Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Interactive voice response (IVR) systems that collect survey data using automated, push-button telephone responses may be useful to monitor patients’ pain and function at home; however, its equivalency to other data collection methods has not been studied.

OBJECTIVES:

To study the data equivalency of IVR measurement of pain and function to live telephone interviewing.

METHODS:

In a prospective cohort study, 547 working adults (66% male) with acute back pain were recruited at an initial outpatient visit and completed telephone assessments one month later to track outcomes of pain, function, treatment helpfulness and return to work. An IVR system was introduced partway through the study (after the first 227 participants) to reduce the staff time necessary to contact participants by telephone during nonworking hours.

RESULTS:

Of 368 participants who were subsequently recruited and offered the IVR option, 131 (36%) used IVR, 189 (51%) were contacted by a telephone interviewer after no IVR attempt was made within five days, and 48 (13%) were lost to follow-up. Those with lower income were more likely to use IVR. Analysis of outcome measures showed that IVR respondents reported comparatively lower levels of function and less effective treatment, but not after controlling for differences due to the delay in reaching non-IVR users by telephone (mean: 35.4 versus 29.2 days).

CONCLUSIONS:

The results provided no evidence of information or selection bias associated with IVR use; however, IVR must be supplemented with other data collection options to maintain high response rates.

Keywords: Acute back pain, Home assessment of pain and function, Interactive voice response

Abstract

CONTEXTE :

Les systèmes de réponse vocale interactifs (RVI) servant à la collecte de données d’enquête au moyen de téléphones à boutonspoussoirs peuvent se montrer utiles pour la surveillance des dorsalgies et de fonctionnement des patients à domicile, mais leur équivalence avec d’autres méthodes de collecte de données n’a jamais fait l’objet d’études.

BUT :

L’étude avait pour but d’examiner l’équivalence des données recueillies par un système RVI sur la mesure de la douleur et du fonctionnement des patients avec celles obtenues par des entrevues téléphoniques classiques.

MÉTHODE :

Des travailleurs adultes (n=547; 66 % d’hommes) souffrant de dorsalgie aiguë ont été sélectionnés au moment de la première consultation externe pour participer à une étude prospective, de cohortes, et ils ont répondu à une évaluation téléphonique, un mois plus tard, en vue d’un suivi sur la douleur, le fonctionnement, l’efficacité du traitement et le retour au travail. Un système RVI a été mis en place en cours de route (après la sélection de 227 participants) afin de diminuer le temps nécessaire au personnel pour joindre les participants par téléphone, hors des heures de travail.

RÉSULTATS :

D’autres participants (n=368) ont été sélectionnés par la suite et on leur a offert la possibilité d’utiliser le système RVI; 131 (36 %) l’ont fait; 189 (51 %) ont été joints par téléphone après l’absence de tentative en cinq jours et 48 (13 %) n’ont pas participé au suivi. Les sujets ayant des revenus moins élevés étaient plus susceptibles d’utiliser le système RVI. L’analyse des mesures de résultats a révélé que les personnes qui avaient utilisé le système RVI avaient fait état de degrés moins élevés de fonctionnement et d’efficacité du traitement par rapport aux autres, mais l’écart est disparu après la neutralisation du délai nécessaire pour joindre les non-utilisateurs du système RVI par téléphone (moyenne : 35,4 contre 29,2 jours).

CONCLUSIONS :

Les résultats n’ont pas révélé de biais de sélection ou d’information associé à l’utilisation du système RVI; toutefois, les données recueillies par le système doivent être complétées par d’autres méthodes de collecte afin de fournir des taux élevés de réponse.

Periodic monitoring of symptoms by telephone or postal questionnaire has been a common method of outcome assessment in studies of pain treatment and rehabilitation. Technological advances have provided new methods for collecting survey data, including electronic questionnaires (1), hand-held personal digital assistants (2), internet-based questionnaires (3), computer-assisted telephone interviewing (4) and interactive voice response (IVR) systems (5). While previous studies have established the validity of pain assessment using postal questionnaires (6), electronic questionnaires (1) and live telephone interviewing (7), the equivalency of IVR has not been studied.

IVR systems collect survey data by telephone using automated, interactive scripts and push-button or recorded responses. Calls can be respondent-initiated or system-initiated, and respondents are led through an interactive menu that provides instructions, poses a set of standardized, prerecorded questions, and specifies response choices. IVR eliminates the human resources necessary to reach respondents at home, conduct telephone interviews and enter data. For respondentinitiated calls, the IVR system can be accessed at any time of day or night, allowing access to hard-to-reach groups (8). IVR is also well-suited for assessing health information that is potentially stigmatizing, for example, alcohol consumption (5,9) or medication compliance (10), because it may reduce embarrassment or other unintended observer effects. It has been suggested that IVR systems could be designed for clinical use to monitor symptoms without requiring office visits, to access and update patient information, to facilitate shared decision-making and to provide self-management instructions (11,12).

One potential application of IVR is home monitoring of early recovery from acute back pain. Although the majority of back pain episodes resolve within one month and require minimal intervention, a subset of cases with a seemingly benign clinical presentation at intake can progress to chronic or recurrent pain (13,14). Thus, one recommended strategy for improving back pain outcomes has been the early identification of patients at greatest risk for persistent pain and disability (15). A growing number of prospective cohort studies (16,17) have identified disability risk factors such as working conditions, pain intensity, pain beliefs and expectations for recovery during the critical subacute stage of back pain. During this stage (one to six months postinjury), IVR systems may be useful in assessing pain symptoms and emerging risk factors for chronic pain.

