Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) is a global issue, not only affecting individual suffering, but also impacting the delivery of health care and the strength of local economies.

OBJECTIVES:

The current study (the Canadian Chronic Pain Study II [CCPSII]) was designed to assess any changes in the prevalence and treatment of CNCP, as well as in attitudes toward the use of strong analgesics, compared with a 2001 study (the CCPSI), and to provide a snapshot of the current standards of care for pain management in Canada.

METHODS:

Standard, computer-assisted telephone interview survey methodology was applied in two segments, ie, a general population survey and a survey targeting randomly selected primary care physicians (PCPs) who treat moderate to severe CNCP.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION:

The patient-reported prevalence of CNCP within Canada has not markedly changed since 2001 but the duration of suffering has decreased. There have been minor changes in regional distribution and generally more patients receive medical treatment, which includes prescription analgesics. Physicians continue to demonstrate opiophobia in their prescribing practices; however, although this is lessened relating to addiction, abuse remains an important concern to PCPs. Canadian PCPs, in general, are implementing standard assessments, treatment approaches, evaluation of treatment success and tools to prevent abuse and diversion, in accordance with guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society and other pain societies globally, although there remains room for improvement and standardization.

Keywords: Assessment, Impact, Prescribing attitudes, Prevalence of chronic pain, Risk of abuse

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

La douleur chronique non cancéreuse (DCNC) est un problème global qui n’affecte pas seulement la personne souffrante, mais également la prestation des soins de santé et la vigueur des économies locales.

OBJECTIFS :

La présente étude (CCPS II [Canadian Chronic Pain Study II]) a été conçue pour mesurer, le cas échéant, les changements qui ont influé sur la prévalence et le traitement de la DCNC, de même que sur les attitudes vis-à-vis du recours aux analgésiques puissants, comparativement à une étude réalisée en 2001 (l’étude CCPS I) et dresser un portrait des normes actuelles en matière de contrôle de la douleur au Canada.

MÉTHODE :

Méthodologie d’enquête standard par entrevue téléphonique assistée par ordinateur, appliquée à deux segments de population, soit enquête auprès de la population générale et enquête auprès d’omnipraticiens qui soignent la DCNC de modérée à sévère sélectionnés au hasard.

RÉSULTATS ET DISCUSSION :

La prévalence de la DCNC telle qu’elle est signalée par les patients au Canada n’a pas sensiblement changé depuis 2001, mais la durée de la douleur a diminué. On a noté des changements mineurs quant à la distribution régionale et en général, un plus grand nombre de patients reçoivent un traitement médical qui inclut des analgésiques vendus sur ordonnance. Les habitudes de prescription des médecins continuent de témoigner de leur « opiophobie ». Par contre, bien que celle-ci semble moins associée à la peur de la dépendance, les risques d’abus continuent de préoccuper les omnipraticiens. Les omnipraticiens canadiens appliquent généralement les techniques d’examen, les approches thérapeutiques, les évaluations de traitement et les outils standard pour prévenir les abus et autres usages illicites, conformément aux directives de la Société canadienne pour le traitement de la douleur et d’autres sociétés apparentées à l’échelle globale. Mais il y a toujours place pour l’amélioration et la standardisation.

The current study (the Canadian Chronic Pain Study II [CCPSII]) was planned to assess changes in chronic pain (CP) prevalence and treatment, as well as attitudes toward use of strong analgesics and opiophobia, compared with a similar study conducted in 2001 (CCPSI) (1), and to assess the current standards of care for pain management in Canada.

CP of noncancer origin has been variably defined, making it difficult to compare published data. Definitions include pain lasting for two weeks or longer (2); continuous moderate to severe pain, excluding cancer pain (3); pain persisting for three months or longer (4–6); pain not associated with malignancy or other terminal diagnosis, persisting for longer than six months (7); and pain persisting beyond the time normally associated with healing for a specific illness or injury (8,9). The term ‘persistent pain’ has been used interchangeably with CP (10,11). In the current study, CP is defined as ‘pain continuously or intermittently for a period of six months or longer’, to be consistent with the earlier comparator CCPSI (1) and with the guidelines of the Canadian Pain Society (9).

PREVALENCE

General population surveys have reported the prevalence of CP in Canada to be between 15% (2) and 29% (1). Methodological differences contributing to variation may include retrospective versus prospective data collection, random general surveys versus targeted selection, varying patient recall time periods, different definitions of CP and differing age groups surveyed.

In other countries, prevalence is variably reported. In a general practice group retrospective analysis in Sweden (12), 30% of patients had some form of defined pain; of these, 37% suffered CP (longer than three months). In an Australian general population survey (5), 19% suffered from CP (longer than three months). A recent large European survey (13) observed CP of moderate to severe pain intensity (PI) in 19% of adults from 15 countries (range 12% to 30%).

GUIDELINES

Undertreatment of pain is seen as a serious societal problem globally, and multiple clinical practice guidelines exist for the management of chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) (9–11,14). Recommended medications for moderate to severe CNCP are similar across guidelines; they include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), and weak and strong opioids, and generally follow the World Health Organization ladder (15). Additional adjuvant therapies frequently used include antidepressants and anticonvulsants (16). These clinical practice guidelines emphasize that opioids can be an essential part of effective pain management, and discuss ways to minimize abuse, misuse and diversion, and how to limit side effects. All note that the treatment goal is to achieve improvement in physical, psychological and social functioning.

