Abstract

Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) is a widely used plasticizer found in a variety of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) medical products. The results of studies in experimental animals suggest that DEHP leached from flexible PVC tubing may cause health problems in some patient populations. While the cancerogenic and reproductive effects of DEHP are well recognized, little is known about the potential adverse impact of phthalates on the heart. This study examined the effects of clinically relevant concentrations of DEHP on neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. It was found that application of DEHP to a confluent, synchronously beating cardiac cell network, leads to a marked, concentration-dependent decrease in conduction velocity and asynchronous cell beating. The mechanism behind these changes was a loss of gap junctional connexin-43, documented using western blot analysis, dye-transfer assay and immunofluorescence. In addition to its effect on electrical coupling, DEHP treatment also affected the mechanical movement of myocyte layers. The latter was linked to the decreased stiffness of the underlying fibroblasts, as the amount of triton-insoluble vimentin was significantly decreased in DEHP-treated samples. The data indicate that DEHP, in clinically relevant concentrations, can impair the electrical and mechanical behavior of a cardiac cell network. Applicability of these findings to human patients remains to be established.

Keywords: Phthalate, Connexin, Gap Junction, Cardiomyocytes

INTRODUCTION

DEHP is used in a variety of medical products, as it allows stiff plastics, such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC), to become more flexible. DEHP may represent up to 40% of the finished weight of the plastic. It has been used in many medical devices such as intravenous bags and tubing for procedures like hemodialysis and cardiopulmonary bypass(Anonymous 2001). DEHP is highly hydrophobic and leaches from plastics following contact with blood, serum, or other albumin-containing fluids. A number of animal studies, conducted both in vitro and in vivo, have reported toxic effects of DEHP(Pugh, et al 2000, McKee 2000, Berman and Laskey 1993). The human toxicity of DEHP and other phthalates continues to be a subject of intense debate between public health advocates, researchers and the industry. Many argue that the benefits provided by DEHP-containing medical products greatly outweighs any possible adverse effects(Anonymous 2001, Cornu, et al 1992, Rais-Bahrami, et al 2004). After examining available experimental and clinical evidence, various regulatory agencies and expert panels have concluded that critically ill neonates and other groups of patients who are exposed to DEHP over prolonged periods of time, such as hemodialysis or recipients of repeated blood transfusions, may be especially susceptible to the potential adverse effects of phthalate esters(Kavlock, et al 2002). The majority of previous studies focused their attention on DEHP carcinogenicity and its adverse effects on reproductive health. Indeed, the risk of testicular toxicity and the ensuing negative impact on the fertility of DEHP-exposed newborns was found to be substantial enough to warrant the use of DEHP-free plastics for premature boys(Parks, et al 2000, Sharpe 2001). In contrast, little is known about the adverse effects of DEHP on the heart. Twenty years ago, it was suggested that DEHP and/or its metabolites might be arrhythmogenic(Rock, et al 1987, Barry, et al 1988, Barry, et al 1989). However, since then, neither the extent of DEHP cardiac toxicity nor its putative mechanisms were further explored. The goal of this study was to examine the effects of DEHP exposure on cardiac myocyte network. We found that treatment of neonatal cardiomyocytes with 1–50μg/ml DEHP for 72–96h functionally uncouples the cardiomyocyte syncytium, resulting in asynchronous cell network contractions. The observed physiological uncoupling in DEHP samples correlated with a diminished amount of connexin-43 protein and abrogated gap-junctional communication, as measured using a dye transfer assay. The marked uncoupling effect of DEHP, along with other observed effects of this compound on cardiac network behavior, calls for further studies aimed at assessing this clinically relevant issue.

METHODS

All experiments involving animals were performed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the George Washington University Medical Center, which follows federal and state guidelines. The mention of commercial products, their sources, or their use in connection with material reported herein is not to be construed as either an actual or implied endorsement of such products by the Department of Health and Human Services.

Chemicals

Collagenase II was obtained from Worthington (Freehold, NJ). Media and porcine trypsin were obtained from Gibco BRL (Grand Island, NY). Fluo-4, 7AAD nuclear stain and Alexa Fluor 488 (donkey anti-rabbit IgG or goat anti-mouse IgG) were purchased from Molecular Probes Inc. (Eugene, OR). N-cadherin antibody, anti-mouse IgG-HRP AP conjugate and anti-rabbit IgG-HRP AP conjugate were purchase from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Prolyl 4-Hydroxylase was purchase from Millipore (Telmecula, CA). Paxillin was purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (Franklin Lakes, NJ). IF1 and CT1 antibodies were purchased from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Seattle, WA). IF1 antibody predominately binds to residues 374–379, labeling connexin-43 found in gap junctional plaques. CT1 antibody primarily recognizes the non-phosphorylated forms of Serine 364 and Serine 365. Since phosphorylation of the latter is required for trafficking of the protein to the membrane, CT1 serves as a marker for perinuclear and/or Golgi localized connexin-43. Cy3-conjugated AffiniPur fab fragment (donkey anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse) and Cy5-conjugated AffiniPur fab fragment (goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse) were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). Connexin-43, α-actinin, vimentin, and vinculin antibodies, LDH-assessment kit and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO) unless specified otherwise.

Cardiomyocytes culture

Cardiomyocytes from 1- and 2-day old Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained by a modified enzymatic digestion procedure(Arutunyan, et al 2001). Hearts were removed and rinsed in a cold, calcium and magnesium free, Hank’s Buffered Salt Solution (CMF-HBSS), and then minced into ~ 1mm3 pieces. Tissue pieces were incubated overnight at 4°C in fresh CMF-HBSS containing 0.1mg/mL trypsin. The next day, heart tissue was washed several times with fresh CMF-HBSS, collected in Leibovitz’s medium containing 0.8mg/mL collagenase II and shaken for 30min at 37°C. The cells were then gently triturated, passed through a cell strainer to remove any undigested pieces, and centrifuged for 5min at 17.5g. The pellet was resuspended in Dulbecco modified essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and pre-plated for an hour to minimize the presence of fibroblasts, which attach more rapidly than myocytes. Unattached cells were then collected, counted and plated in a culture dish containing 25mm laminin-coated glass coverslips (105 cells/cm2). Myocytes were then kept under standard culture conditions in DMEM, supplemented with 5% FBS, 10U/ml penicillin, and 1μg/ml streptomycin.

Experimental Protocol

On the third day after plating, the cells formed an interconnected confluent network that exhibited rhythmic spontaneous contractions. Concentrated 50mg/mL DEHP stock in DMSO was added directly to the cell media to achieve the final concentrations of DEHP specified in figures. The final concentration of DMSO in DEHP-treated samples and the corresponding controls did not exceed 0.1%. Cardiomyocytes were visualized daily to monitor the appearance and beating behavior of the myocyte network. The assessment of the LDH release was done according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Unless specified otherwise, the term “DEHP-treated” refers to 72–96h exposure to DEHP.

Monitoring calcium transients

Cells were loaded for 1-hour at room temperature with 5μM Fluo-4AM (Kd 345nM), a fluorescent calcium indicator. Calcium transients were monitored with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal imaging system using 488nm excitation/505–530nm emission settings. Measurements were conducted in spontaneously beating cell cultures, with the exception of pacing studies aimed at evaluating conduction velocity. In the latter series, the myocyte network was paced using a pair of platinum electrodes (1mm apart) to which monophasic 1.2ms pacing pulses were applied and the measurements were conducted using x-t linescan mode. Samples were also monitored using a fluorescence imaging system comprised of an Andor IXON DV860 CCD camera fitted with either low or high magnification Nikon lenses. With the low magnification lens, the system was used to image an entire 25mm coverslip with a spatial/temporal resolution of ~150μm/100fps. With the high magnification lens, the field of view was ~3×3mm and the spatial resolution was 25μm. Samples were illuminated using light from LEDs (LumiLEDs) that was band-pass filtered at a peak wavelength of 500nm and a spectral half-width of 20nm. Fluo-4 fluorescence was band-pass filtered at a peak wavelength of 540nm and a spectral half-width of 40nm.

Immunocytochemistry

Samples were fixed using a standard 4% paraformaldehyde protocol, followed by staining with connexin-43 (1:500), N-cadherin (1:50), vimentin (1:50), α-actinin (1:800), prolyl 4-hydroxylase (1:500), paxillin (1:100), vinculin (1:800), IF1 (1:250), CT1 (1:250), or 7AAD (1:200). Samples were incubated with either Alexa Fluor 488 (donkey anti-rabbit IgG or goat anti-mouse IgG), Cy3-conjugated AffiniPur fab fragment (donkey anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse), or Cy5-conjugated AffiniPur fab fragment (goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse). Images were acquired and analyzed with the Zeiss LSM 510 confocal imaging system using dye-specific filter settings. The LSM imaging software includes a colocalization function which was used to calculate the number of values representing the proportion of colocalized pixels in dual-color images.