In the present study, patients presenting to occupational health clinics with a recent onset of work-related acute back pain were surveyed and then assessed one month later by telephone for outcomes of pain, function, treatment and work status. Although the comparison of assessment methods was not an original focus of the study, the introduction of an IVR system to facilitate automated data collection partway through the study provided an opportunity to compare data collection methods. Criteria for equivalency of IVR to live telephone interviewing were that IVR responders should have identical demographic and injury characteristics, and identical outcome results, to non-IVR responders.

METHOD

Participants

Participants recruited into the study were 608 working adults (198 women, 410 men) seeking treatment for work-related back pain at eight occupational health clinics in the northeastern United States between September 2000 and October 2002. All participants received evaluation and treatment from an occupational medicine provider in accordance with standard practice guidelines (18), which, in most cases, recommend acute pain relief, conservative care, reassurance and encouragement to resume normal activity as soon as possible.

Inclusion criteria were: nonspecific sacral, lumbar or thoracic back pain; acute onset or exacerbation; pain duration 14 days or less; participants filed a workers’ compensation claim; 18 years of age or older; and fluency in English. Patients with thoracic pain were not excluded from the study because of difficulty in discriminating between thoracic and lumbar pain in a self-report questionnaire before medical evaluation. Prior work with workers’ compensation claimants suggests that noncervical cases of back pain can be categorized as 75% lumbar, 12% thoracic and 13% unspecified (19).

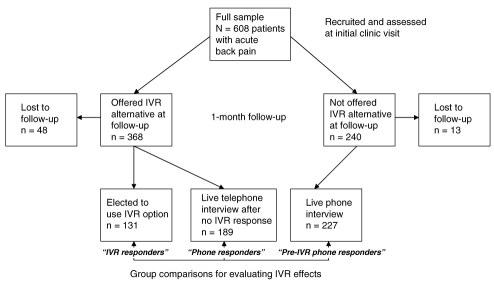

Participants were grouped into three principal categories for analysis: IVR responders, who chose to use an IVR option at one-month follow-up; telephone responders, who completed the follow-up by live telephone interview after failing to use the IVR option within five days; and pre-IVR telephone responders, who completed the one-month follow-up by live telephone interview before the IVR option was made available as an option (Figure 1). Demographic characteristics of the three groups are shown in Table 1. Ages of participants ranged from 18 to 80 years (mean ± SD 36.1±11.0 years), with 90% younger than 50 years of age (two participants older than 67 years of age were working part-time but still covered under workers’ compensation benefits). The majority of the patient sample could be characterized as young to middle-aged workers with a high school education and low to moderate income who were working for medium- to large-sized employers. Median job tenure was two years, and occupations were mostly blue-collar trades and skilled service providers (Table 2). As shown in the table, the most frequent occupational categories and injury types compared favourably with national statistics on work-related back pain (20).

Figure 1).

Response to follow-up before and after implementing an interactive voice response (IVR) data collection system

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of groups by chosen method of follow-up assessment

| IVR responders (n=131) | Phone responders (n=189) | Pre-IVR phone responders (n=227) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 81 (61.8) | 126 (66.7) | 155 (68.3) |

| Female | 50 (38.2) | 63 (33.3) | 72 (31.7) |

| Significance test | χ2=1.58, df=2, P=0.45 | ||

| Education, n (%) | |||

| Less than 9th grade | 3 (2.3) | 4 (2.1) | 5 (2.2) |

| Less than 12th grade | 20 (15.3) | 36 (19.0) | 33 (14.5) |

| High school graduate | 40 (30.5) | 55 (29.1) | 85 (37.4) |

| Some college | 48 (36.6) | 65 (34.4) | 70 (30.8) |

| College degree | 20 (15.3) | 29 (15.3) | 34 (15.0) |

| Significance test | χ2=4.81, df=8, P=0.78 | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 45 (34.4) | 78 (41.3) | 70 (30.8) |

| Married | 59 (45.0) | 78 (41.3) | 119 (52.4) |

| Divorced/widowed | 26 (19.8) | 29 (15.3) | 36 (15.9) |

| No response | 1 (0.8) | 4 (2.1) | 2 (0.9) |

| Significance test | χ2=8.75, df=6, P=0.19 | ||

| Annual income (US$), n (%) | |||

| <5,000 | 2 (1.5) | 4 (2.1) | 5 (2.2) |

| 5,000–10,000 | 12 (9.2) | 6 (3.2) | 9 (4.0) |

| 10,000–15,000 | 14 (10.7) | 8 (4.2) | 18 (7.9) |

| 15,000–25,000 | 23 (17.6) | 53 (28.0) | 64 (28.2) |

| 25,000–40,000 | 42 (32.1) | 49 (25.9) | 78 (34.4) |

| 40,000–60,000 | 24 (18.3) | 44 (23.3) | 41 (18.1) |

| >60,000 | 10 (7.6) | 11 (5.8) | 7 (3.1) |

| No response | 4 (3.1) | 14 (7.4) | 5 (2.2) |

| Significance test | χ2=30.43, df=14, P=0.007 | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Black | 7 (5.3) | 9 (4.8) | 11 (4.8) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 118 (90.1) | 163 (86.2) | 207 (91.2) |