CCPSI 2001

In 2001, a prevalence study sampled 2012 Canadian adults (1). Overall, 29% of respondents reported CP, and prevalence increased with age. A separate study of 340 CP patients reported an average pain duration of 10.7 years and an average PI of 6.3 (on a scale of 0 to 10), with 80% reporting moderate to severe pain. The study assessed analgesic treatments used, socioeconomic impact and patient attitudes to opioids. The study concluded that CP was undertreated in Canada and that major opioid analgesics were underused in the management of moderate to severe pain.

A complementary study of 100 Canadian primary care practitioners (PCPs) and palliative care physicians with a defined interest in pain (70 PCPs and 30 palliative care physicians) assessed attitudes toward CP management, medication use and barriers to the use of opioids in moderate to severe CP (17). Most chose NSAIDs or acetaminophen as first-line treatment; 32% considered opioids to be the first line of treatment. Key barriers to prescribing opioids included addiction potential, abuse or misuse potential, side effects and fear of review by professional bodies. Overall, 68% of participants said that moderate to severe CP was not well managed in Canada, and that the consequences included needless suffering, emotional impact (patient and family), increased burden to the health care system, economic losses and drug addiction.

BARRIERS TO OPIOID USE

Opiophobia (first coined by Morgan in 1985 [18]) is an irrational fear of using or prescribing opioids, based on clinical, regulatory and medicolegal potential risk factors that impede appropriate prescribing in the treatment of pain. Opiophobia is an internationally identified factor believed to impede the treatment of pain (19).

Physicians globally are concerned by opioid’s cognitive and psychomotor side effects, physical dependency, tolerance, legal and regulatory repercussions, the administrative burden associated with prescribing scheduled analgesics, risks of addiction, abuse, misuse, diversion and attracting addicts to one’s practice (20,21). Similarly, patients may fear a stigma of ‘terminal disease’ associated with opioids, and social and law enforcement bodies may view legitimate prescribing as putting society at risk of abuse and/or diversion.

Opioids, as a class, have well-defined side effects, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, dizziness and sedation, many of which can be managed with dose adjustments, adjunctive medications and nonpharmacological approaches (22). The safety of the long-term use of opioids in select CNCP patients has been studied (23), and, unlike NSAID prostaglandinrelated side effects, opioids have no organ toxicity (24). Recent reports of hypogonadism associated with long-term treatment with oral opioids in male cancer survivors (25) and with long-term methadone treatment of heroin addicts (26), but not with buprenorphine (27), may be significant and warrant further study.

The current study provides a snapshot-in-time of the state of pain management in Canada.

METHODS

Survey methodology

To assess changes since 2001 in CNCP prevalence, treatment and attitudes to the use of strong analgesics, as well as to capture current (2004) standards of CNCP care in Canada, a survey was conducted by Ipsos Reid Canada. Approximately 4000 Canadian physicians were identified as prescribers of strong analgesics from the Ipsos Reid national MedSamp Database (based on the 2004 Canadian Medical Directory). From this pool, physicians were randomly selected to reflect physician regional distribution as per the 2001 Canadian census statistics. In the 2001 survey of the management of both cancer- and noncancerrelated pain, 30% of responders were palliative care physicians who mostly treated only cancer pain. Because the current survey focused exclusively on CNCP, only PCPs (general practitioners and family practitioners) were included, because they are generally first line in the management of CNCP. A total of 2545 physicians were contacted by telephone. Of these, 100 were recruited to participate in the survey.

To meet the eligibility criteria, physicians were required to have written 20 or more prescriptions for CNCP in the previous four-week period, and at least 51% of their patients being treated for long-term CP had to suffer from CNCP. CP was defined as pain continuously or intermittently for a period of six months or longer. Approximately 77% of the 2545 contacted either declined to participate in or were unavailable for the time of the interview, and 18% contacted did not meet the eligibility criteria. The interview lasted approximately 30 min. Physicians were paid an honorarium for their participation; the study sponsor was not identified during the research interviews. All interviews were conducted in June and July 2004.

A complementary general population survey was conducted in February 2004 to benchmark the current prevalence of CP, as well as its impact on quality of life and on the frequency of visits to the PCP. This survey was included as one component of an omnibus (multiclient) express survey (Canadian Ipsos Reid Express). Consumer adults (18 years of age or older), balanced by region of domicile, sex and age as per 2001 Canadian Census statistics, were randomly selected for a general population survey using the random digital dialing method; in the 2001 survey, sufferers were drawn from panels representing specific disease states. All interviews were conducted by experienced staff, using computer-assisted telephone interviews and following standard, computer-assisted telephone interview methodology. Random digital dialing calls were placed Tuesday through Thursday evenings (local time) to prevent a bias against those in daytime employment. This component of the omnibus interview lasted approximately 10 min. A total of 1055 individuals participated, representing a 20% response rate (19.1% in 2001); the response rate for omnibus consumer research is generally between 18% and 22% (Ipsos Reid, personal communication).

Survey questions

The patient survey included a total of 13 brief questions relating to the origin, duration and intensity of the CP condition(s), treatment and quality of life. The key elements of the survey are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Methodology: Summary of survey key elements

| Patient survey | Physician survey |

|---|---|

|

|

CP Chronic pain; PCP Primary care practitioner

The physician survey asked a total of 38 questions relating to the population of CNCP patients, focusing on those with moderate to severe pain severity. The key elements of the survey are summarized in Table 1.

