Abstract

This study examined the role of the actin cytoskeleton in Rho-kinase-mediated suppression of the delayed-rectifier K+ (KDR) current in cerebral arteries. Myocytes from rat cerebral arteries were enzymatically isolated, and whole cell KDR currents were monitored using conventional patch-clamp electrophysiology. At +40 mV, the KDR current averaged 19.8 ± 1.6 pA/pF (mean ± SE) and was potently inhibited by UTP (3 × 10−5 M). This suppression was observed to depend on Rho signaling and was abolished by the Rho-kinase inhibitors H-1152 (3 × 10−7 M) and Y-27632 (3 × 10−5 M). Rho-kinase was also found to concomitantly facilitate actin polymerization in response to UTP. We therefore examined whether actin dynamics played a role in the ability of Rho-kinase to suppress KDR current and found that actin disruption using either cytochalasin D (1 × 10−5 M) or latrunculin A (1 × 10−8 M) prevented current modulation. Consistent with our electrophysiological observations, both Rho-kinase inhibition and actin disruption significantly attenuated UTP-induced depolarization and constriction of cerebral arteries. We propose that UTP initiates Rho-kinase-mediated remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton and consequently suppresses the KDR current, thereby facilitating the depolarization and constriction of cerebral arteries.

Keywords: pyrimidine nucleotides, Rho signaling, potassium channels, vascular smooth muscle, delayed-rectifier potassium current

a network of resistance arteries controls the distribution of blood flow through the cerebral circulation. Arterial tone is determined by smooth muscle contractility and is regulated by a number of physiological factors, including metabolic state (9), humoral and neural stimuli (27), intraluminal pressure (10, 17), as well as endothelial factors (16). Many of these stimuli initiate changes in vascular tone via G protein-coupled receptors and the activation of downstream signaling pathways. Effector proteins within such transduction pathways can influence vascular smooth muscle contractility by altering the Ca2+ sensitivity of the myofilaments (29) and/or the activity of ion channels that control membrane potential (Em) and voltage-gated Ca2+ entry (22).

The Rho pathway is a primary signaling pathway regulating vascular smooth muscle contraction. Rho signaling is initiated via receptors coupled to G12/13, resulting in the activation of the small GTPase RhoA and its principal downstream effector Rho-kinase (3, 28). Rho-kinase directly phosphorylates and inactivates myosin light chain phosphatase, ultimately increasing the phosphorylation state of myosin and facilitating contraction (30). Recent studies suggest that Rho-kinase is also capable of modulating ion channels and Em (8, 19). In particular, we found that Rho-kinase was essential to the depolarization and constriction of cerebral arteries in response to agonists such as UTP. Electrophysiological measurements revealed that depolarization involved the Rho-mediated inhibition of a delayed-rectifying K+ (KDR) current (19).

The mechanism by which Rho-kinase suppresses the KDR current remains unclear. One possibility is that Rho-kinase may directly phosphorylate voltage-gated K+ (KV) channels underlying the KDR current to reduce open probability. Currently, however, there is no experimental evidence in support of such a mechanism. Alternatively, Rho-kinase may indirectly mediate KDR channel suppression by targeting the actin cytoskeleton. A number of vascular studies have implicated Rho-kinase in remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton, where it facilitates the polymerization of actin structures (1, 5, 33). Examination of the signaling events underlying this process has revealed that Rho-kinase likely phosphorylates and activates LIM-kinase, an endogenous inhibitor of cofilin, a protein that catalyzes the disassembly of filamentous actin (F-actin; see Ref. 12). Intriguingly, past studies have demonstrated that both Kv1.2 and Kv1.5, key pore-forming subunits of the cerebral arterial KDR current, can couple to actin via the cytoskeletal-binding proteins cortactin and α-actinin2, respectively (11, 21). In consideration of these observations, it is conceivable that Rho-kinase may regulate KDR current by modifying cytoskeletal elements to influence channel activity, thereby producing the electrical and vasomotor responses associated with the constriction of cerebral arteries.

In this study, we examined the roles of Rho signaling and the actin cytoskeleton in enabling vasoconstrictors to suppress the KDR current and elicit arterial depolarization. Electrophysiological measurements confirmed that the KDR current was potently inhibited by UTP through a mechanism dependent on Rho-kinase. We found that Rho-kinase facilitated actin polymerization in response to UTP and that a functional actin cytoskeleton was necessary for KDR current suppression. Furthermore, disrupting the actin cytoskeleton limited the ability of UTP to depolarize and constrict cerebral arteries, similar to the effects of Rho-kinase inhibition. Our findings suggest that Rho-kinase likely modifies actin cytoskeletal structure to reduce KDR channel activity, thereby facilitating the depolarization and constriction of cerebral arteries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal procedures and tissue preparation.

Animal procedures were approved by the University of Calgary Animal Care and Use Committee. Female Sprague-Dawley rats (10–12 wk of age; ∼150 grams) were killed via carbon dioxide asphyxiation. Following death, the brain was isolated and stored in ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4) solution containing (in mM): 138 NaCl, 3 KCl, 10 Na2HPO4, 2 NaH2PO4, 5 glucose, 0.1 CaCl2, and 0.1 MgSO4. Middle cerebral arteries were carefully dissected free of connective tissue and cut into ∼2-mm segments.