| Hispanic | 4 (3.1) | 13 (6.9) | 8 (3.5) |

| Asian | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| No response | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.6) | 1 (0.4) |

| Significance test | χ2=6.82, df=8, P=0.56 | ||

| Company size, n (%) | |||

| Small (≤50) | 23 (17.6) | 40 (21.2) | 38 (18.7) |

| Medium (51–500) | 51 (38.9) | 75 (39.7) | 100 (41.5) |

| Large (>500) | 57 (43.5) | 74 (39.2) | 89 (39.9) |

| Significance test | χ2=2.35, df=4, P=0.67 | ||

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 36.9±11.7 | 36.3±11.6 | 36.3±10.5 |

| Significance test | F(2,544)=0.17, P=0.84 | ||

| Years with employer (mean ± SD) | 5.0±6.1 | 4.6±5.6 | 4.8±6.8 |

| Significance test | F(2,544)=0.20, P=0.82 | ||

df Degrees of freedom; IVR Interactive voice response

TABLE 2.

Occupations and injury types of patients with work-related acute back pain (n=608)

| Variable | n (%) | Percent from national injury statistics* |

|---|---|---|

| Occupational categories | ||

| Health care | 105 (17.3) | 14.6 |

| Transportation, delivery | 87 (14.3) | 11.0 |

| Retail, restaurant, flight attendant | 61 (10.0) | 9.2 |

| Distribution, warehousing, shipping | 57 (9.4) | 7.9 |

| Sanitation, housekeeping, landscaping | 52 (8.6) | 5.3 |

| Electrical/mechanical, plumbing, auto repair | 50 (8.2) | 8.5 |

| Manufacturing, assembly, seamstress, materials handling | 43 (7.1) | 6.2 |

| Construction trades | 41 (6.7) | 7.7 |

| Public service (eg, police, fire, post office) | 27 (4.4) | 0.8 |

| Machinist, machine operator | 23 (3.8) | 9.7 |

| Airport worker (eg, ticketing, baggage, customer service) | 21 (3.5) | 0.2 |

| Education, childcare | 16 (2.6) | 0.7 |

| Office worker | 14 (2.3) | 6.6 |

| Other | 11 (1.8) | 11.3 |

| Injury types | ||

| Overexertion | 402 (66.1) | 62.2 |

| Bodily reaction† | 91 (15.0) | 16.3 |

| Fall on same level | 41 (6.7) | 7.8 |

| Bodily reaction and exertion, unspecified | 20 (3.3) | 0.8 |

| Fall to lower level | 15 (2.5) | 3.5 |

| Highway accident | 6 (1.0) | 2.3 |

| Struck by object | 6 (1.0) | 2.0 |

| Transportation accident, unspecified | 4 (0.7) | 0.1 |

| Repetitive motion | 4 (0.7) | 1.0 |

| Struck against object | 3 (0.5) | 0.7 |

| Nonhighway motor vehicle accident | 2 (0.3) | 0.5 |

| Assaults and violent acts by person(s) | 2 (0.3) | 0.5 |

| Fall, unspecified | 2 (0.3) | 0.1 |

| Caught in or compressed by equipment or objects | 1 (0.2) | 0.1 |

| Other | 9 (1.5) | 2.1 |

United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2000 (20);

Bodily reactions are cases, usually nonimpact, in which injury or illness resulted from free bodily motion and excessive physical effort (eg, to avoid a falling object)

Procedures

Eligible patients were identified by front desk staff or clinicians during an initial evaluation for a recent onset of back pain. Details of the research study were described, and a consent form was provided to review and sign. The consent form described confidentiality of questionnaires, assured participants that no questionnaire responses would be placed in medical records or shared with employers, and gave notice of a US$25 incentive for participation. After any questions or concerns were addressed, patients were provided a self-report questionnaire to report demographic background, circumstances of injury, current level of pain and potential disability risk factors. Participants returned the completed form to the reception desk before leaving the clinic.

A follow-up period of one month was chosen to distinguish acute cases of pain (resolved within one month) from subacute (lasting greater than one month) because return-to-work rates are dramatically reduced beyond one month of work absence (21). Twenty-eight days after their initial visit (28 to 42 days since pain onset), participants were mailed a postcard that specified a toll-free telephone number and personal identifier for accessing the IVR system. The computerized data collection system allowed participants to call at any time and enter data by push-button responses to recorded questions for tracking improvements in pain, function and ability to work (assessment of disability risk factors was not repeated to maintain an interview duration of less than 20 min). Participants not responding within five days after the mailing were called by a trained interviewer, who conducted the follow-up assessment in a live telephone interview instead. Before activating the IVR system in October 2001, all participants were assessed by live telephone interview only.

Measures

Disability risk:

At the initial clinic visit, participants completed the Back Disability Risk Questionnaire (BDRQ) (22), an 18-item self-report measure designed to assess risk factors for delayed pain recovery and return to work. Questions refer to physical health risks, workplace factors, pain, mood and expectations for recovery, and responses include a variety of Likert rating scales. In combination with demographic variables, the BDRQ has a screening sensitivity of 74.3% and specificity of 70.1% to predict which patients with acute back pain will experience delayed recovery beyond one month (22). Three factor scores from the BDRQ (pain, emotional distress and physical job concerns) have internal consistencies (alpha) of 0.68, 0.70 and 0.60, respectively. Sample items from the BDRQ include: “How worried are you that future physical activity may increase your back pain or result in re-injury?” and “Do you think that you will be able to do your regular job without any restrictions 4 weeks from now?”

