | 102.7±2.5 | 103.6±2.0 | 125.2±16.9 | 133.2±17.0 | ||

| ZM | 9 | 104.4±2.8 | 107.2±2.8 | 108.2±2.3 | 133.0±8.2 | 141.3±16.3 | 140.6±16.1 |

| 8-SPT | 9 | 98.3±2.7 | 99.3±3.2 | 99.3±2.8 | 123.7±7.6 | 122.2±6.9 | 118.6±12.6 |

| n |

Upper plateau, % |

Lower plateau, %

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Injection | Recovery | Control | Injection | Recovery | ||

| RSNA | |||||||

| ACF 50 | 8 | 138.7±15.6 | 121.2±7.7 | 15.1±5.7 | 13.1±2.8 | ||

| CGS 2.0 | 9 | 121.7±16.8 | 57.0±7.5* | 138.7±16.1* | 14.5±3.1 | 9.4±1.6 | 8.8±2.2 |

| CGS 20 | 8 | 104.1±8.5 | 40.3±5.2* | 120.8±14.3 | 12.8±5.3 | 8.0±2.3 | 8.2±2.8 |

| ACF 100 | 9 | 117.9±9.7 | 106.6±8.4 | 11.9±3.6 | 11.5±2.8 | ||

| ZM | 9 | 115.9±5.3 | 131.6±6.2 | 116.4±6.2 | 9.9±2.6 | 8.2±2.5 | 6.8±2.5 |

| 8-SPT | 9 | 111.8±6.2 | 120.1±10.2 | 108.5±8.4 | 10.7±2.5 | 11.2±3.6 | 8.0±2.4 |

| ASNA | |||||||

| ACF 50 | 8 | 149.8±6.3 | 160.1±9.6 | 34.4±3.8 | 34.6±4.1 | ||

| CGS 2.0 | 9 | 169.3±18.8 | 186.6±17.2 | 125.7±8.2 | 29.1±3.7 | 27.2±4.6 | 30.3±5.2 |

| CGS 20 | 8 | 174.1±9.1 | 225.7±14.8* | 204.3±20.6 | 27.0±6.0 | 36.7±7.0 | 33.8±5.7 |

| ACF 100 | 9 | 157.9±17.7 | 157.0±16.8 | 32.7±4.9 | 23.7±5.1 | ||

| ZM | 9 | 157.9±7.1 | 161.9±15.6 | 159.4±16.2 | 24.9±3.8 | 20.6±3.8 | 18.8±3.8 |

| 8-SPT | 9 | 152.8±7.8 | 149.8±7.5 | 141.4±11.9 | 29.1±4.7 | 27.6±4.2 | 22.8±5.2 |

| n |

Gmax, %/mmHg |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Injection | Recovery | ||

| RSNA | ||||

| ACF 50 | 8 | 2.9±0.4 | 2.4±0.2 | |

| CGS 2.0 | 9 | 2.4±0.3 | 1.7±0.2 | 3.1±0.4* |

| CGS 20 | 8 | 3.2±0.6 | 0.9±0.2* | 2.6±0.3 |

| ACF 100 | 9 | 2.6±0.3 | 2.4±0.3 | |

| ZM | 9 | 2.2±0.2 | 2.6±0.2 | 2.4±0.2 |

| 8-SPT | 9 | 2.3±0.2 | 2.7±0.3 | 2.5±0.3 |

| ASNA | ||||

| ACF 50 | 8 | 2.1±0.2 | 2.2±0.2 | |

| CGS 2.0 | 9 | 3.0±0.3 | 4.4±0.5 | 3.5±0.5 |

| CGS 20 | 8 | 2.9±0.4 | 4.4±0.6 | 3.2±0.6 |

| ACF 100 | 9 | 3.0±0.6 | 2.8±0.4 | |

| ZM | 9 | 2.6±0.2 | 2.9±0.4 | 3.0±0.4 |

| 8-SPT | 9 | 2.6±0.2 | 3.2±0.3 | 2.9±0.3 |

Data are means ± SE. Range and upper and lower plateaus are expressed as % of resting neural activity normalized to 100% for each nerve. The responses evoked by CGS-21680 were compared with the responses to respective volume control of 50 nl of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACF), whereas the responses to ZM-241385 and 8-SPT were compared with the responses to respective volume control of 100 nl of ACF.

Significant difference vs. control (P < 0.05).