Isolation of arterial smooth muscle cells.

Middle cerebral arteries were enzymatically digested to isolate smooth muscle cells. In brief, arterial segments were equilibrated for 10 min at 37°C in an isolation medium containing (in mM): 60 NaCl, 80 sodium glutamate, 5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES with 1 mg/ml albumin (pH 7.4). Tissue samples were subsequently incubated for 15 min in the same medium supplemented with 0.5 mg/ml papain and 1.5 mg/ml dithioerythritol, followed by a 10-min incubation in medium containing 100 μM Ca2+, 0.7 mg/ml type F collagenase, and 0.4 mg/ml type H collagenase. The tissue was then washed repeatedly in ice-cold isolation medium and triturated with a fire-polished pipette to disperse smooth muscle cells. Cell samples were stored in cold isolation medium for electrophysiological study the same day.

Electrophysiology.

Conventional patch-clamp electrophysiology was used to measure KDR currents as previously described (20). Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass and fire-polished to resistances of 4–7 MΩ. Pipettes were then coated with wax to reduce capacitance and backfilled with pipette solution containing (in mM): 110 potassium gluconate, 30 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 5 Na2-ATP, and 1 GTP (pH 7.2). Cells were voltage clamped in a bath solution containing (in mM): 120 NaCl, 3 NaHCO3, 4.2 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). A 1 M NaCl-agar salt-bridge around the reference electrode was used to minimize offset potentials. Whole cell currents were recorded on an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, MDS Analytical Technologies, Mississauga, ON), filtered at 1 kHz, digitized at 5 kHz, and analyzed with Clampfit 8.2 software. Cell capacitance was measured with the cancellation circuitry in the voltage-clamp amplifier and averaged 16.8 ± 0.7 pF. All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–22°C). Cells were voltage-clamped at −60 mV and equilibrated for 15 min before experimentation. Whole cell KDR currents were monitored under control conditions and following the addition of UTP (3 × 10−5 M). To examine Rho-kinase signaling and the function of the actin cytoskeleton, myocytes were preincubated in H-1152 (3 × 10−7 M), Y-27632 (3 × 10−5 M), cytochalasin D (1 × 10−5 M), or latrunculin A (1 × 10−8 M) before the addition of UTP. In several experiments, 5 × 10−3 M 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) was used to ascertain the magnitude of the 4-AP-sensitive KDR current. In general, the net current-voltage (I-V) relationship was determined by measuring peak current at the end of 300-ms voltage commands ranging from −70 to +40 mV. Following each pulse, a voltage step to −40 mV was used to monitor tail currents for analysis of steady-state activation.

Arterial diameter and Em.

Segments of unbranched middle cerebral arteries (∼2 mm in length) were cannulated and mounted in a customized arteriograph chamber (J.B. Pierce Laboratory, New Haven, CT) and superfused with warm (37°C) physiological salt solution (pH 7.4) containing (in mM): 119 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 20 NaHCO3, 1.7 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.6 CaCl2, and 10 glucose. Arteries were maintained under no-flow conditions and at low intraluminal pressure (15 mmHg) to minimize myogenic mechanisms during the examination of agonist responses. Endothelial-dependent mechanisms were eliminated by passing air bubbles through the arterial lumen. Arterial diameter was monitored using an automated edge detection system (IonOptix, Milton, MA). Smooth muscle Em was recorded by inserting a glass microelectrode (120–150 MΩ) filled with 1 M KCl in the vessel wall and assessing the voltage difference across the membrane using an intracellular electrometer (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). Successful cell impalements consisted of: 1) a sharp negative Em deflection upon entry, 2) a stable recording following entry, and 3) a sharp return to baseline upon electrode removal. Cerebral arteries were equilibrated for 30 min at 37°C before experimentation. Before experimentation, the contractile ability of each vessel was determined by a brief exposure to KCl (6 × 10−2 M). To ascertain whether Rho-kinase and the cytoskeleton were involved in UTP-induced constriction, changes in arterial diameter and smooth muscle Em were measured under control conditions, in response to UTP, and following the addition of H-1152, cytochalasin D, or latrunculin A.

Actin polymerization.

Arterial segments were stripped of endothelium and placed in physiological salt solution. Following treatment with UTP and/or H-1152, globular (G)- and F-actin were separated by centrifugation and detected using a commercially available kit (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO). Briefly, arteries were homogenized and centrifuged at low speed (2,000 revolutions/min) for 5 min to spin down unbroken cells and debris. The supernatant was centrifuged at high speed (100,000 g for 60 min at 37°C) to separate F-actin (pellet) and G-actin (supernatant). F-actin was resuspended in 200 μl of ice-cold water and depolymerized using 10 μM cytochalasin D. Samples were then diluted in 4× SDS sample buffer and heated to 95°C for 2 min. Equal volumes of G- and F-actin samples were subsequently separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and probed with rabbit anti-actin polyclonal antibody and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence and quantified using Fujifilm Multigauge3.1 software. G-actin was additionally quantified with respect to SM-22. Actin blots were reprobed using goat anti-SM-22 antibody and HRP-conjugated anti-goat secondary antibody. SM-22 was subsequently visualized, quantified, and used to standardize G-actin content (i.e., G-actin/SM-22).

