Abstract

Background

Controversy exists regarding the benefits and risks of combined spinal-epidural compared with epidural analgesia (CSE, EPID) for labor analgesia. We hypothesized that CSE would result in fewer patient requests for top-up doses compared to EPID.

Methods

One hundred ASA PS 1 or 2 parous women at term in early labor (<5 cm cervical dilation) requesting analgesia were randomized in double-blind fashion to the EPID group (epidural bupivacaine 2.5 mg/mL, 3 ml, followed by bupivacaine 1.25 mg/mL, 10 ml with fentanyl 50 μg) or the CSE group (intrathecal bupivacaine 2.5 mg with fentanyl 25 μg). Both groups received identical infusions of bupivacaine 0.625 mg/mL with fentanyl 2 μg/ml at 12 ml/hr. The primary outcome variable was the number of top-up doses requested to treat breakthrough pain.

Results

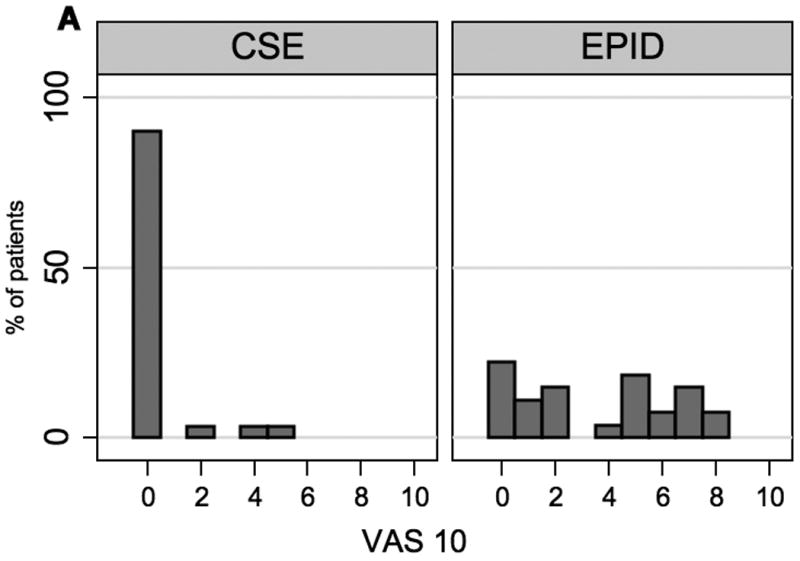

There was no significant difference between the two groups in the percentage of patients requesting top-up doses (44% CSE vs. 51% EPID; 95% confidence interval of the difference -28% to +14%) nor in the need for multiple top-up doses (14% CSE vs. 15% EPID). VAS scores were lower in the CSE group compared to the epidural group at 10 minutes after initiation of analgesia [median (IQR) 0 cm (0, 0) vs. 4 cm (1, 6) respectively, p < 0.001] and at 30 minutes [0 cm (0, 0) vs. 0 cm (0, 1), respectively, p=0.03].

Conclusions

We did not find a difference in the need for top-up doses in parous patients; however, CSE provided better analgesia in the first 30 minutes compared to EPID.

Introduction

The combined spinal-epidural technique (CSE) is being increasingly used for labor analgesia. The CSE technique offers several potential advantages over standard epidural analgesia (EPID), including more rapid onset of analgesia and greater patient satisfaction.(1) One randomized, blinded clinical trial reported that patients with CSE in relatively early labor underwent significantly more rapid cervical dilation than the women receiving epidurals.(2) Other studies, however, have failed to reproduce these findings.(3,4) A study of factors associated with breakthrough pain found that parturients who received CSE were less likely to experience recurrent breakthrough pain(5), and a recent Cochrane report suggests that CSE is associated with a decreased need for rescue analgesia (1). Whether CSE provides more effective labor analgesia with acceptable risk still remains controversial.