The comparison of relative changes of specific parameters of baroreflex functions caused by microinjections of A2a adenosine receptor agonist (CGS-21680) and respective volume of vehicle (ACF, 50 nl) (Fig. 6 and Table 3) were consistent with changes observed in absolute values (Fig. 5 and Table 2). Briefly, NTS A2a adenosine receptor agonist reciprocally altered range, upper plateau, and Gmax for RSNA and pre-ASNA in a dose-dependent manner (nerve × dose interaction, P = 0.040, P = 0.009, and P = 0.001 for range, upper plateau, and Gmax, respectively). However, baroreflex curves for both nerves were not shifted along MAP axis (compare BP50 across the experimental conditions in Table 3).

Fig. 6.

Changes in range and maximal gain (Gmax) of baroreflex response functions for RSNA and pre-ASNA evoked by bilateral microinjections into the NTS of A2a adenosine receptor agonist (CGS-21680, 2.0 and 20 pmol in 50 nl), selective A2a adenosine receptors antagonist (ZM-241385, 40 pmol in 100 nl), nonselective A1 + A2a adenosine receptors antagonist (8-SPT, 1 nmol in 100 nl), and respective volume controls (ACF, 50 and 100 nl for the agonist and the antagonists, respectively). *P < 0.05 vs. ACF. †P < 0.05 vs. CGS 2.0 pmol. #P < 0.05 vs. RSNA.

Table 3.

Averaged changes in parameters of sigmoidal baroreflex functions for RSNA and pre-ASNA measured before vs. after microinjections into the NTS of A2a adenosine receptor agonist (CGS-21680), adenosine receptor antagonists (ZM-241385 and 8-SPT), and respective volume controls (ACF)

| ACF 50 (n = 8) | CGS 2.0 (n = 9) | CGS 20 (n = 8) | ACF 100 (n = 9) | ZM (n = 9) | 8-SPT (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP50, mmHg | ||||||

| RSNA | 3.3±2.4 | −2.0±1.8 | 4.8±2.2 | 1.4±2.3 | 1.5±1.5 | −1.5±2.1 |

| PreASNA | 0.5±2.7 | −1.0±0.8 | 6.8±2.2 | 0.9±1.8 | 2.8±1.4 | 1.0±1.3 |

| Upper plateau, % | ||||||

| RSNA | −17.5±13.6 | −51.0±5.3* | −63.8±7.5* | −11.2±11.8 | 15.7±9.2 | 8.3±7.8 |

| PreASNA | 10.3±7.7 | 17.3±21.3† | 51.6±12.0*† | −0.9±5.6 | 4.0±14.8 | −3.0±7.6 |

| Lower plateau, % | ||||||

| RSNA | −2.0±3.6 | −5.1±2.6 | −4.8±3.2 | −0.4±3.2 | −1.7±0.7 | 0.5±2.7 |

| PreASNA | 0.3±1.3 | −2.0±3.2 | 9.7±3.5*† | −8.9±5.4 | −4.3±1.7 | −1.5±1.7 |

Data are means ± SE. The responses to CGS-21680 were compared with respective volume control of 50 nl of ACF, and the responses to ZM-241385 and 8-SPT were compared with respective volume control of 100 nl of ACF.

Significnat difference vs. ACF (P < 0.05).

Significant difference vs. RSNA (P < 0.05).

Effects of blockade of NTS adenosine receptor subtypes on baroreflex control of SNA.

Both the selective and nonselective antagonists of adenosine receptor subtypes did not significantly alter baroreflex functions for RSNA and pre-ASNA. The midpoints of the functions (BP50), the lower plateaus, and Gmax expressed in both absolute and relative values remained unaltered (Figs. 5 and 6; Tables 2 and 3). Selective A2a adenosine receptor antagonist (ZM-241385) tended to increase the range and upper plateau for RSNA (P = 0.055 and P = 0.090, respectively), but not for pre-ASNA (Fig. 6 and Table 3). Nonselective blockade of A1 + A2a adenosine receptors did not markedly affect these parameters (Fig. 6, Tables 2 and 3).

The changes in baroreflex function curves caused by stimulation or blockade of NTS A2a adenosine receptors were fully reversible ∼70 min after the microinjections (recovery) (Table 2). Interestingly, the upper plateau and Gmax of baroreflex curves for RSNA not only returned to pre-injection values after the low dose of the agonist but even a small but significant rebound in these parameters was observed (P = 0.047 and P = 0.039 for the upper plateau and Gmax, respectively) (Table 2). Microinjections of vehicle (ACF) did not significantly affect any of the parameters of the baroreflex function curves regardless of injection volume (Table 2).