Real Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from embryoid bodies using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA), per the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples were treated with DNase (Promega, Madison WI), and samples were reverse transcribed using Affinityscript QPCR cDNA synthesis kit (Stratagene, Cedar Creek TX). An ABI Prism 7300 light cycler was used to perform real time PCR using SYBR green Q-PCR mastermix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA). All runs were accompanied by expression for either 18S or b-actin control genes. Samples were normalized using a 2-delta delta CT based algorithm to represent a ratio between experimental and control genes. Primer sequences: Connexin43 GAACACGGCAAGGTGAAGAT (forward) and GACGTGAGAGGAAGCAGTCC (reverse); 18S TAGAGGGACAAGTGGCGTTC (forward) and CGCTGAGCCAGTCAGTGTAG (reverse); b-actin TGTTACCAACTGGGACGACA (forward) and GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAA (reverse).

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested in homogenization buffer containing 250mM sucrose, 20mM Hepes, 1% Sodium dodecyl sulfate, 2mM Dithiothreitol, 2mM Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 2mM Ethylene-bis(oxyethylenenitrilo)tetraacetic acid, 10mM b-Glycerophosphate, 1mM Orthovanadate, 2mM Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20ug/mL Leupeptin, 10ug/mL Aprotinin, and 5ug/mL Pepstatin. Cells were incubated on ice in homogenization buffer for 15min. Samples were sonicated three times for 15s intervals on ice (Sonic Dismembrator, Fisher Scientific), centrifuged to clarify, and equal amounts of protein were loaded onto precise 4–20% gradient gels (Pierce). To obtain Triton insoluble protein samples, cells were incubated on ice in homogenization buffer (1% Triton-X100 substituted for 1% Sodium dodecyl sulfate) for 1 hour with occasional vortexing. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000G for 5 min at 4°C. The soluble supernatant was removed and stored. The remaining Triton-insoluble pellet was dissolved in homogenization buffer containing 1% Sodium dodecyl sulfate. Triton-insoluble samples were then incubated on ice for 15min, sonicated three times for 15s intervals, centrifuged to clarify, and equal amounts of protein were loaded onto precast gels. Blots were probed with connexin-43 (1:3000), N-cadherin (1:100), vimentin (1:400), α-actinin (1:800), prolyl 4-hydroxylase (1:800), paxillin (1:600), or vinculin (1:400). Blots were incubated with either goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP AP conjugate or goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP AP conjugate (1:3000). Relative protein expression was assessed using a STORM 860 PhosphorImager.

Scrape method with Lucifer yellow dye

Following DEHP treatment, cells were rinsed with Tyrode solution and a razor blade was used to create longitudinal scratches through the cell monolayer. Cells were incubated in the dark for 3min in the presence of 0.05% Lucifer Yellow. Cells were rinsed three times with Tyrode and fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde before examining by confocal microscopy. Lucifer Yellow does not diffuse through intact plasma membranes, but its molecular weight permits its transmission across patent gap junctions(Zhang, et al 2006). The profile of the fluorescence intensity perpendicular to the scratch was used to extract the distance values corresponding to the half-peak of signal increase using Scion Image software.

RESULTS

Acute effects of DEHP treatment

Addition of 50μg/ml DEHP to a spontaneously beating cardiac cell network did not cause significant acute changes in either the global network behavior, amplitude, half-time to peak or half-time to decay of the calcium transients or monolayer conduction velocity (Fig.1). Occasional rhythm disturbances seen upon addition of either DEHP or equal amount of media with 0.1% DMSO reflected the acute reaction of cardiomyocyte network to the media change, but they were not sustainable or significantly different between DEHP-treated and control samples.

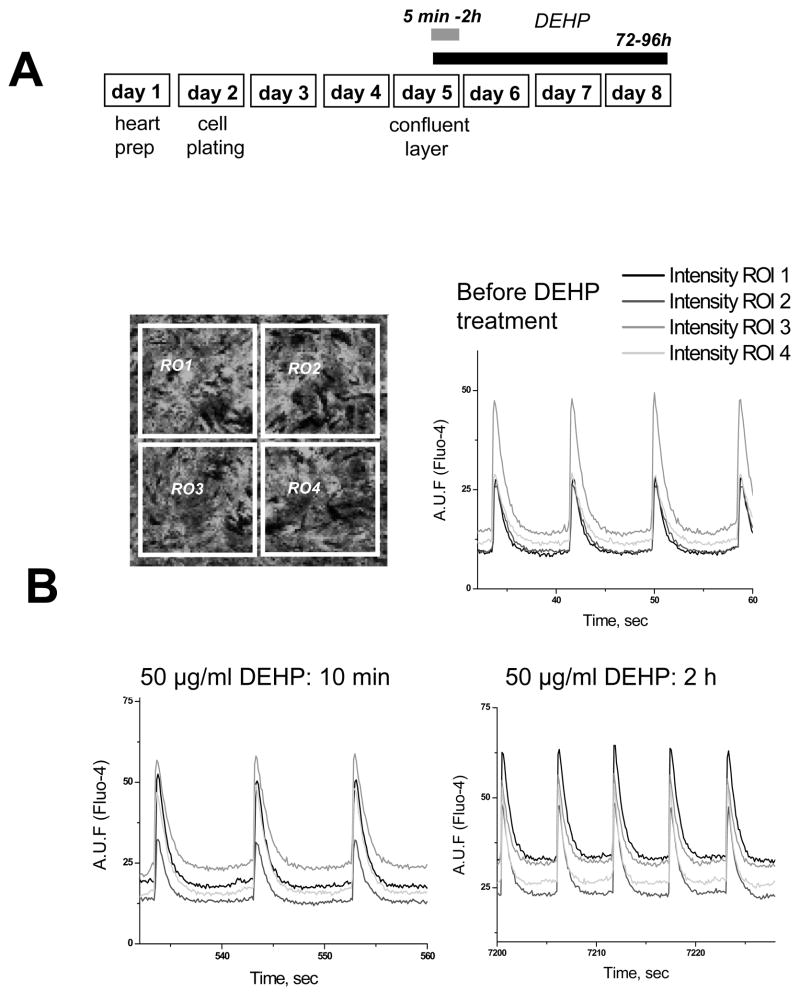

Fig. 1. Experimental protocol and acute DEHP treatment.

A. Cartoon of the experimental protocol. Hearts were excised, minced and incubated overnight in ice-cold trypsin-collagenase solution. Synchronously beating monolayers of rat cardiac myocytes were formed three-four days after cell plating. The cells were then treated with 50 μg/ml DEHP, followed by assessment of their functional behavior and/or protein presence either immediately or on day 3–4 following treatment.

B. Confocal image of confluent cardiac myocyte network on day 3 after plating as it seen upon cell loading with Fluo-4AM (top left). Traces acquired from four regions of interests show spontaneously beating cell network with highly synchronized calcium transients (top right). Representative traces after addition of 50μg/ml DEHP are shown below. No significant differences between the control and DEHP-treated samples were observed. Note high degree of synchronicity in all the traces.

Effects of prolong DEHP exposure on calcium transients and impulse conduction

Our main goal was to examine the effects of DEHP concentration and duration comparable with plasticizer presence in the plasma of neonates after ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) treatment and other clinical procedures listed in Table 1. The table lists reported DEHP values (Barry, et al 1989, Shintani 1985, Shneider, et al 1989, Sjoberg, et al 1985, Karle, et al 1997, Loff, et al 2000). Total DEHP exposure is likely to be even higher, as critically ill neonates often receive multiple blood transfusions, repetitive infusions of drugs and vitamins, and enteral feeding(Food and Drug Administration: Center for Devices and Radiological Health 2002).

Table 1.

Maximum reported DEHP exposure following medical procedure in neonates. Values reported in (Loff, 2000) were obtained from a simulation study that mimicked clinical exposure in neonatal intensive care unit.