Most of the questions asked were identical to those in the 2001 survey, allowing for comparisons. Some gaps were identified and new questions were added, primarily relating to aspects of pain assessment, treatment algorithms, evaluation of therapy, impact of CP and attitudes surrounding the use of strong analgesics.

Statistical considerations

When conducting a general population survey, the target sample size is 1000 respondents to give a margin of error within ±3%; for a patient or sufferer study, a target of 400 respondents gives a margin of error within 5%. Both are at the 95% level of confidence and assume that the sample proportion is at least 50% homogenous.

Descriptive statistics such as frequency distribution, means and variance were used for the sample analysis. When multiple groups were involved, comparisons of means were conducted using ANOVA. For categorical variables, such as attitude statements, Pearson χ2 tests were used. All statistical significance levels were set at P<0.05 for the overall sample analysis, and individual P values were calculated when deemed necessary. SPSS (version 10.2, SPSS Inc, USA) was used to perform the analyses.

RESULTS

Because of the volume of data, to illustrate change over time, comparisons to the CCPSI are made directly in the presentation of results.

Patient survey

Sample:

A total of 1055 respondents were included in the survey (the CCPSII), compared with the sample of 2012 respondents in 2001 (the CCPSI general population prevalence survey was conducted in two separate waves with data consistent between waves; both had more than 1000 respondents). The current sample was regionally distributed: British Columbia, n=132; Alberta, n=100; Saskatchewan and Manitoba, n=100; Ontario, n=385; Quebec, n=238; and the Atlantic provinces, n=100.

There were in total 483 men and 572 women, and age distribution was: 18 to 34 years, n=319; 35 to 54 years, n=444; and 55 years and older, n=259. The sample was stratified regionally, and balanced by sex, age and region, as per 2001 census statistics.

Prevalence of CP:

CP (continuous or intermittent and lasting for six months or longer) was experienced by 25% of the sample, not significantly different from 29% in 2001 (Table 2). The prevalence varied somewhat regionally (minimum in Quebec 16% in 2004 versus 18% in 2001; maximum in the Atlantic provinces 36% versus 34% in 2001), with decreases seen in Alberta (26% versus 34% in 2001), Manitoba and Saskatchewan (29% versus 34% in 2001) and Ontario (25% versus 33% in 2001). The prevalence increased with age: 18 to 34 years, 17%; 35 to 54 years, 25%; and 55 years and older, 33%. It was higher in women (27% versus 22%) but was not markedly different from 2001. On average, 12% of all individuals surveyed were taking prescription analgesic medications, versus 11% in 2001; this varied regionally from 9% in British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, and Quebec to 23% in the Atlantic provinces (increased from 15% in 2001). As with prevalence, medication use increased with age, from 5% in the youngest group, to 18% in the 55 years and older group, which is unchanged from 2001.

TABLE 2.

Incidence of chronic pain* by location, age and sex

| Incidence, %

|

||

|---|---|---|

| 2004 (n=1055) | 2001 (n=2012) | |

| Total sample | 25 | 29 |

| Location | ||

| British Columbia | 30 | 31 |

| Alberta | 26 | 34 |

| Manitoba and Saskatchewan | 29 | 34 |

| Ontario | 25 | 33 |

| Quebec | 16 | 18 |

| Atlantic provinces | 36 | 34 |

| Age, years | ||

| 18 to 34 | 17 | 22 |

| 35 to 54 | 25 | 29 |

| 55+ | 33 | 39 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 22 | 27 |

| Female | 27 | 31 |

Continuous or intermittant pain lasting for six months or longer

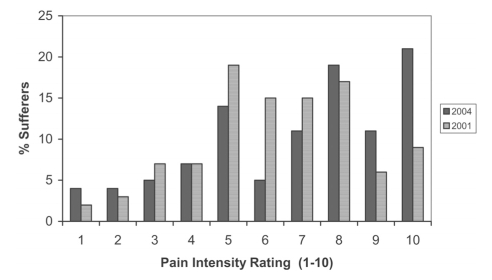

Of CP sufferers, 49% were taking a prescription analgesic medication, compared with 38% in 2001 (P=0.005), again in ratios reflecting the prevalence by age (38% of those aged 18 to 34 years, 44% of those aged 35 to 54 years, 59% of those aged 55 years and older) and sex (45% of men, 52% of women). Of those with moderate pain (PI 4 to 7), 35% were taking prescription analgesics; with severe pain (PI 8 to 10), this increased to 72%. Twenty-eight per cent of those with severe PI were not taking any prescription analgesic medication. Of those suffering any degree of CP, the mean duration of CP was 9.8 years, versus 10.7 years in 2001 (P<0.01) (median duration in 2004 was 6.0 years) and the mean degree of PI was 6.9, versus 6.3 in 2001 (P=0.008). Patients suffering moderate to severe pain (PI 4 to 10) comprised 88% of the CP patients surveyed in both 2001 and 2004, although the distribution changed, with 37% citing moderate PI in 2004, versus 56% in 2001 (P<0.001) and 51% citing severe PI in 2004, versus 32% in 2001 (P<0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Degree of pain intensity. Percent of sufferers rating their chronic pain intensity on a numerical scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is the least and 10 is the worst: 2004 versus 2001

Socioeconomic impact of CP:

Regardless of medication status, CP was determined to interfere with day-to-day life to some extent in 40% of respondents and to a large extent in 28% (data not collected in 2001). Of those taking prescription analgesics, 39% said that CP interfered with day-to-day life to some extent, with 37% citing interference to a large extent. In those with severe pain, 59% and 29% cited interference to a large extent and to some extent, respectively; with moderate PI, 16% of sufferers cited interference to a large extent and 52% to some extent.