A major question is whether CSE provides better analgesia throughout the entire course of labor. In an attempt to assess this issue, we conducted a non-randomized, non-blinded, prospective study of 211 patients in whom analgesia was initiated using either an epidural or CSE technique at the discretion of the anesthesiologist, and found a large difference between the two techniques in the number of times a patient requested additional pain medication (top-up doses). Sixty percent of the patients in the epidural group needed top-up doses compared to 35% in the CSE group (p<0.01, unpublished data). However, the results may have been biased since the CSE group had fewer nulliparous patients, greater cervical dilation at the time of analgesia, and had a shorter time to delivery. We performed the current randomized, double-blinded, prospective study in order to eliminate the possible selection bias in our prior study. We hypothesized that CSE would result in fewer patient requests for top-up doses compared to epidural analgesia in parous women in whom analgesia was initiated in early labor.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center, and written, informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Patients with one prior vaginal delivery who were at least 18 years of age with a single gestation in vertex presentation at term (37 – 42 weeks' gestation), ASA PS 1 or 2, and were expected to have a vaginal delivery were eligible for enrollment. Only patients requesting neuraxial analgesia with cervical dilation < 5 cm were eligible for participation in this study. Patients were excluded if they had a history of severe scoliosis, were taking other pain medications, had a body mass index >45 kg/m2, or if they had any contraindication to neuraxial analgesia.

Patients were assigned to EPID or CSE group by a computer-generated randomization table. Group assignments were placed in opaque envelopes, opened by the anesthesiologist performing the analgesic technique just before starting the procedure. The patients and nurses caring for the patients were blinded to the technique, as was the study coordinator assessing analgesic, side effect, and outcome variables. The anesthesiologist initiating the analgesia was necessarily aware of the group assignment, but was not involved in the data collection for the study or the administration of top-up doses.

The CSE and epidural procedures followed a standard protocol. With the patient in the sitting position, the epidural space was identified at L3-4 or L4-5 with a 17-gauge Tuohy needle using a loss of resistance to air or saline technique. Patients randomized to epidural analgesia had a 19-gauge, multi-orifice epidural catheter inserted 4-5 cm into the epidural space. A 3 mL test dose of bupivacaine 2.5 mg/mL was administered followed 5 minutes later by 10 ml of bupivacaine 1.25 mg/mL with fentanyl 50 μg. Patients randomized to CSE had a 27-gauge Whitacre needle placed into the subarachnoid space through the Tuohy needle. After free flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was ascertained, bupivacaine 2.5 mg and fentanyl 25 μg was injected, and the spinal needle was withdrawn. The epidural catheter was inserted and advanced 4-5 cm into the epidural space. All epidural catheters were aspirated for blood and CSF at the time of placement. A continuous infusion of bupivacaine 0.625 mg/mL with fentanyl 2 μg/ml at 12 ml/h was initiated within 15 minutes of administration of the spinal or epidural dose and maintained in both groups until delivery. After the epidural catheter was secured, all patients were placed in the supine position with left uterine displacement. A non-invasive blood pressure cuff was placed on the upper extremity.

If the patient did not have satisfactory analgesia 15 minutes after the epidural loading dose or spinal dose, an additional 5 ml bupivacaine 2.5 mg/mL was administered via the epidural catheter. This extra dose was not considered a top-up dose. Women were excluded from data further collection if they continued to complain of pain 30 minutes after initiation of neuraxial analgesia. Women in whom epidural catheter replacement was necessary at any time because of analgesia failure were also excluded from data collection and analysis.

During labor, upon patient request and confirmation that the visual analog scale pain score was greater than 3 cm during the previous contraction (VAS: unmarked 10 cm line), additional epidural medication (top-up doses) were given according to a standard protocol. The first top-up dose consisted of 6 ml bupivacaine 12.5 mg and fentanyl 50 μg. After 15 minutes, if the patient was still uncomfortable, an additional 5 ml bupivacaine 2.5 mg/mL was administered. This dose was not considered a second top-up dose. After another 15 minutes, if the patient still needed additional medication, she was given 5 ml lidocaine 20 mg/mL in order to help determine if the epidural catheter was functioning. If analgesia was not achieved after the 5 ml dose of lidocaine 20 mg/mL, the catheter was classified as a failure, and the patient was eliminated from analysis. Throughout labor, if study patients requested a second or third top-up dose, they were given 5 ml bupivacaine2.5 mg/mL with or without fentanyl 50 μg at the discretion of the anesthesiologist taking care of the patient.