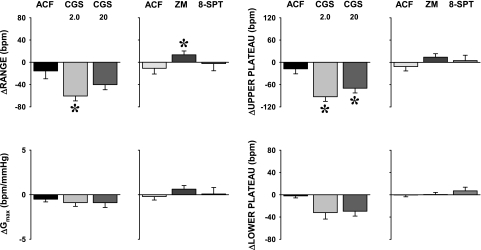

Effects of stimulation or blockade of NTS A2a adenosine receptors on baroreflex control of HR.

The range and upper plateau of HR baroreflex function curves decreased following microinjections into the NTS of the A2a adenosine receptors agonist (range, P = 0.005 and P = 0.088 for 2.0 and 20 pmol of CGS-21680, respectively; upper plateau, P = 0.003 and P = 0.030 for 2.0 and 20 pmol of CGS-21680, respectively) (Fig. 7). In contrast, the selective A2a adenosine receptor blockade increased the range (P = 0.041) and tended to increase the upper plateau (P = 0.102) of HR baroreflex functions. Similar contrasting tendencies following the agonist vs. the antagonist were observed also for Gmax, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. Combined A1 + A2a adenosine receptor blockade as well as microinjections of vehicle (ACF) into the NTS did not significantly affect any of the parameters of HR baroreflex functions (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Effects of activation and blockade of NTS A2a adenosine receptors on baroreflex control of HR. The changes in range, Gmax, and upper and lower plateau of HR baroreflex response functions were evoked by bilateral microinjections into the NTS of A2a adenosine receptor agonist (CGS-21680, 2.0 and 20 pmol in 50 nl), selective A2a adenosine receptor antagonist (ZM-241385, 40 pmol in 100 nl), nonselective A1 + A2a adenosine receptor antagonist (8-SPT, 1 nmol in 100 nl), and respective volume controls (ACF, 50 and 100 nl for the agonist and the antagonists, respectively). *P < 0.05 vs. ACF.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study that assessed the effects of stimulation and blockade of NTS A2a adenosine receptors on the full range of baroreflex control of regional sympathetic outputs and HR. The most important finding is that activation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors evoked reciprocal changes in baroreflex control of renal vs. adrenal sympathetic nerve activity: the gain, range, and upper plateau of baroreflex function curves significantly increased for pre-ASNA, whereas all of these parameters decreased for RSNA in a dose-dependent manner. Despite the marked, reciprocal changes in the baroreflex curves, their positions on the MAP axis (BP50) remained unaltered. In contrast, selective blockade of A2a adenosine receptors as well as nonselective blockade of A1 + A2a adenosine receptors did not significantly alter any parameter of the baroreflex function curves, indicating that these receptors do not provide tonic modulation of baroreflex control of these sympathetic nerves.

The effects of activation of A2a adenosine receptors.

Our previous studies suggested that stimulation of A2a adenosine receptors located in the NTS increased pre-ASNA and decreased RSNA via non-baroreflex mechanisms; the responses persisted after sinoaortic deafferentation plus vagotomy as well as after blockade of ionotropic glutamatergic transmission in the NTS (19, 20). Since stimulation of these receptors caused similar marked changes in baseline sympathetic activity before and after this deafferentation, these studies strongly suggested that baroreflex control of these sympathetic outputs would be differentially altered. We predicted that this change in baseline activity would change the maximal level of SNA with baroreceptor unloading (P1 in Eq. 1). This change in P1 could have several potential consequences on the entire baroreflex function curve. For example, for pre-ASNA, most simply the entire curve could have been shifted upward with corresponding increases in both the upper and lower plateaus with therefore no change in response range, gain, or operating range (the range of MAP over which reflex changes in SNA occur). In contrast, we observed that this elevated pre-ASNA was inhibited to the same low level (P2) in response to similar increases in MAP. With the expanded response range (P1 − P2 in Eq. 1) and little change in the operating range (see Fig. 5), Gmax significantly increased (Eq. 2). Similar but directionally opposite effects were seen in RSNA: P1 decreased with no change in P2, thereby decreasing the response range (P1 − P2), P3 remained essentially unchanged, and therefore Gmax significantly decreased. Thus the changes in baseline and resultant upper plateau combined with sustained ability to markedly suppress nerve activity resulted in large, differential changes in baroreflex maximal range and gain.