| Medical Procedure(Neonate) | DEHP (μg/ml) | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange Transfusion | 84.9 | Sjoberg, 1985 |

| 123.1 | Plonait, 2003 | |

| 26.7 | Shintani, 1985 | |

| ECMO | 34.9 | Karle, 1999 |

| 33.5 | Shneider, 1989 | |

| Congenital Heart Repair | 4.7 | Barry, 1989 |

| Midazolam | 1.13 | Loff, 2000 |

| Fentanyl | 4.59 | Loff, 2000 |

| Propofol | 656 | Loff, 2000 |

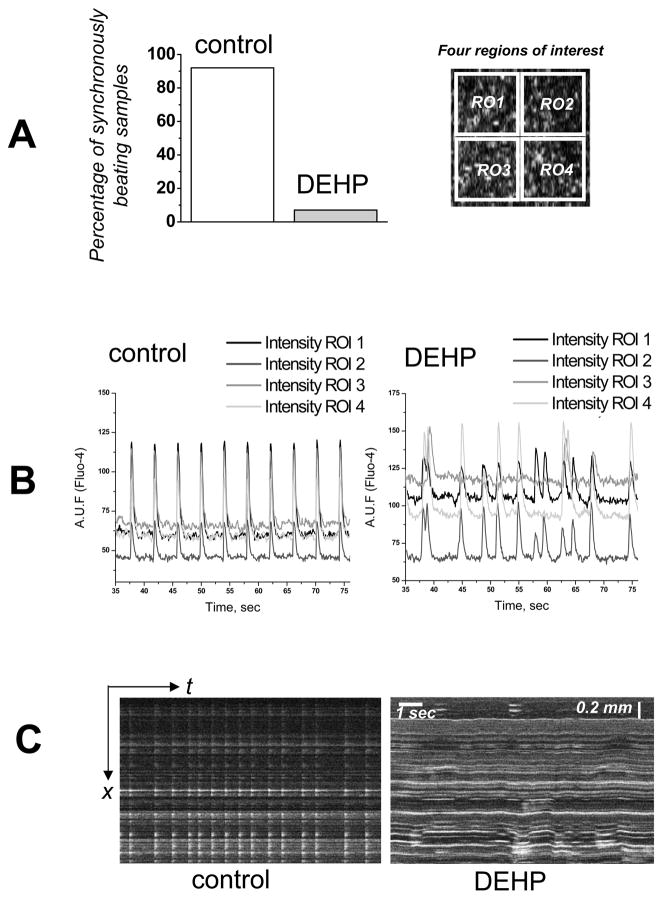

A single dose of DEHP was added to confluent, synchronously beating cardiomyocyte layers which were kept for 72–96h under standard cell culture without subsequent media change. Cells were then loaded with Fluo-4 and assessed for their functional behavior. A control set of coverslips from the same cell preparation was treated with 0.1% DMSO, the same concentration of DMSO present in the DEHP treated cultures. DEHP-treated samples exhibited marked functional uncoupling as illustrated in Figs.2–4 by several experimental means. Fig.2A shows the percentage of samples that exhibited asynchronous beating. The latter was documented by simultaneous recordings of calcium transients from four regions of interests as depicted on Fig.2A, right. The representative traces from the control and 50 μg/ml DEHP-treated samples are shown in Fig.2B. Fig.2C compares the appearance of the control and 50 μg/ml DEHP-treated layers when events were recorded in a line scan mode. In control, well-coupled samples, propagation of the calcium transients is fast, thus a wave of contraction appears as a single flash of Fluo-4 signal. In contrast, the line scan images of DEHP-treated layers are markedly different, exhibiting asynchronous calcium transients and noticeable motion artifacts.

Fig. 2. Cardiomyocyte monolayer behavior after 72–96h treatment with DEHP.

Confluent, spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes treated with 50μg/ml for 72–96h in culture.

A. Relative percentage of coverslips in which synchronized uniform contractions were observed (n=14). Network synchronization was assessed by observing calcium transient traces that corresponded to four different regions of interest as shown on the right.

B. Recordings of calcium transients are shown as relative units of Fluo-4 fluorescence. DEHP samples are asynchronous (n=8).

C. Linescan images show network desynchronization, as well as lateral motion of the monolayer in the DEHP-treated sample.

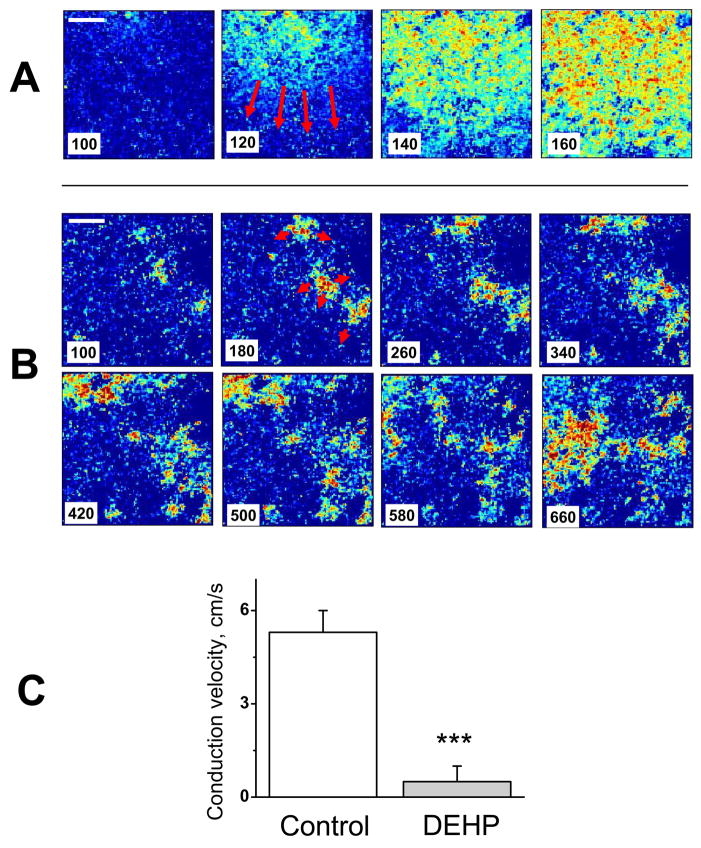

Fig. 4. Marked decrease in conduction velocity after 3-day treatment with DEHP.

Individual frames from CCD-based acquisition system show fast, homogenous wavefronts in control (A) versus slow, fractionated propagation in samples treated with 50μg/ml DEHP for three days (B). Note that the sequential frames in the upper and lower rows are 20ms apart, versus 80 ms for the DEHP-treated sample. A time stamp was placed on the left lower corner of the image. A ten-fold decrease in apparent conduction velocity was observed in the DEHP-treated samples (C). The movies of the control and DEHP samples can be seen as an online supplement (1&2).

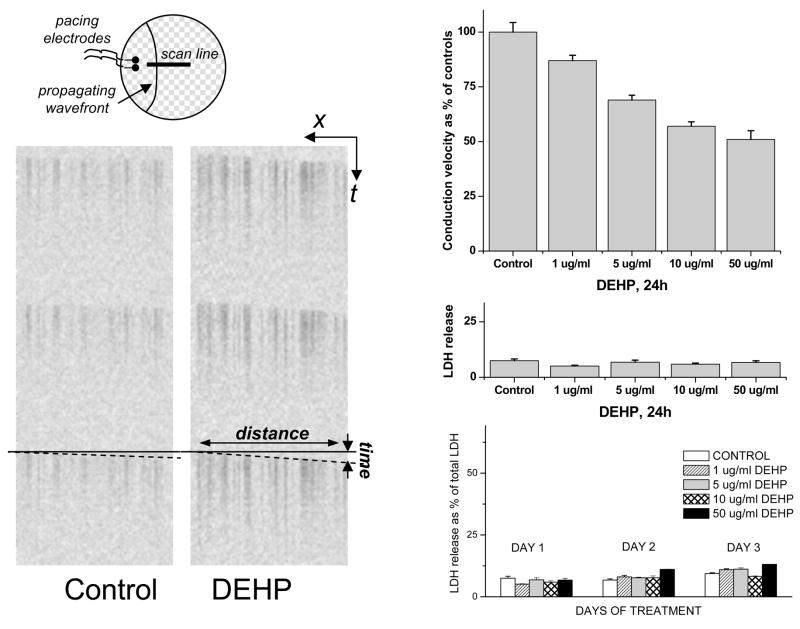

Asynchronicity and low conduction velocity are both a result of diminished cell-to-cell coupling. In a well-coupled cell network, propagation from a source (either pacing electrode or spontaneously automatic network loci) rapidly spreads thru the entire coverslip. As a result, traces from different regions of the coverslip appear synchronous. However, when a cardiac network is severely uncoupled, wavefronts “meander” along pathways determined by local heterogeneities, whereby the exact pattern of such meandering changes with time. As a result, traces appear “asynchronous”. DEHP-induced decrease in conduction velocity is concentration-dependent and it preceded the loss of “synchronicity” at all tested concentrations. In fact, DEHP significantly impacted conduction velocity as early as 24h after DEHP treatment and in concentrations as low as 1μg/ml (Fig.3). Notably, a parallel measurement of LDH release confirmed that the viability of control and DEHP-treated samples was comparable (Fig.3, bottom right graph).

Fig. 3. Concentration-dependency of DEHP effect on conduction velocity and LDH release.

The top left cartoon shows the experimental setup for measuring conduction velocity. Representative linescan images of the control and 50μg/ml DEHP samples are shown below. The upper right graph shows concentration-dependent decrease in conduction velocity following 24h DEHP treatment. The corresponding values of LDH release can be found immediately below. With continuous exposure to DEHP, the conduction velocity continued to decrease, but the LDH release stayed comparable to the control samples (bottom right graph). A marked decrease in conduction velocity seen after 3 day of treatment with 50μg/ml DEHP is shown in the next figure.

When the cell monolayer becomes severely uncoupled, it is difficult to measure conduction velocity using the line-scan method shown in Fig. 3, due to wavefront meandering. Therefore, the propagating wavefronts in both control and DEHP samples were recorded with a fast CCD-camera system (Fig.4). After a 3-day treatment with 50 μg/ml DEHP, a decrease in average conduction velocity was as much as 10-fold in many preparations, leading to fractionated wavefronts and frequent microreentries (supplemental online video 1 & 2).