Pain:

Participants reported their current level of back pain on a 11-point scale from ‘0’ (no pain at all) to ‘10’ (worst pain possible) at the initial visit and at the one-month follow-up assessment. Two-point changes in this scale have been shown to represent clinically meaningful changes that exceed the bounds of measurement error (23). Pain complaints related to other health concerns or body regions were not assessed.

Functional limitation:

Functional limitation due to back pain was assessed at one-month follow-up using a 16-item abbreviated form of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) (24,25). Respondents report whether each of 16 daily living activities is limited (yes/no) due to pain. A total score is the sum of all positive responses. Sample items include “In the past 2 weeks, because of back pain, have you talked less with those around you?” and “…have you kept rubbing or holding areas of your body that hurt or are uncomfortable?” The RDQ has good reproducibility, construct validity and responsiveness to intervention (26). One-week test-retest reliability for the RDQ is 0.88 (26) and internal consistency is 0.88 (27) (current sample alpha=0.73). The RDQ correlates well with other established measures of physical function (28).

Return to work:

Participants provided details about current work status, any temporary modifications or physician restrictions, and the cumulative duration of work absence and work modification. These data produced three levels of work resumption: not working; working modified or alternate duty; and working full duty. Although the recurrent nature of back pain has led to some controversy about optimal methods for assessing return to work over longer follow-up periods, self-reported work status is a reasonably accurate measure during the first several weeks after pain onset (29).

Treatment helpfulness:

A nine-item measure was adapted from the Treatment Helpfulness Questionnaire developed by Chapman et al (30) for assessing patient perceptions of treatment modalities offered in multidisciplinary pain centres. Participants rated the effectiveness of up to nine possible medical and self-management treatments for their back pain symptoms (eg, physical therapy, prescription medications, ice pack) on a scale from ‘1’ (extremely harmful) to ‘5’ (extremely helpful). A total score was based on the mean for all applicable treatments. Test-retest reliability of the measure is 0.88 (30).

IVR application

In October 2001, an IVR system was introduced to provide pushbutton telephone responses for the outcome measures described above. The application was developed using the Teleflow computer software package (Engenic Corporation, Canada). After calling a toll-free telephone number and entering a unique identifier, callers were provided basic instructions from a prerecorded script and then routed through each of the assessment domains (a total of 32 to 40 questions). Full lists of possible response categories were repeated after each question; however, callers could enter a response at any time and advance to the next question. In some cases, skips were inserted to omit questions that may be invalidated by prior responses; for example, those still out of work were not asked whether they were working at a light duty job. Callers had the option to return to a previous question if a response was entered erroneously. Also, assessments could be partially completed, then resumed in a subsequent call. Completion of the full IVR assessment required 12 min to 22 min (depending on whether respondents listened to all available response options before responding), and data were automatically time- and date-stamped and entered into a single spreadsheet containing follow-up results.

Data analysis

To evaluate the possibility of an IVR self-selection bias, the three groups were compared on demographic variables, symptom characteristics and disability risk factors at intake (one-way ANOVA for continuous variables, χ2 for categorical variables). To test whether IVR assessment was equivalent to that of live telephone interviewing, the three groups were compared on follow-up measures of pain, functional limitation, treatment helpfulness and return to work. Reliability and validity of IVR assessment was determined by comparing the internal consistency and correlations among outcome measures. All variables subjected to analyses of variance had sufficiently normal distributions to conduct parametric tests without data transformations.

RESULTS

Feasibility

Before implementing IVR as an assessment option, 240 patients were recruited into the study and assessed at their initial clinic visit for acute back pain. Of this pre-IVR group, 227 could be reached by a live telephone interviewer for the one-month follow-up assessment (a 94.6% retention rate). After the IVR option was implemented, an additional 368 patients were recruited into the study. Of these, 131 (35.6%) used the IVR option to complete the one-month follow-up assessment, and the remaining 189 (51.4%) were contacted by a live telephone interviewer after no IVR attempt was made within five days. Forty-eight participants could not be reached by telephone (an 87.0% retention rate). The mean duration between intake and follow-up was 29.2±6.6 days for those who took advantage of the IVR option, and 35.4±7.7 days for those who were interviewed by telephone after failing to access the IVR system. Thus, most IVR responders called on the day they received the postcard invitation. Before introducing the IVR system, the mean follow-up time was 30.5±7.8 days.

Seven participants reported technical problems or difficulties understanding IVR instructions and were unable to complete the IVR survey. A follow-up telephone call from research staff was necessary to complete their surveys. The majority of IVR respondents (60%) called into the system during daytime hours (08:00 to 17:00), followed by 34% during evening hours (17:00 to 22:00), 5% during nighttime hours (22:00 to 06:00), and 1% during early morning hours (06:00 to 08:00).

Self-selection IVR bias

Demographic comparisons of the three participant groupings are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant group differences in demographic characteristics of age, sex, education, marital status or job tenure (P>0.05). However, IVR use was greater among lower income participants, χ2=30.43 (degrees of freedom=14), P=0.007. Sixty-one per cent of those reporting an annual income of less than $15,000 used the IVR option, versus 39.9% IVR use among others.