A research coordinator who was blinded to group assignment assessed the patients and recorded the data. The primary outcome variable was the percentage of subjects in each group who received top-up doses. The time of initiation of analgesia (completion of the 10 ml epidural loading dose or intrathecal injection in the respective groups), the first top-up dose, additional top-up doses, full cervical dilation, and delivery were recorded. Pain was assessed by VAS score. Patients were asked to mark their pain on an unmarked 10 cm line anchored at one end with “no pain” and at other end with “worst pain imaginable” prior to epidural or CSE initiation, every 10 minutes after the initial injection for a total of 30 minutes, and every hour for the next 6 hours. At each of these times, maternal blood pressure and fetal heart rate were evaluated, and sensory level to ice was measured. Pruritus was assessed on a 4-point scale as none (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3) (requiring treatment). Motor block was measured on a 4-point scale as no weakness (0), difficulty with straight leg raise (1), no straight leg raise or knee extension (2), or weak at hip, knee and ankle (3). Similar assessments were made before and 10, 20 and 30 minutes after each top-up dose. Ephedrine and/or phenylephrine at the discretion of the anesthesiologist were used to treat maternal blood pressure 20% lower than baseline.

Additional data obtained included maternal age, height, weight, gestational age, parity, use of oxytocin, cervical dilation at analgesia initiation (assessed within the last hour before request of analgesia), mode of delivery and neonatal weight. One hour after delivery patients were asked to rate their analgesia during the first and second stages of labor as excellent, good, fair or poor. Women were also asked whether they would be willing to have the same technique performed during future deliveries.

The required sample size was estimated based on the data from our non-randomized study in which parous patients had a 27% rate of top-up dose requests with CSE and 52% with epidural analgesia. We calculated our group sample size to be 50 for 80% power to detect such a difference at the p<0.05 level. Data are expressed as percentages, mean ± standard deviation, or median with interquartile ranges. Statistical analysis was carried out using Stata SE 8.0 for Macintosh (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). Demographics were analyzed with Student's t and χ2 tests. The proportion of subjects in each group requiring top-up doses or noting side effects was compared by χ2 test. Time data, sensory levels, and VAS scores were not normally distributed so the non-parametric Mann Whitney test was used. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to examine differences in time to delivery and time to first top-up dose. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

One hundred patients were enrolled and randomized in this study, and our analysis contains 84 subjects. Nine patients were excluded due to protocol violations (five in the CSE group, four in the EPID group), two patients had missing data (one CSE, one EPID group), 2 spinal anesthetics resulted in only partial drug administration (all CSE group), and 3 epidural catheters failed (all EPID group). There were 43 patients who received CSE and 41 who received epidural analgesia.