Effects of DEHP treatment on monolayer motion

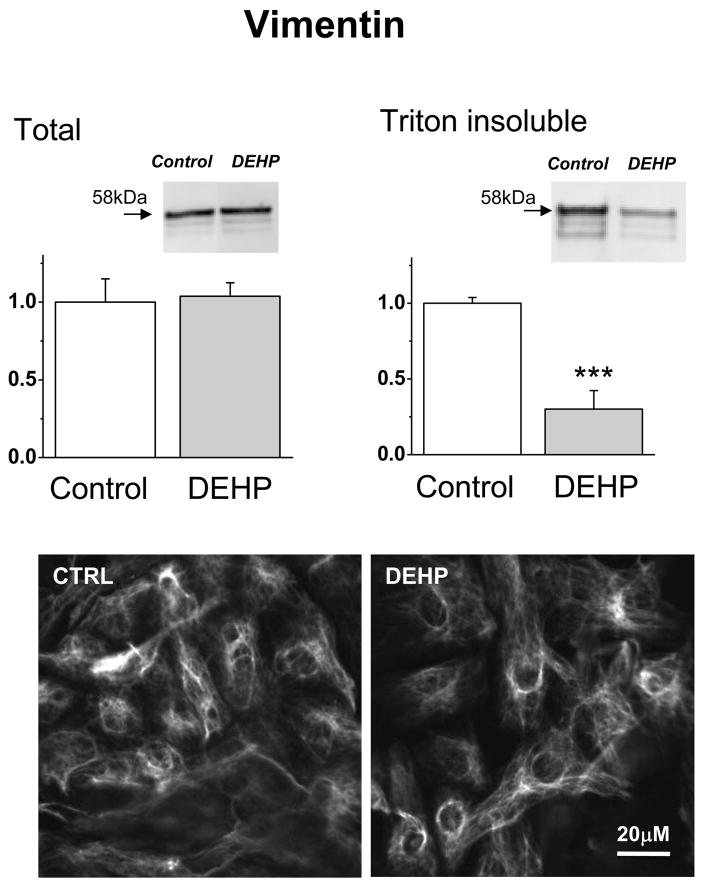

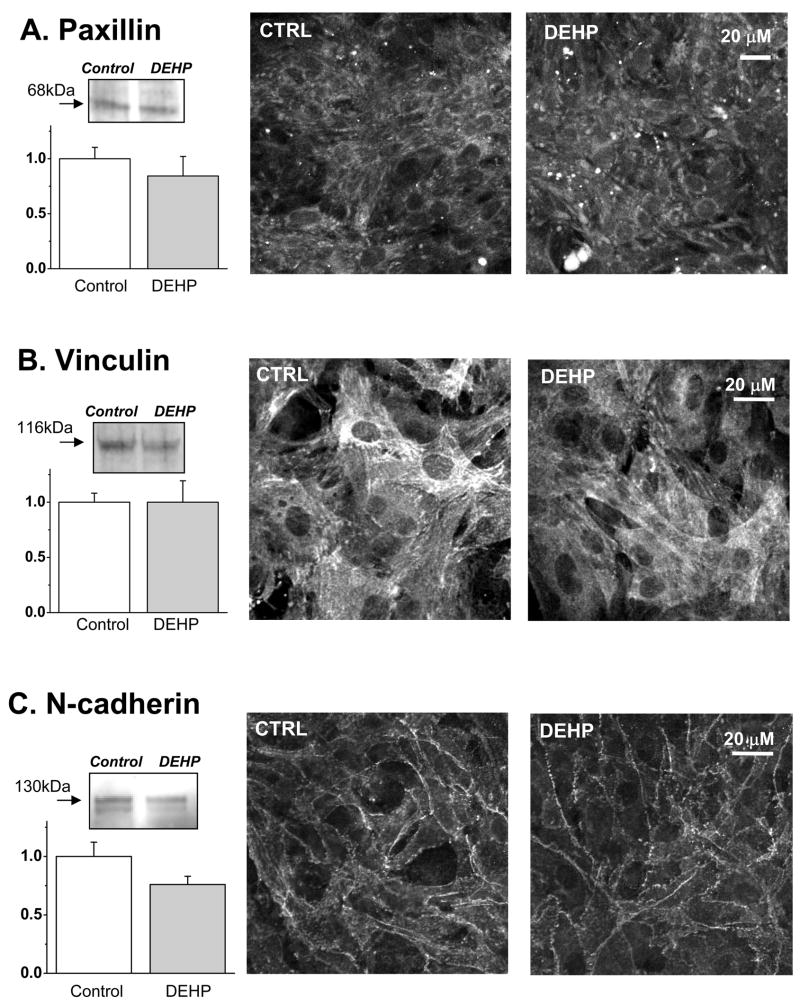

Observation of DEHP-treated samples using phase-contrast mode often revealed an unusual, “waterbed”-like pattern of motion. It become more pronounced as the duration of DEHP-treatment increased (supplemental online video 3 & 4). This effect is not an artifact of diminished electrical coupling since pharmacological inhibition of gap junctions using alternative means did not produce the “waterbed” effect in our previous studies which employed heptanol, low pH and palmitoleic acid(Arutunyan, et al 2001, Arutunyan, et al 2002)(Pumir, et al 2005). The myocyte motion was suggestive of changes in the mechanical properties of the underlying layer of fibroblasts. The latter was confirmed by assessing the amount of Triton-insoluble vimentin in DEHP-treated samples which revealed a significant decrease in Triton-X100 insoluble protein (Fig.5, p=0.0008). The insoluble vimentin constitutes an essential part of fibroblast intermediate filaments. As such, it has a major impact on the cell stiffness(Wang and Stamenovic 2002). Another possibility for the motion effect can be attributed to diminished myocyte adhesion. However, the amounts of two major focal adhesion proteins, paxillin and vinculin, were not significantly decreased in DEHP-treated samples neither did we observe any major changes in the intracellular distribution of these proteins (Fig. 6A. B). The amount of N-cadherin, a protein that mediates intercardiomyocyte adhesion via the intercalated discs and serves as an anchor for myofibrils at cell-cell contacts, was slightly lower in DEHP-treated samples but the difference was found not to be significant (Fig.6C, p=0.055).

Fig. 5. Vimentin presence in total and Triton-X100 insoluble fraction.

The amount of total vimentin (left) was unchanged by 50μg/ml DEHP, while the quantity of vimentin in TritonX-100 insoluble fraction was significantly decreased (right) compared to the controls (n = 4; p < 0.0008; DEHP samples normalized to the control values). Bottom: representative confocal images showing vimentin staining.

Fig. 6. Key adhesion proteins in control and DEHP-treated samples.

The total amount of paxillin (A), vinculin (B) and N-cadherin (C) was found to be not significantly different between control and 50μg/ml DEHP-treated samples. The left panels show the results of Western blots with the representative bands and their average intensity values (DEHP normalized to control values, n = 8 for paxillin, n=4 for vinculin and n=8 for N-cadherin). Right panels show the representative confocal images for each protein.