Health-related questions from the BDRQ are shown in Table 3. These questions were completed at the initial medical evaluation for back pain. There were no statistically significant differences between IVR and telephone respondents by injury type, previous back pain, pain avoidance beliefs, expectations for return to work, exercise habits, health rating, body mass index or mood (P>0.05). There was, however, a group difference in pain ratings whereby those reporting more pain at intake were more likely to take advantage of the IVR option one month later, FM(2,544)=3.11, P=0.04. Due to a small negative correlation between income and pain rating (r=−0.13, P=0.002), the relationship between pain and IVR use was no longer statistically significant after controlling for income.

TABLE 3.

Health comparisons of groups at intake by chosen method of follow-up assessment

| Variable | IVR responders (n=131), n (%) | Phone responders (n=189), n (%) | Pre-IVR phone responders (n=227), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injury type | |||

| Overexertion | 88 (67.2) | 132 (69.8) | 144 (63.4) |

| Bodily reaction* | 23 (17.6) | 31 (16.4) | 43 (18.9) |

| Fall | 14 (10.7) | 13 (6.9) | 28 (12.3) |

| Other | 6 (4.6) | 13 (6.9) | 12 (5.3) |

| Significance test | χ2=4.97, df=6, P=0.55 | ||

| History of medical treatment for back pain | |||

| Yes | 51 (38.9) | 74 (39.2) | 105 (46.3) |

| No | 80 (61.1) | 115 (60.8) | 122 (53.7) |

| Significance test | χ2=2.82, df=2, P=0.24 | ||

| Concern that activity may increase pain | |||

| Extremely concerned | 18 (13.7) | 22 (11.6) | 35 (15.4) |

| Very concerned | 35 (26.7) | 45 (23.8) | 56 (24.7) |

| Somewhat concerned | 45 (34.4) | 68 (36.0) | 81 (35.7) |

| A little concerned | 26 (19.8) | 39 (20.6) | 43 (18.9) |

| Not concerned at all | 7 (5.3) | 15 (7.9) | 12 (5.3) |

| Significance test | χ2=2.93, df=8, P=0.94 | ||

| Expected return to regular job within four weeks | |||

| Definitely | 34 (26.0) | 45 (23.8) | 53 (23.3) |

| Probably | 61 (46.6) | 86 (45.5) | 93 (41.0) |

| Not sure | 33 25.2) | 51 (27.0) | 74 (32.6) |

| Unlikely | 1 (0.8) | 4 (2.1) | 3 (1.3) |

| No | 2 (1.5) | 3 (1.6) | 4 (1.8) |

| Significance test | χ2=4.01, df=8, P=0.86 | ||

| Frequency of moderate exercise | |||

| Never | 4 (3.1) | 12 (6.3) | 12 (5.3) |

| Rarely | 27 (20.6) | 40 (21.2) | 53 (23.3) |

| Once per week | 23 (17.6) | 31 (16.4) | 45 (19.8) |

| 2–3 times per week | 44 (33.6) | 81 (42.9) | 70 (30.8) |

| ≥4 times per week | 33 (25.2) | 25 (13.2) | 47 (20.7) |

| Significance test | χ2=13.34, df=8, P=0.10 | ||

| General health rating | |||

| Excellent | 25 (19.1) | 31 (16.4) | 27 (11.9) |

| Very good | 48 (36.6) | 74 (39.2) | 96 (42.3) |

| Good | 52 (39.7) | 81 (42.9) | 94 (41.4) |

| Fair | 6 (4.6) | 3 (1.6) | 9 (4) |

| Poor | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Significance test | χ2=8.06, df=8, P=0.43 | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)† | 27.4±5.04 | 28.05±5.47 | 27.99±5.35 |

| Significance test | F(2,544)=0.58, P=0.56 | ||

| Pain rating (0–10)† | 6.26±1.97 | 5.81±2.05 | 6.27±1.99 |

| Significance test | F(2,544)=3.11, P=0.04 | ||

| Feeling downhearted (1–5)† | 1.14±1.2 | 1.05±1.21 | 1.26±1.18 |

| Significance test | F(2,544)=1.64, P=0.20 | ||

| Feeling stressed (1–5)† | 1.92±1.29 | 1.99±1.3 | 2.07±1.34 |

| Significance test | F(2,544)=0.54, P=0.59 | ||

Bodily reactions are cases, usually nonimpact, in which injury or illness resulted from free bodily motion and excessive physical effort (eg, to avoid a falling object);

Mean ± SD. df Degrees of freedom; IVR Interactive voice response

Equivalency of IVR

Outcomes of return to work, pain, functional limitation and treatment helpfulness are summarized according to assessment method in Table 4. At the one-month follow-up, a majority of participants (47.9%) had resumed their regular job assignment, although 28% of these individuals believed they were accomplishing less at work because of back pain (an item in the RDQ). One hundred ninety participants (35%) were working modified or restricted duties because of back pain, and 95 (37%) were still out of work. There were no statistically significant differences in one-month work status between IVR and live telephone interview respondents (P>0.05).

TABLE 4.