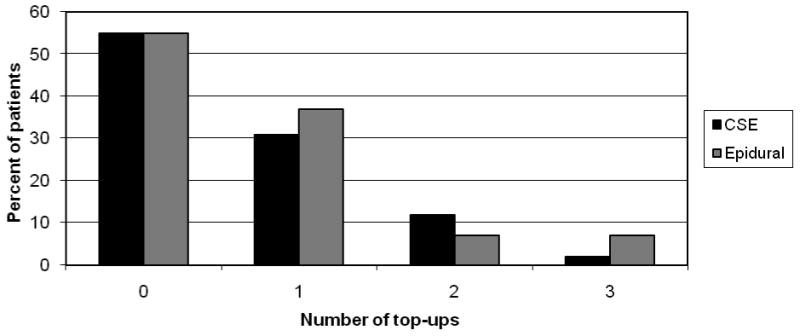

There were no differences in patient characteristics (Table 1) or obstetric management and outcome (Table 2) between the groups. Nineteen (44%) patients in the CSE group compared to 21 (51%) in the epidural group required top-up doses which was not statistically significantly different. The difference in the rate of top-ups is 7% (95% CI on the difference: -28% to +14%). Six (14%) women in the CSE group versus six (15%) in the epidural group required more than one top-up dose (Figure 1). One patient in the CSE group and two patients in the EPID group needed an additional 5ml bupivacaine 2.5 mg/mL 20 to 30 minutes after her first top-up dose and this was not considered a second top-up dose. There were 4 cesarean deliveries in the CSE group and 5 in the EPID group. None of the cesareans were performed in the first 5 hours after study entry. All but three of the first top ups doses occurred within the first 5 hours.

Table 1.

Maternal demographics

| CSE | Epidural | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 43 | 41 |

| Age (years) | 32 ± 6 | 31 ± 5 |

| Height (cm) | 163 ± 5 | 163 ± 7 |

| Weight (kg) | 78 ± 12 | 80 ± 15 |

| Parity =1 | 28 (65%) | 27 (66%) |

| Parity =2 | 12 (28%) | 8 (20%) |

| Parity ≥3 | 3 (7%) | 6 (14%) |

Data presented as mean ± SD or n (%) as indicated. There are no significant differences between groups.

Table 2.

Obstetrical management and outcome

| CSE | Epidural | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 43 | 41 |

| Cervical dilation at entry (cm) | 4 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 |

| Use of oxytocin | 36 (84%) | 31 (76%) |

| Cesarean delivery | 4 (9%) | 5 (12%) |

| Neonatal weight (g) | 3394±300 | 3515±360 |

Data presented as mean ± SD or n (%) as indicated. There are no significant differences between groups.

Figure 1.

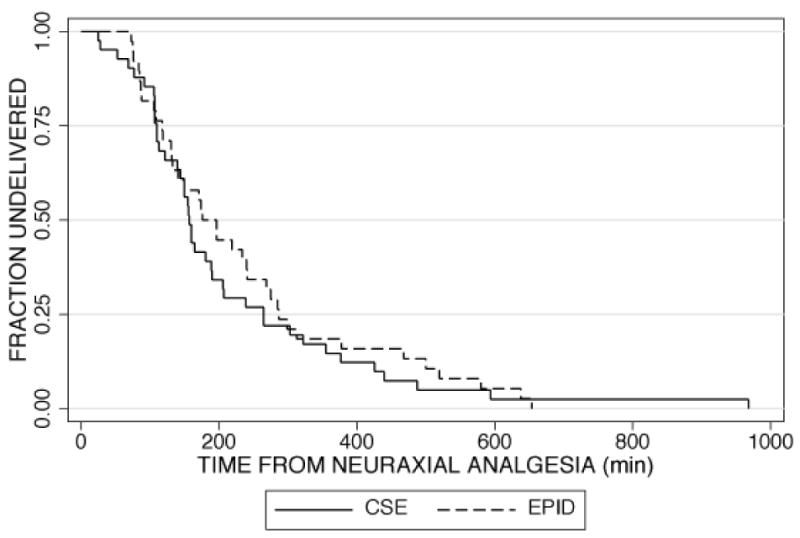

The median time from initiation of analgesia to patient request for the first top-up dose was 144 (129, 204) minutes in the CSE group and 160 (70, 239) minutes in the epidural group (p=0.69). There was no difference between the groups in the time from analgesia to full dilation [147 min (94, 234) CSE versus 133 min (85, 232) epidural] or from analgesia to delivery [159 (110, 265) CSE versus 197 (119, 287] (Figure 2). The patients who received CSE had lower VAS scores at both 10 minutes and 30 minutes after initiation of analgesia compared to women in the epidural group. (Figure 3)