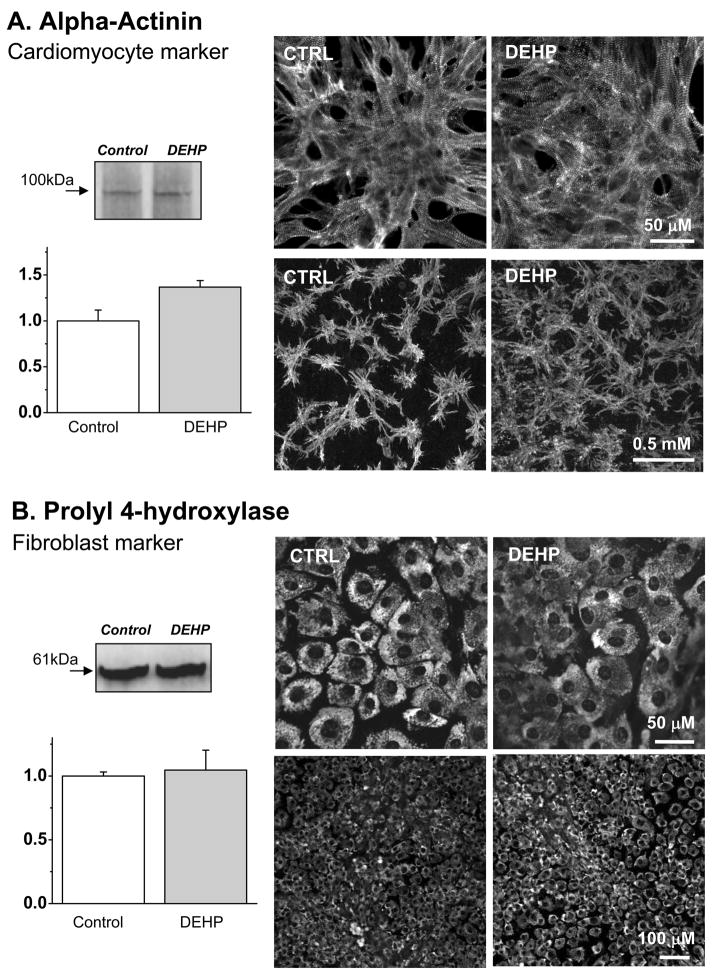

Myocyte/fibroblast ratio

One might suggest that the observed electrical uncoupling as well as the unusual pattern of monolayer motion can be explained by the increased numbers of fibroblasts in DEHP-treated samples. The amount of fibroblasts is significantly reduced by a pre-plating procedure, but these cells are always present in primary culture of neonatal cardiomyocytes. In contrast to cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts retain their capacity to proliferate. We added DEHP to functionally matured, synchronously beating cardiomyocyte layers formed on day 3–4 after cell plating. DEHP treatment therefore added another 3–4 days in culture, thus the total age of the cultures was 7–8 days. If DEHP was selectively toxic to myocytes and/or induced proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts, one would expect to see replacement of myocytes by the cardiac fibroblasts in long-term cultures. If this occurred, the myocyte network might appear to be “less coupled”(Gaudesius, et al 2003, Manabe, et al 2002, Camelliti, et al 2006). However, muscle-specific staining for α-actinin did not reveal a smaller amount of myocytes or any “fibroblast”-filled gaps in cardiomyocyte networks (Fig.7A). The amount of actinin-positive staining was in fact slightly higher in DEHP-treated samples and cardiomyocyte distribution appeared more homogenous (Fig.7A). The appearance of fibroblasts and the total amount of the fibroblast marker prolyl 4-hydroxylase were identical between the control and DEHP-treated samples (Fig.7B). All-in-all, the observed changes in myocyte-to-fibroblast ratio were not in the direction which could help to explain the uncoupling effect of DEHP.

Fig. 7. The amount and relative distribution of cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts in primary cultured treated with DEHP.

Alpha-actinin was used to identify cardiomyocytes while the β-subunit of prolyl 4-hydroxylase was used as a marker for cardiac fibroblasts. The left panels show the results of western blots with the representative bands and their average intensity values normalized to respective controls. The right panels show the representative confocal images for each marker.

A. 50μg/ml DEHP-treated samples had evenly spaced α-actinin staining, while control sample cells tended to bundle into clusters. The latter is consistent with the changes occurring in long-term cultures of neonatal cardiomyocytes (note: samples were analyzed on day 8 after cell plating). The amount of total protein in Western blots (n=6) was slightly increased in DEHP-treated samples (p=0.015).

B. Western blot assays and the distribution of fibroblast marker prolyl 4-hydroxylase, in control and 50μg/ml DEHP-treated samples. No difference between control and DEHP-treated samples was observed (n=8).

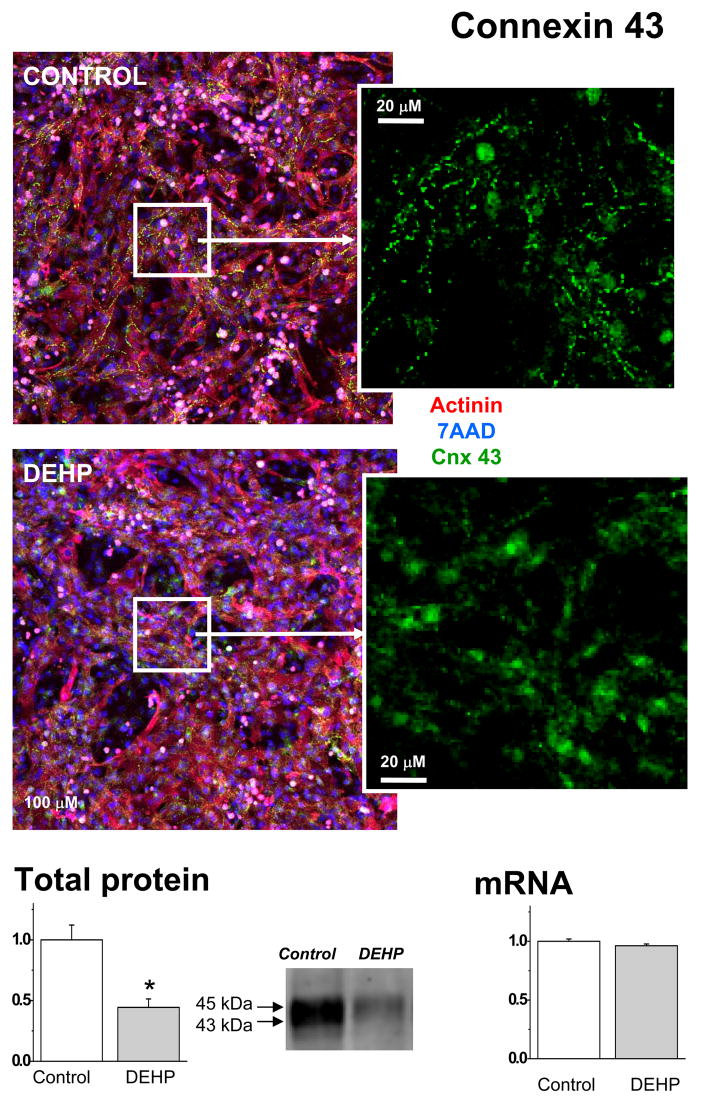

The amount and distribution of connexin-43

Another possible explanation of DEHP effect was a change in connexin-43 expression or localization. The latter phenomenon was reported in other cell types treated with DEHP (Kang, et al 2002, Isenberg, et al 2000, Kamendulis, et al 2002). Connexin-43 is the main connexin isoform that constitutes the gap junctions between cardiac myocytes. The amount of connexin determines the conduction velocity(Thomas, et al 1998). Confocal images indicated that a much smaller amount of punctuated connexin-43 staining was present in DEHP-treated samples (Fig.8). Western blot-based assessment confirmed that the total protein level of connexin-43 was significantly lower in DEHP-treated samples as compared to the controls (p=0.001). There was not a significant difference in the mRNA expression of connexin-43, as determined by real time-PCR.

Fig. 8. Visualization and quantification of connexin-43 in control and DEHP-treated samples.

Composite images shows appearance of control and 50μg/ml DEHP-treated samples after triple staining for α-actinin which identifies myocytes (red), nuclear stain 7-AAD to identify all cells (blue) and connexin-43 (green). Staining for connexin-43 (see also an enlarged area on the right) was less intense and less punctuated in DEHP-treated samples. Western blot assessment confirmed a significant decrease in connexin protein bands (n=8, p<0.005). There was not a significant difference in the mRNA expression of connexin-43, as determined by real time-PCR (n=5).