One-month outcomes by chosen method of follow-up assessment

| Variable | IVR responders (n=131) | Phone responders (n=189) | Pre-IVR phone responders (n=227) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work status, n (%) | |||

| Not working | 26 (19.8) | 28 (14.8) | 41 (18.1) |

| Working limited duty | 53 (40.5) | 59 (31.2) | 78 (34.3) |

| Working full duty | 52 (39.7) | 102 (54) | 108 (47.6) |

| Significance test | χ2=6.45, df=4, P=0.17 | ||

| Days until one-month follow-up data obtained (mean) | 29.21±6.64 | 35.43±7.73 | 30.52±7.81 |

| Significance test | F(2,544)=33.01, P<0.0001 | ||

| Pain rating (mean) | 3.13±2.2 | 2.78±2.14 | 3.18±2.33 |

| Significance test | F(2,544)=1.84, P=0.16 | ||

| Adjusted pain rating* (mean) | 3.05±2.25 | 2.89±2.31 | 3.13±2.24 |

| Significance test | F(2,542)=0.56, P=0.57 | ||

| Functional limitation (mean) | 48.61±31.11 | 38.22±30.79 | 40.12±29.86 |

| Significance test | F(2,544)=4.89, P=0.008 | ||

| Adjusted functional limitation* (mean) | 46.30±30.26 | 41.47±31.00 | 38.94±30.01 |

| Significance test | F(2,542)=2.52, P=0.08 | ||

| Treatment helpfulness (mean) | 3.87±0.58 | 4.05±0.45 | 3.95±0.50 |

| Significance test | F(2,543)=4.69, P=0.01 | ||

| Adjusted treatment helpfulness* (mean) | 3.89±0.52 | 4.03±0.52 | 3.96±0.51 |

| Significance test | F(2,541)=2.95, P=0.06 | ||

Adjusted marginal means are adjusted for differences in days until follow-up data are obtained. df Degrees of freedom; IVR Interactive voice response

In terms of health outcomes, IVR respondents reported more functional limitation and less helpful treatments, but no differences in pain ratings. Because significant group differences in the number of days before follow-up data were obtained, the analyses were repeated in an analysis of covariance controlling for the actual number of days between intake and follow-up. The adjusted means are shown in Table 4. After controlling for differences in timing of assessments, the group differences in functional limitation and treatment helpfulness were no longer statistically significant (P=0.08 and P=0.06, respectively).

Reliability and validity

To provide an estimate of the reliability of IVR versus live telephone interviewing, the internal consistency (alpha) of the 16-item RDQ were compared between groups. Among IVR respondents (n=131), the internal consistency (alpha) of the scale was 0.72 (standardized item alpha=0.81). Among all live telephone respondents (n=416), the internal consistency (alpha) of the scale was 0.73 (standardized item alpha=0.80).

To provide an estimate of the validity of IVR versus live telephone interviewing, the within-group correlations between pain and functional limitation were compared. A test of group interactions showed no statistically significant differences in the association between pain and function in the two groups (F[1,543]=0.72, P=0.40). Among IVR respondents (n=131), the Pearson correlation was 0.61. Among all live telephone respondents (n=416), the Pearson correlation was 0.57.

DISCUSSION

Implementing IVR as an automated option for recording pain and disability appears to have had little, if any, effect on the responses of participants in the present prospective cohort study of acute back pain. Although the IVR system reduced staffing requirements for the study, more than one-half of participants failed to use the IVR option, and it was necessary for interviewers to contact these individuals by telephone later. IVR assessment appears equally feasible and valid at different levels of age, education and income; in fact, lower income patients were more likely to take advantage of the IVR option. While more work is needed to demonstrate the potential feasibility of IVR for clinical applications, the present study found no evidence of a systematic bias that might invalidate IVR as an inexpensive tool for data collection.

The low IVR utilization rate in this study (35%) may be due to a number of factors. First, although participants were informed of the follow-up telephone assessments at the time of study recruitment, they were not informed of the IVR option nor provided instructions for IVR use; this option was described in a postcard sent one month later. Some participants may have failed to recognize the postcard or disposed of it inadvertently. Others who intended to use the IVR system may have simply procrastinated beyond the five-day time frame before a live attempt was made. A longer call-in period may have generated a higher use rate. Third, participants were provided no special incentive for using the IVR option (besides added convenience). Other incentives (eg, the ability to access useful medical advice) may increase utilization rates. Because ratings of treatment helpfulness were generally high, it is unlikely that frustration with medical care had any bearing on IVR utilization rates. Although the IVR utilization rate was low, there were considerable cost savings (approximately US$100 per IVR call) in the reduced hours required by paid interviewers.

Only one other study (31), a random digit dialing study of attitudes about mass media, evaluated self-selection bias among IVR responders. The researchers found that IVR users were younger (which they attributed to technology savvy) and less educated (which the researchers attributed to greater frankness in reporting education via IVR). We found no association of IVR use with age, but there was a greater preference for IVR use among lower income patients. The latter finding cannot be explained by more frank IVR reporting of income in the present study because this variable was assessed as part of an earlier pen-and-paper measure. An alternative explanation is that lower income participants may have opted for IVR to overcome telephone access problems associated with shared living arrangements or unusual working hours. Therefore, IVR surveys may have potential benefits for improving response rates among low income respondents, a common problem in mail-in and Web-based surveys (32,33).

Participants who reported higher levels of back pain at their initial medical evaluation were more likely to use the IVR option one month later, but this association was confounded by income. After controlling for income, IVR responders were no different on pain levels at intake, and there were no significant differences in pain report at the one-month follow-up. Therefore, we can conclude that patients experiencing delayed pain and functional recovery were no less likely than others to use the IVR option, and this may have important implications given the tendency of patients reporting more symptoms to withdraw from pain research studies and intervention protocols (34).