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

While baseline systolic blood pressures were similar, at 10 and 20 minutes after analgesia, patients in the CSE group had lower systolic blood pressure than those in the epidural group. More women in the CSE group had moderate or severe pruritus in the first 30 minutes after analgesia compared to the epidural group. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Side effects

| CSE | Epidural | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 43 | 41 | |

| Systolic BP 10 min (mmHg) | 109 ± 12 | 117 ± 15 | 0.004 |

| Systolic BP 20 min (mmHg) | 110 ± 12 | 115 ± 13 | 0.02 |

| Systolic BP 30 min (mmHg) | 111 ± 11 | 115 ± 13 | 0.10 |

| Use of vasopressors | 7 (16%) | 0 | 0.01 |

| Motor block* | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1.00 |

| Pruritus# | 15 (35%) | 3 (7%) | 0.003 |

| Sensory level 30 min | T4 (T2-T8) | T7 (T6-T8) | < 0.001 |

Data presented as mean ± SD, n (%), and median with interquartile range as indicated.

Bromage score greater than 0.

Moderate and severe pruritus.

There were no differences between the groups in satisfaction ratings of pain relief in both the first and second stages of labor. Ninety-eight percent of patients stated that they would have the same procedure in the future.

Discussion

In order to determine whether the CSE technique provides more effective labor analgesia than an epidural technique we gathered data on physician administered top-up doses, assuming that the lack of requests for top-up doses is indicative of analgesia quality. We decided to focus on parous women since few studies of labor analgesia have looked at this patient group, and many clinicians choose CSE for parous women. We limited our study to women requesting neuraxial analgesia in early labor, because parous women requesting analgesia in the second stage of labor are most likely to deliver without requesting any top-up due to the rapid nature of their labor and delivery. Several studies have shown both faster onset of effective analgesia(1) and lower VAS scores in the first 15 to 20 minutes after CSE compared to epidural analgesia.(6,7)

Overall, our findings suggest that while there is a significant difference between CSE and epidural analgesia during the first 30 minutes, the need for additional top-ups does not seem to be different throughout the entire course of labor and delivery when analgesia is maintained with a continuous epidural infusion. The median time from initiation of analgesia to delivery is 38 minutes less in women who received CSE compared to those who received epidural analgesia. While this did not achieve statistical significance, our study was not powered to examine analgesia initiation-delivery intervals. Some studies have found a shorter analgesia-delivery interval in patients who receive CSE,(2) but other studies(3,4,8) and a recent meta-analysis(9) have concluded that there is no difference in labor progress between the two techniques. A recent large, randomized clinical trial showed that patients given CSE analgesia at <4 cm dilation delivered faster than patients given systemic opioids followed by epidural analgesia at >4 cm dilation.(10) This is an area that requires further investigation.

CSE analgesia for labor has been associated with a higher incidence of hypotension and pruritus,(1,6,11) and our study confirms these findings. Despite these side effects, CSE is preferred over standard epidural analgesia by many anesthesiologists and parturients because it provides rapid onset of reliable, high-quality analgesia with better sacral spread and is especially useful when analgesia is initiated in the late first stage or second stage of labor.

The question of whether CSE is associated with a lower incidence of break-through pain and fewer top-up doses compared to epidural analgesia for labor remains controversial even though maternal satisfaction with CSE appears higher.(6) A prospective observational study of over 1,500 parturients found parturients with CSE compared to epidural analgesia had fewer top-up dose requests; however, the CSE group had a higher proportion of parous patients in advanced labor.(11) In a randomized trial of 50 parturients, Hepner et al. found that the anesthesiologist was called to perform fewer interventions in the CSE compared to epidural analgesia group.(7) A recent randomized controlled trial of 250 laboring women found no difference in the number of top-up doses requested by patients in the CSE group compared to the epidural group, but these investigators performed the dural puncture without administering medication intrathecally.(12) Finally, a large (almost 20,000 parturients) retrospective study reported that the rate of catheter replacement and failure of anesthesia for cesarean delivery was lower in women who received CSE compared to epidural labor analgesia.(13)

The possible effect of a dural hole on the trans-dural movement of epidurally administered drug has been an area of interest since the use of the CSE technique for anesthesia and analgesia has become widespread. The factors that appear to promote drug transfer intrathecally include larger dural holes,(14,15) higher epidural pressure (as occurs with bolus injection),(16,17) and perhaps shorter time from dural puncture.(18) The time to first top-up dose request in our patients was approximately 2 hours. It is possible that this interval is too long to observe the salutary effects of dural puncture on drug transfer across the dura.