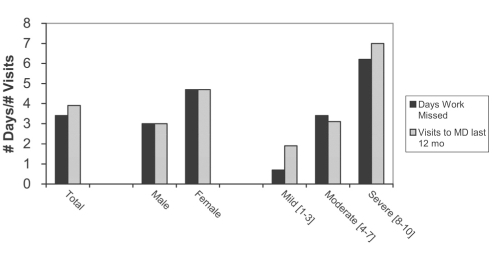

CP patients reporting all pain intensities visited their doctor specifically because of pain an average of 3.9 times per year. This increased with increasing PI from 1.9 times per year for mild pain (PI 1 to 3) to 3.1 times per year for moderate pain (PI 4 to 7) to seven times per year in patients with severe CP (PI 8 to 10). However, 16% of those suffering severe pain had not seen a doctor about their pain in the preceding year. The reported frequency of visits is higher in women (n=4.7) than in men (n=3.0). In the population reporting CP, of those who were gainfully employed (n=197), pain caused an average of 3.4 missed work days, with patients suffering severe pain missing an average of 6.2 days per year (Figure 2). In 2001, a subset of CP sufferers assessed for impact of pain reported that the mean number of days they were unable to work was 9.3; however, these data cannot be compared due to methodological differences.

Figure 2).

Economic impact of chronic pain. Patients reported their annual number of days of work missed as result of pain, and their annual number of visits to a primary care practitioner due to pain, subcategorized by sex and degree of pain intensity

Physician survey

Sample:

A total of 100 PCPs, representative of regional distribution, contributed to the study. In total, 57% of participants (45% male, 12% female) had been in practice for at least 20 years; 27% (21% male, 6% female) had been practicing for 10 to 19 years and 10% (11% male, 5% female) had been in practice for less than 10 years. All analyses and comparisons to the CCPSI were conducted between the 100 respondents in the current survey and the 70 PCPs responding in the 2001 survey (30 palliative care physicians from 2001 were excluded). While the sampling parameters were similar, the randomization process made it unlikely that a significant number of individual physicians participated in both the CCPSI and the CCPSII surveys.

Prevalence and impact on practice:

Physicians surveyed estimated the mean number of patients seen per month for moderate to severe pain (all types) at 58 (median 50 patients; range five to 300 patients) (it is unknown what percentage of their total practice this represents). Eighty-five per cent of patients being treated for long-term CP suffered CNCP, with only 15% suffering cancer pain, unchanged from 2001 (83% CNCP, 17% cancer pain). Of new CNCP patients in 2004, 16% were seen for the first time or were new to the practice, compared with 12% of cancer pain patients. All further data collected referred only to CNCP patients. The average number of prescriptions for CNCP per PCP was 57 per month. Physicians reported that patients suffering moderate to severe CNCP make an average of 10.5 office visits per year (median 10 visits) (in contrast to the three to seven visits per year selfreported by patients). Fully 48% of these patients visited the physician at least 11 times per year, and 19% made 20 or more office visits per year. No similar data were collected in the 2001 survey.

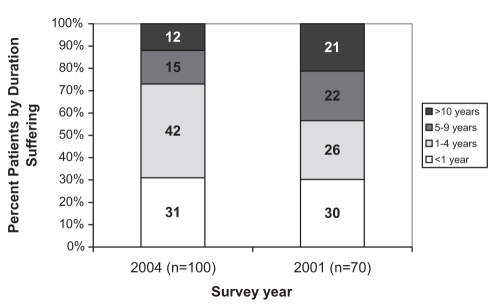

Pain assessment:

Of patients seen for CNCP, 67% were categorized as suffering from moderate to severe pain (23% severe, 44% moderate), with 33% suffering mild pain. This was essentially unchanged from 2001 (22% severe, 43% moderate and 35% mild). On average, PCPs reported that patients suffered from moderate to severe levels of pain for 3.4 years, versus 4.6 years in 2001 (P=0.045); 27% suffered at this PI for more than five years, versus 43% in 2001 (P=0.037) (Figure 3).

Figure 3).

Duration of suffering in patients having moderate to severe chronic noncancer pain (years) reported by primary care practitioners

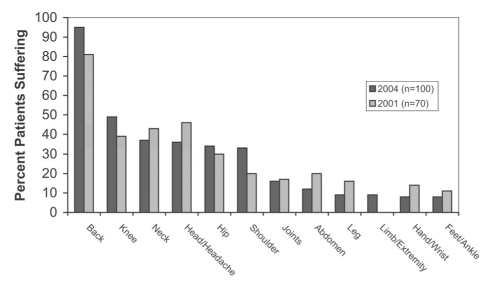

Pain causation and location:

Overall, the most frequent causes for CNCP were the various arthritis and inflammatory conditions (31%), low back or spinal conditions (21%), injury and postoperative sequelae (13%), migraine or headache (11%), neuropathic or neurological problems (11%) and soft tissue pain (8%). For 19% of CNCP patients, no cause was obvious. Although in 2001, physicians were asked to cite the “most frequent causes of pain”, compared with 2004, when the question referred to “the cause of pain in the last patient you saw”, the key drivers were similar, with low back pain, arthritis, headache and fibromyalgia being most notable, in decreasing order of frequency. Physicians reported that patients primarily complained of CP located in the back (95%), significantly increased from 81% in 2001 (P<0.05). Other sites of pain frequently cited (Figure 4) were knees (49% in 2004 versus 39% in 2001), neck (37% versus 43%), head (36% versus 46%), hips (34% versus 30%) and shoulders (33% versus 20%) (not significant).