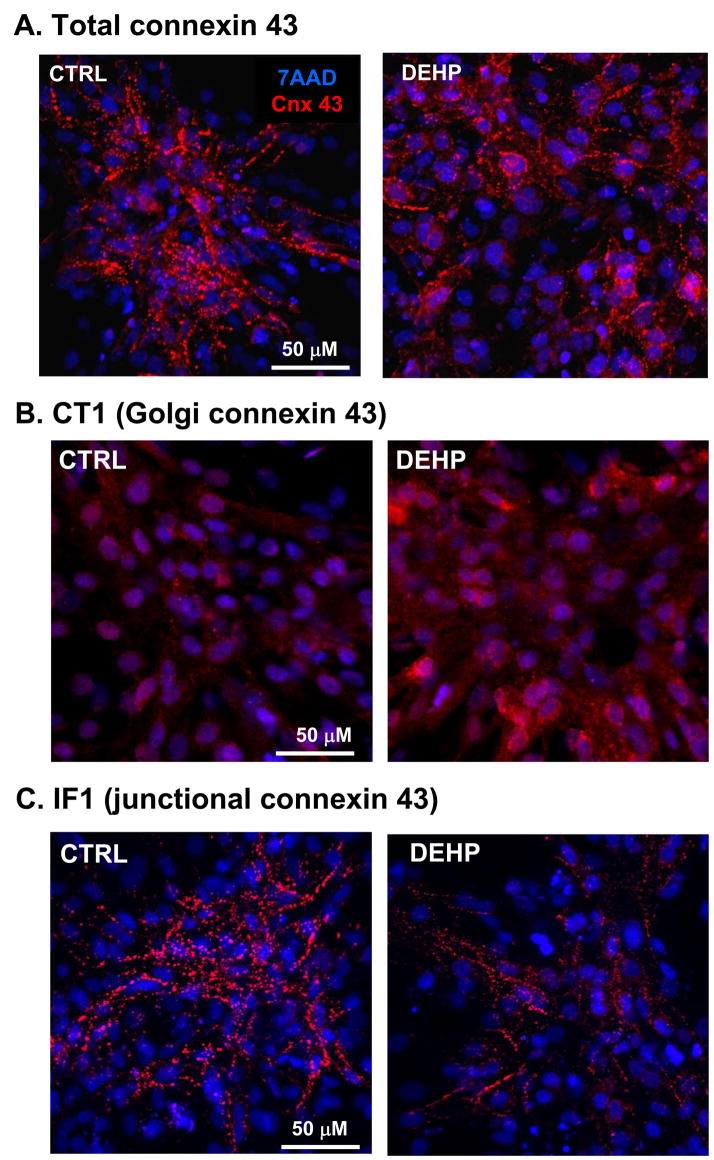

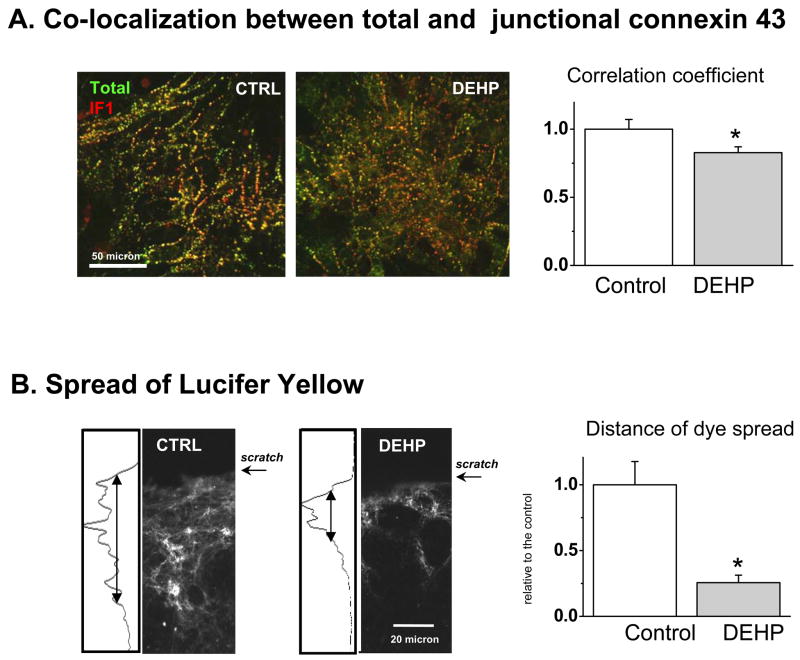

Use of recently developed organelle-specific connexin-43 antibodies(Sosinsky, et al 2007) allowed us to further examine the distribution of connexin-43 in DEHP-treated and control samples (Fig.9). DEHP-treated samples stain more abundantly with the CT1 antibody (Fig. 9B). The CT1 antibody recognizes non-phosphorylated serine-364 and serine-365 residues on the c-terminus of the connexin-43 protein. Phosphorylation of these residues results in trafficking of the connexin protein to the membrane, thus CT1 serves as a marker for perinuclear and/or golgi specific connexin-43 since it detects the non-phosphorylated form. In comparison, IF1 is a structure-specific antibody that binds to residues 375–379 when the connexin protein is localized to gap junctions. Markedly less IF1-specific connexin-43 immunostaning was observed in DEHP-treated samples (Fig. 9C). Spatial correlation analysis confirmed that total connexin-43 staining and gap junction-specific IF1 signal exhibit a lower degree of colocalization in DEHP-treated samples (Fig.10A). All together data shown in Figs.8–10A strongly suggest that DEHP impacts connexin-43 trafficking and assembly into functional gap junctions.

Fig. 9. Use of site-specific connexin-43 antibodies to identify subcellular distribution of connexin-43.

Confocal images of control and 50μg/ml DEHP-treated samples co-stained with nuclear stain and (A) general connexin-43 antibodies, (B) IF1 antibody that identifies connexin-43 in gap junctional plaques, (C) CT1 antibody, a marker for perinuclear and/or Golgi localized connexin-43 (n=5, representative images are shown).

Fig. 10. Loss of functional coupling upon DEHP treatment.

A. Loss of optical overlap between total and gap-junction specific connexin-43 in 50μg/ml DEHP-treated samples. A spatial correlation coefficient between total and gap-junction specific connexin-43 staining was statistically smaller in DEHP-treated samples as compared to the controls (n=6, p<0.05, representative dual color images are shown). Pixels in which signals for the two antibodies overlap appear yellow.

B. Assessment of intercellular communication using gap-junction permeable dye. Top: representative images of control and 50μg/ml DEHP-treated samples scrape-loaded with Lucifer yellow (n=3). The profile of the Lucifer yellow fluorescence intensity was compared between the control and DEHP-treated samples. The half-width of dye-associated increase was used to calculate the difference in diffusion distance. The latter was significantly less in DEHP-treated samples (n=6, p< 0.05).

Effects of DEHP treatment on cell-to-cell transfer of Lucifer Yellow

Gap junction-mediated intercellular communication can be assessed in both excitable and non-excitable cells by visualizing cell-to-cell diffusion of Lucifer Yellow, a gap junction permeable dye. A scrape-loading method can be used to introduce the dye into cultured cells by inducing a transient tear in the cell layer in the presence of dye(Zhang, et al 2006). The total area and distance of diffused Lucifer dye was significantly decreased in DEHP–treated samples compared to the controls (Fig.10B, p=0.017). These findings were consistent with cell-cell uncoupling (Fig.2), decrease in conduction velocity (Fig.3–4) and loss of membranous connexin-43 illustrated in Figs.8–10A.

Treatment with PPAR agonist

Previous studies have suggested that DEHP effects on intercellular communication are mediated via peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor alpha (PPARα) pathway(Ryu, et al 2007, Peraza, et al 2006). We tested the ability of the PPARα agonist Wy-14,643 to mimic the effects of DEHP on cardiac cells. Since it was reported that low and intermediate concentrations of Wy-14,643 might have opposite effects to the high concentrations of the agonist(Cruciani and Mikalsen 2002b), we tested two concentrations. Neither 10μM nor 100μM Wy-14,643 caused significant cardiomyocyte uncoupling or impacted monolayer motion. While these experiments do not fully exclude the involvement of PPARα in the observed effects of DEHP on cardiac cell layers, they point to a difference between the mechanisms of DEHP-induced gap-junctional inhibition in different cell types(Cruciani and Mikalsen 2002b, Bhattacharya, et al 2005).

DISCUSSION

There is a paucity of data on the direct effects of DEHP and its metabolites on cardiac tissue. Almost four decades ago it was noted that when beating chick embryonic cardiomyocytes(Rubin and Jaeger 1973) were exposed to 4 μg/ml DEHP for 30 minutes it caused complete cessation of cell beating. Loss of cell viability occurred after 24h. Another early study tested the acute effects of 100μg/ml DEHP on isolated, perfused rat hearts and found decreased spontaneous heart rate, coronary flow and isometric systolic tension(Aronson, et al 1978). In contrast to the above-mentioned early findings, we did not observe immediate or acute effects of DEHP on cell beating frequency. More sensitive indices of intracellular calcium dynamics, i.e. the duration and the magnitude of calcium transient(Clusin 2003, Fabiato and Fabiato 1973, Ishide, et al 1992) also did not change upon acute (i.e., min to hours) DEHP exposure. A decrease in myocyte viability, either by visual observation of α-actinin stained samples or LDH release assessment, was not observed at all tested timepoints (Figs.3&7A). Possible reasons for the noted differences between our data and earlier observations are the age of the cells (neonatal versus embryonic) and species difference (rat versus chick). Several earlier studies also pointed to the potential cardiotoxic effects of mono(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (MEHP), the major metabolite of DEHP(Barry, et al 1988, Barry, et al 1989, Barry, et al 1990). These studies showed that MEHP has a reversible, concentration-dependent negative inotropic effect on human atrial trabeculae. However, the effects have been observed at high concentrations of MEHP (IC50 of 85 μg/ml), which are unlikely to be seen in plasma, even after prolonged exposure of the blood to DEHP products.

While we did not see the acute effects of DEHP in our experimental model, we have shown, for the first time, that the clinical relevant dose and duration of DEHP exposure can have a significant impact on the behavior of the cardiac cell network. The major finding was a marked uncoupling effect of DEHP, which can be explained by a significantly lesser amount of gap junctional connexin in DEHP-treated samples. DEHP has been shown to decrease gap junctional communication in many cells, including hepatocytes(Isenberg, et al 2000, Krutovskikh, et al 1995), and the latter phenomenon was linked to DEHP tumorogenicity. One of the main arguments to dismiss DEHP tumorogenicity in humans is experimental evidence that the observed effect may be rodent-specific since it is believed to be mediated via PPARα(Kamendulis, et al 2002). The human liver contains considerably lower levels of PPARα, and this difference is thought to account for the species differences in effects of peroxisome proliferators(Gonzalez 2002). Notably, the PPARα agonist Wy-14,643 was shown to inhibit gap junctional communication in hepatocytes, fibroblasts and Sertoli cells(Cruciani and Mikalsen 2002b, Bhattacharya, et al 2005), but it failed to desynchronize cardiomyocyte layers in our experiments. This difference can be due to a low levels of expression of both PPARα and PPARβ in cardiomyocytes(Braissant, et al 1996, Gilde, et al 2003)and/or presence of alternative, peroxisome receptor-independent pathways via which DEHP toxicity is mediated(Larsen and Nielsen 2007). Indeed, accumulating evidence suggests that phthalate effects are not solely mediated through PPARα. For example, PPARα null mice exhibit signs of reproductive toxicity following phthalate exposure(Peters, et al 1997), and Wy-14643 treatment produced an earlier and exaggerated tumor response in comparison to DEHP, despite equivalent stimulation of peroxisome proliferation(Marsman, et al 1988). Overall, further studies are necessary to link or contrast the decrease in gap junction communication induced by DEHP in heart cells versus other cell types.