Chemicals, drugs, and enzymes.

H-1152, Y-27632, cytochalasin D, and latrunculin A were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Buffer reagents, collagenases (type F and H), UTP, and 4-AP were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Papain was acquired from Worthington (Lakewood, NJ).

Statistical analyses.

Data are expressed as means ± SE, and n indicates the number of vessels or cells. Paired t-tests were performed to statistically compare the effects of a given condition/treatment on arterial diameter, Em, or whole cell current. If more than two conditions or treatments were being compared, a repeated-measures ANOVA was used. When appropriate, a Tukey-Kramer pairwise comparison was used for post hoc analysis. P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

KDR current and Rho-kinase regulation.

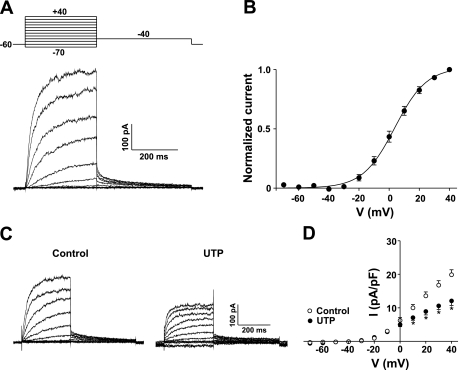

To better define the mechanisms enabling pyrimidine nucleotides to inhibit the KDR current, we began our investigation by isolating the current and again demonstrating its susceptibility to UTP inhibition. With the use of whole cell patch-clamp electrophysiology, the KDR current was readily identified in smooth muscle cells isolated from rat cerebral arteries. As shown in Fig. 1A, KDR currents were measured by stepping to a series of increasingly positive potentials from a holding potential of −60 mV. The current typically activated at potentials positive to −40 mV and averaged 19.8 ± 1.6 pA/pF at +40 mV. To assess voltage dependence, tail currents were measured at −40 mV to obtain an accurate indication of the proportion of channels open following a given voltage step. Plotting normalized tail currents against voltage shows activation was detectable at voltages positive to −40 mV and was near maximal at +30 mV (Fig. 1B). Applying a Boltzmann function to the data establishes a voltage for half-maximal activation of 3.7 ± 1.0 mV, consistent with previously reported values for the KDR current in cerebral arterial smooth muscle (19, 20).

Fig. 1.

Delayed-rectifier K+ (KDR) current suppression by UTP in smooth muscle cells isolated from rat cerebral arteries. A: voltage (V) paradigms (top left) were designed to measure steady-state activation. Representative recording of whole cell KDR current (bottom left). B: plot of steady-state activation. Solid line is a Boltzmann distribution function with half-maximal activation occurring at 3.7 ± 1.0 mV (n = 10). C: representative recordings of KDR current before and after the addition of UTP (3 × 10−5 M). D: net current (I)-V relationship (right) under control conditions and in the presence of UTP (n = 8 experiments). *Statistical difference from control.

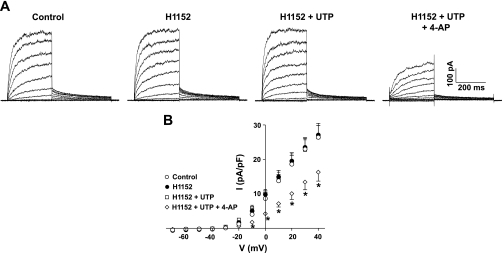

KDR current amplitude was reduced significantly following the application of UTP (Fig. 1, C and D). As evident in the I-V relationships, 3 × 10−5 M UTP inhibited the KDR current by 37.0% as measured at +40 mV. This suppression was not associated with changes in whole cell capacitance nor was it attributable to current rundown over time (19). To emphasize that modulation occurs through a Rho-kinase pathway, we measured the effect of UTP following Rho-kinase inhibition (Fig. 2). Representative recordings in Fig. 2A show that KDR suppression did not occur in the presence of 3 × 10−7 M H-1152, resulting in the absence of any significant net change in the I-V relationship of KDR (Fig. 2B). The subsequent addition of the KV channel blocker 4-AP (5 × 10−3 M) significantly reduced the current (Fig. 2, A and B), verifying the presence of channels known to be regulated by UTP (19). Similar to the effect of H-1152, Rho-kinase inhibition using Y-27632 (3 × 10−5 M) prevented KDR current suppression (n = 3; data not shown).

Fig. 2.

KDR current suppression by UTP is dependent on Rho-kinase activity. A: representative recordings of the KDR current under control conditions, in the presence of H-1152 (3 × 10−7 M) ± UTP (3 × 10−5 M), and following the addition of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; 5 × 10−3 M). Voltage protocol as in Fig. 1. B: net I-V relationship in the presence of H-1152 ± UTP and following the addition of 4-AP (n = 6). *Statistical difference from control.

Rho-kinase modulation of the actin cytoskeleton and KDR.