Figure 4).

Body sites of chronic noncancer pain. Percent of patients reporting pain at each site (physician survey)

Assessment before prescribing:

In assessing a new CNCP patient, most PCPs took a detailed medical history (79% in all patients and 19% in most patients), history of the pain condition (86% all versus 13% most) and its past treatment (62% all versus 33% most), reviewed current treatment (84% all versus 14% most), performed a physical examination (84% all versus 13% most) and evaluated relatedness to work injury or accident (65% all versus 27% most): 87% of PCPs documented all these details in the patient chart. Before prescribing any opioid, PCPs checked for potential interactions of analgesics with existing medications (61% all versus 32% most) and excluded risk factors including those of addiction and other complications (53% all versus 42% most). PCPs also attempted to set appropriate patient expectations (30% all versus 44% most) and set patient-customized treatment goals (27% all versus 46% most). PCPs discussed the treatment options with 83% of patients.

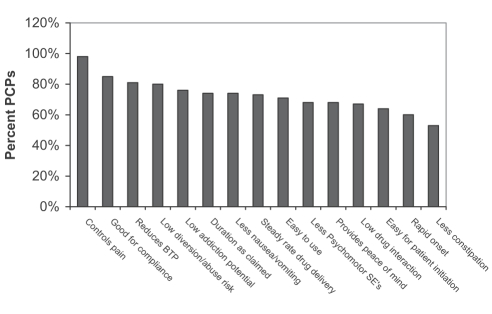

Attributes of opioids that influence prescribing:

PCPs were asked which attributes of a strong opioid influenced their analgesic prescribing for moderate to severe CNCP. The most important attributes were: pain control (98%); features promoting compliance (85%); reduction of breakthrough pain (81%); low potential for abuse or diversion, defined as ‘selling or trafficking’ (80%); and low potential for addiction (76%). Other important attributes included duration of action, decreased nausea and vomiting, steady rate of drug delivery and ease of use (Figure 5). This information was not captured in the 2001 survey.

Figure 5).

Important attributes primary care practitioners (PCPs) consider when choosing a strong opioid to prescribe for moderate to severe chronic noncancer pain. BTP Breakthrough pain; SEs Side effects

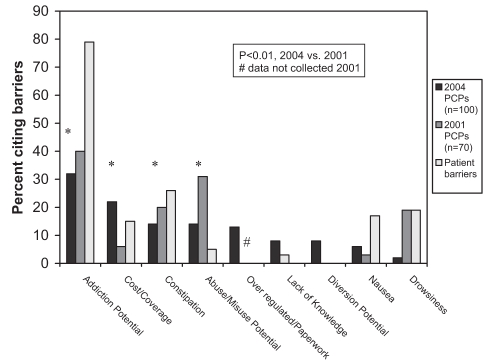

PCP perception of patient attitudes toward the use of opioids:

Of CNCP patients whom PCPs believed would benefit from analgesics more potent than codeine, PCPs estimated that, on average, 27% would be unwilling to receive strong opioids. Physicians believed that patients’ reluctance was primarily due to concerns about the potential for addiction (79%) and side effects (54%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6).

Perceived barriers to prescribing strong opioids: primary care practicioners (PCPs), 2004 versus 2001, and patients

PCP barriers to prescribing strong opioids:

PCPs identified the key barriers to their prescribing of strong opioids, in descending order of importance, as the potential for addiction, costs and formulary or insurance coverage, constipation, potential for misuse or abuse, as well as the administrative burden of associated paperwork (not included in 2001 survey) (Figure 6).

Standards of care in Canada: How does this translate into practice?

Actual use of the different analgesic classes for moderate to severe CNCP did not change between 2001 and 2004. Combining all first-line, second-line and third-line treatments, opioids of some type are frequently prescribed (83% versus 84%, net 2004 versus 2001), as are NSAIDs (43% versus 41%) (note data were collected before the withdrawal of several selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors for safety concerns in late 2004), acetaminophen (18% versus 20%) and antidepressants (11%; not captured in 2001). However, the preference for first-line treatment changed significantly, with opioids preferred for (net) 51% of patients in 2004 versus 30% in 2001 (P=0.009). Conversely, the preference for NSAIDs and acetaminophen decreased, although not significantly (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Analgesic therapy in moderate to severe chronic noncancer pain

| Analgesic therapy | Preferred first-line therapy

|

Actual first-, second-and third-line total

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004

(n=100), % |

2001

(n=70), % |

2004

(n=100), % |

2001

(n=70), % |

|

| Net opioids | 51* | 30 | 83 | 84 |

| Codeine (all combinations) | 23 | 19 | 43 | 60 |

| Oxycodones | 11 | 4 | 33 | 31 |

| Morphines (all) | 10 | 4 | 41 | 37 |

| Other opioids† | 7 | 3 | 38 | 19 |

| Net NSAIDs | 17 | 29 | 43 | 41 |

| Net acetaminophen | 13 | 20 | 11 | NA |

P=0.009 versus 2001;