The specific mechanism(s) responsible for the differential modulation of baroreflex control of pre-ASNA vs. RSNA following activation of A2a adenosine receptors in the NTS remain unknown. Most likely the sympathetic drive directed to the adrenal medulla and kidney increased and decreased, respectively, at the level of sympathetic premotoneurons located in rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) or intermediolateral column of the spinal cord, i.e., downstream of the inhibitory synapse on RVLM neurons, which closes the baroreflex negative feedback loop. It seems likely that A2a adenosine receptors may facilitate transmission in neural fibers descending from higher structures to the NTS. Specifically, the hypothalamic paraventricular (PVN) and dorsomedial nuclei, which have reciprocal connections with the NTS and may operate via nonglutamatergic transmitters, should be considered (7, 14, 30, 32, 34). The descending pathways may increase baseline pre-ASNA and decrease baseline RSNA via respective activation and inhibition of NTS neurons that directly activate RVLM (for example, NTS neurons mediating chemoreflex responses). Alternatively, A2a adenosine receptors may differentially facilitate and inhibit NTS neurons projecting to the PVN that provide direct descending sympathetic drive to spinal sympathetic neurons and finally to the adrenal and renal nerves, respectively (14).

The effects of blockade of A2a and A1 adenosine receptors.

The selective and nonselective blockade of adenosine receptor subtypes in the NTS did not significantly alter baroreflex function curves for pre-ASNA or RSNA, indicating that these receptors are not involved in the tonic modulation of baroreflex control of these regional sympathetic outputs. The lack of effect of combined blockade of A1 + A2a adenosine receptors on baroreflex functions was somewhat surprising, taking into consideration that activation of A1 adenosine receptors in the NTS exerts powerful resetting/inhibition of baroreflex control of RSNA and pre-ASNA (16). The most likely explanation of this “paradox” is that A1 adenosine receptors operating in the NTS, although capable of inhibiting transmission in the baroreflex pathways, are not active under normal physiological conditions. However, these receptors may be activated when adenosine is released into the NTS in specific physiological or pathological conditions, for example, during the hypothalamic defense response (6, 26, 27), hypoxia, ischemia, and severe hemorrhage (33, 35).

A previous study from our laboratory showed that blockade of both adenosine receptor subtypes in the NTS exaggerated the initial sympathoactivation and attenuated the paradoxical sympathoinhibition and cardiac slowing evoked by severe hemorrhage (24). In contrast, in the present study, the blockade of adenosine receptor subtypes in the NTS did not alter the responses to unloading of arterial baroreceptors with intravenous sodium nitroprusside. The major reason for the differences between these two studies may be that adenosine levels increase in the NTS during severe hemorrhage (33), whereas moderate, slow, and short-lasting decreases in MAP applied in the present study were probably too small to elevate adenosine levels in the NTS effectively.

It has been previously shown, that selective inhibition of NTS A2a adenosine receptors attenuated bradycardia (but not decreases in MAP) evoked by electrical stimulation of the aortic depressor nerve (29). Our present data are in agreement with these findings in this respect in that the blockade of NTS A2a adenosine receptors did not affect control of efferent sympathetic nerve activity. However, we did not see a significant modulation of HR baroreflex function in this setting. Different methods of evoking baroreflex responses and different anesthesia regimes (pentobarbital vs. urethane/chloralose) may be responsible for the differences between the studies.

Limitations

The present study was performed in anesthetized animals; therefore, the responses to unloading of arterial baroreceptors may have been attenuated compared with conscious animals. However, general characteristics of RSNA vs. pre-ASNA baroreflex response curves are similar for conscious and anesthetized rats as our laboratory reviewed previously (15). In this and our laboratory's previous study (16), we used slow ramp changes in MAP to stimulate and unload arterial baroreceptors. Whether this time course is sufficient to allow full expression of sympathetic component of HR responses remains unclear. Nevertheless, the differences between baroreflex response curves for RSNA vs. pre-ASNA were similar to those obtained when steady-state responses were analyzed (Table 1; Ref. 15).