Implementation of IVR in the present study had a mixed effect on the timeliness of follow-up assessments. Among those who used the IVR option, the follow-up time was improved by an average of one day (29.2 versus 30.5 days); however, the five-day waiting period before calling nonrespondents resulted in a substantial delay for reaching others (35.4 versus 30.5 days). The net effect was a delay of 2.4 days (32.9 versus 30.5 days). A possible method for improving IVR response rates is to program the system to call participants repeatedly until data collection is complete, but this is far more intrusive and less convenient for participants.

A primary concern was informational bias, wherein IVR may produce different assessment results without the demand characteristics of responding to a live telephone interviewer. Those who used IVR reported more functional limitation on the RDQ and less helpful treatments, but these differences were explained by the time delay in reaching the comparison group of telephone respondents (the comparison group had, on average, five additional days to recover). Therefore, we conclude that there were no differences between IVR and live telephone interviewing. This contrasts with the findings of Millard and Carver (35) that IVR users with back pain reported greater emotional concerns, and poorer mood and overall health. Other studies have found no differences between IVR and written questionnaires for assessing musculoskeletal function (36) and daily allergy symptoms (37). In addition to finding no significant differences in health report in the present study, there were also no differences in scale reliability or in correlations between outcome measures.

For IVR systems to have clinical utility for monitoring of patient pain and function, several obstacles must be overcome. First, low response rates must be improved by providing incentives or by incorporating medical information, instructions, or feedback that would be useful to patients. For example, patients with acute back pain could be provided information about self-care for pain management, goals for resuming various physical activities, and realistic expectations for treatment and recovery. Such IVR counselling methods have been successful in providing tailored advice to patients on cancer screening (38), smoking cessation (39), elderly caregiving (40) and cardiac rehabilitation (41). Second, the utility of IVR should be improved by integrating IVR data with clinical decision-making for recommending treatments, making referrals and assessing the need for follow-up visits. For example, patients showing slower than normal recovery may be automatically referred for physical therapy. For patients with growing concerns about resuming work, providers could intensify their communications with employers. IVR data collection has been noticeably absent from the ongoing debate over the use of electronic health records to improve coordination of care (42).

Although IVR evaluation was not the primary objective of our data collection efforts in the present study, these data have provided a reasonable opportunity for evaluating the equivalency of IVR data collection to live telephone interviewing. Other study designs may provide additional opportunities for more detailed psychometric evaluation (eg, test-retest reliability or randomized designs). A randomized study in which participants are randomly assigned to either IVR or live telephone assessment and provide preferences or perceptions of IVR use would be optimal. Limitations of the present study include its nonrandomized design, a relatively low IVR response rate and the potential confound of secular trends, because IVR was introduced partway through the study. Also, results of the study may not generalize to other pain conditions that are of a more longlasting or disabling nature.

The present study is the first to evaluate the equivalency of IVR to live telephone interviewing for assessing painrelated outcomes. Conclusions of this study are that IVR assessment of pain-related outcomes seems a reasonable alternative to live telephone interviewing, that IVR may be preferred by lower income groups, and that approximately one-third of respondents take advantage of the IVR option without any special incentive. Although a number of obstacles must be overcome to integrate IVR data collection into routine clinical practice, this option has potential for monitoring patient recovery and coordinating care after the onset of back pain. Future studies could investigate ways to improve IVR utilization rates among patient populations, track changes in symptoms over time and integrate IVR systems with clinical care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mary Jane Woiszwillo for her assistance with data collection and management, and also the clinicians and staff of the participating clinics of Concentra Health Services (Warwick, Rhode Island; Portland, Maine; Pawtucket, Rhode Island; Lewiston, Maine) and Caregroup Occupational Health Network (Waltham, Massachusetts; Chelsea, Massachusetts; Boston, Massachusetts) for their recruitment of study participants and completion of provider questionnaires.

Footnotes

All work completed at the Liberty Mutual Research Institute for Safety with funding from the Liberty Mutual Group (Project #CDR 99-04).