Hydromorphone, fentanyl transdermal reservoir patch. NA Data not collected in 2001; NSAIDs Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Strong analgesics (ie, opioids stronger than codeine) were prescribed, on average, to 37% of these patients in 2004 versus 31% in 2001, with codeine combination products the most frequently prescribed medication. Because this question was asked differently between the two surveys, the data (categorical in 2001 and continuous in 2004) may not be compared statistically. The prescription of these strong opioids was distributed as follows in 2004: first-line treatment, 28%; second-line treatment, 39%; and third-line treatment, 34%. In 2001, this distribution was 28%, 30% and 42%, respectively. Initial prescriptions were generally for short-acting strong opioids in 60% of cases; eventually, 62% of these patients are switched to long-acting formulations.

Assessment of treatment success:

A number of strategies were used by PCPs to evaluate the success of therapy. For all or most patients, opioid use patterns (88%) (prescription refills, compliance, etc), functional improvements (80%) and quality of life improvements (75%) were tracked. To a lesser extent, PCPs set the requirements for reporting of breakthrough pain (59%), prescribe both long-acting and short-acting analgesics to manage breakthrough pain (57%), document the ‘5 As’ (Abuse, Aberration, Adverse events, Activity, Attitudes) in the chart (47%) and contact the patient to assess their status (31%). Essentially, all PCPs (99%) scheduled a follow-up visit to assess the success of therapy, with a mean follow-up frequency of 21 days.

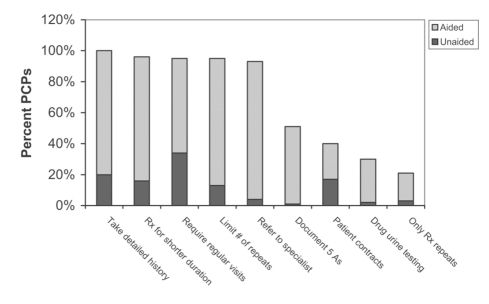

Minimizing the risk of abuse:

PCPs were asked about steps taken to minimize the risk of misuse, abuse or drug diversion. Steps noted included the taking of detailed histories (80% response aided with specific prompts versus 20% unaided or spontaneous, ‘top-of-mind’ responses), prescriptions for short durations (80% aided versus 16% unaided), mandating regular follow-up visits (61% aided versus 34% unaided), limiting the number of prescription repeats (82% aided versus 13% unaided) and referring to a specialist (89% aided versus 4% unaided). Patient contracts were used by 23% (aided) versus 17% (unaided) of PCPs, and 28% (aided) versus 2% (unaided) claimed to employ urine drug testing (Figure 7).

Figure 7).

Steps primary care practitioners (PCPs) take to minimize the risk of abuse or misuse: Percent reporting, unaided and aided responses. 5 As Abuse, Aberration, Adverse events, Activity, Attitudes; Rx Prescribe

Impact of poor pain management:

In 2001, 36% of PCPs considered moderate to severe CNCP to be well managed (only 3% considered CNCP to be very well managed); in 2004, this was similar, at 40%, with only 1% considering CNCP to be very well managed. Hence, PCPs perceive that pain is not well managed in 60% of CNCP patients. Physicians cited the consequences of poorly managed CP (2004 versus 2001, respectively) as needless patient suffering (72% versus 67%), economic costs or loss of productivity (37% versus 13%), poor quality of life (30%; not asked in 2001), emotional problems or depression (18% versus 22%) and frequent visits to the doctor (15% versus 27%). When prompted about the impact of specific aspects, PCPs reported a significant impact of poorly managed CNCP on patient suffering (98%), caregiver burden (85%), health care costs (83%), physician burden (80%), economic productivity (80%) and aberrant drug-taking behaviours (70%). Four of 10 PCPs suggested that enhanced educational programs would improve their management of CNCP. Additional suggestions for improvement included more pain clinics and enhanced patient or public education.

DISCUSSION

The present study confirms that CP remains a major challenge to the Canadian health care system. The prevalence of CP in Canada was largely unchanged in 2004 compared with 2001 (25% versus 29%). There were no major changes regionally in prevalence, with Quebec retaining the lowest prevalence and the Atlantic provinces the highest. This possibly reflects a high physician comfort level treating CP in Quebec, confirmed by higher prescribing patterns (Compuscript MAT 2005, IMS Health Canada). The mean duration of CP reported was statistically decreased from 10.7 to 9.8 years, perhaps reflecting better or more timely pain management; however, this remains a substantial timeframe for suffering. Additionally, 88% of individuals suffering CNCP reported a moderate to severe PI, with a shift showing less moderate pain and more severe pain (P<0.001) compared with 2001. In CP sufferers, the reported use of prescription analgesics increased from 38% to 49% (P=0.005), yet in those with severe pain, fully 28% did not take any prescription pain medication. Pain severity likely contributes to the striking impact of pain with respect to interference with day-to-day life, the frequency of physician visits and the economic impact of missed work days. Comparable data have emerged from a similarly conducted European survey (13), in which 52% of CP sufferers were currently taking prescription medicines, but 21% had never taken any prescribed analgesics. The duration of suffering in Europe was long as well, at a median of 7.0 years (range 4.9 to 9.6 years) (versus the currently reported 6.0 years in Canada).