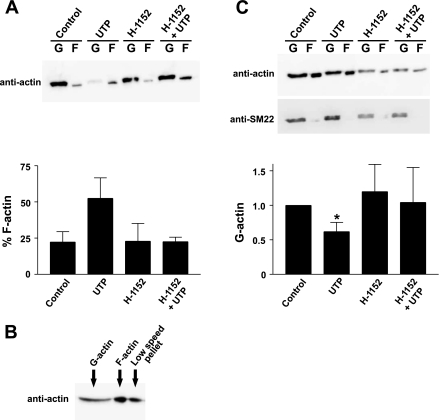

To test whether the regulation of KDR current may sequentially involve activation of Rho-kinase and changes in actin structure, we first assayed the state of actin in cerebral arteries following agonist application. Stimulation of unpressurized cerebral arteries with UTP (3 × 10−5 M) induced actin polymerization, eliciting a twofold increase in the percentage of filamentous (F) actin (Fig. 3A). Although Rho-kinase inhibition had no significant effect on its own, pretreatment of vessels with 3 × 10−6 M H-1152 prevented UTP-induced polymerization. Although these findings suggest that Rho-kinase is key to the formation of actin filaments during smooth muscle contraction, we were concerned by the markedly low percentage of F-actin observed under control conditions. Further examination revealed that a significant amount of F-actin was present in the pellet fraction following the low-speed centrifugation step used to remove cellular debris (Fig. 3B), introducing a potential source of error. To more accurately determine changes in actin, we therefore standardized G-actin to SM-22, a stable protein also found within the cytosolic fraction. As shown in Fig. 3C, normalized G-actin content was reduced significantly following stimulation of vessels with UTP. In contrast, this effect was not observed when arteries were pretreated with H-1152, verifying that Rho-kinase is essential to the actin dynamics associated with agonist stimulation.

Fig. 3.

UTP induces polymerization of smooth muscle actin through a mechanism dependent on Rho-kinase. A: Western blot (top) and summary data (bottom) showing the effect of H-1152 on actin polymerization in cerebral arteries (n = 3). Experiments were performed on unpressurized arteries superfused with physiological salt solution. B: Western blot demonstrating the detection of actin in high-speed fractions [globular (G)- and filamentous (F)-actin] and in the pellet following low-speed centrifugation. C: Western blots detecting actin were reprobed using anti-SM-22 antibody (top). Bottom: summary data showing the effect of UTP (3 × 10−5 M) ± H-1152 (3 × 10−6 M) on G-actin content after G-actin was standardized to SM-22 and normalized to control (n = 3). *Statistical difference from control.

We subsequently monitored the effect of UTP on KDR current following actin disruption. To interfere with actin, we first used cytochalasin D, an agent known to depolymerize actin by capping, as well as severing, filamentous actin. Figure 4, A and C, shows that the addition of cytochalasin D (1 × 10−5 M), despite not having a significant impact on baseline current, completely prevented current suppression by UTP. Similar results were obtained when the experiment was repeated with latrunculin A, which binds globular actin and prevents its incorporation into filaments (Fig. 4B). The mean data shows that latrunculin A (1 × 10−8 M) did not affect baseline current amplitude but prevented inhibition by UTP (Fig. 4D). The substantial block subsequently achieved by 4-AP demonstrates that 4-AP-sensitive channels are present, but not regulated, following actin disruption.

Fig. 4.

Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton attenuates the suppression of KDR current by UTP. A: representative recordings of the KDR current under control conditions and in the presence of cytochalasin D (Cyt D; 1 × 10−5 M) ± UTP (3 × 10−5 M). Voltage protocol as in Fig. 1. B: representative recordings of the KDR current under control conditions, in the presence of latrunculin A (Lat A; 1 × 10−8 M) ± UTP (3 × 10−5 M), and following the addition of 4-AP (5 × 10−3 M). C: net I-V relationship in the presence of cytochalasin D ± UTP (n = 6). D: net I-V relationship in the presence of latrunculin A ± UTP and following the addition of 4-AP (n = 6). *Statistical significance from control.

Rho-kinase-mediated depolarization and constriction of cerebral arteries.

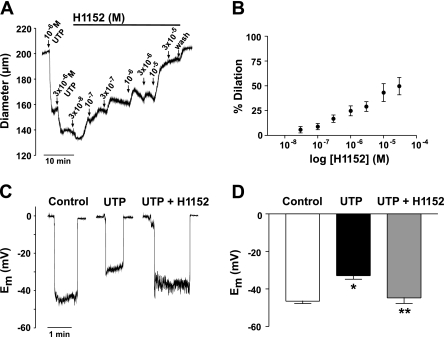

Given the electrophysiological observations, it would be expected that interfering with either Rho signaling or actin dynamics would limit the ability of UTP to depolarize and constrict cerebral arteries. As shown in Fig. 5, A and B, arteries preconstricted with UTP dilated to the Rho-kinase inhibitor H-1152 in a concentration-dependent manner. The effect of H-1152 was noticeable at 1 × 10−7 M and induced nearly 50% dilation at 3 × 10−4 M. We subsequently measured the effect of Rho-kinase inhibition on the ability of UTP to depolarize cerebral smooth muscle. As shown in Fig. 5, C and D, UTP typically depolarized cerebral arteries from a resting Em of −46.5 ± 1.2 to −32.9 ± 1.9 mV. H-1152 (1 × 10−5 M) significantly attenuated the depolarization by 12 mV, since Em was measured at −44.8 ± 3.0 mV. Because arteries were stripped of endothelium and maintained at low pressure (15 mmHg), the effects of H-1152 on diameter and Em were not the result of effects on myogenic tone or endothelial-dependent mechanisms.