References

- 1.Cook AJ, Roberts DA, Henderson MD, Van Winkle LC, Chastain DC, Hamill-Ruth RJ. Electronic pain questionnaires: A randomized, crossover comparison with paper questionnaires for chronic pain assessment. Pain. 2004;110:310–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein HS, Rabaza JR, Gonzalez AM, Verdeja JC. Evaluation of pain and disability in plug repair with the aid of a personal digital assistant. Hernia. 2003;7:25–8. doi: 10.1007/s10029-002-0090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gosling SD, Vazire S, Srivastava S, John OP. Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about internet questionnaires. Am Psychol. 2004;59:93–104. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain and frequent use of health care. Pain. 2004;111:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corkrey R, Parkinson L. Generalized Electronic Interviewing System (GEIS): A program and scripting method for conducting interviews in multiple modes. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36:784–96. doi: 10.3758/bf03206559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holm I, Friis A, Storheim K, Brox JI. Measuring self-reported functional status and pain in patients with chronic low back pain by postal questionnaires: A reliability study. Spine. 2003;28:828–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey TS, Garrett J, Jackman A, Sanders L, Kalsbeek W. Reporting of acute low back pain in a telephone interview: Identification of potential biases. Spine. 1995;20:787–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corkrey R, Parkinson L. Interactive voice response: Review of studies 1989–2000. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2002;34:342–53. doi: 10.3758/bf03195462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kranzler HR, Abu-Hasabllah K, Tennen H, Feinn R, Young K. Using daily interactive voice response technology to measure drinking and related behaviors in a pharmacotherapy study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1060–4. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000130806.12066.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mundt JC, Clarke GN, Burroughs D, Brenneman DO, Griest JH. Effectiveness of antidepressant pharmacotherapy: The impact of medical compliance and patient education. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13:1–10. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2001)13:1<1::aid-da1>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobak KA, Griest JH, Jefferson JW, Katzelnick DJ. Computeradministered clinical rating scales. A review. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;127:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s002130050089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naylor MR, Helzer JE, Naud S, Keefe FJ. Automated telephone as an adjunct for the treatment of chronic pain: A pilot study. J Pain. 2002;3:429–38. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.129563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burdorf A, Naaktgeboren B. Prognostic factors for musculoskeletal sickness absence and return to work among welders and metal workers. Occup Environ Med. 1998;55:490–5. doi: 10.1136/oem.55.7.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coste J, Delecoeuillerie TG, Cohen de Lara A, Le Parc JM, Paolaggi JB. Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute low back pain: An inception cohort study in primary care practice. BMJ. 1994;308:577–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6928.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pransky G, Shaw WS, Fitzgerald TE. Prognosis in acute occupational low back pain: Methodologic and practical considerations. Hum Ecol Risk Assess. 2001;7:1811–25. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman JB. The prevention of occupational low back pain disability: Evidence-based reviews point in a new direction. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2004;13:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw WS, Pransky G, Fitzgerald TE. Early prognosis for low back disability: Intervention strategies for health care providers. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:815–28. doi: 10.1080/09638280110066280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agency for Health Care Policy and Research . Clinical practice guidelines, acute low back problems in adults Silver Spring. Maryland: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer WO, LeBlanc FE, Dupuis M, et al. Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-related spinal disorders: A monograph for clinicians. Report of the Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders. Spine. 1987;12(Suppl 1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bureau of Labor Statistics Case and demographic characteristics for work-related injuries and illnesses involving days away from work, 2000 (Tables R10, R50-54), Accessed March 4, 2003.

- 21.Hashemi L, Webster BS, Clancy EA, et al. Length of disability and cost of workers’ compensation low back claims. J Occup Environ Med. 1997;39:937–45. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199710000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw WS, Pransky GS, Patterson WB, Winters T. Early disability risk factors for low back pain assessed at outpatient occupational health clinics. Spine. 2005;30:572–80. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000154628.37515.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Childs JD, Piva SR, Fritz JM. Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back pain. Spine. 2005;30:1331–4. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000164099.92112.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, Singer DE, Chapin A, Keller RB. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine. 1995;20:1899–1909. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of low back pain: Part 1. Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine. 1983;8:141–4. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198303000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine. 2000;25:3115–24. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacob T, Baras M, Zeeb A, Epstein L. Low back pain: Reliability of a set of pain measurement tools. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:735–42. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.22623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johansson E, Lindberg P. Subacute and chronic low back pain: Reliability and validity of a Swedish version of the Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1998;30:139–43. doi: 10.1080/003655098444066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wasiak R, Pransky G, Verma S, Webster B. Recurrence of low back pain: definition sensitivity analysis using administrative data. Spine. 2003;28:2283–91. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000085032.00663.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapman SL, Jamison RN, Sanders SH. Treatment Helpfulness Questionnaire: A measure of patient satisfaction with treatment modalities provided in chronic pain management programs. Pain. 1996;68:349–61. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Havice MJ, Banks MJ. Live and automated telephone surveys: A comparison of human interviewers and an automated technique. J Market Res Soc. 1991;33:91–102. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ekman A, Dickman PW, Klint A, Weiderpass E, Litton JE. Feasibility of using web-based questionnaires in large population-based epidemiological studies. Eur J Epidiol. 2006;21:103–11. doi: 10.1007/s10654-005-6030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gibson PJ, Koepsell TD, Diehr P, Hale C. Increasing response rates for mailed surveys of Medicaid clients and other low-income populations. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:1057–62. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaw WS, Cronan TA, Christie MD. Predictors of attrition in health intervention research among older subjects with osteoarthritis. Health Psychol. 1994;13:421–31. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.5.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Millard RW, Carver JR. Cross-sectional comparison of live and interactive voice recognition administration of the SF-12 health status survey. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5:153–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agel J, Rockwood T, Mundt JC, Greist JH, Swiontkowski M. Comparison of interactive voice response and written self-administered patient surveys for clinical research. Orthopedics. 2004;24:1155–7. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20011201-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiler K, Christ AM, Woodworth GG, Weiler RL, Weiler JM. Quality of patient-reported outcome data captured using paper and interactive voice response diaries in an allergic rhinitis study: Is electronic data capture really better? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;92:335–59. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corkrey R, Parkinson L, Bates L, Green S, Htun AT. Pilot of a novel cervical screening intervention: Interactive voice response. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2005;29:261–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2005.tb00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDaniel AM, Benson PL, Roesener GH, Martindale J. An integrated computer-based system to support nicotine dependence treatment in primary care. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(Suppl 1):S57–S66. doi: 10.1080/14622200500078139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahoney DF, Tarlow BJ, Jones RN. Effects of an automated telephone support system on caregiving burden and anxiety: findings from the REACH for TLC intervention study. Gerontologist. 2003;43:556–67. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bambauer KZ, Aupont O, Stone PH, et al. The effect of a telephone counselling intervention on self-rated health of cardiac patients. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:539–45. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000171810.37958.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burton LC, Anderson GF, Kues IW. Using electronic health records to help coordinate care. Milbank Q. 2004;82:457–81. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]