PCPs increasingly are the front line for the management of CNCP in Canada and elsewhere (28,29). More than two-thirds of CNCP patients seen by PCPs had moderate to severe PI, unchanged since 2001, although the duration of patient suffering, estimated by the PCPs, was reduced (3.4 versus 4.6 years). This is in contrast to CP patients’ self-reporting pain of a much longer duration (mean 9.8 years); however, it is more congruent with the patient-reported median of 6.0 years. Back pain was the predominant complaint (95%) and was significantly increased in frequency in 2004 over 2001 (81%). The most frequent causes of CP are from arthritis and other inflammatory conditions, similar to in Europe (13).

Undertreatment of CP remains a concern in many countries. In parts of the United States, one in five sufferers of CP do not even seek medical care for their pain (30). A difficult to quantify barrier to care is the subjective and nonverifiable nature of pain itself and, occasionally, the lack of obvious causative factors (19% in the current study), making assessment difficult for the physician (7). Lack of efficacy of opioids at doses used, side effects and poor compliance also contribute to this situation (3).

Pharmacotherapy for moderate to severe CNCP remains challenging from several perspectives. Because stronger analgesics, which may be necessary to control this pain, carry the burden of side effects and concerns of addiction, both patients and PCPs have fears related to long-term use of strong opioids. When asked about prescribing opioids as first-line therapy for moderate to severe CNCP, the PCPs surveyed cited a significantly increased preference for strong opioids, from 30% in 2001 to 51% in 2004. However, their actual use of strong opioids in the same population increased only modestly from 31% to 37% over the same time period (not significant). This may relate to PCPs’ continuing (albeit reduced) concerns relating to potential for patient addiction, abuse, misuse and diversion; fears of regulatory sanctions; and media reports. These remained the primary barriers to the prescribing of strong opioids in the management of moderate to severe CNCP, despite some improvements from 2001. Additionally, PCPs perceived that patients are reluctant to take opioids, mainly because of the potential for addiction and side effects. Although PCPs appear to have less concern about addiction and misuse of opioids in 2004 than in 2001, it is clear that opiophobia, concerns about medication costs and the administrative requirements for prescribing scheduled medications contribute to suboptimal use of opioids in managing CNCP. In choosing strong opioids for their patients, PCPs cited pain control, ease of compliance, reduction of breakthrough pain and low potential for diversion or abuse as the most important attributes to consider. In general, PCPs prefer to initiate opioid therapy with short-acting formulations and later switch to long-acting formulations.

The use of opioids in CNCP remains controversial (31), despite studies showing these medications to be generally safe and effective when used rationally (32,33) and in accordance the recommendations of multiple guidelines. It is important to educate physicians to be watchful of common pitfalls in prescribing opioids, including indicators of inadequate pain control, early signs of problematic use of opioids, and outright indicators of misuse and addiction (20,21). Professional association guidelines are valuable to teach and to protect both patients and physicians. From both the patient and PCP perspective, managing opioid side effects is critical to good pain management in CNCP (22).

While preference for the use of NSAIDs was decreased from 2001 to 2004, the actual use was not. It is important to note that the 2004 survey preceded the withdrawal of several cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors due to concerns of mortality risk in select patients with cardiovascular disease. These products have been replaced mainly with older, well-known NSAIDs (34). However, significant safety concerns relating to prostaglandin-related organ toxicity (mainly renal and hepatic) and gastrointestinal bleeding remain with long-term NSAID use. Future drug development research is needed to fill this gap in the analgesic armamentarium.

The survey results show that current Canadian standards of care are congruent with professional society guidelines for moderate to severe CNCP. This includes screening for opioid management issues, initiating treatment with short-acting opioids before switching to the preferred long-acting opioids and routinely assessing benefits of treatment, including functional improvements. Steps taken to minimize the risk of drug abuse or misuse may include limiting repeat prescriptions without office visits, the use of patient contracts and urine drug screening. The use of contracts was low, but it may be expected that PCPs concerned about individual patient misuse are referring these patients to specialists who are more likely to require trilateral contracts including the patient and PCP (35). However, a recent survey of Canadian anesthesiologists (36) revealed that fewer than one-half of these specialists incorporate opioid agreements in their CP practices. PCPs also are clearly aware of urine screening as a management tool (although there are limitations depending on the assays used and detection thresholds set) to assess compliance and detect diversion.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the current study show improvements in the care of CNCP patients, but reveal that the optimal treatment of CNCP remains a challenge to Canadian PCPs. Although increased prescribing of opioids was seen for the management of CNCP, this remained negatively influenced by PCP concerns regarding addiction and abuse. Canadian PCPs, in general, are standardizing pain assessment, treatment approaches and evaluation of treatment success, and have begun to use specific tools to prevent abuse and diversion. This is in accordance with multiple professional society guidelines, including those of the Canadian Pain Society. There remains, however, room for improvement and better standardization to further optimize the management of CNCP and its secondary effects on patient quality of life, while at the same time minimizing the burden on the health care system and the economy.