A limitation of our study conclusions is that the initial dose of spinal and epidural drugs used in this study may not be equipotent and of equal duration of action. Previous studies have shown the ED50 for epidural bupivacaine with fentanyl 60 μg is 6.8 mg(19) and the ED50 for intrathecal bupivacaine with fentanyl 25 μg is 0.85 mg.(20) If these are relevant to the current study, we used approximately three times the ED50 for both groups. The fact that we did not observe a difference in the time to first top-up dose request between the groups suggests that the duration of the spinal and epidural initial doses are not significantly different. Studies to establish the equipotent doses of spinal and epidural analgesia for labor are critical to further understanding any differences between the two techniques.

A further limitation to our study is that it is underpowered. We originally based our sample size analysis on unpublished data from our institution which showed a difference of 25% in the incidence of top-up doses between the CSE and epidural groups. If the real difference is smaller, we needed to have studied more patients to demonstrate a difference between groups. In addition, while we enrolled 100 patients, we only had complete data for 84. Both of these factors may contribute to our not finding a difference when one exists. However, this study does suggest that any difference that exists in terms of top-up dose requests is probably clinically insignificant.

Another limitation to our study is that it may not have been truly blinded. The nurses caring for the patients may have guessed which technique was administered based on the onset of analgesia as well as the presence of side effects. While we did our best to keep the patient blinded and the study coordinator who gathered the data was not present in the room until the procedure was completed, it may be impossible to complete a study of this nature with perfect blinding to different techniques.

While we intended to assess our patient's pain scores at regular intervals during their labor and at each request for top-up doses, we were not able to consistently obtain all of this information throughout the study period. Optimally, pain score data collection would have been complete so that a comparison of analgesia between the two groups could have been made. However, we could not reach any conclusions based on the data that we did collect since we were missing many data points.

Finally, it is possible that top-up dose requests may not be a valid surrogate marker for quality of analgesia. Future studies could employ patient controlled epidural analgesia in addition to physician requests for top-up doses in order to further assess differences between CSE and epidural analgesia. Top-up doses are used as a surrogate for breakthrough pain or adequacy of analgesia in almost all studies, especially those involving patient-controlled analgesia. It is also possible that the relatively short time period between analgesia and delivery in these parous patients may have contributed to the lack of difference between the groups. The use of nulliparous patients in future studies would lengthen the study time period.

Breakthrough pain is just one measure of analgesia quality. Another measure of quality is the incidence of failed analgesia or whether an epidural catheter needs to be replaced. It is possible that fewer epidural catheters placed with a CSE technique need replacement compared to an epidural technique. Our study was not designed to answer this question. There are many risks and benefits of both CSE and epidural labor analgesia and when choosing a technique all of these factors must be considered.

In summary, we did not find a difference between CSE and epidural analgesia in the number of top-up doses requested by parous patients in labor. We were able to confirm better analgesia for the first 30 minutes after CSE but also more hypotension and pruritus. Because there are both advantages and disadvantages to the CSE technique, its use should be individualized for each unique clinical situation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Department of Anesthesiology, Columbia University.

Footnotes

Disclaimers: none

Reprints will not be available from the author.

Conflict of Interest: None

Implications Statement: Parous women were randomized to receive combined spinal-epidural or epidural labor analgesia, maintained with a continuous epidural infusion of bupivacaine and fentanyl. There was no difference in the number of patient requests for top-up doses between groups.