Fig. 5.

UTP-induced depolarization and constriction is dependent on Rho-kinase activity. A: representative trace showing the effects of increasing concentration of H-1152 on an artery preconstricted with UTP. B: summary data of the concentration-dependent effect of H-1152 on a preconstricted artery (n = 6). C: representative recordings of smooth muscle membrane potential (Em) measured under control conditions and in the presence of UTP ± H-1152 (1 × 10−5 M). D: summary data of Em measured under control conditions and in the presence of UTP ± H-1152 (n = 6). Asterisks indicate statistical differences from control (*) and UTP (**).

Role of the actin cytoskeleton in depolarization and constriction.

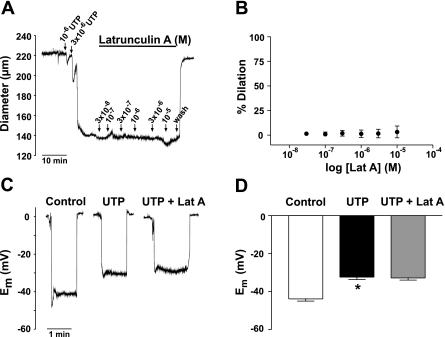

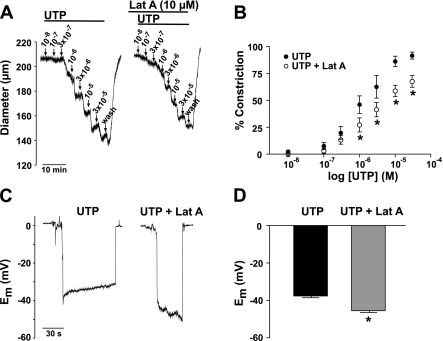

Actin disruption dilated cerebral arteries preconstricted by UTP. As shown in Fig. 6, A and B, 50% dilation was achieved with 3 × 10−6 M cytochalasin D and 1 × 10−5 M induced a near complete return to baseline diameter. Em recordings revealed that cytochalasin D also reversed the depolarization induced by UTP, shifting smooth muscle Em from −33.2 ± 1.2 to −44.6 ± 3.2 mV (Fig. 6, C and D). In sharp contrast, when we repeated the previous experiment using latrunculin A, we found it affected neither the constriction nor the depolarization associated with UTP (Fig. 7). Because latrunculin A disrupts actin by binding G-actin and preventing its incorporation into growing filaments, effects on diameter and electrical responses may not have been detected because agonist-induced alterations in cytoskeletal structure were complete. To address this possibility, we tested whether pretreatment with latrunculin A may have an effect on agonist responses. The experiment shown in Fig. 8A shows that a 30-min preincubation with latrunculin A (1 × 10−5 M) indeed attenuated the concentration-dependent constriction to UTP. The mean data indicate a significant rightward shift in the sensitivity to UTP (Fig. 8B). When vessels were pretreated with latrunculin A, depolarization to UTP was also significantly attenuated (−37.6 ± 0.9 to −45.5 ± 0.9 mV; Fig. 8, C and D). The above findings are consistent with the idea that disruption of the actin cytoskeleton with cytochalasin D or latrunculin A may limit the extent to which KDR current inhibition contributes to depolarization and constriction.

Fig. 6.

Effect of cytochalasin D on UTP-induced depolarization and constriction. A: representative trace showing the effects of increasing concentration of cytochalasin D on an artery preconstricted with UTP. B: summary data of the concentration-dependent effect of cytochalasin D on a preconstricted artery (n = 6). C: representative recordings of smooth muscle Em measured under control conditions and in the presence of UTP ± cytochalasin D (1 × 10−5 M). D: summary data of Em measured under control conditions and in the presence of UTP ± cytochalasin D (n = 6). Asterisks denote statistical differences from control (*) and UTP (**).

Fig. 7.

Effect of latrunculin A on UTP-induced depolarization and constriction. A: representative trace showing the effects of increasing concentration of latrunculin A on an artery preconstricted with UTP. B: summary data of the concentration-dependent effect of latrunculin A on a preconstricted artery (n = 6). C: representative recordings of smooth muscle Em measured under control conditions and in the presence of UTP ± latrunculin A (1 × 10−5 M). D: summary data of Em measured under control conditions and in the presence of UTP ± latrunculin A (n = 6). *Statistical difference from control.

Fig. 8.

Effect of latrunculin A pretreatment on UTP-induced depolarization and constriction. A: representative trace showing the concentration-dependent constriction to UTP in the presence and absence of latrunculin A. B: summary data of arterial constriction to UTP in the presence or absence of latrunculin A (n = 6). C: representative recordings of smooth muscle Em measured in the presence of UTP ± pretreatment with latrunculin A (1 × 10−5 M). D: summary data of Em measured in the presence of UTP ± pretreatment with latrunculin A (n = 6). *Statistical difference.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we further define the mechanisms by which pyrimidine nucleotides elicit constriction of cerebral arteries to effectively reduce blood flow. Electrophysiological examination of smooth muscle cells isolated from cerebral arteries revealed a KDR current that was potently inhibited by UTP through a signaling mechanism involving Rho-kinase. On the basis of previous reports, we questioned whether suppression of the KDR current was dependent on the actin cytoskeleton. We found that Rho-kinase activity was requisite for UTP-induced actin polymerization in cerebral arteries and that interfering with actin dynamics prevented Rho-kinase from regulating the KDR current. The initiation of Rho-kinase-mediated alterations in the cytoskeleton and subsequent inhibition of the KDR current appears to be central in enabling agonists such as UTP to depolarize and constrict cerebral arteries.