Unfortunately, to our knowledge, available selective A1 adenosine receptor antagonists are not water soluble but dissolve in dimethyl sulfoxide, and this solvent itself produces marked sympathoinhibition upon microinjection into the NTS, which we observed in preliminary experiments. Therefore, in the present study, no selective inhibition of A1 adenosine receptors was performed. Instead, we used a water soluble A1 + A2a adenosine receptor antagonist (8-SPT). The combined blockade allowed only for the indirect evidence for the lack of tonic effects of A1 adenosine receptors on baroreflex control of regional sympathetic function.

Conclusion

Selective stimulation of A2a adenosine receptors located in the NTS did not reset sympathetic and HR baroreflex function curves along the MAP axis. However, maximal gain, range, and upper plateau of baroreflex functions decreased for RSNA, whereas all these parameters increased for pre-ASNA in this setting. The blockade of A2a as well as A1 + A2a adenosine receptors did not alter the baroreflex functions. We conclude that A1 and A2a adenosine receptors located in the NTS do not provide tonic modulation of baroreflex control of regional sympathetic nerve activity. However, phasic activation of A2a adenosine receptors may alter the range and gain of baroreflex control of adrenal vs. renal sympathetic nerve activity via non-baroreflex increases and decreases of sympathetic drive to the adrenal medulla and the kidney, respectively.