Acknowledgments

Supported by an unrestricted grant from Janssen-Ortho Inc, Toronto, Ontario.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE: Drs Boulanger, Clark and Squire have acted as paid speakers on behalf of Janssen-Ortho at various continuing health education meetings and professional congresses. Dr Clark has participated as an investigator in paid clinical research conducted for Janssen-Ortho. Dr Horbay is a paid employee of Janssen-Ortho, directing Clinical Research. Mr Cui is a paid employee of Janssen-Ortho, managing Business Analytics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Morley-Forster MK. Chronic Pain in Canada – prevalence, treatment, impact and the role of opioid analgesia. Pain Res Manage. 2002;7:179–84. doi: 10.1155/2002/323085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Den Kerkhof EG, Hopman WM, Towheed TE, Anastassiades TP, Goldstein DH, Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study Research Group The impact of sampling and measurement on the prevalence of self-reported pain in Canada. Pain Res Manage. 2003;8:157–63. doi: 10.1155/2003/493047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stannard C, Johnson M. Chronic pain management – can we do better? An interview-based survey in primary care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19:703–6. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus DA. Managing chronic pain in the primary care setting. Amer Fam Physician. 2002;66:36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain and frequent use of health care. Pain. 2004;111:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caudhill-Slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescriptions for musculoskeletal pain in US: 1980 vs. 2000. Pain. 2004;109:514–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porcelli MJ.Why are our patients still in pain? Finding a balance in treating patients for nonmalignant pain J Am Osteopath Assoc 200410473–5.(Erratum in 2004;104:147). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunton S. Approach to assessment and diagnosis of chronic pain. J Fam Pract. 2004;53(Suppl 10):S3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jovey RD, Ennis J, Gardner-Nix J, et al. Use of opioid analgesics for the treatment of chronic noncancer pain – A consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society, 2002. Pain Res Manage. 2003;8(Suppl A):3A–14A. doi: 10.1155/2003/436716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Geriatrics Society Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons The management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(6 Suppl):S205–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.50.6s.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Pain Society Recommendations for the appropriate use of opioids for persistent non-cancer pain A consensus statement prepared on behalf of the Pain Society, The Royal College of Anaesthetists, The Royal College of General Practitioners and the Royal College of Psychiatrists. March 2004. <www.britishpainsociety.org/opioids_doc_2004.pdf> (Version current January 16, 2007)

- 12.Hasselstrom J, Liu-Palmgren J, Rasjo-Wraak G. Prevalence of pain in general practice. Eur J Pain. 2002;6:375–85. doi: 10.1016/s1090-3801(02)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brevik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:287–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain A consensus statement from the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . Cancer Pain Relief, With a Guide to Opioid Availability. 2nd edn. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynch ME, Watson CP. The pharmacotherapy of chronic pain: A review. Pain Res Manage. 2006;11:11–38. doi: 10.1155/2006/642568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morley-Forster PK, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Moulin DE. Attitudes toward opioid use for chronic pain: A Canadian physician survey. Pain Res Manage. 2003;8:189–94. doi: 10.1155/2003/184247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan JP. American opiophobia: Customary underutilization of opioid analgesics. Adv Alcohol Subst Abuse. 1985;5:163–73. doi: 10.1300/J251v05n01_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett DS, Carr DB. Opiophobia as a barrier to the treatment of pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2002;16:105–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher R. Opioids in chronic pain management: Navigating the clinical and regulatory challenges. J Fam Pract. 2004;53(Suppl 10):S23–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breivik H. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain, indications and controversies. Eur J Pain. 2005;9:127–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNicol E, Horowicz-Mehler N, Fisk RA, et al. Management of opioid side effects in cancer-related and chronic noncancer pain: A systematic review. J Pain. 2003;4:231–56. doi: 10.1016/s1526-5900(03)00556-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watson CP, Watt-Watson JH, Chipman ML. Chronic noncancer pain and the long term utility of opioids. Pain Res Manag. 2004;9:19–24. doi: 10.1155/2004/304094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutstein HB, Akil H. Opioid analgesics. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, editors. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 10th edn. Toronto: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 569–620. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajagopal A, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Palmer JL, Kaur G, Bruera E. Symptomatic hypogonadism in male survivors of cancer with exposure to opioids. Cancer. 2004;100:851–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cicero TJ, Bell RD, Wiest WG, Allison JH, Polakoski K, Robbins E. Function of the male sex organs in heroin and methadone users. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:882–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197504242921703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bliesener N, Albrecht S, Schwager A, Weckbecker K, Lichtermann D, Kingmuller D. Plasma testosterone and sexual function in men receiving buprenorphine maintenance for opioid dependence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:203–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcus D. Practical approach to the management of chronic pain. Compr Ther. 2005;31:40–9. doi: 10.1385/comp:31:1:040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid MC, Engles-Horton LL, Weber MB, Kerns RD, Rogers EL, O’Connor PG. Use of opioid medications for chronic noncancer pain syndromes primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:173–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watkins E, Wollan PC, Melton LJ, III, Yawn BP. Silent pain sufferers. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:167–71. doi: 10.4065/81.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bloodworth D. Issues in opioid management. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(Suppl 3):S42–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarberg B. Contemporary management of chronic pain disorders. J Fam Pract. 2004;53(Suppl 10):S11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dews TE, Mekhail N. Safe use of opioids in chronic noncancer pain. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;77:897–904. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.71.11.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider JP. Chronic pain management in older adults: With coxibs under fire, what now? Geriatrics. 2005;60:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fishman SM, Mahajan G, Jung SW, Wilsey BL. The trilateral opioid contract. Bridging the pain clinic and the primary care physician through the opioid contract. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:335–44. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng PW, Castano ED. Survey of chronic pain practice by anesthesiologists in Canada. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:383–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03016281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]