KDR current and rho-kinase regulation.

Pyrimidine nucleotides, such as UTP, are endogenous signaling compounds secreted by a number of cell types found in the blood and within the arterial wall (18). When released in close proximity to vascular smooth muscle, pyrimidine nucleotides bind to the P2Y class of receptors to initiate a sustained constriction (7, 15). Cerebral arteries express P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 receptor subtypes, and we have previously investigated the mechanisms enabling UTP to constrict these vessels (19). Detailed examination revealed that smooth muscle depolarization and subsequent voltage-gated Ca2+ entry contributed substantially to constriction. We further determined that depolarization was facilitated by the inhibition of an outward K+ conductance, the KDR current. Consistent with the view that P2Y receptors can couple to G12/13 trimeric G proteins to initiate Rho signaling (26), Rho-kinase activity was found to be essential to the suppression of KDR current and to the associated depolarization and constriction.

In the present study, we have verified that UTP elicits KDR current inhibition via Rho-kinase. Using conventional whole cell patch-clamp electrophysiology, we readily identified a current with features characteristic of a KDR current: 1) slow time-dependent activation in response to depolarizing potentials, 2) slow deactivation kinetics, and 3) a voltage for half-maximal activation of 3.7 ± 1.0 mV. Additionally, both 4-AP-sensitive and -insensitive components could be distinguished. The 4-AP-sensitive conductance likely includes a heteromultimeric channel formed by Kv1.2, Kv1.5, and Kv1.6 subunits (24) and is of particular relevance, since it is the conductance that is regulated by UTP (19). The 4-AP-insensitive current appears to be less susceptible to agonist regulation in the cerebral circulation and may consist of members of Kv2 and Kv7 subfamilies (2, 23).

The stimulation of voltage-clamped cerebral myocytes with UTP elicited KDR current suppression with a magnitude and time course similar to earlier reports. We have previously implicated Rho signaling in this response, since suppression was abolished following the targeted inactivation of RhoA and Rho-kinase by C-3 exoenzyme and Y-27632, respectively (19). Recent studies have demonstrated that Y-27632 can affect protein kinase C-δ activity (6, 31), a secondary effect that would complicate our previous interpretation of the ability of Y-27632 to prevent KDR current suppression and arterial depolarization. To address this concern, we opted to use H-1152, since it has been reported to be a more selective and potent Rho-kinase inhibitor (25). H-1152 was found to be more potent than Y-27632, with a concentration of 3 × 10−7 M consistently preventing KDR current suppression in isolated cells. Although both Y-27632 and H-1152 act by competing with ATP binding to Rho-kinase, the comparable effects of two structurally distinct compounds strengthen the evidence that Rho-kinase is essential in enabling UTP to elicit KDR current suppression. It is apparent that, in addition to the well-described inhibition of myosin phosphatase in Ca2+ sensitization, Rho-kinase can also impact ion channel activity.

The actin cytoskeleton and KDR current suppression.

Although a dependence on Rho signaling is clear, we questioned the mechanism by which Rho-kinase may influence KDR channel activity. A number of vascular studies have implicated the Rho pathway in the regulation of the cytoskeletal structure, where it can influence both the assembly and disassembly of actin filaments (1, 5, 12, 33). RhoA has been shown to promote actin polymerization by activating profilin, a protein that mediates the addition of actin monomers onto the growing (+) end of filaments (12). Conversely, actin polymerization can also be achieved through a reduced rate of disassembly at the pointed (−) end of actin filaments, and this is thought to occur upon activation of the Rho-kinase/LIM-kinase/cofilin pathway (12). We assayed the state of actin and found that Rho-kinase indeed facilitates polymerization in intact cerebral arteries stimulated with UTP. Following stimulation, the percentage of F-actin increased, and separate analyses of the G-actin content revealed a corresponding decrease. These effects were not observed when arteries were preincubated with a Rho-kinase inhibitor before agonist application. It may be predicted that such alterations in actin structure would not only impact smooth muscle cell morphology and force generation, but would likely influence the localization and/or regulation of membrane proteins and signaling complexes, including ion channels. Intriguingly, several KV channel subtypes thought to contribute to the KDR current, namely Kv1.2 and Kv1.5, have been shown to be capable of associating with actin through cytoskeleton-binding proteins (11, 21).

In the present study, pharmacological disruption of actin with either cytochalasin D or latrunculin A effectively abolished the ability of UTP to suppress KDR current. Therefore, an intact actin cytoskeleton appears essential to Rho-kinase inhibition of the current. Because Rho-kinase promotes actin polymerization, it is likely that alterations in actin structure are associated with changes in cytoskeleton-channel interactions that reduce channel activity. The exact nature of these interactions, and the possible involvement of intermediary proteins, has yet to be resolved. Suppression of the KDR current could also involve channel internalization rather than changes in channel gating. Several reports have indicated that vascular KDR channels may undergo translocation from the membrane to the cytosol in response to agonists (4, 13). The translocation of KDR channels would reduce current density and facilitate arterial depolarization.