Perspectives

Blockade of NTS A1 and A2a adenosine receptors located in the NTS results in very small, if any, cardiovascular and sympathetic responses compared with the large, differential responses evoked by stimulation of these receptors with exogenous ligands (1, 16, 22, 24, 29). This suggests that endogenous adenosine has little modulatory effects under normal physiological conditions. However, large responses to selective exogenous ligands indicate that adenosine has the potential to exert large modulatory effects on neural cardiovascular control when it is released into the NTS during physiological or pathological conditions. To date, it has been shown that A1 adenosine receptors contribute to the pressor component of the stress/hypothalamic defense response (6, 27), whereas both A1 and A2a adenosine receptors contribute to the paradoxical cardiac slowing and sympathoinhibition observed during the hypotensive phase of severe hemorrhagic shock (24). Adenosine is released into the brain, including the NTS, during hypoxia and hypoperfusion, and these disturbances result in large cardiovascular and sympathetic responses (33, 35). The potential neuromodulatory role of adenosine receptors when activated by endogenous adenosine in these pathological situations requires further investigation.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-67814. Dr. T. K. Ichinose is a participant in a research fellowship of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generous gift of Arfonad by Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland. We also gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of J. M. McClure.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barraco RA, El-Ridi MR, Ergene E, Phillis JW. Adenosine receptor subtypes in the brainstem mediate distinct cardiovascular response patterns. Brain Res Bull 26: 59–84, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barraco R, El-Ridi M, Ergene E, Parizon M, Bradley D. An atlas of the rat subpostremal nucleus tractus solitarius. Brain Res Bull 29: 703–765, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barraco RA, O'Leary DS, Ergene E, Scislo TJ. Activation of purinergic subtypes in the nucleus tractus solitarius elicits specific regional vascular response patterns. J Auton Nerv Syst 59: 113–124, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barraco RA, Phillis JW. Subtypes of adenosine receptors in the brainstem mediate opposite blood pressure responses. Neuropharmacology 30: 403–407, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castillo-Meléndez M, Krstew E, Lawrence AJ, Jarrott B. Presynaptic adenosine A2a receptors on soma and central terminals of rat vagal afferent neurons. Brain Res 652: 137–144, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dale N, Gourine AV, Llaudet E, Bulmer D, Thomas T, Spyer KM. Rapid adenosine release in the nucleus tractus solitarii during defence response in rats: real-time measurement in vivo. J Physiol 544: 149–160, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontes MA, Tagawa T, Polson JW, Cavanagh SJ, Dampney RA. Descending pathways mediating cardiovascular response from dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2891–H2901, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kent BB, Drane JS, Blumenstein B, Manning JW. A mathematical model to assess changes in the baroreceptor reflex. Cardiology 57: 295–310, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawrence AJ, Jarrott B. Neurochemical modulation of cardiovascular control in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Prog Neurobiol 48: 21–53, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosqueda-Garcia R, Tseng CJ, Appalsamy M, Robertson D. Modulatory effects of adenosine on baroreflex activation in the brainstem of normotensive rats. Eur J Pharmacol 174: 119–122, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosqueda-Garcia R, Tseng CJ, Appalsamy M, Beck C, Robertson D. Cardiovascular excitatory effects of adenosine in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Hypertension 18: 494–502, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev 50: 413–492, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ribeiro JA, Sebastião AM, De Mendonca A. Adenosine receptors in the nervous system: pathophysiological implications. Prog Neurobiol 68: 377–392, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. Immunohistochemical identification of neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus that project to the medulla or to the spinal cord in the rat. J Comp Neurol 205: 260–272, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scislo TJ, Augustyniak RA, O'Leary DS. Differential arterial baroreflex regulation of renal, lumbar and adrenal sympathetic nerve activity in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 275: R995–R1002, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scislo TJ, Ichinose TK, O'Leary DS. Stimulation of NTS A1 adenosine receptors differentially resets baroreflex control of regional sympathetic outputs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H172–H182, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scislo TJ, Kitchen AM, Augustyniak RA, O'Leary DS. Differential patterns of sympathetic responses to selective stimulation of nucleus tractus solitarius purinergic receptor subtypes. Clin Exp Physiol Pharmacol 28: 120–124, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scislo TJ, O'Leary DS. Activation of adenosine A2a receptors in the nucleus tractus solitarius inhibits renal but not lumbar sympathetic nerve activity. J Auton Nerv Syst 68: 145–152, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scislo TJ, O'Leary DS. Differential control of renal vs. adrenal sympathetic nerve activity by NTS A2a and P2x purinoceptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H2130–H2139, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scislo TJ, O'Leary DS. Differential role of ionotropic glutamatergic mechanisms in responses to NTS P2x- and A2a-receptor stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H2057–H2068, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scislo TJ, O'Leary DS. Mechanisms mediating regional sympathoactivatory responses to stimulation of NTS A1 adenosine receptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H1588–H1599, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scislo TJ, O'Leary DS. Purinergic mechanisms of the nucleus of the solitary tract and neural cardiovascular control. Neurol Res 27: 182–194, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scislo TJ, O'Leary DS. Vasopressin V1 receptors contribute to hemodynamic and sympathoinhibitory responses evoked by stimulation of adenosine A2a receptors in the NTS. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1889–H1898, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scislo TJ, O'Leary DS. Adenosine receptors located in the NTS contribute to renal sympathoinhibition during hypotensive phase of severe hemorrhage in anesthetized rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2453–H2461, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scislo TJ, Tan N, O'Leary DS. Differential role of nitric oxide in regional sympathetic responses to stimulation of NTS A2a adenosine receptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H638–H649, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.St. Lambert JH, Dashwood MR, Spyer KM. Role of brainstem adenosine A1 receptors in the cardiovascular response to hypothalamic defence area stimulation in the anaesthetized rat. Br J Pharmacol 117: 277–282, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.St. Lambert JH, Thomas T, Burnstock G, Spyer KM. A source of adenosine involved in cardiovascular responses to defense area stimulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 272: R195–R200, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao S, Abdel-Rahman A. Neuronal and cardiovascular responses to adenosine microinjection into the nucleus tractus solitarius. Brain Res Bull 32: 407–417, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas T, St Lambert JH, Dashwood MR, Spyer KM. Localization and action of adenosine A2a receptors in regions of the brainstem important in cardiovascular control. Neuroscience 95: 513–518, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson RH, Canteras NS, Swanson LW. Organization of projections from the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus: a PHA-L study in the rat. J Comp Neurol 376: 243–173, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tseng CJ, Biaggoni I, Appalsamy M, Robertson D. Purinergic receptors in the brainstem mediate hypotension and bradycardia. Hypertension 11: 191–197, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Giersbergen PLM, Palkovits M, De Jong W. Involvement of neurotransmitters in the nucleus tractus solitarii in cardiovascular regulation. Physiol Rev 72: 789–824, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Wylen DGL, Park TS, Rubio R, Berne RM. Cerebral blood flow and interstitial fluid adenosine during hemorrhagic hypotension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 255: H1211–H1218, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White JD, Krause JE, McKelvy JF. In vivo biosynthesis and transport of oxytocin, vasopressin, and neurophysins to posterior pituitary and nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neurosci 4: 1262–1270, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan S, Laferriere A, Zhang C, Moss IR. Microdialyzed adenosine in nucleus tractus solitarii and ventilatory response to hypoxia in piglets. J Appl Physiol 79: 405–410, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]