Several compounds have been shown to reduce the amount of cardiac connexin-43 by interfering with its expression. In the case of DEHP, both the amount of protein and trafficking of connexin appear to be affected. In DEHP-treated cells connexin-43 exhibits a perinuclear and/or Golgi staining, instead of the typical punctuated pattern along the cell membrane. A pathway for directly targeting connexon hemichannels to cell-cell junctions involves the utilization of microtubules that tether to the cell membrane(Shaw, et al 2007, Lauf, et al 2002). Disruption of microtubules has been shown to reduce connexin-43 incorporation into gap junctions(George, et al 1999). Phthalates may alter the organization of microtubules(Nakagomi, et al 2001), suggesting that disruption of microtubular transport by DEHP can serve as one possible explanation of this effect. Additionally, modulation of gap junctional communication can also be attributed to changes in phosphorylation mediated by a number of kinases(Solan and Lampe 2005). For example, epsilon subtype of protein kinase C (PKC) has been shown to co-localize with connexin-43 at the cell membrane in cardiomyocytes, and this association has been linked to a decrease in gap junction communication(Doble, et al 2000). Furthermore, treatment with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), a PKC activator, has been shown to change the phosphorylation status of connexin-43 and lead to an accumulation of the protein in the Golgi(Cruciani and Mikalsen 2002a). Therefore, PKC-mediated phosphorylation of connexin-43 may not only affect channel gating, but also the assembly or degradation of gap junctions. Notably, PKC stimulation can lead to myocyte hypertrophy and other changes in cell phenotype(Vijayan, et al 2004, Dunnmon, et al 1990), therefore, additional experiments will be required to dissect the exact mechanism between DEHP and connexin-43.

The DEHP-induced alterations in the cell cytoskeleton might affect not only myocytes, but underlying fibroblasts as well. This phenomenon may be responsible for the unusual pattern of cell motion observed in DEHP-treated layers. We attributed the motion effect, at least in part, to a decreased amount of Triton-insoluble vimentin. Similar changes in vimentin have also been noted in DEHP-treated Sertoli cells(Kleymenova, et al 2005). Additional studies will be required to fully address the mechanism of this interesting phenomenon.

Despite all the limitations of an in vitro animal model, the presented findings raise serious concerns. The marked downregulation of electrical coupling in the presence of clinically-relevant concentrations of DEHP can cause notable impairment of cardiac function. Electrical abnormalities associated with heterogeneous and/or slow conduction are likely to lead to dangerous arrhythmias. Direct applicability of our findings to human patients remains to be established. It has to be noted, however, that premature newborns and patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass or placed on ECMO do receive large doses of DEHP (Table 1) and that alterations in connexin expression levels in these patients has been observed(Pavlovic, et al 2006). Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias arising from other factors are common in these high-risk patient groups and they may have obscured the uncoupling effects of DEHP on human myocardium in the past. Our findings call for more studies on this clinically relevant issue.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental online video 1. Confluent, spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes were treated with 0.1% DMSO for 72h in culture. The cells were loaded with 10μM Fluo-4AM, followed by optical mapping as detailed in Methods.

Supplemental online video 2. Confluent, spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes were treated with 50μg/ml DEHP in 0.1% DMSO for 72h in culture. The cells were loaded with 10μM Fluo-4AM, followed by optical mapping as detailed in Methods.

Supplemental online video 3. Confluent, spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes were treated with 50μg/ml DEHP for 72h in culture. The phase contrast movie shows the appearance of a “waterbed”-effect, suggestive of changes in the mechanical properties of the cell network. Phase contrast, field of view ~1.5mm across, 10X objective (to reduce the download time movies are shown in low resolution).