Rho-kinase-mediated depolarization and constriction.

The functional impact of the preceding mechanism was evident in arterial constrictions to UTP, which displayed a dependence on both Rho-kinase activity and the actin cytoskeleton. Treatment of intact cerebral arteries with H-1152 dilated arteries in a concentration-dependent manner. However, given that Rho-kinase inhibition limits actin polymerization in smooth muscle, part of this dilation is likely because of the disruption of force-generating structures. We therefore directly measured smooth muscle Em to assess changes in ion channel activity in the absence of effects linked to the force generation. These measurements indicated that Rho-kinase inhibition indeed attenuated UTP-induced depolarization, consistent with an increase in outward conductance that would accompany the relief of KDR current suppression. It should be noted that a significant constriction (∼50%) remained following Rho-kinase inhibition, indicating that at least one additional signaling pathway is initiated during constriction to pyrimidine nucleotides. This is not surprising given that UTP is known to elicit Ca2+ waves (14), events that have not shown a dependence on Rho signaling.

Similar to the effects of Rho-kinase inhibition, actin disruption using cytochalasin D or latrunculin A limited the electrical and vasomotor responses to UTP. These findings are congruent with the electrophysiological measurements indicating outward KDR currents are not suppressed significantly under analogous conditions. Intriguingly, the impact of latrunculin A on cerebral vessels depended on the order of application. To observe an effect, vessels had to be pretreated with latrunculin A before UTP stimulation. The application of latrunculin A following the agonist response elicited neither a change in Em nor diameter. We believe these observations reflect the distinct mechanisms by which cytochalasin D and latrunculin A interfere with actin. Cytochalasins are known to cap the growing (+) barbed end of actin and cleave F-actin to promote depolymerization, the effects of which become apparent during the sustained response to UTP. In contrast, latrunculin A disrupts actin by binding to globular actin and preventing its incorporation into filaments. Because the recruitment of G-actin into filaments is likely complete when a sustained constriction is attained, the subsequent addition of latrunculin would be expected to target residual G-actin with little effect. Although the interconversion between G- and F-actin is likely a dynamic process that may promote gradual depolymerization, we did not observe any time-dependent effect of latrunculin over the course of 1–2 h.

Physiological implications.

Our findings indicate that Rho-kinase likely suppresses the KDR current by eliciting reorganization of the cortical actin cytoskeleton. We propose that such a mechanism enables UTP to depolarize smooth muscle, thereby facilitating voltage-gated Ca2+ entry and the constriction of cerebral arteries. We have previously hypothesized that pyrimidine nucleotides activate Rho-kinase through the sequential activation of P2Y receptors, G12/13, p115 RhoGEF, and RhoA (19). Therefore, cytoskeletal remodeling and KDR current suppression are likely to similarly facilitate depolarization and constriction to UDP (19). Furthermore, this type of regulation may not be specific to P2Y receptor agonists, since constriction of cerebral arteries to the thromboxane mimetic U-46619 also involves Rho-kinase-dependent depolarization (19). Moreover, U-46619 elicits a significant suppression of the KDR current (32), conceivably involving a mechanism analogous to UTP inhibition. A role for Rho-kinase in the voltage-dependent constriction of mesenteric arteries has also been reported (8), suggesting the capacity of Rho-kinase to regulate electromechanical coupling extends beyond the cerebral circulation. More detailed examination is required to determine whether the modulation of ion channels and Em in these tissues is similarly dependent on cytoskeletal remodeling.

In closing, it is clear that the initiation of Rho signaling can alter cerebrovascular tone through multiple, interconnected pathways. In addition to sensitizing the contractile machinery to available Ca2+, Rho-kinase plays an essential role in remodeling the actin cytoskeleton during agonist responses. Our present findings suggest that this influence on actin dynamics enables Rho-kinase to effectively regulate the KDR current and impact electromechanical coupling.