References

- 1.Simmons S, Cyna A, Dennis A, Hughes D. Combined spinal-epidural versus epidural analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD003401. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003401.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsen LC, Thue B, Datta S, Segal S. Is combined spinal-epidural analgesia associated with more rapid cervical dilation in nulliparous patients when compared with conventional epidural analgesia? Anesthesiology. 1999;91:920–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199910000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comparative Obstetric Mobile Epidural Trial (COMET) Study Group UK. Effect of low-dose mobile versus traditional epidural techniques on mode of delivery: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:19–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05251-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norris MC, Fogel ST, Conway-Long C. Combined spinal-epidural versus epidural labor analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:913–20. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200110000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hess PE, Pratt SD, Lucas TP, Miller CG, Corbett T, Oriol N, Sarna MC. Predictors of breakthrough pain during labor epidural analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:414–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200108000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van de Velde M, Teunkens A, Hanssens M, Vandermeersch E, Verhaeghe J. Intrathecal sufentanil and fetal heart rate abnormalities: a double-blind, double placebo-controlled trial comparing two forms of combined spinal epidural analgesia with epidural analgesia in labor. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1153–9. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000101980.34587.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hepner DL, Gaiser RR, Cheek TG, Gutsche BB. Comparison of combined spinal-epidural and low dose epidural for labour analgesia. Can J Anaesth. 2000;47:232–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03018918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunn S, Connelly N, Steinberg R, Lewis TJ, Bazzel CM, Klatt JL, Parker RK. Intrathecal sufentanil versus epidural lidocaine with epinephrine and sufentanil for early labor analgesia. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:331–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199808000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bucklin B, Chestnut D, Hawkins J. Intrathecal opioids versus epidural local anesthetics for labor analgesia: A meta-analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:23–30. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2002.29111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong CA, Scavone BM, Peaceman AM, McCarthy RJ, Sullivan JT, Diaz NT, Yaghmour E, Marcus RL, Sherwani SS, Sproviero MT, Yilmaz M, Patel R, Robles C, Grouper S. The risk of cesarean delivery with neuraxial analgesia given early versus late in labor. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:655–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sia AT, Camann WR, Ocampo CE, Goy RW, Tan HM, Rajammal S. Neuraxial block for labour analgesia--is the combined spinal epidural (CSE) modality a good alternative to conventional epidural analgesia? Singapore Med J. 2003;44:464–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas JA, Pan PH, Harris LC, Owen MD, D'Angelo R. Dural puncture with a 27-gauge Whitacre needle as part of a combined spinal-epidural technique does not improve labor epidural catheter function. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1046–51. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200511000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan PH, Bogard TD, Owen MD. Incidence and characteristics of failures in obstetric neuraxial analgesia and anesthesia: a retrospective analysis of 19,259 deliveries. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2004;13:227–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swenson JD, Wisniewski M, McJames S, Ashburn MA, Pace NL. The effect of prior dural puncture on cisternal cerebrospinal fluid morphine concentrations in sheep after administration of lumbar epidural morphine. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:523–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199609000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernards CM, Kopacz DJ, Michel MZ. Effect of needle puncture on morphine and lidocaine flux through the spinal meninges of the monkey in vitro. Implications for combined spinal-epidural anesthesia Anesthesiology. 1994;80:853–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199404000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blumgart CH, Ryall D, Dennison B, Thompson-Hill LM. Mechanism of extension of spinal anaesthesia by extradural injection of local anaesthetic. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:457–60. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.5.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stienstra R, Dahan A, Alhadi BZ, van Kleef JW, Burm AGL. Mechanism of action of an epidural top-up in combined spinal epidural anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:382–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199608000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vartis A, Collier CB, Gatt SP. Potential intrathecal leakage of solutions injected into the epidural space following combined spinal epidural anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1998;26:256–61. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9802600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polley LS, Columb MO, Naughton NN, Wagner DS, Dorantes DM, van de Ven JM. Effect of intravenous versus epidural fentanyl on the minimum local analgesic concentration of epidural bupivacaine in labor. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:122–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200007000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stocks GM, Hallworth SP, Fernando R, England AJ, Columb MO, Lyons G. Minimum local analgesic dose of intrathecal bupivacaine in labor and the effect of intrathecal fentanyl. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:593–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.