Supplemental online video 4. Confluent, spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes were treated with 50μg/ml DEHP for 5 days in culture. “Waterbed”-like myocyte motion became more pronounced as the duration of DEHP-treatment increased. Phase contrast, field of view ~1mm across, 16X objective (movies are shown in low resolution to reduce the download time).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ara Arutunyan, Felipe Aguel, and Joe Nielsen for helpful discussions and Dr. Paul Lampe for his advice on site-specific connexin antibodies. Financial support by the National Institutes of Health (HL076722 NS & HL087529 ZK) and Mid-Atlantic American Heart Association (0715335U NDG & 0665377U MWK) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anonymous . Center for Devices and Radiological Health. US Food and Drug Administration: Safety assessment of DEHP released from PVC medical devices; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson CE, Serlick ER, Preti G. Effects of di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate on the isolated perfused rat heart. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1978;44:155–169. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(78)90295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arutunyan A, Webster DR, Swift LM, Sarvazyan N. Localized injury in cardiomyocyte network: a new experimental model of ischemia-reperfusion arrhythmias. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1905–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arutunyan A, Swift LM, Sarvazyan N. Initiation and propagation of ectopic waves: insights from an in vitro model of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H741–749. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00096.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry YA, Labow RS, Keon WJ, Tocchi M. Atropine inhibition of the cardiodepressive effect of mono(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate on human myocardium. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1990;106:48–52. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(90)90104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry YA, Labow RS, Keon WJ, Tocchi M, Rock G. Perioperative exposure to plasticizers in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989;97:900–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry YA, Labow RS, Rock G, Keon WJ. Cardiotoxic effects of the plasticizer metabolite, mono (2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (MEHP), on human myocardium. Blood. 1988;72:1438–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman E, Laskey JW. Altered steroidogenesis in whole-ovary and adrenal culture in cycling rats. Reprod Toxicol. 1993;7:349–58. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(93)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya N, Dufour JM, Vo MN, Okita J, Okita R, Kim KH. Differential effects of phthalates on the testis and the liver. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:745–754. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.031583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, Dauca M, Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137:354–366. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.1.8536636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camelliti P, Green CR, Kohl P. Structural and functional coupling of cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. Adv Cardiol. 2006;42:132–49. doi: 10.1159/000092566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clusin WT. Calcium and cardiac arrhythmias: DADs, EADs, and alternans. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2003;40:337–75. doi: 10.1080/713609356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornu MC, Lhuguenot JC, Brady AM, Moore R, Elcombe CR. Identification of the proximate peroxisome proliferator(s) derived from di (2-ethylhexyl) adipate and species differences in response. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:2129–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90171-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruciani V, Mikalsen SO. Connexins, gap junctional intercellular communication and kinases. Biol Cell. 2002a;94:433–443. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(02)00014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruciani V, Mikalsen SO. Mechanisms involved in responses to the poroxisome proliferator WY-14,643 on gap junctional intercellular communication in V79 hamster fibroblasts. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2002b;182:66–75. doi: 10.1006/taap.2002.9431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doble BW, Ping P, Kardami E. The epsilon subtype of protein kinase C is required for cardiomyocyte connexin-43 phosphorylation. Circ Res. 2000;86:293–301. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunnmon PM, Iwaki K, Henderson SA, Sen A, Chien KR. Phorbol esters induce immediate-early genes and activate cardiac gene transcription in neonatal rat myocardial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1990;22:901–910. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(90)90121-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A, Fabiato F. Activation of skinned cardiac cells. Subcellular effects of cardioactive drugs. Eur J Cardiol. 1973;1:143–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration: Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Safety Assessment of Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) 2002. Released from PVC Medical Devices. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudesius G, Miragoli M, Thomas SP, Rohr S. Coupling of cardiac electrical activity over extended distances by fibroblasts of cardiac origin. Circ Res. 2003;93:421–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000089258.40661.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George CH, Kendall JM, Evans WH. Intracellular trafficking pathways in the assembly of connexins into gap junctions. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8678–8685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilde AJ, van der Lee KA, Willemsen PH, Chinetti G, van der Leij FR, van der Vusse GJ, Staels B, van Bilsen M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) alpha and PPARbeta/delta, but not PPARgamma, modulate the expression of genes involved in cardiac lipid metabolism. Circ Res. 2003;92:518–524. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000060700.55247.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez FJ. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha): role in hepatocarcinogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;193:71–79. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg JS, Kamendulis LM, Smith JH, Ackley DC, Pugh G, Jr, Lington AW, Klaunig JE. Effects of Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) on gap-junctional intercellular communication (GJIC), DNA synthesis, and peroxisomal beta oxidation (PBOX) in rat, mouse, and hamster liver. Toxicol Sci. 2000;56:73–85. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/56.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishide N, Miura M, Sakurai M, Takishima T. Initiation and development of calcium waves in rat myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H327–32. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.2.H327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamendulis LM, Isenberg JS, Smith JHGP, Jr, Lington AW, Klaunig JE. Comparative effects of phthalate monoesters on gap junctional intercellular communication and peroxisome proliferation in rodent and primate hepatocytes. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2002;65:569–88. doi: 10.1080/152873902317349736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang KS, Lee YS, Kim HS, Kim SH. DI-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-induced cell proliferation is involved in the inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication and blockage of apoptosis in mouse Sertoli cells. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2002;65:447–459. doi: 10.1080/15287390252808109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karle VA, Short BL, Martin GR, Bulas DI, Getson PR, Luban NL, O’Brien AM, Rubin RJ. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation exposes infants to the plasticizer, di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:696–703. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199704000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavlock R, Boekelheide K, Chapin R, Cunningham M, Faustman E, Foster P, Golub M, Henderson R, Hinberg I, Little R, Seed J, Shea K, Tabacova S, Tyl R, Williams P, Zacharewski T. NTP Center for the Evaluation of Risks to Human Reproduction: phthalates expert panel report on the reproductive and developmental toxicity of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate. Reprod Toxicol. 2002;16:529–653. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(02)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleymenova E, Swanson C, Boekelheide K, Gaido KW. Exposure in utero to di(n-butyl) phthalate alters the vimentin cytoskeleton of fetal rat Sertoli cells and disrupts Sertoli cell-gonocyte contact. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:482–490. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.037184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutovskikh VA, Mesnil M, Mazzoleni G, Yamasaki H. Inhibition of rat liver gap junction intercellular communication by tumor-promoting agents in vivo. Association with aberrant localization of connexin proteins. Lab Invest. 1995;72:571–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen ST, Nielsen GD. The adjuvant effect of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate is mediated through a PPARα-independent mechanism. Toxicology Letters. 2007;170:223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauf U, Giepmans BN, Lopez P, Braconnot S, Chen SC, Falk MM. Dynamic trafficking and delivery of connexons to the plasma membrane and accretion to gap junctions in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10446–10451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162055899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loff S, Kabs F, Witt K, Sartoris J, Mandl B, Niessen KH, Waag KL. Polyvinylchloride infusion lines expose infants to large amounts of toxic plasticizers. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1775–1781. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2000.19249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe I, Shindo T, Nagai R. Gene expression in fibroblasts and fibrosis: involvement in cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2002;91:1103–13. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000046452.67724.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsman DS, Cattley RC, Conway JG, Popp JA. Relationship of hepatic peroxisome proliferation and replicative DNA synthesis to the hepatocarcinogenicity of the peroxisome proliferators di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate and [4-chloro-6-(2,3-xylidino)-2-pyrimidinylthio]acetic acid (Wy-14,643) in rats. Cancer Res. 1988;48:6739–6744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee RH. The role of inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication in rodent liver tumor induction by phthalates: review of data on selected phthalates and the potential relevance to man. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2000;32:51–5. doi: 10.1006/rtph.2000.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagomi M, Suzuki E, Usumi K, Saitoh Y, Yoshimura S, Nagao T, Ono H. Effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals on the microtubule network in Chinese hamster V79 cells in culture and in Sertoli cells in rats. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen. 2001;21:453–462. doi: 10.1002/tcm.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks LG, Ostby JS, Lambright CR, Abbott BD, Klinefelter GR, Barlow NJEGL., Jr The plasticizer diethylhexyl phthalate induces malformations by decreasing fetal testosterone synthesis during sexual differentiation in the male rat. Toxicol Sci. 2000;58:339–49. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/58.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovic M, Schaller A, Ammann RA, Sanz J, Pfammatter JP, Carrel T, Berdat P, Gallati S. Reduced atrial connexin43 expression after pediatric heart surgery. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peraza MA, Burdick AD, Marin HE, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. The toxicology of ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) Toxicol Sci. 2006;90:269–295. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM, Taubeneck MW, Keen CL, Gonzalez FJ. Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate induces a functional zinc deficiency during pregnancy and teratogenesis that is independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha. Teratology. 1997;56:311–316. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199711)56:5<311::AID-TERA4>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh G, Jr, Isenberg JS, Kamendulis LM, Ackley DC, Clare LJ, Brown R, Lington AW, Smith JH, Klaunig JE. Effects of di-isononyl phthalate, di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate, and clofibrate in cynomolgus monkeys. Toxicol Sci. 2000;56:181–188. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/56.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumir A, Arutunyan A, Krinsky V, Sarvazyan N. Genesis of ectopic waves: role of coupling, automaticity, and heterogeneity. Biophys J. 2005;89:2332–49. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.061820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rais-Bahrami K, Nunez S, Revenis ME, Luban NL, Short BL. Follow-up study of adolescents exposed to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) as neonates on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1339–1340. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock G, Labow RS, Franklin C, Burnett R, Tocchi M. Hypotension and cardiac arrest in rats after infusion of mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP), a contaminant of stored blood. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1218–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198705073161915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin RJ, Jaeger RJ. Some Pharmacologic and Toxicologic Effects of Di-2-Ethylhexyl Phthalate (DEHP) and Other Plasticizers. Environ Health Perspect. 1973;3:53–59. doi: 10.1289/ehp.730353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JY, Whang J, Park H, Im JY, Kim J, Ahn MY, Lee J, Kim HS, Lee BM, Yoo SD, Kwack SJ, Oh JH, Park KL, Han SY, Kim SH. Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate induces apoptosis through peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor-gamma and ERK 1/2 activation in testis of Sprague-Dawley rats. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2007;70:1296–1303. doi: 10.1080/15287390701432160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe RM. Hormones and testis development and the possible adverse effects of environmental chemicals. Toxicol Lett. 2001;120:221–32. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(01)00298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RM, Fay AJ, Puthenveedu MA, von Zastrow M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Microtubule plus-end-tracking proteins target gap junctions directly from the cell interior to adherens junctions. Cell. 2007;128:547–560. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani H. Determination of phthalic acid, mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in human plasma and in blood products. J Chromatogr. 1985;337:279–290. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(85)80041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shneider B, Schena J, Truog R, Jacobson M, Kevy S. Exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate in infants receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1563. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906083202323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoberg P, Bondesson U, Sedin G, Gustafsson J. Dispositions of di- and mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in newborn infants subjected to exchange transfusions. Eur J Clin Invest. 1985;15:430–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1985.tb00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solan JL, Lampe PD. Connexin phosphorylation as a regulatory event linked to gap junction channel assembly. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1711:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosinsky GE, Solan JL, Gaietta GM, Ngan L, Lee GJ, Mackey MR, Lampe PD. The C-terminus of connexin43 adopts different conformations in the Golgi and gap junction as detected with structure-specific antibodies. Biochem J. 2007;408:375–385. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SA, Schuessler RB, Berul CI, Beardslee MA, Beyer EC, Mendelsohn ME, Saffitz JE. Disparate Effects of Deficient Expression of Connexin43 on Atrial and Ventricular Conduction: Evidence for Chamber-Specific Molecular Determinants of Conduction. Circulation. 1998;97:686–691. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.7.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan K, Szotek EL, Martin JL, Samarel AM. Protein kinase C-alpha-induced hypertrophy of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2777–89. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00171.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Stamenovic D. Mechanics of vimentin intermediate filaments. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2002;23:535–540. doi: 10.1023/a:1023470709071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Kakinuma Y, Ando M, Katare RG, Yamasaki F, Sugiura T, Sato T. Acetylcholine inhibits the hypoxia-induced reduction of connexin43 protein in rat cardiomyocytes. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;101:214–222. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0051023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental online video 1. Confluent, spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes were treated with 0.1% DMSO for 72h in culture. The cells were loaded with 10μM Fluo-4AM, followed by optical mapping as detailed in Methods.

Supplemental online video 2. Confluent, spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes were treated with 50μg/ml DEHP in 0.1% DMSO for 72h in culture. The cells were loaded with 10μM Fluo-4AM, followed by optical mapping as detailed in Methods.

Supplemental online video 3. Confluent, spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes were treated with 50μg/ml DEHP for 72h in culture. The phase contrast movie shows the appearance of a “waterbed”-effect, suggestive of changes in the mechanical properties of the cell network. Phase contrast, field of view ~1.5mm across, 10X objective (to reduce the download time movies are shown in low resolution).

Supplemental online video 4. Confluent, spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes were treated with 50μg/ml DEHP for 5 days in culture. “Waterbed”-like myocyte motion became more pronounced as the duration of DEHP-treatment increased. Phase contrast, field of view ~1mm across, 16X objective (movies are shown in low resolution to reduce the download time).