GRANTS

Operational support was provided by the Canadian Institute of Health Research. K. D. Luykenaar is supported by a doctoral research award provided by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albinsson S, Nordstrom I, Hellstrand P. Stretch of the vascular wall induces smooth muscle differentiation by promoting actin polymerization. J Biol Chem 279: 34849–34855, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amberg GC, Santana LF. Kv2 channels oppose myogenic constriction of rat cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C348–C356, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattacharyya R, Wedegaertner PB. Characterization of G alpha 13-dependent plasma membrane recruitment of p115RhoGEF. Biochem J 371: 709–720, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cogolludo A, Moreno L, Lodi F, Frazziano G, Cobeño L, Tamargo J, Perez-Vizcaino F. Serotonin inhibits voltage-gated K+ currents in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells: role of 5-HT2A receptors, caveolin-1, and KV15 channel internalization Circ Res 98: 931–938, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corteling RL, Brett SE, Yin H, Zheng XL, Walsh MP, Welsh DG. The functional consequence of RhoA knockdown by RNA interference in rat cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H440–H447, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eto M, Kitazawa T, Yazawa M, Mukai H, Ono Y, Brautigan DL. Histamine-induced vasoconstriction involves phosphorylation of a specific inhibitor protein for myosin phosphatase by protein kinase C α and δ isoforms. J Biol Chem 276: 29072–29078, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Velasco G, Sanchez M, Hidalgo A, Garcia de Boto MJ. Pharmacological dissociation of UTP- and ATP-elicited contractions and relaxations in isolated rat aorta. Eur J Pharmacol 294: 521–529, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghisdal P, Vandenberg G, Morel N. Rho-dependent kinase is involved in agonist-activated calcium entry in rat arteries. J Physiol 551: 855–867, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harder DR, Alkayed NJ, Lange AR, Gebremedhin D, Roman RJ. Functional hyperemia in the brain: hypothesis for astrocyte-derived vasodilator metabolites. Stroke 29: 229–234, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harder DR, Gilbert R, Lombard JH. Vascular muscle cell depolarization and activation in renal arteries on elevation of transmural pressure. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F778–F781, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hattan D, Nesti E, Cachero TG, Morielli AD. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Kv1.2 modulates its interaction with the actin-binding protein cortactin. J Biol Chem 277: 38596–38606, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hellstrand P, Albinsson S. Stretch-dependent growth and differentiation in vascular smooth muscle: role of the actin cytoskeleton. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 83: 869–875, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishiguro M, Morielli AD, Zvarova K, Tranmer BI, Penar PL, Wellman GC. Oxyhemoglobin-induced suppression of voltage-dependent K+ channels in cerebral arteries by enhanced tyrosine kinase activity. Circ Res 99: 1252–1260, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaggar JH, Nelson MT. Differential regulation of Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves by UTP in rat cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1528–C1539, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juul B, Plesner L, Aalkjaer C. Effects of ATP and UTP on [Ca2+]i, membrane potential and force in isolated rat small arteries. J Vasc Res 29: 385–395, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimura M, Dietrich HH, Dacey RG. Nitric oxide regulates cerebral arteriolar tone in rats. Stroke 25: 2227–2234, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knot HJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J Physiol 508: 199–209, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC. UTP as an extracellular signaling molecule. News Physiol Sci 16: 1–5, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luykenaar KD, Brett SE, Wu BN, Wiehler WB, Welsh DG. Pyrimidine nucleotides suppress KDR currents and depolarize rat cerebral arteries by activating Rho kinase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H1088–H1100, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luykenaar KD, Welsh DG. Activators of the PKA and PKG pathways attenuate RhoA-mediated suppression of the KDR current in cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H2654–H2663, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maruoka ND, Steele DF, Au BP, Dan P, Zhang X, Moore ED, Fedida D. Alpha-actinin-2 couples to cardiac Kv1.5 channels, regulating current density and channel localization in HEK cells. FEBS Lett 473: 188–194, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 268: C799–C822, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohya S, Sergeant GP, Greenwood IA, Horowitz B. Molecular variants of KCNQ channels expressed in murine portal vein myocytes: a role in delayed rectifier current. Circ Res 92: 1016–1023, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plane F, Johnson R, Kerr P, Wiehler W, Thorneloe K, Ishii K, Chen T, Cole W. Heteromultimeric Kv1 channels contribute to myogenic control of arterial diameter. Circ Res 96: 216–224, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sasaki Y, Suzuki M, Hidaka H. The novel and specific Rho-kinase inhibitor (S)-(+)-2-methyl-1-[(4-methyl-5-isoquinoline)sulfonyl]-homopiperazine as a probing molecule for Rho-kinase-involved pathway. Pharmacol Therap 93: 225–232, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sauzeau V, Le JH, Cario-Toumaniantz C, Vaillant N, Gadeau AP, Desgranges C, Scalbert E, Chardin P, Pacaud P, Loirand G. P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 receptors are coupled to Rho and Rho kinase activation in vascular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1751–H1761, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Si ML, Lee TJ. Alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on cerebral perivascular sympathetic nerves mediate choline-induced nitrergic neurogenic vasodilation. Circ Res 91: 62–69, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Signal transduction by G-proteins, rho-kinase and protein phosphatase to smooth muscle and non-muscle myosin II. J Physiol 522: 177–185, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Signal transduction and regulation in smooth muscle. Nature 372: 231–236, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swärd K, Mita M, Wilson DP, Deng JT, Susnjar M, Walsh MP. The role of RhoA and Rho-associated kinase in vascular smooth muscle contraction. Curr Hypertens Rep 5: 66–72, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson DP, Susnjar M, Kiss E, Sutherland C, Walsh MP. Thromboxane A2-induced contraction of rat caudal arterial smooth muscle involves activation of Ca2+ entry and Ca2+ sensitization: Rho-associated kinase-mediated phosphorylation of MYPT1 at Thr-855, but not Thr-697. Biochem J 389: 763–774, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu BN, Luykenaar KD, Brayden JE, Giles WR, Corteling RL, Wiehler WB, Welsh DG. Hyposmotic challenge inhibits inward rectifying K+ channels in cerebral arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1085–H1094, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeidan A, Nordstrom I, Albinsson S, Malmqvist U, Swärd K, Hellstrand P. Stretch-induced contractile differentiation of vascular smooth muscle: sensitivity to actin polymerization inhibitors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C1387–C1396, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]